1. Introduction

Coffee ranks as the second most valuable commodity in the world, after oil [

1]. Spent coffee grounds (SCG) constitute the most abundant waste produced by the coffee beverage industry and the production of instant coffee, accounting for approximately 45% of coffee waste [

2]. Compared to other organic waste, coffee residues contain high concentrations of harmful compounds that are detrimental to the environment, and most coffee waste is disposed of directly in landfills [

3]. Organic compounds in SCG, such as caffeine, tannins, and polyphenols, are particularly problematic for soil when this waste is disposed of [

4]. Additionally, disposing of SCG in landfills poses a significant risk of combustion, which can lead to excessive production of harmful methane and carbon dioxide, contributing to air pollution and environmental degradation [

2]. Besides the environmental issues, disposing of SCG in landfills is also economically disadvantageous. The high organic content in the waste requires a large amount of oxygen for efficient decomposition [

5]. However, SCG still contain significant amounts of sugars, oils, antioxidants, and other valuable compounds, making them a potential source of energy [

3]. The main components of SCG are cellulose and hemicellulose, which are found in the highest concentrations within the waste. Lignin and protein follow in lesser amounts, along with lipids, mainly fatty acids like linoleic acid and palmitic acid. Additionally, caffeine, phenolic compounds, minerals, tannins, and ash are present in smaller quantities [

6]. Coffee residues also have a high moisture content due to their composition, allowing them to retain significant amounts of water, with 5.7 grams of water per gram of dry SCG [

1]. Therefore, when combined with their high lignin and protein concentrations, SCG are a valuable resource for hydrothermal liquefaction [

7].

Due to the high moisture content in SCG, anaerobic digestion has been applied as a waste utilization technology for biogas production. Anaerobic digestion of coffee grounds produces approximately 0.314 L CH₄/g VS in biogas. However, adding coffee grounds to other waste for anaerobic co-digestion can have a competitive effect on methane yield [

8]. Additionally, the combustion of coffee grounds in a small-scale boiler has been tested. According to Kang et al. [

9] this combustion process can generate 6.5 kW of energy, which makes coffee grounds inefficient for combustion in larger-scale boilers. Another widely used process is the extraction of oils from SCG followed by their transesterification. However, due to the high acidity and water content of the oil, drying and pre-treatment stages, which incur significant energy costs, are necessary before the oil can be used [

10]. Given these characteristics, SCG have been utilized as a raw material for thermal technologies such as pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonization to manage waste and produce fuel [

11]. Regarding the pyrolysis of SCG, optimal results are achieved after the extraction of waste liquids. This process appears to have significant potential, but the raw material requires costly pre-drying and pre-processing. Low-temperature mild pyrolysis seems to be the most suitable method for converting SCG, yielding carbon products with significant calorific values ranging from 24 to 26 MJ/kg [

12]. Hydrothermal carbonization is a thermochemical process that occurs at temperatures between 180-250 °C, producing hydrochar, a solid fuel [

13]. According to Hu et al. [

14] experiments conducted with SCG at temperatures ranging from 150-230 °C achieved a remarkable maximum energy recovery of 83.93%. However, the calorific value reached a maximum of only 23.54 MJ/kg, which is relatively low compared to other methods.

Based on current energy needs, global energy demand is projected to increase by approximately 28% by 2040. The uncontrolled use of fossil fuels is exacerbating the energy crisis and environmental problems. This situation necessitates a shift towards renewable energy and the creation of a zero-carbon energy system [

15]. Hydrothermal liquefaction is a thermochemical process that converts organic waste into liquid fuel products, specifically bio-crude oil and high-value bioproducts. This process occurs at high temperatures ranging from 250 °C to 375 °C, with pressure conditions exceeding the water saturation point at these temperatures. The high temperature and pressure contribute to a short biomass conversion reaction time [

16] because they effectively break down the biomass structure to form oily products [

17]. During hydrothermal liquefaction, reactions such as depolymerization, bond breaking, rearrangement, and decarboxylation play key roles in breaking down the solid biomass structure into bio-crude oil [

18]. Compared to other thermochemical processes like combustion, gasification, and pyrolysis, hydrothermal liquefaction is more efficient because it does not require pre-drying of the biomass. Additionally, it can easily process complex biomass mixtures that contain lignocellulose, protein, and lipids [

19]. This technology can not only process and utilize the complex components of biomass but also has the ability to convert them entirely into biofuels [

18]. As a result, the abundant availability of organic waste makes it an attractive raw material for biofuel production. SCG, due to their structural characteristics and the vast consumption of coffee worldwide, constitute a significant amount of organic waste, making them an excellent source for biofuels [

19].

The use of hydrothermal liquefaction technology highlights a research gap in the full utilization of the moisture and components of SCG for the production of high-value biofuels and bioproducts, specifically bio-crude oil and hydrochar with high calorific value. The high temperature and pressure conditions in this process contribute to the high heating value of the solid fuel and the production of long-chain carboxylic acids, which enhance the liquid product of hydrothermal liquefaction. This study focuses on assessing the concentration of fatty acids and the heating value of hydrochar. Additionally, by analyzing the changes in organic load and the concentration of short-chain carboxylic acids (VFAs), the potential for biofuel production through the thermochemical pathways of hydrothermal liquefaction is examined. More specifically, the research focalizes on how thermochemical processes in hydrothermal liquefaction affect the production of VFAs and by increasing temperature and pressure the production of longer chain carboxylic acids.

2. Materials and Methods

The experiment was conducted on the island of Lesvos, using SCG as the material. The raw material was collected from the cafeteria of the University of the Aegean. As mentioned earlier, coffee consumption trends continue to rise steadily. Coffee-related industries worldwide produce vast quantities of SCG, which, in most cases, are wasted and not utilized [

20].

2.1. Experimental Process

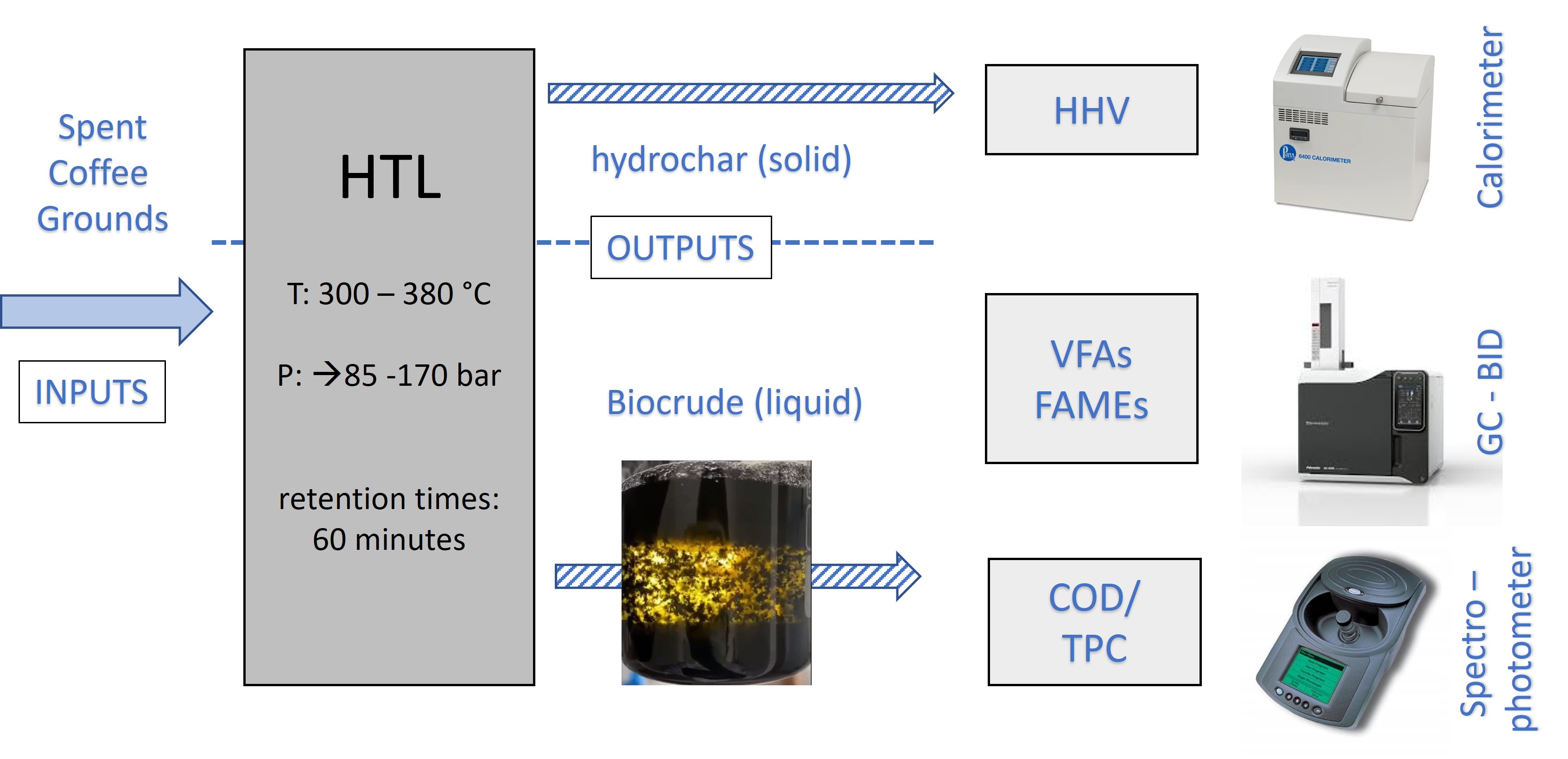

The experimental process began with the collection and analysis of SCG. The analyses performed on the material included total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS), and moisture determination. Specifically, 4 grams of SCG were placed in an oven at 105 °C for 24 hours to remove and calculate the moisture content in the waste, thereby determining the total solids. The material was then further heated at 550 °C for 3 hours to calculate the volatile solids. However, the analyses of the material were inconclusive for the next stage, which was hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL).

The hydrothermal liquefaction experiments were conducted in a Parr 4577A hydrothermal reactor with a capacity of 1 liter. A series of five experiments was carried out at different temperatures: 300 °C, 310 °C, 325 °C, 350 °C, and 380 °C. To regulate the moisture content of the material, which is crucial in hydrothermal treatment, the following quantities were placed in the reactor: for the first four temperatures, 60 grams of SCG and 140 ml of water were added, while at 380 °C, 20 grams of SCG and 40 ml of water were used. The different amounts of water in the experiments were aimed at controlling pressure at higher temperatures and maintaining pressure in the desired range of values. The residence time for the hydrothermal liquefaction experiments was 30 minutes.

Table 1 provides detailed conditions of the HTL experiments. After the process, the reactor was cooled, and the solid and liquid products were collected for further analysis.

2.2. Methods of Analysis

After the completion of hydrothermal liquefaction, several analyses were conducted on both the liquid and solid products. The liquid product was analyzed for pH, total phenols, Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), as well as the concentrations of Volatile Fatty Acids (VFAs) and Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs). The solid product, on the other hand, was separated from the liquid, filtered, and then assessed for hydrochar mass yield and high heating value.

The analyses began with the determination of pH, using a Consort C932 pH-meter, which was calibrated at pH 4 and 7 for greater accuracy [

21]. To calculate total phenols, the samples were initially mixed with water. The SCG300 and SCG350 samples were mixed 1/10, the sample SCG310 mixed 1/100, the SCG325 and SCG380 samples were mixed 1/200. The phenol analysis involved preparing a mixture containing 6 ml of water, 1 ml of diluted sample, 0.5 ml of phenol reagent, 1.5 ml of sodium carbonate, and 1 ml of water. This procedure was followed for all samples. The mixtures were then placed in a shaded area for two hours before measuring the phenol concentration using a Hach DR/2400 spectrophotometer [

21]. For COD measurement, the liquid phase of HTL samples were also mixed with water. In the SCG300, SCG350, and SCG380 samples, a mixture of 1/25 was performed, while in the SCG310 and SCG325 samples, a mixture of 1/30 was carried out. To measure COD concentration, a mixture was prepared containing 2.8 ml of silver sulfate, 1.2 ml of potassium dichromate, and 2 ml of the mixed sample. This procedure was repeated for all samples. The mixtures were then digested in a Hach 45600 COD reactor at 150 °C for 2 hours. After digestion, the COD concentration was measured using the Hach DR/2400 spectrophotometer, following the APHA [

22] methodology. It is worth noting that the mixtures in phenols and COD were different for their concentrations to be within the spectrum of the measurement of the curve in the spectrophotometer.

In the next stage of the analyses, the concentration of VFAs was measured. The process began by centrifuging the liquid for 10 minutes, followed by filtration. Equal amounts of isopropanol and the filtered sample were then mixed and placed in a sonic bath at 40 °C for 15 minutes to extract the VFAs using the organic solvent. The mixture was then centrifuged again for 10 minutes, after which the supernatant liquid, containing isopropanol and VFAs, was collected. This solution was introduced into a distillation column to evaporate the isopropanol, leaving only the VFAs. The resulting liquid was filtered using 0.45 µm filters. The efficiency of the extraction method was assessed using the CRM46975 Supelco Volatile Free Acid Mix as a standard, with the recovery efficiency estimated at 59.6 ± 0.2%. The concentration of VFAs was then measured using a gas chromatograph, specifically the Shimadzu Nexis 2030 GC-BID gas chromatograph with an Agilent J&W HP-FFAP column. The parameters of the method included a 1 μL sample injection volume, an injection temperature of 160 °C, an oven temperature program ranging from 80 °C to 230 °C, a flow rate of 59 ml/min, and a BID detector temperature of 280 °C.

The next phase of the analyses involved calculating the concentration of FAMEs. Transesterification was required to determine the FAMEs, and the process consisted of the following steps. Initially, 200 µL of the sample was mixed with 4 ml of a 0.5 M Methanolic-KOH solution. This mixture was heated to 80 °C for 15 minutes with two stirring stages. Then, 1.6 ml of an HCl (4:1) solution was added and the mixture was heated to 80 °C for 25 minutes. After heating, the mixture was cooled, and 8 ml of deionized water was added. Next, a total of 15 ml of hexane was introduced into the mixture to extract the FAMEs. The addition of hexane caused phase separation, and the supernatant, consisting of hexane and FAMEs, was collected. The liquid was then filtered using a 0.45 µm filter, with 2 grams of anhydrous sodium sulfate at the end of the syringe to absorb moisture. FAMEs were measured using the same gas chromatograph as VFAs. For the measurement method, the MEGA 10 column was used. Additional method parameters included a 1 μL sample injection volume, an injection temperature of 240 °C, an oven temperature program ranging from 40 °C to 230 °C, a flow rate of 66.5 ml/min, and a BID detector temperature of 240 °C. The final stage of the analyses involved measuring the high heating value of both the hydrochar produced at each temperature and the original material (SCG). The measurements were conducted using a Parr 6400 calorimeter. Before beginning the process, the calorimeter was calibrated with benzoic acid tablets. The high heating value for each temperature was then measured using a 0.3 g sample.

3. Results

The analyses carried out on the SCG revealed that it is a material with a high moisture content. According to Osorio-Arias et al. [

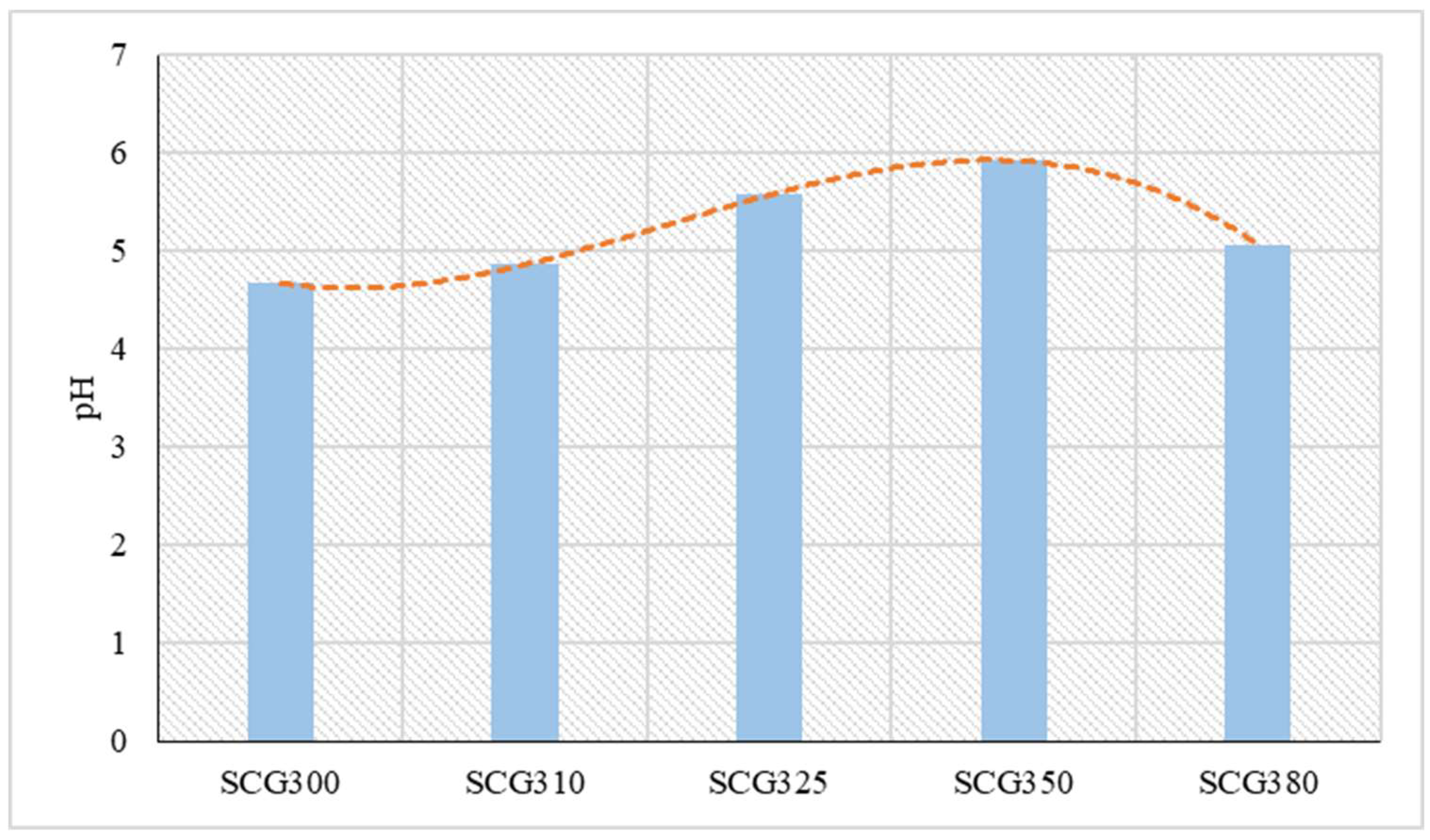

23], the moisture content of SCG typically fluctuates around 60%. In this study, the moisture content was found to be 62.7%, with total solids at 33.2% and volatile solids at 0.6%. The remaining percentage to reach 100% involved the percentage of solid carbon. On the other hand, pH measurements of the liquid products from hydrothermal liquefaction indicated that the pH values were acidic across all temperatures. This is likely because the material has a low ash content, approximately 1.3% [

24], and a low nitrogen content of 2.3%, including nitrogenous compounds [

25], which are factors that can contribute to an alkaline pH. The pH analysis results are presented in

Figure 1. The lowest pH value was observed in the liquid product from 300 °C (SCG300), which was 4.67. Almost the same pH value was derived from hydrothermal liquefaction SCG at 300 °C and was 4.8 according to the experiments of Yang et al. [

26]. As the temperature increased, the sample values remained acidic. In the liquid product from 380 °C (SCG380), there was a slight decrease in pH. The highest pH value was found in the SCG350 sample, reaching 5.92. Also, according to Muller et al. [

27], from their SCG hydrothermal liquefaction experiments there was a range in pH from 4.4-6.7.

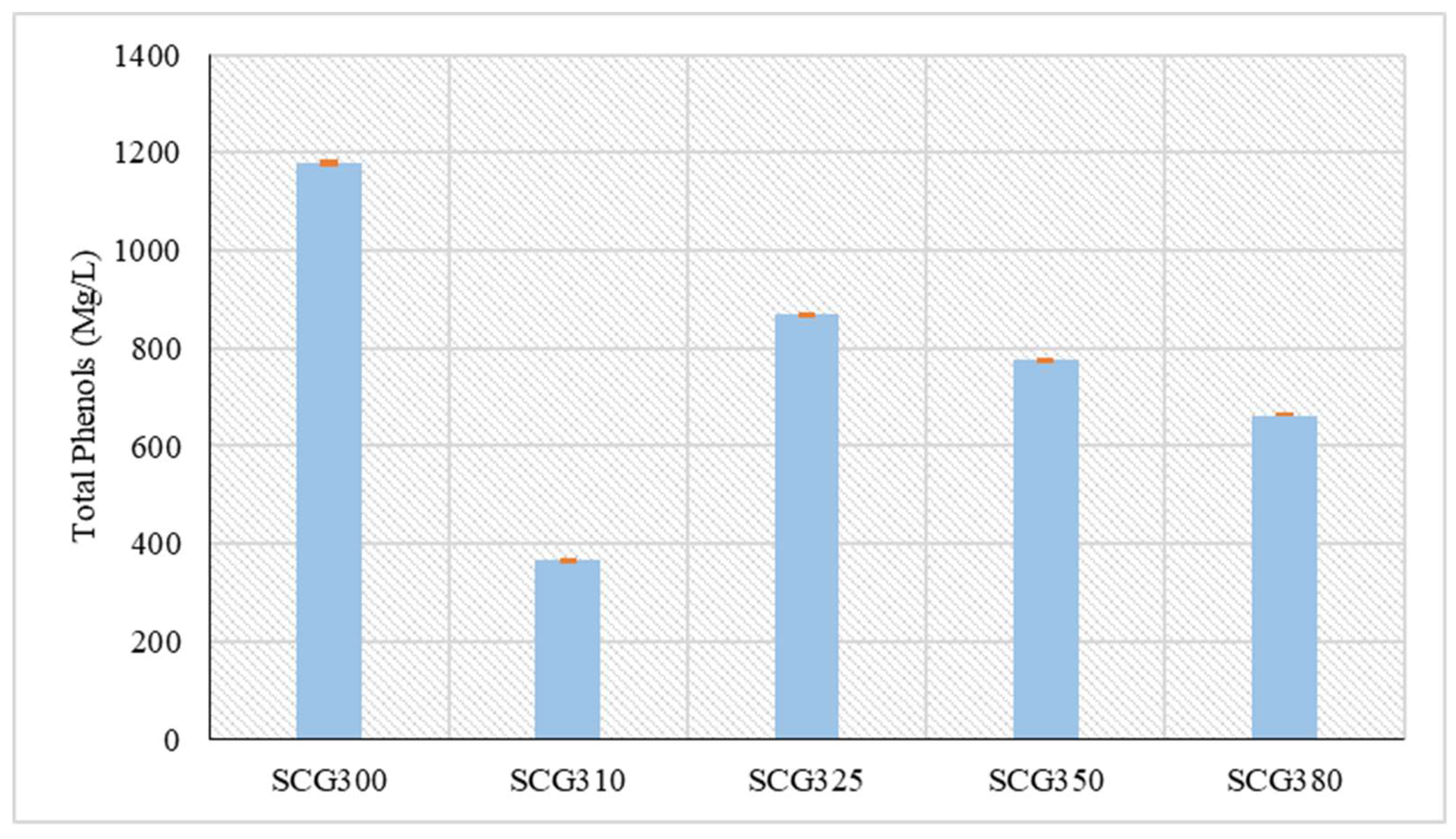

Regarding the total phenol concentration, the highest value was observed at 300 °C, measuring 1,180.2 mg/L. A sharp drop in concentration occurred at 310 °C, where the lowest phenol concentration of 365.5 mg/L was recorded, as shown in

Figure 2. In general, phenol concentrations in bio-crude oil produced from SCG are low due to the raw material's low lignin content [

4]. The lignin content in SCG is approximately 23.3% [

24]. After the sharp drop at 310 °C, a increase in phenol concentration was observed at 325 °C, reaching 870.4 mg/L, followed by a gradual decrease in concentration up to 380 °C. This increase in the concentration of phenols is due to the breaking down of the hydrochar, as well, organic components present in its pores were transferred to the liquid phase [

28]. This is because, the phenols form light cyclic hydrocarbons that remain in the biocrude, and heavier polycyclic hydrocarbons that form the biochar are trapped in it [

29]. On the other hand, this decline at higher temperatures occurs because high temperatures contribute to the destruction of phenols [

28]. From hydrothermal liquefaction of non-lignocellulosic biomass and more specifically sewage sludge at 350 °C and a residence time of 1 hour the concentration of phenols was reduced to 1,365 mg/l according to Liu et al. [

30]. Also, from hydrothermal liquefaction of wastewater in a similar temperature range from 290 °C to 350 °C for 30 minutes of residence time the concentration of phenols ranged from 1,500 mg/l to 2,300 mg/l and there was a decrease in temperature increase according to Basar et al. [

29]. On the other hand, hydrothermal liquefaction of microalgae Chlorella Kessleri at temperatures of 270 °C, 300 °C, 330 °C, 345 °C, while from 270 °C to 300 °C there was a decrease in the concentration of phenols from 90 mg/l to 63 mg/l at 330 °C there was an increase in value reaching 126 mg/l and at 345 °C it increased again to 208 mg/l according to Alimoradi et al. [

31].

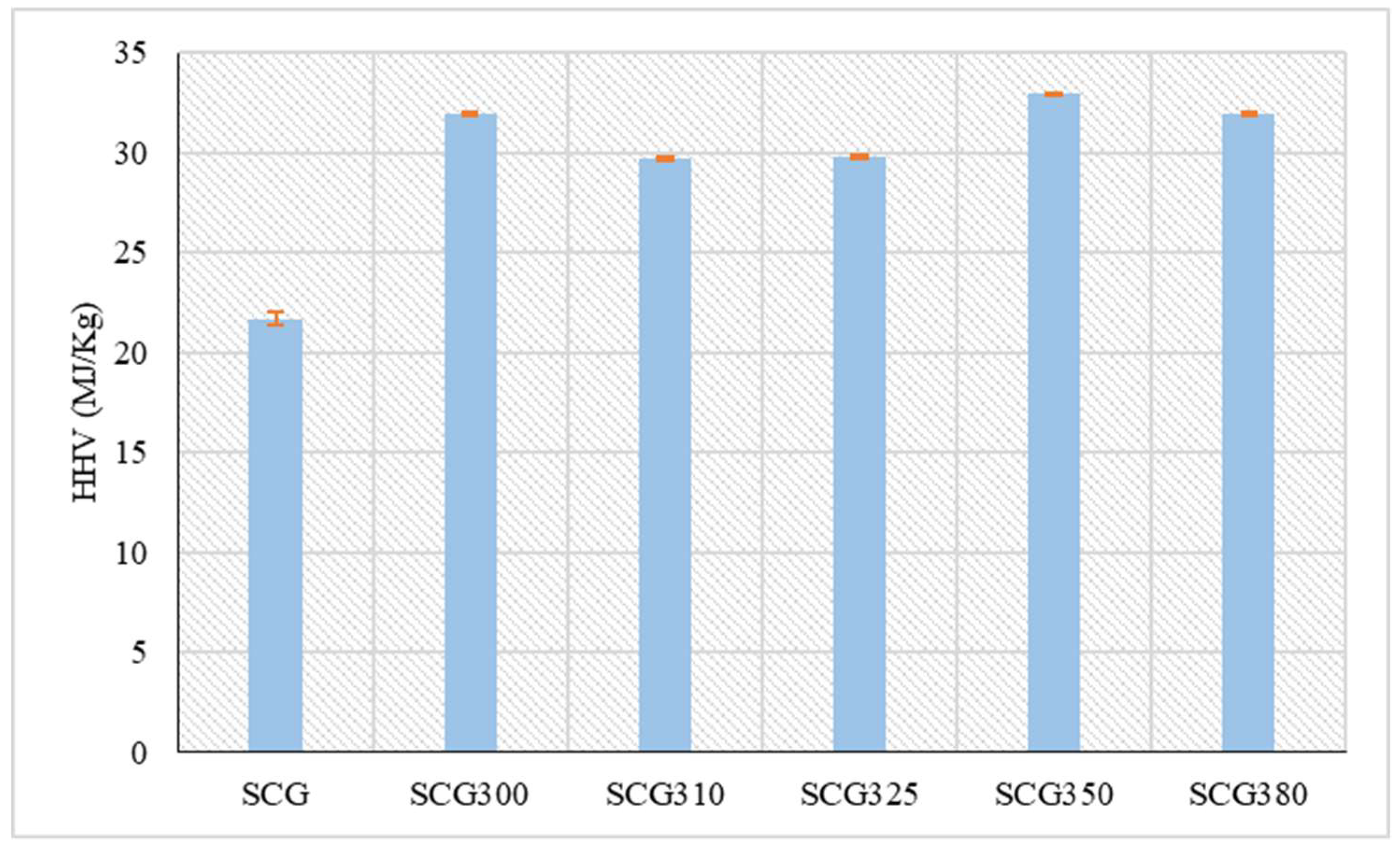

The calculation of the high heating value (HHV) revealed that its initial value in SCG increased through hydrothermal liquefaction, with the results presented in

Figure 3. The highest HHV was observed at 350 °C, reaching 32.9 MJ/kg, while the lowest HHV among the hydrothermal liquefaction samples was at 310 °C, measuring 29.7 MJ/kg. According to Yang et al. [

4], the HHV of SCG at 350 °C is 31.0 MJ/kg, noting that the product has a relatively low heating value due to its lower lignocellulose content compared to other biomass types. Initially, the HHV of SCG was estimated at 21.7 MJ/kg, which is slightly higher than the 19.0 MJ/kg measured by Caetano et al. [

32]. As for other biomass species in a similar temperature range, the HHV of hydrochar from corn cob at 310 °C is 26.6 MJ/kg, while at 370 °C it is 27.6 MJ/kg in a residence time of 1.5 hour [

33]. On the other hand, the hydrochar from olive tree at temperatures of 300 °C and 350 °C with a residence time of 1 hour amounts to 26.0 MJ/kg and 26.5 MJ/kg respectively [

34]. Similar values to those of hydrochar from SCG are observed in food waste with a moisture content of more than 70%. More specifically, hydrochar from food waste at 300 °C and a residence time of 1 hour presents a calorific value of 31.0 MJ/kg similar to that of hydrochar from the SCG300 sample [

35]. The fluctuation of the HHV of the solid and liquid HtL products has been discussed by Liakos et al. [

36] and has been attributed to the carboxylation reactions that take place in the range of 300 – 350 °C.

The mass yield of hydrochar as a percentage is presented in

Figure 4. It was observed to be 20% or lower at temperatures of 300 °C (20%), 310 °C (8%), and 325 °C (11%). At 350 °C, the hydrochar yield increased to 26%, followed by a slight decrease at 380 °C, where it reached 24%. Also, Saengsuriwong et al. [

37], showed similar rates., as through hydrothermal liquefaction food waste at temperatures of 280, 310, 340 the mass yields of the solid product ranged from 10% to 20% w/w. Still, from hydrothermal liquefaction of sewage sludge by Shah et al. [

38] at temperatures of 350 °C and 400 °C the mass yield of the solid ranged from 10-12%.

Measurements of the COD are presented in

Figure 5, showing an increase up to 310 °C. At this temperature, the highest COD concentration among all the samples was observed, reaching 28,012.2 mg/L. At the next temperature (325 °C), there was a slight decrease, with a concentration of 23,816.4 mg/L. According to Chen et al. [

39], biocrude oil from rice straw at 320 °C has a COD of 29,020 mg/L. At high temperatures, specifically from 300 °C and above, the COD is elevated because thermochemical processes, such as repolymerization reactions, occur, increasing the concentrations of organic compounds (e.g., ketones, amines, hydrocarbons). This enhances the yield of bio-crude oil and the organic load in the liquid phase [

40]. Subsequently, a sharp decrease in COD concentration (13,949.4 mg/L) was observed at 350 °C, likely due to an increase in hydrochar yield. This temperature also corresponded to the lowest COD concentration. Following this, there was a slight rise in concentration at 380 °C, reaching 17,382 mg/L. In comparison, with non-lignocellulosic biomass, the COD of sludge from hydrothermal liquefaction, specifically at 330 °C, showed a concentration ranging from 5,458 mg/l to 7,265 mg/l [

41]. Also, from other biomass species such as biocrude from hydrothermal liquefaction of sorghum bagasse at 300 °C and at 350 °C COD ranged from 20,000 mg/l to 26,000 mg/l [

42].

The measurements of volatile fatty acids (VFAs) are presented in

Figure 6. The VFAs produced included acetic acid, formic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, and isovaleric acid. The highest concentrations of VFAs were observed at 300 °C, with acetic acid at 541 mg/L, formic acid at 68 mg/L, propionic acid at 156 mg/L, and isovaleric acid at 41 mg/L standing out at this temperature. Subsequent temperatures showed a rapid decrease in VFA concentrations, except at 350 °C, where there was a slight increase in acetic acid and propionic acid, reaching 126 mg/L and 75 mg/L, respectively. Also, according to Basar et al., [

29] in the hydrothermal liquefaction of wastewater at temperatures from 290 °C to 350 °C a decrease in the concentration of VFAs to 325 °C was observed; there was a considerable increase in valeric acid. This increase may have occurred from the possible decomposition of a longer-chain volatile fatty acid at this temperature point [

29]. In this case, as well as, in the case of hydrochar breakdown, organic products released in the liquid phase and help in the secondary production of acetic acid and propionic acid, which at all temperatures embody the highest concentrations compared to other volatile fatty acids. The above are two cases that can explain the significant increase of the two VFAs. The reduced production of VFAs at higher temperatures is likely due to the formation of biocrude oil from SCG, which consists predominantly of long-chain carboxylic acids as the temperature increases [

4].

The determination of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs) concentrations, carried out via gas chromatography, revealed high concentrations, as presented in

Figure 7. A wide range of FAMEs production was observed, with concentrations increasing as the temperature rose. In particular, the highest concentrations were found for Methyl Butyrate, Methyl Hexanoate, Methyl Undecanoate, Methyl Palmitate, Methyl Stearate, Methyl Oleate (cis-9), and Methyl Linolenate. The highest concentrations were observed at temperatures of 325 °C, 350 °C, and 380 °C, with the last temperature standing out significantly. This indicates that as the temperature increases, the production of long-chain carboxylic acids also increases, consistent with findings from Yang et al. [

4], where biocrude oil from SCG at 275 °C primarily contained lighter fatty acids such as n-Hexadecanoic acid, Octadecanoic acid, 9-12 Octadecadienoic acid, and Octanoic acid. According to Caetano et al. [

32], the lipid content, which is directly related to fatty acids, is higher when the coffee grounds are dry. Also, according to Tang et al. [

42], in hydrothermal liquefaction experiments of microalgae Scenedesmus obliquus at temperatures of 290 °C, 305 °C, 320 °C, 335 °C and 350 °C showed that in the production of fatty acids the largest percentage was the fatty acids of C16-C18. More specifically, Hexadenoic acid, Palmitic acid, Octadecadienoic acid, Octadecenoic acid, Stearic acid, Eicosanoic acid. These fatty acids accounted for 80% of the total production of fatty acids. It was also observed that fatty acids formed at lower temperatures were retained in bio-crude oil at higher temperatures [

43].

5. Conclusions

Experiments on hydrothermal liquefaction were conducted using a Parr 4577a hydrothermal reactor at temperatures of 300 °C, 310 °C, 325 °C, 350 °C, and 380 °C. The material used was SCG, which have a high moisture content (63%). After the experiments, analyses were performed on the liquid and solid products of hydrothermal liquefaction. Parameters such as pH, total phenols, COD, volatile fatty acids (VFAs), FAMEs, mass yield of hydrochar, and the high heating value (HHV) of the solid product were measured. VFAs and FAMEs were analyzed using a Shimadzu Nexis 2030 plasma gas chromatograph with Agilent HP-FFAP and MEGA 10 columns, respectively. The pH of the samples was acidic, likely due to the high production of carboxylic acids. Phenols were present in low concentrations across all samples, with the highest value occurring at 300 °C (1,180.1 mg/L) and the lowest at 310 °C (365.6 mg/L). Phenol concentrations generally decreased as the temperature increased. COD showed an increase at the first three temperatures, followed by a decrease at 350 °C, likely due to the increased hydrochar yield at this temperature. The HHV peaked at 350 °C, reaching 32.9 MJ/kg. Additionally, VFAs were found in very low concentrations at all temperatures, with the highest concentrations observed at 300 °C. The VFAs produced included acetic acid, formic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, and isovaleric acid. The reduced production of VFAs coincided with the formation of long-chain carboxylic acids. It was observed that higher temperatures led to greater concentrations of FAMEs in the biocrude oil, with Methyl Butyrate, Methyl Hexanoate, Methyl Undecanoate, Methyl Palmitate, Methyl Stearate, Methyl Oleate (cis-9), and Methyl Linolenate having the highest concentrations. More specifically, by observing the production of VFAs and FAMEs it is realized that the increase in temperature and pressure conditions trigger more intense decarboxylation and carboxylation reactions, creating from short chain carboxylic acids to fatty acids.