Submitted:

14 July 2024

Posted:

15 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

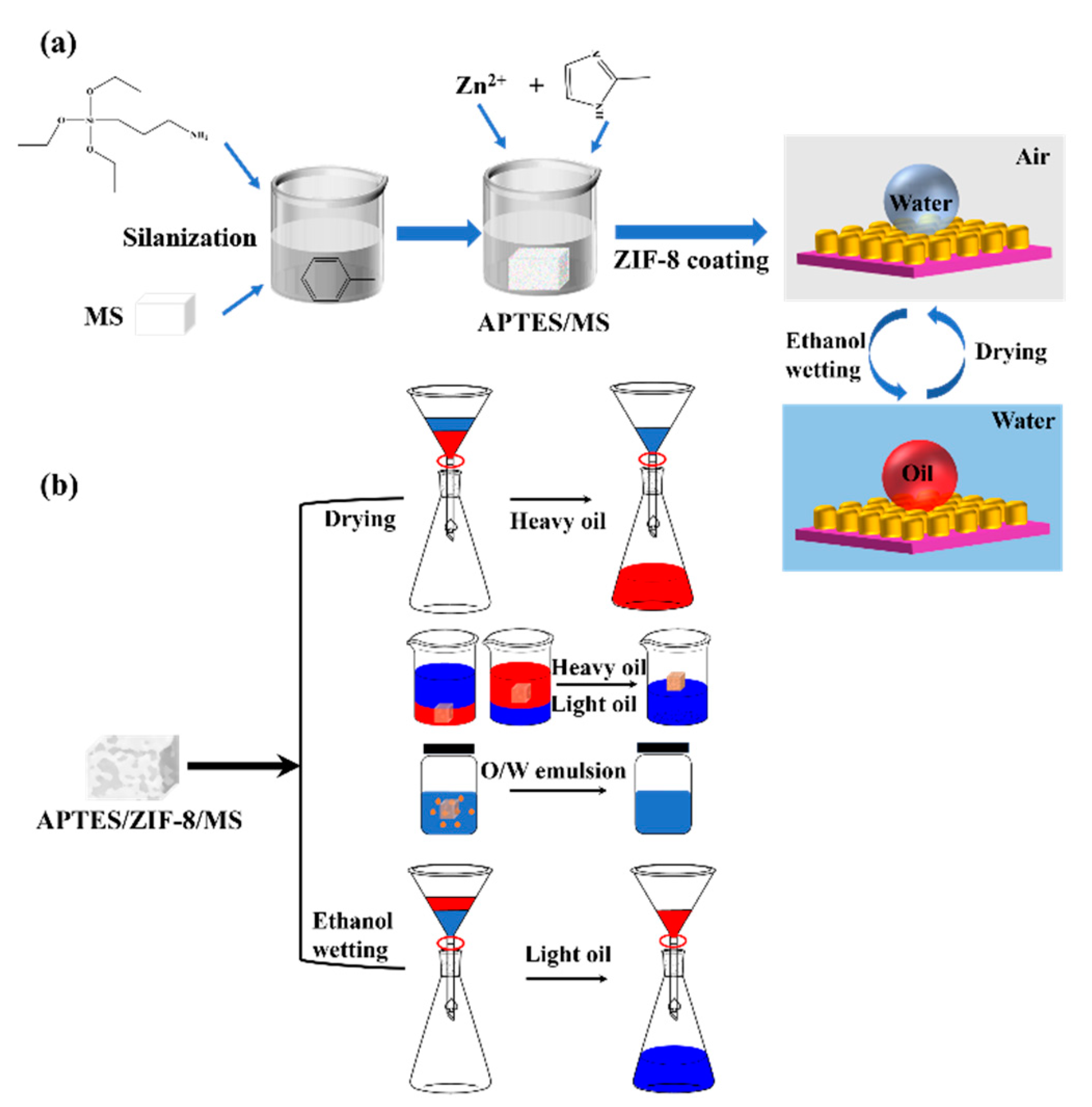

2.2. Preparation of ZIF-8/APTES/MS

2.3. Adsorption Experiments for Oil and Organic Solvent

2.4. Recyclability and Reusability Tests

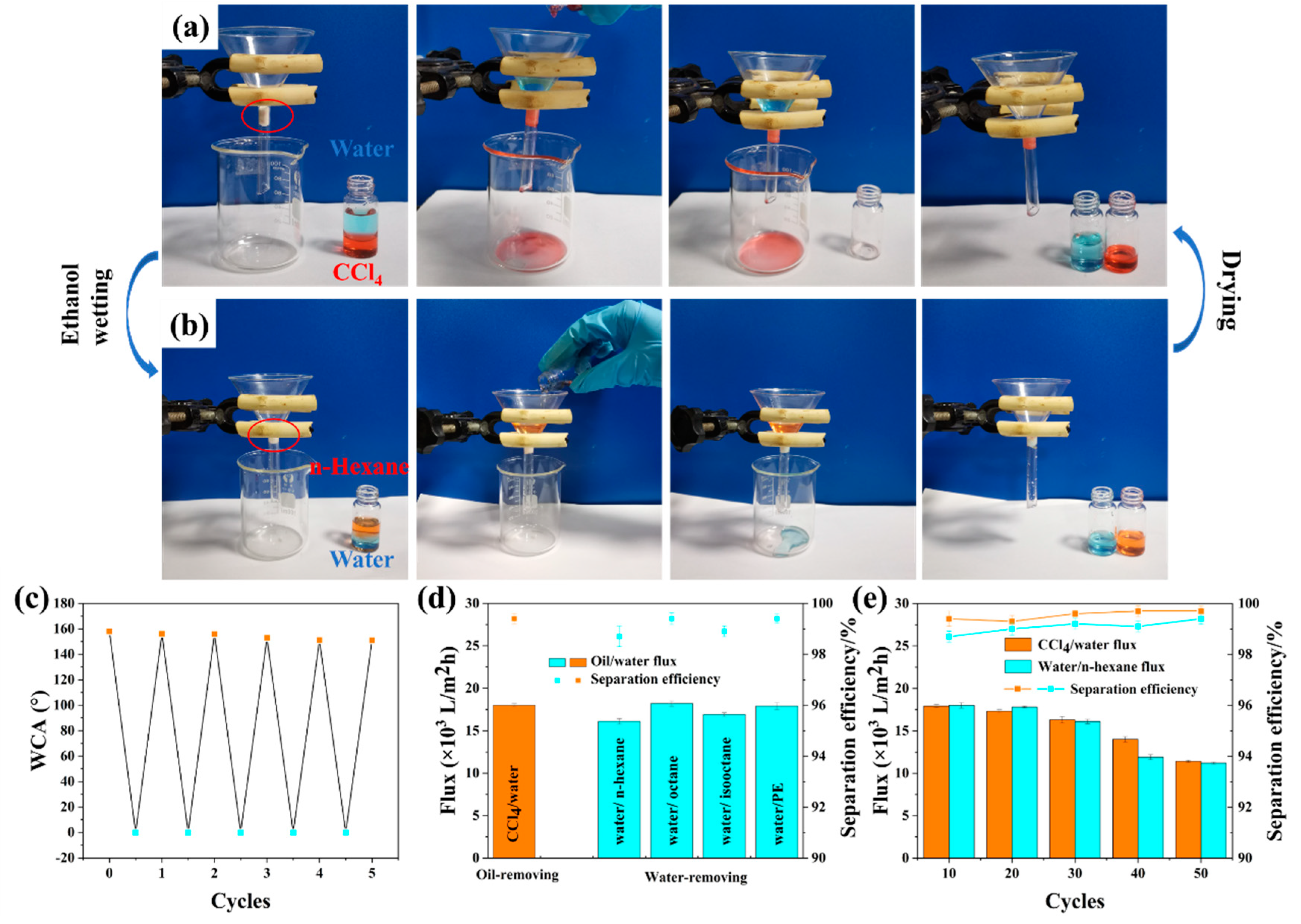

2.5. Oil/water Separation

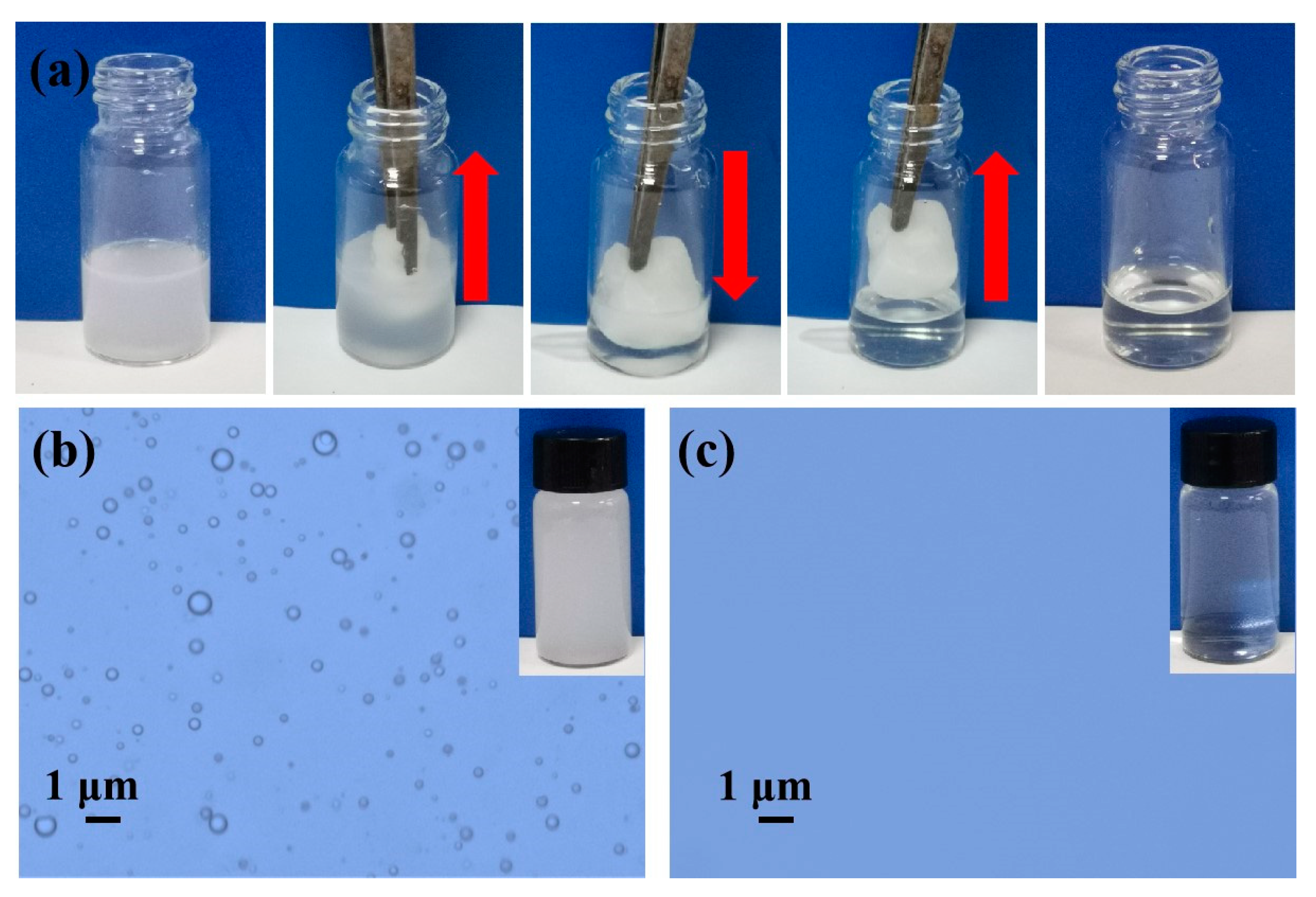

2.6. Emulsion Separation

2.7. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of ZIF-8/APTES/MS Composites

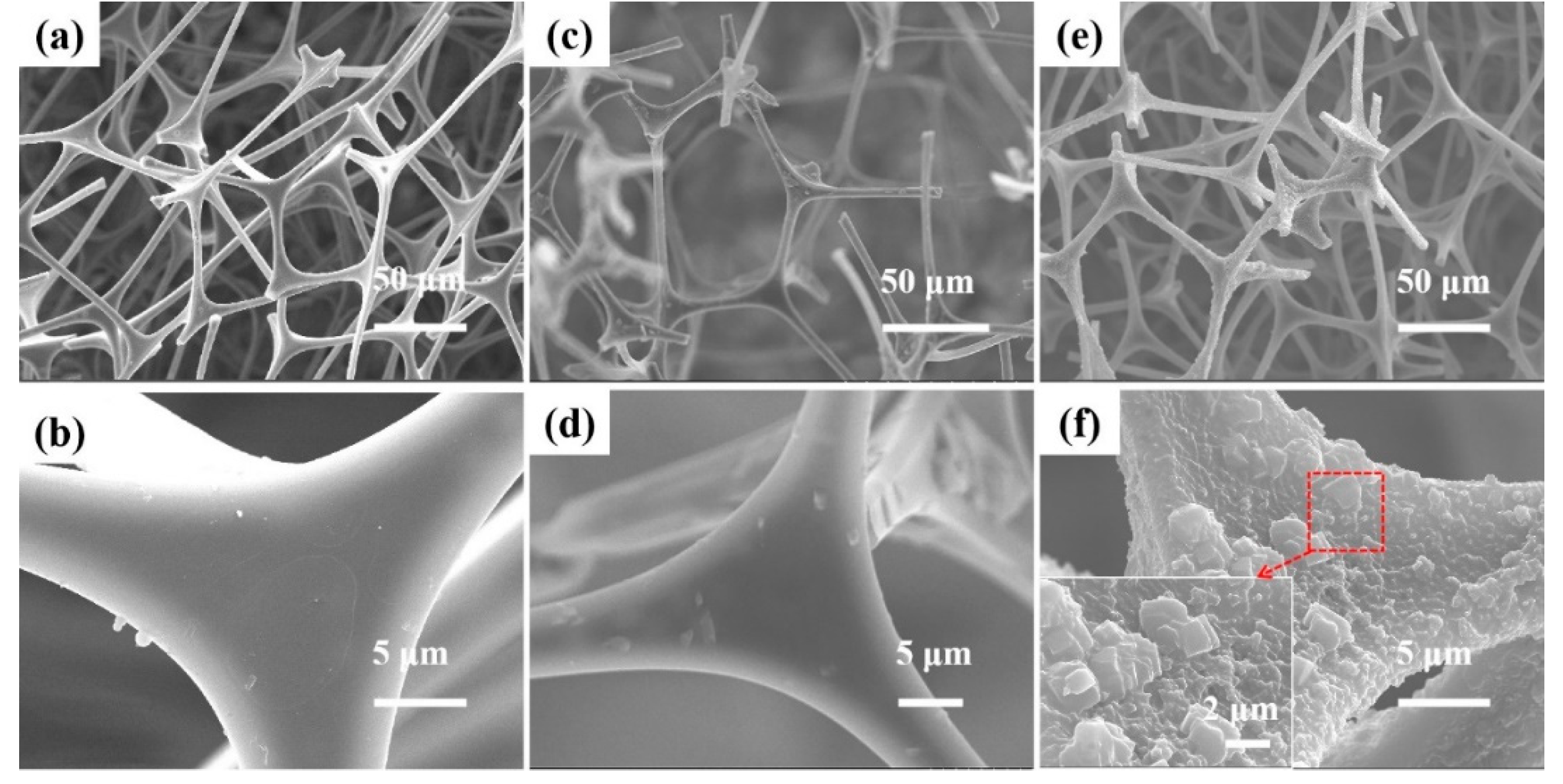

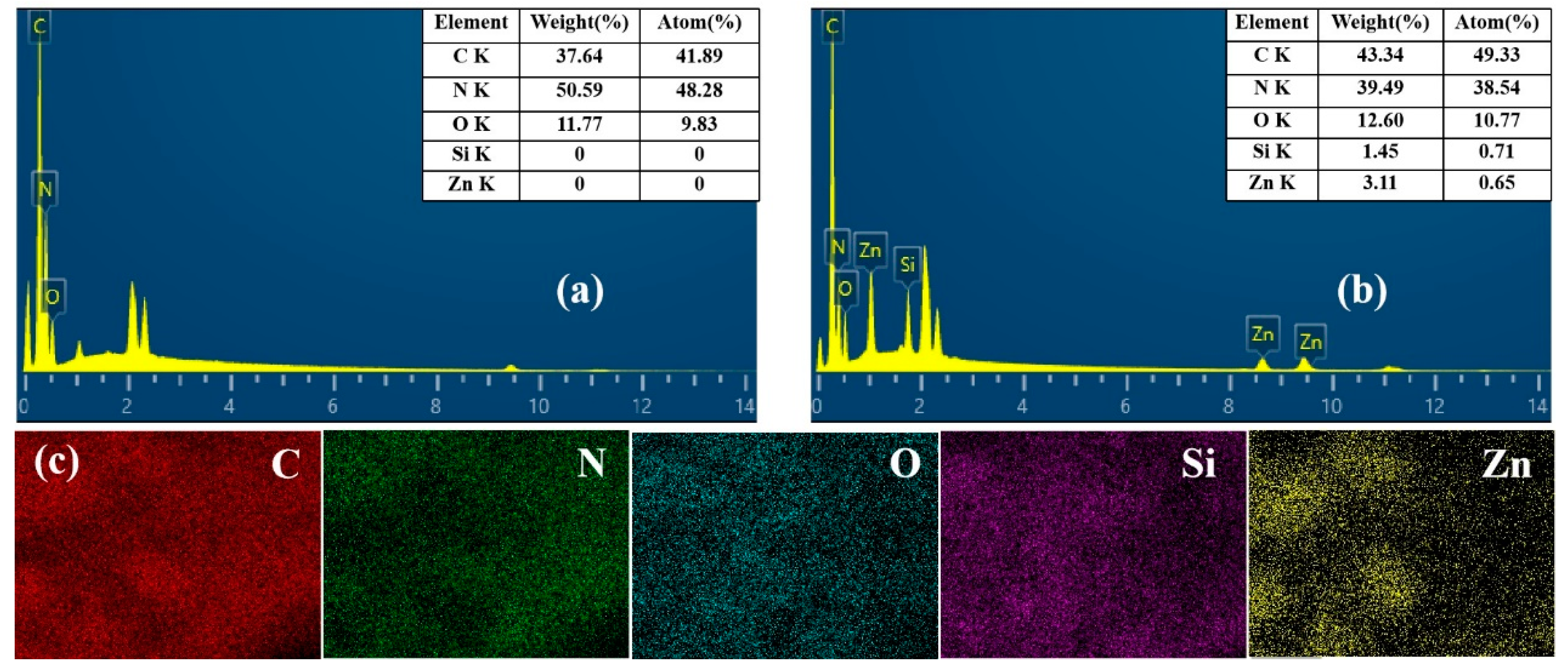

3.1.1. SEM Analysis

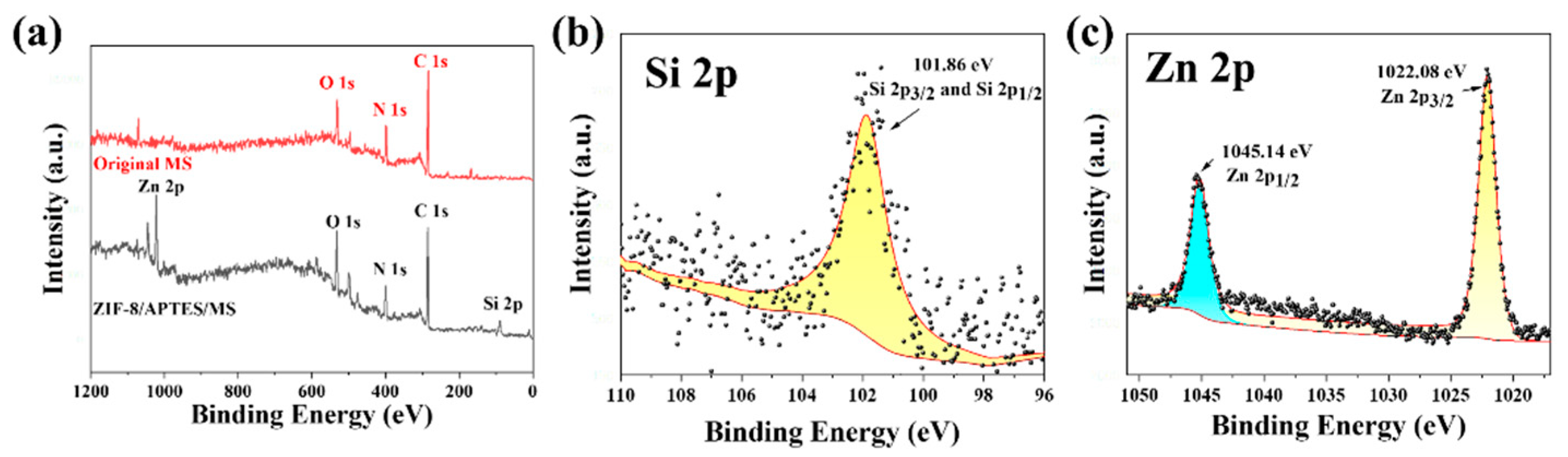

3.1.2. XPS Analysis

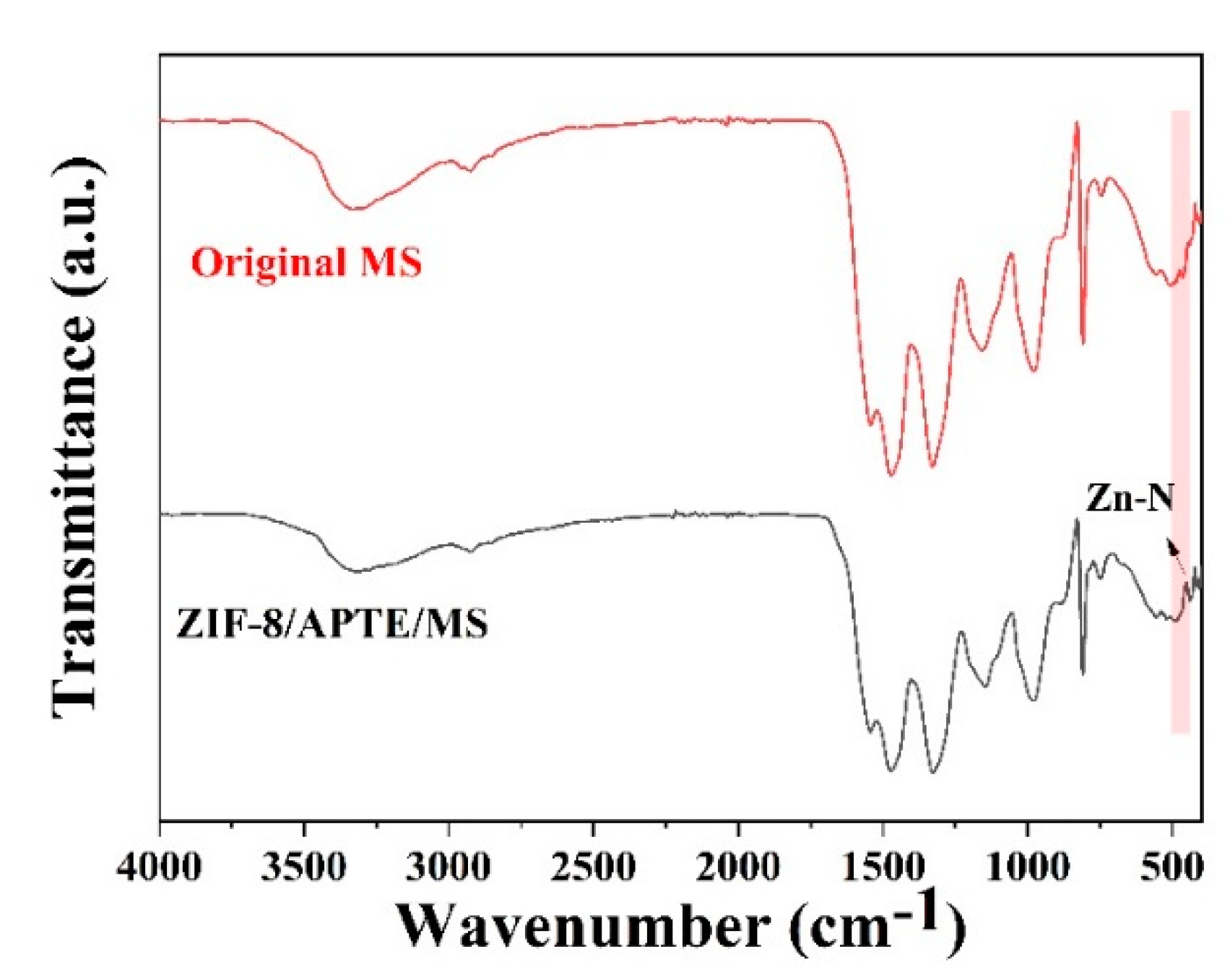

3.1.3. FT-IR Analysis

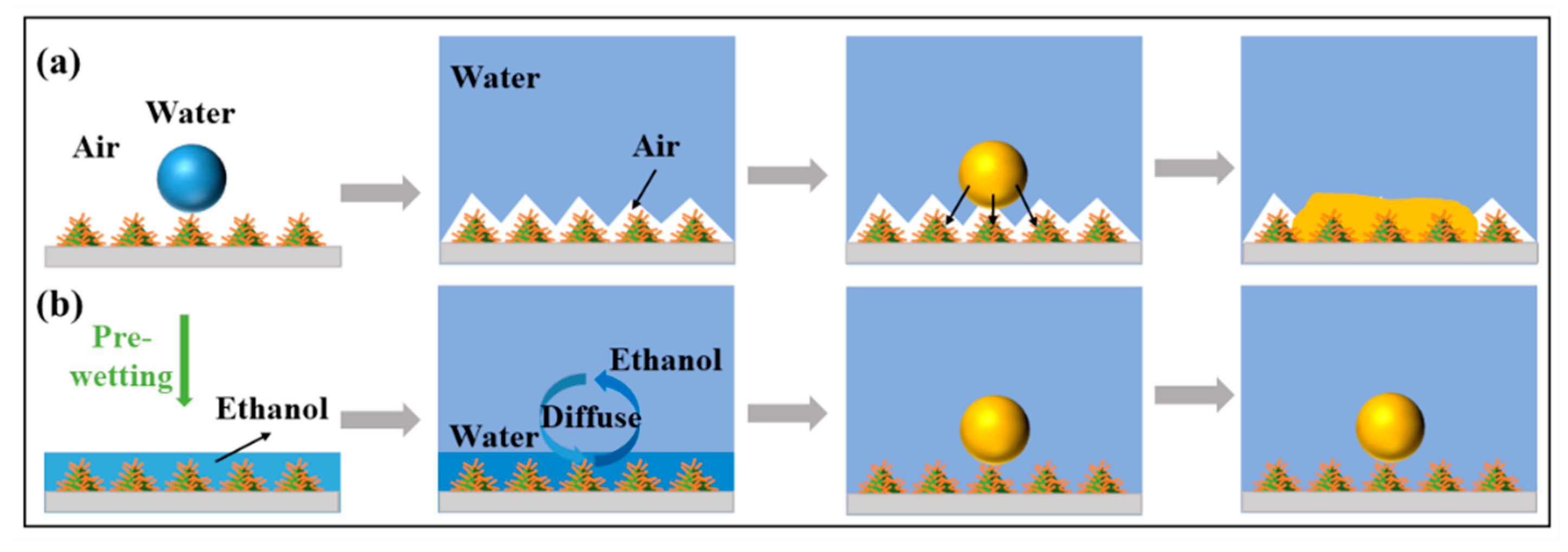

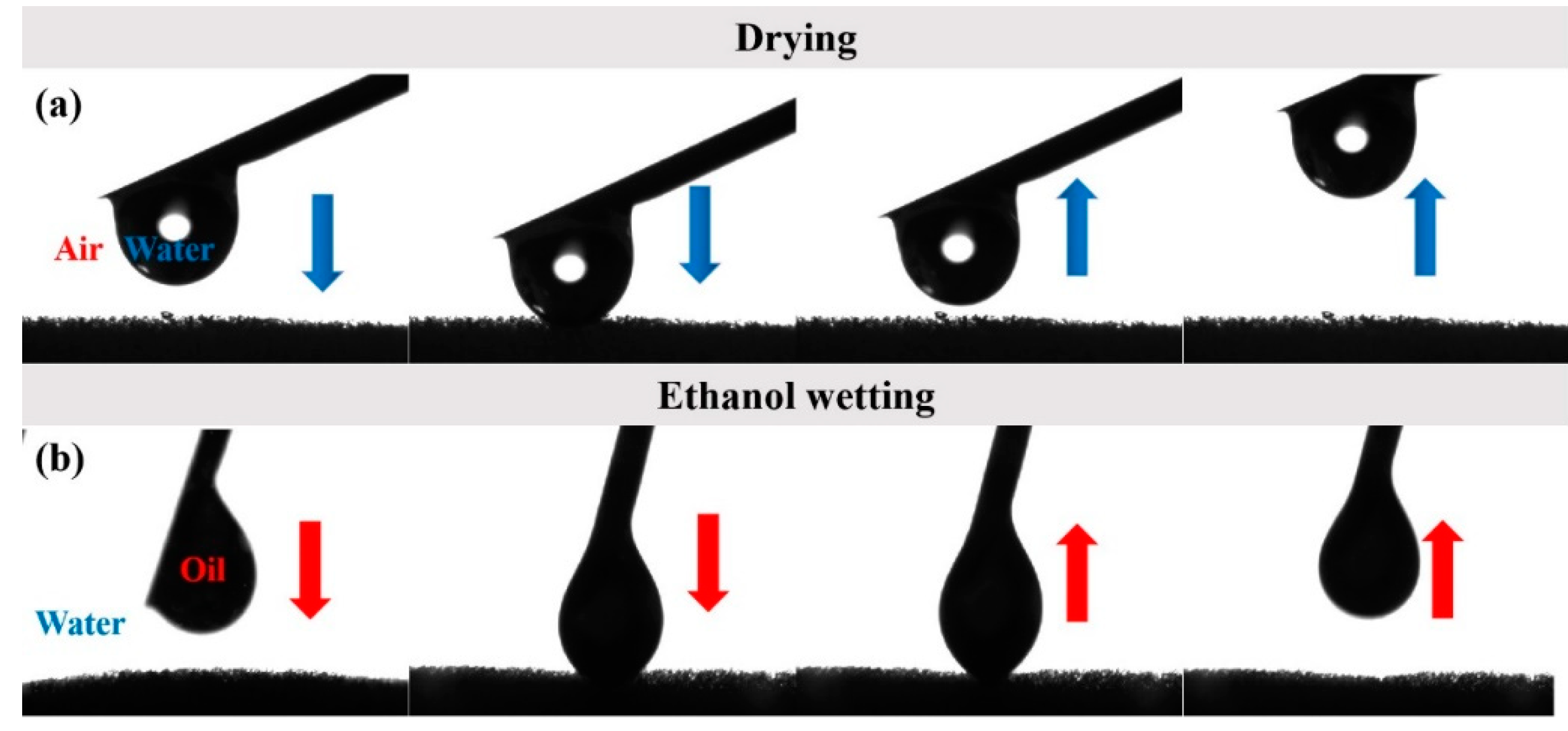

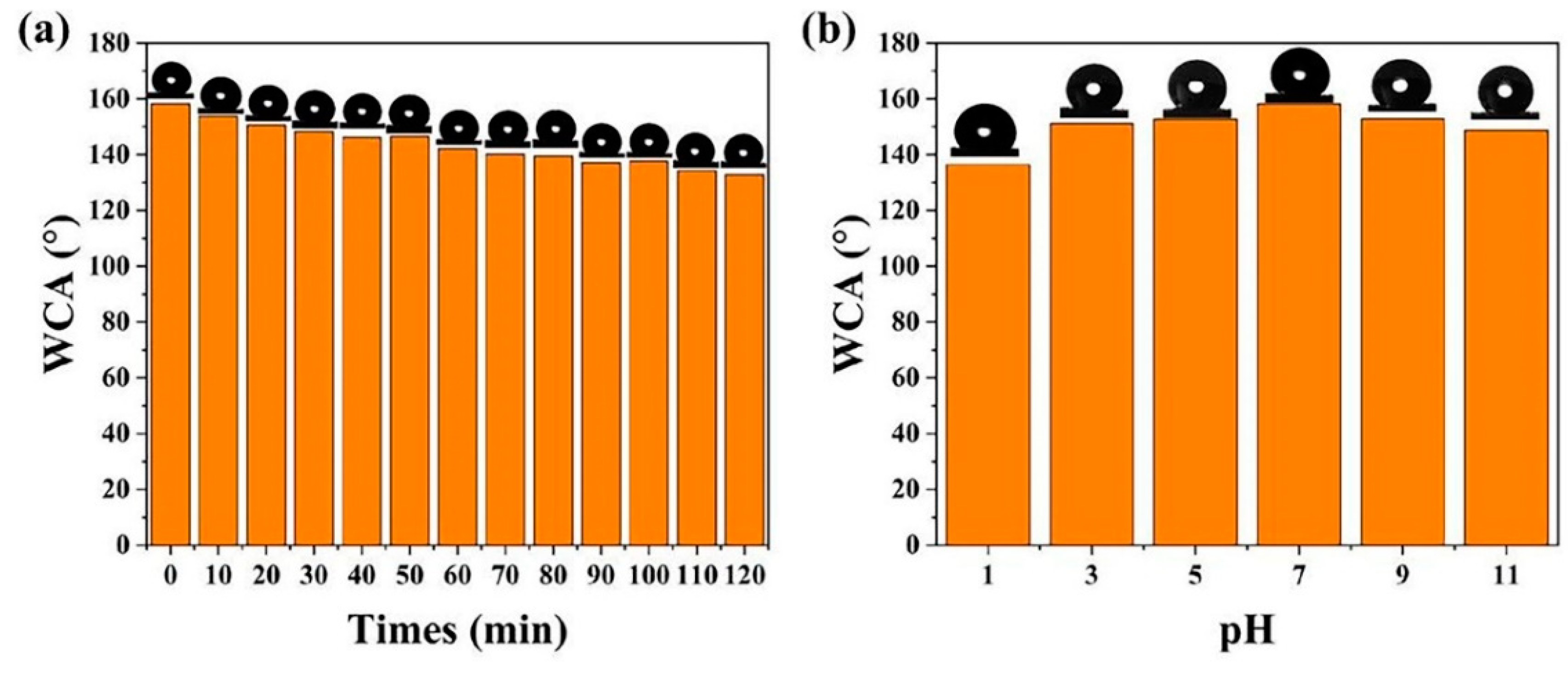

3.2. Surface Wettability Analysis and Antifouling Properties

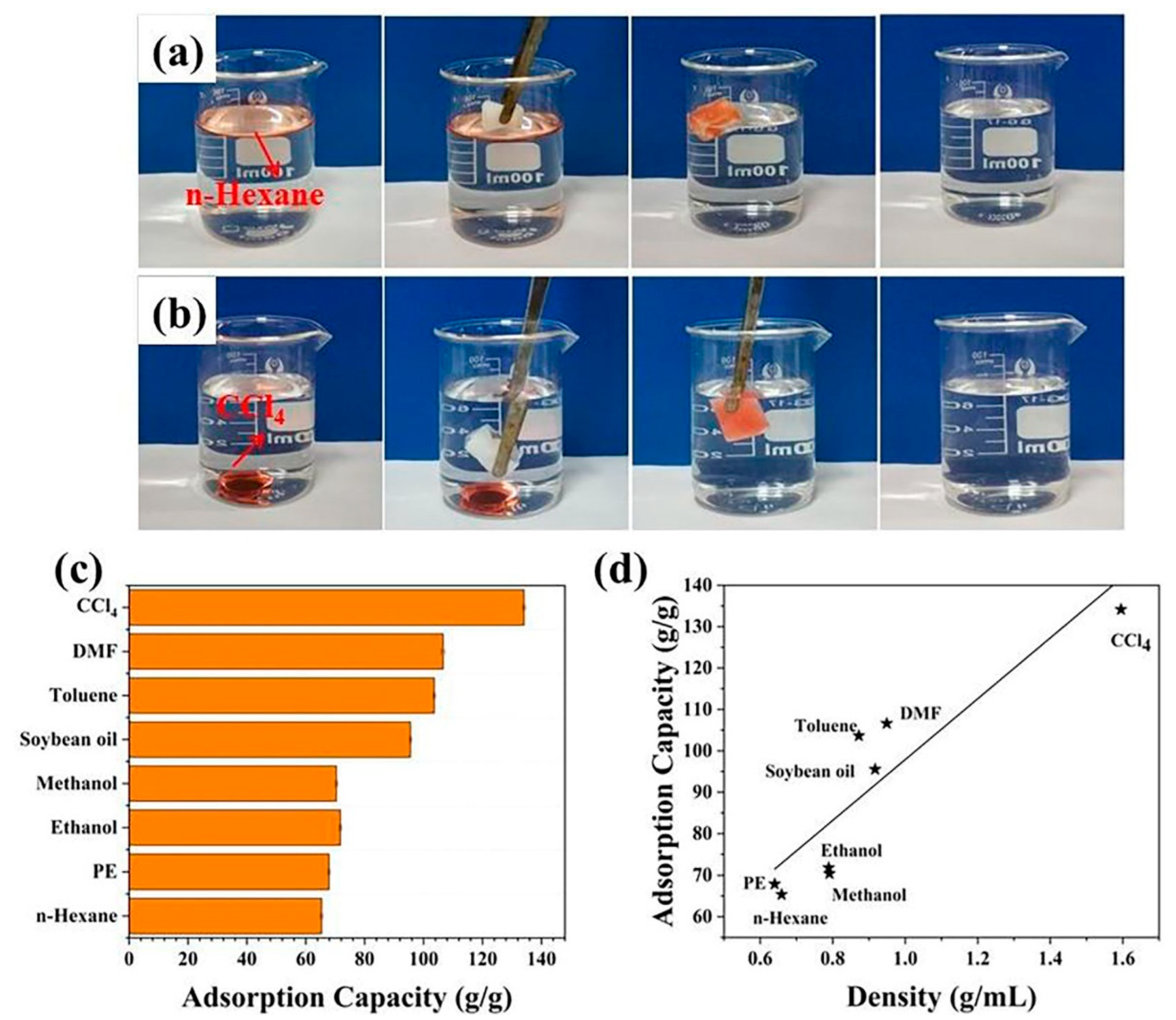

3.3. Adsorption of Oil and Organic Solvents and Oil/Water Separation Properties

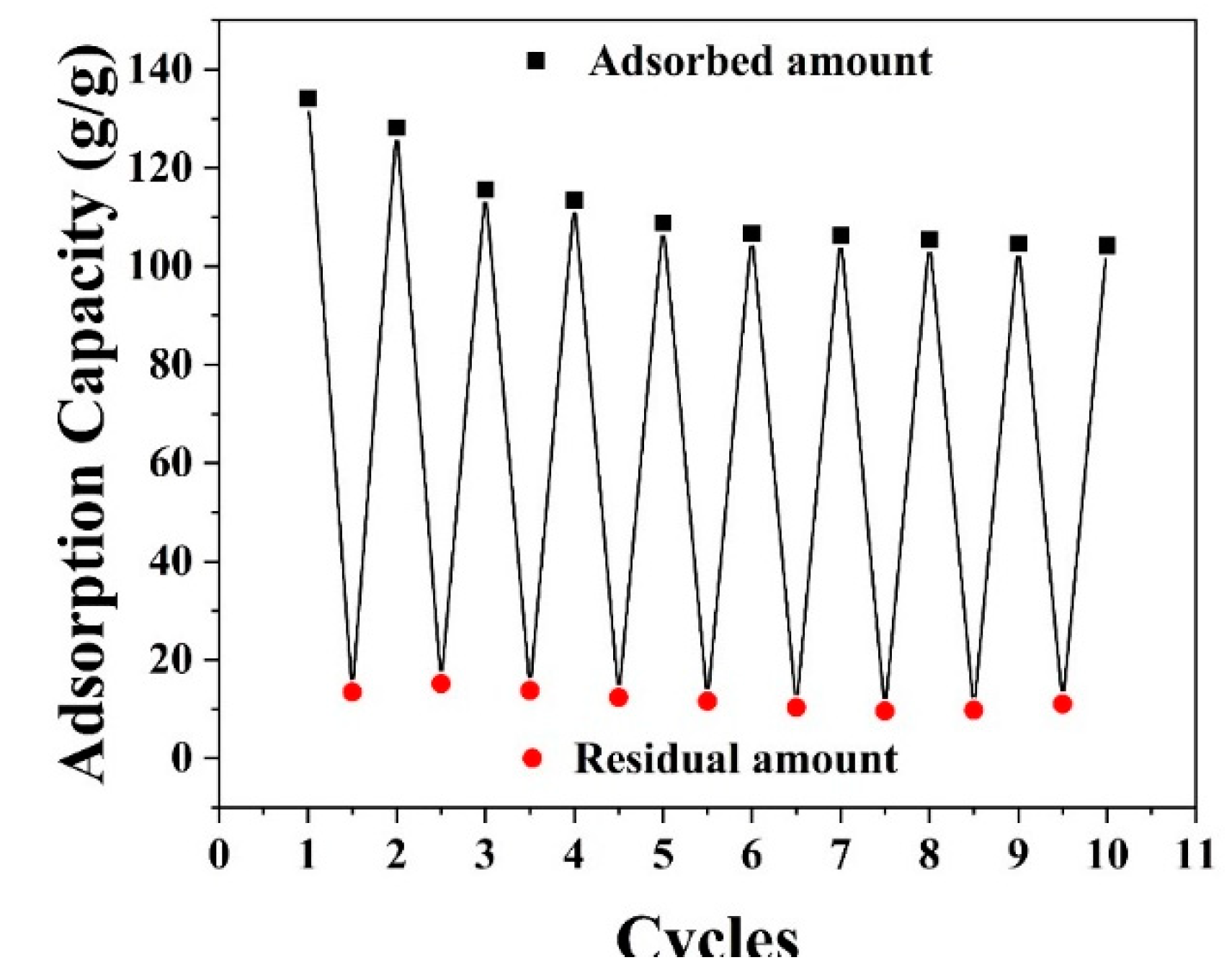

3.4. Emulsion Separation

3.5. Durability and Chemical Stability

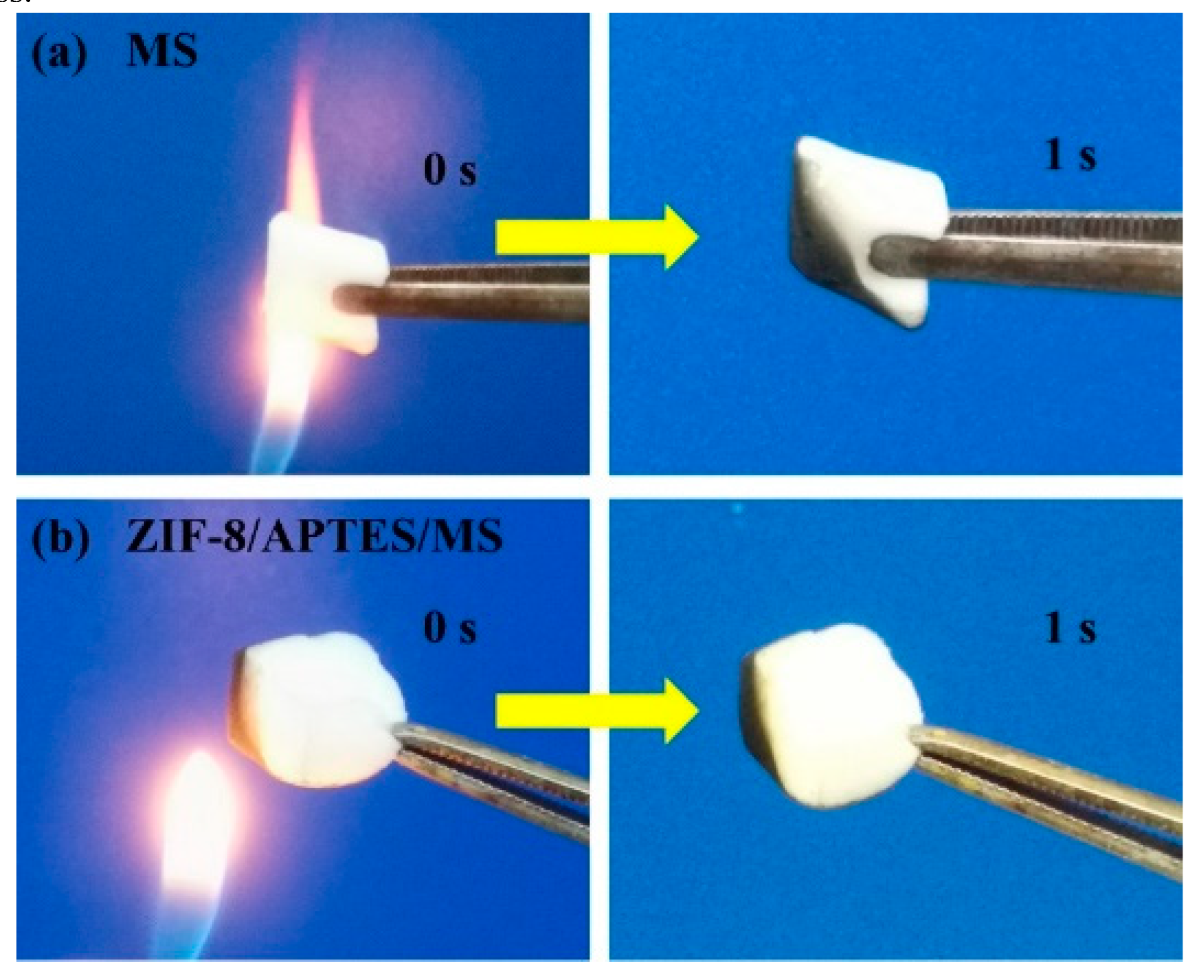

3.6. Flame Retardant

4. Conclusion

Declaration of Competing Interest

Acknowledgments

References

- Wang Z, Guan M, Yang X, Li H, Zhao Y, Chen Y. A Trifecta membrane modified by multifunctional superhydrophilic coating for oil/water separation and simultaneous absorption of dyes and heavy metal, Sep. Purifi. Technol., 2024, 333, 125904. [CrossRef]

- Zhu N X, Wei Z W, Chen C X, et al. Self-generation of surface roughness by low-surface-energy alkyl chains for highly stable superhydrophobic/superoleophilic MOFs with multiple functionalities. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit., 2019, 58(47): 17033-40.

- Zhang N, Qi Y F, Zhang Y N, et al. A review on the oil/water mixture separation material. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2020, 59(33): 14546–68. [CrossRef]

- Pal S, Mondal S, Pal P, et al. Fabrication of durable, fluorine-free superhydrophobic cotton fabric for efficient self-cleaning and heavy/light oil-water separation. Colloid. Interface. Sci. Com., 2021, 44: 100469-481. [CrossRef]

- Saini H, Otyepková E, Schneemann A, et al. Hierarchical porous metal-organic framework materials for efficient oil-water separation. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2022, 10(6): 2751-85. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Yang X, Guan M, Li H, Guo J, Shi H, Li S, Triple-defense design of multifunctional superhydrophilic surface with outstanding underwater superoleophobicity, anti-oil-fouling properties, and high transparency, J.Membr. Sci., 2024, 689, 122161. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Zhang J Q, Zhu L, et al. Reusable membrane with multifunctional skin layer for effective removal of insoluble emulsified oils and soluble dyes. J. Hazard. Mater., 2021, 415: 125677-86. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Shao Y, Wang T, Zhang J, Cui Z, Guo J, Li S, Chen Y, Janus membranes with asymmetric superwettability for high-performance and long-term on-demand oil/water emulsion separation, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2024,16,15558-15568. [CrossRef]

- Deng Y, Peng C, Dai M, et al. Recent development of super-wettable materials and their applications in oil-water separation. J. Clean. Prod., 2020, 266: 121624. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Lin Z, Luo Y, et al. Superhydrophobic MOF based materials and their applications for oil-water separation. J. Clean. Prod., 2023, 420: 138347. [CrossRef]

- Narayan Thorat B, Kumar Sonwani R. Current technologies and future perspectives for the treatment of complex petroleum refinery wastewater: A review. Bioresour. Technol., 2022, 355: 127263. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Luo Y D, Yu F Y, et al. In-situ construction of MOFs-based superhydrophobic/superoleophilic coating on filter paper with self-cleaning and antibacterial activity for efficient oil/water separation. Colloids. Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects, 2021, 625: 126976. [CrossRef]

- Du J C, Zhou C L, Yang Z J, et al. Conversion of solid Cu2(OH)2CO3 into HKUST-1 metal-organic frameworks: Toward an under-liquid superamphiphobic surface. Surf. Coat. Technol., 2019, 363: 282-90. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Zhao Y, Mu S, et al. Uio-66-coated mesh membrane with underwater superoleophobicity for high-efficiency oil-water separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2018, 10(20): 17301-8. [CrossRef]

- Qiu L, Sun Y, Guo Z. Designing novel superwetting surfaces for high-efficiency oil–water separation: Design principles, opportunities, trends and challenges. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2020, 8(33): 16831-53. [CrossRef]

- Zarghami, S.; Mohammadi, T.; Sadrzadeh, M.; Van der Bruggen, B. Superhydrophilic and underwater superoleophobic membranes - A review of synthesis methods. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2019, 98, 101166-101205, doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2019.101166. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.X.; Cui, M.; Huang, R.L.; Su, R.X.; Qi, W.; He, Z.M. Polydopamine-Assisted Surface Coating of MIL-53 and Dodecanethiol on a Melamine Sponge for Oil–Water Separation. Langmuir 2020, 36, 1212-1220, doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b02987. [CrossRef]

- Tamsilian, Y.; Ansari-Asl, Z.; Maghsoudian, A.; Abadshapoori, A.K.; Agirre, A.; Tomovska, R. Superhydrophobic ZIF8/PDMS-coated polyurethane nanocomposite sponge: Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of organic pollutants continuous separation. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 2021, 125, 204-214, doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2021.06.023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.N.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, S.; XLv, i.; Yang, C.; Chen, W.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, W. Facile Preparation of ZIF-67 Coated Melamine Sponge for Efficient Oil/Water Separation. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2019, 58, 17380-17388, doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.9b03208. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Hou, S.Y.; Song, H.L.; Qin, G.W.; Li, P.; Zhang, K.; Li, T.; Han, L.; Liu, W.; Ji, S. A green and facile one-step hydration method based on ZIF-8-PDA to prepare melamine composite sponges with excellent hydrophobicity for oil-water separation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 451, 131064-131083, doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131064. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.X.; Zhang, Y.P.; Du, H.L.; Wan, L.; Zuo, C.-G.; Qu, L.-B. “Two birds with one stone” strategy for oil/water separation based on Ni foams assembled using metal–organic frameworks. New J. Chem. 2023, 10.1039/d3nj02170j, doi:10.1039/d3nj02170j. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Guo, Z. Nonflammable, robust and recyclable hydrophobic zeolitic imidazolate frameworks/sponge with high oil absorption capacity for efficient oil/water separation. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2022, 650, 129570, doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.129570. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, X.; Feng, S.Y. Nonflammable and Magnetic Sponge Decorated with Polydimethylsiloxane Brush for Multitasking and Highly Efficient Oil-Water Separation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1902488-1902500, doi:10.1002/adfm.201902488. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Yan, B.Y.; Huang, W.Q.; Bian, H.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhu, J.; Dong, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W. Room-temperature synthesis of hydrophobic/oleophilic ZIF-90-CF3/melamine foam composite for the efficient removal of organic compounds from wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 132501-132514, doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.132501. [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.J.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, P.C.; Guo, S.; Yao, J. Flexible Co-ZIF-L@melamine sponge with underwater superoleophobicity for water/oil separation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 241, 122385-122390, doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.122385. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.X.; Zhao, X.T.; Jia, N.; Cheng, L.; Liu, L.; Gao, C. Superwetting Oil/Water Separation Membrane Constructed from In Situ Assembled Metal-Phenolic Networks and Metal-Organic Frameworks. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 10000-10008, doi:10.1021/acsami.9b22080. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.H.; Chen, D.Y.; Li, N.J.; Xu, Q.F.; Li, H.; He, J.H.; Lu, J.M. Nanofibrous metal-organic framework composite membrane for selective efficient oil/water emulsion separation. Journal of Membrane Science 2017, 543, 10-17, doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2017.08.047. [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.S.; Bux, H.; Steinbach, F.; Caro, J. Molecular-Sieve Membrane with Hydrogen Permselectivity: ZIF-22 in LTA Topology Prepared with 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane as Covalent Linker. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4958-4961, doi:10.1002/anie.201001919. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Xu, J.K.; Chen, G.J.; Lian, Z.X.; Yu, H.D. Reversible Wettability between Underwater Superoleophobicity and Superhydrophobicity of Stainless Steel Mesh for Efficient Oil–Water Separation. ACS Omega 2020, 6, 77-84, doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c03369. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Q.; Deng, W.J.; Li, C.H.; Sun, Q.; Huang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S. High-Flux Oil/Water Separation with Interfacial Capillary Effect in Switchable Superwetting Cu(OH)2@ZIF-8 Nanowire Membranes. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2018, 10, 40265-40273, doi:10.1021/acsami.8b13983. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.H.; Shi, M.B.; Huang, R.L.; Qi, W.; Su, R.; He, Z. One-pot synthesis of fluorine functionalized Zr-MOFs and their in situ growth on sponge for oil absorption. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2021, 616, 126322-126332, doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.126322. [CrossRef]

- Azam, T.; Pervaiz, E.; Farrukh, S.; Noor, T. Biomimetic highly hydrophobic stearic acid functionalized MOF sponge for efficient oil/water separation. Materials Research Express 2021, 8, 015019-015034, doi:10.1088/2053-1591/abd822. [CrossRef]

- Azam, T.; Pervaiz, E.; Javed, S.; Amina, S.J.; Khalid, M.S. Tuning the hydrophobicity of MOF sponge for efficient oil/water separation. Chemical Physics Impact 2020, 1, 100001-100010, doi:10.1016/j.chphi.2020.100001. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Wang, L.; Shinsuke Nagamine; Ohshima, M. Study oil/water separation property of PE foam and its Improvement by in situ synthesis of zeolitic–imidazolate framework (ZIF-8). Polymer Eegineering and Science 2019, 59, 1354-1361, doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.25118. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.R.; Xie, J.L.; Luo, X.; Gong, X.B.; Zhu, M. Enhanced hydrophobicity of shell-ligand-exchanged ZIF-8/melamine foam for excellent oil-water separation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 273, 118663, doi:10.1016/j.ces.2023.118663. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Wang, L.; Nagamine, S.; Ohshima, M. Study oil/water separation property of PE foam and its improvement by in situ synthesis of zeolitic–imidazolate framework (ZIF-8). Polymer Engineering & Science 2019, 59, 1354-1361, doi:10.1002/pen.25118. [CrossRef]

| Solvent | Polarity | Surface tension (mN/m) | UWOCA (°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol | 6.6 | 23.6 | 151.7° |

| Ethanol | 4.3 | 22.39 | 154.2° |

| Acetonitrile | 6.2 | 22.75 | 153.1° |

| DMF | 7.87 | 25.7 | 150.6° |

| Absorbents | WCA(°) | Absorption capacity(g/g) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZIF-8/SA/PU | 143.2° | 30.28-115.35 | [32] |

| ZIF-8/PU | 129.2° | 28-79 | [33] |

| ZIF-8/PE | - | 17.6-55.8 | [34] |

| ZIF-90/MS | 154° | 24-63 | [36] |

| ZIF-8/PDMS/PU | 156° | 42-58 | [18] |

| ZIF-8/APTES/MS | 158.1° | 65.4-134.2 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).