Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

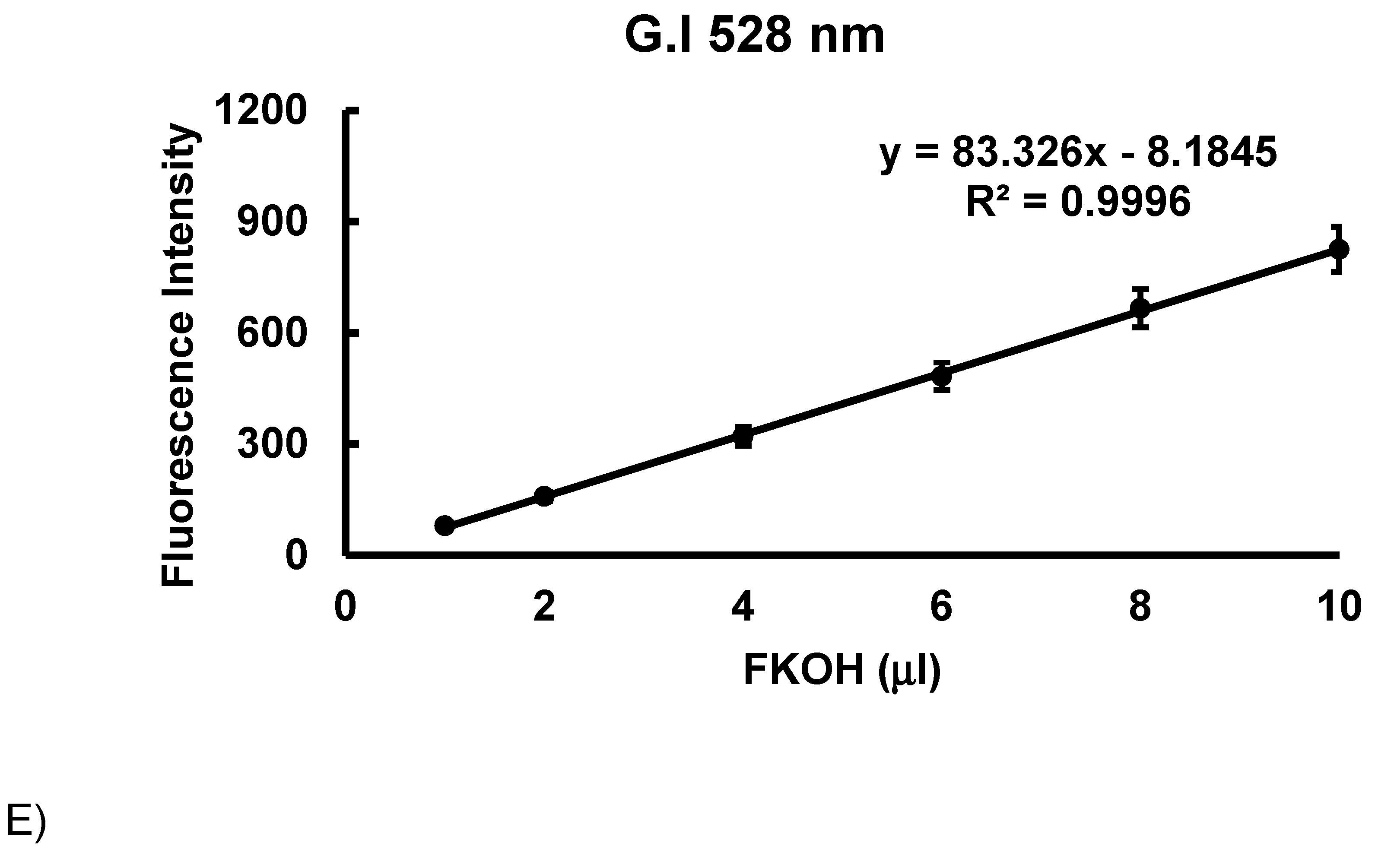

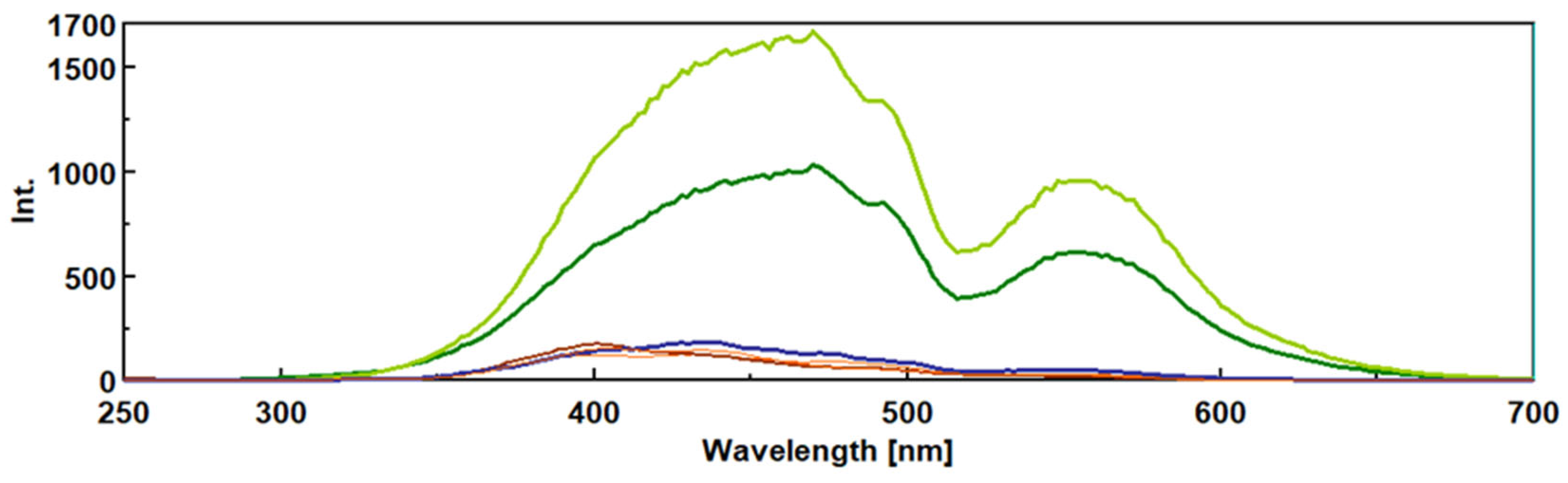

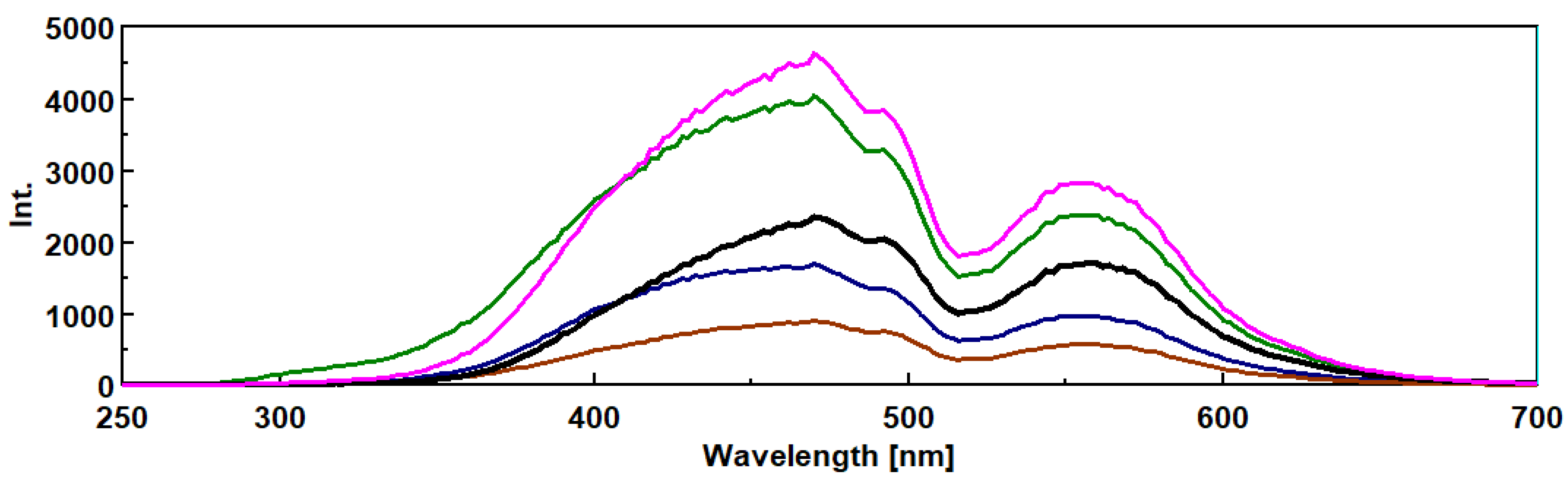

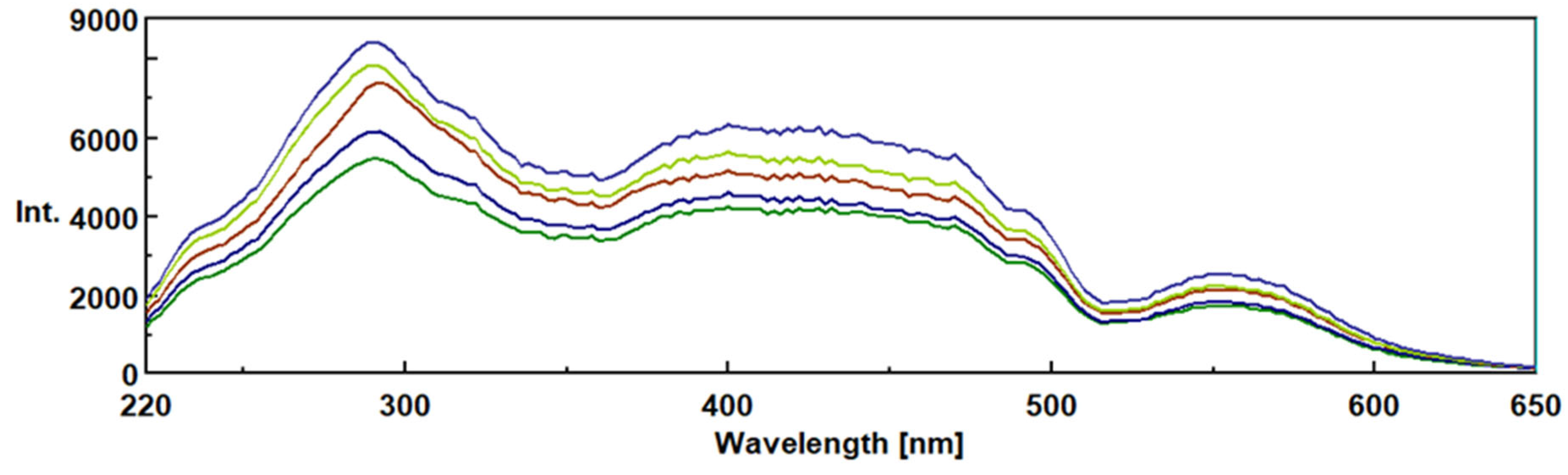

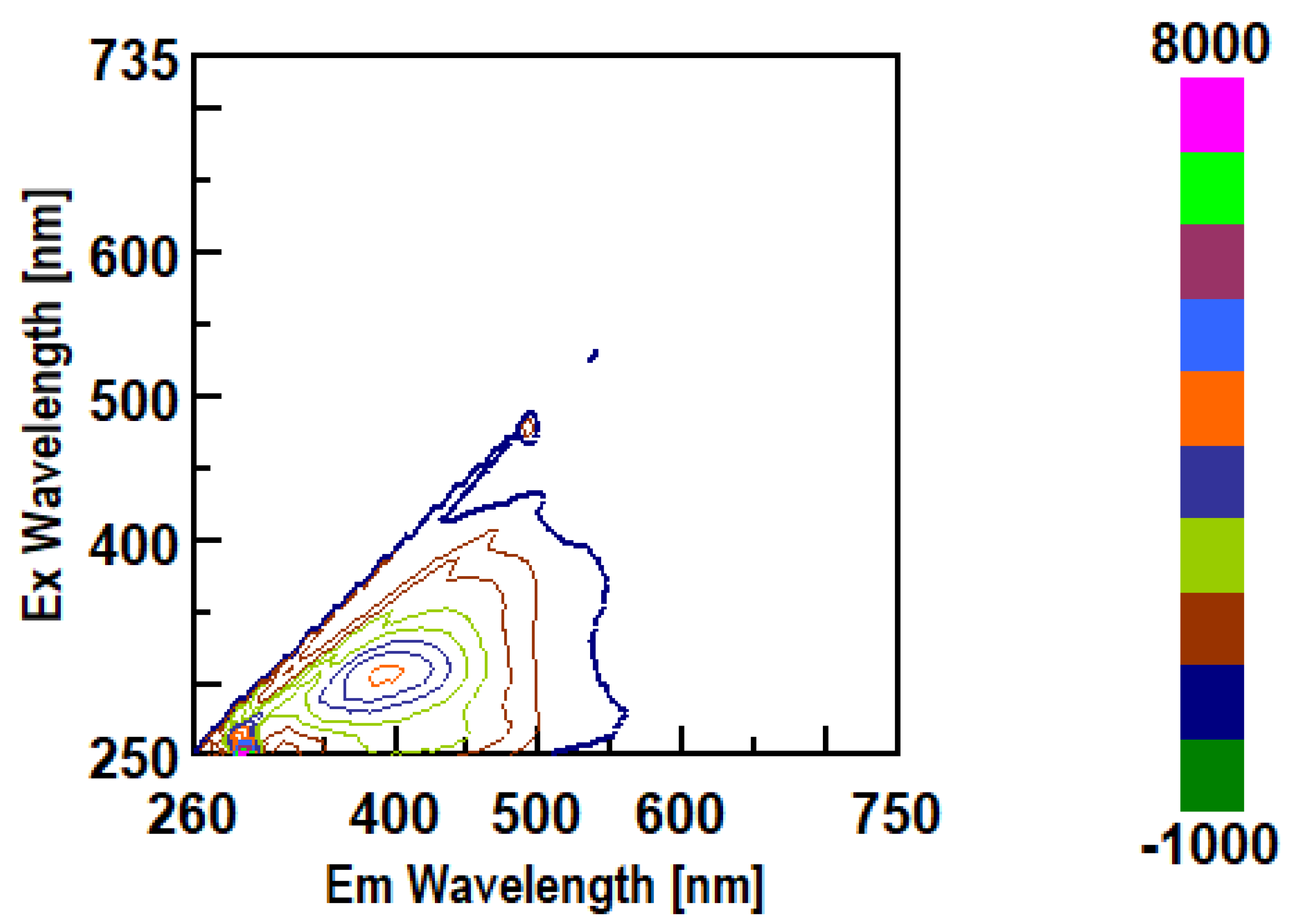

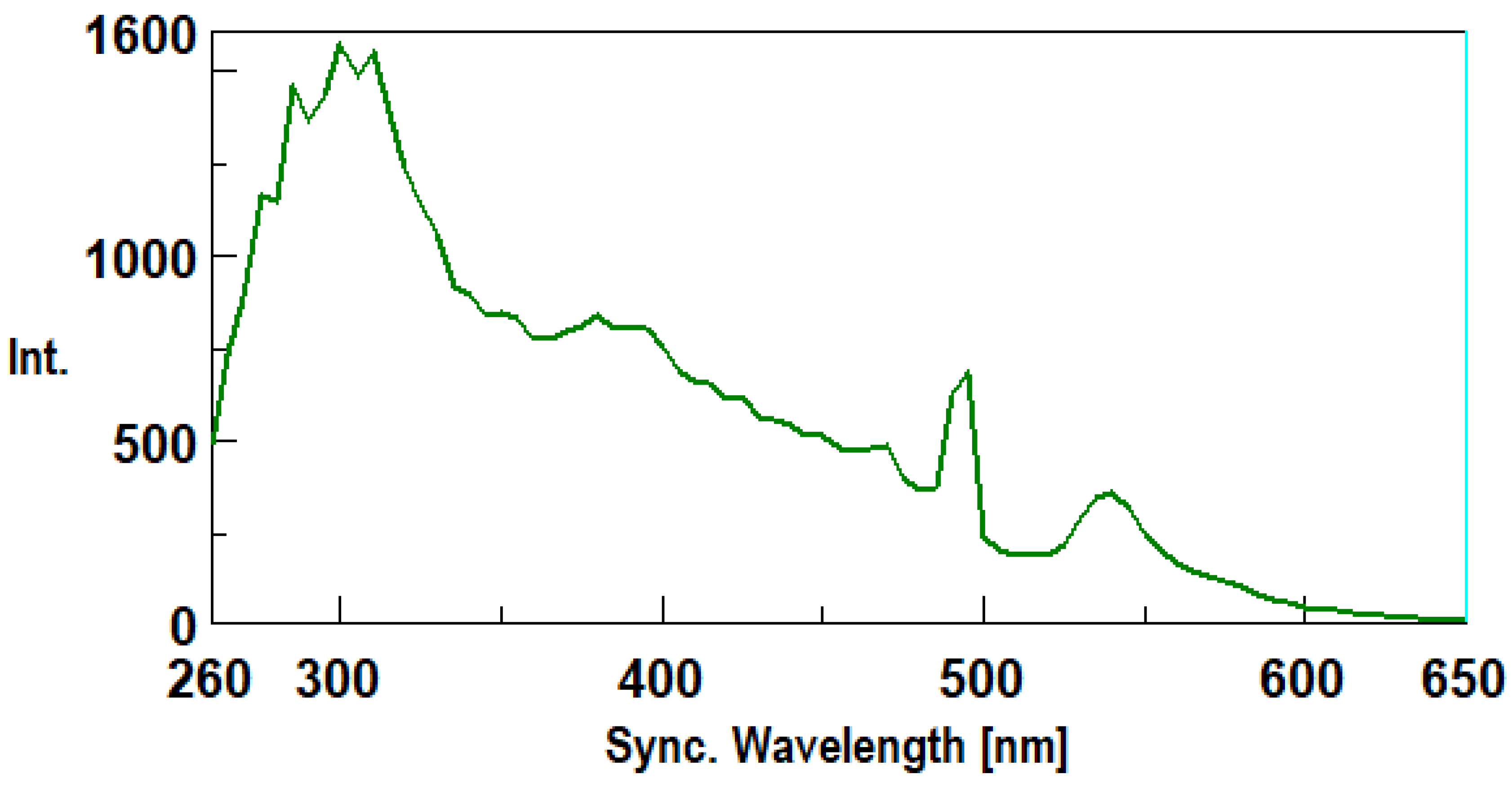

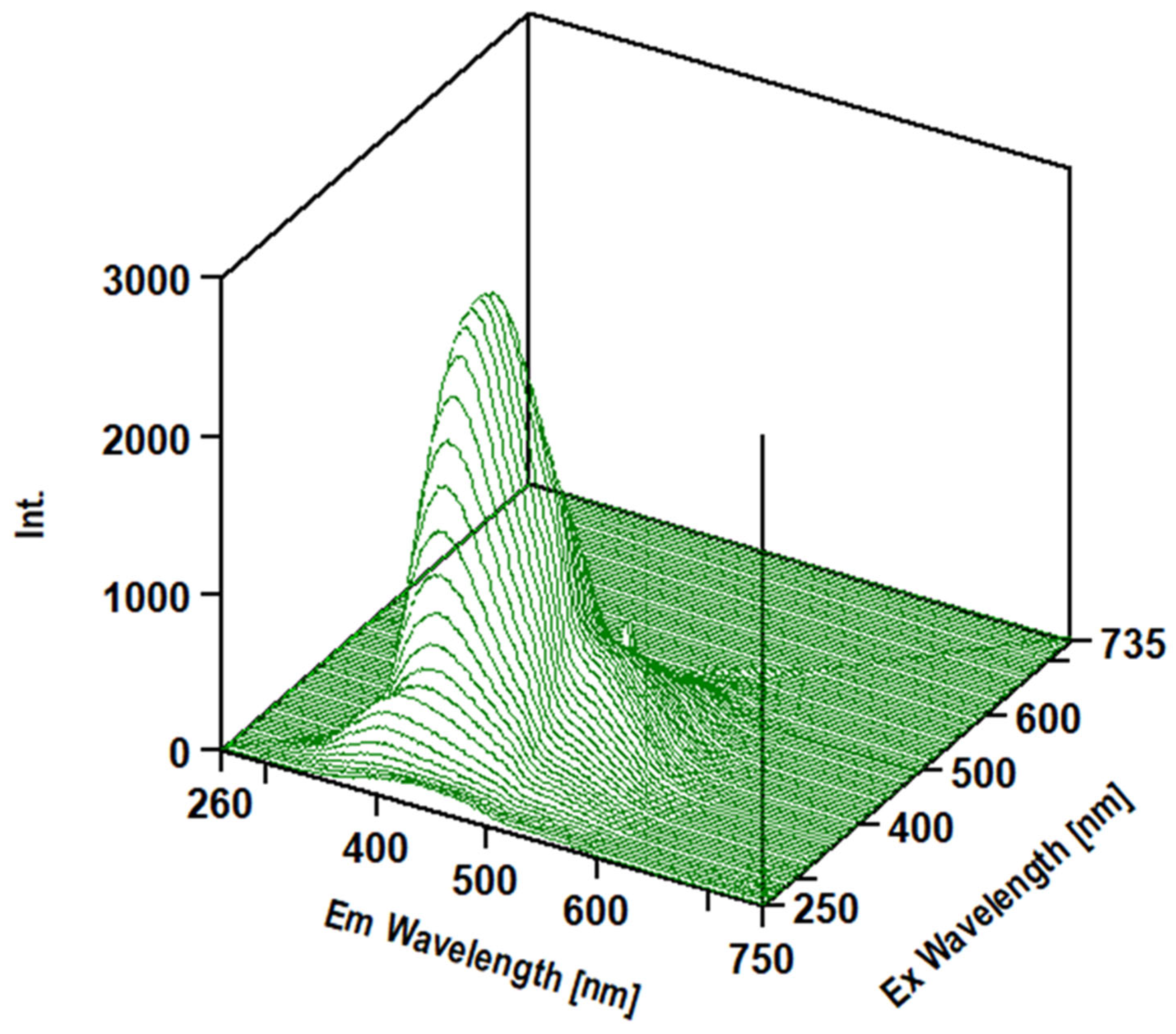

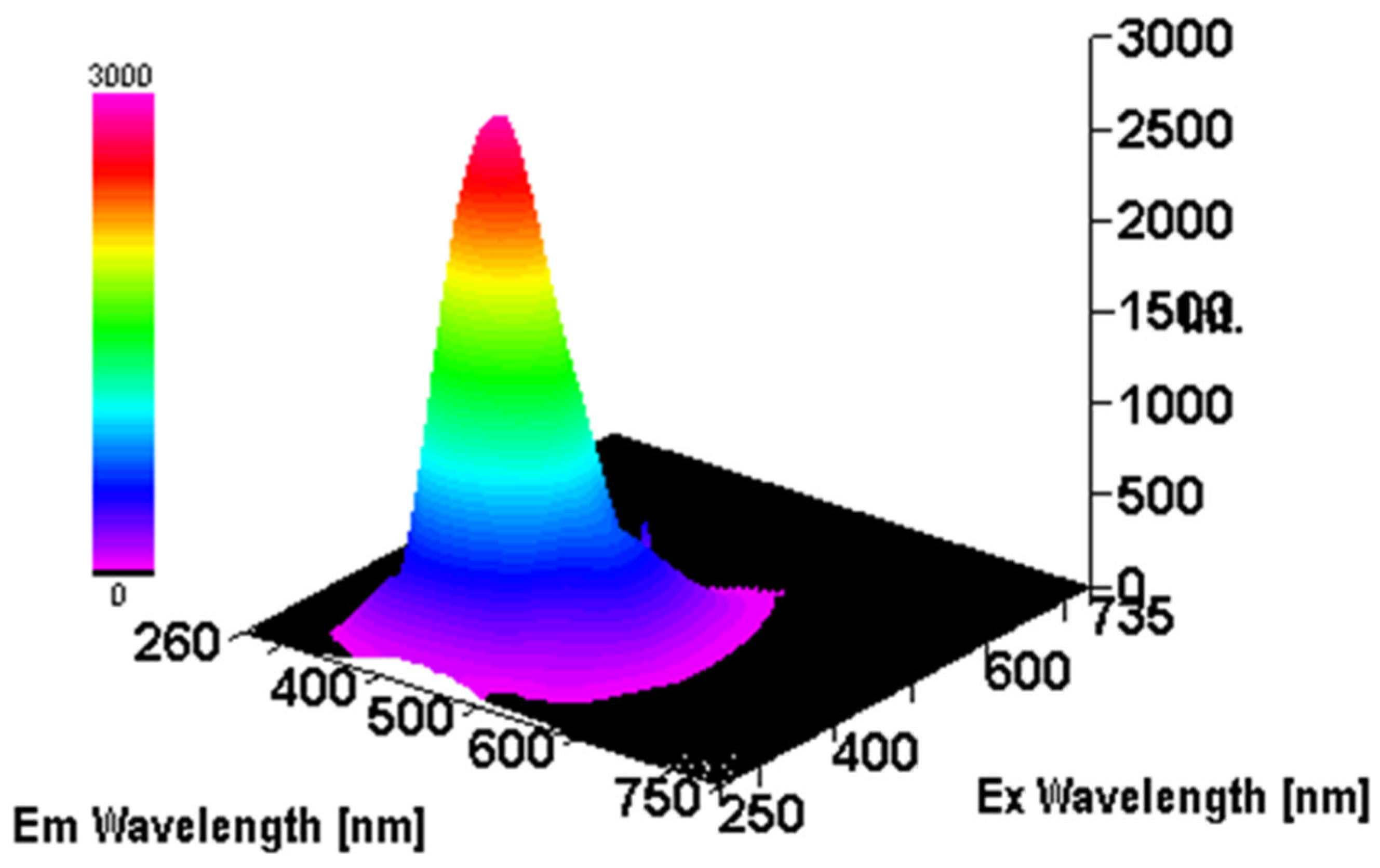

Basidiomycete mushrooms contain complex b-D-glucans which play an important role in immuno-modulating and anti-tumor activities. The present work involves a novel and intrinsic synchronous fluorescent and phosphorescence assay method for b-D-glucans. Synchronous fluorescence and phosphorescence spectroscopy was carried out by a spectrofluorometer in the range of 250 to 750 nm with a Dl range of 5 -30 nm which exhibited peaks at 492, 540 and 550 nm by using b-D-glucan from Euglena gracilis as standard. A micro and high throughput method based on 96-well microtiter plate fluorescence was devised with a excitation and emission l of 420 nm and 528 nm, respectively . This assay method presented several advantages over the published colorimetric methods since it is a non-invasive assay method that requires only 0.97 mg of b-D-glucans in samples, greater sensitivity, speed, assay of many samples and very cheap. b-D-glucans of several mushrooms (i.e Poria coccus, Auricularia auricula, Ganoderma lucidium, Pleurotus ostreatus , Cordyceps sinensis , Agaricus blazei, Polyporus umbellatus, Inonotus obliquee) were isolated by using a sequence of several extractions and quantified by either spectrofluorometer or fluorescence microtiter plate reader. 3-D spectra measurements were carried out of b-D-glucans from medicinal mushroom strains. FTIR spectroscopy was used to study the structural features of b-D-glucans in these mushroom samples.

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Growth and Maintenance Conditions of Mushroom Strains

2.3.2. Production of β-D-Glucan from Basidiomycete Mushroom Strains in Culture Media Containing Agro-Industrial Wastes

2.3.3. Isolation of of β-D-Glucan from Basidiomycete Mushroom Strains

2.3.4. Congo Red Assay for Specific Determination of of β-D-Glucan with Triple Helical Structure

2.3.5. Intrinsic Synchcronous Fluorescence Spectroscopy (SFS) of β-D-Glucans

2.3.6. Intrinsic Fluorescence Measurements of β-D-Glucans in Microtiter Plate Reader

2.3.7. Intrinsic Synchcronous Phosphorescence Spectroscopy (SPS) of β-D-Glucans

2.3.8. Intrinsic 3- d Fluorescence Spectra Measurements of β-D-Glucans

2.3.9. FTIR Analysis of β-D-Glucans

2.3.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

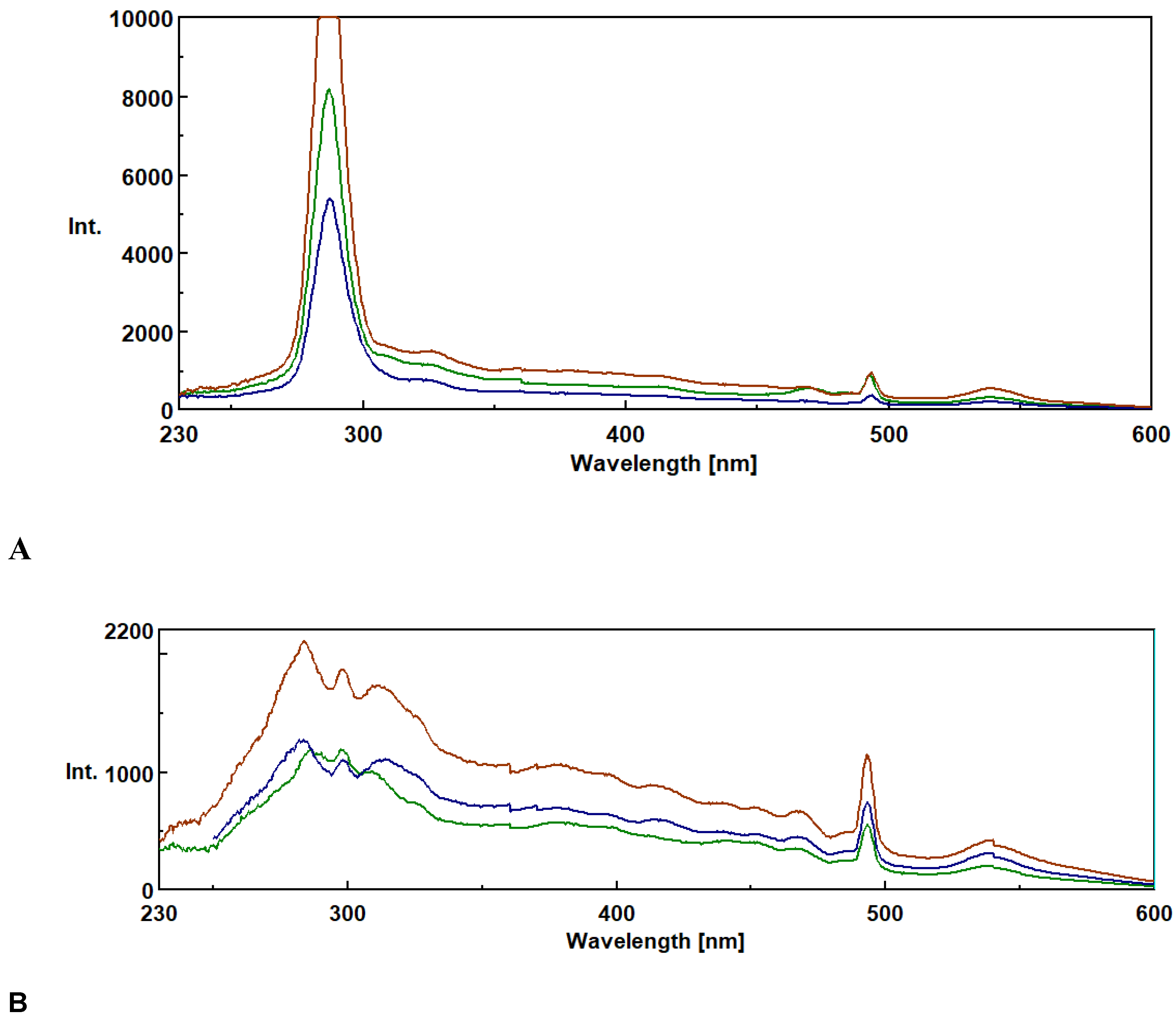

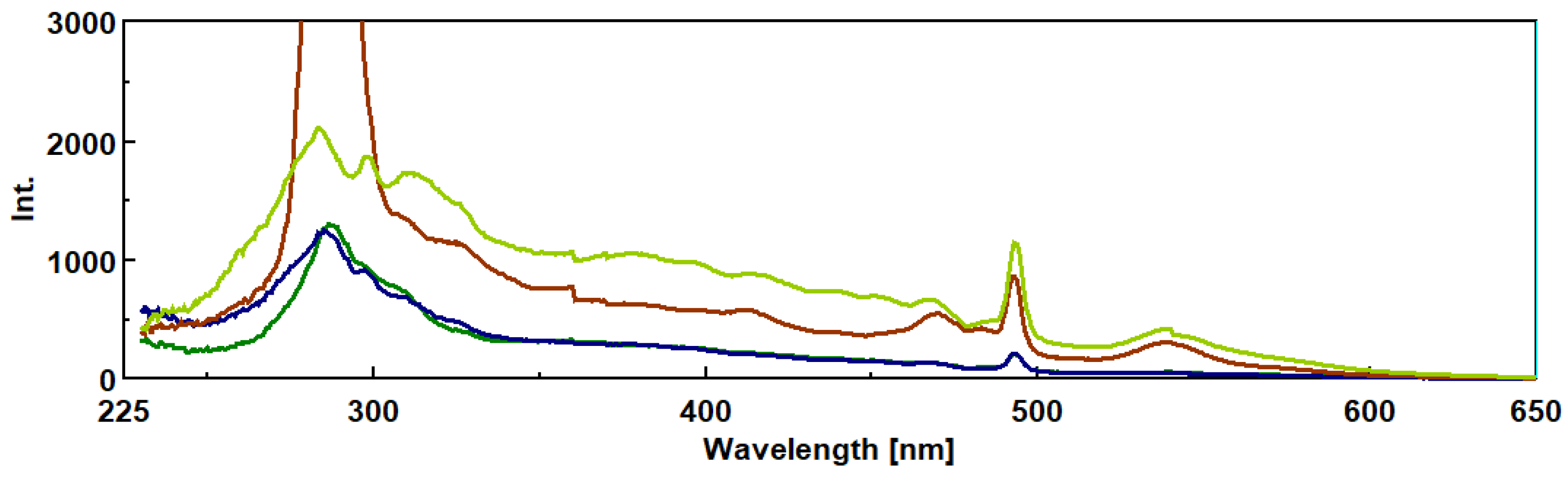

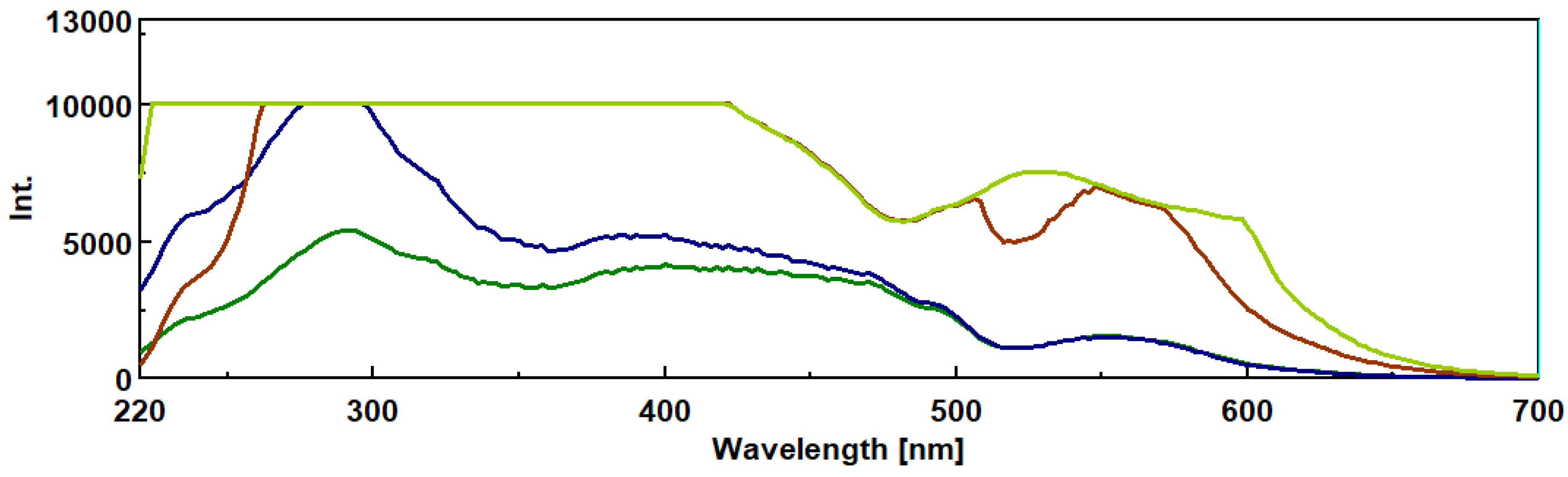

3.1. Synchronous Fluorescence Spectroscopy (SFS)

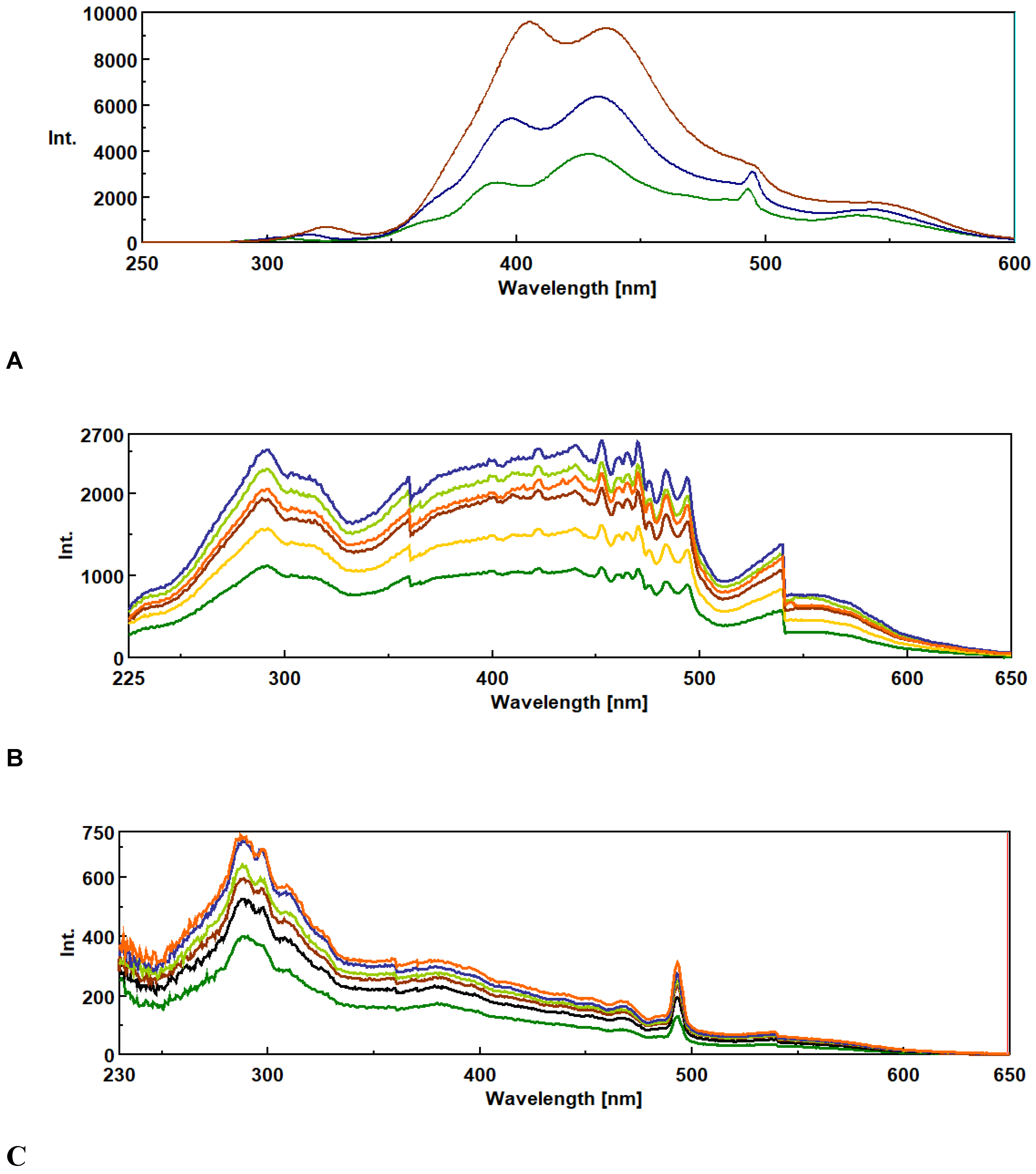

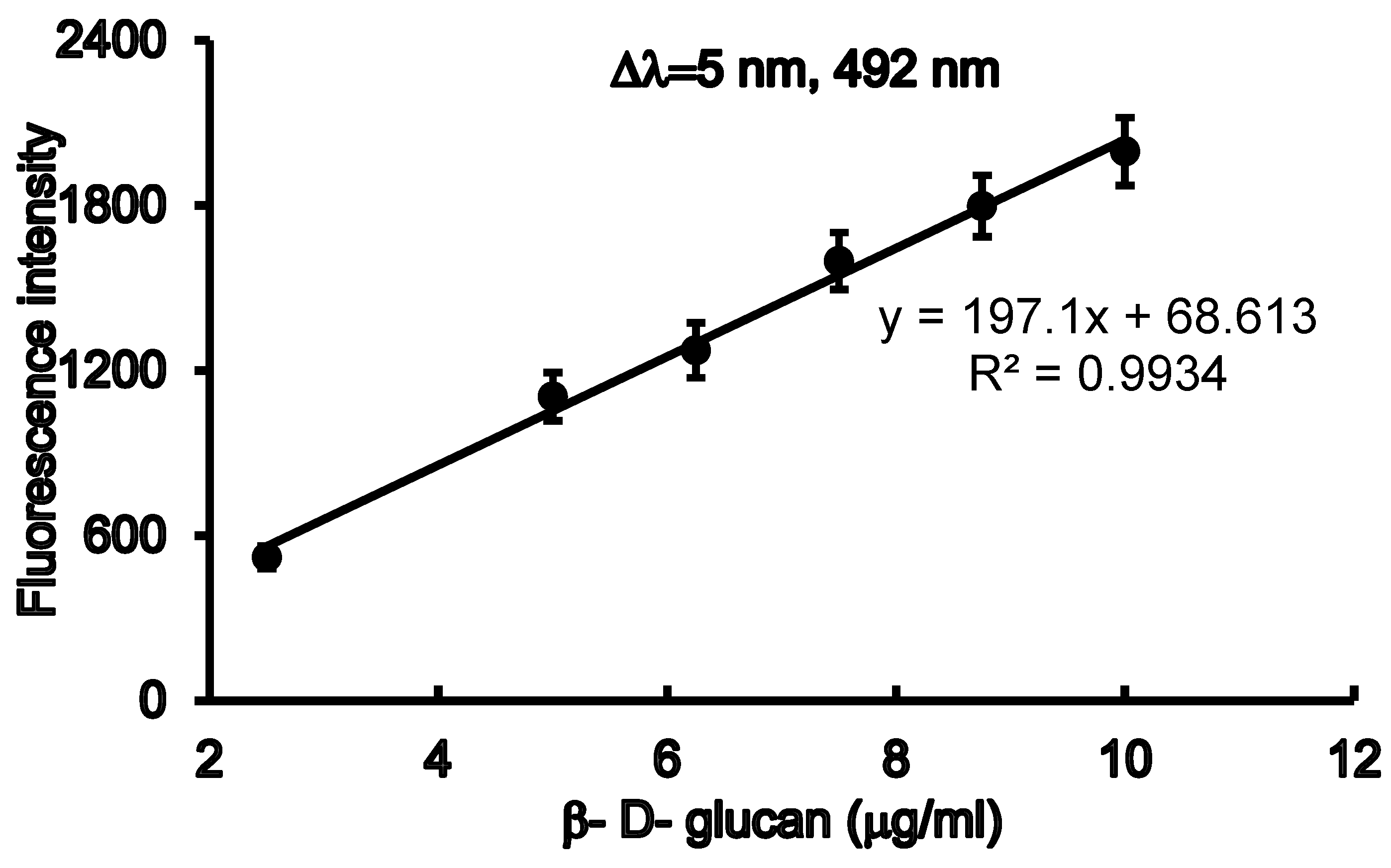

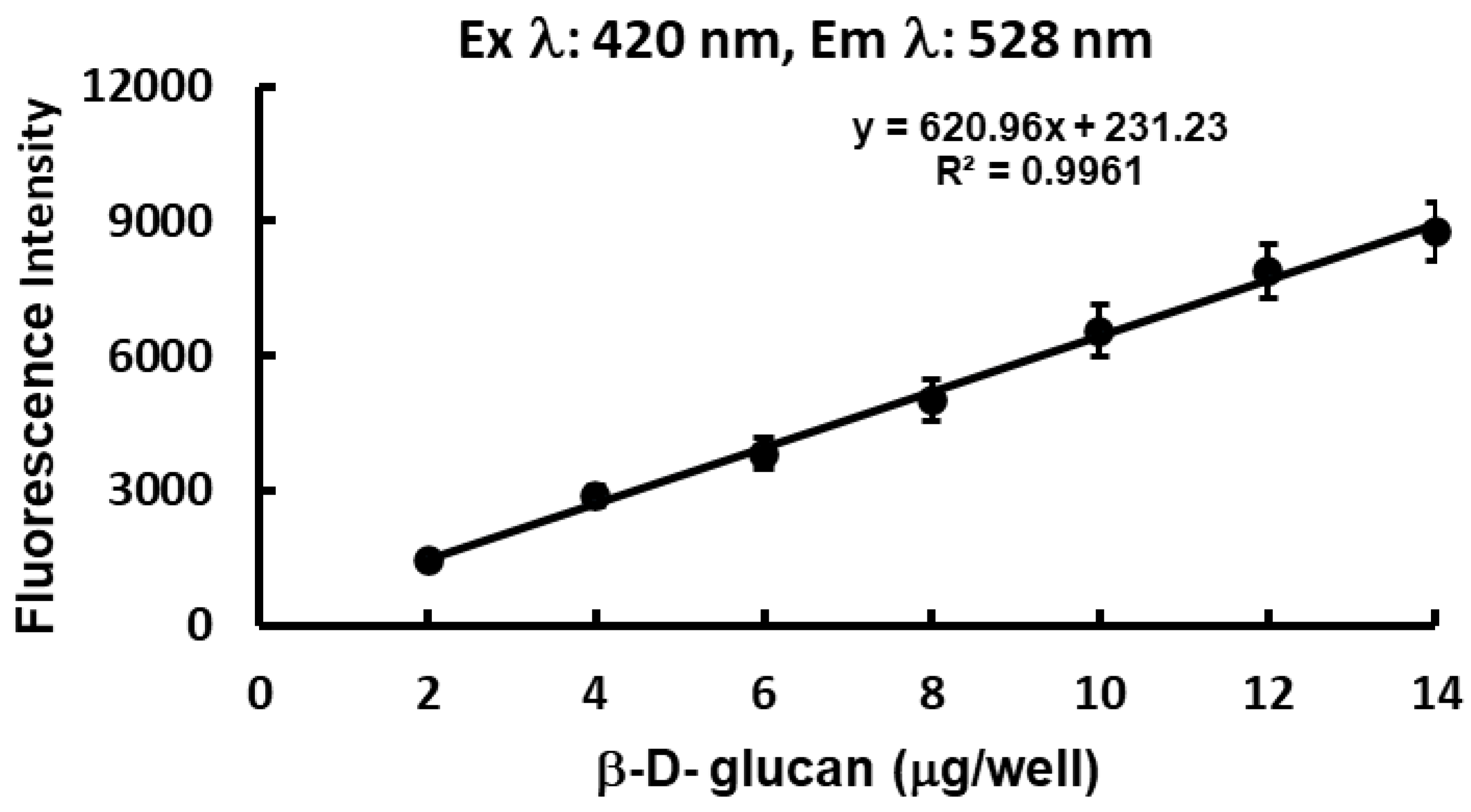

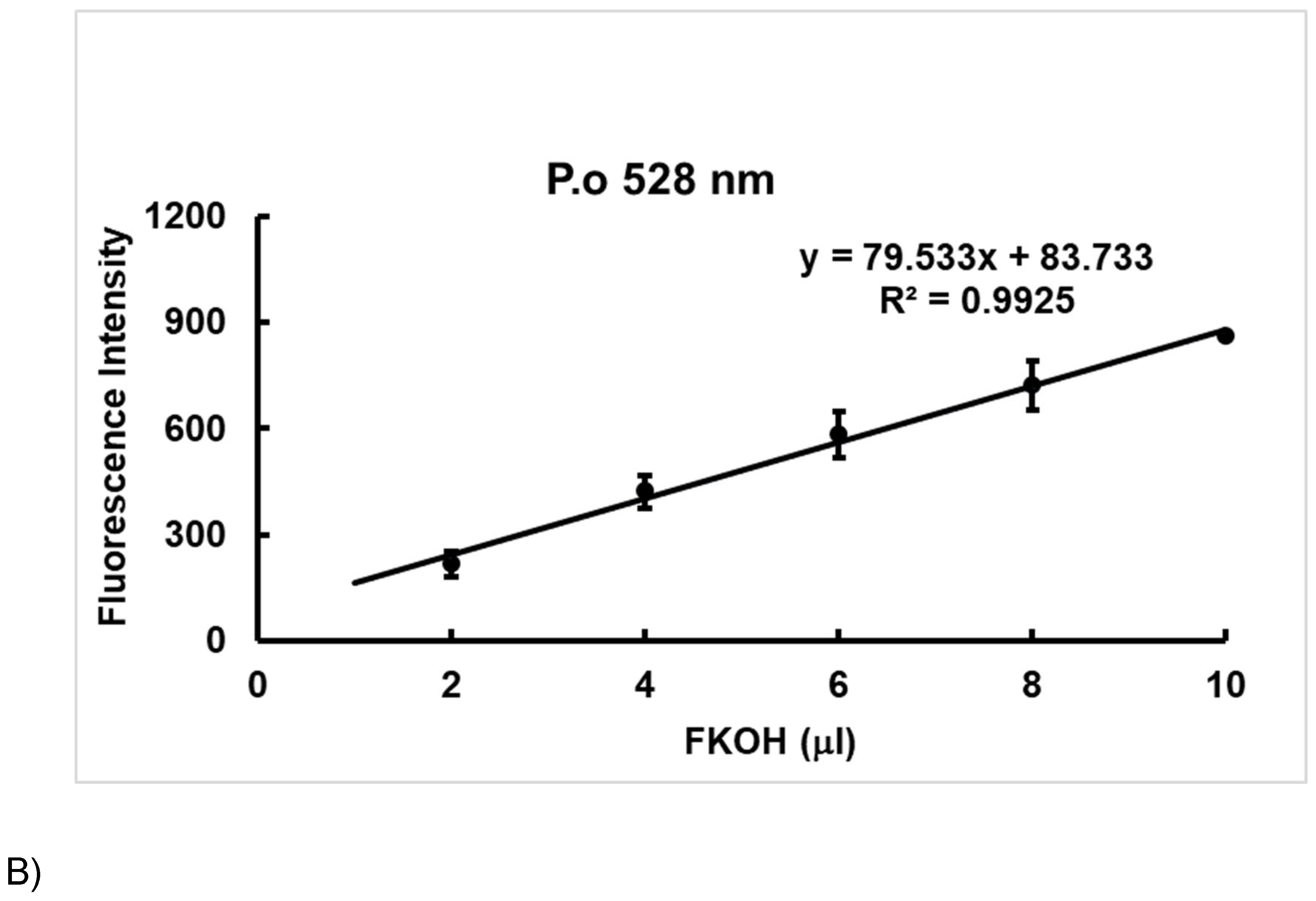

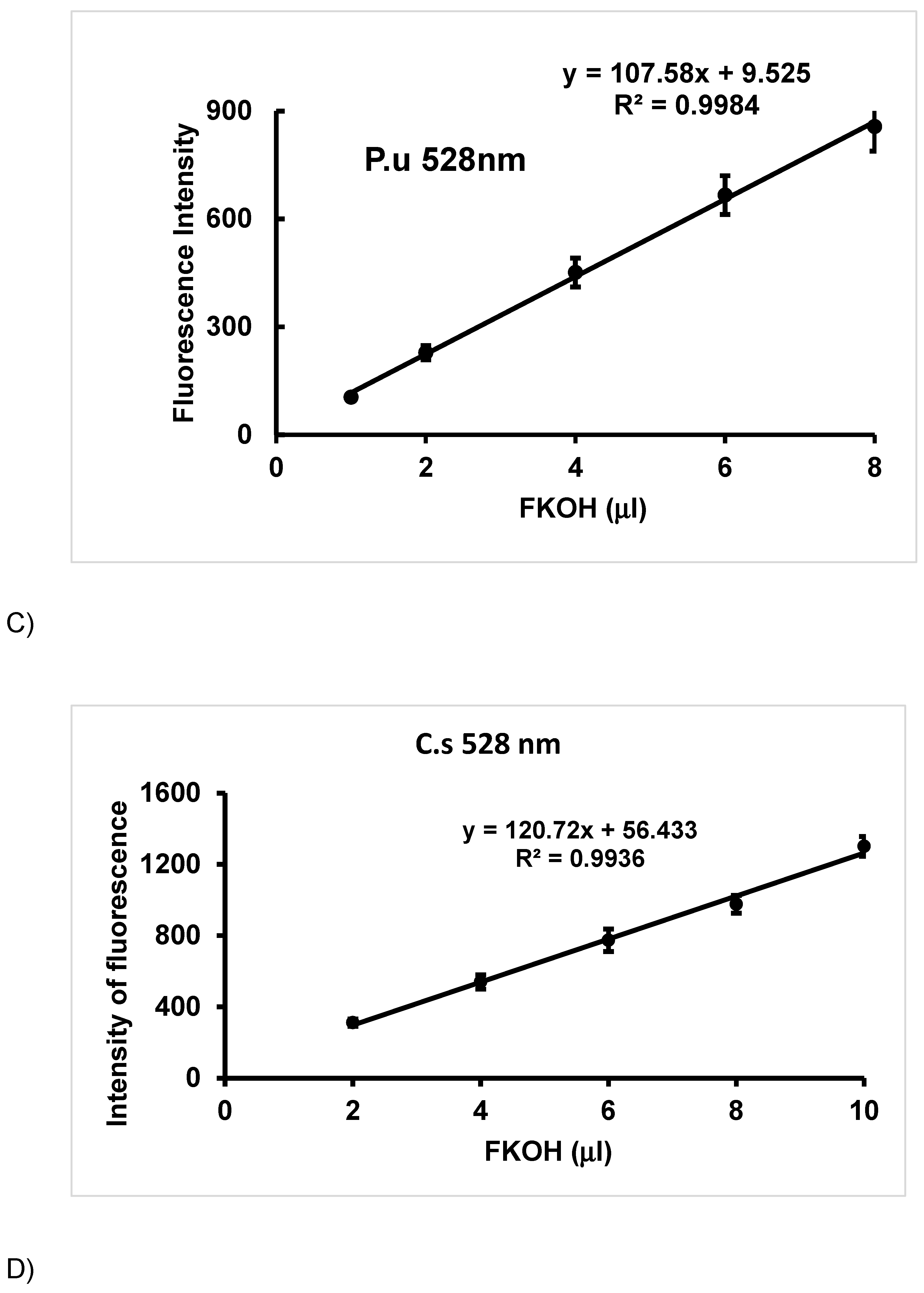

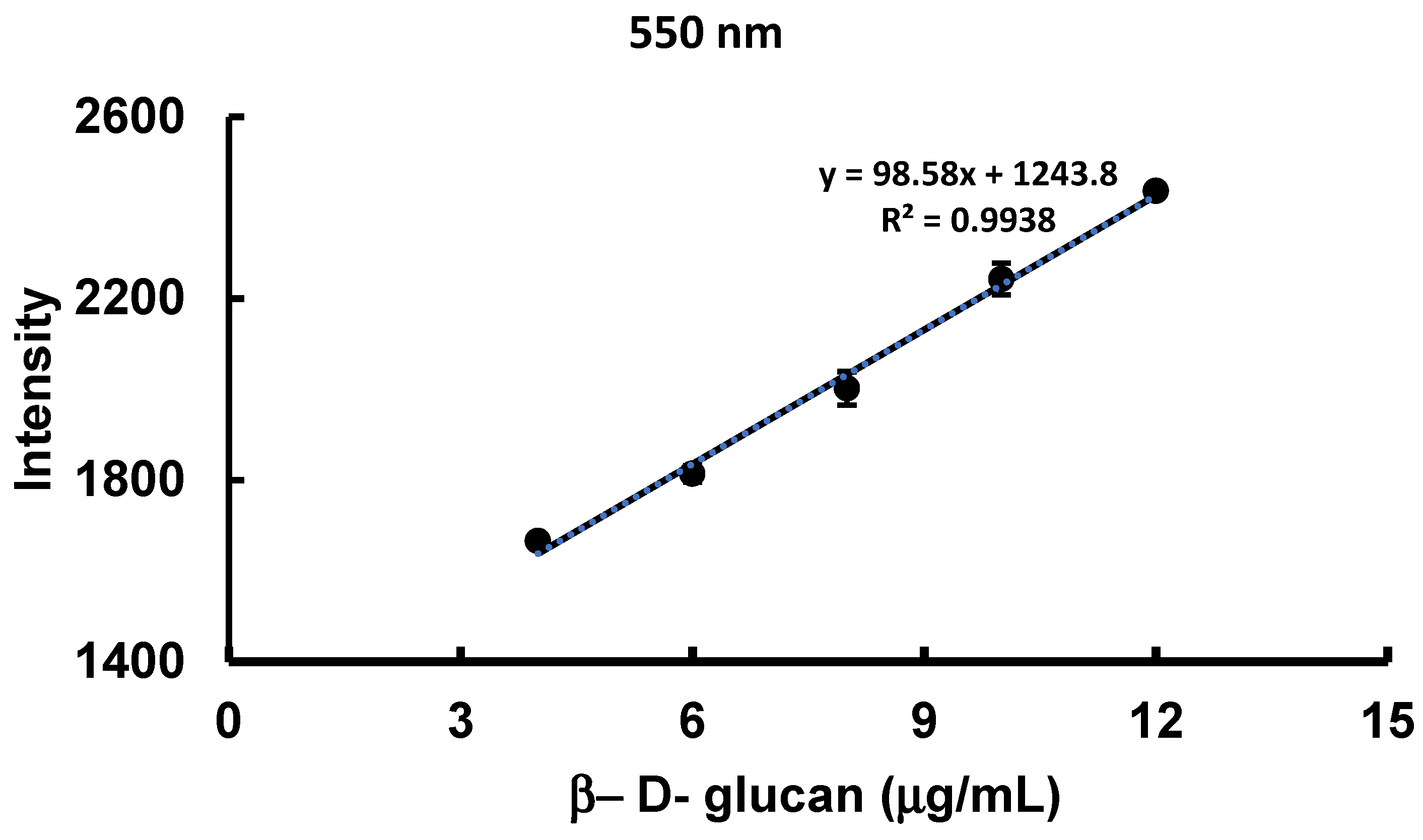

3.2. Method Validation.

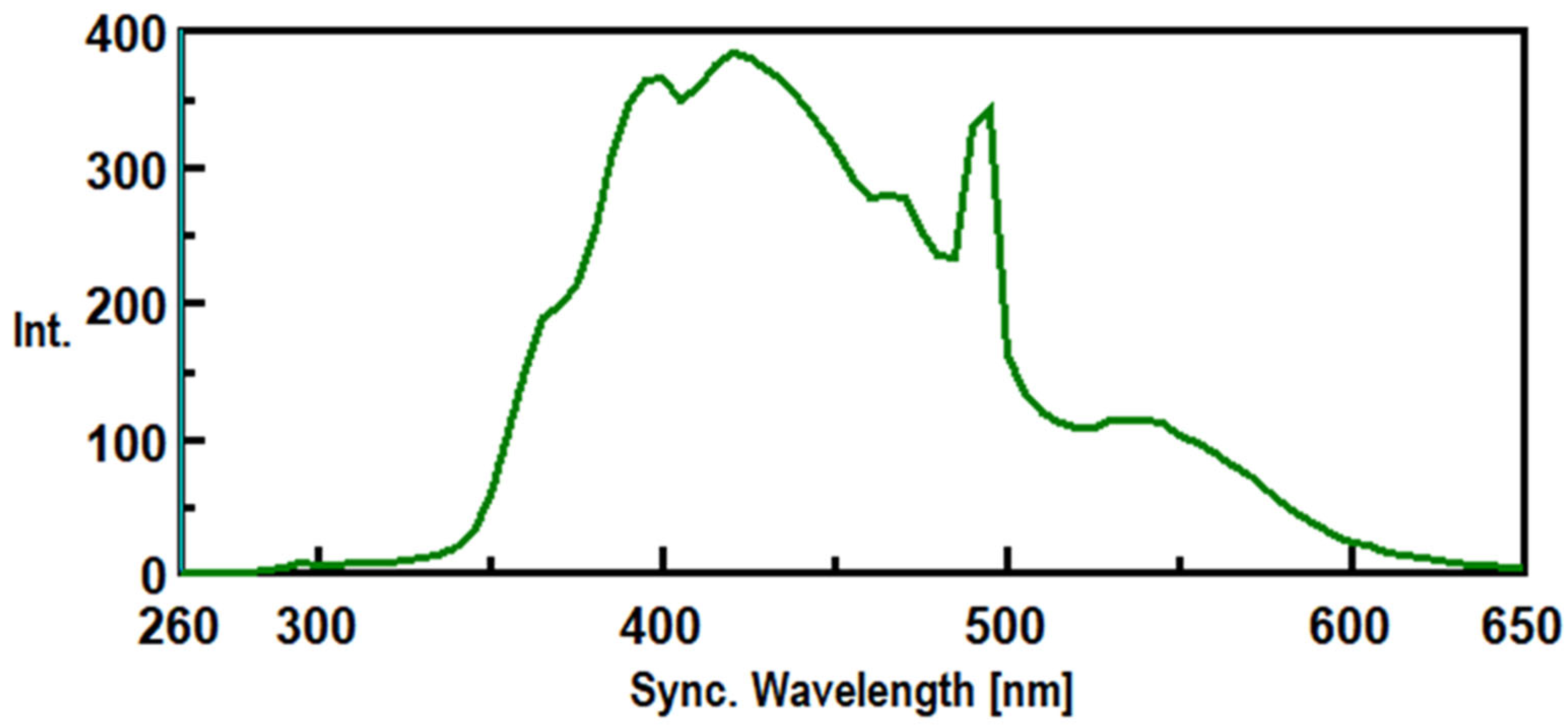

3.2. Intrinsic Synchronous Phosphorescence Spectroscopy (SPS)

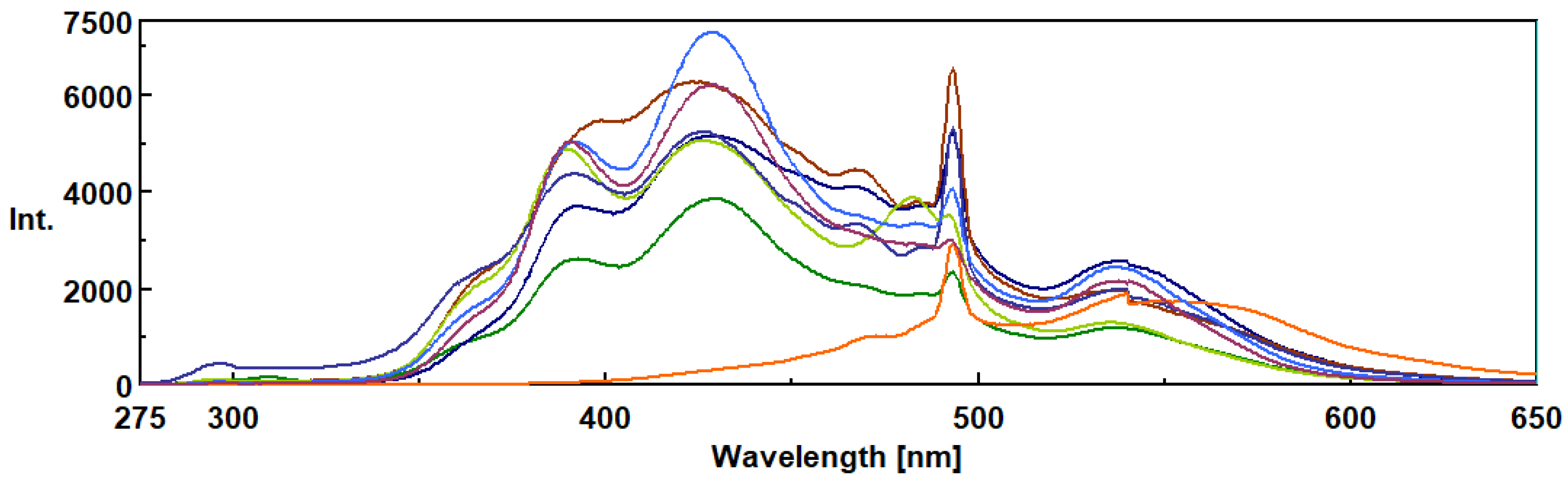

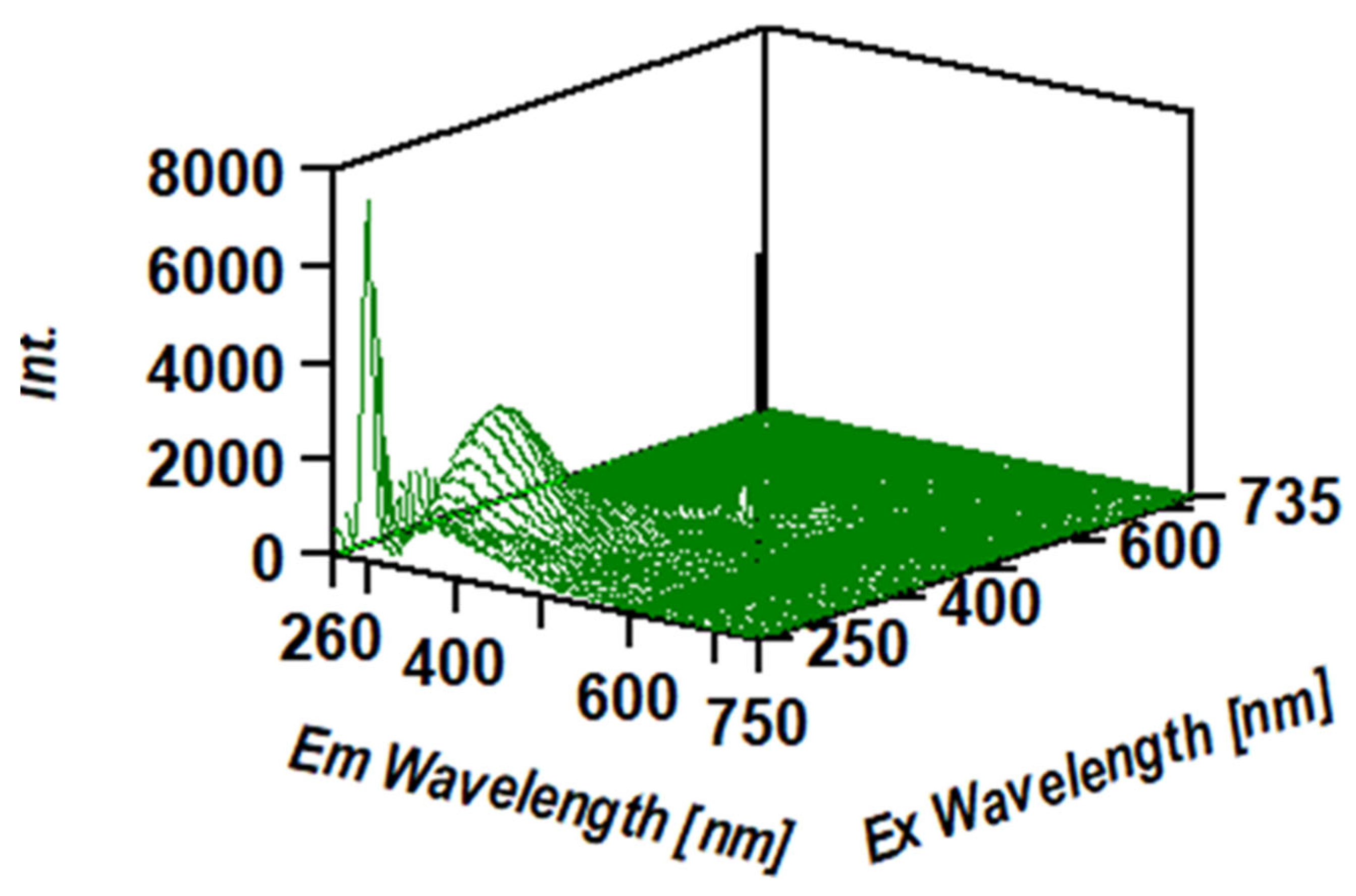

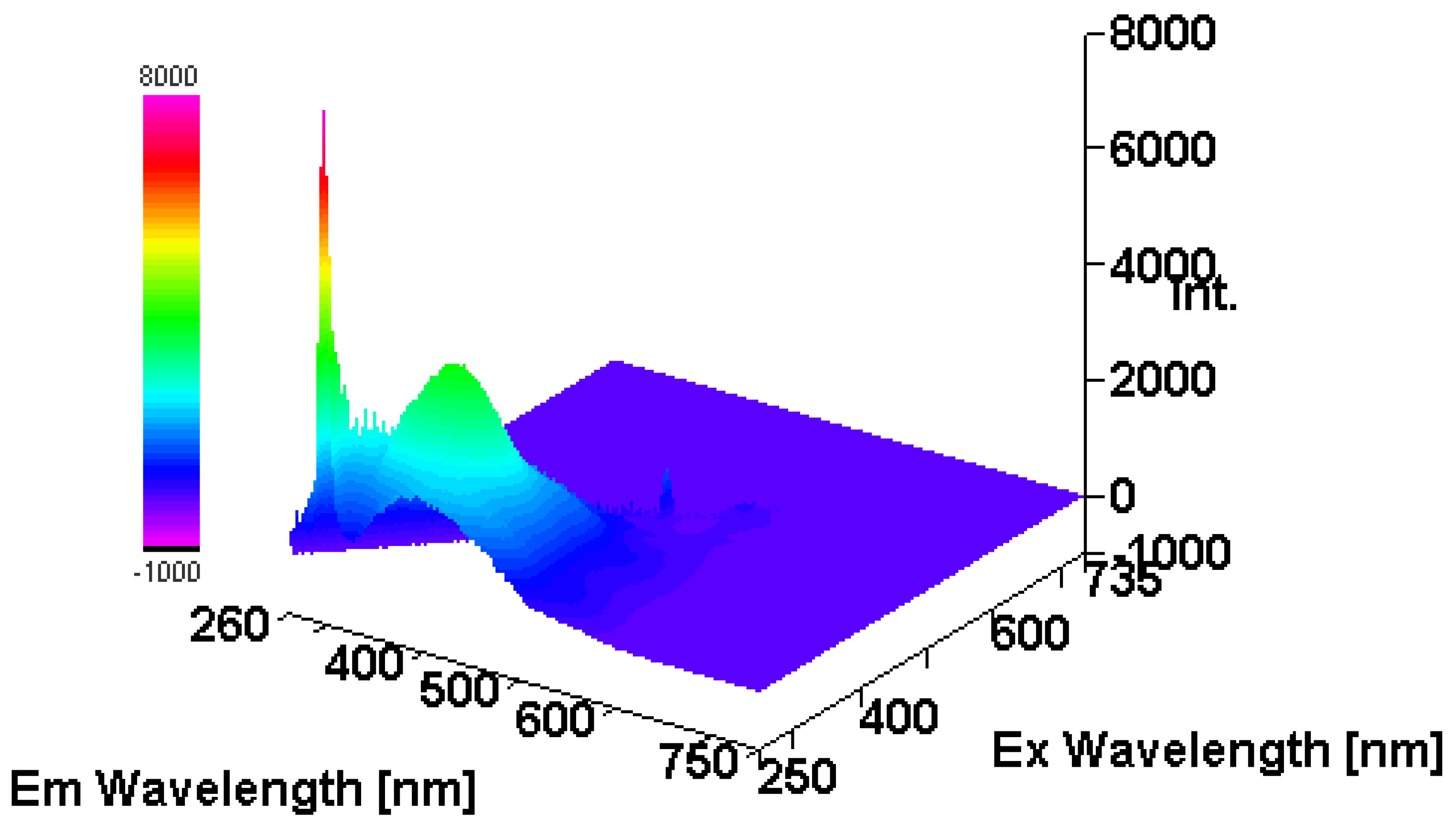

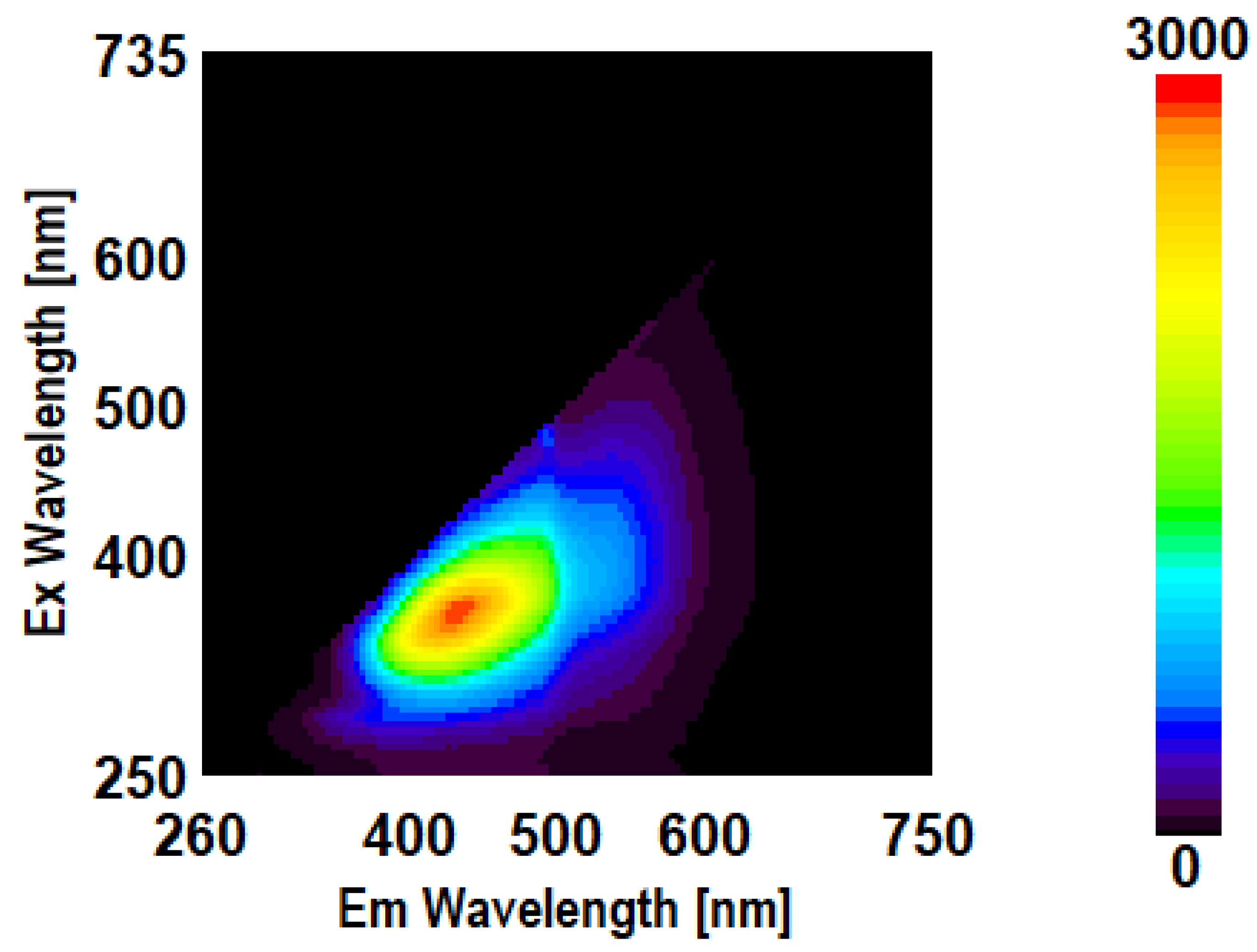

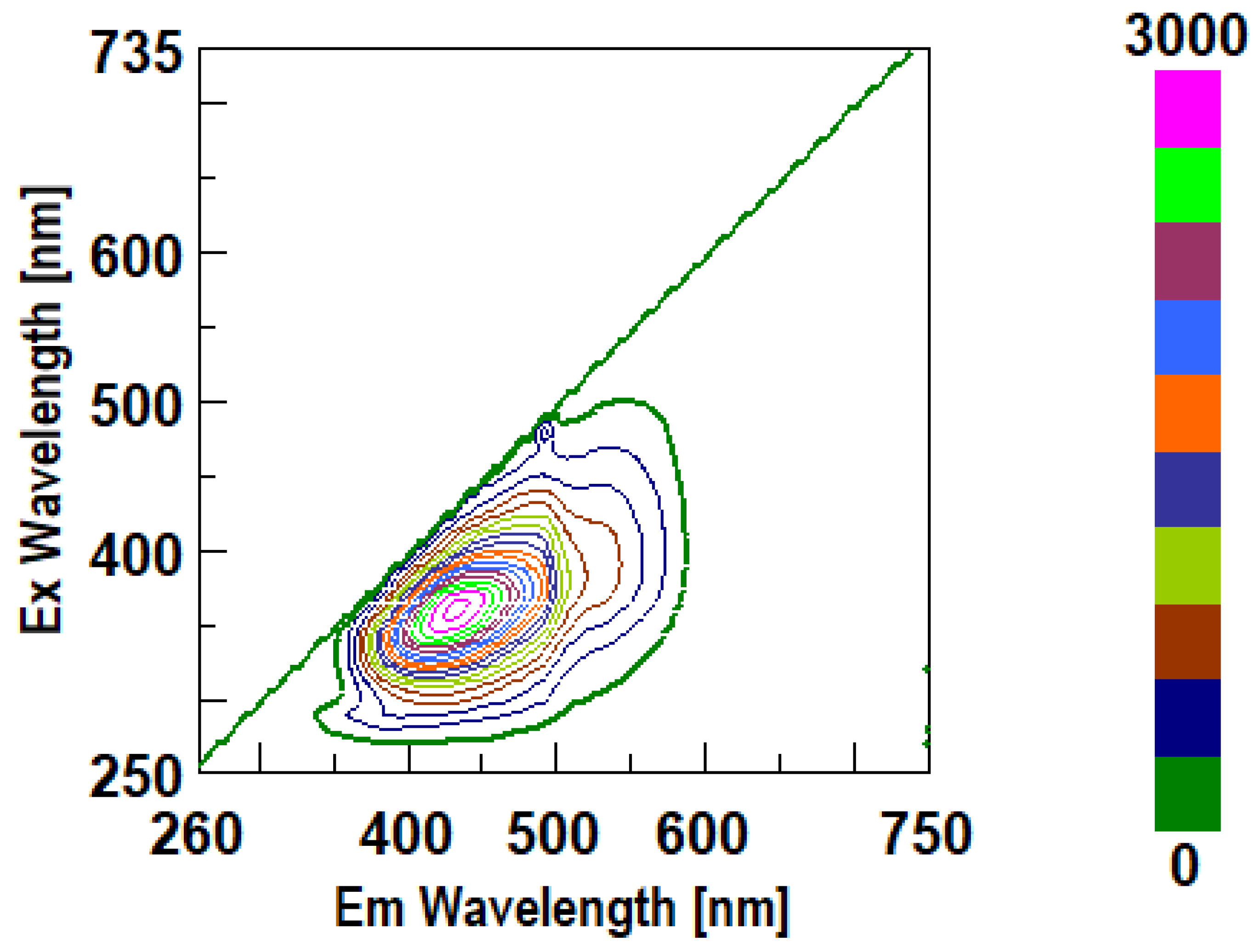

3.3. Intrinsic 3- Dimensional Fluorescence Spectroscopy

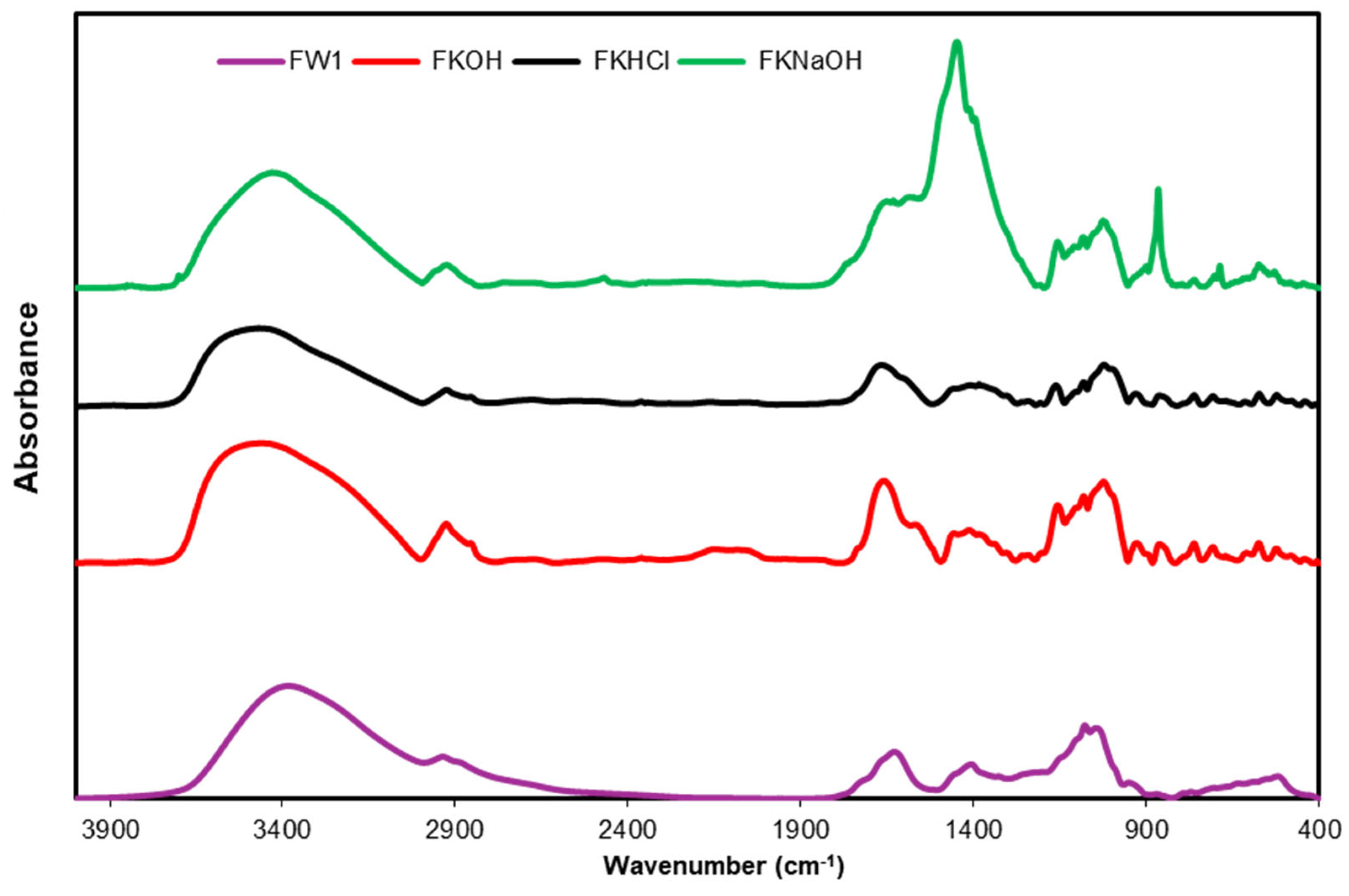

3.4. FTIR Analysis of β-D-Glucans

4. Conclusions

Funding

Author contribution

Conflict of interest

Abbreviations

| BRM | Biological response modifiers |

| EBG | Extracellular β-D-glucans |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| IBG | Intracellular β-D-glucans |

| PDA | Potato dextrose agar |

| SFS | Synchronous Fluorescence Spectroscopy |

| SPS | Synchronous Phosphorescence Spectroscopy |

References

- Lysakova, V.; Streletskiy, A.; Sineva, O.; Isakova, E.; Krasnopolskaya, L. Screening of Basidiomycete Strains Capable of Synthesizing Antibacterial and Antifungal Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambri, A; Srivastava, M; Mahale, VG; Mahale, S; Karn, SK. Mushrooms as Potential Sources of Active Metabolites and Medicines. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 837266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case, S; O’Brien, T; Ledwith, AE; Chen, S; Horneck Johnston, CJH; Hackett, EE; O’Sullivan, M; Charles-Messance, H; Dempsey, E; Yadav, S; Wilson, J; Corr, SC; Nagar, S; Sheedy, FJ. b-glucans from Agaricus bisporus mushroom products drive Trained Immunity. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1346706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.K.; Dutta, S.D.; Ganguly, K.; Cho, S.-J.; Lim, K.-T. Mushroom-Derived Bioactive Molecules as Immunotherapeutic Agents: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindequist, U.; Niedermeyer, T.H.J.; Ju¨lich, W-D. Review The Pharmacological Potential of Mushrooms eCAM. 2005, 2(3), 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B; Baruah, K; Cox, E; Vanrompay, D; Bossier, P. Structure-Functional Activity Relationship of b-Glucans From the Perspective of Immunomodulation: A Mini-Review. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tan, J.; Nima, L.; Sang, Y.; Cai, X.; Xue, H. Polysaccharides from fungi: A review on their extraction, purification, structural features, and biological activities. Food Chemistry: X 2022, 15, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, RM; Mittal, P; MP, N; Arora, T; Bhattacharya, T; Chopra, H; Cavalu, S; Gautam, RK. Fungal Mushrooms: A Natural Compound With Therapeutic Applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 925387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, G.A.; Cusumano, G.; Venanzoni, R.; Angelini, P. The Glucans Mushrooms: Molecules of Significant Biological and Medicinal Value. Polysaccharides 2024, 5(3), 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, K; Sreeja, PS; Yang, X. The Antioxidant Properties of Mushroom Polysaccharides can Potentially Mitigate Oxidative Stress, Beta-Cell Dysfunction and Insulin Resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 874474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradali, M-F; Mostafavi, H.; Ghods, S.; Hedjaroude, G-A. Review Immunomodulating and anticancer agents in the realm of macromycetes fungi (macrofungi). International Immunopharmacology 2007, 7, 701–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.J.; Rezoagli, E.; Major, I.; Rowan, N.; Laffey, J.G. b-Glucans. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 831–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synytsya, A.; Novak, M. Structural analysis of glucans. Ann. Transl. Med. 2014, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Semedo, M.C.; Karmali, A.; Fonseca, L. A high throughput colorimetric assay of β-1,3-D-glucans by Congo red dye. J. Microbiol. Meth 2015, 109, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuko, T.; Minami, A.; Iwasaki, N.; Majima, T.; Nishimura, S.-I.; Lee, Y.C. Carbohydrate analysis by a phenol–sulfuric acid method in microplate format. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 339, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semedo, M.C.; Karmali, A.; Fonseca, L. A novel colorimetric assay of β-D-glucans in basidiomycete strains by alcian blue dye in a 96-well microtiter plate. Biotechnol. Prog. 2015, 31, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, S.; Rühmann, B.; Sieber, V.; Schmid, J. Quantitative assay of β-(1,3)-β-(1,6)-glucans from fermentation broth using aniline blue. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 174, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theint, P.P.; Sakkayawong, N.; Buajarern, S.; Singkhonrat, S. Development of an analytical fluorescence method for quantifying β-glucan content from mushroom extracts; utilizing curcumin as a green chemical fluorophore. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2025, 137, Part A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizono, M.; Minato, K.-I.; Tsuchida, H. Preparation and specificity of antibodies to an anti-tumor β-glucan, lentinan. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 1996, 39, 679–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.; Karmali, A. Experimental Planning for Production of β-D-Glucan: Purification and Fluorescence Properties from Basidiomycete Strains. Separations 2025, 12, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Validation of analytical procedures: Text and methodology, Q2(R1); Geneva. Available online: http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Quality/Q2_R1/Step4/Q2_R1__Guideline.pdf.

- Tian, M.; Muhammad, T.; Li, Y-Q; Fan, X.; Wang, L.; Mi, F.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, J. Application of synchronous fluorescence spectroscopy in the analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in petroleum and coal. Applied Spectroscopy Reviews 2025, 60:7, 611–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdy, G; Belal, F; El-Deen, AK. Green synchronous spectrofluorimetric method for the simultaneous determination of agomelatine and venlafaxine in human plasma at part per billion levels. Sci Rep. 2022, 12(1), 22559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, P.; Zamora, A.; Castillo, M. Synchronous Front-Face Fluorescence Spectra: A Review of Milk Fluorophores. Foods 2024, 13, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez, G.A.; Escandar, G.M. Fluorescence and Phosphorescence Chemical Sensors Applied to Water Samples. In Smart Sensors for Real-Time Water Quality Monitoring. Smart Sensors, Measurement and Instrumentation; Mukhopadhyay, S., Mason, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; vol 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qu, Z. Benchmark Study on Phosphorescence Energies of Anthraquinone Compounds: Comparison between TDDFT and UDFT. Molecules 2023, 28, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Cui, C.; Pan, J. Application of Three-Dimensional Fluorescence Spectroscopy in Smart Agriculture — Detection of Oil Pollutants in Water. International Journal of Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence VOL. 37, NO. 03. [CrossRef]

- Dubayová, K.; Krajˇcíková, K.; Mareková, M.; Tomeˇcková, V. Derivative Three-Dimensional Synchronous Fluorescence Analysis of Tear Fluid and Their Processing for the Diagnosis of Glaucoma. Sensors 2022, 22, 5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Feng, X.; Li, Y.; Lin, X.; Cai, F. Compact three-dimensional fluorescence spectroscopy and its application in food safety. LWT- Food Science and Technology 2024, 202, 116324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, R.; Wu, W.; He, Y.; Wu, X.; Sun, W.; Li, D.; Xiao, Y.; et al. New 3-D Fluorescence Spectral Indices for Multiple Pigment Inversions of Plant Leaves via 3-D Fluorescence Spectra. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozarski, M.; Klaus, A.; Nikšić, M.; Vrvić, M.; Todorović, N.; Jakovljević, D.; Griensven, L. Antioxidative activities and chemical characterization of polysaccharide extracts from the widely used mushrooms Ganoderma applanatum, Ganoderma lucidum, Lentinus edodes and Trametes versicolor. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2012, 26, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mushroom strains | Congo Red dye | Fluorescence assay | |||

| mg/ml | mg/ml | ||||

| Lentinula edodes | 153.25±10.27 | 165.25±9.03 | |||

| Inonotus obliquee | 26.98±1.25 | 24.13±1.05 | |||

| Coriolus versicolor | 169.60±10.71 | 182.76±12.35 | |||

| Agaricus blazei | 166.45±8.97 | 152.87±9.23 | |||

| Ganoderma applanatum | 29.61±1.25 | 27.04±1.64 | |||

| Ganoderma carnosum | 38.2±1.98 | 40.97±1.68 | |||

| Irpex lacteus | 16.79±1.03 | 18.12±1.36 | |||

| Phlebia Rufa | 13.77±1.03 | 15.24±0.98 | |||

| Barley | 12.25±0.85 | 10.97±0.72 | |||

| Emission λ (nm) | 528 |

| Excitation λ (nm) | 420 |

| Gain | 2200 |

| Linearity range (mg/well) | 0 -14 |

| Intercept (a) | 231.23 |

| Slope (b) | 620.96 |

| Correlation coefficient (r2) | 0.9961 |

| % RSD | 0.857 |

| LOD (mg/well) | 0.973 |

| LOQ (mg/well) | 2,919 |

| P- value | 3.16E-07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).