Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

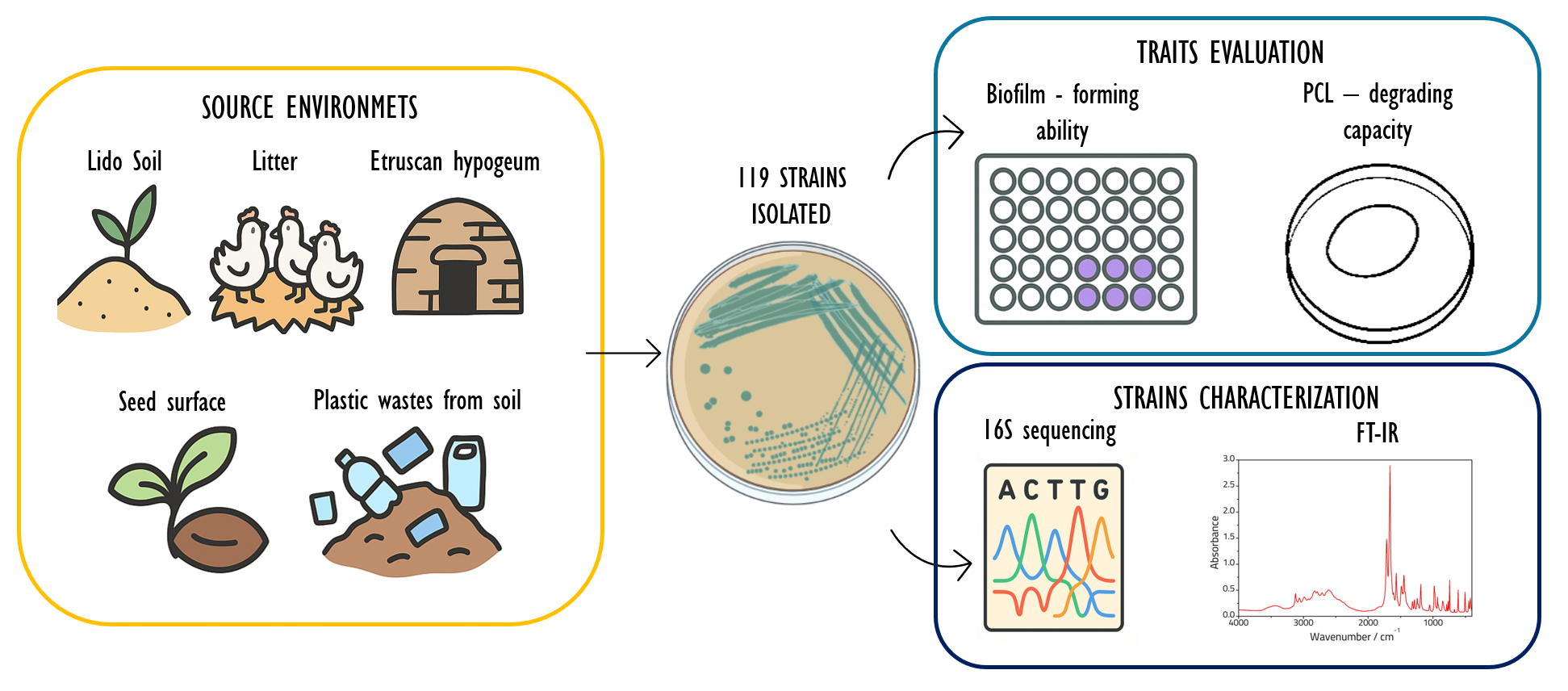

2.1. Bacterial Isolation and Cultivation

2.2. Biofilm Quantification by Crystal Violet Assay

2.3. Bacterial DNA Extraction

2.4. 16S rRNA Amplification and Sanger Sequencing

2.5. FT-IR Spectroscopy

2.6. Polycaprolactone (PCL) Plate Clearing Assays

2.7. Statistical and Multivariate Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Assessing the Relationship Between Biofilm – Forming Phenotype and the Isolation Environment

3.2. Assessing the Relationship Between Biofilm – Forming Phenotype and Taxonomy

3.3. Search for Descriptors Significantly Correlated with Biofilm – Forming Phenotype

3.4. Distribution of Biofilm – Forming Phenotype Within the Phylogenetic Tree

3.5. Relationship Between Biofilm – Forming Phenotype and the Polycaprolactone Degradation Capacity

3.6. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCL | Polycaprolactone |

| PLSR | Partial Least Squares Regression |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinates Analysis |

References

- Finlay, B.J.; Maberly, S.C.; Cooper, J.I. Microbial diversity and ecosystem function. Oikos 1997, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivedita, S.; Behera, S.S.; Behera, P.K.; Parwez, Z.; Giri, S.; Parida, S.R.; Ray, L. Microbial Ecology to Manage Processes in Environmental Biotechnology; Springer: Microbial Niche Nexus Sustaining Environmental Biological Wastewater and Water-Energy-Environment Nexus, 2025; pp. 665–704. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Schwarz, J.R. Seasonal shifts in population structure of Vibrio vulnificus in an estuarine environment as revealed by partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2003, 45, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortíz-Castro, R.; Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Macías-Rodríguez, L.; López-Bucio, J. The role of microbial signals in plant growth and development. Plant Signal. Behav. 2009, 4, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, R.G.; Young, R.A. Insights into host responses against pathogens from transcriptional profiling. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, E.L. Microorganisms and their roles in fundamental biogeochemical cycles. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011, 22, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinane, D.F.; Preshaw, P.M.; Loos, B.G. Working Group 2 of Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology. Host-response: understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms of host-microbial interactions - Consensus of the Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Liu, H. Modification of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities: A Possible Mechanism of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Enhancing Plant Growth and Fitness. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 920813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.H.; Braverman, K.; Osorio, N. Evidence for mutualism between a plant growing in a phosphate-limited desert environment and a mineral phosphate solubilizing (MPS) rhizobacterium. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 1999, 30(4), 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Tang, L.; A Fenton, K.; Song, X. Exploring and evaluating microbiome resilience in the gut. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2025, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmes, P.; Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Ostaszewski, M.; Aho, V.T.; Novikova, P.V.; Laczny, C.C.; Schneider, J.G. The gut microbiome molecular complex in human health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhu, D.; Rillig, M.C.; Yang, Y.; Chu, H.; Chen, Q.; Penuelas, J.; Cui, H.; Gillings, M. Ecosystem Microbiome Science. mLife 2023, 2, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, T.C.G.; Wigley, M.; Colomina, B.; Bohannan, B.; Meggers, F.; Amato, K.R.; Azad, M.B.; Blaser, M.J.; Brown, K.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; et al. The potential importance of the built-environment microbiome and its impact on human health. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvé, S.; Desrosiers, M. A review of what is an emerging contaminant. Chemistry Central Journal 2014, 8(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M.; Esrafili, A.; Gholami, M.; Jafari, A.J.; Kalantary, R.R.; Farzadkia, M.; Kermani, M.; Sobhi, H.R. Contaminants of emerging concern: a review of new approach in AOP technologies. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 414–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Chen, T.; Adyari, B.; Kiki, C.; Sun, Q.; Yu, C.-P. Responses of microbial community to the selection pressures of low-concentration contaminants of emerging concern in activated sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 490, 137880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.A.; Malhotra, H.; Papade, S.E.; Dhamale, T.; Ingale, O.P.; Kasarlawar, S.T.; Phale, P.S. Microbial degradation of contaminants of emerging concern: metabolic, genetic and omics insights for enhanced bioremediation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1470522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, I.B. The overlooked interaction of emerging contaminants and microbial communities: a threat to ecosystems and public health. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.S.M.; Asair, A.A.; Fetyan, N.A.H.; Elnagdy, S.M. Complete Biodegradation of Diclofenac by New Bacterial Strains: Postulated Pathways and Degrading Enzymes. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Ma, Y.; Chang, H.; Li, B.; Ding, M.; Yuan, Y. Evaluation of PET Degradation Using Artificial Microbial Consortia. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 778828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, C.; Tezel, U. Biotransformation of Acetaminophen by intact cells and crude enzymes of bacteria: A comparative study and modelling. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 703, 134990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corte, L.; Pierantoni, D.C.; Tascini, C.; Roscini, L.; Cardinali, G. Biofilm Specific Activity: A Measure to Quantify Microbial Biofilm. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkiewicz, J.P.; Kellogg, C.A. Cross-Kingdom Amplification Using Bacteria -Specific Primers: Complications for Studies of Coral Microbial Ecology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 7828–7831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscini, L.; Corte, L.; Antonielli, L.; Rellini, P.; Fatichenti, F.; Cardinali, G. Influence of cell geometry and number of replicas in the reproducibility of whole cell FTIR analysis. Anal. 2010, 135, 2099–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helm, D.; Labischinski, H.; Schallehn, G.; Naumann, D. Classification and identification of bacteria by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Microbiology 1991, 137, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, E.L.; Rincón, A.F.C.; Jackson, S.A.; Dobson, A.D.W. In silico Screening and Heterologous Expression of a Polyethylene Terephthalate Hydrolase (PETase)-Like Enzyme (SM14est) With Polycaprolactone (PCL)-Degrading Activity, From the Marine Sponge-Derived Strain Streptomyces sp. SM14. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampolli, J.; Vezzini, D.; Brocca, S.; Di Gennaro, P. Insights into the biodegradation of polycaprolactone through genomic analysis of two plastic-degrading Rhodococcus bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1284956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molitor, R.; Bollinger, A.; Kubicki, S.; Loeschcke, A.; Jaeger, K.-E.; Thies, S. Agar plate-based screening methods for the identification of polyester hydrolysis by Pseudomonas species. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 13, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierantoni, D.C.; Conti, A.; Ruspi, C.; Donati, L.; Favaro, L.; Corte, L.; Cardinali, G. Effect of olive oil wastewaters polyphenols on chicken faecal and litter microbiota towards safe and effective waste valorisation. Heliyon 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hosni, A.S.; Pittman, J.K.; Robson, G.D. Microbial degradation of four biodegradable polymers in soil and compost demonstrating polycaprolactone as an ideal compostable plastic. Waste Manag. 2019, 97, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetsigian, K. Diverse modes of eco-evolutionary dynamics in communities of antibiotic-producing microorganisms. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, B.; Lanfranconi, M.P.; Piña-Villalonga, J.M.; Bosch, R. Anthropogenic perturbations in marine microbial communities. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyyssölä, A.; Pihlajaniemi, V.; Järvinen, R.; Mikander, S.; Kontkanen, H.; Kruus, K.; Kallio, H.; Buchert, J. Screening of microbes for novel acidic cutinases and cloning and expression of an acidic cutinase from Aspergillus niger CBS 513.88. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2013, 52, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roscini, L.; Conti, A.; Pierantoni, D.C.; Robert, V.; Corte, L.; Cardinali, G. Do Metabolomics and Taxonomic Barcode Markers Tell the Same Story about the Evolution of Saccharomyces sensu stricto Complex in Fermentative Environments? Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.B. Antibiotic-Induced Biofilm Formation. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2011, 34, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, S.; Anderson, A.; Macchiarelli, G.; Hellwig, E.; Cieplik, F.; Vach, K.; Al-Ahmad, A. Subinhibitory Antibiotic Concentrations Enhance Biofilm Formation of Clinical Enterococcus faecalis Isolates. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penesyan, A.; Nagy, S.S.; Kjelleberg, S.; Gillings, M.R.; Paulsen, I.T. Rapid microevolution of biofilm cells in response to antibiotics. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2019, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shree, P.; Singh, C.K.; Sodhi, K.K.; Surya, J.N.; Singh, D.K. Biofilms: Understanding the structure and contribution towards bacterial resistance in antibiotics. Med. Microecol. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; de Koster, A.; Koenders, B.B.; Jonker, M.; Brul, S.; ter Kuile, B.H. De novo acquisition of antibiotic resistance in six species of bacteria. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0178524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, J.; Khyriem, A.B.; Banik, A.; Lyngdoh, W.V.; Choudhury, B.; Bhattacharyya, P. Association of biofilm production with multidrug resistance among clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa from intensive care unit. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 17, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, P.; Mohajeri, P.; Mashouf, R.Y.; Karami, M.; Yaghoobi, M.H.; Dastan, D.; Alikhani, M.Y. Molecular characterization of clinical and environmental Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated in a burn center. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1731–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, S.G.; Uhlig, K.; Hale, R.C.; Song, B. Microplastic biofilms as potential hotspots for plastic biodegradation and nitrogen cycling: a metagenomic perspective. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2025, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, I. Role of microbiome and biofilm in environmental plastic degradation. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debroy, A.; George, N.; Mukherjee, G. Role of biofilms in the degradation of microplastics in aquatic environments. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 97, 3271–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierantoni, D.C.; Corte, L.; Casadevall, A.; Robert, V.; Cardinali, G.; Tascini, C. How does temperature trigger biofilm adhesion and growth in Candida albicans and two non-Candida albicans Candida species? Mycoses 2021, 64, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isolation environment | Stressors |

| Lido soil | High salinity |

| Seed surface | Oligotrophy, water-limited stress |

| Hypogean tomb | Oligotrophy, high relative humidity (95–100%) |

| Intensive poultry farming | prophylactic applications of antibiotics |

| Plastic contaminated soil | PLA, PVC and Mater B polymers |

| Isolation environment | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

| Lido soil | 0% | 50% | 20% | 30% |

| Seed surface | 10% | 80% | 10% | 0% |

| Hypogeal tomb | 0% | 17% | 33% | 50% |

| Intensive poultry farming | 54% | 26% | 18% | 2% |

| Plastic contaminated soil (MaterB) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Plastic contaminated soil (PLA) | 9% | 5% | 41% | 45% |

| Plastic contaminated soil (PVC) | 0% | 0% | 31% | 69% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).