1. Introduction

As a crucial component of clean and renewable energy, wind energy is playing an increasingly important role in the global energy transition. With the continuous development of wind power, wind farm layout optimization and operational efficiency improvement have become key research priorities. Among the various challenges involved, the wake effect between wind turbines stands out as a core factor affecting overall wind farm performance. The wake leads to reduced incoming wind speed and increased turbulence intensity for downstream turbines, consequently causing power losses and structural fatigue damage. Therefore, accurate prediction of wind turbine wake characteristics is of significant scientific and engineering importance for the micro-siting, power prediction, and lifetime assessment of wind farms [

1].

From the perspective of atmospheric structure, as noted by Cermak and Cochran [

2], the atmosphere within approximately 1000 meters above the ground surface typically constitutes the atmospheric boundary layer. The lowest 100 meters of boundary layer is defined as the atmospheric surface layer. Recently, to enhance wind energy capture efficiency and conserve land or sea resources, the wind power industry has been actively advancing the design and development of large-scale wind turbines [

3]. Since 2019, when the hub height of offshore wind turbines surpassed 103m and the rotor diameter reached 150m [

4], the industry has entered a phase of accelerated advancement. By the end of 2025, the world’s first 26 MW offshore wind turbine with hub height of 185 meters and rotor diameter of 310 meters has been successfully connected to the grid in Shandong Province, China. This trend indicates that modern wind turbines now operate beyond the atmospheric surface layer, and their aerodynamic performance is increasingly dependent on physical processes throughout the entire atmospheric boundary layer. Therefore, as a key factor governing wind shear, turbulent mixing, and energy transfer within the boundary layer, atmospheric stability is of growing importance in wind turbine wake assessment.

Atmospheric stability is generally categorized into stable, neutral, and unstable conditions. Under unstable atmospheric conditions, the air warmer than the surrounding environment expands and rises, promoting vertical development of turbulence to considerable heights. Under neutral atmospheric conditions, the air at the same temperature as its environment remains at its original height, resulting in only weak mixing [

5]. Under stable atmospheric conditions, the cooler air compresses and sinks, suppressing vertical motion and weakening vertical mixing [

6]. By directly influencing the wind speed profile and turbulence structure, atmospheric stability governs the recovery rate and spatial diffusion of wind turbine wakes ([

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]). Both field measurements and high-fidelity numerical simulations illustrate that the spatial distributions of wake velocity deficit and added turbulence intensity under different atmospheric stability conditions show significant differences. As demonstrated by Pérez et al. [

15], the annual energy production (AEP) vary by more than 16% under different stability conditions. Specifically, under stable conditions, the wind turbine wake recovers slowly , resulting in a persistent velocity deficit over a long downstream distance which leads to a lower AEP. In contrast, under unstable conditions, intense turbulent mixing facilitates faster wake recovery, yielding a higher AEP. Therefore, incorporating atmospheric stability into wake models is essential for improving wake prediction accuracy, enabling refined assessment of wind resources, and ensuring structural safety of turbines.

Traditional wake models, such as the classic Jensen (PARK) model and its derivatives, rely mostly on the assumption of neutral atmospheric conditions and depend heavily on empirical parameters. This limitation is typically exemplified by the variability of the wake decay coefficient in the Jensen model across different wind farms. Peña et al. [

16] found that in Sexbierum case, the wake decay coefficient of the Jensen model should be adjust from the typical onshore value of 0.075 to a site-specific value of 0.038. In response, some researchers have focused on quantifying the wake decay coefficient. Cheng and Porté-Agel [

17] proposed a physics-based wake model, drawing on scalar dispersion in turbulence. This model, accounts for the influence of ambient turbulence intensity based on Taylor’s diffusion theory. Vahidi and Porté-Agel [

18] developed a physics-based model by introducing a filtered turbulence scale to account for the combined effects of ambient and turbine-induced turbulence. Bastankhah and Porté-Agel [

19] proposed a concise analytical wake model based on the conservation of mass and momentum and a Gaussian-shaped velocity deficit, which requires a wake growth rate parameter to determine the wake velocity. Building upon this, Niayifar and Porté-Agel [

20] further enhanced the model by determining the wake growth rate from the local streamwise turbulence intensity. It should be noted that the key empirical constant was derived via linear regression of Large Eddy Simulation (LES) data, and its agreement with field measurements requires further validation. Ishihara and Qian [

21] estiblished a relationship linking the standard deviation of the Gaussian distribution to the turbine thrust coefficient and the incoming turbulence intensity, thereby overcoming the reliance on empirical parameters in wake models. Nevertheless, such modified models are proposed under neutral atmospheric conditions and their applicability should be further verified.

Recently, some researchers have focused on incorporating atmospheric stability into wake models for a more comprehensive assessment of wind turbine wakes, with the main methodologies falling into two categories: methods based on numerical simulations and methods involving the modification of previous analytical wake models. In the realm of numerical simulations, Kale et al. [

22,

23] employed LES within the Weather Research and Forecasting Model (WRF) framework with Monin-Obukhov similarity theory to generate stable and unstable atmospheric boundary layers, using an actuator disk model for turbine simulation. They investigated the aerodynamic characteristics of full-scale wind turbines under different atmospheric conditions using a generalized actuator disk model. However, this approach is computationally expensive. Furthermore, under stable stratification, it exhibits significant deviations in wake velocity deficit and delayed wake recovery due to low turbulence intensity, high wind shear, and wind veer. Nygaard et al. [

24] developed a simplified two-dimensional Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) model based on the Boussinesq buoyancy approximation, which incorporates vertical energy transfer under different stability conditions by simplifying the governing equations into a parabolic form. This method qualitatively reproduces the influence of updrafts and downdrafts on the wake, but prioritizes mechanistic insight over quantitative accuracy.

Compared to methods based on numerical simulations, some researchers have devoted efforts to a more concise and practical methodology: directly incorporating atmospheric stability parameters into analytical wake models. Emeis [

25] developed a top-down wind park model that integrates atmospheric stability effects on both momentum flux and momentum loss. Although it quantifies the macroscopic impact of atmospheric stability on the velocity deficit at hub height, it fails to capture the dynamics of individual turbine wakes and wind direction shifts. Abkar and Porté-Agel [

26] characterizes the differential growth of the wake in the lateral and vertical directions under different atmospheric conditions using a two-dimensional elliptical Gaussian distribution, in which wake growth rates were obtained by fitting LES results. Han et al. [

27] established a simple logarithmic model linking wake expansion to turbulence, thereby indirectly incorporating atmospheric stability. While efficiently captures key wake features, this model lacks an explicit stability parameter and performs poorly in the near-wake region under very low turbulence intensity. Cheng et al. [

28] linked atmospheric stability to the lateral turbulence intensity and proposed a linear relationship between the lateral turbulence intensity and the wake expansion rate. However, as the authors noted, the model possesses inherent limitations in the near-wake region and under low incoming turbulence intensity. Xiao et al. [

29] proposed the 3D-Stability-COUTI model, which incorporates the Obukhov length to predict wakes under different atmospheric stability conditions without empirical tuning. While accurate in general, its summation of two cosine functions results in an overemphasis of the bimodal velocity structure in the near-wake region under stable atmospheric conditions with low turbulence intensity and high wind shear.

Overall, the two aforementioned methodologies for incorporating atmospheric stability into wake models present distinct advantages and limitations. High-fidelity numerical methods like LES can directly resolve turbulent structures and wake expansion under different atmospheric stability conditions, offering clear physical mechanisms and broad applicability. However, their high computational cost limits their practicality for routine engineering applications. In contrast, modified analytical wake models include atmospheric stability parameters like the Monin-Obukhov length to approximate atmospheric stability effects to maintain computational efficiency. Nevertheless, their capacity to describe nonlinear responses under stable atmospheric stability conditions remains limited.

In summary, while progress has been made in establishing wake models considering atmospheric stability, several limitations are still exist: (i) Traditional models exhibit significant deviations in predicting wake velocity deficit and wake recovery process under stable atmospheric conditions; (ii) Most wake models lack a unified framework that is both adaptable to different atmospheric stability conditions and capable of sustaining high prediction accuracy throughout both the near-wake and far-wake regions; (iii) Key parameters in analytical wake models considering atmospheric stability often require case-specific calibration. These limitations urgently call for the development of a new generation of wake prediction methodologies: First, a atmospheric stability parameterization scheme should be established based on atmospheric boundary layer theory to accurately describe velocity profiles and the wake recovery process. Second, it is necessary to construct a unified wake prediction framework covering the entire wake region. Ultimately, by establishing functional relationships between key wake model parameters and atmospheric stability, a analytical wake model balancing physical fidelity with engineering applicability can be proposed.

Therefore, the structure of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 proposes a new wake model considering atmospheric stability, including fundamentals of atmospheric stability, previous wake models with atmospheric stability, proposal of new wake model with atmospheric stability and methodology for prediction accuracy assessment.

Section 3 provides performance assessment of the present wake model. In this section, field measurements from two cases-Vestas V27 wind turbine and Danwin 180kW wind turbine are adopted to assess wake model prediction performance. Finally, a summery and conclusions are presented in

Section 4.

2. Propose of a New Wake Model Considering Atmospheric Stability

2.1. Fundamentals of Atmospheric Stability

The Monin-Obukhov Similarity Theory (MOST) [

30], built upon the characteristic length scale proposed by Obukhov [

31], provides a universal framework for describing the turbulent structures within the atmospheric surface layer. This length scale is defined by the relative importance of buoyant production to mechanical shear production of turbulence kinetic energy. The core of the theory lies in applying dimensional analysis to simplify the complex turbulent transfer processes into functions of a single dimensionless parameter, ζ [

32]. The governing equations are given as follows [

33]:

In Equation (1), is stability parameter in which is the height above the ground surface and is the Obukhov length scale. is the Karman constant. is gravitational acceleration. is a temperature scale and is mean potential temperature. is the friction velocity.

Based on the definition of stability parameter, the logarithmic wind speed can be derived as[

30],

where

is the non-dimentional wind shear and

is the mean wind speed. To directly incorporate the Obukhov length L as a key stability parameter into the logarithmic wind speed profile, a piecewise function formulation was developed based on a series of field observations from the 1980s through dimensional analysis and empirical fitting ([

34,

35,

36]). The following form has since become the widely adopted standard model,

where

. As illustrated by Monin and Obukhov [

30], with stable stratification, the turbulent heat flux is directed downward,

; while unstable stratification on the other hand,

; with neutral stratification,

. According to surface layer theory [

37], the following relationship can be derived for the surface layer over flat and homogeneous terrain,

where

is the wind speed at height

. Dividing

by the wind speed at the hub height,

, eliminates

and yields the following equation for the incoming flow wind speed profile that accounts for atmospheric stability,

where

. Similarly, the incoming flow turbulence intensity profile that accounts for atmospheric stability,

where

is the turbulence intensity at the hub height. Therefore, this derivation enables the calculation of the incoming flow wind speed and turbulence intensity profiles via Equations (5) and (6), using the hub-height wind speed and turbulence intensity obtained from nacelle-based sensors such as LiDAR or 3D scanning LiDAR.

2.2. Previous Wake Models with Atmospheric Stability

In this study, two previous wake models considering atmospheric stability, 3D-Stability-COUTI [

29] and Cheng2019 [

28], are adopted for comparison with the present wake model. A brief review of the two wake models is provided below to establish a foundation for the subsequent comparative analysis.

Xiao et al. [

29] proposed an integrative three-dimensional cosine-shaped analytical model, named 3D-Stability-COUTI, for characterizing wake velocity and turbulence intensity under varying atmospheric stability conditions. Firstly, the essential input parameters for calculating the velocity deficit encompass the wind turbine specifications, atmospheric inflow conditions and terrain characteristics, as shown in

Table 1.

Then, according to

Table 1, the wind speed,

, and turbulence intensity,

, at hub height are essential input parameters for deriving the incoming wind velocity and turbulent intensity profiles via Equations (5) and (6) considering atmospheric stability.

After that, the wake radius

at any downstream position is determined using a stability-corrected wake width model that incorporates the Obukhov length, it is defined as follows,

where

is the rotor diameter.

is the Karman constant.

is the thrust coefficient.

is streamwise, spanwise and vertical coordinates, respectively.

The third step focuses on predicting the wake velocity at any downstream position through a two-stage process: a prediction step that calculates the 1D average wake velocity deficit

, shown in Equation (9) and a correction step that redistributes

in 3D space using a dual-cosine shape function, shwon in Equation (10) to obtain the detailed velocity deficit distribution

, shown in Equation (11). Finally, the wake velocity at any position in the wake field

is provided by combining the incoming wind velocity with the calculated velocity deficit distribution, shown in Equation (12).

where

.

is the half width of the single-peak deficit profile, calculated by

.

represents the radial distance from the wake centerline to the location of the maximum single-peak deficit, which is determined empirically as

.

is functionally dependent on

and is computed as

.

is the radial distance from the wake center position

.

Cheng et al. [

28] incorporated the Obukhov length into the parameterization of the lateral turbulence intensity to account for the effects of atmospheric stability. This wake model, referred to herein as Cheng2019 model, requires the input parameters listed in

Table 1. The incoming velocity and turbulence intensity profiles are calculated using Equations (5) and (6). Then, the lateral turbulence intensity , a parameter critical to wake expansion, is determined using the recommendation of ESDU (Equation (13)), which incorporations Coriolis effects via boundary layer height estimation. Based on this, the wake expansion rate is uniquely related to through a linear empirical formula given in Equation (15). Consequently, the intercept in the wake width growth function is derived as a function of , as presented in Equation (16). The standard deviation of the Gaussian wake profile is then obtained from and using Equation (17). The velocity deficit across the wake is subsequently computed with the Gaussian-shaped distribution, formulated in Equation (18). Finally, the wake velocity at any position in the wake field is calculated by combining the above results via Equation (12).

where

is the incoming turbulence intensity.

is the boundary layer height, which is estimated by,

where

is the Coriolis parameter, in which

is the angle of latitude and

rad/s is a constant presenting the angular rotation of the Earth.

2.3. Proposal of New Wake Model with Atmospheric stability

To enhance the applicability of wake model under different atmospheric stability conditions, an improved analytical wake model is proposed in this study, termed the Present model. The Present model employs Monin-Obukhov similarity theory (Equations (5) and (6)) to determine the incoming wind speed profile and turbulence intensity profile . Furthermore, a key improvement in the Present model is the refined parameterization of wake width and velocity deficit. By introducing a sign control parameter, , directly linked to atmospheric stability conditions, the model effectively characterizes the distinct physical mechanisms of wake expansion and recovery under stable and unstable conditions.

Specifically, the equations for calculating wake width in the Present model remains consistent with that in 3D-Stability-COUTI (Equations (7) and (8)). However, the range of values for the velocity deficit has been modified from

and

in 3D-Stability-COUTI to

. Concurrently, the velocity deficit formula has been revised from the sum of two cosine functions in 3D-Stability-COUTI to the square of a cosine function, as shown in the following equation,

where

.

is far-field decay function and

is the stability sign paramter, defined as follows,

The selection of as the demarcation between the near and far-wake regions is physically justified by the evolution of tip vortex dynamics and its impact on the wake structure.

During operation process of wind turbine, under the influence of turbulent fluctuations, tip vortices undergo random displacements that amplify with downstream distance (Yen et al. [

38]). The wake region is commonly divided into the near-wake, the intermediate wake, and far-wake regions: in the near-wake region (<2D), large-scale vortices within the shear layer lead to a bimodal distribution of turbulence intensity. As the wake develops further into the intermediate wake (3D to 5D), the shear layer continues to expand toward the wake centerline until the far-wake regions ([

39,

40,

41]). To accurately capture this transition in the velocity deficit decay, the far-field decay function is designed to remain unity (i.e., inactive) in the near-wake region (

), thereby preserving the near-wake structure, and initiates an exponential decay beyond

. This formulation effectively represents the enhanced mixing with the free-stream flow in the fully developed far-wake region, where the wake recovery is dominated by turbulent diffusion rather than organized vortex structures.

Regarding the stability sign parameter, a value of 1 is assigned under stable atmospheric conditions to represent the suppression of vertical mixing and lateral wake expansion. This is achieved by modulating the exponential term in the wake expansion model, effectively capturing the physics of turbulent diffusion. Conversely, under unstable and neutral atmospheric conditions, the stability sign parameter is set to -1 to enhance the wake expansion term. This models the accelerated wake recovery from intensified turbulent mixing, allowing wake width to dynamically respond to atmospheric stability, rather than relying solely on the empirical linear growth assumed under neutral conditions.

Furthermore, unlike the 3D-Stability-COUTI model, which constructs a bimodal velocity deficit profile through the superposition of two cosine functions, the Present model simplifies the lateral distribution of the velocity deficit by adopting a modified cosine-squared function. This modification shifts the model’s focus from characterizing the bimodal structure to a streamlined, universal description. While retaining the critical flow characteristics in the near-wake region, this approach significantly reduces mathematical complexity. By integrating this simplified velocity deficit distribution with the accurate incoming profiles and the wake width model with stability sign parameter, the Present model achieves effective wake predictions across the entire wake regions under different atmospheric stability conditions, without introducing additional empirical parameters. Consequently, it demonstrates a marked improvement in overall prediction accuracy.

To quantitatively compare the core formulations of the Present model against the 3D-Stability-COUTI and Cheng2019 models,

Table 2 summarizes the key mathematical representations governing the velocity deficit, wake width, and their stability-dependent modifications for each model.

2.4. Methodology for Prediction Accuracy Assessment

To quantitatively assess the prediction accuracy of the wake models under various atmospheric stability conditions, the hit rate metric, denoted as , is adopted in this study. This metric, employed by Chen and Ishihara ([

39,

40]), provides a normalized measure of the agreement between model predictions and experimental observations. The hit rate is defined as follows,

where

represents the

th observed value from field measurements, and

denotes the corresponding

th predicted value obtained from the wake models. The variable

indicates the total number of data points included in the comparison.

The hit rate ranges from 0 to 1, where indicates perfect agreement between predictions and measurements, and values approaching 0 signify increasing deviation. This metric is particularly suitable for evaluating wake model performance because it incorporates relative error in a normalized form, giving equal importance to errors across different velocity regimes-unlike absolute error measures, which can be dominated by high-speed data points. The application of this metric allows for a consistent and interpretable comparison of model performance across the different atmospheric stability regimes investigated in this work.

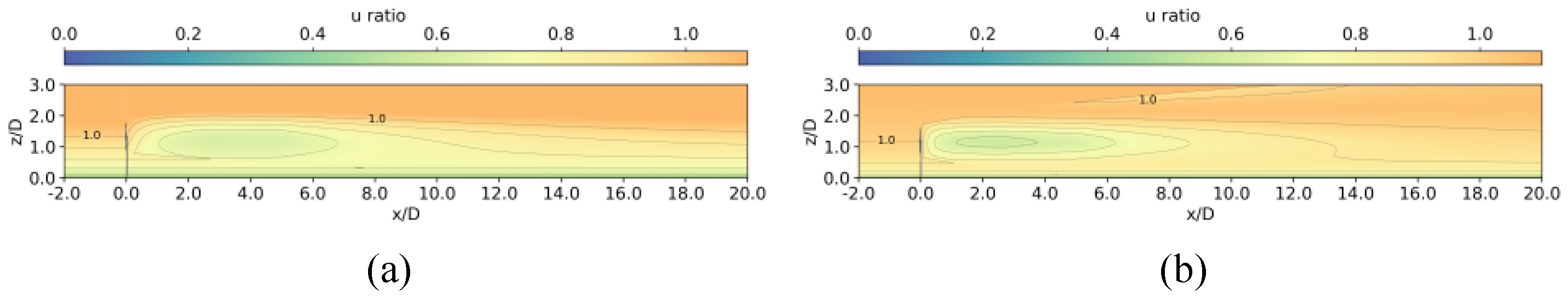

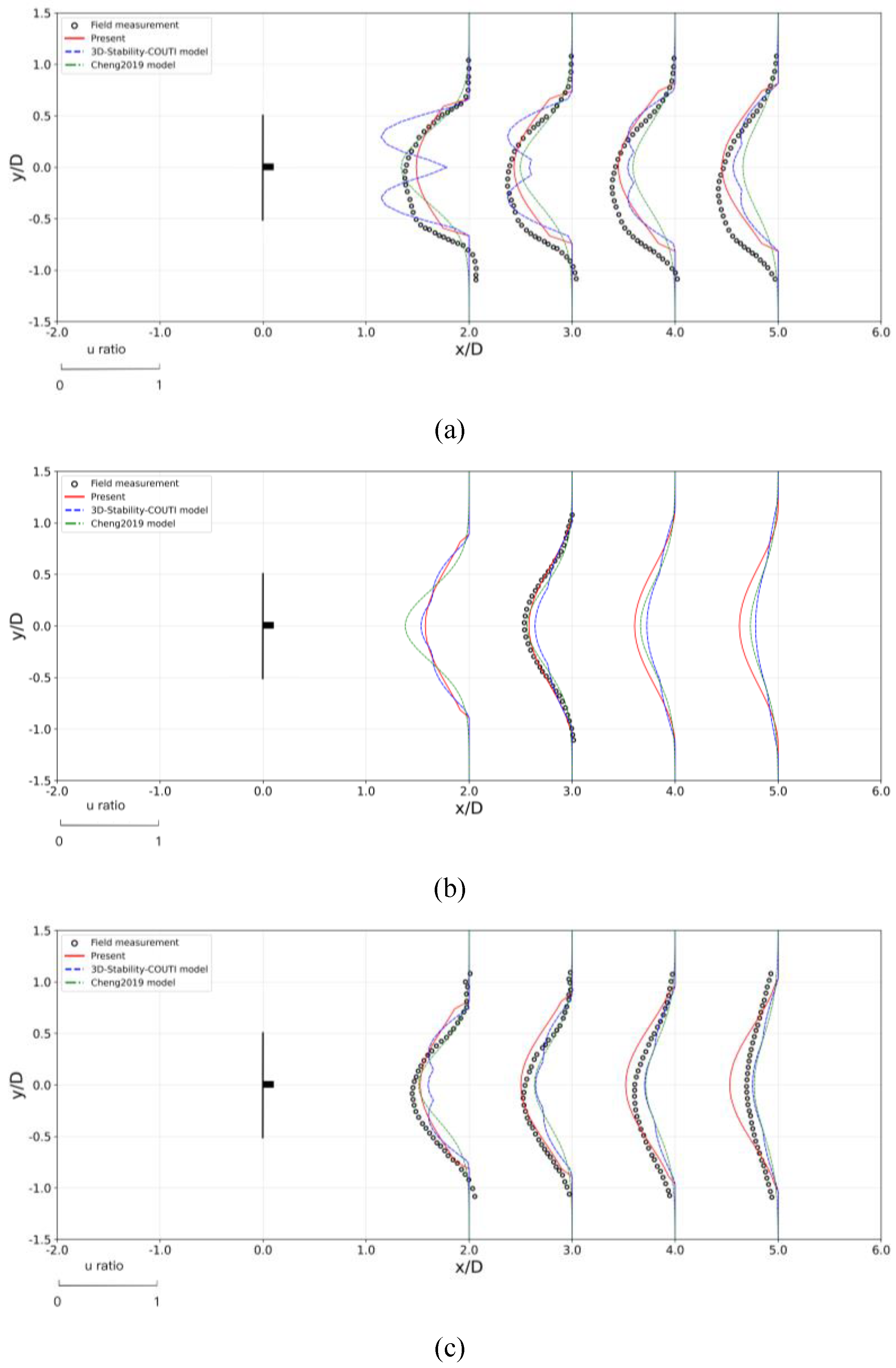

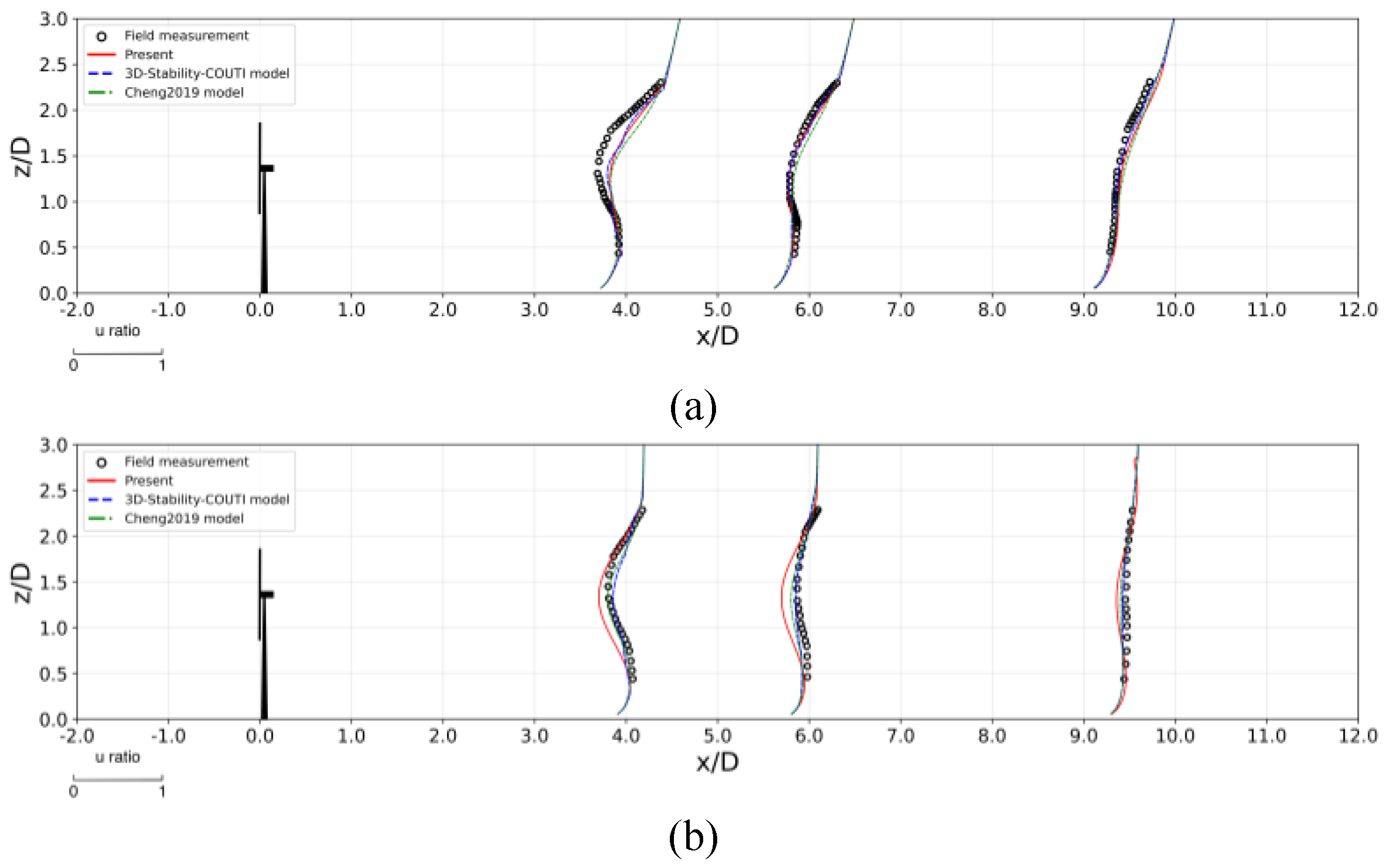

Figure 1.

Comparison of normalized wind speed profiles along the vertical centerline () for Case 1 under (a) stable, (b) unstable and (c) neutral atmospheric conditions.

Figure 1.

Comparison of normalized wind speed profiles along the vertical centerline () for Case 1 under (a) stable, (b) unstable and (c) neutral atmospheric conditions.

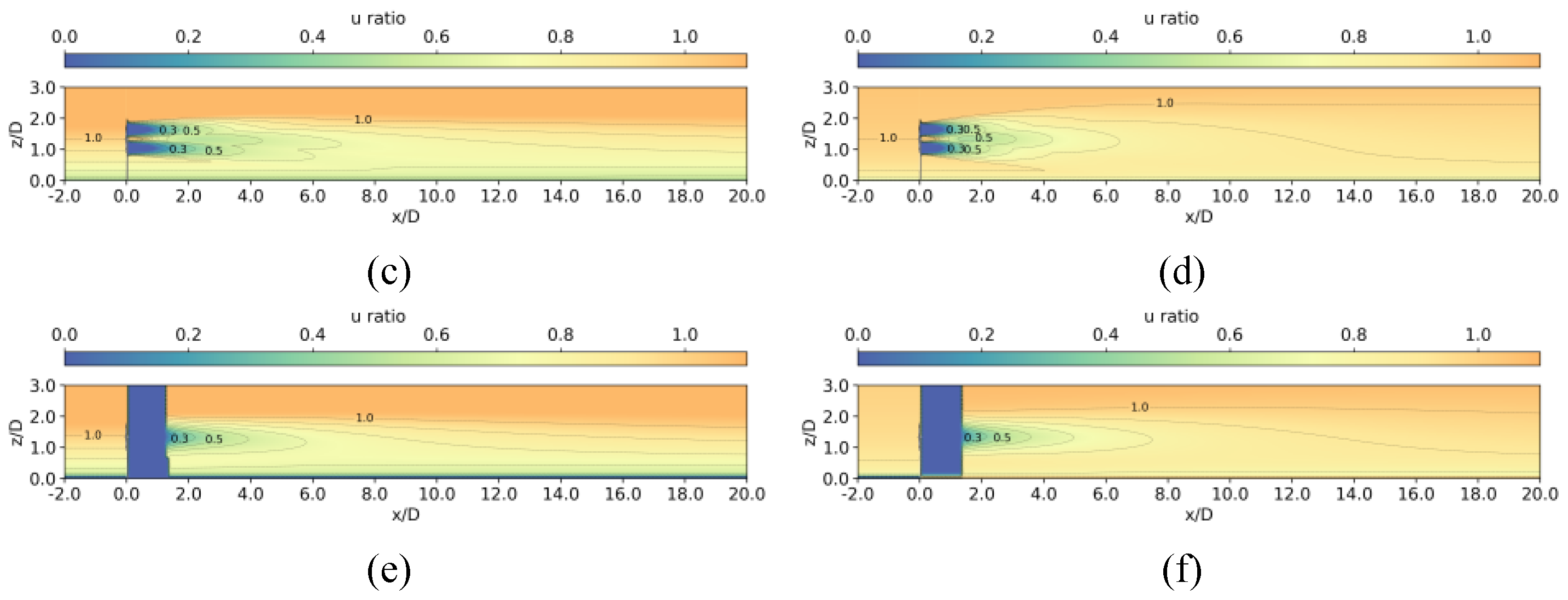

Figure 2.

Comparison of normalized wind speed profiles on the horizontal plane () for Case 1 under (a) stable, (b) unstable and (c) neutral atmospheric conditions.

Figure 2.

Comparison of normalized wind speed profiles on the horizontal plane () for Case 1 under (a) stable, (b) unstable and (c) neutral atmospheric conditions.

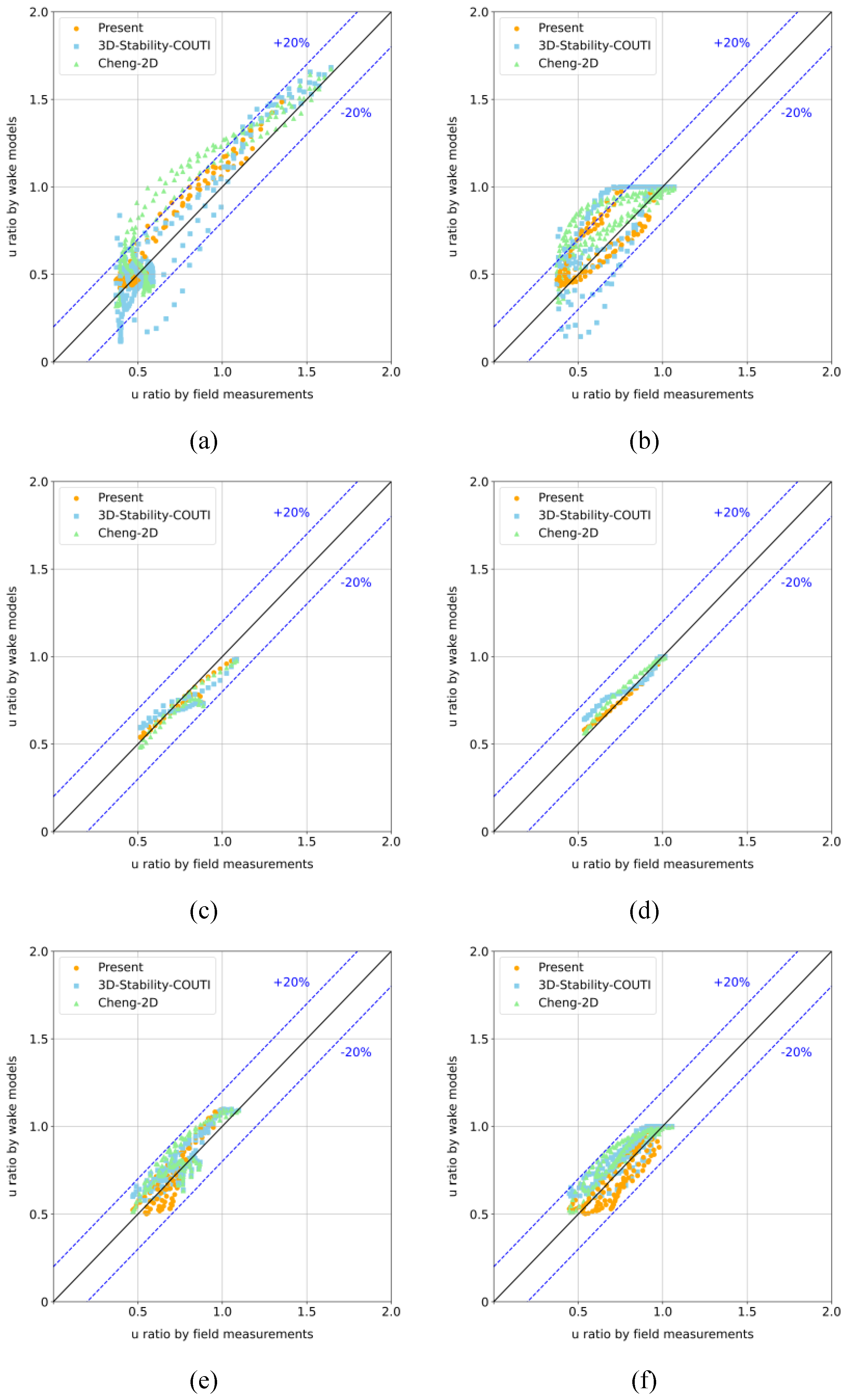

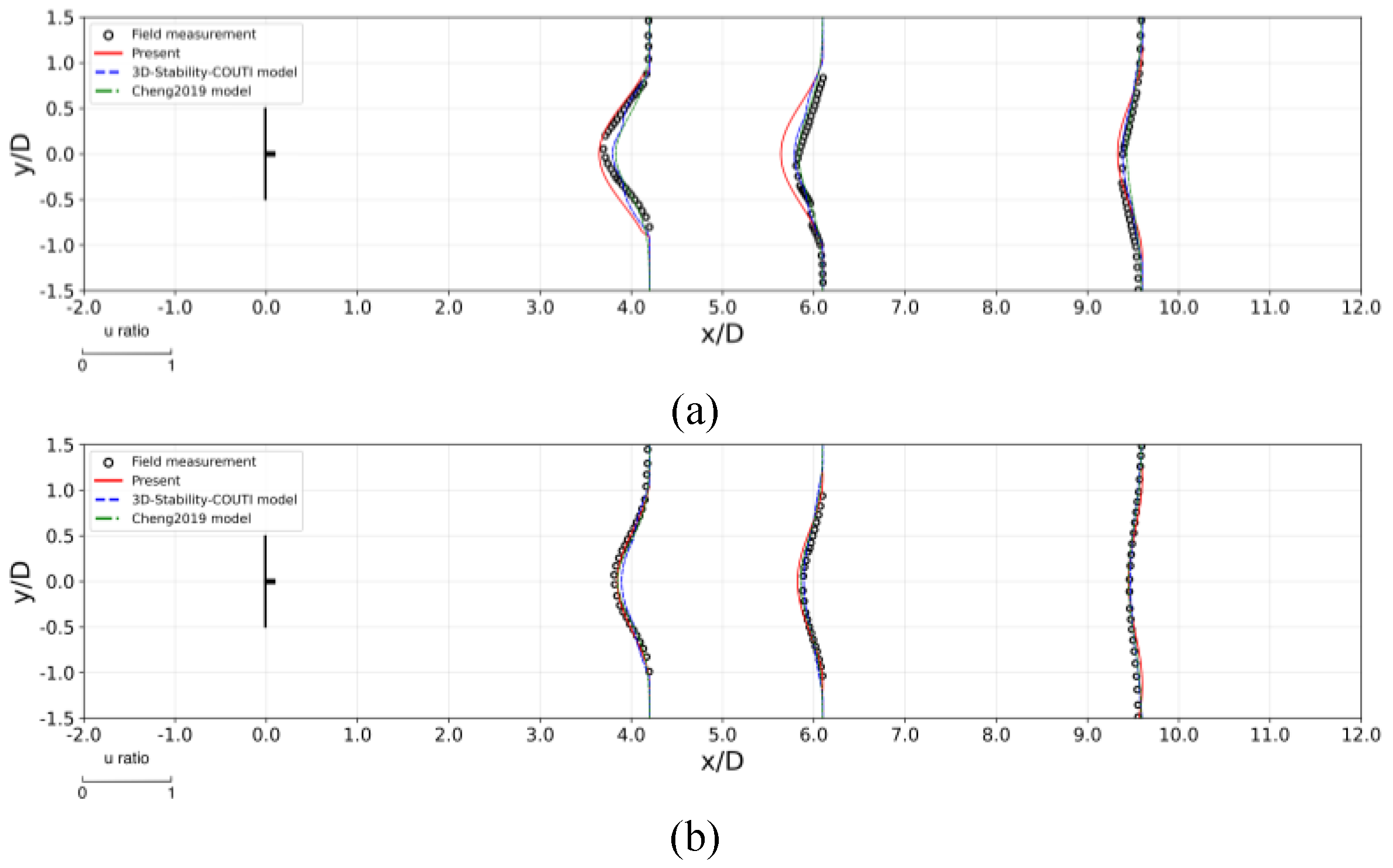

Figure 3.

Validation metrics of predicted normalized wind speed against field measurements of Case 1 for: (a) vertical profile at under stable atmopheric condition; (b) horizontal profile at under stable atmospheric condition; (c) vertical profile at under unstable atmopheric condition; (d) horizontal profile at under unstable atmospheric condition; (e) vertical profile at under neutral atmopheric condition; (f) horizontal profile at under neutral atmospheric condition.

Figure 3.

Validation metrics of predicted normalized wind speed against field measurements of Case 1 for: (a) vertical profile at under stable atmopheric condition; (b) horizontal profile at under stable atmospheric condition; (c) vertical profile at under unstable atmopheric condition; (d) horizontal profile at under unstable atmospheric condition; (e) vertical profile at under neutral atmopheric condition; (f) horizontal profile at under neutral atmospheric condition.

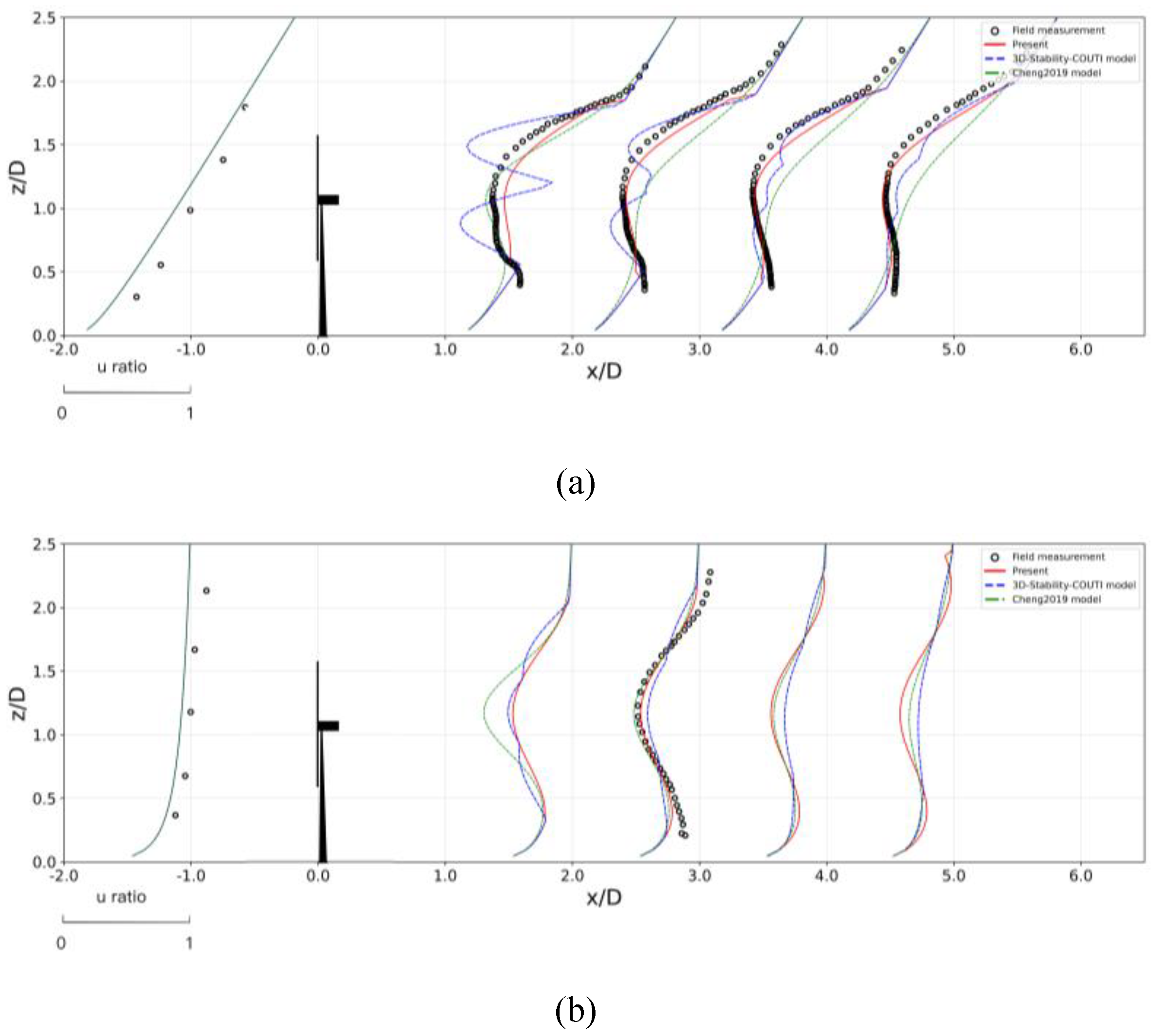

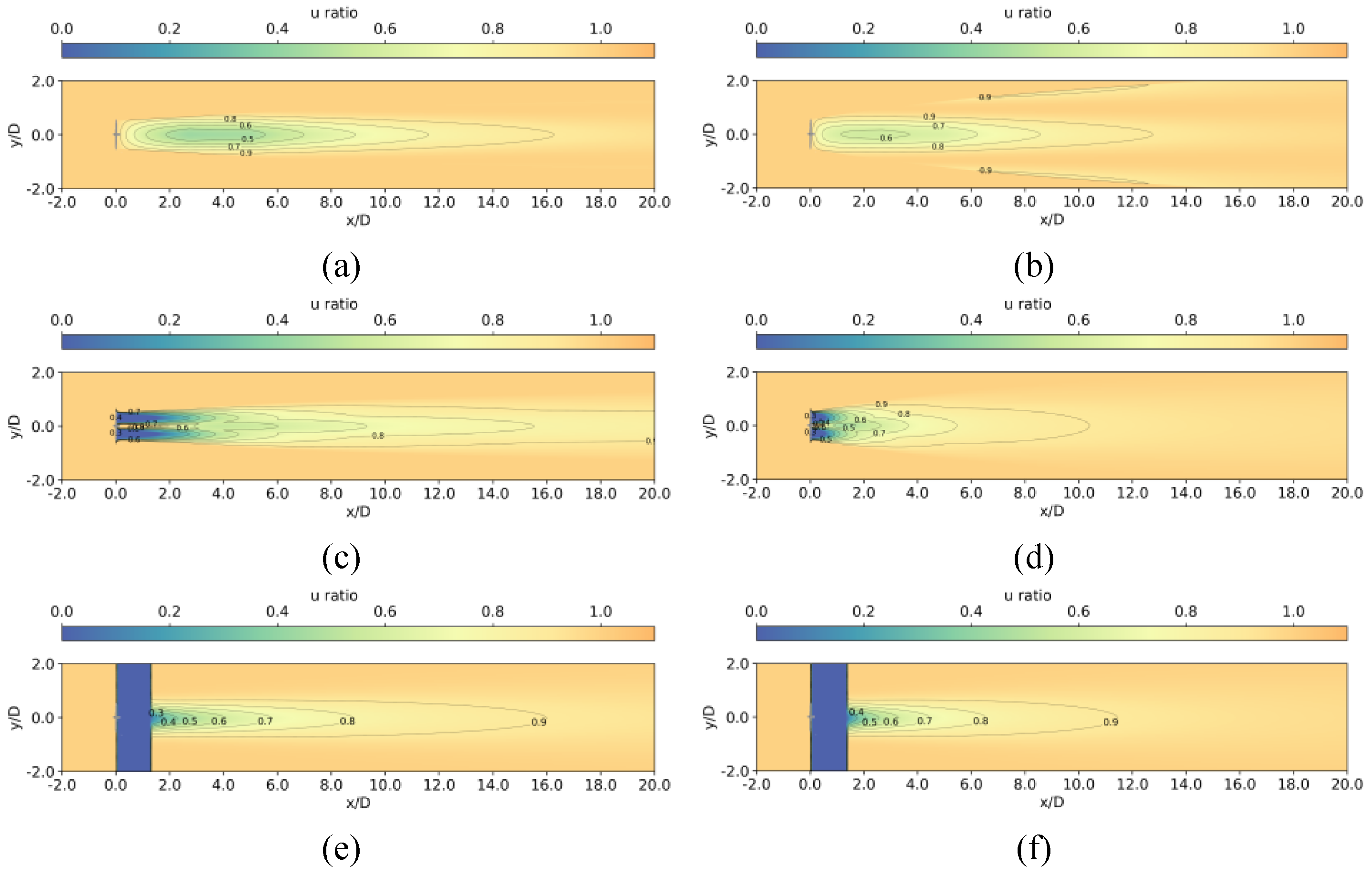

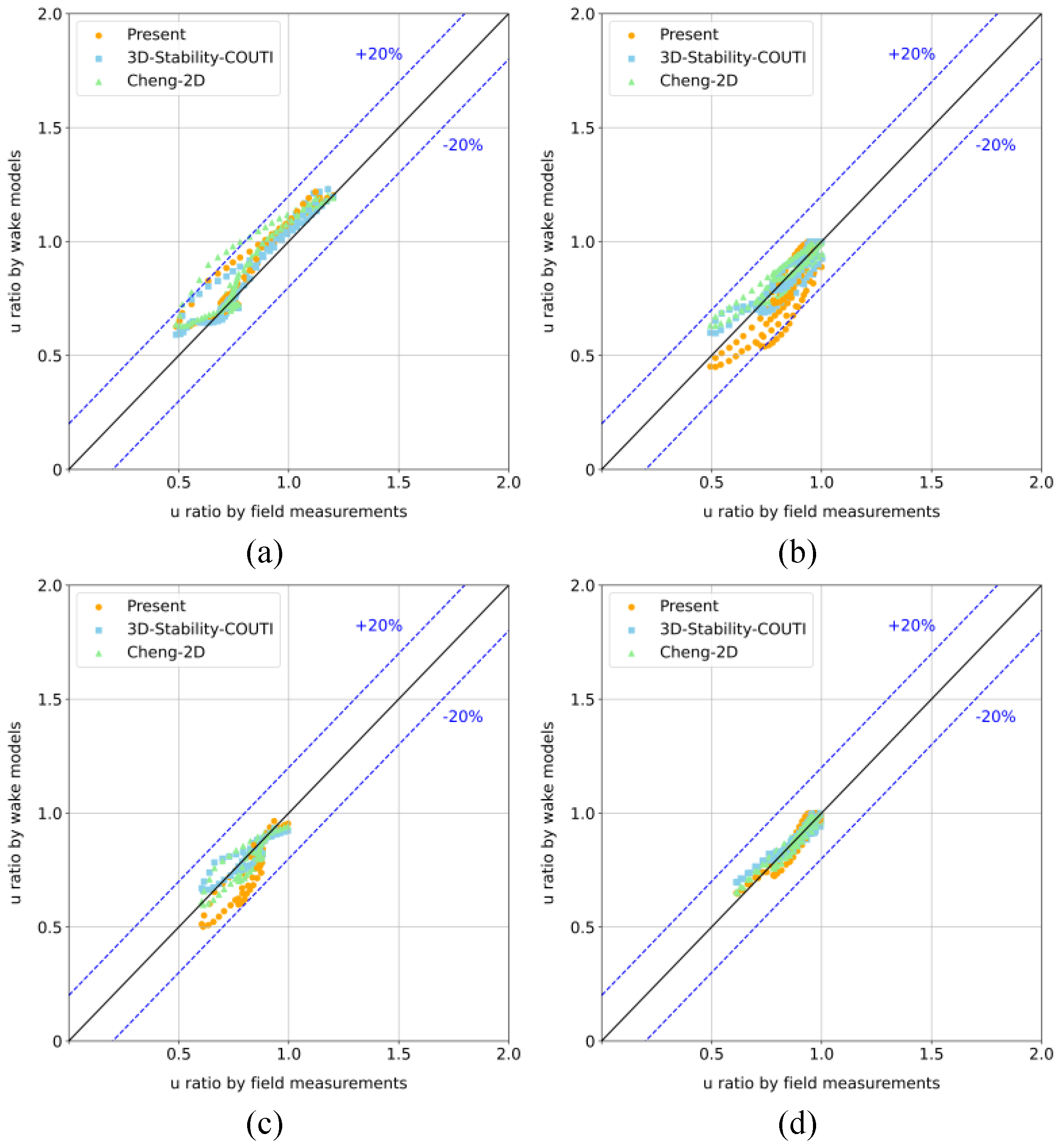

Figure 4.

Color maps of normalized wind speed on the horizontal place at hub height for Case 1 by (a) Present model under stable atmospheric condition; (b) Present model under unstable atmospheric condition; (c) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under stable atmospheric condition; (d) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under unstable atmospheric condition; (e) Cheng2019 model under stable atmospheric condition; (f) Cheng2019 model under unstable atmospheric condition.

Figure 4.

Color maps of normalized wind speed on the horizontal place at hub height for Case 1 by (a) Present model under stable atmospheric condition; (b) Present model under unstable atmospheric condition; (c) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under stable atmospheric condition; (d) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under unstable atmospheric condition; (e) Cheng2019 model under stable atmospheric condition; (f) Cheng2019 model under unstable atmospheric condition.

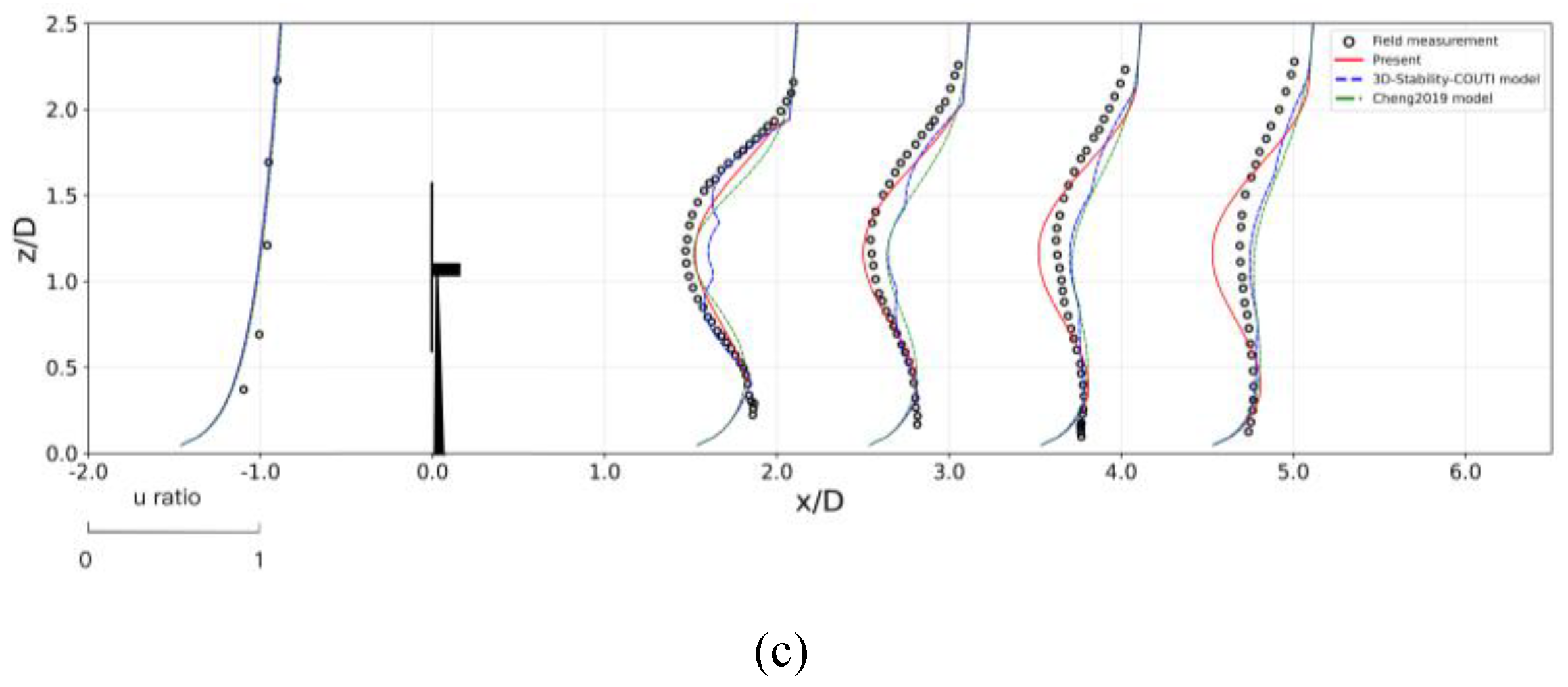

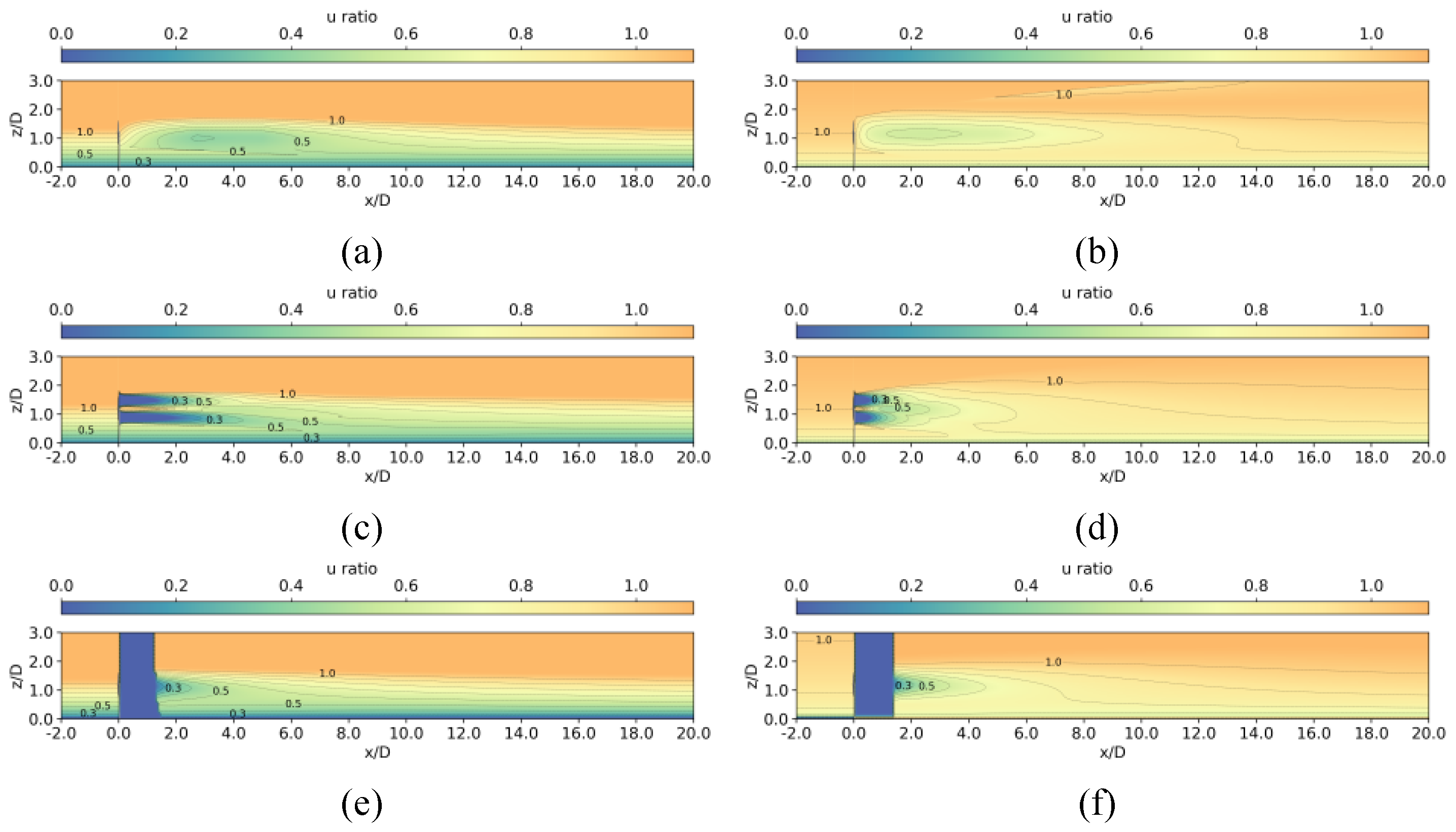

Figure 5.

Color maps of normalized wind speed on the vertical place at for Case 1 by (a) Present model under stable atmospheric condition; (b) Present model under unstable atmospheric condition; (c) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under stable atmospheric condition; (d) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under unstable atmospheric condition; (e) Cheng2019 model under stable atmospheric condition; (f) Cheng2019 model under unstable atmospheric condition.

Figure 5.

Color maps of normalized wind speed on the vertical place at for Case 1 by (a) Present model under stable atmospheric condition; (b) Present model under unstable atmospheric condition; (c) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under stable atmospheric condition; (d) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under unstable atmospheric condition; (e) Cheng2019 model under stable atmospheric condition; (f) Cheng2019 model under unstable atmospheric condition.

Figure 6.

Comparison of normalized wind speed profiles along the vertical centerline () for Case 2 under (a) stable and (b) unstable atmospheric conditions.

Figure 6.

Comparison of normalized wind speed profiles along the vertical centerline () for Case 2 under (a) stable and (b) unstable atmospheric conditions.

Figure 7.

Comparison of normalized wind speed profiles on the horizontal plane () for Case 2 under (a) stable and (b) unstable atmospheric conditions.

Figure 7.

Comparison of normalized wind speed profiles on the horizontal plane () for Case 2 under (a) stable and (b) unstable atmospheric conditions.

Figure 8.

Validation metrics of predicted normalized wind speed against field measurements of Case 2 for: (a) vertical profile at under stable atmopheric condition; (b) horizontal profile at under stable atmospheric condition; (c) vertical profile at under unstable atmopheric condition; (d) horizontal profile at under unstable atmospheric condition.

Figure 8.

Validation metrics of predicted normalized wind speed against field measurements of Case 2 for: (a) vertical profile at under stable atmopheric condition; (b) horizontal profile at under stable atmospheric condition; (c) vertical profile at under unstable atmopheric condition; (d) horizontal profile at under unstable atmospheric condition.

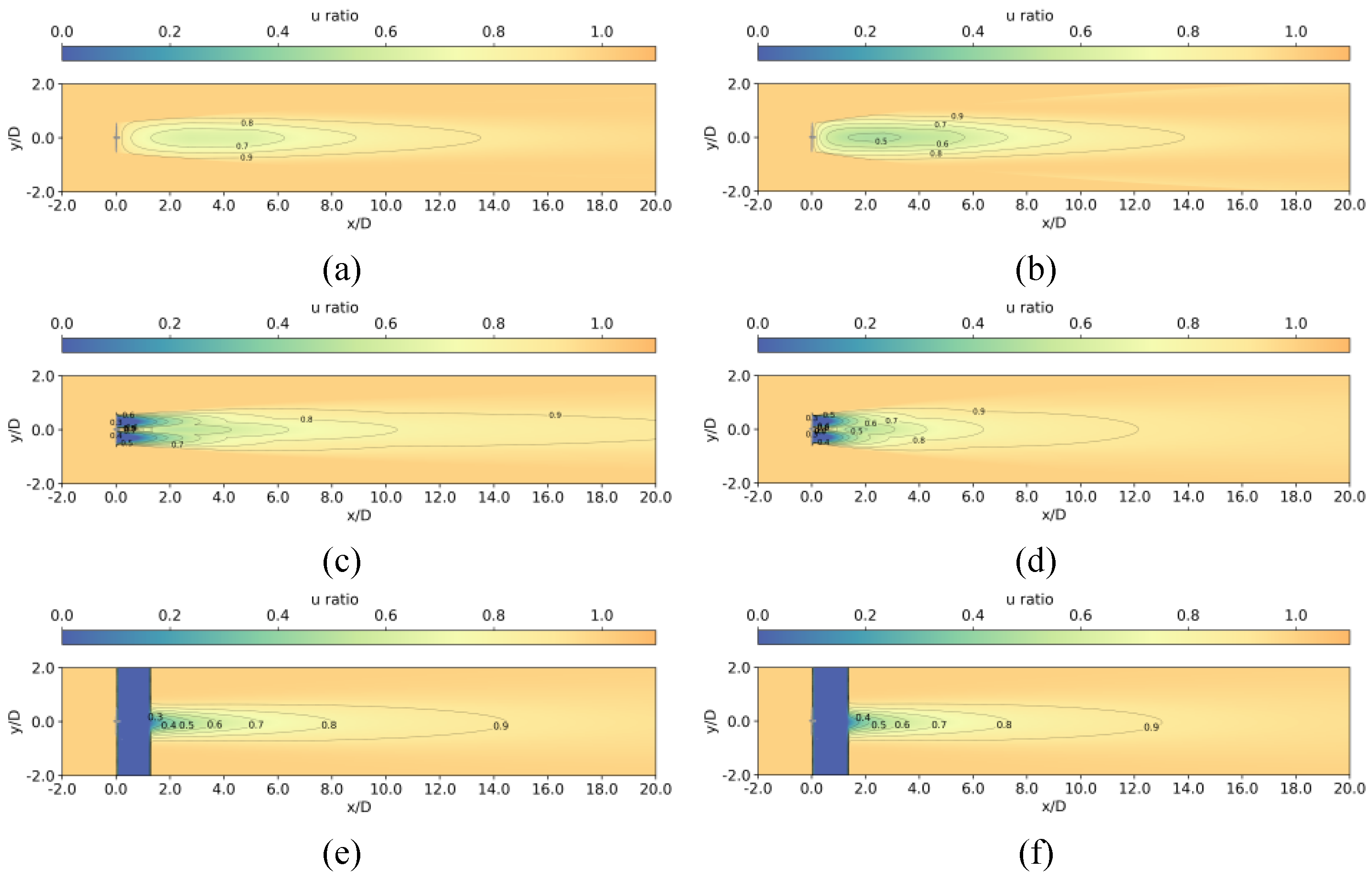

Figure 9.

Color maps of normalized wind speed on the horizontal place at hub height for Case 2 by (a) Present model under stable atmospheric condition; (b) Present model under unstable atmospheric condition; (c) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under stable atmospheric condition; (d) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under unstable atmospheric condition; (e) Cheng2019 model under stable atmospheric condition; (f) Cheng2019 model under unstable atmospheric condition.

Figure 9.

Color maps of normalized wind speed on the horizontal place at hub height for Case 2 by (a) Present model under stable atmospheric condition; (b) Present model under unstable atmospheric condition; (c) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under stable atmospheric condition; (d) 3D-Stability-COUTI model under unstable atmospheric condition; (e) Cheng2019 model under stable atmospheric condition; (f) Cheng2019 model under unstable atmospheric condition.

Table 1.

Key input parameters for the present wake model, the 3D-Stability-COUTI model [

29] and the Cheng2019 model [

28].

Table 1.

Key input parameters for the present wake model, the 3D-Stability-COUTI model [

29] and the Cheng2019 model [

28].

| Wake model considering atmospheric stability |

Present wake model |

3D-Stability-COUTI model [29] |

Cheng2019 model [28] |

| WInd turbine |

Rotor diameter, |

○ |

○ |

○ |

| Hub height, |

○ |

○ |

○ |

| Thrust coefficient curve, |

○ |

○ |

○ |

| Atmospheric inflow |

Monin-Obukhov length, |

○ |

○ |

○ |

| Wind speed at hub height, |

○ |

○ |

○ |

| Turbulence intensity at hub height, |

○ |

○ |

○ |

| Terrain |

Surface roughness length, |

○ |

○ |

○ |

| Angle of latitude, |

× |

× |

○ |

Table 2.

Comparison of analytical formulas for wake models considering atmospheric stability.

Table 2.

Comparison of analytical formulas for wake models considering atmospheric stability.

| Wake model considering atmospheric stability |

Proposed wake model |

3D-Stability-COUTI model [29] |

Wake model based on Monin-Obukhov similarity theory [28] |

| Inflow |

Incoming flow |

Incoming wind velocity, |

where and |

where ;

|

| Incoming turbulence intensity, |

|

where for and 7 for |

| Wake model |

Wake geometry |

Width, |

where

|

where ; ; ; ; |

| Wake velocity |

Wake velocity, |

where velocity deficit,

; ; ;

|

where velocity deficit,

and ; ;;;

|

where velocity deficit, and ; ; |

Table 3.

Summary of input parameters for Case 1 under neutral, unstable and stable atmospheric conditions.

Table 3.

Summary of input parameters for Case 1 under neutral, unstable and stable atmospheric conditions.

| Atmospheric stability |

Stable |

Unstable |

Neutral |

| Rotor diameter, D(m) |

27 |

27 |

27 |

| Hub height, zH(m) |

32.1 |

32.1 |

32.1 |

| Wind turbine location, Φ (°) |

33.60795 |

33.60795 |

33.60795 |

| Surface roughness height, z0(m) |

0.0275 |

0.0275 |

0.0275 |

| Thrust coefficient, Ct

|

0.83 |

0.81 |

0.70 |

| Wind speed at hub height, UH

|

4.8 |

6.7 |

8.7 |

Turbulence intensity at

hub height, IH

|

0.034 |

0.126 |

0.107 |

| Obukhov length, L(m) |

8.69 |

-112.36 |

2500 |

Table 4.

Hit rates of predicted wind speed against field measurements of Case 1 by Present model, 3D-Stability-COUTI model and Cheng2019 model.

Table 4.

Hit rates of predicted wind speed against field measurements of Case 1 by Present model, 3D-Stability-COUTI model and Cheng2019 model.

| Hit rate |

Atmospheric stability |

Plane |

Present model |

3D-Stability-COUTI |

Cheng2019 |

|

stable |

XOZ |

0.94 |

0.83 |

0.73 |

| XOY |

0.73 |

0.59 |

0.65 |

| unstable |

XOZ |

0.97 |

0.97 |

0.97 |

| XOY |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| neutral |

XOZ |

0.98 |

0.99 |

0.87 |

| XOY |

0.96 |

0.95 |

0.87 |

|

stable |

XOZ |

0.99 |

0.91 |

0.82 |

| XOY |

0.87 |

0.69 |

0.74 |

| unstable |

XOZ |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| XOY |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| neutral |

XOZ |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| XOY |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

Table 5.

Summary of input parameters for Case 2 under neutral, unstable and stable atmospheric conditions.

Table 5.

Summary of input parameters for Case 2 under neutral, unstable and stable atmospheric conditions.

| Atmospheric stability |

Stable |

Unstable |

| Rotor diameter, D(m) |

23 |

23 |

| Hub height, zH(m) |

31 |

31 |

| Wind turbine location, Φ (°) |

57.47467 |

57.47467 |

| Surface roughness height, z0(m) |

0.0005 |

0.0005 |

| Thrust coefficient, Ct

|

0.82 |

0.82 |

| Wind speed at hub height, UH

|

8.0 |

8.0 |

Turbulence intensity at

hub height, IH

|

0.085 |

0.085 |

| Obukhov length, L(m) |

35 |

100 |

Table 6.

Hit rates of predicted wind speed against field measurements of Case 2 by Present model, 3D-Stability-COUTI model and Cheng2019 model.

Table 6.

Hit rates of predicted wind speed against field measurements of Case 2 by Present model, 3D-Stability-COUTI model and Cheng2019 model.

| Hit rate |

Atmospheric stability |

Plane |

Present model |

3D-Stability-COUTI |

Cheng2019 |

|

stable |

XOZ |

0.93 |

0.97 |

0.89 |

| XOY |

0.83 |

1.00 |

0.99 |

| unstable |

XOZ |

0.90 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| XOY |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

stable |

XOZ |

1.00 |

1.00 |

0.93 |

| XOY |

0.93 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| unstable |

XOZ |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| XOY |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |