Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

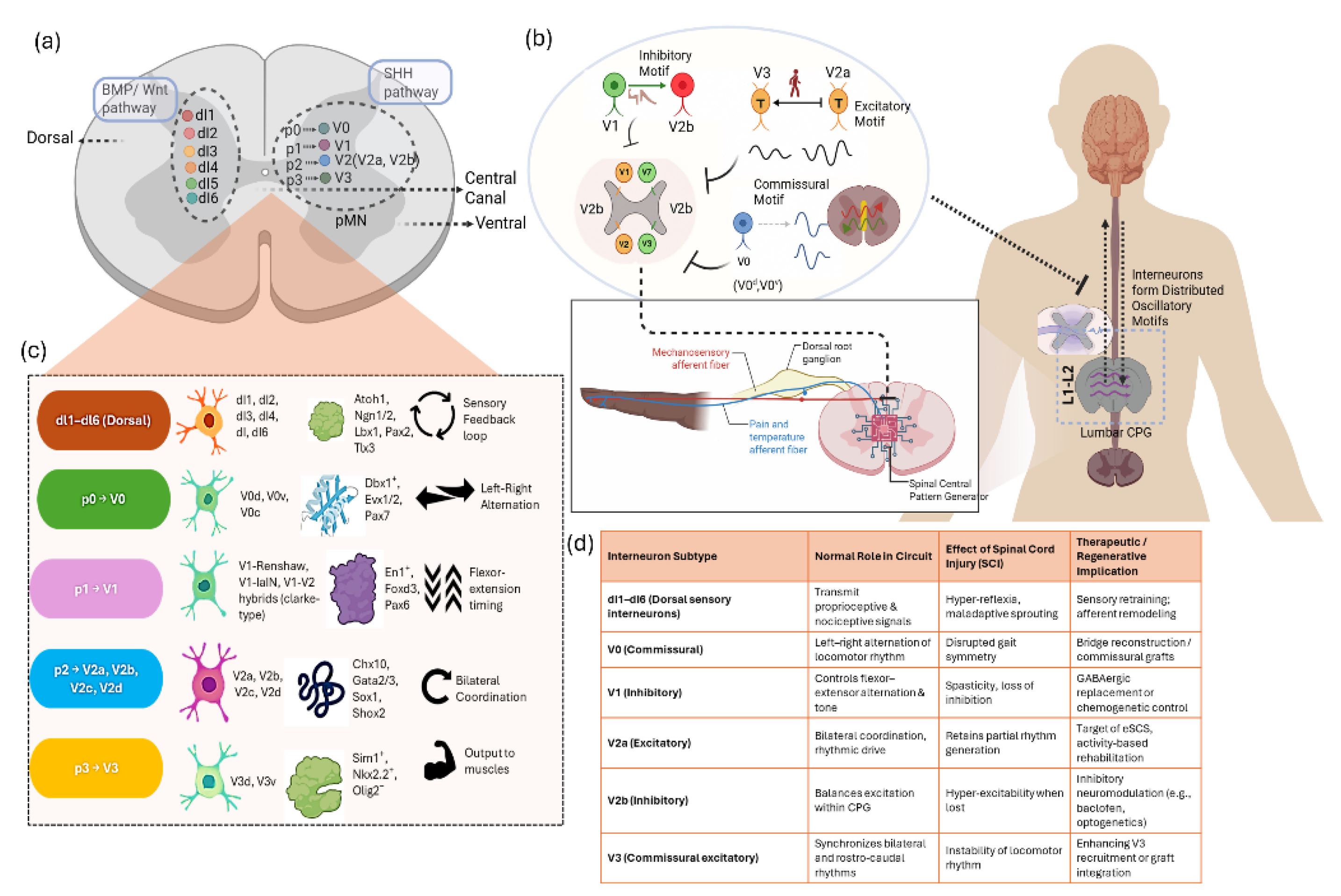

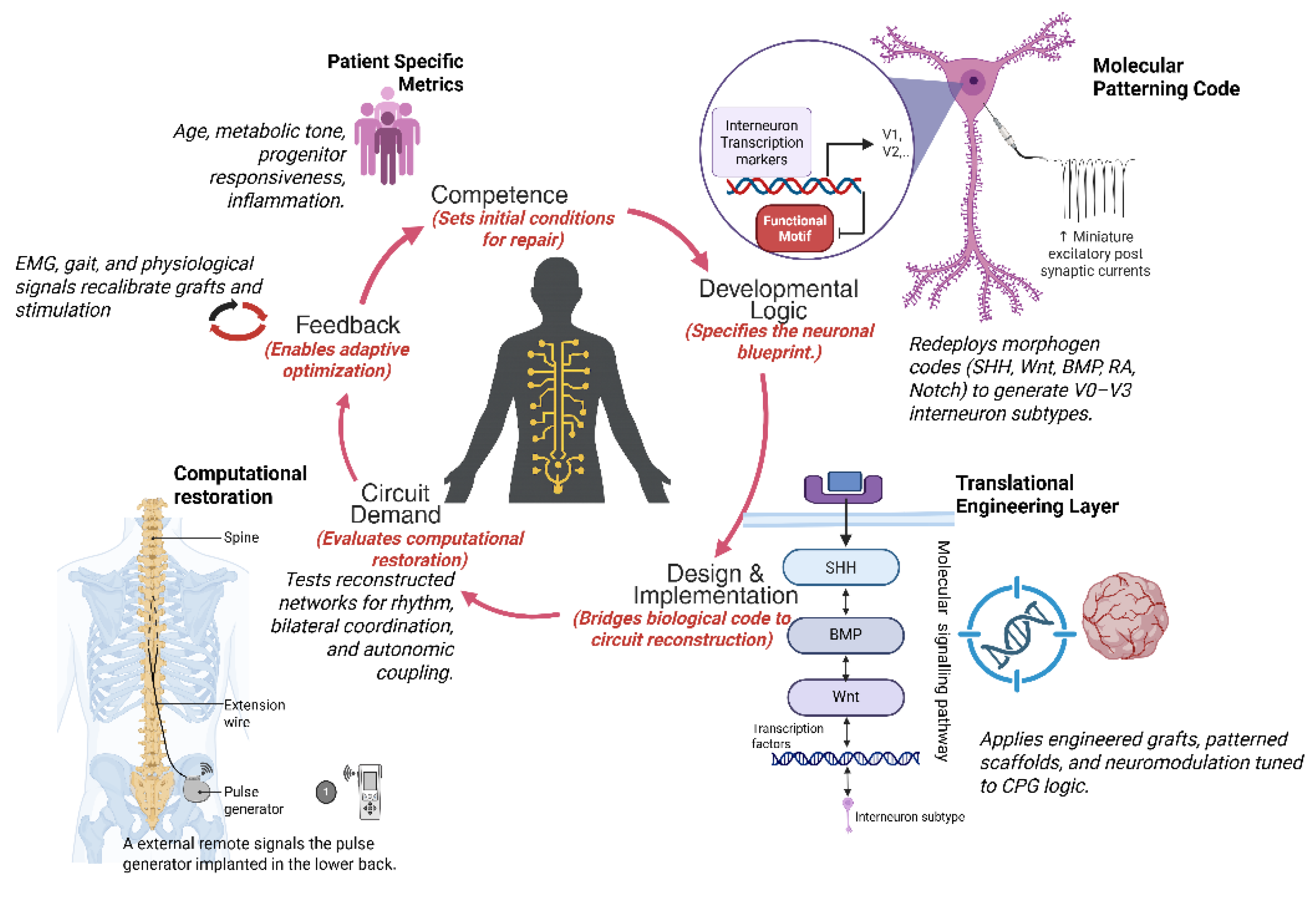

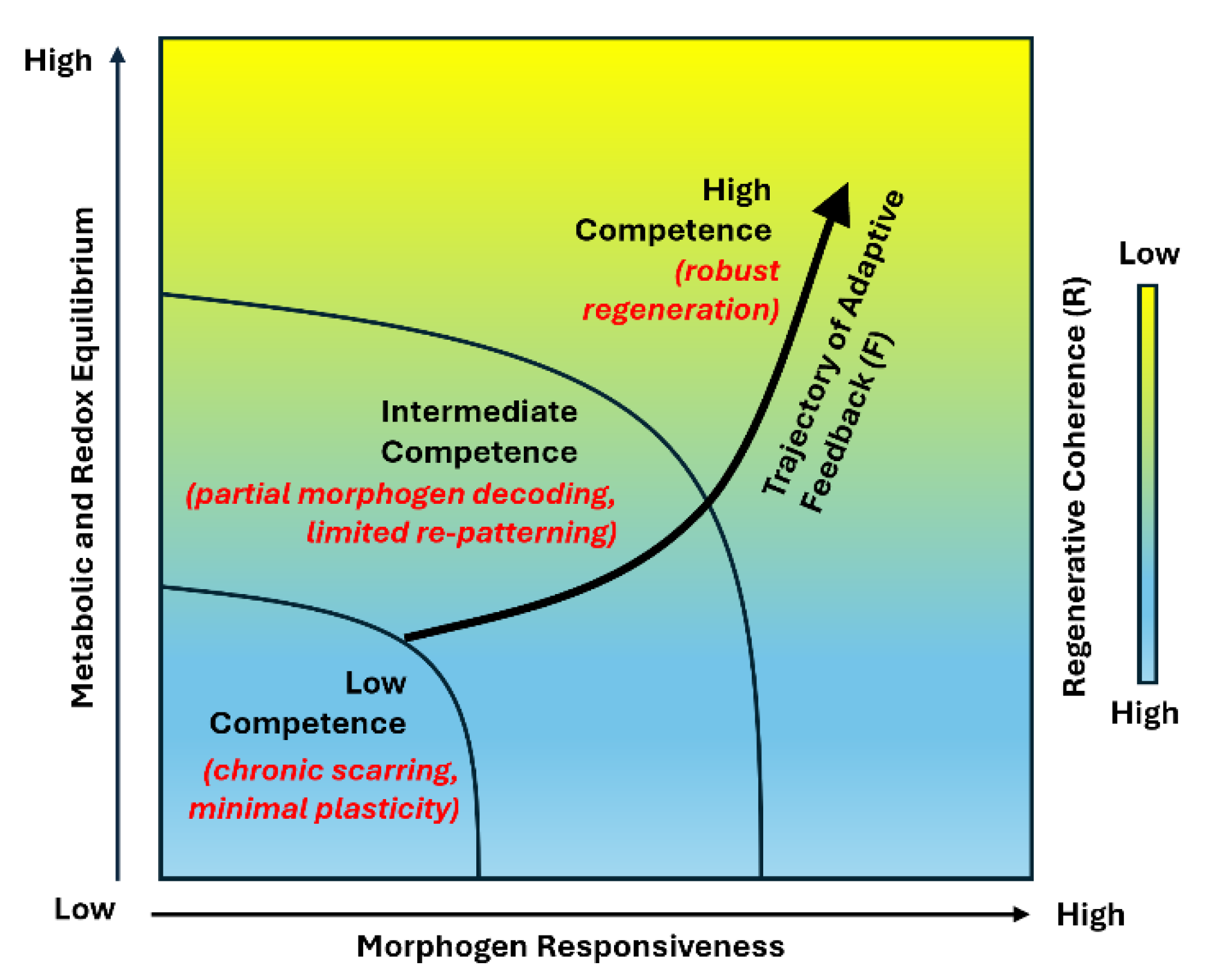

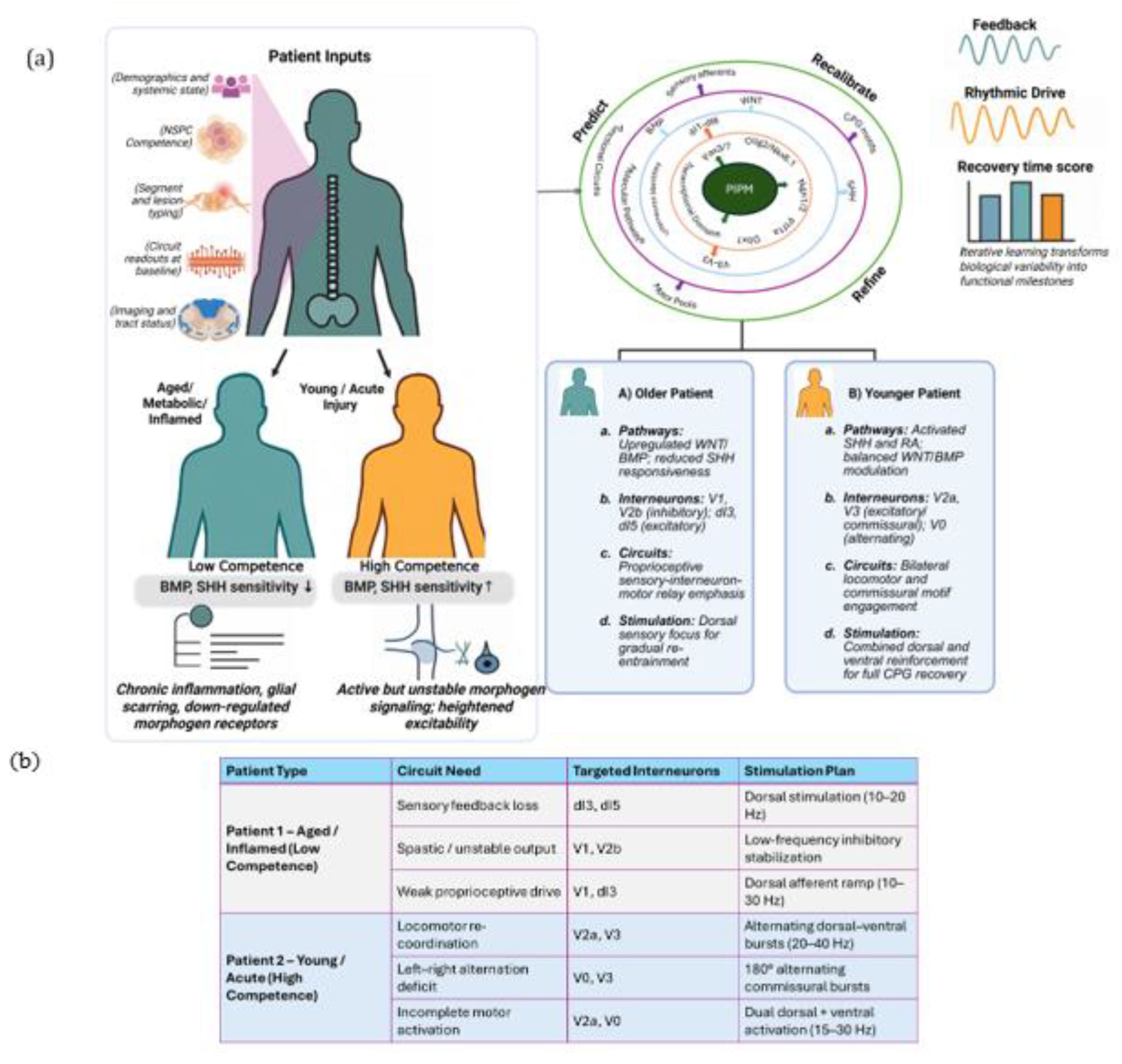

Spinal interneurons constitute the computational core of spinal circuitry, integrating excitatory and inhibitory inputs to generate the rhythmic patterns that drive locomotor, postural, and autonomic control. Their developmental logic, molecular diversity, and adaptive plasticity make them central determinants of functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Yet most regenerative strategies continue to emphasize cellular replacement rather than the restoration of the computational integrity of spinal networks. In this review, we reframe spinal repair as the reconstitution of circuit computation. We synthesize current insights into how embryonic patterning programs defined by SHH, Wnt, and BMP gradients, refined by Notch and retinoic acid signaling, and consolidated by axon guidance cues, establish interneuron diversity, connectivity, and network symmetry that together encode the logic of motor coordination. Spinal cord injury disrupts this developmental logic, fragmenting excitatory and inhibitory balance and desynchronizing rhythmic modules, while residual circuits retain latent capacity for resynchronization through plasticity and neuromodulation. Building upon this developmental and computational continuum, we propose the Patient Specific Interneuron Precision Model (PIPM), a closed loop framework that links patient specific biological states including progenitor competence, morphogen sensitivity, and metabolic tone to circuit level computation and recovery potential. By bridging molecular, physiological, and clinical insights, the PIPM establishes a systems logic that unifies biological competence with circuit recovery, positioning interneuron computation as the conceptual foundation for precision spinal cord regeneration.

Keywords:

1. Overview

2. Developmental & Circuit Logic

3. Injury-Induced Computation Loss

4. Patient-Specific Interneuron Precision Model (PIPM) Linking Molecular State to Circuit Recovery

5. Clinical Translation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Competing Interests

Acknowledgments

Ethics Statement

Informed Consent

References

- Sengupta, M. & Bagnall, M. W. Spinal Interneurons: Diversity and Connectivity in Motor Control. Annu Rev Neurosci 46, 79–99 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kiehn, O. Decoding the organization of spinal circuits that control locomotion. Nat Rev Neurosci 17, 224–238 (2016).

- Zholudeva, L. V. et al. Spinal Interneurons as Gatekeepers to Neuroplasticity after Injury or Disease. The Journal of Neuroscience 41, 845–854 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Gosgnach, S. Spinal inhibitory interneurons: regulators of coordination during locomotor activity. Front Neural Circuits 17, (2023).

- Grillner, S. & El Manira, A. Current Principles of Motor Control, with Special Reference to Vertebrate Locomotion. Physiol Rev 100, 271–320 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A. C. & Sweeney, L. B. Spinal cords: Symphonies of interneurons across species. Front Neural Circuits 17, 1146449 (2023).

- Ampatzis, K., Song, J., Ausborn, J. & El Manira, A. Separate Microcircuit Modules of Distinct V2a Interneurons and Motoneurons Control the Speed of Locomotion. Neuron 83, 934–943 (2014).

- Ziskind-Conhaim, L. & Hochman, S. Diversity of molecularly defined spinal interneurons engaged in mammalian locomotor pattern generation. J Neurophysiol 118, 2956–2974 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Talpalar, A. E. et al. Dual-mode operation of neuronal networks involved in left–right alternation. Nature 500, 85–88 (2013).

- Asboth, L. et al. Cortico–reticulo–spinal circuit reorganization enables functional recovery after severe spinal cord contusion. Nat Neurosci 21, 576–588 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Wagner, F. B. et al. Targeted neurotechnology restores walking in humans with spinal cord injury. Nature 563, 65–71 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Kvistad, C. E., Kråkenes, T., Gavasso, S. & Bø, L. Neural regeneration in the human central nervous system—from understanding the underlying mechanisms to developing treatments. Where do we stand today? Front Neurol 15, (2024).

- Fischer, G. et al. Advancements in neuroregenerative and neuroprotective therapies for traumatic spinal cord injury. Front Neurosci 18, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Lu, P. et al. Long-Distance Growth and Connectivity of Neural Stem Cells after Severe Spinal Cord Injury. Cell 150, 1264–1273 (2012).

- Ni, W. et al. Immunomodulatory and Anti-inflammatory effect of Neural Stem/Progenitor Cells in the Central Nervous System. Stem Cell Rev Rep 19, 866–885 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, W. et al. A Systematic Review of Cellular Transplantation Therapies for Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma 28, 1611–1682 (2011).

- YAMASHITA, T. & ABE, K. Recent Progress in Cell Reprogramming Technology for Cell Transplantation Therapy. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 56, 97–101 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Dulin, J. N. & Lu, P. Bridging the injured spinal cord with neural stem cells. Neural Regen Res 9, (2014). [CrossRef]

- Ottoboni, L., von Wunster, B. & Martino, G. Therapeutic Plasticity of Neural Stem Cells. Front Neurol 11, (2020).

- Yang, Y. et al. Epigenetic regulation and factors that influence the effect of iPSCs-derived neural stem/progenitor cells (NS/PCs) in the treatment of spinal cord injury. Clin Epigenetics 16, 30 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Elhabbari, K., Sireci, S., Rothermel, M. & Brunert, D. Olfactory deficits in aging and Alzheimer’s—spotlight on inhibitory interneurons. Front Neurosci 18, (2024).

- Szegedi, V. et al. Aging-associated weakening of the action potential in fast-spiking interneurons in the human neocortex. J Biotechnol 389, 1–12 (2024).

- Jagadeesan, S. K., Sandarage, R. V., Mathiyalagan, S. & Tsai, E. C. Personalized Stem Cell-Based Regeneration in Spinal Cord Injury Care. Int J Mol Sci 26, 3874 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. K., White, C. W. & Villeda, S. A. The systemic environment: at the interface of aging and adult neurogenesis. Cell Tissue Res 371, 105–113 (2018).

- Lecanu, L., Jay Waldron & Althea McCourty. Aging differentially affects male and female neural stem cell neurogenic properties. Stem Cells Cloning 119 (2010) doi:10.2147/SCCAA.S13035.

- Lengefeld, J. et al. Cell size is a determinant of stem cell potential during aging. Sci Adv 7, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Guo, H., Carey, M. & Huang, C. Transcriptional and epigenetic dysregulation impairs generation of proliferative neural stem and progenitor cells during brain aging. Nat Aging 4, 62–79 (2024).

- Lu, Q., Wang, X. & Tian, J. A new biological central pattern generator model and its relationship with the motor units. Cogn Neurodyn 16, 135–147 (2022).

- Rybak, I. A., Shevtsova, N. A., Lafreniere-Roula, M. & McCrea, D. A. Modelling spinal circuitry involved in locomotor pattern generation: insights from deletions during fictive locomotion. J Physiol 577, 617–639 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Rybak, I. A., Dougherty, K. J. & Shevtsova, N. A. Organization of the Mammalian Locomotor CPG: Review of Computational Model and Circuit Architectures Based on Genetically Identified Spinal Interneurons(1,2,3). eNeuro 2, (2015). [CrossRef]

- Vallstedt, A. & Kullander, K. Dorsally derived spinal interneurons in locomotor circuits. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1279, 32–42 (2013).

- Goyal, R., Spencer, K. A. & Borodinsky, L. N. From Neural Tube Formation Through the Differentiation of Spinal Cord Neurons: Ion Channels in Action During Neural Development. Front Mol Neurosci 13, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Francius, C. et al. Identification of Multiple Subsets of Ventral Interneurons and Differential Distribution along the Rostrocaudal Axis of the Developing Spinal Cord. PLoS One 8, e70325 (2013).

- Chapman, P. D. et al. A brain-wide map of descending inputs onto spinal V1 interneurons. Neuron 113, 524-538.e6 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Chopek, J. W., Nascimento, F., Beato, M., Brownstone, R. M. & Zhang, Y. Sub-populations of Spinal V3 Interneurons Form Focal Modules of Layered Pre-motor Microcircuits. Cell Rep 25, 146-156.e3 (2018).

- Lundfald, L. et al. Phenotype of V2-derived interneurons and their relationship to the axon guidance molecule EphA4 in the developing mouse spinal cord. Eur J Neurosci 26, 2989–3002 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Kumru, H., Vidal, J., Kofler, M., Portell, E. & Valls-Solé, J. Alterations in Excitatory and Inhibitory Brainstem Interneuronal Circuits after Severe Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurotrauma 27, 721–728 (2010).

- Hughes, D. I. & Todd, A. J. Central Nervous System Targets: Inhibitory Interneurons in the Spinal Cord. Neurotherapeutics 17, 874–885 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J. R., Graham, B. A., Galea, M. P. & Callister, R. J. The role of propriospinal interneurons in recovery from spinal cord injury. Neuropharmacology 60, 809–822 (2011).

- Courtine, G. et al. Transformation of nonfunctional spinal circuits into functional states after the loss of brain input. Nat Neurosci 12, 1333–1342 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Deska-Gauthier, D. & Zhang, Y. The functional diversity of spinal interneurons and locomotor control. Curr Opin Physiol 8, 99–108 (2019).

- Zavvarian, M.-M., Hong, J. & Fehlings, M. G. The Functional Role of Spinal Interneurons Following Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Front Cell Neurosci 14, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Harkema, S. et al. Effect of epidural stimulation of the lumbosacral spinal cord on voluntary movement, standing, and assisted stepping after motor complete paraplegia: a case study. Lancet 377, 1938–47 (2011).

- Park, J., Kim, Y. G., Kim, T. & Baek, M. Electrical Stimulation of the M1 Activates Somatostatin Interneurons in the S1: Potential Mechanisms Underlying Pain Suppression. eNeuro 12, ENEURO.0541-24.2025 (2025).

- Taccola, G. et al. Dynamic electrical stimulation enhances the recruitment of spinal interneurons by corticospinal input. Exp Neurol 371, 114589 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Balbinot, G. et al. Functional electrical stimulation therapy for upper extremity rehabilitation following spinal cord injury: a pilot study. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 9, 11 (2023).

- Singh, R. E. et al. Epidural stimulation restores muscle synergies by modulating neural drives in participants with sensorimotor complete spinal cord injuries. J Neuroeng Rehabil 20, 59 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Duysens, J. & Forner-Cordero, A. A controller perspective on biological gait control: Reflexes and central pattern generators. Annu Rev Control 48, 392–400 (2019).

- Golowasch, J. Neuromodulation of central pattern generators and its role in the functional recovery of central pattern generator activity. J Neurophysiol 122, 300–315 (2019).

- Fu, X. et al. Gq neuromodulation of BLA parvalbumin interneurons induces burst firing and mediates fear-associated network and behavioral state transition in mice. Nat Commun 13, 1290 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ljunggren, E. E., Haupt, S., Ausborn, J., Ampatzis, K. & El Manira, A. Optogenetic Activation of Excitatory Premotor Interneurons Is Sufficient to Generate Coordinated Locomotor Activity in Larval Zebrafish. The Journal of Neuroscience 34, 134–139 (2014).

- Falgairolle, M. & O’Donovan, M. J. Optogenetic Activation of V1 Interneurons Reveals the Multimodality of Spinal Locomotor Networks in the Neonatal Mouse. The Journal of Neuroscience 41, 8545–8561 (2021).

- Jessell, T. M. Neuronal specification in the spinal cord: inductive signals and transcriptional codes. Nat Rev Genet 1, 20–29 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, J. & Ericson, J. The specification of neuronal identity by graded sonic hedgehog signalling. Semin Cell Dev Biol 10, 353–362 (1999).

- Navarro Negredo, P., Yeo, R. W. & Brunet, A. Aging and Rejuvenation of Neural Stem Cells and Their Niches. Cell Stem Cell 27, 202–223 (2020).

- Ribes, V. & Briscoe, J. Establishing and Interpreting Graded Sonic Hedgehog Signaling during Vertebrate Neural Tube Patterning: The Role of Negative Feedback. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1, a002014–a002014 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, J. A. et al. Age-related gene expression changes in lumbar spinal cord: Implications for neuropathic pain. Mol Pain 16, 1744806920971914 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Vanacore, G., Christensen, J. B. & Bayin, N. S. Age-dependent regenerative mechanisms in the brain. Biochem Soc Trans 52, 2243–2252 (2024).

- Eavri, R. et al. Interneuron Simplification and Loss of Structural Plasticity As Markers of Aging-Related Functional Decline. The Journal of Neuroscience 38, 8421–8432 (2018).

- Kiehn, O. Development and functional organization of spinal locomotor circuits. Curr Opin Neurobiol 21, 100–109 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Wenger, N. et al. Spatiotemporal neuromodulation therapies engaging muscle synergies improve motor control after spinal cord injury. Nat Med 22, 138–145 (2016).

- Håkansson, S. et al. Data-driven prediction of spinal cord injury recovery: An exploration of current status and future perspectives. Exp Neurol 380, 114913 (2024).

- Guaraldi, P. et al. Effects of Spinal Cord Injury Site on Cardiac Autonomic Regulation: Insight from Analysis of Cardiovascular Beat by Beat Variability during Sleep and Orthostatic Challenge. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 7, 112 (2022).

- Kadoya, K. et al. Spinal cord reconstitution with homologous neural grafts enables robust corticospinal regeneration. Nat Med 22, 479–487 (2016).

- Xue, W. et al. Generation of dorsoventral human spinal cord organoids via functionalizing composite scaffold for drug testing. iScience 26, 105898 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lorach, H. et al. Walking naturally after spinal cord injury using a brain–spine interface. Nature 618, 126–133 (2023).

- Abbadie, C., Trafton, J., Liu, H., Mantyh, P. W. & Basbaum, A. I. Inflammation Increases the Distribution of Dorsal Horn Neurons That Internalize the Neurokinin-1 Receptor in Response to Noxious and Non-Noxious Stimulation. The Journal of Neuroscience 17, 8049–8060 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J. M. & Bradke, F. Therapeutic repair for spinal cord injury: combinatory approaches to address a multifaceted problem. EMBO Mol Med 12, (2020).

- Reali, C. & Russo, R. E. Neuronal intrinsic properties shape naturally evoked sensory inputs in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Front Cell Neurosci 7, (2013). [CrossRef]

- Jervis Rademeyer, H., Gauthier, C., Masani, K., Pakosh, M. & Musselman, K. E. The effects of epidural stimulation on individuals living with spinal cord injury or disease: a scoping review. Physical Therapy Reviews 26, 344–369 (2021).

- Ausborn, J., Shevtsova, N. A. & Danner, S. M. Computational Modeling of Spinal Locomotor Circuitry in the Age of Molecular Genetics. Int J Mol Sci 22, 6835 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Bareyre, F. M. et al. The injured spinal cord spontaneously forms a new intraspinal circuit in adult rats. Nat Neurosci 7, 269–277 (2004).

- Shevtsova, N. A. et al. Organization of left-right coordination of neuronal activity in the mammalian spinal cord: Insights from computational modelling. J Physiol 593, 2403–26 (2015).

- Buchner, F., Dokuzluoglu, Z., Grass, T. & Rodriguez-Muela, N. Spinal Cord Organoids to Study Motor Neuron Development and Disease. Life 13, 1254 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G., Pang, S., Li, Y. & Gao, J. Progress in the generation of spinal cord organoids over the past decade and future perspectives. Neural Regen Res 19, 1013–1019 (2024).

- Ajongbolo, A. O. & Langhans, S. A. Brain Organoids and Assembloids—From Disease Modeling to Drug Discovery. Cells 14, 842 (2025).

- Peng, R. et al. Spatial multi-omics analysis of the microenvironment in traumatic spinal cord injury: a narrative review. Front Immunol 15, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Rasoolinejad, M. et al. Machine learning predicts improvement of functional outcomes in spinal cord injury patients after inpatient rehabilitation. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences 6, (2025).

- Mariello, M. Reliability and stability of Bioelectronic Medicine: a critical and pedagogical perspective. Bioelectron Med 11, 16 (2025).

- Giagiozis, M. et al. Feasibility and Sensitivity of Wearable Sensors for Daily Activity Monitoring in Spinal Cord Injury Trials. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 39, 814–825 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Volpato, V. & Webber, C. Addressing variability in iPSC-derived models of human disease: guidelines to promote reproducibility. Dis Model Mech 13, (2020).

- Fan, X. et al. Strategies to overcome the limitations of current organoid technology - engineered organoids. J Tissue Eng 16, (2025). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).