Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

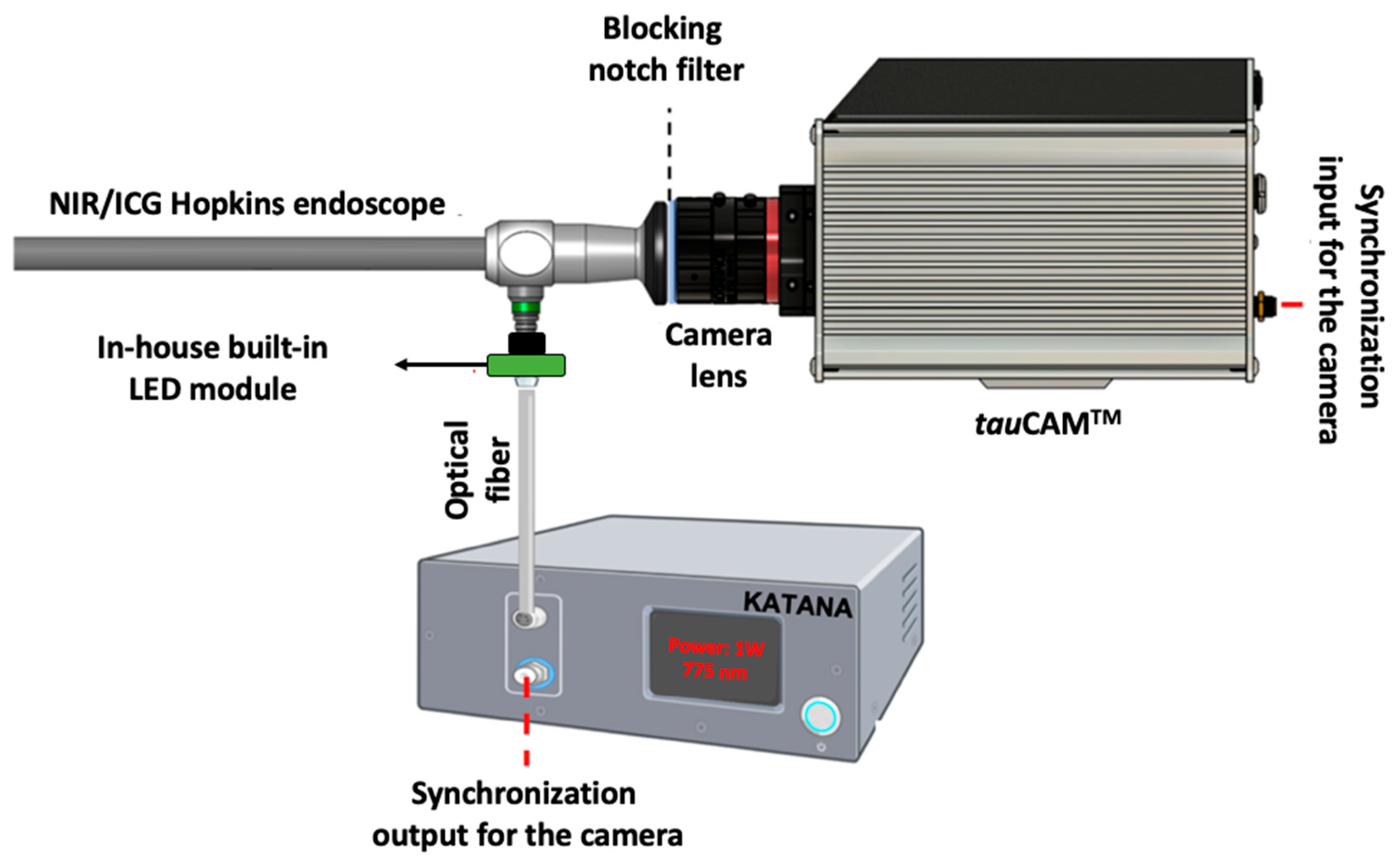

2. Experimental Setup

3. Design and Method

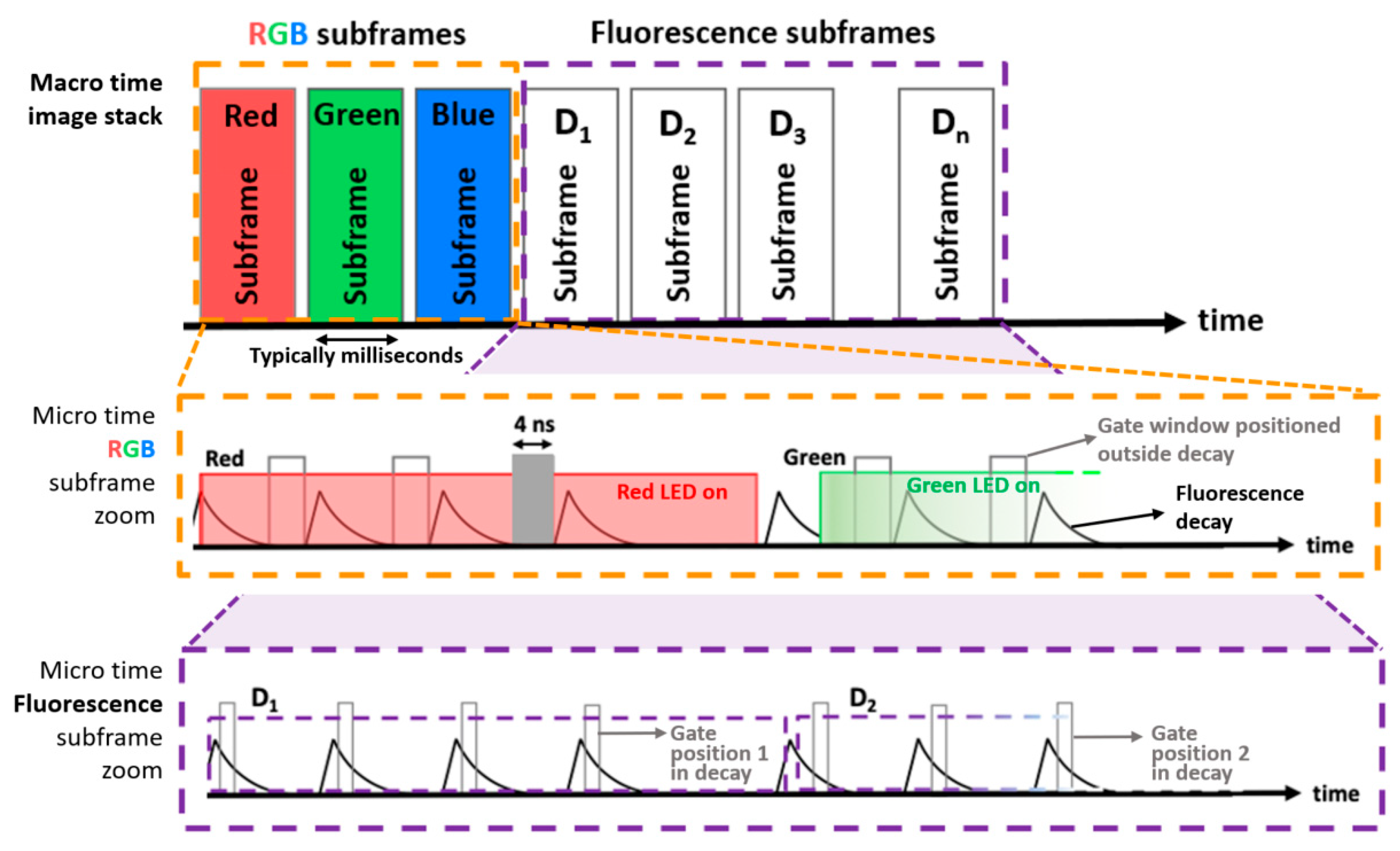

3.1. LED-Based Time-Domain Sequential RGB and NIR Laser-Based Illumination

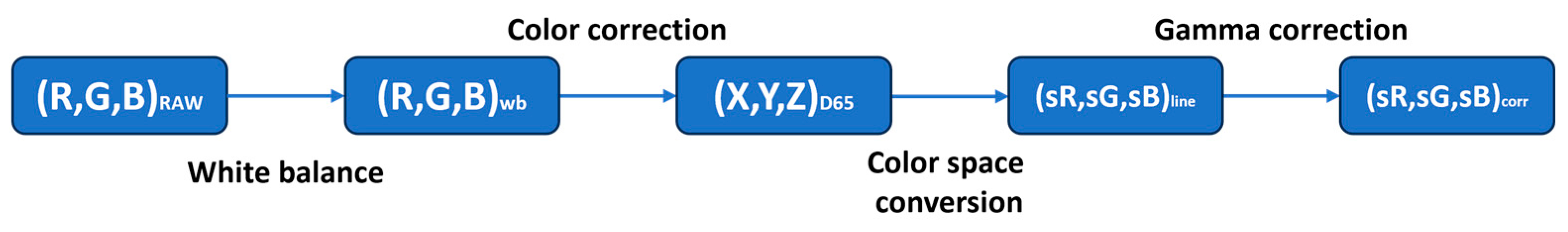

3.2. Image Processing Pipeline

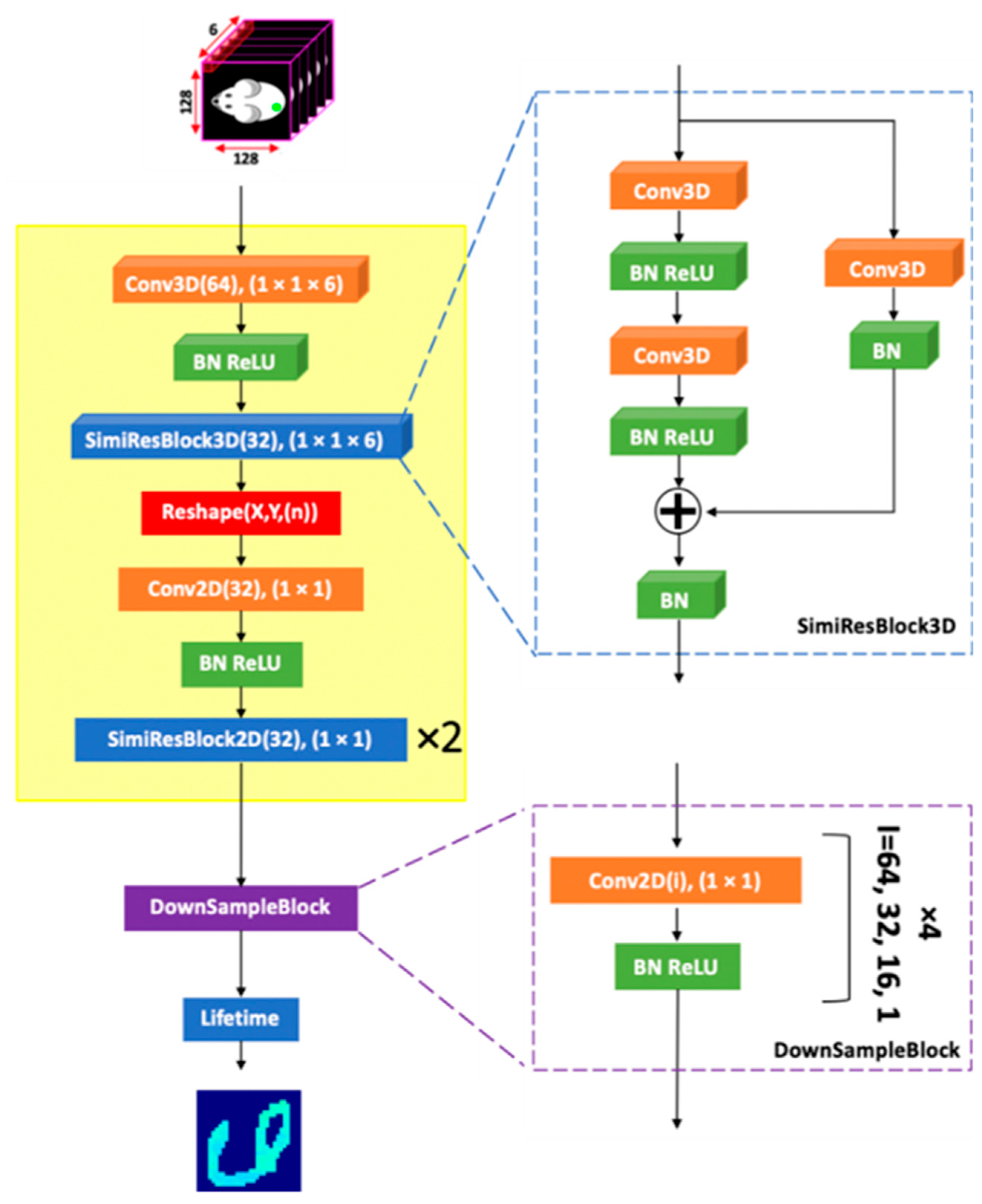

3.3. Fluorescence-Lifetime Processing

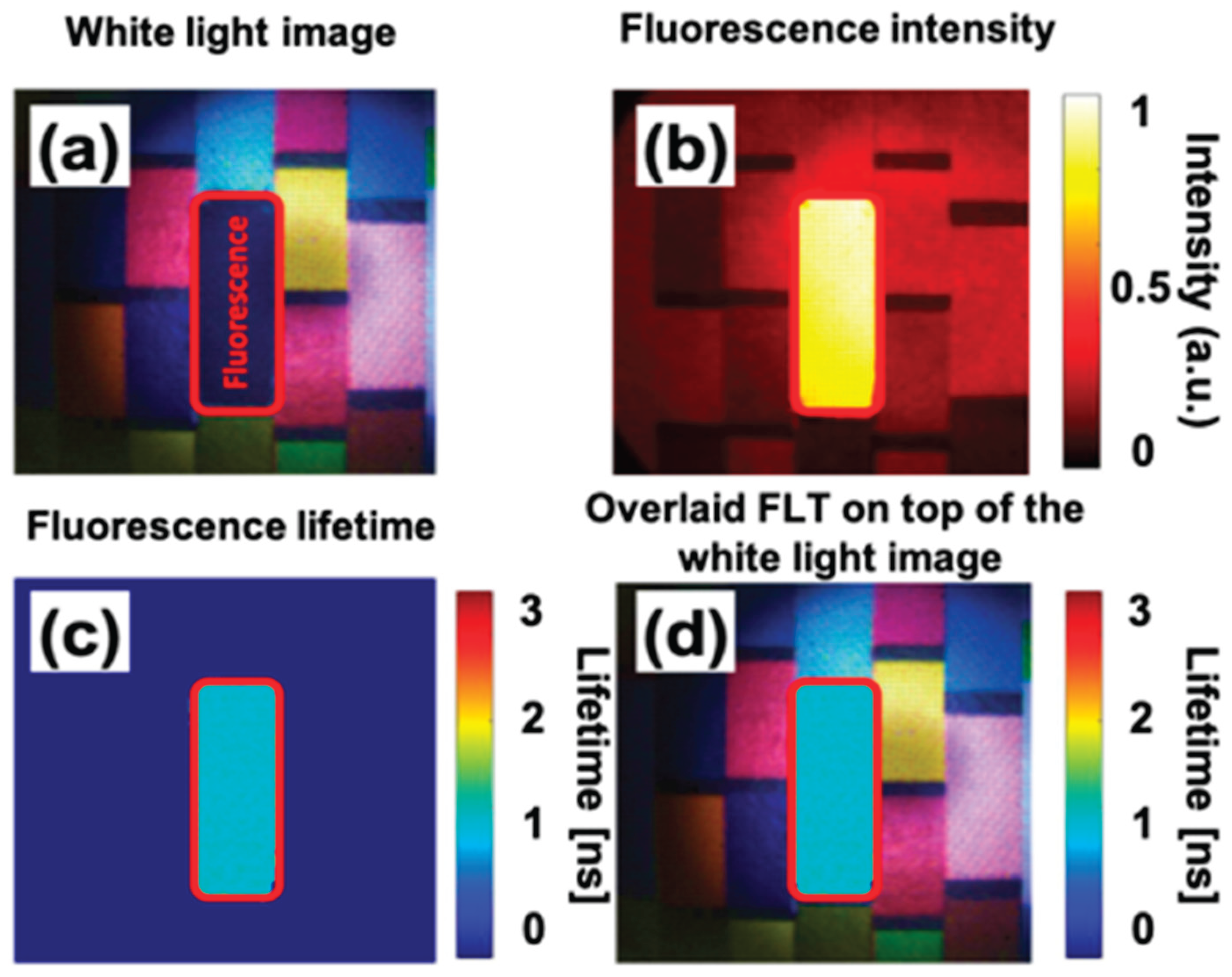

4. Results and Discussion

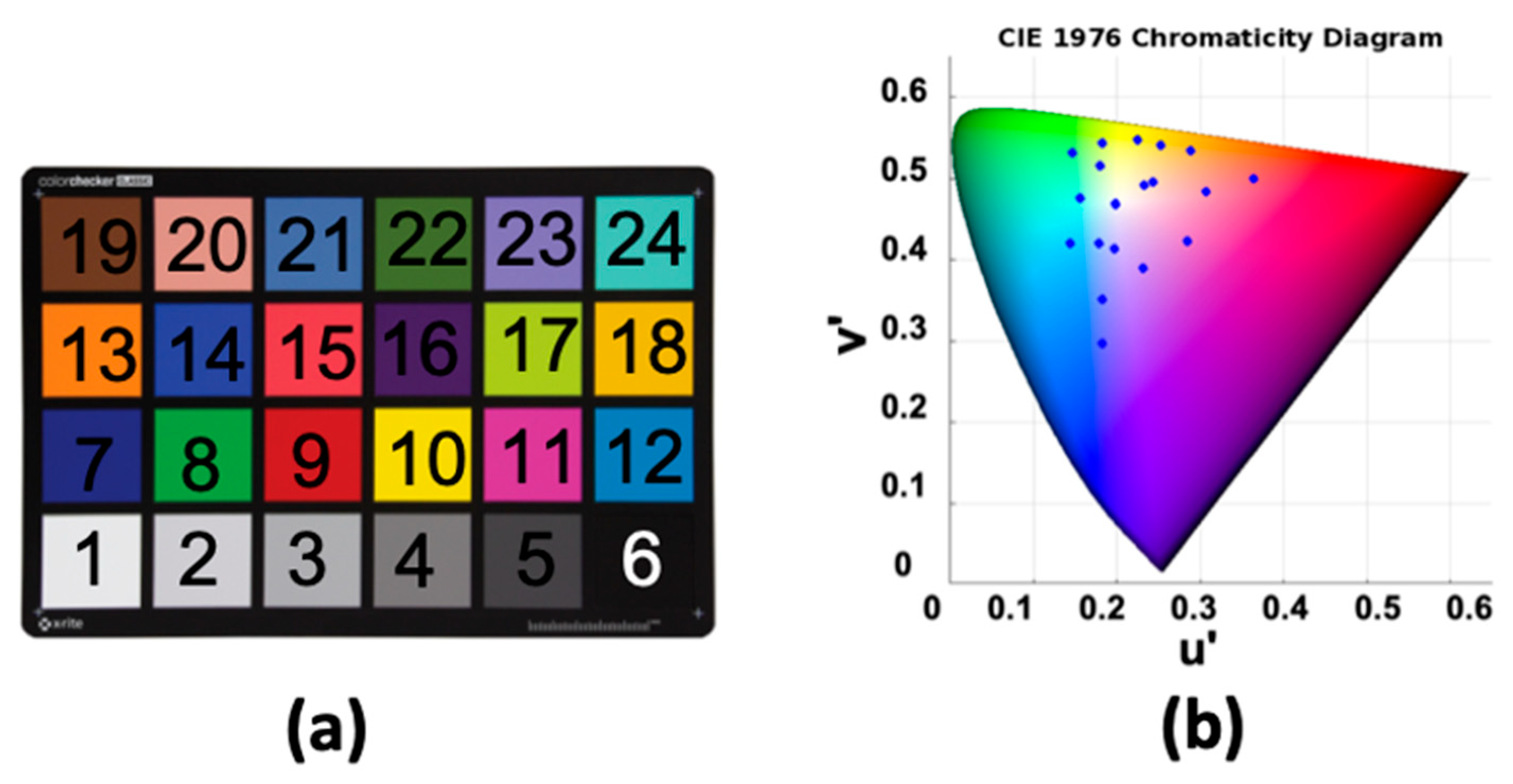

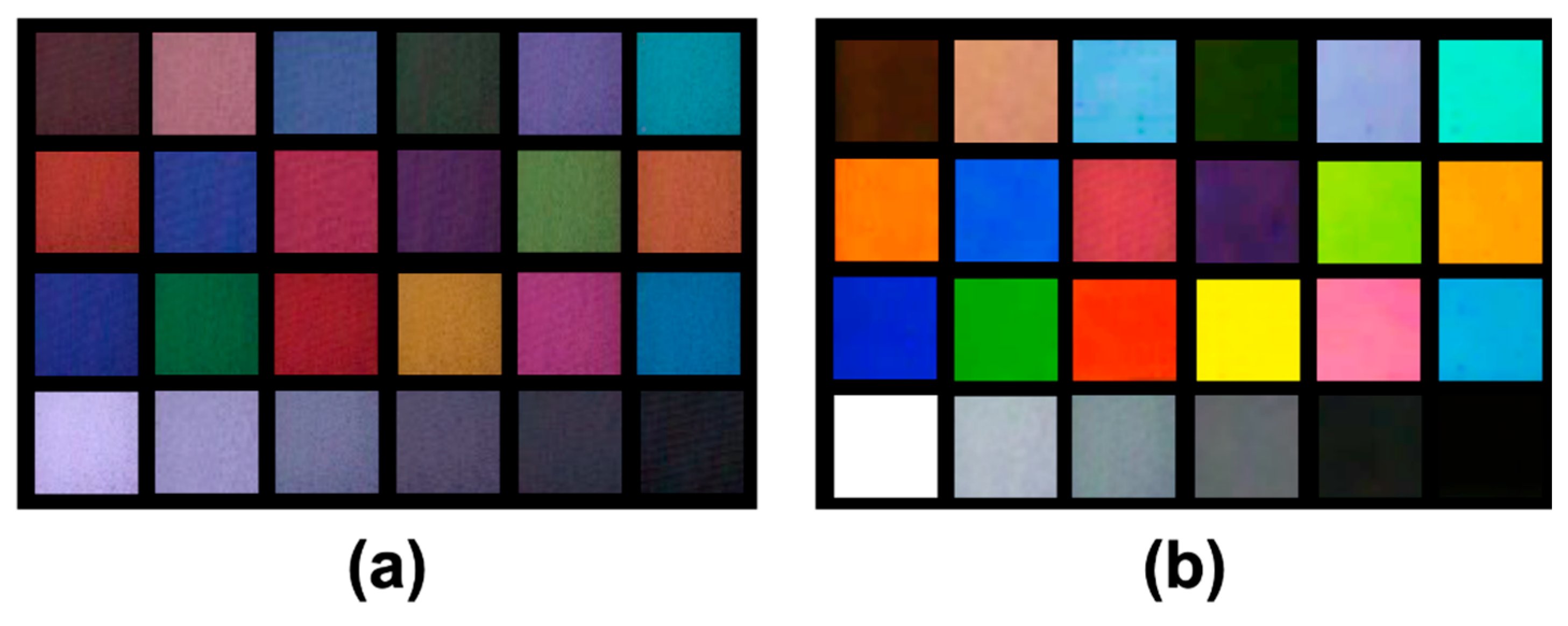

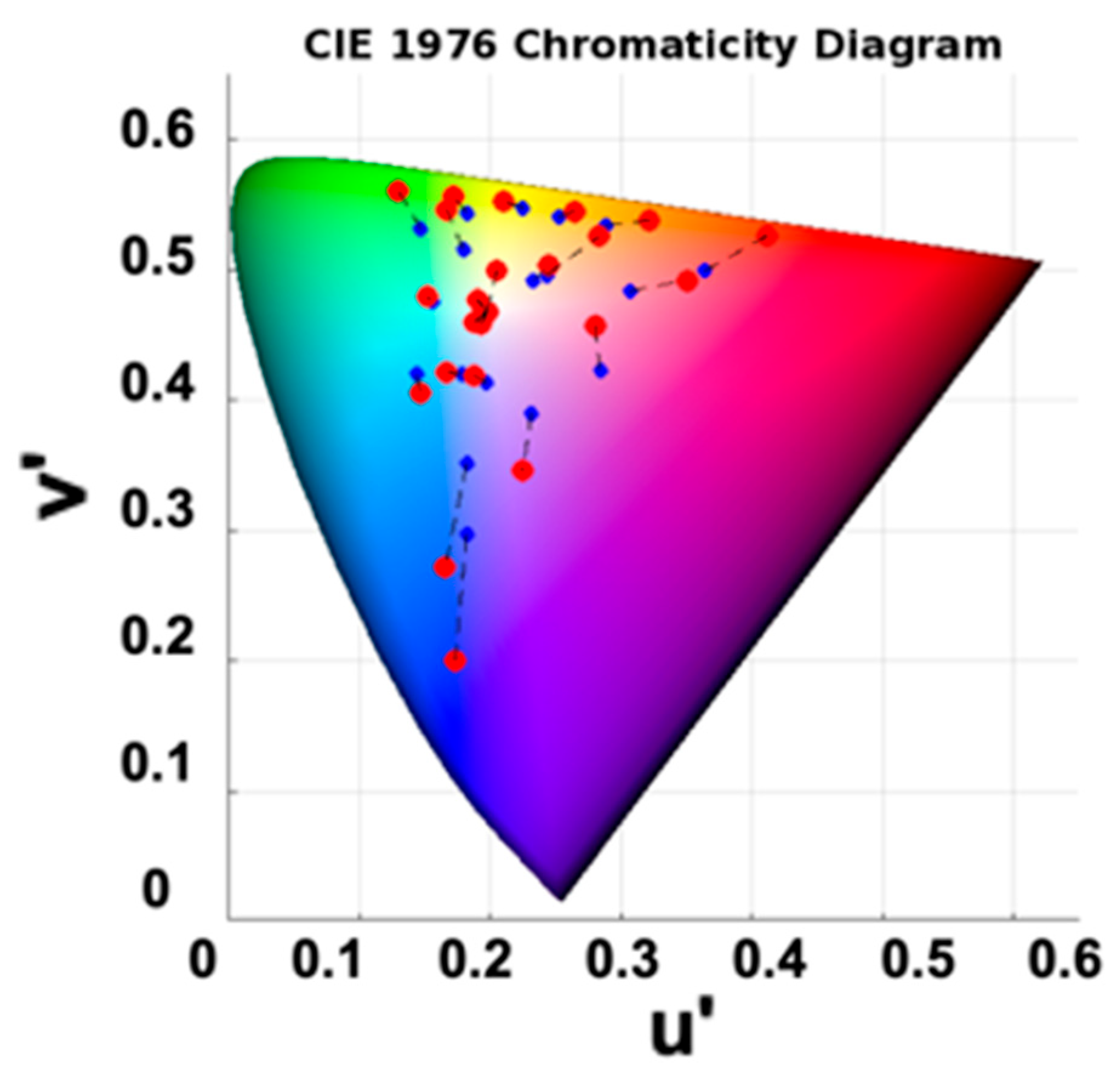

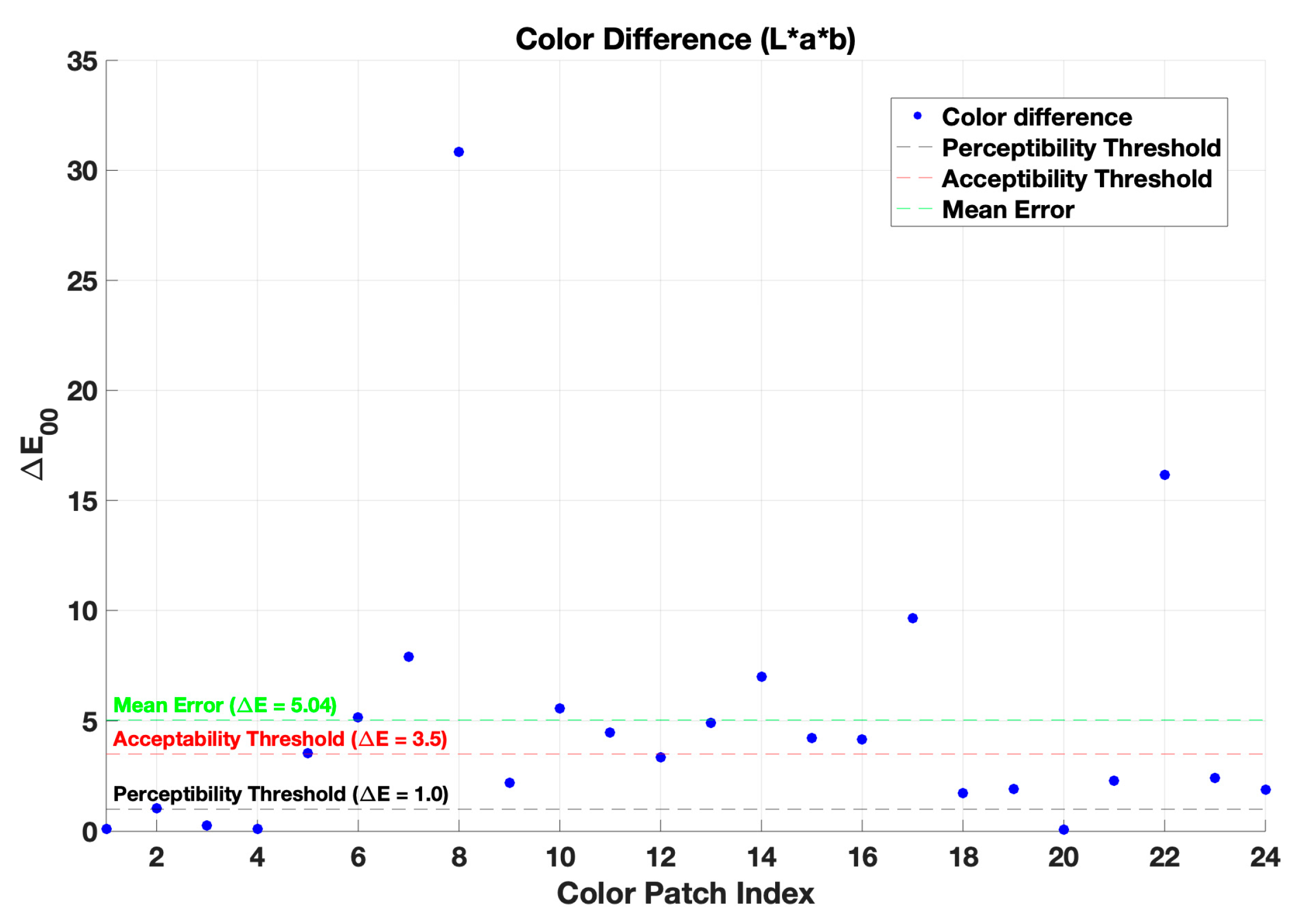

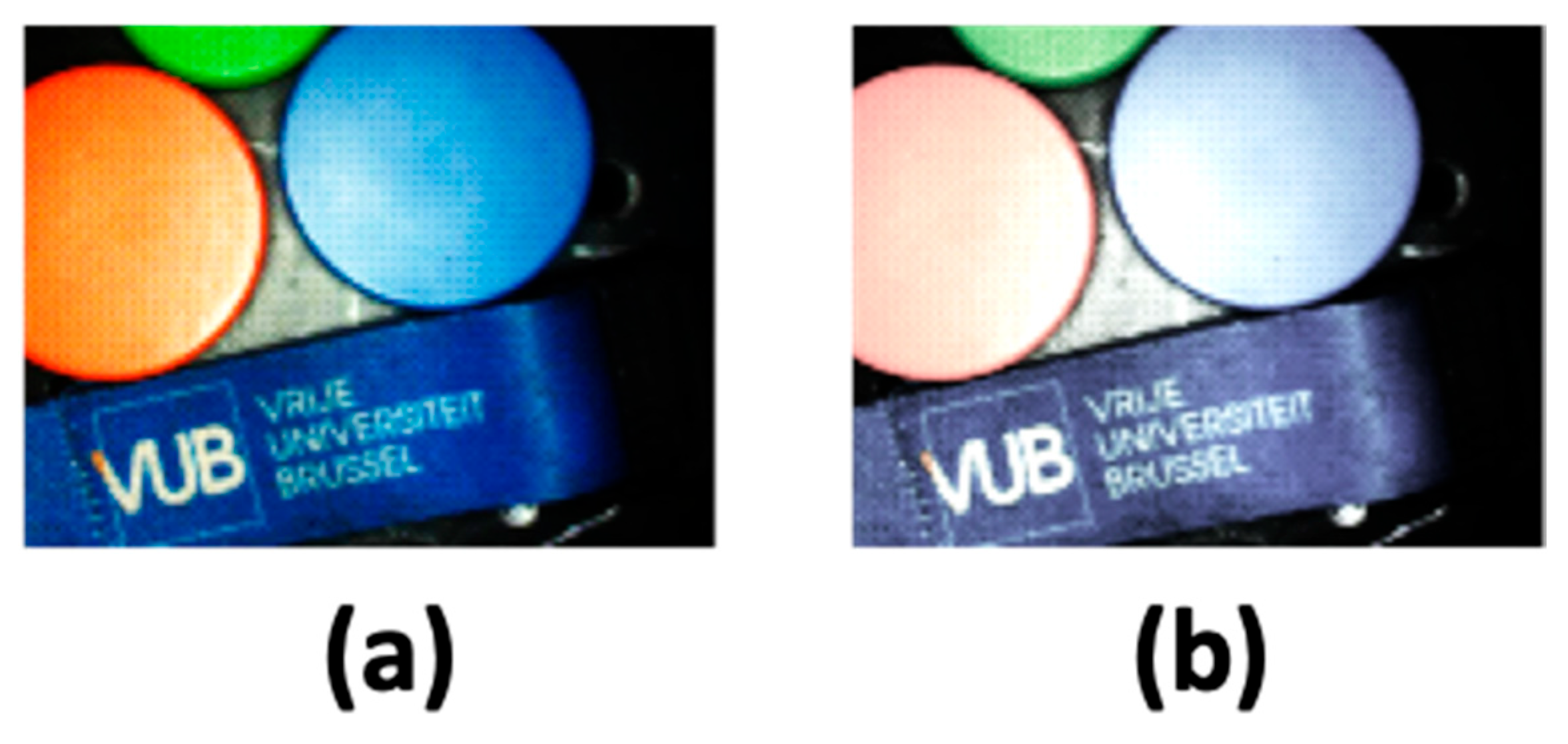

4.1. Color Correction and Evaluation

4.2. Experimental Result

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bortot, B.; Mangogna, A.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Stabile, G.; Ricci, G.; Biffi, S. Image-Guided Cancer Surgery: A Narrative Review on Imaging Modalities and Emerging Nanotechnology Strategies. J Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaafsma, B.E.; Mieog, J.S.D.; Hutteman, M.; Van Der Vorst, J.R.; Kuppen, P.J.K.; Löwik, C.W.G.M.; Frangioni, J.V.; Van De Velde, C.J.H.; Vahrmeijer, A.L. The Clinical Use of Indocyanine Green as a Near-Infrared Fluorescent Contrast Agent for Image-Guided Oncologic Surgery. J Surg Oncol 2011, 104, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Sevick-Muraca, E.M. A Review of Performance of Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging Devices Used in Clinical Studies. Br J Radiol 2015, 88, 20140547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangioni, J. In Vivo Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2003, 7, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissleder, R.; Tung, C.-H.; Mahmood, U.; Bogdanov, A. In Vivo Imaging of Tumors with Protease-Activated near-Infrared Fluorescent Probes. Nat Biotechnol 1999, 17, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntziachristos, V. FLUORESCENCE MOLECULAR IMAGING. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2006, 8, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, C.W.; Gibbs, S. Fluorescence Image-Guided Surgery: A Perspective on Contrast Agent Development. In Proceedings of the Molecular-Guided Surgery: Molecules, Devices, and Applications VI.; SPIE, February 19 2020; Gibbs, S.L., Pogue, B.W., Gioux, S., Eds.; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, J.A.; Franke, D.; Caram, J.R.; Perkinson, C.F.; Saif, M.; Askoxylakis, V.; Datta, M.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R.K.; Bawendi, M.G.; et al. Shortwave Infrared Fluorescence Imaging with the Clinically Approved Near-Infrared Dye Indocyanine Green. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 4465–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.K.; Cho, S.S.; Zeh, R.; Pierce, J.T.; Martinez-Lage, M.; Adappa, N.D.; Palmer, J.N.; Newman, J.G.; Learned, K.O.; White, C.; et al. Folate Receptor Overexpression Can Be Visualized in Real Time during Pituitary Adenoma Endoscopic Transsphenoidal Surgery with Near-Infrared Imaging. J Neurosurg 2018, 129, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, M.J.; Cardona, D.M.; Lazarides, A.L.; Spasojevic, I.; Ferrer, J.M.; Cahill, J.; Lee, C.-L.; Snuderl, M.; Blazer, D.G.; Hwang, E.S.; et al. A Mouse-Human Phase 1 Co-Clinical Trial of a Protease-Activated Fluorescent Probe for Imaging Cancer. Sci Transl Med 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-387-31278-1.

- Petrášek, Z.; Krishnan, M.; Mönch, I.; Schwille, P. Simultaneous Two-Photon Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy and Lifetime Imaging of Dye Molecules in Submicrometer Fluidic Structures. In Proceedings of the Microscopy Research and Technique; Wiley-Liss Inc., 2007; Vol. 70; pp. 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- Akers, W.; Achilefu, S. In Vivo Resolution of Two Near-Infrared Fluorophores by Time-Domain Diffuse Optical Tomagraphy.; Achilefu, S., Bornhop, D.J., Raghavachari, R., Savitsky, A.P., Wachter, R.M., Eds.; 2007; p. 64490H. 8 February.

- Gannot, I.; Ron, I.; Hekmat, F.; Chernomordik, V.; Gandjbakhche, A. Functional Optical Detection Based on PH Dependent Fluorescence Lifetime. Lasers Surg Med 2004, 35, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakache, G.; Yahav, G.; Siloni, G.H.; Barshack, I.; Alon, E.; Wolf, M.; Fixler, D. The Use of Fluorescence Lifetime Technology in Benign and Malignant Thyroid Tissues. J Laryngol Otol 2019, 133, 696–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, R.; Hom, M.E.; van den Berg, N.S.; Lwin, T.M.; Lee, Y.-J.; Prilutskiy, A.; Faquin, W.; Yang, E.; Saladi, S.V.; Varvares, M.A.; et al. First Clinical Results of Fluorescence Lifetime-Enhanced Tumor Imaging Using Receptor-Targeted Fluorescent Probes. Clinical Cancer Research 2022, 28, 2373–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DSouza, A.V.; Lin, H.; Henderson, E.R.; Samkoe, K.S.; Pogue, B.W. Review of Fluorescence Guided Surgery Systems: Identification of Key Performance Capabilities beyond Indocyanine Green Imaging. J Biomed Opt 2016, 21, 080901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, N.; Pacheco, S.; Wang, X.; Liang, R. Single Camera Imaging System for Color and Near-Infrared Fluorescence Image Guided Surgery. Biomed Opt Express 2014, 5, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teranaka, H.; Monno, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Ok, M. Single-Sensor RGB and NIR Image Acquisition: Toward Optimal Performance by Taking Account of CFA Pattern, Demosaicking, and Color Correction. Electronic Imaging 2016, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Dries, T.; Lapauw, T.; Janssen, S.; Sahakian, S.; Lepoutte, T.; Stroet, M.; Hernot, S.; Kuijk, M.; Ingelberts, H. 64×64 Pixel Current-Assisted Photonic Sampler Image Sensor and Camera System for Real-Time Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging. IEEE Sens J 2024, 24, 23729–23737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranian, P.; Nevens, W.W.; Lapauw, T.; Van den Dries, T.; Coosemans, J.; Sahakian, S.; Lepoutte, T.; Jacobs, V.A.; Ingelberts, H.; Kuijk, M. Novel Sequential RGB+NIR Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging with a Single Nanosecond Time-Gated CAPS Camera. In Proceedings of the Advanced Biomedical and Clinical Diagnostic and Surgical Guidance Systems XXII.; Boudoux, C., Tunnell, J.W., Eds.; SPIE, March 13 2024; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Iranian, P.; Lapauw, T.; Van den Dries, T.; Sahakian, S.; Wuts, J.; Jacobs, V.A.; Vandemeulebroucke, J.; Kuijk, M.; Ingelberts, H. Fluorescence Lifetime Endoscopy with a Nanosecond Time-Gated CAPS Camera with IRF-Free Deep Learning Method. Sensors 2025, 25, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballew, R.M.; Demas, J.N. An Error Analysis of the Rapid Lifetime Determination Method for the Evaluation of Single Exponential Decays. Anal Chem 1989, 61, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, D.D.-U. One-Dimensional Deep Learning Architecture for Fast Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2021, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digman, M.A.; Caiolfa, V.R.; Zamai, M.; Gratton, E. The Phasor Approach to Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Analysis. Biophys J 2008, 94, L14–L16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method | CIELAB ∆E00 |

Cross-validation CIELAB ∆E00 |

| Before color correction | 16.23 | --- |

| First-order regression | 5.04 | 7.26 |

| Non-linear regression | 2.12 | 9.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).