1. Introduction

A major concern in upper limb amputees is the high rate of prosthesis abandonment. Several factors intervene in this decision, among them: discomfort, residual limb pain, weight and cosmesis, high maintenance specially in electric devices, lack of functional benefit, functional superfluity, financial constraints, and insufficient training [

1,

2]. Although emerging technologies have been applied in upper limb prosthesis that include important characteristics like multifunctional, self-identifiable (the degree of acceptance as integral to the body image), durability, and intuitive, there is no significant decrease in the abandonment rate [

2]. Nevertheless, prosthetic training has been shown to play a critical role in acceptance increasing, particularly when the training is of high quality. Also, individuals who express higher satisfaction with their prosthesis tend to feel more motivated and they better understand the training they underwent [

3,

4].

In rehabilitation, emerging technologies based on Extended Reality (XR) can provide users with more engaging experiences than traditional methods. Although these implementations have not reached a wide acceptance in clinical settings [

4].

XR is an umbrella term that encompasses the different points in the continuum Reality-Virtuality first described as mixed reality by Milgram and Kishino [

5]; it includes Virtual Reality (VR), computer-generated interactive 3D scenarios, and Augmented Reality (AR) that blends virtual elements into real-world environments [

4,

5]. However, limited research has explored virtual effectiveness in prosthetic training, and existing studies still have to demonstrate whether the learned skills in these settings can be effectively transferred to real-life prosthesis use [

3,

4].

In this paper is presented a proposal that comprises sensor-driven XR in training for the use of upper limb prosthetics. The proposal is based on virtual scenarios for training, where the movement and power of the stump muscles can be retrieved through a photoplethysmography (PPG) sensor reflective to the system. The model aims to personalize the prosthesis for the individual while training.

2. Related Work

Both VR and AR training have been associated with improvements in prosthetic use performance and the satisfaction of the user among individuals using upper limb prostheses [

2,

6]. In general, VR reports rapid skill acquisition and measurable gains in performance [

6,

7]. While in contrast, AR studies emphasize positive user experience and effective transfer from simulated to real tasks [

8].

VR have been experimented for efficient training in upper extremity amputees. In [

6], thirteen military personnel with upper extremity amputations learned to control a virtual avatar. Residual limb muscle contraction patterns were accurately interpreted as commands. The study provided evidence that the cortical representation of the hand persists long after limb loss, especially when individuals maintain active engagement through phantom movement or prosthesis use. The study challenged old models of brain plasticity, opening new approaches for prosthetic training, design, and neurological rehabilitation strategies.

More recently, in [

9] was conducted a study to understand the VR use as a pre-prosthetic training tool to assist individuals with upper limb loss, before they received a physical prosthesis. With the aim of improving the prosthesis selection process through shared patient-clinician decision-making. The authors highlighted that VR offers a safe, immersive, and interactive environment to explore and for skill development; a user-centered approach. Results suggested that exposure to VR-based prosthesis simulation enhanced the user understanding, the motor planning, and the device expectations. The prototype was a game-like VR environment with tasks designed to mimic real-life prosthetic use; motion capture and electromyography EMG-based control that simulates prosthetic hand movement; and real-time feedback of performance tracking. As the authors mentioned, further clinical trials with larger participant samples are required to validate long-term outcomes and standardize implementation strategies.

Using AR technology, in [

3] was explored the effectiveness of a game designed to improve motor learning and functional performance for users of upper limb prostheses. The game consisted of the use of hand gestures to interact with holograms in a real-life environment. The users observed a scene of six virtual, differently colored plastic cups displayed on a virtual table. Pictured above the table and cups were six smaller cups arranged in a pyramid by random color orientation, as the reference image. The participants then selected and positioned the holographic cups using direct touch with the prosthesis, as if they were picking up a real object. As a result, the AR game showed strong potential for enhancing motor learning, user engagement, and functional ability in upper limb prosthetic users. Although, the authors pointed out that future research should focus on customized fittings, long-term impact, and expanding the game’s complexity to further improve training effectiveness.

The study presented in [

10] developed and evaluated an AR system that supports upper limb amputees in prosthesis training, particularly during the post-surgical period before receiving the prosthesis. The system integrates AR with tactile and proprioceptive feedback, and electromyography (EMG) signal control for an immersive rehabilitation experience. Tasks consisted of picking and placing virtual object under varying conditions of location and orientation. Results showed that feedback (touch and proprioception) significantly reduce task time and muscle effort, and it was especially helpful in tasks requiring accurate object manipulation and hand rotation. Also, that tasks requiring limb rotation and diagonal movements were more challenging and took longer. According to the authors, the study demonstrated the feasibility and potential of AR prosthesis training system with multisensory feedback. The inclusion of vibrotactile and proprioceptive cues enhanced motor performance, reduced effort, and may improve prosthesis acceptance. Future work should explore more complex tasks, fatigue management, and long-term impacts in actual amputee populations.

According to [

4] , who conducted a review on the use of XR for training of upper limb amputees, the development in XR-based rehabilitation for prosthetic users remains primarily in prototype research settings, with a limited number of participants involved. They concluded that XR has the potential to create a structured, self-directed learning environment that functions both in clinical settings and at home. Authors pointed out that while XR technologies for upper-limb prosthetic rehabilitation hold great potential, achieving meaningful impact will require a patient-centered and value-driven strategy to overcome the current barriers to adoption in clinical practices. As a limitation, the authors pointed out that all participants used the same bypass prosthetic device, which does not fully replicate an amputee’s customized experience.

In these studies, the potential of VR and AR for prosthesis training was established. In the proposed prototype is presented the design and validation of a pre-prosthetic training system based on XR. A reflective PPG optical sensor is used instead of a more common surface EMG, to detect voluntary muscle contractions forms; to the best of our knowledge, PPG sensors have never been used with this purpose. This approach seeks to personalize the training experience, facilitating the transition to the use of functional prostheses, and reducing technical and economic barriers that still limit access to effective rehabilitation programs. This proposal lies in its holistic, practical design for a user-centered training solution to directly reduce prosthesis abandonment; it provides a concept for developing a tangible tool for clinical practice lowering costs.

3. XR Prototype Circuit

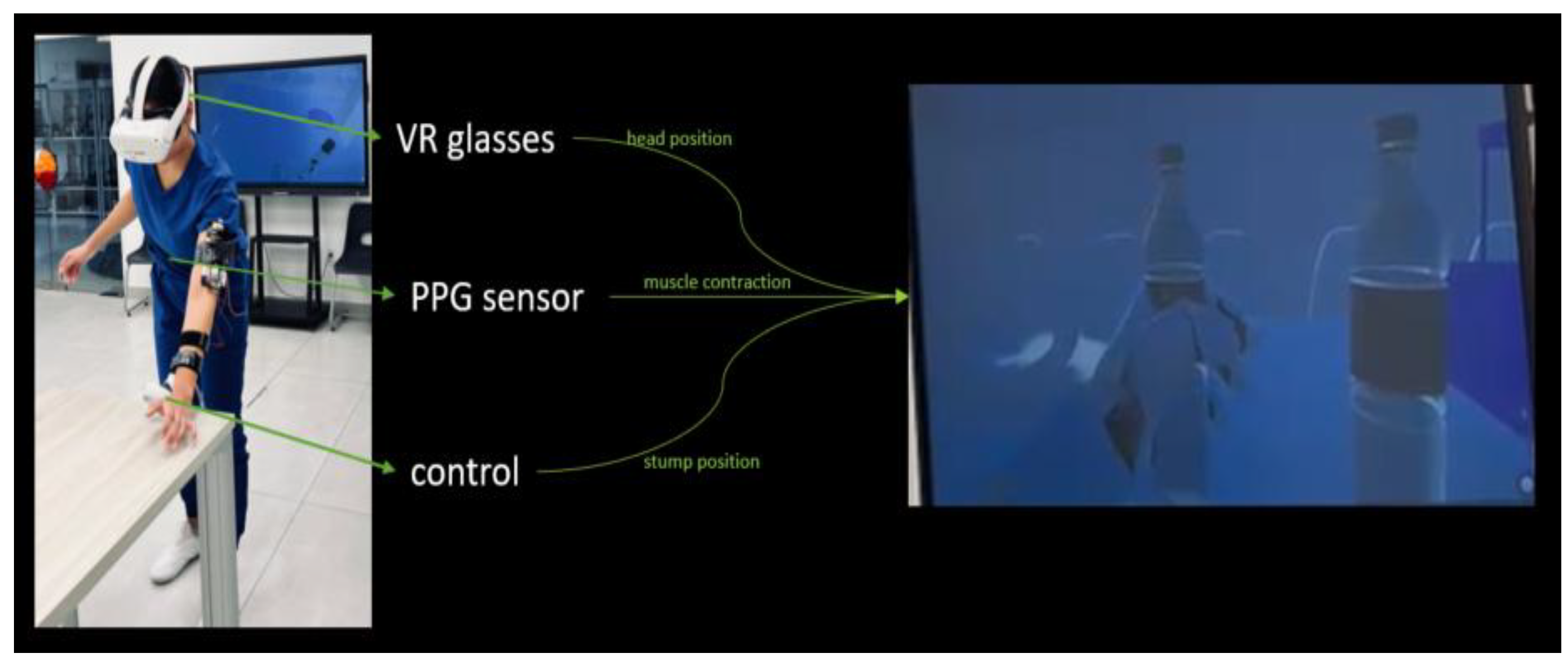

The XR scenario was developed in Unity

TM 3D version 6.1 making use of its XR Interaction Toolkit package. It was implemented considering real stage barriers; this includes a pillar, some chairs, and tables for the tasks (see

Figure 1). The virtual scenario manages the physics of the real stage. The user can see his movements simulated in the virtual scenario through virtual reality glasses: Oculus

TM Quest 2. A reflective optical sensor of surface type PPG placed at the user’s forearm is connected to the virtual scenario. The prototype software interprets the fluctuations in the PPG sensor signal as binary muscle contractions commands, allowing the virtual hand to be controlled within the environment, see

Figure 1.

The most used sensor for prosthesis is the EMG sensor, a device that measures the electrical signals produced by the muscles [

11]. In the context of a prosthetic hand, an EMG sensor works by placing electrodes on the skin over a muscle in the residual limb. These signals are a result of the nerve impulses sent from the brain to the muscles when there is an intend to move it. The EMG sensor detects the electrical signals and sends them to the prosthetic device's control system, then the system interprets these signals as commands. EMG sensors typically require constant calibration, and they are susceptible to interferences [

12].

As a novel alternative, we propose the photoplethysmography or PPG sensor, a simple, non-invasive technology that measures the amount of light absorbed or reflected by the skin to detect changes, for example, in blood volume. The sensor shines a light (usually green or infrared) onto the skin, and it measures how much of that light bounces back. When the heart beats, blood flows through the arteries and capillaries, causing a temporary increase in the volume of blood under the skin. The increased blood volume absorbs more light, so less light is reflected back to the sensor. By tracking changes in light absorption, the sensor can detect a pulse and calculate heart rate. But as darker skin has more melanin in the epidermis, and melanin is a strong absorber, especially at shorter wavelengths used by many devices (≈530 nm, green), that extra absorption attenuates the light that returns, lowering the AC (alternating current) signal and SNR (signal to noise ratio), so heart-rate and related readings are more error-prone [

13].

PPG sensors are a very common technology, widely used in consumer electronics and therefore, manufactured at a massive scale, driving the cost in contrast with EMG sensors that require more complex signal processing, which makes them more expensive. In PPG, the LED light must enter the skin and come back to the photodetector.

In our prototype, the PPG sensor uses a white LED light. A white LED is not a single wavelength of light; it is a combination of all the colors of the visible light spectrum. Then, the different wavelengths of light that penetrate the skin gather a richer set of data to perform more complex analyses than a sensor with a single-color LED.

The PPG sensor system was adapted through a custom electronic interface, which converts analog signal variations into digital inputs recognized by the XR application. This allows the user to open and close the virtual hand in real time. The virtual glasses automatically adjust the height of the user and the position of the forearm or the stump.

The commercial controls for the VR are intended for able-bodied people, an adaptation to place them through tapes and Velcro

TM was made (see

Figure 2) with the intention to put them in the forearm. The human hands have a very high density of mechanoreceptors that detect pressure, vibration, and texture. And, while the forearm has a much lower density of these receptors, and therefore it is less sensitive to tactile and vibrational feedback, it is still a viable location for this feedback because the user can learn to associate the sensation with a specific action or state. This represents a key challenge for functional and intuitive prosthetics development [

14]. In this prototype, the users receive control vibration feedback when they are able to grip a virtual object. In the scenario, several objects are placed for different tasks (as shown in

Figure 1).

The prototyping involved a staged validation process. Given the challenges associated with recruiting a representative participant pool, the initial proof of concept was made on able-bodied subjects before being tested on a volunteer with a double upper-limb amputation to assess the system's real-world usability and adaptation. The adaptable training module was designed for both unilateral and bilateral amputees.

4. Materials and Methods

This proof of concept represents a critical step in developing an effective XR training scenario for upper-limb amputees. While existing research has demonstrated the potential of XR for improving prosthetic use, a significant gap remains in translating these foundational concepts into a cohesive, user-friendly system.

The primary contribution of the prototype lies in the seamless integration of a physical sensor that measures muscle activity with a responsive, real-time virtual environment (VE). This proof of concept validates the core functionality: demonstrating that the adapted muscle sensor can provide reliable input to control a virtual hand to perform simple, defined tasks.

An important factor to consider in XR training, given the high propensity for VRISE (Virtual Reality-Induced Symptoms an Effects), is directly dependent on the user's ability to acclimatize quickly to the simulated environment [

15]. Therefore, the use of short, high-intensity training epochs limiting session duration mandate a training focused in the user's cognitive resources, promoting the fast recalibration of the visual and vestibular systems required to resolve the sensory conflicts inherent in VR. A vital principle for maintaining a positive safety experience for the user in virtual training.

Task. Diverse tasks were planned inspired by the Cybathlon [

14]; In the end, four chosen tasks were designed to test different skills, as described in

Table 1. Each one tested a particular grip type. Task descriptions and specific material are stated in the second and third column in

Table 1.

When the grip changes to fine grip, the muscle reading is the same. But the simulator by default uses the grip point in the palm, and with the fine grip, the simulation changes the grip to the tip of the index finger. To make the change, the user has to contract and release the muscles within a threshold of less than 0.5 sec. This represents a simple if-then-else rule, as can be seen in the next pseudocode:

// Detect keyboard input

WHILE_GAME_IS_RUNNING

KeyPressed = READ_INPUT("0")

// Use InputSystem to detect key "0"

IF KeyPressed IS TRUE AND EQUALS 1

PERFORM_GRAB_ACTION()

ELSE IF KeyReceivedTime < 0.5 sec

PERFORM_FINE_GRIP()

END IF

END WHILE

Participants. Sixteen medicine students on their clerkships, volunteer to participate. None of them with previous experience in immersive virtual reality applications. Ten were male and six were females able-bodied, with an age range of 20 to 30 years old. Their skin tones were taken as a variable that might affect the sensor reading. All participants provided informed written consent for the anonymous use of their data, prior to their enrollment in the study.

The tasks were conducted with the left arm, since this was the selected arm by the amputee participant.

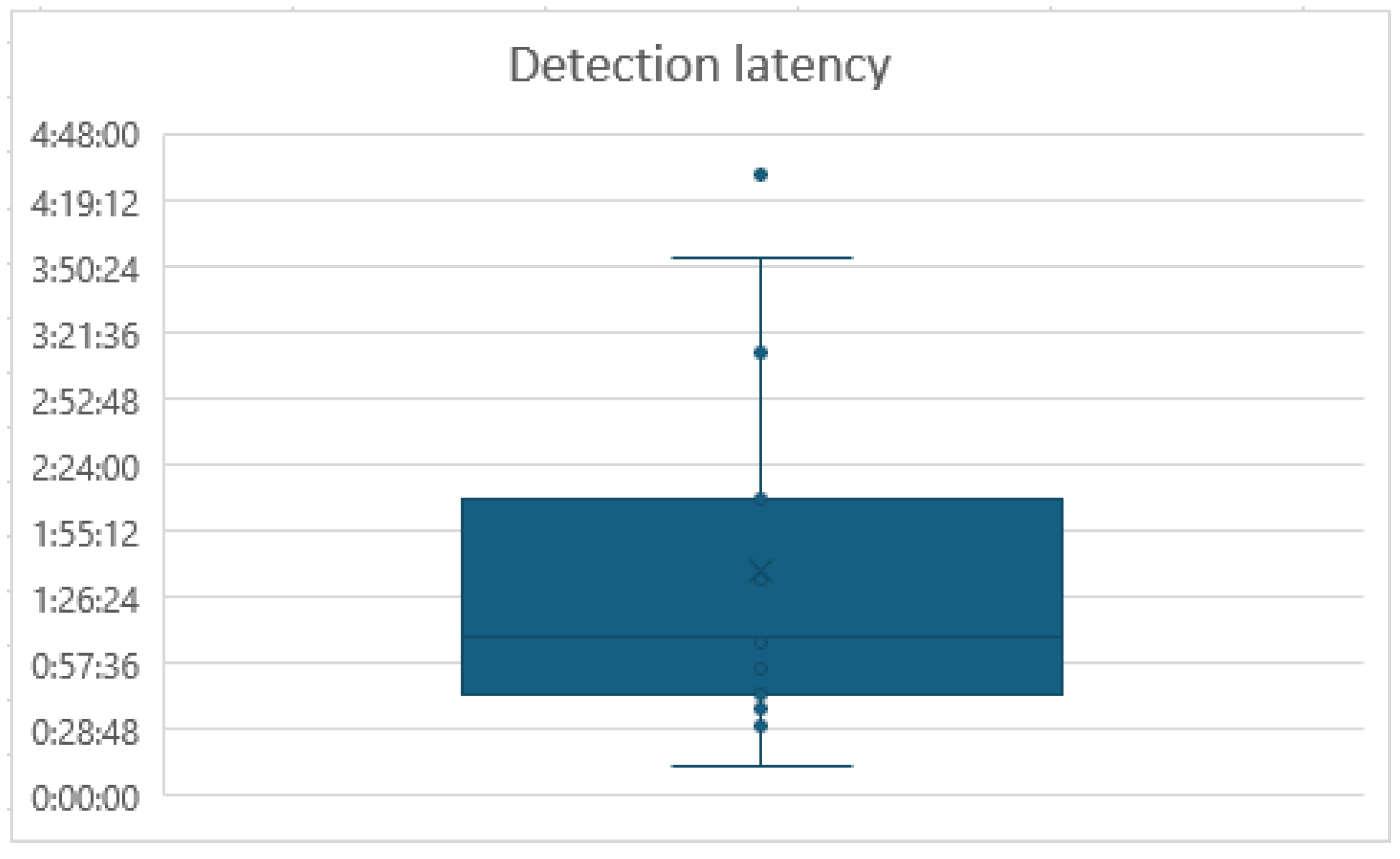

Data. Before the sensor was placed, a characterization had to be made by measuring the detection latency, that is, the time it takes from a user’s muscle contraction to the sensor reading.

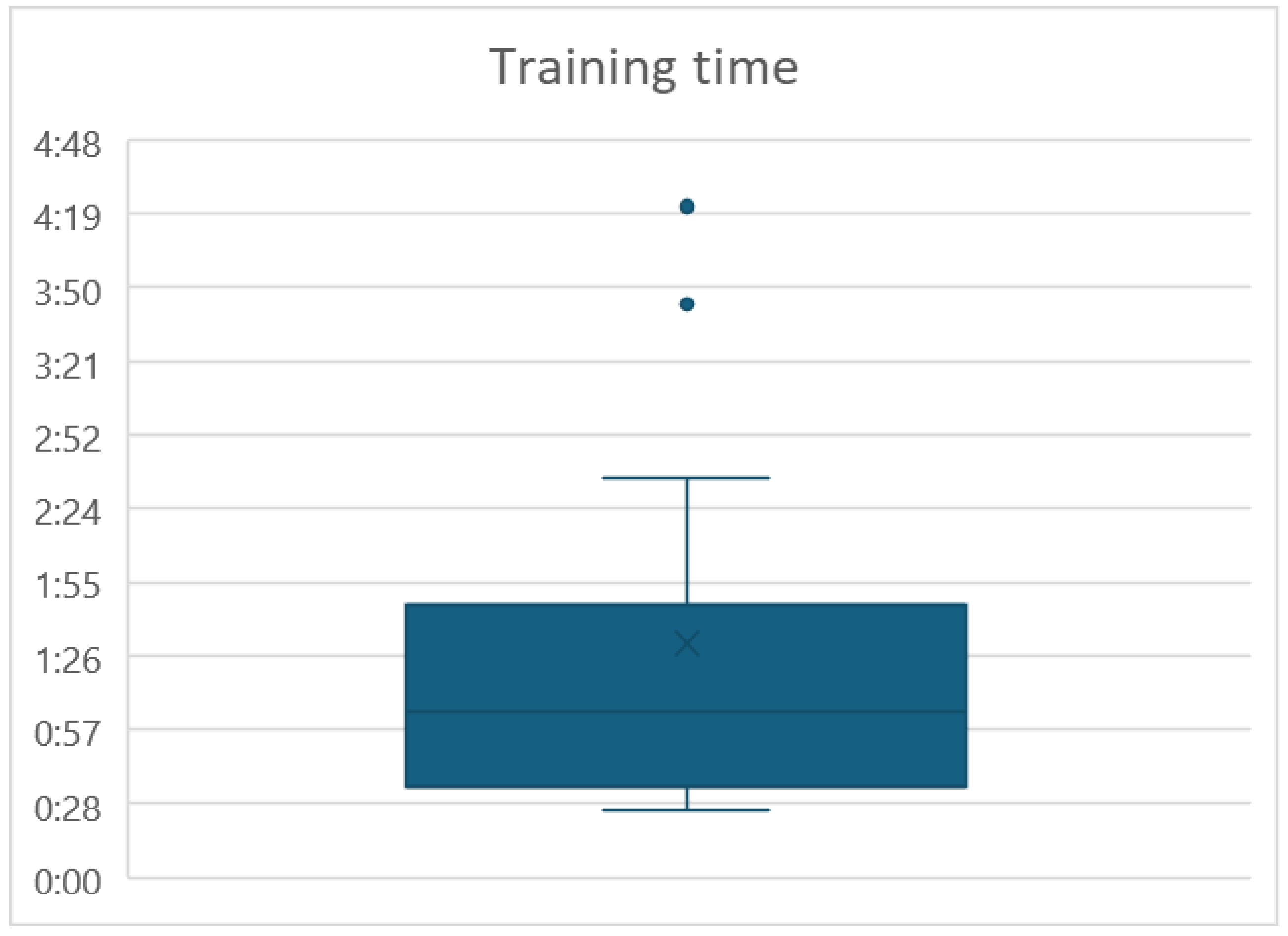

All users had a training session in which they were asked to pick up a virtual bottle and release it at least three times in a row, before starting the tasks.

The time each participant took to complete each task was recorded; mean and standard deviation were calculated.

4.1. Able-Bodied Participants’ Tests

An important issue reported in the literature regarding PPG sensors is the integrated interaction between the emitted light and melanin, the pigment responsible for skin color; as a result, a much lower SNR for users with darker skin has been found with potentially inaccurate readings compared to users with lighter skin tones [

16]. Therefore, it was decided to take the skin tone color of the participants who were demographically and optically representative of the region of the study, similar to the amputee volunteer.

The Monk skin tone (MST) [

17] was selected because it was created to address limitations in older scales with less representative skin tones, predominantly based on lighter skin types.

Table 2 present the results of the characterization and training processes. First column with a given number for the participant (ID), then the sex of the participant, third column shows the time for the participants to control the contraction for the sensor reading (Detection latency), the fourth column represents the time they took to pick three times virtual bottle (Training time), and the last fifth column has their skin color according to the MST scale.

The mean of the Detection latency was 01:37 min and the standard deviation was 00.05 min.

Figure 3 shows the graphic box plot of this data, where can be observed an outlier, with 04:30 min.

For the Training time, the mean was 01:31min and the standard deviation was 00:49 min. Two outliers were found, see

Figure 4. Participants ID 1 and 4 took 04:22 min and 03:44 min, respectively.

The correlation coefficient between the Detection latency and the participant's MST value was found to be r = -0.13. And the correlation coefficient between the Training time and the MST value was found to be r = -0.19. Both values indicating a weak, negligible negative linear association, showing a lack of statistical significance, meaning that the skin color is substantially independent of the Detection latency and the Training time.

In

Table 4 is presented the time it took each participant to complete the four tasks. At the bottom of

Table 4 are the media and deviation standard for each column.

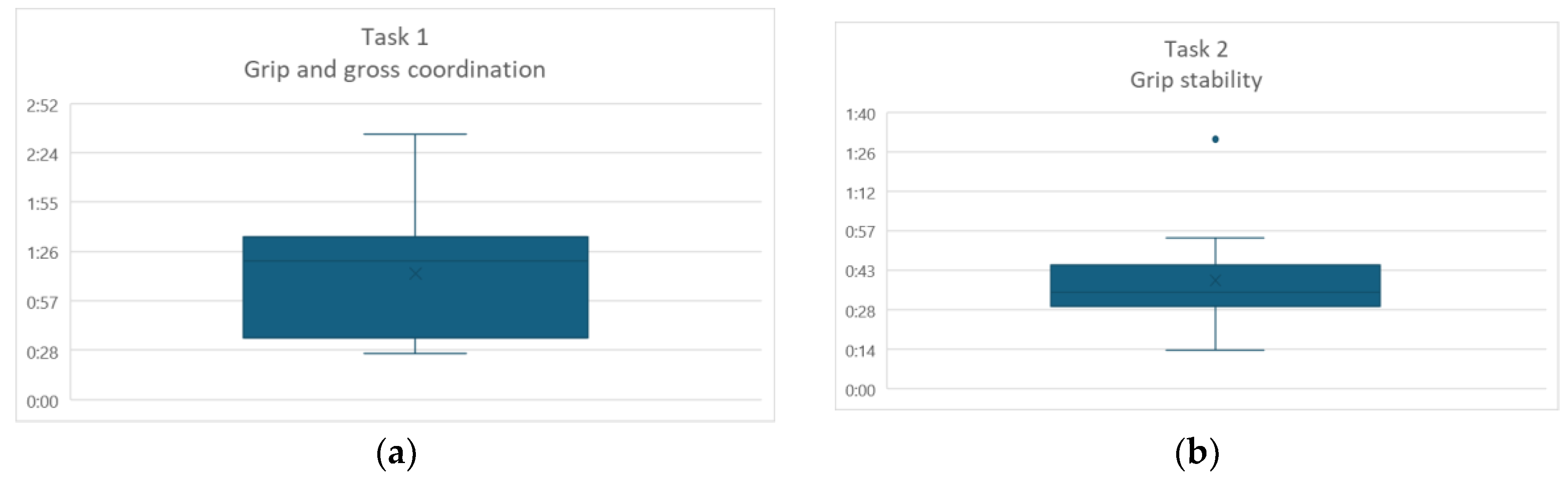

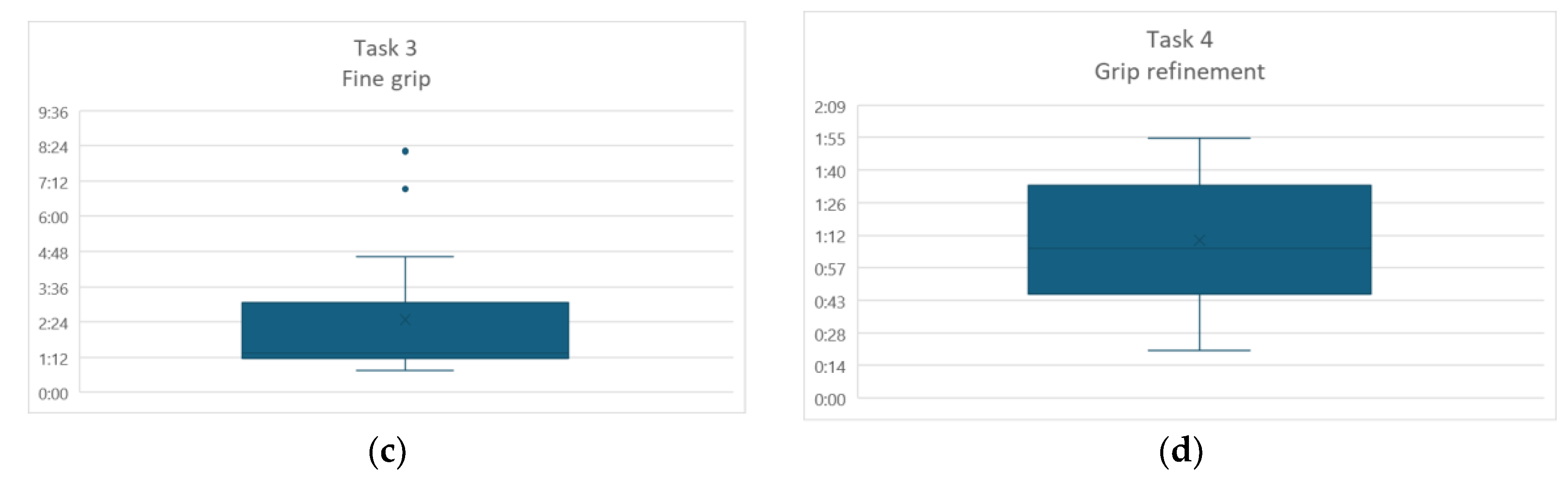

The task that took a longer was Fine grip, which is also the one with a higher standard deviation. In

Figure 5 are presented the four box plot graphics for each task.

Discussion

In the Detection latency, for the outlier participant, an unusually long time span was presented. This participant, ID number 13, is a physically developed athlete with great muscle mass. Data may highlight a potential inverse relationship between muscle size and the sensor data acquisition. This suggest that while optimized for strength and power, athletic arms could interfere to characterize the sensor at first.

As of Training time, the two outliners expressed difficulty in recognizing the vibration of the control in the forearm. But once they learned to recognize the vibration feedback, they were able to pass the training session.

No significant correlation was found between the skin tone with the Detection delay or the Training time. Although the participants in the scale were only in the range of 2 to 8, this reflects the demographic target regional population. This is an indicator that the white light was a proper selection for the PPG sensor, at least for this demographic target.

As can be observed in

Figure 5, in the first task, most of the participants were below the media. In the second task, most participants are around the media, but for participant ID 12, it took more than a minute to complete the task, with no apparent reason.

The task that took longer was the Fine grip, and it has two outliers. In this task the participants grip the glass and then change to a fine grip to grip a fork and a plate. The fork must be held by the handle and the plate from the circumference; participants were instructed on this regard, but they just forgot when they were in the immersive scenario. It should be noted that this was the first time they were experiencing this type of environments. Another problem presented in this task was that sometimes, even when they had already griped the objects, they deconstructed the muscles and the object would fall. Sometimes, for the fallen objects, there was a problem with the actual hand hitting real objects because of a not perfect match with the virtual environment and the floor.

In the final task, although more with disperse data than task 2, most of the participants were around the media.

After the sessions with able-bodied subjects, a preliminary test with an amputee participant was conducted.

4.2. Amputee Participant Test

Participant. A female participant, 30 years old, voluntarily participated on testing the prototype. She presents a bilateral amputation at the transradial level (middle/distal third), her time since amputation is approximately one year. According to her medical diagnosis, the muscle strength is grade 4, observed in flexion and extension of both elbows, according to the Daniels scale. And the joint range of motion is full, unrestricted, active bilateral joint movement. Her MST is 4.

The amputee participant wanted to do the test in her left hand, which is not her dominant hand. She is in the way to receive a right-hand prosthesis, and we followed her wishes. She also provided informed written consent for the anonymous use of her data prior to the study.

Results. The Detection latency was 10:20 min, which was somehow expected; the main reason was that the participant verbally expressed not remembering how to move the non-dominant hand muscles. Fortunately, after several attempts, she managed to properly send the signal to the sensor. The sensor Training time was 02:17 min, only marginally higher than the able-bodied people’s mean (01:37 min), but not enough to be an outlier.

The time it took the amputee participant for each task is presented in

Table 5.

In

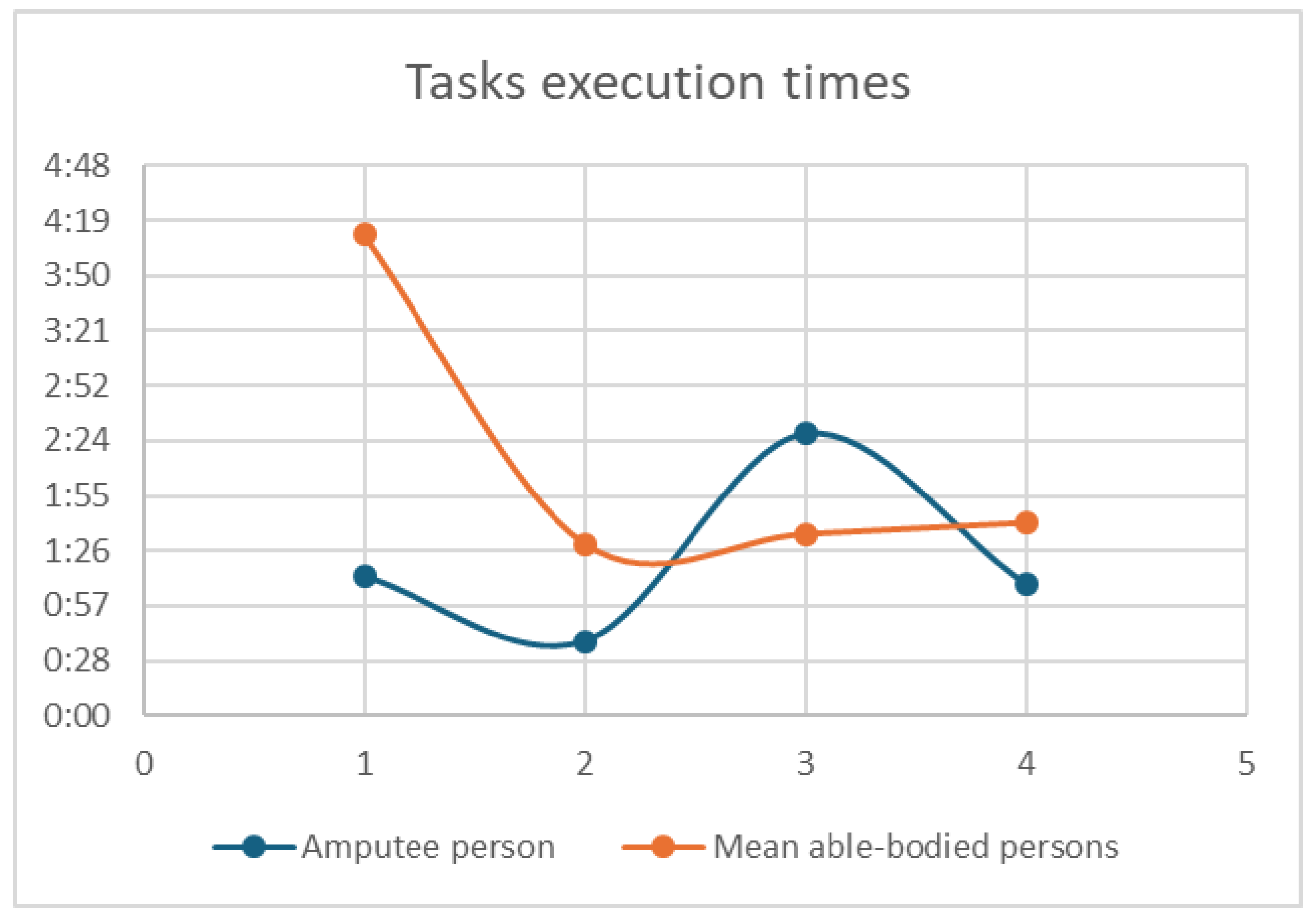

Figure 6, a dot plot graphic shows a contrast of the point of the mean of the able-bodied persons in red, and the times of the amputee person in blue.

4.3. Discussion

The single-subject feasibility trial with the upper-limb amputee participant yielded crucial insights, particularly regarding the initial learning curve and the functional viability of the novel PPG-based control.

The most significant finding was the unusually protracted Detection latency of 10:20 min. This extended period was explicitly attributed by the participant to muscle memory decay and the difficulty in isolating the intended contraction for the non-dominant limb, a challenge inherent in bilateral amputation rehabilitation.

Critically, once this initial sensor-muscle relationship was established, the subsequent Training time (02:17 min) was only marginally higher than the mean for able-bodied subjects (01:37 min). This suggests that while the initial kinesthetic relearning takes time, the system's training efficacy once signals are successfully captured is competitive with able-bodied performance, validating the system's core principle of fast adaptation post-calibration.

Analysis of the task execution times (in

Figure 6) reveals a complex yet promising pattern. The amputee participant took significantly longer on Task 1 (Grip and Gross Coordination), which requires repetitive, fundamental signal control to place objects. However, in the more demanding tasks that require sustained, fine control (Task 3: Fine grip) and sequential motor output (Task 4: Grip Refinement), the participant's execution times were remarkably close to, or even lower than, the mean time of the able-bodied cohort.

This convergence of performance demonstrates the potential for rapid functional integration. The amputee participant’s ability to perform complex tasks quickly suggests that the cognitive load related to kinesthetic control transitions from signal identification (slow initial delay) to real-time motor planning (fast execution) efficiently within the VR environment. This is a powerful indication that the XR system effectively facilitates the necessary sensorimotor remapping required for prosthetic control.

5. Conclusions

Through this proof of concept, we consider that the proposal of the sensor-driven XR prototype for pre-prosthetic kinesthetic learning, established the feasibility of utilizing an adapted photoplethysmography (PPG) sensor as a low-cost, non-invasive, and effective alternative to traditional EMG for muscle contraction detection.

The PPG sensor, leveraging a white LED for broad spectral penetration, demonstrated robust performance across a range of skin tones (MST 2-8). The correlation analysis (i.e., r = -0.13 for detection latency and r = -0.19 for training time) confirmed that system performance is independent of skin color.

The virtual environment showed a short, high-intensity training epoch. Able-bodied subjects required a mean training time of only 01:37 min, demonstrating the protocol’s efficiency in inducing rapid sensorimotor adaptation, which is crucial for mitigating VRISE.

The trial with a single amputee participant, despite an expected initial detection latency (i.e., 10:20 min) due to muscle memory challenges, showed rapid functional execution in subsequent tasks. This supports the assumption that the XR system facilitates the necessary neuro-remapping required for intuitive prosthetic control.

The consistently longer execution times and higher standard deviation for fine grip suggest that quick transitioning between grip modes and maintaining sustained, subtle muscle tension remains the most challenging aspect of control and requires greater focus in the future.

The performance of the proof of concept opens several future works. Mainly a full clinical trial with a larger cohort of amputees to formally assess skill transfer to a physical prosthesis, and reduction in eventual device abandonment rates has to be conducted.

Also, several technical improvements for the sensor have to be done. It is required to develop algorithms to translate the PPG signal from a simple binary (on/off) command to a proportional control system, allowing for variable grip strength and modulated force feedback, thus enhancing the dexterity offered by the virtual prosthetic. The system should dynamically adjust task complexity and session length based on real-time biofeedback to maintain optimal training efficacy and user comfort. Too, it can be explored the inclusion of tactile or vibrotactile feedback on the stump itself, moving beyond control vibration, to further enrich the sense of proprioception and functional self-efficacy during virtual interaction.

References

- Biddiss, E. A.; Chau, T. T. ‘Upper limb prosthesis use and abandonment’. Prosthet Orthot Int 2007, vol. 31(no. 3), 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, T. J.; Fergason, J. R.; Pierrie, S. N. ‘Technological Advances in Prosthesis Design and Rehabilitation Following Upper Extremity Limb Loss’. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2020, vol. 13(no. 4), 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauren. Deus, ‘Augmented Reality for Advanced Prosthetic Training in Non-Amputees’. Dissertation/Thesis, University of Rhode Island, Rhode Island, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gaballa, A.; Cavalcante, R. S.; Lamounier, E.; Soares, A.; Cabibihan, J.-J. ‘Extended Reality “X-Reality” for Prosthesis Training of Upper-Limb Amputees: A Review on Current and Future Clinical Potential’. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2022, vol. 30, 1652–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, P. ; K. F. ‘A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays’. IEICE TRANSACTIONS on Information and Systems 1994, vol. 77(no. 12), 1321–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, B. N. , ‘Virtual Integration Environment as an Advanced Prosthetic Limb Training Platform’. Front Neurol 2018, vol. 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo Sanz, J. , ‘Training in the Use of Myoelectric Prostheses Through the Combined Application of Immersive Virtual Reality, Cross-education, and Mirror Therapy’. JPO Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics 2025, vol. 37(no. 3), 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschmann, A.; Neuhaus, D.; Vogt, S.; Kaltschmidt, C.; Platzner, M.; Dosen, S. ‘Immersive augmented reality system for the training of pattern classification control with a myoelectric prosthesis’. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2021, vol. 18(no. 1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Raghibi, L. , ‘Virtual reality can mediate the learning phase of upper limb prostheses supporting a better-informed selection process’. Journal on Multimodal User Interfaces 2023, vol. 17(no. 1), 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. , ‘A Mixed-Reality Training Environment for Upper Limb Prosthesis Control’. 2018 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), Oct. 2018; IEEE; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triwiyanto, T. , ‘State-of-the-Art Method in Prosthetic Hand Design: A Review’. Journal of Biomimetics, Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering 2021, vol. 50, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Min, H.; Wang, D.; Xia, Z.; Sun, F.; Fang, B. ‘A Review of Myoelectric Control for Prosthetic Hand Manipulation’. Biomimetics 2023, vol. 8(no. 3), 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardulla, F. , ‘Photoplethysmograhic sensors, potential and limitations: Is it time for regulation? A comprehensive review’. Measurement 2023, vol. 218, 113150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserta, G. , ‘Benefits of the Cybathlon 2020 experience for a prosthetic hand user: a case study on the Hannes system’. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2022, vol. 19(no. 1), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conner, N. O. , ‘Virtual Reality Induced Symptoms and Effects: Concerns, Causes, Assessment & Mitigation’. Virtual Worlds 2022, vol. 1(no. 2), 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIsaac, C.; Nguyen, M.; Uy, A.; Kong, T.; Hedayatipour, A. ‘A Programmable Gain Calibration Method to Mitigate Skin Tone Bias in PPG Sensors’. Biosensors (Basel) 2025, vol. 15(no. 7), 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Monk, ‘The Monk Skin Tone Scale’. 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).