1. Introduction

The construction industry is a key driver of national development, especially in rapidly urbanizing regions like the Gulf states. While it contributes to infrastructure growth and job creation, the sector faces persistent challenges, including project delays, cost overruns, labor inefficiencies, and safety risks. To address these persistent issues, there is growing interest in integrating advanced technologies that can improve construction outcomes and asset longevity. One such innovation is Structural Health Monitoring (SHM), which enables the real-time assessment of infrastructure through data-driven insights supporting timely maintenance and structural safety. Moreover, SHM ensures the safety and serviceability of critical structures like bridges, high-rise buildings, and industrial facilities through continuous monitoring and condition assessment.

For better and more efficient SHM applications, it was found that the transition from traditional manual inspection methods to automated, intelligent systems powered by robotics offers significant advantages in terms of efficiency, coverage, and reliability [

1,

2]. Robotic technologies are emerging as key enablers in SHM, can access hard-to-reach or dangerous areas, perform repetitive tasks with precision, and transmit real-time data to support predictive maintenance decisions [

3,

4]. Moreover, robotics and automation offer a safer, more accurate, and more efficient alternative to manual inspections. These technologies enable high-precision monitoring in hazardous or hard-to-reach areas and, when combined with artificial intelligence (AI), facilitate predictive diagnostics for proactive infrastructure management. Therefore, the integration of robotics into SHM is increasingly recognized as a transformative approach in the field of infrastructure management.

Given the growing interest in this emerging field, a preliminary literature review is essential to guide future research and establish a solid foundation for scholarly exploration. To date, and to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no systematic or critical reviews have been conducted on this topic, underscoring a significant gap in literature. This paper addresses that gap by providing a basic overview of the integration of robotics in SHM with a particular emphasis on the Saudi Arabian construction sector. It examines the key technological, institutional, and contextual factors influencing adoption, thereby laying the groundwork for the study’s subsequent empirical investigation. The paper concludes with a set of well-informed recommendations for future research, offering potential research directions to support and inspire scholars and practitioners interested in advancing this critical area of study.

2. Overview of SHM in Structures

2.1. Concept and Components of SHM

SHM refers to the systematic observation and interpretation of sensor-based data to evaluate the condition and performance of civil structures over time. It plays a central role in ensuring infrastructure integrity by enabling continuous or periodic assessment through integrated sensor networks and intelligent data-processing systems. These components typically include data acquisition units, communication systems, and computational models that support maintenance decisions and safety evaluations.

Recent advancements have improved SHM systems with advanced sensors and wireless communication. SHM applications now use a variety of sensors, including piezoelectric transducers, fiber optics, and vibration sensors, with data management platforms for real-time diagnostics and monitoring. As Wang and Ke (2024) mentioned, this integration can do early fault detection and automated decision making [

2]. The overall architecture supports predictive maintenance, no need for manual inspection, and extends the life and functionality of the infrastructure.

2.2. Importance of Early Defect Detection in Structures

Early detection of structural defects is key to long-term performance and safety of infrastructure systems. Undetected issues like cracks, delamination, or corrosion can escalate into critical failures, pose safety risks, and cost a lot of repairs. SHM systems provide a proactive monitoring framework for stakeholders to track performance indicators and structural anomalies at an early stage.

Scuro et al. (2021) said that combining SHM with real-time data acquisition and wireless communication allows for timely intervention strategies [

5]. This minimizes unexpected downtime and allows for better maintenance planning. As infrastructure ages and gets more loaded, early detection of defects is key to serviceability and public safety.

2.3. Benefits of SHM in Improving Infrastructure Durability and Safety

SHM contributes to infrastructure durability by giving insight into the evolving physical state of the materials and load-bearing components. Through continuous feedback, engineers can monitor stress distribution, fatigue accumulation, and material degradation and make precise interventions to reinforce or retrofit vulnerable areas.

Yue et al. (2021) showed how SHM systems support performance-based maintenance and reduce unnecessary repairs by providing data that reflects the actual structural condition [

6]. From a safety perspective, SHM systems are essential in areas prone to dynamic stressors such as seismic zones or heavy traffic corridors. Real-time monitoring facilitates rapid decision-making and emergency responses, thereby reducing risks to human life and property.

2.4. Applications of SHM in Structures

SHM is widely applied across various sectors, including transportation, energy, and public infrastructure. In bridge engineering, it is used to monitor load effects, displacement, and fatigue. In high-rise buildings and sports arenas, it ensures dynamic stability under operational conditions. These applications enhance the reliability, value, and risk management of critical assets.

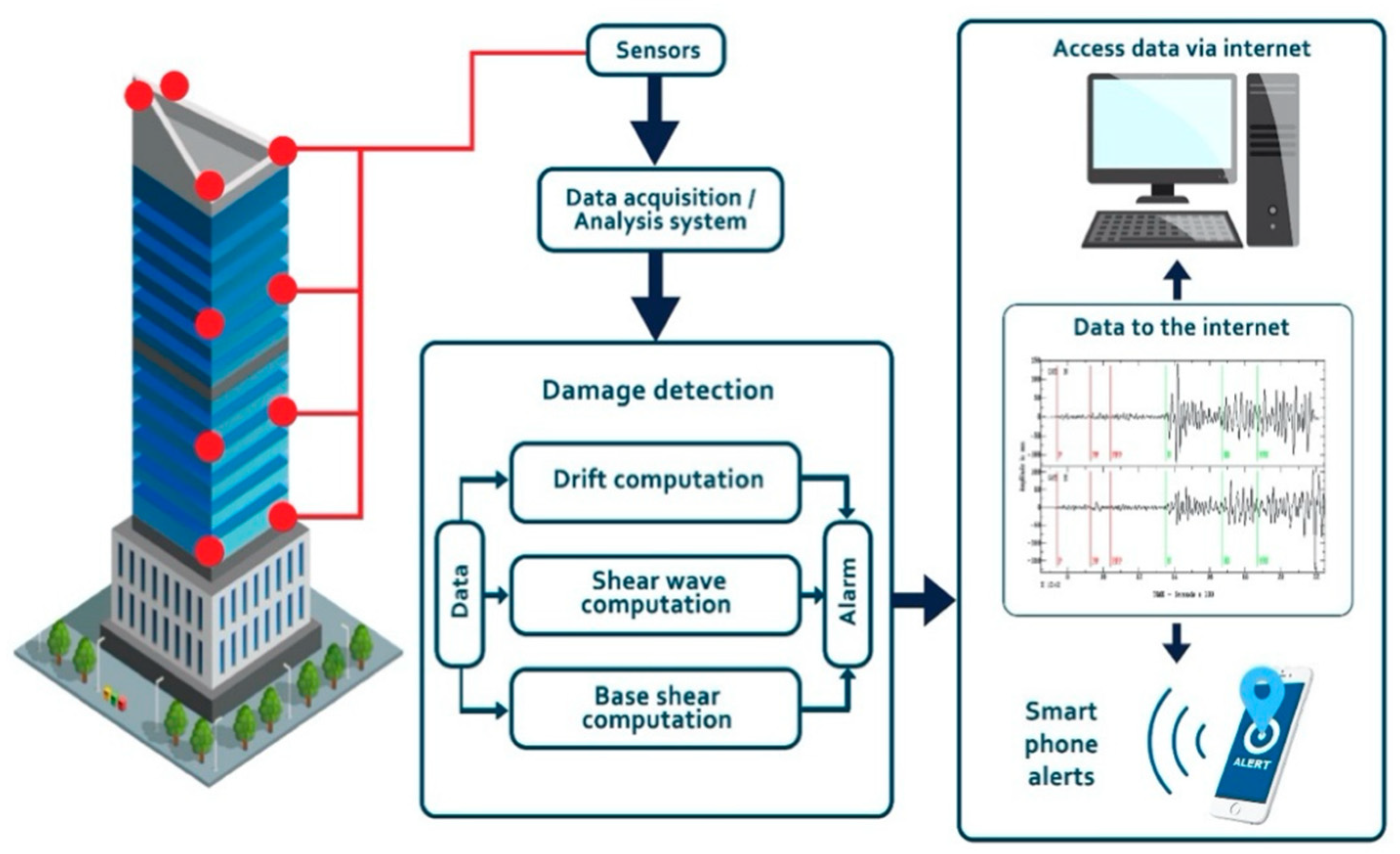

Figure 1 illustrates the functioning process of SHM in high-rise buildings.

Additionally, SHM is being adopted in smart cities and sustainable construction practices, where digital technologies are used to model and optimize infrastructure systems. Figueiredo and Brownjohn (2022) highlighted the evolution of SHM in bridge systems using statistical pattern recognition, underscoring its role in managing aging infrastructure and optimizing long-term investment [

8]. The ability to adapt SHM solutions to diverse materials and structural forms further enhances their applicability across infrastructure types.

2.5. Limitations of Conventional Inspection Methods

Traditional inspection approaches, such as visual checks and periodic manual testing, are constrained by their dependence on human judgment, limited access to structural components, and lack of continuous monitoring. These methods are less effective in detecting hidden or progressive damage and often require service interruptions to conduct thorough inspections.

As noted in the literature, these limitations have led to the increasing adoption of SHM systems, which offer more objective, efficient, and data-driven assessments. SHM not only enhances detection accuracy but also reduces labor and safety risks associated with inspections in hazardous or elevated areas. These advantages make sensor-based SHM a superior alternative for modern infrastructure monitoring and asset management.

2.6. Emerging Role of Robotics in Defect Detection

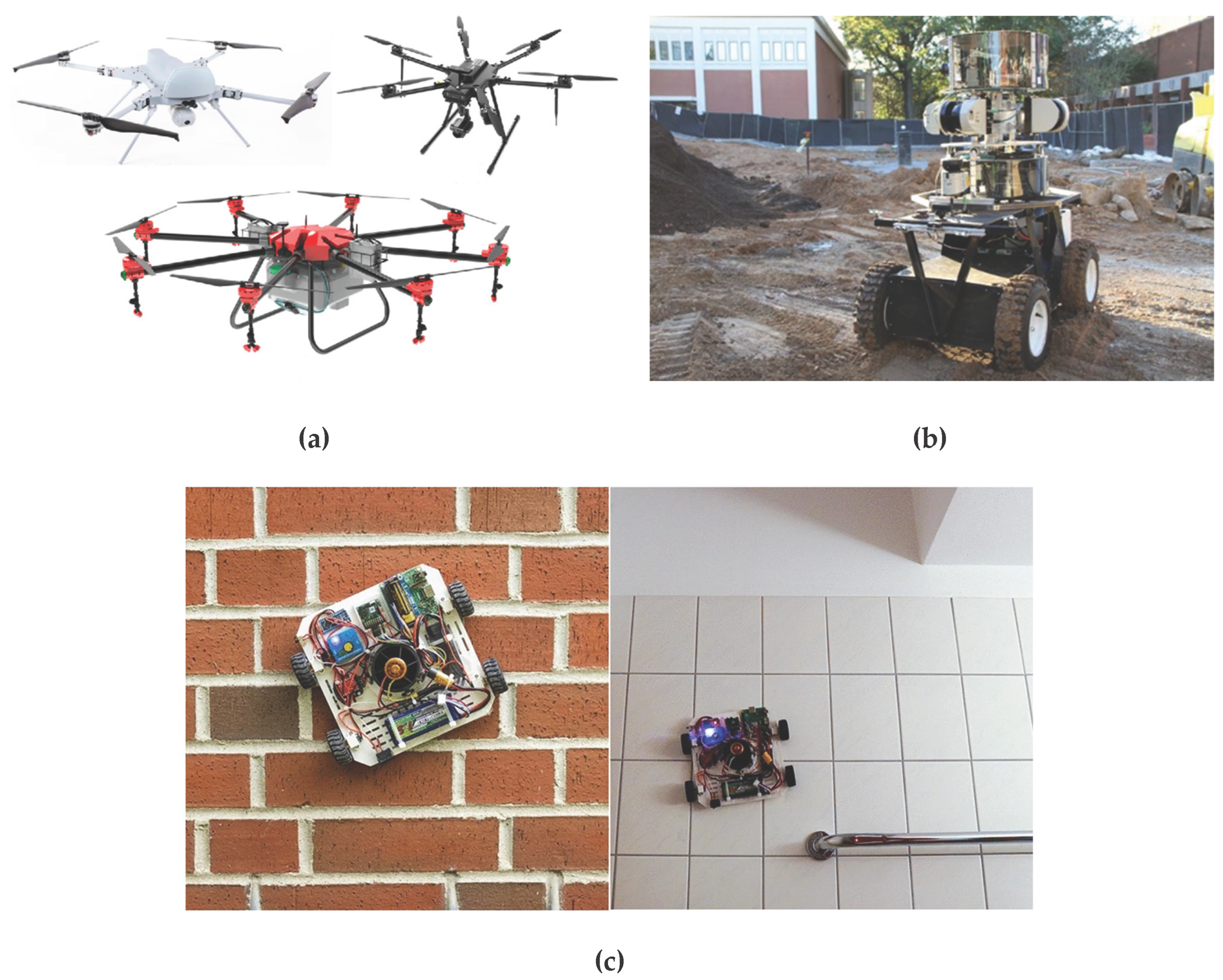

The integration of robotic technologies with SHM frameworks represents a transformative advancement in infrastructure monitoring. Robots, such as UAVs, wall-climbing units, and mobile ground vehicles (

Figure 2), can navigate challenging or hazardous environments and collect high-resolution data using onboard sensors.

These robotic systems enhance SHM by automating inspection tasks, reducing human involvement in risky operations, and enabling more frequent and consistent data collection. When combined with intelligent algorithms, robotic platforms can classify defects, generate alerts, and support predictive analytics in real time. This convergence marks a shift toward fully automated, intelligent infrastructure monitoring, especially valuable in large-scale or remote installations.

3. Robotics and Automated Systems for SHM

3.1. Rigid Robotic Systems for Surface/Subsurface Defect Inspection

Rigid robotic systems, such as unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs), wall-climbing robots, cable-climbing units, and aerial drones, are transforming the field of SHM by automating visual and non-visual inspections. These platforms are equipped with high-res optical sensors, laser scanners, infrared cameras, and ultrasonic transducers to detect and characterize surface-level and embedded defects, including cracks, corrosion, delamination, and internal voids.

Tian et al. (2022) showed how intelligent robotic systems with AI and adaptive control can autonomously localize defects in complex environments [

3]. Drones have become a common tool for inspecting tall structures and large-span bridges as they are maneuverable and can capture high-resolution data without interrupting normal operations. They reduce inspection time and cost and increase worker safety.

Wall climbing robots like those described by Górski et al. (2025) use magnetic wheels or vacuum adhesion to climb vertical surfaces and are ideal for inspecting high-rise facades, dams or steel pylons [

12]. Their precise movement and stabilization systems allow for close-range inspection of defects that are hard to see or detect through remote sensing alone. Similarly, cable-climbing robots have become the optimal solution for inspecting suspension cables and stay cables in bridge structures where traditional methods are hazardous or impractical. The rigidity of these platforms ensures stable sensor deployment, which is critical for defect quantification and high-resolution data acquisition.

Adding real-time communication modules to these robotic systems allows data to be transmitted in real-time for analysis and makes them key to predictive and condition-based maintenance. This is a shift from reactive to proactive asset management in civil infrastructure.

3.2. Mobile, Climbing Robots and Drones for Dynamic Response Measurement

Robotic platforms are being used not only for visual inspections but also for capturing dynamic responses of structures under operational or environmental loads. Ground-based mobile robots can navigate indoor and outdoor structural environments autonomously with sensors such as accelerometers, gyroscopes, and strain gauges. These systems collect data on displacement, modal frequencies, damping ratios, and other vibrational properties so engineers can see real-time structural behavior and detect anomalies such as resonance or fatigue.

Atencio et al. (2022) introduced robotic process automation (RPA) in SHM to automate data workflows in dynamic environments [

13]. These technologies, when integrated with mobile robots, enable continuous vibration monitoring and automated data preprocessing, significantly reducing the time and expertise required for data interpretation.

Flying drones and climbing robots can be deployed in environments that are challenging for mobile ground robots, such as tall towers, bridge pylons, or narrow shafts. According to Hu and Assaad (2023), drones equipped with inertial measurement units (IMUs) and real-time kinematic (RTK) GPS systems offer precise positioning and vibration sensing capabilities [

14]. These systems can be deployed immediately after extreme events such as earthquakes or storms to assess structural responses, making them valuable tools for rapid post-disaster evaluation.

Johann et al. (2024) discussed the validation of robot-enabled embedded sensors in civil structures, demonstrating that robotic platforms can not only collect dynamic data but also interact with embedded systems to trigger alarms or adjust monitoring parameters [

15]. This integration enables dynamic SHM with enhanced adaptability and real-time diagnostic capabilities, supporting both short-term incident response and long-term performance monitoring.

3.3. Multimodal Rigid Robots and Soft Wall-Climbing Robots

Recent technological advances have led to the emergence of multimodal robotic systems capable of switching between locomotion types, such as flying, rolling, crawling, or climbing, depending on the inspection environment. These robots are designed to navigate a wide range of structural contexts and can carry diverse sensor arrays, including visual, thermal, acoustic, and electromagnetic devices. This adaptability makes them particularly effective for inspecting hybrid structures or infrastructure composed of different materials and geometries.

Tian et al. (2022) emphasized the modular architecture of intelligent robotic systems, which allows users to customize sensor payloads based on specific inspection requirements [

3]. This flexibility reduces the need for multiple separate devices, enabling more comprehensive evaluations in a single deployment. Such robots are also beneficial for inspecting inaccessible or hazardous areas, enhancing worker safety and reducing inspection costs.

In parallel, soft robotics has introduced new possibilities for inspecting sensitive or historically significant structures. Soft wall-climbing robots, as examined by Hu and Assaad (2023), use flexible bodies and biomimetic adhesion mechanisms, such as suction cups, electro-adhesion pads, or gecko-inspired feet, to traverse delicate or irregular surfaces [

14]. Their lightweight and compliant designs reduce the risk of damaging fragile surfaces, making them ideal for use in heritage buildings, curved facades, or prestressed concrete elements.

These soft robots are also inherently safer for human interaction and can conform to complex surface geometries that are challenging for rigid systems. Their integration with real-time sensing and AI-driven defect recognition enables them to operate autonomously, map structural anomalies with high precision, and contribute to long-term preservation strategies.

3.4. Future Outlook: Toward Intelligent and Cooperative SHM Robotics

The future of robotics in SHM lies in the development of intelligent, cooperative, and autonomous systems that can operate collaboratively in multi-agent frameworks. As discussed by Gkoumas et al. (2021), the integration of connected vehicles, Internet of Things (IoT) technologies, and cloud-based analytics will allow SHM robots to share information across systems and adapt their operations based on collective intelligence [

16]. This indirect SHM (iSHM) approach expands monitoring capabilities beyond single-infrastructure assets, enabling large-scale, network-wide health assessments.

Through cloud-connected platforms, real-time decision-making, and robotic swarming techniques, SHM systems are expected to become more predictive, self-organizing, and capable of continuous infrastructure surveillance across urban environments. These capabilities will play a vital role in the context of smart cities, infrastructure digital twins, and sustainable development planning.

4. Application of Robotics for SHM

4.1. Robots for Defect Inspection

Robotic systems have become indispensable in detecting both surface-level and internal defects within civil and specialized infrastructure. These systems facilitate safe, efficient, and non-intrusive assessments across a range of environments, including bridges, high-rise buildings, tunnels, and offshore structures. Surface inspections commonly utilize unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and wall-climbing robots equipped with high-resolution visual, infrared, or multispectral imaging systems. These robots enable rapid, non-contact inspection of large and complex surfaces, such as façades, bridge decks, and wind turbine blades.

Gupta (2023) emphasizes the growing role of UAVs in marine structure inspection, where guided wave sensors and advanced imaging tools are mounted on drones to detect corrosion, cracking, and delamination in environments that are otherwise difficult or dangerous to access [

17]. Wall-climbing robots, often employing suction-based, magnetic, or biomimetic adhesion systems, can conduct close-up inspections on vertical and curved surfaces. These platforms are especially valuable in urban settings and confined locations where scaffolding or human access is limited.

For internal and subsurface defect detection, cable-climbing and ground mobile robots equipped with nondestructive evaluation (NDE) tools, such as ultrasonic transducers, acoustic emission sensors, or electromagnetic-based scanners, have proven effective. Mazzeschi (2024) highlights the role of electromagnetic testing in aerospace structures, which is increasingly being adapted for civil applications through robotic deployment [

18]. These systems can identify hidden anomalies such as delamination, internal voids, and rebar corrosion with high precision. Operated remotely or semi-autonomously, these robots also enhance worker safety by operating in hazardous zones, such as aging tunnels, underwater piers, or seismic-damaged assets.

Their sensor integration and high data acquisition rates not only enhance diagnostic accuracy but also support real-time decision-making. By reducing reliance on manual inspection, robotic systems in defect detection streamline maintenance workflows and contribute significantly to proactive infrastructure management.

4.2. Robots for Vibration Measurement (e.g., Acceleration, Displacement)

Measuring vibration responses is a cornerstone of SHM, providing essential insights into the dynamic behavior and integrity of structural systems under operational or environmental loads. Robotic platforms have emerged as highly effective tools in this domain, capable of collecting data on acceleration, displacement, velocity, and modal frequency from locations that are often inaccessible or unsafe for manual instrumentation.

Unlike static sensor networks that are fixed in place, mobile robotic systems offer spatial flexibility and targeted measurements across different parts of a structure. Mahairi (2021) demonstrated the use of semi-active vibration suppression in manufacturing robots, highlighting the potential of such robotic systems to monitor and even modulate vibrations in complex environments [

19]. These principles are now being extended to civil infrastructure, where mobile robots are deployed to scan structural elements using inertial measurement units (IMUs), accelerometers, and displacement sensors.

Ground-based robots are often utilized to measure vibrations on flat decks, floors, and interior structural components. For vertical or inclined surfaces, wall-climbing robots provide direct access, capturing high-resolution dynamic data critical for fatigue monitoring or damage localization. UAVs, on the other hand, are suited for high-elevation inspections, such as bridge cables, wind towers, and façade-mounted components, where they can hover and capture vibration data under ambient or controlled excitations.

Deng (2021) introduced magnetorheological dampers with variable stiffness and damping characteristics, which were integrated into robotic arms to enhance their response to dynamic loads [

20]. This technology exemplifies how vibration-adaptive robotics can be leveraged not only for monitoring but also for interactive control during SHM tasks. Additionally, displacement sensors integrated into drones and climbing robots enable modal identification and structural resonance evaluation, thereby enhancing diagnostic depth.

Cable-climbing robots, specifically designed for suspension elements, can move along bridge cables or hangers to assess dynamic behavior and tension-related properties. These platforms offer a safer and more scalable alternative to manual rope access or scaffolding.

The use of robotic systems for vibration monitoring enhances spatial resolution, repeatability, and safety. Their flexibility in accessing diverse structural elements and collecting detailed dynamic data makes them vital to comprehensive SHM strategies.

Table 1 provides a summary of robotic platforms used in vibration monitoring, outlining their sensing mechanisms, deployment environments, and core functionalities.

5. Challenges in Adopting Robotics for SHM

5.1. Technological Readiness

Technological readiness refers to a nation’s or industry’s capacity to adopt and integrate advanced robotics into its infrastructure monitoring practices. This includes not only access to robotic technologies and intelligent sensors but also the availability of skilled personnel, data integration platforms, and standardized operational protocols. In regions like Saudi Arabia, this readiness is influenced by disparities in digital maturity across firms, limited local manufacturing of robotic components, and the nascentness of SHM-focused innovation ecosystems.

Tian et al. (2022) emphasized that although intelligent robotic systems are becoming increasingly available for SHM globally, their deployment in emerging markets is often hindered by integration challenges with legacy infrastructure and limited sensor-robot interoperability [

3]. Similarly, Johann et al. (2024) noted that embedding sensors into existing structures via robotics requires technical know-how, stable communication networks, and standardized calibration procedures, capabilities that are still evolving in many local contexts [

15].

In the Saudi construction sector, small and medium-sized enterprises often lack the in-house technical expertise required for robotic operation and maintenance, thereby slowing the adoption of robotics. As Górski et al. (2025) noted, the sophistication of climbing and mobile robotic systems necessitates a digitally skilled workforce and supportive training infrastructure, elements still under development in many regions [

12]. Without coordinated investments in research, development, and education, the gap between technological availability and practical implementation persists as a significant barrier.

5.2. Regulatory and Governmental Support

The successful integration of robotics into SHM practices depends heavily on the presence of a supportive regulatory environment. Clear regulations are needed to define operational boundaries, safety standards, inspection procedures, and data governance for autonomous systems operating in public or critical infrastructure spaces.

According to Gkoumas et al. (2021), the absence of harmonized standards for robotic SHM has slowed the deployment of such systems in Europe, despite technological maturity [

16]. This concern is mirrored in regions like the Gulf, where comprehensive robotic regulations, particularly in high-risk sectors such as bridges, tunnels, and airports, are still being developed. Particularly, issues such as UAV licensing, robotic autonomy levels, and liability in the case of failure remain undefined in many jurisdictions.

Atencio et al. (2022) stressed the importance of institutional alignment between regulatory bodies, technology providers, and infrastructure managers to facilitate SHM deployment at scale [

13]. Without clear inspection mandates and enforcement protocols, project owners and contractors often hesitate to invest in robotic systems, fearing non-compliance or legal uncertainty. Moreover, data protection concerns related to real-time video feeds, vibration signatures, and inspection logs require legislative clarity, mainly when data is transmitted across borders or cloud platforms.

For countries seeking to accelerate the adoption of robotics in SHM, such as Saudi Arabia under Vision 2030, embedding robotics into national construction codes and developing localized standards based on global best practices will be essential to unlocking large-scale implementation.

5.3. Cost and Maintenance

While robotic systems offer long-term efficiencies, the initial investment required to deploy them in SHM applications is often substantial. These costs encompass hardware procurement, software licenses, system integration, and personnel training. Deng (2021) and Mahairi (2021) both highlight that robotic platforms with dynamic sensing and vibration suppression technologies tend to involve complex electronics and control systems, making them more expensive to purchase and operate [

19,

20].

Gupta (2023) also noted that UAV-based SHM solutions in marine environments must be robust, waterproof, and equipped with advanced sensor fusion, all of which contribute to high development and operational costs [

17]. This can be prohibitive for smaller infrastructure projects or firms with limited capital.

In addition to acquisition costs, robotic platforms require ongoing maintenance, sensor recalibration, and regular software updates to ensure optimal performance. Highly specialized personnel are also needed to interpret the collected data, especially when utilizing AI-driven analytics or autonomous navigation systems. Mazzeschi (2024) observed that maintaining electromagnetic-based NDE tools requires regular checks to ensure signal integrity and precision, further increasing lifecycle costs [

18].

Although Hu and Assaad (2023) argue that mobile robots and UAVs can reduce long-term inspection expenditures by decreasing labor and minimizing disruptions, these benefits may not be realized without adequate funding models [

14]. Public-private partnerships and national incentive schemes may therefore be necessary to support early adoption and reduce cost-related resistance in emerging economies.

5.4. Power Supply and Battery Limitations

Energy limitations represent a critical technical challenge in robotic SHM, particularly for systems operating autonomously in remote, vertical, or high-demand environments. As SHM robots rely on batteries to power their mobility, sensors, communication modules, and onboard processors, energy constraints can significantly restrict mission duration and inspection coverage.

Hu and Assaad (2023) emphasize that energy consumption is particularly high during wall climbing and drone flights, which limits operational cycles and requires frequent recharging or battery replacement [

14]. Similarly, Górski et al. (2025) report that many field-deployed robots suffer from insufficient battery capacity, especially when conducting prolonged inspections of tall or inaccessible structures [

12].

Environmental conditions, such as the extreme heat and dust found in many parts of Saudi Arabia, also impair battery efficiency and lifespan. These conditions necessitate specialized thermal control mechanisms and power-hardened components. Mahairi (2021) and Deng (2021) both emphasize the importance of intelligent power management systems within robotic architectures, particularly when robots perform vibration monitoring or dynamic load assessments, which are energy-intensive tasks [

19,

20].

Innovative solutions are emerging to address these constraints. Solar-assisted charging stations, tethered power supplies, and wireless inductive charging technologies are being trialed in experimental SHM applications. For example, Johann et al. (2024) describe the use of hybrid energy systems in robot-enabled sensor platforms, which combine battery power with renewable sources to extend operational endurance. Adapting such solutions for Saudi infrastructure, particularly in coastal and rural areas, could significantly improve the feasibility of continuous robotic monitoring in energy-scarce zones [

15].

5.5. Cross-Sector Insights on Robotics Adoption

To deepen the understanding of robotics adoption challenges in SHM, particularly within the Saudi Arabian construction context, this subsection draws on lessons from other sectors where similar technologies have been implemented. Industries such as healthcare, energy, and public administration offer valuable parallels, highlighting issues of technological readiness, regulatory alignment, stakeholder engagement, and integration complexity. These cross-sectoral insights provide a broader framework for informing future SHM strategies and adoption models. A summary of the key themes and corresponding sectoral insights is shown in

Table 2.

5.5.1. Technological Readiness vs. Real-World Adoption

One common finding across sectors is that high levels of technological maturity, often described using the Technology Readiness Level (TRL) scale, do not automatically translate into widespread adoption. For instance, Östlund et al. (2023) found that despite the advanced TRLs of healthcare robots in Europe, their uptake was hindered by insufficient user engagement, misaligned policies, and lack of institutional preparedness [

25]. This suggests that even when robotics systems are technically viable for SHM applications, as in Saudi Arabia’s smart infrastructure projects, adoption will remain limited unless stakeholders, from operators to regulators, are actively involved and well-trained.

5.5.2. Institutional Capacity and Workforce Alignment

A recurring theme in robotics integration is the importance of institutional and workforce readiness. Mahbub (2012) highlighted in the context of Malaysia’s construction industry that limited awareness, inadequate training, and weak policy support significantly slowed automation uptake [

26]. These findings align closely with the Saudi context, where Vision 2030 outlines digital transformation goals, but operationalizing those goals in the construction sector is often constrained by gaps in digital literacy and workforce skill sets. Hence, the adoption of SHM robotics must be matched by targeted capacity-building and professional development.

5.5.3. Legal Frameworks and Regulatory Preparedness

The legal and regulatory infrastructure remains a critical enabler or barrier to robotics deployment. Holder et al. (2016) and Villaronga (2019) emphasized that the absence of clear accountability frameworks, data governance rules, and safety standards can stall implementation across both public and commercial domains [

27]. These insights underscore a key challenge for SHM in Saudi Arabia: robust legal mechanisms are needed to clarify responsibilities in case of system failure, to regulate autonomous inspections, and to manage data privacy, particularly when real-time structural data is transmitted to cloud platforms or third-party vendors.

5.5.4. Adaptation to Sector-Specific Needs

Lessons from the healthcare sector, as reported by Javaid et al. (2025), reveal that successful integration of robotics depends not just on the robot’s capabilities, but also on its contextual fit [

29]. In SHM, robotic platforms must be adapted to the structural typologies, environmental stresses, and inspection needs of different civil infrastructure systems. This finding supports the argument for designing domain-specific robotic solutions, such as cable-climbing robots for suspension bridges or heat-resistant UAVs for desert installations, rather than attempting to retrofit generalized systems.

5.5.5. Operational Resilience and Energy Management

Energy supply and durability remain universal concerns for mobile robotic systems, especially in field applications. Mikołajczyk et al. (2023a, 2023b) reviewed battery technologies and found that operational longevity is a significant limitation in both indoor and outdoor robotic deployment [

30,

31]. These findings are directly applicable to SHM in Saudi Arabia, where robots are expected to operate in large, remote, and often high-temperature environments. Power management solutions such as hybrid batteries, solar-assisted charging, or wireless inductive systems should therefore be prioritized to ensure uninterrupted inspections and data transmission.

5.5.6. AI Integration and Real-Time Decision Support

Soori et al. (2023) and Kakolu & Faheem (2023) emphasize the value of AI-driven decision-making in robotic applications [

32,

33]. These technologies enhance autonomy, perception, and real-time responsiveness; capabilities that are especially critical in SHM, where early warning and rapid diagnostics can prevent structural failures. In Saudi Arabia, where infrastructure spans seismic zones, coastal regions, and mega-urban developments, integrating AI into SHM robotics can enable predictive maintenance and improve long-term asset performance. However, this also requires robust digital infrastructure, from cloud analytics to edge computing at the sensor level.

5.5.7. Human-Robot Interaction and Change Management

Finally, workforce perception and human-robot collaboration are often overlooked but essential aspects of technology adoption. Campbell et al. (2021) and Kamisetty (2022) discussed how frontline technicians and engineers must accept and trust robotic systems, especially in high-stakes environments like surgical rooms or renewable energy plants [

34,

35]. This parallels the construction sector, where site engineers must feel confident in robotic data, be able to interpret its outputs, and adapt workflows accordingly. Without this cultural and behavioural alignment, even well-designed SHM systems may remain underutilized.

6. Opportunities in Adopting Robotics for SHM

6.1. Accessibility and Safety

One of the most transformative opportunities provided by robotics in SHM is the significant enhancement of accessibility to hard-to-reach, confined, or hazardous environments. Traditional inspection methods often involve human entry into elevated, submerged, or narrow structural zones, which present considerable safety risks and logistical challenges. Robotic systems such as UAVs, cable-climbing platforms, and wall-climbing robots can remotely perform these tasks, drastically reducing the need for physical presence in high-risk areas.

According to Hu and Assaad (2023), mobile ground vehicles and aerial robots have proven especially effective in confined infrastructure environments such as pipelines, high-voltage towers, and tall facades [

14]. These systems eliminate the need for scaffolding, rope access, or mechanical lifts, thereby reducing the risk of accidents and the time required for inspections. Gupta (2023) similarly demonstrated that UAVs equipped with guided wave sensors could safely inspect marine and offshore structures in high-tide zones, where human access is restricted [

17].

The use of robotics also ensures that inspections cover structurally complex geometries, such as curved surfaces, vertical ducts, or submerged assets, with minimal blind spots. Górski et al. (2025) emphasized that robotic tools designed for concrete structures can maneuver with precision and safety in environments that were previously inaccessible [

12]. This capability not only enhances safety standards but also ensures comprehensive inspections, minimizes emergency repairs, and fosters a proactive maintenance culture.

6.2. Efficiency and Accuracy

Robotic systems dramatically improve the efficiency and accuracy of SHM operations. Autonomous platforms can be programmed to follow optimized inspection paths, reducing operational time, eliminating redundancy, and lowering labor costs. These systems can collect continuous, high-resolution data without the inconsistencies associated with manual inspection practices.

Johann et al. (2024) demonstrated how robot-enabled embedded sensor platforms significantly streamline SHM workflows by automating data capture and transmission [

15]. This eliminates the delays associated with manual inspections, enabling faster diagnostic cycles. Atencio et al. (2022) further illustrated how Robotic Process Automation (RPA) in dynamic SHM applications reduces inspection time while maintaining consistent data quality across repeated assessments [

13].

In terms of defect detection accuracy, Mazzeschi (2024) developed electromagnetic-based robotic systems that achieved high detection precision in locating subsurface defects, particularly in structural joints [

18]. These platforms outperform traditional tools due to their ability to filter noise and detect anomalies at the micro level. Moreover, Tian et al. (2022) found that robotic systems integrated with AI-powered image processing can detect small cracks and corrosion with accuracies exceeding those of manual assessments, particularly in repetitive or long-span structures [

3].

The repeatability and objectivity of robotic systems eliminate human error and fatigue-related inconsistencies, making them ideal for long-duration or high-frequency inspections of critical infrastructure assets such as high-speed rail, tunnels, and offshore platforms.

6.3. Data-Driven Decision-Making

Robotic SHM systems serve as powerful enablers of data-driven decision-making by continuously collecting and transmitting real-time structural data to central monitoring systems. These systems integrate sensor data with AI, big data analytics, and Internet of Things (IoT) frameworks to derive actionable insights.

Tian et al. (2022) emphasized that intelligent robotic systems can support predictive maintenance models by analyzing stress, strain, displacement, and other physical metrics [

3]. These inputs feed into advanced decision-making platforms and can be used to create digital twins; virtual representations of real-world structures that respond dynamically to monitoring data. Gkoumas et al. (2021) further highlighted the rise of indirect SHM systems, where data from robotic inspections supports large-scale infrastructure modeling and investment planning [

16].

This level of insight enables the early identification of failure trends, targeted interventions, and more effective resource allocation. Mahairi (2021) noted that integrating vibration data into centralized systems allows engineers to refine modal analysis models and preempt potential structural failures in robotic environments [

19]. Similarly, Deng (2021) emphasized how robotics, integrated with adaptive damping and stiffness models, contributes not only to sensing but also to simulating structural behavior under dynamic loads [

20].

Overall, the use of robotics accelerates SHM transitions from reactive to predictive paradigms, aligning with long-term objectives of infrastructure sustainability and operational efficiency.

6.4. Adaptability to Extreme Conditions

Another significant advantage of robotics in SHM is the ability to operate in extreme and challenging environmental conditions, such as those found in the deserts, coastlines, and industrial zones of Saudi Arabia. Harsh environments characterized by high temperatures, dust exposure, and mechanical vibration pose severe limitations for conventional inspection tools.

Hu and Assaad (2023) demonstrated how UAVs and ground robots designed with heat-resistant coatings, sealed enclosures, and autonomous obstacle-avoidance systems have been successfully deployed in oil refineries and arid pipeline corridors [

14]. These design modifications allow robotic platforms to operate continuously in high-temperature environments without overheating or sensor failure.

Johann et al. (2024) also noted the use of robotic systems with embedded thermal management features and protective casings for long-term monitoring in structurally exposed regions [

15]. These systems show strong resilience in monitoring large-span bridges, desert-based wind farms, and offshore rigs, even under severe thermal or weather-induced stresses.

Furthermore, solar-assisted energy systems and modular battery packs are increasingly used to enhance robotic endurance in power-constrained environments. Deng (2021) proposed vibration-sensitive energy recovery systems that could be adapted to recharge robotic SHM units during movement, further increasing sustainability and reducing the reliance on external power infrastructure [

20].

These innovations confirm the growing adaptability of robotic SHM technologies to diverse and difficult field conditions. Their deployment ensures continuous monitoring of where manual methods would be impractical or unsafe, positioning robotics as a cornerstone of resilient infrastructure asset management.

6.5. SHM in Saudi Arabia’s Construction Sector

The adoption of SHM technologies in Saudi Arabia is accelerating in tandem with the nation’s push toward digital transformation and Construction 4.0 under Vision 2030. Flagship infrastructure initiatives, including smart cities, transportation networks, and coastal developments, are beginning to integrate SHM frameworks that combine AI, robotics, and data-driven diagnostics. As observed by Alsharo et al. (2024), these technologies are being utilized to enable real-time insights into structural performance, optimize maintenance strategies, and align with broader sustainability goals [

36].

Despite promising developments, the application of robotic SHM systems remains limited to select megaprojects and pilot initiatives. According to Masri et al. (2024), while global SHM technologies, such as cable-climbing robots, UAV-based defect inspection, and AI-powered analytics, are rapidly evolving, the Saudi construction sector continues to face challenges in large-scale integration due to gaps in skilled labor, digital readiness, and infrastructure compatibility [

37]. These limitations are particularly apparent in legacy structures that lack embedded sensor networks or designs that are retrofit-friendly.

Nevertheless, government-led reforms and strategic investments are laying the groundwork for more widespread adoption. As noted by Khahro & Khahro (2024), national policy frameworks are increasingly recognizing the role of intelligent monitoring technologies in occupational safety and infrastructure resilience [

38]. The integration of SHM into safety governance models and smart project planning aligns directly with Saudi Arabia’s aim to reduce workplace risks, improve compliance, and enhance lifecycle asset performance.

The Saudi Vision 2030 initiative identifies SHM as a key enabler for infrastructure modernization, particularly through the development of AI-enhanced and autonomous systems. Alsharo et al. (2024) describe the emergence of AI-based digital twin frameworks that connect sensor networks to cloud-based platforms for live structural simulation, risk prediction, and resource optimization [

36]. These advancements are directly contributing to the country’s goal of establishing smart cities and sustainable construction ecosystems.

Several high-profile Saudi projects serve as national benchmarks for SHM innovation:

NEOM, the futuristic $500 billion smart city under development, is integrating robotics, digital twins, and autonomous UAVs for continuous monitoring of structural assets. According to Al Masri et al. (2024), NEOM is leveraging Construction 4.0 tools to support predictive maintenance and autonomous inspections, setting a global precedent for robotics in infrastructure development.

The Red Sea Project demonstrates how SHM can be used to meet environmental and regulatory standards. Alsharo et al. (2024) note that the project employs AI-powered sensors and robotic inspection platforms to monitor marine infrastructure such as piers, bridges, and jetties [

36]. These systems not only assess structural health but also ensure ecological preservation in sensitive coastal environments.

The Riyadh Metro provides a prominent example of SHM integration in urban transit. Robotic systems and fixed sensors continuously monitor tunnel deformation, vibration levels, and thermal expansion in real-time. Data collected through these platforms feeds into centralized operational dashboards, enabling predictive maintenance and enhancing passenger safety. This approach aligns with Johann et al. (2024), who emphasizes the role of embedded robotics and sensor fusion in optimizing infrastructure performance in high-density environments [

15].

Collaborative initiatives with academic institutions, public-private partnerships, and digital infrastructure funds also reinforce Saudi Arabia’s investment in SHM. Alsharo et al. (2024) highlights how research grants are now being directed toward localizing SHM technologies, customizing robotics for desert and coastal conditions, and aligning national standards with global safety and sustainability benchmarks [

36].

SHM’s contribution extends beyond technical efficiency; it supports broader objectives such as climate adaptation, material optimization, and circular construction. By reducing unplanned repairs, extending asset life cycles, and minimizing material waste, SHM is directly aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those concerning resilient infrastructure and sustainable cities.

In summary, Saudi Arabia is moving from exploratory SHM applications toward strategic implementation in high-value projects. Robotics, AI, and smart data platforms are no longer viewed as futuristic options but as critical tools for realizing Vision 2030’s infrastructure modernization and sustainability ambitions. Continued investment in localized innovation, regulation, and workforce training will be essential to scaling these technologies across the construction sector.

7. Conclusions

This review aimed to provide a brief overview of the integration of robotics into Structural Health Monitoring (SHM), with a specific focus on the challenges and opportunities in the Saudi Arabian construction sector. The analysis highlighted that while robotic technologies offer transformative potential in improving inspection efficiency, safety, and data-driven maintenance, several barriers remain, namely, technological readiness, workforce capacity, regulatory gaps, and cost-related limitations. These challenges are particularly pronounced in developing contexts, where digital infrastructure and policy frameworks are still in the process of evolving.

The paper synthesized insights from both SHM-specific literature and cross-sectoral case studies to provide a multidimensional understanding of robotics adoption. It outlined how sectors such as healthcare, law, and renewable energy offer relevant lessons in areas such as artificial intelligence (AI) integration, legal governance, and stakeholder acceptance. The review also identified several enabling factors, including increased safety in hazardous environments, improved defect detection accuracy, and the potential for intelligent, autonomous monitoring systems aligned with smart city ambitions.

In the context of Saudi Arabia, the review emphasized that national initiatives under Vision 2030 are creating fertile ground for the broader deployment of robotic SHM technologies. Flagship projects, such as NEOM and the Riyadh Metro, demonstrate early integration successes, while ongoing investments in digital transformation, sustainability, and workforce development are expected to support scalable adoption.

Overall, this review offers a foundational reference for researchers and practitioners aiming to navigate the technical, organizational, and regulatory landscape of robotic SHM. It also paves the way for future empirical investigations and innovation in intelligent infrastructure monitoring across the Gulf region and beyond.

8. Recommendations for Future Work

Based on the literature reviewed in this paper, it is evident that there are still numerous research gaps that need to be addressed to further advance the understanding and application of robotics for SHM in construction in Saudi Arabia. The following are some recommendations for researchers interested in addressing these gaps and expanding this field of research:

Conduct longitudinal studies to track robotics adoption over time and assess how organizational readiness, technology performance, and policy changes influence long-term integration and impact in SHM operations.

Differentiate between types of robotic systems, such as UAVs (drones), ground-based robots, or fixed sensor networks, to explore how adoption dynamics vary by functionality, complexity, and use case.

Assess external macro-environmental factors, such as global supply chain disruptions, vendor availability, and international technology transfer policies, which may affect the accessibility and sustainability of robotics in the Saudi Arabian construction sector.

Study the economic and environmental impact of robotics integration in SHM by examining cost-benefit ratios, return on investment, and carbon footprint reduction over project lifecycles.

Explore workforce implications, including skill shifts, job redesign, and the acceptance of robotics among site engineers and technicians in Saudi Arabia, to gain a deeper understanding of the dynamics of human-robot collaboration.

References

- Laflamme, S.; Ubertini, F.; Di Matteo, A.; Pirrotta, A.; Perry, M.; Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Hoang, T.; Glisic, B.; et al. Roadmap on measurement technologies for next generation structural health monitoring systems. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 093001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ke, J. Literature Review on the Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) of Sustainable Civil Infrastructure: An Analysis of Influencing Factors in the Implementation. Buildings 2024, 14, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, C.; Sagoe-Crentsil, K.; Zhang, J.; Duan, W. Intelligent robotic systems for structural health monitoring: Applications and future trends. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payawal, J.M.G.; Kim, D.-K. A Review on the Latest Advancements and Innovation Trends in Vibration-Based Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) Techniques for Improved Maintenance of Steel Slit Damper (SSD). IEEE Access 2024, 12, 44383–44400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuro, C.; Lamonaca, F.; Porzio, S.; Milani, G.; Olivito, R. Internet of Things (IoT) for masonry structural health monitoring (SHM): Overview and examples of innovative systems. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 290, 123092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, N.; Khodaei, Z.S.; Aliabadi, M.H. Damage detection in large composite stiffened panels based on a novel SHM building block philosophy. Smart Mater. Struct. 2021, 30, 045004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasuriyan, A.; Vijayan, D.S.; Górski, W.; Wodzyński, Ł.; Vaverková, M.D.; Koda, E. Practical Implementation of Structural Health Monitoring in Multi-Story Buildings. Buildings 2021, 11, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, E.; Brownjohn, J. Three decades of statistical pattern recognition paradigm for SHM of bridges. Struct. Heal. Monit. 2022, 21, 3018–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Lee, S.-C.; Bae, W.; Kim, J.; Seo, S. Towards UAVs in Construction: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Directions for Monitoring and Inspection. Drones 2023, 7, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, I.; Jang, Y.; Park, J.; Cho, Y.K. Motion Planning of Mobile Robots for Autonomous Navigation on Uneven Ground Surfaces. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2021, 35, 04021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Hartmann, T. Exploration of using a wall-climbing robot system for indoor inspection in occupied buildings. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górski, M.; Grzyb, K.; Zając, J. Robotic devices for Structural Health Monitoring. Struct. Concr. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atencio, E.; Komarizadehasl, S.; Lozano-Galant, J.A.; Aguilera, M. Using RPA for Performance Monitoring of Dynamic SHM Applications. Buildings 2022, 12, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Assaad, R.H. The use of unmanned ground vehicles (mobile robots) and unmanned aerial vehicles (drones) in the civil infrastructure asset management sector: Applications, robotic platforms, sensors, and algorithms. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 232, 120897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johann, S.; Stührenberg, J.; Tandon, A.; Dragos, K.; Bartholmai, M.; Strangfeld, C.; Smarsly, K. , Implementation and validation of robot-enabled embedded sensors for structural health monitoring. E-Journal of Nondestructive Testing 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoumas, K.; Gkoktsi, K.; Bono, F.; Galassi, M.C.; Tirelli, D. The Way Forward for Indirect Structural Health Monitoring (iSHM) Using Connected and Automated Vehicles in Europe. Infrastructures 2021, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Y. , Structural Health Monitoring of the Marine Structure Using Guided Wave and UAV-based testing, Masters thesis, University of Victoria, 2023.

- Mazzeschi, M. , Development of electromagnetic-based approaches for non-destructive evaluation and health monitoring of aerospace structural joints, Doctoral thesis, Universidad de Valladolid, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mahairi, E. , Semi-Active Vibration Absorbers for Suppressing Vibrations in Manufacturing Robots, Master’s thesis, University of Calgary, 2021.

- Deng, L. , Development of Rotary Variable Damping and Stiffness Magnetorheological Dampers and their Applications on Robotic Arms and Seat Suspensions, Doctoral thesis, University of Wollongong, 2024.

- Nguyen, S.T.; La, H.M. , A Climbing Robot for Steel Bridge Inspection. J Intell Robot Syst 2021, 102, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.; Afsari, K. Robots in Inspection and Monitoring of Buildings and Infrastructure: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ueda, T. A review study on unmanned aerial vehicle and mobile robot technologies on damage inspection of reinforced concrete structures. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 536–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Bai, Y.S.; Wu, D.H.; Yu, Y.X.; Ma, X.F.; Lin, C. Key structure and technology of bridge cable maintenance robot – a review. Robot. Intell. Autom. 2024, 45, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östlund, B.; Malvezzi, M.; Frennert, S.; Funk, M.; Gonzalez-Vargas, J.; Baur, K.; Alimisis, D.; Thorsteinsson, F.; Alonso-Cepeda, A.; Fau, G.; et al. Interactive robots for health in Europe: Technology readiness and adoption potential. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11, 979225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, R. Readiness of a Developing Nation in Implementing Automation and Robotics Technologies in Construction: A Case Study of Malaysia. J. Civ. Eng. Arch. 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, C.; Khurana, V.; Harrison, F.; Jacobs, L. Robotics and law: Key legal and regulatory implications of the robotics age (Part I of II). Computer Law & Security Review 2016, 32, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaronga, E.F.; Golia, A.J. Robots, standards and the law: Rivalries between private standards and public policymaking for robot governance. Computer Law & Security Review 2019, 35, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Rab, S.; Suman, R.; Kumar, L. Utilization of Robotics for Healthcare: A Scoping Review. J. Ind. Integr. Manag. 2022, 10, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajczyk, T.; Mikołajewski, D.; Kłodowski, A.; Łukaszewicz, A.; Mikołajewska, E.; Paczkowski, T.; Macko, M.; Skornia, M. Energy Sources of Mobile Robot Power Systems: A Systematic Review and Comparison of Efficiency. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajczyk, T.; Mikołajewski, D.; Kłodowski, A.; Łukaszewicz, A.; Mikołajewska, E.; Paczkowski, T.; Macko, M.; Skornia, M. , Materials for Batteries of Mobile Robot Power Systems: A Systematic Review and Comparison of Efficiency, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning in advanced robotics, a review. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakolu, S.; Faheem, M.A. , Autonomous Robotics in Field Operations: A Data-Driven Approach to Optimize Performance and Safety, Iconic Research And Engineering Journals 7 (2024).

- Campbell, D.H.; McDonald, D.; Araghi, K.; Araghi, T.; Chutkan, N.; Araghi, A. The Clinical Impact of Image Guidance and Robotics in Spinal Surgery: A Review of Safety, Accuracy, Efficiency, and Complication Reduction. Int. J. Spine Surg. 2021, 15, S10–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamisetty, A. AI-Driven Robotics in Solar and Wind Energy Maintenance: A Path toward Sustainability. Asia Pac. J. Energy Environ. 2022, 9, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharo, A.; Gowid, S.; Al Sageer, M.; Mohamed, A.; Naji, K.K. , AI-based framework for Construction 4.0, in: Artificial Intelligence Applications for Sustainable Construction, Elsevier, 2024: pp. 193–223. [CrossRef]

- Al Masri, A.; da Costa, B.B.F.; Vasco, D.; Boer, D.; Haddad, A.N.; Najjar, M.K. Roles of robotics in architectural and engineering construction industries: review and future trends. Jounarl Build. Des. Environ. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khahro, S.H.; Khahro, Q.H. , Use of Artificial Intelligence in Occupational Health and Safety in Construction Industry: A Proposed Framework for Saudi Arabia, in: 2024: pp. 49–59. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).