1. Introduction

First trimester chorionic villus sampling is increasingly used for the prenatal diagnosis of genetic diseases. Chorionic villus sampling (CVS) has shown to be an acceptably safe and effective technique for the early prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal aberrations [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Collaborative studies from the United States and Canada have shown that the sampling success rate for CVS compares favorably with that of amniocentesis (98.2 vs. 99.5%, respectively), while the fetal loss rate appears to be slightly higher for the former than later (0.8 and 0.6 % higher in US. and Canadian studies, respectively) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Spontaneous abortion rates for CVS have been reported in various centers and randomized trial have suggested they are very similar, between CVS and amniocentesis [

1,

2,

6,

8,

10,

14,

15,

21,

26,

28,

30,

31]. It can be difficult to attribute fetal loss directly to the CVS procedure because of the involvement of additional factors, such as maternal age and previous reproductive performance, but several variables have been shown to influence the risk of spontaneous abortion including procedure type of procedure, cannula used, the number of attempts, and the operator experience [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].Chorionic villus sampling is usually performed by the transcervical passage of a catheter or forceps, the transabdominal insertion of a spinal needle into the placenta under continues transabdominal ultrasound guidance, or transvaginal CVS in which endovaginal ultrasound guidance is used to obtain chorionic villi. Transabdominal CVS may have advantages that transcervical or transvaginal CVS, lack with the latter two involving vaginal manipulations, the passage of a cannula or needle contaminated with bacteria through the endocervix that is contaminated with bacteria and restricted maneuverability of the cannula within the uterine cavity. Transabdominal sampling allows for freer access to the placental site, has less potential for introducing infection and does not require any vaginal manipulation. To date over 500 000 of early CVS procedures have been performed globally, with a fetal loss rate ranging from 0. 2% to 7 % being recorded at individual canters [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The fetal loss rate is generally the lowest at more, particularly that have more than 1000 women admissions [

16,

17,

18,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

2. Material and Methods

Between January 2008 and May 2023, TC-CVS, TA-CVS and TV-CVS were performed in 5500 singleton pregnancies, by single operator (M.P.). Women aged at least 37 years old, at the expected date of delivery, women who had other indications for prenatal diagnosis, were counselled about the randomized study. To be eligible to participate, a woman had been al less than 14 weeks gestation with a viable singleton pregnancy and be able to attend a medical facility for four ultrasound scans, one at 10-14 weeks, the second at 16-20 weeks, the third at 28-32 weeks and the fourth after 36 weeks. The patients were also re-examined immediately if they experienced had bleeding, amniotic fluid leakage or abdominal discomfort. Patients who did not accept randomization were offered placental biopsy or amniocentesis. Exclusion criteria involved the detection of embryo death of at the first ultrasound, multiple pregnancy, or if they were RH-isoimmunized, or untreated cervical infection. The study protocol was approved by Ethics Committee of private hospital Podobnik and all the women enrolled provided verbal and written consent. At 18-22 weeks, all women had a second ultrasound scan (anomaly scan) to detect another fetal anomalies, and control ultrasound scans at 28-30 weeks and after 35 weeks.

To ascertain fetal losses, participants were asked to report all spontaneous and induced abortions to the hospital. All women remaining in the study were phoned telephoned at 20-24 weeks gestation to obtain information about complications or problems with their pregnancies. If a spontaneous abortion had occurred before 28 weeks of pregnancies, the appropriate forms for fetal losses were completed. Follow up occurred after 42 weeks to obtain information about the delivery. Only very basic information about the delivery, gestational age, and birth weight of the baby well as any abnormalities obvious at birth was requested of all 5500 participants. This prospective monocentric, randomized study comprises data from 5500 women allocated to transcervical CVS (TC-CVS) 850 patients, transabdominal CVS (TA-CVS) 4500 patients, and transvaginal CVS (TV-CVS) 150 patients, under single operator. We have assessed the efficacy of transabdominal CVS compared with transcervical CVS and transvaginal CVS, and examined the factors that have been implicated in causing spontaneous abortion. We compared the risk of miscarriage in pregnancies that involved CVS, which comprised study group, and those in pregnancies that did not involve an invasive procedure, the control group. The procedure related risk of pregnancy loss following any invasive procedure, was calculated as a risk a difference between of the two groups, with the main factor with control group pregnancy women, being almost the same, as that of the study group, but these women did not undergo any invasive perinatal procedures Data on pregnancy outcome and newborn infants were collected from delivering hospitals, which identified any complication during pregnancy and delivery, as well information about the newborn and placenta. Pediatrics report of intellectual disability, from five years of delivery, was requested of 4400 participants.

A total of 5500 patients, 850 (15.5%) patients underwent transcervical CVS, while150 (2.7%) underwent transvaginal CVS and 4500 (81.8%) transabdominal CVS. Between January 2008 and December 2012 TC-CVS was carried out in 500 (58. 8%) pregnancies, transvaginal CVS was performed 150 (100%) pregnancies, and the transabdominal CVS technique was used in 850 (18.9%) cases. From December 2012 transabdominal CVS become the preferred CVS method. Maternal age, parity, indication for prenatal diagnosis and gestational week of sampling were same in the three groups and the control group comprised pregnancies that did not involve an invasive procedure. At the beginning of the study, we performed TCT-CVS only. However, we performed TV-CVS when transcervical CVS or transabdominal CVS not technically possible, as results of a posteriorly implanted placenta within a retroverted, retroflexed uterus. In order to evaluate the differences in risk between the three methods we chose to compare early complications (bleedings, infections, early spontaneous abortions, elective abortions, abnormal cytogenetic results and total fetal loss (before 28 weeks).

Transcervical chorionic villus sampling (TC-CVS) was performed with the patient in the lithotomy position. Aspirations were performed at 10 to 13,6 weeks of gestation age. To perform the aspiration, we used a 26 cm long Portex catheter or a 24 cm long Holzgreve-Angiomed catheter, with continuous real-time ultrasonographic guidance provided using a Voluson 8 or 10 scanner, with a 5-9 MHz transducer. The catheter was inserted through the cervix into the chorion frondosum, rotating the catheter to aspirate the tissue into a 20 ml plastic syringe containing 5 ml culture medium. Amounts of 1 to 25 mg of chorion frondosum tissues were obtained and the modified short term-culture (overnight), with modification, was used in all cases for caryotipization [

19,

20,

21,

22,

24,

25,

26,

27,

29,

33,

34,

35,

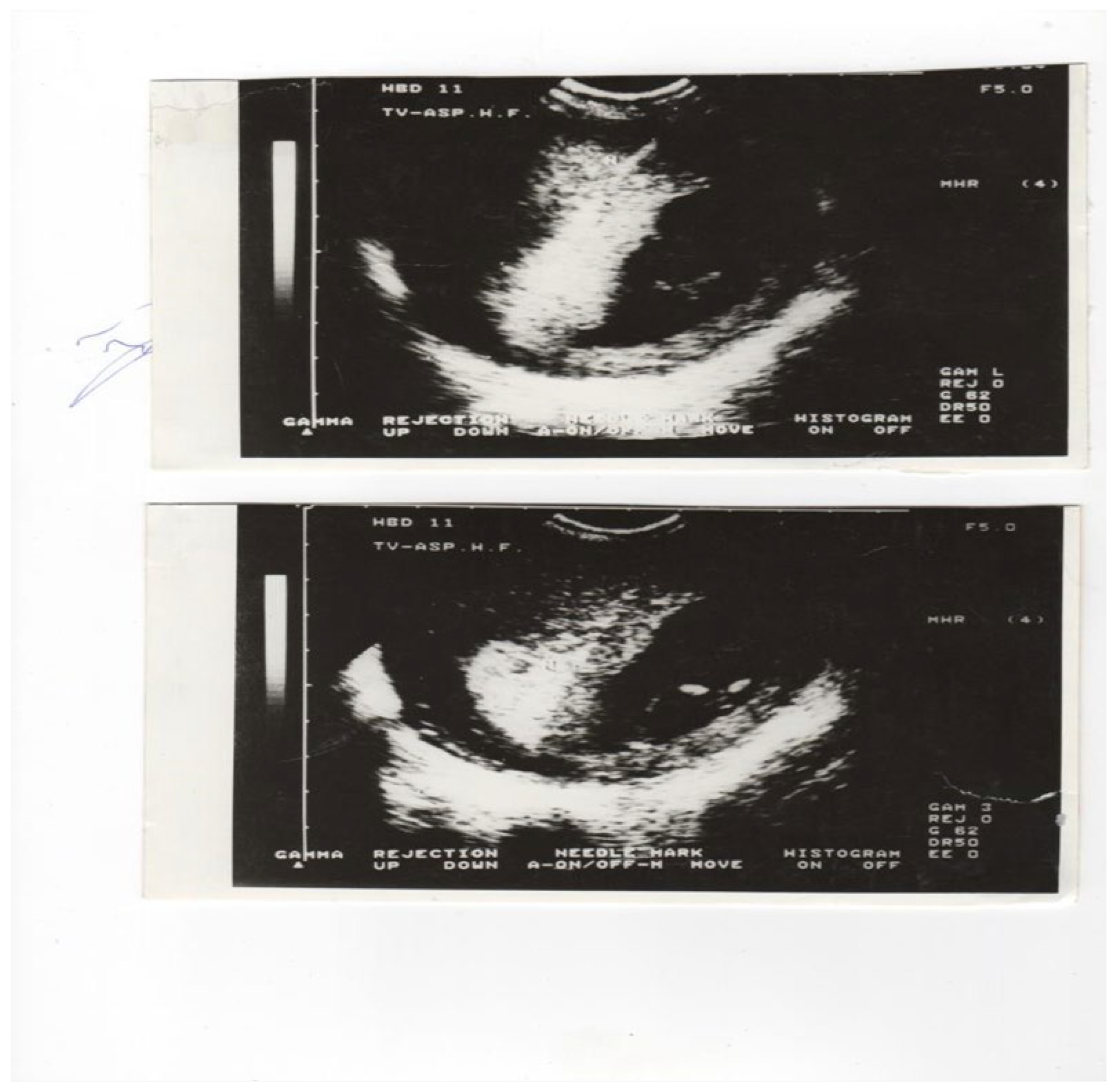

36]. On the other hand, transabdominal chorionic villus sampling (TA-CVS) was performed with the patient in the supine position, useding single a 20 gauge-90 mm spinal needle. Upon disinfecting the anterior abdominal wall and the patients Havin an empty urinary bladder, the needle was inserted under ultrasound guidance, into the middle of the chorion frondosum, where the angle of insertion was slowly and the angle was changed by 20 to 40 degrees in the presence of negative pressure chorion frondosum tissue was aspirated into a 20 ml syringe, containing the medium previously specified. Further transvaginal chorionic villus sampling (TV-CVS) was performed with the patient in the lithotomy position. To perform aspiration, we used a 35 cm long 20-gauge needle with continuous real-time ultrasonic guidance provided with a 5-9 MHz vaginal transducer with a guide needle. The needle was inserted through the fornix (anterior or posterior) into chorion frondosum (

Figure 1 a and

Figure 1 b) and the tissue was aspirated into a 20 ml syringe, by combining repeated strong suction and slow backward and forward movement of the needle tip. After two failed passes, for all three techniques, the women were offered another CVS session a week later. All 5500 early CVS sampling was performed by a single operator: M.P.

Cytogenetic findings [

1,

2,

3,

4,

6,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

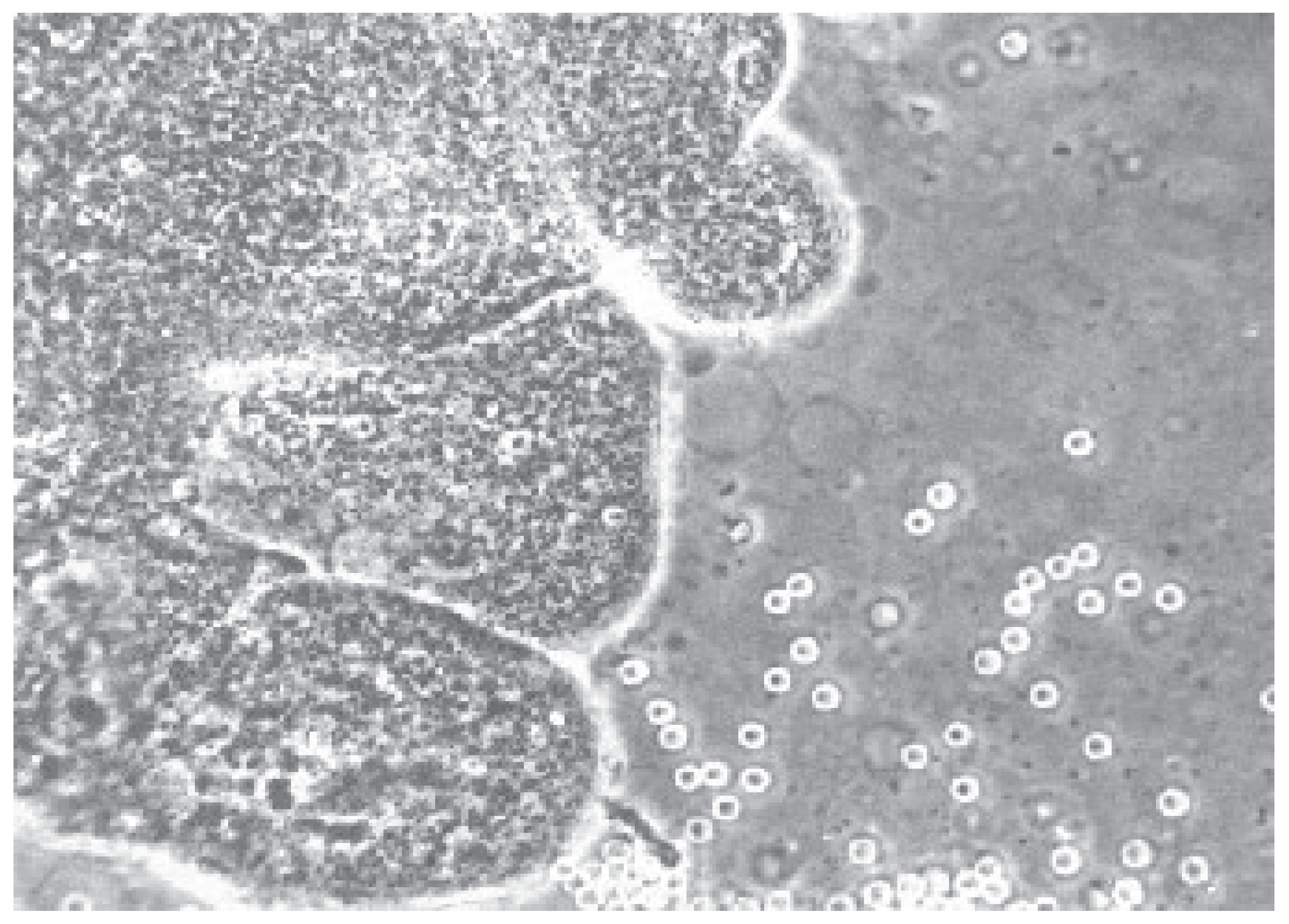

26] indicated that the sample of villus tissue was immediately transferred a laboratory and examined under a dissecting microscope (

Figure 2.). An overnight short-term incubation method for three days or a culture method for seven days was used. Additionally, fetal heart rate (FHR) was monitored by M-mode in all patients. Fetal heart rates (FHR) were determined for each patient before and after CVS using the M-mode. In 200 patient’s alpha-feto-protein (AFP) levels were determined ten minutes before and ten minutes after CVS, to evaluate any feto-maternal hemorrhage.

Transvaginal color Doppler was used to investigate the uteroplacental and fetal vessels velocity waveforms in 400 pregnancies before and after CVS (300 TA-CVS and 100 TC-CVS). Doppler recordings of the uterine artery, spiral artery, umbilical artery and middle cerebral artery were performed ten minutes prior and ten minutes after to TA-CVS and TC-CVS. The study was performed using a Voluson 8 - 10 GE machine with a 5-9 MHz transvaginal probe. The velocity wave forms were then recorded and the pulsatility index (PI) was calculated automatically [

4,

6,

7,

10,

12,

16,

24,

25,

26,

27,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. All rhesus negative women were administered obtained 50 ug of anti-D administrated after CVS.

In person follow up was planned with each patient. Information’s about successful deliveries and neonatological findings have been obtained directly from the relevant hospitals or patients and all data have been computerized and may be accessed promptly via the relevant index or the information displayed herein. Pediatrics report of intellectual disability, from five years of delivery, was requested of 4400 participants.

The Chi-square and Student-t-test were performed to evaluate statistical significance where applicable, and a p-value of <0,05(two tailed) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The main indication for CVS was increased maternal age (37years or more), which was found in 65% of patients. The indications are shown in

Table 1. Villus recovery by transcervical, transabdominal and transvaginal chorion villus sampling is shown in

Table 2. In total 850 (15.5%) patients underwent TC-CVS and spontaneous abortion rate followed in 5 cases (0.6%) (low 28 weeks). Further in 4500 (81.8%) patients who underwent TA-CVS, spontaneous abortion followed in 8 (0.18 %) women. Of 150 (2.7%) patients receiving the number of spontaneous abortion rate after TV-CVS was in 2 cases (1.3 %). The spontaneous abortion rate was lower in cases involving with TA-CVS and TC-CVS than TV-CVS (P<0,05). We compared these results with those of the 4777 pregnancies with indications for TA CVS, but these women did not undergo invasive procedures, and miscarriage in this elective group, before 28 weeks of pregnancy, occurred in twenty pregnancies, (0.40%), this rate was higher than in the study group for TA-CVS (0.18%) (P < 0,05). We assessed miscarriage in the control group for TC CVS with 875 elective pregnancies and found that miscarriage occurred in 10(1.1%) pregnancies while in the TV-CVS groups of 165 elective pregnancies, miscarriage occurred in 5 pregnancies (3.5%)(P< 0,05).

Chorionic villus sampling was performed in 25% of cases at 10 to 11 weeks of gestation (10-16 mm crown-rump length), in 25% of cases at 11 to 12 weeks of gestation (17-26 mm crown-rump length) and in 50% of cases at 12 to 13,6 weeks of gestation (27-80 mm crown-rump length). In 96.6% of all cases only one sampling attempt was necessary, in 3.4% of all cases, a sufficient sample was obtained on the second attempt. We not found relationship between the success rate at the first insertion and the gestation age. An adequate sample tissue weight was significantly higher in cases with TC-CVS and TV-CVS than TA-CVS (

Table 3). The amount of material obtained was always sufficient for diagnosis. We also detected bleeding in 34 (4.9%) patients between sampling and delivery (

Table 2.). The placental hematoma measuring 0,5 to 1 ml was seen at the sampling site in 8 (1.4%) patients. Bleeding was more common following TC-CVS than TA-CVS or TV-CVS, while peritoneal reaction developed only after TA-CVS. We have found infection in three (0.4%) cases after TC-CVS, in two (0.3%) after TV-CVS and in one (0,02%) after TA-CVS, (P<0,05). There were two (25,0%) abortions two weeks later in the group with infection.

Cytogenetic results were obtained in 5480 of 5500 CVS (99.6%) cases. In ten (0.2%) case’s tissue was unsuitable for study. However, we find abnormal cytogenetic results in 220 (4%) cases. In five of fourteen cases (35.7%) involving spontaneous abortion after CVS abnormal cytogenetic findings were detected. Therefore, copy number variants (CNVs) analysis can be recommended for patients in whom one or major structural abnormality identified by ultrasonographic examination. In our study we detected structural malformation and we preformed (CNVs) in 35 fetuses [

6,

13,

14,

15,

16,

28,

29,

33,

36]. In 5 (20,0%) fetuses of this group of patients we found pathological CNVs. Moreover in our study the pathologic copy number variants found including the following:22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome, 22q1q1.2 duplication (two hydrops fetalis), other were 10q26-12q26.3.12q21q 22 deletion (advanced maternal age 45 years), 5q21.1q34deletion (cardiac anomaly) and then 46XX,del(X)(p11.3p22.3) (hygroma colli, hydrothorax, omphalocele, hydrops fetalis).

The total post-procedure fetal loss rate (spontaneous abortion rate and termination of pregnancy) was in 236 (4.5 %) cases: 66 (7.7%) cases after TC-CVS, in 162 (3.4%) after TA-CVS and in 8 (5,3%) after TV-CVS. The number of perinatal deaths was zero. In this group the total fetal loss rate was higher in the group after TC-CVS and TV-CVS than after TA-CVS (P < 0.05).

Our results show that post-CVS spontaneous abortion rate progressively declines with advancing gestation rate at sampling. In fact, the spontaneous abortion rate before 11 weeks was 0.6 %, before 12 weeks it was 0.4 %, before 13 weeks 0.2 % and before 14 weeks 0,16% and was significantly lower before 14 weeks of gestation (P< 0.05). In younger patients (less than 30 years old) the spontaneous abortion rate remained low at from 1.4 % (3 cases) in women under 30 years to 4.7% (11 cases) in women of 40 years or older. In older patients the total fetal loss rate was significantly higher when sample was before 11 weeks of gestation. When CVS was performed after 13 weeks of gestation the total fetal loss rate decreased from 4.5 % to 0.15 % (P < 0.05).

Serum alpha-fetoprotein levels (AFP) changed in 25 (12.5%) of 200 patients in whom serum samples were obtained before and after CVS, but we found no correlation between AFP elevation, the amount of villi aspiration and spontaneous abortion rate after CVS. There was no significant difference detected in fetal heart rate (FHR) before and after CVS.

Transvaginal color Doppler was used to investigate the uteroplacental and fetal vessels in 400 pregnancies (300 TA-CVS and 100 TC-CVS) before and after CVS The main uterine artery, the spiral arteries (near the sample location for CVS), the umbilical arteries and the middle cerebral artery were examined. demonstrated. There was no significant difference in the mean pulsatility indices (PIs) between maternal and fetal circulation, before and after CVS, in the group with TA-CVS and TC-CVS.

Follow-up was possible in all cases. Further we have detected fetal anomalies in 55 cases (1%): central nervous system in six, facial clefting in one, cardiac anomaly in ten, hygroma coli multilocularae in eleven, abdominal wall defect in five, genito-urinary in nine, universal hydrops in six (

Table 5). However, we have never seen any serious limb abnormalities. Pediatrics report of intellectual disability, from five years of delivery, was requested of 4400 participants. We not found any intellectual disability.

Table 4.

PULSATILITY INDEX (PI) VALUES IN THE MAIN UTERINE ARTERY, THE SPIRAL ARTERIES, THE INTRAPLACENTAL ARTERIES, THE UMBILICAL ARTERY ANF THE MIDDLE CEREBRAL ARTERY BEFORE AND AFTER CVS.

Table 4.

PULSATILITY INDEX (PI) VALUES IN THE MAIN UTERINE ARTERY, THE SPIRAL ARTERIES, THE INTRAPLACENTAL ARTERIES, THE UMBILICAL ARTERY ANF THE MIDDLE CEREBRAL ARTERY BEFORE AND AFTER CVS.

| N=400 |

PI 10 MIN |

PI 10 MIN |

| |

BEFORE CVS |

AFTER CVS |

| |

Mean |

1SD |

Mean |

1 SD |

| UTERINE ARTERY |

2,10 |

0,55 |

2,07 |

0,58 |

| SPIRAL ARTERY |

0,60 |

0,55 |

0,59 |

0,18 |

INTRAPLACENT.

ARTERY

|

0.48 |

0.15 |

0.50 |

0.16

P>0.01

|

UMBILICAL ARTERY

|

2.96 |

1.42 |

2.86 |

1.55

P>0.01

|

MIDDLE CEREBRAL

ARTERY

|

1.88 |

0.55 |

1,75 |

0,60

P>0,01

|

Table 5.

MALFORMATION DETECTED IN UTERO OR AT BIRTH IN 5500 CASES AFTER CVS.

Table 5.

MALFORMATION DETECTED IN UTERO OR AT BIRTH IN 5500 CASES AFTER CVS.

FETAL MALFORMATION

N |

AMOUNT OF CHORIONIC TISSUE(MG) |

ANENCEPHALY

2

|

20 |

HYDROCEPHALUS

2

|

25 |

SPINA BIFIDA

2

|

30 |

CLEFT-LIP PALATE

1

|

20 |

CARDIAC ANOMALY

10

|

30 |

OESOPHAGAL ATRESIA

1

|

25 |

DIAFRAGMATIC HERNIA

2

|

20 |

HYGROMA COLLI MULTILOCULARAE

11

|

30 |

OMPHALOCOELE

5

|

25 |

RENAL AGENESIS

3

|

15 |

CYSTIC KIDNEYS

6

|

20 |

HYDROPS UNIVERSALIS

6

|

25 |

TANATOTROFYC DYSPLASIA

1

|

15 |

POLYDACTILIA

3

|

20 |

LIMB REDUCTION

0

|

20 |

TOTAL

55(1%)

|

20,3 +-9,7 mg |

4. Discussion

CVS is helpful for women at increased genetic risk when performed at 10-14 weeks of gestation. When CVS is practiced by an expert it has an acceptably low complications rate. There have been five reports comparing CVS and amniocentesis in women in whom a viable pregnancy has been demonstrated by ultrasound in the first trimester. When comparing the risk of amniocentesis with the risk of CVS, the difference may be 1-2 per cent or even more after CVS [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Crane et al. 1988. [

11] published a small series of reports that showed no difference in loss rates between two procedures. Transabdominal biopsy (TA-CVS) and transcervical catheter aspirations (TC-CVS) are currently the main techniques used. currently. A retrospective Cochrane cohort study published in 2017 reported outcome following 4862 CVS procedures, 2833 of which were transcervical (1787 using forceps and 1046 using cannulas). The procedure-related pregnancy loss rate was 1,4% for transcervical CVS and 1.0 for transabdominal CVS. However, the risk of pregnancy loss after transcervical CVS was only 0.27 when forceps were used and 3,12 % for those performed with cannula, suggesting that forceps may offer, a safety advantage [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

The procedure-related pregnancy loss, stratified fetal loss by operator experience, according to the number of procedures experienced for invasive prenatal diagnosis, at approximately 1000 invasive prenatal procedures per year [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. We compared our miscarriage rate with the control group pregnancies but these women did not undergo have an invasive procedure, while miscarriage in this elective group occurred, in twenty pregnancies 0.4% (same like study group for TA-CVS). Brambati et al. recorded [

37] fetal loss through 28 weeks’ gestation in the pregnancies intended to continue, reaching 2.58%, with the rate increasing with maternal age. We compared miscarriages in control group for TC CVS with 875 elective pregnancies in which miscarriage occurred were in ten (1.1%) pregnancies and in TV CVS groups of 165 elective pregnancies, miscarriage occurred in 5 (3.5%) pregnancies The miscarriage rate was lover in group for TA-CVS (p<0,05) and in the last five years TA-CVS was performed at 13 weeks gestational age, by a single operator(M.P.) in our department.

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate that the procedure-related risk of miscarriage from the invasive procedure are low, or negligible if groups with similar background risks of chromosomal abnormality are compared. In terms of the safety of the prenatal diagnostic procedure it appears that CVS is potentially safer compared with amniocentesis. Women should be reassured that invasive procedures carried out by experienced operator sin specialist centers, are not associated with a significant increase in miscarriage rate as compared to not undergoing these procedures. In private Department of Obstetrics Podobnik, this study preformed only by single operator (P.M.). In systematic controlled studies for amniocentesis, and the results were as our study, in our hospital. The procedure-related risk of miscarriage following CVS and amniocentesis are lower than currently quoted to women. The risk appears to be negligible when these interventions were compared to control groups with the same profile [

6,

8,

10,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Findings on mosaicisms and other aneuploidies confined, to the placenta, either to the trophoblast or mesenchyme, have been discussed [

2,

4,

5,

13,

14,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

33]. Mosaicisms in short term chorionic villus sampling studies in the first trimester though to occur with a frequency approximately 2-3%, with confirmation not occurring in most patients. Therefore, detection of mosaicisms in short-term chorionic villus sampling studies in ongoing pregnancy is potentially a problem. Additional studies should include chromosome studies of long-term cultures. In our study we found mosaicisms in 55(1%) of cases. These mosaicisms were confirmed or excluded in the fetal blood obtained by cordocentesis, and in our study in 25 cases (45.5%) we had confirmation of mosaicism.

Increased in serum AFP levels following CVS were found in (16. %) cases. We found no correlation between AFP elevation, placental hematoma, Doppler measurements in fetal and maternal circulation and spontaneous abortion after CVS sampling. Transient feto-maternal transfusion was clearly demonstrated in the majority of CVS cases by maternal AFP measurements before and after sampling. The amount of fetal hemorrhage was significantly associated with to the chorionic tissue weight sampled. The volume of placental villi obtained is sufficient in all our CVS procedures for karyotyping, as such a small number of materials is adequate for chromosome analysis. In our laboratory more than five milligrams of chorionic tissue was needed to perform the cytogenetic studies [

19,

20,

32]. Therefore, we have in rare cases detected feto-maternal hemorrhage. The fetal hemorrhage could play in embryo organogenesis by evoking circulatory collapse and tissue hypoxia. Thereafter, severe hemorrhage following vascular disruption could activate the cascade of hyperfusion events producing the observed tissue damages. The success of study Salamon et al. 2019. [

13] yielded 2943 potential citation, from which seven for CVS and 12 related to the rate of limb abnormalities, frequently associated with oro-mandibular hypogenesis, reported in CVS cases undertaken in the earliest period of limb organogenesis, their findings give credibility to the makes credible the hypothesis that sampling has played an etiologic role. There was a slight increase in the incidence of such defects following CVS performed at less than 9 weeks gestational age. However, very early CVS may be associated with an increase in the risk of limb defects through mechanisms that may or not be avoidable with the alteration of sampling technique [

4,

5,

6,

12,

13,

14,

27,

32,

37,

38]. We have never seen any serious limb malformation, because in our study in 50% of cases CVS was performed after 12 weeks of gestation.

Our results suggest that uteroplacental blood flow was not affected by the CVS procedure, and that the subsequent fetal loss rate was not the result of pathological alterations in uteroplacental vasculature. Transabdominal CVS is associated with a lower fetal loss rate than transcervical and transvaginal CVS, may be while amount of villus sampling was lower of 20 mg of chorionic tissue in TA-CVS group. Adequate sample size from CVS is crucial for prenatal diagnosis and there is limited data on factors that are associated with spontaneous abortion after CVS sampling.

Author Contributions

P.P., M.P.,I.BŽ.,and T.M.,m substantial contributions to the conception of this work, drafting the work, revising it critically for important conceptual contents and its final approval; I.L.K.K, J.Đ.,Z.S. and I.M., enrolled patients, acquired clinical data and made substantial contributions to analysis and data interpretation; Z.S., and I.M, made a substantial contribution to data interpretation and critical revision of the article; to analysis and interpretation of data:M.P., P.P.,and T.M., contributed to the interpretation of data and the revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscrip.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval granted by the Ethics Committee of the Podobnik Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology of Zagreb (21. 06. 2008. 1-2).

Informed Consent Statement

informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and the families involved for their cooperation.The authors wish to acknowledge all the research staff and participants involved in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Canadian Collaborative CVS, Amniocentesis Clinical Trial Group. Multicenter randomized clinical trial of chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis. Lancet.1989,1,1-6.

- Jackson and the U. S. NICHD Chorion Villus Sampling and Amniocentesis Study Group. A randomized comparison of transcervical and transabdominal chorionic villus sampling. N Engl J Med. 1992, 327, 594-598.

- Canadian Early and Midtrimester Amniocentesis Trial Group. Randomized trial to assess safety and fetal outcome of early and midtrimester amniocentesis. Lancet. 1998, 351: 242-247.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committae on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics Committae on Genetics;Society for Maternal-fetal Medicine. Screening for Fetal Chromosomal Abnormaluries-ACGO Practice Bulletin,Number 226,Obstet Gynecol.2020,Oc,136(4):e48-e69.

- Jackson and the U. S. NICHD Chorion Villus Sampling and Amniocentesis Study Group. A randomized comparison of transcervical and transabdominal chorionic villus sampling. N Engl J Med. 1992, 327, 594-598.

- Buijtendijk, M.F.; Bet, B.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Shah, H.; Reuvekamp, T.; Goring, T.; Docter, D.; Timmerman, M.G.; Dawood, Y.; A Lugthart, M.; et al. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound screening for fetal structural abnormalities during the first and second trimester of pregnancy in low-risk and unselected populations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 5, CD014715.

- International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology; Bilardo CM, Chaoui R, Hyett Kagan KO, Karim JN, Papageorghiou AT, Poon LC, Salomon LJ, Syngelaki A, Nicolaides KH.ISUOG Practice Guidelines (up- dated): performance of 11-14-week ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023,61(1),127-143.

- Alamri,L; Ludwingston, A; Kaizer, LK; Hamilton,S; Mary, H; Sammel M; Putra, M. Clinical factors that infuence chorionic villus sampling sample size. Arhives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2025, 311, 213-221.

- Liu, S.; Yang, F.; Chang, Q.; Liu, S.; Yang, F.; Chang, Q; Lyan, L; 1,Chen, W; 1,Yin, A;1, Huang F; et al. Positive predictive value estimates for noninvasive prenatal testing from data of a prenatal diagnosis laboratory and literature review. Mol. Cytogenet. 2022, 15, 29–36.9. [CrossRef]

- Podobnik, P; Meštrović,T; Đorđević A; Kurdija,K; Jelčić, Đ; Ogrin,N; Bertović-Žunec,I;Gebauer-Vuković,B;Hoćevar,G;Lončar,I; et al. A Decade of Non-Invasive Prenatal.

- Testing (NIPT) for Chromosomal Abnormalities in Croatia: First National Monocentric Study to Inform Country’s Future Prenatal Care Strategy.Genes.2024,Dec 11,15(12),.

- 1590. [CrossRef]

- Giovannopolou, E; Tsakiridis, I; Mamopoulos,A; Populidis,I; Anastanidis, A; T. Dagklis,T.Invasive Prenatal Diagnostic Testing for Aneuploidies in Singleton Pregnancies:A Cimparative Review of Major Gidlines.Medicina(Kaunas).2022,10, 58-68.

- Crane, JP; Beaver, HA; Cheung, SW. First trimester chorionic villus sampling versus mid-trimester genetic amniocentesis: preliminary results of a controlled prospective trial. Prenat Diagn. 1988, 8, 355-366.

- Navratan,K; Alfirevic, Z; on behaf of the Royal College Of Obstetrician and Gynecologist. Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling.Green-top Guidlance No.8 BJOG,2022,129,pp e-1 3-15. [CrossRef]

- Salomon, L.J.; Sotiriadis, A.; Wulff, C.B.; Odibo, A.; Alolekar, R. Risk of miscarriage following amniocentesis or chorionic villus saqmpling:Systematic review of literature and updated meta analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 54, 442–451. [CrossRef]

- Alfirevic, Z.; Navaratnam, K.; Mujezinovic, F. Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD003252. [CrossRef]

- Hui, L; Ellis, D; MayenD; Mark, D; Pertile, M; Reiner, R; Sun, L; Vora N; Lyn, S; Chitty, L. “Position Statement From the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis on the Use of Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing for the Detection of Fetal Chromosomal Conditions in Singleton Pregnancies”.Penatal Diagnosis. 2023, no. 7 (06 2023): 814– 828. [CrossRef]

- Yeon, LI; Young, K; Sunghun, N; et al.Practise guidelines for prenatal aneuploidy screening and diagnostic testing from Korean Society of maternal-fetal medicine. Invasive diagnostic testing for fetal chromosomal abnormalities. J Korean Med Sci. 2021, 25, 36 (4),326-88.

- Holzgreve, W; Ginsberg, N; Ammala, P; Dumez, Y. Risk of CVS. Prenat. Diagn 1993, 13, 197-209.

- MCR Working Party on the Evaluation of Chorionic Villus Sampling. Medical Research Council European Trial of chorionic villus sampling. Lancet. 1991, 337, 1491-1499. [CrossRef]

- Singer, Z; Profeta, K. Chorionic frondosum cultivation technique in antenatal detection of genetic disease. Period. Biol. 1989, 91, 77-81.

- Podobnik, M; Ciglar, S; Singer Z; Podobnik-Šarkanji, S; Duic, Z; Skalak, D. Transabdominal chorionic villus sampling in the second and third trimester of high-risk pregnancies. Prenatal Diagnosis. 1997,17,125-133.

- Smidt-Jensen, S; Lundsten, C; Lind, AM; Dinesen, K; Philip, J. Transabdominal chorionic villus sampling in the second and third trimester of pregnancy: chromosome quality, reporting time, and feto-maternal bleeding. Prenat Diagn. 1993. 13, 957-969. [CrossRef]

- Tzela,P; Antsaklis,P; Kanellopolus,D; Antonakopoluos, N;Gourounti K. Factor Influencing the Decision-Makinhg Process for Undergoing Invasive Prenatal Testing. Cureus. 2024 Apr;16(4)358803.

- Petousis, S; Sotiriadis, A; Margioula-Siarkou, C;Tsakiridis, I;Christidis P, Kyriakakis M. Detection of structural abnormalities in fetuses with normal karyotype at 11-13 weeks using the anatomic examination protocol of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG). Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2020;33(15):2581-7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, BB; Rubin, CH; Williams II, J. Mosaicism in chorionic villus sampling: an analysis of incidence and chromosomes involved in 2612 consecutive cases. Prenat. Diagn. 1993,13:179-190. [CrossRef]

- Reilly, S. Doyle, S. J. Hamilton, M. D. Kilby, and F. Mone, “Pitfalls of Prenatal Diagnosis Associated With Mosaicism,” Obstetrician and Gynaecologist 25, no. 1 (January 2023): 28–37.

- Liao, Y; Wen, H; Ouyang, S; Guan,Y;,Bi J; Fu, Q; Yang,X; Guo, W; Huang,Y;Zeng,Q;et al. Routine firsttrimester ultrasound screening using a standardized anatomical protocol. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2021;224(4):396.e1-396.e15.

- Kagan,KI; Sonek,J;Kozlowski, P.Antenatal screening for chromosomal abnormalities. Arch Gynecol Obstet.2022,13:305(4),825-835. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A; Sotiriadis, A; D’Antonio, F; Da Silva Costa, F; Odibo, A; Prefumo, F; Papageorghiou, AT; Salomon, LJ. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: perform- ance of third-trimester obstetric ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2024Jan; 63(1):131-147. [CrossRef]

- Spingler, J; Sonek, M; Hoopmann, N; Prodan, H; Abele; Kagan,KI. “Complication Rate After Termination of Pregnancy for Fetal Defects,” Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynes and Gynecology 62, no. 1 (July 2023): 88–93, . [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Overbeek, TK; Jahoda, MGJ; Wladimiroff, JW. Uterine blood flow velocity waveforms before and after transcervical chorionic villus sampling. Ultrasound in Med.& Biol. 1990, 16, 129-1323.

- 31 Arduini, D; Rizzo, G. Umbilical artery velocity waveforms in early pregnancy: A transvaginal color Doppler study. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 1991,19, 335-339. [CrossRef]

- Podobnik, M.; Ciglar, S.; Singer, Z.; Gebauer, B., Podgajski, M. Doppler assessment of fetal circulation during late chorionic villus sampling in high risk pregnancies. Prenat. Neonatal Med. 1998, 3 (Suppl. S1), 9.

- Maines,J; Montero,FJ. Chorionic villus sampling. InStatPearlsd.Publishing in Theasure Island,FL,USA 2025.

- Akolekar, R; Beta, JL; Piccarelli, G; Olive, C; Dantonio, F. Predictive related risk of miscarriage following amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015, 45, 16-26. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M; Birnie, E; Robles de Medina, P; Sollie, KM; Pajkrt, EL; Bilardo, CM. Total pregnancy loss after chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis: a cohort stud. Ulrasound Obstet gynecol. 2017, 49, 599-606. [CrossRef]

- Ching-Hua, H; Jia-Shing, C; Yu-Ming, S; Yann-Jang,L; Chen Yi-Cheng, Wu. Prenatal diagnosis using chromosomal microarray analysis in high- risk pregnancies. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 3624-3644.

- Brambati, B; Tului, L; Lislaghi, C; Alberti, E; First 10 000 chorionic villus sampling pereformed on singleton pregnancies by a single operator. Prenatal Diagn. 1998, 3, 255-266.

- Firth, HV; Body, PA; Chamberlain, P; Mackenzie, IZ; Lindenbaum, RH; Huson, SM. Severe limb abnormalities after chorionic villus sampling at 56-66 days gestation. Lancet.1991, 337,127-135. [CrossRef]

- Saura, R; Longy, M; Horovitz, J; Grison, O; Vergaud, A; Taine, LN; et al. Risk of transabdominal chorionic villus sampling before 12 week of amenorrhea. Prenatal diagnosis. 1990, 10, 461-467. [CrossRef]

- Holzgreve, W; Ginsberg, N; Ammala, P; Dumez, Y. Risk of CVS. Prenat. Diagn 1993, 13, 197-209.

- Saura, R; Longy, M; Horovitz, J; Grison, O; Vergaud, A; Taine, LN; et al. Risk of transabdominal chorionic villus sampling before 12 week of amenorrhea. Prenatal diagnosis. 1990, 10, 461-467. [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, K; Soothil, PW; Rodeck, CH;, Waren, RC; Gosden, CM. Why confine chorionic villus (placental) biopsy to the first trimester. Lancet. 1986b, 1,543-544. [CrossRef]

- Smidt-Jensen, S; Lundsten, C; Lind, AM; Dinesen, K; Philip, J. Transabdominal chorionic villus sampling in the second and third trimester of pregnancy: chromosome quality, reporting time, and feto-maternal bleeding. Prenat Diagn. 1993. 13, 957-969. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).