Introduction

Individually wearable “force fields” have long been the domain of science fiction. However, the concept of using directed energy and active interception for defense originated in mid-twentieth-century military research, notably during the Cold War era of reactive armor development [

1]. In the following decades, point-defense systems, which detect, track, and neutralize incoming projectiles in real time, have evolved from large vehicle- or ship-mounted configurations into sophisticated, autonomous systems integrated into modern defense infrastructure. These systems (e.g., naval close-in weapon systems and active protection systems for armored vehicles) are optimized for intercepting macroscopic threats, including missiles, rockets, and artillery shells [

2,

3,

4]. However, their principles suggest potential adaptation to smaller-scale, human-centered protection systems that can respond to high-velocity, short-range, ballistic or impact hazards [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

The Active Neutralization of Celeritous Impacts by Lateral Expulsion (ANCILE) system is an early prototype exploring this concept. Constructed from open-source, commercially available hardware and software, the ANCILE system demonstrates the feasibility of a wearable active ballistic interception system. The shoulder-mounted configuration employs a closed-loop control scheme that integrates camera-based visual detection with rapid-response actuation. Upon detecting an inbound projectile, the device deploys a compressed-air launcher to project a Kevlar shield along the predicted impact vector, deflecting or dissipating kinetic energy before impact. This proof-of-concept platform establishes a foundation for the miniaturization and refinement of personal active-defense technology, with applications in military, industrial, and high-risk operational contexts.

Background

Point-Defense Systems

The concept of individual force fields, popularized in Frank Herbert’s

Dune (1965), introduced a speculative defensive technology capable of selectively blocking projectiles traveling faster than approximately 9 cm/s [

12]. Although purely fictional, this concept anticipated real-world innovations in active and reactive protection technology. Since the early Cold War, military engineers have developed increasingly sophisticated systems to shield armored vehicles from kinetic and chemical energy threats [

1,

13]. For instance, reactive armor employs explosive layers that detonate outward upon impact, neutralizing or deflecting the penetrating jet of shaped-charge warheads [

13]. Building on these principles, active protection systems emerged to detect, track, and intercept incoming munitions using radar sensors and countermeasure projectiles, providing dynamic protection that augments traditional steel and composite armor [

2,

3,

4].

Researchers have conducted parallel research into electromagnetic, laser, and electric field-based defenses to apply rapid energy projection to disrupt or deflect threats without physical contact [

2,

13,

14]. However, to date, the extreme power demands and limitations of compact, mobile energy sources have confined such concepts primarily to experimental phases. At the systems level, naval vessels and fixed installations have employed analogous point-defense technology (e.g., radar-guided close-in weapon systems) to engage incoming missiles, artillery shells, and drones before impact [

2]. Although highly effective, these systems rely on a substantial power-generation and stabilization infrastructure that remains infeasible for dismounted infantry applications. Therefore, individual soldiers continue to depend predominantly on passive ballistic protection, ranging from Kevlar-based vests to cutting-edge composite body armor, to mitigate the effects of small-arms fire and fragmentation [

15,

16,

17]. Despite persistent exploration of personal electromagnetic or plasma shielding, the engineering challenges of energy density, reaction time, and portability remain principal obstacles to realizing a true “individual forcefield” in the foreseeable future [

1].

Consumer Technology

In civilian applications, as in military contexts, the evolution of individual personal protective equipment (PPE) has focused on passive defenses: mechanical barriers (e.g., helmets, face shields, and ballistic fabrics) designed to absorb or deflect external forces [

18]. These systems rely on material science advancements rather than dynamic interaction with threats. However, the emergence of portable directed-energy technology has prompted the examination of the role of these systems in creating a responsive interface between the human body and its environment. An evolving area of research explores their potential to generate controlled tactile stimuli, leading to novel forms of haptic feedback that simulate physical contact or impact without direct mechanical coupling. Several actuation modalities have been demonstrated, most notably pneumatic, acoustic, and optical actuation systems capable of delivering discernible impulses via the air or radiation pressure [

19,

20].

A well-documented example of pneumatic haptic feedback is Disney Research’s AIREAL (known as AirTap), which employs vortex-ring propulsion to deliver brief, low-energy tactile sensations at a distance [

19,

20,

21]. The mechanism involves toroidal air pulses generated by a controlled diaphragm that could convey spatially localized feedback to a user’s skin [

19,

22]. Similar systems have appeared in interactive entertainment, training simulators, and virtual environments, reinforcing the value of mid-air haptic effects in enhancing immersion [

20,

23]. Parallel research in acoustic actuation has focused on using ultrasound phased arrays to produce focused pressure points, enabling touch perception without physical contact [

20]. Optical or laser-based systems have also demonstrated momentum transfer sufficient to trigger tactile sensations, typically through photon pressure or localized thermal gradients [

1].

Despite these advancements, such technology remains constrained regarding range and energy-transfer capacity. Energy dissipation in air, beam divergence, and safety limitations restrict operation to low-force interactions, making such systems unsuitable for defensive or protective applications. Some experimental systems have attempted to overcome these limits by incorporating aerosolized, combustible, or particulate payloads into pneumatic vortices to increase mass and energy density, although this approach introduces complexities in control, safety, and reproducibility [

22,

24,

25]. Achieving individualized active protection, where the PPE senses an impending ballistic or high-energy threat and intercepts or neutralizes it, requires an integrated network of high-speed sensors, predictive algorithms, and compact interception mechanisms. Even low-energy lasers igniting combustible aerosols add unpredictability where consistency is required [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. This transition from passive to active PPE parallels the broader shift from static defense to dynamic survivability engineering, a frontier in which sensing, computation, and energy delivery must converge according to strict temporal and ergonomic constraints.

Ballistic Interception

Individualized action protection systems represent a developing frontier in applied defense engineering, with direct implications for military and civilian safety applications [

32]. Although environmental and operational requirements differ between these domains, the underlying physics of projectile interception remain focused on ballistic dynamics. In the military context, projectile motion stability is critical in determining the effective range, impact precision, and kinetic efficiency of a weapon system [

33,

34]. Rifled barrels, aerodynamic shaping, and rotational stabilization reduce yaw, precession, and drag, ensuring that the projectile maintains a predictable, stable trajectory over long distances [

35]. In contrast, civilian, disaster, or industrial scenarios typically involve unintended or accidental projectiles (e.g., bolts, fragments, or shards) that are launched unpredictably during mechanical failures, explosions, or high-energy tool discharges [

18,

36,

37]. These objects rarely follow a stable ballistic path; instead, they exhibit chaotic motion dominated by an asymmetric mass distribution and nonuniform aerodynamic loading [

37].

Computational simulations and wind-tunnel experiments performed on thin-walled shells have demonstrated that even marginal lateral forces (on the order of a few newtons) can induce significant trajectory deviation [

38]. Such disturbances reduce accuracy by introducing rapid angular drift, neutralizing the ballistic stability initially imparted by spin or shaping [

18,

39]. Destabilizing a conventional projectile requires applying corrective forces comparable to or greater than the Coriolis terms governing two-dimensional (2D) lateral motion. Commercial sensors could potentially detect and respond to firearm bullets, given the specific calibration [

40]. The scalability of this principle to smaller calibers, including 5.56 or 9 mm rounds, suggests a theoretical pathway for developing interception systems to deflect or degrade projectile momentum via controlled micro-actuation or induced, localized turbulence [

4,

11,

41].

If a wearable system could rapidly detect an incoming projectile, compute its trajectory in real time, and deploy a mechanical or electromagnetic countermeasure, it could feasibly neutralize high-velocity rifle rounds and slower, erratically moving industrial debris. Even commercial sensors could potentially detect conventional ballistics [

42]. Given that thin Kevlar laminates can dissipate sufficient kinetic energy to halt smaller projectiles, coupling such passive materials with active sensing and actuation layers presents a promising design approach. The integration of radar, lidar, or high-speed optical sensors would allow the system to anticipate impact vectors within milliseconds, expanding the individual protection from passive resistance to active defense [

40,

41]. This convergence of real-time detection, dynamic response, and scalable material science could define the next generation of individualized protective technology for application in combat theaters and high-risk industrial environments.

Methods

Overview

The ANCILE active-interception module employs a pneumatic actuation mechanism driven by compressed-air reservoirs, selected for their high power density and rapid-response characteristics. Stepper motors that provide fine angular resolution and synchronized motion control complement this module, allowing the turret to reposition and respond with the interception system within milliseconds. The interception interface comprises a lightweight Kevlar sail engineered for high tensile strength and energy absorption while maintaining an exceptionally low mass-to-area ratio [

17]. This system implementation enables the effective deflection or dissipation of kinetic energy from incoming projectiles while ensuring that the overall platform remains compact and wearable.

Mounting configurations include shoulder, helmet, and backpack integrations, providing adjustable coverage angles and adaptable ergonomic balance. The closed-loop control algorithms dynamically fuse visual feedback and actuator position data to ensure continuous alignment between the detection and interception subsystems [

38,

43,

44]. The result is a highly responsive, autonomous protection unit that compensates for wearer movement and environmental variability while maintaining a reliable interception probability across a broad range of engagement scenarios.

The ANCILE device is a closed-loop, active-interception system intended for individual use. The system employs camera-based object tracking to detect threats and moves a turret to engage them. The system applies compressed air as its primary actuation method and employs coordinated stepper-motor positioning to aim its interception mechanism rapidly. Two high-speed global-shutter cameras, operating at 140 frames per second (fps), provide low-latency sensing with minimal motion blur to reliably detect and track incoming objects. A lightweight Kevlar sail serves as the interception surface, absorbing or deflecting impacts while maintaining a compact and portable platform [

17]. This sail should be worn on the shoulder, helmet, or backpack to increase effective range; thus, detection and interception must be integrated reliably.

System Structure

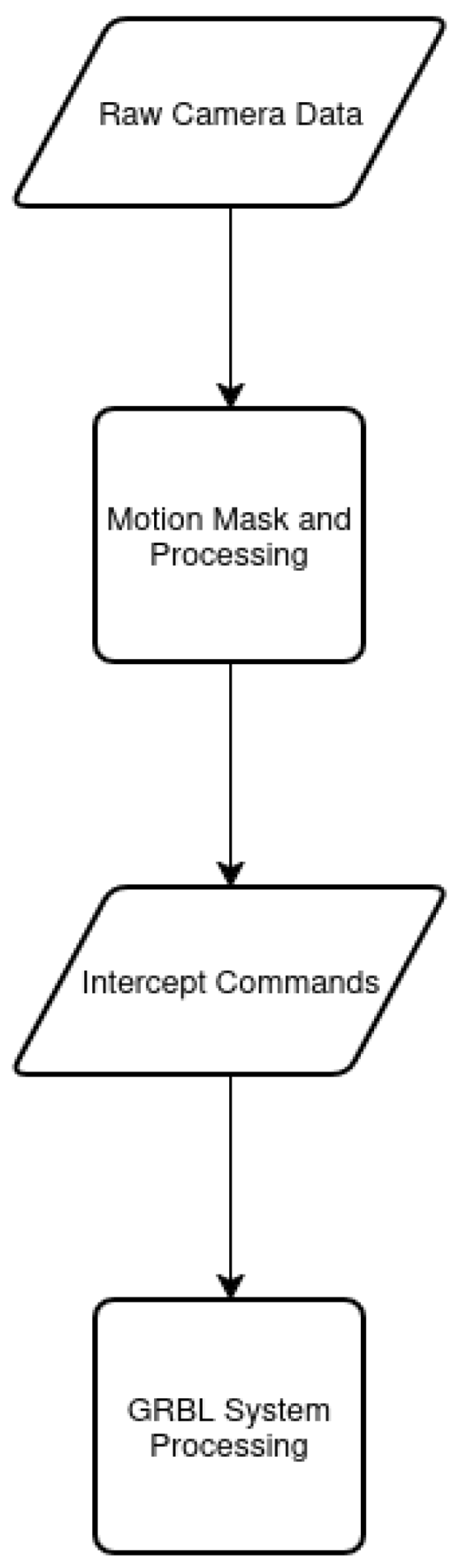

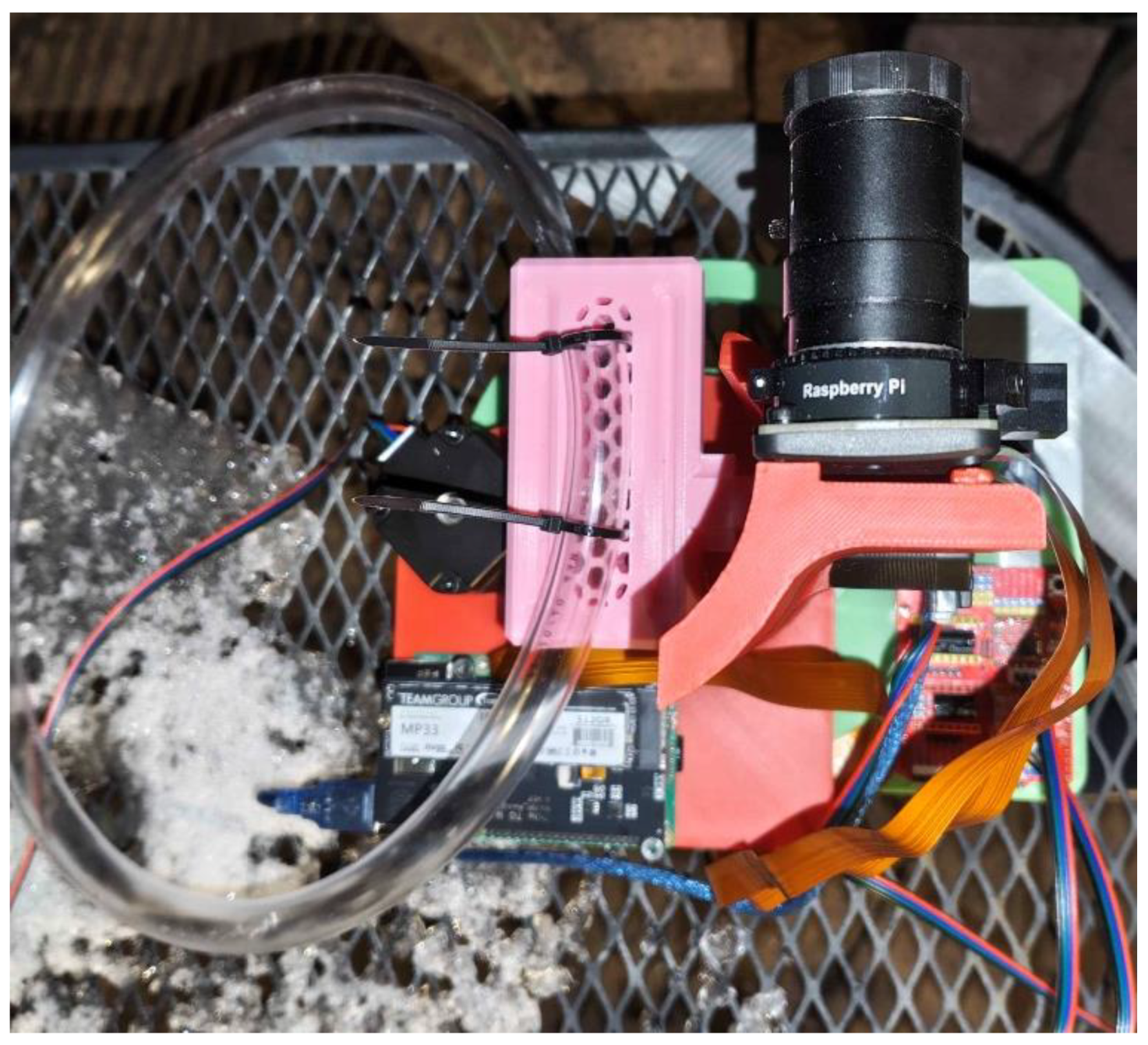

As presented in

Figure 1, the ANCILE system was built around two cooperating subsystems: a GRBL-based Arduino (Arduino, Turin, Italy) motion controller that drives the mechanical positioning hardware, and a Raspberry Pi 5 (Raspbery Pi, Cambridge, UK) vision subsystem that processes camera data, estimates trajectories, and generates the corresponding GRBL instructions [

45]. Combined, these components form an integrated, autonomous protective system to identify incoming hazards and dynamically react in real time.

Processing Software

Initially employed in computer numerical control (CNC) machining, GRBL was applied in ANCILE as the firmware that drives the Arduino-based motion system. As a CNC framework, the system interprets incoming G-code commands and converts them into precise step and direction signals for stepper motors, allowing the interception mechanism to move quickly and predictably. Because GRBL handles timing, acceleration, and coordinated motion on the microcontroller, the Raspberry Pi can focus on sensing and decision-making while the Arduino executes the low-level motor control required for fast, accurate positioning.

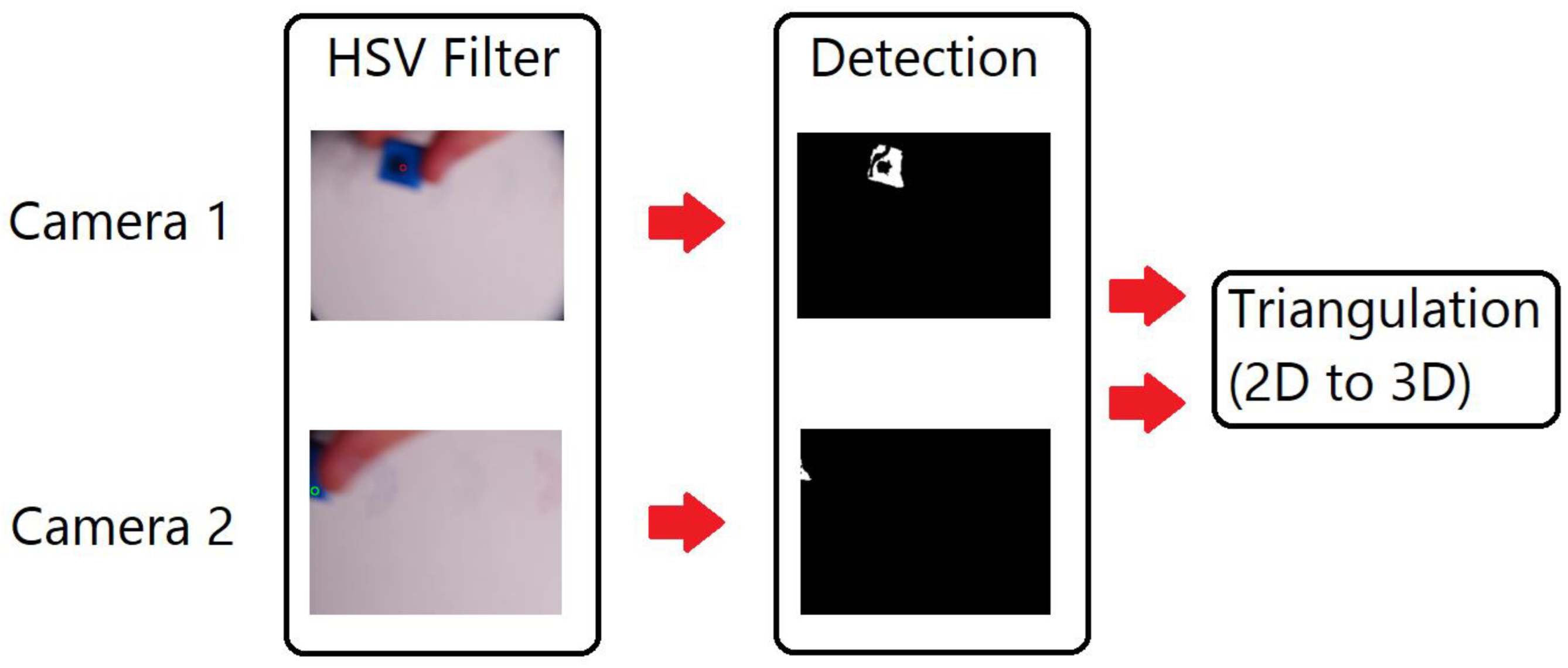

Image Processing

The ANCILE system employs two IMX296 cameras (Sony, Tokyo, Japan) connected to a Raspberry Pi 5 to sense incoming projectiles and estimate their paths in real time. The cameras provide YUV420 frames, which are processed using a motion- and color-based detector at 140 fps. A commercial PC laptop was used for processing. In

Figure 2, motion detection identifies fast-moving objects between frames, and an integrated hue, saturation, value filter isolates the cyan-colored projectile tip. Combining these techniques allows the system to ignore background movement, lighting changes, and noise while reliably locking onto the projectile [

43,

44].

Figure 2 presents the components employed in the ANCILE system.

When both cameras detect the projectile in the same frame interval, the software performs stereo triangulation to convert the two-pixel locations into a 3D position [

43]. In each dimension, the Raspberry Pi stores several of these 3D points (

) across consecutive frames and fits a simple linear trajectory model to estimate the projectile speed and travel direction [

43,

44]. In Eq. (1), this process provides the system with a short-term prediction of how the projectile moves through space (

):

Using this prediction, the Raspberry Pi determines where the projectile intersects a fixed interception plane in front of the CNC mechanism. As this technique is well-documented by prior work, more information is available in the supplemental data [

43,

44]. If the predicted interception location is reachable within the available time, the Pi sends G-code commands to GRBL so the CNC can move into position and prepare to fire. The GRBL module executes the motion with correct step timing and coordinated axis control, and the launcher is activated using standard coolant commands.

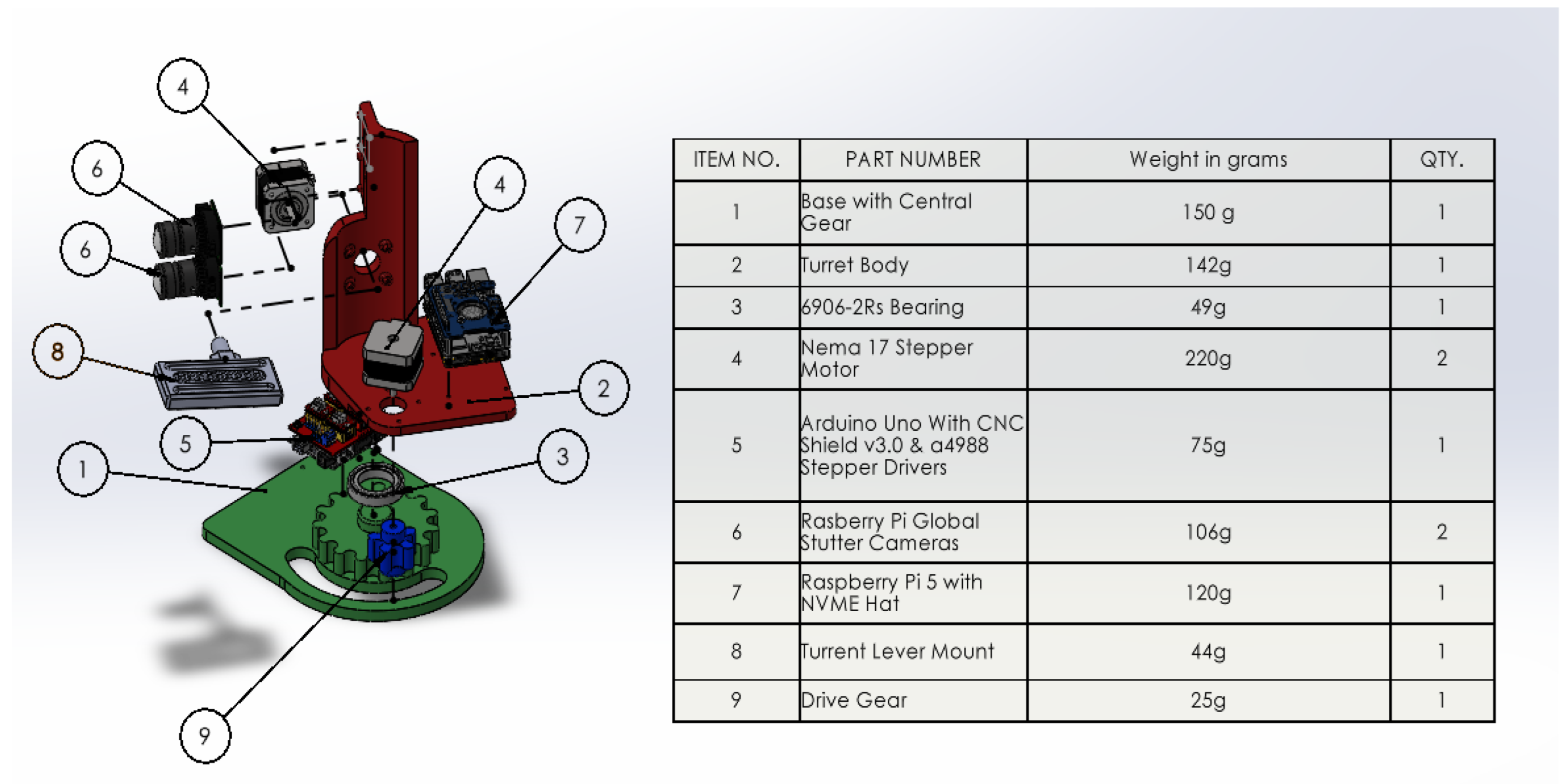

Launcher Design

The 1.26 kg launcher is simple and robust to retain user comfort. Standard school backpacks and PPE weigh far more than a pair of shoulder-mounted launchers [

18]. The launcher comprises an acrylic hose mounted to a tilting frame that serves as the

y-axis of the CNC assembly.

Figure 3 presents a breakdown by component weight. The turret was designed to tilt at 50° for vertical motion and 120° for horizontal motion. The turret base is 200 mm high, 145 mm long, and 139 mm wide.

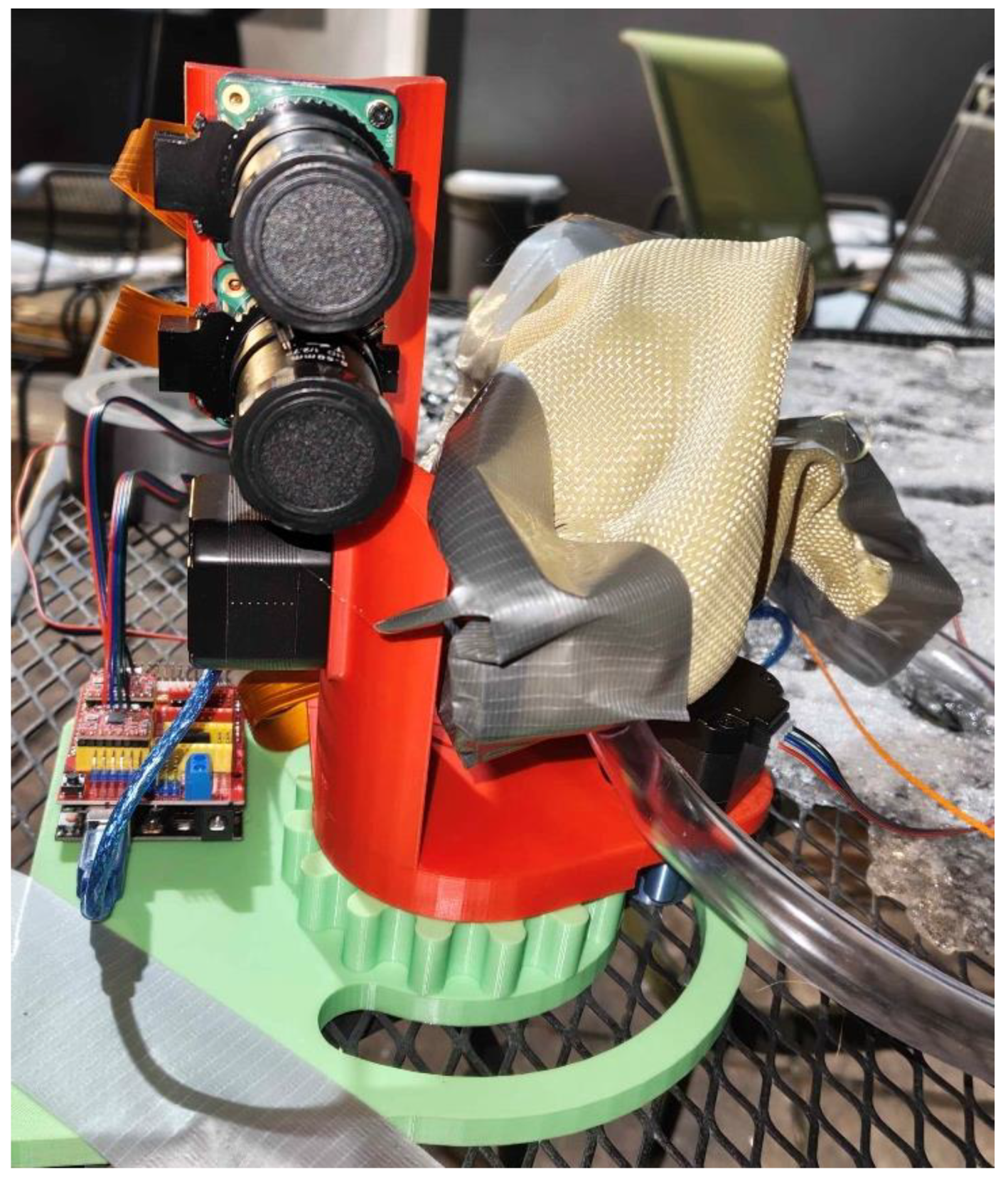

Figure 4 depicts the launcher view from the front.

Figure 5 depicts the launcher view from the top.

Figure 6 depicts the launcher view from the front.

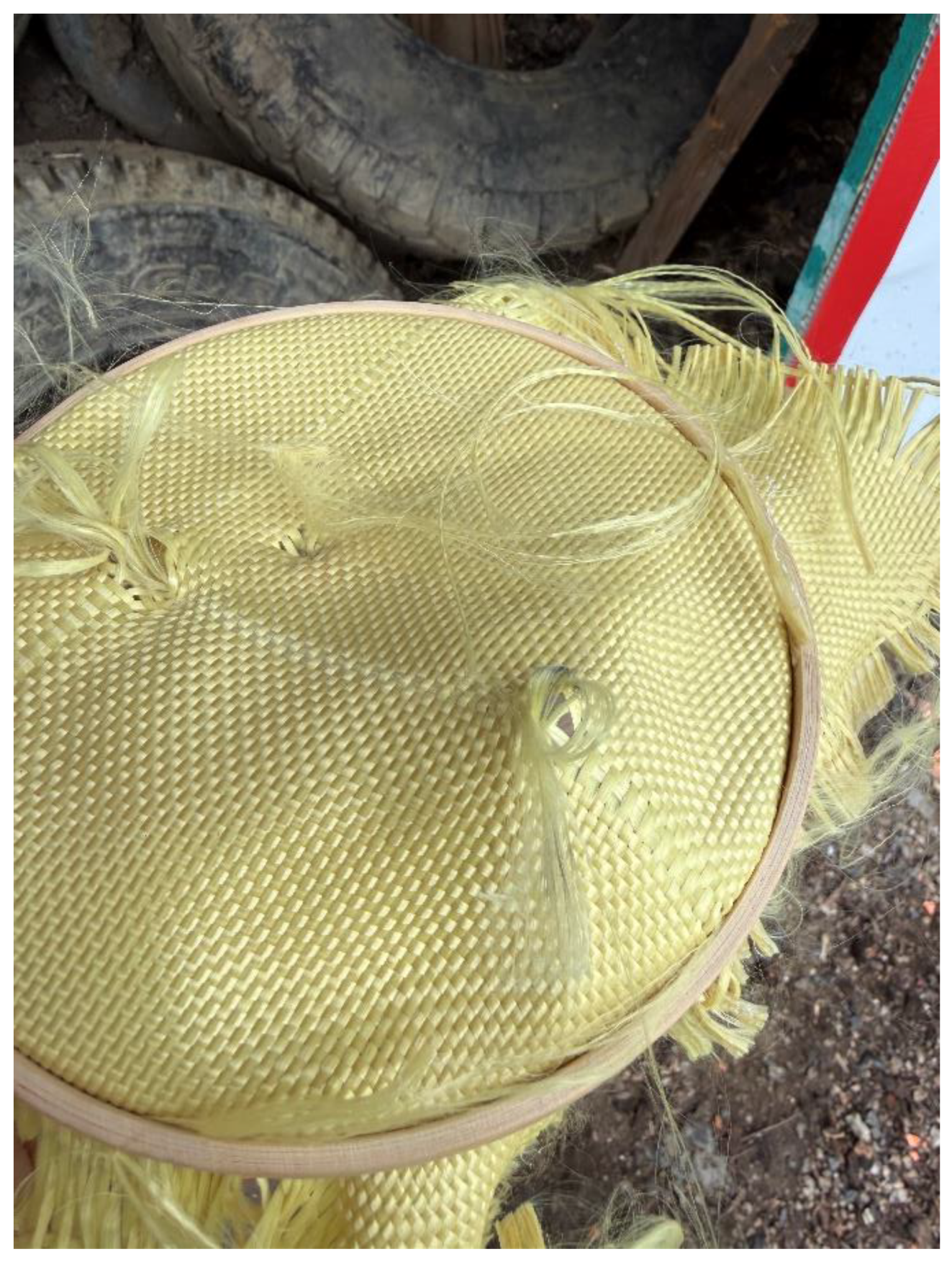

The hose is connected to an air compressor via a solenoid valve, which is wired to the coolant output on the Arduino CNC shield. When the coolant is turned on, compressed air is released through the hose. In

Figure 7, a lightweight tethered Kevlar sail, about 100 x 100 mm and weighing 40 g, is placed above the hose, and the tilt angle determines the direction of the air burst. When the system fires, the air jet strikes the sail at 0.689 MPa (~100 PSI), swinging it into the projectile path and intercepting it.

Interception Testing

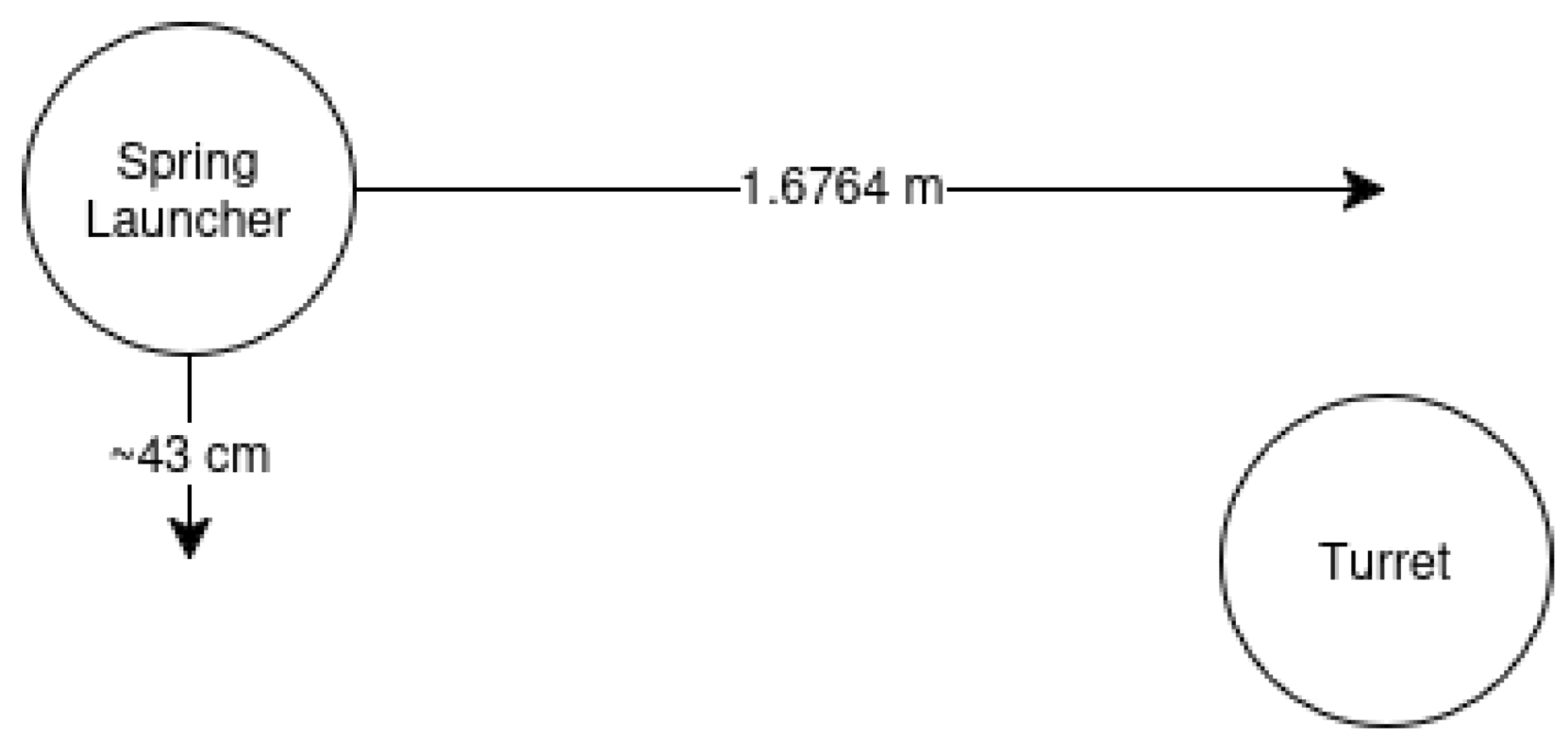

Figure 8 illustrates the testing of a modular spring-based launcher system that enables precise control of the projectile velocity. The test projectile was loaded in, and the spring was set to the desired kinetic energy. The test projectile was then launched in front of the device.

By adjusting the internal spacers and outer extensions, varying the potential energy of the spring can produce a range of speeds. The spring-based launcher discharged a (12.7-mm-diameter, 72-mm-long) foam dart with an M4 x 12 mm bolt inserted, weighing 0.0114 kg. This approach enables an evaluation of the ANCILE system performance across various projectile velocities, travel distances, and timing conditions.

In

Figure 9, the turret was positioned perpendicularly to the launcher. The vertical and horizontal distances between the two devices were 43 and 167.6 cm, respectively. A velocity of 20 m/s was initially employed, decreasing by 2.5 m/s if the tests failed. The lowest velocity was 5 m/s. Three trials were conducted at each velocity, and the results were averaged.

Sail Testing

In addition to launcher testing, the Kevlar sail was stress tested against conventional ballistic projectiles. The sail was deployed on a string and applied as a ballistic pendulum. The experiment tested the velocity imparted to the pendulum and the potential failure conditions of the Kevlar sheet. The mass of each bullet was also compared before and after interception to estimate the energy imparted to the sail. The cartridges include .22 Long Rifle (LR), .38 Special, .45 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP), and .357 Magnum. The ammunition brands were Federal AutoMatch .22 LR, hand-loaded .38 Special, Federal Range and Target .45 ACP, and hand-loaded .357 Magnum. Two cartidges of each brand were used. All bullets were discharged from a 5-inch handgun at 3.4 m.

A ballistic pendulum of mass 2.89 kg was employed to measure the velocity of each bullet to compare the use of the Kevlar sail. In Eq. (2), the kinetic energy

KE (Joules) results from the relationship between velocity

and mass

[

46]:

In the pendulum, the potential energy at its maximum swing

is given in Eq. (3), which is a product of the mass

m, height

h, and gravity

g [

46]:

In addition, Eq. (2) can be substituted into Eq. (3) for Eq. (4) at the maximum swing, representing the energy impulse of the impact:

Although some energy is lost, the ballistic pendulum equation in Eq. (5) was streamlined for calculation [

46]:

The mass of the bullet was measured after recovery to determine whether the amount of mass loss was substantial. If the bullet lost more than 5% of its mass, it shattered and fragmented instead of transferring its energy. Observed with a camera, the calculated pendulum impulse could be assumed to be at a minimum due to the physical setup constraints (Milutinovic et al. 2019).

Statistical Testing and Hypotheses

Statistical testing was independently tracked for interception and sail testing. Due to camera and system latency limitations, it was hypothesized that this system would not operate reliably above a certain velocity. A paired

t-test was conducted to determine whether the differences between velocities with successful and unsuccessful hits were significant [

11,

38]. If the values differed significantly, the velocity is considered a hard limit. The ballistic testing employed a statistical correlation, calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the bullet energy and imparted energy. A higher coefficient value indicates a reliable Kevlar sail, resulting in a coefficient closer to 1. It is hypothesized that the sail exhibits a high correlation between imparted energy and the projectile velocity during ballistic testing [

17], and if not, the protectiveness of the sail is unreliable.

Results

Overview

Interception and ballistic testing results were conducted. For the interception tests, the average results from each of the three trials was compared. For the ballistic tests, the amount of kinetic energy imparted was calculated.

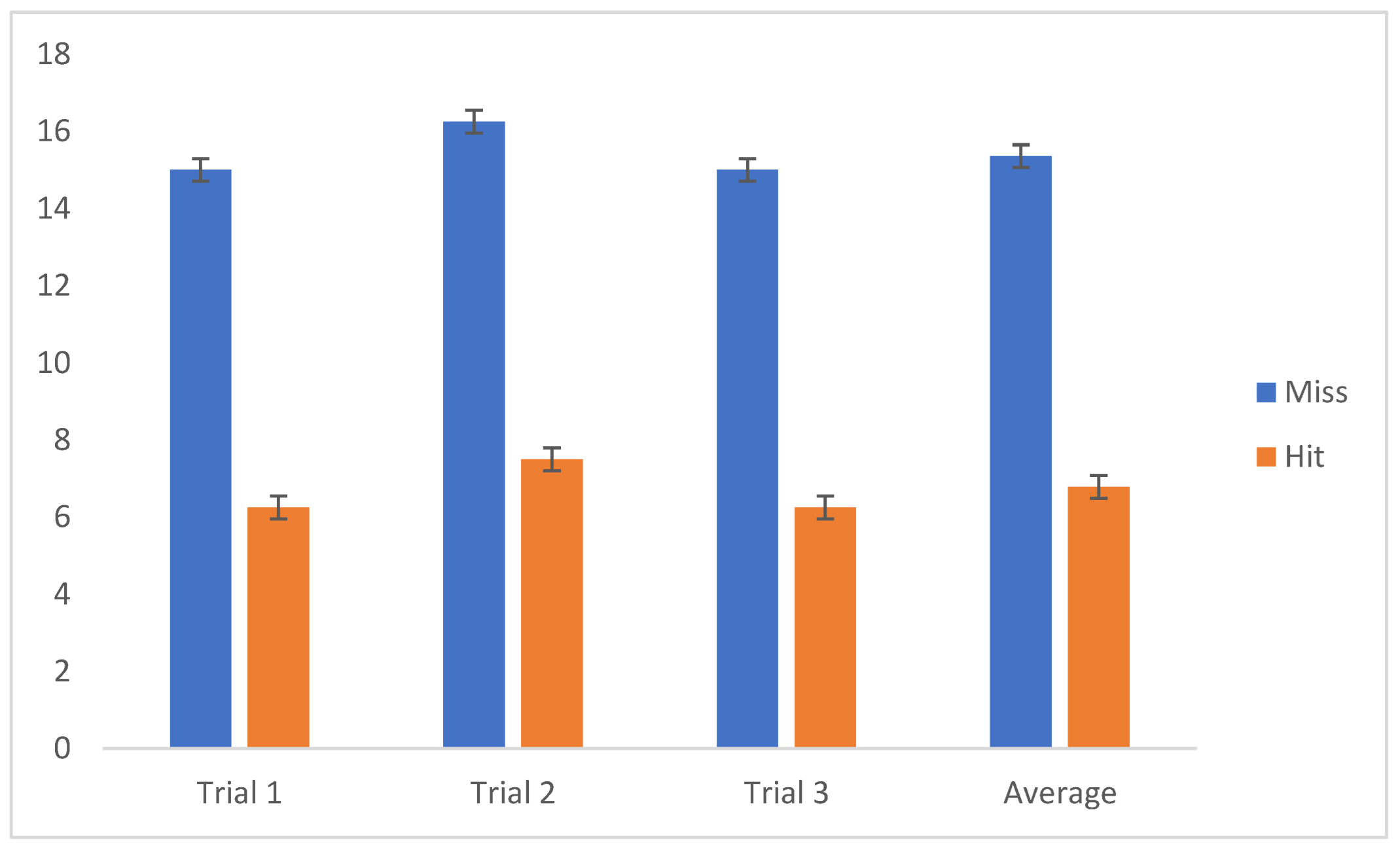

Interception Testing Results

The mean velocity of the trials was 12.5 ± 5.40 m/s. Across all cases in

Figure 10, the overall hit rate was 28.6 % ± 8.3%. The highest projectile velocity that could be reliably intercepted was 7.5 m/s. The average velocity of the successfully intercepted projectiles was 6.8 ± 0.5 m/s. The average velocity of the missed interceptions was 15.4 ± 0.6 m/s. The difference between the hit and miss velocities was significant (

t = 21.2,

p < 0.001).

Ballistic Testing Results

Table 1 lists the ballistic results. The bullet fragment losses were all less than 5%. The highest impulse energy was imparted by the .357 Magnum, and the minimum energy was 26.2 J. The least energy imparted was by the .22 LR, at a minimum of 0.49 J.

Each round was placed beside recovered bullets in

Figure 11 to compare the visual effects of the impact with the Kevlar sheet.

Figure 12 illustrates the repeated ballistic impact damage to the sail. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated as

r = 0.971, confirming the experimental hypothesis regarding the relationship between energy imparted by ballistic impact.

Discussion

Interpretation

The ANCILE system demonstrated a proof of concept for a low-cost, wearable active-projectile interception system to augment conventional PPE. The overall interception rate was 28.6% ± 8.3% across the tested velocity spectrum; however, the reliability exhibited a pronounced transition at a distinct threshold velocity. In contrast to

Dune’s fictional defensive fields, which nominally arrest objects at approximately 9 cm/s, the ANCILE system consistently intercepted projectiles at or below 7.5 m/s, a regime representative of many unintentional industrial projectiles (e.g., tool fragments or ricochets) [

12,

18]. Given the strong correlation between the impulse and projectile kinetic energy, the demonstrated ability of the Kevlar sail to withstand impacts from handgun rounds up to .357 Magnum suggests its substantial robustness to conventional ballistic threats [

17]. Currently, contemporary worn PPE is predominantly passive, whereas the ANCILE system establishes that an actively controlled, body-worn interceptor is technically feasible using low-cost, commercially available, or open-source components. The resulting 1.26-kg prototype exhibited multiple technical limitations requiring further engineering refinement.

Limitations

The ANCILE system is a limited prototype with many opportunities for improvement. The first is the sensor selection, based on relatively slow, low-cost cameras. Space debris and conventional bullets require far more precise sensors for a rapid, timely response [

32,

39]. Trajectory estimation and deployment determination must be performed more quickly than the 140 fps cameras allow. Improving the algorithms (e.g., those with Kalman filtering or fitted functions) could improve resilience [

43,

44]. The deployment system has flaws in the turret and propulsion mechanism. The turret mechanisms constrain the ability to swivel, pan, and pivot, limiting the field of view of the sensors. The pneumatic system may add extra weight, which was not accounted for in the test model. Various projectile types require their own interception methods, some of which may be more difficult to intercept than a foam dart [

39,

41]. The sail geometry and materials could be optimized to achieve a greater coverage area, especially in vulnerable areas [

3,

13]. The lack of a retraction and reset system also limits its repeated use in the field. Likewise, the weight, size, and shape could be optimized. A broader range of projectiles, including conventional and unconventional projectiles, could be explored to improve sampling efficiency [

5,

15]. Despite these limitations, the project possesses clear potential.

Future Work

The ANCILE system could be improved by reducing the system latency, optimizing the interception angle, broadening the sensor modalities and field of view, improving the detection algorithm, redesigning the Kevlar sail geometry, and accelerating the sail deployment [

6,

33]. Low-cost, open-source components could be replaced with higher-grade components, as existing high-performance space robotics and aerospace systems can react in milliseconds [

32,

42]. Beyond hardware and software improvements, determining the most ergonomic and comfortable way to wear and carry the device would involve a task-based biomechanical analysis. The system could be optimized for specific projectile types, from those in industrial mishaps and conventional ballistics to entertainment [

4,

7,

38]. The low device weight indicates it could also be mounted on a spacecraft to divert incoming debris. In addition to its size and weight, the device must also be tested to ensure it remains reliable while the user is in motion. In summary, the ANCILE system could advance the popular depiction of force fields closer to becoming reality.

Conclusions

Despite the existence of active protection in military vehicles for decades, wearable PPE relies on passive properties [

2,

17,

18]. The ANCILE system adapts the concept of an active point-defense system to a wearable device, evaluating interception rate and resilience to ballistic impacts. The device employs two cameras to control a pneumatic turret that launches a Kevlar sail. The interception rate was 28.6 % ± 8.3% for velocities from 5.0 to 20.0 m/s. Velocities at or below 7.5 m/s were reliably hit, with reliability dropping above that velocity. As in prior literature, the Kevlar sail withstood pistol fire from .22 LR to .357 Magnum [

17]. Despite its relatively low hit rate across all velocities, many dropped objects and unintentional projectiles were at or below 7.5 m/s. With further improvements to its hardware and software, the ANCILE system could be deployed to prevent impacts and injuries in industry, entertainment, emergency response, firefighting, aerospace, and defense domains [

8,

10,

18,

21,

32].

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Ohio State University.

References

- K. Motyl, M. Magier, J. Borkowski and B. Zygmunt, "Theoretical and experimental research of anti-tank kinetic penetrator ballistics," Bulletin of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Technical Sciences, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 1-6, 2017.

- H. K. Chia, A simulation of a combined active and electronic warfare system for the defense of a naval ship against multiple low-altitude missiles threat., Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, 2019.

- M. Wickert, "Electric armor against shaped charges: Analysis of jet distortion with respect to jet dynamics and current flow," IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 426-429, 2006.

- Z. Rosenberg, Z. Surujon, Y. Yeshurun, Y. Ashuach and E. Dekel, "Ricochet of 0.3 ″AP projectile from inclined polymeric plates," International journal of impact engineering, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 221-233, 2005.

- J. Norris, A. Hameed, J. Economou and S. Parker, "A review of dual-spin projectile stability," Defence Technology, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1-9, 2020.

- O. E. Thompson, "Coriolis deflection of a ballistic projectile," American Journal of Physics, vol. 40, no. 10, pp. 1477-1483, 1972.

- L. Hill, T. Woodward, H. Arisumi and R. L. Hatton, "Wrapping a target with a tethered projectile," Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, vol. 2015, no. 1, pp. 1442-1447, 2015.

- G. R. Cooper and M. Costello, "Flight dynamic response of spinning projectiles to lateral impulsive loads," J. Dyn. Sys., Meas., Control, vol. 126, no. 3, pp. 605-613, 2004.

- N. A. Corbin, J. A. Hanna, W. R. Royston, H. Singh and R. B. Warner, "Impact-induced acceleration by obstacles," New Journal of Physics, vol. 20, no. 5, p. 053031, 2018.

- H. F. L. P. da Rocha, Trajectory and aerodynamic analyses of air launched fire-extinguishing projectiles, Covilha, Portugal: Universidade da Beira Interior (Portugal), 2020.

- H. Faraji, S. Veile, S. Hemleben, P. Zaytsev, J. Wright, H. Luchsinger and R. L. Hatton, "Impulse redirection of a tethered projectile," Proceedings from the Conference on Dynamic Systems and Control, vol. 57267, no. 1, p. V003T43A002, 2015.

- F. Herbert, Dune, Boston, MA, USA: Chilton Books, 1965.

- M. Mayseless, "Effectiveness of explosive reactive armor," Journal of Applied Mechanics, vol. 78, no. 5, p. 051006, 2011.

- S. A. Ahmed, M. Mohsin and S. M. Z. Ali, "Survey and technological analysis of laser and its defense applications," Defence Technology, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 583-592, 2021.

- N. T. Anh, N. H. Anh and N. T. Dat, "Development of a framework for ballistic simulation," Int. J. Simul. Model, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 623-632, 2018.

- Ballistics 101, "308 Winchester Ballistics," Ballistics 101, 1 January 2009. [Online]. Available: http://www.ballistics101.com/308_winchester.php. [Accessed 3 March 2022].

- S. Sockalingam, S. C. Chowdhury, J. W. Gillespie Jr and M. Keefe, "Recent advances in modeling and experiments of Kevlar ballistic fibrils, fibers, yarns and flexible woven textile fabrics–a review," Textile Research Journal, vol. 87, no. 8, pp. 984-1010, 2017.

- J. S. Peatie, H. Haroglu and T. Umar, "Barriers to achieving satisfactory dropped objects safety performance in the UK construction sector," Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 17, p. e37413, 2024.

- A. Shtarbanov, AirTap: a multimodal interactive interface platform with free-space cutaneous haptic feedback via toroidal air-vortices, Cambridge, MA, USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2018.

- M. Shusser and M. Gharib, "Energy and velocity of a forming vortex ring," Physics of Fluids, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 618-621, 2000.

- R. Sodhi, I. Poupyrev, M. Glisson and A. Israr, "AIREAL: interactive tactile experiences in free air," ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG), vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 1-10., 2013.

- D. G. Akhmetov, M. S. Kotelnikova, V. V. Nikulin, A. V. Plastinin, E. A. Chashnikov, V. F. Kop’ev and M. Y. Zaitsev, "Generation of large-scale high-velocity vortex rings by initiating an explosive," Combustion, Explosion, and Shock Waves, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 390-394, 2019.

- A. G. R. Ramírez, F. J. G. Luna, O. O. V. Villegas and M. Nandayapa, "Applications of Haptic Systems in Virtual Environments: A Brief," Advanced Topics on Computer Vision, Control and Robotics in Mechatronics, vol. 2018, no. 1, p. 349, 2018.

- Y. V. Anishchanka and E. Y. Loktionov, "Comparison of laser breakdown and laser ablation ignition thresholds of combustible gas mixtures," Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 1556, no. 1, p. 012012, 2020.

- S. Ishizuka, T. Yamashita and D. Shimokuri, "Further investigation on the enhancement of flame speed in vortex ring combustion," Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 745-753, 2013.

- C. Boonsri, S. Sumriddetchkajorn and P. Buranasiri, "Laser-based mosquito repelling module," Proceedings of the Photonics Global Conference, vol. 2012, no. 1, pp. 1-4, 2012.

- R. Ildar, "RaspberryPI for mosquito neutralization by power laser," arXiv preprint, vol. 2021, no. 1, p. 2105.14190, 2021.

- C. L. Gargan-Shingles, The influence of azimuthal velocity and a parallel wall on vortex ring evolution, Melbourne, Australia: Monash University, 2017.

- H. Kopecek, H. Maier, G. Reider, F. Winter and E. Wintner, "Laser ignition of methane–air mixtures at high pressures," Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 499-503, 2003.

- J. X. Ma, D. R. Alexander and D. E. Poulain, "Laser spark ignition and combustion characteristics of methane-air mixtures," Combustion and Flame, vol. 112, no. 4, pp. 492-506, 1998.

- M. Weinrotter, H. Kopecek, M. Tesch, E. Wintner, M. Lackner and F. Winter, "Laser ignition of ultra-lean methane/hydrogen/air mixtures at high temperature and pressure," Experimental thermal and fluid science, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 569-577, 2005.

- M. Bigdeli, R. Srivastava and M. Scaraggi, "Mechanics of space debris removal: A review," Aerospace, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 277, 2025.

- Z. Yang, L. Wang and J. Chen, "Movement Characteristics of a Dual-Spin Guided Projectile Subjected to a Lateral Impulse," Aerospace, vol. 8, no. 10, p. 309, 2021.

- S. V. Fedorov, V. A. Veldanov, M. Y. Sotskiy and N. A. Fedorova, "Jet thrust penetrators for sounding the surface layer of space bodies," Acta Astronautica, vol. 180, no. 1, pp. 189-195, 2021.

- T. Hatakeyama and H. Mochiyama, "Shooting manipulation," Abstracts of the international conference on advanced mechatronics: toward evolutionary fusion of IT and mechatronics, vol. 2010, no. 5, pp. 456-461, 2010.

- K. Xue, C. Ren, X. Ji and H. Qian, "Design, modeling and implementation of a projectile-based mechanism for USVs charging tasks," IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 288-295, 2022.

- J. Taddeucci, M. A. Alatorre-Ibargüengoitia, O. Cruz-Vázquez, E. Del Bello, P. Scarlato and T. Ricci, "In-flight dynamics of volcanic ballistic projectiles," Reviews of Geophysics, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 675-718, 2017.

- R. Li, D. Li and J. Fan, "Dynamic Response Analysis for a Terminal Guided Projectile with a Trajectory Correction Fuze," IEEE Access, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 94994-95007, 2019.

- P. V. Hahn, R. A. Frederick and N. Slegers, "Predictive guidance of a projectile for hit-to-kill interception," IEEE Transactions on control systems technology, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 745-755, 2009.

- A. F. Scannapieco, A. Renga, G. Fasano and A. Moccia, "Ultralight radar sensor for autonomous operations by micro-UAS," Proceedings from the international conference on unmanned aircraft systems (ICUAS), vol. 2016, no. 1, pp. 727-735, 2016.

- N. Slegers, "Predictive control of a munition using low-speed linear theory," Journal of guidance, control, and dynamics, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 768-775, 2008.

- V. Mérelle, A. Gaugue, G. Louis and M. Ménard, "UWB pulse radar for micro-motion detection," International Conference on Ultrawideband and Ultrashort Impulse Signals (UWBUSIS), vol. 2016, no. 8, pp. 152-155, 2016.

- Z. Qin, J. Wang and Y. Lu, "Triangulation learning network: from monocular to stereo 3d object detection," Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, vol. 2019, no. 1, pp. 7615-7623, 2019.

- A. Islam, M. Asikuzzaman, M. O. Khyam, M. Noor-A-Rahim and M. R. Pickering, "Stereo vision-based 3D positioning and tracking," IEEE Access, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 138771-138787, 2020.

- grbl, "grbl (Version v0.9j and earlier)," 1 January 2009. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/grbl/grbl. [Accessed 5 October 2025].

- J. M. Milutinovic, N. P. Hristov, D. D. Jerković, S. Z. Marković and A. B. Živković, "The application of the ballistic pendulum for the bullets velocity measurements," IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 659, no. 1, p. 012016, 2019.

Figure 1.

Detection and interception system logic.

Figure 1.

Detection and interception system logic.

Figure 2.

Image processing flow from two-dimensional cameras to the stereo triangulation of three-dimensional coordinates. HSV: hue, saturation, value.

Figure 2.

Image processing flow from two-dimensional cameras to the stereo triangulation of three-dimensional coordinates. HSV: hue, saturation, value.

Figure 3.

Turret diagram and component list, including the base, body, bearing, stepper motor, Arduino Uno, cameras, Raspberry Pi, lever mount, and drive gear.

Figure 3.

Turret diagram and component list, including the base, body, bearing, stepper motor, Arduino Uno, cameras, Raspberry Pi, lever mount, and drive gear.

Figure 4.

Assembled ANCILE launcher viewed from the front.

Figure 4.

Assembled ANCILE launcher viewed from the front.

Figure 5.

Assembled ANCILE launcher viewed from the top.

Figure 5.

Assembled ANCILE launcher viewed from the top.

Figure 6.

Assembled ANCILE launcher viewed from the back.

Figure 6.

Assembled ANCILE launcher viewed from the back.

Figure 7.

Kevlar sail for ballistic interception.

Figure 7.

Kevlar sail for ballistic interception.

Figure 8.

Modular spring launcher for interception tests.

Figure 8.

Modular spring launcher for interception tests.

Figure 9.

Top-down view of the turret positioned relative to the spring launcher.

Figure 9.

Top-down view of the turret positioned relative to the spring launcher.

Figure 10.

Average velocities of successful interception hits and misses.

Figure 10.

Average velocities of successful interception hits and misses.

Figure 11.

Comparison of standard rounds (top) with recovered bullets (bottom). Left to right: .22 Long Rifle (LR), .38 Special, .45 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP), and .357 Magnum.

Figure 11.

Comparison of standard rounds (top) with recovered bullets (bottom). Left to right: .22 Long Rifle (LR), .38 Special, .45 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP), and .357 Magnum.

Figure 12.

Visual damage to the Kevlar sail after ballistic testing.

Figure 12.

Visual damage to the Kevlar sail after ballistic testing.

Table 1.

Ballistic test results on the Kevlar sail.

Table 1.

Ballistic test results on the Kevlar sail.

| Caliber |

Energy (J) |

Mass (g) |

Mdelta (%) |

Eimpulse (J) |

| .22 LR |

108.00 |

2.49 |

0.04 |

0.49 |

| .38 Special |

254.00 |

10.19 |

0.00 |

6.80 |

| .45 ACP |

352.00 |

14.90 |

0.01 |

15.40 |

| .357 Magnum |

780.00 |

10.14 |

0.01 |

26.20 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).