3.1. CO2 and CH4 Sorption Isotherms

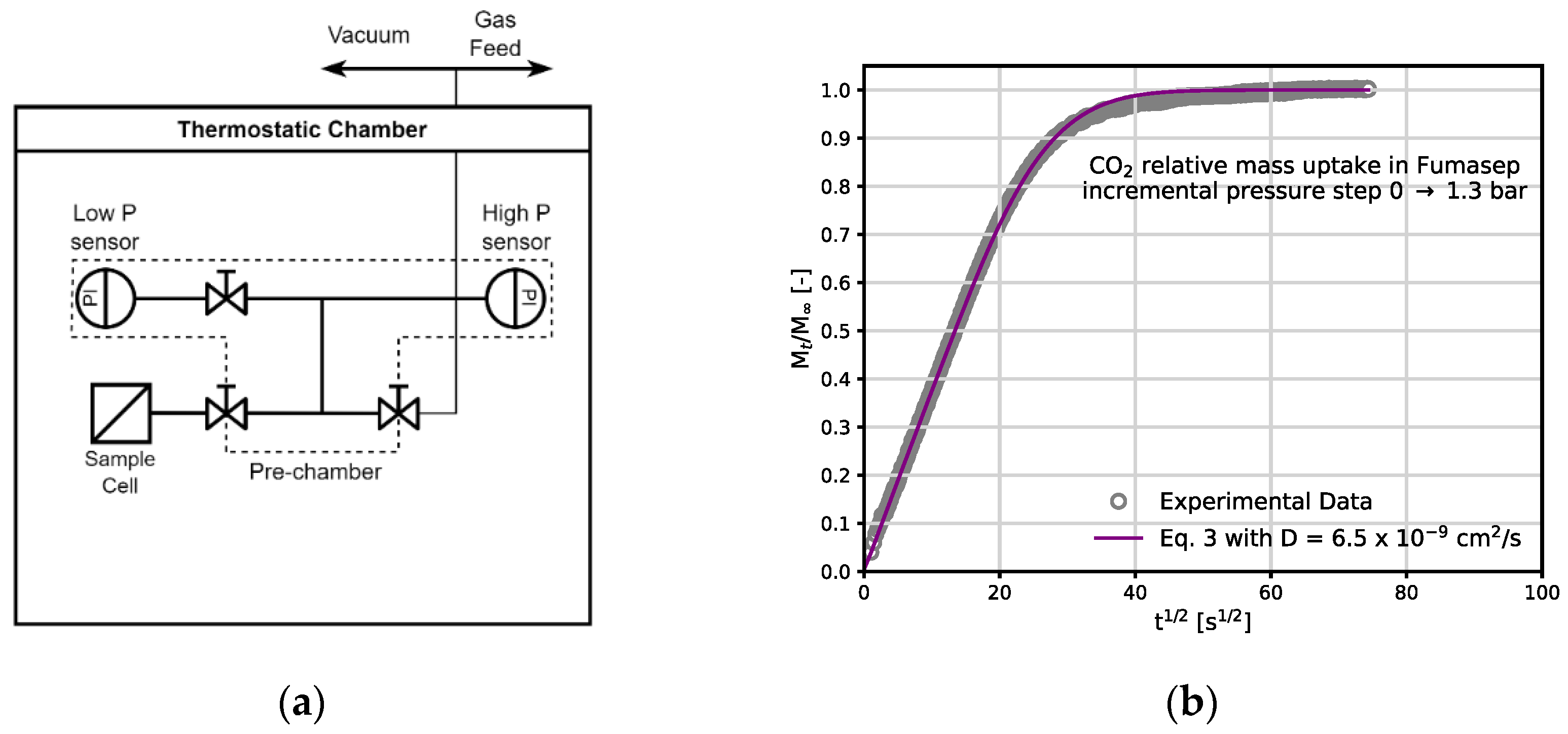

The amount of CO2 and CH4 absorbed at the end of an isothermal pressure step is reported in Figure 3a, in terms of mmol/kg of dry polymer.

Figure 3.

Sorption isotherms in Fumasep

® at 30 °C: (a) CO

2 and CH

4 sorption isotherms; (b) CO

2 sorption in comparison with the literature [

3]. The continuous lines are obtained by fitting the DMS (Eq. 2) or linear Henry’s law model.

Figure 3.

Sorption isotherms in Fumasep

® at 30 °C: (a) CO

2 and CH

4 sorption isotherms; (b) CO

2 sorption in comparison with the literature [

3]. The continuous lines are obtained by fitting the DMS (Eq. 2) or linear Henry’s law model.

CH

4 sorption follows Henry’s law linear behaviour in the Fumasep

® membrane, while CO

2 sorption in the same material follows a convex shape, (

Figure 3a). For the case of CO

2 sorption in dry Fumasep

® , experimental data are available at the same conditions used here, and are shown in

Figure 3b for comparison. It is clear that the data obtained in this work are in excellent agreement with those obtained by independent researchers who reported CO

2 sorption in Fumasep

® [

3].

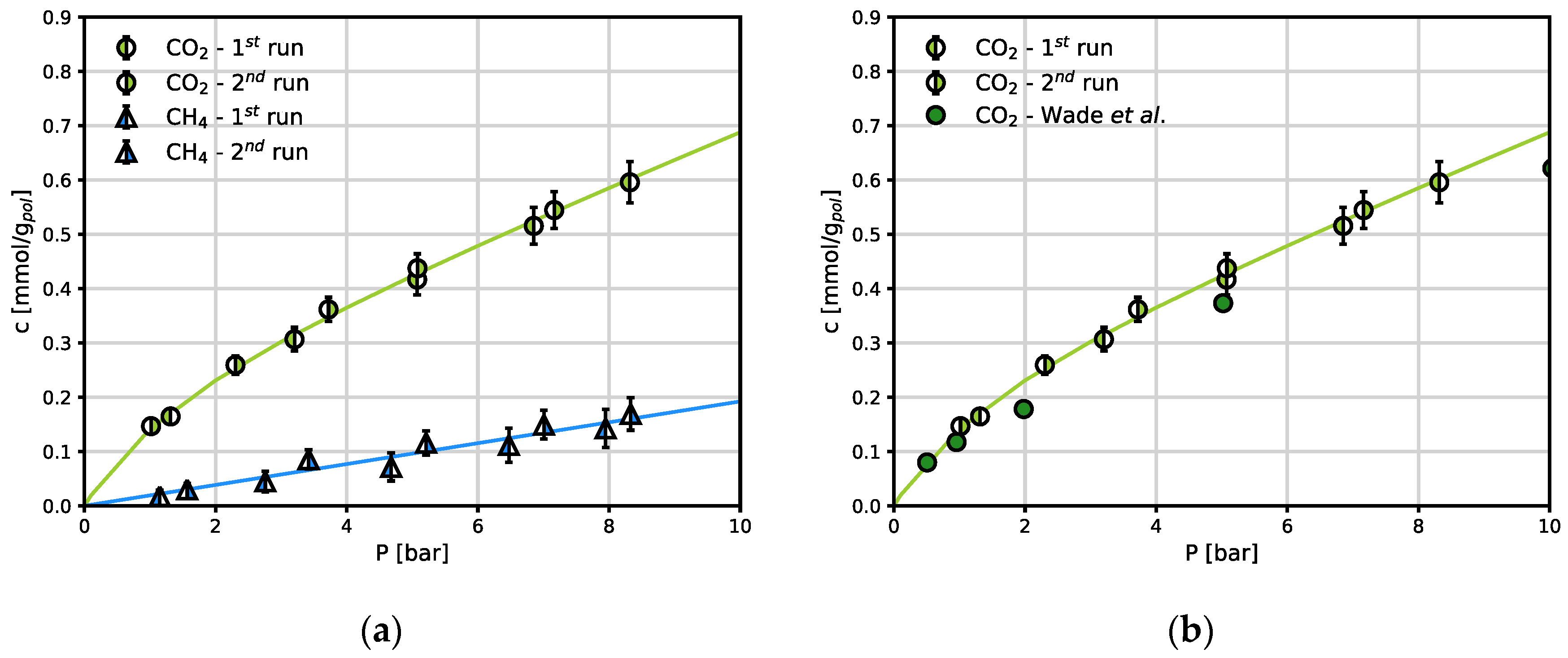

CO

2 and CH

4 sorption isotherms measured under the same conditions in Sustainion

® are reported in

Figure 4. For this polymer, these are the first experimental data of this kind, and there are no literature data to use as benchmark. Sustainion

® is characterized by larger CO

2 sorption levels than Fumasep

® (

Figure 5a), and the same qualitative behavior is followed. CH

4 sorption follows a linear trend, as for the case of Fumasep

®. The DMS parameters for both gases in both polymers are reported in

Table 1: linear isotherms are represented simply by a Henry’s law term and the coefficient

. CH

4 uptake is slightly lower in Fumasep

® than in Sustainion

®.

Figure 4.

CO2 and CH4 sorption isotherms in Sustainion® at 30 °C in the dry state. The solid lines are obtained by fitting the DMS (Eq. 2) or a linear model.

Figure 4.

CO2 and CH4 sorption isotherms in Sustainion® at 30 °C in the dry state. The solid lines are obtained by fitting the DMS (Eq. 2) or a linear model.

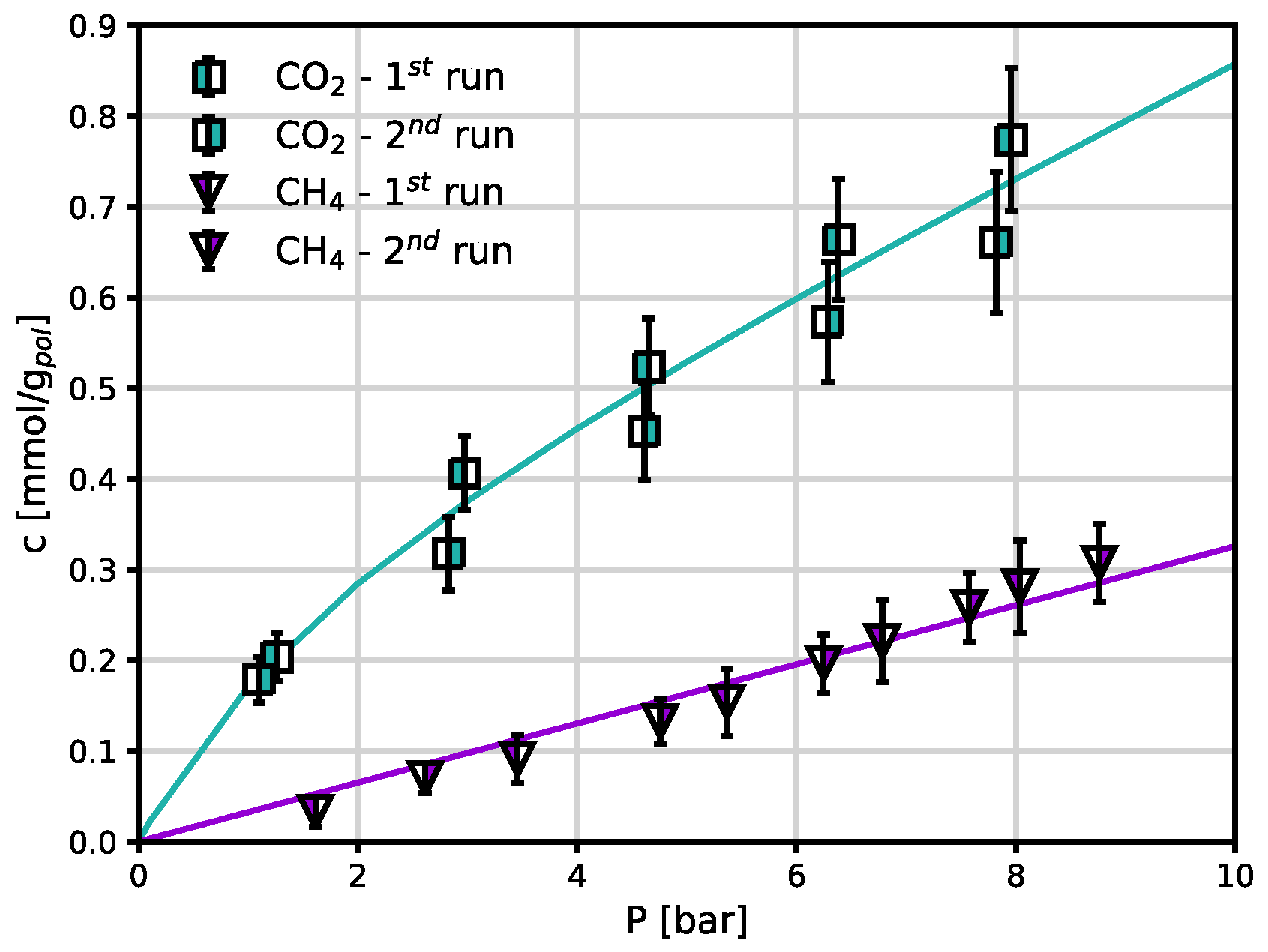

Figure 5.

Comparison of CO2 and CH4 sorption in Fumasep® and Sustainion®: (a) CO2 and CH4 sorption isotherms as determined by the DMS (Eq. 2) and linear models; (b) CO2/CH4 solubility-selectivity as function of pressure, evaluated using DSM models for each gas.

Figure 5.

Comparison of CO2 and CH4 sorption in Fumasep® and Sustainion®: (a) CO2 and CH4 sorption isotherms as determined by the DMS (Eq. 2) and linear models; (b) CO2/CH4 solubility-selectivity as function of pressure, evaluated using DSM models for each gas.

Table 1.

The DMS model (Eq. 2) correlation parameters for the CO2 and CH4 sorption isotherms in the anion exchange membranes investigated, together with the coefficient of determination.

Table 1.

The DMS model (Eq. 2) correlation parameters for the CO2 and CH4 sorption isotherms in the anion exchange membranes investigated, together with the coefficient of determination.

| Material |

|

|

× 102

mmol g-1 bar-1

|

× 101

mmol g-1

|

bar-1

|

|

mmol g-1 bar-1

|

|

| Fumasep®

|

4.80 ± 0.15 |

2.41 ± 0.24 |

0.64 ± 0.01 |

0.997 |

1.92 ± 0.21 |

0.934 |

| Sustainion®

|

5.78 ± 0.02 |

3.34 ± 0.75 |

0.51 ± 0.12 |

0.959 |

3.26 ± 0.04 |

0.961 |

Due to the shape of the solubility isotherm, the solubility coefficient (of CO2 in both materials decreases rapidly with pressure and thus the ideal solubility-selectivity reported in Figure 5b, decreases from values of approximately 10 to above 2. Interestingly, the best separation performance is exhibited at low pressure, that is the one of interest for several CO2 capture processes.

Overall, the differences between the two materials are limited and quantitative, rather than qualitative: Fumasep® sorbs slightly less CO2 but is more selective with respect to CH4 than Sustainion®, in pure gas conditions.

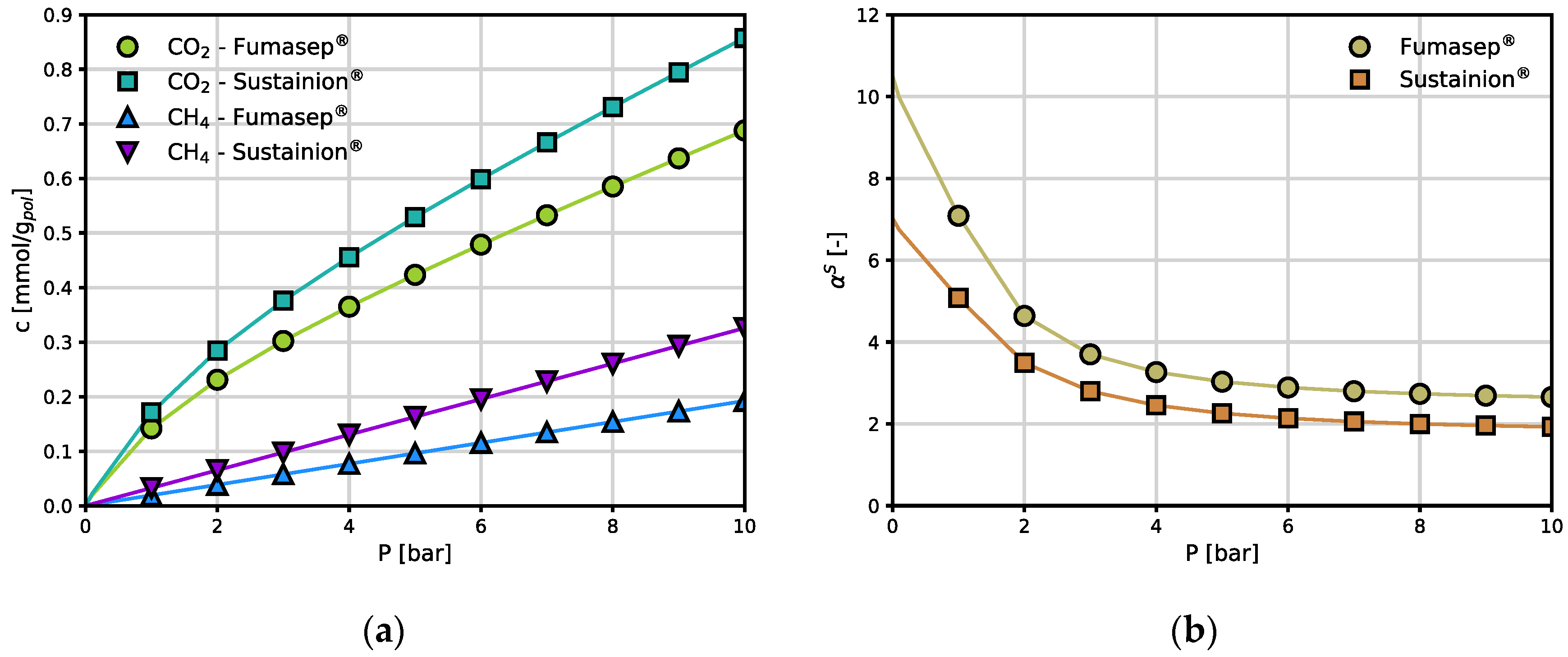

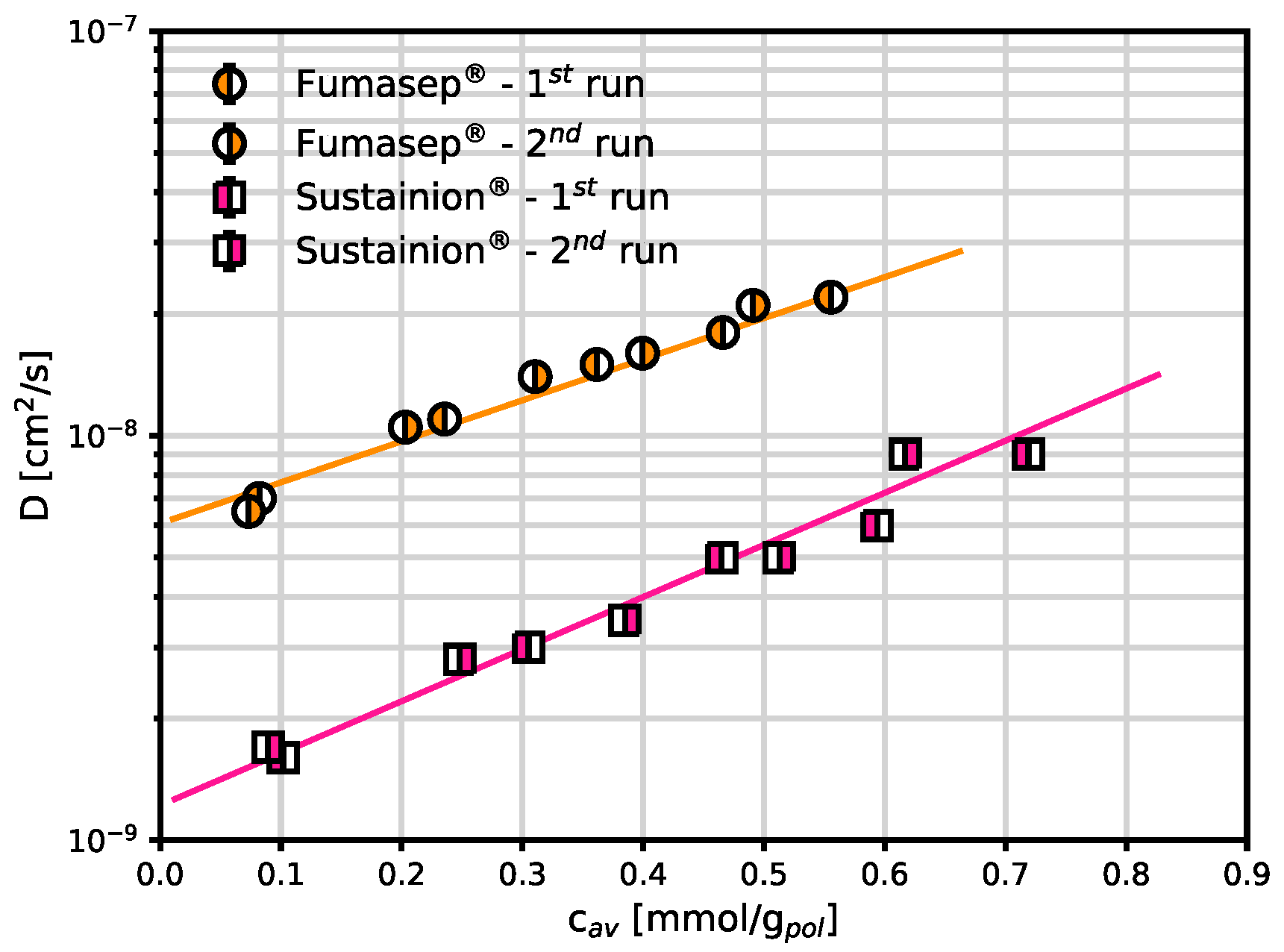

The diffusion coefficients of CO

2 were estimated from the transient mass uptake in the polymers, as described in the methods section. These are the first experimentally obtained CO

2 diffusion values in these polymers: a value was given in the literature for Fumasep

® (

cm

2/s [

3]) but it was estimated as the ratio between independent permeability and solubility data. In our case the diffusion coefficient was obtained directly by fitting the transient sorption data with Eq. 3. The same procedure was also attempted with CH

4 but, due to the small level of sorption in this polymer and the low amount of sample available, it did not yield reliable results. Interestingly, CO

2 diffusion coefficients in both materials follow an exponential dependence on concentration. The CO

2 diffusivity in Sustainion

® increases from 1.6 to 9.0·10

-9 cm

2/s within the range examined, while Fumasep

® is significantly higher and goes from 0.7 to 2.2·10

-8 cm

2/s. These differences could be due to a smaller initial free volume of Sustainion

® compared to Fumasep

®. However, as it is typical of membranes characterised by smaller initial free volume, the dependence on concentration represented by the parameter

is higher for the Sustainion

® membrane than for Fumasep

®. The slope is significant and allows the diffusion coefficients to increase by one order of magnitude by increasing the CO

2 pressure from 0 to 8 bar, indicating an appreciable effect of CO

2-induced swelling on the transport behavior, which should be taken into account when designing the separation process.

Figure 6.

CO2 diffusion coefficients in Fumasep® and Sustainion®, determined from sorption transient at 30 °C in the dry state, as function of average CO2 concentration. The continuous lines are obtained from a best fit to the exponential correlation (Eq. 4).

Figure 6.

CO2 diffusion coefficients in Fumasep® and Sustainion®, determined from sorption transient at 30 °C in the dry state, as function of average CO2 concentration. The continuous lines are obtained from a best fit to the exponential correlation (Eq. 4).

Table 2.

The exponential fitting (Eq. 4) correlation parameters for CO2 diffusion at 30 °C in the AEM investigated, together with the coefficient of determination.

Table 2.

The exponential fitting (Eq. 4) correlation parameters for CO2 diffusion at 30 °C in the AEM investigated, together with the coefficient of determination.

| Material |

× 109

cm2 s-1

|

mmol g-1

|

|

| Fumasep®

|

6.07 ± 0.19 |

2.34 ± 0.15 |

0.977 |

| Sustainion®

|

1.22 ± 0.11 |

2.96 ± 0.31 |

0.921 |

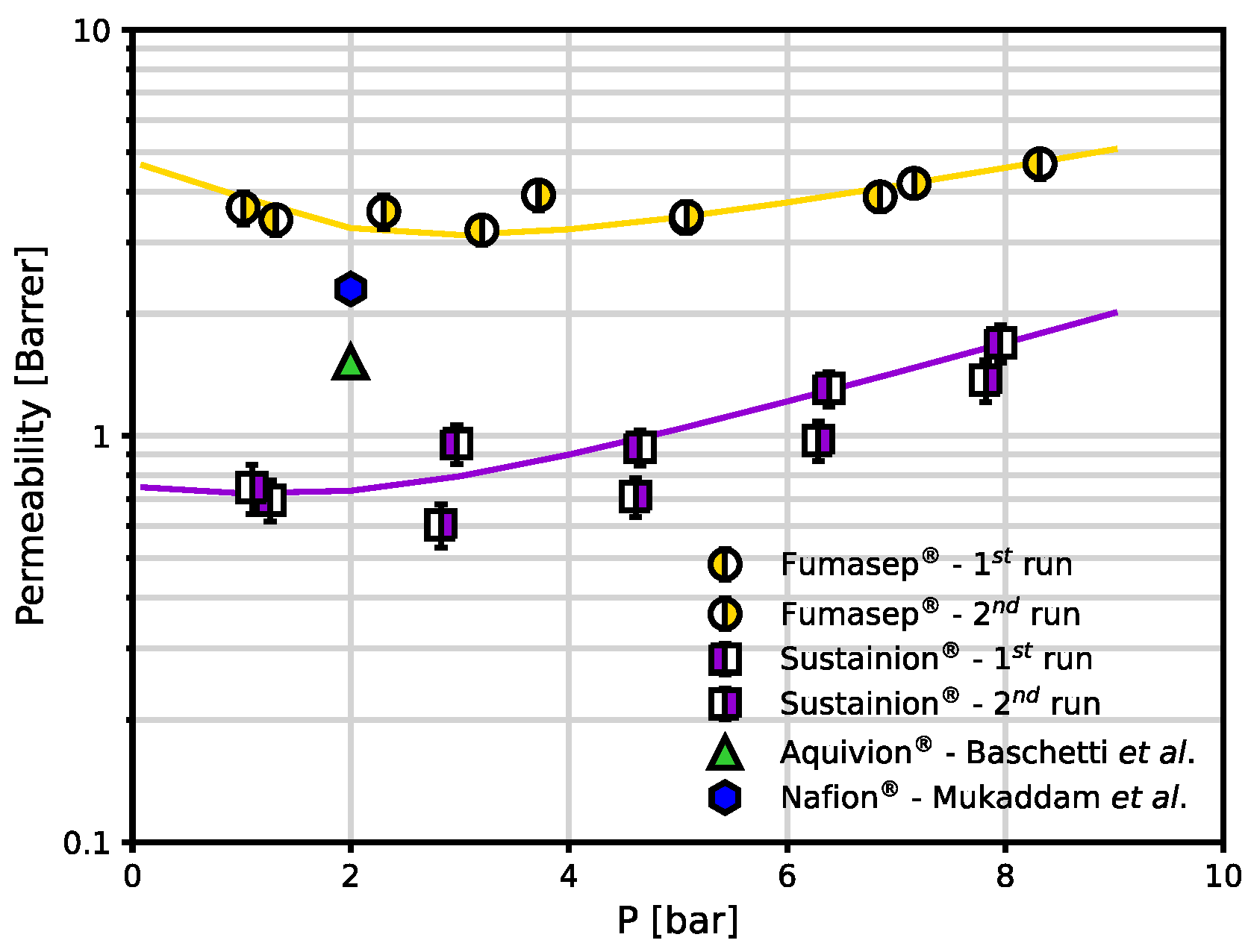

Finally, the permeability coefficients were evaluated as the product between diffusivity and solubility for CO2, in the two materials (Eq. 5) and reported in Figure 7. Due to the combination of solubility and diffusivity effects, Fumasep® shows a higher CO2 permeability than Sustainion®. Permeability varies from 3.4 to 4.7 Barrer and from 0.7 to 1.7 for Sustainion. Also, as S decreases sharply in the low-pressure range while D continues to increase exponentially as S flattens out at medium pressures, the permeability shows a minimum (3.2 Barrer for Fumasep® at about 3 bar, 0.6 Barrer for Sustainion® at 2.8 bar). This threshold is sometimes indicated as the plasticization pressure in the membrane literature and is typically observed in the CO2 permeation through glassy polymers.

Figure 7.

CO

2 permeability coefficients in Fumasep

® and Sustainion

® at 30°C in the dry state, evaluated as the product of solubility and diffusivity coefficients. The continuous lines are reported as guide to the eye. CO

2 permeability in Aquivion

® [

13] and Nafion

® [

14] at 35 °C at 2 bar transmembrane pressure is reported for comparison.

Figure 7.

CO

2 permeability coefficients in Fumasep

® and Sustainion

® at 30°C in the dry state, evaluated as the product of solubility and diffusivity coefficients. The continuous lines are reported as guide to the eye. CO

2 permeability in Aquivion

® [

13] and Nafion

® [

14] at 35 °C at 2 bar transmembrane pressure is reported for comparison.

Finally, we report CO

2 dry permeability values obtained in the literature for other ion exchange membranes, namely two fluorinated matrices which go under the trade name of Aquivion

® [

13] and Nafion

® [

14]. In particular, Nafion

® was tested after being dried at 80°C for 48 h [

14], at 35 °C and 2 bar upstream pressure, while Aquivion

® was pre-dried at 100°C for 24 h, tested at 35 °C and 2 bar [

13]. The permeability of these two materials lies in between the values obtained in this work for Sustainion

® and Fumasep

®, respectively.