1. Introduction

Relationships between rodents and oak species are affected by a multitude of factors [

1,

2,

3]. Early research into this type of relationship between rodents and oak trees began by considering that rodents only ate and destroyed acorns [

4]. For this reason, rodents were long considered enemies of the reforestation processes carried out by humans through the sowing of acorns [

5,

6,

7,

8]. But we later found that some of the acorns they hoard end up in stashes. [

9] defined two types of storage: superficial ones, which he called caches [

3], and deep ones, which he called larders [

10,

11]. Some of these caches are forgotten, and since the acorns are buried, they can germinate [

12,

13]. This favours plants, meaning that rodents are no longer considered so hostile to the acorn dispersal process. We subsequently verified that some rodent species consume acorns partially because they cannot fit whole acorns in their stomachs due to their small body size [

14,

15,

16]. These species produce remains that they abandon, bury or store, preserving the embryo in a behaviour that they learn over generations and display even if they have had no previous contact with acorns [

16,

17]. This behaviour also benefits plants, as it allows their seeds to germinate after the rodent has consumed part of the cotyledons that serve as reserves [

12,

16]. This relationship, which began as one of predation, is shifting towards collaboration in the dissemination process carried out by oak trees [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Some authors consider that some of these rodent-acorn relationships are very close to a mutualistic relationship [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

In the relationship between rodents and oak trees, the behaviour of rodents is very important, as we can see; consuming acorns on the spot or transporting them, hoarding behaviour, the ability to store acorns, the ability to build larders, and the behaviour displayed to prevent theft from stores [

31,

32]. All these behaviours have a significant impact on the process of acorn dispersal, but so do the characteristics of the acorns produced by oak trees [

27,

34,

35,

36]: the size of the acorns, the thickness of the shells, the synthesis of recalcitrant substances, such as tannins, which deter rodents from eating them [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41], and the nutritional composition of the acorns are characteristics that determine rodents' access to the cotyledons inside them and, therefore, also the way in which rodents handle these acorns and determine the direction of the acorn dispersal process and the participation of rodents in this process [

42].

As we can see, there are many factors involved in the relationship between rodents and oak species and, consequently, in the process of acorn dispersal. In this study, we want to focus attention on a new factor about which there is not much information. Predatory or collaborative relationships are established between two species, in this case rodents and oak trees. But what happens when we introduce a third species that also preys on rodents? [

43]. How does this new predatory relationship with rodents affect the process of acorn dispersal in which rodents participate? [

44,

45].

The factor on which we focus our attention in this experiment is the presence of birds of prey in the branches of acorn-producing trees, which rodents seek out for food [

43]. To do this, we have chosen four species of rodents with different characteristics: Algerian mouse (

Mus spretus Lataste, 1883), wood mouse (

Apodemus sylvaticus Linnaeus, 1758), common vole (

Microtus arvalis Pallas, 1778) and garden dormouse (

Eliomys quercinus Linnaeus, 1766). We have placed them in semi-wild conditions in isolated, wooded plots where we have planted trees with and without birds of prey in their branches and provided them with acorns for food. We used four specimens per rodent species and placed them in four semi-wild plots, one specimen per plot.

Common vole has recently arrived in the study area, the central plateau of the Iberian Peninsula, from the mountains of northern Spain, following the expansion of irrigated crops [

46]. It inhabits agricultural areas and grasslands. It has not been found in forest areas. In this experiment, we have forced rodents of this species to occupy a habitat that is unusual for them, but this allows us to test their reaction in this new situation. We will use it as a control species because it is not accustomed to being attacked by nocturnal birds of prey from the treetops, as it does not inhabit forest areas. Nor does it usually feed on acorns, as its food source is tender, green, fresh grass, but in previous studies we have already shown that it also consumes them for their nutritional value [

15,

17].

Wood mice, Algerian mice and garden dormice have inhabited the Iberian Peninsula since the Pleistocene and Holocene [

47,

48,

49]. These three species of rodents inhabit wooded areas with varying densities of trees, so it is likely that they have had previous negative experiences with nocturnal birds of prey lurking in the lower branches of trees and bushes.

Our primary objective in conducting this experiment is to determine whether the acorn transport process carried out by certain rodent species is paralysed or reduced by the presence of nocturnal birds of prey in the treetops where the rodents’ collect acorns, and whether their acorn dispersal activity is altered by the presence of birds of prey [

43]. If the difference in activity under trees with and without birds of prey were significant, it would indicate that the third species, the bird of prey, due to the predatory pressure it exerts on rodents, would interfere with the collaborative relationship that some of these rodent species maintain with oak species through the dispersal of their acorns [

50].

Of the rodent species, we have already verified in previous studies that wood mice and Algerian mice actively participate in the process of acorn dispersal, both by transporting acorns and by storing them and partially consuming them while preserving the embryo [

17,

50]. We have also verified that the common vole does not participate in this process, which is why we use it as a reference species. We want to verify its reaction to the presence of birds of prey in the trees. However, we have no knowledge of the garden dormouse's handling of acorns and its participation in their dispersal, but it has occupied the same habitats as the wood mouse and Algerian mouse for a long time [

47,

48,

49].

Our second objective is to test the hypothesis we have proposed: the presence of birds of prey in the branches of trees may be one of the reasons why rodents begin to transport acorns, thereby collaborating in the process of dispersing them. Fearing the actions of birds of prey, rodents would move acorns from where they found them to more protected places covered by branches and scrub, which would prevent predation by birds of prey [

11]. This fear and the characteristics of acorns, the barriers that plants put in place during their production, are believed to be the origin of the collaborative relationship that some rodent species have with oak trees.

To test this second hypothesis, we will track the final fates of acorns. We want to know if any of these rodent species process the acorns in protected areas to avoid the action of birds of prey [

11,

43]. By collecting the remains of processed acorns, we can also learn how to open acorns, whether the embryo is preserved, or whether each species of rodent consumes the entire acorn. Although we have previous experience in these areas, this experiment will allow us to observe the behaviour of the garden dormouse and corroborate results [

50].

2. Materials and Methods

In September 2024, we captured four specimens of each of the following four species in a forest dominated by Quercus ilex and Quercus faginea in the vicinity of Palencia (Spain): Algerian mouse, wood mouse, common vole, and garden dormouse. In this same forest, we selected four 100 m² plots (10 x 10 m). We isolated the plots with a metal fence to prevent large ungulates from entering. To prevent rodents from escaping, the perimeter inside the fence was covered with 2 m high metal sheeting. Of the 2 metres, 50 cm were buried vertically to prevent rodents from leaving the enclosure by building tunnels. The rest of the sheet metal, 1.5 m high, protruded above the ground to prevent the wood mice from escaping by jumping over it. These mice can jump very high because their hind limbs are highly developed.

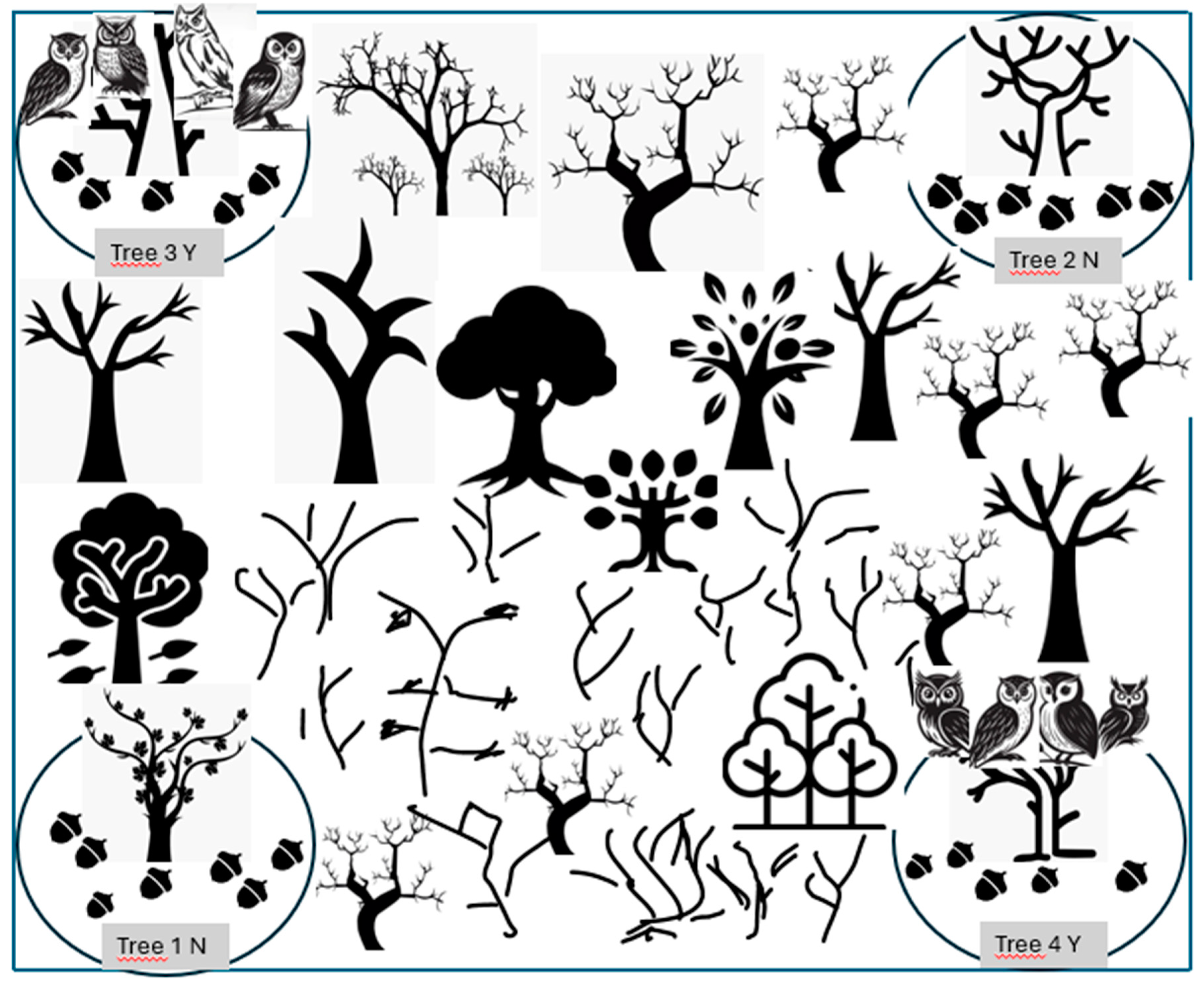

Within each of the four plots, several specimens of Quercus ilex and Quercus faginea were randomly distributed (between 25 and 35 specimens of each species). The tallest specimens were 3 m high in both species, and the shortest were 70 cm high, forming part of the undergrowth. With this density, the rodents could not see the edges of the plot or beyond the trees surrounding it in each position. Within each of the four plots, at the four corners, we selected a tree regardless of species, the one closest to the corner, to separate them as much as possible from each other. Under the canopy of these four trees selected per plot, we remove all types of grass, stones, branches, or roots that could provide shelter for rodents. This area was circular in shape and extended from the trunk to the edge of the crown. On this cleared area, 30 cm from the trunk, we placed the acorns as if they had recently fallen from the tree (

Figure 1). The acorn species chosen was

Quercus ilex, because it is the dominant species in this forest and in the region, and it is also the species preferred by rodents [

15,

17]. Before placing the acorns in an orderly fashion so that any missing ones could be quickly identified, they were labelled for identification purposes by attaching a plastic tag with the appropriate numbering, secured with a wire that pierced the cotyledons in the middle of the acorn. These tags were used to track the final destinations of these acorns or their remains once they had been moved.

On each plot, we chose two of the four selected trees (those occupying the opposite diagonal corners) to place four dolls on the branches closest to the ground, imitating the shape and characteristics of nocturnal birds of prey, like scarecrows used to prevent birds from eating the fruit (

Figure 1). We chose nocturnal birds of prey because all four species are nocturnal feeders. Only the common vole is also active during certain times of the day. The placement of these figures helps us in the experiment to compare the behaviour exhibited by the four species of rodents under these two trees with that exhibited under the two trees that do not have these nocturnal birds of prey figures. We aim to verify the influence of these birds of prey on the behaviour of rodents during the handling of acorns and their possible impact on the process of dissemination of these acorns by rodent species. The experiment lasted 15 days for each rodent species. After the 15 days corresponding to one species had elapsed, we proceeded to capture the specimens occupying the plots and replaced them with specimens of another species to start a new 15-day cycle. The total duration of the experiment was 2 months.

Every day, we provide each of the four specimens of each rodent species with 60 labelled acorns, distributed as follows: we place 15 acorns under each of the four selected trees, located at the four corners of the plot, two with birds of prey and two without birds of prey. The maximum number of acorns consumed in one night by the most voracious species (the largest garden dormouse) is six. For this reason, we chose 15 acorns per tree, because we did not want to run the risk of altering the rodent's behaviour by having to search for food under another canopy due to a shortage of acorns under one tree. Each specimen of each rodent species had 60 acorns per day for 15 days, a total of 900 acorns. 900 acorns per 4 specimens of the species, each species had 3600 acorns.

Every day we checked the number of missing acorns, replaced those that had been eaten, and searched the plot for the place where the acorns had been moved or the place where they had been eaten, collecting the abandoned remains. To carry out this work, we draw on our previous experience from various projects in which the final destinations of the acorns are: consumption on site, abandonment of acorns on the ground surface, deposits of a small number of acorns buried shallowly under leaf litter or a few centimetres below the surface, known as caches [

9], in deposits consisting of a larger number of acorns placed at a greater depth (between 10 and 20 cm) formed by galleries and resting burrows and pantries called larders, according to the terminology used by [

9]. As a single mouse cannot carry out the excavation necessary to build the larders in 15 days, we have proceeded to imitate these pantries by burying cylindrical plastic containers 20 cm in diameter, connecting their interior to the surface of the soil by means of an 8 cm diameter rubber tube. We have used them for this purpose in previous projects, and they have been effective, as the mice have used them to store the acorns they have collected with great frequency.

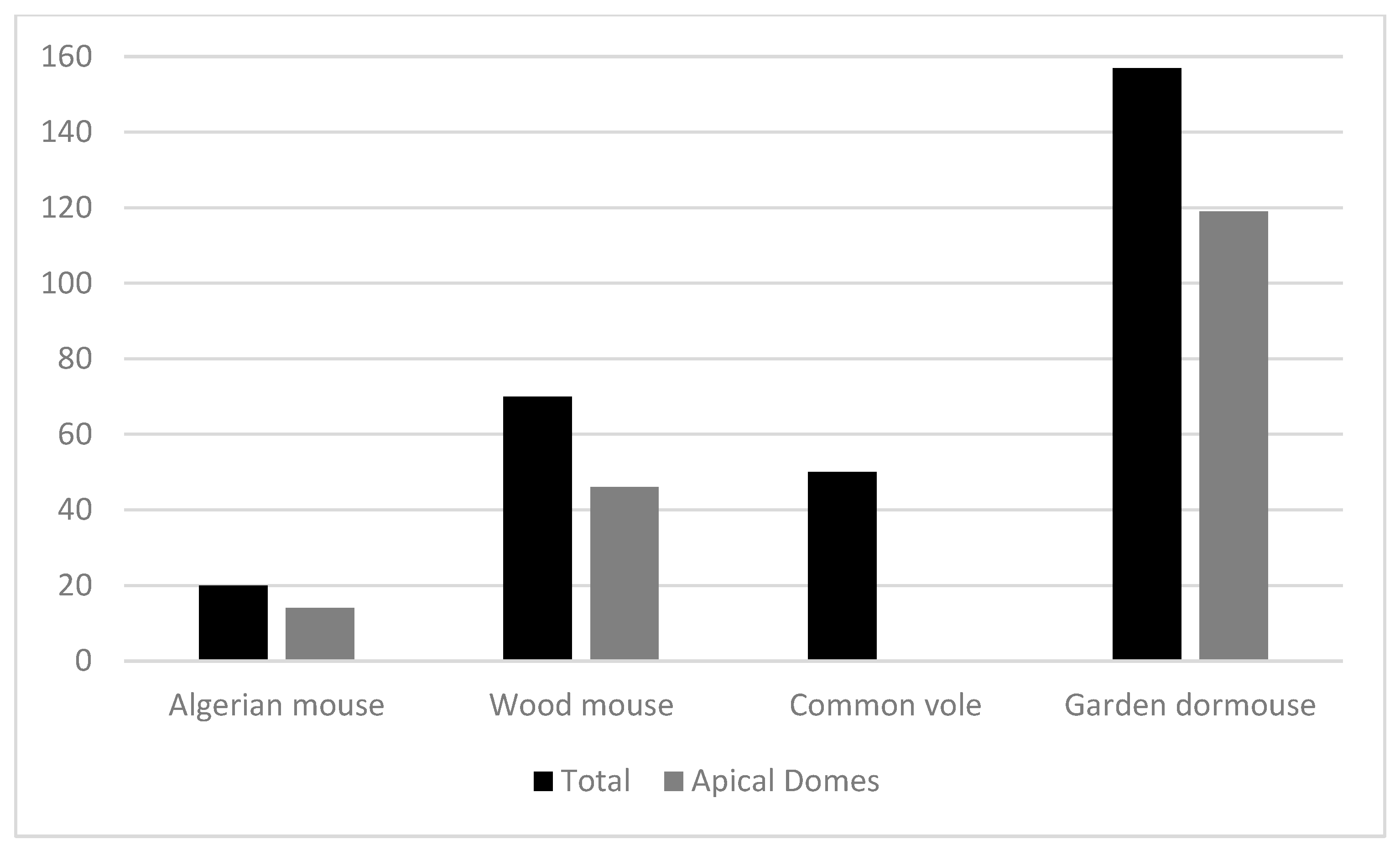

To answer the question posed in the second objective, could the presence of birds of prey in the branches cause rodents to transport acorns? we have differentiated the position of the deposits, the places where the acorns were deposited, into two types: those that remained under the protection of branches and scrub, where birds cannot reach them, and those that remained in open places without the protection of branches or scrub. With this difference, we aim to determine whether rodents transport acorns out of fear to protected places to process them and escape the predatory pressure of birds of prey, or whether, on the contrary, birds of prey have no influence on the transport of acorns. When collecting the remains of the acorns consumed, we verified, as we had done in previous studies [

50], that wood mice and Algerian mice consume acorns partially and leave behind the apical part of the acorn containing the embryo, as these species tend to preserve the embryo until the end, when they consume the acorns completely. However, we did not know how garden dormice behaved when handling acorns. We have observed that it also opens most acorns at the basal end, preserving the embryo until it consumes them completely. As most acorns processed by this species are consumed entirely, it destroys the embryo in the same way as the Common vole. However, what remains are empty apical domes without cotyledons or embryos (

Figure 2). We have therefore collected data on the number of empty apical domes left by each species to verify the influence of each rodent species on the germination potential of the acorns attacked (

Figure 3).

Data Analyses

The possible effects of tree type (with or without birds of prey), rodent species and elapsed time, as well as their interactions, on the number of acorns moved and consumed were analysed using linear mixed models (LMM) with the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method. Each individual per species was treated as a random factor and time as a repeated factor. Finally, working on the model matrix, contrasts were performed to test for differences between levels of fixed factors [

51]. Consequently, Bonferroni correction was used to adjust the significance level of each t-test [

52]. Statistical calculations were performed in the R software environment (version 2.15.3; Core Team R 2013), using the nlme package for LMM [

53].

To test the influence of rodent species, oak species and habitats on the mass of acorns consumed, we performed two two-way factorial ANOVAs. In one, we compared the influence of oak species and rodent species on the mass consumed, and in the other, we compared the influence of rodent species and habitats on the mass of acorns consumed per day.

3. Results

Once the two-month experiment had concluded, we proceeded to review the results. The aim of this study is to answer the question: does the presence of birds of prey in the treetops deter rodents from accessing the ground beneath the canopy to feed on acorns?

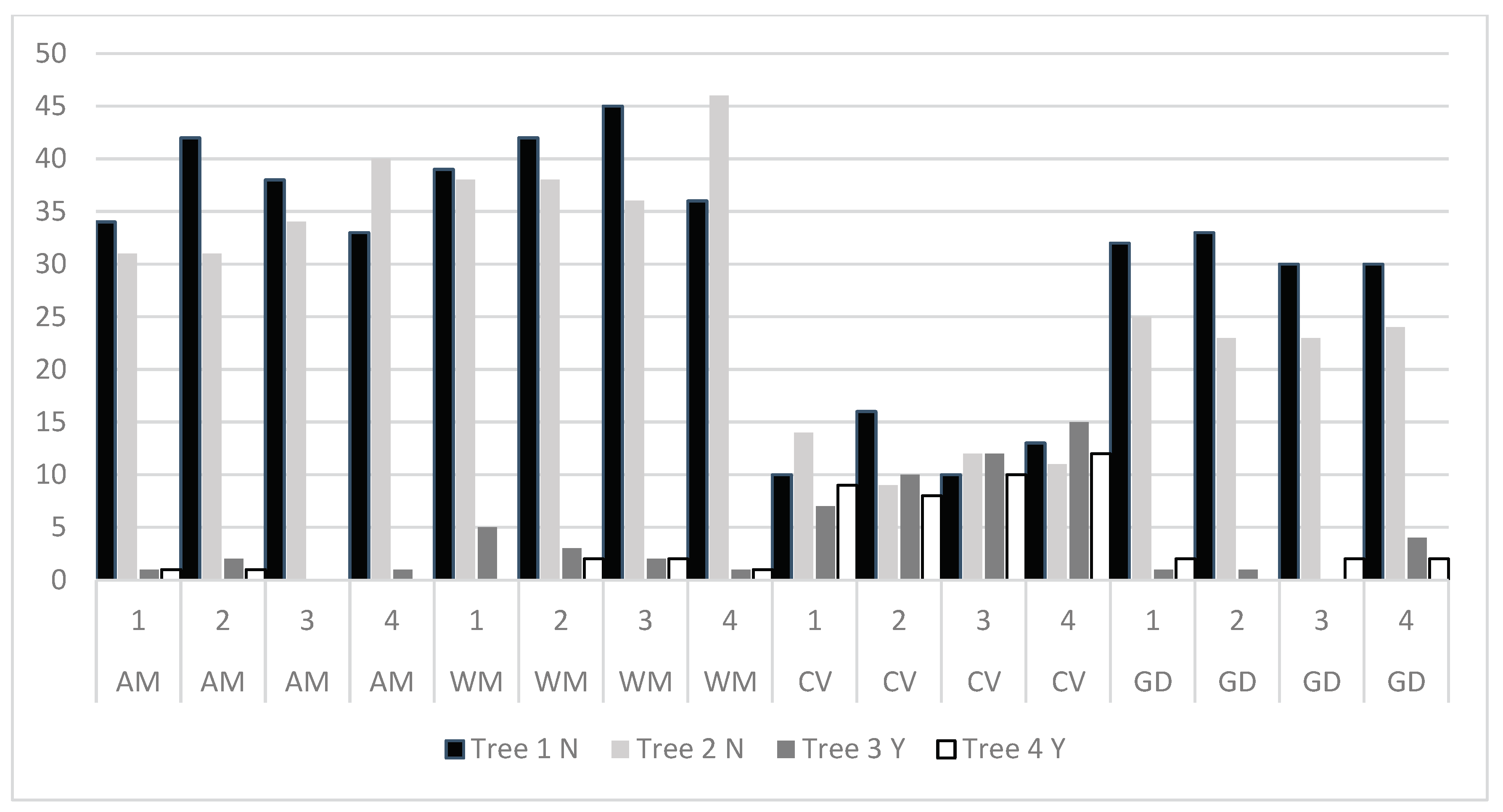

Table 1 shows the results of the influence of rodent species, tree type (with or without birds of prey), time elapsed, and individual rodents of each species on the number of acorns moved by rodents under the four trees per plot where acorns were available. The result is that there are significant differences between the number of acorns moved between the different types of trees in the plots and between rodent species

and over time, but there are no significant differences between individuals, indicating that the behaviour of the four specimens belonging to each species is homogeneous

, with no different preferences when consuming acorns from different points in the plot.

The significant differences over time indicate that there must be a period of adaptation to the new environment or that there is some learning period during the days of the experiment. It is likely that the presence of birds of prey triggers this learning.

The number of acorns moved or consumed by each individual of each rodent species under the four trees in each plot is shown in

Figure 4. Trees 1N and 2N have no birds of prey in their branches. Trees 3Y and 4Y have dummies imitating birds of prey in their branches near the ground. There are three species, Algerian mouse, Wood mouse and Garden dormouse which move many acorns from trees 1N and 2N, but they are not active under trees where birds of prey are present, trees 3Y and 4Y. Garden dormice move fewer acorns under treetops without birds of prey than Algerian mouse and Wood mouse.

Common vole is the species that moves the fewest acorns under all types of trees. However, this species shows no difference between consuming acorns under one type of tree or another. The presence of birds of prey does not seem to affect them; consuming acorns under trees where birds of prey are present does not cause them any stress.

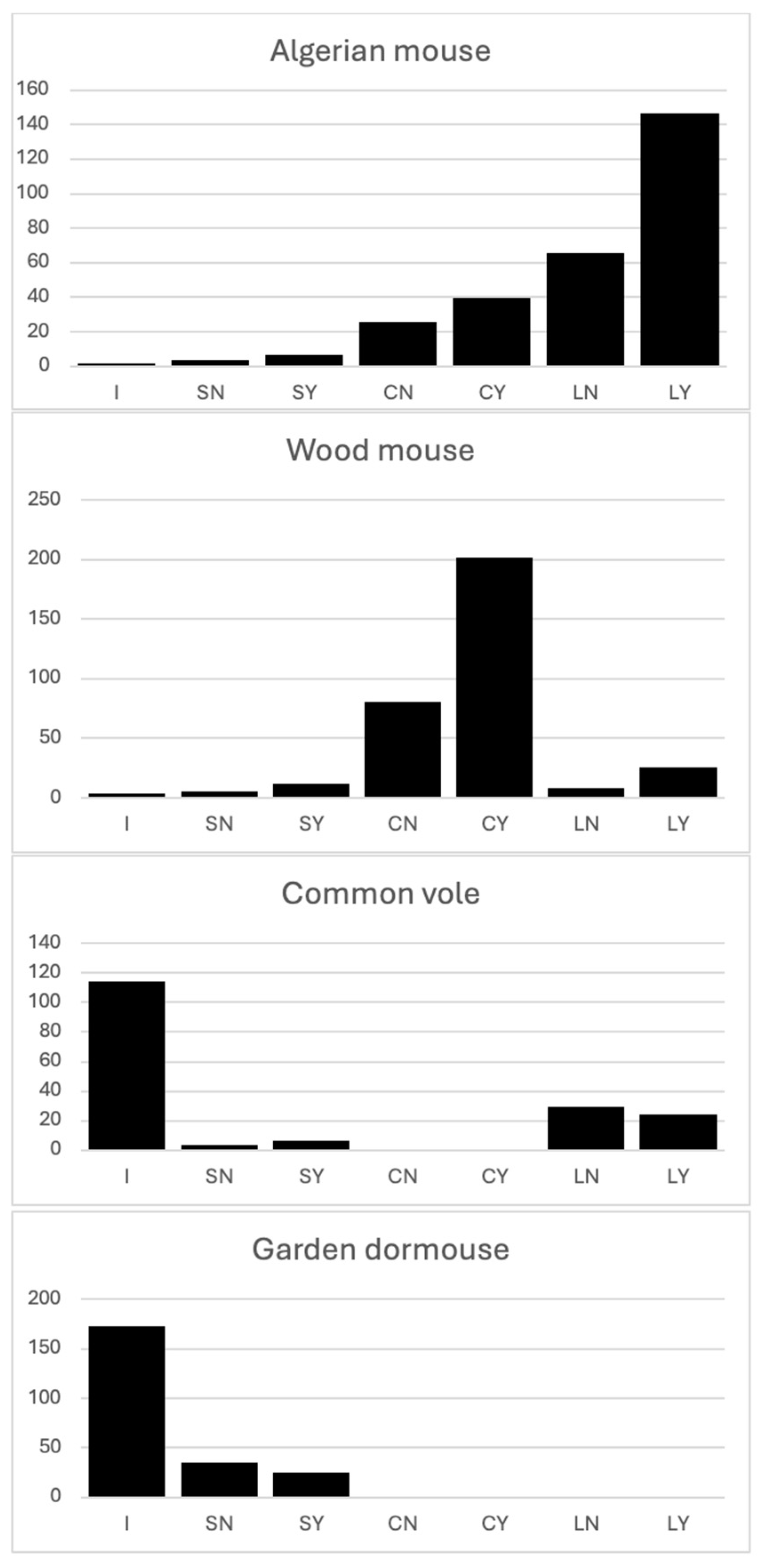

The locations where the four rodent species consume, deposit, or store acorns are shown in

Figure 5. The results show that Algerian mouse prefer to deposit their acorns in larders, the artificial containers that we bury to mimic their larders. Of these deposits, it prefers to use those that are under bushes, which provide aerial protection from branches. In situ consumption in this species is practically non-existent. Some acorns are stored in caches, but it also prefers those protected by branches. Wood mouse, on the other hand, prefer to store their acorns in caches and prefer to use those they build under bushes or scrub protected by branches. It does not consume acorns in situ and makes very little use of larders (artificial containers). Common vole and Garden dormouse consume most of their acorns in situ. Garden dormouse do not store acorns in caches and do not use containers that mimic larder, but common voles do use them.

We did not know how Garden dormouse’ behaved when processing acorns. We have found that it consumes the acorns whole but opens them at the basal end and eats them from this end to the apical end until they are empty, leaving the empty apical domes untouched (

Figure 2).

Figure 3 shows the number of acorns consumed entirely by each rodent species and the number of empty apical domes that each species leaves behind after consuming the acorns completely. Garden dormouse eat many acorns whole and leave many empty apical domes because they are the largest species and when they attack an acorn, they can consume it entirely because it fits in their stomach. The other three species cannot do this due to their body size. Algerian mouse and Wood mouse behave in the same way when they consume whole acorns, leaving the empty apical domes untouched after several attacks, but the number of acorns completely consumed by these two species is very low compared to those consumed by the Garden dormouse.

4. Discussion

In response to the question that led us to conduct this experiment, we can say that the interference of a third predatory species in the collaborative relationship between rodents and oak trees causes significant changes in the behaviour of the rodents, paralysing or reducing the participation of rodent species in the dissemination process [

43,

44,

45].

Two species of rodents, Algerian mouse and Wood mouse, which have been consuming acorns since the Holocene and Pleistocene epochs and which contribute to the dispersal of acorns, as we have seen in previous studies [

15,

17,

50], are not active under the canopy of trees where birds of prey are present, possibly because they perceive these creatures as dangerous [

43]. It is likely that due to previous negative experiences with birds of prey, they consider bird of prey effigies to be a threat and therefore do not risk entering an area devoid of camouflage and hiding places (we left the ground clear during the preparation of the experiment), even though there are significant accumulations of acorns, which are nutrients and resources, just a few centimetres away. The elimination of these access points to acorns deposited under the canopy due to the presence of birds of prey would paralyse or reduce the seed dispersal process carried out intensively by these two species of rodents [

43,

45,

54]. This would compromise the dispersal process of acorns sought by oak species, as one of the transport mechanisms they need would be paralysed or reduced [

13]. These two species of rodents had probably already had contact with nocturnal birds of prey in similar situations prior to the experiment, as they inhabit wooded areas. The proof that the presence of birds of prey paralyses their acorn scatter-hoard activity is that under trees without birds of prey, they are very active, moving large quantities of acorns.

Garden dormouse exhibits behaviour like the two previous species. Under the canopy of trees without birds of prey, they consume acorns, although the number of acorns moved from these locations without birds of prey is lower than that moved by the Algerian mouse and wood mouse. This may be because the garden dormouse has a much more varied diet than the other two species [

55]. Its diet includes insects and larvae found in the four plots. It is likely that if it obtains more nutrients from these types of food, it will not prey on acorns as intensely as the Algerian mouse and Wood mouse do. Garden dormice also cease their activity under tree canopies when birds of prey are present. This species also inhabits open areas and farmland where there is no pressure from birds of prey [

56]. However, they must have had previous negative experiences with these birds of prey because they perceive their presence as a risk.

Common vole does not modify its predatory behaviour towards acorns due to the presence of birds of prey. There are probably two reasons for this. Firstly, because it is not a species accustomed to consuming acorns. The number of acorns it preys on is the lowest of the four rodent species. This species usually consumes fresh green herbaceous plants [

46]. Here, it uses acorns because they are a very nutritious food source. The second reason why birds of prey do not change their behaviour is because this is not their usual habitat. It is found in open crop and grassland areas without tree cover [

46]. It is likely that your specimens have not had previous negative experiences with birds of prey attacking from tree branches, which do not exist in their habitat. For this reason, they do not perceive the dummies that imitate birds of prey as a threat and do not change their behaviour under some tree canopies and others.

The final destinations of the acorns confirm that Algerian mouse and Wood mouse actively participate in the process of acorn dispersal, as they transport acorns and bury them, each species in different storage sites according to their preferences [

43]. It is also clear that the Common vole and Garden dormouse do not participate in the acorn dispersal process. Both species consume acorns

in situ without moving them to protected locations. Furthermore, both species destroy the embryo, and are therefore acorn predators. Garden dormouse opens them at the basal end, like Algerian mouse and Wood mouse, but the Common vole does not. Although Garden dormouse opens them at the basal end, probably due to the presence of tannins in the apical shell dome, it consumes most of the acorns it attacks completely, including the embryo. The presence of these remains of the apical dome of the shell in acorns completely consumed by Garden dormouse, Algerian mouse and Wood mouse leads us to believe that the concentration of tannins around the embryo found by [

37] is actually concentrated in the shell surrounding the embryo, as this structure, the apical dome, is not attacked by any of the three species.

The behaviour of Garden dormouse about the fate of acorns disproves one of the hypotheses we had proposed in the second objective. The participation of rodent species in the process of acorn dispersal would begin with the transport of acorns from the places where they are deposited by barochory to underground stores. However, this transport must have been caused by some circumstance. Some authors suggest that it is the plant that causes this by synthesising acorns with barriers that make it difficult for rodents to access them [

34,

54]. The

in situ handling of acorns with these characteristics by rodents forces them to extend the handling time and exposure to their own predators (birds of prey, among others) [

43]. With this experiment, we also wanted to see whether the presence of birds of prey in the branches of trees encourages rodents to move the acorns to more protected places. In the case of the Algerian mouse and the Wood mouse, this is indeed the case. These two species store acorns in stores located under bushes or branches where they are protected from birds of prey. Even the few acorns that are left on the surface remain under bushes (

Figure 5). However, the behaviour of the Garden dormouse contradicts this hypothesis. It also sees birds of prey as a danger, as it reduces its activity under the canopy when birds of prey are present, but by consuming most of the acorns

in situ and not transporting them, it encourages us to dismiss the idea that the origin of acorn transport by rodents is due to fear of the existence of birds of prey in the treetops under which the acorns are collected, in order to take them to places that are more protected from these predatory birds. This different behaviour of the Garden dormouse may be due to the fact that it is a larger and more aggressive species than Algerian mouse and Wood mouse [

57,

58], but just as it identifies the birds of prey present in the treetops as a danger, it should consider, as the Algerian mouse and the wood mouse do, that birds of prey could also be present in the rest of the treetops. Garden dormouse does not exhibit this behaviour; under the canopy of trees without birds of prey, it perceives no danger and consumes acorns in situ without having to hide. However, it is striking that the few acorns it moves under the canopy with birds of prey, where it perceives the risk, are not consumed

in situ, but are moved and left on the ground surface. Algerian mouse and Wood mouse have been occupying this type of habitat longer than the Garden dormouse and use it more assiduously. This difference could explain the difference in behaviour. It is also possible that the fear of birds of prey that prevents Algerian mouse and Wood mouse from consuming acorns

in situ under any tree canopy and forces them to move the acorns to protected places is a behaviour genetically transmitted by their ancestors, but this will be the subject of future studies.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, Sergio Del Arco; Investigation, Sergio Del Arco; Resources, Sergio Del Arco; Software, Sergio Del Arco; Validation, Sergio Del Arco, Jose M Del Arco; Data curation, Jose M Del Arco; Formal analysis, Sergio Del Arco and Jose M Del Arco; Funding acquisition, Jose M Del Arco; Investigation, Sergio Del Arco and Jose M Del Arco; Methodology, Jose M Del Arco; Resources, Sergio Del Arco and Jose M Del Arco; Software, Sergio Del Arco and Jose M Del Arco; Supervision, Jose M Del Arco; Validation, Sergio Del Arco and Jose M Del Arco; Visualization, Jose M Del Arco; Writing – original draft, Jose M Del Arco; Writing – review & editing, Jose M Del Arco.