Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

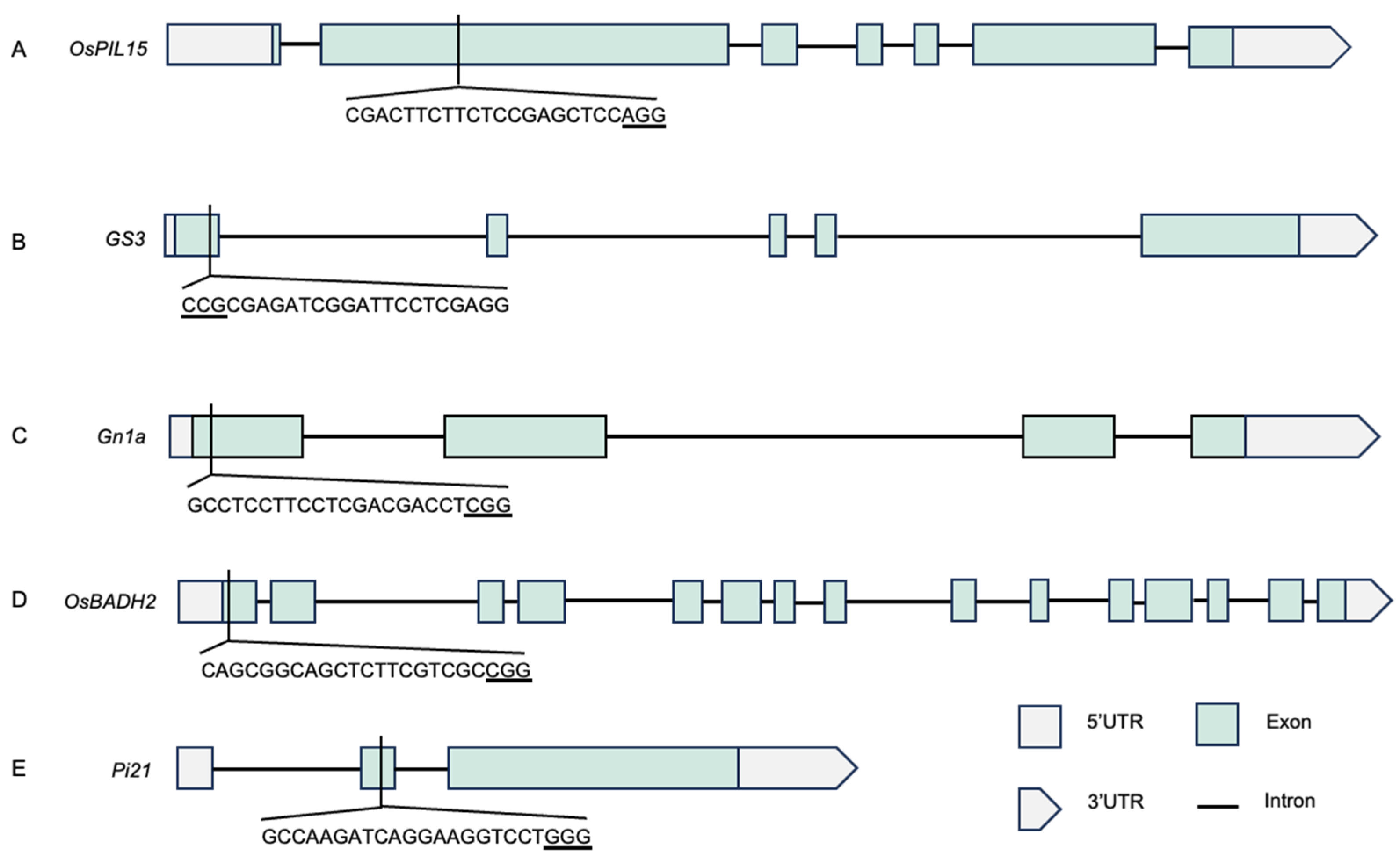

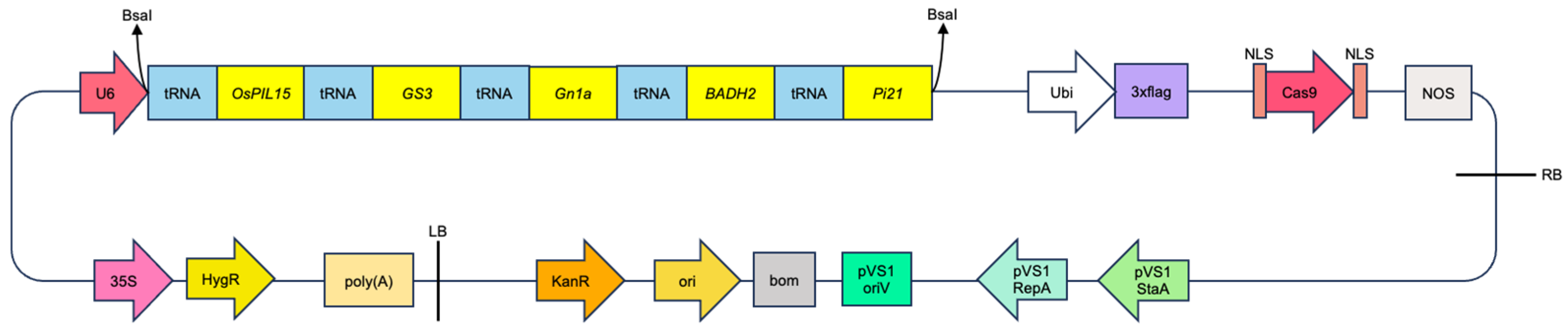

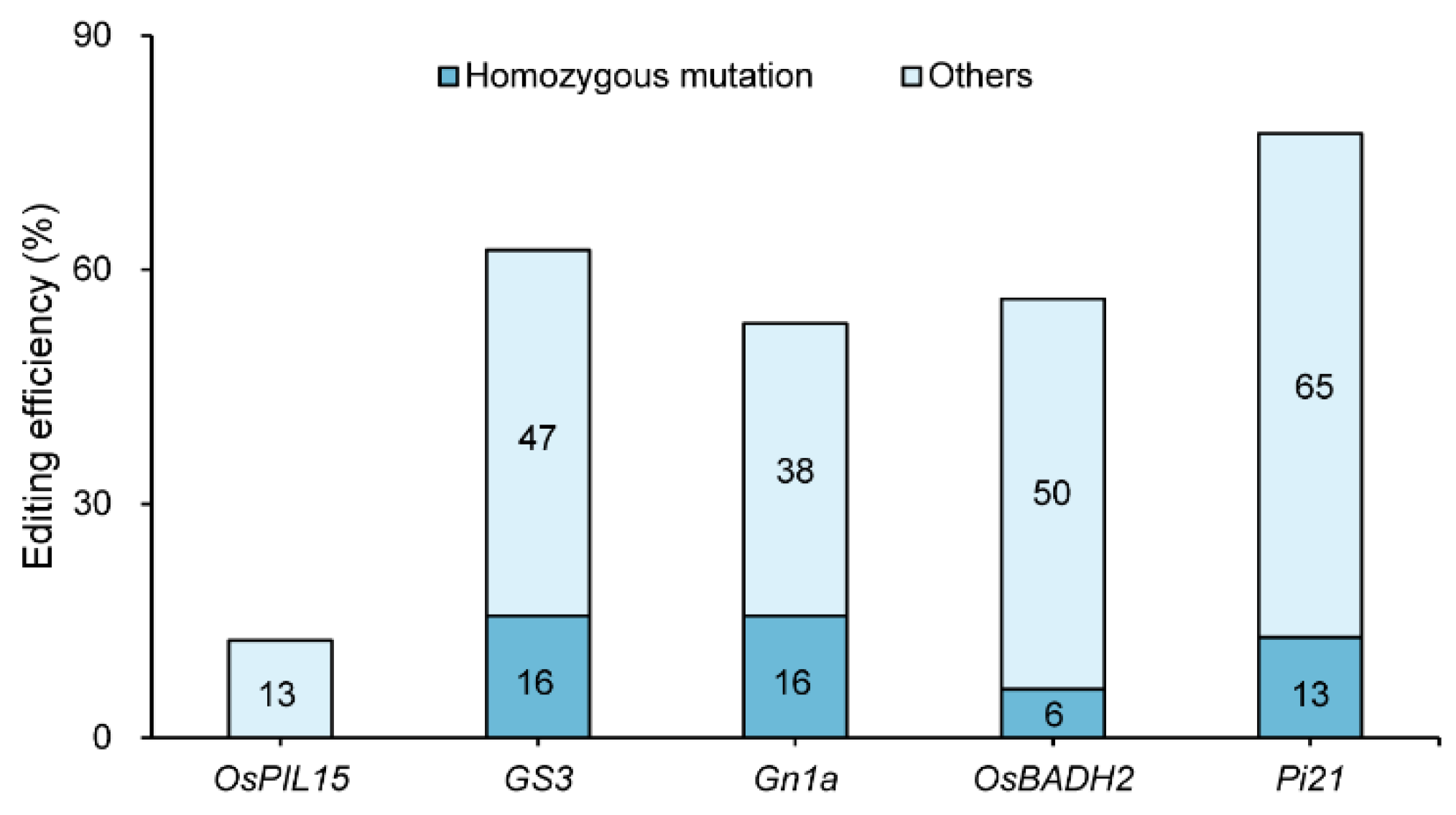

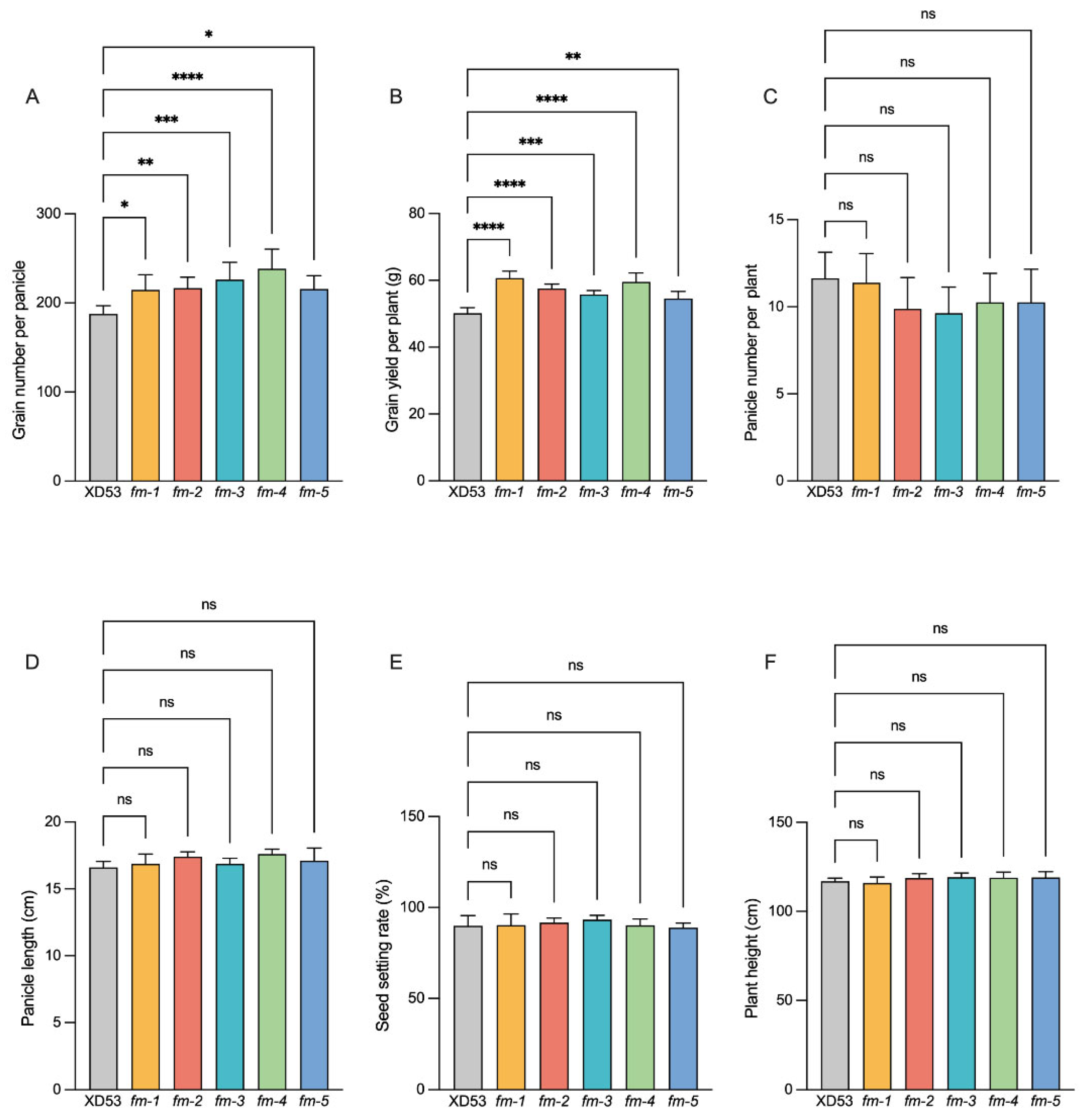

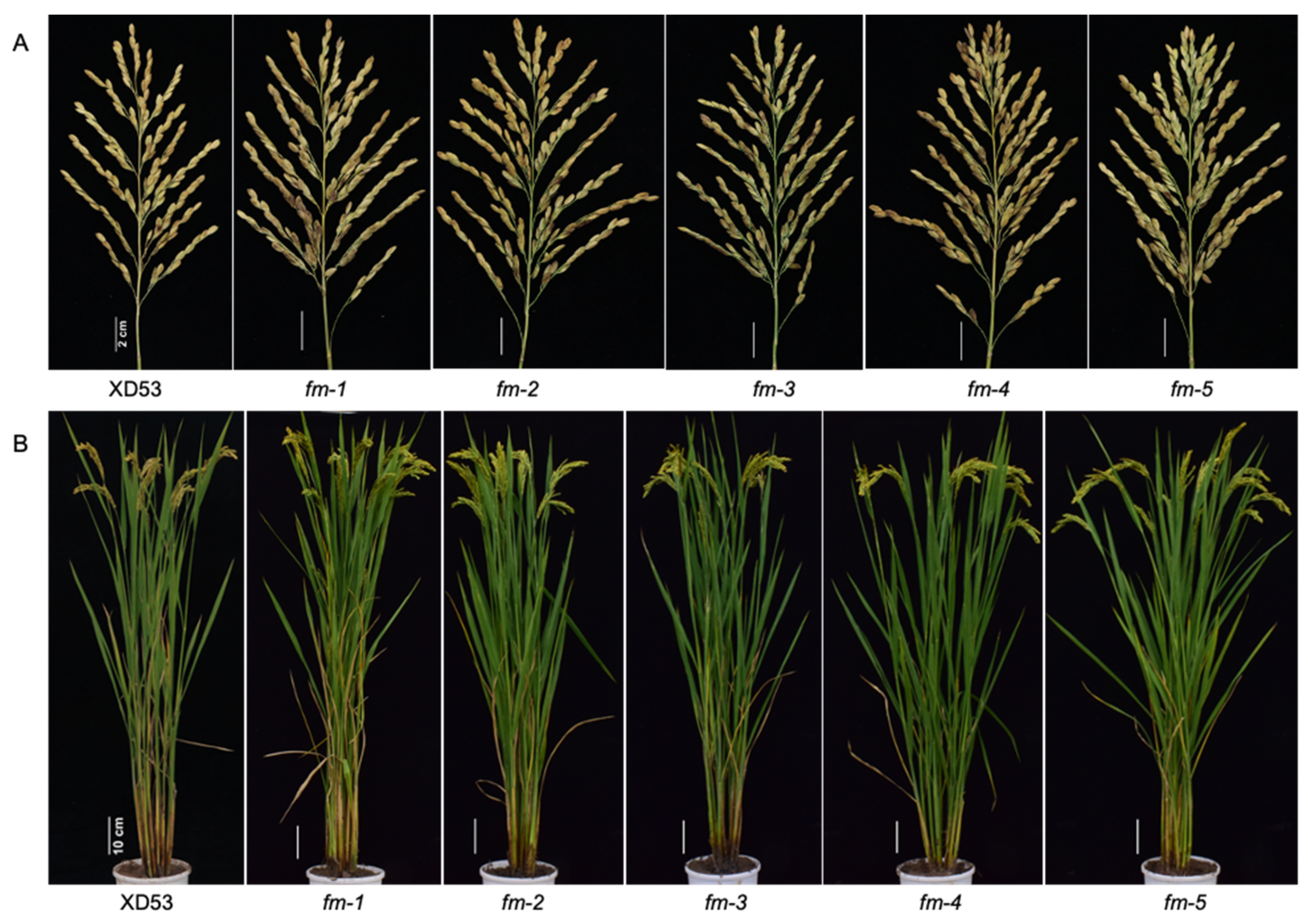

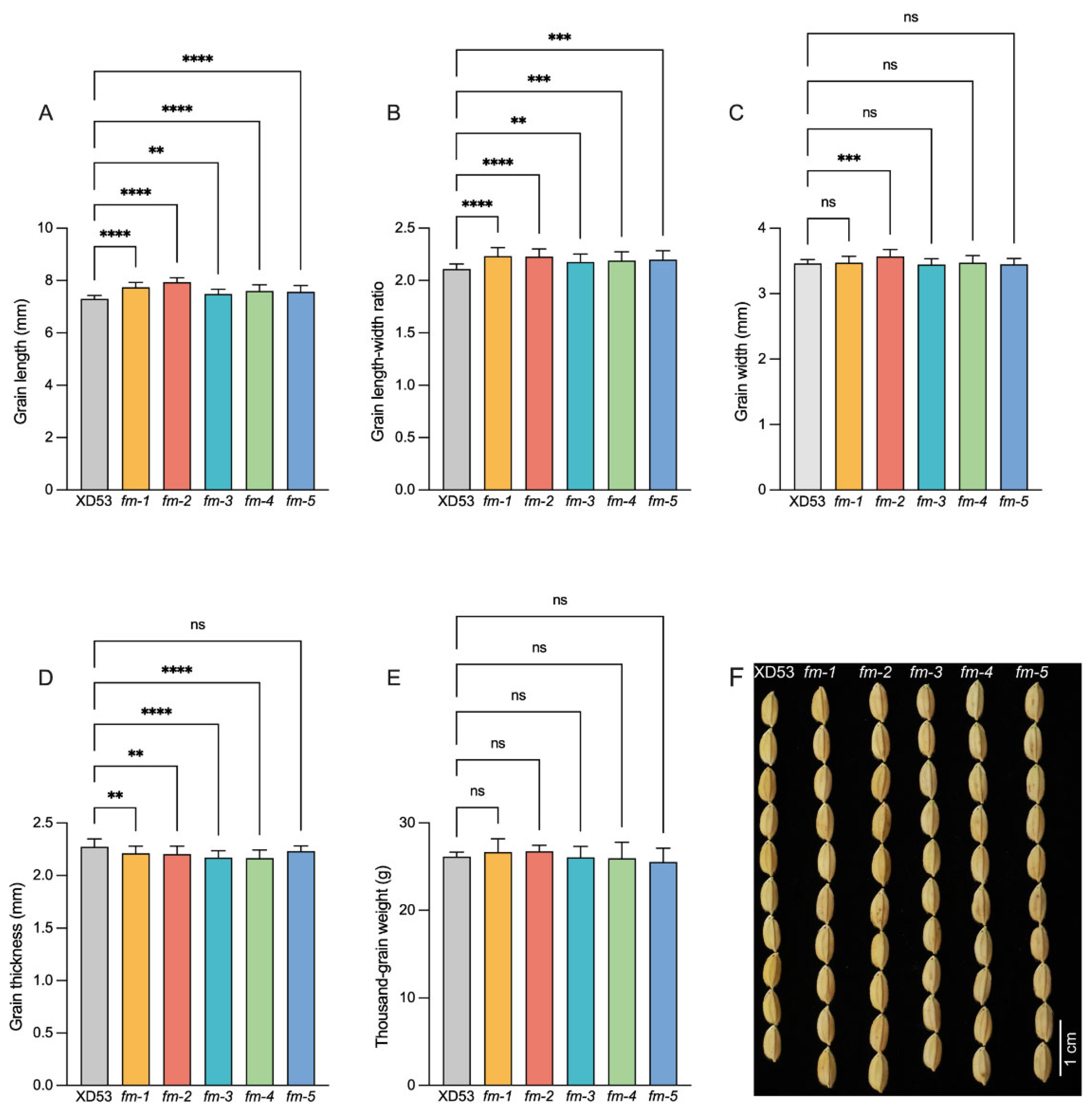

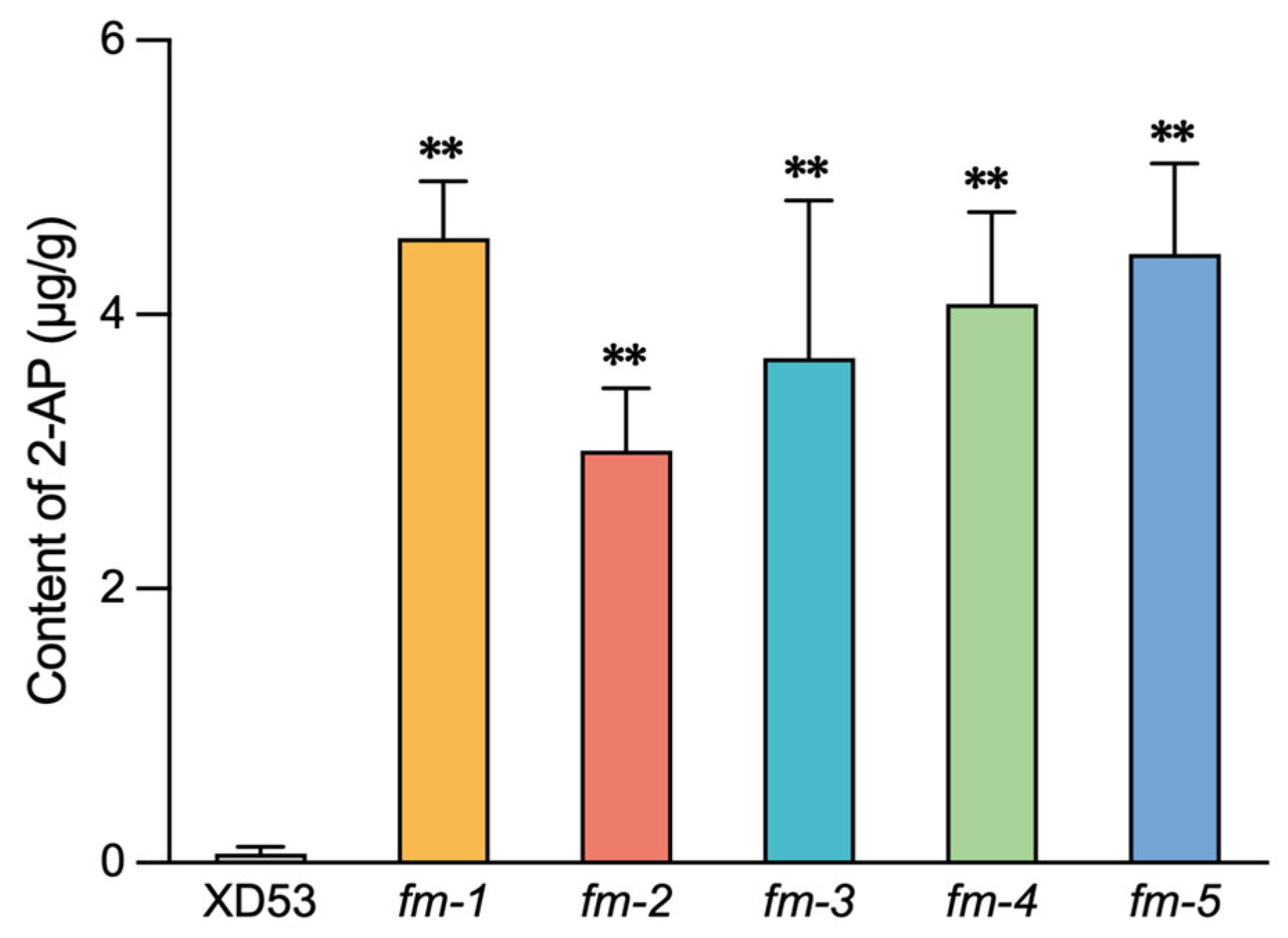

Background: The coordinated improvement of yield, quality and resistance is a primary goal in rice breeding. Gene editing technology is a novel method for precise multiplex gene improvement. Methods: In this study, we constructed a multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 vector targeting yield-related genes (GS3, OsPIL15, Gn1a), fragrance gene (OsBADH2), and rice blast resistance gene (Pi21) to pyramid traits for enhanced yield, quality, and disease resistance in rice. A tRNA-assisted CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex gene editing vector, M601-OsPIL15/GS3/Gn1a/OsBADH2/Pi21-gRNA, was constructed. Genetic transformation was performed via Agrobacterium-mediated method. Mutation editing efficiency was detected in T0 transgenic plants. Grain length, grain number per panicle, 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (2-AP) content, and rice blast resistance of homozygous lines were measured in the T2 generations. Results: Effectively edited plants were obtained in the T0 generation. The simultaneous editing efficiency for all five genes reached 9.38%. The individual gene editing efficiencies for Pi21, GS3, OsBADH2, Gn1a, and OsPIL15 were 78%, 63%, 56%, 54%, and 13%, respectively. Five five-gene homozygous edited lines with two genotypes were selected in the T2 generation. Compared with the wild-type (WT), the edited homozygous lines showed increased grain length (2.46%–8.62%), increased grain length-width ratio (3.31%–5.67%), increased grain number per panicle (14.47%–27.11%), a 42–64 folds increase in the fragrant substance 2-AP content, and significantly enhanced rice blast resistance. Meanwhile, there were no significant changes in other agronomic traits. Conclusions: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multiplex gene editing technology enabled the simultaneous editing of genes related to rice yield, quality, and disease resistance. This provides an effective approach for obtaining new japonica rice germplasm with blast resistance, long grains, and fragrance.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Cultivation Methods

2.2. Construction of CRISPR/Cas9 Expression Vector

2.3. Acquisition and Detection of Transgenic Plants

2.4. Investigation of Yield-Related Traits

2.5. Determination of Fragrance Substance Content

2.6. Identification of Rice Blast Resistance

3. Results

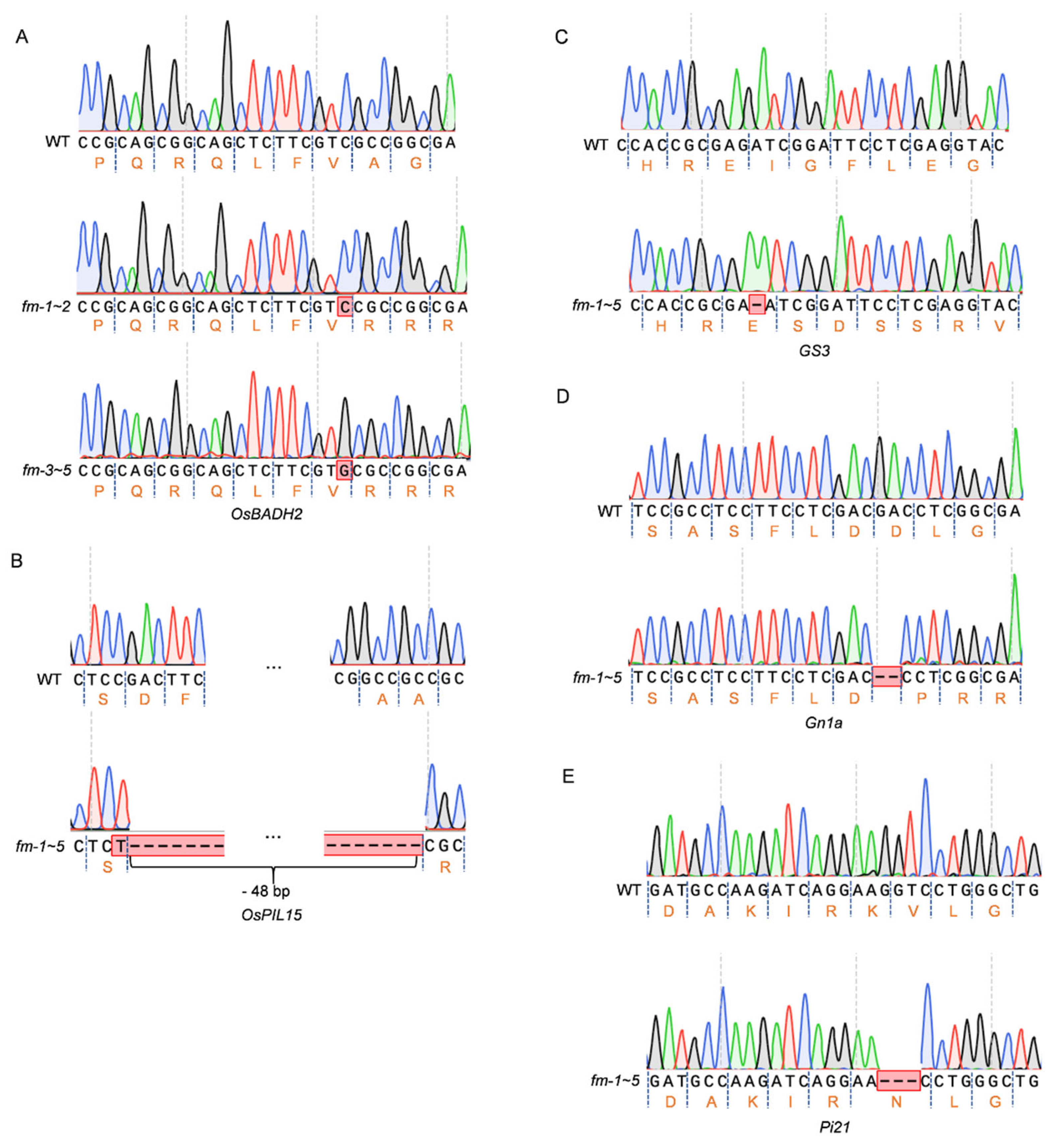

3.1. Analysis of Editing Efficiency of T0 Generation Transgenic Plants

3.2. Screening and Identification of Homozygous Mutant Lines of Five Genes

3.3. Analysis of Yield Traits of Homozygous Edited Lines

3.4. Analysis of Grain Phenotype of Homozygous Edited Lines

3.5. Fragrance Analysis of Homozygous Edited Lines

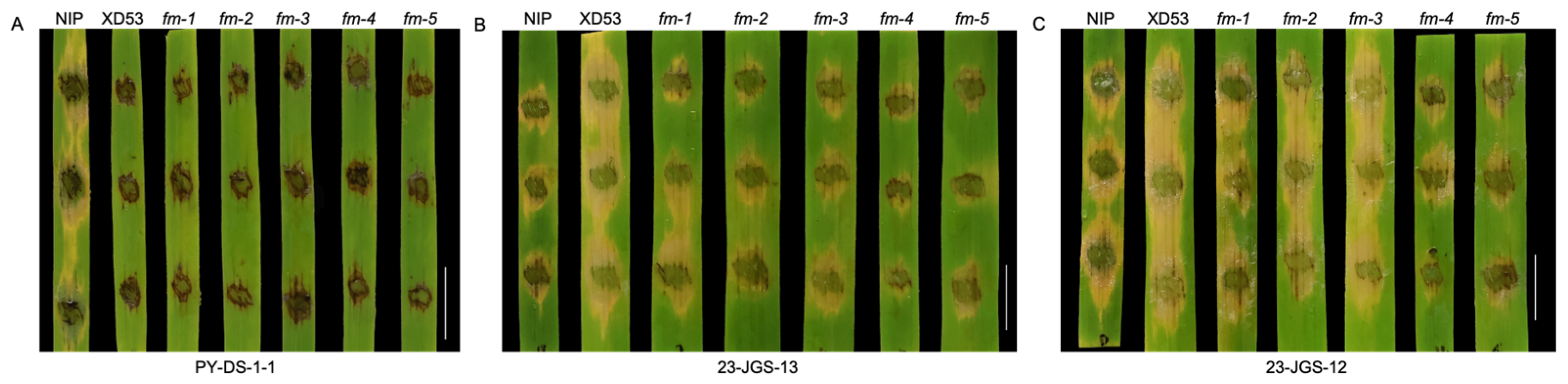

3.6. Rice Blast Resistance Analysis of Homozygous Edited Lines

4. Discussion

4.1. Innovation and Comparison of Multiplex gene Editing Vector Construction Strategies

4.2. Mechanism Analysis and Optimization Strategies for Differences in Multiplex Gene Editing Efficiency

4.3. Effects of Multiplex gene Editing on Phenotypes

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xing, Y.Z.; Zhang, Q.F. Genetic and molecular bases of rice yield. Annu Rev Plant. Biol. 2010, 61, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.X.; Ye, C.; Han, P.J.; Sheng, Y.L.; Li, F.; Sun, H.Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.Z. The molecular mechanism of transcription factor regulation of grain size in rice. Plant Sci. 2025, 354, 112434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Markkandan, K.; Koo, Y.J.; Song, J.T.; Seo, H.S. GW2 Functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase for rice expansin-like 1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.S.; Wu, K.; Wang, B.; Liu, H.H.; Guo, S.Y.; Guo, X.Y.; Luo, W.; Sun, S.Y.; Ouyang, Y.D.; Fu, X.D.; et al. The RING E3 ligase CLG1 targets GS3 for degradation via the endosome pathway to determine grain size in rice. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 1699–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.Y.; Wang, L.; Mao, H.L.; Shao, L.; Li, X.H.; Xiao, J.H.; Ouyang, Y.D.; Zhang, Q.F. A G-protein pathway determines grain size in rice. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.C.; Hu, Q.F.; Gong, N.; Yan, H.M.; Khan, N.U.; Du, Y.X.; Sun, H.Z.; Zhao, Q.Z.; Peng, W.X.; Li, Z.C.; et al. Natural variation in MORE GRAINS 1 regulates grain number and grain weight in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1440–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.G.; Rao, Y.C.; Zeng, D.L.; Yang, Y.L.; Xu, R.; Zhang, B.L.; Dong, G.J.; Qian, Q.; Li, Y.H. SMALL GRAIN 1, which encodes a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4, influences grain size in rice. Plant J. 2014, 77, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Chen, K.; Dong, N.Q.; Shi, C.L.; Ye, W.W.; Gao, J.P.; Shan, J.X.; Lin, H.X. GRAIN SIZE AND NUMBER1 negatively regulates the OsMKKK10-OsMKK4-OsMPK6 cascade to coordinate the trade-off between grain number per panicle and grain size in rice. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.C.; Xing, Y.Z.; Mao, H.L.; Lu, T.T.; Han, B.; Xu, C.G.; Li, X.H.; Zhang, Q.F. GS3, a major QTL for grain length and weight and minor QTL for grain width and thickness in rice, encodes a putative transmembrane protein. Theor Appl Genet. 2006, 112, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.F.; Chen, J.; Zheng, X.M.; Wu, F.Q.; Lin, Q.B.; Heng, Y.Q.; Tian, P.; Cheng, Z.J.; Yu, X.W.; Zhou, K.N.; et al. GW5 acts in the brassinosteroid signalling pathway to regulate grain width and weight in rice. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 17043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Du, Y.X.; Li, F.; Sun, H.Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.Z.; Peng, T.; Xin, Z.Y.; Zhao, Q.Z. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, OsPIL15, regulates grain size via directly targeting a purine permease gene OsPUP7 in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019, 17, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikari, M.; Sakakibara, H.; Lin, S.Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Takashi, T.; Nishimura, A.; Angeles, E.R.; Qian, Q.; Kitano, H.; Matsuoka, M. Cytokinin oxidase regulatesrice grain production. Science 2005, 309, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.H.; Yang, Y.; Shi, W.W.; Ji, Q.; He, F.; Zhang, Z.D.; Cheng, Z.K.; Liu, X.N.; Xu, M.L. Badh2, encoding betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase, inhibits the biosynthesis of 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline, a major component in rice fragrance. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1850–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Q.W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.L.; Zhang, K.; Gao, C.X. Creation of fragrant rice by targeted knockout of the OsBADH2 gene using TALEN technology. Plant Biotechnol J. 2015, 13, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuoka, S.; Saka, N.; Koga, H.; Ono, K.; Shimizu, T.; Ebana, K.; Hayashi, N.; Takahashi, A.; Hirochika, H.; Okuno, K.; Yano, M. Loss of function of a proline-containing protein confers durabledisease resistance in rice. Science 2009, 325, 998–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.T.; Fu, Y.; Li, M.; Xiong, S.T.; Huang, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Liang, X.Y.; Wang, W.L.; Tang, K.X.; et al. Biofortification of tomatoes with beta-carotene through targeted gene editing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2025, 327, 147396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.M.; Li, S.Y.; Xu, J.J.; Yan, L.; Ma, L.Q.; Xia, L.Q. Pyramiding favorable alleles in an elite wheat variety in one generation by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated multiplex gene editing. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 847–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, A.R.; Chen, K.; Soczek, K.M.; Tuck, O.T.; Doherty, E.E.; Xu, B.; Trinidad, M.I.; Thornton, B.W.; Yoon, P.H.; Doudna, J.A. Rapid DNA unwinding accelerates genome editing by engineered CRISPR-Cas9. Cell 2024, 187, 3249–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hou, H.N.; Song, M.L.; Chen, Z.; Peng, T.; Du, Y.X.; Zhao, Y.F.; Li, J.Z.; Miao, C.B. Targeted insertion of large DNA fragments through template-jumping prime editing in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2025, 23, 2645–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.G.; Meng, X.B.; Guo, H.Y.; Cheng, Q.; Jing, Y.H.; Chen, M.J.; Liu, G.F.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.H.; Li, J.Y.; et al. Targeting a gene regulatory element enhances rice grain yield by decoupling panicle number and size. Nat. Biotechnol 2022, 40, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.Y.; Gou, Y.J.; Heng, Y.Q.; Ding, W.Y.; Li, Y.J.; Zhou, D.G.; Li, X.Q.; Liang, C.R.; Wu, C.Y.; Wang, H.Y.; et al. Targeted manipulation of grain shape genes effectively improves outcrossing rate and hybrid seed production in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023, 21, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.N.; Fu, X.; Qi, X.T.; Xiao, B.; Liu, C.L.; Wu, Q.Y.; Zhu, J.J.; Xie, C.X. Harnessing haploid-inducer mediated genome editing for accelerated maize variety development. Plant Biotechnol J. 2025, 23, 1604–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.G.; Wang, C.L.; Chen, F.Y.; Qin, W.C.; Yang, H.; Zhao, S.H.; Xia, J.L.; Du, X.; Zhu, Y.F.; Wu, L.S.; et al. Maize smart-canopy architecture enhances yield at high densities. Nature 2024, 632, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Zhang, Y.F.; Kang, Z.S.; Mao, H.D. Improvement of wheat drought tolerance through editing of TaATX4 by CRISPR/Cas9. J. Genet. Genomics 2023, 50, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Z.; Zhang, S.J.; Li, J.H.; Gao, J.; Song, G.Q.; Li, W.; Geng, S.F.; Liu, C.; Lin, Y.X.; Li, Y.L.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of TaDCL4, TaDCL5 and TaRDR6 induces male sterility in common wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023, 21, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asa, H.; Kuwabara, C.; Matsumoto, K.; Shigeta, R.; Yamamoto, T.; Masuda, Y.; Yamada, T. Simultaneous site-directed mutagenesis for soybean β-amyrin synthase genes via DNA-free CRISPR/Cas9 system using a single gRNA. Plant Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwabara, C.; Miki, R.; Maruyama, N.; Yasui, M.; Hamada, H.; Nagira, Y.; Hirayama, Y.; Ackley, W.; Li, F.; Imai, R.; et al. A DNA-free and genotype-independent CRISPR/Cas9 system in soybean. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 2320–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.F.; Wen, J.Y.; Zhao, W.B.; Wang, Q.; Huang, W.C. Rational improvement of rice yield and cold tolerance by editing the three genes OsPIN5b, GS3, and OsMYB30 with the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Front Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Yao, W.; Yin, Z.L.; Wang, Y.B.; Huang, Z.J.; Zhou, J.Q.; Liu, J.L.; Lu, X.D.; Wang, F.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated simultaneous mutation of three salicylic acid 5-hydroxylase (OsS5H) genes confers broad-spectrum disease resistance in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023, 21, 1873–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.F.; Yang, Y.C.; Qin, R.Y.; Li, H.; Qiu, C.H.; Li, L.; Wei, P.C.; Yang, J.B. Rapid improvement of grain weight via highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multiplex genome editing in rice. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2016, 43, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, C.; Gruetzner, R.; Kandzia, R.; Marillonnet, S. Golden gate shuffling: A one-pot DNA shuffling method based on type IIs restriction enzymes. PLoS One 2009, 4, e5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinstiver, B. P.; Pattanayak, V.; Prew, M.S.; Tsai, S.Q.; Nguyen, N.T.; Zheng, Z.L.; Joung, J.K. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature 2016, 529, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinstiver, B.P.; Tsai, S.Q.; Prew, M.S.; Nguyen, N.T.; Welch, M.M.; Lopez, J.M.; McCaw, Z.R.; Aryee, M.J.; Joung, J.K. Genome-wide specificities of CRISPR-Cas Cpf1 nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol 2016, 34, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhaj, K.; Chaparro-Garcia, A.; Kamoun, S.; Patron, N.J.; Nekrasov, V. Editing plant genomes with CRISPR/Cas9. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2015, 32, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Teng, F.; Li, T.D.; Zhou, Q. Simultaneous generation and germline transmission of multiple gene mutations in rat using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Biotechnol 2013, 31, 684–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knott, G.J.; Doudna, J.A. CRISPR-Cas guides the future of genetic engineering. Science 2018, 361, 866–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doench, J.G.; Hartenian, E.; Graham, D.B.; Tothova, Z.; Hegde, M.; Smith, I.; Sullender, M.; Ebert, B.L.; Xavier, R.J.; Root, D.E. Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene inactivation. Nat. Biotechnol 2014, 32, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, S.R.; Xu, J.; Sui, C.; Wei, J.H. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 in plant biology. Acta Pharm Sin B 2017, 7, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pribil, M.; Palmgren, M.; Gao, C.X. A CRISPR way for accelerating improvement of food crops. Nature Food 2020, 1, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Zhu, A.; Xue, P.; Wen, X.X.; Cao, Y.R.; Wang, B.F.; Zhang, Y.; Shah, L.; Cheng, S.H.; Cao, L.Y.; et al. Effects of GS3 and GL3.1 for grain size editing by CRISPR/Cas9 in rice. Rice Science 2020, 27, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.B.; Du, C.Y.; He, Y.N.; Zheng, C.K.; Sun, W.; Zhou, J.J.; Xie, L.X.; Jiang, C.H.; Xu, J.D.; Wang, F.; et al. Natural variation of Grain size 3 allele differentially functions in regulating grain length in xian/indica and geng/japonica rice. Euphytica 2024, 220, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.Y.; Chen, H.W.; Ng, C.Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Tseng, T.H.; Li, W.H.; Ku, M.S.B. Down-Regulation of cytokinin oxidase 2 expression increases tiller number and improves rice yield. Rice 2015, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).