Submitted:

14 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

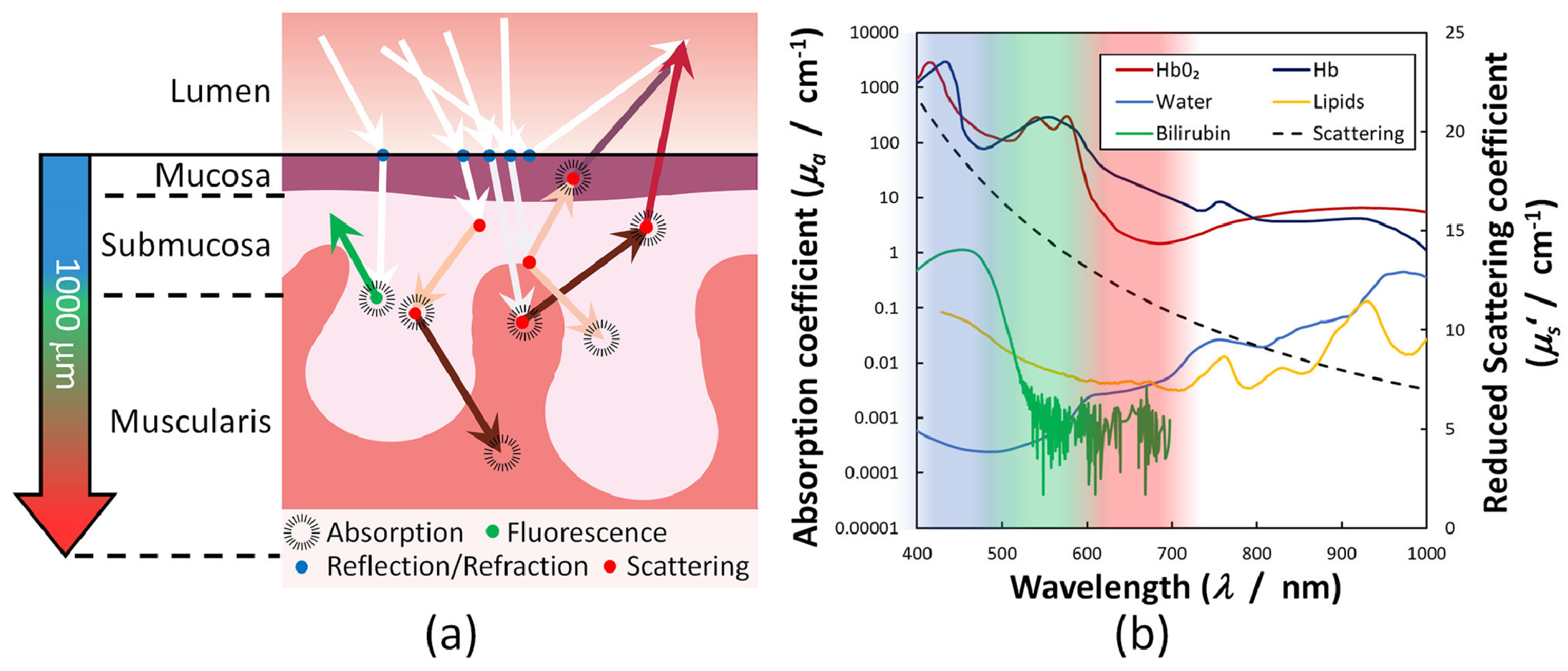

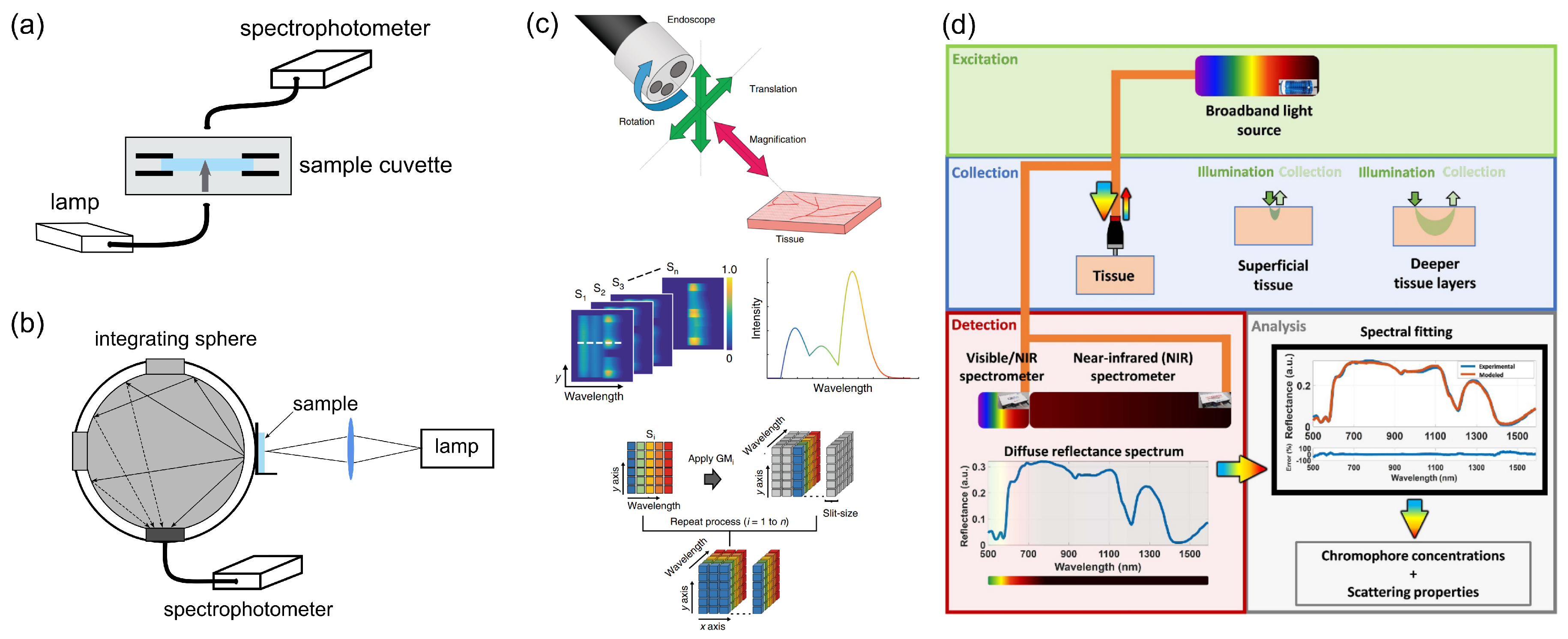

2. Optical Properties of Healthy and Diseased GI Tissues and Detection Methods

3. The Use of Autofluorescence Approaches for the GI Diagnostics

4. Modern GI Histology and Ex Vivo Models

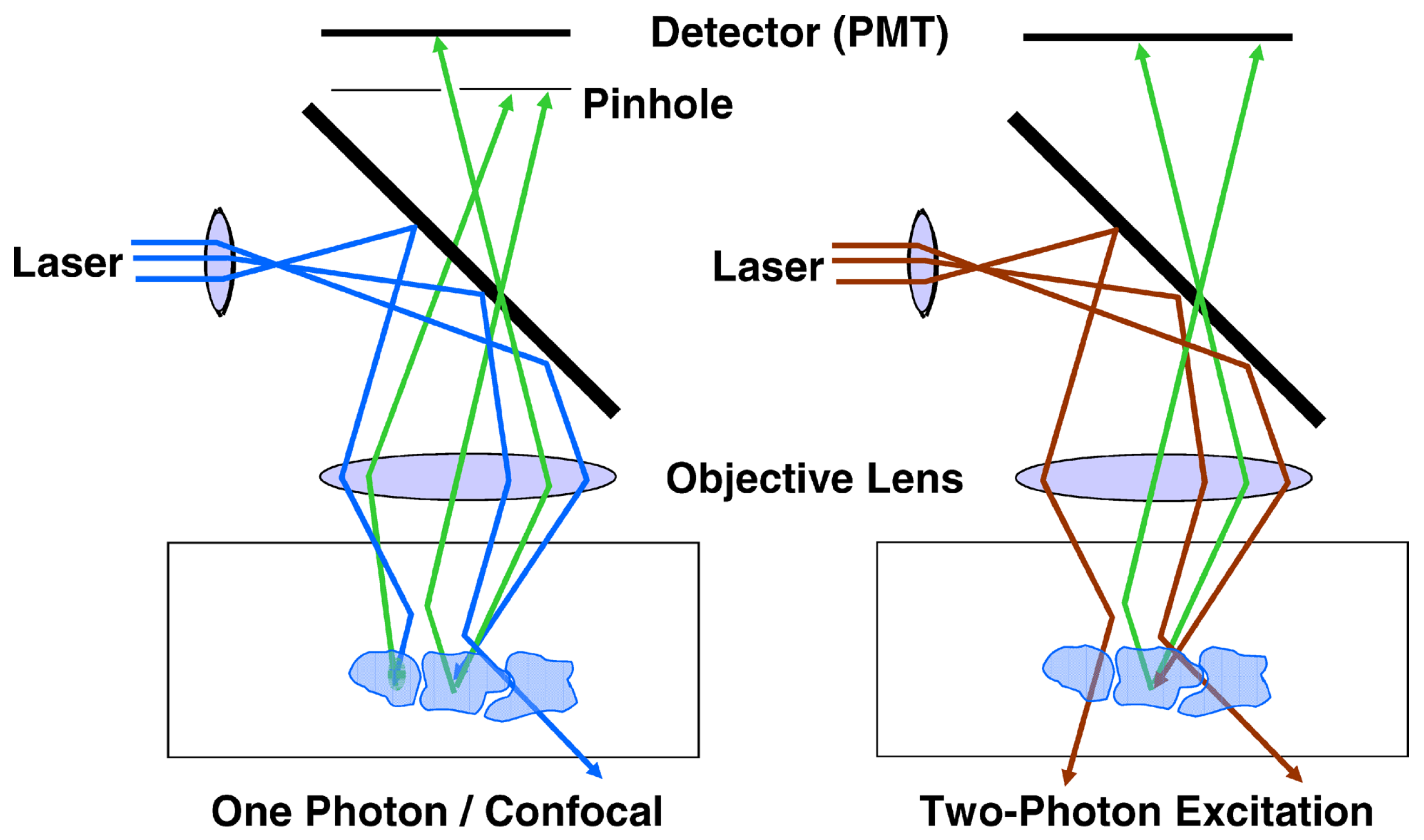

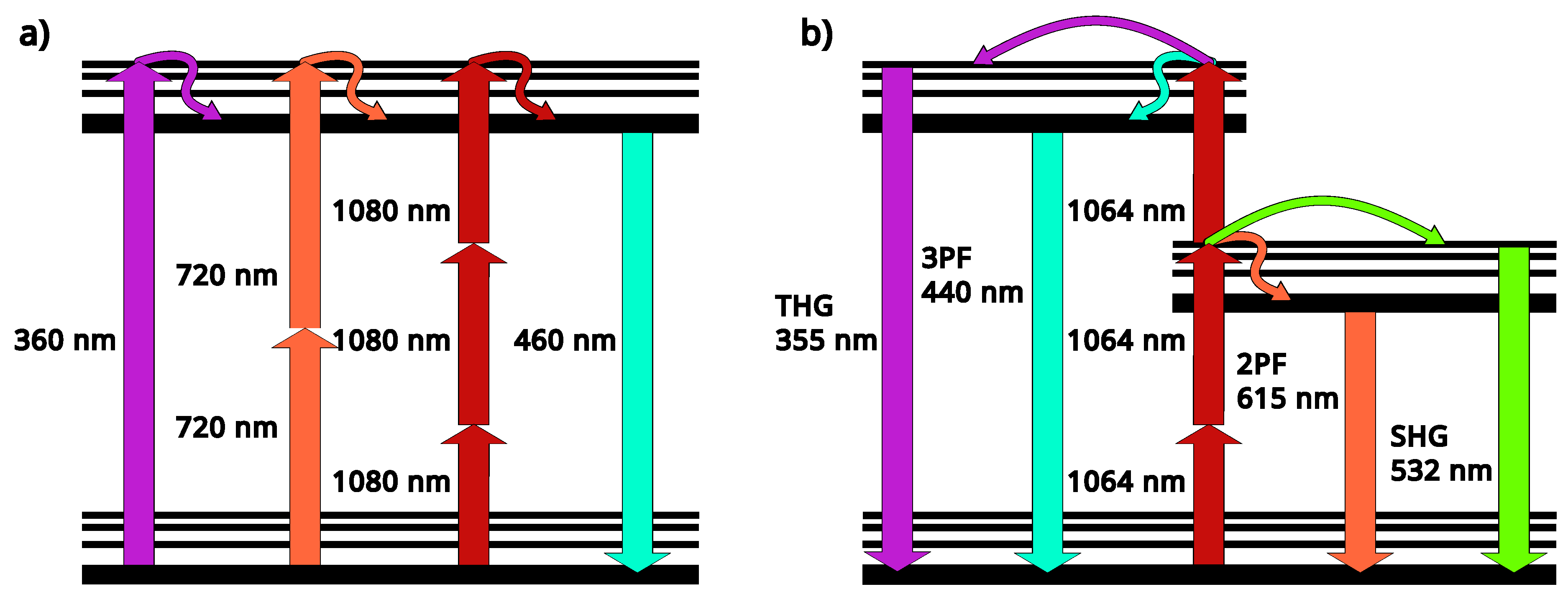

5. Multiphoton Microscopy for In Vivo Imaging

6. Advances and Challenges of Using Optical Fibers

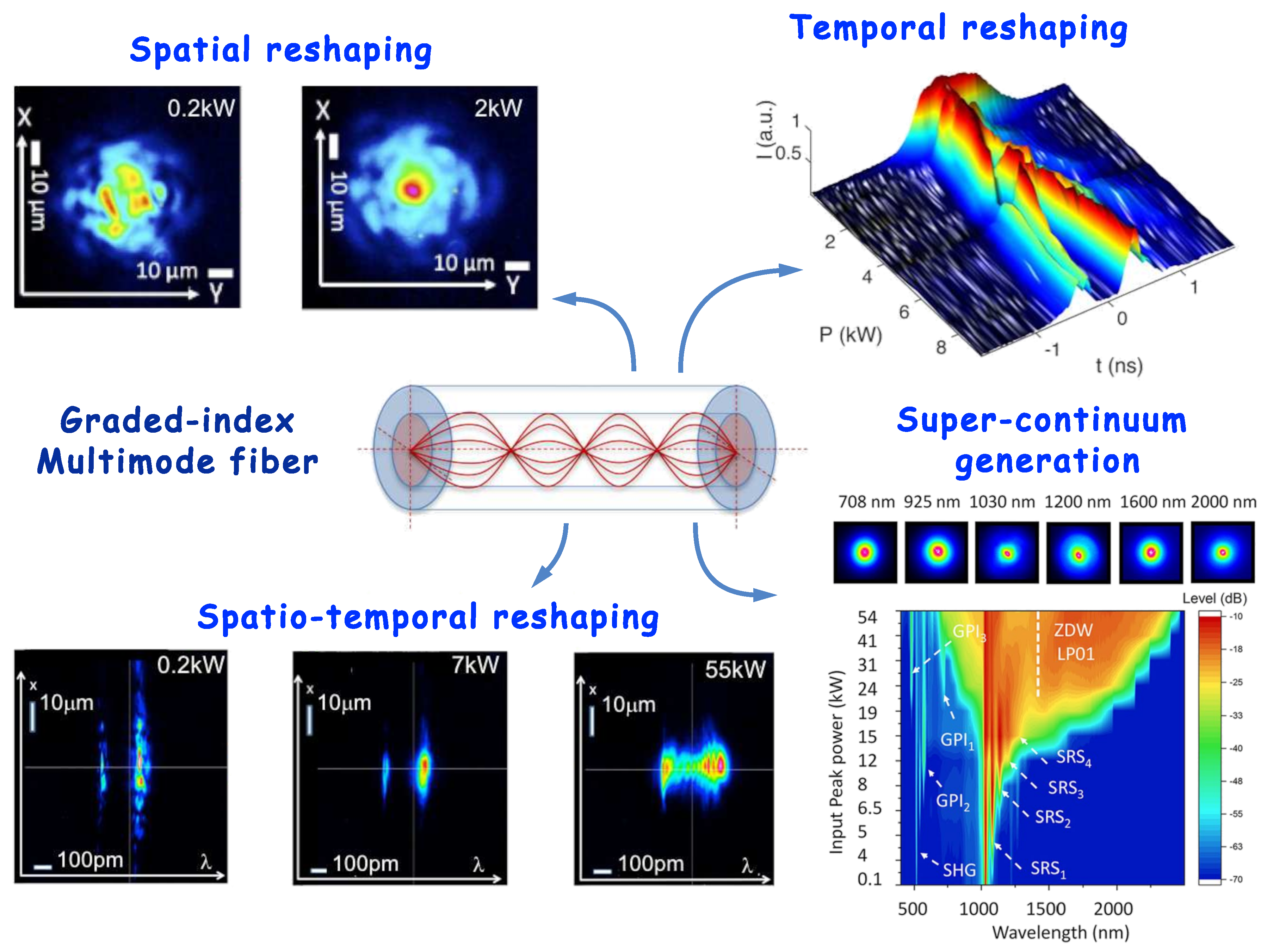

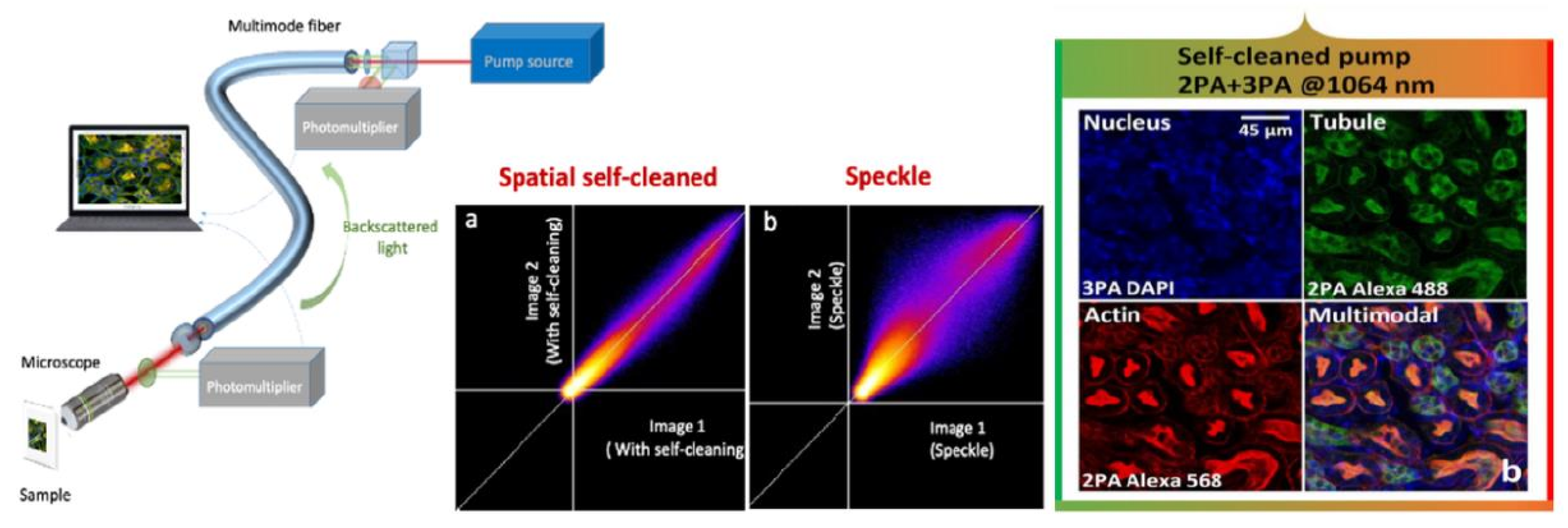

6.1. Beam Self-Cleaning and Supercontinuum Generation

6.2. Numerical Modeling

6.3. Image Acquisition Scanning System

6.4. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Post-Processing

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hracs, L.; Windsor, J.W.; Gorospe, J.; Cummings, M.; Coward, S.; Buie, M.J.; Quan, J.; Goddard, Q.; Caplan, L.; Markovinović, A.; et al. Global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease across epidemiologic stages. Nature 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alatab, S.; Sepanlou, S.G.; Ikuta, K.; Vahedi, H.; Bisignano, C.; Safiri, S.; Sadeghi, A.; Nixon, M.R.; Abdoli, A.; Abolhassani, H.; et al. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet gastroenterology & hepatology 2020, 5, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.C.; Shi, H.Y.; Hamidi, N.; Underwood, F.E.; Tang, W.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Wu, J.C.; Chan, F.K.; et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. The Lancet 2017, 390, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanizza, J.; Bencardino, S.; Allocca, M.; Furfaro, F.; Zilli, A.; Parigi, T.L.; Fiorino, G.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S.; D’Amico, F. Inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, W.Y.; Zhao, M.; Ng, S.C.; Burisch, J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East meets west. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology 2020, 35, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaden, J.; Abrams, K.; Mayberry, J. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut 2001, 48, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Su, T.; Xiao, T.; Xu, H.; Zhao, S. Colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis: an updated population-based systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2025, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaldaferri, F.; Fiocchi, C. Inflammatory bowel disease: progress and current concepts of etiopathogenesis. Journal of digestive diseases 2007, 8, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.P.C.; Gomes, C.; Torres, J. Familial and ethnic risk in inflammatory bowel disease. Annals of gastroenterology 2017, 31, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.B.; Yang, S.K.; Byeon, J.S.; Park, E.R.; Moon, G.; Myung, S.J.; Park, W.K.; Yoon, S.G.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, J.G.; et al. Familial occurrence of inflammatory bowel disease in Korea. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2006, 12, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevans, D.; Silverberg, M.S.; Borowski, K.; Griffiths, A.; Xu, W.; Onay, V.; Paterson, A.D.; Knight, J.; Croitoru, K.; Project, G. IBD genetic risk profile in healthy first-degree relatives of Crohn’s disease patients. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2016, 10, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.C.; Stappenbeck, T.S. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 2016, 11, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, N.; Kono, S.; Wakai, K.; Fukuda, Y.; Satomi, M.; Shimoyama, T.; Inaba, Y.; Miyake, Y.; Sasaki, S.; Okamoto, K.; et al. Dietary risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease A Multicenter Case-Control Study in Japan. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2005, 11, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, C.N.; Rawsthorne, P.; Cheang, M.; Blanchard, J.F. A population-based case control study of potential risk factors for IBD. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2006, 101, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.; Folan, A.M.; Lee, M.; Jones, G.; Brown, S.; Lobo, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after elective surgery for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Disease 2021, 23, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potten, C.S.; Kellett, M.; Rew, D.; Roberts, S.A. Proliferation in human gastrointestinal epithelium using bromodeoxyuridine in vivo: data for different sites, proximity to a tumour, and polyposis coli. Gut 1992, 33, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritsma, L.; Ellenbroek, S.I.; Zomer, A.; Snippert, H.J.; De Sauvage, F.J.; Simons, B.D.; Clevers, H.; Van Rheenen, J. Intestinal crypt homeostasis revealed at single-stem-cell level by in vivo live imaging. Nature 2014, 507, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.W.; Artis, D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nature reviews immunology 2014, 14, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, J.; Wells, J.; Cani, P.D.; García-Ródenas, C.L.; MacDonald, T.; Mercenier, A.; Whyte, J.; Troost, F.; Brummer, R.J. Human intestinal barrier function in health and disease. Clinical and translational gastroenterology 2016, 7, e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kany, S.; Vollrath, J.T.; Relja, B. Cytokines in inflammatory disease. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, 6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.E.; Gustafsson, J.K.; Holmén-Larsson, J.; Jabbar, K.S.; Xia, L.; Xu, H.; Ghishan, F.K.; Carvalho, F.A.; Gewirtz, A.T.; Sjövall, H.; et al. Bacteria penetrate the normally impenetrable inner colon mucus layer in both murine colitis models and patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 2014, 63, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eri, R.; Chieppa, M. Messages from the inside. The dynamic environment that favors intestinal homeostasis. Frontiers in immunology 2013, 4, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greten, F.R.; Grivennikov, S.I. Inflammation and cancer: triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 2019, 51, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Geng, S.; Luo, H.; Wang, W.; Mo, Y.Q.; Luo, Q.; Wang, L.; Song, G.B.; Sheng, J.P.; Xu, B. Signaling pathways involved in colorectal cancer: pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gono, K.; Obi, T.; Yamaguchi, M.; Ohyama, N.; Machida, H.; Sano, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Hamamoto, Y.; Endo, T. Appearance of enhanced tissue features in narrow-band endoscopic imaging. Journal of biomedical optics 2004, 9, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaniwa, N.; Namihisa, A.; Ogihara, T.; Ohkawa, A.; Abe, S.; Nagahara, A.; Kobayashi, O.; Sasaki, J.; Sato, N. Newly developed autofluorescence imaging videoscope system for the detection of colonic neoplasms. Digestive Endoscopy 2005, 17, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesslich, R.; Burg, J.; Vieth, M.; Gnaendiger, J.; Enders, M.; Delaney, P.; Polglase, A.; McLaren, W.; Janell, D.; Thomas, S.; et al. Confocal laser endoscopy for diagnosing intraepithelial neoplasias and colorectal cancer in vivo. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.D.; Friedland, S.; Sahbaie, P.; Soetikno, R.; Hsiung, P.L.; Liu, J.T.; Crawford, J.M.; Contag, C.H. Functional imaging of colonic mucosa with a fibered confocal microscope for real-time in vivo pathology. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2007, 5, 1300–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Anandasabapathy, S.; Richards-Kortum, R. Advances in optical gastrointestinal endoscopy: a technical review. Molecular Oncology 2021, 15, 2580–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ma, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liao, H.; Xie, T. Comprehensive advancement in endoscopy: optical design, algorithm enhancement, and clinical validation for merged WLI and CBI imaging. Biomedical Optics Express 2024, 15, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidani, K.; Moond, V.; Nagar, M.; Broder, A.; Thosani, N. Optical Imaging Technologies and Clinical Applications in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.K. Usefulness and future prospects of confocal laser endomicroscopy for gastric premalignant and malignant lesions. Clinical Endoscopy 2015, 48, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiriac, S.; Sfarti, C.V.; Minea, H.; Stanciu, C.; Cojocariu, C.; Singeap, A.M.; Girleanu, I.; Cuciureanu, T.; Petrea, O.; Huiban, L.; et al. Impaired intestinal permeability assessed by confocal laser endomicroscopy—a new potential therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel disease. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denk, W.; Strickler, J.H.; Webb, W.W. Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science 1990, 248, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila, F.J.; Gambín, A.; Artal, P.; Bueno, J.M. In vivo two-photon microscopy of the human eye. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borile, G.; Sandrin, D.; Filippi, A.; Anderson, K.I.; Romanato, F. Label-free multiphoton microscopy: Much more than fancy images. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, E.E.; Squier, J.A. Advances in multiphoton microscopy technology. Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wise, F.W. Recent advances in fiber lasers for nonlinear microscopy. Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.C.; Schnitzer, M.J. Multiphoton endoscopy. Opt. Lett. 2003, 28, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoundi, F.; Qin, Y.; Peyghambarian, N.; Barton, J.K.; Kieu, K. Compact fiber-based multi-photon endoscope working at 1700 nm. Biomedical optics express 2018, 9, 2326–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučikas, V.; Werner, M.P.; Schmitz-Rode, T.; Louradour, F.; van Zandvoort, M.A. Two-Photon Endoscopy: State of the Art and Perspectives. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2023, 25, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bufetov, I.A.; Kosolapov, A.F.; Pryamikov, A.D.; Gladyshev, A.V.; Kolyadin, A.N.; Krylov, A.A.; Yatsenko, Y.P.; Biriukov, A.S. Revolver hollow core optical fibers. Fibers 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladyshev, A.; Yatsenko, Y.; Kosolapov, A.; Myasnikov, D.; Bufetov, I. Propagation of megawatt subpicosecond light pulses with the minimum possible shape and spectrum distortion in an air- or argon-filled hollow-core revolver fibre. Quantum Electron. 2019, 49, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Galmiche, G.; Sanjabi Eznaveh, Z.; Eftekhar, M.A.; Antonio Lopez, J.; Wright, L.G.; Wise, F.; Christodoulides, D.; Amezcua Correa, R. Visible supercontinuum generation in a graded index multimode fiber pumped at 1064 nm. Opt. Lett. 2016, 41, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zitelli, M.; Ferraro, M.; Mangini, F.; Parra-Rivas, P.; Wabnitz, S. Multimode soliton collisions in graded-index optical fibers. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 21710, [2202.09843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.X.; Volkmer, A.; Book, L.D.; Xie, X.S. Multiplex coherent anti-stokes Raman scattering microspectroscopy and study of lipid vesicles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 8493–8498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbi, S.; Mansuryan, T.; Krupa, K.; Fabert, M.; Tonello, A.; Zitelli, M.; Ferraro, M.; Mangini, F.; Sun, Y.; Vergnole, S.; et al. Continuous spatial self-cleaning in GRIN multimode fiber for self-referenced multiplex CARS imaging. Optics Express 2022, 30, 16104–16114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, Z.; Xing, D. Optical coherence hyperspectral microscopy with a single supercontinuum light source. J. Biophotonics 2021, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, N.T.; Jones, G.; Maier-Hein, L.; Elson, D.S.; Stoyanov, D. Surgical spectral imaging. Medical image analysis 2020, 63, 101699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, T.M.; Martins, I.S.; Silva, H.F.; Tuchin, V.V.; Oliveira, L.M. Spectral optical properties of rabbit brain cortex between 200 and 1000 nm. Photochem 2021, 1, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, M.S.; Raju, M.; Gunther, J.; Maryam, S.; Amissah, M.; Lu, H.; Killeen, S.; O’Riordain, M.; Andersson-Engels, S. Tissue biomolecular and microstructure profiles in optical colorectal cancer delineation. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2021, 54, 454002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krainov, A.; Mokeeva, A.; Sergeeva, E.; Agrba, P.; Kirillin, M.Y. Optical properties of mouse biotissues and their optical phantoms. Optics and Spectroscopy 2013, 115, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, I.; Carvalho, S.; Henrique, R.; Oliveira, L.; Tuchin, V.V. Kinetics of optical properties of colorectal muscle during optical clearing. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2018, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.; Gueiral, N.; Nogueira, E.; Henrique, R.; Oliveira, L.; Tuchin, V.V. Comparative study of the optical properties of colon mucosa and colon precancerous polyps between 400 and 1000 nm. Proceedings of the Dynamics and Fluctuations in Biomedical Photonics XIV. SPIE 2017, Vol. 10063, 218–233. [Google Scholar]

- Bashkatov, A.N.; Genina, E.; Kochubey, V.I.; Rubtsov, V.; Kolesnikova, E.A.; Tuchin, V.V. Optical properties of human colon tissues in the 350-2500 nm spectral range. Quantum Electronics 2014, 44, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumashiro, R.; Konishi, K.; Chiba, T.; Akahoshi, T.; Nakamura, S.; Murata, M.; Tomikawa, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Maehara, Y.; Hashizume, M. Integrated endoscopic system based on optical imaging and hyperspectral data analysis for colorectal cancer detection. Anticancer research 2016, 36, 3925–3932. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.; Joseph, J.; Waterhouse, D.J.; Luthman, A.S.; Gordon, G.S.; Di Pietro, M.; Januszewicz, W.; Fitzgerald, R.C.; Bohndiek, S.E. A clinically translatable hyperspectral endoscopy (HySE) system for imaging the gastrointestinal tract. Nature communications 2019, 10, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.; Bachir, W.; El-Daher, M.S. Optical investigation of bovine grey and white matters in visible and near-infrared ranges. Polish Journal of Medical Physics and Engineering 2021, 27, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonios, G.; Perelman, L.T.; Backman, V.; Manoharan, R.; Fitzmaurice, M.; Van Dam, J.; Feld, M.S. Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy of human adenomatous colon polyps in vivo. Applied optics 1999, 38, 6628–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.W.; Jiang, J.K.; Lin, C.H.; Lin, J.K.; Huang, G.J.; Yu, J.S. Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy detects increased hemoglobin concentration and decreased oxygenation during colon carcinogenesis from normal to malignant tumors. Optics express 2009, 17, 2805–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, A.C.; Bottiroli, G. Autofluorescence spectroscopy and imaging: a tool for biomedical research and diagnosis. European journal of histochemistry: EJH 2014, 58, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukina, M.; Shirmanova, M.; Sergeeva, T.; Zagaynova, E. Metabolic Imaging in the Study of Oncological Processes (Review). Sovrem. Tehnol. v Med. 2016, 8, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapova, E.V.; Dremin, V.V.; Shupletsov, V.V.; Kandurova, K.Y.; Dunaev, A.V. Optical percutaneous needle biopsy in oncology. Light Adv. Manuf. 2025, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosnell, M.E.; Anwer, A.G.; Mahbub, S.B.; Menon Perinchery, S.; Inglis, D.W.; Adhikary, P.P.; Jazayeri, J.A.; Cahill, M.A.; Saad, S.; Pollock, C.A.; et al. Quantitative non-invasive cell characterisation and discrimination based on multispectral autofluorescence features. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 23453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croce, A.C.; Ferrigno, A.; Bottiroli, G.; Vairetti, M. Autofluorescence-based optical biopsy: An effective diagnostic tool in hepatology. Liver International 2018, 38, 1160–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahbub, S.B.; Guller, A.; Campbell, J.M.; Anwer, A.G.; Gosnell, M.E.; Vesey, G.; Goldys, E.M. Non-invasive monitoring of functional state of articular cartilage tissue with label-free unsupervised hyperspectral imaging. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.M.; Walters, S.N.; Habibalahi, A.; Mahbub, S.B.; Anwer, A.G.; Handley, S.; Grey, S.T.; Goldys, E.M. Pancreatic islet viability assessment using hyperspectral imaging of autofluorescence. Cells 2023, 12, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, B.; Renkoski, T.; Graves, L.R.; Rial, N.S.; Tsikitis, V.L.; Nfonsam, V.; Pugh, J.; Tiwari, P.; Gavini, H.; Utzinger, U. Tryptophan autofluorescence imaging of neoplasms of the human colon. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2012, 17, 016003–016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, B.; Rial, N.S.; Renkoski, T.; Graves, L.R.; Reid, S.A.; Hu, C.; Tsikitis, V.L.; Nfonsom, V.; Pugh, J.; Utzinger, U. Enhanced visibility of colonic neoplasms using formulaic ratio imaging of native fluorescence. Lasers in surgery and medicine 2013, 45, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yang, F.; Xie, S. Extracting autofluorescence spectral features for diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Laser Physics 2012, 22, 1431–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekara, C.M.; Gemikonakli, G.; Mach, J.; Sang, R.; Anwer, A.G.; Agha, A.; Goldys, E.M.; Hilmer, S.N.; Campbell, J.M. Ageing and Polypharmacy in Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Metabolic Impact Assessed by Hyperspectral Imaging of Autofluorescence. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.M.; Habibalahi, A.; Mahbub, S.; Gosnell, M.; Anwer, A.G.; Paton, S.; Gronthos, S.; Goldys, E. Non-destructive, label free identification of cell cycle phase in cancer cells by multispectral microscopy of autofluorescence. BMC cancer 2019, 19, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaster, T.M.; Walsh, A.J.; Zhao, Y.; Hiebert, S.W.; Skala, M.C. Autofluorescence imaging identifies tumor cell-cycle status on a single-cell level. Journal of biophotonics 2018, 11, e201600276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibalahi, A.; Moghari, M.D.; Campbell, J.M.; Anwer, A.G.; Mahbub, S.B.; Gosnell, M.; Saad, S.; Pollock, C.; Goldys, E.M. Non-invasive real-time imaging of reactive oxygen species (ROS) using auto-fluorescence multispectral imaging technique: A novel tool for redox biology. Redox biology 2020, 34, 101561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarto, J.L.; Dyer, B.T.; Talbot, C.B.; Peters, N.S.; French, P.M.; Lyon, A.R.; Dunsby, C. Characterization of NAD (P) H and FAD autofluorescence signatures in a Langendorff isolated-perfused rat heart model. Biomedical optics express 2018, 9, 4961–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrando, A.I.; Fernandez, L.M.; Azevedo, J.; Vieira, P.; Domingos, H.; Galzerano, A.; Shcheslavskiy, V.; Heald, R.J.; Parvaiz, A.; da Silva, P.G.; et al. Detection and characterization of colorectal cancer by autofluorescence lifetime imaging on surgical specimens. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 24575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolenc, O.I.; Quinn, K.P. Evaluating cell metabolism through autofluorescence imaging of NAD (P) H and FAD. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2019, 30, 875–889. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, A.K.; Simón-Santamaría, J.; Elvevold, K.; Ericzon, B.G.; Mortensen, K.E.; McCourt, P.; Smedsrød, B.; Sørensen, K.K. Autofluorescence in freshly isolated adult human liver sinusoidal cells. European Journal of Histochemistry: EJH 2021, 65, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, J.R.; Duncker, T. Fundus autofluorescence and RPE lipofuscin in age-related macular degeneration. Journal of clinical medicine 2014, 3, 1302–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak, M.; James, J.; Grantham, J.; Ericson, M.B. Contribution of autofluorescence from intracellular proteins in multiphoton fluorescence lifetime imaging. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 16584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Zou, J.; Xie, T.; Zeng, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, B.; Liao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wu, G.; Zhang, G.; et al. Decreased green autofluorescence in cancerous tissues is a potential biomarker for diagnosis of renal cell carcinomas. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 26798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, B.; Chatterjee, J.; Paul, R.R.; Acuña, S.; Lahiri, P.; Pal, M.; Mitra, P.; Agarwal, K. Molecular histopathology of matrix proteins through autofluorescence super-resolution microscopy. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 10524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazeer, S.S.; Saraswathy, A.; Shenoy, S.J.; Jayasree, R.S. Fluorescence spectroscopy as an efficient tool for staging the degree of liver fibrosis: an in vivo comparison with MRI. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 10967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgakoudi, I.; Jacobson, B.C.; Muller, M.G.; Sheets, E.E.; Badizadegan, K.; Carr-Locke, D.L.; Crum, C.P.; Boone, C.W.; Dasari, R.R.; Van Dam, J.; et al. NAD (P) H and collagen as in vivo quantitative fluorescent biomarkers of epithelial precancerous changes. Cancer research 2002, 62, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Zheng, W.; Xie, S.; Chen, R.; Zeng, H.; McLean, D.I.; Lui, H. Laser-induced autofluorescence microscopy of normal and tumor human colonic tissue. International journal of oncology 2004, 24, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, X.; Zheng, W.; Huang, Z. In vivo diagnosis of colonic precancer and cancer using near-infrared autofluorescence spectroscopy and biochemical modeling. Journal of biomedical optics 2011, 16, 067005–067005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Zheng, W.; Huang, Z. Near-infrared autofluorescence spectroscopy for in vivo identification of hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps in the colon. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2011, 30, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, J.L.; Subhash, N.; Stephen, M.; Philip, E.K.; Beena, V.T. Comparative evaluation of the diagnostic performance of autofluorescence and diffuse reflectance in oral cancer detection: a clinical study. Journal of biophotonics 2011, 4, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaleon, L.; Durkin, A.J.; Tu, J.H.; Menaker, G.; Fallon, J.D.; Kollias, N. In vivo fluorescence spectroscopy of nonmelanoma skin cancer¶. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2001, 73, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Qu, J.Y.; Cheung, T.H.; Lo, K.W.K.; Yu, M.Y. Preliminary study of detecting neoplastic growths in vivo with real time calibrated autofluorescence imaging. Optics express 2003, 11, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, C.R.; Cutruzzola, F.W.; O’Brien, K.M.; Stetz, M.L.; Enriquez, R.; Deckelbaum, L.I. Laser-induced fluorescence spectroscopy of human colonic mucosa: detection of adenomatous transformation. Gastroenterology 1990, 99, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Tang, G.; Bessler, M.; Alfano, R. Fluorescence spectroscopy as a photonic pathology method for detecting colon cancer. Lasers in the Life Sciences 1995, 6, 259–276. [Google Scholar]

- Cothren, R.; Richards-Kortum, R.; Sivak, M., Jr.; Fitzmaurice, M.; Rava, R.; Boyce, G.; Doxtader, M.; Blackman, R.; Ivanc, T.; Hayes, G.; et al. Gastrointestinal tissue diagnosis by laser-induced fluorescence spectroscopy at endoscopy. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 1990, 36, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eker, C.; Montan, S.; Jaramillo, E.; Koizumi, K.; Rubio, C.; Andersson-Engels, S.; Svanberg, K.; Svanberg, S.; Slezak, P. Clinical spectral characterisation of colonic mucosal lesions using autofluorescence and aminolevulinic acid sensitisation. Gut 1999, 44, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schomacker, K.T.; Frisoli, J.K.; Compton, C.C.; Flotte, T.J.; Richter, J.M.; Deutsch, T.F.; Nishioka, N.S. Ultraviolet laser-induced fluorescence of colonic polyps. Gastroenterology 1992, 102, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cothren, R.M.; Sivak, M.V., Jr.; Van Dam, J.; Petras, R.E.; Fitzmaurice, M.; Crawford, J.M.; Wu, J.; Brennan, J.F.; Rava, R.P.; Manoharan, R.; et al. Detection of dysplasia at colonoscopy using laser-induced fluorescence: a blinded study. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 1996, 44, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayinger, B.; Jordan, M.; Horbach, T.; Horner, P.; Gerlach, C.; Mueller, S.; Hohenberger, W.; Hahn, E.G. Evaluation of in vivo endoscopic autofluorescence spectroscopy in gastric cancer. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 2004, 59, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa-Ankerhold, H.C.; Ankerhold, R.; Drummen, G.P. Advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques—Frap, Flip, Flap, Fret and flim. Molecules 2012, 17, 4047–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coda, S.; Thompson, A.J.; Kennedy, G.T.; Roche, K.L.; Ayaru, L.; Bansi, D.S.; Stamp, G.W.; Thillainayagam, A.V.; French, P.M.; Dunsby, C. Fluorescence lifetime spectroscopy of tissue autofluorescence in normal and diseased colon measured ex vivo using a fiber-optic probe. Biomedical optics express 2014, 5, 515–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall-Demllo, S.; Al-Qadami, G.; Raposo, A.E.; Ma, C.; Priebe, I.K.; Hor, M.; Singh, R.; Fung, K.Y. Ex Vivo Intestinal Organoid Models: Current State-of-the-Art and Challenges in Disease Modelling and Therapeutic Testing for Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergenheim, F.; Fregni, G.; Buchanan, C.F.; Riis, L.B.; Heulot, M.; Touati, J.; Seidelin, J.B.; Rizzi, S.C.; Nielsen, O.H. A fully defined 3D matrix for ex vivo expansion of human colonic organoids from biopsy tissue. Biomaterials 2020, 262, 120248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paola, F.J.; Calafato, G.; Piccaluga, P.P.; Tallini, G.; Rhoden, K.J. Patient-Derived Organoid Biobanks for Translational Research and Precision Medicine: Challenges and Future Perspectives. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2025, 15, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flood, P.; Hanrahan, N.; Nally, K.; Melgar, S. Human intestinal organoids: Modeling gastrointestinal physiology and immunopathology—current applications and limitations. European Journal of Immunology 2024, 54, 2250248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieger, K.M.; Schröder, V.; Dehmel, S.; Neuhaus, V.; Schaudien, D.; Fuchs, M.; Linge, H.; Wagner, A.; Kulik, U.; Gundert, B.; et al. Ex Vivo Modeling and Pharmacological Modulation of Tissue Immune Responses in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Using Precision-Cut Intestinal Slices. European Journal of Immunology 2025, 55, e70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyck, K.; Vanhoffelen, E.; Yserbyt, J.; Van Dijck, P.; Erreni, M.; Hernot, S.; Vande Velde, G. Probe-based intravital microscopy: filling the gap between in vivo imaging and tissue sample microscopy in basic research and clinical applications. Journal of Physics: Photonics 2021, 3, 032003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minsky, M. Memoir on inventing the confocal scanning microscope. Scanning 1988, 10, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piston, D.W. When Two Is Better Than One: Elements of Intravital Microscopy. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osdoit, A.; Genet, M.; Perchant, A.; Loiseau, S.; Abrat, B.; Lacombe, F. In vivo fibered confocal reflectance imaging: totally non-invasive morphological cellular imaging brought to the endoscopist. Proceedings of the Endoscopic Microscopy. SPIE 2006, Vol. 6082, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pilonis, N.D.; Januszewicz, W.; di Pietro, M. Confocal laser endomicroscopy in gastro-intestinal endoscopy: technical aspects and clinical applications. Translational Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2022, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palma, G.D. Confocal laser endomicroscopy in the “in vivo” histological diagnosis of the gastrointestinal tract. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG 2009, 15, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, H.; Hara, K.; Nozomi, O.; Kuwahara, T.; Nobumasa, M.; Haba, S.; Akira, M.; Hajime, I. High-resolution probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy for diagnosing biliary diseases. Clinical Endoscopy 2021, 54, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Lin, L.L.; Prow, T.W. Multiphoton Microscopy Applications in Biology. In Fluoresc. Microsc.; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 185–197. [CrossRef]

- Entenberg, D.; Oktay, M.H.; Condeelis, J.S. Intravital imaging to study cancer progression and metastasis. Nature Reviews Cancer 2023, 23, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooz, M.; Maldonado, E.N. Fluorescence microscopy imaging of mitochondrial metabolism in cancer cells. Frontiers in oncology 2023, 13, 1152553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, A.J.; Renteria, C.; Li, J.; Marjanovic, M.; Barkalifa, R.; Boppart, S.A. High-speed label-free two-photon fluorescence microscopy of metabolic transients during neuronal activity. Applied Physics Letters 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Two-photon excitation microscopy. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two-photon_excitation_microscopy. Accessed: 2025-11-27.

- Liang, W.; Hall, G.; Messerschmidt, B.; Li, M.J.; Li, X. Nonlinear optical endomicroscopy for label-free functional histology in vivo. Light: Science & Applications 2017, 6, e17082–e17082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Légaré, F.; Evans, C.L.; Ganikhanov, F.; Xie, X.S. Towards CARS endoscopy. Optics Express 2006, 14, 4427–4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhani, N.; Kakkava, E.; Moser, C.; Psaltis, D. Learning to see through multimode fibers. Optica 2018, 5, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramazza, P.; Moran, O.; Murray-Smith, R.; Faccio, D. Transmission of natural scene images through a multimode fibre. Nature communications 2019, 10, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusarz, R.K.; Sayeh, M.R. Neural network-based multimode fiber-optic information transmission. Applied optics 2001, 40, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellekoop, I.M.; Mosk, A.P. Focusing coherent light through opaque strongly scattering media. Optics letters 2007, 32, 2309–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisawa, S.; Noguchi, K.; Matsumoto, T. Remote image classification through multimode optical fiber using a neural network. Optics letters 1991, 16, 645–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popoff, S.M.; Lerosey, G.; Carminati, R.; Fink, M.; Boccara, A.C.; Gigan, S. Measuring the Transmission Matrix in Optics: An Approach to the Study and. Physical review letters 2010, 104, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupa, K.; Tonello, A.; Shalaby, B.M.; Fabert, M.; Barthélémy, A.; Millot, G.; Wabnitz, S.; Couderc, V. Spatial beam self-cleaning in multimode fibres. Nature photonics 2017, 11, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, N.O.; Mansuryan, T.; Hage, C.H.; Fabert, M.; Krupa, K.; Tonello, A.; Ferraro, M.; Leggio, L.; Zitelli, M.; Mangini, F.; et al. Spatiotemporal beam self-cleaning for high-resolution nonlinear fluorescence imaging with multimode fiber. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 18240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardini, A.; Mytskaniuk, V.; Sivankutty, S.; Andresen, E.R.; Chen, X.; Wenger, J.; Fabert, M.; Joly, N.; Louradour, F.; Kudlinski, A.; et al. High-resolution multimodal flexible coherent Raman endoscope. Light: Science & Applications 2018, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Ma, J.; Cui, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Wu, D.; Fu, Q.; Liang, L.; et al. Spiral scanning fiber-optic two-photon endomicroscopy with a double-cladding antiresonant fiber. Optics Express 2021, 29, 43124–43135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septier, D.; Mytskaniuk, V.; Habert, R.; Labat, D.; Baudelle, K.; Cassez, A.; Brévalle-Wasilewski, G.; Conforti, M.; Bouwmans, G.; Rigneault, H.; et al. Label-free highly multimodal nonlinear endoscope. Optics Express 2022, 30, 25020–25033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, W.R.; Williams, R.M.; Webb, W.W. Nonlinear magic: multiphoton microscopy in the biosciences. Nature biotechnology 2003, 21, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Lin, L.L.; Prow, T.W. Multiphoton microscopy applications in biology. In Fluorescence microscopy; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 185–197.

- Cristiani, I.; Lacava, C.; Rademacher, G.; Puttnam, B.J.; Luìs, R.S.; Antonelli, C.; Mecozzi, A.; Shtaif, M.; Cozzolino, D.; Bacco, D.; et al. Roadmap on multimode photonics. J. Opt. 2022, 24, 083001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuryan, T.; Tabcheh, N.; Fabert, M.; Krupa, K.; Jauberteau, R.; Tonello, A.; Lefort, C.; Ferraro, M.; Mangini, F.; Zitelli, M.; et al. Large band multiphoton microendoscope with single-core standard graded-index multimode fiber based on spatial beam self-cleaning. Proceedings of the Endoscopic Microscopy XVIII. SPIE 2023, Vol. 12356, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, T.H.; Jee, S.H.; Dong, C.Y.; Lin, S.J. Multiphoton microscopy in dermatological imaging. Journal of dermatological science 2009, 56, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupa, K.; Louot, C.; Couderc, V.; Fabert, M.; Guénard, R.; Shalaby, B.; Tonello, A.; Pagnoux, D.; Leproux, P.; Bendahmane, A.; et al. Spatiotemporal characterization of supercontinuum extending from the visible to the mid-infrared in a multimode graded-index optical fiber. Optics Letters 2016, 41, 5785–5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslami, Z.; Salmela, L.; Filipkowski, A.; Pysz, D.; Klimczak, M.; Buczynski, R.; Dudley, J.M.; Genty, G. Two octave supercontinuum generation in a non-silica graded-index multimode fiber. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conforti, M.; Mas Arabi, C.; Mussot, A.; Kudlinski, A. Fast and accurate modeling of nonlinear pulse propagation in graded-index multimode fibers. Optics Letters 2017, 42, 4004–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, A.S.; Agrawal, G.P. Graded-index solitons in multimode fibers. Optics letters 2018, 43, 3345–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teğin, U.; Ortaç, B. Cascaded Raman scattering based high power octave-spanning supercontinuum generation in graded-index multimode fibers. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 12470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, F.; Horak, P. Description of ultrashort pulse propagation in multimode optical fibers. Journal of the Optical Society of America B 2008, 25, 1645–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, F.; Horak, P. Dynamics of femtosecond supercontinuum generation in multimode fibers. Optics Express 2009, 17, 6134–6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.G.; Wabnitz, S.; Christodoulides, D.N.; Wise, F.W. Ultrabroadband dispersive radiation by spatiotemporal oscillation of multimode waves. Physical review letters 2015, 115, 223902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakimov, R.; Shavrin, I.; Novotny, S.; Kaivola, M.; Ludvigsen, H. Numerical solver for supercontinuum generation in multimode optical fibers. Optics express 2013, 21, 14388–14398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.G.; Ziegler, Z.M.; Lushnikov, P.M.; Zhu, Z.; Eftekhar, M.A.; Christodoulides, D.N.; Wise, F.W. Multimode nonlinear fiber optics: massively parallel numerical solver, tutorial, and outlook. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2017, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehler, M.; Schirwon, M.; Krummrich, P.M.; Göddeke, D. Simulation of nonlinear signal propagation in multimode fibers on multi-GPU systems. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation 2020, 84, 105150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibinger, R.; Lüpken, N.M.; Chemnitz, M.; Schaarschmidt, K.; Kobelke, J.; Fallnich, C.; Schmidt, M.A. Higher-order mode supercontinuum generation in dispersion-engineered liquid-core fibers. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krutova, E.; Salmela, L.; Eslami, Z.; Karpate, T.; Klimczak, M.; Buczynski, R.; Genty, G. Supercontinuum generation in a graded-index multimode tellurite fiber. Optics Letters 2024, 49, 2865–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podivilov, E.V.; Kharenko, D.S.; Gonta, V.; Krupa, K.; Sidelnikov, O.S.; Turitsyn, S.; Fedoruk, M.P.; Babin, S.A.; Wabnitz, S. Hydrodynamic 2D turbulence and spatial beam condensation in multimode optical fibers. Physical review letters 2019, 122, 103902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidelnikov, O.S.; Podivilov, E.V.; Fedoruk, M.P.; Wabnitz, S. Random mode coupling assists Kerr beam self-cleaning in a graded-index multimode optical fiber. Optical Fiber Technology 2019, 53, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, S.A.; Kuznetsov, A.G.; Sidelnikov, O.S.; Wolf, A.A.; Nemov, I.N.; Kablukov, S.I.; Podivilov, E.V.; Fedoruk, M.P.; Wabnitz, S. Spatio-spectral beam control in multimode diode-pumped Raman fibre lasers via intracavity filtering and Kerr cleaning. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 21994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Cui, H.; Ma, J.; Wu, R.; Liu, H.; Wang, A.; Feng, L. Research Advances in Piezoelectric Ceramic Scanning Two-Photon Endomicroscopy Technology. Chinese Journal of Lasers 2022, 49, 1907003. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, D.R.; Brown, C.M.; Ouzounov, D.G.; Pavlova, I.; Kobat, D.; Webb, W.W.; Xu, C. Compact and flexible raster scanning multiphoton endoscope capable of imaging unstained tissue. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 17598–17603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducourthial, G.; Leclerc, P.; Mansuryan, T.; Fabert, M.; Brevier, J.; Habert, R.; Braud, F.; Batrin, R.; Vever-Bizet, C.; Bourg-Heckly, G.; et al. Development of a real-time flexible multiphoton microendoscope for label-free imaging in a live animal. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 18303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, K.; Hughes, M.; Rosa, B.G.; Yang, G.Z. Fiber bundle shifting endomicroscopy for high-resolution imaging. Biomedical optics express 2018, 9, 4649–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.Y.; Hwang, K.; Ahn, J.; Seo, Y.H.; Kim, J.B.; Lee, S.; Yoon, J.H.; Kong, E.; Jeong, Y.; Jon, S.; et al. Lissajous scanning two-photon endomicroscope for in vivo tissue imaging. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myaing, M.T.; MacDonald, D.J.; Li, X. Fiber-optic scanning two-photon fluorescence endoscope. Optics letters 2006, 31, 1076–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liang, X.; Fu, L. Four-plate piezoelectric actuator driving a large-diameter special optical fiber for nonlinear optical microendoscopy. Optics Express 2016, 24, 19949–19960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistenev, Y.V.; Nikolaev, V.V.; Kurochkina, O.S.; Borisov, A.V.; Vrazhnov, D.A.; Sandykova, E.A. Application of multiphoton imaging and machine learning to lymphedema tissue analysis. Biomedical optics express 2019, 10, 3353–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistenev, Y.V.; Vrazhnov, D.; Nikolaev, V.; Sandykova, E.; Krivova, N. Analysis of collagen spatial structure using multiphoton microscopy and machine learning methods. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2019, 84, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Endogenous fluorophores | Autofluorescence excitation and emission ranges | |

|---|---|---|

| NAD(P)H |

372 nm 375 nm 330–380 nm 330–360 nm |

430–480 nm [75] 456–484 nm [76] 440–462 nm [61] 440–470 nm [77] |

| FAD |

438 nm 445 nm 360–465 nm |

500–550 nm [75] 456–484 nm [76] 520–530 nm [77] |

| Vitamin A | 370–380 nm | 490–510 nm [61,78] |

| Lipofuscin |

400–500 nm 450–490 nm |

480–700 nm [61] 400–700 nm [79] |

| Keratin |

280–325 nm 355–415 nm 488 nm |

495–525 nm [61] 400–520 nm [80] 500–550 nm [81] |

| Collagen |

320–410 nm 375 nm |

400–510 nm [82] 380–420 nm [76] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).