Submitted:

14 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

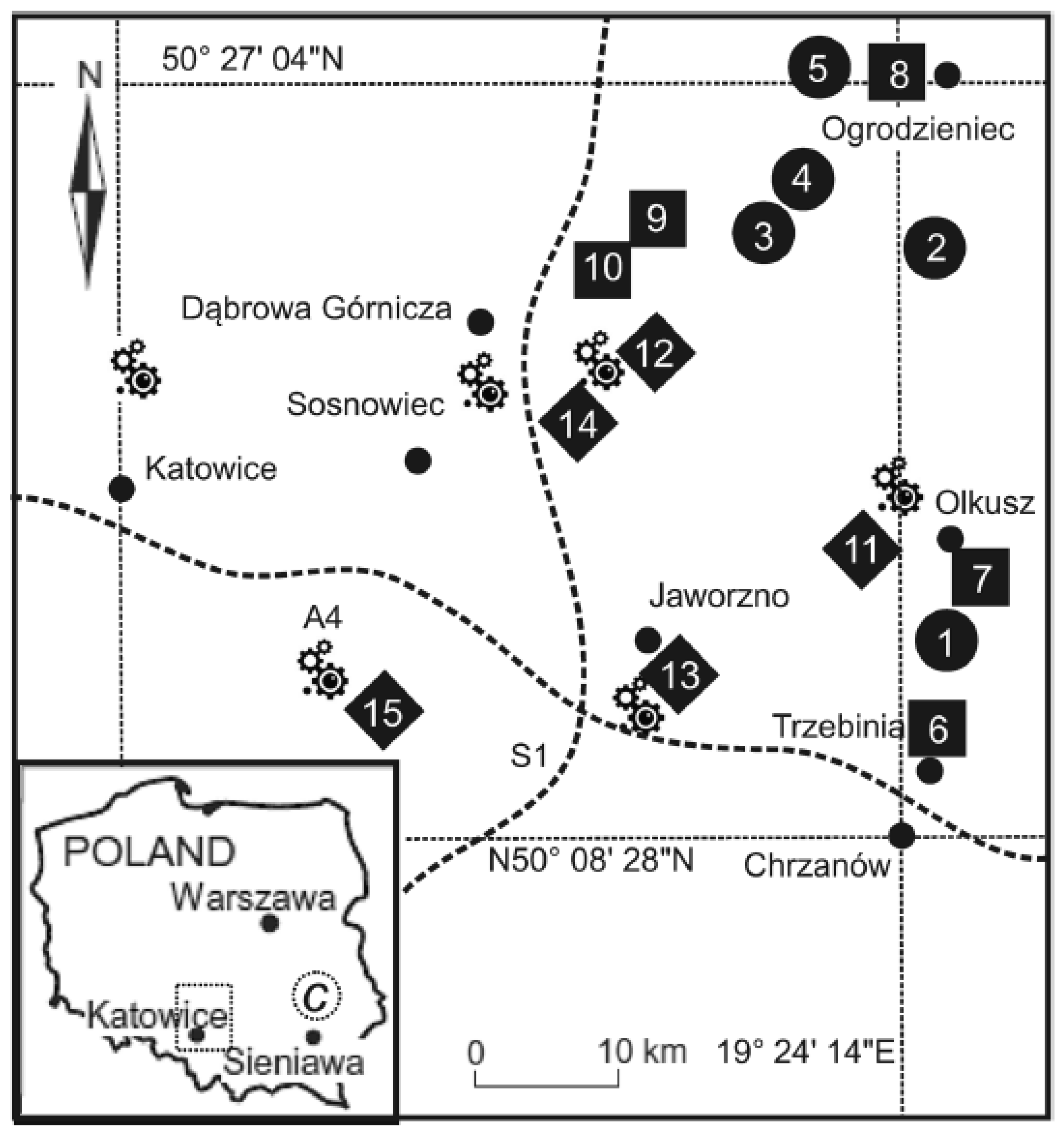

Study Area and Sampling Design

Moss Transplant Preparation and Exposure Conditions

Bulk (Wet) Deposition Sampling

Dry Deposition Sampling

Chemical Analysis of Moss and Deposition Samples

Calculation of Relative Accumulation Factors (RAF)

Data Preprocessing for Machine Learning

Machine-Learning Models and Workflow

Risk Classification Model

Software

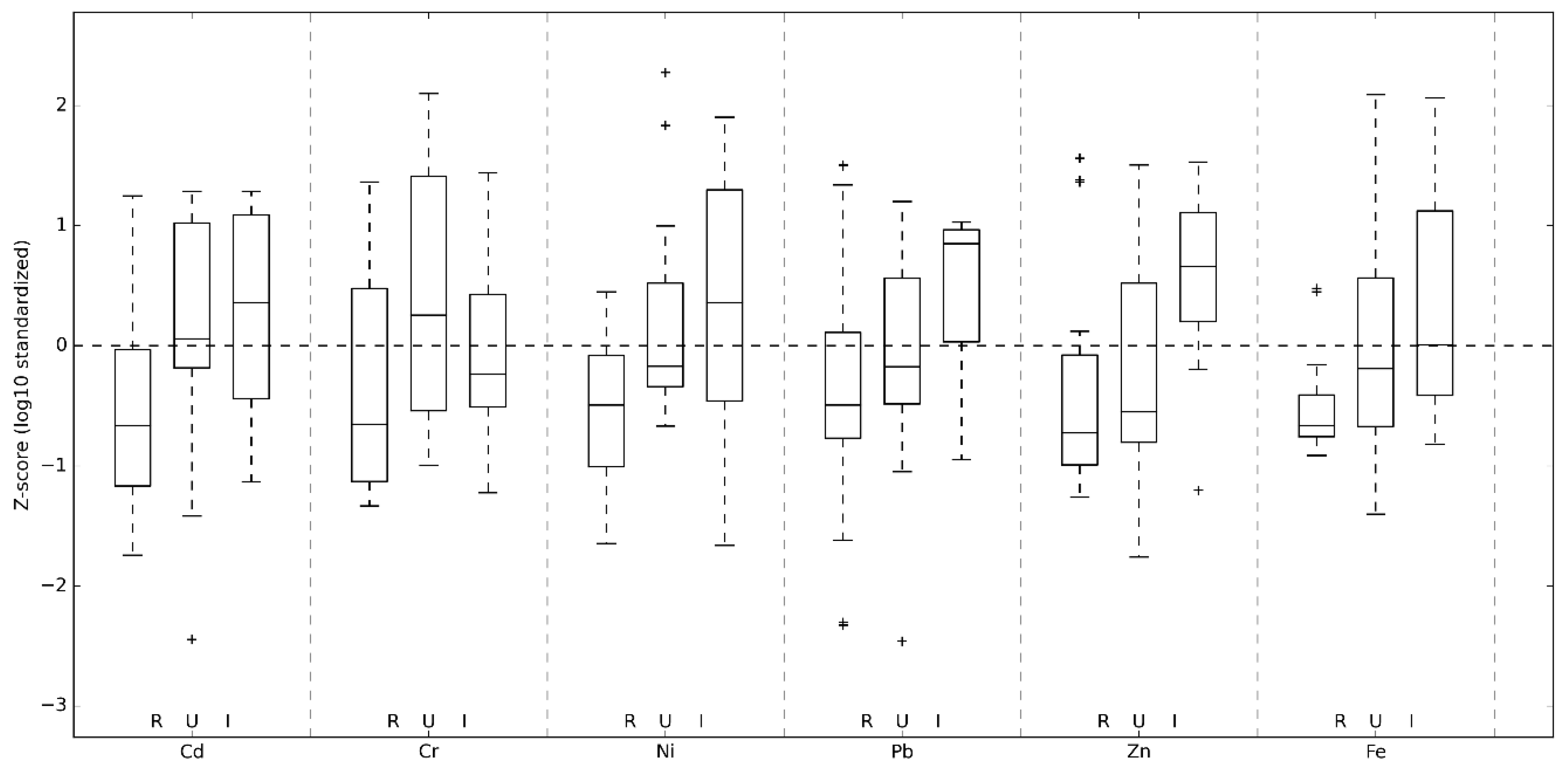

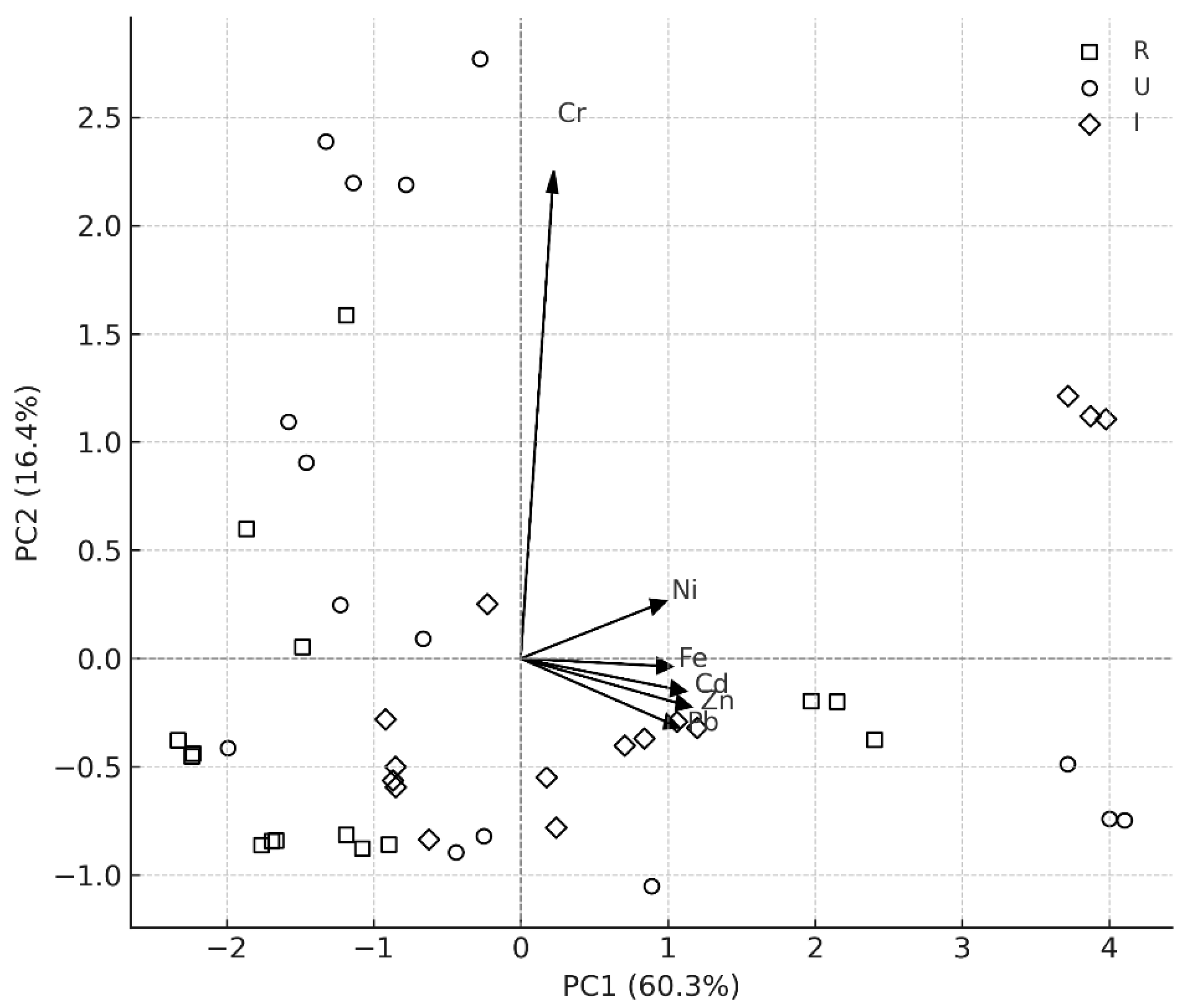

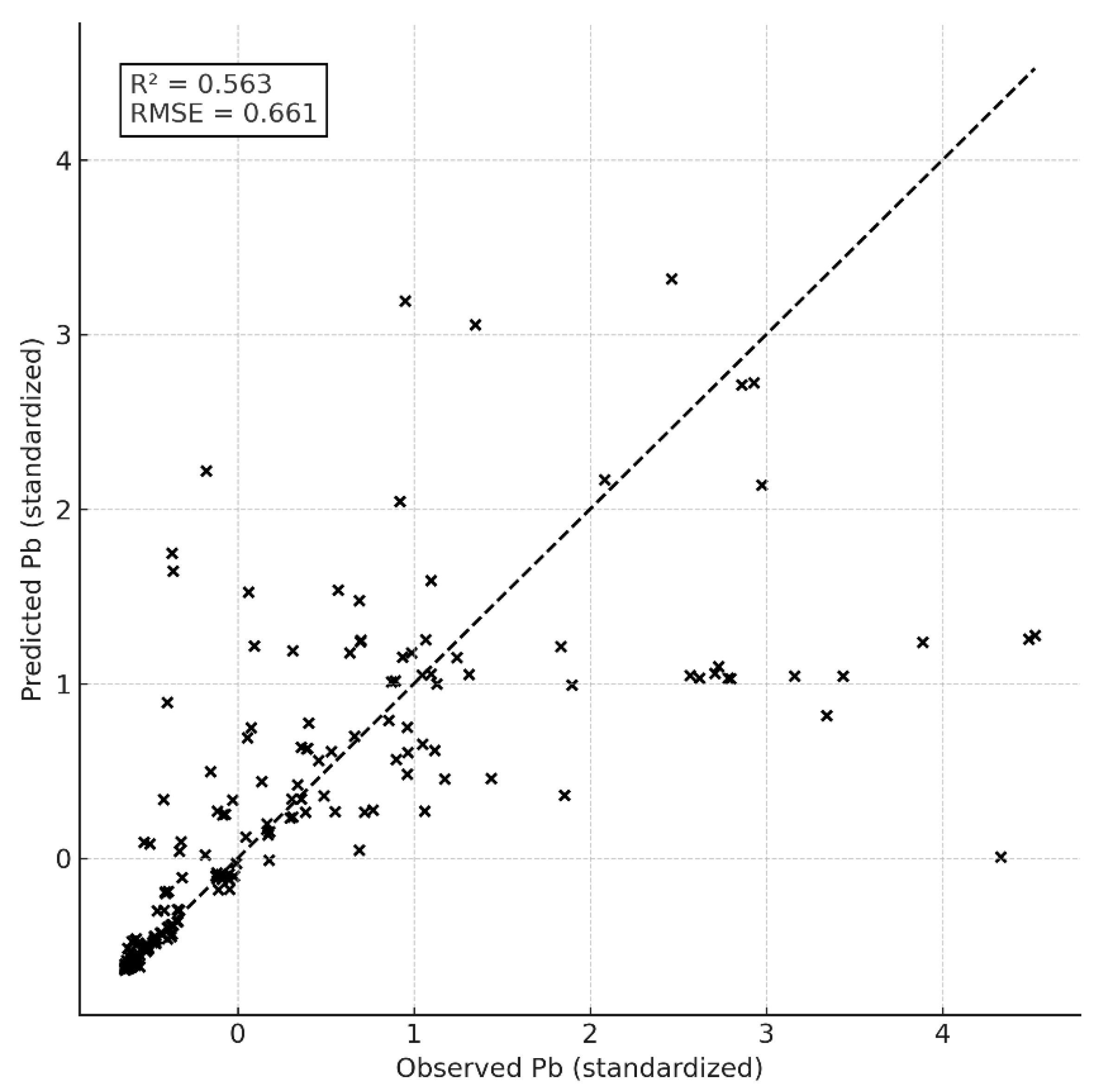

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboal, J.R.; Fernández, J.A.; Boquete, M.T.; Carballeira, A. Is it possible to estimate atmospheric deposition of heavy metals by analysis of terrestrial mosses? Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 6291–6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ares, A.; Aboal, J.R.; Carballeira, A.; Giordano, S.; Adamo, P.; Fernández, J.A. Moss bag biomonitoring: A methodological review. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 432, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aničić, M.; Tasić, M.; Frontasyeva, M.V.; Tomašević, M.; Rajšić, S.; Mijić, Z.; Popović, A. Active moss biomonitoring of trace elements with Sphagnum girgensohnii moss bags in relation to atmospheric bulk deposition in Belgrade, Serbia. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, T.; Røyset, O.; Steinnes, E. Moss (Hylocomium splendens) used as biomonitor of atmospheric trace element deposition: Estimation of uptake efficiencies. Atmos. Environ. 1995, 29, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, T.; Steinnes, E. Use of mosses (Hylocomium splendens and Pleurozium schreberi) as biomonitors of heavy metal deposition: From relative to absolute deposition values. Environ. Pollut. 1997, 98, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boquete, M.T.; Fernández, J.A.; Carballeira, A.; Aboal, J.R. Relationship between trace metal concentrations in the terrestrial moss Pseudoscleropodium purum and in bulk deposition. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 201, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabała, J.; Krupa, P.; Misz-Kennan, M. Heavy metals in mycorrhizal rhizospheres contaminated by Zn–Pb mining and smelting around Olkusz in Southern Poland. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2009, 199, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.A.; Aboal, J.R.; Couto, J.A.; Carballeira, A. Sampling optimization at the sampling-site scale for monitoring atmospheric deposition using moss chemistry. Atmos. Environ. 2002, 36, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2002, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halleraker, J.H.; Reimann, C.; de Caritat, P.; Finne, T.; Kashulina, G.; Niskavaara, H.; Bogatyrev, I. Reliability of moss (Hylocomium splendens and Pleurozium schreberi) as bioindicators of atmospheric chemistry in the Barents region: Interspecies and field duplicate variability. Sci. Total Environ. 1998, 218, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, A.; Zhang, S.; Lin, X.; Norris, P.; da Silva, A. Cloud/precipitation assimilation using the forecast model as a weak constraint. In Proc. Int. Workshop on Assimilation of Satellite Cloud and Precipitation Observations in NWP Models; NOAA: Lansdowne, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosior, G.; Samecka-Cymerman, A.; Brudzińska-Kosior, A. Transplanted moss Hylocomium splendens as a bioaccumulator of trace elements from different categories of sampling sites in the Upper Silesia area (SW Poland): Bulk and dry deposition impact. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2018, 100, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajunen, L.H.J.; Perämäki, P. Spectrochemical Analysis by Atomic Absorption and Emission; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiera, T.; Strzyszcz, Z.; Rachwał, M. Mapping particulate pollution loads using soil magnetometry in urban forests in the Upper Silesia Industrial Region, Poland. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 248, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markert, B.A.; Breure, A.M.; Zechmeister, H.G. Bioindicators and Biomonitoring; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Olszowski, T.; Tomaszewska, B.; Góralna-Włodarczyk, K. Air quality in a non-industrialised area in the typical Polish countryside based on measurements of selected pollutants in immission and deposition phase. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 50, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinnes, E. A critical evaluation of the use of naturally growing moss to monitor the deposition of atmospheric metals. Sci. Total Environ. 1995, 160–161, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinnes, E.; Hanssen, J.E.; Rambæk, J.P.; Vogt, N.B. Atmospheric deposition of trace elements in Norway: Temporal and spatial trends studied by moss analysis. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1994, 74, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodosi, C.; Markaki, Z.; Tselepides, A.; Mihalopoulos, N. The significance of atmospheric inputs of soluble and particulate major and trace metals to the eastern Mediterranean seawater. Mar. Chem. 2010, 120, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretiach, M.; Pittao, E.; Crisafulli, P.; Adamo, P. Influence of exposure sites on trace element enrichment in moss-bags and characterization of particles deposited on the biomonitor surface. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE ICP Vegetation. Heavy Metals in European Mosses: 2000/2001 Survey; Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, University of Wales: Bangor, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| Element | Control (Mean ± SD) | Rural (Mean ± SD) | Urban (Mean ± SD) | Industrial (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.9 |

| Co | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.4 |

| Cr | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 2.3 ± 0.7 |

| Cu | 8.4 ± 1.2 | 9.9 ± 2.4 | 10.5 ± 2.6 | 13.5 ± 3.1 |

| Fe | 557 ± 178 | 1004 ± 324 | 1070 ± 524 | 2396 ± 1404 |

| K | 2939 ± 393 | 3420 ± 689 | 3564 ± 1512 | 3089 ± 404 |

| Mg | 1048 ± 226 | 1764 ± 757 | 1721 ± 675 | 2823 ± 1791 |

| Mn | 582 ± 178 | 384 ± 202 | 539 ± 293 | 473 ± 355 |

| Ni | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 1.7 |

| Pb | 5.9 ± 2.5 | 34 ± 32 | 26 ± 13 | 39 ± 21 |

| V | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 0.6 |

| Zn | 61 ± 7 | 194 ± 158 | 138 ± 65 | 258 ± 139 |

| Element | RAF Rural (Mean ± SD) | RAF Urban (Mean ± SD) | RAF Industrial (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | 2.9 ± 2.7 | 3.1 ± 2.8 | 4.8 ± 2.8 |

| Co | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 2.3 | 2.2 ± 0.6 |

| Cr | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.4 |

| Cu | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.3 |

| Fe | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 2.8 | 3.3 ± 1.4 |

| K | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.1 |

| Mg | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.6 ± 1.9 | 1.7 ± 0.5 |

| Mn | −0.3 ± 0.3 | −0.1 ± 0.4 | −0.2 ± 0.7 |

| Ni | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 0.4 |

| Pb | 4.8 ± 5.5 | 3.4 ± 3.7 | 5.6 ± 2.6 |

| V | −0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.4 |

| Zn | 2.9 ± 2.6 | 1.3 ± 2.4 | 3.2 ± 1.5 |

| Element | Control | Rural | Urban | Industrial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.1 ± 0.7 |

| Co | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.2 |

| Cr | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| Cu | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 5 ± 6 | 7 ± 6 | 8 ± 2 |

| Fe | 18 ± 1 | 15 ± 29 | 6 ± 6 | 30 ± 30 |

| Mn | 38 ± 1 | 50 ± 50 | 30 ± 40 | 40 ± 20 |

| Ni | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 2 ± 2 | 2 ± 2 | 4 ± 3 |

| Pb | 2 ± 0.1 | 4 ± 3 | 2 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 |

| Zn | 53 ± 5 | 90 ± 100 | 70 ± 80 | 140 ± 110 |

| Element | Control | Rural | Urban | Industrial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.7 |

| Co | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.4 |

| Cr | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 2.9 ± 1.4 |

| Cu | 6.7 ± 0.3 | 7.7 ± 2.4 | 10.1 ± 3.7 | 17 ± 7.5 |

| Fe | 441 ± 19 | 358 ± 104 | 378 ± 289 | 666 ± 186 |

| Mn | 16.7 ± 1.6 | 12.8 ± 7.7 | 15.7 ± 13 | 5.9 ± 5.6 |

| Ni | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 2.5 | 5.9 ± 4.5 |

| Pb | 15.3 ± 1.4 | 15.2 ± 6.3 | 21.2 ± 16 | 40 ± 18 |

| Zn | 31 ± 1.2 | 25 ± 22 | 35 ± 33 | 50 ± 29 |

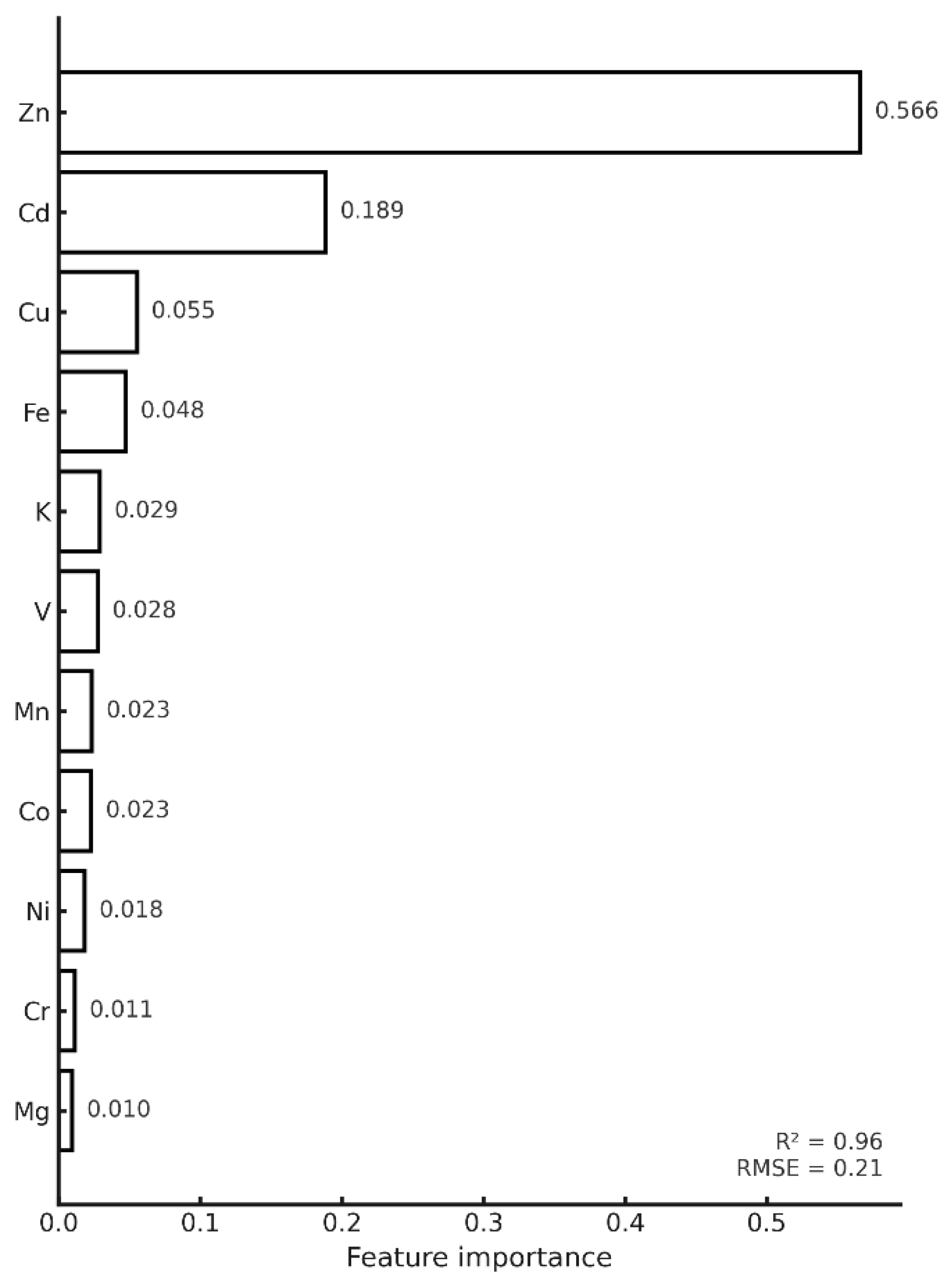

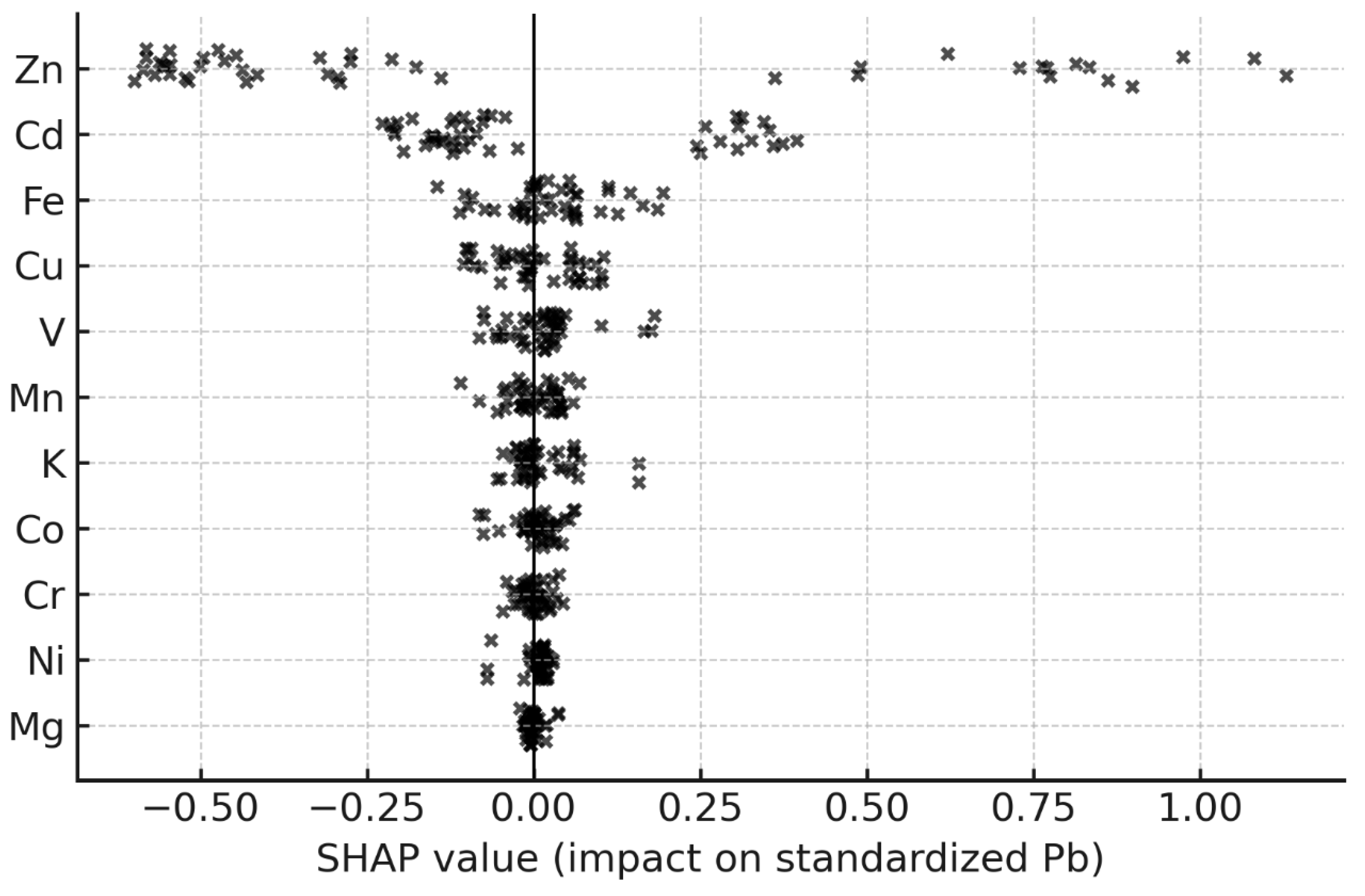

| Target Metal | Model | R² | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Random Forest | 0.91 | low | low |

| Cd | Random Forest | 0.88 | low | low |

| Zn | Gradient Boosting | 0.86 | moderate | low |

| Ni | Gradient Boosting | 0.82 | moderate | moderate |

| Cr | PCA + GB | 0.78 | moderate | moderate |

| Fe | Random Forest | 0.84 | moderate | moderate |

| Rank | Feature | Influence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dry deposition load | Very high |

| 2 | Site category (I/U/R) | High |

| 3 | RAF value | High |

| 4 | Bulk deposition | Moderate |

| 5 | Moss initial concentration | Moderate |

| 6 | Environmental metadata (distance, land use) | Low–moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).