1. Introduction

During pregnancy, inadequate placental development and subsequent dysfunction result in a range of adverse fetal and maternal outcomes [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The first trimester is a crucial time for the establishment of appropriate placentation, yet our current knowledge of early gestation is inadequate, and understanding of placental development and function throughout pregnancy is impeded in part by the lack of longitudinal access to the tissue. Nonhuman primates (NHP) are excellent animal models for pregnancy studies as they have long gestational periods and a hemochorial placenta structure similar to humans [

5]. NHP models enable highly translational longitudinal placental studies that improve our understanding of pregnancy and increase our ability to identify human pregnancies at risk for poor outcomes. We routinely perform non-invasive in vivo imaging using contrast-enhanced ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to examine placental hemodynamics and the contribution of blood flow to placental function in NHP models [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Traditionally, stages of placental development have been studied by collecting placental tissues after fetectomy at specific developmental ages to perform correlative in vitro studies for the assessment of functional read-outs in these NHP models. This required surgical pregnancy termination in multiple animals to characterize longitudinal changes throughout gestation, and it precluded prospective studies to match offspring outcomes with pregnancy pathology. Furthermore, the research-driven need for early gestation NHP placenta samples has increased the request for pregnancy termination in the first trimester. An alternative strategy would be to perform a minimally invasive ultrasound-guided procedure to obtain placental biopsies by chorionic villous sampling (CVS). This approach would decrease the number of animal subjects required and reduce the inherent variability between subjects.

The CVS technique is a common procedure performed in pregnant women, but the application of this method to NHP studies to date has been limited. In clinical obstetric practice, CVS is used to acquire placental tissue for prenatal diagnostic testing [

12,

13,

14]. The use of ultrasound guidance to track anatomical structures and landmarks has improved safety while performing minimally invasive procedures [

15]. However, there is a need to adequately train operators as they learn new techniques. The pregnant uterus increases complexity in training endeavors with additional skill required to avoid doing harm to the fetus when a needle is introduced into the in-utero environment. The complication rate of CVS varies within the available literature, but the reported rate of miscarriage is approximately 0.5% [

16] with a transcervical approach having a slightly higher risk than transabdominal in human patients subjects [

17]. In rhesus macaques, the presence of multiple colliculi in the cervical anatomy [

18] creates a tortuous path that impedes biopsy via a transcervical approach, thereby making transabdominal biopsy the best option in this animal model. In humans, for prenatal diagnostic testing very modest tissue amounts are needed (typically 5mg, [

14,

19]) and a cautious approach to minimize disruption of the placenta in situ is favorable to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes. For research purposes, the ability to collect a larger biopsy has the potential to facilitate multiple uses of the tissue in experimental analysis, yet care must still be taken not to perturb the placenta and jeopardize the pregnancy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Simulation Model

The use of a simulation training model for CVS assumes some prior experience by veterinarians with ultrasound. This may be in the context of the identification and basic assessment of pregnancy or somewhat more advanced with performing minimally invasive procedures. The ultrasound-guided introduction of a needle into a body cavity and the tracking and placement of the needle tip requires manual dexterity and precise coordinated movements. Simulation training is effective for developing these skills.

Figure 1 provides step by step instructions for the assembly of a CVS simulation model using materials to mimic the consistency of the maternal abdomen (zipper bag), uterus (silicone pastry bag), placenta (tofu block), and amniotic cavity (water-filled condom), as developed and described by Nitsche et al. [

15]. For this study, the surgical veterinarians at the ONPRC (MNS and TH) utilized this simulator with training under the guidance of a board-certified neonatologist (SNC) prior to performing the procedure in live animals. A GE Voluson 730 ultrasound unit with a 5-9MHz sector probe was used for all simulated and live sampling procedures. The ultrasound probe was placed on the exterior of the apparatus and learners obtained a long segment view of the tofu “placenta” and underlying fluid filled “amniotic cavity”. After visualizing an optimal sampling location, they introduced an 18 or 20 gauge 3.5cm spinal needle into the “placenta” in the plane of the ultrasound probe, maintaining visualization of the needle tip throughout insertion. Once the needle was observed within the block of tofu, the stylet was removed and a media-filled syringe was attached to the needle. Learners then performed gentle movement of the syringe in and out 5 to 10 times while applying negative pressure to the syringe. The syringe and needle unit was removed from the “placenta” and expelled the extracted tofu “villi” into a dish. This task trainer allowed for skill acquisition and optimization at numerous steps within this challenging procedure, including visualization and manipulation of a needle under ultrasound guidance, as well as determination of how aspiration pressure and needle passage impact sample yield [

20,

21].

As a technical note, the use of a specifically designed aspiration syringe handle (Anthony Products Inc. Item No. WJ-20-0020 20cc) may increase operator comfort and generate more powerful suction to aid in dislodging fragments of placental tissue as they are drawn through the needle and into the media filled syringe.

2.2. Animals

All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the ONPRC, and all procedures contributing to this work complied with the ethical standards of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Animal Welfare Act and Regulations enforced by the United States Department of Agriculture. Female rhesus macaques (n=3) used in this study were all healthy, normal weight, and fed a standard chow diet (Purina Lab Diet 5000). Animals were assigned to the Time-Mated Breeding program at the ONPRC and had a proven reproductive history with prior live birth offspring. All early pregnancies were identified through daily monitoring of estrogen and progesterone levels and confirmed by ultrasound. Based on extensive hormonal assessment studies conducted at the ONPRC [

22,

23], gestational age is calculated by considering the first day of conception as two days after the estrogen peak for consistent and reproducible dating.

2.3. Chorionic Villus Sampling

On the day of the procedure, following an overnight fast, animals were sedated with ketamine (10mg/kg IM), followed by endotracheal intubation and anesthesia maintenance on 1-2% inhaled isoflurane gas mixed with 100% oxygen. Hair was clipped from the abdomen, and the area was sterilely prepped and draped for CVS. A transabdominal ultrasound-guided approach was used for direct insertion of an 18- or 20-gauge 3.5cm spinal needle into the anterior placental disc. The longest axis of the placenta was targeted for needle advancement. Once the needle was inserted through the uterine wall and the needle tip was positioned within the placenta, the stylet was removed, and the needle was advanced through the placental disc. This created a ‘core’ biopsy collected in the empty bore of the needle. A 5ml syringe containing warmed, heparinized saline (5 units/ml) was then attached to the end of the needle, and the needle was moved back and forth within the placental disc 4 to 6 times while applying suction via the attached syringe. Altering the angle of the needle slightly with each advancement maximized the collection of aspirated villous tissue.

Biopsy samples were transported to the laboratory to obtain a wet weight prior to processing as follows: 1) flash frozen in liquid N2 for storage at -80oC, 2) fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours prior to transfer to 70% ethanol for paraffin embedding, or 3) washed in buffer for organoid isolation (described below).

2.4. Histology

Histological sections were cut from paraffin embedded blocks at a thickness of 5µm. Slides were heated to 60oC for 1 hour prior to being dewaxed in xylenes followed by ethanol gradient washes to rehydrate the tissue. After rehydration, the slides were stained using hematoxylin (Epredia, 72804) for 1-minute, bluing buffer (Fisher Healthcare, 220-106) for 1 minute, and eosin (Fisher Healthcare, 220-104) for 30 seconds. The slides were immediately cover slipped and allowed to dry before digital imaging and review.

2.5. RNA Isolation

CVS biopsy samples were stored at –80 °C until RNA isolations were performed via phenol/chloroform separation using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, 15596026). Immediately after thawing, 250µl of lysis buffer (50mM Tris pH 8.0, 100mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS) was added and tissue was homogenized [

24] before transferring to a clean tube. A series of 10-minute incubations followed additions of 500µL TRIzol, 250µL TRIzol, and 200 µl of chloroform at room temperature with sample inversion. Samples were then spun at 4 °C at 21,300 x g for 5 minutes, the aqueous layer drawn off and transferred into 500µl of isopropanol with 1µl of linear acrylamide carrier (AM9520) and incubated. Samples were spun at 4 °C at 21,300 x g for 10 minutes and subsequently washed twice in 350µl 80% ethanol, spinning at 21,300 x g at 4 °C for 5 minutes. Excess ethanol was removed, and the pellets were dried before eluting in 40µl of nuclease-free water (ThermoFisher Scientific, J71786.AP).

RNA concentrations and purity were measured via Nanodrop instrument. If 260/280 ratios were not satisfactory (<1.8), the samples were cleaned as follows: nuclease-free water was added as needed to bring volumes to 100µl. 50µl of 7.5M NH4Ac and 200µl of isopropanol were added to each sample to precipitate RNA and were incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature. Samples were spun at 21,300 x g for 10 minutes, and supernatant was drawn off, followed by one wash with 80% ethanol. Supernatant was removed, and the pellet was air-dried for 10 minutes at room temperature. Pellets were dissolved in 40µl of nuclease-free water and a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer was used to confirm purity.

2.6. Organoid Isolation

The isolation method described in brief here was scaled down from the full published protocol for rhesus macaque trophoblast organoids generated from whole placenta following first trimester delivery [

25]. Organoid isolation was performed using serial CVS tissue samples from one animal at three gestational ages (G49, G72, and G106). Immediately following CVS, tissue was placed in pre-warmed wash buffer for <1 hour. Homogenate was digested in 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA for 5 minutes at 37

oC with shaking before being strained and quenched with digest stop buffer. Undigested material in the strainer was transferred into collagenase V solution (1mg/ml) and digested for an additional 5 minutes for maximum yield. All digest homogenates were quenched with digest stop buffer before being centrifuged at 600xg for 6 minutes to pellet cells. Cell pellet was washed once in DMEM/F12. Cells were then centrifuged, and debris removed, with 3 washes in DMEM/F12. Cells were suspended in Cultrex reduced growth factor basement membrane extract, type R1 (R&D Systems, 3433-005-R1) and 25µl droplets were seeded into a 48-well plate. The Cultrex domes were given 15 minutes to polymerize at 37

oC before being overlaid with 250µl of fresh organoid media.

3. Results

3.1. Text

The use of a simulation model prior to hands-on work in animals provides an opportunity to develop the necessary skills for performing the procedure and reduces the risk of adverse outcomes. Following simulation training, CVS was performed at three timepoints across gestation (ranging from G40 to G106) in each of three rhesus macaques. Tissue yields are reported in

Table 1 and varied based on gestational age, operator experience, and placenta position. Depending on biopsy size, the samples were used for several purposes intended to provide quality control measures and assess suitability for in vitro analysis.

The technique of obtaining biopsies via needle aspiration increases the risk of shearing the tissue under suction pressure and the needle bore imposes tissue sampling size constraints. Representative tissue sections from placentas collected following c-section delivery at G41 and G100 respectively (

Figure 2A and B) provide comparison samples for histological assessment. Appropriately, we demonstrate more immature villi in the early placenta (

Figure 2 A and C) and no evidence of loss of tissue integrity in any of the CVS-obtained samples (

Figure 2 C – E). Note the increased presence of red blood cells (RBCs) and evidence of clots in some of the CVS-obtained samples. Technical note: An RBC lysis treatment can be added as an additional incubation between the transfer of biopsies from heparinized saline and fixative for histology or wash buffer for organoid isolation. For RBC lysis, tissue is incubated in buffer prepared in sterile water (10X RBC Lysis Buffer #00-4300-54, Invitrogen eBioscience) for 5 minutes with physical disruption every minute in light-protected conditions.

3.2. Text

RNA quality and yields for one biopsy sample per each of the three animals are reported in

Table 2. A clean up step was required for each sample to improve purity and obtain a 260:280 ratio in the acceptable quality range. This led to a loss of RNA yield shown in the pre- versus post- RNA clean-up concentration values (

Table 2). In the sample from animal C the final yield was small but still usable for cDNA conversion.

3.3. Text

Placenta samples from animal C were used for trophoblast organoid isolation at each CVS timepoint, G49, G72, and G106 (

Figure 3 panels A – C). We were successful in isolating organoids at G49 that could be passaged to expand them in culture conditions. At the two later timepoints, organoid isolation was achieved but they remained sparse and failed to propagate well despite an extended time in culture.

4. Discussion

The use of ultrasound-guided needle procedures to collect villus biopsies has tremendous potential to facilitate longitudinal studies in continuing pregnancies. It could reduce the overall number of animals needed for pregnancy studies and expand the information obtained from each animal. This provides new opportunities for mechanistic studies in our NHP models of placental perturbation such as chronic maternal high fat diet [

11,

26] or Zika virus infection [

6]. Moreover, the use of CVS techniques enables correlation of placental function in pregnancies that end in natural delivery (where placental collection is not feasible) with longer-term offspring health outcomes. In some instances, this sampling capability may negate the need for surgical deliveries where maternal infant repairing and extensive primate wellbeing behavioral specialist efforts are needed for mother rearing success.

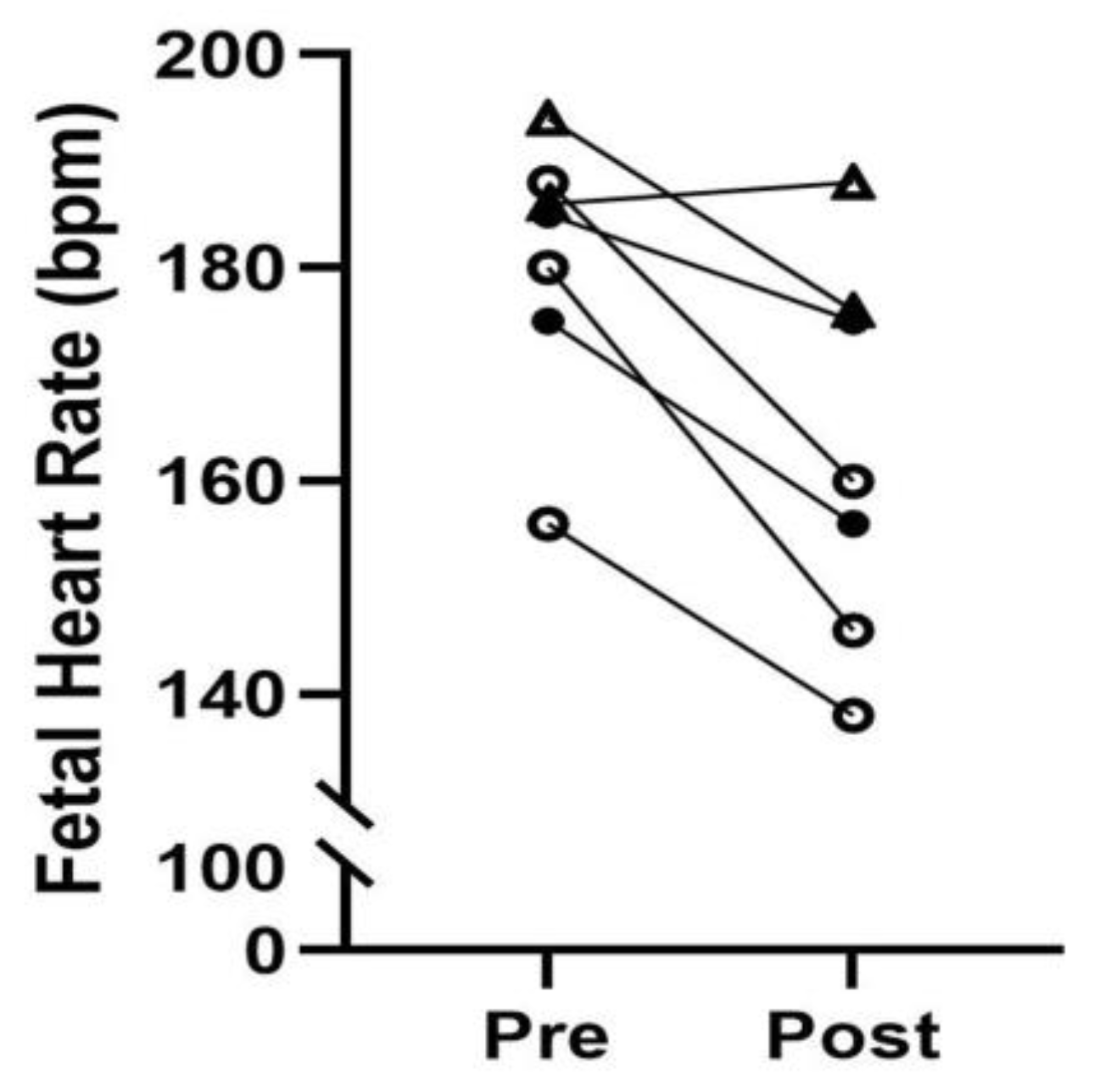

The tissue yields were small in our early CVS attempts which does limit the downstream sample use. However, yields improved with experience gained and have been greater than 200mg in animals who underwent CVS since this initial training pilot was conducted. Most importantly, we have observed no adverse outcomes such as preterm delivery in animals subjected to serial CVS procedures (maximum of three with a minimum recovery period of two weeks between events). In addition, fetal heart rate was monitored at the start and completion of each CVS procedure with data available for 7 of the 9 pilot studies (

Figure 4). We demonstrate a modest decrease in fetal heart rate with maternal sedation by inhaled isoflurane for the 10–20-minute procedure, but values remained within normal range for all animals [

27]. One subjective ultrasound observation made at the third CVS timepoint was the presence of multifocal hyperechoic foci within the placenta, which is a typical appearance of mature, near-term placentas due to calcifications that form within the tissue. Early calcification can also be indicative of vascular disruption [

28]. Understandably some evidence of injury would be anticipated after the introduction and passing of a needle through the tissue. Importantly, the placenta has adaptive capabilities which allow it to tolerate a certain degree of insult and still have the ability to repair itself and maintain the pregnancy [

29]. This natural occurrence of placental plasticity lends itself to the use of CVS and the expansion of longitudinal studies with minimal detrimental impact to pregnancy outcomes in the NHP.

The histological samples were an important indicator of biopsy use as one concern for in vitro placental structural analysis would be the possible shredding of tissue and loss of appropriate villous architecture. Our histology review demonstrates normal morphology of the tissue with one notable difference being increased blood contamination visible surrounding the villous tissue in some samples. Two protocol modifications that we introduced during the pilot were to add heparin into the saline in the collection syringe and to perform an RBC lysis step if warranted following gross visual inspection of the tissue at the time of weighing. A subjective observation indicated that the use of lysis buffer improved the quality of the tissue by reducing RBC contamination. Although this was not quantified, the lysis buffer did not appear to damage the tissue.

From the CVS biopsies, we were able to generate good quality RNA in quantities sufficient to allow gene expression studies. Another alternative, not trialed here, would be to isolate protein which seems feasible with any sample that exceeds ~50mg as the amount of starting material for a protein extraction protocol.

One rationale for the use of CVS, specific to the research needs of our team, was to test the ability to isolate placental trophoblast organoids from the biopsy samples. The first trimester is the period of pregnancy in which the highest proportion of cytotrophoblast cells, the stem cell of the placenta, are pluripotent and have the potential to differentiate into different phenotypes [

30]. Until now, development of NHP trophoblast organoids has required first trimester termination of pregnancy and a cesarean section surgery to allow collection of the whole placenta [

25]. In this pilot study, we were able to achieve organoid isolation from CVS-obtained biopsies. However, we observed slower growth and overall poor propagation in the later timepoints. It is possible this was due to a technical error, specifically the initial plating density may have been too sparse, which hindered the growth in our regular culture conditions; this can be investigated in future CVS culture attempts with further protocol refinement. Nonetheless, despite the less favorable outcome in the later CVS samples, the G49 biopsy resulted in successful organoid generation, which is important as the first trimester is the timeframe of greatest interest for our in vitro investigations. A second potential difficulty is that CVS-derived organoid cultures are susceptible to maternal gland contamination due to the introduction of the needle through the maternal uterine layers which results in a less pure trophoblast cell population in the biopsy sample. This presents a challenge for the further development of CVS-generated trophoblast organoids. Maintenance of the stylet within the spinal needle during penetration of maternal tissues with removal after the placenta has been penetrated reduces contamination of the placental sample. However, additional troubleshooting within the sampling technique and the possible addition of steps within the isolation protocol to purify the preparations are needed to minimize contamination.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, here we have provided training guidance to practice performing CVS procedures with demonstrated success in obtaining good quality placenta biopsies from pregnant NHPs. We suggest that the use of minimally invasive CVS in the research setting has the potential to enhance longitudinal studies and reduce the number of animals needed to conduct pregnancy investigations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C., M.S. and V.R.; Methodology, S.C., M.S., T.H. and V.R.; Investigation, S.C., M.S., T.H., J.C., B.W., H.H. and V.R.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, S.C., M.S., J.C. and V.R.; Writing – Reviewing & Editing, T.H., B.W. and H.H.; Visualization, J.C. and V.R; Funding Acquisition, M.S. and V.R.

Funding

This publication was made possible with Pilot Program support from program development funds from the Oregon National Primate Research Center and infrastructure and operations support through the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Office of the Director, P51-OD-011092.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All research reported in this manuscript complied with the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Oregon National Primate Research Center, Oregon Health and Science University [Protocol # IP00004029: Approved: 11/11/2024]. All research reported in this manuscript adhered to the legal requirements of the country in which the work took place. The research adhered to the American Society of Primatologists (ASP) Principles for the Ethical Treatment of Non-Human Primates.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Joshua Nitsche for the development of the CVS simulator model and clinical training provided to Dr. Sarah Cilvik, which was subsequently provided to the ONPRC surgical veterinarians. We also acknowledge the staff within the Division of Comparative Medicine, and the Surgical Services Unit at the ONPRC for their support of the animal studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CVS |

Chorionic Villus Sampling |

| NHP |

Non-human Primate |

| NAMs |

New Approach Methods |

| IACUC |

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| G |

Gestational Day |

References

- D. Kidron, J. Bernheim, and R. Aviram, “Placental findings contributing to fetal death, a study of 120 stillbirths between 23 and 40 weeks gestation,” Placenta, vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 700–704, Aug. 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Roberts and M. D. Post, “The placenta in pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction,” J. Clin. Pathol., vol. 61, no. 12, pp. 1254–1260, Dec. 2008. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Salafia, A. M. Vintzileos, L. Silberman, K. F. Bantham, and C. A. Vogel, “Placental pathology of idiopathic intrauterine growth retardation at term,” Am. J. Perinatol., vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 179–184, May 1992. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Salafia, C. A. Vogel, K. F. Bantham, A. M. Vintzileos, J. Pezzullo, and L. Silberman, “Preterm delivery: correlations of fetal growth and placental pathology,” Am. J. Perinatol., vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 190–193, May 1992. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Ramsey, M. L. Houston, and J. W. Harris, “Interactions of the trophoblast and maternal tissues in three closely related primate species,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 124, no. 6, pp. 647–652, Mar. 1976. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Hirsch et al., “Zika virus infection in pregnant rhesus macaques causes placental dysfunction and immunopathology,” Nat. Commun., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 263, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. O. Lo et al., “Effects of early daily alcohol exposure on placental function and fetal growth in a rhesus macaque model,” Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 226, no. 1, p. 130.e1-130.e11, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. O. Lo et al., “Impaired placental hemodynamics and function in a non-human primate model of gestational protein restriction,” Sci. Rep., vol. 13, no. 1, p. 841, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Melbourne, M. C. Schabel, A. L. David, and V. H. J. Roberts, “Magnetic resonance imaging of placental intralobule structure and function in a preclinical nonhuman primate model†,” Biol. Reprod., vol. 110, no. 6, pp. 1065–1076, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. H. J. Roberts et al., “Adverse Placental Perfusion and Pregnancy Outcomes in a New Nonhuman Primate Model of Gestational Protein Restriction,” Reprod. Sci. Thousand Oaks Calif, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 110–119, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Salati et al., “Maternal high-fat diet reversal improves placental hemodynamics in a nonhuman primate model of diet-induced obesity,” Int. J. Obes. 2005, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 906–916, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Alfirevic, K. Navaratnam, and F. Mujezinovic, “Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis - Alfirevic, Z - 2017 | Cochrane Library,” 2017, Accessed: Oct. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003252.pub2/full.

- “Amniocentesis and Chorionic Villus Sampling,” ResearchGate. Accessed: Oct. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/14962257_Amniocentesis_and_Chorionic_Villus_Sampling.

- N. S. Silverman and R. J. Wapner, “Chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis,” Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 258–264, Apr. 1990.

- J. F. Nitsche, S. Conrad, S. Hoopes, M. Carrel, K. Bebeau, and B. C. Brost, “Continued Validation of Ultrasound Guidance Targeting Tasks: Relationship with Procedure Performance,” Acad. Radiol., vol. 28, no. 10, pp. 1433–1442, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Akolekar, J. Beta, G. Picciarelli, C. Ogilvie, and F. D’Antonio, “Procedure-related risk of miscarriage following amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 16–26, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Silver, S. N. MacGregor, L. H. Muhlbach, M. P. Kambich, and A. Ragin, “A comparison of pregnancy loss between transcervical and transabdominal chorionic villus sampling,” Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 83, no. 5 Pt 1, pp. 657–660, May 1994.

- L. M. Demers, G. J. Macdonald, A. T. Hertig, N. W. King, and J. J. Mackey, “The cervix uteri in Macaca mulatta, Macaca arctoides, and Macaca fascicularis--a comparative anatomic study with special reference to Macaca arctoides as a unique model for endometrial study,” Fertil. Steril., vol. 23, no. 8, pp. 529–534, Aug. 1972. [CrossRef]

- J. Maines and F. J. Montero, “Chorionic Villus Sampling,” in StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. Accessed: Oct. 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563301/.

- J. F. Nitsche, S. Conrad, S. Hoopes, M. Carrel, K. Bebeau, and B. C. Brost, “Continued Validation of Ultrasound Guidance Targeting Tasks: Assessment of Internal Structure,” Acad. Radiol., vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 559–565, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Nitsche and B. C. Brost, “The use of simulation in maternal-fetal medicine procedure training,” Semin. Perinatol., vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 189–198, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Wolf et al., “In vitro fertilization and embryo transfer in the rhesus monkey,” Biol. Reprod., vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 335–346, Aug. 1989. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Wolf, S. Thormahlen, C. Ramsey, R. R. Yeoman, J. Fanton, and S. Mitalipov, “Use of assisted reproductive technologies in the propagation of rhesus macaque offspring,” Biol. Reprod., vol. 71, no. 2, pp. 486–493, Aug. 2004. [CrossRef]

- E. de Waal et al., “In Vitro Culture Increases the Frequency of Stochastic Epigenetic Errors at Imprinted Genes in Placental Tissues from Mouse Concepti Produced Through Assisted Reproductive Technologies”.

- B. M. Wessel et al., “Development of a Trophoblast Organoid Resource in a Translational Primate Model,” Organoids, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 24–45, 2025.

- A. E. Frias et al., “Maternal high-fat diet disturbs uteroplacental hemodynamics and increases the frequency of stillbirth in a nonhuman primate model of excess nutrition,” Endocrinology, vol. 152, no. 6, pp. 2456–2464, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. G. Hartman, R. R. Squier, and O. L. Tinklepaugh, “The Fetal Heart Rate in the Monkey (Macacus Rhesus).,” Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med., vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 285–288, Dec. 1930. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Wallingford, C. Benson, N. W. Chavkin, M. T. Chin, and M. G. Frasch, “Placental Vascular Calcification and Cardiovascular Health: It Is Time to Determine How Much of Maternal and Offspring Health Is Written in Stone,” Front. Physiol., vol. 9, p. 1044, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. H. J. Roberts et al., “Restriction of placental vasculature in a non-human primate: a unique model to study placental plasticity,” Placenta, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 73–76, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Wessel, J. N. Castro, and V. H. J. Roberts, “Trophoblast Organoids: Capturing the Complexity of Early Placental Development In Vitro,” Organoids, vol. 3, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).