Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Analysis of Damage Causes and On-Shore Impact Scenarios

2.1. Background Statistics

2.2. Use Cases with Stacking Operations On-Shore

3. Results

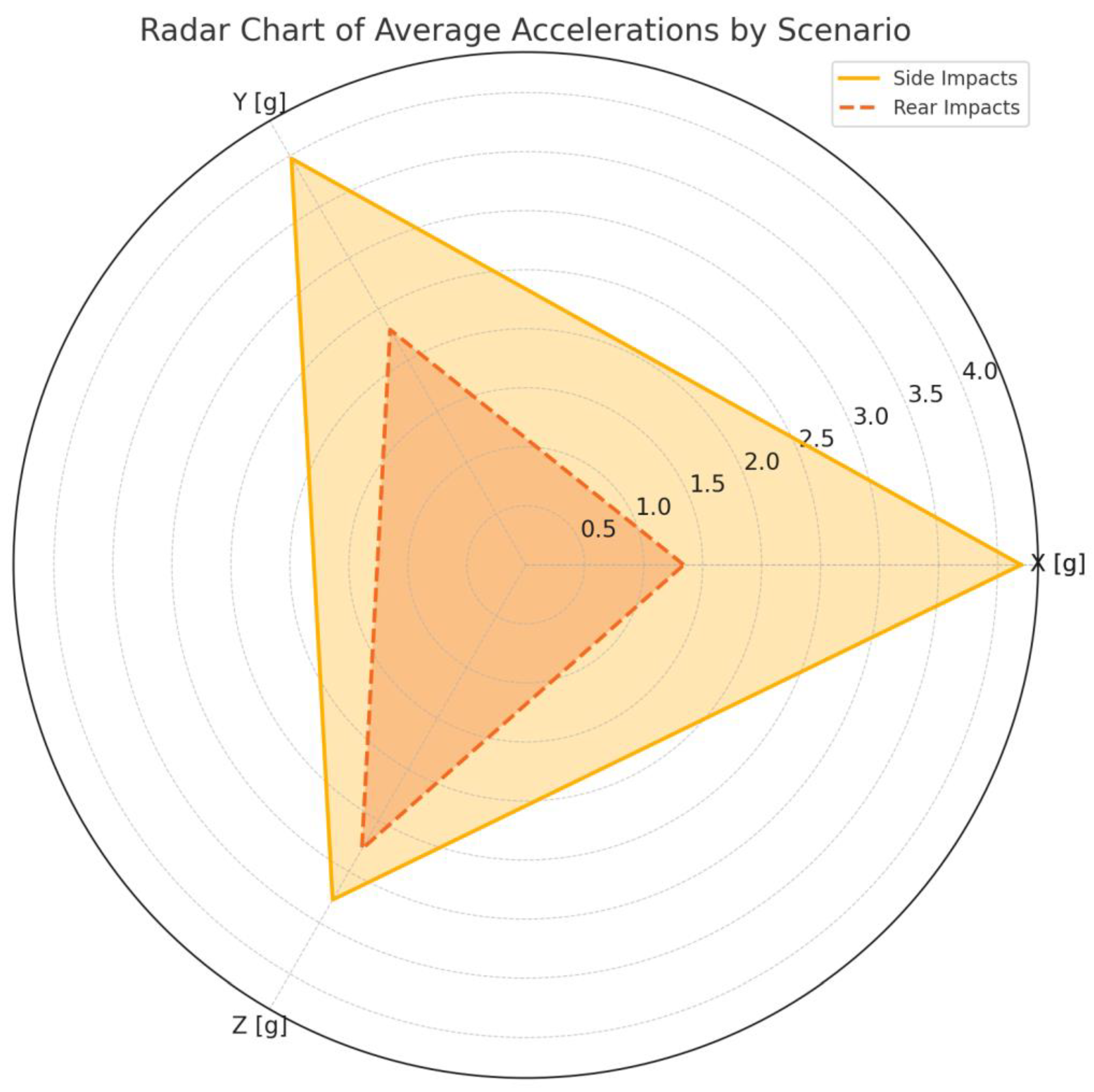

- (1) side impacts during stacking in container yards.

- (2) rear impacts during loading onto truck trailers.

3.1. Side Impact Measurements

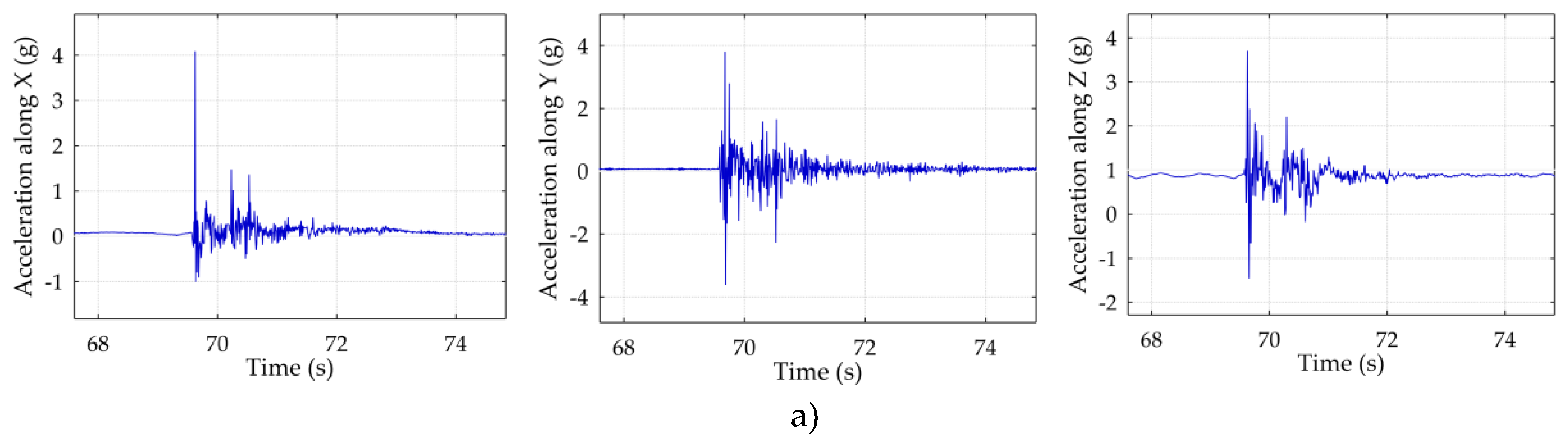

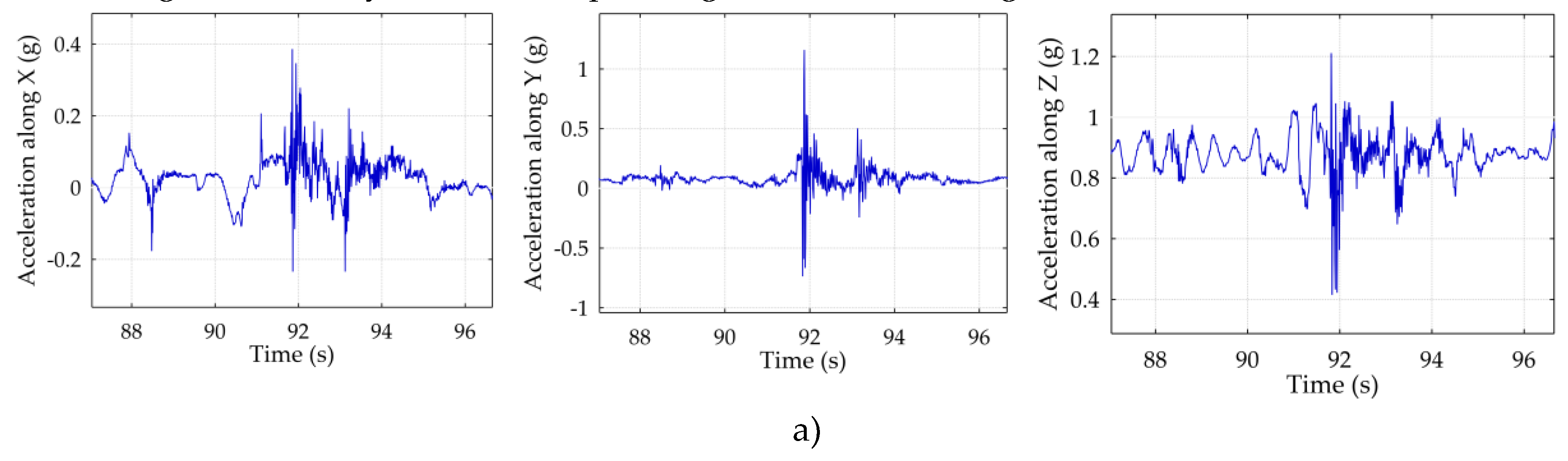

- 10:21:34 (see figure 6a)) – Peak acceleration: X = 4.1 g, Y = 3.8 g, Z = 3.9 g.

- 10:23:00 (see Figure 6b)) – Peak acceleration: X = 7.2 g, Y = 3.2 g, Z = 4.2 g.

- 10:24:22 (see Figure 6c)) – Peak acceleration: X = 2.3 g, Y = 5.1 g, Z = 2.7 g.

- 10:26:26 (see Figure 6d)) – Peak acceleration: X = 3.2 g, Y = 3.8 g, Z = 2.3 g.

3.2. Rear Impact Measurements

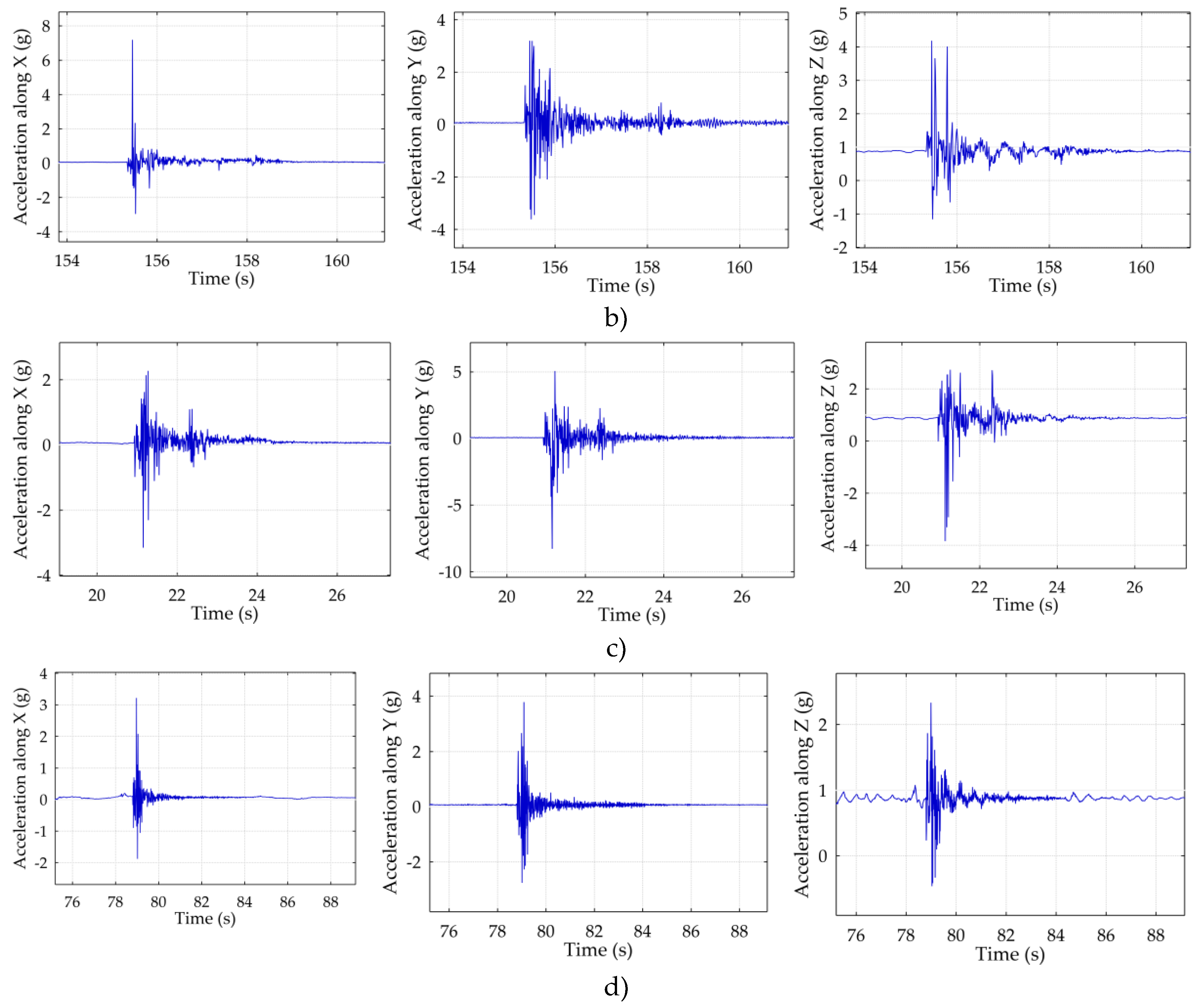

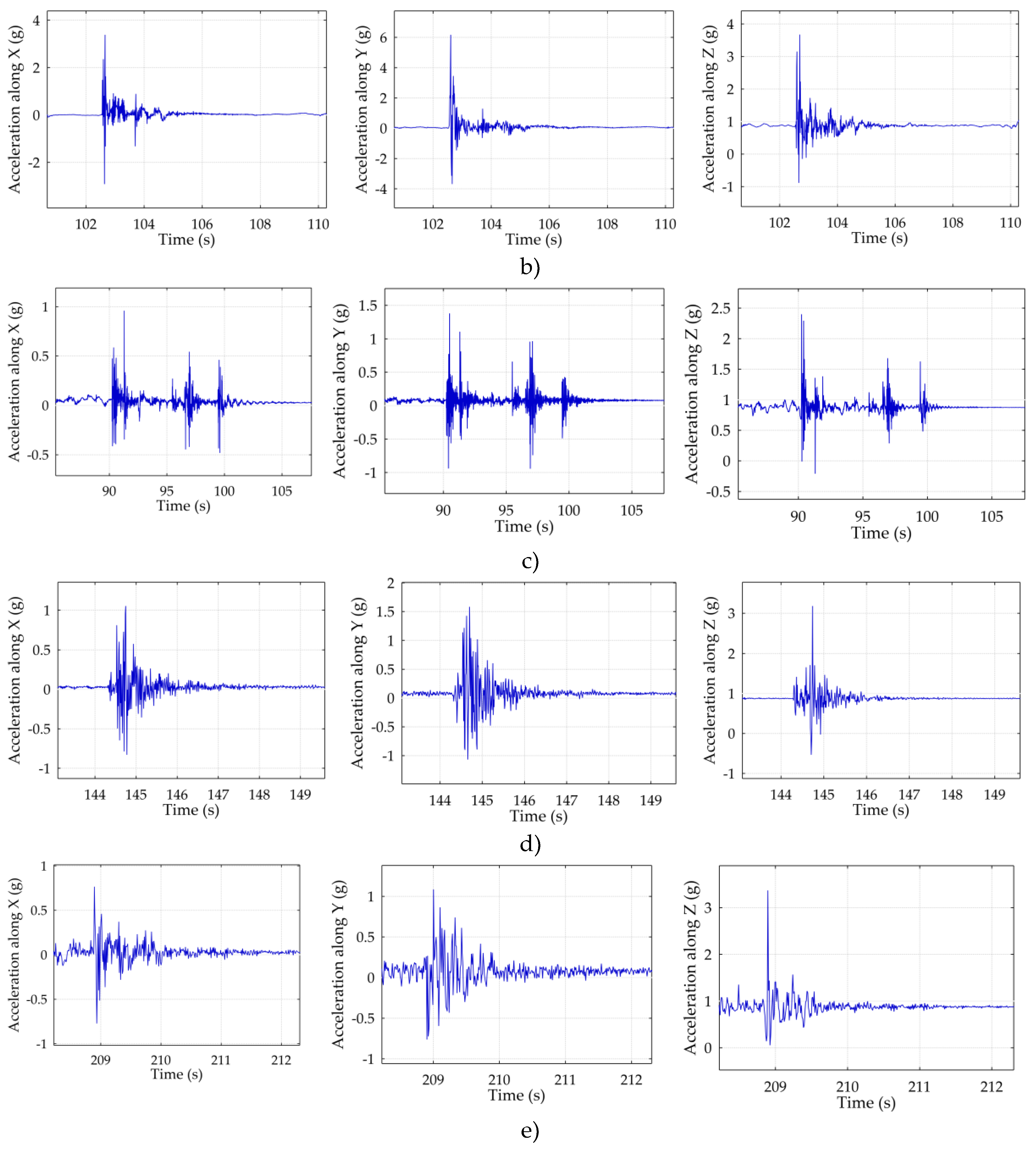

- 10:39:56 (mild impact) – X = 0.4 g, Y = 1.2 g, Z = 1.2 g.

- 10:40:06 (aggressive impact) – X = 3.4 g, Y = 6.2 g, Z = 3.7 g.

- 10:43:17 (mild impact) – X = 1.0 g, Y = 1.4 g, Z = 2.4 g.

- 10:44:06 (aggressive impact) – X = 1.1 g, Y = 1.6 g, Z = 3.2 g.

- 10:45:10 (mild impact) – X = 0.8 g, Y = 1.1 g, Z = 3.4 g.

3.3. Interpretation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TEU | Twenty-foot equivalent units |

| AGVJ | Automated guided vehicle |

| TOS | Terminal operating systems |

| ERP | Enterprise resource planning |

| ASC | Automated stacking cranes |

References

- Nguyen, P.N.; Kim, H.; Son, Y.M. Challenges and Opportunities for Southeast Asia’s Container Ports throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic. Research in Transportation Business and Management 2024, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhu, S.; Bell, M.G.H.; Lee, L.H.; Chew, E.P. Emerging Technology and Management Research in the Container Terminals: Trends and the COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts. Ocean Coast Manag 2022, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.N.; Kim, H. The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Connectivity, Operational Efficiency, and Resilience of Major Container Ports in Southeast Asia. J Transp Geogr 2024, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, L.; Gendron-Carrier, N.; Rua, G. The Local Impact of Containerization. J Urban Econ 2021, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Rosal, I.; Moura, T.G.Z. The Effect of Shipping Connectivity on Seaborne Containerised Export Flows. Transp Policy (Oxf) 2022, 118, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.-H.; Noh, C.-K. A Case Study of Automation Management System of Damaged Container in the Port Gate. Journal of Navigation and Port Research 2017, 41, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovlev, S.; Eglynas, T.; Voznak, M.; Jusis, M.; Partila, P.; Tovarek, J.; Jankunas, V. Detection of Physical Impacts of Shipping Containers during Handling Operations Using the Impact Detection Methodology. J Mar Sci Eng 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styliadis, T.; Chlomoudis, C. Analyzing the Evolution of Concentration within Containerized Transport Chains through a Circuitist Approach: The Role of Innovations in Accelerating the Circuits of Liner and Container Terminal Operators. Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics 2021, 37, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovlev, S.; Eglynas, T.; Jusis, M.; Voznak, M.; Partila, P.; Tovarek, J. Detecting Physical Impacts to the Corners of Shipping Containers during Handling Operations Performed by Quay Cranes. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Fan, L.; Xu, D.; Ding, Y.; Gen, M. Research on Coupling Scheduling of Quay Crane Dispatch and Configuration in the Container Terminal. Comput Ind Eng 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovlev, S.; Eglynas, T.; Voznak, M. Application of Neural Network Predictive Control Methods to Solve the Shipping Container Sway Control Problem in Quay Cranes. IEEE Access 2021, XX, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovlev, S.; Eglynas, T.; Voznak, M.; Jusis, M.; Partila, P.; Tovarek, J.; Jankunas, V. Detecting Shipping Container Impacts with Vertical Cell Guides inside Container Ships during Handling Operations. Sensors (Switzerland) 2022, 22, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, A.; Nishimura, E.; Papadimitriou, S. Marine Container Terminal Configurations for Efficient Handling of Mega-Containerships. Transp Res E Logist Transp Rev 2013, 49, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, N.; Stahlbock, R.; Voß, S. A Decision Model on the Repair and Maintenance of Shipping Containers. Journal of Shipping and Trade 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carn, J. Smart Container Management: Creating Value from Real-Time Container Security Device Data. 2011 IEEE International Conference on Technologies for Homeland Security, HST 2011 2011, 457–465. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.; Hasan, R.; Ullah, A.; Sarker, K.U. SMART Security Alert System for Monitoring and Controlling Container Transportation. 2019 4th MEC International Conference on Big Data and Smart City, ICBDSC 2019 2019. [CrossRef]

- White_Paper - Nexxiot - Smart Containers_Safe, Secure and Compliant Supply Chains.

- Tovarek, J.; Partila, P.; Jakovlev, S.; Voznak, M.; Eglynas, T.; Jusis, M. A New Approach for Early Detection of Biological Self-Ignition in Shipping Container Based on IoT Technology for the Smart Logistics Domain. In Proceedings of the Proceeding of the 29th Telecommunications Forum (TELFOR 2021); IEEE, 2021.

- Beaumont, P. Cybersecurity Risks and Automated Maritime Container Terminals in the Age of 4IR. In; 2018; pp. 497–516.

- Gunes, B.; Kayisoglu, G.; Bolat, P. Cyber Security Risk Assessment for Seaports: A Case Study of a Container Port. Comput Secur 2021, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, J.; Tang, L. Research on the Model of Risk Identification of Container Logistics Outsourcing Based Factor Analysis. 2008 IEEE International Conference on Service Operations and Logistics, and Informatics 2008, 1680–1685. [CrossRef]

- Budiyanto, M.A.; Fernanda, H. Risk Assessment of Work Accident in Container Terminals Using the Fault Tree Analysis Method. J Mar Sci Eng 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Qu, Z.; An, C.; Zhang, B.; Lee, K.; Bi, H. Emerging Marine Pollution from Container Ship Accidents: Risk Characteristics, Response Strategies, and Regulation Advancements. J Clean Prod 2022, 376, 134266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Li, D.; Bian, J.; Zhang, Y. Airfreight Forwarder’s Shipment Planning: Shipment Consolidation and Containerization. Comput Oper Res 2024, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritime, N.K. RFID-Based RTLS for Improvement of Operation System in Container Terminals. 2006, 00, 1–5.

- Chang, C.H.; Xu, J.; Song, D.P. An Analysis of Safety and Security Risks in Container Shipping Operations: A Case Study of Taiwan. Saf Sci 2014, 63, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovlev, S.; Voznak, M. Auto-Encoder-Enabled Anomaly Detection in Acceleration Data: Use Case Study in Container Handling Operations. Machines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovlev, S., Eglynas, T., Jusis, M., Gudas, S., Jankunas, V. and Voznak, M. Use Case of Quay Crane Container Handling Operations Monitoring Using ICT to Detect Abnormalities in Operator Actions. Proceedings ofthe 6th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems (VEHITS 2020) 2020, 63–67. [CrossRef]

- Jakovlev, S.; Eglynas, T.; Jankunas, V.; Voznak, M.; Jusis, M.; Partila, P.; Tovarek, J. Statistical Evaluation of the Impacts Detection Methodology (IDM) to Detect Critical Damage Occurrences during Quay Cranes Handling Operations. Machines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Skinner, B.T.; Huang, S.; Liu, D.K.; Dissanayake, G.; Lau, H.; Pagac, D.; Pratley, T. Mathematical Modelling of Container Transfers for a Fleet of Autonomous Straddle Carriers. 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation 2010, 1261–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelareh, S.; Merzouki, R.; McGinley, K.; Murray, R. Scheduling of Intelligent and Autonomous Vehicles under Pairing/Unpairing Collaboration Strategy in Container Terminals. Transp Res Part C Emerg Technol 2013, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahnes, N.; Kechar, B.; Haffaf, H. Cooperation between Intelligent Autonomous Vehicles to Enhance Container Terminal Operations. Journal of Innovation in Digital Ecosystems 2016, 3, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.I.; Jula, H.; Vukadinovic, K.; Ioannou, P. Automated Guided Vehicle System for Two Container Yard Layouts. Transp Res Part C Emerg Technol 2004, 12, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.-H.; Lim, D.-S.; Nam, K.-C. An Economic Analysis of Transportation Equipments at Container Terminals. Journal of Navigation and Port Research 2011, 35, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, O.; Huynh, N. Storage Space Allocation at Marine Container Terminals Using Ant-Based Control. Expert Syst Appl 2013, 40, 2323–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White Paper Smart Containers Real-Time Smart Container Data for Supply Chain Excellence The United Nations Centre for Trade Facilitation and Electronic Business (UN/CEFACT) Simple, Transparent and Effective Processes for Global Commerce.

- Ting, S.L.; Wang, L.X.; Ip, W.H. A Study of RFID Adoption for Vehicle Tracking in a Container Terminal. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management 2012, 5, 22–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Bureau of Shippins Certification of Container Securing Systems; 2021.

- Caballini, C.; Gracia, M.D.; Mar-Ortiz, J.; Sacone, S. A Combined Data Mining – Optimization Approach to Manage Trucks Operations in Container Terminals with the Use of a TAS: Application to an Italian and a Mexican Port. Transp Res E Logist Transp Rev 2020, 142, 102054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Study on the Cost Allocation of the Container Terminal Operator Coalition through a Game-Theoretic Approach: Focusing on Busan New Port. Journal of Korean Navigation and Port Reserch 2020, 44.

- Yi, M.S.; Lee, B.K.; Park, J.S. Data-Driven Analysis of Causes and Risk Assessment of Marine Container Losses: Development of a Predictive Model Using Machine Learning and Statistical Approaches. J Mar Sci Eng 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cause of Damage | Statistic | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Improper packing and securing | 65% of cargo damage claims are due to poor packing and securing | Officially provided by the Global Trade Magazine “https://globaltrademag.com/” |

| Physical damage during handling | 25% of cargo damages are attributed to physical handling damage | Officially provided by the IFA Forwarding “https://ifa-forwarding.net/” |

| Containers lost overboard | 11% of cargo damage claims are due to containers lost at sea | Officially provided by the Container xChange “https://www.container-xchange.com/” |

| Temperature-related damages | 14% of cargo damages are due to incorrect temperature | Officially provided by the IFA Forwarding “https://ifa-forwarding.net/” |

| Theft-related damages | 9% of cargo damages are due to theft | Officially provided by the IFA Forwarding “https://ifa-forwarding.net/” |

| Shortage-related damages | 8% of cargo damages are due to shortages | Officially provided by the IFA Forwarding “https://ifa-forwarding.net/” |

| Maritime incidents in ports and terminals | 2,400 incidents recorded in 2022; ~50% occurred within port boundaries | Officially provided by the Port Technology “https://www.porttechnology.org/” |

| Incidents at berth or harbor | 813 incidents occurred while docked in ports and harbors in 2022 | Officially provided by the Port Technology “https://www.porttechnology.org/” |

| APM Terminals incidents | Over 1,200 incidents reported globally in 2019 | Officially provided by the BoxOnWheel “https://boxonwheel.com/” |

| Unreported container damages | Minor damages can reduce container value by 2–5%; many incidents go unreported | Officially provided by the Identec Solutions “https://www.identecsolutions.com/” |

| Average annual containers lost at sea | Approximately 1,382 containers lost annually between 2008 and 2019 | Officially provided by the Standard Club “https://www.standard-club.com/” |

| Adverse weather as cause of container loss | 57.14% of container loss incidents attributed to adverse weather conditions | Yi et al., [41] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).