Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Burkholderia pseudomallei complex and B. cepacia complex are two evolutionary distinct clades of pathogens causing human disease. Most vaccine efforts have focused on the former group largely due to their biothreat status and global disease burden. It has been proposed that a vaccine could be developed that simultaneously protects against both groups of Burkholderia by specifically targeting conserved antigens. Only a few studies have set out to identify which antigens may be optimal targets for such a vaccine. We have previously assessed the ability of three highly conserved B. pseudomallei antigens, OmpA1, OmpA2, and Pal coupled to gold nanoparticles (nanovaccines), to protect mice against a homotypic B. pseudomallei challenge. Here, we have expanded our study by demonstrating that antibodies to each of these proteins show varying levels of reactivity to homologs in B. cepacia complex, with OmpA2 antibodies exhibiting the highest cross-reactivity. Remarkably, some immunized mice with our nanovaccines, particularly those that received OmpA2, produce antibodies that bind Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which harbor distantly related homologous proteins. T cells elicited to Pal and OmpA2 responded to stimulation with B. cepacia complex-derived proteins. Our study supports incorporation of these antigens, particularly OmpA2, for the development of a pan-Burkholderia vaccine.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In silico methodology

2.2. Bacterial strains and growth conditions

2.3. Cloning and Recombinant Protein Expression

2.4. Recombinant Protein Purification

2.5. Gold Nanoparticle Vaccine Synthesis

2.6. Mouse Immunizations and Tissue Collection

2.7. Serum Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISAs)

2.8. Antigen Recall of Splenocytes

3. Results

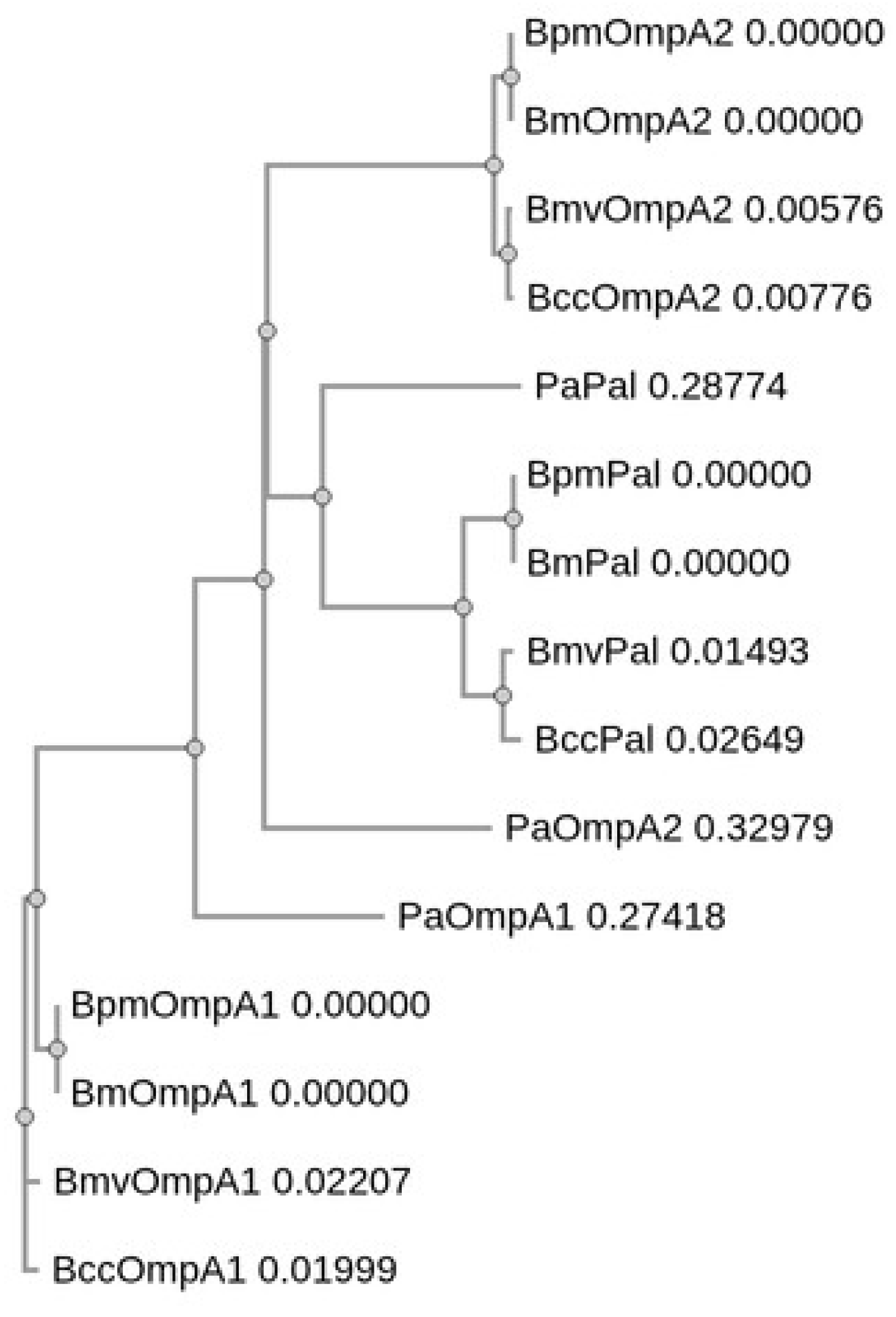

3.1. Identification and Sequence Analysis of OmpA C-like Homologs in Bm, Bmv, Bcc, and Pa

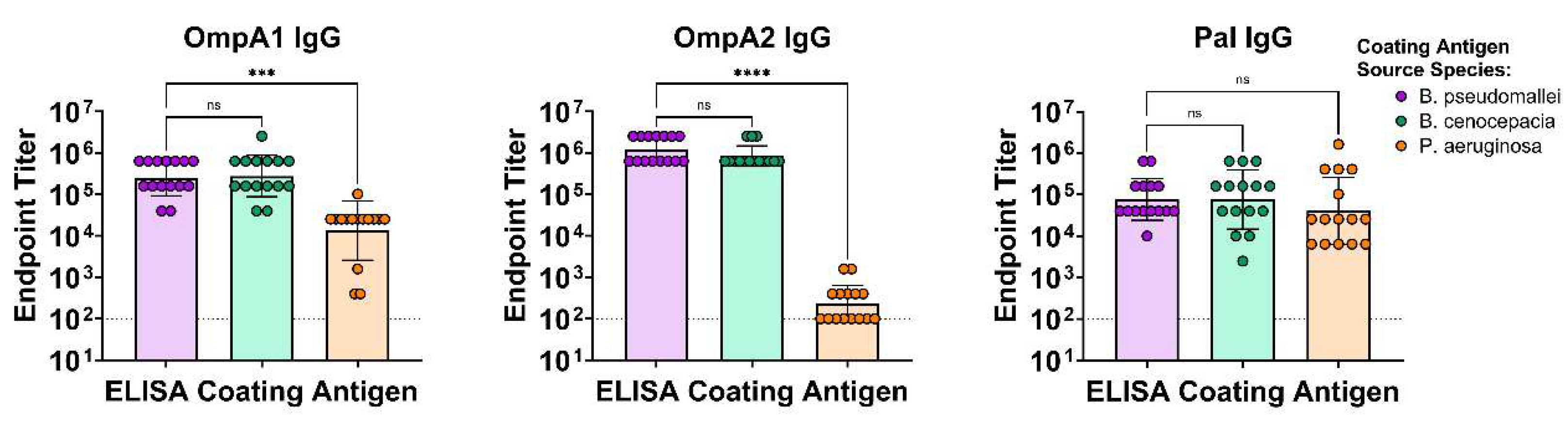

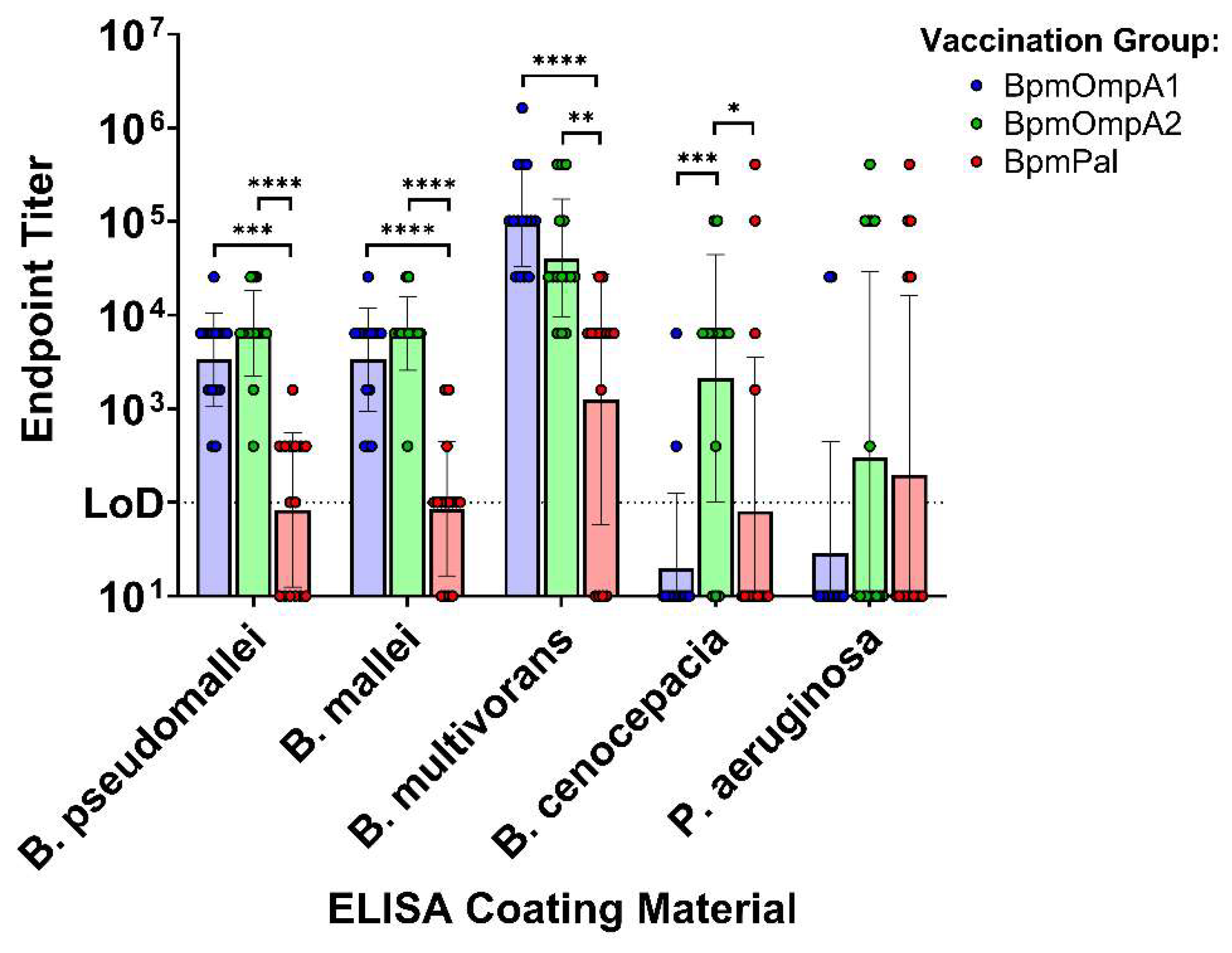

3.2. Antibodies Elicited to the Bpm Homologs Exhibit Varying Levels of Cross-Reactivity to Bcc and Pa

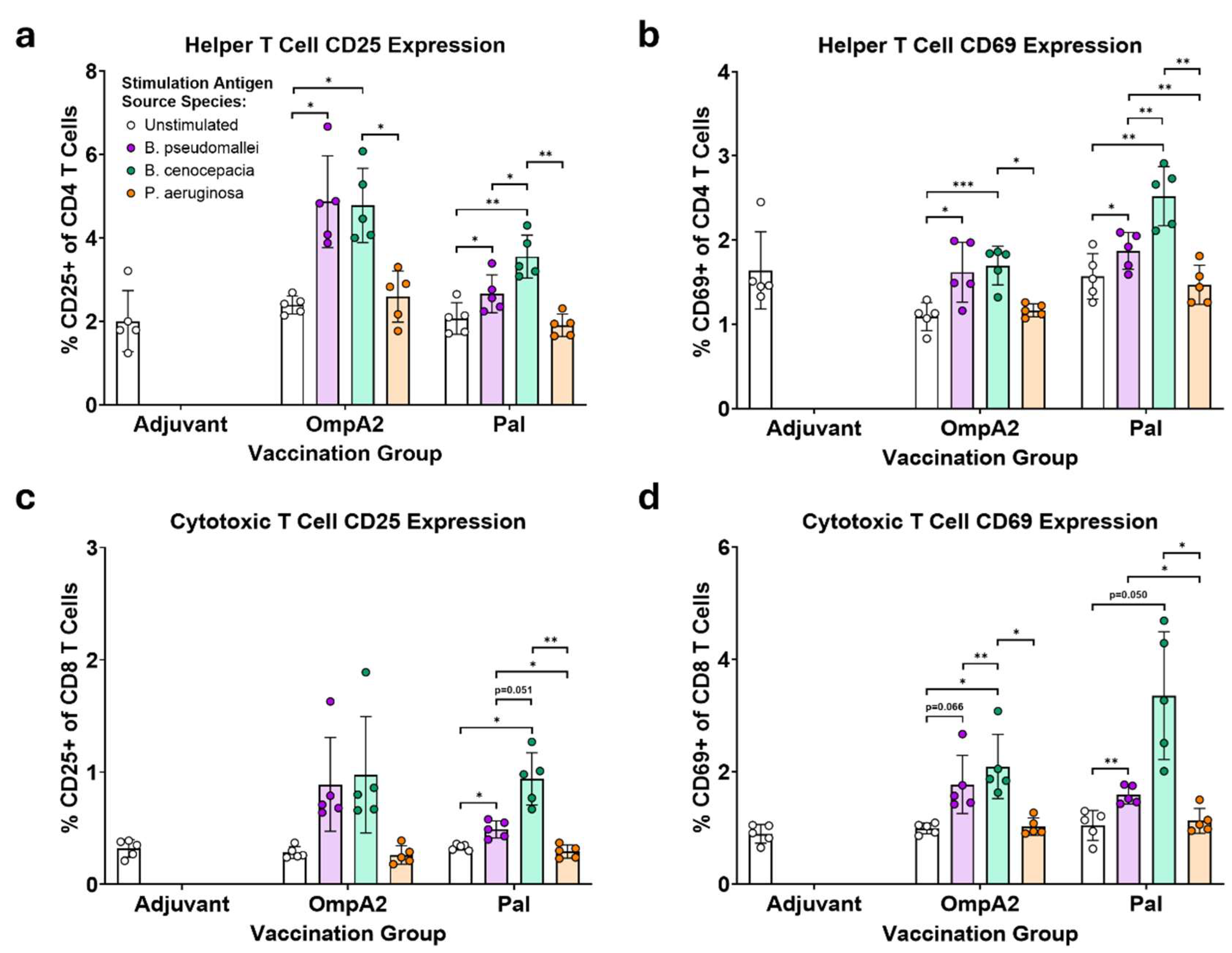

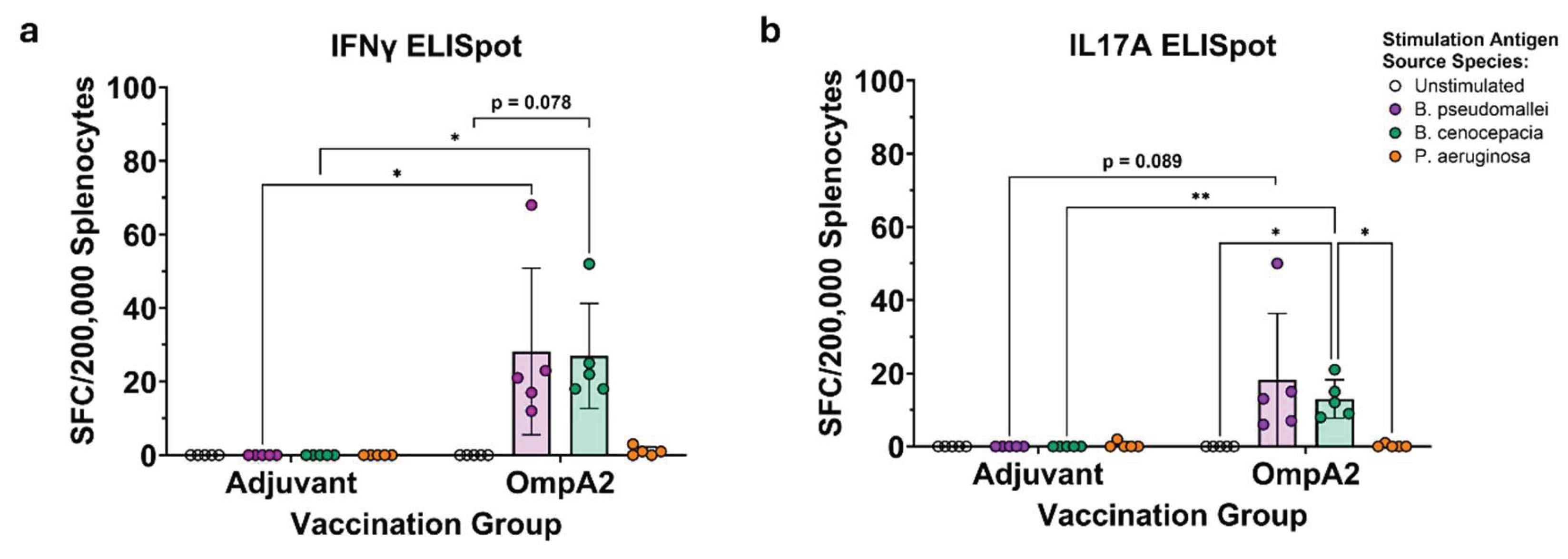

3.3. BpmOmpA2- and BpmPal-specific T Cells Cross-React to Their Direct Bcc Homologs

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Bm | Burkholderia mallei |

| Bpm | Burkholderia pseudomallei |

| Bmv | Burkholderia multivorans |

| Bcc | Burkholderia cenocepacia |

| Pa | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| BLASTp | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (proteins) |

| BLOSUM | Blocks Substitution Matrix |

| LB | Luria-Bertani |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PES | Polyethersulfone |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| PBS | Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| AuNP | Gold Nanoparticle |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic Acid Assay |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| cRPMI | Complete Roswell Park Memorial Institute Media |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| TMB | 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine |

| OD | Optical Density |

| ELISpot | Enzyme-Linked Immunospot |

| FACS | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting |

| SFC | Spot-Forming Cell |

| mAb | Monoclonal Antibody |

References

- Estrada-De Los Santos, P.; Bustillos-Cristales, R.; Caballero-Mellado, J. Burkholderia, a Genus Rich in Plant-Associated Nitrogen Fixers with Wide Environmental and Geographic Distribution. Appl Environ Microbiol 2001, 67, 2790–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberl, L.; Vandamme, P. Members of the Genus Burkholderia: Good and Bad Guys. F1000Res 2016, 5, F1000 Faculty Rev–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morya, R.; Salvachúa, D.; Thakur, I.S. Burkholderia: An Untapped but Promising Bacterial Genus for the Conversion of Aromatic Compounds. Trends Biotechnol 2020, 38, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiersinga, W.J.; Virk, H.S.; Torres, A.G.; Currie, B.J.; Peacock, S.J.; Dance, D.A.B.; Limmathurotsakul, D. Melioidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meumann, E.M.; Limmathurotsakul, D.; Dunachie, S.J.; Wiersinga, W.J.; Currie, B.J. Burkholderia Pseudomallei and Melioidosis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2024, 22, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limmathurotsakul, D.; Golding, N.; Dance, D.A.; Messina, J.P.; Pigott, D.M.; Moyes, C.L.; Rolim, D.B.; Bertherat, E.; Day, N.P.; Peacock, S.J.; et al. Predicted Global Distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burden of Melioidosis. Nat Microbiol 2016, 1, 15008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zandt, K.E.; Greer, M.T.; Gelhaus, H.C. Glanders: An Overview of Infection in Humans. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, B.J. Melioidosis: Evolving Concepts in Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015, 36, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, B.J.; Mayo, M.; Ward, L.M.; Kaestli, M.; Meumann, E.M.; Webb, J.R.; Woerle, C.; Baird, R.W.; Price, R.N.; Marshall, C.S.; et al. The Darwin Prospective Melioidosis Study: A 30-Year Prospective, Observational Investigation. Lancet Infect Dis 2021, 21, 1737–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, A.J.; Inglis, T.J.J. The Role of Climate in the Epidemiology of Melioidosis. Curr Trop Med Rep 2017, 4, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.Y.A.; Fisher, D. Earth, Wind, Rain, and Melioidosis. Lancet Planet Health 2018, 2, e329–e330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HAN Archive - 00470 | Health Alert Network (HAN). Available online: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/han/2022/han00470.html (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Brennan, S.; Thompson, J.M.; Gulvik, C.A.; Paisie, T.K.; Elrod, M.G.; Gee, J.E.; Schrodt, C.A.; DeBord, K.M.; Richardson, B.T.; Drenzek, C.; et al. Related Melioidosis Cases with Unknown Exposure Source, Georgia, USA, 1983–2024. Emerg Infect Dis 2025, 31, 1802–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassiep, I.; Grey, V.; Thean, L.J.; Farquhar, D.; Clark, J.E.; Ariotti, L.; Graham, R.; Jennison, A.V.; Bergh, H.; Anuradha, S.; et al. Expanding the Geographic Boundaries of Melioidosis in Queensland, Australia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2023, 108, 1215–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, M.; Kozak, M.; Balola, A.; Sá-Correia, I. Burkholderia cepacia Complex Bacteria: A Feared Contamination Risk in Water-Based Pharmaceutical Products. Clin Microbiol Rev 2020, 33, 10.1128/cmr.00139-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velez, L.S.; Aburjaile, F.F.; Farias, A.R.G.; Baia, A.D.B.; Oliveira, W.J.; Silva, A.M.F.; Benko-Iseppon, A.M.; Azevedo, V.; Brenig, B.; Ham, J.H.; et al. Burkholderia Semiarida Sp. Nov. and Burkholderia Sola Sp. Nov., Two Novel B. cepacia Complex Species Causing Onion Sour Skin. Syst Appl Microbiol 2023, 46, 126415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torbeck, L.; Raccasi, D.; Guilfoyle, D.E.; Friedman, R.L.; Hussong, D. Burkholderia cepacia: This Decision Is Overdue. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol 2011, 65, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häfliger, E.; Atkinson, A.; Marschall, J. Systematic Review of Healthcare-Associated Burkholderia cepacia Complex Outbreaks: Presentation, Causes and Outbreak Control. Infect Prev Pract 2020, 2, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC About Burkholderia cepacia Complex. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/b-cepacia/about/index.html (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Scoffone, V.C.; Chiarelli, L.R.; Trespidi, G.; Mentasti, M.; Riccardi, G.; Buroni, S. Burkholderia cenocepacia Infections in Cystic Fibrosis Patients: Drug Resistance and Therapeutic Approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlosnik, J.E.A.; Henry, D.A.; Hird, T.J.; Hickman, R.; Campbell, M.; Cabrera, A.; Laino Chiavegatti, G.; Chilvers, M.A.; Sadarangani, M. Epidemiology of Burkholderia Infections in People with Cystic Fibrosis in Canada between 2000 and 2017. Annals ATS 2020, 17, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badten, A.J.; Torres, A.G. Burkholderia pseudomallei Complex Subunit and Glycoconjugate Vaccines and Their Potential to Elicit Cross-Protection to Burkholderia cepacia Complex. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Select Agents and Toxins List | Federal Select Agent Program. Available online: https://www.selectagents.gov/sat/list.htm (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Sengyee, S.; Weiby, S.B.; Rok, I.T.; Burtnick, M.N.; Brett, P.J. Melioidosis Vaccines: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Front Immunol 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertot, G.M.; Restelli, M.A.; Galanternik, L.; Aranibar Urey, R.C.; Valvano, M.A.; Grinstein, S. Nasal Immunization with Burkholderia multivorans Outer Membrane Proteins and the Mucosal Adjuvant Adamantylamide Dipeptide Confers Efficient Protection against Experimental Lung Infections with B. multivorans and B. cenocepacia. Infect Immun 2007, 75, 2740–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makidon, P.E.; Knowlton, J.; Groom, J.V.; Blanco, L.P.; LiPuma, J.J.; Bielinska, A.U.; Baker, J.R. Induction of Immune Response to the 17 kDa OmpA Burkholderia cenocepacia Polypeptide and Protection against Pulmonary Infection in Mice after Nasal Vaccination with an Omp Nanoemulsion-Based Vaccine. Med Microbiol Immunol 2010, 199, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, S.; Healy, M.E.; Collins, C.; Carberry, S.; O’Shaughnessy, L.; Dennehy, R.; Adams, Á.; Kennelly, H.; Corbett, J.M.; Carty, F.; et al. Linocin and OmpW Are Involved in Attachment of the Cystic Fibrosis-Associated Pathogen Burkholderia cepacia Complex to Lung Epithelial Cells and Protect Mice against Infection. Infect Immun 2016, 84, 1424–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawad, W.E.; Nagy, Y.I.; Samir, T.M.; Mansour, A.M.I.; Helmy, O.M. Cyclic Di AMP Phosphodiesterase Nanovaccine Elicits Protective Immunity against Burkholderia cenocepacia Infection in Mice. npj Vaccines 2025, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradenas, G.A.; Myers, J.N.; Torres, A.G. Characterization of the Burkholderia cenocepacia tonB Mutant as a Potential Live Attenuated Vaccine. Vaccines (Basel) 2017, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rongkard, P.; Kronsteiner, B.; Hantrakun, V.; Jenjaroen, K.; Sumonwiriya, M.; Chaichana, P.; Chumseng, S.; Chantratita, N.; Wuthiekanun, V.; Fletcher, H.A.; et al. Human Immune Responses to Melioidosis and Cross-Reactivity to Low-Virulence Burkholderia Species, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis 2020, 26, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, D.; Sanchez-Villamil, J.I.; Stevenson, H.L.; Torres, A.G. Multicomponent Gold-Linked Glycoconjugate Vaccine Elicits Antigen-Specific Humoral and Mixed TH1-TH17 Immunity, Correlated with Increased Protection against Burkholderia pseudomallei. mBio 12, e01227-21. [CrossRef]

- Burtnick, M.N.; Dance, D.A.B.; Vongsouvath, M.; Newton, P.N.; Dittrich, S.; Sendouangphachanh, A.; Woods, K.; Davong, V.; Kenna, D.T.D.; Saiprom, N.; et al. Identification of Burkholderia cepacia Strains That Express a Burkholderia pseudomallei-like Capsular Polysaccharide. Microbiol Spectr 12, e03321-23. [CrossRef]

- Seixas, A.M.M.; Gomes, S.C.; Silva, C.; Moreira, L.M.; Leitão, J.H.; Sousa, S.A. A Polyclonal Antibody against a Burkholderia cenocepacia OmpA-like Protein Strongly Impairs Pseudomonas aeruginosa and B. multivorans Virulence. Vaccines 2024, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badten, A.J.; Oaxaca-Torres, S.; Basu, R.S.; Gagnon, M.G.; Torres, A.G. Evaluation of Highly Conserved Burkholderia pseudomallei Outer Membrane Proteins as Protective Antigens against Respiratory Melioidosis. npj Vaccines 2025, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musson, J.A.; Reynolds, C.J.; Rinchai, D.; Nithichanon, A.; Khaenam, P.; Favry, E.; Spink, N.; Chu, K.K.; De Soyza, A.; Bancroft, G.J.; et al. CD4+ T Cell Epitopes of FliC Conserved between Strains of Burkholderia - Implications for Vaccines against Melioidosis and Cepacia Complex in Cystic Fibrosis. J Immunol 2014, 193, 6041–6049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacy, D.E.; Smith, A.W.; Stableforth, D.E.; Smith, G.; Weller, P.H.; Brown, M.R.W. Serum IgG Response to Burkholderia cepacia Outer Membrane Antigens in Cystic Fibrosis: Assessment of Cross-Reactivity with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 1995, 10, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu-Borrás, M.; Dublin, S.R.; Kang, J.; Monroe, H.L.; Sen-Kilic, E.; Miller, S.J.; Witt, W.T.; Chapman, J.A.; Pyles, G.M.; Nallar, S.C.; et al. Novel Broadly Reactive Monoclonal Antibody Protects against Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection. Infect Immun 2024, 93, e00330-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, Y.; Mohamed, R.; Nathan, S. Immunogenic Burkholderia pseudomallei Outer Membrane Proteins as Potential Candidate Vaccine Targets. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, O.L.; Gourlay, L.J.; Scott, A.E.; Lassaux, P.; Conejero, L.; Perletti, L.; Hemsley, C.; Prior, J.; Bancroft, G.; Bolognesi, M.; et al. Immunisation with Proteins Expressed during Chronic Murine Melioidosis Provides Enhanced Protection against Disease. Vaccine 2016, 34, 1665–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyke, J.S.; Huertas-Diaz, Maria Cristina; Michel, Frank; Holladay, Nathan E.; Hogan, Robert J.; He, Biao; Lafontaine, E.R. The Peptidoglycan-Associated Lipoprotein Pal Contributes to the Virulence of Burkholderia mallei and Provides Protection against Lethal Aerosol Challenge. Virulence 2020, 11, 1024–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J Mol Biol 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and Applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Lee, J.; Eusebi, A.; Niewielska, A.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Lopez, R.; Butcher, S. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher Sequence Analysis Tools Framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, W521–W525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.A.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2—a Multiple Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Propst, K.L.; Mima, T.; Choi, K.-H.; Dow, S.W.; Schweizer, H.P. A Burkholderia pseudomallei ΔpurM Mutant Is Avirulent in Immunocompetent and Immunodeficient Animals: Candidate Strain for Exclusion from Select-Agent Lists. Infect Immun 2010, 78, 3136–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatcher, C.L.; Mott, T.M.; Muruato, L.A.; Sbrana, E.; Torres, A.G. Burkholderia mallei CLH001 Attenuated Vaccine Strain Is Immunogenic and Protects against Acute Respiratory Glanders. Infect Immun 2016, 84, 2345–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Confer, A.W.; Ayalew, S. The OmpA Family of Proteins: Roles in Bacterial Pathogenesis and Immunity. Vet Microbiol 2013, 163, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, L.V.; Snyder, J.; Schmidt, R.; Milillo, J.; Grimaldi, K.; Kalmeta, B.; Khan, M.N.; Sharma, S.; Wright, L.K.; Pichichero, M.E. Dual Orientation of the Outer Membrane Lipoprotein P6 of Nontypeable Haemophilus Influenzae. J Bacteriol 2013, 195, 3252–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourlay, L.J.; Peri, C.; Ferrer-Navarro, M.; Conchillo-Solé, O.; Gori, A.; Rinchai, D.; Thomas, R.J.; Champion, O.L.; Michell, S.L.; Kewcharoenwong, C.; et al. Exploiting the Burkholderia pseudomallei Acute Phase Antigen BPSL2765 for Structure-Based Epitope Discovery/Design in Structural Vaccinology. Chem Biol 2013, 20, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, L.V.; Shaw, J.; MacPherson, V.; Barnard, D.; Bettinger, J.; D’Arcy, B.; Surendran, N.; Hellman, J.; Pichichero, M.E. Dual Orientation of the Outer Membrane Lipoprotein Pal in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 2015, 161, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Gu, J.; Zou, J.; Lei, L.; Jing, H.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, H.; Zou, Q.; Lv, F.; Zhang, J. PA0833 Is an OmpA C-Like Protein That Confers Protection Against Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection. Front Microbiol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Chen, Z.; Gao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wan, J.; Wei, Y.; Zeng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Structural and Biological Insights into Outer Membrane Protein Lipotoxin F of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Implications for Vaccine Application. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 253, 127634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, J.; Webby, M.N. The Tol Pal System Integrates Maintenance of the Three Layered Cell Envelope. npj Antimicrob Resist 2024, 2, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.M.; Bernstein, H.D. Surface Exposed Lipoproteins: An Emerging Secretion Phenomenon in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Trends Microbiol 2016, 24, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, S.A.; Seixas, A.M.M.; Mandal, M.; Rodríguez-Ortega, M.J.; Leitão, J.H. Characterization of the Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315 Surface-Exposed Immunoproteome. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, G.B.; Bateman, T.J.; Moraes, T.F. The Surface Lipoproteins of Gram-Negative Bacteria: Protectors and Foragers in Harsh Environments. J Biol Chem 2020, 296, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, A.E.; Judy, B.M.; Qazi, O.; Blumentritt, C.A.; Brown, K.A.; Shaw, A.M.; Torres, A.G.; Titball, R.W. A Gold Nanoparticle-Linked Glycoconjugate Vaccine against Burkholderia mallei. Nanomed: Nanotechnol Biol Med 2015, 11, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, H.; Zou, Q.; Gu, J. Vaccination with a Recombinant OprL Fragment Induces a Th17 Response and Confers Serotype-Independent Protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection in Mice. Clin Immunol 2017, 183, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Chen, Y. Recombinant PAL/PilE/FlaA DNA Vaccine Provides Protective Immunity against Legionella pneumophila in BALB/c Mice. BMC Biotechnol 2020, 20, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, V.; Tiwari, M.; Tiwari, V. Investigation of Peptidoglycan-Associated Lipoprotein of Acinetobacter baumannii and Its Interaction with Fibronectin To Find Its Therapeutic Potential. Infect Immun 91, e00023-23. [CrossRef]

- Seixas, A.M.M.; Sousa, S.A.; Feliciano, J.R.; Gomes, S.C.; Ferreira, M.R.; Moreira, L.M.; Leitão, J.H. A Polyclonal Antibody Raised against the Burkholderia cenocepacia OmpA-like Protein BCAL2645 Impairs the Bacterium Adhesion and Invasion of Human Epithelial Cells in vitro. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Species Summary | Microbiome Atlas. Available online: https://www.microbiomeatlas.org/species_summary.php (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Park, J.S.; Lee, W.C.; Yeo, K.J.; Ryu, K.-S.; Kumarasiri, M.; Hesek, D.; Lee, M.; Mobashery, S.; Song, J.H.; Kim, S.I.; et al. Mechanism of Anchoring of OmpA Protein to the Cell Wall Peptidoglycan of the Gram-Negative Bacterial Outer Membrane. FASEB J 2012, 26, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Hsu, R.; Rafizadeh, D.L.; Wang, L.; Bowlus, C.L.; Kumar, N.; Mishra, J.; Timilsina, S.; Ridgway, W.M.; Gershwin, M.E.; et al. The Gut Ecosystem and Immune Tolerance. J Autoimmun 2023, 141, 103114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfanimanesh, S.; Emaneini, M.; Modaresi, M.R.; Feizabadi, M.M.; Halimi, S.; Beigverdi, R.; Nikbin, V.S.; Jabalameli, F. Distribution and Characteristics of Bacteria Isolated from Cystic Fibrosis Patients with Pulmonary Exacerbation. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2022, 2022, 5831139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinola, S.M.; Griffiths, G.E.; Bogdan, J.; Menegus, M.A. Characterization of an 18,000-Molecular-Weight Outer Membrane Protein of Haemophilus ducreyi That Contains a Conserved Surface-Exposed Epitope. Infect Immun 1992, 60, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgner, P.L.; Kayala, M.A.; Vigil, A.; Burk, C.; Nakajima-Sasaki, R.; Pablo, J.; Molina, D.M.; Hirst, S.; Chew, J.S.W.; Wang, D.; et al. A Burkholderia pseudomallei Protein Microarray Reveals Serodiagnostic and Cross-Reactive Antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106, 13499–13504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.R.; Lertmemongkolchai, G.; Tan, G.; Felgner, P.L.; Titball, R. A Genetic Programming Approach for Burkholderia pseudomallei Diagnostic Pattern Discovery. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2256–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Chin, C.-Y.; Mohamed, R.; Puthucheary, S.D.; Nathan, S. Multiple-Antigen ELISA for Melioidosis - a Novel Approach to the Improved Serodiagnosis of Melioidosis. BMC Infect Dis 2013, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, C.; Dunachie, S.J.; Müller, E.; Kohler, A.; Jenjaroen, K.; Teparrukkul, P.; Baier, V.; Ehricht, R.; Steinmetz, I. Rapid and Sensitive Multiplex Detection of Burkholderia pseudomallei-Specific Antibodies in Melioidosis Patients Based on a Protein Microarray Approach. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016, 10, e0004847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, G.E.; Stanjek, T.F.P.; Albrecht, D.; Lipp, M.; Dunachie, S.J.; Föderl-Höbenreich, E.; Riedel, K.; Kohler, A.; Steinmetz, I.; Kohler, C. Deciphering the Human Antibody Response against Burkholderia pseudomallei during Melioidosis Using a Comprehensive Immunoproteome Approach. Front Immunol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Settles, E.W.; Sonderegger, D.; Shannon, A.B.; Celona, K.R.; Lederer, R.; Yi, J.; Seavey, C.; Headley, K.; Mbegbu, M.; Harvey, M.; et al. Development and Evaluation of a Multiplex Serodiagnostic Bead Assay (BurkPx) for Accurate Melioidosis Diagnosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2023, 17, e0011072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, J.J.; Vigil, A.; DeShazer, D.; Waag, D.M.; Felgner, P.; Goldberg, J.B. Distinct Human Antibody Response to the Biological Warfare Agent Burkholderia mallei. Virulence 2012, 3, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G.E.; Berner, A.; Lipp, M.; Kohler, C.; Assig, K.; Lichtenegger, S.; Saqib, M. Protein Microarray-Guided Development of a Highly Sensitive and Specific Dipstick Assay for Glanders Serodiagnostics. Clin Microbiol 2023, 61, e01234-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, Y.; Iinuma, Y.; Okagawa, T.; Shimbo, R.; Enkhtuul, B.; Kjurtsbaatar, O.; Kinoshita, Y.; Niwa, H.; Aoshima, K.; Kobayashi, A.; et al. Comparison of Immunogenicity of 17 Burkholderia mallei Antigens and Whole Cell Lysate Using Indirect ELISA. J Vet Med Sci 2025, 87, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, C.; Gori, A.; Gagni, P.; Sola, L.; Girelli, D.; Sottotetti, S.; Cariani, L.; Chiari, M.; Cretich, M.; Colombo, G. Evolving Serodiagnostics by Rationally Designed Peptide Arrays: The Burkholderia Paradigm in Cystic Fibrosis. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 32873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenjaroen, K.; Chumseng, S.; Sumonwiriya, M.; Ariyaprasert, P.; Chantratita, N.; Sunyakumthorn, P.; Hongsuwan, M.; Wuthiekanun, V.; Fletcher, H.A.; Teparrukkul, P.; et al. T-Cell Responses Are Associated with Survival in Acute Melioidosis Patients. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0004152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, J.S.; Wang, Y. Protective Role of Th17 Cells in Pulmonary Infection. Vaccine 2016, 34, 1504–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsström, B.; Bisławska Axnäs, B.; Rockberg, J.; Danielsson, H.; Bohlin, A.; Uhlen, M. Dissecting Antibodies with Regards to Linear and Conformational Epitopes. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0121673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Bpm

Locus Tag* |

Bm

Sequence Identity (%) |

Bmv

Sequence Identity (%) |

Bcc

Sequence Identity (%) |

Pa Sequence Coverage (%) |

Pa

Sequence Identity (%) |

| BPSL0999 | 100 | 93.87 | 93.49 | 60 | 53.08 |

| BPSL2522 | 100 | 91.52 | 90.58 | 52 | 39.32 |

| BPSL2765 | 100 | 86.47 | 84.12 | 87 | 46.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).