1. Introduction

In 2024, the global propylene market size accounted for USD 112.02 billion and is anticipated to reach around USD 162.03 billion by 2034, with a 3.76% CAGR growth during the decade [

1]. Typically, cryogenic distillation is the most conventional method to purify light hydrocarbons (LHs) at an industrial level [

2]. Nevertheless, due to the very close molecular size and similar physical properties of C

3H

6 and C

3H

8 molecules (

Table 1), it is very challenging, extremely energy-intensive and economically demanding to exploit this method for this separation [

2,

3]. As an alternative, membrane-based technologies have recently provided promising results for various industrial gas separation processes, demonstrating high potential to greatly minimise the cost and energy demands compared to common methods [

4,

5].

Within recent decades, owing to possessing remarkable properties, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have gained attention as a leading class of porous materials for various gas adsorption and separation applications and for the development of functional membranes [

7]. MOF reticular chemistry allowed the prospective fabrication of porous materials with an elevated structural predictability [

8]. The rational selection of suitable metal ions and organic linkers enables the precise control of pore size and shape at the angstrom scale, provides different functionalities and active sites as nodes and edges and enhances the flexibility of the MOF scaffold. The synergic combination of these factors offers the potential to attain fine selective molecular exclusion for the equilibrium-based separation of molecules with almost identical physical properties, which is critical to many gas adsorption and separation applications. Given the complexity of propene/propane separation, the results obtained with MOF-based materials, including pristine MOF membranes [

9,

10,

11,

12], as well as MOF-based mixed-matrix membranes [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], are very promising. Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks are among the first MOFs investigated for propene/propane separation, particularly the prototypical ZIF-8 [

21,

22,

23], for which an ideal propene/propane selectivity of around 130 [

21] was predicted. This highly selective performance originates from the appropriate effective aperture size of ZIF-8, from 4.0 to 4.2 Å, lying between the kinetic diameters of propene and propane [

22]. Moreover, minor variations in the ZIFs’ metal nodes and ligands can result in substantial differences in their adsorption capacity, adsorption rate and molecular diffusion, further enhancing their separation performance [

20]. Additional investigations revealed that the replacement of Zn ions in ZIF-8 with Co ions, resulting in ZIF-67 [

24], clearly improves propene/propane separation, which was estimated to achieve the ideal selectivity of ~200 [

25]. Computational techniques assessed that the presence of Co(II) in ZIF-67 results in a tighter structure with reduced flexibility of the pore opening, due to the robust bonding of Co with the N atoms of the ligands, leading to a narrower aperture size (

Figure 1a) [

22,

23]. Computational studies also supported that enhanced gas separation properties can be obtained by replacing Zn

2+ in ZIF-8 with Co

2+ [

26], producing ZIF-67. ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 (

Figure 1a) have also shown promising propene/propane separation when combined with different polymers to fabricate mixed-matrix membranes (MMMs) [

12,

14,

15,

19,

26,

27]. For instance, a MMM prepared by using 20 wt.% ZIF-67 filler and 6FDA-DAM as polymer matrix showed a 2-fold increase in C

3H

6/ C

3H

8 selectivity compared to the ZIF-8 counterpart [

29].

Hybrid ZIFs with mixed metal centres and/or mixed linkers were prepared and investigated towards C

3H

6/C

3H

8 separation [

18], with CoZn-ZIF-8 inorganic membrane (Co/Zn ratio of 1) showing a separation factor of 120.2, with a remarkable 90% improvement compared to monometallic ZIF-8 (~63) and only a minor loss in C

3H

6 permeance (ca. 5%). Recently, ZIF-8-67 was used to fabricate 6FDA-DAM/ZIF-8-67 (70/30 w/w) MMM [

30], showing substantially improved C

3H

6 permeability by up to 240%, and moderate C

3H

6/C

3H

8 selectivity enhancement (70%) compared to the pristine 6FDA-DAM membrane. This superior performance of the bi-metallic CoZn-ZIF compared to its parent mono-metallic ZIFs was also reported towards other gas pairs such as CO

2/CH

4 [

31], CO

2/H

2 [

32], and CO

2/N

2 [

33]. On the other hand, the environmental concerns associated with organic solvents in the solvothermal synthesis of ZIFs, such as flammability, cost, and toxicity, highlight the urgent need for more eco-friendly yet efficient methods for their production. Recently, several studies have been conducted to synthesise ZIF-8 from aqueous solution, by hydrothermal synthesis or at room temperature [

34,

35,

36,

37], eventually with the addition of minimal amounts of a suitable additive or a non-ionic surfactant as structure directing agents in place of the organic solvent [

32,

39]. The structural tunability of ZIFs, combined with the limited number of studies on bimetallic-ZIF-8 for propene/propane separation, as well as the green synthesis approaches, makes it worth exploring the performances of these MOFs towards propene/propane separation when included in biopolymer-based MMMs, for further reducing the synthesis costs and the environmental impact.

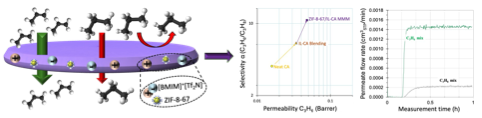

Here, as a complementary study of our previous work [

38], either monometallic (ZIF-8 and ZIF-67) and bimetallic (ZIF-8-67) ZIFs were successfully prepared by a green synthesis method and used to fabricate IL-CA blended MMMs in the form of thin film composites (TFCs). To the best of our knowledge, comprehensive single-gas and mixed-gas transport properties of this combination of materials, especially as TFCs with true scale-up potential, have not been studied before. Our findings demonstrate the superior separation performance of ZIF-8-67/MMM, which achieves the highest C

3H

6 permeability and C

3H

6/C

3H

8 selectivity, compared to its monometallic parents. These results further confirm the potential of ZIF-8-67-based MMMs as a promising material for efficient propene/propane separation and provide valuable insights into the design of high-performance and environmentally friendly membrane materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Cellulose acetate (CA), with a degree of substitution (DS) of 2.34 and Mw = 92.0 kg mol-1 [

38], was kindly provided by SNIA, Italy. Cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO

3)

2⋅6H

2O, 98%, Sigma-Aldrich), Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO

3)

2⋅6H

2O, 98%, Sigma-Aldrich), 2-methylimidazole (C

4H

6N

2, 99%, Sigma-Aldrich), and Triethanolamine (TEA) (98%, Merck) were employed for the synthesis of ZIF-8, ZIF-67 and ZIF-8/67 without furthur purification.

The solvents, including acetone (98%), n-hexane (99.5%), methanol (99%), ethanol (99%), and isopropanol (98%), were purchased from Merck. 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis (trifluoromethanesulfonyl) imide ([BMIM]+[Tf2N]-, C10H15F6N3O4S2), 98%, was supplied by Merck and Aldrich. Elastosil ® M4601 (for post-treatment of the membrane defects) was provided by Wacker Chemie AG (Munich, Germany). Membrane supports, PAN (Polyacrylonitrile) and PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene, Teflon), were supplied by Deltamem and Pall Corporation, respectively. To carry out the permeation tests, a series of gases, including N2, CH4, CO2, C3H6, and C3H8 (purity of +99.99%) were obtained from Sapio, Italy.

2.2. MOF Synthesis

ZIF-8, ZIF-67, and ZIF-8-67 were synthesised according to a green method [

39], using a metal: ligand: TEA molar ratio of 1:8:8, with a new method in washing procedures. To prepare ZIF-67 and ZIF-8, in the first step, Co(NO

3)

2.6H

2O (0.7170 g) and Zn(NO

3)

2.6H

2O (0.7361 g), respectively, were dissolved in 50 mL of deionised (DI) water after stirring for 20 mins. In the case of ZIF-8-67, a mixed Co/Zn ion solution was made by dissolving Co(NO

3)

2.6H

2O (0.7170 g) and Zn(NO

3)

2.6H

2O (0.7330 g) in the same quantity of DI water, following the same procedure as for ZIF-8 and ZIF-67. In the second synthetic step, similar for all the ZIFs, a solution by mixing 1.622 g of 2-methylimidazole (2-MeIm), 2.00 g of TEA, and 50 mL of DI water was prepared, and stirred for 20 minutes until a uniform solution was obtained. Following this, for each ZIF (ZIF-8, ZIF-67 and ZIF-8-67), the corresponding solution of salt (nitrate of Zn

2+, Co

2+ or Zn

2+/Co

2+) was added to the solution of 2-MeIm and TEA, which resulted in changing the colourless solution to white opaque suspensions, opaque purple, and opaque bluish purple, for ZIF-8, ZIF-67 and ZIF-8-67 suspensions, respectively. After a further 20 minutes of stirring, the mixtures were centrifuged (20 mins at 6000 rpm), and the supernatant was decanted. Then, the remaining solids were rewashed using a group of solvents (water, methanol, ethanol, isopropanol, and acetone) to gradually decrease the polarity of the solvent and achieve a more uniform and consistent mixture with the polymeric solution (CA in acetone). Finally, the ZIF nanoparticles were re-suspended in acetone and kept in a sealed jar for further usage, suspension I. To carry on the physical characterisation (PXRD, Porosimetry, FT-IR, ICP-MA, and SEM microanalysis), the ZIF’s suspension I was filtered on a filter paper before vacuum drying at 60 °C for 12 hours. The dried powders were then weighed and kept in sealed jars.

Scheme 1 schematically illustrates the synthesis.

2.2. Membrane Preparation

Two series of MMMs were prepared. First, the CA polymer powder was dried at 100 °C overnight and then dissolved in acetone to obtain a 10% wt. solution of CA (solution I). The solution was magnetically stirred until homogeneity was reached. For the first set of membranes, either the ZIF-8 or ZIF-67 suspensions (suspension I) were mixed with the CA solution to obtain a 20% wt. of ZIF/CA mixtures (mixture I). Afterwards, the obtained suspensions were stirred for 24 h and sonicated for 8 h to obtain uniform mixtures.

For the second series of MMMs, [BMIM]

+[Tf

2N]

- ionic liquid was added to the polymer solutions. Motivated by the results obtained with the 30% wt. [BMIM]

+[Tf

2N]

--CA free-standing blended-membrane [

38], the same IL with the same content was selected to form the second series of MMMs. Certain amounts of the IL were added dropwise to the solution I to achieve the 30% wt. content, followed by stirring at ambient temperature overnight to obtain solution II. The suspension of either ZIF-8, ZIF-67, or ZIF-8-67 (suspension I) was mixed with solution II to achieve 20% wt. of ZIF/IL-CA. Following the same procedure as for the first MMM series, homogeneous suspensions of ZIF/CA-IL were obtained (mixture II).

Scheme 2 illustrates this preparation.

All the prepared polymeric samples (solution I, solution II, mixture I, mixture II) were left for 2 h in the controlled-temperature chamber at 35 °C to degas before fabricating TFCs. A certain quantity of these samples was kept in a sealed jar to cast free-standing films to carry out the XRD and FT-IR analysis.

To fabricate the first group of TFCs, the spin-coating method was chosen. Here, to assess the effect of the support on the gas transport properties of the membranes, two different supports, PAN and PTFE, were selected. The first group of TFCs was fabricated by spin-coating at 1300 rpm solution I, mixture I, and mixture II (only ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 mixtures) on these two supports, with a homemade spin-coater. A disc of the support (either PAN or PTFE), with a diameter of 4.4 cm, was placed in the spin coater. Then, 1ml of pure acetone was dropped on the spinning support, immediately followed by dropping the same amount of the polymer/MOF solutions. Each support was coated twice (20s of spinning and 20s interval) with the corresponding mixture before placing it in the temperature-controlled chamber at 25 °C overnight.

The second group of TFCs were produced, employing the same procedure with solution I, solution II, and mixture II (all the ZIF mixtures) on only PAN support at 5000 rpm. The effect of coating speed was evaluated by comparing the gas transport properties of the TFCs coated on PAN. Additionally, to avoid eventual defects, two series of each single TFC were prepared, one being post-treated by covering with PDMS solution (20% wt. in n-Hexane) for successive gas permeation tests, the other one being kept uncovered for the SEM analysis. The schematic of this preparation is summarised in

Scheme 2, and

Table SI 1 provides the list of all fabricated MMMs and their chemical structure.

2.3. Physicochemical Characterizations

The crystallinity of the samples was evaluated with a powder diffractometer (Brucker, D2 PHASER 2nd generation, Germany) with Cu-Kα radiation, λ = 1.54056 Å. The active surface area and the average pore diameter of the synthesised ZIFs were characterised by BELSORP MINI X. The samples were activated at 473.15 K (200 °C) for 16 hours under reduced pressure, before carrying out the N2 adsorption−desorption isotherms and Brunauer-Emmett-Teller model (BET) analyses. Moreover, for SEM/XPS and ICP-MS analyses of the ZIFs, a SEM-HITACHI 4800 instrument and an Agilent 7900 ICP-MS were employed, respectively. For SEM characterization, the powder samples were mounted on electrically conductive carbon tape to ensure proper imaging and results. The ICP-MS analysis involved a preliminary microwave digestion of the powdered samples to prepare them for measurement, which was performed by the Microanalytical Service of the Universitat de València. FT-IR measurements were carried out using a Thermo Fisher iS50 FT-IR spectrometer with an ATR diamond (Thermo Scientific, USA). All spectra were obtained from 64 scans with a resolution of 4 cm−1, in the range of 400-4000 cm−1. All characterizations were performed twice. Finally, the morphology of the TFCs was characterized with Scanning Electron Microscopy analysis, SEM, using Phenom Pro X desktop SEM, Phenom-World. TFCs were delicately cut after keeping the samples in liquid N2, and then the images were acquired with an accelerating voltage of 15 kV at different magnifications.

2.4. Gas Transport Properties

2.4.1. Fixed-Volume Single-Gas Permeation Analyser

Single gas permeation tests were conducted using a fixed-volume pressure increase device, designed by HZG and constructed by Elektro & Elektronik Service Reuter in Geesthacht, Germany, as previously described [

40]. The tests were performed at a feed pressure of 1 bar and 25 °C, based on the time lag method. The membranes are equipped with an effective area of 13.84 cm2 and are fixed in a permeation module with two separate compartments (feed and permeate). Before exposing the membrane to a certain gas, the membrane is subjected to an evacuation of both sides of the membrane for a sufficiently long time to remove all previously absorbed species. Afterwards, from the feed side, the membrane is subjected to a series of gases, including N

2, CH

4, CO

2, C

3H

6, C

3H

8, and the pressure is recorded on the permeate side with constant volume. The details of the time lag method are discussed in SI3.1.

2.4.2. Mixed-Gas Permeation

Mixed gas permeation analysis was conducted by a constant pressure/variable volume system equipped with a quadrupole mass filter (HPR-20 QIC Benchtop residual gas analysis system, Hiden Analytical). The mass spectrometric gas analyser enables continuous monitoring of individual species present in the gas mixture. The measurements were carried out using a mixture of C

3H

6/C

3H

8 containing 50 vol% of each gas, with a feed flow rate of 50 cm

3STP min

−1 and using argon as the sweeping gas and internal standard for the gas analyser. Further details of the equipment were reported previously [

40,

41]. In SI3.2, the details of the applied method for determining permeability and diffusion coefficient (D) of the mixed gas permeation are discussed.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Structural Analysis of ZIFs and MMMs

3.1.1. ZIF’s Porosimetry Analysis

MOF surface area, pore size, and pore volume [

42] were determined by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) theory [

43]. The surface area and porosity characteristics of the synthesised ZIFs are available in

Figure SI 1 and Table SI 2. The N

2 sorption-desorption isotherms for ZIF-8, ZIF-67, and ZIF-8-67 followed the type I isotherm (

Figure SI 1a,c,e), indicating a microporous structure. In all ZIFs, the coexistence of micro- and mesoporosity in the bulk of the nanoparticles is confirmed by the first N

2 uptake at very low pressures and the second rise in uptake, respectively [

34]. Comparing the BET plots of the ZIFs (

Figure SI 1b,d,f), all the ZIFs show a linear region at

P/P0 = 0.05-0.3, confirming a uniform adsorption behaviour and a well-activated porous structure. The values of surface area, total pore volume, and average pore diameter for the synthesized ZIFs are also compared with those reported in the literature (

Table SI 2). It indicates noticeably higher BET surface area of this work’s ZIF-8 than what was achieved by the same method (976.5 and 620 m

2g

−1, respectively) [

39], comparable with what was synthesized via solvothermal methods, 962 m

2g

−1 [

34,

44]. Similarly, our ZIF-67 shows a higher surface area than that reported in literature for ZIF-67 prepared with the same synthesis protocol (1098 and 636 m

2g

−1, respectively) [

39], and slightly higher than the values reported for ZIF-67 prepared by employing higher amounts of TEA and water as solvent (1068 m

2g

−1) [

45]. This enhancement in active surface area could be attributed to the difference in the applied washing treatment, performed with a series of solvents, which can effectively eliminate pore-blocking residuals, as well as to the presence of both micro- and mesoporosity or the reduced particle size of the crystal particles.

Comparing ZIF-8 and ZIF-67, the active surface areas are comparable, with ZIF-67 nearly higher than that of ZIF-8 (1098 and 976.5 m

2g

−1, respectively), with a smaller average pore size (4.05 and 4.54 nm, respectively). This very subtle difference might be attributed to the higher electronegativity of the Co

2+ ion, which limits the flipping motion of 2-mIM organic ligands, thus resulting in a stiffer ZIF-67 structure, with a reduced effective aperture size [

25,

46]. In the case of ZIF-8-67, despite revealing a comparable active surface area with ZIF-8, the average pore diameter is significantly lower than that of its parent ZIFs, suggesting that the combination of Co

2+ and Zn

2+ ions could lead to a denser structure with smaller pore diameters in ZIF-8-67. Summarising the BET analysis, the microporous structures of the ZIFs and their high porosity are confirmed, making them good candidates, particularly for ZIF-8-67, to discriminate propene from propane through size-sieving.

3.1.2. MOF’s Structural Microanalysis

Figure SI 2a-c illustrates quantitative SEM microanalysis of the ZIFs, indicating both the kind and the percentage of the involved elements in the building units of each ZIF. As expected, ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 show the presence of single Zn

2+ and Co

2+ ions, respectively, along with other relevant components (C and N). Moreover, ZIF-8-67 features a similar contribution of Zn

2+ and Co

2+ ions (12.65 and 11.90 wt%, respectively), according to the 1:1 (50%-50%) ratio of these metals used in the synthesis. These results were confirmed by ICP-MS measurements (

Table SI 3), which illustrate the dominant presence of Zn

2+ and CO

2+ ions in ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 samples, respectively, as well as the balanced contribution of these ions in the ZIF-8-67 framework. These observations demonstrate the successful synthetic approach and appropriate compositions of these green ZIFs.

3.2. Crystallinity Identification of the MOFs and MMMs (X-Ray Diffractometer (XRD) Analysis)

Figure SI 3a,b shows the XRD spectra of the synthesised ZIF-8 and ZIF-67, respectively. Both spectra were comparable with the reported simulated ones [

47,

48], confirming the accuracy of the performed diffraction and the purity of the synthesised materials. The main characteristic peaks of ZIF-8 are observed at 2θ = 6.53°, 11°, 13°, 15.5°,17°,18.5°, 22.7°, and 25°, which agrees with the previous reports [

49,

50]. Both ZIF-67 and ZIF-8-67 powder diffraction patterns exhibit the major peaks at the same 2θ values as ZIF-8 (

Figure SI 3c), with a minor right-shift at 2θ = 8°, 11°, and 14° for ZIF-8-67 with respect to its monometallic counterparts (

Figure SI 3d).

Figure 2 shows the powder diffraction patterns of the polymeric membranes and ZIF-based MMMs. After adding 30% of [BMIM]

+[Tf

2N]

-, the semi-crystalline structure of the neat CA membrane turned into an almost amorphous one (

Figure 2a), as proved by the less intense and broadened peaks at 2θ = 8°, 18°, compared to the neat membrane. This phase transition was precisely discussed previously [

38].

Figure 2b-d confirms that the crystallinity of ZIF-8 and ZIF-8-67 is fully preserved when included in the bulk of the amorphous IL-CA matrix, while ZIF-67 features a slightly reduced degree of crystallinity, as proven by the less sharp peak observed in the diffraction pattern of the corresponding MMM, which suggests a minor affinity between Co-containing ZIF and polymer during membrane preparation.

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Analysis

Figure SI 4a illustrates the FT-IR spectrum of the neat CA membrane and the CA-IL blended membrane. CA (

Figure SI 4a, down) shows a distinctive FTIR peak at 1150 cm

−1, attributed to the C–O–C asymmetrical stretching, at 1700 cm–1 and 1650 cm

–1 for C=O symmetric and asymmetric stretching, respectively, and at 1300 cm

–1 for δ–CH bending vibrations, consistent with what was reported [

51]. After adding the IL, [BMIM]

+[Tf

2N]

-, new peaks in the range of 500-1500 cm

−1 appeared, with the main vibration of the S=O group (S=Os) at 1173 (

Figure SI 4a, top) [

52]. In addition, peaks in the regions 830–835 cm-1 and 750–755 cm–1 are attributed to the C-H bending modes of the imidazolium ring [

52].

Figure SI 4b shows the FTIR spectra of ZIF-8, ZIF-67, and ZIF-8-67, as pure powder, while

Figure SI 4c shows the spectra of ZIF/IL-CA MMMs. The typical fingerprints of this ZIF family are at 1580 cm

−1 (C=N stretch), and 1145 and 990 cm

−1 (C–N and C–H stretch) with a relevant peak at 426 cm

−1 related to Zn–N in ZIF-8, Co–N in ZIF-67, and Zn/Co–N in ZIF-8-67, in agreement with other studies [

39,

54]. The appearance of the new peaks in the ZIF/IL-CA spectra (

Figure SI 4c) confirms that the fillers ([BMIM]

+[Tf

2N]

- and ZIF NPs) have been successfully included into the MMMs structure, in line with XRD results.

3.4. Membranes’ Fabrication and Characterisation

One of the key elements in fabricating a selective and defect-free TFC is the selection of support, possessing an efficient porosity to both favour the permeation of the gases and prevent the penetration of the polymeric solution into the support during the coating process. The visual appearance of the TFCs, coated on PTFE at 1300 rpm and on PAN at 1300 and 5000 rpm, is shown in

Figure SI 5. Comparing the TFCs, both PAN and PTFE supports appear homogenously covered by the polymeric materials. However,

Figure SI 6, which shows the SEM images of the neat CA, ZIF/CA, and ZIF/IL-CA TFCs, coated at 1300 rpm, revealed that PAN support provides better compatibility with the neat CA than the PTFE. Microscopic observations indicated poor adhesion between the neat CA membrane and PTFE support and the existence of unselective interfacial gaps, while the corresponding membrane on PAN support adheres uniformly. This could originate from the hydrophilic nature of PAN and the possibilities of forming hydrogen bonds and polar interactions between PAN and CA

[55], which ensure good interfacial adhesion with minimum voids between the support and the membrane.

SEM images of neat CA, IL-CA blended membrane, and ZIF/IL-CA MMMs on PAN support at 5000 rpm are presented in

Figure 3. The membranes coated at higher speed show a smoother and more uniform layer on the support with lower polymer/filler interfacial gaps, compared to those fabricated at 1300 rpm (

Figure SI 6), particularly for ZIF/IL-CA MMMs. Moreover, the application of higher speed during the support coating resulted in TFCs with lower thickness, ranging from 2.5 to 3 µm, which is a key factor for enhancing the gas permeation, especially for big molecules such as propene and propane throughout low-permeable polymers like CA. Finally, coating at a sufficiently high speed regulates the solvent evaporation rate via convection heat transfer and enhances the uniformity of the membrane-coated layer on the support surface [

56,

57].

3.5. Gas Transport Studies

3.5.1. Single-Gas Permeation Properties of TFCs on PAN

3.5.1.1. CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 Pairs

In SI, we discussed how the preliminary permeability tests for the CO2/CH4 pair, in line with the SEM analysis, led to prioritising PAN support over PTFE for fabricating the TFCs. Here, the results of further investigations on the effect of spin coating speed and permselectivity analysis are provided.

Robeson-like plots in

Figure 4(a,b) compare the CO

2/CH

4 and CO

2/N

2 pairs permselectivity of the TFCs fabricated at 1300 and 5000 rpm and that of the free-standing film. The neat TFC@5000 rpm presented triple the CO

2 permeance of both the free-standing membrane and the TFC at 1300 rpm (1.14 GPU), with higher CO

2/CH

4 (35.3) and CO

2/N

2 (36.8), than the free-standing film, 31.3 and 30.3, respectively. This demonstrates the benefits of fabricating TFCs at higher speeds, which yields thinner TFCs with higher gas permeance, as well as the higher CO

2/CH

4 and CO

2/N

2 selectivity of both the TFCs, compared to the free-standing membrane.

Compared to the neat TFC@5000 rpm,

Figure 4(a,b), [BMIM]

+[Tf

2N]

--CA TFC showed a slight increase in CO

2 permeance but a decrease in CO

2/CH

4 and CO

2/N

2 ideal selectivity, reaching 27.4 and 29.6, respectively.

Figure 4(c,d) displays the solubility and diffusivity selectivity of CO

2/CH

4 and CO

2/N

2, calculated using the time lag method. It confirms that, for both pairs, the IL reduced diffusivity selectivity while having the opposite effect on solubility selectivities. This aligns with the expected plasticization effect of [BMIM]

+[Tf

2N]

-, as systematically studied in our previous study [

38].

Adding the ZIFs increased the CO

2 permeance, from 1.41 to 1.90, 2.30, and 2.15 for ZIF-8/, ZIF-67/, and ZIF-8-67/MMMs, respectively, accompanied by a plateau in the ideal CO

2/CH

4 selectivity (~28), except for the ZIF-8, compared to the CA-IL TFC (

Figure 4a,b). In terms of CO

2/N

2 selectivity, while the ZIF-8/MMM maintained the value of the IL-CA TFC, ~28, ZIF-67/ and ZIF-8-67/MMMs, by overcoming the trade-off obstacle, slightly increased the ideal selectivity to ~33.

Figure 4(c,d) shows that, in both pairs, compared to the IL-CA TFC, the ZIFs generally increased the diffusivity selectivities due to molecular sieve-like properties. On the other hand, they decreased the solubility selectivities (

Table SI 5). Overall, despite the enhancement in size-sieving separation of gases, provided by the ZIFs, the solubility-selectivity dominated the CO

2/CH

4 and CO

2/N

2 separation. This is due to the higher affinity of ZIFs towards absorbing CO

2 over CH

4 and N

2, enabling these MOFs to build both π- and σ-bonding with CO

2, particularly in ZIF-67 and ZIF-8-67 due to the valence electrons of Co

2+ (3d

7) [

58,

59]. The same findings are reported in other studies, such as ZIF-67/Pebax [

60], ZIF-67/6FDA-Durene [

61], and ZIF-8/Matrimid® [

62], bimetallic Zn/Co-ZIF/6FDA-ODA [

31].

3.5.1.2. C3H6/C3H8 Pair

Figure 5a displays an increased C3H6 permeance of the neat CA TFC@5000 rpm, which is 3 times and 4 times higher than that of the neat free-standing film and the neat TFC@1300 rpm. Moreover, compared to the free-standing film, the neat TFC@5000 rpm showed a slight increase in C

3H

6/C

3H

8 selectivity from 3.5 to 3.9, which is comparable to the performance of the TFC@1300 rpm. The IL-CA TFC@5000 rpm increased the C

3H

6 permeance of the neat CA TFC from 0.015 to 0.021 GPU, along with a rise in C

3H

6/C3H

8 ideal selectivity from ~4 to ~5. While the plasticization effect of [BMIM]

+[Tf

2N]

- is a cause of higher C

3 gases permeance, achieving higher ideal C

3H

6/C

3H

8 selectivity could be related to the higher affinity of this IL to absorb propene over propane [

38]. This hypothesis is confirmed by increasing the solubility selectivity but decreasing the diffusivity selectivity in IL-CA TFC compared to the neat CA TFC, depicted in

Figure 5b and

Table SI 5.

The incorporation of ZIFs further increased the propene permeance in the MMM TFCs, noticeably higher for the ZIF-8/MMM (0.17 GPU), along with a rise in the C

3H

6/C

3H

8 ideal selectivity to almost 2x, 2.5x, and 3x of the neat CA TFC (3.5) when using ZIF-8, ZIF-67, and ZIF-8-67, respectively (

Figure 5a). The changes in the solubility and diffusivity selectivities (

Figure 5b) demonstrate that the increase in the permeance of propene and the ideal C

3H

6/C

3H

8 selectivity in ZIF-67/ and ZIF-8-67/MMMs originates from the increase in the diffusivity difference of these gases rather than the solubility difference, while for ZIF-8/MMM both the solubility and diffusivity differences drove the separation.

3.5.2. Propene/Propane Mixture Separation

The first challenge in the separation of propene/propane mixtures was the correct quantitative analysis of both gases. Since fragmentation of propane also produces propene, all further fragmentation causes complete overlap of the propene signals by propane signals and therefore propene did not have any unique signals (

Figure SI 7). Instead, propane has a unique signal at m/z = 29 amu, corresponding to the ethyl+ fragment, which is also the most intense signal in the mass spectrum of propane. The largest peak of propene is the signal at m/z = 41 amu, but in the permeation experiment, it leaves the net signal of propene in the mixture, as follows:

The propene concentration is then calculated by the procedure described in the experimental section. Overall, propane is usually the minor component in the mixture after permeation, combined with its relatively small signal at m/z = 42 amu, its presence does not affect the accuracy of the propene determination, and thus the mixture composition can be determined reliably. To avoid signal overlap with the molecular ion tail of argon (m/z = 40), which serves as the sweeping gas, argon was monitored respecting the 36Ar isotope at m/z = 36 amu, allowing for all signals to be analysed within a consistent range of partial pressure using the Secondary Electron Multiplier ion detector.

The highest C3 selectivity of ZIF-8-67/IL-CA TFC and its reasonable propene permeance led to the selection of this TFC for further mixed-gas analysis. The permeation curves of pure propene and propane and their 50/50 vol% mixture are given in

Figure 6a and

Figure 6b, respectively. For a qualitative comparison, the scale of the mixture mode is expanded twice. The pure propene flow rate is approximately 8 times higher than that of propane, which confirms a high selectivity for the olefin species. A similar trend is observed for the gas mixture, but with a higher flow rate of propane and a lower propene flow rate, causing the lower mixed gas selectivity than the ideal selectivity. This difference stems from the bulk effect caused by the high permeance of C

3H

6 in both the polymer and ZIF-8-67 cavities, facilitating the faster transport of larger gas molecules (C

3H

8) via carrier-mediated movement by smaller gas molecules (C

3H

6), thereby reducing separation factors under mixed-gas conditions [

16]. A similar behaviour was observed in the permeability of propene and propane through ZIF-8/PIM-6FDA-OH MMMs, attributed to the differences in the sorption of C

3H

6 and C3H8 within both the polymer matrix and the molecular sieve, as well as the comparable condensability of C

3H

6 and C

3H

8, which induces strong negative sorption coupling effects between these gases [

16].

Interestingly, while the diffusion of light gases is too fast to observe a measurable time lag, a clear transient phenomenon is observable for propane and propene. Analogous to the traditional time lag curves in the fixed-volume setup for single gases, the S-shaped curve, due to the sensibly lower diffusion coefficient of the hydrocarbons than that of the light gases, can be used to evaluate the diffusion coefficient from the inflection point in the curve or from the time at half height [

66,

67]. The normalised flow rate, which highlights the differences between the individual gases, shows a much slower transient for propane than for propene, both in the single gases mode (

Figure 7a) and in the mixture mode (

Figure 7b). The diffusion coefficient of propene is much higher than that of propane due to its smaller effective diameter [

68]. Direct comparison of the pure and mixed propene (

Figure 7c) and propane (

Figure 7d) shows that there is virtually no difference between the two propene curves, whereas propane is clearly much faster than the mixture in pure gas. This suggests a higher diffusion coefficient, which is thus at least in part responsible for the higher mixed gas permeability of propane. The quantitative data are listed in

Table SI 6. Since the precise membrane thickness is not accurately known, the absolute value of the diffusion coefficient cannot be determined, but the diffusion selectivity can still be determined from the ratio of the two-time lags, showing an increased diffusion selectivity from 5.6 to 8.6 (

Table SI 6).

4. Conclusions and Outlook

This study comprehensively analyses MMMs consisting of 20% wt. aqueous-based ZIFs (ZIF-8, ZIF-67, ZIF-8-67), in 30%[BMIM]+[Tf2N]--CA blending, towards gas separation. The physical characteristics of ZIFs via BET analysis, XRD, SEM microanalysis, MS-ICP, and FT-IR revealed their highly crystalline and microporous structure, the successful approach of the ZIFs aqueous-based synthesis, and the balanced presence of Zn²⁺ and Co²⁺ ions in ZIF-8-67, distinguishing it from its monometallic counterparts. The systematic investigation of TFC membranes fabricated at different coating speeds revealed key insights into their gas separation performance:

The transport properties of MMM TFCs on PAN and PTFE prioritised PAN support over the PTFE.

Higher coating speeds led to forming thinner selective layers and enhanced gas diffusion, benefiting CO2 and C3H6 separations.

The presence of [[BMIM]+[Tf2N]-, enhanced the ZIFs and CA compatibility, facilitated CO2 and C3H6 permeation and increased C3H6/C3H8 ideal selectivity, while CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 separation showed a trade-off behaviour.

The contribution of ZIFs further enhanced CO2 and C3H6 permeances, with ZIF-8-67 and ZIF-67 presenting the highest CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 ideal selectivities. In C3H6/C3H8 separation, ZIF-8-67 exhibited the best ideal selectivity.

Mixed-gas separation experiments also confirmed a high selectivity for propene over propane via the ZIF-8-67/IL-CA TFC, demonstrating the practical relevance of this membrane.

Overall, this study highlights the significant role of bimetallic ZIF-8-67 in enhancing gas separation performance when incorporated into IL-CA membranes. The synergistic properties of Zn²⁺ and Co²⁺ in ZIF-8-67 and its small pore diameter, combined with the role of [BMIM]+[Tf2N]- in reducing interfacial defects, contributed to its superior gas size-sieving effect and selectivity. These findings provide valuable insights for the development of advanced membranes for efficient propene/propane separation, paving the way for a scalable membrane that can be used at an industrial level.

The present work, committed to sustainable separation strategies, suggests using BioMOFs and green bio-based ionic liquids for developing a new generation of sustainable MMM TFCs, which will be the subject of future work.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Pegah Hajivand: Writing – original draft, data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Mariagiulia Longo: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Marcello Monteleone: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Teresa Fina Mastropietro: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Javier Navarro-Alapont: Investigation. Alessio Fuoco; Funding acquisition. Elisa Esposito: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualisation, Investigation, Resources, Funding acquisition. Donatella Armentano: Writing – review & editing, supervision, Funding acquisition, conceptualisation, Supplies, ZIFs synthesis. Johannes Carolus Jansen: Funding acquisition, Resources, Conceptualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Supervision.

Funding

Part of the research leading to these results has received funding from the “European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101115488, project DAM4CO2”. Elisa Esposito acknowledges funding from the “Bilateral Programme 2024-2025 “Thin-film composite Membranes against Climate Change for gas stream treatment and CO2 separation (EMC2). “The Cariplo Foundation (MOCA project, grant n. 2019-2090)” is gratefully acknowledged for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Bidwai, S.; Shivarkar, A. Propylene Market Size, Share, and Trends 2024 to 2034.

- Eldridge, R.B. Olefin/Paraffin Separation Technology: A Review. Ind Eng Chem Res 1993, 32, 2208–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulijn, J.A.; Makkee, M.; Van Diepen, A.E. Chemical Process Technology; John Wiley & Sons, 2013; ISBN ISBN 1118570758. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J.; Liu, P.; Jiang, M.; Yu, L.; Li, L.; Tang, Z. Olefin/Paraffin Separation through Membranes: From Mechanisms to Critical Materials. J Mater Chem A Mater 2019, 7, 23489–23511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.L.; Koros, W.J. Defining the Challenges for C3H6/C3H8 Separation Using Polymeric Membranes. J Memb Sci 2003, 211, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-R.; Kuppler, R.J.; Zhou, H.-C. Selective Gas Adsorption and Separation in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem Soc Rev 2009, 38, 1477–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuppler, R.J.; Timmons, D.J.; Fang, Q.-R.; Li, J.-R.; Makal, T.A.; Young, M.D.; Yuan, D.; Zhao, D.; Zhuang, W.; Zhou, H.-C. Potential Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Coord Chem Rev 2009, 253, 3042–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Alezi, D.; Eddaoudi, M. A Reticular Chemistry Guide for the Design of Periodic Solids. Nat Rev Mater 2021, 6, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamia, N.; Jorge, M.; Granato, M.A.; Paz, F.A.A.; Chevreau, H.; Rodrigues, A.E. Adsorption of Propane, Propylene and Isobutane on a Metal–Organic Framework: Molecular Simulation and Experiment. Chem Eng Sci 2009, 64, 3246–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuttke, S.; Bazin, P.; Vimont, A.; Serre, C.; Seo, Y.; Hwang, Y.K.; Chang, J.; Férey, G.; Daturi, M. Discovering the Active Sites for C3 Separation in MIL-100 (Fe) by Using Operando IR Spectroscopy. Chemistry–A European Journal 2012, 18, 11959–11967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Alnemrat, S.; Yu, L.; Vasiliev, I.; Ren, Q.; Lu, X.; Deng, S. Adsorption of Ethane, Ethylene, Propane, and Propylene on a Magnesium-Based Metal–Organic Framework. Langmuir 2011, 27, 13554–13562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, E.D.; Queen, W.L.; Krishna, R.; Zadrozny, J.M.; Brown, C.M.; Long, J.R. Hydrocarbon Separations in a Metal-Organic Framework with Open Iron (II) Coordination Sites. Science (1979) 2012, 335, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, C.; Xiang, L.; Xu, Y.; Pan, Y. Enhanced C3H6/C3H8 Separation Performance in Poly (Vinyl Acetate) Membrane Blended with ZIF-8 Nanocrystals. Chem Eng Sci 2018, 179, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xiang, L.; Chang, H.; Chen, K.; Wang, C.; Pan, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Z. Rational Matching between MOFs and Polymers in Mixed Matrix Membranes for Propylene/Propane Separation. Chem Eng Sci 2019, 204, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dai, Y.; Johnson, J.R.; Karvan, O.; Koros, W.J. High Performance ZIF-8/6FDA-DAM Mixed Matrix Membrane for Propylene/Propane Separations. J Memb Sci 2012, 389, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Swaidan, R.J.; Wang, Y.; Hsiung, C.; Han, Y.; Pinnau, I. Highly Compatible Hydroxyl-Functionalized Microporous Polyimide-ZIF-8 Mixed Matrix Membranes for Energy Efficient Propylene/Propane Separation. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2018, 1, 3541–3547. [Google Scholar]

- Japip, S.; Wang, H.; Xiao, Y.; Chung, T.S. Highly Permeable Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework (ZIF)-71 Nano-Particles Enhanced Polyimide Membranes for Gas Separation. J Memb Sci 2014, 467, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, F.; Zimmerman, J.M.; Paek, S.-M.; Hamid, M.R.A.; Lim, W.T.; Jeong, H.-K. Rapid Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Hybrid Zeolitic–Imidazolate Frameworks with Mixed Metals and Mixed Linkers. J Mater Chem A Mater 2017, 5, 6090–6099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Kwon, H.T.; Jeong, H.K. High-Flux Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework Membranes for Propylene/Propane Separation by Postsynthetic Linker Exchange. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2018, 57, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.; Chung, T.-S. Natural Gas Purification and Olefin/Paraffin Separation Using Thermal Cross-Linkable Co-Polyimide/ZIF-8 Mixed Matrix Membranes. J Memb Sci 2013, 444, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, U.; Barth, B.; Paula, C.; Kuhnt, A.; Schwieger, W.; Mundstock, A.; Caro, J.; Hartmann, M. Ethene/Ethane and Propene/Propane Separation via the Olefin and Paraffin Selective Metal–Organic Framework Adsorbents CPO-27 and ZIF-8. Langmuir 2013, 29, 8592–8600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Lively, R.P.; Zhang, K.; Johnson, J.R.; Karvan, O.; Koros, W.J. Unexpected Molecular Sieving Properties of Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8. J Phys Chem Lett 2012, 3, 2130–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Olson, D.H.; Seidel, J.; Emge, T.J.; Gong, H.; Zeng, H.; Li, J. Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks for Kinetic Separation of Propane and Propene. J Am Chem Soc 2009, 131, 10368–10369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Rong, Z.; Nguyen, H.L.; Yaghi, O.M. Structural Chemistry of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. Inorg Chem 2023, 62, 20861–20873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokidas, P.; Castier, M.; Moncho, S.; Sredojevic, D.N.; Brothers, E.N.; Kwon, H.T.; Jeong, H.-K.; Lee, J.S.; Economou, I.G. ZIF-67 Framework: A Promising New Candidate for Propylene/Propane Separation. Experimental Data and Molecular Simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2016, 120, 8116–8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokidas, P.; Castier, M.; Economou, I.G. Computational Study of ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 Performance for Separation of Gas Mixtures. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2017, 121, 17999–18011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez, M.J.C.; Balkus, K.J., Jr.; Ferraris, J.P.; Musselman, I.H. Molecular Sieving Realized with ZIF-8/Matrimid® Mixed-Matrix Membranes. J Memb Sci 2010, 361, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.A.; Vaughn, J.T.; Brunelli, N.A.; Koros, W.J.; Jones, C.W.; Nair, S. Mixed-Linker Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework Mixed-Matrix Membranes for Aggressive CO2 Separation from Natural Gas. Microporous and mesoporous materials 2014, 192, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Park, S.; Kwon, H.T.; Jeong, H.-K.; Lee, J.S. A New Superior Competitor for Exceptional Propylene/Propane Separations: ZIF-67 Containing Mixed Matrix Membranes. J Memb Sci 2017, 526, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.W.; Cho, K.Y.; Kan, M.-Y.; Yu, H.J.; Kang, D.-Y.; Lee, J.S. High-Flux Mixed Matrix Membranes Containing Bimetallic Zeolitic Imidazole Framework-8 for C3H6/C3H8 Separation. J Memb Sci 2020, 596, 117735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loloei, M.; Kaliaguine, S.; Rodrigue, D. CO2-Selective Mixed Matrix Membranes of Bimetallic Zn/Co-ZIF vs. ZIF-8 and ZIF-67. Sep Purif Technol 2022, 296, 121391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Rai, R.K.; Tyagi, D.; Yao, X.; Li, P.-Z.; Yang, X.-C.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Q.; Singh, S.K. Room-Temperature Synthesis of Bimetallic Co–Zn Based Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks in Water for Enhanced CO 2 and H 2 Uptakes. J Mater Chem A Mater 2016, 4, 14932–14938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, L.; Liu, N.; Xu, J.; Zhou, J. Using Lantern Zn/Co-ZIF Nanoparticles to Provide Channels for CO2 Permeation through PEO-Based MMMs. J Memb Sci 2020, 597, 117644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Zhao, L.; Lai, Z. Rapid Synthesis of Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 (ZIF-8) Nanocrystals in an Aqueous System. Chemical Communications 2011, 47, 2071–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butova, V.V.; Budnyk, A.P.; Bulanova, E.A.; Lamberti, C.; Soldatov, A. V Hydrothermal Synthesis of High Surface Area ZIF-8 with Minimal Use of TEA. Solid State Sci 2017, 69, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, K.; Okita, M.; Fujita, K.; Tanaka, S.; Miyake, Y. Formation of High Crystalline ZIF-8 in an Aqueous Solution. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 1794–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Yao, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, K.; Chen, F.; Wang, H. Facile Synthesis of Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 from a Concentrated Aqueous Solution. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2014, 184, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajivand, P.; Longo, M.; Mastropietro, T.F.; Godbert, N.; Monteleone, M.; Bezzu, C.G.; Armentano, D.; Jansen, J.C. Tailoring the Thermal, Mechanical, and Gas Transport Properties of Cellulose Acetate Membranes with Ionic Liquids for Efficient Propene/Propane Separation. Polymer (Guildf) 2025, 128679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.F.; Sherman, E.; Vajo, J.J. Aqueous Room Temperature Synthesis of Cobalt and Zinc Sodalite Zeolitic Imidizolate Frameworks. Dalton transactions 2012, 41, 5458–5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, S.C.; Monteleone, M.; Lanč, M.; Esposito, E.; Fuoco, A.; Giorno, L.; Pilnáček, K.; Friess, K.; Carta, M.; McKeown, N.B. A Novel Time Lag Method for the Analysis of Mixed Gas Diffusion in Polymeric Membranes by On-Line Mass Spectrometry: Method Development and Validation. J Memb Sci 2018, 561, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, M.; Esposito, E.; Fuoco, A.; Lanč, M.; Pilnáček, K.; Friess, K.; Bezzu, C.; Carta, M.; McKeown, N.; Jansen, J.C. A Novel Time Lag Method for the Analysis of Mixed Gas Diffusion in Polymeric Membranes by On-Line Mass Spectrometry: Pressure Dependence of Transport Parameters. Membranes (Basel) 2018, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonwane, C.G.; Bhatia, S.K. Characterization of Pore Size Distributions of Mesoporous Materials from Adsorption Isotherms. J Phys Chem B 2000, 104, 9099–9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J Am Chem Soc 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravillon, J.; Münzer, S.; Lohmeier, S.-J.; Feldhoff, A.; Huber, K.; Wiebcke, M. Rapid Room-Temperature Synthesis and Characterization of Nanocrystals of a Prototypical Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework. Chemistry of Materials 2009, 21, 1410–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.-H.; Lee, Y.-T.; Peng, C.-H. Synthesis and Characterization of Hybrid Metal Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework Membrane for Efficient H2/CO2 Gas Separation. Materials 2020, 13, 5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.T.; Jeong, H.-K.; Lee, A.S.; An, H.S.; Lee, J.S. Heteroepitaxially Grown Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework Membranes with Unprecedented Propylene/Propane Separation Performances. J Am Chem Soc 2015, 137, 12304–12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chang, H.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Shen, K.; Yi, H.; Zhang, J. Synthesis and Adsorption Performance of La@ ZIF-8 Composite Metal–Organic Frameworks. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 3380–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Xing, T.; Lou, Y.; Chen, J. Controlling ZIF-67 Crystals Formation through Various Cobalt Sources in Aqueous Solution. J Solid State Chem 2016, 235, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Phan, A.; Wang, B.; Knobler, C.; Furukawa, H.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. High-Throughput Synthesis of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks and Application to CO2 Capture. Science (1979) 2008, 319, 939–943. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.S.; Ni, Z.; Côté, A.P.; Choi, J.Y.; Huang, R.; Uribe-Romo, F.J.; Chae, H.K.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Exceptional Chemical and Thermal Stability of Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 10186–10191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.; Shanti, R.; Morris, E. Characterization of Conducting Cellulose Acetate Based Polymer Electrolytes Doped with “Green” Ionic Mixture. Carbohydr Polym 2013, 91, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa, T.; Okafuji, A.; Kato, T.; Ohno, H. Induction of an Infinite Periodic Minimal Surface by Endowing An Amphiphilic Zwitterion with Halogen-Bond Ability. ChemistryOpen 2016, 5, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Mizuno, M. Characteristic Spectroscopic Features Because of Cation–Anion Interactions Observed in the 700–950 Cm–1 Range of Infrared Spectroscopy for Various Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 8027–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Li, M.; Hou, L. Influence of the 2-Methylimidazole/Zinc Nitrate Hexahydrate Molar Ratio on the Synthesis of Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 Crystals at Room Temperature. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 9597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yang, H.; Wang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Yan, J.; Cheng, W.; Rojas, O.J.; Han, G. Composite Membranes of Polyacrylonitrile Cross-Linked with Cellulose Nanocrystals for Emulsion Separation and Regeneration. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2023, 164, 107300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmann, P.; Zornoza, B.; Téllez, C.; Coronas, J. Mixed Matrix Membranes Comprising MOFs and Porous Silicate Fillers Prepared via Spin Coating for Gas Separation. Chem Eng Sci 2014, 107, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomekian, A.; Behbahani, R.M.; Mohammadi, T.; Kargari, A. High Speed Spin Coating in Fabrication of Pebax 1657 Based Mixed Matrix Membrane Filled with Ultra-Porous ZIF-8 Particles for CO 2/CH 4 Separation. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 2017, 34, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frentzel-Beyme, L.; Kloß, M.; Pallach, R.; Salamon, S.; Moldenhauer, H.; Landers, J.; Wende, H.; Debus, J.; Henke, S. Porous Purple Glass–a Cobalt Imidazolate Glass with Accessible Porosity from a Meltable Cobalt Imidazolate Framework. J Mater Chem A Mater 2019, 7, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, S.; Wharmby, M.T.; Kieslich, G.; Hante, I.; Schneemann, A.; Wu, Y.; Daisenberger, D.; Cheetham, A.K. Pore Closure in Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks under Mechanical Pressure. Chem Sci 2018, 9, 1654–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Bu, M.; Pang, J.; Fan, W.; Fan, L.; Zhao, H.; Yang, G.; Guo, H.; Kong, G.; Sun, H. Hydrothermal Stable ZIF-67 Nanosheets via Morphology Regulation Strategy to Construct Mixed-Matrix Membrane for Gas Separation. J Memb Sci 2020, 593, 117404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Ni, L.; Zhang, H.; Xie, J.; Yan, X.; Chen, S.; Qi, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, X.; Li, J. Veiled Metal Organic Frameworks Nanofillers for Mixed Matrix Membranes with Enhanced CO2/CH4 Separation Performance. Sep Purif Technol 2021, 279, 119707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Nataraj, S.K.; Roussenova, M.V.; Tan, J.C.; Hughes, D.J.; Li, W.; Bourgoin, P.; Alam, M.A.; Cheetham, A.K.; Al-Muhtaseb, S.A. Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework (ZIF-8) Based Polymer Nanocomposite Membranes for Gas Separation. Energy Environ Sci 2012, 5, 8359–8369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Koros, W.J. Significance of Entropic Selectivity for Advanced Gas Separation Membranes. Ind Eng Chem Res 1996, 35, 1231–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viciano-Chumillas, M.; Liu, X.; Leyva-Pérez, A.; Armentano, D.; Ferrando-Soria, J.; Pardo, E. Mixed Component Metal-Organic Frameworks: Heterogeneity and Complexity at the Service of Application Performances. Coord Chem Rev 2022, 451, 214273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Chaemchuen, S.; Koo-amornpattana, W.; Qiao, A.; Bu, T.; Verpoort, F.; Wang, J.; Mu, S. Insights into Multivariate Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks. Chemical Synthesis 2025, 5, N-A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, I.N.; Syrtsova, D.A.; Shalygin, M.G.; Kandasamy, P.; Teplyakov, V.V. Transmembrane Gas Transfer: Mathematics of Diffusion and Experimental Practice. J Memb Sci 2020, 601, 117737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, M.; Fuoco, A.; Esposito, E.; Rose, I.; Chen, J.; Comesaña-Gándara, B.; Bezzu, C.G.; Carta, M.; McKeown, N.B.; Shalygin, M.G. Advanced Methods for Analysis of Mixed Gas Diffusion in Polymeric Membranes. J Memb Sci 2022, 648, 120356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplyakov, V.; Meares, P. Correlation Aspects of the Selective Gas Permeabilities of Polymeric Materials and Membranes. Gas Separation & Purification 1990, 4, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(a) Basic tetrahedral unit of ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 frameworks and (b) Aperture leading to the cage of ZIF-8-67. The N–Zn/Co–N angle flexibility governs the aperture size response in the model. (Reprinted with permission from [

25]. Copyright © 2016, American Chemical Society.).

Figure 1.

(a) Basic tetrahedral unit of ZIF-8 and ZIF-67 frameworks and (b) Aperture leading to the cage of ZIF-8-67. The N–Zn/Co–N angle flexibility governs the aperture size response in the model. (Reprinted with permission from [

25]. Copyright © 2016, American Chemical Society.).

Scheme 1.

Schematic of the green synthesis of the ZIFs’ NPs.

Scheme 1.

Schematic of the green synthesis of the ZIFs’ NPs.

Scheme 2.

Schematic of the MMMs preparation.

Scheme 2.

Schematic of the MMMs preparation.

Figure 2.

The XRD spectrum of A) neat CA and IL/CA blended-membrane, and its comparison with the MMMs contained B) ZIF-8, C) ZIF-67, D) ZIF-8-67.

Figure 2.

The XRD spectrum of A) neat CA and IL/CA blended-membrane, and its comparison with the MMMs contained B) ZIF-8, C) ZIF-67, D) ZIF-8-67.

Figure 3.

The SEM images of MMM TFCs made at 5000 rpm on PAN. A) neat CA, B) IL-CA, C) ZIF-8/IL-CA, D) ZIF-67/IL-CA, and E) ZIF-8-67/IL-CA.

Figure 3.

The SEM images of MMM TFCs made at 5000 rpm on PAN. A) neat CA, B) IL-CA, C) ZIF-8/IL-CA, D) ZIF-67/IL-CA, and E) ZIF-8-67/IL-CA.

Figure 4.

Robeson plots of MMM TFCs@ 5000 rpm on PAN, including A) CO2/CH4 and B) CO2/N2. Gas transport data of neat membrane were shown by circles (●) and orange triangle used for IL-CA TFC@5000 rpm (▲). Squares stand for ZIF/IL-CA TFCs@5000 rpm (■), (blue for ZIF-8, green for ZIF-67, and purple for ZIF-8-67). C)The diffusivity selectivity of CO2/CH4 (left panel) and CO2/N2 (right panel), and D) The solubility selectivity of CO2/CH4 (left panel) and CO2/N2 (right panel) diffusion selectivity. Yellow column for neat CA, orange for IL-CA, blue for ZIF-8/IL-CA, green for ZIF-67/IL-CA, and purple for ZIF-8-67/IL-CA.

Figure 4.

Robeson plots of MMM TFCs@ 5000 rpm on PAN, including A) CO2/CH4 and B) CO2/N2. Gas transport data of neat membrane were shown by circles (●) and orange triangle used for IL-CA TFC@5000 rpm (▲). Squares stand for ZIF/IL-CA TFCs@5000 rpm (■), (blue for ZIF-8, green for ZIF-67, and purple for ZIF-8-67). C)The diffusivity selectivity of CO2/CH4 (left panel) and CO2/N2 (right panel), and D) The solubility selectivity of CO2/CH4 (left panel) and CO2/N2 (right panel) diffusion selectivity. Yellow column for neat CA, orange for IL-CA, blue for ZIF-8/IL-CA, green for ZIF-67/IL-CA, and purple for ZIF-8-67/IL-CA.

Figure 5.

A) Robeson plot for C3H6/C3H8 of CA-based MMMs with 30% content of the [BMIM] [Tf2N] and 20% ZIF-8, ZIF-67, and ZIF-8-67 on PAN, test area:13.84 cm2. Gas transport data of neat membrane were shown by circles (●) and orange triangle used for IL-CA TFC@5000 rpm (▲). Squares stand for ZIF/IL-CA TFCs@5000 rpm (■), (blue for ZIF-8, purple for ZIF-8-67, and green for ZIF-67). B) The solubility selectivity (left panel) and diffusivity selectivity (right panel) of C3H6/C3H8. Yellow column for neat CA, orange for IL-CA, blue for ZIF-8/IL-CA, green for ZIF-67/IL-CA, and purple for ZIF-8-67/IL-CA.

Figure 5.

A) Robeson plot for C3H6/C3H8 of CA-based MMMs with 30% content of the [BMIM] [Tf2N] and 20% ZIF-8, ZIF-67, and ZIF-8-67 on PAN, test area:13.84 cm2. Gas transport data of neat membrane were shown by circles (●) and orange triangle used for IL-CA TFC@5000 rpm (▲). Squares stand for ZIF/IL-CA TFCs@5000 rpm (■), (blue for ZIF-8, purple for ZIF-8-67, and green for ZIF-67). B) The solubility selectivity (left panel) and diffusivity selectivity (right panel) of C3H6/C3H8. Yellow column for neat CA, orange for IL-CA, blue for ZIF-8/IL-CA, green for ZIF-67/IL-CA, and purple for ZIF-8-67/IL-CA.

Figure 6.

Propene and Propane flow rate for pure gases (A) and as a 50/50 vol% mixture of propene and propane (B). The dashed vertical lines represent the start of the experiment, when the membrane is exposed to the gas.

Figure 6.

Propene and Propane flow rate for pure gases (A) and as a 50/50 vol% mixture of propene and propane (B). The dashed vertical lines represent the start of the experiment, when the membrane is exposed to the gas.

Figure 7.

Normalized flow rates for pure gases (a) and mixtures (b), highlighting the large difference in diffusion coefficient of propene and propane. Comparison of the normalized pure and mixed gas flow rate of propene (c) and propane (d), highlighting the virtually identical trends of the pure and mixed gases, with in both cases faster diffusion of the mixed gas species. The x-axis is shown from the start of the experiment, when the membrane is exposed to the gas.

Figure 7.

Normalized flow rates for pure gases (a) and mixtures (b), highlighting the large difference in diffusion coefficient of propene and propane. Comparison of the normalized pure and mixed gas flow rate of propene (c) and propane (d), highlighting the virtually identical trends of the pure and mixed gases, with in both cases faster diffusion of the mixed gas species. The x-axis is shown from the start of the experiment, when the membrane is exposed to the gas.

Table 1.

The physical properties of propene and propane [

7].

Table 1.

The physical properties of propene and propane [

7].

| |

C3H6 |

C3H8

|

| Molecular Formula |

|

|

| Molecular Weight (g/mol)

|

42.08 |

44.1 |

| Normal boiling point (°C) |

-47.69 |

-42.13 |

| Kinetic diameter (nm) |

0.45 |

0.43 |

| Polarizability ×[10-25 cm3] |

62.6 |

62.9–63.7 |

| Dipole moment ×[1018 /(esu∙cm2)] |

0.366 |

0.084 |

| Critical Temperature (°C) |

91.75 |

96.74 |

| Critical Pressure (Bar) |

45.55 |

42.51 |

| Vapor Pressure (Bar at (°C)) |

9.17 (21.1) |

8.41 (21.1) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).