1. Introduction

Entropy appears throughout physics in multiple forms.

1 Each formulation is mathematically precise within its own domain, yet the physical meaning of “entropy” and the origin of the Second Law remain conceptually unsettled. Is entropy a measure of disorder, missing information, spatial mixing, quantum entanglement, coarse-graining, or something else? The existence of many definitions has encouraged the view that “entropy” is inherently context-dependent and must be reinterpreted in each subfield [

7].

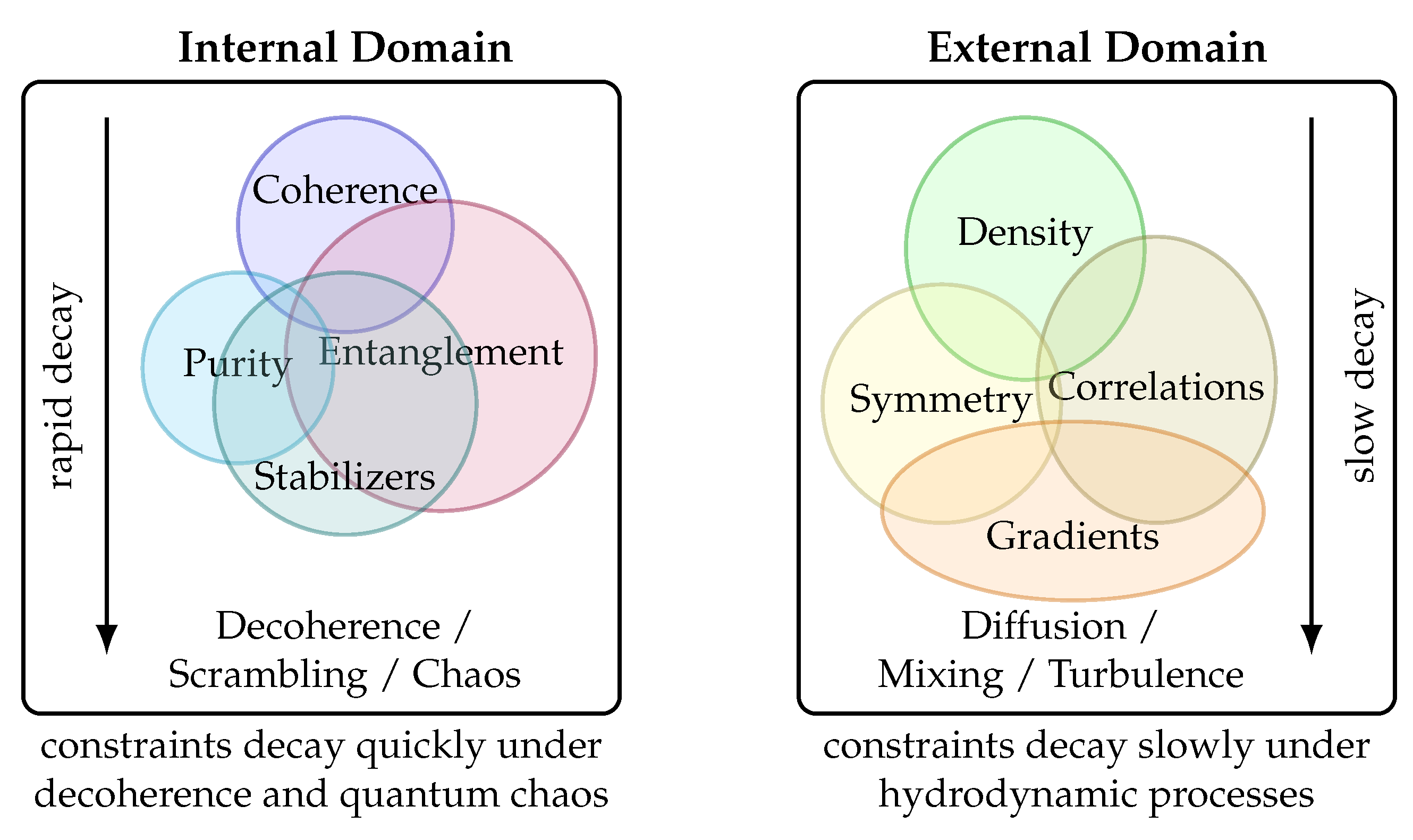

In this work we propose a unified conceptual and mathematical foundation for entropy based on a simple structural insight: every entropy notion in physics counts the number of microstates compatible with a given set of global physical constraints. These constraints may be internal (quantum coherence relations, entanglement structure, stabilizer conditions) or external (spatial gradients, macroscopic correlations, hydrodynamic fields), but they play the same logical role: each constraint restricts the allowable relationships among the system’s degrees of freedom, and the intersection of all surviving constraints determines the admissible microstate region.

Let

C denote the system’s current global constraints. The associated admissible microstates form the region

where

X is the full kinematic state space appropriate for the system [

8,

9]. The

constraint volume

counts these microstates, and the entropy

measures the size of this constraint-defined region. This definition recovers the Boltzmann entropy (external macroscopic constraints), the von Neumann entropy (internal quantum constraints), coarse-grained entropies, and all standard equilibrium ensembles as special cases [

8,

10]. It does so without invoking subjective information, arbitrary coarse-graining, or preferred subsystem partitions.

A second key observation is dynamical. In physically realistic, non-integrable systems with local interactions,

global constraints generically decay over time. Internal constraints—such as phase coherence and entanglement structure—are degraded by decoherence [

11], scrambling, eigenstate thermalization [

12,

13], and quantum chaos [

14]. External constraints—such as spatial correlations and macroscopic gradients—are weakened by mixing, diffusion, turbulence, and classical chaos [

15]. Although integrable or symmetry-protected models preserve special constraint structures, these represent a measure-zero subset of Hamiltonians and do not describe generic matter.

For almost all physical systems, microscopic interactions enlarge the set of compatible microstates over time:

This purely structural implication is formalized as the Constraint Monotonicity Theorem. It yields an objective, model-independent form of the Second Law: entropy increases because local interactions erode global consistency relations.

This perspective resolves a longstanding conceptual misunderstanding:

time is not entropy. Time orders physical states; entropy measures the volume of microstates compatible with the present constraint structure. Microscopic evolution (Hamiltonian or unitary) is reversible, and nothing in the definition of entropy requires monotonicity. Entropy growth is instead a

contingent consequence of the generic weakening of global constraints, absent special symmetries or integrable structures [

16].

The goal of this paper is to develop this constraint-based foundation for entropy in a precise and unified manner. Our main contributions are:

We introduce a general definition of entropy as the logarithmic volume of microstates compatible with the system’s surviving global constraints, treating internal and external degrees of freedom on equal footing.

We identify the dynamical mechanism responsible for entropy increase in realistic physical systems: local interactions generically weaken global constraints, thereby enlarging the admissible microstate region.

We prove a structural Second Law (Constraint Monotonicity Theorem), demonstrating that constraint weakening necessarily increases entropy, independently of coarse-graining or subjective information.

We recover classical thermodynamic entropy and equilibrium ensembles as limiting cases that emerge once internal coherence constraints have fully decayed.

We show through explicit examples how the unified framework describes entropy increase in quantum systems (decoherence, entanglement decay), classical systems (mixing, diffusion), and hybrid systems (melting, turbulent relaxation).

We clarify the conceptual distinction between time and entropy, showing that irreversibility arises from the erosion of global constraints rather than from any intrinsic temporal asymmetry.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 defines global constraints and introduces the associated microstate sets.

Section 3 presents the constraint-volume definition of entropy.

Section 4 analyzes the physical mechanisms by which global constraints decay under generic local dynamics.

Section 5 proves the Constraint Monotonicity Theorem.

Section 6 shows how classical thermodynamics emerges as a special case.

Section 7 applies the framework to quantum entropy and decoherence.

Section 8 provides illustrative examples across internal, external, and hybrid systems.

Section 9 discusses integrability and other exceptions.

Section 10 clarifies why time is not entropy. We conclude in

Section 11 with conceptual implications and future directions. Technical details are collected in the appendices.

2. Global Constraints as the Foundation of Entropy

Entropy, in every domain of physics, quantifies the size of the microstate space compatible with the macroscopic or mesoscopic conditions that the system currently satisfies [

10]. These conditions—energy conservation, spatial organization, quantum coherence patterns, symmetries, topological relations, or environmental couplings—all take the mathematical form of

constraints. This section formalizes the notion of a global constraint, explains its physical motivation, and introduces the associated microstate sets that will underlie the definition of entropy.

See Appendix A for the formal structure of constraints.

2.1. Global Constraints: Definition and Motivation

A physical system with degrees of freedom

X (which may be classical, quantum, or hybrid) does not typically explore the entirety of its kinematic space. Its admissible configurations are restricted by a variety of

global constraints, which may arise from physical laws, environmental couplings, or dynamical history [

8].

These constraints fall into two broad categories:

Internal constraints.

These involve relations among internal, often non-spatial, degrees of freedom. Examples include:

quantum coherence and phase relations [

11],

entanglement patterns and stabilizer conditions in many-body systems [

9],

subsystem purity constraints,

internal symmetries or superselection rules,

algebraic constraints on internal states.

Internal constraints determine which quantum states, reduced density matrices, stabilizer configurations, or internal polarization patterns the system may occupy. Decoherence and quantum chaos [

14] typically degrade these constraints over time.

External constraints.

These involve relations among spatial or macroscopic degrees of freedom. Examples include:

macroscopic density distributions or gradients,

velocity fields and hydrodynamic profiles,

geometric arrangements or spatial correlation structures,

boundary conditions or conserved macroscopic moments,

large-scale order (e.g. crystalline, liquid, or flocking structures).

External constraints describe the macroscopic organization of mass, energy, momentum, and spatial correlations. They are degraded by diffusion, mixing, turbulence, classical chaos, and hydrodynamic relaxation [

15].

Despite appearing fundamentally different, both internal and external constraints share the same logical role: they restrict the admissible microstates of the system. It is this restriction—not the specific nature of the degrees of freedom—that entropy quantifies.

2.2. Constraint Sets and Admissible Microstates

Let

X denote the kinematic microstate space of the system (phase space in the classical case, or a Hilbert space or operator algebra in the quantum case). A global constraint restricts the system to a subset of

X. Multiple constraints narrow this subset via intersection [

8].

Definition 1. A

constraint set C is a collection of global relations among the degrees of freedom of a physical system. The corresponding set of compatible microstates is

Thus:

adding a new constraint shrinks ,

removing a constraint enlarges ,

and the admissible microstate space is fully determined by the intersection of all relations in C.

2.2.0.3. Examples.

In a dilute classical gas,

C may specify the total energy, particle number, and the absence of macroscopic gradients. Then

is the usual microcanonical shell of phase space [

8].

In a quantum measurement scenario,

C may encode the preserved branch structure or pointer observables. Removing internal coherence constraints enlarges

to include decohered mixtures [

11].

In a many-body quantum system, C might impose stabilizer relations or entanglement conditions. Scrambling dynamics weaken these, enlarging the set of compatible density matrices.

In a macroscopic fluid, C may include hydrodynamic simplifications or macroscopic organization. Turbulence and mixing degrade these constraints, enlarging .

This formalism applies uniformly across classical and quantum mechanics, with the only difference being the nature of the underlying space X.

2.3. Constraint Weakening and Physical Evolution

Physical dynamics typically act locally: interactions couple degrees of freedom within finite spatial range or finite circuit depth [

9]. Such local interactions do not, in general, preserve global relations. Instead, they tend to

weaken or

destroy global constraints unless symmetry-protected.

Let

denote the constraint set satisfied at time

t. For generic, non-integrable systems, we typically have

meaning some global relations no longer hold at later times. This inclusion expresses the physical fact that global coherence, long-range organization, or macroscopic regularity are eroded by local microscopic interactions.

At the microscopic level, internal constraints are degraded by:

eigenstate thermalization [

12,

13],

environmental coupling.

At the macroscopic level, external constraints are degraded by:

diffusion and transport,

mixing and chaotic advection [

15],

hydrodynamic relaxation.

The only exceptions are highly structured, fine-tuned systems: many-body localized phases [

17]. These systems preserve special global constraints but constitute a measure-zero subset of physically relevant models. In all realistic interacting systems, constraint weakening is the generic outcome of dynamical evolution.

This monotonic reduction of constraints will form the basis for the structural Second Law established in the next section.

For a formal treatment of constraint sets under dynamical evolution, see Appendix F.2.

2.4. Mathematical Assumptions and Scope

The structural results developed in this work rely on a small set of standard assumptions about state spaces, measures, and constraint sets. For clarity, we summarize them here.

1. Measurable state space.

The kinematic microstate space

is assumed to be a measurable space equipped with a

-finite reference measure

[

25,

74]. Classical phase space carries Liouville measure; quantum state space is endowed with a unitarily invariant measure (Hilbert–Schmidt, Bures, or Haar-induced).

2. Measurable constraints.

Each constraint

c selects a measurable set

, and constraint sets are countable families

with admissible region

Measurability of intersections is assumed.

3. Finite or normalized admissible volume.

Whenever the absolute entropy

is used, we assume

For infinite-dimensional or continuous systems where volumes diverge, all physical quantities are defined either through:

ratios of volumes (entropy differences),

finite-volume regularization on spatial domains, or

normalized reference measures (see Appendix C for details).

This guarantees that every logarithm appearing in the main text is well-defined.

4. Continuity under parameter perturbations.

Constraint families depending smoothly on continuous parameters are assumed to vary measurably, ensuring continuity of admissible volumes and of

under mild regularity assumptions [

56,

57].

5. Dynamical evolution of constraints.

For a measurable semigroup

, dynamical updates of constraints are defined by pullback,

We assume that is measurable (and measure-preserving when required), ensuring that admissible volumes remain well-defined.

6. Asymptotic regions.

When analyzing long-time behavior, asymptotic constraint sets

are assumed nonempty and measurable (guaranteed when

X is compact or when

is mixing/ergodic with a unique invariant measure; see Appendix F).

7. Integrable systems as boundary cases.

Integrable systems are characterized by conserved quantities whose level sets have finite, nonzero measure; for such systems the admissible region is invariant, and remains constant.

These assumptions are mild, standard in statistical mechanics and quantum information theory, and sufficient to guarantee that all volume, entropy, and constraint-evolution relations appearing in the main text and appendices are mathematically well-defined.

3. Constraint–Volume Entropy

Entropy quantifies the size of the microstate set compatible with the system’s surviving global constraints [

7,

10]. Once a constraint set

C and its admissible region

are specified, the entropy follows directly from the volume of that region. This section introduces the formal definition and explains how it provides a unified foundation for every major notion of entropy in physics.

3.1. Definition of Constraint–Volume Entropy

Let X denote the kinematic microstate space of a physical system. Depending on context, X may be:

a classical phase space with symplectic structure [

8],

a Hilbert space or projective Hilbert space of pure states,

the convex set of density operators equipped with a unitarily invariant measure [

9],

or a hybrid classical–quantum state space.

Given a constraint set

C, the admissible microstate manifold is

Because constraints restrict the allowable relations among degrees of freedom, is generally a strict subset of X.

Definition 2 (Constraint–volume entropy). Given a constraint set

C, define its

constraint volume

where

is the natural invariant measure on

X (Liouville measure for classical systems [

18], Hilbert–Schmidt or unitarily invariant measure in quantum mechanics [

9]). The corresponding

constraint–volume entropy is

This definition is coordinate-free and physically objective: entropy depends only on the measure of the admissible region of state space, not on any particular parametrization. The volume measure is chosen to respect the symmetries of the underlying theory (Hamiltonian invariance in classical mechanics, unitary invariance in quantum theory), ensuring that reflects intrinsic physical structure.

Systems with many intact constraints have small admissible sets and therefore low entropy; systems in which constraints have weakened or been destroyed have large admissible sets and correspondingly high entropy.

For continuous or infinite-dimensional systems (e.g. classical fields or quantum fields), volumes require ultraviolet and infrared regularization. A systematic treatment is given in Appendix D (see also for field-theoretic background).

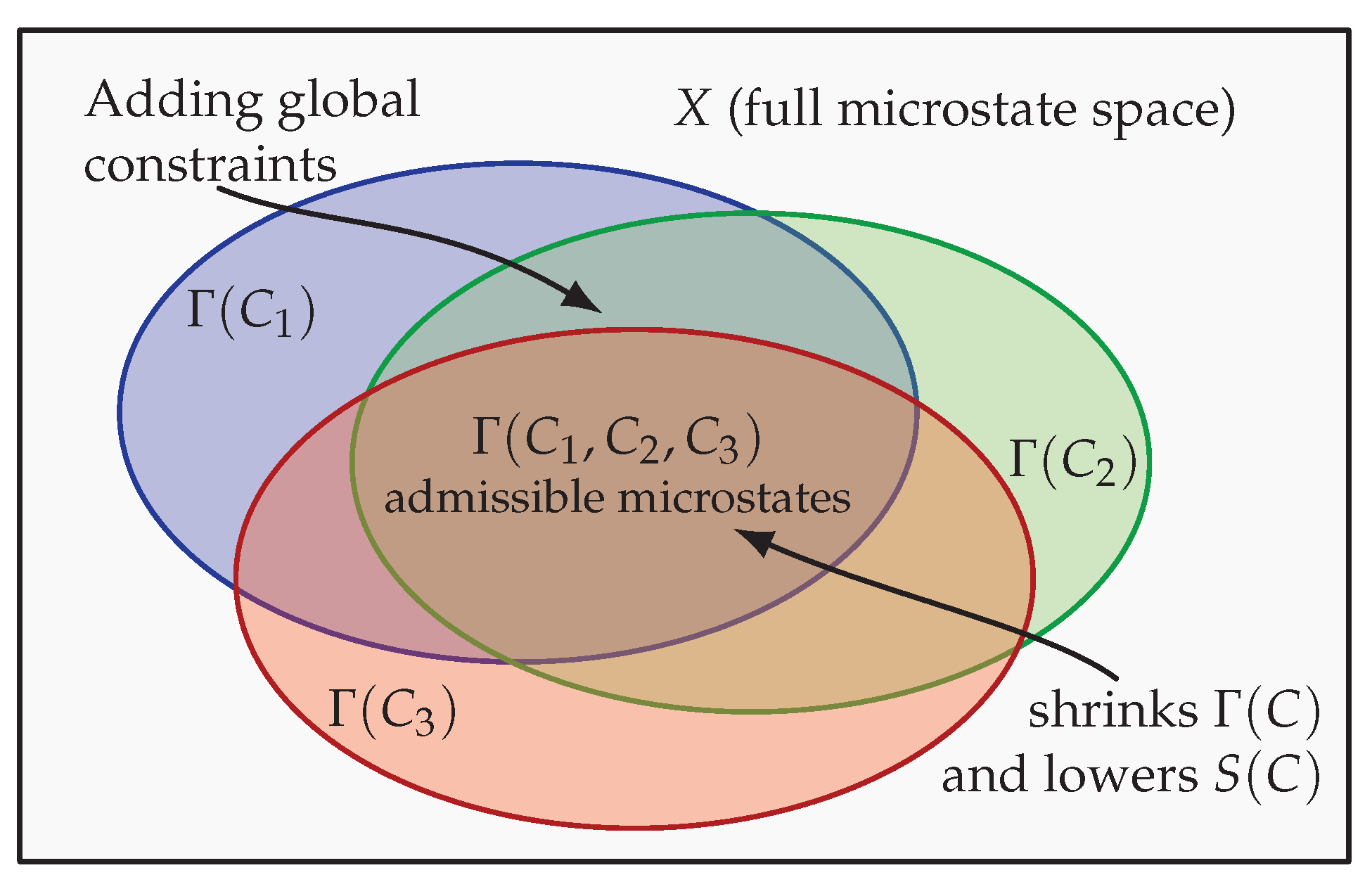

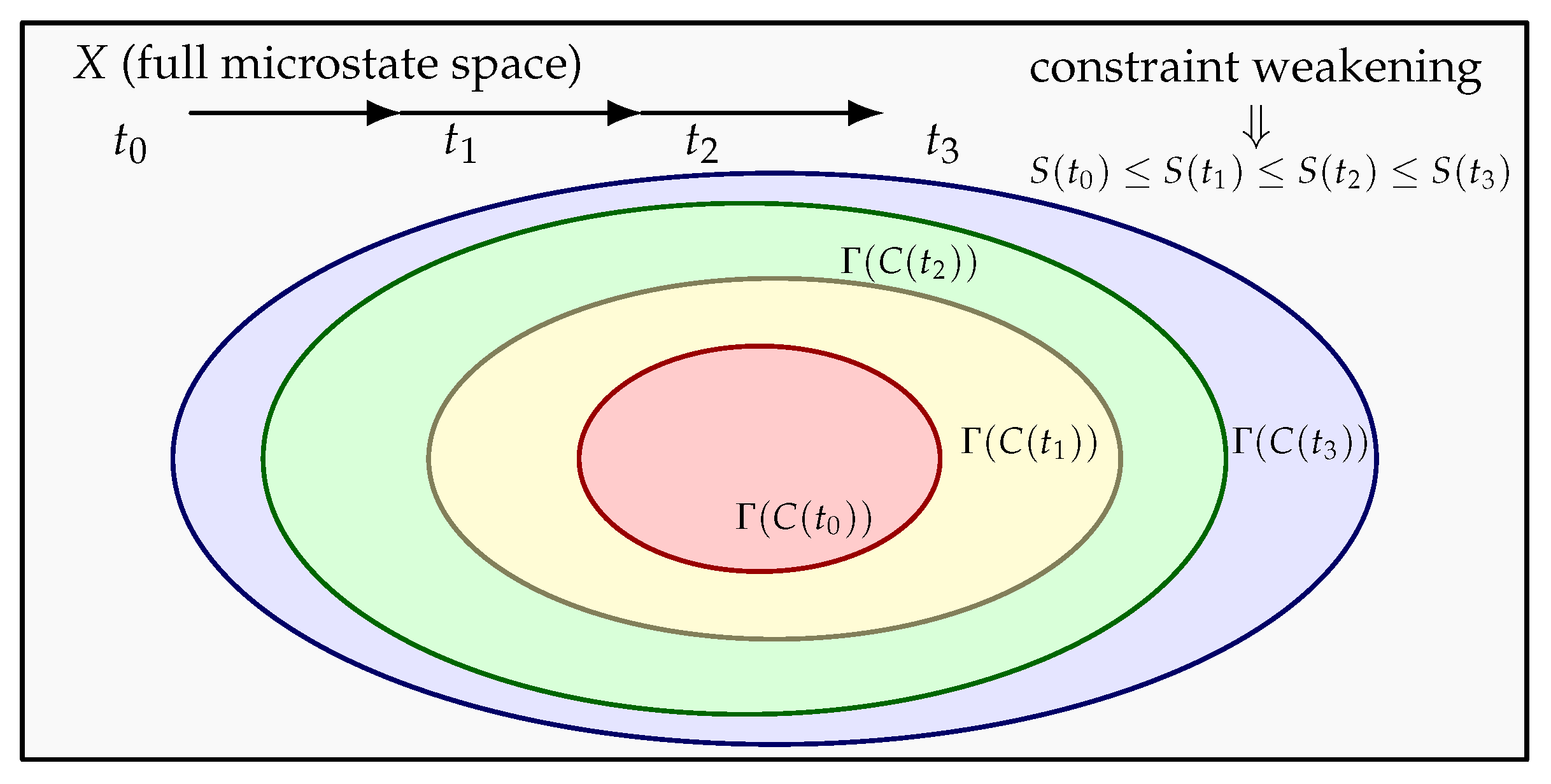

Figure 1 illustrates the geometry of constraint sets: as constraints decay under generic local dynamics, the admissible region

expands and the constraint–volume entropy increases.

3.2. Relation to standard entropy notions

Although the expression resembles the familiar Boltzmann entropy, the definition given here is significantly more general and subsumes all major entropy concepts in physics.

Boltzmann entropy (classical external DOFs).

If

C specifies macroscopic constraints such as fixed energy, volume, and particle number, then

coincides with the corresponding energy shell or macrostate region of classical phase space. The constraint–volume entropy reduces to the usual Boltzmann entropy [

19],

Gibbs–Shannon entropy.

When constraints specify a probability distribution over phase space or restrict the allowed distributions, the constraint–volume formulation captures the maximal Shannon entropy subject to those constraints, providing a natural bridge to Jaynes’ maximum-entropy formalism [

2,

10].

von Neumann entropy (quantum internal DOFs).

When

X is the space of density matrices and

C encodes all linear constraints defining a given density operator (trace 1, positivity, specified reduced states), the constraint volume becomes the measure of all purifications or all internal states compatible with those constraints. In the continuum limit, this recovers von Neumann entropy [

20].

Entanglement entropy.

If

C specifies fixed reduced density matrices for subsystems or fixed entanglement constraints, then

is the space of pure states with those marginals. Its volume reproduces the entanglement entropy of the subsystem, as established in geometric derivations of bipartite entanglement measures [

3].

Coarse-grained and hydrodynamic entropy.

Macroscopic fields, such as density distributions or velocity profiles, define constraints on the microscopic configuration. The volume of microstates compatible with these fields yields the coarse-grained entropy used in nonequilibrium statistical mechanics and hydrodynamics [

21].

Black-hole and horizon entropy.

Geometric horizon constraints restrict admissible spacetime or quantum gravitational microstates. The Bekenstein–Hawking entropy can be interpreted as the logarithm of the volume of microstates compatible with these geometric constraints [

4,

5], placing horizon entropy within the same framework.

Thus the constraint–volume entropy unifies classical, quantum, information-theoretic, and gravitational entropies within a single mathematical object: the volume of admissible microstates.

The subtleties associated with infinite-dimensional configuration spaces and their regularization are addressed in Appendix D.

3.3. Novelty of the Constraint–Volume Viewpoint

The novelty of the present framework is not the expression

itself, which dates back to Boltzmann [

19], but rather the recognition that entropy always counts microstates compatible with the system’s

current global constraints, regardless of whether these constraints are:

internal or external,

quantum or classical,

microscopic, mesoscopic, or macroscopic,

spatial, algebraic, topological, or coherence-based.

In standard treatments, different entropies arise from different interpretations of

and from different types of constraints: Boltzmann’s entropy uses macroscopic external constraints; von Neumann entropy uses subsystem constraints; entanglement entropy uses reduced state constraints; coarse-grained entropy uses spatial averaging constraints; and information-theoretic entropy uses probabilistic constraints [

7,

9].

Here all of these disparate notions are unified by the simple structural statement:

This viewpoint eliminates the need for:

It also sets the stage for the structural Second Law derived in the next section: since local interactions generically degrade global constraints, the admissible microstate volume grows monotonically, leading to the objective increase of entropy.

4. Dynamics: Why Global Constraints Decay

Global constraints encode nonlocal relations among the degrees of freedom of a system [

22]. These relations may correspond to spatial organization, quantum coherence [

11], entanglement patterns, stabilizer conditions, hydrodynamic fields [

21], or symmetry constraints. Physical interactions, however, are typically local: they couple degrees of freedom only within finite spatial ranges or finite circuit depths [

23]. Local interactions do not generically preserve global structure. Instead, they tend to weaken or destroy it unless protected by special symmetries. This section explains, in a unified manner, the dynamical mechanisms responsible for the generic decay of global constraints in both internal and external degrees of freedom.

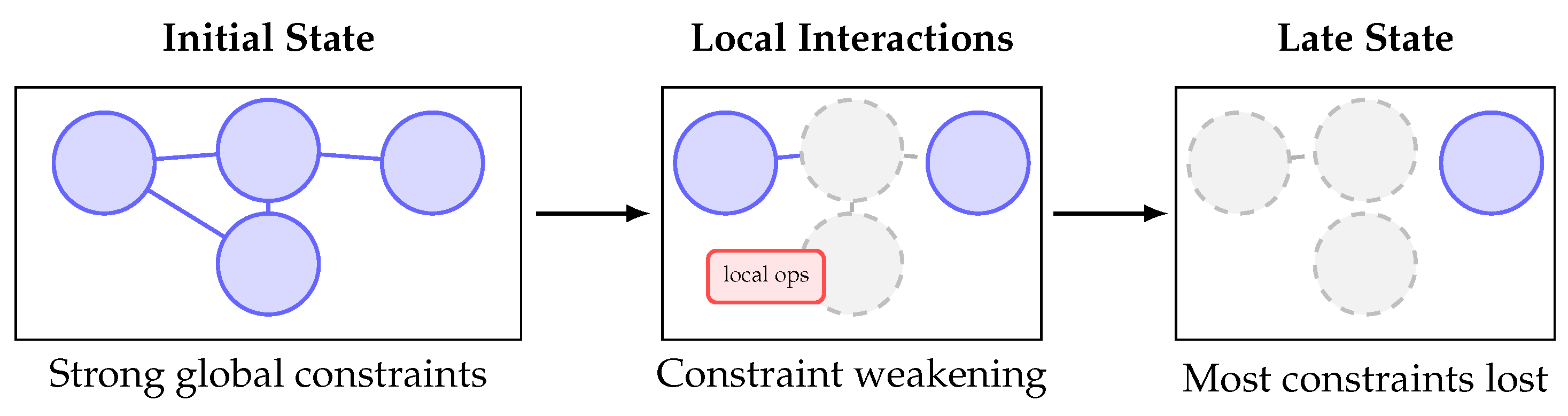

Figure 2 illustrate how local dynamics disrupts constraints.

4.1. Internal Degrees of Freedom

Internal degrees of freedom include quantum phases, coherence relations, entanglement structure, reduced density matrices, stabilizer conditions, spin correlations, and algebraic relations among subsystem states. These internal constraints are highly sensitive to the system’s local dynamics [

9].

For quantitative timescales governing the decay of these internal constraints, see Appendix E.

Decoherence.

A system interacting with an environment undergoes decoherence: phases between different pointer states are rapidly suppressed [

11], reducing the set of compatible pure states. The constraint set

loses coherence-based relations, and

enlarges accordingly.

Entanglement scrambling.

Unitary evolution under generic many-body Hamiltonians spreads quantum information across the system. Initially localized correlations become delocalized, and subsystem constraints (fixed marginals or purity) are weakened.

Eigenstate Thermalization (ETH).

For non-integrable quantum systems, ETH implies that the reduced state of almost any late-time subsystem becomes indistinguishable from the microcanonical ensemble [

12,

13]. This corresponds to the loss of detailed internal correlations and the replacement of strict constraints with coarse macroscopic ones.

Quantum chaos.

Underlying both scrambling and ETH is quantum chaos: exponential sensitivity to perturbations and rapid mixing in Hilbert space [

14]. Quantum chaos erodes fine-grained coherence constraints, increasing the admissible microstate volume.

In all these cases, internal constraints are fragile: even weak local interactions typically disrupt the relations defining them.

4.2. External Degrees of Freedom

External degrees of freedom include spatial distributions, density gradients, velocity fields, geometric ordering, macroscopic shapes, correlation structures, and momentum-space organization. Local microscopic interactions degrade these constraints through several universal dynamical mechanisms [

15].

For quantitative timescales governing the decay of these external constraints, see Appendix E.

Diffusion and transport.

Particle collisions or hopping processes smear out spatial density gradients [

24]. As diffusion acts, structured configurations become more uniform.

Mixing.

In classical Hamiltonian systems and deterministic flows, mixing dynamics exponentially stretch and fold phase-space volumes [

15]. Macroscopic correlations are destroyed.

Turbulent cascades.

In fluid dynamics, turbulent cascades break down coherent macroscopic flow structures. Vorticity fields become randomized.

Hamiltonian chaos.

Chaotic Hamiltonian dynamics cause exponential divergence of trajectories, erasing simple spatial or momentum-space relations.

Gravitational relaxation.

In astrophysical systems, N-body interactions relax macroscopic structures toward virial equilibrium, erasing detailed correlations.

External constraints are robust at short times but generically decay under nonlinear interactions, transport processes, or chaotic flows.

4.3. Integrable and Symmetry-Protected Exceptions

Although global constraints generically decay, exceptions exist. These exceptions illuminate rather than undermine the mechanism behind constraint decay.

Integrable cases are detailed in Appendix B.

Integrable systems.

Classical integrable systems possess as many conserved quantities as degrees of freedom. Quantum integrable systems possess extensive sets of commuting integrals of motion. These additional constraints prevent mixing, scrambling, or thermalization.

Many-body localization (MBL).

In MBL phases, disorder induces an extensive set of quasi-local conserved quantities [

17], preventing the spreading of entanglement.

Symmetry-protected or topologically protected subspaces.

Certain constraints cannot be broken by local interactions due to symmetry or topology.

Measure-zero character.

Integrable and protected systems constitute a measure-zero subset of Hamiltonians: perturbations typically break the additional constraints.

4.4. Unified Mechanism of Constraint Decay

Despite differences between internal and external degrees of freedom, the mechanism of constraint decay is universal:

Local interactions propagate information only within finite ranges and do not generically preserve global relations. Consequently, global constraints decay unless protected by special symmetries.

Internal constraints—coherence, entanglement structure, stabilizer relations—are eroded by scrambling, decoherence, and chaotic unitary dynamics. External constraints—spatial distributions, hydrodynamic fields, macroscopic gradients—are eroded by transport, mixing, turbulence, and classical chaos.

In both cases:

so the admissible microstate volume expands. This monotonicity forms the basis of the structural Second Law proven in the next section.

See

Figure 3 for a schematic illustration.

5. The Constraint Monotonicity Theorem (The Second Law)

The central claim of this framework is that entropy increase in physical systems is a structural consequence of the weakening of global constraints under generic local dynamics. In this section we make this statement precise. The result does not depend on statistical assumptions, coarse-graining, or probabilistic interpretation [

7]. It follows solely from the set-theoretic relation between constraint sets and the admissible microstate volumes that they define.

5.1. Statement of the Theorem

Let

denote the set of global constraints satisfied by the system at time

t, and let

be the corresponding admissible microstate set. The structural Second Law follows from the monotonicity of

under constraint inclusion [

25].

Theorem 5.1 (Constraint Monotonicity).

If physical evolution from time t to time weakens the global constraint set, meaning

then the constraint–volume entropy satisfies

with equality if and only if the constraints are unchanged.

Before proving the theorem, it is useful to restate the inclusion condition in physical terms. The relation means that some global relations no longer hold at the later time. Equivalently, the system is compatible with a larger set of microstates than before.

A full proof of the monotonicity of constraint volumes is provided in Appendix F.1.

5.2. Proof of the Theorem

Proof. If

, then any microstate satisfying all constraints in

C necessarily satisfies all constraints in

. Thus the admissible microstate sets satisfy

Since

is a monotone measure on

X [

25], we have

with equality if and only if

. Applying

gives

Setting and yields the desired result. □

This completes the structural derivation of the Second Law: entropy cannot decrease when global constraints are weakened.

Details of the proofs are presented in Appendix F.

5.3. Interpretation and Physical Significance

The Constraint Monotonicity Theorem identifies the Second Law as an order-theoretic statement. It is not a probabilistic law, nor is it tied to coarse-graining or ignorance; instead, it expresses a purely mathematical relation:

Entropy increases precisely when the system becomes compatible with a strictly larger set of microstates.

Local microscopic interactions tend to destroy global relations, so in almost all realistic systems the constraint set weakens over time, and entropy correspondingly increases [

22].

Appendix E analyzes the characteristic timescales associated with constraint decay and the resulting entropy production rates.

5.4. Corollaries

The theorem has several immediate and important consequences.

1. No coarse-graining is required.

The proof uses no approximation or averaging procedure. Entropy increase follows from the weakening of actual physical constraints, not from smoothing out fine details.

2. No subjective information is invoked.

Unlike informational interpretations of entropy, the present framework does not depend on an observer’s knowledge or ignorance [

10]. The entropy is an objective property of the constraint structure.

3. The subsystem decomposition is irrelevant.

Because C is defined independently of any particular partitioning of the system, the entropy does not rely on tracing out degrees of freedom.

4. Reversibility vs. irreversibility.

Microscopic dynamics (classical Hamiltonian flow or unitary evolution) preserve the underlying measure (Liouville theorem [

18] and unitarity [

20]), but constraint decay is not reversible. If global relations are lost, nothing guarantees their spontaneous reconstruction without fine tuning.

5. Equality conditions.

The entropy is constant during intervals for which

, i.e. when the dynamics preserve the constraint set. This occurs in integrable, many-body localized, or symmetry-protected systems and represents the precise boundary case of the Second Law [

17].

5.5. Summary

The Constraint Monotonicity Theorem identifies the Second Law of thermodynamics as a mathematical consequence of two facts:

- (1)

The system’s admissible microstate space is determined by its surviving global constraints.

- (2)

Generic local interactions weaken global constraints over time, enlarging the admissible microstate space.

Entropy increase therefore arises universally in realistic physical systems, independently of coarse-graining, statistical assumptions, or subjective uncertainty. It is the structural signature of constraint decay. See

Figure 4.

6. Classical Thermodynamics as a Special Case

The previous sections established entropy as the logarithmic volume of microstates consistent with the system’s global constraints. In general, these constraints involve both internal degrees of freedom (e.g., quantum coherence relations, entanglement structure) and external degrees of freedom (e.g., spatial correlations, macroscopic gradients). Classical thermodynamics corresponds to a regime in which all internal constraints have decayed, due to rapid decoherence and entanglement scrambling, while the remaining significant constraints are purely external and macroscopic.

In this section we show that, under these conditions, the constraint volume reduces to familiar expressions from equilibrium statistical mechanics [

8], including the Boltzmann entropy [

19], the microcanonical ensemble, and the canonical ensemble [

10]. We also explain how hydrodynamic behavior emerges from constraint decay in macroscopic fields.

6.1. Reduction to Macroscopic External Constraints

Let

denote internal coherence or entanglement constraints, and let

denote macroscopic external constraints such as total energy, particle number, total momentum, or conserved spatial moments. In generic macroscopic systems, decoherence and quantum scrambling drive

leaving only external constraints relevant at thermodynamic timescales. Thus the full constraint set reduces to

Global correlations encoded in are far more robust than internal quantum constraints, but they too eventually decay through diffusion, mixing, and hydrodynamic relaxation.

In this regime the admissible microstate set is

and the constraint-volume entropy reduces to the Boltzmann entropy when

specifies the usual macroscopic variables [

19].

6.2. Recovery of the Boltzmann Entropy

Suppose

specifies energy

E, particle number

N, volume

V, and possibly total momentum

P or angular momentum

L. Then

is the classical energy shell of phase space, defined through Liouville’s measure [

18]. The microcanonical volume is

Thus the constraint–volume entropy becomes

the standard Boltzmann entropy [

19]. No coarse-graining or probabilistic assumptions are required: the external constraints directly determine the measure of admissible states.

6.3. Emergence of Equilibrium Ensembles

Equilibrium ensembles arise naturally from constraint weakening. As the system interacts weakly with an environment or a large reservoir, the constraint set changes:

Formally, if the environment imposes weak constraints on mean values of observables

,

the maximum allowable constraint volume corresponds to the Gibbs distribution [

8]

which is the unique state maximizing

subject to the remaining constraints [

10].

Thus classical equilibrium distributions are the maximizers of the constraint–volume entropy given the set of surviving macroscopic constraints.

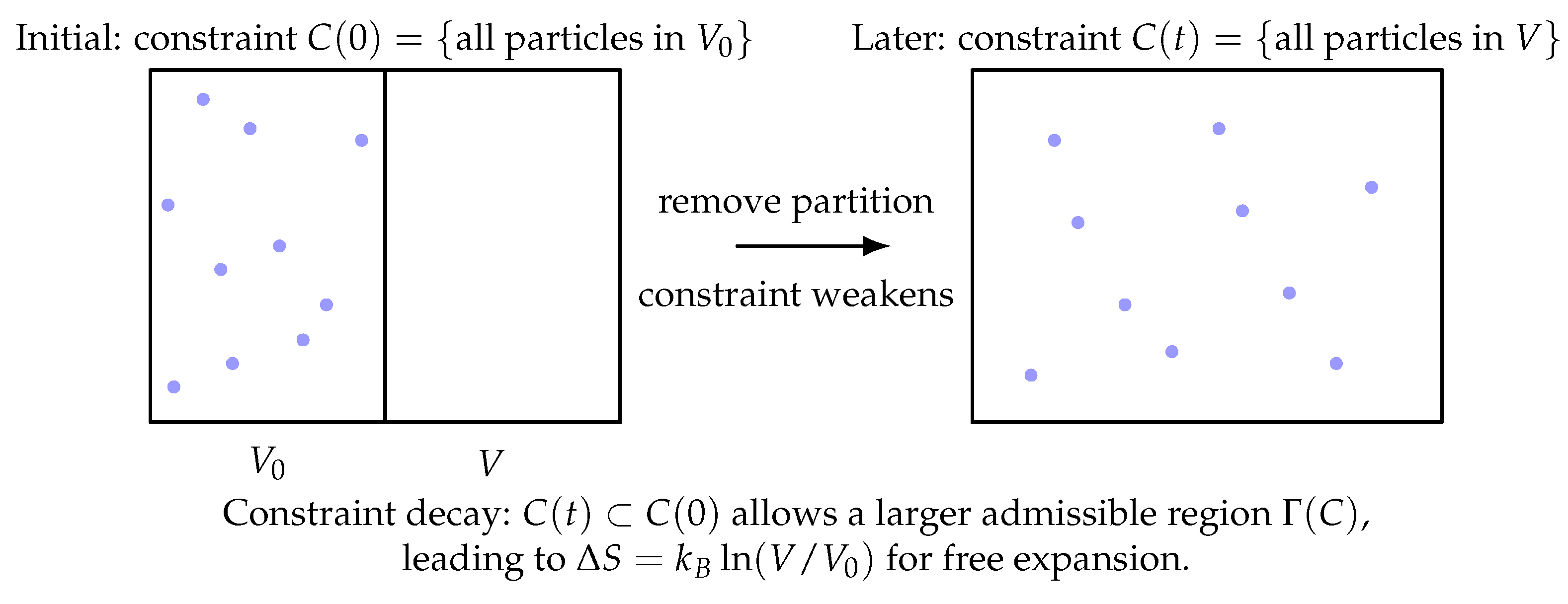

6.4. Gas Expansion: Constraint Decay in External DOFs

A simple and illustrative example is the free expansion of a dilute gas initially confined to a subvolume

of a larger container of volume

. Let

encode the spatial constraint that all particles are located within

:

At early times the constraint is strong, and

is a small subset of the full phase space.

When the partition is removed, microscopic collisions and ballistic motion rapidly weaken the spatial constraint. After a characteristic diffusion time, the constraint set reduces to

and

is now the full microcanonical shell on the larger volume.

Because

the constraint–volume entropy increases by

the standard textbook result.

This example illustrates how classical thermodynamic irreversibility arises from the decay of spatial external constraints due to microscopic local interactions.

6.5. Hydrodynamic Relaxation and Constraint Decay

Nonequilibrium macroscopic fields such as density

and velocity

impose constraints on microscopic configurations:

Transport processes, mixing, and viscosity degrade these constraints, driving and toward homogeneous equilibrium values.

Hydrodynamically, this corresponds to the Navier–Stokes or diffusion equations, which monotonically reduce spatial gradients [

21]. In the constraint–volume picture, this reduction corresponds to

and thus

Hydrodynamics therefore arises as the macroscopic manifestation of constraint decay in external degrees of freedom. Entropy increase in fluids, plasmas, and gases is the direct structural consequence of this decay.

A detailed analysis of hydrodynamic and mixing timescales appears in Appendix E.

6.6. Summary

Classical thermodynamics emerges naturally from the constraint–volume framework when internal coherence constraints have decayed and only macroscopic external constraints remain. In this limit the constraint–volume entropy reduces to the Boltzmann entropy, and equilibrium ensembles arise as maximizers of the entropy subject to the surviving external constraints. Hydrodynamic relaxation and macroscopic irreversibility correspond directly to the decay of external constraints under local microscopic dynamics. See

Figure 5.

7. Quantum Entropy, Decoherence, and Internal DOFs

Quantum systems possess internal degrees of freedom—coherence phases, entanglement patterns, stabilizer relations, operator expectations, and subsystem correlations—that define global constraints on the quantum state [

9]. In contrast to macroscopic spatial constraints, internal quantum constraints are highly fragile: they are rapidly degraded by environment coupling and decoherence [

11,

26], entanglement scrambling [

12,

13], and generic unitary dynamics in non-integrable many-body systems [

27,

28]. In this section we show how quantum entropy increase emerges directly from the weakening of these internal constraints.

We also show that subsystem entropy—including the von Neumann and entanglement entropies—arises as a

special case of constraint–volume entropy. Appendix C discusses the von Neumann case in detail [

29,

30].

7.1. Quantum Constraints and Admissible States

Let

X be the space of quantum states of a system, typically represented by density matrices

on a Hilbert space

[

9,

31]. A quantum constraint is any algebraic or geometric relation on

that restricts the allowed set of states. Examples include:

fixed expectation values: ,

fixed reduced states: ,

purity or rank constraints: ,

coherence constraints: fixed off-diagonal elements,

entanglement constraints: fixed Schmidt spectra or stabilizers [

3].

Given a constraint set

C, the admissible quantum states are

When internal constraints decay, enlarges and the constraint–volume entropy increases.

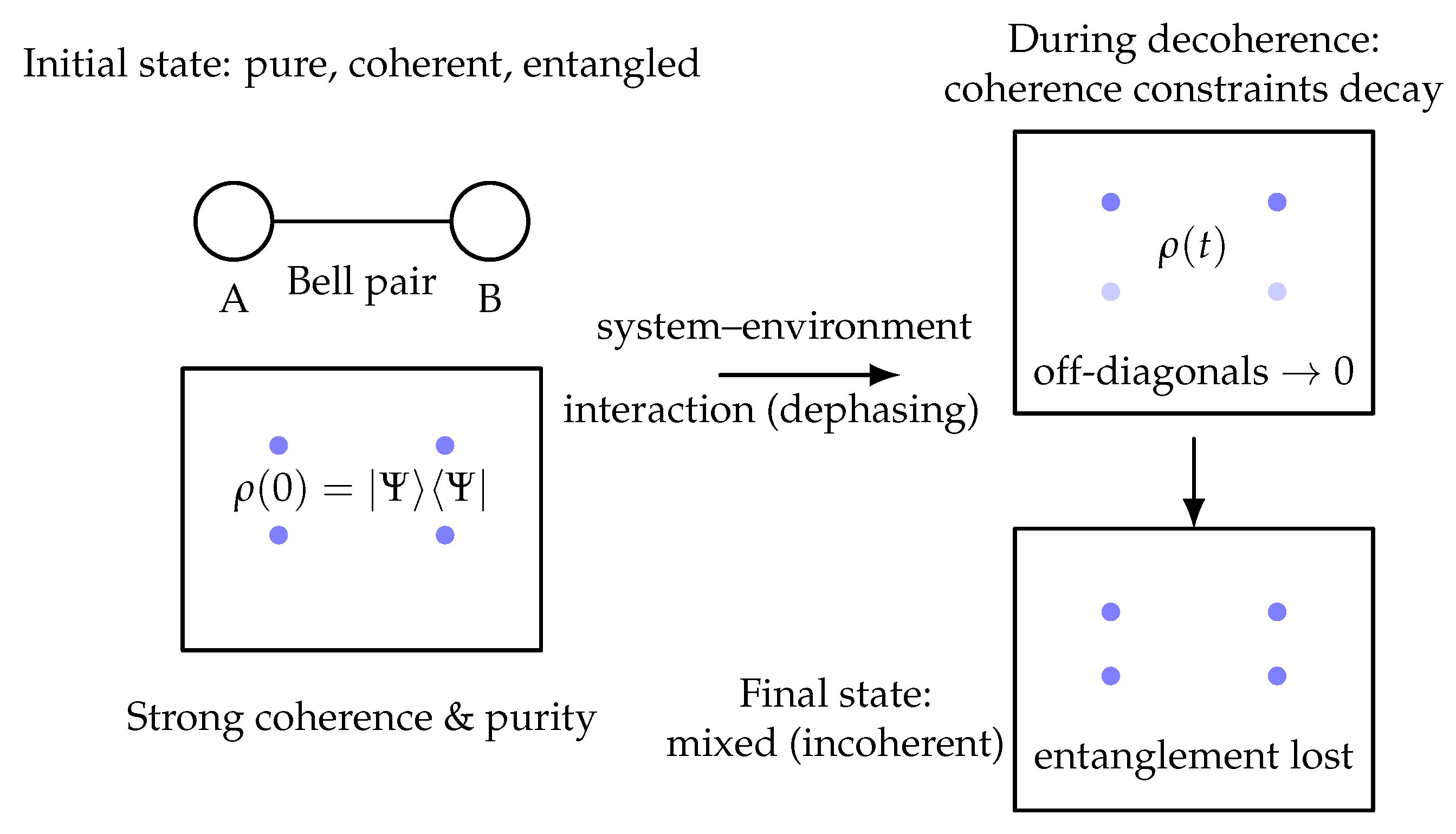

7.2. Decoherence as Constraint Decay

Decoherence is the process by which off-diagonal elements of the density matrix in a preferred basis are suppressed by coupling to an environment, a mechanism extensively analyzed in [

11,

26,

32]. This corresponds to removing phase-coherence constraints.

Let

denote the constraints enforcing fixed coherence phases between basis states. Before decoherence,

After system–environment interaction erodes these phases [

11,

32],

so

and therefore

This increase in entropy corresponds exactly to the physical loss of interference terms, the process by which classicality emerges from quantum mechanics [

11,

26].

7.3. Entanglement Scrambling and Subsystem Entropy

Entanglement scrambling refers to the spread of initially localized quantum correlations throughout the system under generic many-body unitary dynamics. This phenomenon underlies quantum thermalization through ETH [

12,

13,

28].

Let

denote constraints fixing the reduced density matrix of a subsystem

A:

These constraints specify which global states remain compatible with a fixed set of subsystem correlations.

Under generic non-integrable evolution [

12,

13,

27],

because entanglement with

B changes

. Thus

grows and the constraint–volume entropy increases.

When

fixes subsystem purity or specific Schmidt coefficients, scrambling drives

toward the thermal or Page-typical state, increasing the subsystem entropy [

3]. Hence the usual growth of von Neumann entropy is a manifestation of the general structural theorem.

For decoherence and scrambling timescales, see Appendix E [

11,

28].

7.4. Loss of Purity as Constraint Removal

Pure states satisfy the stringent algebraic constraint

which restricts the state space to a measure-zero manifold of density matrices [

9,

33]. Under decoherence or system–environment coupling [

11,

32], the state becomes mixed:

and the purity constraint is removed:

This dramatically enlarges the admissible microstate set, because mixed states occupy exponentially larger volumes in the space of density operators [

29].

Thus the transition from pure to mixed states, often described as loss of information, is precisely a weakening of algebraic constraints.

7.5. Subsystem Entropy as Constraint–Volume Entropy

Consider a bipartite system

with Hilbert space

. Fixing

imposes the global constraint set

The admissible global states form the fiber

The geometry and induced measures of these fibers are well understood [

29,

30,

34]. Their volumes scale as

where

is the von Neumann entropy. Thus:

Subsystem (entanglement) entropy is exactly the constraint–volume entropy associated with fixing the reduced state.

This unifies quantum entanglement entropy with classical entropy within a single geometric definition.

7.6. Two-Qubit Example

To illustrate, consider two qubits in the maximally entangled Bell state. The global state is pure, and the reduced states have maximal entropy [

3]. Environmental dephasing [

32] destroys coherence, removing those internal constraints. Purity is lost, and the admissible microstate region expands. The subsystem entropies then evolve consistently with standard open-system dynamics [

11,

26,

32].

7.7. Summary

Quantum entropy increase—including decoherence, loss of purity, growth of subsystem entropy, and entanglement decay—arises from the decay of internal global constraints. Thus quantum entropy fits seamlessly into the constraint–volume framework, and the structural Second Law applies equally to quantum and classical systems.

8. Examples of Constraint Decay

The general mechanism of entropy increase established above is the weakening of global constraints under local physical dynamics. In this section we illustrate the framework with several canonical examples spanning quantum, classical, and gravitational systems. Each example demonstrates the same pattern:

- (1)

Identify the initial global constraints .

- (2)

Identify the physical mechanism that weakens them.

- (3)

Show how the admissible microstate space expands.

- (4)

Conclude that the constraint–volume entropy increases.

These examples jointly demonstrate that the constraint–decay mechanism is not limited to any specific domain of physics, but is a universal structural feature of dynamical systems with local interactions.

8.1. Example 1: Two-Qubit Entanglement Decay

Consider two qubits

A and

B initially prepared in the Bell state

a standard maximally entangled state. At

, the constraint set includes:

pure-state constraint: ,

coherence constraint: fixed relative phase between 00 and 11,

entanglement constraint: fixed Schmidt spectrum,

subsystem constraint: .

Let qubit B undergo dephasing through a channel , a standard CPTP map generated by phase damping. This removes phase coherence and breaks the entanglement structure.

As coherence constraints and purity constraints weaken, the constraint–volume entropy increases monotonically.

8.2. Example 2: Mixing gas in a Box

Consider a gas initially confined to the left half of a box. At time , the global constraints include:

spatial constraint: all particle positions lie in ,

macroscopic density gradient: fixed density distribution,

momentum-position correlations induced by the confinement.

A small aperture is opened at , and the particles disperse.

Collisions and free streaming break the spatial constraint, dilute the density gradient, and destroy the correlations characteristic of confinement.

The admissible microstate set expands from

to

The Boltzmann entropy increase

for this process is therefore a direct special case of the constraint–volume formulation [

19].

8.3. Example 3: Melting Crystal (Internal + External Constraint Loss)

A crystal at temperature possesses both:

external constraints: periodic atomic positions forming a lattice with long-range order,

internal constraints: quantized vibrational normal modes (phonons) with fixed coherence and phase relations.

As the temperature increases toward the melting point, two forms of constraint decay occur:

(1) External constraint decay.

Atomic positions deviate from lattice points, long-range correlations break down, and the subset of microstates satisfying lattice periodicity shrinks dramatically.

(2) Internal constraint decay.

Phonon modes lose coherent phase relations through anharmonic scattering and phonon–phonon interactions, weakening the internal mode constraints.

When melting completes, the crystal structure is completely lost:

and the admissible microstate volume increases from the measure-zero set of ordered configurations to the astronomically larger liquid-phase configuration space.

This example illustrates the simultaneous decay of internal and external constraints.

8.4. Example 4: Turbulent Relaxation

Consider an initially laminar fluid flow with a highly organized velocity field. The initial constraints include:

global velocity–gradient relations,

coherent vortex alignment,

stable macroscopic invariants (e.g. large-scale helicity),

absence of fine-scale vorticity structure.

As the Reynolds number increases, the flow becomes turbulent. Energy cascades from large to small scales, and vorticity twisting, stretching, and reconnection destroy the global coherence relations.

Thus the constraint set weakens:

The flow becomes compatible with a vastly larger set of velocity fields, especially those with fine-scale structure. The constraint–volume entropy grows monotonically until the flow reaches a statistically steady turbulent state.

This example shows that external continuum-field constraints obey the same structural monotonicity as discrete quantum constraints.

8.5. Example 5: Black Hole Entropy as Horizon Constraints

For a black hole of horizon area

A, the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy

quantifies the number of microstates compatible with the existence of a smooth event horizon of area

A [

4].

In the constraint–volume framework:

Horizon constraint.

The horizon imposes a global geometric constraint:

consistent with the covariant treatment of black hole thermodynamics [

35].

Constraint weakening through Hawking radiation.

As Hawking radiation reduces the horizon area,

Thus the microstate volume increases:

and the entropy grows accordingly.

Interpretation.

This connects black hole entropy directly to the constraint–volume formalism: the horizon enforces a global geometric relation whose weakening under Hawking emission enlarges the admissible solution space. Hence black hole thermodynamics is aligned with the same structural mechanism underlying all other entropy increases.

Summary

Each example—quantum decoherence, gas mixing, melting crystals, turbulent flows, and black hole evaporation—demonstrates the same pattern:

This unified explanation reveals constraint decay as the structural foundation of the Second Law across all physical regimes.

9. Exceptions: Integrability and Constraint Preservation

The structural Second Law established earlier shows that entropy increases whenever global constraints decay under local dynamics. However, certain special classes of physical systems preserve large sets of global constraints indefinitely. These systems do not violate the Second Law; rather, they realize the equality case of the Constraint Monotonicity Theorem:

In this section we identify the principal categories of such systems, clarify the sense in which they preserve constraints, and explain why their exceptional behavior does not contradict the general constraint–decay mechanism.

9.1. Integrable Hamiltonians

A classical or quantum Hamiltonian system is

integrable if it possesses a complete set of independent conserved quantities

in involution, with

N equal to the number of degrees of freedom, as in the Liouville–Arnold theorem [

36]. In quantum integrability, these conserved quantities may arise from commuting transfer matrices or Lax pairs [

37].

These integrals of motion form a global constraint set,

whose defining relations are preserved exactly under the dynamics:

Thus the accessible region of phase space or state space is confined to an invariant torus or conserved manifold, and the constraint–volume entropy remains constant:

Interpretation.

Integrable systems lie precisely on the entropy-conserving boundary of the structural Second Law. Entropy does not increase because no global constraints decay. Thus integrability is not a violation of the Second Law, but a special degenerate case where constraints are preserved by symmetry rather than destroyed by generic interactions.

The precise conditions for constraint preservation in integrable systems are developed in Appendix F.3 and parallel the derivations of invariant tori in classical integrability [

38].

9.2. Many-Body Localization (MBL)

Many-body localized systems preserve an extensive set of emergent quasi-local integrals of motion (“

ℓ-bits”) [

39,

40]. Let

denote these integrals. An MBL Hamiltonian satisfies

for all sites

i, providing a large and stable constraint set,

These constraints prevent the system from thermalizing or scrambling, consistent with the original Basko–Aleiner–Altshuler formulation of MBL [

41]. Thus for all

t,

and because the constraints are unchanged, the constraint–volume entropy is constant:

Interpretation.

Many-body localization is an instance where internal global constraints are maintained by disorder-induced emergent symmetries. MBL systems are therefore entropy-stable rather than entropy-increasing, but this behavior is fully consistent with the monotonicity theorem.

9.3. Topological Phases and Stabilizer Codes

Topological phases of matter [

42] and quantum error–correcting stabilizer codes [

43] provide another family of systems where global constraints are protected, but for different reasons: they arise from topological, nonlocal orders rather than integrability.

Let the stabilizers

define the code space or ground-state manifold, as in the toric code [

44]. These impose the constraints

As long as the system remains below a threshold of thermal or environmental noise, these constraints are preserved:

Thus the admissible microstate space remains fixed and entropy does not increase:

Interpretation.

Topological constraints are stable because local perturbations cannot change the global topological sector. Hence these phases again realize the equality case of the structural Second Law.

9.4. Why These Exceptions Do Not Violate the Second Law

The Constraint Monotonicity Theorem states:

It does not assert that must happen for all systems. Instead, the theorem identifies entropy increase with constraint decay.

The exceptions are systems where is invariant.

Integrable, MBL, and topologically ordered systems preserve because:

integrable systems have symmetries preventing constraint decay,

MBL systems have emergent local integrals of motion resisting scrambling,

topological phases protect global information from local noise.

Thus these systems do not satisfy the hypothesis of constraint weakening, and they naturally realize the boundary case of

The Second Law applies generically, not universally.

Entropy increase is a

generic feature of local interacting systems with no protecting symmetries or disorder-induced integral structures. These exceptional systems are measure-zero in Hamiltonian or Liouvillian parameter space [

45]. Any perturbation breaking the special structure will cause

to decay and entropy to begin increasing.

9.5. Summary

Integrable dynamics, many-body localization, and topological stabilizer structures do not violate the Second Law in the constraint–volume picture. They represent special situations in which:

so the admissible microstate set does not expand and entropy remains constant. These cases lie exactly on the equality boundary of the structural Second Law. In all generic systems without symmetry protection or disorder-stabilized integrals of motion, local interactions necessarily degrade global constraints, and entropy increases.

10. Time Is Not Entropy

Entropy and time are often conflated in informal discussions of the Second Law. Because entropy tends to increase in closed macroscopic systems, it is sometimes suggested that entropy

is time, or that the growth of entropy defines the direction or flow of time [

46]. In the constraint–volume framework, this identification is neither necessary nor accurate. Time and entropy play fundamentally different roles:

This section clarifies the distinction and shows why the Second Law should be understood as a structural statement about constraint decay, not as an identity between time and entropy.

10.1. Time as a Parameter of Dynamical Evolution

In both classical and quantum mechanics, time enters as a parameter in the dynamical equations:

Classical phase-space trajectories

satisfy Hamilton’s equations

preserving Liouville measure on phase space [

38].

Quantum states

or

evolve unitarily according to

again preserving the inner-product structure and measure on state space [

9].

In both cases, the microscopic dynamics are time-reversal invariant: for each trajectory or state , there exists a reversed trajectory or time-reversed state that is equally allowed by the equations of motion. Nothing in these equations requires entropy to increase or to play any distinguished role in defining time.

10.2. Entropy as a Functional of Constraints

Entropy in this framework is defined by

where

C is the current global constraint set and

is the corresponding admissible microstate space.

Crucially:

S is a function of the constraint structure, not of time directly,

Time enters only through the time-dependence of ,

If

is constant in time, then

is constant, regardless of how time evolves [

47].

Thus, time and entropy are conceptually orthogonal: time orders states, while entropy measures the size of the set of states compatible with the constraints those states satisfy.

10.3. Microscopic Reversibility and Macroscopic Irreversibility

The Constraint Monotonicity Theorem states that entropy increases when the constraint set weakens:

This is a one-way implication: it does not assert that such weakening must occur along every trajectory.

Microscopic reversibility remains intact:

For any forward-time evolution from

to

there exists a time-reversed evolution from

back to

allowed by the microscopic equations [

1].

Along the reversed evolution, the constraint set may

strengthen:

leading to a decrease in entropy along that trajectory.

The fact that such entropy-decreasing trajectories exist is the content of Loschmidt-type objections to the Second Law [

48,

49]. In the constraint–volume framework, these trajectories correspond to fine-tuned evolutions in which global constraints are restored rather than degraded.

Macroscopic irreversibility is explained not by a fundamental asymmetry in the dynamical laws, but by the statistical unlikelihood of such fine-tuned trajectories [

50]. For generic initial conditions evolving under local dynamics, global constraints monotonically decay, and entropy increases.

10.4. Entropy Under Time Reversal

Consider a forward evolution from time

to

:

By the monotonicity theorem, .

Now consider the time-reversed evolution, starting from the microstate at

and running backwards to time

. From the point of view of the reversed dynamics, the constraint set typically

strengthens:

and the entropy decreases along this reversed trajectory.

Thus entropy can increase or decrease under time reversal, depending on the direction in which we follow the trajectory. This confirms that entropy does not define time; rather, it is a directional property of certain physically realized evolutions [

46].

Appendix F.4 provides the derivation showing how entropy production arises despite reversible microscopic dynamics.

10.5. Low-Entropy Past and the Arrow of Time

The empirical fact that entropy has been increasing over cosmological and laboratory timescales reflects a contingent boundary condition: the early Universe and the initial states of laboratory systems began in configurations with highly restrictive global constraints and therefore low entropy [

50].

Given such low-entropy initial conditions, generic local dynamics will monotonically weaken global constraints and increase entropy. This defines a thermodynamic arrow of time relative to the chosen initial conditions, not an intrinsic identity between entropy and time.

In the constraint–volume framework, the arrow of time emerges from:

- (1)

an initial constraint set that is unusually strong (small ),

- (2)

generic local dynamics that weaken for ,

- (3)

the structural monotonicity .

Time itself, however, is simply the parameter t labeling the dynamical evolution; it has no entropy content.

10.6. Clarifying the Distinction with Examples

Spin-echo experiments.

In spin-echo protocols, an initially ordered spin configuration dephases (constraints decay, entropy increases) and then rephases under a carefully engineered pulse sequence [

51]. Time runs forward throughout; entropy first rises, then falls. This shows explicitly that entropy is not identical to time.

Gas compression by external work.

A gas that has spread through a box (high entropy) can be quasi-statically compressed back into a smaller volume by external work, restoring constraints on spatial localization. Entropy decreases in this process, even though time flows forward [

8].

Fine-tuned microscopic reversal.

In principle, if all particle velocities in a gas were exactly reversed, the gas would spontaneously recontract and recover its initial constraint structure, reducing entropy [

48]. Such trajectories exist but are fantastically improbable.

In all these examples, time evolves uniformly, while entropy may increase, remain constant, or decrease, depending on whether constraints are weakened, preserved, or restored.

10.7. Summary

Time and entropy are fundamentally distinct concepts:

The Second Law, in its structural form, states that entropy increases when global constraints decay under generic local dynamics. This explains the observed thermodynamic arrow of time as a consequence of low-entropy initial conditions and typical dynamical behavior, not as an identity between time and entropy. Entropy is not time; it is a structural measure of constraint loss.

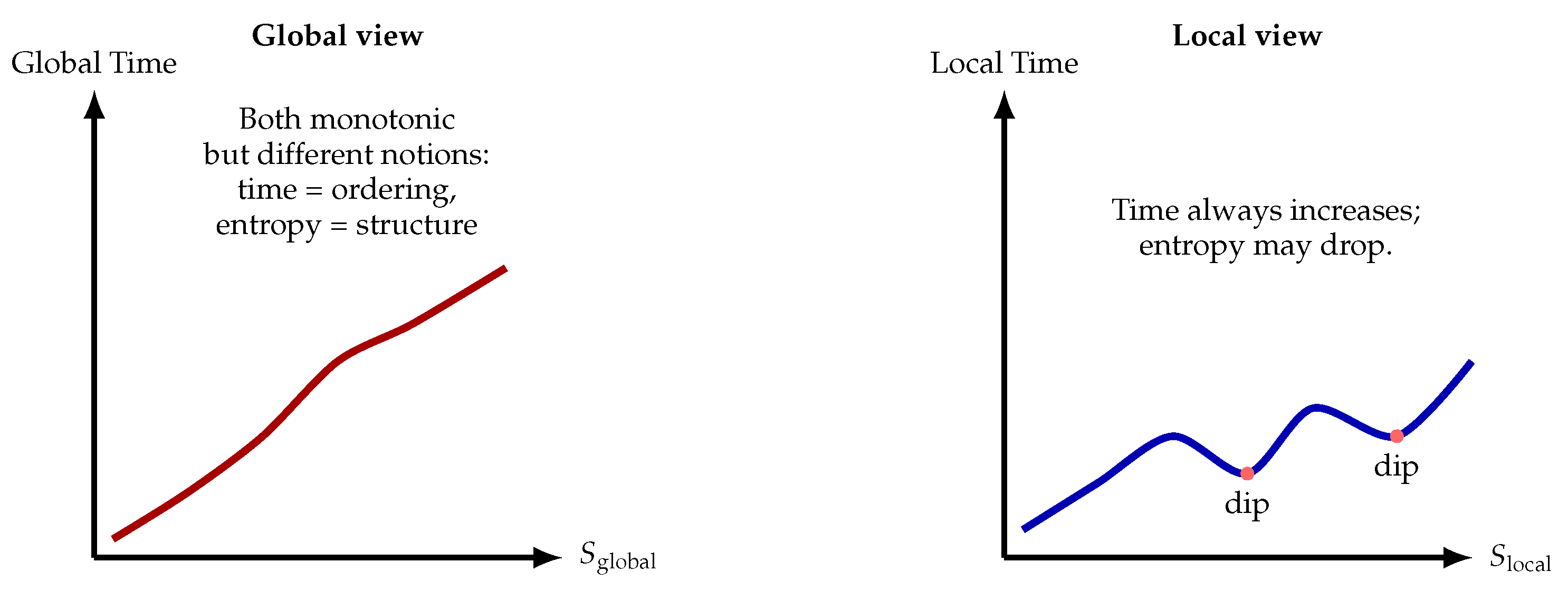

Figure 7.

Time is not entropy. Left: Globally, both time and entropy appear monotonic, but this does not imply identity: time is a relational ordering, while entropy measures the number of microstates compatible with global constraints. Right: Locally the distinction is explicit: entropy may rise or fall, while time always advances. Thus correlation does not imply equivalence.

Figure 7.

Time is not entropy. Left: Globally, both time and entropy appear monotonic, but this does not imply identity: time is a relational ordering, while entropy measures the number of microstates compatible with global constraints. Right: Locally the distinction is explicit: entropy may rise or fall, while time always advances. Thus correlation does not imply equivalence.

11. Discussion

The constraint–volume formulation developed in this work provides a unified and conceptually clean foundation for entropy across classical, quantum, and gravitational settings. Similar unifying ambitions appear in earlier approaches to statistical mechanics and thermodynamics [

8,

10,

50,

52], but the present framework derives these notions structurally from constraint geometry itself. In this section we discuss the broader implications of the framework, clarify its relationship to existing notions of entropy, and show how it resolves several long-standing conceptual puzzles in thermodynamics, quantum information, and statistical mechanics.

11.1. Entropy as a Structural Property of Constraints

In traditional treatments, entropy is variously interpreted as:

a measure of missing information (Shannon) [

2],

a counting of microstates consistent with macroscopic data (Boltzmann) [

52],

the expectation value of

(von Neumann) [

20],

a subjective Bayesian value (Jaynes) [

10],

a manifestation of decoherence or entanglement structure [

11].

These characterizations differ significantly in meaning and domain of applicability, contributing to persistent confusion about what entropy actually

is. In this work we have shown that all these notions arise as special cases of a single structural quantity:

where

C is the set of global physical constraints currently satisfied by the system. Entropy is thus an objective, physically grounded measure of the “size” of the admissible microstate space compatible with the system’s global relations.

This resolves longstanding debates about whether entropy is subjective, informational, or statistical [

7]. Entropy in this formulation is purely structural: it depends only on the physical constraints that define the system, not on epistemic ignorance or coarse-graining conventions.

11.2. Relation to Jaynes and Maximum Entropy

Jaynes’ maximum-entropy principle posits that one should assign the probability distribution over microstates that maximizes Shannon entropy subject to known macroscopic constraints [

10]. In our framework, Jaynes’ principle emerges naturally once one identifies

C with the set of known global constraints:

Maximizing the Shannon or von Neumann entropy over this admissible set is equivalent to identifying a representative state that reflects the loss of all other constraints. Thus Jaynes’ variational principle is recovered as the operational rule for selecting a state when C is partially known.

However, the constraint–volume entropy itself is more fundamental: it measures the actual structural freedom of the system, regardless of what an observer knows.

11.3. Relation to Shannon and von Neumann Entropy

Shannon and von Neumann entropies arise from internal degrees of freedom and reflect the decay of internal algebraic constraints such as:

In the constraint–volume framework:

Thus both appear as special cases of when C fixes probability distributions or density matrices.

11.4. Relation to Decoherence and Emergent Classicality

Decoherence theory explains how quantum systems lose internal phase relations and acquire classical-like behavior via entanglement with their environments [

11]. In our formulation, decoherence corresponds to a strict weakening of internal constraints:

as coherence relations and entanglement structures degrade. Thus the growth of subsystem entropy in decoherence is a direct instance of the structural Second Law.

The constraint–volume framework also clarifies the emergence of classical ensembles: they arise when internal quantum constraints have decayed sufficiently that only external macroscopic constraints remain, so the admissible states reduce to classical statistical distributions.

11.5. Relation to Eigenstate Thermalization (ETH)

The Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis states that generic, non-integrable quantum systems effectively “self-thermalize” because individual eigenstates already encode thermal correlation functions [

12,

13,

27]. In the constraint–volume picture, ETH corresponds to:

Generic Hamiltonians degrade internal correlation constraints via unitary scrambling.

The constraint set becomes dominated by only a few macroscopic conserved quantities (energy, particle number).

The admissible microstate set becomes essentially the microcanonical shell.

Thus ETH is the dynamical mechanism by which constraint decay removes all fine-grained structure, leaving only robust global conservation laws.

11.6. A Unified Foundation for Entropy

The structural constraint–volume formulation unifies:

classical thermodynamic entropy,

quantum entropy and entanglement entropy,

decoherence-induced entropy growth,

statistical entropy in probability theory,

black hole entropy (as horizon-area constraints) [

4,

5],

hydrodynamic entropy in continuum systems.

All are examples of the same principle:

This eliminates the need for multiple entropy definitions across physics.

11.7. Resolution of Long-Standing Conceptual Puzzles

This framework dissolves several persistent puzzles:

(1) Why does entropy increase if microscopic laws are reversible?

Because microscopic reversibility only implies that constraint-restoring trajectories exist, not that they are dynamically typical [

49]. Generic interactions destroy global constraints; restoring them requires fine-tuning.

(2) Is coarse-graining essential?

No. Coarse-graining is epistemic [

10]; constraint decay is physical and structural.

(3) What is the role of information?

Informational interpretations follow when

C encodes informational constraints; in general, entropy is objective [

7].

(4) Why do classical thermodynamic and quantum entanglement entropies share a form?

Because both quantify constraint loss in their respective state spaces.

(5) How does the arrow of time arise?

From low-entropy initial conditions [

50] and the generic decay of global constraints—not from entropy defining time.

11.8. Uniqueness of the Constraint–Volume Framework

The present formulation raises a natural question: could there exist other equally general and physically meaningful definitions of entropy? Many well-established notions of entropy have been proposed—including the Shannon and Gibbs–Shannon entropies [

2,

10], the von Neumann entropy [

20], coarse-grained Boltzmann entropy [

1], entanglement entropy in quantum many-body systems [

3], and geometric or gravitational entropies such as the Bekenstein–Hawking formula [

4,

5]. Each is mathematically precise within its domain, yet none provides a single structural principle that applies uniformly across classical, quantum, and gravitational regimes.

A genuinely unified entropy must satisfy several criteria: (i) applicability to classical and quantum systems, including continuous or infinite-dimensional state spaces; (ii) invariance under the natural symmetries of the theory (Liouville invariance [

18] in classical mechanics, unitary invariance [

9] in quantum mechanics); (iii) recovery of standard thermodynamic, information-theoretic, and quantum entanglement entropies; (iv) compatibility with reversible microscopic dynamics; and (v) independence from subjective information, coarse-graining prescriptions, or arbitrary subsystem decompositions [

7].

Information-theoretic entropies depend on observer knowledge; coarse-grained formulations require privileged partitions of phase space; entanglement entropies rely on subsystem boundaries and do not apply outside quantum settings; and gravitational or holographic entropies apply only in special spacetime backgrounds. None of these approaches provides the structural generality or dynamical transparency required for a fully universal Second Law.

By contrast, the constraint–volume definition,

is determined solely by the measure-invariant size of the admissible state-space region defined by the system’s surviving global constraints. Constraints are the only structural mechanism that restricts the kinematic state space, and invariant measures are the only coordinate-free way of quantifying the size of such regions. Thus the constraint–volume entropy is, in an essential sense, the

unique structural definition that satisfies all the criteria above. Furthermore, the structural Second Law derived in this paper follows directly from constraint weakening, without invoking coarse-graining, subjective ignorance, or special subsystem choices.

In this sense, while many forms of entropy appear throughout physics, the constraint–volume formulation is not merely one unifying perspective among others: it provides a structurally privileged and essentially unique foundation for all physical notions of entropy, spanning classical mechanics, quantum theory, statistical mechanics, and gravitation.

11.9. Summary

The constraint–volume picture reframes entropy as an objective measure of the size of the microstate space defined by the system’s global constraints. This perspective unifies classical, quantum, and gravitational entropy, while dissolving longstanding interpretive tensions surrounding information, coarse-graining, and irreversibility. By grounding entropy in constraint geometry rather than statistical assumptions, the framework provides a coherent foundation for the Second Law across all scales of physics.

12. Conclusions

In this work we have developed a unified, structural account of entropy based on the geometry of global physical constraints. The idea that constraints define admissible state spaces has deep roots in statistical mechanics [

8,

10], but the present framework elevates this idea to a fully general principle applicable to classical, quantum, and gravitational systems.

Local interactions, whether classical or quantum, generically degrade global constraints: coherent phases decay [

11], correlations scramble [

12,

27], spatial gradients flatten, and geometric relations such as horizon area decrease [

5]. This monotonic weakening of

enlarges the admissible microstate set and yields the structural Second Law:

A key conceptual clarification is that

time is not entropy [

46,

50]. Time parametrizes dynamical evolution; entropy measures the volume of microstates compatible with the system’s surviving constraints. The thermodynamic arrow of time arises from low-entropy initial conditions combined with the generic decay of global constraints, not from any identity between entropy and the temporal parameter.

The framework dissolves classical puzzles associated with irreversibility, coarse-graining, and information, while unifying classical thermodynamic entropy with quantum, statistical, and geometric notions of entropy. It provides a common structural basis for phenomena ranging from decoherence and entanglement growth to hydrodynamic relaxation and black hole thermodynamics.

Future work may explore quantitative rates of constraint decay, open- system generalizations, geometric structures arising in gauge theories, and applications to quantum thermodynamics and quantum error correction [

9].

Overall, the constraint–volume formulation provides a coherent, unifying, and physically grounded understanding of entropy across all regimes of modern physics.

Author Contributions

Bin Li is the sole author

Funding

This research received no external funding

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DOF |

degrees of freedom |

| GGE |

generalized Gibbs ensembles |

| ETH |

Eigenstate Thermalization |

Appendix A. Mathematical Structure of Constraint Sets

This appendix collects the basic structural properties of constraint sets and their associated admissible microstate spaces. The aim is to formalize the set-theoretic and measure-theoretic foundations underlying the main text and to highlight the order structure that ultimately leads to the Constraint Monotonicity Theorem. General background on measurable state spaces may be found in [

25], and the geometry of the quantum state space is well reviewed in [

33].

Appendix A.1. State Space, Constraints, and Admissible Sets

Let X denote the kinematic microstate space of a physical system. Depending on the domain, X may be:

We assume throughout that

is a measurable space with reference measure

(e.g. Liouville measure in classical mechanics [

53] or Hilbert–Schmidt measure in quantum theory [

33]). The induced volume functional is

Definition A1 (Constraint). A constraint is any condition selecting a measurable subset of X. Formally, a constraint c corresponds to a set , and a microstate x satisfies c if and only if .

Examples include:

energy-shell constraints

as in the microcanonical ensemble [

8],

macroscopic constraints defining fixed N or V,

quantum expectation-value constraints ,

subsystem constraints

B familiar in quantum information theory [

9],

coherence constraints fixing selected off-diagonal matrix elements.

Definition A2 (Constraint set and admissible microstates). A

constraint set C is a finite or countable family of constraints

. The corresponding admissible microstates are

The measurability of

is standard and assumed throughout [

8,

33].

Appendix A.2. Order Structure on Constraint Sets

Constraint sets naturally form a partially ordered set under inclusion, a familiar notion from order theory and lattice theory [

54].

Definition A3 (Partial order). For two constraint sets

and

, we write

if every constraint in

is also contained in

.

Lemma A4 (Monotonicity of admissible sets).

If , then

Proof.

Since

, the intersection over the larger set of constraints (

) yields a subset of the intersection over

, a standard property of set intersections [

25]. □

Definition A5 (Entropy as an order-preserving functional). For any constraint set

C whose admissible region satisfies

the constraint–volume entropy is defined as

Lemma A6 (Monotonicity of entropy).

If , then

assuming .

Proof. Immediate from Lemma A4 and monotonicity of measure under inclusion [

25]. □

This result is the static version of the Constraint Monotonicity Theorem used in the main text.

Appendix A.3. Lattice Operations on Constraint Sets

For many applications, it is useful to place constraint sets in a lattice-theoretic framework [

54].

Definition A7 (Meet and join). For constraint sets and , define:

Their admissible microstate sets satisfy:

Such order-reversing relations between constraints and feasible regions are standard in convex analysis and statistical mechanics [

55].

Appendix A.4. Topology and Continuity Considerations

In many cases, constraints depend continuously on parameters. Continuity of admissible regions under such variations can be formalized using the Vietoris topology or via weak convergence of measures [

56]. Under mild regularity conditions, the volume functional

is continuous in the constraint parameters. This justifies treating entropy as a smooth function of macroscopic variables in equilibrium thermodynamics [

57].

Appendix A.5. Summary

The constraint–volume formulation rests on the following structural components:

a measurable state space ,

measurable constraint regions ,

constraint sets C as collections of such constraints,

admissible regions ,

a volume functional inducing .

The partial order on constraint sets induces a reversed order on admissible microstate sets and an order-preserving entropy functional. These elements provide the structural foundation for the Constraint Monotonicity Theorem and the unified Second Law developed in the main text (see also Appendix F for technical proofs).

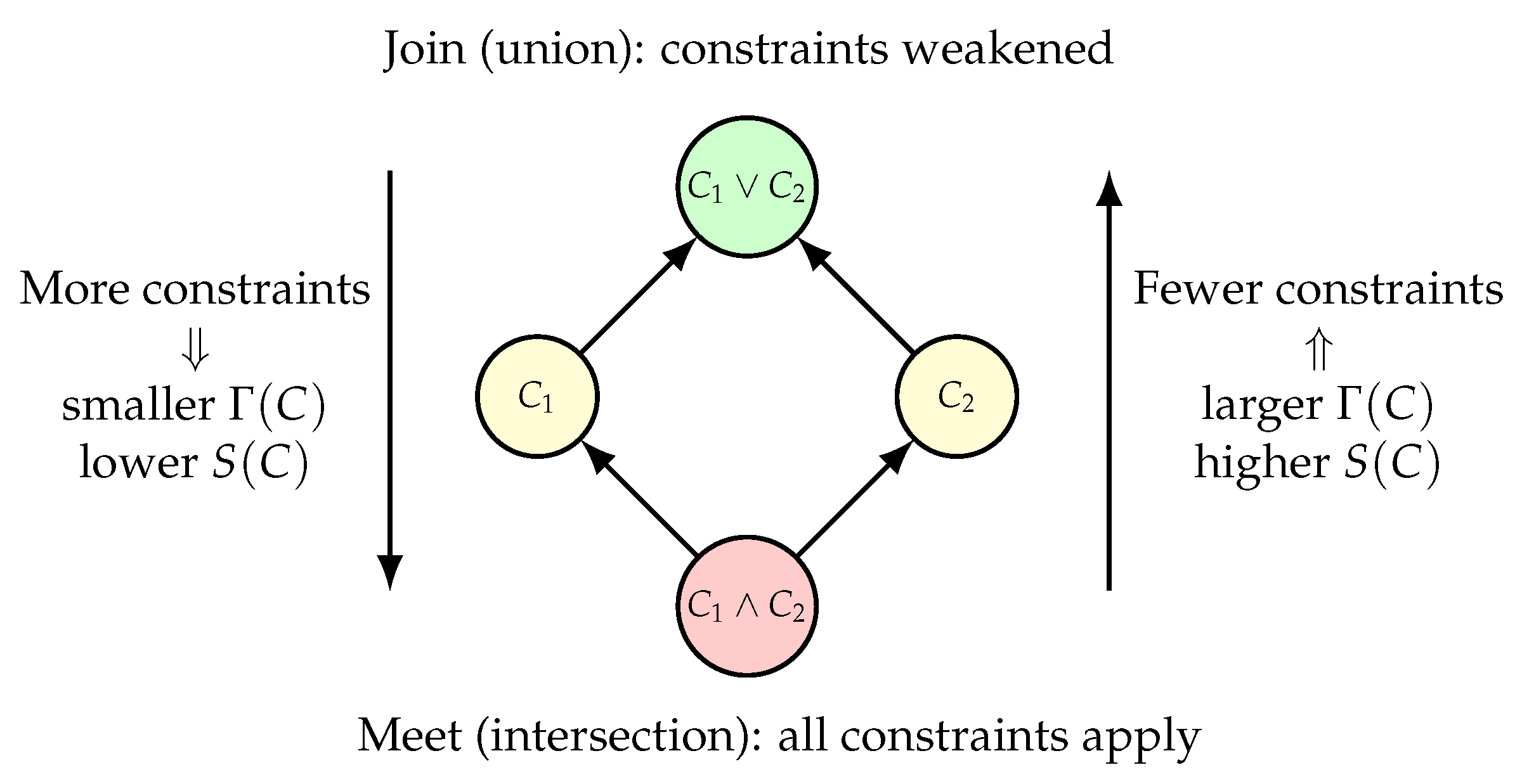

Figure A1 is a schematic illustration of a lattice structure of global constraints.

Figure A1.

Lattice structure of global constraint sets. The set of all constraint sets forms a partially ordered lattice with order relation meaning that contains fewer (weaker) constraints than C. The meet represents the combined constraint set (tighter constraints), while the join represents the weakened set retaining only the constraints common to both. Moving upward in the lattice corresponds to constraint decay, enlargement of the admissible microstate region , and an increase in the constraint–volume entropy .

Figure A1.

Lattice structure of global constraint sets. The set of all constraint sets forms a partially ordered lattice with order relation meaning that contains fewer (weaker) constraints than C. The meet represents the combined constraint set (tighter constraints), while the join represents the weakened set retaining only the constraints common to both. Moving upward in the lattice corresponds to constraint decay, enlargement of the admissible microstate region , and an increase in the constraint–volume entropy .

Appendix B. Integrable Systems and Their Constraint Structure

Integrable systems play a distinguished role in the constraint–volume framework because they saturate the equality case of the Constraint Monotonicity Theorem. They possess extensive families of exactly conserved quantities, so the constraint set

is time-independent and the entropy

remains constant. Classical integrability is developed in standard references such as [

53], and quantum integrability together with generalized Gibbs ensembles (GGE) is extensively reviewed in [

28]. This appendix summarizes both cases in the language of constraint sets.