1. Introduction: Transits of Venus and Mercury and the Solar Diameter Measures

The transits of Venus occur in couples in June (descending node) separated by 8 years, after 122 years since the couple in December (ascending node); 105 years after that another June couple will occur. It happened that in the XX century no transits of Venus occurred across the Sun as seen from the Earth. Their observations were realized under whatever meteorological conditions, being –the Venus transits- more than a lifetime event, and for Mercury somewhat similar: Then these lifetime observations were realized under whatever meteorological conditions. For Mercury the situation is somewhat similar: in a lifetime “they can be counted on the finger of a hand”, unlike the total eclipses, observable yearly along their paths travelling worldwide.

A transit of Mercury occurs about 13 times each century, with two configurations: at descending node in May and at ascending node in November (Sigismondi, et al. 2004).

The transits of Venus have been observed only since 1639, and they occurred in 1761, 1769, 1874, 1882, 2004 and 2012. The states of the art of astronomy at their times were different and we describe them briefly, as well as the goal of the 2012 measures: a precise measure of the photospheric solar diameter. We describe briefly the experimental apparatus set up to record the ingress and the egress of Venus at Huairou Solar Observing Station, and the method to treat the data. The chords intersecting the solar limb with the planetary disk have been fitted with a parabola, in order to overcome the black-drop effect, which occurs at the internal contacts. The value of the solar diameter confirmed within 0.09” of accuracy the variation of the solar diameter of +0.33” (Sigismondi, 2018; Sigismondi, 2013) with respect to the IAU optical standard solar radius fixed in 1891 (Auwers, 1891) as 959.63”at 1 Astronomical Unit.1

The solar diameter variations along the centuries are of primary importance for the comprehension of the solar variability, being that phenomenon out of the explanation within the standard solar model, and being the observations with very high accuracy so difficult along the history of telescopic observations, even in recent times.

2. The Transits of Mercury and Venus Along the History

The transit of a planet in front of the Sun forces the geometrical model of the solar system. Only Mercury and Venus can do it, as inner planets. The passage of Mercury on the Sun was invoked (Einhnard, c. 817–36) as early as in the time of Charlemagne, to explain a dark spot seen on the Sun for seven days.2 The Sun, at that time, was then considered at the third geocentric sphere, even with a foundation on the Sacred Scriptures.3 The sphere of the Sun, in the Biblical culture, was outer to the Mercury and the Moon’s sphere.

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) in publishing his ephemerides Tabulae Rudolphinae (Kepler, 1627), forecasted the transits of Mercury for 1631 (Kepler, 1629) and a miss of the Venus’ one for 1639. The predictions of these transits should have been accurate in space and time within the solar disk (±16′) and the transit’s duration (±3 hr), and verified.

Pierre Gassendi on 7 November 1631 observed firstly a transit of Mercury. The dimension of Mercury in front of the solar disk was decidedly smaller than he expected to see (Gassendi, 1631; Nature 1931). Jeremy Horrocks (Hevelius, 1662), improving the calculation of Kepler, and his friend William Crabtree observed on 4 December 1639 the beginning of the transit of Venus across the Sun, verifying its angular dimension and the corrections of Horrocks to the ephemerides of Kepler. (Nature, 1900)

The other Venus’ transits have been observed at different stages of the history of modern astronomy (Sigismondi, 2015): if Celestial Mechanics was the focus in 1639 Venus transit, and the accurate measure of the Astronomical Unit for 1761-69 and 1874-82 transits. The planetary atmosphere in 1761 and 2012 and the Earth’s atmosphere and black-drop optics in 1769 and 2004 were also under scrutiny. The sunlight reduction during the transits of 2004 and 2012 was exploited to better understand extrasolar planetary transits observational issues, having the details of the solar surface fully available, unlike the stars (Sigismondi, et al. 2015). Our interest into observing the transits of 2004 and 2012 was the accurate measure of the solar diameter, through the comparison between the observed timing and the calculated ephemerides.

3. The Planetary Transits and the Solar Diameter: Kinematic and Black-Drop Effect

For Venus’ transits the duration τ of the contacts τ= t2-t1 = t4-t3 is longer, about 12 minutes, than the contacts of the transits of Mercury (2 minutes). The maximum amplitude of the chord in Venus’ transits is 58” in June transits and 63” in December ones. For Mercury transits the chord is as large as 12” in May and 10” in November’s transits. The angular velocity of Venus and Mercury during the transits is typically 0.07”/s; the daytime seeing is 2” in average conditions, therefore the transit of Venus has been a very good opportunity to exploit a planetary transit across the Sun to measure accurately the solar diameter.

Being capable to define the transit’s contacts with a precision of a second, as the observers of the XVIII century expected to be, a precision of 0.07” in the determination of the solar limb position was possible. Because of the black-drop optical phenomenon these determinations remained more uncertain both with naked-eye observations and with instrumental recording, and a difference of several seconds were reported (Cook and Green, 1771).

By means of the extrapolation to zero of the chords described by Venus with the solar limb, through a parabolic fit, we eliminated the influence of the black-drop on our measurements. Since the black-drop is due to an interplay between the solar limb darkening and the point-spread function of the telescope, this effect is also occurring on spacebased measurements (Pasachoff, et al., 2005).

4. Clearness of the Atmosphere and Solar Diameter Measurements: Case Studies at the Pinhole-Meridian Line of St. Maria degli Angeli (1702)

The meteorological conditions during the contacts of the Mercury transits were taken into account by Wittmann (Wittmann, 1973) who recalled also some observations of sunspots undergoing black-drop effect, during their occultation by the Moon’s limb. Since twenty-three transits of Mercury have been used to demonstrate the absence of variations of the solar diameter from 1631 to 1973 (Shapiro, 1980), it is reliable to have included some cloudy or foggy transits, since their observing opportunity was unique and it was compulsory to observe in any case. There may be situations with hazy atmosphere in which the ingress/egress phases have been well discernable and the solar diameter was under-estimated.

The effect of a foggy day on the perceived solar image reduces its apparent diameter, either by naked eye or by defining the limb of the Sun by the inflexion point of the radial profile of intensity.

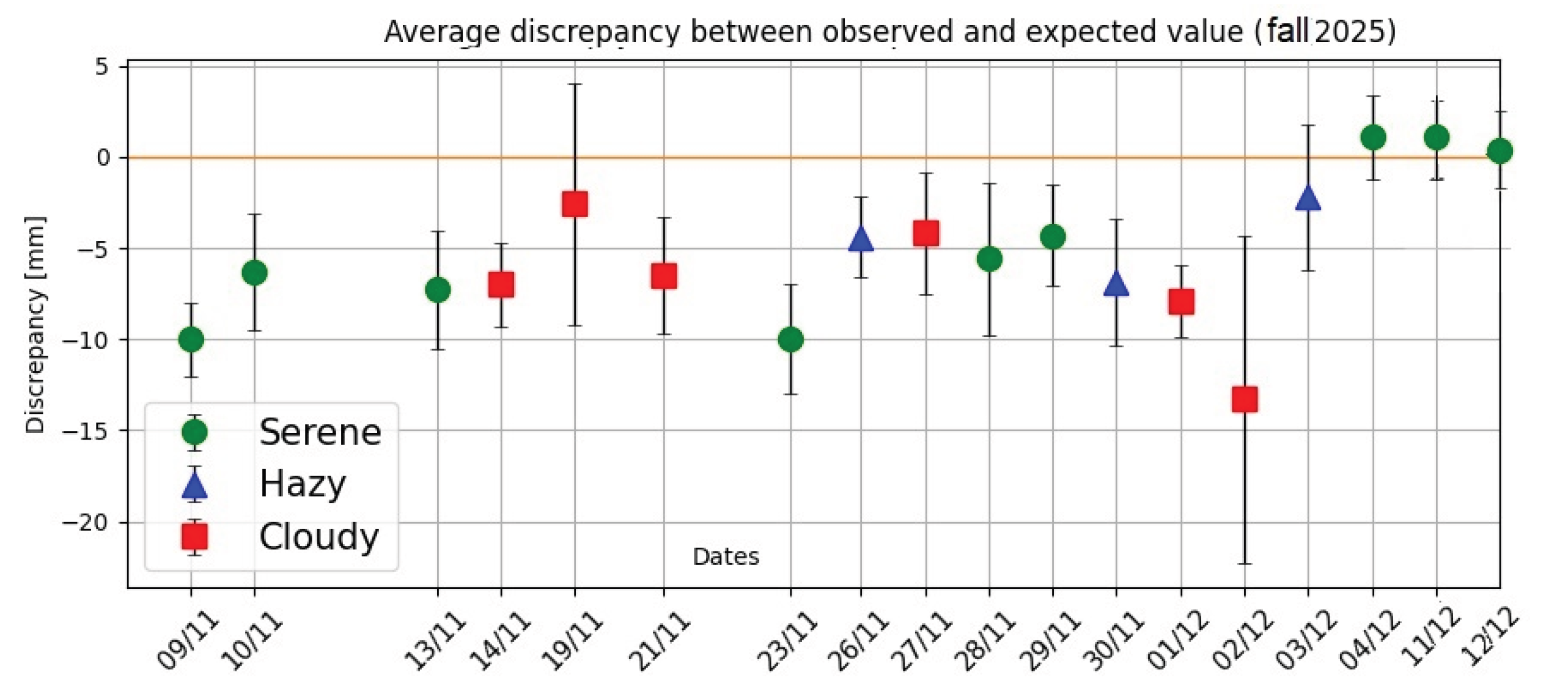

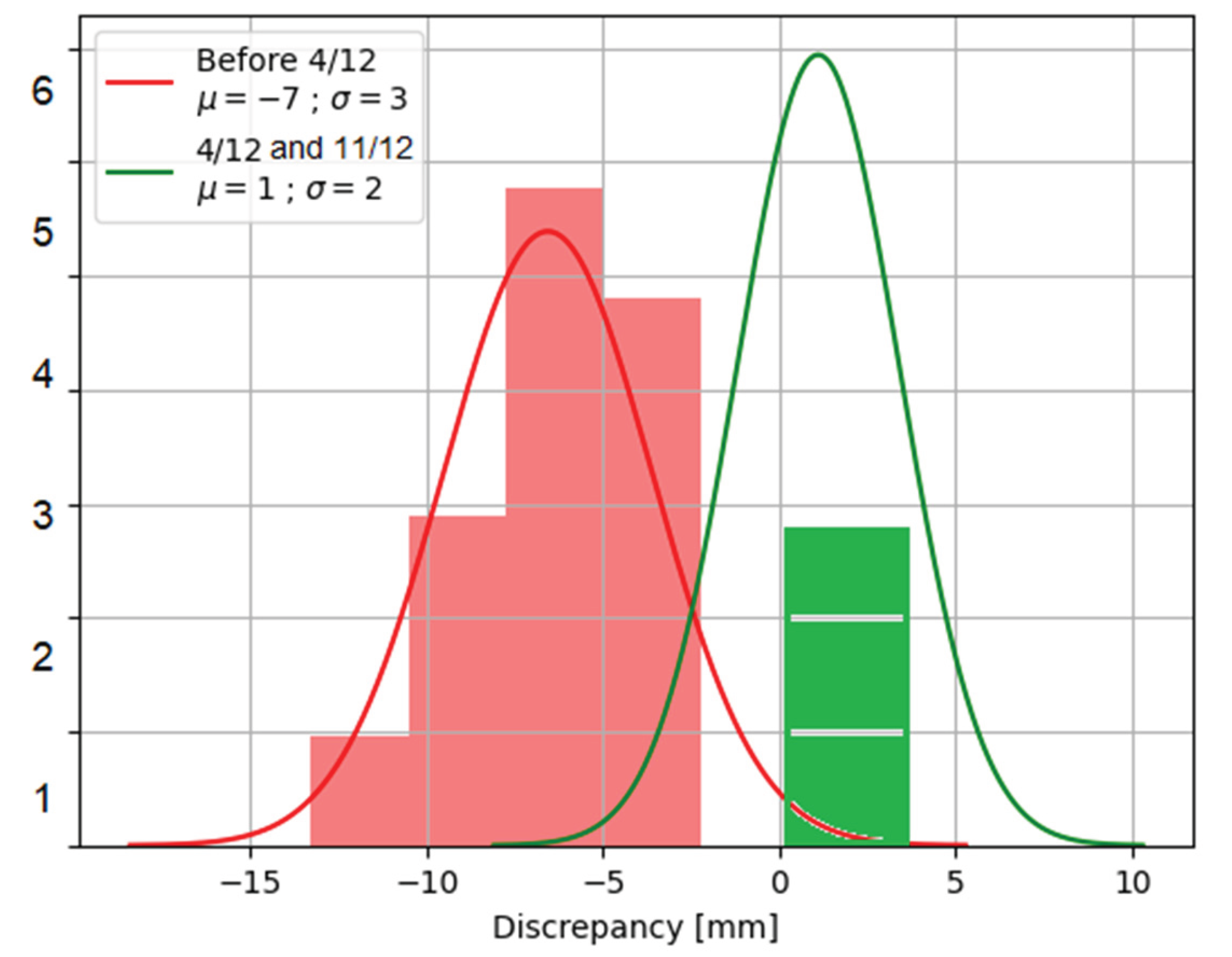

An experiment to study the influence of clouds’ veils to the solar image has been conducted at the Meridian Line of St. Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri in Rome in 2025 (Sigismondi, Brucato and Andreasi-Bassi, 2025). A new set of measures in November and December 2025, with the largest images available (

Figure 1, with the observer’s scale), projected on the white marbles of meridian line, is here presented.

The meridian line of the Basilica of St. Maria degli Angeli in Rome is a giant pinhole-camera built in 1701-1702 to measure accurately the altitude and the dimension of the solar image formed on the 45-m meridian line, with astrometric purposes (Sigismondi, 2025).

Cloudy days (with the Sun through thick veil, but the limbs are discernable), veiled and serene days have been considered, to have consistent data with all the planetary transits. The average meridian diameters of 10 measures per day over the white marbles are reported with their standard deviations. The best cases with σ<2 mm have been on sunny days 4, 11 and 12 December 2025, due to a relatively low local air turbulence. The pinhole meridian dimension corresponded in these cases with 24” or 12 mm at 47 m and at an angle of projection of 26° and 25° (Sun’s meridian altitude), with a characteristic diffraction amplitude of 8”.

The limbs of the Sun appeared red with these optimal conditions (

Figure 1 right), because the red light is much deviated by diffraction through the pinhole, than the other spectral components. The cloudy measures of the diameter are generally smaller than the ones made in clear, serene days, but also the turbulent ones are smaller than the steady ones, in agreement with the simulations described by (Wittmann, 1973).

In general, the air turbulence reduces the measured diameter in all cases. The effective pinhole (its meridian diameter) changes from 14.7 mm to 11.4 mm, and the solar diameter ranged from 730 to 1085 mm. In

Figure 2 the data are normalized to 1000 mm of meridian solar diameter. The projected meridian diameter of the pinhole, ranges from 39” to 24”. The diffraction through such dimension in white light is respectively 6.8” and 8”. The averaged errorbars represented in

Figure 2, correspond to 6.3”±1.5”, so that all measures are made near the pinhole’s optical diffraction limit, regardless of the conditions of the sky. But there is a general diminution of the measured diameters with respect to the calculated ones, excepted in very clear days.

Serene days correspond with a larger measured diameter, while the heavier is the thickness of the clouds’ veil the smaller is the measured diameter. The errorbars represent the standard deviations of the sets of 10 daily measures, made under various contrasts of the image. In addition to the meteo conditions the lights inside the Basilica were open during the transits of 14, 19, 23, 30 November and 4 December, worsing the contrast of the image. The hazy data correspond to the presence of the 22° halo around the Sun.

4 In

Figure 3 we compare the discrepancies with the expected value in good seeing and contrast conditions, with worse observing conditions.

A clouds’ veil acts as a filter cutting the outermost parts of the solar diameter below the visibility threshold. Similar conditions occurred during some historical planetary transits: the planet becomes discernable only when the ingress already started, because both the solar limb and the planet appear less sharp.

5. The Black Drop and the Solar Diameter

This phenomenon was claimed during the transit of 1769 observed in Tahiti, at “Cape Venus” contemporarily by the Captain Cook and the astronomer Charles Green. Their contact times were different, and the difference was attributed to the black drop phenomenon (Cook and Green, 1771). J. M. Pasachoff (Pasachoff el al., 2005) explained duly the optical origin of the black drop, due to an interplay between the rapidly changing limb darkening function of the Sun and the point spread function of the telescope.

In order to avoid the black drop we decided to measure the length of the chord that Venus and the solar limb describe during the ingress/egress phases, and to extrapolate the time in which such chord is zero, finding t0 and t4.

The interplay of the point-spread function of the telescope with the atmospheric haze, which also has a point-spread function producing halos around the Sun, tends to delay t0 and to anticipate t4, with the net result of a reduction of the perceived solar diameter.

The atmospheric conditions especially at the beginning of the transit of Venus on 6 June 2012 in Huairou Solar Observing Station were strongly hazy (

Figure 4).

In other historical transits, similar or milder conditions may have been concurrent to the four contact timings, evaluated both by eyes and through video.

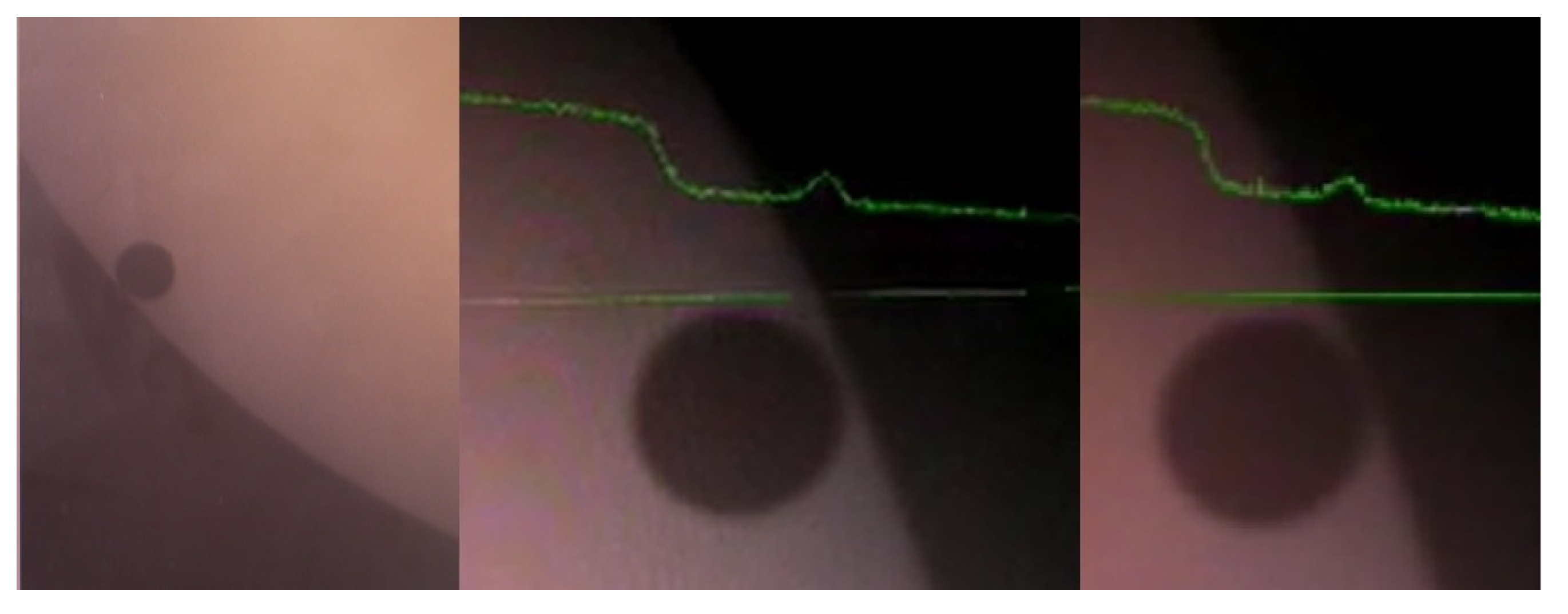

6. The Reduction of the Apparent Dimension of the Transiting Planet by Haze

The haze is produced by regular water droplets through Mie scattering. Often the atmospheric halos at 22° and coronae around the Sun are associated to this kind of scattering. The action on the solar image is a reduction of the contrast, and a reduction of the diameter (more inward position of the inflexion point of the limb darkening function of the Sun). The silouhette of the planet, is reduced, and it is difficult to observe (

Figure 5).

6.1. Mercury Transits

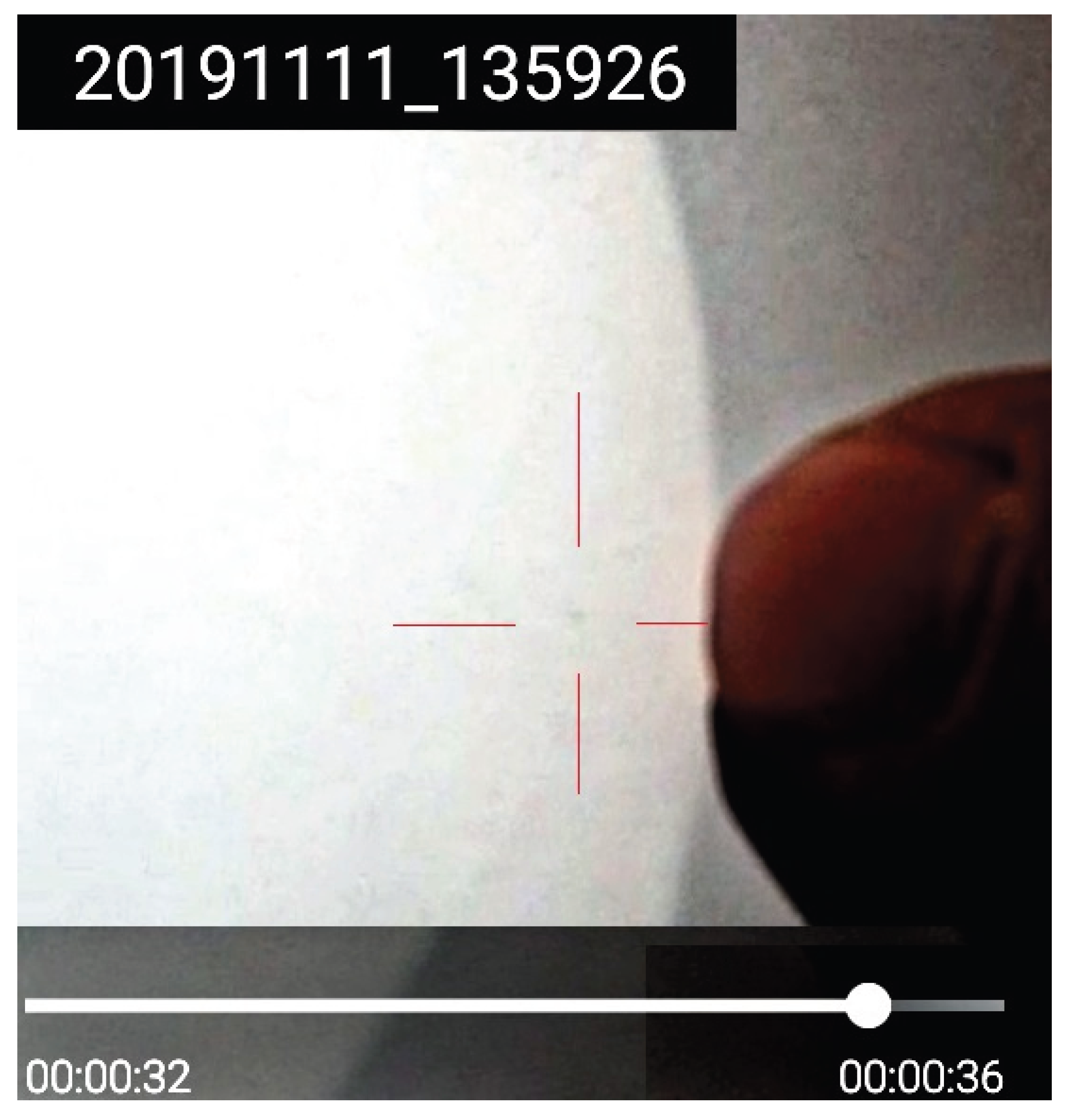

We experienced this phenomenon on 11 November 2019 when Mercury transited across the Sun. We observed it in ICRANet center of Pescara.

5 All Italy was under clouds during that transit, while in Pescara the weather was veiled, and the planet appeared with great difficulty on the projection’s screen (

Figure 4). The telescope used was a refractor 100/1000 without filters.

Similarly with a 70/350 reflecting Newtonian telescope was used to project the image of the Sun at the ingress of Mercury on 9 May 2016 at ICRA terrace in Rome-Sapienza University.6 The ingress, in both cases was visible only after 107 seconds (Sigismondi and Altafi, 2016). The meteo in Rome was absolutely clear, but the ambient luminosity was heavy to spot the ingress of Mercury in the projection, but enough to discern the 5” separation between two sunspots.

These two observations may well represent the difficulties of similar observations experienced in the past centuries, to obtain perfect timings of external and internal contacts.

6.2. Sunspots

The alfa-type sunspots are good tests for planetary transits, if we do not consider the penumbra; the difference with planetary transits is their surface brightness. The sunspots’ umbrae are at 4000 °K, and the penumbrae are clearer, nevertheless they are not dark as the profile of a transiting planet. Mercury in 2016 was clearly darker than the other sunspots, even if smaller. No sunspots were visible in 2019, at solar minimum. Nevertheless the sunspots allow to fix the focus of a telescope better than using only the solar limb. Moreover the solar limb is not sharp by definition.

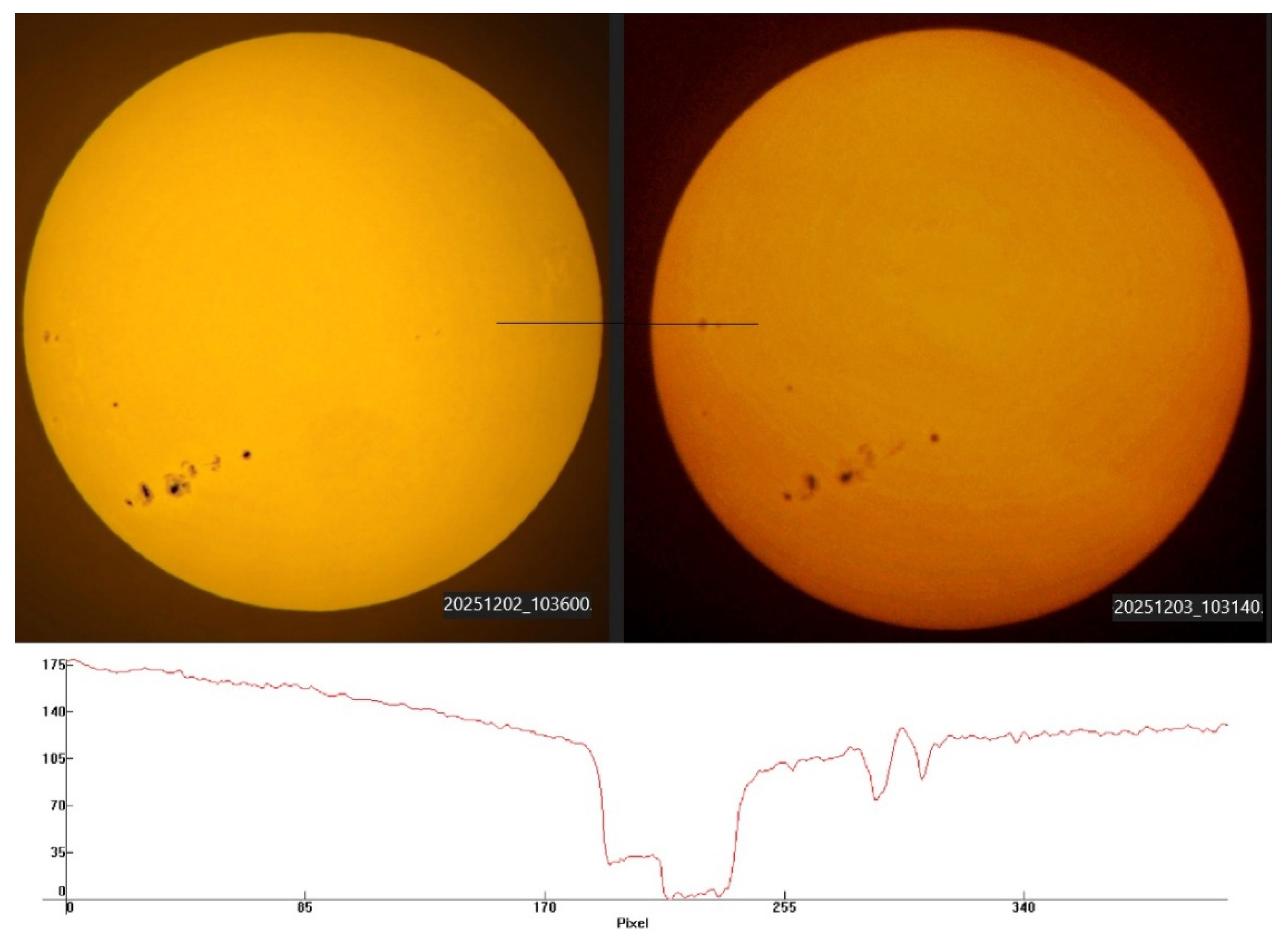

The images of the Sun taken in clear and hazy day (

Figure 6) show the blurring of the image with the Mie scattering.

The weather of 3 December 2025 was veiled and the view of the faculae at the same telescope was completely lost; the sunspots appear generally smaller than the previous day, loosing the visibility of their penumbrae.

Mercury’s diameter at the November transit was 9.95”, while in May 12.08”. Here the largest sunspots sizes are 50”, comparable with Venus (57.80”) in transit.

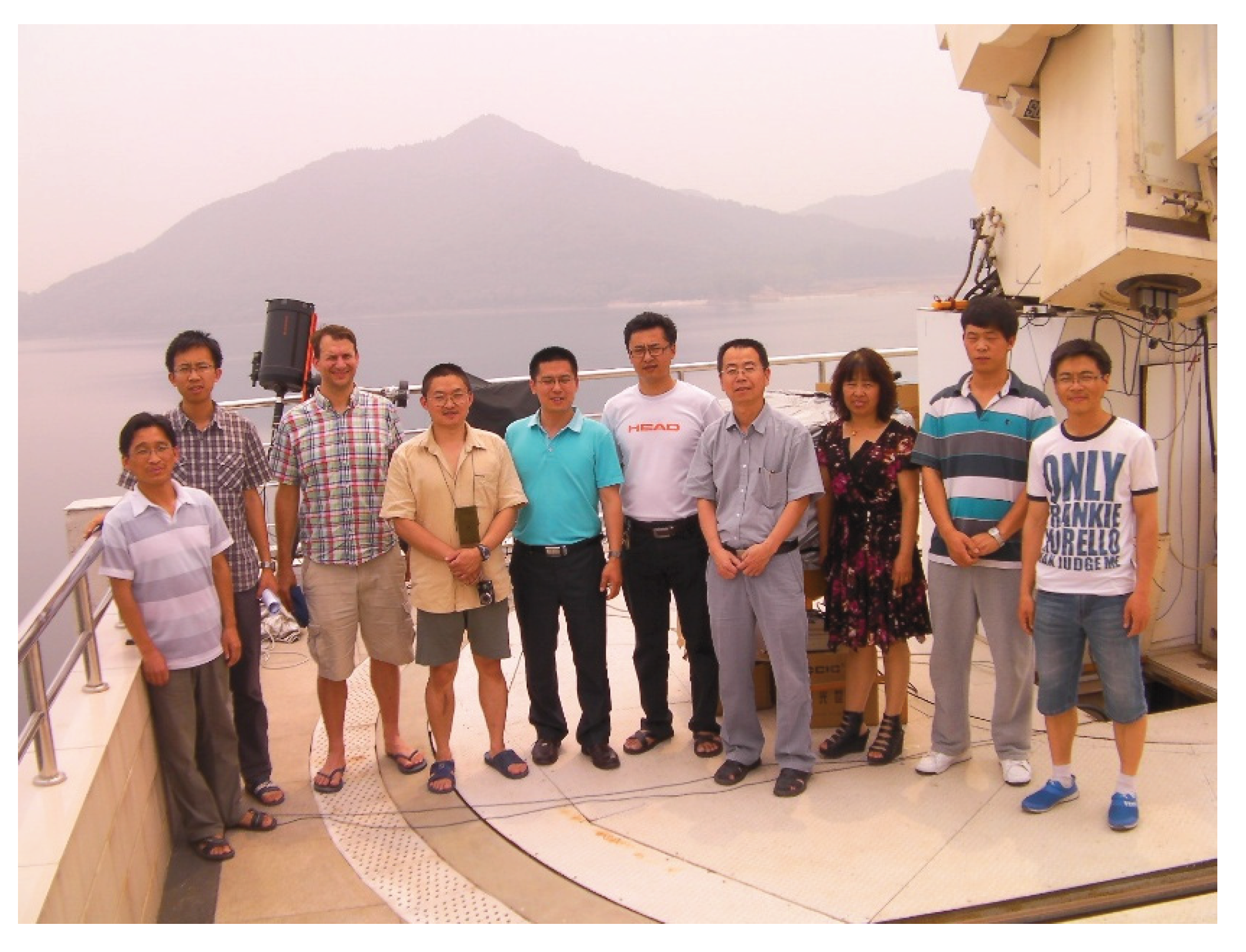

7. The Transit of Venus of 2012 at Huairou

The Venus transit was complete in China, from the ingress to the egress and this is the reason why we took agreement with the Huairou Solar Observing Station since from 2011. ICRANet sponsored this observing mission, as part of the activities of its Observatory. The staff (

Figure 7) of the Huairou Solar Observing Station (

Figure 8) helped this historical enterprise.

We removed the mylar filter (

Figure 9 ) from the 28 cm—11” Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope prepared for the ingress, because the Multi Channel Solar Telescope

7 could not point the Sun at sunrise, when the transit started.

The ingress (

Figure 10 left) was recorded without filter for the unexpected remarkable sky opacity.

The planetary disk (

Figure 11 right) was much darker than the umbra of the sunspots.

8. Conclusions

The transit of Venus is a lifetime event: a couple in 8 years spaced by more than a century. Exactly one century from now, 8 December 2125, there will occur the second transit of the 22nd century. The transit of Venus offered many opportunities for research as optical tests, simulation of exoplanet transits with real data, measuring of the solar diameter, measures of the Venus aureola omesosphere) by analyzing the forward scattering of sunlight on its mesosphere (Tanga, et al. 2012).

Analizing the main issues of the 2012 transit observed at Huairou Solar Observing Station, we reconsidered the black-drop phenomen under heavy sky opacity.

The diameter of the Sun obtained with the Venus transit observed in Huairou (Xie, et al. 2012) showed an enlargement of the standard 959.63” solar radius at 1 AU of +0.33”± 0.009”, consistent with the forthcoming measures from total eclipses (Lamy, et al. 2015); (Quaglia, et al. 2021).

The fact that the measure was performed under a hazy sky enforces the thesis that the solar diameter is increased, since we have confirmed with the data obtained at the historical meridian line of Santa Maria degli Angeli, that hazy meteorological conditions reduce the perceived solar diameter, according to the simulations of Wittmann (1973).

Author Contributions

C. S. conceived the structure of the paper and wrote it, A. B. contributed to the statistical analysis; X. W. and W. X. organized the observation at Huairou caring of the logistic and the instrumentation.

Acknowledgments

Costantino Sigismondi acknowledges his Institutions: ICRANet and Galileo Ferraris Institute of Rome, in particular prof. Remo Ruffini and prof. Marina Pacetti, for their support for this unique event.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 |

The solar radius as astronomical constant has been revised in IAU (2015), in order to bridge helio- and asteroseismological studies. It is a nominal value useful for stellar astrophysics, but the variations of the solar radius, ascertained with many experiments and observations, continue to remain unexplained by the solar standard model. |

| 2 |

Einhard, Vita Caroli, Chapter 32et in sole macula quaedamatricolorisseptemdierumspatio visa (transl. And in the sun, a certain spot of black color was seen over the course of seven days) written circa 817-836 AD. |

| 3 |

St. Paul in the Acts of the Apostoles reports to have been kept, in flesh or spirit, “he does not know” at the third heaven. The art representation of that fragment of the scripture is within the sunlight (Basilica of St. Paul outside the Walls, Rome). |

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

References

- C. Sigismondi, Francesca Binaglia, Laura Bellitto, Paolo Colona, Donatello Di Carlo, Rita Fioravanti, Pietro Oliva, Sabina Fiorenzi, Pietro Alessandro Giustini, TRANSITI ECLISSI ED OCCULTAZIONI TRA LA MINERVA ED IL COLLEGIO ROMANO evento organizzato da Costantino Sigismondi in occasione dello storico transito di Venere sul Sole 8 giugno 2004, Roma, Biblioteca Nazionale Casanatense, 8 Giugno 2004. Available online: (accessed on 11 december 2025) https://accademiadellestelle.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Saros-Transito-di-Venere-alla-Casanatense.pdf.

- C. Sigismondi, Transits of Venus 2004 and 2012 and solar diameter from ground: Method, results and perspectives for Mercury transit of 2016, Proc. of the Fourteenth Marcel Grossmann Meeting On Recent Developments in Theoretical and Experimental General Relativity, Astrophysics, and Relativistic Field Theories, held 12-18 July 2015 in Rome, Italy. Edited by Massimo Bianchi, Robert T Jantzen and Remo Ruffini. Published by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., 2018. ISBN #9789813226609, pp. 3688-3693 (2018).

- C. Sigismondi, Solar diameter with 2012 Venus Transit, proc. of the Fourth French-Chinese meeting on Solar Physics Understanding Solar Activity: Advances and Challenges, 15–18 November, 2011 Nice, France;. (2013) Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1201.4011 (accessed on 11 december 2025). [CrossRef]

- A. Auwers, A., “Der Sonnendurchmesser und der Venusdurchmesser nach den Beobachtungen an den Heliometern der deutschen Venus-Expeditionen”, Astronomische Nachrichten, 128, Issue 20, 361 (1891).

- Einhard, Vita Caroli Magni. 32 (c. 817–36). Available online: https://thelatinlibrary.com/ein.html (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Kepler, J., Tabulae Rudolphinae, J. Sauri, Ulmae (1627).

- Kepler, J., De raris mirisque Anni 1631 Phaenomenis which included an admonitio ad astronomos, J. Bartschio, Lipsiae (1629).

- Gassendi, P., Mercvrivs in sole visvs, et Venvs invisa Parisiis, anno 1631 pro voto, & admonitione Keppleri, Parisiis, (1631).

- Gassendi and the Transit of Mercury. Nature 128, 787–788 (1931). [CrossRef]

- J. Hevelius, Venus in Sole Observata Liverpoliae A Jeremia Horroxio Anno 1639 24 Novembris, Styl. Jul. Delineata vero à Johanne Hevelio, S. Reiniger, Gedani (1662).

- Jeremiah Horrocks and the Transit of Venus . Nature 62, 257–258 (1900). [CrossRef]

- C. Sigismondi, Transits of Venus and the Astronomical Unit: Four Centuries of Increasing Precision, Proc. of the Thirteenth Marcel Grossmann Meeting: On Recent Developments in Theoretical and Experimental General Relativity, Astrophysics and Relativistic Field Theories—Proceedings of the MG13 Meeting on General Relativity (in 3 Volumes). Edited by ROSQUIST KJELL ET AL. Published by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., 2015. ISBN #9789814623995, pp. 2064-2066 (2015).

- C. Sigismondi, X. Wang, P. Rocher, E. Reis-Neto, Venus Transits: History and Opportunities for Planetary, Solar and Gravitational Physics, Proc. of the Thirteenth Marcel Grossmann Meeting: On Recent Developments in Theoretical and Experimental General Relativity, Astrophysics and Relativistic Field Theories—Proceedings of the MG13 Meeting on General Relativity (in 3 Volumes). Edited by ROSQUIST KJELL ET AL. Published by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., 2015. ISBN #9789814623995, pp. 2369-2371 (2015).

- Cook, J. and C. Green, ‘Observations made at King George Island, in the South Seas’ by Charles Green and James Cook (1771). Available online: https://makingscience.royalsociety.org/items/l-and-p_5_257/paper-observations-made-at-king-george-island-in-the-south-seas-by-charles-green-and-james-cook?page=1 (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Pasachoff, J. M., G. Schneider and L. Golub, The black-drop explained, proc. IAU Colloquium 196, W. Kurtz ed. Cambridge University Press (2005). Available online: https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/2005IAUCo.196..242P (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Wittmann, A., Numerical Simulation of the Mercury Transit Black Drop Phenomenon, Astronomy and Astrophysics, Vol. 31, p. 239 (1974). Available online: https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/1974A%26A....31..239W (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Shapiro, I.I., 1980. Is the Sun Shrinking? Science, 208:51–53.

- Sigismondi, C., A. Brucato and G. Andreasi-Bassi, Solar Astrometry in Rome at the End of the Maunder Minimum, Universe 2025, 11(6), 186; (2025). [CrossRef]

- Sigismondi, C., Science with historical instruments: the Clementine Gnomon in St. Maria degli Angeli in Rome, BALMER 3, 35-42 (2025) Available online: https://www.icra.it/BALMER/2025/Balm-3-2025-Sigismondi-Gnomon-35-42.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Sigismondi, C. and H. Altafi, Visual and Hα measurements of solar diameter of 9 may 2016 mercury transit, Gerbertus 9, 13-20 (2016). https://www.icra.it/gerbertus/2018/Gerb-11-2018-SigismondiAltafi-Mercury-13-20.pdf (access 12 Dec. 2025).

- Tanga, P., et al., The Venus Twilight Experiment: Probing The Mesosphere In 2004 And 2012, American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting #44, id.508.07 (2012).

- Xie, W., C. Sigismondi, X. Wang and P. Tanga, Venus transit, aureole and solar diameter, Solar and Astrophysical Dynamos and Magnetic Activity, Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, IAU Symposium, Volume 294, pp. 485-486 (2013). Available online: https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/2013IAUS..294..485X (access 11 December 2025).

- P. Lamy, et al., A Novel Technique for Measuring the Solar Radius from Eclipse Light Curves—Results for 2010, 2012, 2013, and 2015, Solar Physics 290, 2617 (2015).

- L. Quaglia, et al., Estimation of the Eclipse Solar Radius by Flash Spectrum Video Analysis Ap J S 256, 36 (2021) (link) (accessed on 11 December 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).