1. Introduction

Originally regarded as an atmospheric pollutant, nitric oxide (NO) has undergone reappraisal and is now recognised as a potent biological signalling molecule [

1]. Alongside local effects in wound healing, melanogenesis and lipogenesis [

2,

3,

4] NO facilitates extracellular cross talk modulating blood flow within arteries [

5], with loss implicated in hypertension [

6,

7]. This is mediated by endothelial secretion of NO, which diffuses to adjacent vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) eliciting vasodilatory response [

8] The activity of nitric oxide synthases (NOS), enzymes responsible for NO production within the endothelium, play a critical role in this process. However, NOS activity declines with age, which can impair vascular function [

9,

10].

Liberation of NO from salts held at high concentration within keratinocytes (the primary skin cell making up 90% of the skins epidermis) by UV provides secondary effect on VSMC [

11,

12] and may be beneficial with highest impact within subsets of the population where enzyme-based response has waned [

9,

10]. Recent studies have suggested that light emitting diode (LED) and lasers emitting longer wavelengths, specifically blue (400-500nm), red visible light (620-780nm) and near infra-red (780-1000nm) may also facilitate NO release via non-enzymatic mediators [

13,

14]. Should such a response be recapitulated via exposure of skin to visible light as part of low-level solar exposures (for example morning or evening where significantly lower ultraviolet B irradiance occurs outside the midday peak) [

15,

16]. This represents an important consideration for public health, as ultraviolet radiation exerts a range of deleterious effects on skin cells under high or prolonged exposure, including the modulation of inflammatory pathways, induction of photo-immunosuppression, and acceleration of photoaging [

17]. Moreover, ultraviolet radiation is recognised as a ‘complete carcinogen’ capable of both tumour initiation and promotion with numerous epidemiological studies demonstrating strong associations with increased incidence of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma [

18].

In this study, we assess NO release

in vitro by visible blue or red/infra-red light derived from a filtered solar simulator light source which mimics terrestrial sunlight levels. Here we opt for these exposures on the basis that previous work suggests NO is induced with negligible genotoxic effect [

9,

19]. We report no detectable increase in NO up to 2 hours after exposure.

2. Materials and Methods

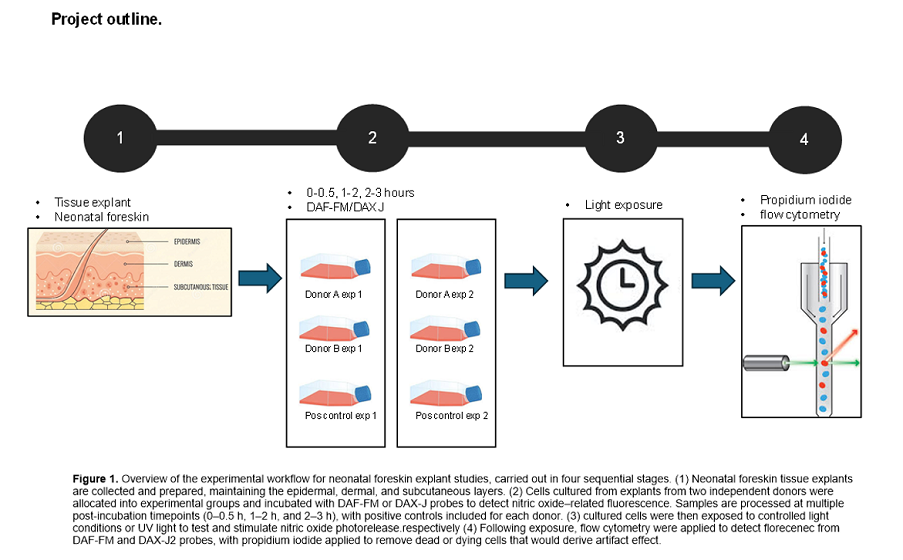

2.1. Primary Cell Isolation and Culture

Primary keratinocyte, fibroblast and endothelial cell lines were isolated from two white skinned (Fitzpatrick scale type I and II) non-related neonatal foreskins (≤1 month old) collected post-circumcision and grown in culture, as previously described [

9,

19]. Informed consent was obtained prior to tissue collection, under approval from the South-Central Berkshire B Ethics Committee (22/SC/0411, IRAS ID 31832). For experiments, cells were seeded at a density of 250,000 cells per well and cultured for four days to reach confluency.

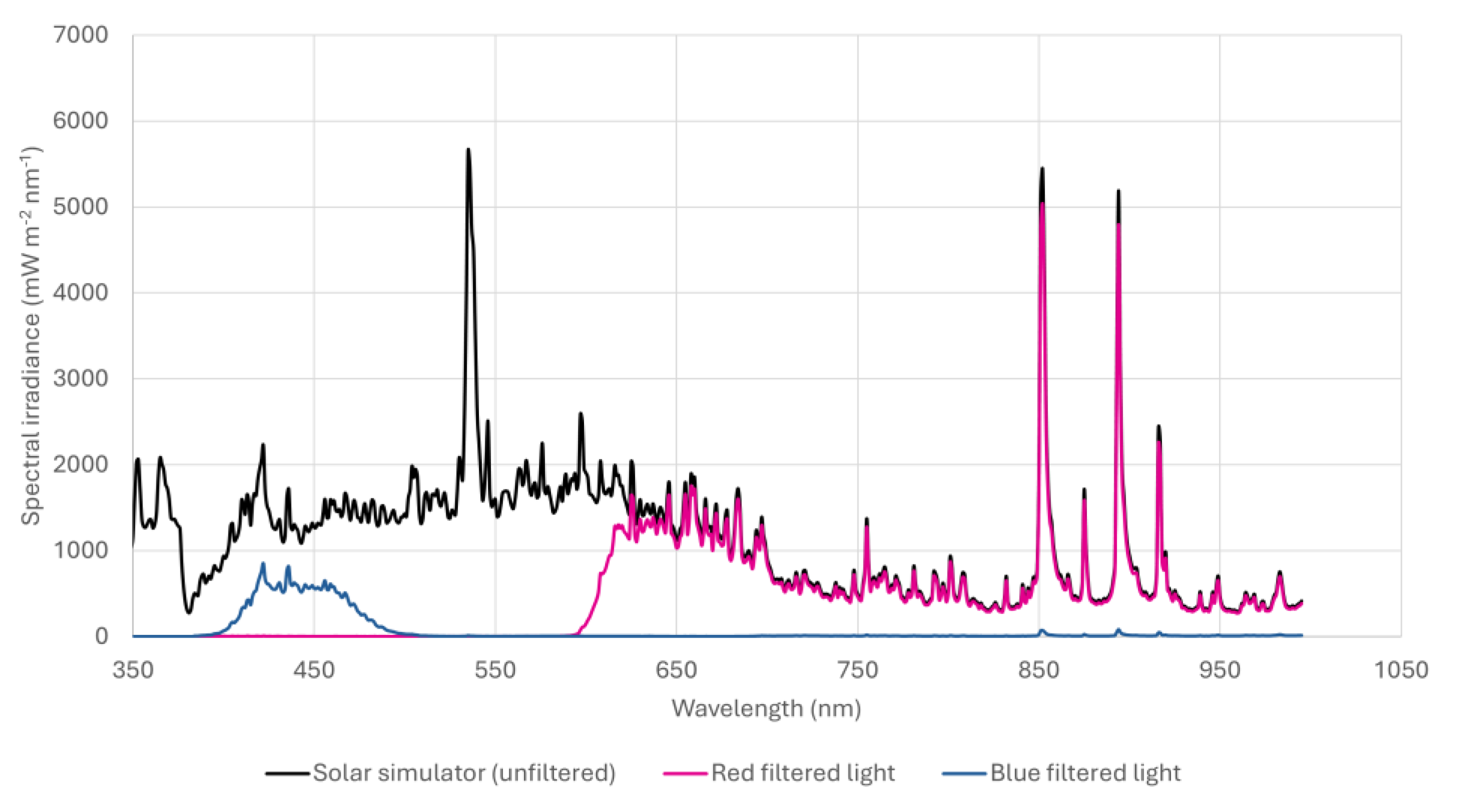

2.2. Exposure of Cell Cultures to Light

Visible light exposures were performed following removal of cell culture media and replacement with PBS +/+ (phosphate-buffered saline with calcium and magnesium) (CSR156 Appleton woods ™) on cell monolayers, as preliminary work and other studies have shown light exposure can induce the photodegradation of media constituents such as tryptophan, resulting in the liberation of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and subsequent non-physiological oxidative stress in cell monolayers in turn also upregulating reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and NO [

20,

21]. Exposures were conducted using a SOL-2 solar simulator (Dr Hönle AG UV-Technologies™), modified to include an internal fan to dissipate heat. Desired spectral regions were isolated using a combination of long-wave and band-pass filters (

Figure 1). Filters were mounted on shielded lids providing a gap between plate and filter for air flow to prevent excess heat, previously identified as arising from radiation absorbed by the filter when positioned too close to the cells [

19]. Cell monolayers were exposed to either 4.86 J/cm

2 blue light (400-510 nm) at an irradiance of 5.40 mW/cm

2, or 20.32 J/cm

2 10.14 J/cm

2 red (600-780 nm), and 10.18 J/cm

2 infra-red (780-900 nm) at an irradiance of 33.9 mW/cm

2. Positive controls, known to induce NO release through increased florescence from probes DAF-FM and DAX-J2 used to detect presence [

19] were incorporated into the study, via use of the BIOSUN UV device (VILBER LOURMAT™). The positive controls were irradiated with 1 J/cm

2 UV-B. The BIOSUN incorporates live dose and temperature monitoring ensuring consistent dose delivery, thus accurate delivery of positive controls was ensured.

2.3. Nitric Oxide Detection

NO levels were assessed using DAF-FM diacetate (DAF-FM DA; Molecular Probes, D23844) and DAX-J2 Red (16301-AATB, AAT BIOQUEST™), with either propidium iodide (P3566, THERMO fisher ™) or CELL-TOX green (G8741, PROMOCELL™) added respectively prior to flow cytometry but after visible light exposure to remove dead or dying cells. Use of alternate probes exciting within the blue and red spectrum respectively after light exposure, allowed quenching of the probe (providing erroneous results) to be subverted when blue and red light were administered, as we experienced within previous work [

19].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism™ using an ordinary one-way ANOVA, with mixed effects model. Significance was set as p < 0.05.

3. Results

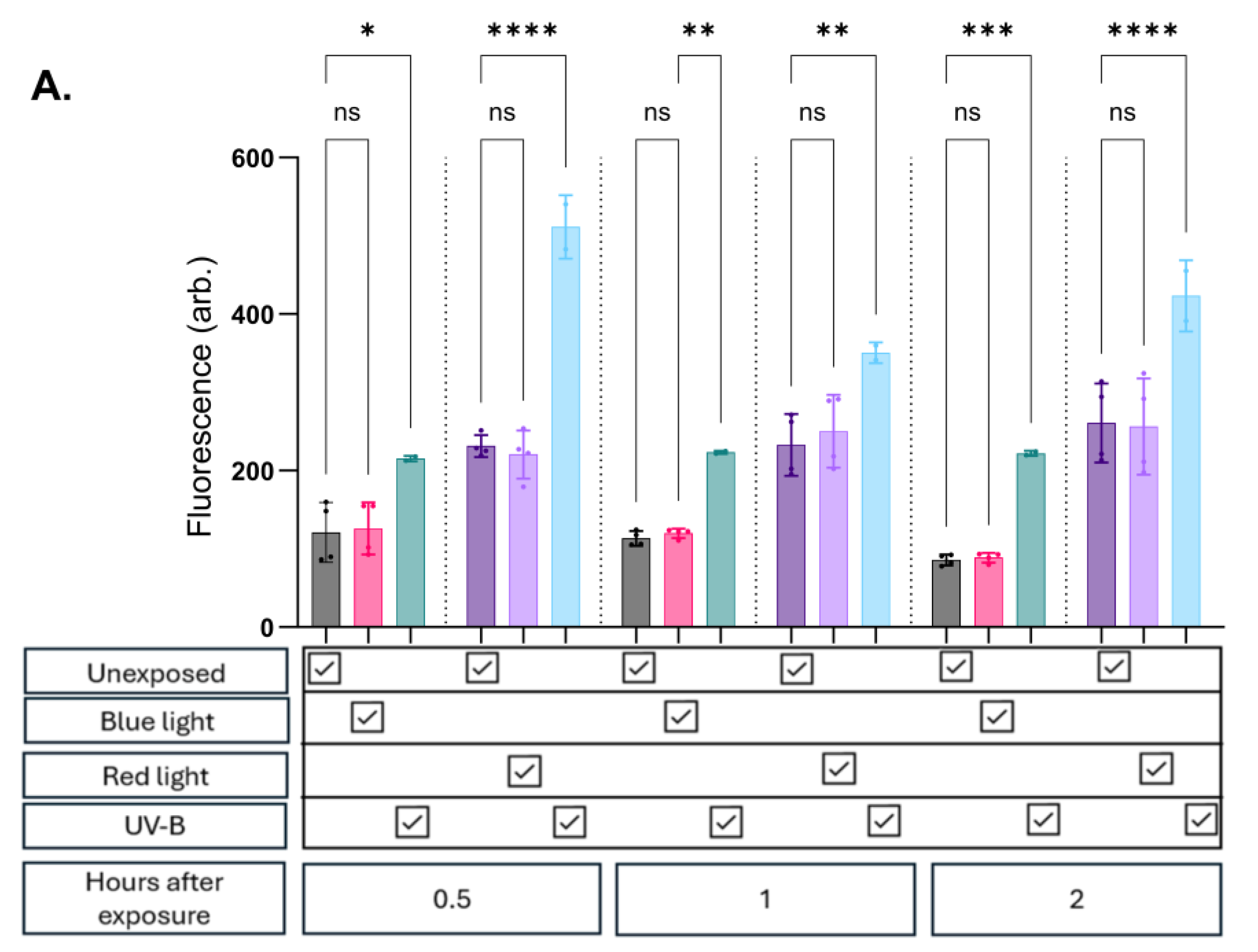

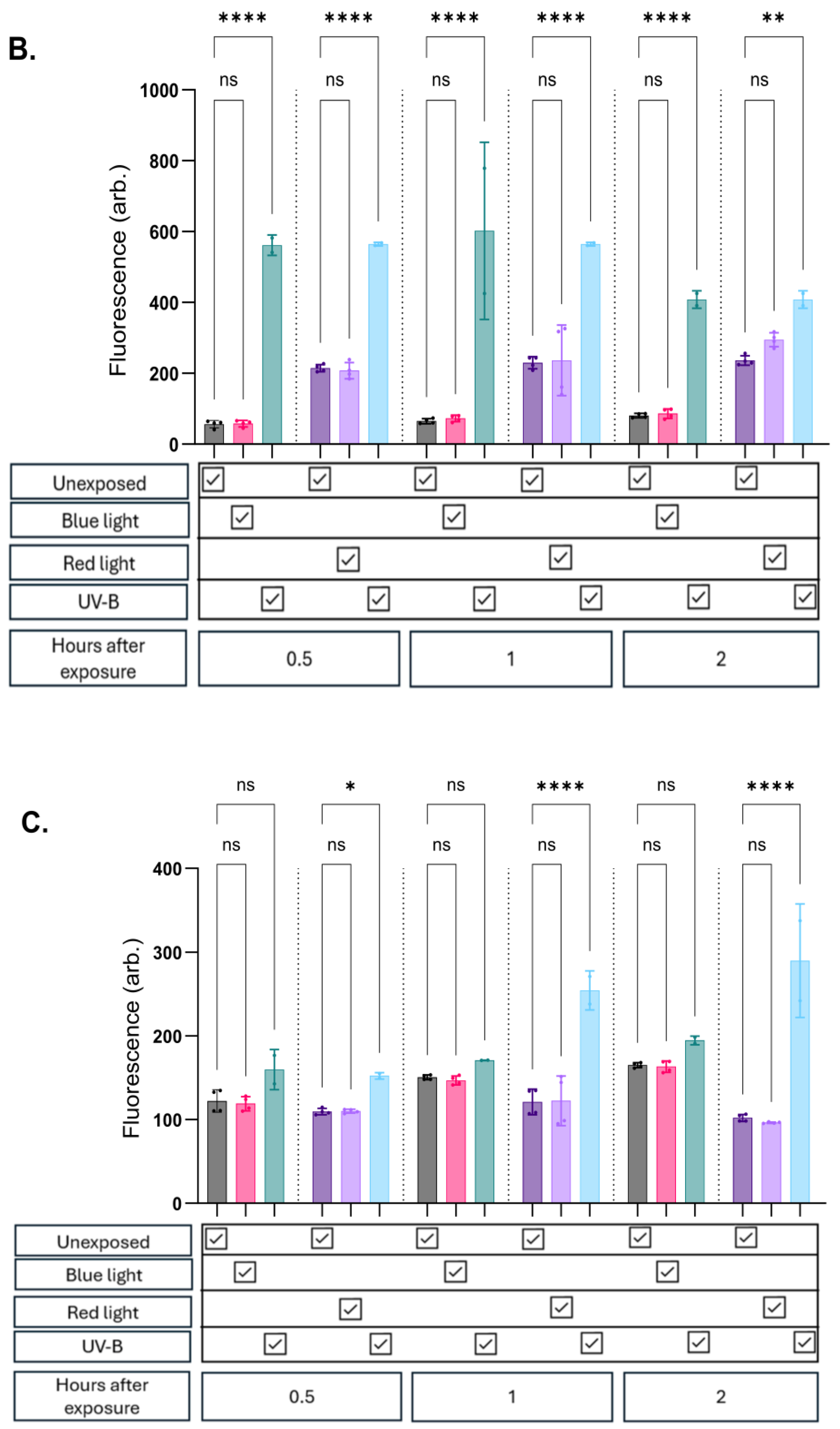

At all evaluated timepoints in all cell lines, there was no significant change in NO expression whether exposed to blue or red/infrared light compared to unexposed controls (

Figure 2a, b and c). Potential thermal effects which could influence the results were accounted for, minimising confounding due to heat exposure.

As expected, exposure to UV-B consistently induced a significant increase in fluorescence in both keratinocyte and endothelial cell lines. In contrast, fibroblasts exhibited a lower propensity for NO upregulation following UV-B exposure. These cells showed modest trends up to 30 minutes post-exposure, with variable (significant and non-significant) increases observed at later timepoints (

Figure 2c). Importantly, foetal bovine serum (FBS) and phenol red were removed from the media prior to probe assessment to prevent interference.

4. Discussion

Our findings diverge from previous studies that report significant NO release following exposure of cells to blue or red light. In non skin-based cell types, Zhang et al demonstrated this at 670 nm observing NO induction following 7.5 J/cm² exposure, while Rohringer et al found NO induction at 24 J/cm

2 of 516 nm or 635 nm light [

22,

23]. Considering this it is feasible that skin cells (routinely exposed to visible light in vivo) may be more resistant to light-induced NO release than other cell types.

This interpretation is challenged by recent work from Barolet et al and Albers et al who demonstrate significant NO production in human skin cells following exposure to visible

light [

24,

25]. Albers et al suggests effect in keratinocytes at 453 nm after 100 J/cm² exposure [

24]

, while Barolet uses a multi-wavelength LED array (455, 650, and 850 nm), delivering blue and red light at an irradiance of 20 mW/cm² to achieve a dose of 15 J/cm² over 12.5 minutes. Barolets study is particularly interesting given the experimental set up closely matches our own in terms of NO detection methodology (via use of DAF-FM diacetate) and incorporation of cell lines in part derived from donors of identical anatomical origin, age, and gender. Additionally, the study not only accounts for unwanted effects from thermal and cytotoxic insults (that may occur as part of light exposure regimens) through a ‘water-cooled irradiation system’ and viability assays but goes one step further, validating the response from the probe through NO induction with the NO scavenger Carboxy-PTIO potassium salt (CPTIO). Here the researchers rule out other signalling intermediates such as ROS which is suggested to also interact with NO probes at a lower threshold [

25].

It is likely that delivery of visible light outside these specific narrow bands over much broader spectral ranges at levels representative for low level terrestrial sunlight exposure goes some way to explaining the lack of response seen in the results presented here. Proof of this lies in Barolets study where blue light exposures were ~3 times higher dose applied when compared against our own work (4.86 J/cm

2 vs 15 J/cm

2), this may be sufficient to initiate photolysis of S-nitrosothiols (RSNOs) [

13,

26,

27]. Inferred as RSNO photolysis is tied into blue light release of NO, owing to the fact that the metabolite requires lower energy than photoreduction of nitrite (23–34 kcal/mol

) [

28,

29,

30]. Further supporting this interpretation is prior cited work in cutaneous and non-cutaneous cell types, including that by Albers et al who demonstrate NO release at 453 ± 10 nm, at doses upwards of 20 J/cm².[

24]. Together, these findings suggest low level exposures to sunlight may not be sufficient to elicit biologically meaningful NO production without UV (applied sun protection, diurnal or seasonal drop), raising important questions about the physiological plausibility of this mechanism under certain real-world conditions.

An additional consideration for future work is the addition of trace biological cofactors absent in the current model but present in whole tissue and blood. This is inferred given reports suggesting interplay with protein and non-protein bound intermediates lost as part of the cell isolation process [

26,

27,

31]. Opländer et al highlights this for visible light exposures with the addition of copper (Cu) catalysing RSNO decomposition to NO under blue-light exposure [

27]. This is feasible

in vivo, as both free copper and copper-containing enzymes may contribute to nitric oxide-related chemistry, although they represent distinct entities. Free copper ions are present within the epidermis at low micromolar concentrations (approximately 1–30 µM), whereas copper-containing enzymes such as ceruloplasmin circulate in plasma at slightly higher levels (12–25 µM) [

27]. Similarly, Dejam et al demonstrate thiols lost during purification of cell isolation and culture markedly enhance photolytic nitrate breakdown, increasing NO generation and RSNO formation [

31]. Although these studies provide an interesting counterpoint to our own work and provide mechanistic proof-of-principle, as experimental levels are supraphysiological (and likely enhance efficiency), it remains important to follow up claims under conditions approximating environmental levels found

in vivo. Case in point is Opländer’s work that utilises 100 µM copper chloride (CuCl₂), greater than physiological levels highlighted earlier [

27].

Red and near-infrared light doses used in our study were broadly comparable to those reported by Barolet [

25] but applied over broader spectral regions rather than specific narrow wavebands. Here, higher dose thresholds for wavelengths understood to interact with mitochondrial chromophores may be a factor [

32,

33]. These interactions may therefore lead to the photodissociation of NO that is transiently bound to cytochrome c oxidase, a key enzyme of the mitochondrial respiratory chain

, [

34]. Thus, although we did not observe significant NO production under red light exposure, broad spectrum wavebands opted for over narrow wavebands may be a factor. Additionally, as mitochondrial NO may account for a small proportion of total NO production in some cells such as endothelial cells which possess only 2–5% the mitochondrial content of other cell types relying primarily on glycolysis for ATP production [

35], this may also be a factor explaining the results in this study.

Finally, a critical but often overlooked factor in

in-vitro studies of light-induced NO release is the medium used during irradiation. Several studies, including those by Albers, Rohringer, Zhang, and Oppländer, clearly state that cells were exposed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [

22], [

23,

24,

27,

36]. However, many studies do not specify whether the culture medium was removed or replaced prior to light exposure which is a significant omission, as media components such as tryptophan can degrade under light to generate ROS, RNS, or NO indirectly [

37]. Without standardisation in exposure conditions, it becomes difficult to confidently attribute observed signals to direct NO production. We found that chronic exposure of media, to blue light in particular, prior to addition of cells led to complete cytotoxicity (data not shown), thus even transient exposures from LED’s may have considerable effects on inflammatory pathways mediating ROS, RNS and NO induction.

5. Conclusions

The concept of visible-light-induced nitric oxide release remains of practical importance. While several studies have demonstrated NO generation using LED-based light sources, these findings have not been consistently replicated under conditions that reflect low-level environmental exposures. Such low-level exposures are relevant to mimic natural sunlight exposure while avoiding peak UV exposure. Discrepancies in exposure conditions including light source, dose, spectral power distribution and cell media may underlie conflicting reported results.

Future work should aim to replicate these effects in more complex models that incorporate key biological cofactors, maintain native tissue architecture, and simulate environmental light conditions. This will be essential for an assessment of the potential for visible light to elicit meaningful NO-mediated effects outside of controlled clinical settings

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, GH, POM and MK. methodology GH, POM and MK. formal analysis GH, investigation GH, writing—original draft preparation GH.; writing—review and editing POM, MK,.

Funding

This study is part funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Protection Research Unit in Chemical and Radiation Treats and Hazards, a partnership between UK Health Security Agency and Imperial College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, UKHSA or the Department of Health and Social Care. The authors also would like to thank Phil Miles of UKHSA for the design and construction of temperature-controlled stage which was critical for consistency of outdoor experiments.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All methods described above were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. For human tissue research ethics approval was granted under South-central Berkshire B ethics committee 22/SC/0411, IRAS ID 31832. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All methods described above were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NO |

Nitric oxide |

| LED |

Light Emitting Diode |

| NOS |

Nitric oxide synthase |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

| H2O2 |

Hydrogen peroxide |

| RNS |

Reactive nitrogen species |

| CPTIO |

Carboy PTIO potassium salt |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| RSNO |

S-nitrosothiols |

| Cu |

Copper |

| CuCl2 |

Copper Chloride |

| FBS |

Fetal Bovine Serum |

References

- Power, D.; Boyle, M. Nitric Oxide: A Positive Poison. Australian Critical Care 1995, 8(1), 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone-Povolny, M.J.; Maloney, S.E.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Nitric Oxide Therapy for Diabetic Wound Healing. Advanced Healthcare Materials, [online] 2019, 8(12), 1801210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razny, U.; Kiec-Wilk, B.; Wator, L.; Polus, A.; Dyduch, G.; Solnica, B.; Malecki, M.; Tomaszewska, R.; Cooke, J.P.; Dembinska-Kiec, A. Increased nitric oxide availability attenuates high fat diet metabolic alterations and gene expression associated with insulin resistance. Cardiovascular Diabetology 2011, 10(1), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roméro-Graillet, C; Aberdam, E; Clément, M; Ortonne, JP; Ballotti, R. Nitric oxide produced by ultraviolet-irradiated keratinocytes stimulates melanogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1997, 99(4), 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning, RJ; Felliciano, L. Coronary artery blood flow: physiologic and pathophysiologic regulation. Clin Cardiol. 1999, 22(12), 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joannides, R.; Haefeli, W.E.; Linder, L.; Richard, V.; Bakkali, E.H.; Thuillez, C.; Lüscher, T.F. Nitric Oxide Is Responsible for Flow-Dependent Dilatation of Human Peripheral Conduit Arteries In Vivo. Circulation 1995, 91(5), 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, K.M. The role of nitric oxide in cardiovascular diseases. Molecular aspects of medicine, [online] 2005, 26(1-2), 33–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph Loscalzo, Jin, (2010), Vascular nitric oxide: formation and function, Journal of Blood, Page 147, doi:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3092409/.

- Hazell, G.; Khazova, M.; Cohen, H.; Felton, S.; Raj, K. Post-exposure persistence of nitric oxide upregulation in skin cells irradiated by UV-A. Scientific Reports 2022, 12(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-M.; Huang, A.; Kaley, G.; Sun, D. eNOS uncoupling and endothelial dysfunction in aged vessels. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2009, 297(5), H1829–H1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliman, G.; Lowe, D.; Cohen, H.; Felton, S.; Raj, K. Ultraviolet Radiation-Induced Production of Nitric Oxide:A multi-cell and multi-donor analysis. Scientific Reports, [online] 2017, 7, 11105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suschek, C.V.; Feibel, D.; von Kohout, M.; Opländer, C. Enhancement of Nitric Oxide Bioavailability by Modulation of Cutaneous Nitric Oxide Stores. Biomedicines 2022, 10(9), 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barolet, A.C.; Litvinov, I.V.; Barolet, D. Light-induced nitric oxide release in the skin beyond UVA and blue light: Red & near-infrared wavelengths. Nitric Oxide 2021, 117, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashiwagi, S.; Morita, A.; Yokomizo, S.; Ogawa, E.; Komai, Eri; Huang, P.L.; Bragin, D.E.; Atochin, D.N. Photobiomodulation and nitric oxide signaling. In Nitric Oxide; [online], 2022; Volume 130, pp. 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffey, B. Time and Place as Modifiers of Personal UV Exposure. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15(6), 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooke, R.J.; Pearson, A.J.; O’Hagan, J.B. Temporal variation of erythemally effective UVB/UVA ratio at Chilton, UK. Radiation protection dosimetry 2012, 149(2), 185–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X; Yang, T; Yu, D; Xiong, H; Zhang, S. Current insights and future perspectives of ultraviolet radiation (UV) exposure: Friends and foes to the skin and beyond the skin. Environ Int. 2024, 185, 108535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, J.; Jarrett, S.; Amaro-Ortiz, A.; Scott, T. UV radiation and the skin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, [online] 2013, 14(6), 12222–12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, G.; Khazova, M.; O’Mahoney, P. Low-dose daylight exposure induces nitric oxide release and maintains cell viability in vitro. Scientific Reports 2023, 13(1), 16306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahns, A.; Melchheier, I.; Suschek, C.V.; Sies, H.; Klotz, L.-O. Irradiation of cells with ultraviolet-A (320-400 nm) in the presence of cell culture medium elicits biological effects due to extracellular generation of hydrogen peroxide. Free radical research, [online] 2003, 37(4), 391–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzelak, A.; Rychlik, B.; Bartosz, G. Light-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species in cell culture media. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2001, 30(12), 1418–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohringer, S.; Holnthoner, W.; Chaudary, S.; Slezak, P.; Priglinger, E.; Strassl, M.; Pill, K.; Mühleder, S.; Redl, H.; Dungel, P. The impact of wavelengths of LED light-therapy on endothelial cells. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1), 10700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Mio, Y.; Pratt, P.C.; Lohr, N.L.; Warltier, D.C.; Whelan, H.T.; Zhu, D.; Jacobs, E.A.; Medhora, Meetha; Bienengraeber, M. Near infrared light protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia and reoxygenation injury by a nitric oxide dependent mechanism. 2009, 46(1), 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albers, I.; Zernickel, E.; Stern, M.; Broja, M.; Busch, Hans Lucas; Heiss, C.; Grotheer, V.; Windolf, Joachim; Suschek, C.V. Blue light (λ=453 nm) nitric oxide dependently induces β-endorphin production of human skin keratinocytes in-vitro and increases systemic β-endorphin levels in humans in-vivo. Free radical biology & medicine 2019, 145, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barolet, A.C.; Magne, B.; Barolet, D.; Germain, L. Differential Nitric Oxide Responses in Primary Cultured Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts to Visible and Near-Infrared Light. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 13(10), 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opländer, C.; Deck, A.; Volkmar, C.M.; Kirsch, M.; Liebmann, J.; Born, M.; van Abeelen, Frank; Faassen, van; Kröncke, Klaus-Dietrich; Windolf, Joachim; Suschek, C.V. Mechanism and biological relevance of blue-light (420–453 nm)-induced nonenzymatic nitric oxide generation from photolabile nitric oxide derivates in human skin in vitro and in vivo. Free Radical Biology and Medicne 2013a, 65, 1363–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opländer, C.; Müller, T.; Baschin, M.; Bozkurt, A.; Grieb, G.; Windolf, J.; Pallua, N.; Suschek, C.V. Characterization of novel nitrite-based nitric oxide generating delivery systems for topical dermal application. Nitric Oxide 2013b, 28, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, L.F.; Hamblin, M.R. Proposed Mechanisms of Photobiomodulation or Low-Level Light Therapy. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2016, 22(3), 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A.B.; Trullas, C.; Kohli, I.; Hamzavi, I.H.; Lim, H.W. Photoprotection beyond ultraviolet radiation: A review of tinted sunscreens. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2020, 84(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barolet, D. Photobiomodulation in Dermatology: Harnessing Light from Visible to Near Infrared. Medical Research Archives 2018, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejam, A.; Kleinbongard, P.; Rassaf, T.; Hamada, S.; Gharini, P.; Rodriguez, J.; Feelisch, M.; Kelm, M. Thiols enhance NO formation from nitrate photolysis. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2003, 35(12), 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyton, R.O.; Ball, K.A. Therapeutic photobiomodulation: nitric oxide and a novel function of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase. Discovery Medicine, [online] 2011, 11(57), 154–159. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21356170/.

- Quirk, B.J.; Whelan, H.T. What Lies at the Heart of Photobiomodulation: Light, Cytochrome C Oxidase, and Nitric Oxide—Review of the Evidence. Photobiomodulation, Photomedicine, and Laser Surgery 2020, 38(9), 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, TH; Wider, JM; Lee, I; et al. Inhibitory modulation of cytochrome c oxidase activity with specific near-infrared light wavelengths attenuates brain ischemia/reperfusion injury. Sci Rep. Published. 2018, 8(1), 3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, DL; Robinson, AT; Rossman, MJ; Seals, DR; Edwards, DG. Mitochondrial contributions to vascular endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular diseases. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021, 320(5), H2080–H2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, N.L.; Keszler, Á.; Pratt, P.F.; Bienengraber, M.; Warltier, D.C.; Hogg, N. Enhancement of nitric oxide release from nitrosyl hemoglobin and nitrosyl myoglobin by red/near infrared radiation: Potential role in cardioprotection. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2009, 47(2), 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmaine, S; Schnellbaecher, A; Zimmer, A. Reactivity and degradation products of tryptophan in solution and proteins. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020, 160, 696–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).