Submitted:

08 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

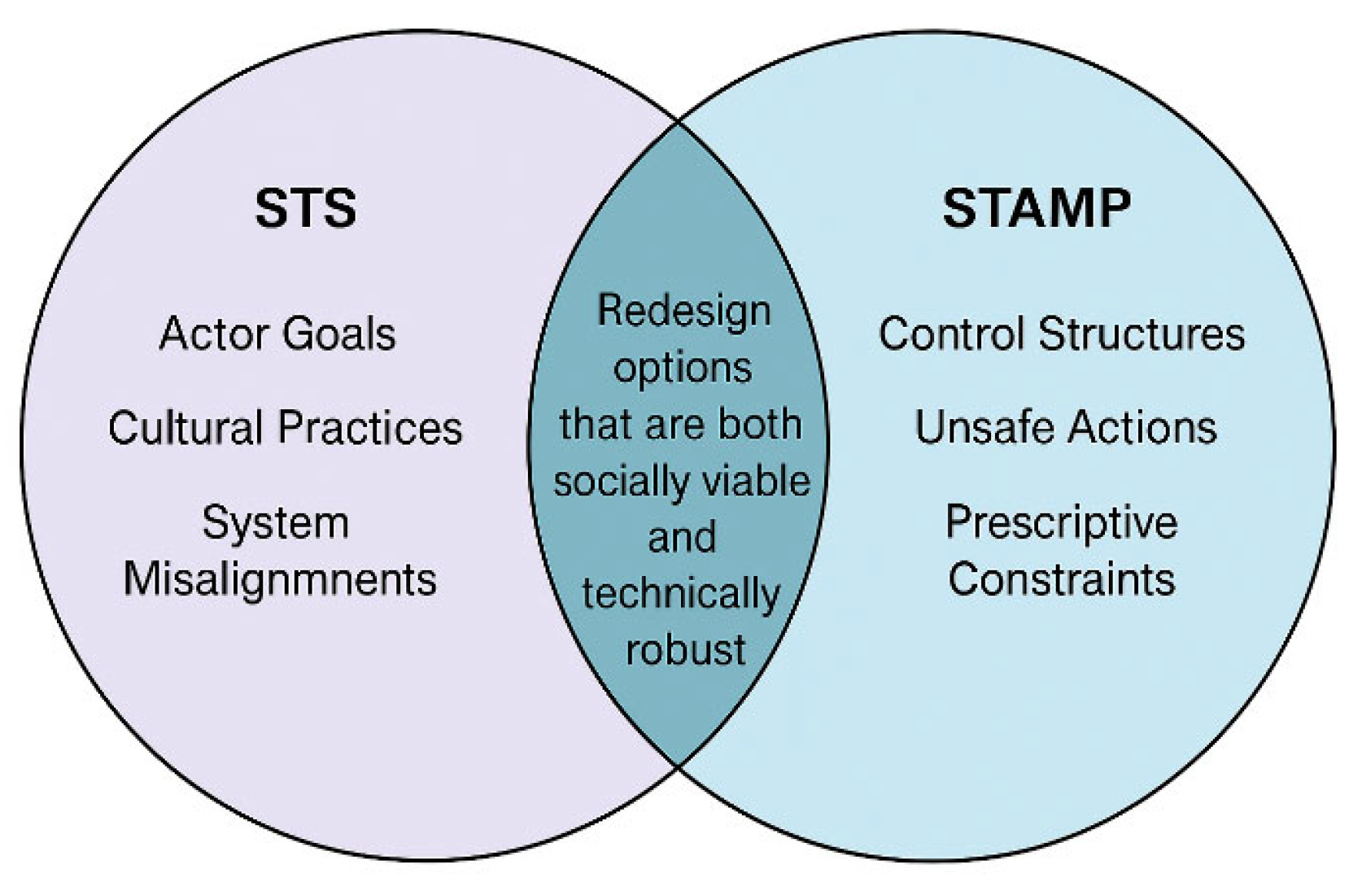

1.1. Conceptual Foundations: Sociotechnical Systems and STAMP

1.1.1. Sociotechnical Systems (STS)

- Human (e.g., roles, behaviors, competencies)

- Intentional (e.g., goals and motives)

- Technological (e.g., digital tools, interfaces)

- Procedural (e.g., formal processes, rules)

- Cultural (e.g., norms, shared beliefs)

- Infrastructural (e.g., physical constraints like road layouts).

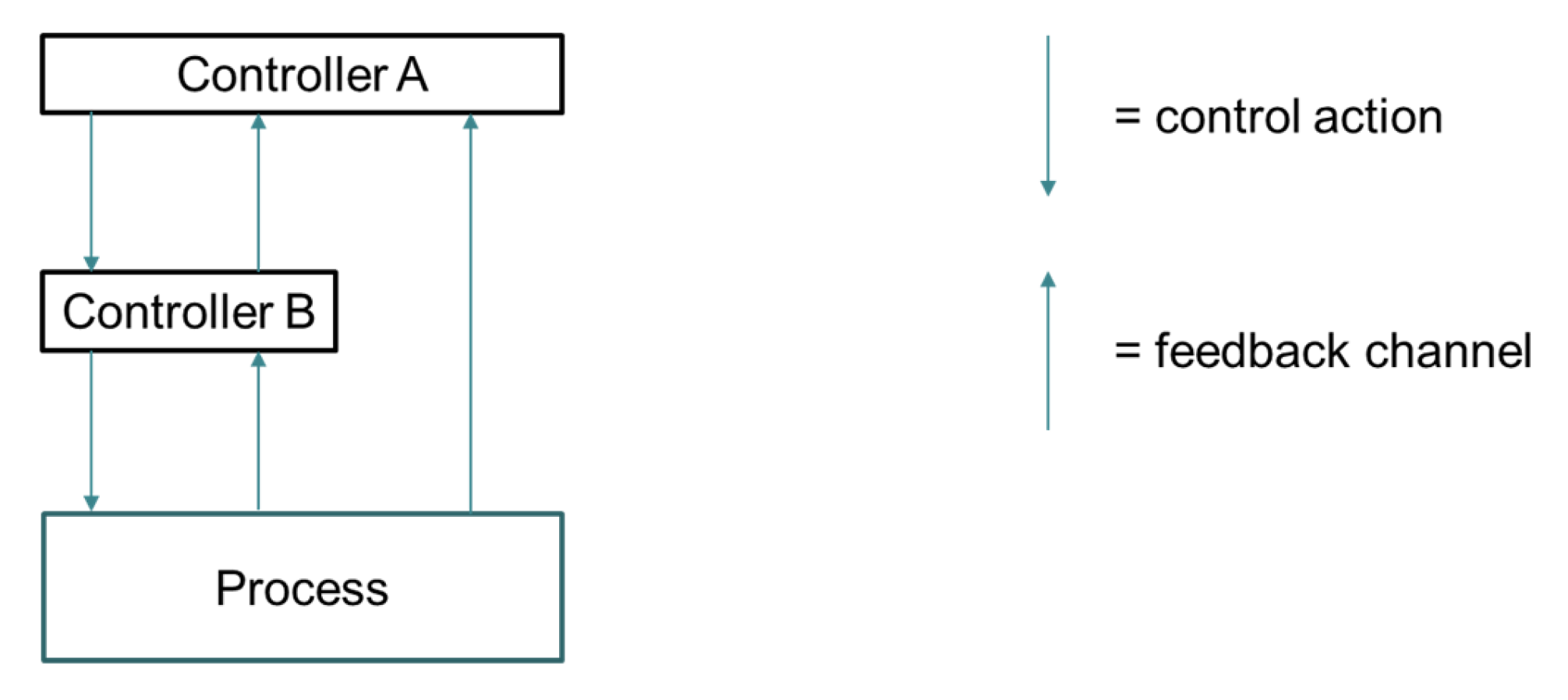

1.1.2. System-Theoretic Accident Model and Processes (STAMP)

1.2. Combining STS and STAMP for a Complementary Systems Analysis

1.3. Aim

2. Methods

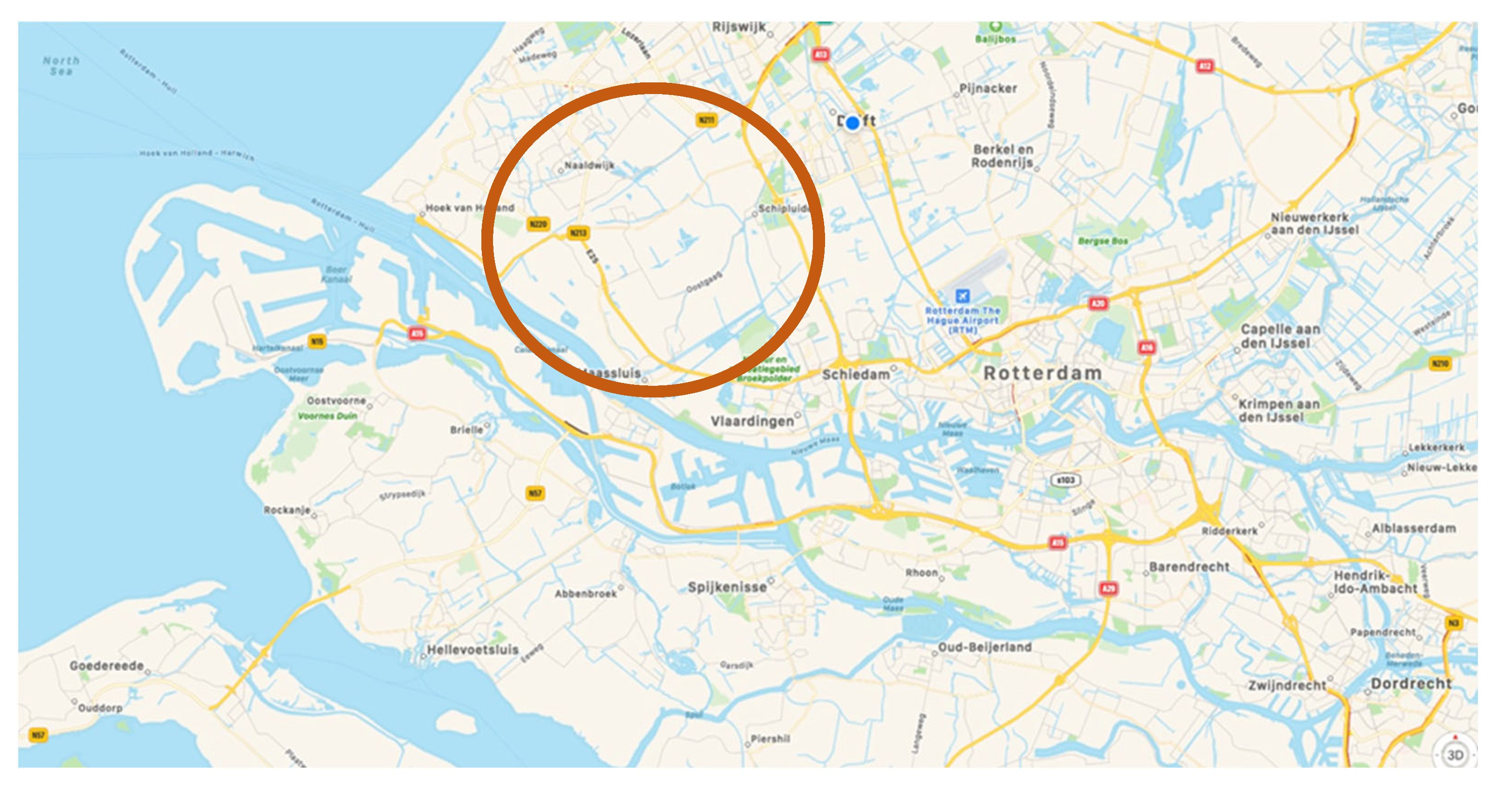

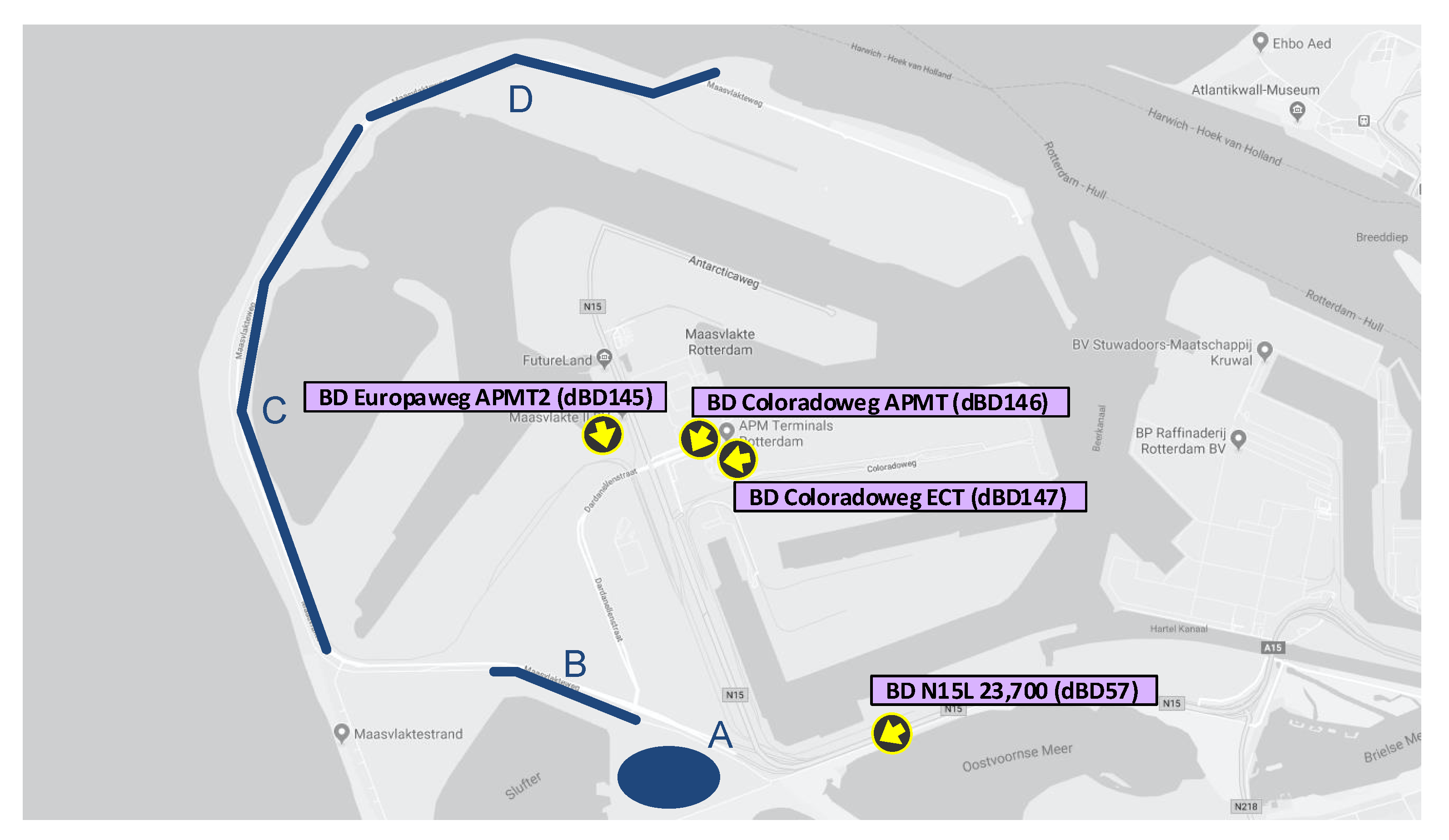

2.1. Case Study: Truck rerouting in the Port of Rotterdam

- the allocation of truck traffic to specific buffer areas;

- activation of tailored messages on Variable Message Signs (VMS) along approach roads; and

- coordinated responsibilities for personnel in operational roles to facilitate the diversion process.

2.2. Document Review

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis with STS and STPA

2.3.1. STPA Analysis

2.3.2. STS Analysis

3. Results

3.1. STS Analysis

3.1.1. Misalignment Between Procedures and Actor Intentions

3.1.2. Misalignment Between Procedures and Infrastructure

3.1.3. Misalignment Between Procedures, Culture, and Technology

3.2. STPA Analysis

3.2.1. Losses, Hazards and System-Level Constraints

- L1 – Delays to ship departures

- L2 – Road safety risks (collisions or near misses)

- L3 – Damage to the port authority’s reputation for fairness

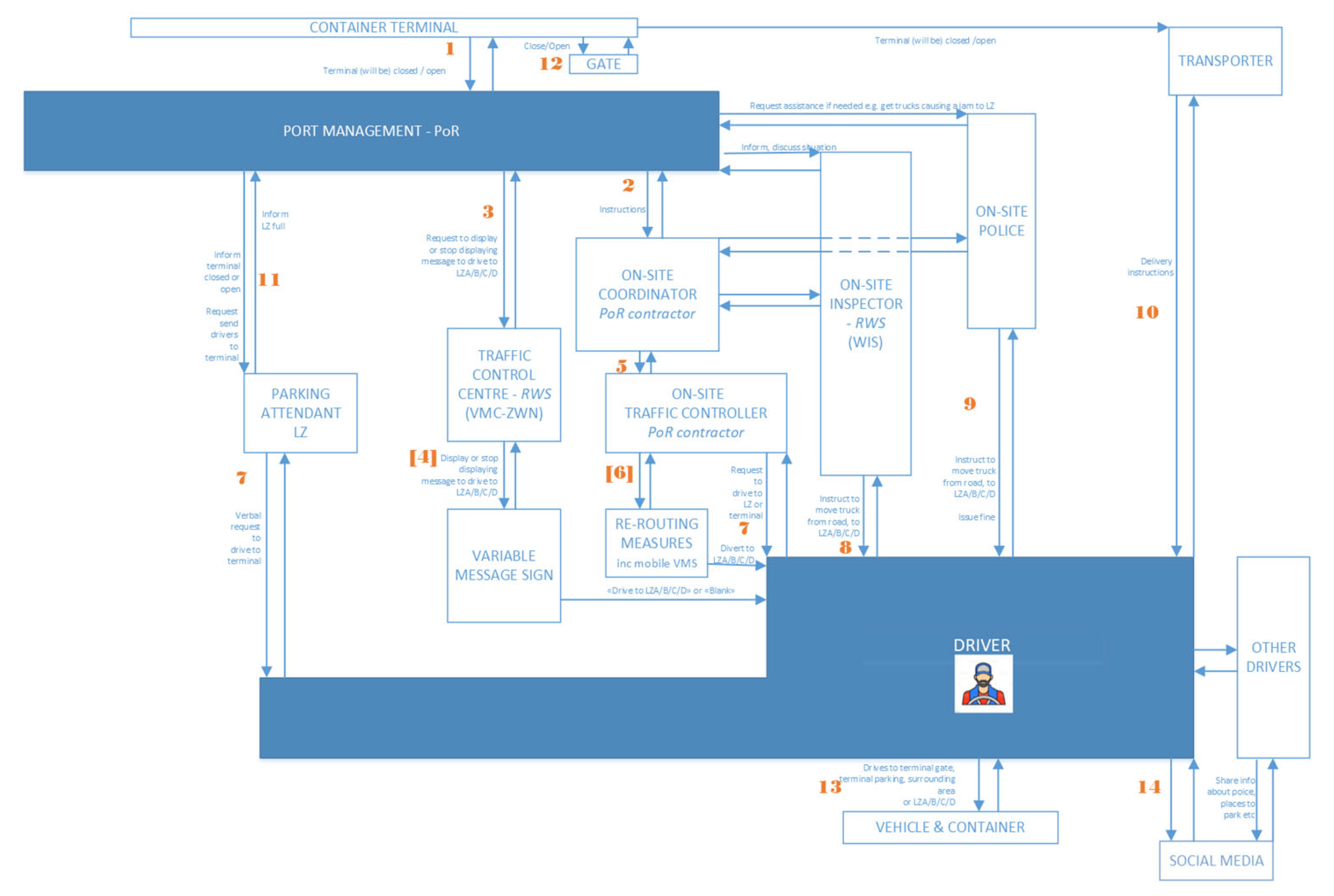

3.2.2. Control Structure and Unsafe Control Actions

3.2.3. Loss Scenarios and Design Recommendations

- Unsafe controller actions (51.6%)

- Inadequate feedback/information (26.3%)

- Faulty control paths (14.2%)

- Failures in the process being controlled (7.9%)

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of STPA Recommendations and STS Results

4.2. Implications for Sociotechnical Design

4.3. Study Limitations

4.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Loss, Hazards and System Constraints

- Loss

- Port management representatives identified three types of loss (L) that it was important for the system to avoid:

- L-1

- Delay to ship departure

- L-2

- Material or personal injury due to road traffic collision

- L-3

- Port authority get a reputation for unfair practice

- Hazards

- Hazards are system states that increase the risk of losses occurring. The following hazards (H) and subhazards (SH) were identified for the system under study:

- H-1

-

Truck queue outside one container terminal reduces access to another [can lead to L-1, L-2, L-3]

- SH-1.1

- Trucks approach closed terminal instead of buffer area [can lead to H-1]

- SH-1.2

- Too many trucks arrive at open terminal just before it is closed [H-1]

- SH-1.3

- Too high rate of trucks arriving at terminal after it is re-open [H-1]

- H-2

- Trucks parked on main roads or side roads surrounding a container terminal [L-1, L-2, L-3]

- H-3

- Trucks turning around in a road leading to a closed container terminal [L-1, L-2]

- H-4

-

It is not evident to truck drivers in buffer area that all trucks will enter re-opened terminal in order of arrival at port [L-3]

- SH-4.1

- Drivers/firms do not see that all trucks will enter re-opened terminal in order of arrival at port [L-3]

- SH-4.2

- Drivers in buffer area do not see that trucks not using buffer area cannot enter terminal before them [L-3]

- SH-4.3

- Drivers in buffer area do not see that trucks arriving at port just after terminal re-opening will not enter terminal before them [L-3]

- H-5

- Trucks in buffer area do not start to approach terminal once it is re-opened [L-1]

- System constraints

- We considered constraints that need to be upheld by the system in order to prevent loss. Systems constraints are derived from hazards and sub-hazards:

- SC-0

- < X trucks queue on road outside a container terminal [H-1]

- SC-1

- Drivers do not drive to a closed terminal instead of a buffer area [SH-1.1]

- SC-2

- < Y trucks head towards a terminal less than Z minutes before it closes [SH-1.2]

- SC-3

- Rate of trucks [no. of trucks/min] heading towards a re-open terminal limited [SH-1.3]

- SC-4

- Trucks do not park on roads near terminal that is closed, about to close or re-open [H-2]

- SC-5

- Trucks do not enter road leading to a terminal that is closed or about to close [H-3]

- SC-7

- Evident to drivers/firms that trucks enter re-opened terminal in order of arrival at buffer area [SH-4.1]

- SC-8

- Evident to drivers that trucks not buffering do not enter the terminal before trucks that have diverted [SH-4.2}

- SC-9

- Evident to drivers that trucks arriving at port do not enter re-open terminal before trucks coming from buffer area [SH-4.3]

- SC-10

- Trucks progress to correct terminal once it is re-opened [H-5]

Appendix B. Unsafe Control Actions (UCA) with Corresponding Safety Constraints (SC)

| Unsafe Control Actions Identified (UCA) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control action (cf Fig. 3) | Not providing action causes hazard | Providing action causes hazard | Too early, late, out of order |

| 1 Container Terminal to PoR: terminal will close | UCA-1: Container Terminal does not tell PoR that it will close (SC-0,1,2,5,7,8,9) | UCA-2: Container Terminal tells PoR that it will close when it will not (SC-10) | UCA-3: Container Terminal gives PoR insufficient warning that it will close (SC-0,1,2,5) |

| 1 Container Terminal to PoR: terminal will open | UCA-4: Container Terminal does not tell PoR that it will open (SC-10) | UCA-5: Container Terminal tells PoR that it will open when it will not (SC-0,1,2,5) | UCA-6: Container Terminal gives PoR insufficient warning that it will open (SC-10) |

| 2 PoR to On-site Coordinator: instructions on terminal closure | UCA-15: PoR does not give on-site Coordinator instructions to divert from terminal when it closes (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA-16: PoR gives on-site Coordinator instructions to divert drivers from terminal when it will remain open (SC-10) | UCA-17: PoR gives on-site Coordinator instructions too late to divert drivers from terminal (SC-0,1,2,4,5) |

| UCA-19: PoR gives on-site Coordinator inadequate instructions on how to divert drivers from terminal when it closes (SC-0,1,2,4,5,7,8,9,10) | |||

| 2 PoR to On-site Coordinator: instructions on terminal opening | UCA-20: PoR does not give on-site Coordinator instructions to tell drivers to start going to terminal when it re-opens (SC-10) | UCA-21: PoR gives on-site Coordinator instructions to tell drivers to start going to terminal when it will stay closed (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA-22: PoR gives on-site Coordinator instructions too late to tell drivers to start going to terminal when it will re-open (SC-8,9,10) |

| UCA-23: PoR gives on-site Coordinator inadequate instructions on to tell drivers to start going to terminal when it will re-open (SC-0,3,7,8,9,10) | |||

| 3 PoR to Traffic Control Centre: Display “Divert to LZ” | UCA-24: PoR does not instruct Control Centre to display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA-25: PoR instructs Control Centre to display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will not close (SC-10) | UCA-26: PoR instructs Control Centre too late to display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) |

| UCA-27: PoR does not instruct Control Centre to display “Divert to LZB” when LZA full (SC-1,4) | UCA-28: PoR instructs Control Centre to divert to wrong LZ (SC-7,8,9) | UCA-29: PoR instructs Control Centre too early to display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will close (SC-10) | |

| UCA-30: PoR does not instruct Control Centre to stop display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will open (SC-10) | UCA-31: PoR tells Controll Centre to stop display “Divert to LZ” when terminal still closed (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA-32: PoR instructs Control Centre too late to display “Divert to LZB” as LZA full (SC-1,4) | |

| UCA-33: PoR instructs Control Centre too late to stop display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will open (SC-10) | |||

| 4 Traffic Control Centre to VMS: Display “Divert to LZ | UCA-34: Traffic Control Centre does not program VMS to display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA-35: Traffic Control Centre instructs VMS to display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will not close (SC-10) | UCA-36: Traffic Control Centre instructs VMS too late to display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) |

| UCA-37: Traffic Control Centre does not program VMS to display “Divert to LZB” when LZA full (SC-1,4) | UCA-38: Traffic Control Centre instructs VMS to display divert to wrong LZ (SC-7,8,9) | UCA-39: Traffic Control Centre instructs VMS too late to display “Divert to LZB” as LZA full (SC-1,4) | |

| UCA-40: Traffic Control Centre does not program VMS to stop display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will open (SC-10) | UCA-41: Traffic Control Centre programs VMS to stop display “Divert to LZ” when terminal still closed (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA-42: Traffic Control Centre programs VMS too late to stop display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will open (SC-10) | |

| UCA-43: Traffic Control Centre programs VMS too early to stop display “Divert to LZ” when terminal will re-open (SC-3) | |||

| 5 On-site Coordinator to on-site Traffic Controller: Divert traffic to LZ | UCA-44: On-site Coordinator does not instruct Traffic Controllers to divert trucks to LZ when terminal will close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA-45: On-site Coordinator instructs Traffic Controllers to divert trucks to LZ when terminal will stay open (SC-10) | UCA-46: On-site Coordinator instructs Traffic Controllers too late to divert traffic to LZ when terminal will close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) |

| UCA-47: On-site Coordinator instructs Traffic Controllers to divert trucks to wrong LZ when terminal will close (SC-7,8,9) | UCA-48: On-site Coordinator instructs Traffic Controllers too early to divert traffic to LZ when terminal will close (SC-10) | ||

| UCA-49: On-site Coordinator instructs Traffic Controllers to divert trucks headed for different terminal to LZ when terminal will close (SC-10) | |||

| 5 On-site Coordinator to on-site Traffic Controllers: Stop divert traffic to LZ | UCA-50: On-site Coordinator does not instruct Traffic Controllers to stop diverting trucks to LZ when terminal will re-open (SC-10) | UCA-51: On-site Coordinator instructs Traffic Controllers to stop divert trucks to LZ when terminal will remain closed (SC-0,1,2,4,5,7,8,9) | UCA-52: On-site Coordinator instructs Traffic Controllers too late to stop divert trucks to LZ when terminal will re-open (SC-10) |

| 6 On-site Traffic Controllers set out re-routing measures | UCA-53: On-site Traffic Controllers do not set out re-routing measures when terminal will close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA-54: On-site Traffic Controllers set out re-routing measures when terminal will not close (SC-10) | UCA-55: On-site Traffic Controllers set out re-routing measures too late when terminal will close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) |

| UCA-56: On-site Traffic Controllers set out wrong re-routing measures when terminal will close (SC-4, 10) | UCA-57: On-site Traffic Controllers set out re-routing measures too early when terminal will close (SC-10) | ||

| 6 On-site Traffic Controllers remove re-routing measures | UCA-58: On-site Traffic Controllers do not remove re-routing measures when terminal open (SC-10) | UCA-59: On-site Traffic Controllers remove re-routing measures when terminal still closed (SC-0,1,4,5,7,8,9) | UCA-60: On-site Traffic Controllers remove re-routing measures too late when terminal re-open (SC-8,9,10) |

| 7 On-site Traffic Controllers or Parking Attendant to Driver: Drive to terminal | UCA-61: On-site Traffic Controllers or Parking Attendant do not tell x number of first-to-arrive drivers to drive to terminal when re-open (SC-3,7,10) | UCA-62: On-site Traffic Controllers or Parking Attendant tell Driver to drive to terminal when terminal will remain closed (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA-63: On-site Traffic Controllers or Parking Attendant tell Drivers to drive to terminal in fair order too late after terminal open (SC-8,9,10) |

| UCA-64: On-site Traffic Controllers or Parking Attendant tell Driver to drive to terminal in unfair/random order when terminal will open (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA-65: On-site Traffic Controllers or Parking Attendant tell Drivers to drive to terminal too early before terminal open (SC-0,1,3,4,5) | ||

| 8 On-site Inspector to Driver: move truck from road to LZ | UCA-66: On-site Inspector does not tell Driver: move truck from road to LZ (SC-0,4,7,8) | UCA-67: On-site Inspector tells Driver: move truck from road to wrong LZ (SC-7,9,10) | UCA-68: On-site Inspector tells Driver too late: move truck from road to LZ (SC-0,4,7,8) |

| UCA-69: On-site Inspector tells Driver: move truck from road without designating LZ (SC-7,9) | |||

| 9 On-site Police to Driver: move truck from road to LZ | UCA-70: On-site Police does not tell Driver: move truck from road to LZ (SC-0,4,7,8) | UCA-71: On-site Police tells Driver: move truck from road to wrong LZ (SC-7,9) | |

| UCA-72: On-site Police tells Driver: move truck from road from road without designating LZ (SC-4,7) | |||

| 10 Transporter to Driver(s): Delivery instructions | UCA-73: Transporter informs driver to deliver to terminal as fast as possible (SC-1,2,3,4,5) | ||

| 11 PoR to Parking Attendant: send drivers to terminal | UCA-74: PoR does not ask Attendant to send driver to correct terminal once re-open (SC-9, 10) | UCA-75: PoR asks Attendant to send driver to terminal that will not open (SC-0,1,3,4,5) UCA-76: PoR asks Attendant to send driver to terminal in unfair order (SC-7) |

|

| 12 Terminal to gate: close | UCA-77: Terminal closes gate too early (SC-0,1,4,5) UCA-78: Terminal closes gate too late (SC-8) |

||

| 12 Terminal to gate: open | UCA-79: Terminal opens gate too early, allowing in trucks who have not waited at LZ (SC-7,8,9) UCA-80: Terminal opens gate too late when trucks are on way from LZ (SC-0,1,4,5) |

||

| 13 Driver: Drives to terminal | UCA:82: Driver does not drive to terminal that is open or about to re-open (SC-10) | UCA-81: Driver drives to terminal that is closed or about to close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA83: Driver arrives too late at terminal about to close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) |

| UCA-84: Driver drives to wrong terminal (SC-1,4,5) | |||

| 13 Driver: Drives to LZ | UCA-85: Driver routed to LZ on way into port does not drive to designated LZ (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | UCA-86: Driver drives to full LZ | UCA-88: Driver drives to LZ too early – terminal yet to shut (SC-10) |

| 14 Driver: Enters info on social media | UCA-89: Driver tells other drivers to drive to closed terminal (SC-0,1) | UCA-91: Driver tells other drivers too late that terminal about to close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | |

| UCA-90: Driver tells other drivers terminal about to close (SC-0,1,2,4,5) | |||

| UCA-92: Driver tells other drivers terminal has re-opened (SC-3, 7, 8, 9) | |||

| 1 | Note that although the terms “hazard” and “unsafe” as used in STAMP can be misleading as they do not necessarily relate to safety per se. Hazards are system states that can lead to loss of any desirable system outcome – not just safety, but efficiency, punctuality, security, equal treatment and so on. Likewise, “unsafe” can mean |

References

- Hall, S. Traffic Planning in Port Cities - Discussion Paper; ITF/OECD; ITF Roundtable 169; Simon Fraser University: Buenos Aires, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- JICA, 2018. Overcoming Congestion Issues, Presentation by Japan International Cooperation Agency, accessed online 5th June 2024 https://www.jica.go.jp/.

- Osadume, R. , Okene, A., Uzoma, B. & Enaruna, D. An Evaluation of the delay factors in Nigeria’s seaports: A study of the Apapa port complex. Journal of Transportation and Logistics 2023, 8, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyoob, M. Z.; van Niekerk, B. CAUDUS: An optimisation model to reducing port traffic congestion. In 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, Computing and Data Communication Systems (icABCD); 2021; pp 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. , Li, C. & Gai, W. (2024). How does evacuation risk change over time? Influences on evacuation strategies during accidental toxic gas releases. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2024, 108, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. , Dong, G. and Gui, Y. Data-driven emergency evacuation decision for cruise ports under Covid-19: an improved genetic algorithm and simulation. Physica A: Statistical mechanics and its applications. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Y. K. H.; Lee, M. Y. N. Simulation study of port container terminal quay side traffic. In AsiaSim 2007. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol. 5. Springer, Berlin.; 2007.

- Vis, I. F. A.; de Koster, R. (M. ) B. M.; Savelsbergh, M. W. P. Minimum vehicle fleet size under time-window constraints at a container terminal. Transportation Science 2005, 39, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, A.-K.; Schwientek, A.; Jahn, C. Reducing truck congestion at ports – Classification and trends. In: Jahn, Carlos Kersten, Wolfgang Ringle, Christian M. (Ed.): Digitalization in Maritime and Sustainable Logistics: City Logistics, Port Logistics and Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Digital Age. Proceedings of the Hamburg International Conference of Logistics (HICL); Vol 24; Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH), Institute of Business Logistics and General Management: Hamburg, Germany, 2017; pp 37–58.

- Estrada, W. More holistic approach needed to address backlog at our ports. Published online at CalMatters , November 18, 2021. Accessed online 2nd June 2024. https://calmatters.org/commentary/2021/11/more-holistic-approach-needed-to-address-backlog-at-our-ports/.

- Martin, J.; Thomas, B. J. The container terminal community. Maritime Policy & Management 2010, 28, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meersman, H.; Van de Voorde, E.; Vanelslander, T. Port congestion and implications to maritime logistics. In: Song, D.-W., Panayides, P. M., Eds. Maritime Logistics; Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2012; 49–68. [CrossRef]

- Trist, E. L.; Bamforth, K. W. Some social and psychological consequences of the longwall method of coal-getting: An examination of the psychological situation and defences of a work group in relation to the social structure and technological content of the work system. Human Relations 1951, 4, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.; Baskerville, R. Revising the socio-technical perspective for the 21st century: New mechanisms at work. Journal of database management 2020, 31, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.O.; Berg, S.-H. Sociotechnical factors supporting mobile phone use by bus drivers. IISE Transactions on Occupational Ergonomics and Human Factors, 2023, 11(1-2):1-13.

- Clegg, C. Sociotechnical principles for system design. Applied Ergonomics 2000, 31, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, H. P. N.; Clegg, C. W.; Bolton, L. E.; Machon, L. C. Systems scenarios: A tool for facilitating the socio-technical design of work systems. Ergonomics 2017, 60, 1319–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, G., J. M.; Beanland, V.; Lenné, M., G.; Stanton, N. A.; Salmon, P. M. Integrating Human Factors Methods and Systems Thinking for Transport Analysis and Design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Challenger, R.; Clegg, C. W. Crowd disasters: A socio-technical systems perspective. Contemporary Social Science 2011, 6, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. C.; Challenger, R.; Dharshana, N. W. J.; Clegg, C. Advancing sociotechnical systems thinking: A call for bravery. Applied Ergonomics 2014, 45, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leveson, N. A New accident model for engineering safer systems. Safety Science 2004, 42, 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N.; Thomas, J. STPA Handbook; 2018.

- Phillips, R. O.; Rutten, B.; Rezvani, S. Sociotechnical Systems Analysis of Extreme Events and Implications for Infrastructure Management Systems (D4.2). EU H2020 Project “Safeway” Deliverable 4.2; European Commision, 2021.

| STS dimension | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Intentional | Procedural | |

| Actor | Goal | Does re- routing as intended align? | Does re-routing in practice align? |

| Port management | -Clear roads for terminal access | Yes | No |

| -Effective terminal (re-)entry | No | No | |

| -Fair treatment of different transporters and drivers | No | No | |

| -Road safety | Yes | No | |

| Container terminal management | -Minimise ship delay | Yes | No |

| -Process containers effectively | Yes | No | |

| Truck driver | -Rest, fuel, refresh | Yes | Yes |

| -Drop-off container and progress further | No | No | |

| -Deliver punctually to satisfy transport company management | No | No | |

| -Road safety | Yes | No | |

| # | Design recommendation | Explanation | # loss scenarios avoided |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Key actors see container terminal status and plans | Ensure all key actors (PoR, coordinators, traffic controllers, parking attendants, transporters, and drivers) see including both current and upcoming open/closed status. | 77 |

| 2 | Fair-order process | Develop and implement a process—co-designed with drivers and traffic personnel—to ensure trucks in buffer zones enter reopened terminals in the order of arrival, maintaining fairness and compliance. | 62 |

| 3 | Coordinator aware of Traffic Controller actions |

Ensure coordinators have real-time insight into traffic controllers' availability, actions taken, interpretation of instructions, and ongoing plans | 53 |

| 4 | PoR aware of Coordinator readiness | Provide Port of Rotterdam with visibility into coordinators’ preparedness, resource needs, and time requirements to manage truck diversions effectively. | 52 |

| 5 | Container Terminal aware of PoR readiness |

Ensure container terminals are informed of PoR’s operational readiness, diversion timelines, and current traffic management priorities when planning closures or reopenings. | 45 |

| 6 | PoR aware of Traffic Control Centre operations |

Give PoR insight into the Traffic Control Centre’s readiness, actions, and interpretation of terminal status changes, especially related to VMS updates. | 30 |

| 7 | Redirect drivers violating fair-order | Equip PoR and inspectors with tools to identify, locate, and redirect drivers queuing improperly on roads instead of at designated buffer areas. | 29 |

| 8 | Route incoming drivers via LZ |

Inform drivers clearly and in real time about terminal status, legal access timing, designated LZs, routes, queue lengths, and available facilities to ensure orderly routing. | 28 |

| 9 | PoR / Coordinator aware of LZ staff actions |

Enable PoR and coordinators to track how parking attendants and traffic controllers are interpreting and executing instructions, with direct situational awareness at LZs. | 22 |

| 10 | PoR see traffic around terminals | Provide PoR with real-time situational awareness of terminal-adjacent traffic to detect and address emerging queues, obstructions, or incidents. | 21 |

| 11 | LZ staff aware of driver needs and actions | Require parking attendants and traffic controllers to confirm drivers' understanding of re-routing messages and respond to their needs or misunderstandings. | 10 |

| 12 | Off-route warnings for drivers | Implement alerts for drivers straying from approved re-routing paths, with PoR oversight to monitor responses and intervene if needed. | 10 |

| 13 | Coordinate driver messages |

PoR/other actor or device must check and ensure consistency and coordination of messages drivers receive from VMS, re-routing measures and different actors, and as far as possible visualize these processes in real time. If possible, they should get insight into driver opinion about re-routing e.g. messaging on social media. | 8 |

| 14 | Re-route to different LZ | PoR (and Coordinator) needs sight on LZ and projections on capacity from sensors, or Parking Attendant / Traffic Controllers. | 8 |

| 15 | Coordinate traffic flow from LZ to terminal | To prevent queues forming outside terminal and ensure efficiency, PoR to coordinate flow of traffic from LZ to terminal with flow of entry to CT. | 5 |

| 16 | CT trigger to tell PoR about closure | CT needs internal trigger and check that PoR informed about sudden / planned closure. | 4 |

| Theme | STS findings | STPA design recommendations |

Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fairness | Procedure misaligned with truck driver and port manager goals (e.g. no guarantee of fair order entry) → drivers attempt to ‘game’ the system. | #2 Fair-order process #7 Redirect drivers threatening fair order #15 Coordinate traffic flow from LZ to terminal |

STPA offers concrete redesigns (fair-order process, enforcement) addressing misaligned goals flagged in STS. |

| Information asymmetry |

Lack of awareness and coordination across actors (drivers, terminals, PoR, traffic control) due to infrastructure, technology gaps. | #1 Real-time terminal status sharing #3–6, 9–10 Awareness of other actors’ plans, readiness, and actions #16 Trigger for PoR notification |

STPA directly targets the fragmented information flows identified in STS; it prescribes real-time feedback loops that the STS framework diagnosed as missing. |

| Layout of physical infrastructure | Existing infrastructure (road layouts, LZs) prevents enforcement of compliance or sequencing; LZs shared among trucks with different destinations. | #8 Route drivers via LZs, give info on capacity #14 Rerouting to different LZs #12 Off-route warnings |

STPA extends STS diagnosis by suggesting how to technically and procedurally improve driver routing and infrastructure awareness. |

| Culture and communication |

Drivers use decentralized, social media-based coordination; port managers use slower, hierarchical communication → asymmetry in adaptability. | #13 Coordinate driver messages; monitor messaging trends #11 Attendants check understanding with drivers |

STPA recommendations touch on this issue by promoting more coordinated and responsive messaging but fall short of fully integrating cultural practices identified in STS. |

| Resilience through coordination | Procedures don’t reflect emergent behavior or actor adaptation in real-world scenarios. | Most STPA recommendations (#1–16) focus on building feedback loops and visibility across actors. |

STPA offers a systemic control model, operationalizing the adaptability and coordination challenges flagged in STS. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).