Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

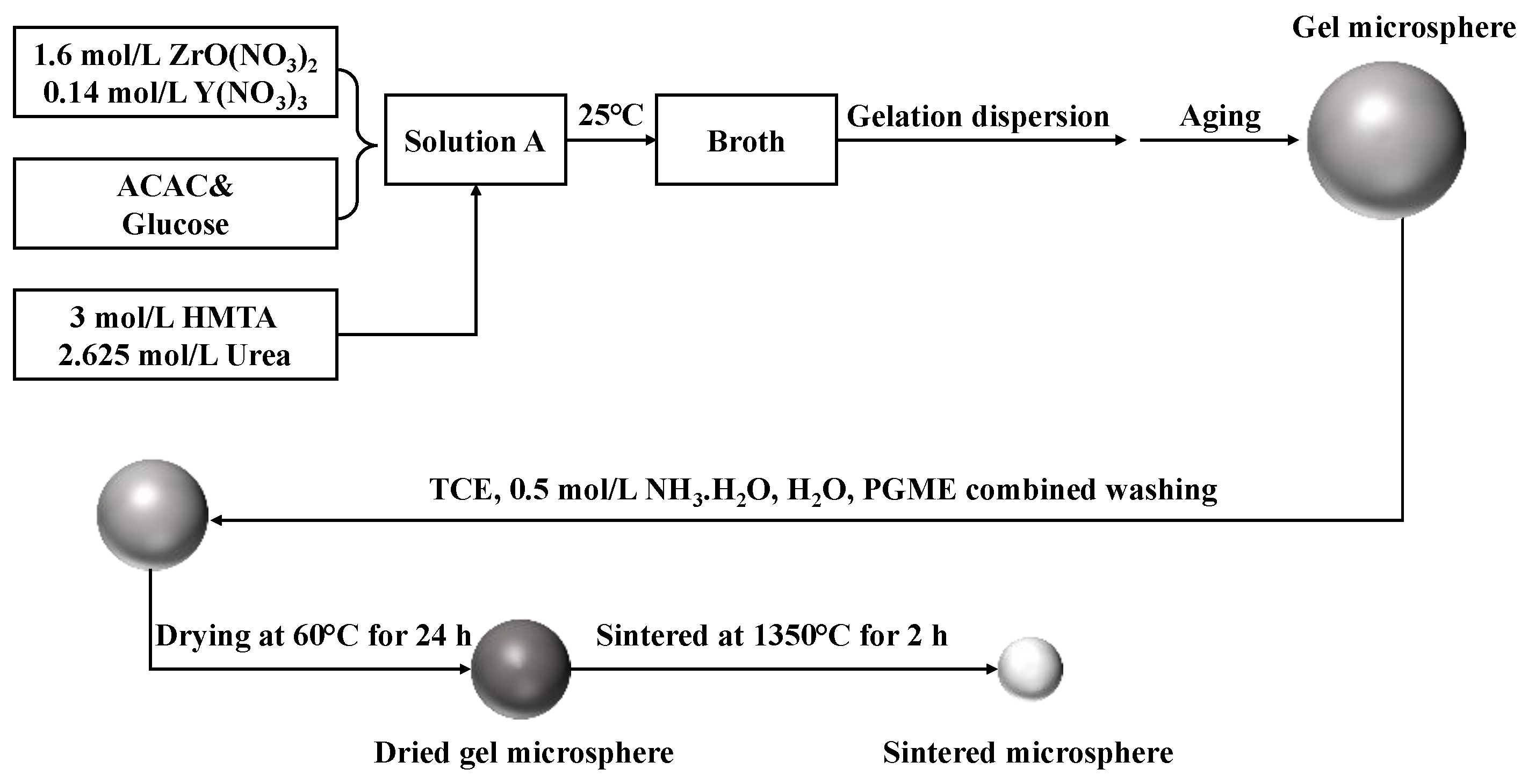

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Stable Zirconium Broth

2.3. Preparation of Gel Microspheres

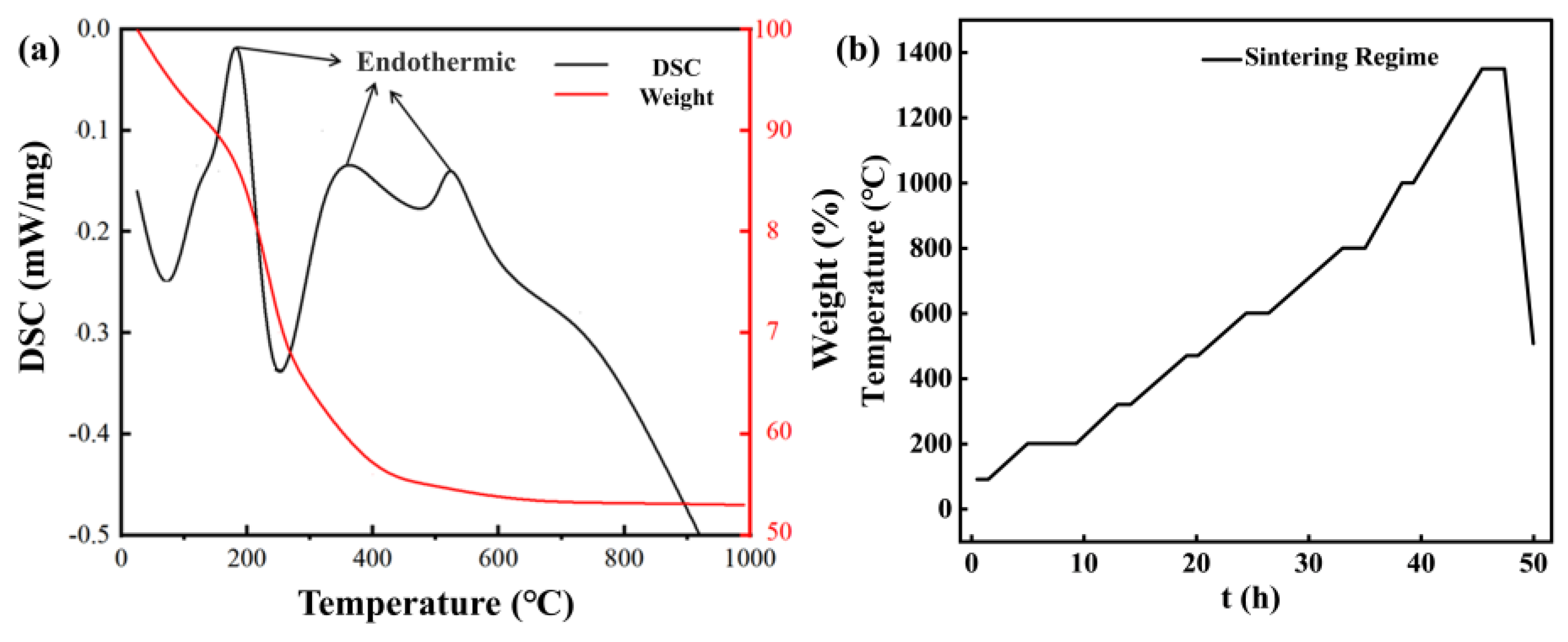

2.4. Thermal Treatment and Sintering

2.5. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

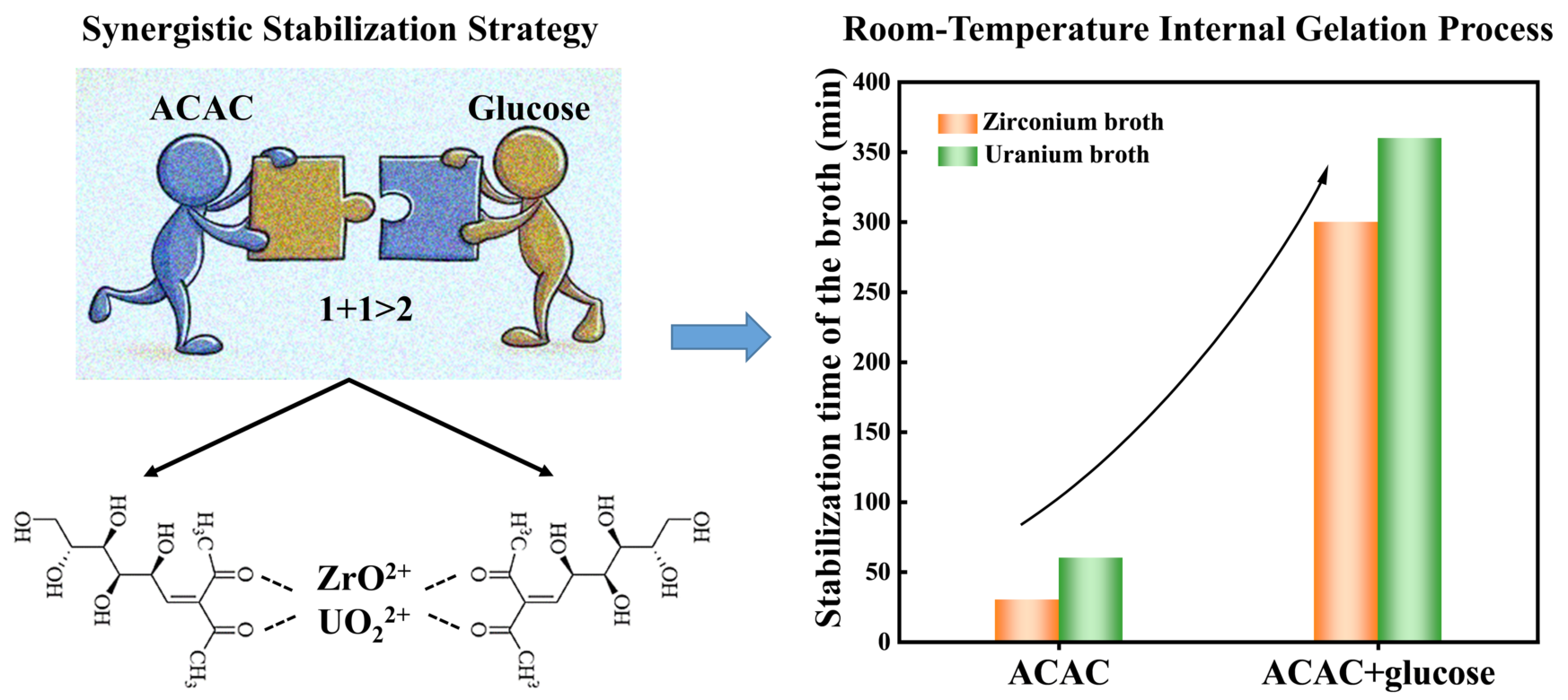

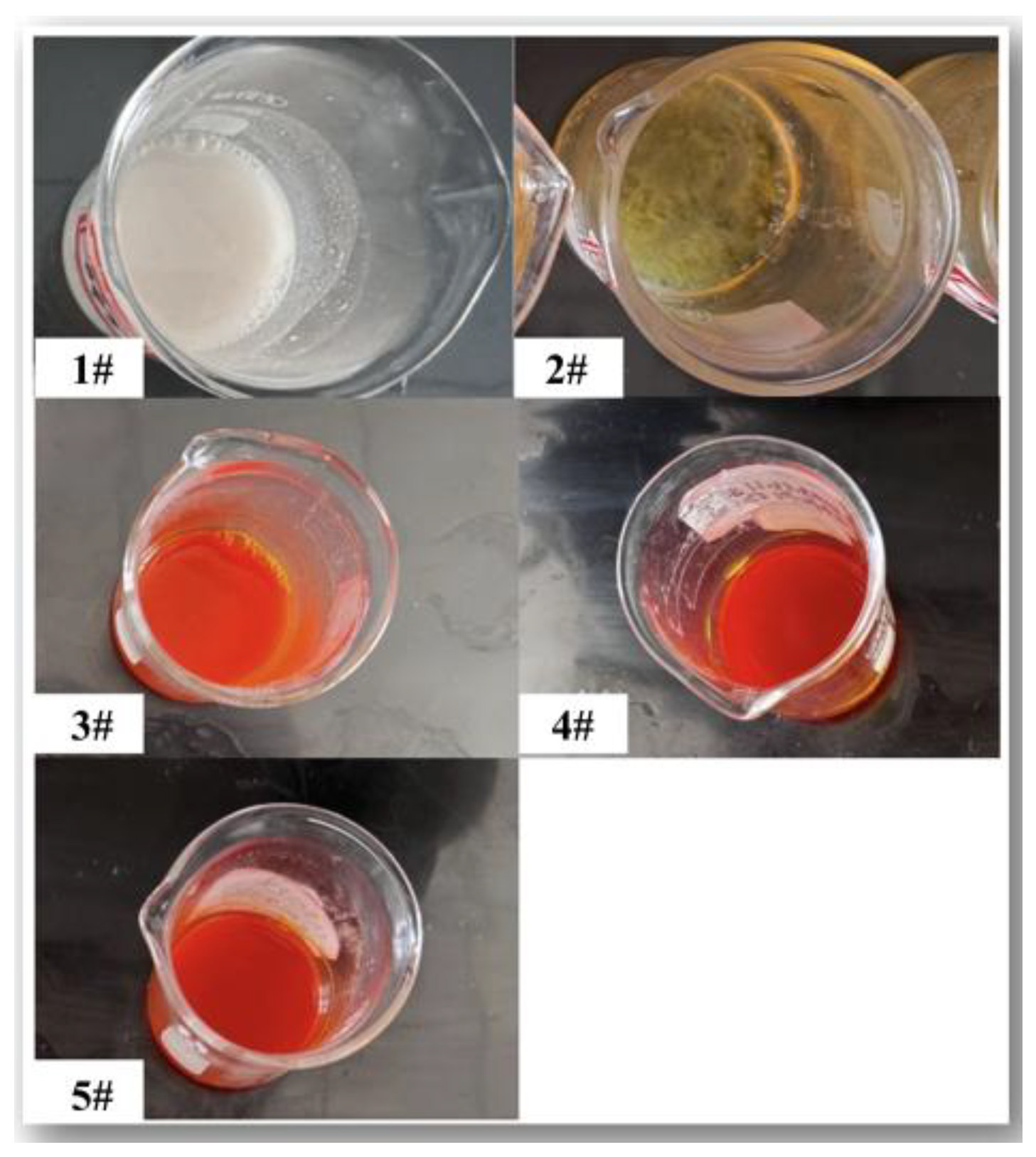

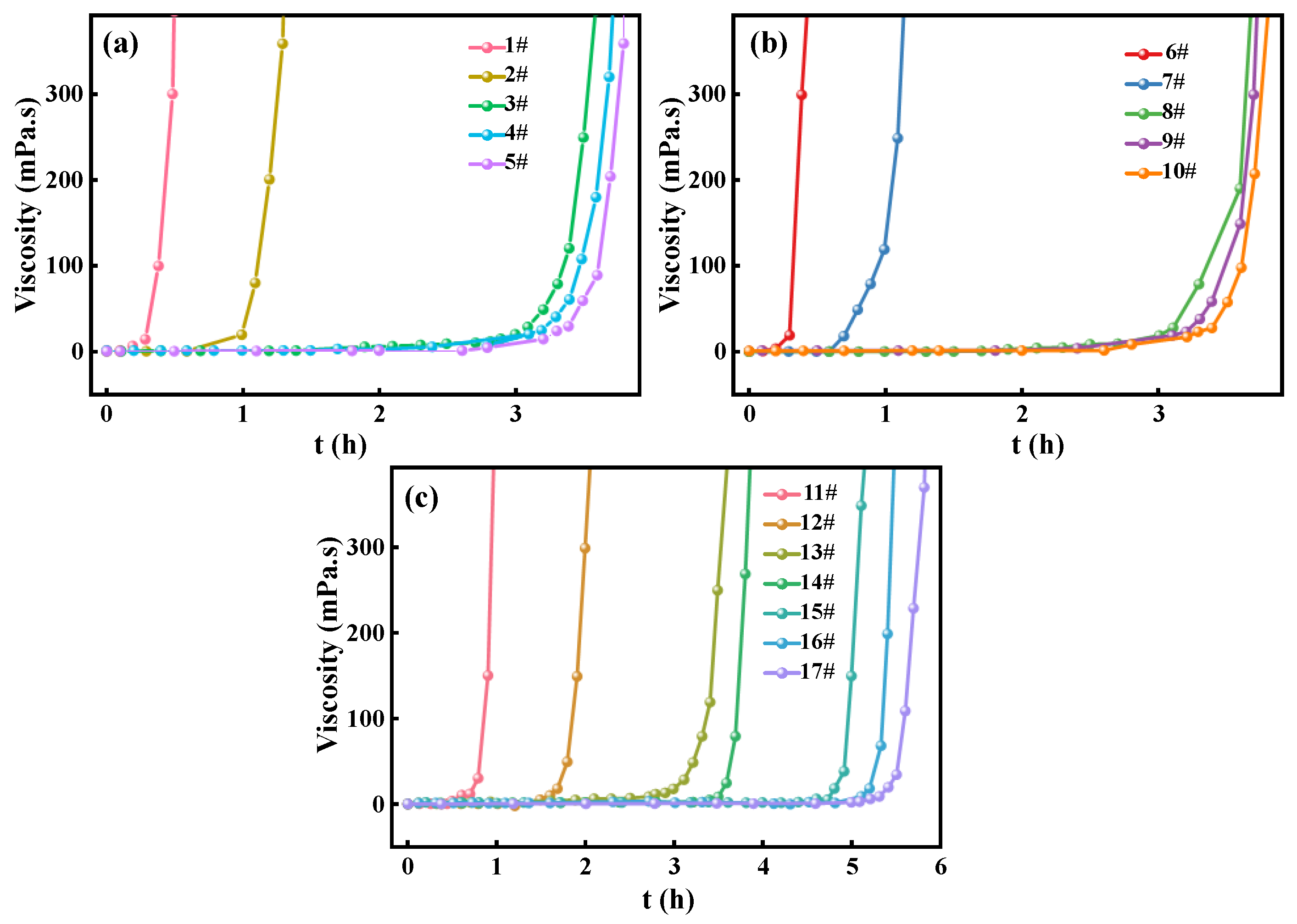

3.1. Effect of ACAC and Glucose on the Stability of Zirconium Broth

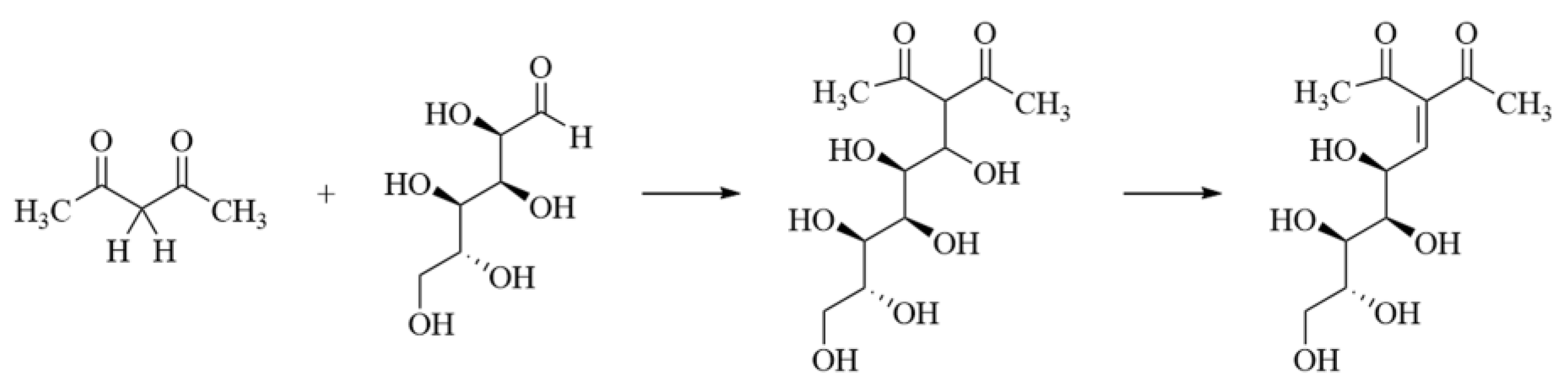

3.2. Stabilization Mechanism of the Zirconium Broth with ACAC and Glucose

3.3. Comparative Study of YSZ Microsphere Properties

3.4. Stabilization Mechanism Extended to the Uranium System

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACAC | Acetylacetone |

| HMTA | Hexamethylenetetramine |

| HMUR | Mixed solution of hexamethylenetetramine and urea |

| YSZ | Yttrium stabilized zirconia |

| ADUN | Acid-deficient uranyl nitrate |

References

- Fu, Z.; He, L.; van Rooyen, I.J.; Yang, Y. Comparison of microstructural and micro-chemical evolutions in the irradiated fuel kernels of AGR-1 and AGR-2 TRISO fuel particles. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2024, 176, 105361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Shen, T.; Deng, C.; Hao, S.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Ma, J. A new approach for impregnation of Cs into zirconia microsphere matrix. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 27780–27787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, R.D.; Collins, J.L.; Choi, J.-S. Key properties of mixed cerium and zirconium microspheres prepared by the internal gelation process with previously boiled HMTA and urea. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 23295–23299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhou, X.; Shen, T.; Deng, C.; Hao, S.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Ma, J. Uniform growth of colloidal particles via internal gelation process. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2023, 674, 131557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katalenich, J.A. Production of cerium dioxide microspheres by an internal gelation sol–gel method. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2017, 82, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhao, X.; Hao, S.; Deng, C.; Liu, B. An improved internal gelation process for preparing ZrO2 ceramic microspheres without cooling the precursor solution. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 98, 2732–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lu, Z.; Li, X.; Zeng, F.; Li, J.; Shang, Y. A Study of Stability and Coagulation Behavior of Broth Based the Internal Gelation Process for Uranium Dioxide Microspheres. In the Proceedings of the 23rd Pacific Basin Nuclear Conference, Volume 3: PBNC 2022, Beijing & Chengdu, China, 1-4 November 2023; pp. 332–340. [Google Scholar]

- Arima, T.; Idemitsu, K.; Yamahira, K.; Torikai, S.; Inagaki, Y. Application of internal gelation to sol–gel synthesis of ceria-doped zirconia microspheres as nuclear fuel analogous materials. J. Alloys Compd. 2005, 394, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Song, J.; Zhao, S.; Nie, L.; Deng, C.; Hao, S.; Zhao, X.; Liu, B.; Ma, J. The effect of washing process on the cracking of ZrO2 microspheres by internal gelation. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 5489–5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ma, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Hao, S.; Deng, C.; Liu, B. A comparative study of small-size ceria–zirconia microspheres fabricated by external and internal gelation. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2016, 78, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Bai, J.; Cao, S.; Yin, X.; Tan, C.; Li, P.; Tian, W.; Wang, J.; Guo, H.; Qin, Z. An improved internal gelation process without cooling the solution for preparing uranium dioxide ceramic microspheres. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 2524–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Huang, Z.; Yan, D.; Deng, C.; Liu, B.; Tang, Y.; Ma, J. The controlled preparation of uranium carbide ceramic microspheres by microfluidic-assisted internal gelation process. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 5621–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefali, A.; Franchina, C.; Gianotti, M.; Ficocelli, S.; Ferrero, L.; Bolzacchini, E.; Cipriano, D. Evaluation of Methods for Formaldehyde Measurement in Industrial Emissions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Sopot Youth Conference 2025: Where the World is Heading, 2025; pp. 20–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Eronen, A.; Du, X.; Ma, E.; Guo, M.; Moslova, K.; Repo, T. A catalytic approach via retro-aldol condensation of glucose to furanic compounds. Green Chemistry 2021, 23, 5481–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Liu, X.; Feng, X. Recent advances in metal-catalyzed asymmetric 1, 4-conjugate addition (ACA) of nonorganometallic nucleophiles. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 7586–7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.S.; Tomiyasu, H.; Fukutomi, H. Kinetics and mechanism of the substitution of dibenzoylmethanate for acetylacetonate in the uranyl complex (UO2(acac)2L (L= dimethyl sulfoxide, N, N-dimethylformamide, and trimethyl phosphate). Inorg. Chem. 1986, 25, 2582–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhri, N.; Cong, L.; Grover, N.; Shan, W.; Anshul, K.; Sankar, M.; Kadish, K.M. Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of acetylacetone (acac) and ethyl acetate (EA) appended β-trisubstituted push–pull porphyrins: Formation of electronically communicating porphyrin dimers. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 13213–13224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zheng, J.; Qin, D.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yao, M.; Chen, X.; Li, G.; An, T.; Zhang, R. OH-initiated oxidation of acetylacetone: Implications for ozone and secondary organic aerosol formation. Environmental Science & Technology 2018, 52, 11169–11177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warthegau, S.S.; Jakob, A.; Christensen, M.S.; Vestentoft, A.; Grilc, M.; Likozar, B.; Meier, S. Conversion of Abundant Aldoses with Acetylacetone: Unveiling the Mechanism and Improving Control in the Formation of Functionalized Furans Using Lewis Acidic Salts in Water. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2024, 12, 16652–16660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milián-Medina, B.; Gierschner, J. π-Conjugation. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Molecular Science 2012, 2, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, R.K.; Paul, S.; Gupta, V.K.; Kant, R. Conversion of α, β-unsaturated ketones to 1, 5-diones via tandem retro-Aldol and Michael addition using Co (acac) 2 covalently anchored onto amine functionalized silica. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 1944–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; King, J.; Gorman, B.; Braley, J. Straight-chain halocarbon forming fluids for TRISO fuel kernel production–Tests with yttria-stabilized zirconia microspheres. J. Nucl. Mater. 2015, 458, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S.; Fontanille, P.; Pandey, A.; Larroche, C. Gluconic acid: properties, applications and microbial production. Food Technology & Biotechnology 2006, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Jiao, X.; Chen, D. Preparation of Y-TZP ceramic fibers by electrolysis-sol-gel method. J Mater Sci 2007, 42, 5562–5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suciu, C.; Hoffmann, A.; Vik, A.; Goga, F. Effect of calcination conditions and precursor proportions on the properties of YSZ nanoparticles obtained by modified sol–gel route. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 138, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.B.; Shopov, D.Y.; Sharninghausen, L.S.; Vinyard, D.J.; Mercado, B.Q.; Brudvig, G.W.; Crabtree, R.H. A stable coordination complex of Rh (IV) in an N, O-donor environment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 15692–15695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurley, J.M.; Hunt, R.D.; McMurray, J.W.; Nelson, A.T. Synthesis of U3O8 and UO2 microspheres using microfluidics. J. Nucl. Mater. 2022, 566, 153784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Shaw, L.L. FTIR analysis of the hydrolysis rate in the sol–gel formation of gadolinia-doped ceria with acetylacetonate precursors. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2010, 53, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Liang, M.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Xue, B.; Zhao, H. Effect of chelating agent acetylacetone on corrosion protection properties of silane-zirconium sol–gel coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 363, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Zr/Y solution (mL) |

n(HMTA /ZrO2+) |

n(ACAC /ZrO2+) |

n(C6H12O6/ZrO2+) | n(ACAC/C6H12O6) | Stability time of zirconium broths (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | 10 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2# | 10 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 30 |

| 3# | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 180 |

| 4# | 10 | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 180 |

| 5# | 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 180 |

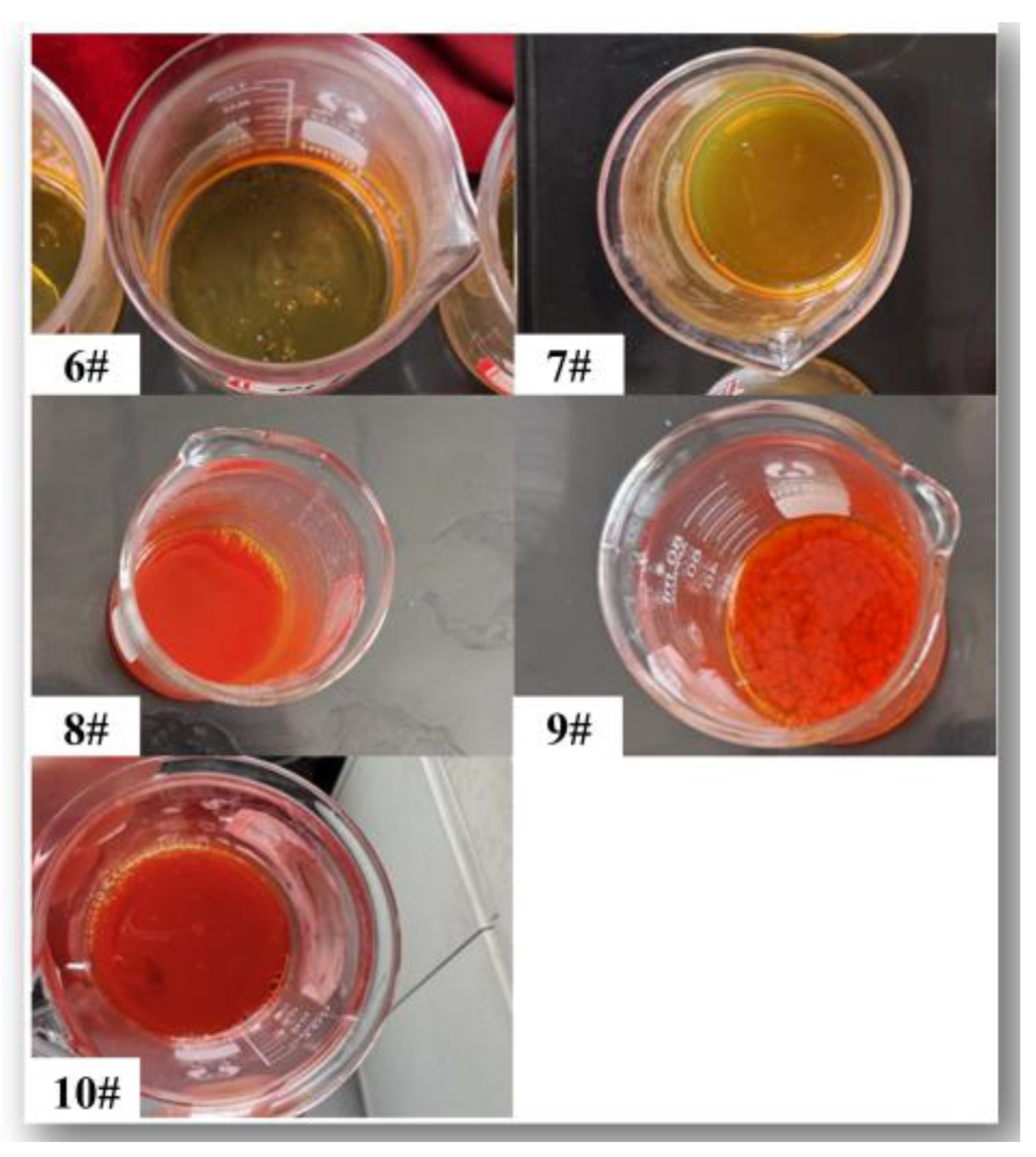

| 6# | 10 | 2 | 1 | 0 | - | 30 |

| 7# | 10 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 50 |

| 8# | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 180 |

| 9# | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 180 |

| 10# | 10 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 180 |

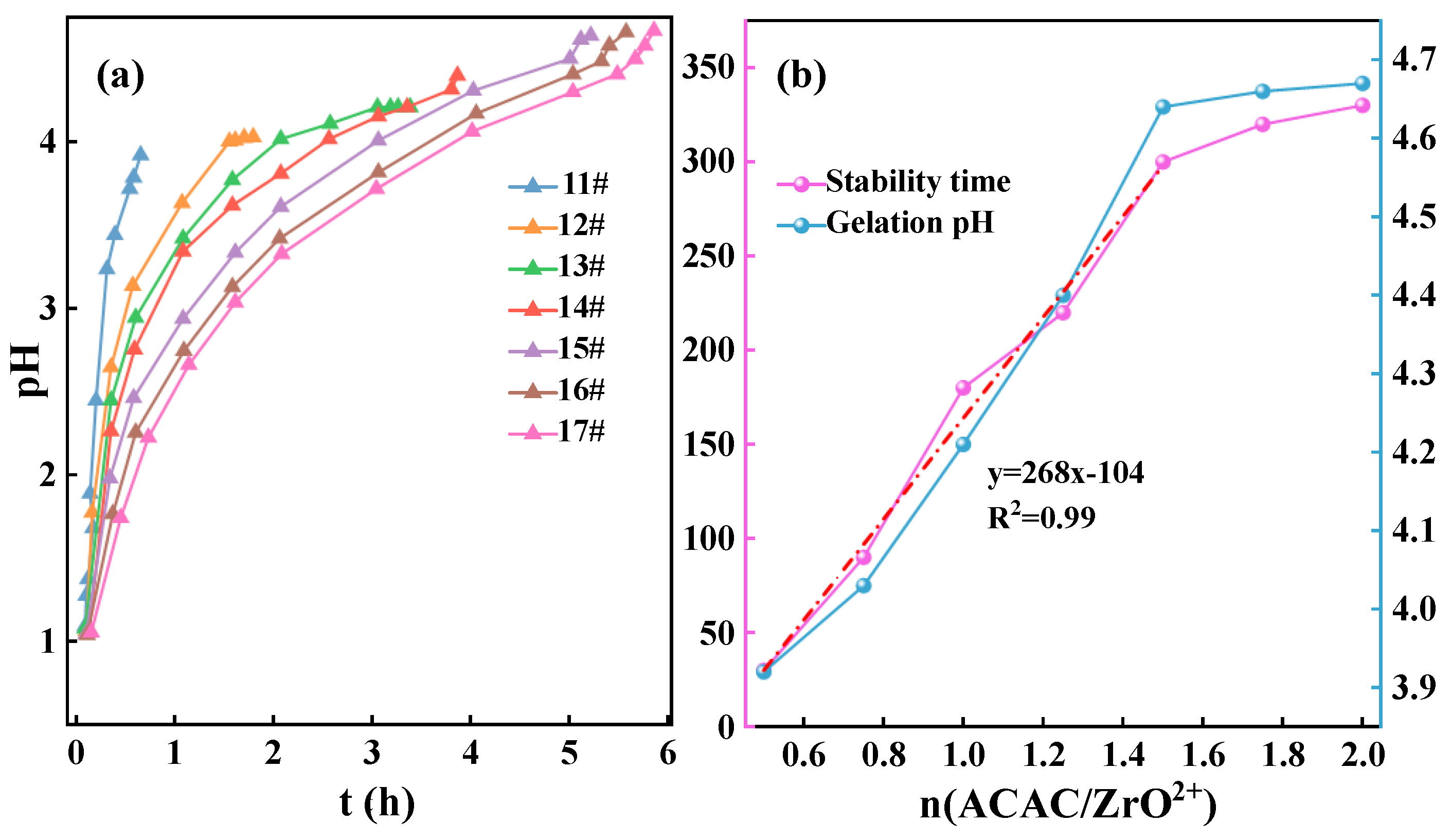

| 11# | 10 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 30 |

| 12# | 10 | 2 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 90 |

| 13# | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 180 |

| 14# | 10 | 2 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1 | 220 |

| 15# | 10 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 300 |

| 16# | 10 | 2 | 1.75 | 1.75 | 1 | 320 |

| 17# | 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 330 |

| Source of variation | Sum of squares (SS) | Degrees of freedom (df) | Mean square (MS) | Contribution (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACAC (A) | 30757 | 4 | 7689.25 | 46.00 |

| Glucose (B) | 21973 | 4 | 5493.25 | 32.80 |

| Interaction (A×B) | 14160 | 16 | 885.00 | 21.20 |

| Total | 66890 | 24 | 14067.50 | 100.00 |

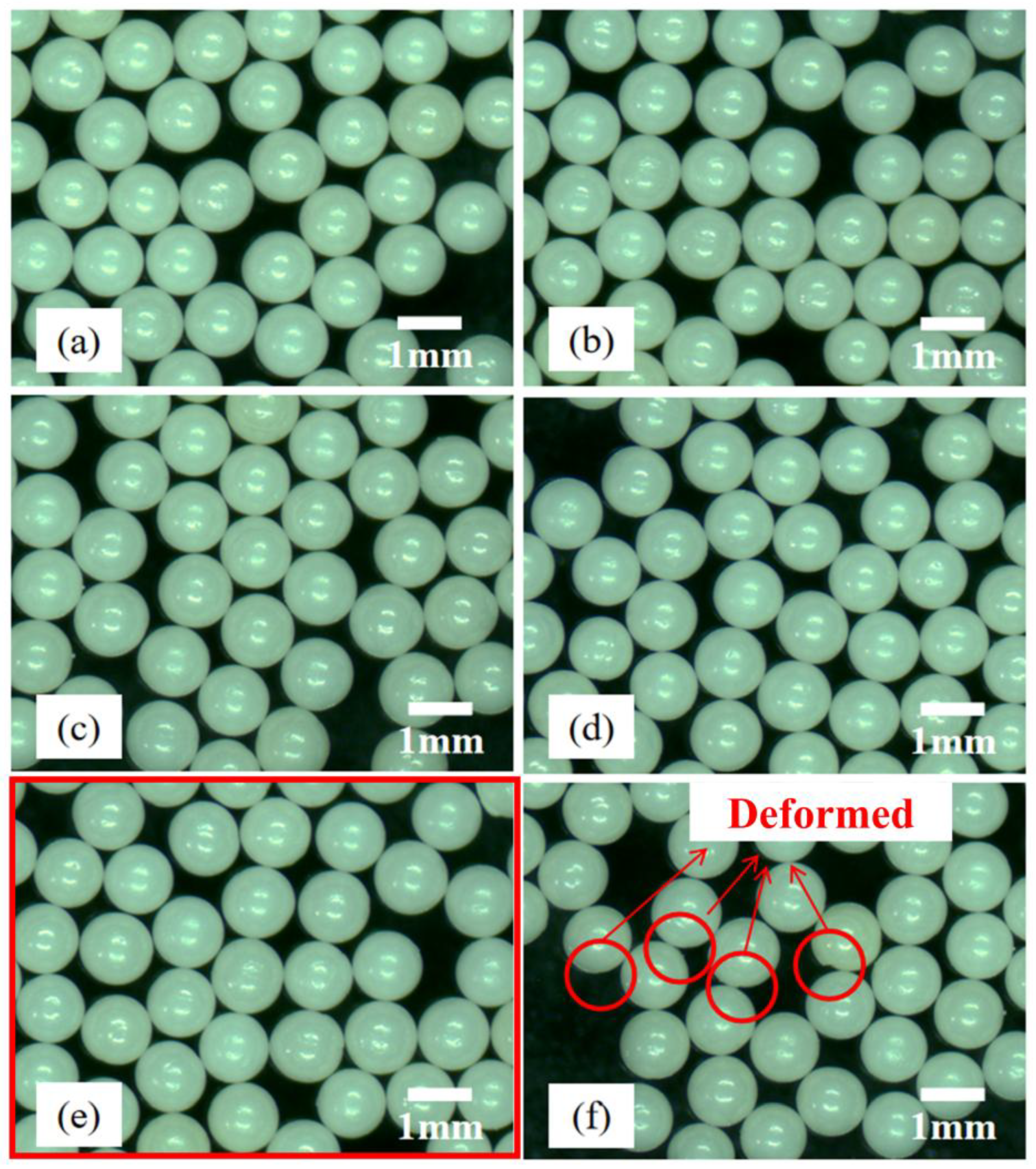

| Samples | n(ACAC/ZrO2+) | Gel microspheres | Sintered microspheres |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11# | 0.50 | good | good |

| 12# | 0.75 | good | good |

| 13# | 1.00 | good | good |

| 14# | 1.25 | good | good |

| 15# | 1.50 | good | good |

| 16# | 1.75 | Deformed microspheres | Deformed microspheres |

| 17# | 2.00 | No microspheres | ―― |

| Samples | Temperature of preparation | Density (g/cm3) | Sphericity | Crushing Strength (kg) | Size (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This work | 25℃ | 5.84 | 1.04±0.01 | 8.0 | 508±15 |

| Ref [6] | 25℃ | 5.87 | 1.02±0.01 | 3.0 | 608±6 |

| Ref [22] | 5℃ | 5.85 | 1.04±0.04 | 8.1 | 345±15 |

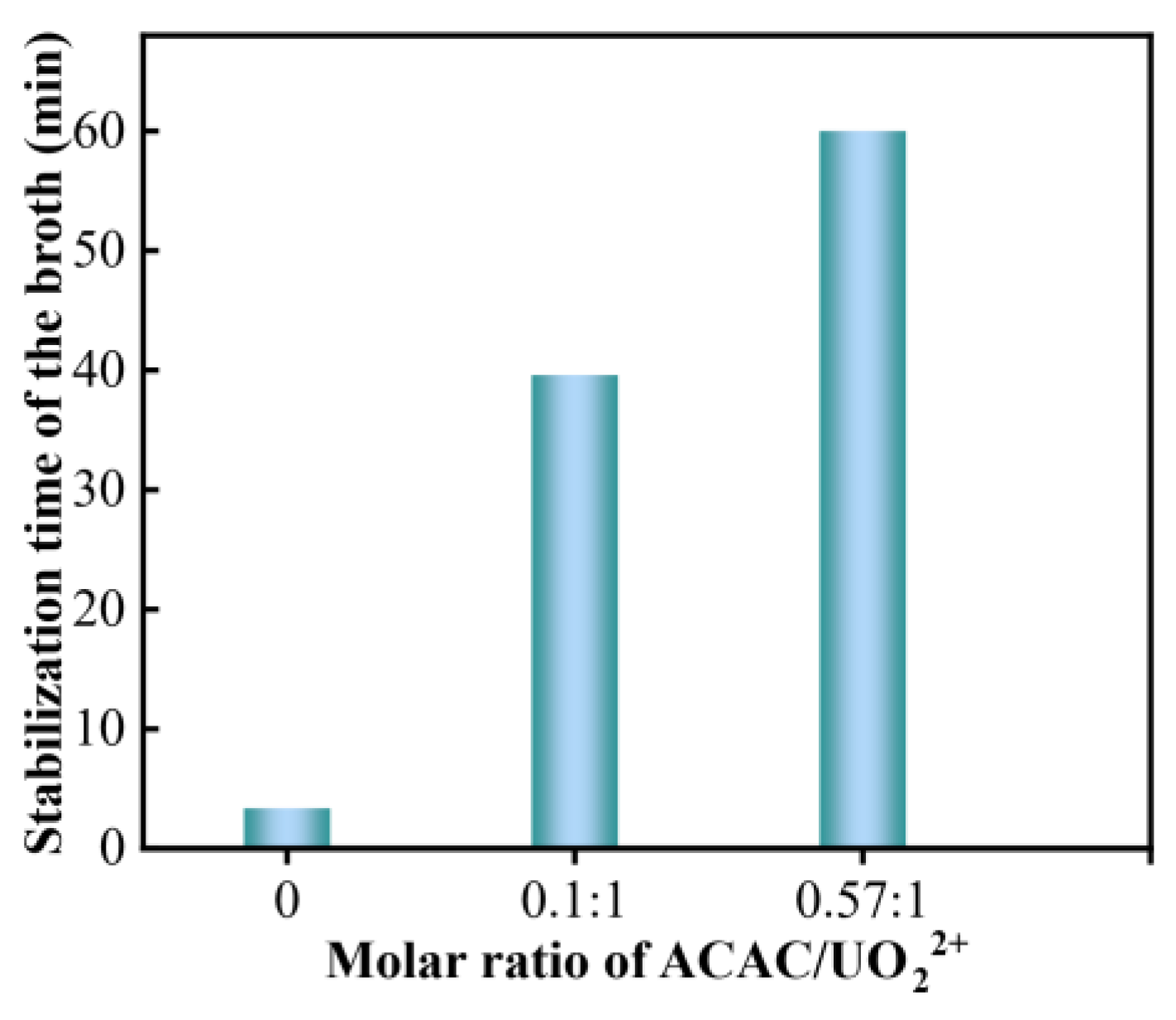

| Complexing agents | Stability time (min) | Formation of gel microspheres |

|---|---|---|

| Urea | 4 | Good |

| Glucose | Precipitation | —— |

| ACAC | 60 | Good |

| ACAC and glucose | 360 | Good |

| Citric acid | —— | No formation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).