Plastics have penetrated aquatic ecosystems and become a serious environmental problem. They originate from many sources, such as bottles, packaging, cosmetics. Each year, more than 1 million metric tons of plastic are discharged into oceans, rivers, and lakes (Meijer et al., 2021). Over time, larger plastics break down into microplastics (1 µm–5 mm) and nanoplastics (<1 µm), which pose a persistent threat to biodiversity, ecosystems, and human health (Gillibert et al., 2019). Their small size makes them easy for aquatic organisms to ingest, leading to toxic effects and the potential bioaccumulation of harmful chemicals (Leterme et al., 2023).

The presence of pathogens and ARGs in aquatic systems is a major environmental and public health concern. Pathogenic bacteria and viruses can cause disease in humans, animals, and plants through exposure routes such as drinking water, recreation, and contaminated seafood (Zhang et al., 2025). Meanwhile, ARGs are genetic elements that enable bacteria to resist antibiotics. They can be present in water as a result of improper use of antibiotics in human medicine and agriculture. Due to horizontal gene transfer, ARGs can spread rapidly within microbial communities, resulting in the evolution and proliferation of multiple antibiotic-resistant strains and organisms (Seymour and McLellan, 2025).

Plastics have emerged as an important vector for transporting and spreading microbial contaminants in aquatic environments (Siddique et al., 2025). Their hydrophobic, rough, and electrostatically charged surfaces create favorable conditions for microorganisms, including pathogens and ARGs, to attach and accumulate. These microbes often form biofilms on plastic debris, which shield them from adverse conditions and enhance their persistence in aquatic systems (He et al., 2022).

Plastics can also move these contaminants over long distances in aquatic environments. As larger items disintegrate into microplastics and nanoplastics, they disperse attached microorganisms and genetic material across broader areas, raising risks even for pristine or remote waters (Queiroga et al., 2025). Therefore, it is critical to understand the role of plastics in mediating pathogens and ARGs in water to determine health risks and implement effective methods to reduce plastic-mediated microbial pollution.

The main goal of this review is to examine the role of plastics as vectors for microbial pathogens and ARGs in aquatic ecosystems. The specific aims are to: (1) review how microbial contaminants attach to, move on, and spread via plastic surfaces; (2) assess current methods for detecting, quantifying, and characterizing pathogens and ARGs associated with plastic pollution; and (3) identify mitigation strategies and policy options to address plastic-related microbial hazards.

1. Overview of Plastic Pollution in Aquatic Systems

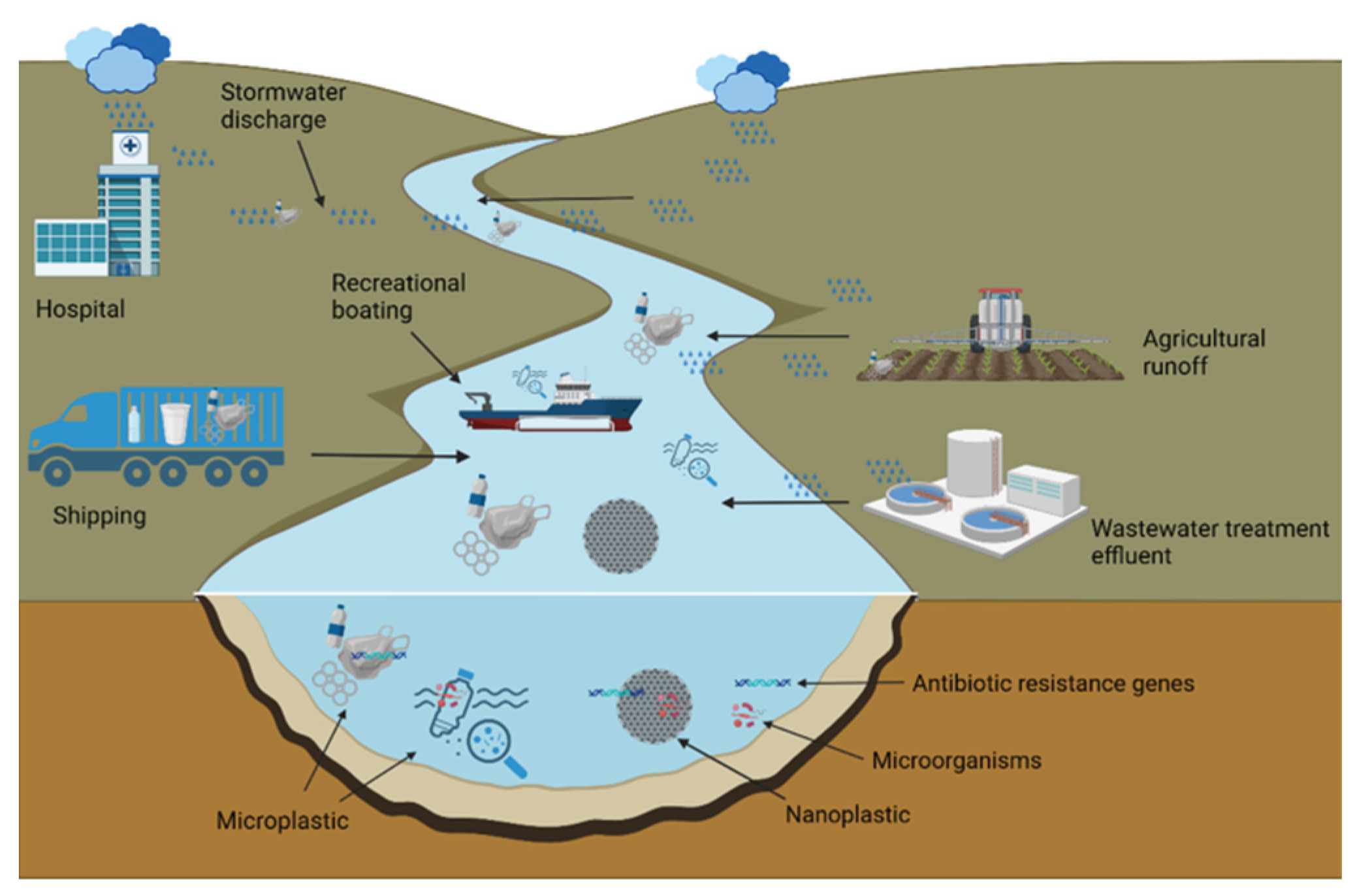

Plastic pollution in aquatic waters comes from many sources, such as industrial and household activities, poor waste management, and the fragmentation of larger plastic items (Lee et al., 2024). Primary plastics are tiny plastics manufactured for specific uses, for example, microbeads in cosmetics, industrial pellets, or synthetic fibers. Secondary plastics come from the degradation of large plastic products like plastic bags, bottles, and packaging materials. Plastics can enter aquatic ecosystems through improper disposal, atmospheric deposition, direct discharge from industrial facilities, or runoff from urban and agricultural activities.

Microplastics and nanoplastics have gained much public attention due to their small size, prevalence, and potential adverse effects. Microplastics arise when larger plastic products break down or when microbeads are directly released. They are readily ingested by fish, marine mammals, and other aquatic organisms, leading to physical blockage, toxicity, and trophic transfer, ultimately posing risks to human health (Mamun et al., 2023). Nanoplastics can form as microplastics further degrade or be released from industrial processes and products. Because of their very small size, nanoplastics can cross biological membranes and damage cells and tissues in aquatic organisms (Liang et al., 2024).

Microplastics and nanoplastics spread through waters via physical, biological, and chemical pathways. Physical transport by currents and wind disperses particles far from their sources, even globally (Belioka and Achilias, 2024). Biological processes contribute through ingestion by organisms and biofouling, which is the attachment of microorganisms to plastic surfaces (Yan et al., 2024). Chemical interactions include the adsorption of pollutants onto plastics, turning them into carriers of toxic chemicals that can be taken up by aquatic life or released back into the water (Adamu et al., 2024).

The fate and transport of plastics in water depend on particle properties, environmental conditions, and human activities. Buoyant microplastics can travel long distances at the surface, aiding wide dispersion (Kim and Kim, 2024). Size and shape govern their movement, suspension, and settling. In particular, larger microplastics tend to deposit in sediments, while smaller nanoplastics remain suspended or are consumed and enter food chains. Polymer composition also matters. Hydrophobic plastics can adsorb organic contaminants, which may change their transport and settling. Environmental factors, such as currents, turbulence, storm events, UV radiation, and

hydrolysis, can degrade and transport plastics, as well as release additives (Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2024). Human inputs from

Figure 1.

Different sources of microplastics and nanoplastics in aquatic environments wastewater, agriculture, and maritime activities also introduce and redistribute plastics (Belioka and Achilias, 2024).

Figure 1.

Different sources of microplastics and nanoplastics in aquatic environments wastewater, agriculture, and maritime activities also introduce and redistribute plastics (Belioka and Achilias, 2024).

In marine systems, plastics are carried globally by ocean currents and wind-driven surface flow, with floating debris accumulating in subtropical gyres. Buoyant polymers such as polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) remain near the surface, whereas denser polymers like polyvinyl chloride (PVC) sink and pollute deep-sea sediments (Okoffo et al., 2024). In freshwater, major sources include wastewater effluent, stormwater runoff, and riverine inputs, leading to accumulation in lakes, rivers, and reservoirs (Jin et al., 2025). Hydrology, sediment interactions, and biotic activity shape how plastic particles disperse and settle.

Physical, chemical, and biological processes influence the degradation and persistence of plastics. UV radiation and mechanical abrasion from waves or sediments fragment larger plastics into micro- and nanoplastics, increasing surface area and interactions with organisms (Arif et al., 2024). Chemical weathering, for instance, photooxidation and hydrolysis, alters polymer structure, affecting buoyancy and breakdown rates (Tian et al., 2024). Biological processes, including biofouling and biodegradation, can increase density and promote sinking (biofouling) or lead to partial/complete breakdown and mineralization (biodegradation) (Chen et al., 2024). Outcomes vary with environmental conditions, polymer type, and additives. Nevertheless, plastic persistence remains a major concern due to the potential toxicity of by-products for ecosystems and human health.

The ecological impacts of plastic pollution in water are broad. At the organism level, plastic ingestion causes blockages, reduced feeding, and impaired reproduction (Bhat et al., 2024). Plastics can also transport invasive species and pathogens, altering community composition and ecosystem function. At larger scales, accumulation modifies habitats and disrupts processes such as nutrient cycling and light penetration (Nava et al., 2024). In addition, plastics can carry toxic chemicals that transfer to organisms and ecosystems, posing serious risks to marine life and biodiversity (Okoye et al., 2022). These threats underscore the need for coordinated global action to reduce plastic pollution.

2. Plastics as Vectors for Pathogens

In recent years, plastics in aquatic environments have been increasingly recognized as habitats and carriers for diverse microbial pathogens. The unique physicochemical characteristics of plastics, such as hydrophobicity, surface roughness, and additives, promote the adhesion of pathogens like bacteria and viruses. This can lead to the generation of stable biofilms, which will improve the initial adhesion, survival, and resilience of pathogens under environmental stresses and unfavorable conditions, for example, UV exposure, salinity changes, and predatory microorganisms (Fazeli-Nasab et al., 2022). The biofilm matrix also acts as a nutrient reservoir, supporting metabolic interactions within the microbial community and enabling pathogen proliferation. This biofilm-mediated growth is especially concerning because it can facilitate horizontal gene transfer and the spread of pathogens in water (Roy et al., 2022). As a result, pathogens can be carried over long distances and cause disease in aquatic environments, with significant implications for ecosystems and human health. For example, E. coli has been detected on plastics floating in marine and freshwater systems, posing risks to aquatic organisms and human health (Junaid et al., 2022).

Pathogens adhere to plastic surfaces through physical adhesion, chemical interactions, biofilm formation, and other microbial activities. Surface properties, such as roughness, hydrophobicity, and charge, are key determinants of attachment. Initial adhesion can be described by Derjaguin, Landau, Verwey, and Overbeek (DLVO) theory, whereas van der Waals forces (attractive) and electrostatic double-layer forces (repulsive) govern the force balance between bacteria and plastics (Ouyang et al., 2023; Vu et al., 2015). Rougher surfaces provide more sites and area for attachment, strengthening both initial adhesion and community stability. The inherent hydrophobicity of common plastics like polyethylene and polypropylene favors contact with hydrophobic cell envelopes, promoting non-specific hydrophobic interactions. Plastics also adsorb organic compounds from surrounding water, which can serve as nutrients and stimulate microbial growth and colonization. In addition, functional groups on plastic surfaces can interact with microbial cell surfaces and influence adhesion (Liu et al., 2023). Additives used in plastic production (e.g., plasticizers, stabilizers, antioxidants) may leach into the water and become carbon sources or cofactors for microbes, further supporting development and proliferation on plastic surfaces (Luo et al., 2022).

Once attached, pathogens often form biofilms, which are complex communities embedded in an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. Under nutrient-limited conditions, biomass growth in biofilms can be described by a Monod equation (Yin et al., 2022; Shin et al., 2021):

Where µ is the specific growth rate, day-1

µmax is the maximum growth rate, day-1

S is the nutrient or substrate concentration, mgSL-1

Ks is the half-saturation constant, mgSL-1

The EPS matrix protects pathogens from UV radiation, predation, and antimicrobial agents while enhancing nutrient capture and retention, thereby promoting microbial growth in aquatic systems. Biofilms also serve as hotspots for genetic exchange, such as horizontal gene transfer (HGT), which carries resistance genes between pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains (Siddique et al., 2025). Consequently, biofilms support the persistence and proliferation of pathogenic communities on plastic debris, enabling them to survive in unfavorable conditions and raising concerns about their spread on plastic surfaces.

Figure 2.

Microbial and biofilm colonization of floating plastics in surface water.

Figure 2.

Microbial and biofilm colonization of floating plastics in surface water.

Plastics ingested by marine and freshwater organisms can carry bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens on their surfaces. Invertebrates and mammals may take in substantial amounts of contaminated plastic during normal feeding, increasing the risk of infection (Junaid et al., 2022). In addition, the bioaccumulation and biomagnification of plastic-mediated pathogens in the food web can contaminate small prey and large predators, harming biodiversity and ecosystem stability. Pathogens carried on plastics can directly cause disease, such as gastrointestinal infections, in aquatic organisms and humans through exposure to contaminated water, seafood, or recreational activities (Hemdan et al., 2021). The presence of ARGs on these plastics can worsen the issue by spreading hard-to-treat antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB), increasing the risk of severe outcomes.

Plastic-mediated pathogens can influence human health through the utilization of contaminated water and seafood. Plastics can transport pathogens that cause waterborne diseases, for example, cholera and botulism, particularly in places with heavy plastic pollution and limited water treatment (Ormsby et al., 2024). Pathogen-contaminated microplastics can also enter the human food chain through seafood, presenting direct risks to consumers. Over the long term, these exposures can drive up healthcare costs from waterborne and foodborne illnesses, contribute to the emergence of new diseases, and create lasting burdens on community health and economic stability, especially in regions dependent on aquaculture and tourism.

3. Plastics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes

The prevalence of ARGs on plastics in aquatic ecosystems is a growing concern because of the duty of plastic in spreading ARGs across microbial communities. Plastics offer a solid and stable surface for biofilm formation and developing diverse microbial species. Within these biofilms, ARGs can be exchanged between pathogens through the horizontal gene transfer (HGT) process, facilitated by the stable and nutrient-rich microhabitats (Syranidou and Kalogerakis, 2022). In addition, the rough and hydrophobic characteristics of plastic surfaces improve the adhesion of ARB, thus increasing the tendency of HGT. Sub-lethal antibiotic concentrations in water create selective pressure, further facilitating the accumulation and spread of ARGs between microbes on plastic surfaces (Shi et al., 2022). As a result, the persistence and wide distribution of plastics in aquatic systems enable them to carry ARGs both locally and over long distances, creating significant challenges for global public health and environmental management.

Plastics in water also promote horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and the spread of ARGs across microbial communities via transformation, transduction, and conjugation (Shi et al., 2024). In transformation, bacteria take up free DNA from their surroundings, plastic surfaces can concentrate extracellular DNA (eDNA) from lysed cells, and this eDNA may carry ARGs that become integrated into receptive genomes. In transduction, bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) move ARGs between hosts, with plastics providing stable surfaces that can support phage attachment and infection cycles. Conjugation implies the direct transfer of plasmids carrying ARGs between bacterial cells through pilus formation, which is considerably effective within the dense microbial communities on plastic surfaces. These HGT mechanisms within a biofilm on plastic surfaces greatly increase the persistence and spread of ARGs in the environment. As a result, plastic-polluted waters become reservoirs for ARGs, making it harder to control the spread of resistance through conventional wastewater treatment and environmental management (Shi et al., 2022).

Biofilm formation on plastic surfaces further facilitates antibiotic resistance by providing a protective microenvironment that supports bacterial survival and gene exchange (Zheng et al., 2023). The EPS matrix in biofilms shields bacteria from stressors like UV radiation, desiccation, and antimicrobial agents, increasing the persistence of resistant populations. Antibiotics and other selective pressures within biofilms further favor the selection and growth of resistant strains. The biofilm’s three-dimensional structure establishes nutrient gradients and fosters metabolic cooperation, which supports genetic diversity and the retention of ARGs (Hoiby et al., 2010). Biofilms can also act as reservoirs by capturing and concentrating ARGs released into surrounding waters (Jing et al., 2023). Collectively, the physical stability of plastics and the dynamic behavior of microbial communities highlight the central role of plastic-associated biofilms in the spread of ARGs.

The presence of plastics in aquatic environments and their role in spreading ARGs present major public health challenges. The transmission of ARGs to pathogenic bacteria can result in multi-drug resistant (MDR) infections, which are more challenging to treat and manage. Humans can be exposed through multiple routes, such as polluted water, contaminated seafood, and irrigation practices (Poque et al., 2015). Despite mitigation efforts, environmental reservoirs can reintroduce resistance into clinical settings and complicate antibiotic stewardship. The persistent and widespread presence of plastic pollution suggests that associated risks will rise over time, underscoring the need for integrated strategies (Pruden et al., 2013). Key approaches include improving wastewater treatment technologies, adopting policies that reduce plastic waste, and strengthening monitoring and surveillance programs to track the spread of ARGs in the environment.

4. Common Molecular Biology Techniques for Detecting Pathogens and Args on Plastics

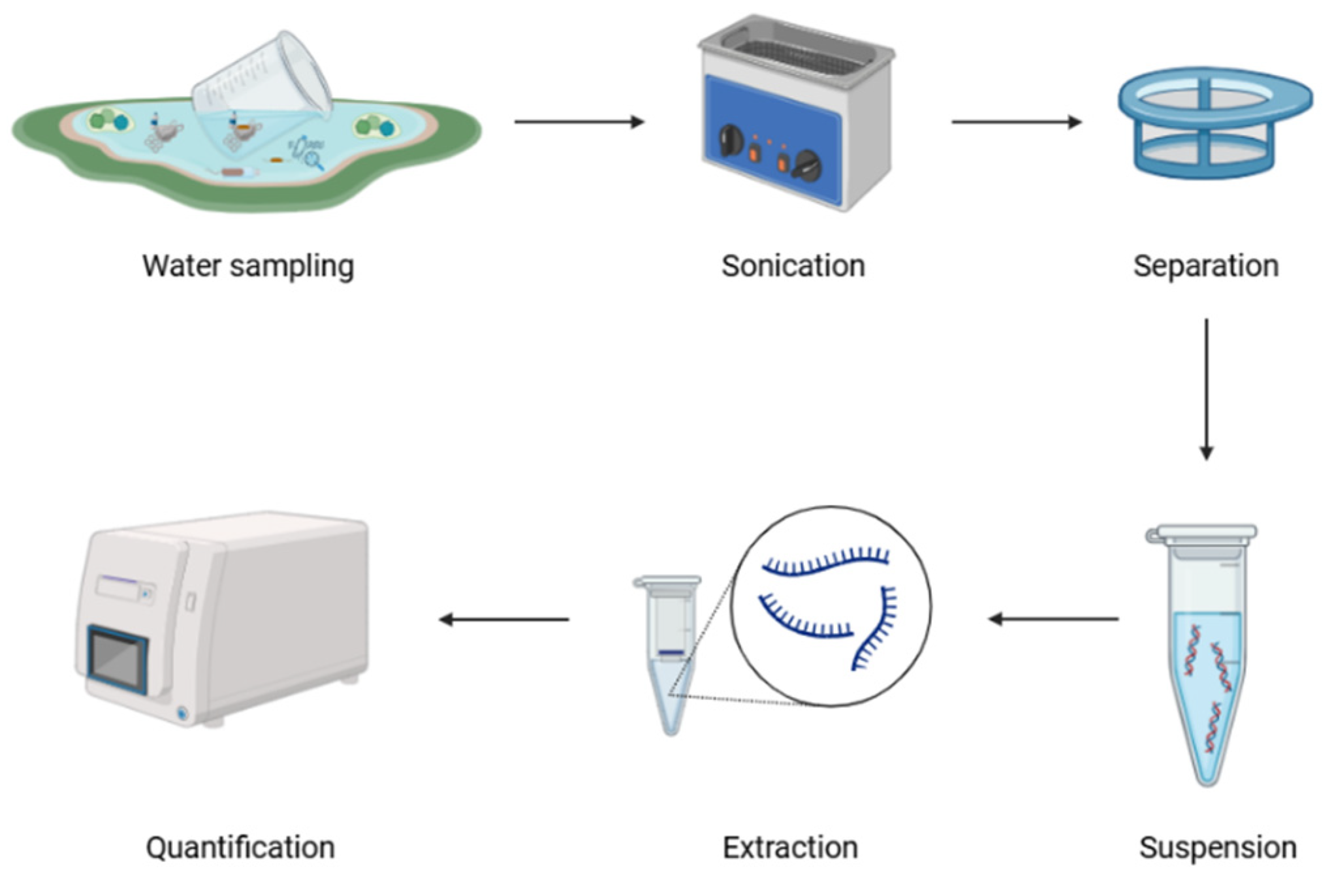

The detection and quantification of microbial communities and ARGs on plastic surfaces in aquatic environments is critical for understanding potential risks and developing effective treatments. Traditional culture-based methods are time-consuming, costly, impractical for many pathogens, and often miss much of the microbial diversity, especially on plastic surfaces (Ahmad et al., 2024). In contrast, molecular methods overcome these limitations by directly targeting nucleic acids, allowing the identification of both culturable and non-culturable organisms (Zhang et al., 2021).

Recent advanced molecular biology techniques have offered powerful tools to identify and characterize the abundance, composition, and functional potential of microbial pathogens and ARGs on plastics. Among these techniques, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) remain core methods for detecting and quantifying specific genes (Vu et al., 2024; Yaniv et al., 2021). Metagenomics, which direct DNA sequencing from environmental samples, offers a comprehensive view of microbial diversity and functional potential (Shu and Huang, 2022). Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-based methods introduce highly specific, sensitive, and rapid tools for detecting ARGs, improving our ability to monitor resistance spread (Mao et al., 2025). Understanding each technique’s strengths and limitations is important for practical utilization in environmental sampling and analysis.

5.1. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

PCR is a fundamental molecular technique for detecting microbial communities and ARGs on plastic surfaces. It uses short DNA primers designed to bind target sequences in DNA extracted from samples. By amplifying these targets, PCR can identify microorganisms or ARGs even at very low abundance (Luby et al., 2016). Amplification proceeds through repeated cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension, producing exponential replication of the target region. Because of its high detection sensitivity and target specificity, PCR is practical for detecting sparse microorganisms and ARGs in complex environmental samples.

Similarly, qPCR (or real-time PCR) can precisely measure low-abundance microorganisms and ARGs in complex environmental samples. This approach incorporates fluorescent dyes or probes into the PCR mixture and measures fluorescence in real time, with signal intensity rising in proportion to the DNA amplified each cycle. qPCR enables reliable quantification of specific genes, especially ARGs, in water samples (Milobedzka et al., 2022). It can distinguish between low and high amounts of gene expression, providing a comprehensive understanding of microbial load and resistance gene distribution on plastics. Hence, qPCR is valuable for assessing the effectiveness of pollution control methods and evaluating the risks caused by ARGs in aquatic systems.

One key advantage of PCR and qPCR is their high sensitivity and specificity. PCR can amplify small amounts of DNA, enabling the detection of limited microorganisms and ARGs in environmental samples. qPCR extends this capability by quantifying target DNA, enabling accurate estimates of microbial and ARG prevalence (Ishii, 2020). It also provides real-time results and removes the need for post-PCR steps like gel electrophoresis, streamlining the workflow and reducing contamination risk (Ahmed et al., 2022). The quantitative feature of qPCR is particularly useful for environmental monitoring, as it enables the assessment of changes in microbial communities and ARG concentration over time or under different conditions. Moreover, the widespread availability of PCR and qPCR instruments and reagents makes these approaches accessible to many laboratories, facilitating their use in various research applications.

PCR and qPCR also have constraints. Because they require specific primers, the target DNA sequences must be known in advance (Vu et al., 2024; Smith and Osborn, 2009). This limits detection of unknown or uncharacterized microorganisms and ARGs and can lead to underestimations in communities with many uncatalogued taxa. Inhibitors common in environmental samples, such as humic acids, heavy metals, and organic matter, can also suppress amplification, causing false negatives or lowering sensitivity (Ahmed et al., 2022; Hata et al., 2015).

Although improved extraction and cleanup methods can reduce inhibition, additional time, complexity, and cost will be incurred. As a result, PCR and qPCR are powerful for targeted analyses but may not provide a comprehensive view of microbial communities or ARG prevalence in environmental samples. Metagenomic approaches can complement these techniques by offering a broader perspective on microbial diversity and ARG abundance.

Figure 3.

Protocol to use PCR and qPCR for detecting pathogens on plastic surfaces.

Figure 3.

Protocol to use PCR and qPCR for detecting pathogens on plastic surfaces.

4.2. Metagenomics

Metagenomics is a technique to determine and quantify microbial communities and ARGs by sequencing genetic material from plastics in aquatic systems. This method identifies a wide range of microorganisms and resistance genes without knowing their sequences. It removes the need to culture organisms and allows detection of multiple pathogens, especially those that are difficult to grow in the lab. The workflow typically involves extracting DNA from plastic samples, fragmenting it, and sequencing with high-throughput platforms such as Illumina or Oxford Nanopore (Davidov et al., 2020). Bioinformatics tools then assemble and annotate the reads to reconstruct genomes, identify taxa, and detect functional genes like ARGs. This approach produces extensive datasets that reveal the presence, relative abundance, and genetic context of resistance genes in the environment (Port et al., 2014). It also supports comparisons of microbial community diversity across samples, helping to clarify interactions within plastic-associated biofilms and their role in ARG dissemination.

A key strength of metagenomics is its comprehensive view of microbial diversity and functional potential without relying on culture-based methods (Zhang et al., 2021). This is especially useful when target organisms are not readily cultured or resistance genes must be identified within complex communities. Metagenomics can uncover novel ARGs and previously unrecognized microorganisms, expanding understanding of aquatic microbial ecology. It can also detect and characterize the genetic context of ARGs on plastic surfaces during horizontal gene transfer (Zhu et al., 2025) and track changes in community composition and ARG prevalence over time in response to environmental pressures and human activities.

However, metagenomics has practical challenges. Sequencing and bioinformatics can be expensive and technically demanding, which limits wider application (Zhang et al., 2021). The large volumes of data require substantial computing resources and expertise for analysis and interpretation. Low DNA yields and sample contamination can hinder results and introduce bias. In addition, metagenomics typically provides relative (not absolute) abundance data, making it difficult to quantify specific microorganisms or ARGs directly (Ferreira et al., 2023). Absolute quantification usually requires complementary techniques such as qPCR, which can be more costly and labor-extensive. Assembling metagenomic data is also able to be challenging, especially for highly diverse and complex communities, potentially resulting in incomplete or fragmented genomes that decrease the accuracy of identifying and characterizing microbial taxa and their associated ARGs.

4.3. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)

CRISPR-based (CRISPR-Cas) methods provide precise, efficient, and versatile tools for studying microbial diversity and ARGs on plastics. The CRISPR-Cas system has two main parts: a CRISPR array and Cas proteins (Mao et al., 2025). The CRISPR array contains repetitive DNA sequences interspaced with unique spacers from foreign DNA, while Cas proteins (e.g., Cas9) act as molecular scissors to cut target DNA. The CRISPR workflow includes spacer acquisition from foreign DNA, CRISPR RNA (crRNA) processing, assembly with a trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) and a Cas protein, and cleavage of DNA sequences that match the crRNA spacer (Bhatia and Yadav, 2023). For environmental applications, synthetic guide RNAs (gRNAs) are designed to target specific microbial genes or ARGs on plastics. Cas proteins are then delivered into a suitable host or applied directly to samples, where they cut the target DNA (Wang et al., 2022). The resulting fragments can be detected by qPCR or next-generation sequencing (NGS), enabling accurate identification and quantification of microbial communities and ARGs. This approach offers clear advantages for environmental monitoring and ARG management.

A key benefit of CRISPR-based methods is their high specificity and accuracy. Well-designed gRNAs can target complementary DNA sequences with precision, allowing selective detection of particular microorganisms and ARGs and reducing false positives for more reliable results (Chen et al., 2025). Moreover, these methods effectively cleave the target DNA of specific microbial pathogens and ARGs, even infrequent targets in complex environmental samples and might be missed by other methods.

Another strength of CRISPR-based methods is their adaptability and ease of use. gRNAs can be readily modified to target many different genes, giving researchers flexibility to study microbial communities and ARGs across diverse environmental contexts (Gelsinger et al., 2024). This is especially valuable in environmental engineering and science, where microbial composition varies widely. Importantly, these methods do not require prior knowledge of complete genomes, enabling the detection of new microorganisms and ARGs, which is critical for comprehensive monitoring and understanding the spread of resistance in natural systems.

Despite these advantages, CRISPR-based approaches have limitations. Off-target effects remain a central concern that even highly specific gRNAs can occasionally bind partially matching sequences and trigger unintended cleavage (Tao et al., 2023). Sample inhibitors such as humic acids or heavy metals can also interfere with enzyme binding and cutting, complicating interpretation and reducing accuracy (Gazu et al., 2025). To improve reliability and comparability across studies, standardized protocols for sampling, preparation, and analysis are essential. Developing portable CRISPR diagnostics would further enhance in situ monitoring by enabling real-time detection of microbial communities and ARGs in environmental samples.

A further challenge is the need for advanced laboratory infrastructure and specialized expertise. CRISPR workflows often require cutting-edge molecular techniques and sequencing platforms that may not be available in all settings. The resulting datasets can be complex and demand substantial bioinformatics skills (Bock et al., 2022). These constraints point to the importance of collaborative efforts and user-friendly analytical tools to broaden access. Table 2 compares various molecular biology techniques used to identify pathogens and ARGs in plastics.

5. Impacts on Aquatic Ecosystems and Human Health

Plastics contaminated with pathogens and ARGs induce a significant threat to aquatic ecosystems. These contaminants, conveyed by plastics, are able to propagate antibiotic resistance and interrupt the ecological balance of water bodies. One major ecological impact of pathogen- and ARG-contaminated plastics is the disruption of microbial consortia. Plastics provide a unique substrate for biofilm development, allowing microbial communities and ARG carriers to survive and expand. Yang et al. (2019) showed that marine microplastics are colonized by complex biofilms that facilitate HGT and the spread of ARGs among bacterial species. Similarly, Sathicq et al. (2021) reported higher abundances of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) on plastic surfaces than in surrounding water, indicating that plastics can selectively enrich resistant strains and raise overall ARG levels in the environment. The proliferation of resistant bacteria can disrupt natural microbial communities, which will reduce biodiversity and alter ecosystem functions.

The accumulation of microplastics in sediments can degrade habitat quality and harm benthic organisms that are vital for nutrient cycling and sediment stability. Corinaldesi et al. (2022) found that microplastics in sediments reduced the abundance and diversity of meiofauna, key contributors to sediment health. Filter-feeding organisms such as mussels and oysters are especially vulnerable to ingesting microplastics. Zhang et al. (2019) showed that mussels, oysters, and clams can ingest microplastics along with pathogens and ARGs, leading to bioaccumulation of contaminants. This ingestion impairs feeding, growth, and reproduction, affecting populations and the broader food web. Predators, including fish and birds, are then exposed as they consume contaminated prey, raising risks through bioaccumulation and potential biomagnification. In parallel, ARGs in the water column can foster antibiotic resistance in native bacterial populations. Yashir et al. (2025) demonstrated that ARGs associated with microplastics can transfer to indigenous bacteria, further spreading resistance and disrupting processes such as organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling.

Plastics contaminated with pathogens and ARGs in water pose direct and indirect risks to human health. A major pathway is the consumption of contaminated seafood, where filter feeders accumulate pathogens and ARGs from water and sediment, and these contaminants can move up the food chain. Humans who eat contaminated seafood may be exposed to harmful bacteria and resistance genes, leading to the risk of foodborne illness and antibiotic-resistant infections (Zhang et al., 2019).

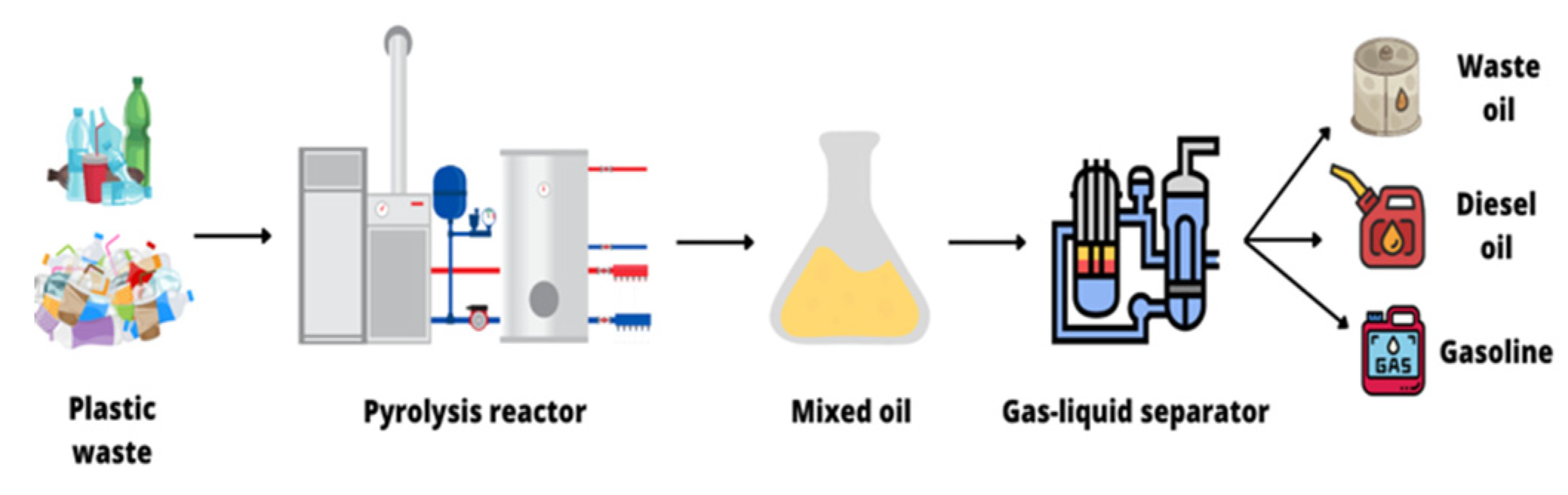

Figure 4.

Pyrolysis recycling process.

Figure 4.

Pyrolysis recycling process.

Recreational use of contaminated waters is another important route. Direct contact with pathogen- and ARG-contaminated plastics during water activities can lead to skin infections, gastrointestinal illness, and other health effects (Kumar et al., 2023; Shuai et al., 2021). Ingesting or inhaling contaminated water during these activities can worsen risk. Agricultural use of contaminated water also matters because irrigation can transfer pathogens and ARGs to crops and contaminate fresh produce (Amato et al., 2021). Eating raw or insufficiently washed fruits and vegetables can then expose people to these contaminants.

Environmental sources of ARGs also complicate medical treatment. When people are exposed to ARGs, these genes can be acquired by pathogenic bacteria within the human microbiome, potentially undermining standard antibiotic therapies (Amarasiri et al., 2020). This dynamic contributes to the global antibiotic resistance crisis, making infections harder to treat, increasing healthcare costs, and posing a serious threat to public health.

6. Management and Mitigation Strategies

Reducing plastic pollution in aquatic environments requires effective waste management systems. Recycling strategies, such as advanced sorting and chemical recycling, have improved removal and recovery of plastic waste (Lange, 2021). Chemical recycling methods, including pyrolysis, gasification, and depolymerization, break plastics down into monomers through chemical reactions (

Figure 3). These methods produce new, high-quality plastics without the degradation issues in mechanical recycling, reducing plastic waste and the environmental footprint of virgin plastic production (Ragaert et al., 2017). Advanced sorting tools, such as near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) and X-ray fluorescence (XRF), can precisely identify and separate different polymers from mixed waste streams, improving recycling efficiency and lowering contamination in recycled materials (Wu et al., 2020).

Developing and using biodegradable plastics and alternative materials is another promising way to mitigate plastic pollution (Moshood et al., 2022). Biodegradable plastics are designed to decompose more quickly under natural conditions, which can lessen their persistence. Their performance depends on temperature, humidity, and microbial activity. While many studies show effective degradation in controlled composting, breakdown in aquatic environments is often slower and less consistent. In addition, innovative materials, such as bioplastics made from renewable resources, provide a sustainable alternative to conventional petroleum-based plastics (Baltaci et al., 2024). While these materials have the potential to reduce the ecological footprint of plastic manufacturing and disposal, further research and development are necessary to ensure they meet the functional requirements of traditional plastics.

Policies and regulations also play a key role in addressing plastic pollution. Many policies now aim to cut single-use plastics, boost recycling, and develop sustainable alternatives. For instance, numerous regions have banned plastic bags and straws (Chen et al., 2021). Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) shifts accountability to manufacturers for a product’s full lifecycle, including end-of-life management (Maitre-Ekern, 2021). These policies encourage recyclable design and investment in recycling infrastructure. In addition, international agreements, such as the Basel Convention, now cover plastic waste, helping limit illegal dumping and lower plastic pollution and related microbial risks (Wu, 2022).

Community engagement and public awareness are critical in lowering plastic pollution. Raising public awareness about the environmental and health impacts of plastic pollution can shift behavior by reducing single-use plastics, improving waste disposal, and increasing participation in recycling. Community efforts, such as beach cleanups, school programs, and social media campaigns, have mobilized people to act (Sinha et al., 2024). Collaboration among governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the private sector is also critical. When communities are engaged in waste-management initiatives and support actions to reduce plastic use, these strategies are far more effective.

Improving wastewater treatment is another key step to limit the spread of pathogens and ARGs via plastics. Advanced processes, including advanced oxidation (AOPs), membrane bioreactors (MBRs), and ultraviolet (UV) disinfection, can remove or inactivate pathogens and ARGs effectively. AOPs, such as ozonation, photocatalysis, or Fenton reactions, use highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (.OH) to degrade extracellular DNA (eDNA), microorganisms, and organic compounds that facilitate microbial adhesion and gene transfer (Sun et al., 2022). In MBRs, plastics and associated microorganisms are removed through a combination of biological degradation and membrane filtration, which lowers levels of pathogens, ARGs, and growth-supporting nutrients (Wang et al., 2024). UV disinfection inactivates pathogens, plastic-associated microbes, and ARGs by damaging nucleic acids, preventing replication and reducing microbial loads in wastewater (Cai et al., 2021). Integrating these advanced processes into treatment plants can markedly improve removal and inactivation efficiency, limiting the release of pathogen- and ARG-bearing plastics to treated waters.

Strengthening regulations and monitoring programs is also critical for restricting the spread of pathogens and ARGs linked to plastics (Da Costa et al., 2020). Regulatory frameworks should set strict limits on plastic discharges and promote best practices in plastic waste management. Regular monitoring of pathogens and ARGs on plastic debris provides essential data on problem extent and intervention effectiveness, informing policy adjustments and public outreach.

Developing new methods to control microbes on plastic surfaces is another key priority. Promising approaches include antimicrobial coatings and biocidal agents that inhibit adhesion, survival, and contamination (DeFlorio et al., 2021). Antimicrobial coatings release active compounds that disrupt cell functions and help prevent biofilm formation, while biocidal agents can be incorporated into plastics or applied to plastic waste to kill or inactivate microbes by damaging membranes, denaturing proteins, or interfering with DNA. Parallel studies on the fate and transport of plastic-associated pathogens and ARGs can clarify impacts and pathways, guiding more effective removal methods and strategies to limit resistance gene dissemination (Junaid et al., 2022).

Comprehensive regulatory frameworks are essential to address plastic pollution and related microbial risks. Governments can set strict rules to limit single-use plastics, encourage biodegradable and sustainable alternatives, and establish standards for plastic waste management. Policies should prioritize waste reduction at the source, higher recycling rates, and circular economy practices (Robaina et al., 2020). EPR should also be mandated so manufacturers manage end-of-life impacts.

International collaboration and agreements, such as the Basel Convention amendments on plastic waste, are vital for regulating transboundary flows and promoting sustainable management. International bodies, including the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and other multilateral environmental agreements, can foster cooperation to share best practices, technologies, and strategies (Filho and Velis, 2022). A global framework for plastic waste management would help align efforts, standardize regulations, and strengthen collective action.

Continued research and innovation are essential to develop new approaches that mitigate the environmental and health impacts of plastic pollution. Governments and international organizations can provide research grants for projects on plastic pollution management, such as advanced recycling techniques, waste management infrastructure, biodegradable materials, antimicrobial coatings, biocidal agents, and studying the fate and transport of plastic-associated pathogens and ARGs in the environment. Collaboration between the public and private sectors can catalyze innovation by combining expertise and resources, and interdisciplinary research centers can accelerate the development of effective solutions.

7. Challenges and Future Directions

A major gap in our understanding is the long-term ecological impact of plastic-associated pathogens and ARGs in aquatic systems. Short-term studies have revealed their presence and distribution, but further studies are needed to monitor persistence, bioaccumulation, and ecological effects over time. Clarifying the consequences of chronic, low-dose exposure on organisms and ecosystems will help inform practical management.

Another challenge is limited information on how pathogens and ARGs on plastics vary across space and time in different waters. Much of the work to date focuses on specific regions or water bodies, leaving global patterns unclear. We also need a better understanding of how temperature, salinity, and nutrients shape settlement and growth on plastics. Broad surveys and standardized sampling protocols are essential to close these data gaps.

Microbial interactions on plastic surfaces add further complexity. Plastic-associated biofilms host diverse communities whose interactions influence ARG transmission and persistence. The underlying mechanisms, such as transformation, transduction, and conjugation, are not yet fully resolved, and the effects of stressors like pollutants and antibiotics on community structure and resistance profiles remain uncertain. Advancing molecular tools is critical to clarify these dynamics.

Technical challenges also limit detection and measurement. Molecular techniques, such as PCR, qPCR, and metagenomics, have expanded our capabilities, but issues with sensitivity, specificity, inhibitors, low DNA abundance, and high-throughput data analysis still pose problems. More sensitive methods and standardized protocols are needed for reliable monitoring.

Effective management requires multidisciplinary approaches, but research and are often fragmented. Integrating environmental engineering, science, microbiology, public health, and policy, together with stronger collaboration across academia, industry, and government, will help translate science into practice. Current regulations tend to target visible plastics, while overlooking microscopic dimensions such as pathogens and ARGs. Hence, it is crucial to develop policies that consider the entire lifecycle of plastics (i.e., from production to disposal) and include microbial risk assessment. Additionally, global collaboration and regulatory alignment are essential to tackle this issue effectively.

Raising public awareness and engagement is another key challenge. Microbial risks from plastic pollution are often overshadowed by more visible impacts. Educating stakeholders, such as policymakers, industry leaders, and the public, about the threats posed by plastic-associated pathogens and ARGs is essential for building support for mitigation. Public outreach and community programs can promote responsible behavior and encourage participation in efforts to reduce plastic waste.

Future research should prioritize the long-term fate and transport of plastics and their associated microbial communities across different aquatic settings. In particular, it is important to study the processes and factors that determine plastic degradation over time, such as temperature, salinity, UV radiation, and microbial activity. Interactions between plastics and other pollutants, such as heavy metals and organic contaminants, need further study to determine their cumulative effects on microbial communities. Monitoring how microbial communities and ARGs on plastics change over time is essential for building predictive models of their impact on ecosystems and public health. The potential for pathogens and ARGs to bioaccumulate and biomagnify through aquatic food webs also needs further study to assess indirect risks to people.

Enhancing the detection and quantification methods for pathogens and ARGs on plastic surfaces is another critical research area. Using advanced molecular techniques, such as CRISPR-based assays and single-cell genomics, together with standardized sampling and analytical protocols will enable more precise identification and characterization of microbial contaminants and resistance genes. Furthermore, combining these techniques with imaging methods, such as confocal laser scanning microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), can offer a better understanding of the spatial distribution and interactions of microbial communities on plastics.

Research should also focus on developing and evaluating effective methods to mitigate the impacts of plastics on the environment and public health. This work should include advancing wastewater treatment to remove or inactivate plastic-associated pathogens and ARGs, developing antimicrobial coatings and biocidal agents to prevent colonization and biofilm formation, and clarifying how biodegradable plastics degrade and affect microbial communities so that more sustainable materials can be developed. In addition, comprehensive risk assessments are needed to evaluate health and ecological impacts across exposure pathways, including ingestion of contaminated water and food, skin contact, and inhalation of microplastic particles.

8. Conclusions

Plastics act as major vectors for transporting pathogens and ARGs in aquatic systems. Their persistence and capacity to provide surfaces for microbial adhesion and biofilm formation create favorable conditions for these agents to aggregate and spread. Previous studies have shown that pathogenic bacteria and ARGs on plastic can transfer to other microorganisms through HST mechanisms, which will disseminate antibiotic resistance and pose environmental and health risks. The interaction between plastic pollution and microbial risks highlights the need for inclusive understanding and effective management strategies.

Addressing plastics as carriers of pathogens and ARGs requires an interdisciplinary approach. Collaboration among environmental scientists, microbiologists, public health experts, engineers, and policymakers is essential to develop solutions that tackle the full plastics lifecycle, from production and use to disposal. Integrating knowledge from diverse disciplines is also essential to create innovative strategies for detecting, monitoring, and reducing microbial risks related to plastic pollution. In addition, facilitating collaboration among academia, industry, and government can speed the translation of scientific findings into effective policies and practical applications, building a coordinated, resilient response to this global challenge.

In summary, prioritizing research is vital to clarify interactions among plastics, pathogens, and ARGs and to develop effective mitigation strategies. Policies should be updated to address microscopic dimensions of plastic pollution, such as microbial risk assessment, and to strengthen international partnerships for regulatory alignment. Public education and community initiatives can encourage responsible behavior and participation in plastic reduction efforts. Overall, a comprehensive and collaborative approach can reduce plastic-associated microbial risks to ecosystems and human health, supporting a more sustainable future.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written by the sole author, who confirms approval of the final version and responsibility for all content. The author conceived the study, designed the methodology, prepared figures, and wrote and revised the manuscript.

Data availability

Supplementary information: SI contains: i) Table showing studies on pathogens and plastics in aquatic environments; ii) Table comparing some molecular biology m=techniques for detecting pathogens and ARGs in plastics

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by ND-ECI Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Notre Dame and SGI Grant (#SGI-2025-02) at Marian University.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- Adamu, H.; Haruna, A.; Zango, Z. U.; Garba, Z. N.; Musa, S. G.; Yahaya, S. M.; Akinpelu, A. A. Microplastics and Co-pollutants in Soil and Marine Environments: Sorption and Desorption Dynamics in Unveiling Invisible Danger and Key to Ecotoxicological Risk Assessment. Chemosphere 2024, 142630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Siddiqui, S. A.; Khan, S. A.; Ali, A.; Chaudhary, N. Cultural and Molecular Approaches to Analyse Antimicrobial Resistant Bacteria from Environmental Samples. In Microbial Diversity in the Genomic Era; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 759–776. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.; Simpson, S. L.; Bertsch, P. M.; Bibby, K.; Bivins, A.; Blackall, L. L.; Choi, P. M. Minimizing errors in RT-PCR detection and quantification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA for wastewater surveillance. Science of the Total Environment 805 2022, 149877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasiri, M.; Sano, D.; Suzuki, S. Understanding human health risks caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) in water environments: Current knowledge and questions to be answered. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2020, 50(19), 2016–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.; Dasí, D.; González, A.; Ferrús, M. A.; Castillo, M. Á. Occurrence of antibiotic resistant bacteria and resistance genes in agricultural irrigation waters from Valencia city (Spain). Agricultural Water Management 256 2021, 107097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Y.; Mir, A. R.; Zieliński, P.; Hayat, S.; Bajguz, A. Microplastics and nanoplastics: source, behavior, remediation, and multi-level environmental impact. Journal of Environmental Management 356 2024, 120618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avarre, J.; de Lajudie, P.; Béna, G. Hybridization of genomic DNA to microarrays: a challenge for the analysis of environmental samples. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2007, 69(2), 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltacı, N. G.; Baltacı, M. Ö; Görmez, A.; Örtücü, S. Green alternatives to petroleum-based plastics: production of bioplastic from Pseudomonas neustonica strain NGB15 using waste carbon source. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2024, 31(21), 31149–31158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belioka, M.; Achilias, D. S. The effect of weathering conditions in combination with natural phenomena/disasters on microplastics’ transport from aquatic environments to agricultural soils. Microplastics 2024, 3(3), 518–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R. A. H.; Sidiq, M. J.; Altinok, I. Impact of microplastics and nanoplastics on fish health and reproduction. Aquaculture 2024, 741037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Yadav, S. K. CRISPR-Cas for genome editing: classification, mechanism, designing and applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 238, 124054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, C.; Datlinger, P.; Chardon, F.; Coelho, M. A.; Dong, M. B.; Lawson, K. A.; Song, B. High-content CRISPR screening. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2022, 2(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Sun, T.; Li, G.; An, T. Traditional and emerging water disinfection technologies challenging the control of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes. Acs Es&T Engineering 2021, 1(7), 1046–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Yang, Y.; Liang, X.; Yu, K.; Zhang, T.; Li, X. Metagenomic profiles of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) between human impacted estuary and deep ocean sediments. Environmental Science & Technology 2013, 47(22), 12753–12760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, D.; Zhou, W.; Deng, R.; Yin, L.; Xiao, R.; Lei, Y. Hotspots lurking underwater: insights into the contamination characteristics, environmental fates and impacts on biogeochemical cycling of microplastics in freshwater sediments. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 135132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, F.; Wang, B.; Huang, H.; Luo, Y.; Han, X.; Huang, Z. Ultrasensitive detection of clinical pathogens through a target-amplification-free collateral-cleavage-enhancing CRISPR-CasΦ tool. Nature Communications 2025, 16(1), 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Awasthi, A. K.; Wei, F.; Tan, Q.; Li, J. Single-use plastics: Production, usage, disposal, and adverse impacts. Science of the Total Environment 752 2021, 141772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corinaldesi, C.; Canensi, S.; Carugati, L.; Martire, M. L.; Marcellini, F.; Nepote, E.; Danovaro, R. Organic enrichment can increase the impact of microplastics on meiofaunal assemblages in tropical beach systems. Environmental Pollution 292 2022, 118415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, J. P.; Mouneyrac, C.; Costa, M.; Duarte, A. C.; Rocha-Santos, T. The role of legislation, regulatory initiatives and guidelines on the control of plastic pollution. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2020, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, K.; Iankelevich-Kounio, E.; Yakovenko, I.; Koucherov, Y.; Rubin-Blum, M.; Oren, M. Identification of plastic-associated species in the Mediterranean Sea using DNA metabarcoding with Nanopore MinION. Scientific Reports 2020, 10(1), 17533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFlorio, W.; Liu, S.; White, A. R.; Taylor, T. M.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Min, Y.; Scholar, E. M. Recent developments in antimicrobial and antifouling coatings to reduce or prevent contamination and cross-contamination of food contact surfaces by bacteria. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2021, 20(3), 3093–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli-Nasab, B.; Sayyed, R. Z.; Mojahed, L. S.; Rahmani, A. F.; Ghafari, M.; Antonius, S. Biofilm production: A strategic mechanism for survival of microbes under stress conditions. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2022, 42, 102337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Otani, S.; Aarestrup, F. M.; Manaia, C. M. Quantitative PCR versus metagenomics for monitoring antibiotic resistance genes: balancing high sensitivity and broad coverage. FEMS Microbes 2023, 4, xtad008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazu, N. T.; Morrin, A.; Fuku, X.; Mamba, B. B.; Feleni, U. Recent Technologies for the Determination of SARS-CoV-2 in Wastewater. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10(13), e202404698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelsinger, D. R.; Vo, P. L. H.; Klompe, S. E.; Ronda, C.; Wang, H. H.; Sternberg, S. H. Bacterial genome engineering using CRISPR-associated transposases. Nature Protocols 2024, 19(3), 752–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillibert, R.; Balakrishnan, G.; Deshoules, Q.; Tardivel, M.; Magazzù, A.; Donato, M. G.; Lagarde, F. Raman tweezers for small microplastics and nanoplastics identification in seawater. Environmental Science & Technology 2019, 53(15), 9003–9013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, A.; Katayama, H.; Furumai, H. Organic substances interfere with reverse transcription-quantitative PCR-based virus detection in water samples. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2015, 81(5), 1585–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Jia, M.; Xiang, Y.; Song, B.; Xiong, W.; Cao, J.; Zeng, G. Biofilm on microplastics in aqueous environment: Physicochemical properties and environmental implications. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 424, 127286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemdan, B. A.; El-Taweel, G. E.; Goswami, P.; Pant, D.; Sevda, S. The role of biofilm in the development and dissemination of ubiquitous pathogens in drinking water distribution systems: an overview of surveillance, outbreaks, and prevention. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2021, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høiby, N.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Givskov, M.; Molin, S.; Ciofu, O. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2010, 35(4), 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, S. Quantification of antibiotic resistance genes for environmental monitoring: current methods and future directions. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health 2020, 16, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Li, Z.; Peñuelas, J.; Sardan, J.; Wu, Q.; Peng, Y.; Yuan, J. Quantitative assessment on the distribution patterns of microplastics in global inland waters. Communications Earth & Environment 2025, 6(1), 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, K.; Li, Y.; Yao, C.; Jiang, C.; Li, J. Towards the fate of antibiotics and the development of related resistance genes in stream biofilms. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 898, 165554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J. Selective enrichment of antibiotic resistome and bacterial pathogens by aquatic microplastics. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2022, 7, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Siddiqui, J. A.; Sadaf, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, J. Enrichment and dissemination of bacterial pathogens by microplastics in the aquatic environment. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 830, 154720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Kim, D. Short-term buoyant microplastic transport patterns driven by wave evolution, breaking, and orbital motion in coast. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2024, 201, 116248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Singh, E.; Singh, S.; Pandey, A.; Bhargava, P. C. Micro-and nano-plastics (MNPs) as emerging pollutant in ground water: Environmental impact, potential risks, limitations and way forward towards sustainable management. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 459, 141568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarage, P. M.; De Silva, L. A. D. S.; Heo, G. Aquatic environments: A potential source of antimicrobial-resistant Vibrio spp. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2022, 133(4), 2267–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, J. Managing plastic waste─ sorting, recycling, disposal, and product redesign. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021, 9(47), 15722–15738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chia, R. W.; Veerasingam, S.; Uddin, S.; Jeon, W.; Moon, H. S.; Lee, J. A comprehensive review of urban microplastic pollution sources, environment and human health impacts, and regulatory efforts. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 946, 174297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leterme, S. C.; Tuuri, E. M.; Drummond, W. J.; Jones, R.; Gascooke, J. R. Microplastics in urban freshwater streams in Adelaide, Australia: A source of plastic pollution in the Gulf St Vincent. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 856, 158672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; De Haan, W. P.; Cerdà-Domènech, M.; Méndez, J.; Lucena, F.; García-Aljaro, C.; Ballesté, E. Detection of faecal bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes in biofilms attached to plastics from human-impacted coastal areas. Environmental Pollution 2023, 319, 120983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Fang, L.; Yan, X.; Gardea-Torresdey, J. L.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yan, B. Surface functional groups and biofilm formation on microplastics: environmental implications. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 903, 166585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luby, E.; Ibekwe, A. M.; Zilles, J.; Pruden, A. Molecular methods for assessment of antibiotic resistance in agricultural ecosystems: prospects and challenges. Journal of Environmental Quality 2016, 45(2), 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Liu, C.; He, D.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Pan, X. Effects of aging on environmental behavior of plastic additives: Migration, leaching, and ecotoxicity. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 849, 157951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitre-Ekern, E. Re-thinking producer responsibility for a sustainable circular economy from extended producer responsibility to pre-market producer responsibility. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 286, 125454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A. A.; Prasetya, T. A. E.; Dewi, I. R.; Ahmad, M. Microplastics in human food chains: Food becoming a threat to health safety. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 858, 159834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Shisler, J. L.; Nguyen, T. H. Enhanced detection for antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater samples using a CRISPR-enriched metagenomic method. Water Research 2025, 274, 123056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, L. J.; Van Emmerik, T.; Van Der Ent, R.; Schmidt, C.; Lebreton, L. More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. Science Advances 2021, 7(18), eaaz5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miłobedzka, A.; Ferreira, C.; Vaz-Moreira, I.; Calderón-Franco, D.; Gorecki, A.; Purkrtova, S.; Nielsen, P. H. Monitoring antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater environments: the challenges of filling a gap in the One-Health cycle. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022a, 424, 127407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłobedzka, A.; Ferreira, C.; Vaz-Moreira, I.; Calderón-Franco, D.; Gorecki, A.; Purkrtova, S.; Nielsen, P. H. Monitoring antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater environments: the challenges of filling a gap in the One-Health cycle. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022b, 424, 127407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood, T. D.; Nawanir, G.; Mahmud, F.; Mohamad, F.; Ahmad, M. H.; AbdulGhani, A. Sustainability of biodegradable plastics: New problem or solution to solve the global plastic pollution? Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2022, 5, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moter, A.; Göbel, U. B. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for direct visualization of microorganisms. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2000, 41(2), 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, V.; Leoni, B.; Arienzo, M. M.; Hogan, Z. S.; Gandolfi, I.; Tatangelo, V.; Kozloski, R. Plastic pollution affects ecosystem processes including community structure and functional traits in large rivers. Water Research 2024, 259, 121849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoffo, E. D.; Tan, E.; Grinham, A.; Gaddam, S. M. R.; Yip, J. Y. H.; Twomey, A. J.; Bostock, H. Plastic pollution in Moreton Bay sediments, Southeast Queensland, Australia. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 920, 170987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoye, C. O.; Addey, C. I.; Oderinde, O.; Okoro, J. O.; Uwamungu, J. Y., I; chukwu, C. K.; Odii, E. C. Toxic chemicals and persistent organic pollutants associated with micro-and nanoplastics pollution. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2022, 11, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormsby, M. J.; Woodford, L.; White, H. L.; Fellows, R.; Oliver, D. M.; Quilliam, R. S. Toxigenic Vibrio cholerae can cycle between environmental plastic waste and floodwater: implications for environmental management of cholera. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 461, 132492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Wang, N., I; dayaraj, J.; Majima, T. Virus on surfaces: Chemical mechanism, influence factors, disinfection strategies, and implications for virus repelling surface design. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2023, 320, 103006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogue, J. M.; Kaye, K. S.; Cohen, D. A.; Marchaim, D. Appropriate antimicrobial therapy in the era of multidrug-resistant human pathogens. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2015, 21(4), 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Port, J. A.; Cullen, A. C.; Wallace, J. C.; Smith, M. N.; Faustman, E. M. Metagenomic frameworks for monitoring antibiotic resistance in aquatic environments. Environmental Health Perspectives 2014, 122(3), 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruden, A.; Larsson, D. J.; Amézquita, A.; Collignon, P.; Brandt, K. K.; Graham, D. W.; Snape, J. R. Management options for reducing the release of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes to the environment. Environmental Health Perspectives 2013, 121(8), 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroga, G.; Vásquez-Ponce, F.; Martins-Gonçalves, T.; Lincopan, N. Microplastics in marine pollution: Oceanic hitchhikers for the global dissemination of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. One Health 2025, 20, 101056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaert, K.; Delva, L.; Van Geem, K. Mechanical and chemical recycling of solid plastic waste. Waste Management 2017, 69, 24–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Galgani, F.; Nicoll, K.; Neal, W. J. Rethinking geological concepts in the age of plastic pollution. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 950, 175366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robaina, M.; Murillo, K.; Rocha, E.; Villar, J. Circular economy in plastic waste-Efficiency analysis of European countries. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 730, 139038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Chowdhury, G.; Mukhopadhyay, A. K.; Dutta, S.; Basu, S. Convergence of biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9, 793615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathicq, M. B.; Sabatino, R.; Corno, G.; Di Cesare, A. Are microplastic particles a hotspot for the spread and the persistence of antibiotic resistance in aquatic systems? Environmental Pollution 2021, 279, 116896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, C.; Schielke, A.; Ellerbroek, L.; Johne, R. PCR inhibitors–occurrence, properties and removal. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2012, 113(5), 1014–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, J. R.; McLellan, S. L. Climate change will amplify the impacts of harmful microorganisms in aquatic ecosystems; Nature Microbiology, 2025; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Sun, C.; An, T.; Jiang, C.; Mei, S.; Lv, B. Unraveling the effect of micro/nanoplastics on the occurrence and horizontal transfer of environmental antibiotic resistance genes: advances, mechanisms and future prospects. Science of the Total Environment 2024a, 174466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Sun, C.; An, T.; Jiang, C.; Mei, S.; Lv, B. Unraveling the effect of micro/nanoplastics on the occurrence and horizontal transfer of environmental antibiotic resistance genes: Advances, mechanisms and future prospects. Science of the Total Environment 2024b, 947, 174466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xia, Y.; Wei, W.; Ni, B. Accelerated spread of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) induced by non-antibiotic conditions: roles and mechanisms. Water Research 2022, 224, 119060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.; Alhammali, A.; Bigler, L.; Vohra, N.; Peszynska, M. Coupled flow and biomass-nutrient growth at pore-scale with permeable biofilm, adaptive singularity and multiple species. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 2021, 18(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, W.; Huang, L. Microbial diversity in extreme environments. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2022, 20(4), 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Sun, Y.; Meng, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, L.; Lin, Z.; Chen, H. Dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes in swimming pools and implication for human skin. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 794, 148693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, A.; Hubab, M.; Rasheela, A. R. P.; Samad, R.; Al-Ghouti, M.; Sayadi, S.; Zouari, N. Microplastics and their role in the emergence of antibiotic resistance in bacteria as a threat for the environment. Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology 2025, 7, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Filho, C. R.; Velis, C. A. United Nations’ plastic pollution treaty pathway puts waste and resources management sector at the centre of massive change. Waste Management & Research 2022, 40(5), 487–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R. K.; Kumar, R.; Phartyal, S. S.; Sharma, P. Interventions of citizen science for mitigation and management of plastic pollution: Understanding sustainable development goals, policies, and regulations; Science of the Total Environment, 2024; p. 176621. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C. J.; Osborn, A. M. Advantages and limitations of quantitative PCR (Q-PCR)-based approaches in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2009a, 67(1), 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C. J.; Osborn, A. M. Advantages and limitations of quantitative PCR (Q-PCR)-based approaches in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2009b, 67(1), 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, B.; Wang, H. Ozone and Fenton oxidation affected the bacterial community and opportunistic pathogens in biofilms and effluents from GAC. Water Research 2022, 218, 118495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syranidou, E.; Kalogerakis, N. Interactions of microplastics, antibiotics and antibiotic resistant genes within WWTPs. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 804, 150141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.; Bauer, D. E.; Chiarle, R. Assessing and advancing the safety of CRISPR-Cas tools: from DNA to RNA editing. Nature Communications 2023, 14(1), 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Du, Y.; Luo, X.; Dong, J.; Chen, S.; Hu, X.; Abolfathi, S. Understanding visible light and microbe-driven degradation mechanisms of polyurethane plastics: Pathways, property changes, and product analysis. Water Research 2024, 259, 121856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, S. Y.; Citartan, M.; Gopinath, S. C.; Tang, T. Aptamers as a replacement for antibodies in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2015, 64, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, K. A.; Nguyen, T. A.; Nguyen, T. P. Advances in Pretreatment Methods for Free Nucleic Acid Removal in Wastewater Samples: Enhancing Accuracy in Pathogenic Detection and Future Directions. Applied Microbiology 2023, 4(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, K.; Yang, G.; Wang, B.; Tawfiq, K.; Chen, G. Bacterial interactions and transport in geological formation of alumino-silica clays. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2015, 125, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Meng, L.; Men, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ma, K. Microplastics in anoxic/aerobic membrane bioreactor (A/O-MBR): Characteristics, biofilms, degradation and carrier for antibiotic resistance genes. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, 62, 105395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qin, X.; Guo, J.; Jia, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y. Evidence of selective enrichment of bacterial assemblages and antibiotic resistant genes by microplastics in urban rivers. Water Research 2020, 183, 116113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Y.; Pausch, P.; Doudna, J. A. Structural biology of CRISPR–Cas immunity and genome editing enzymes. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2022, 20(11), 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H. A study on transnational regulatory governance for marine plastic debris: Trends, challenges, and prospect. Marine Policy 2022, 136, 103988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.; Yao, L.; Xu, Z. Auto-sorting commonly recovered plastics from waste household appliances and electronics using near-infrared spectroscopy. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020a, 246, 118732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.; Yao, L.; Xu, Z. Auto-sorting commonly recovered plastics from waste household appliances and electronics using near-infrared spectroscopy. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020b, 246, 118732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Chio, C.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Qin, W. Colonization characteristics and surface effects of microplastic biofilms: Implications for environmental behavior of typical pollutants. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 173141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Song, W.; Ye, C.; Lin, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, W. Plastics in the marine environment are reservoirs for antibiotic and metal resistance genes. Environment International 2019, 123, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaniv, K.; Ozer, E.; Shagan, M.; Lakkakula, S.; Plotkin, N.; Bhandarkar, N. S.; Kushmaro, A. Direct RT-qPCR assay for SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (Alpha, B. 1.1. 7 and Beta, B. 1.351) detection and quantification in wastewater. Environmental Research 2021, 201, 111653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashir, N.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ma, M.; Wang, D.; Feng, Y.; Song, X. Co-occurrence of microplastics, PFASs, antibiotics, and antibiotic resistance genes in groundwater and their composite impacts on indigenous microbial communities: A field study. Science of the Total Environment 2025, 961, 178373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Sun, Y.; Li, B.; Feng, Z.; Wu, G. The r/K selection theory and its application in biological wastewater treatment processes. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 824, 153836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Man, Y. B.; Mo, W. Y.; Man, K. Y.; Wong, M. H. Direct and indirect effects of microplastics on bivalves, with a focus on edible species: A mini-review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2020, 50(20), 2109–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lei, H.; Huang, J.; Wong, J. W. C.; Li, B. Co-occurrence and co-expression of antibiotic, biocide, and metal resistance genes with mobile genetic elements in microbial communities subjected to long-term antibiotic pressure: Novel insights from metagenomics and metatranscriptomics. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2025, 489, 137559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, F.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, M.; Sun, F.; Yang, L.; Hao, H. Advances in metagenomics and its application in environmental microorganisms. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 766364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Coin, L.; O’Brien, J.; Hai, F.; Jiang, G. Molecular methods for pathogenic bacteria detection and recent advances in wastewater analysis. Water 2021, 13(24), 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Tang, J. Interaction between microplastic biofilm formation and antibiotics: effect of microplastic biofilm and its driving mechanisms on antibiotic resistance gene. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 459, 132099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Tang, J.; Tang, K.; An, M.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z.; He, C. Selective enrichment of bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes in microplastic biofilms and their potential hazards in coral reef ecosystems. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Li, S.; Tao, C.; Chen, W.; Chen, M.; Zong, Z.; Yan, B. Understanding the mechanism of microplastic-associated antibiotic resistance genes in aquatic ecosystems: Insights from metagenomic analyses and machine learning. Water Research 2025, 268, 122570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).