Submitted:

01 January 2025

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Protein Retrieval and Preliminary Characterization

2.2. Protein Conservation in Other Mycobacterium Species

2.3. Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte Epitope Prediction

2.4. Helper T Lymphocyte Epitope Prediction

2.5. Linear B-Lymphocyte Epitopes Prediction

2.6. Antibody Class Prediction

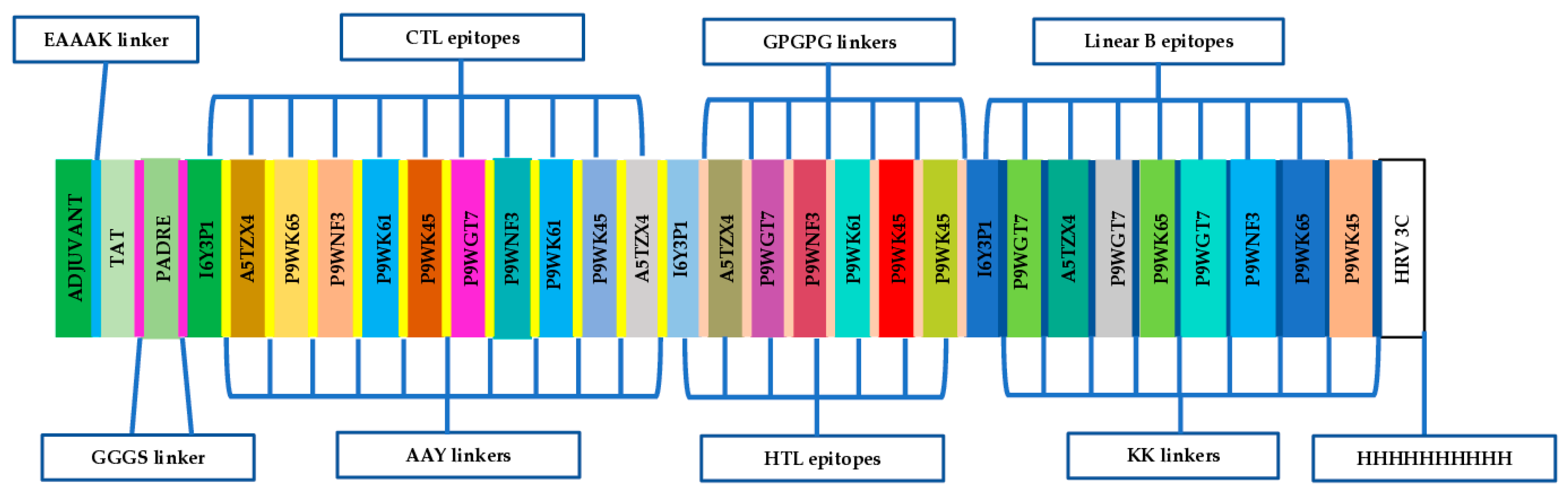

2.7. Design of the Chimeric Multi-Epitope Vaccine Candidate

2.8. Physicochemical Properties and Solubility Analysis

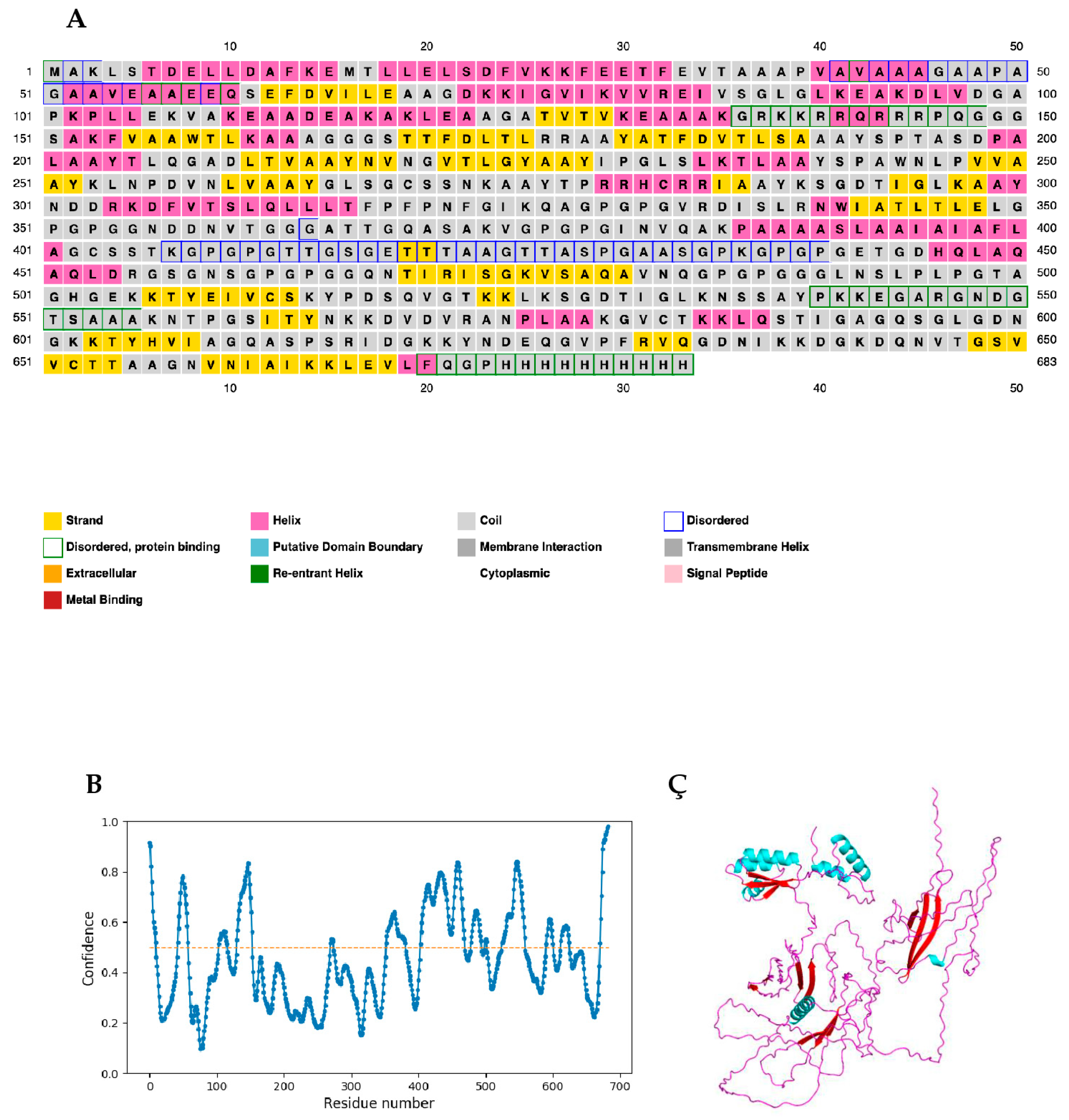

2.9. Secondary Structure and Intrinsic Disorder Prediction

2.10. Antigenicity, Allergenicity, and Toxigenicity Prediction

2.11. IFN-γ-Inducing Epitope Prediction

2.12. Prediction of Epitopes for Mouse MHC II Alleles

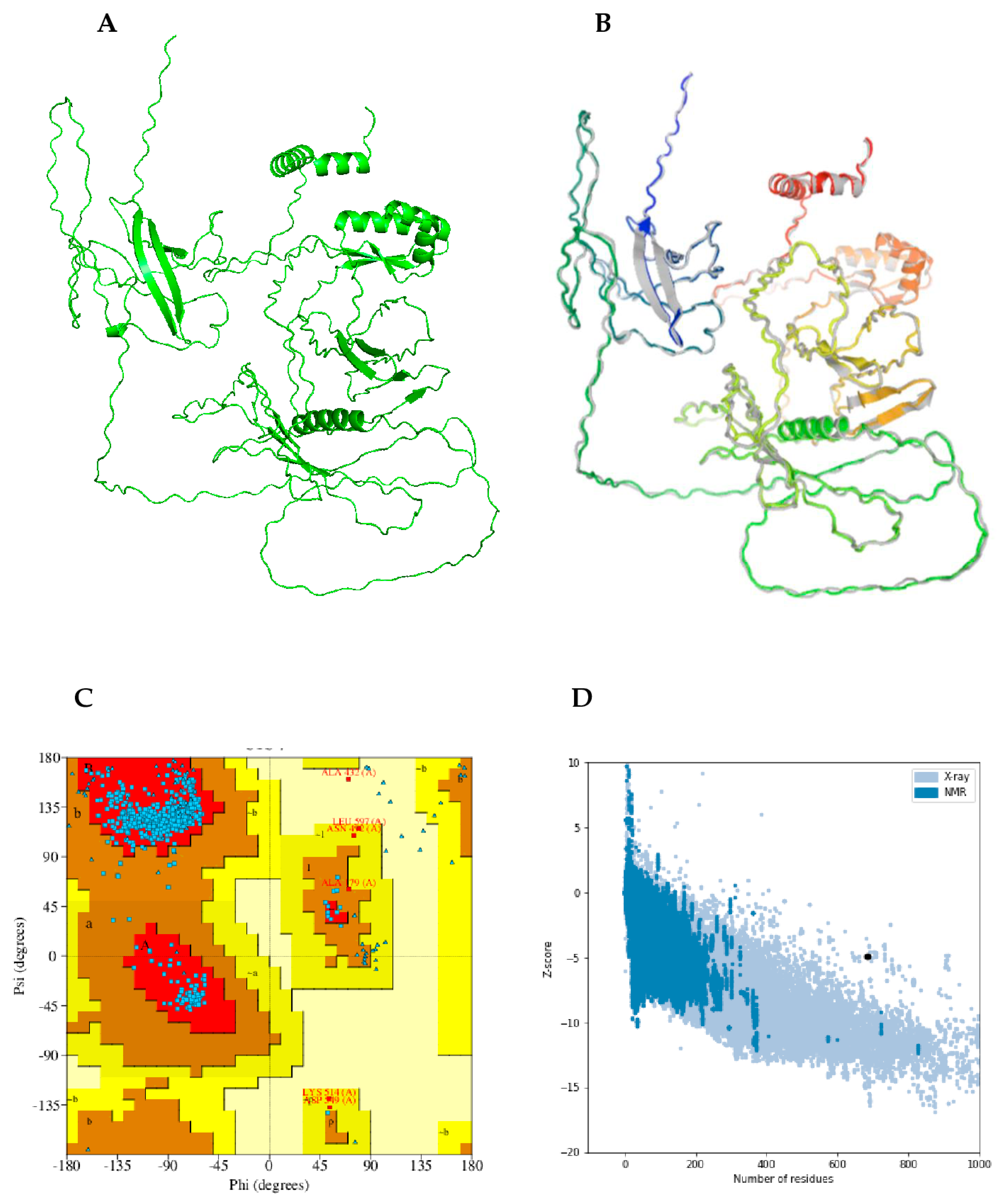

2.13. Prediction, Refinement, and Validation of Modeled Tertiary Structure

2.14. Discontinuous B-Cell Epitope Prediction

2.15. Protein-Protein Docking Between the Designed Vaccine Candidate and TLR4 Receptor Dimer

2.16. Normal Mode Analyses

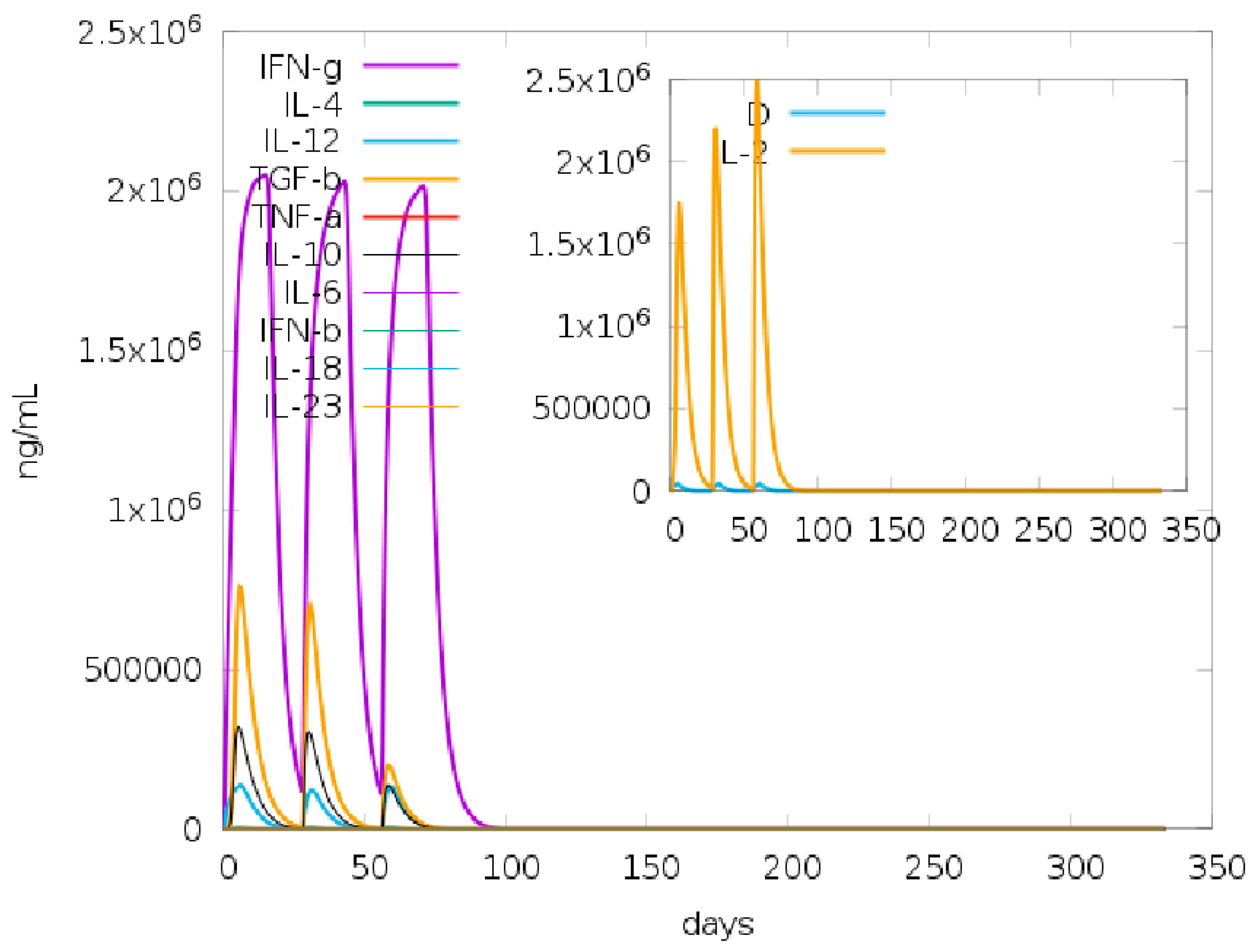

2.17. Immune Simulation for Vaccine Candidate Immunogenicity Analyses

2.18. Codon Optimization and In-Silico Cloning

3. Discussion

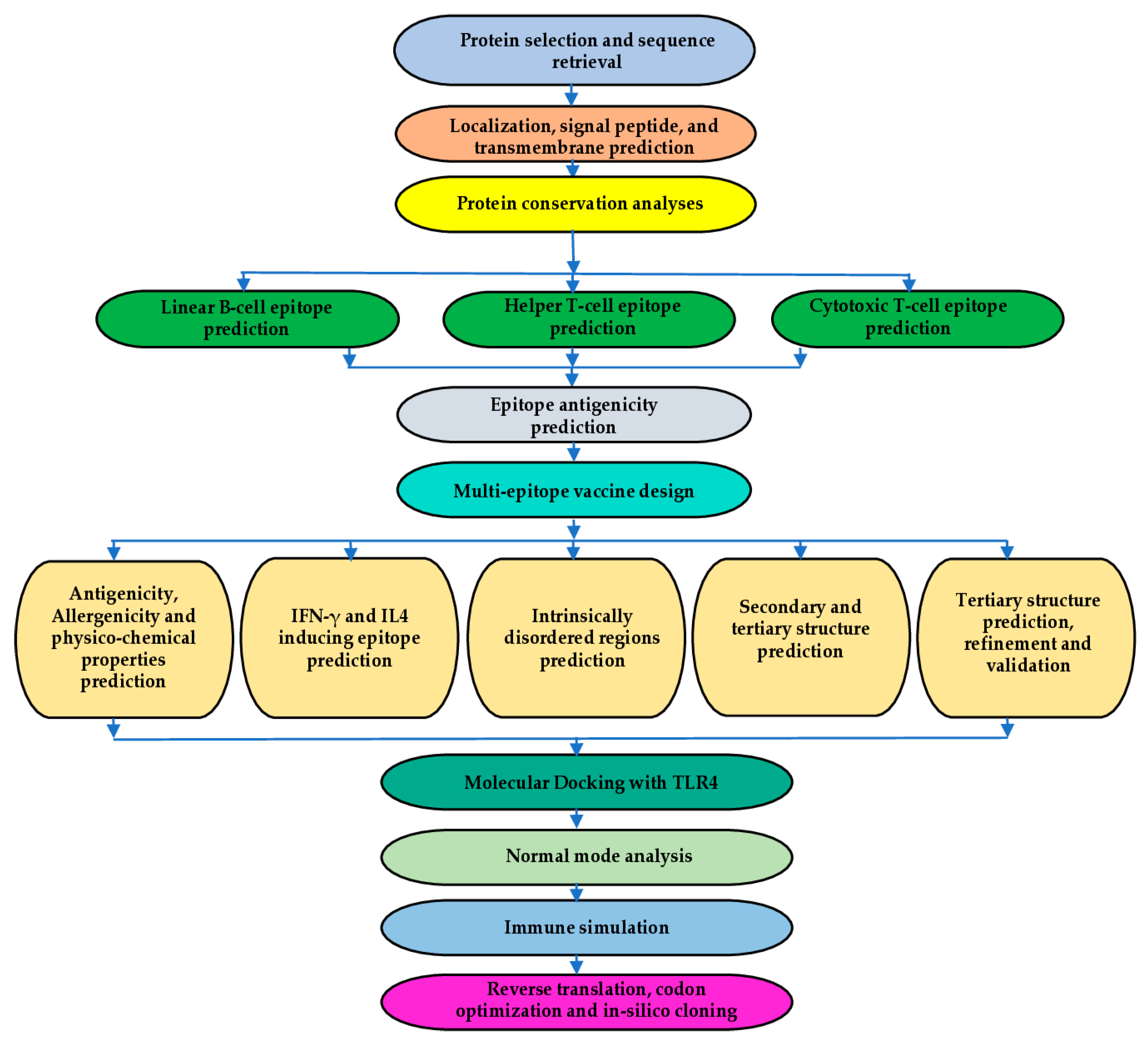

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Protein Sequence Retrieval and Preliminary Analyses

4.2. Protein Conservation Analyses

4.3. Linear B-Cell Epitope Prediction

4.4. T-Cell Epitope Prediction

4.5. Epitope Antigenicity Prediction

4.6. Multi-Epitope Vaccine Candidate Design

4.7. Physicochemical Properties and Solubility Prediction

4.8. Antigenicity, Immunogenicity, Allergenicity, and Toxigenicity prediction

4.9. Secondary Structure and Intrinsic Disorder Prediction

4.10. Antibody Class Prediction

4.11. IFN-γ-Inducing Epitope Prediction

4.12. Prediction of Epitopes for Mouse MHC II Alleles

4.13. Immune Simulation Analyses

4.14. Tertiary Structure Prediction, Refinement, and Validation

4.15. Discontinuous B-Cell Epitope Prediction

4.16. Binding Pocket Prediction, Molecular Docking, Binding Affinity, and Interaction Analyses

4.17. Normal Mode Analyses

4.18. Codon Optimization and In-Silico Cloning

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayalew, S.; Habtamu, G.; Melese, F.; Tessema, B.; Ashford, R.T.; Chothe, S.K.; Aseffa, A.; Wood, J.L.N.; Berg, S.; Mihret, A. Zoonotic tuberculosis in a high bovine tuberculosis burden area of Ethiopia. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1204525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, Á.B.; Floyd, S.; Gordon, S.V.; More, S.J. Prevalence of Mycobacterium bovis in milk on dairy cattle farms: An international systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Tuberculosis 2022, 132, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, B.; Dürr, S.; Alonso, S.; Hattendorf, J.; Laisse, C.J.; Parsons, S.D.; van Helden, P.D.; Zinsstag, J. Zoonotic Mycobacterium bovis-induced tuberculosis in humans. Emerg Infect Dis 2013, 19, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.S.; Sweeney, S.J. Mycobacterium bovis (bovine tuberculosis) infection in North American wildlife: current status and opportunities for mitigation of risks of further infection in wildlife populations. Epidemiol Infect 2013, 141, 1357–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, L.M.; Daborn, C.J. The epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis infections in animals and man: a review. Tuber Lung Dis 1995, 76 Suppl 1, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, J.P.; Moreno, A.; Fina, L.; del Baño, L.; Orcau, A.; de Olalla, P.G.; Caylà, J.A. Factors that influence current tuberculosis epidemiology. Eur Spine J 2013, 22 Suppl 4, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Tuberculosis. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis.

- An, Y.; Teo, A.K.J.; Huot, C.Y.; Tieng, S.; Khun, K.E.; Pheng, S.H.; Leng, C.; Deng, S.; Song, N.; Nonaka, D.; et al. Barriers to childhood tuberculosis case detection and management in Cambodia: the perspectives of healthcare providers and caregivers. BMC Infect Dis 2023, 23, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, C.M.; Dolan, L.; Piggott, L.M.; McLaughlin, A.M. New developments in tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment. Breathe (Sheff) 2022, 18, 210149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiza, H.; Hella, J.; Arbués, A.; Magani, B.; Sasamalo, M.; Gagneux, S.; Reither, K.; Portevin, D. Case–control diagnostic accuracy study of a non-sputum CD38-based TAM-TB test from a single milliliter of blood. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 13190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartois, V.A.; Rubin, E.J. Anti-tuberculosis treatment strategies and drug development: challenges and priorities. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2022, 20, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, C.A.; Dominey-Howes, D.; Labbate, M. The antimicrobial resistance crisis: causes, consequences, and management. Front Public Health 2014, 2, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliori, G.B.; Dheda, K.; Centis, R.; Mwaba, P.; Bates, M.; O’Grady, J.; Hoelscher, M.; Zumla, A. Review of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant TB: global perspectives with a focus on sub-Saharan Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2010, 15, 1052–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, P.C.P.; Messina, N.L.; de Oliveira, R.D.; da Silva, P.V.; Puga, M.A.M.; Dalcolmo, M.; dos Santos, G.; de Lacerda, M.V.G.; Jardim, B.A.; de Almeida e Val, F.F.; et al. Effect of BCG vaccination against <em>Mycobacterium tuberculosis</em> infection in adult Brazilian health-care workers: a nested clinical trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2024, 24, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannon, M.J. BCG and tuberculosis. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1999, 80, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scriba, T.J.; Netea, M.G.; Ginsberg, A.M. Key recent advances in TB vaccine development and understanding of protective immune responses against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Semin Immunol 2020, 50, 101431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L.; Feino Cunha, J.; Weinreich Olsen, A.; Chilima, B.; Hirsch, P.; Appelberg, R.; Andersen, P. Failure of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine: some species of environmental mycobacteria block multiplication of BCG and induction of protective immunity to tuberculosis. Infect Immun 2002, 70, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, J.I.; Allué-Guardia, A.; Tampi, R.P.; Restrepo, B.I.; Torrelles, J.B. New Developments and Insights in the Improvement of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Vaccines and Diagnostics Within the End TB Strategy. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2021, 8, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, A.; Russo, G.; Parasiliti Palumbo, G.A.; Pappalardo, F. In silico design of recombinant multi-epitope vaccine against influenza A virus. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, 22, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanches, R.C.O.; Tiwari, S.; Ferreira, L.C.G.; Oliveira, F.M.; Lopes, M.D.; Passos, M.J.F.; Maia, E.H.B.; Taranto, A.G.; Kato, R.; Azevedo, V.A.C.; et al. Immunoinformatics Design of Multi-Epitope Peptide-Based Vaccine Against Schistosoma mansoni Using Transmembrane Proteins as a Target. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 621706–621706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andongma, B.T.; Huang, Y.; Chen, F.; Tang, Q.; Yang, M.; Chou, S.H.; Li, X.; He, J. In silico design of a promiscuous chimeric multi-epitope vaccine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2023, 21, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shey, R.A.; Ghogomu, S.M.; Shintouo, C.M.; Nkemngo, F.N.; Nebangwa, D.N.; Esoh, K.; Yaah, N.E.; Manka'aFri, M.; Nguve, J.E.; Ngwese, R.A.; et al. Computational Design and Preliminary Serological Analysis of a Novel Multi-Epitope Vaccine Candidate against Onchocerciasis and Related Filarial Diseases. Pathogens 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shey, R.A.; Ghogomu, S.M.; Nebangwa, D.N.; Shintouo, C.M.; Yaah, N.E.; Yengo, B.N.; Nkemngo, F.N.; Esoh, K.K.; Tchatchoua, N.M.T.; Mbachick, T.T.; et al. Rational design of a novel multi-epitope peptide-based vaccine against Onchocerca volvulus using transmembrane proteins. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Multi-epitope vaccines: a promising strategy against tumors and viral infections. Cellular & Molecular Immunology 2018, 15, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs-Simon, A.; Titball, R.W.; Michell, S.L. Lipoproteins of bacterial pathogens. Infect Immun 2011, 79, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandavilli, S.; Homer, K.A.; Yuste, J.; Basavanna, S.; Mitchell, T.; Brown, J.S. Maturation of Streptococcus pneumoniae lipoproteins by a type II signal peptidase is required for ABC transporter function and full virulence. Mol Microbiol 2008, 67, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriela, E.-V.; Susana, F.-V.; Clara, I.E. Virulence Factors and Pathogenicity of Mycobacterium. In Mycobacterium, Wellman, R., Ed. IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2017; 10.5772/intechopen.72027p. Ch. 12.

- Rahlwes, K.C.; Dias, B.R.S.; Campos, P.C.; Alvarez-Arguedas, S.; Shiloh, M.U. Pathogenicity and virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Virulence 2023, 14, 2150449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Z.H.; Sun, R.F.; Lin, C.; Chen, F.Z.; Mai, J.T.; Liu, Y.X.; Xu, Z.Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J. Immunogenicity and Protective Efficacy of a Fusion Protein Tuberculosis Vaccine Combining Five Esx Family Proteins. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minerva, M.; De Maio, F.; Camassa, S.; Battah, B.; Ivana, P.; Manganelli, R.; Sanguinetti, M.; Sali, M.; Delogu, G. Evaluation of PE_PGRS33 as a potential surface target for humoral responses against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Pathogens and Disease 2017, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Shin, S.J.; Lee, M.H.; Lee, M.G.; Kang, T.H.; Park, W.S.; Soh, B.Y.; Park, J.H.; Shin, Y.K.; Kim, H.W.; et al. A potential protein adjuvant derived from Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv0652 enhances dendritic cells-based tumor immunotherapy. PLoS One 2014, 9, e104351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, H.; Kwon, K.W.; Choi, H.H.; Kang, S.M.; Hong, J.J.; Shin, S.J. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling-mediated responses are critically engaged in optimal host protection against highly virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis K infection. Virulence 2020, 11, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, B.; Thieblemont, N.; Quesniaux, V.J.; Brown, N.; Mpagi, J.; Miyake, K.; Bihl, F.; Ryffel, B. Toll-like receptor 4 expression is required to control chronic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J Immunol 2002, 169, 3155–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, H.; Akhtar, S.; Jan, S.U.; Khan, A.; Zaidi, N.; Qadri, I. Over expression of a synthetic gene encoding interferon lambda using relative synonymous codon usage bias in Escherichia coli. Pak J Pharm Sci 2013, 26, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arinaminpathy, N.; Mukadi, Y.D.; Bloom, A.; Vincent, C.; Ahmedov, S. Meeting the 2030 END TB goals in the wake of COVID-19: A modelling study of countries in the USAID TB portfolio. PLOS Glob Public Health 2023, 3, e0001271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portnoy, A.; Clark, R.A.; Quaife, M.; Weerasuriya, C.K.; Mukandavire, C.; Bakker, R.; Deol, A.K.; Malhotra, S.; Gebreselassie, N.; Zignol, M.; et al. The cost and cost-effectiveness of novel tuberculosis vaccines in low- and middle-income countries: A modeling study. PLoS Med 2023, 20, e1004155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Samperio, P. Development of tuberculosis vaccines in clinical trials: Current status. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology 2018, 88, e12710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, P.; Xue, Y.; Wang, J.; Jia, Z.; Wang, L.; Gong, W. Evaluation of the consistence between the results of immunoinformatics predictions and real-world animal experiments of a new tuberculosis vaccine MP3RT. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, F.E.; Moise, L.; Martin, R.F.; Torres, M.; Pilotte, N.; Williams, S.A.; De Groot, A.S. Time for T? Immunoinformatics addresses vaccine design for neglected tropical and emerging infectious diseases. Expert Rev Vaccines 2015, 14, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shey, R.A.; Ghogomu, S.M.; Esoh, K.K.; Nebangwa, N.D.; Shintouo, C.M.; Nongley, N.F.; Asa, B.F.; Ngale, F.N.; Vanhamme, L.; Souopgui, J. In-silico design of a multi-epitope vaccine candidate against onchocerciasis and related filarial diseases. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharaj, L.; Adeleke, V.T.; Fatoba, A.J.; Adeniyi, A.A.; Tshilwane, S.I.; Adeleke, M.A.; Maharaj, R.; Okpeku, M. Immunoinformatics approach for multi-epitope vaccine design against P. falciparum malaria. Infect Genet Evol 2021, 92, 104875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrubio-López, G.P.; González-Y-Merchand, J.A.; Ribas-Aparicio, R.M. Identification of Novel Potential Vaccine Candidates against Tuberculosis Based on Reverse Vaccinology. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015, 483150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, G.; Tamilselvi, C.S.; Lemme-Dumit, J.M.; Heine, S.J.; Dunn, D.; Ndungo, E.; Kapoor, N.; Oaks, E.V.; Fairman, J.; Pasetti, M.F. Shigella virulence protein VirG is a broadly protective antigen and vaccine candidate. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamehri, M.; Rasooli, I.; Pishgahi, M.; Jahangiri, A.; Ramezanalizadeh, F.; Banisaeed Langroodi, S.R. Combination of BauA and OmpA elicit immunoprotection against Acinetobacter baumannii in a murine sepsis model. Microbial Pathogenesis 2022, 173, 105874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.A.; Gálvez, N.M.S.; Andrade, C.A.; Ramírez, M.A.; Riedel, C.A.; Kalergis, A.M.; Bueno, S.M. BCG vaccination induces cross-protective immunity against pathogenic microorganisms. Trends in Immunology 2022, 43, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fromsa, A.; Willgert, K.; Srinivasan, S.; Mekonnen, G.; Bedada, W.; Gumi, B.; Lakew, M.; Tadesse, B.; Bayissa, B.; Sirak, A.; et al. BCG vaccination reduces bovine tuberculosis transmission, improving prospects for elimination. Science 2024, 383, eadl3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, E.M.D.L.; Cooper, D.V.; Rutten, V.P.M.G.; Michel, A.L. Mycobacterium bovis prevalence affects the performance of a commercial serological assay for bovine tuberculosis in African buffaloes. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2020, 70, 101369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, S.; Carugati, M.; Rubach, M.P.; Cleaveland, S.; Mpagama, S.G.; Khan, S.S.; Mfinanga, S.; Mmbaga, B.T.; Crump, J.A.; Raviglione, M.C. 'One Health´ approach to end zoonotic TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2023, 27, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, P.; Patel, S.; Comer, A.; Muneer, S.; Nawaz, U.; Quann, V.; Bansal, M.; Venketaraman, V. Role of B Cells in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinian, K.; Gerami, A.; Bral, M.; Venketaraman, V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis–Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and the Role of T Cells in Protection. Vaccines 2024, 12, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behar, S.M. Antigen-specific CD8(+) T cells and protective immunity to tuberculosis. Adv Exp Med Biol 2013, 783, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; Tjärnlund, A.; Ivanji, J.; Singh, M.; García, I.; Williams, A.; Marsh, P.D.; Troye-Blomberg, M.; Fernández, C. Role of IgA in the defense against respiratory infections IgA deficient mice exhibited increased susceptibility to intranasal infection with Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Vaccine 2005, 23, 2565–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, H.A.; Snowden, M.A.; Landry, B.; Rida, W.; Satti, I.; Harris, S.A.; Matsumiya, M.; Tanner, R.; O'Shea, M.K.; Dheenadhayalan, V.; et al. T-cell activation is an immune correlate of risk in BCG vaccinated infants. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesniaux, V.; Fremond, C.; Jacobs, M.; Parida, S.; Nicolle, D.; Yeremeev, V.; Bihl, F.; Erard, F.; Botha, T.; Drennan, M.; et al. Toll-like receptor pathways in the immune responses to mycobacteria. Microbes and Infection 2004, 6, 946–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branger, J.; Leemans, J.C.; Florquin, S.; Weijer, S.; Speelman, P.; van der Poll, T. Toll-like receptor 4 plays a protective role in pulmonary tuberculosis in mice. International Immunology 2004, 16, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, B.; Crimi, C.; Newman, M.; Higashimoto, Y.; Appella, E.; Sidney, J.; Sette, A. A rational strategy to design multiepitope immunogens based on multiple Th lymphocyte epitopes. J Immunol 2002, 168, 5499–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sette, A.; Livingston, B.; McKinney, D.; Appella, E.; Fikes, J.; Sidney, J.; Newman, M.; Chesnut, R. The development of multi-epitope vaccines: epitope identification, vaccine design and clinical evaluation. Biologicals 2001, 29, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, R.; Ueda, H.; Kitayama, A.; Kamiya, N.; Nagamune, T. Design of the linkers which effectively separate domains of a bifunctional fusion protein. Protein Eng 2001, 14, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.; del Guercio, M.F.; Frame, B.; Maewal, A.; Sette, A.; Nahm, M.H.; Newman, M.J. Development of experimental carbohydrate-conjugate vaccines composed of Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides and the universal helper T-lymphocyte epitope (PADRE). Vaccine 2004, 22, 2362–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.G.; Sayers, E.J.; He, L.; Narayan, R.; Williams, T.L.; Mills, E.M.; Allemann, R.K.; Luk, L.Y.P.; Jones, A.T.; Tsai, Y.-H. Cell-penetrating peptide sequence and modification dependent uptake and subcellular distribution of green florescent protein in different cell lines. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 6298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backlund, C.M.; Holden, R.L.; Moynihan, K.D.; Garafola, D.; Farquhar, C.; Mehta, N.K.; Maiorino, L.; Pham, S.; Iorgulescu, J.B.; Reardon, D.A.; et al. Cell-penetrating peptides enhance peptide vaccine accumulation and persistence in lymph nodes to drive immunogenicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2204078119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Bruyn, E.; Ruzive, S.; Lindestam Arlehamn, C.S.; Sette, A.; Sher, A.; Barber, D.L.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Riou, C. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD4 T cells expressing CD153 inversely associate with bacterial load and disease severity in human tuberculosis. Mucosal Immunology 2021, 14, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, K.; Kinjo, Y.; Uezu, K.; Miyagi, K.; Kinjo, T.; Yara, S.; Koguchi, Y.; Miyazato, A.; Shibuya, K.; Iwakura, Y.; et al. Interferon-γ production and host protective response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice lacking both IL-12p40 and IL-18. Microbes and Infection 2004, 6, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curlin, G.; Landry, S.; Bernstein, J.; Gorman, R.L.; Mulach, B.; Hackett, C.J.; Foster, S.; Miers, S.E.; Strickler-Dinglasan, P. Integrating safety and efficacy evaluation throughout vaccine research and development. Pediatrics 2011, 127 Suppl. 1, S9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouresmaeil, M.; Azizi-Dargahlou, S. Factors involved in heterologous expression of proteins in E. coli host. Archives of Microbiology 2023, 205, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Maheshwari, N.; Chauhan, R.; Sen, N.K.; Sharma, A. Structure prediction and functional characterization of secondary metabolite proteins of Ocimum. Bioinformation 2011, 6, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, P.O.; McLellan, J.S. Principles and practical applications of structure-based vaccine design. Curr Opin Immunol 2022, 77, 102209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Collier, J.H. α-Helical coiled-coil peptide materials for biomedical applications. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameri, M.; Nezafat, N.; Eskandari, S. The potential of intrinsically disordered regions in vaccine development. Expert Review of Vaccines 2022, 21, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Yuan, J.; Pang, Y. Maintenance and recall of memory T cell populations against tuberculosis: Implications for vaccine design. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1100741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieli, F.; Ivanyi, J. Role of antibodies in vaccine-mediated protection against tuberculosis. Cellular & Molecular Immunology 2022, 19, 758–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Liang, Y.; Mi, J.; Jia, Z.; Xue, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, S.; Wu, X. Peptides-Based Vaccine MP3RT Induced Protective Immunity Against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection in a Humanized Mouse Model. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarke, A.; Zhang, Y.; Methot, N.; Narowski, T.M.; Phillips, E.; Mallal, S.; Frazier, A.; Filaci, G.; Weiskopf, D.; Dan, J.M.; et al. Targets and cross-reactivity of human T cell recognition of common cold coronaviruses. Cell Reports Medicine 2023, 4, 101088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UniProt, C. The universal protein resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36, D190–D195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, J.N.; Høie, M.H.; Deleuran, S.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M.; Marcatili, P. BepiPred-3.0: Improved B-cell epitope prediction using protein language models. Protein Sci 2022, 31, e4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Ansari, H.R.; Raghava, G.P. Improved method for linear B-cell epitope prediction using antigen's primary sequence. PLoS One 2013, 8, e62216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.K.; Andreatta, M.; Marcatili, P.; Buus, S.; Greenbaum, J.A.; Yan, Z.; Sette, A.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. Improved methods for predicting peptide binding affinity to MHC class II molecules. Immunology 2018, 154, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.V.; Lundegaard, C.; Lamberth, K.; Buus, S.; Lund, O.; Nielsen, M. Large-scale validation of methods for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 2007, 8, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytchinova, I.A.; Flower, D.R. VaxiJen: a server for prediction of protective antigens, tumour antigens and subunit vaccines. BMC Bioinformatics 2007, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, R.; Ueda, H.; Kitayama, A.; Kamiya, N.; Nagamune, T. Design of the linkers which effectively separate domains of a bifunctional fusion protein. Protein Engineering, Design and Selection 2001, 14, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy Chichili, V.P.; Kumar, V.; Sivaraman, J. Linkers in the structural biology of protein-protein interactions. Protein Sci 2013, 22, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, A.; Onozuka, A.; Asahi-Ozaki, Y.; Imai, S.; Hanada, N.; Miwa, Y.; Nisizawa, T. An ingenious design for peptide vaccines. Vaccine 2005, 23, 2322–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zaro, J.L.; Shen, W.-C. Fusion protein linkers: Property, design and functionality. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2013, 65, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, M.R.; Gasteiger, E.; Bairoch, A.; Sanchez, J.C.; Williams, K.L.; Appel, R.D.; Hochstrasser, D.F. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol Biol 1999, 112, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosano, G.L.; Ceccarelli, E.A. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: advances and challenges. Front Microbiol 2014, 5, 172–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thumuluri, V.; Martiny, H.-M.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Salomon, J.; Nielsen, H.; Johansen, A.R. NetSolP: predicting protein solubility in Escherichia coli using language models. Bioinformatics 2021, 38, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zou, Q. Prediction of protein solubility based on sequence physicochemical patterns and distributed representation information with DeepSoluE. BMC Biology 2023, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnan, C.N.; Zeller, M.; Kayala, M.A.; Vigil, A.; Randall, A.; Felgner, P.L.; Baldi, P. High-throughput prediction of protein antigenicity using protein microarray data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2936–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, K.; Sinha, R.; Abbasi, B.A.; Chaudhary, A.; Nath, S.K.; Kumari, P.; Preeti, P.; Saraf, D.; Singh, S.; Mishra, K.; et al. Identification of vaccine targets in pathogens and design of a vaccine using computational approaches. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 17626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrov, I.; Naneva, L.; Doytchinova, I.; Bangov, I. AllergenFP: allergenicity prediction by descriptor fingerprints. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrov, I.; Bangov, I.; Flower, D.R.; Doytchinova, I. AllerTOP v.2--a server for in silico prediction of allergens. J Mol Model 2014, 20, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand Singh Rathore, A.A., Shubham Choudhury, Purva Tijare, Gajendra P. S. Raghava. ToxinPred 3.0: An improved method for predicting the toxicity of peptides. bioRxiv 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zuallaert, J.; Wang, X.; Shen, H.-B.; Campos, E.P.; Marushchak, D.O.; De Neve, W. ToxDL: deep learning using primary structure and domain embeddings for assessing protein toxicity. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 5159–5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuffin, L.J.; Bryson, K.; Jones, D.T. The PSIPRED protein structure prediction server. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 404–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchan, D.W.A.; Jones, D.T. The PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, W402–W407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRaild, C.A.; Seow, J.; Das, S.C.; Norton, R.S. Disordered epitopes as peptide vaccines. Pept Sci (Hoboken) 2018, 110, e24067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdős, G.; Pajkos, M.; Dosztányi, Z. IUPred3: prediction of protein disorder enhanced with unambiguous experimental annotation and visualization of evolutionary conservation. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, W297–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, T.; Kinoshita, K. PrDOS: prediction of disordered protein regions from amino acid sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, W460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Nag, D.; Baldwin, S.L.; Coler, R.N.; McNamara, R.P. Antibodies as key mediators of protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1430955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadam, K.; Peerzada, N.; Karbhal, R.; Sawant, S.; Valadi, J.; Kulkarni-Kale, U. Antibody Class(es) Predictor for Epitopes (AbCPE): A Multi-Label Classification Algorithm. Frontiers in Bioinformatics 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalvani, A.; Millington, K.A. T Cells and Tuberculosis: Beyond Interferon-γ. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2008, 197, 941–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanda, S.K.; Vir, P.; Raghava, G.P. Designing of interferon-gamma inducing MHC class-II binders. Biol Direct 2013, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapin, N.; Lund, O.; Bernaschi, M.; Castiglione, F. Computational immunology meets bioinformatics: the use of prediction tools for molecular binding in the simulation of the immune system. PLoS One 2010, 5, e9862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeren, O.V.D.; Hatherill, M.; Nduba, V.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Muyoyeta, M.; Brakel, E.V.; Ayles, H.M.; Henostroza, G.; Thienemann, F.; Scriba, T.J.; et al. Phase 2b Controlled Trial of M72/AS01<sub>E</sub> Vaccine to Prevent Tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379, 1621–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, L.; Park, H.; Seok, C. GalaxyRefine: Protein structure refinement driven by side-chain repacking. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, W384–W388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiederstein, M.; Sippl, M.J. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, W407–W410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colovos, C.; Yeates, T.O. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci 1993, 2, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, J.; Bui, H.-H.; Li, W.; Fusseder, N.; Bourne, P.E.; Sette, A.; Peters, B. ElliPro: a new structure-based tool for the prediction of antibody epitopes. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 514–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Chen, C.; Lei, X.; Zhao, J.; Liang, J. CASTp 3.0: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, W363–W367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozakov, D.; Hall, D.R.; Xia, B.; Porter, K.A.; Padhorny, D.; Yueh, C.; Beglov, D.; Vajda, S. The ClusPro web server for protein–protein docking. Nat Protoc 2017, 12, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A.; Hutchinson, E.G.; Michie, A.D.; Wallace, A.C.; Jones, M.L.; Thornton, J.M. PDBsum: a Web-based database of summaries and analyses of all PDB structures. Trends Biochem Sci 1997, 22, 488–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Blanco, J.R.; Aliaga, J.I.; Quintana-Ortí, E.S.; Chacón, P. iMODS: internal coordinates normal mode analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, W271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Reis, M.; Wernisch, L.; Savva, R. Unexpected correlations between gene expression and codon usage bias from microarray data for the whole Escherichia coli K-12 genome. Nucleic Acids Res 2003, 31, 6976–6985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussinov, R. Eukaryotic dinucleotide preference rules and their implications for degenerate codon usage. Journal of Molecular Biology 1981, 149, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein | Localization | |

| DeepLocPro-1.0 | TBpred | |

| P9WK45 | Cytoplasmic membrane | Protein attached to membrane by lipid anchor |

| P9WNF3 | Cytoplasmic membrane | Secreted protein |

| P9WK65 | Cytoplasmic membrane and cell surface | Protein attached to membrane by lipid anchor |

| A5TZX4 | Cytoplasmic membrane | Integral membrane protein |

| I6Y3P1 | Cytoplasmic membrane | Cytoplasmic protein |

| P9WGT7 | Cytoplasmic membrane | Protein attached to membrane by lipid anchor |

| P9WK61 | Cytoplasmic membrane | Protein attached to membrane by lipid anchor |

| Protein | Percentage Identity (%) | |||||||

| M. decipiens | M. leprae | M. lacus | M. gordonae | M. asiaticum | M. bovis | M. riyadhense | M. pseudokansasii | |

| P9WK45 | 91.5 | 68.1 | 81.0 | 70.6 | 72.5 | 100 | 77.5 | 81.8 |

| P9WNF3 | 86.0 | Not found | 83.3 | 77.2 | 75.0 | 100 | 65.8 | 75.0 |

| P9WK65 | 71.6 | 76.4 | 75.9 | 66.4 | 30.9 | 100 | 67.3 | 62.8 |

| A5TZX4 | 84.3 | 61.2 | 37.7 | 63.5 | 60.5 | 99.8 | 62.0 | 60.0 |

| I6Y3P1 | 83.1 | Not found | 85.6 | 79.9 | 79.7 | 100 | 85.3 | 79.1 |

| P9WGT7 | 91.1 | 77.6 | 85.1 | 81.5 | 80.5 | 100 | 84.9 | 82.5 |

| P9WK61 | 87.6 | 43.0 | 81.1 | 80.5 | 69.8 | 100 | 85.7 | 82.5 |

| Protein | LBL | CTL | HTL |

| I6Y3P1 | GGLNSLPLPGTAGHGE | TTFDLTLRR | NDDRKDFVTSLQLLLTFPFPNFGIKQA |

| A5TZX4 | LKSGDTIGLKNSSAYP | ATFDVTLSA WIATLTLEL KSGDTIGLK |

VRDISLRNWIATLTLEL |

| P9WGT7 | TYEIVCSKYPDSQVGT EGARGNDGTSAAAKNTPGSITYN LQSTIGAGQSGLGDNG |

ATTGQASAK NLDGPTLAK SPAWNLPVV |

GNDDNVTGGGATTGQASAKV |

| P9WK65 | DVDVRANPLAAKGVCT YNDEQGVPFRVQGDNI |

SPTASDPAL | |

| P9WNF3 | TYHVIAGQASPSRIDG | TLQGADLTV KLNPDVNLV FLAGCSSTK TLTSALSGK |

INVQAKPAAAASLAAIAIAFLAGCSSTK |

| P9WK61 | GSVVCTTAAGNVNIAI | NVNGVTLGY GLSGCSSNK |

DGKDQNVTGSVVCTTAAGNV TTGSGETTTAAGTTASPGAASGPK |

| P9WK45 | IPGLSLKTL TPRRHCRRI |

ETGDHQLAQAQLDRGSGNS GQNTIRISGKVSAQAVNQ |

| Predicted Linear B-Cell Epitope | Predicted epitope probability (%) | Predicted Antibody Class | |||

| IgG | IgE | IgA | IgM | ||

| GGLNSLPLPGTAGHGE | 66 | + | - | - | - |

| TYEIVCSKYPDSQVGT | 66 | + | - | - | - |

| LKSGDTIGLKNSSAYP | 100 | + | - | + | - |

| EGARGNDGTSAAAKNTPGSITYN | 100 | + | - | - | - |

| DVDVRANPLAAKGVCT | 66 | + | - | + | - |

| LQSTIGAGQSGLGDNG | 100 | + | - | - | - |

| TYHVIAGQASPSRIDG | 66 | + | - | - | - |

| YNDEQGVPFRVQGDNI | 100 | + | - | - | - |

| GSVVCTTAAGNVNIAI | 66 | + | - | - | - |

| Property | Measurement |

| Number of Amino Acids | 683 |

| Molecular Weight | 69.7kDa |

| Formula | C3060H4917N885O959S8 |

| Theoretical pI | 9.36 |

| Instability Index | 27.03 |

| Aliphatic Index (AI) | -0.295 |

| Grand Average of Hydropathicity (GRAVY) | 76.31 |

| Solubility on expression (DeepSoluE) | 0.4218 |

| Solubility on expression (NetSolP 1.0) | 0.4811 |

| Property | Measurement | Remark |

| Antigenicity (VaxiJen v2.0) | 1.1314 | Antigenic |

| Antigenicity (ANTIGENpro) | 0.9218 | Antigenic |

| Antigenicity (VaxiDL) | 96.66% | Antigenic |

| Allergenicity (AllerTOP v2.0) | Probable non-allergen | Probable non-allergen |

| Allergenicity (AllergenFP 2.0) | Probable non-allergen | Probable non-allergen |

| Toxicity (ToxinPred) | Non-toxin | Non-toxigenic |

| Toxicity (ToxDL) | 0.0001 | Non-toxigenic |

| Allele | H-2-IAb | H-2-IAd | H-2-IAk | H-2-IAs | H-2-IAu | H-2-IEd | H-2-IEk |

| Number of epitopes | 78 | 32 | 9 | 22 | 24 | 3 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).