Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

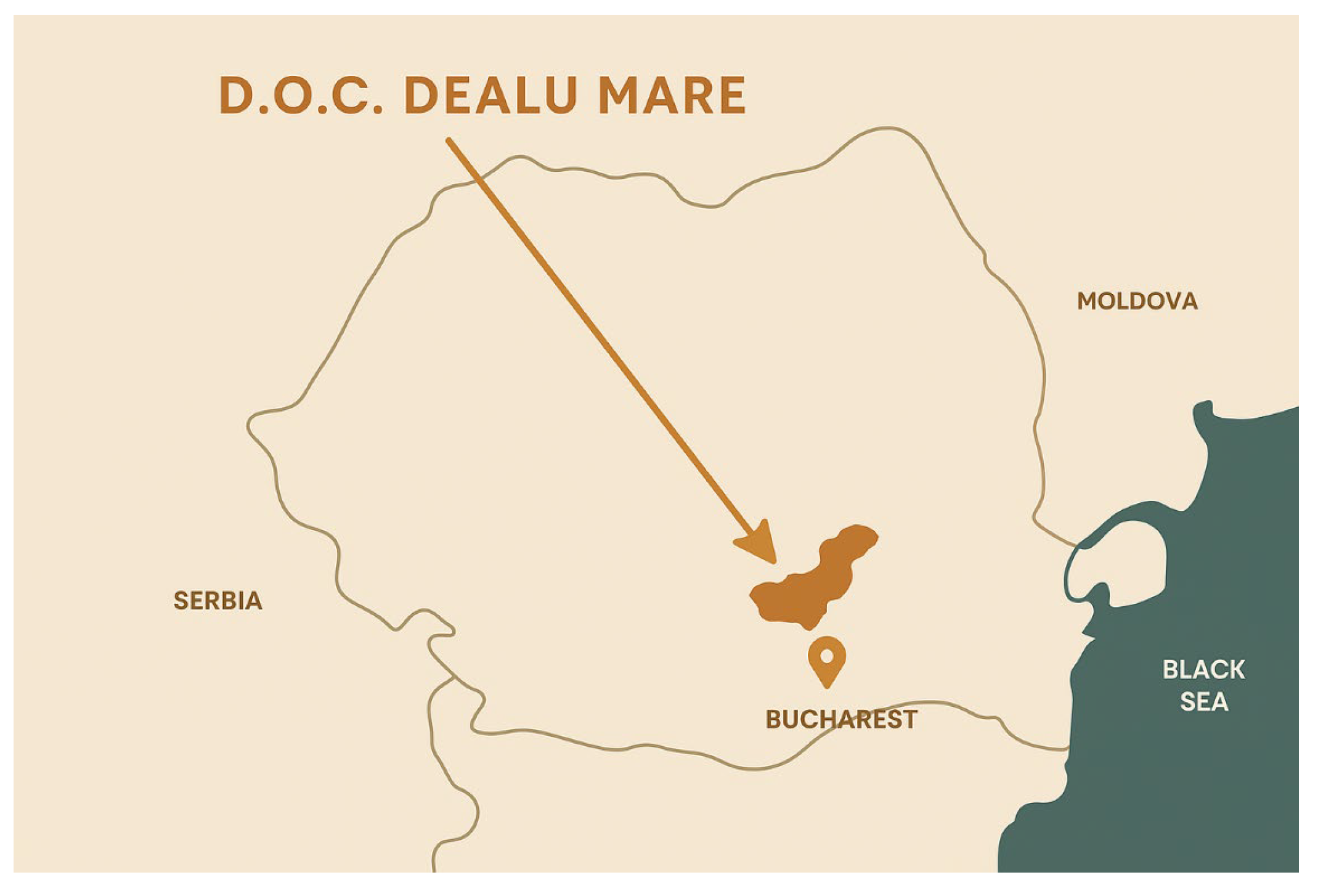

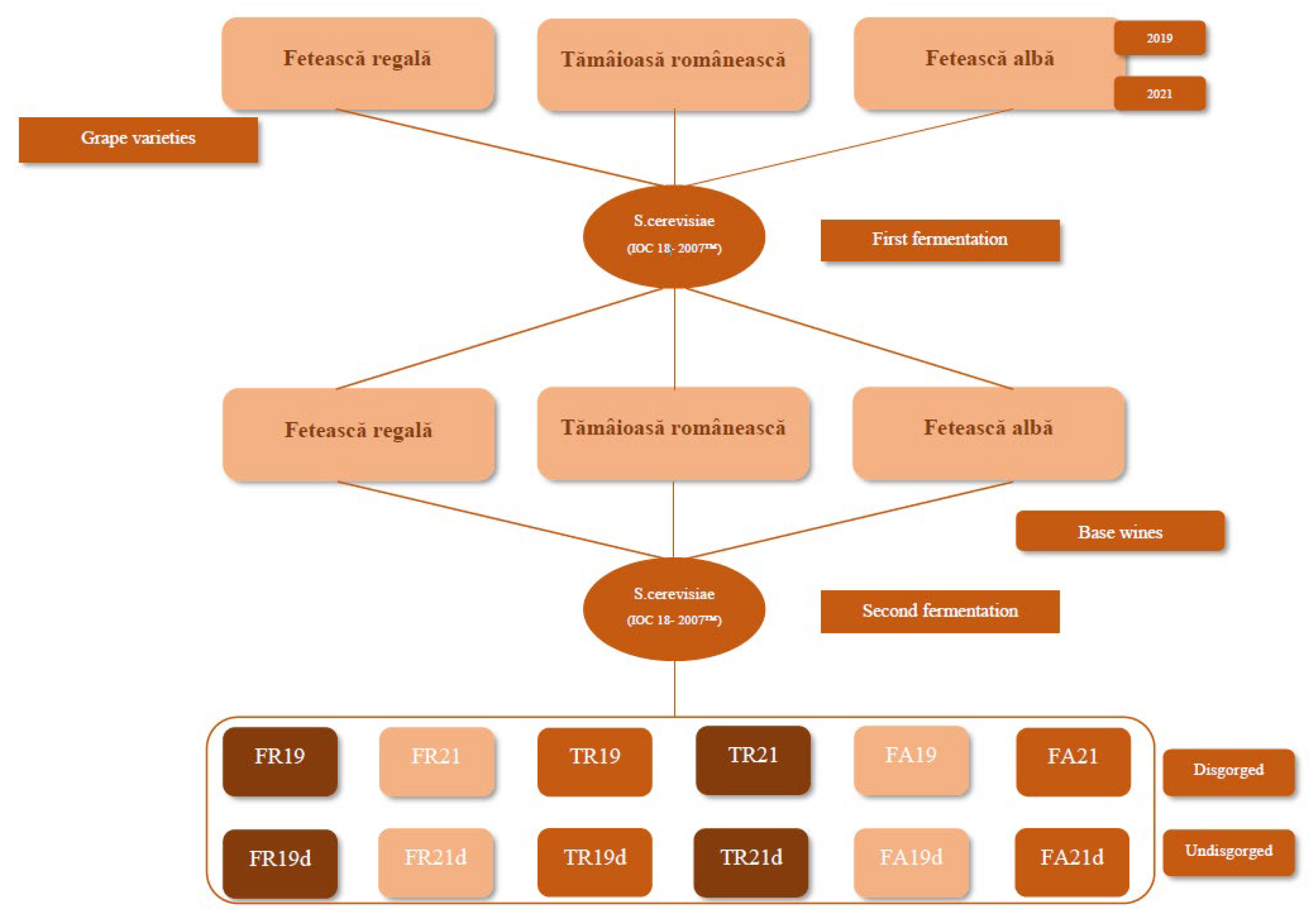

2.1. Wine Samples

2.2. Analytical Methodology

2.3. Sensory Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters

3.2. Color Chracterisation

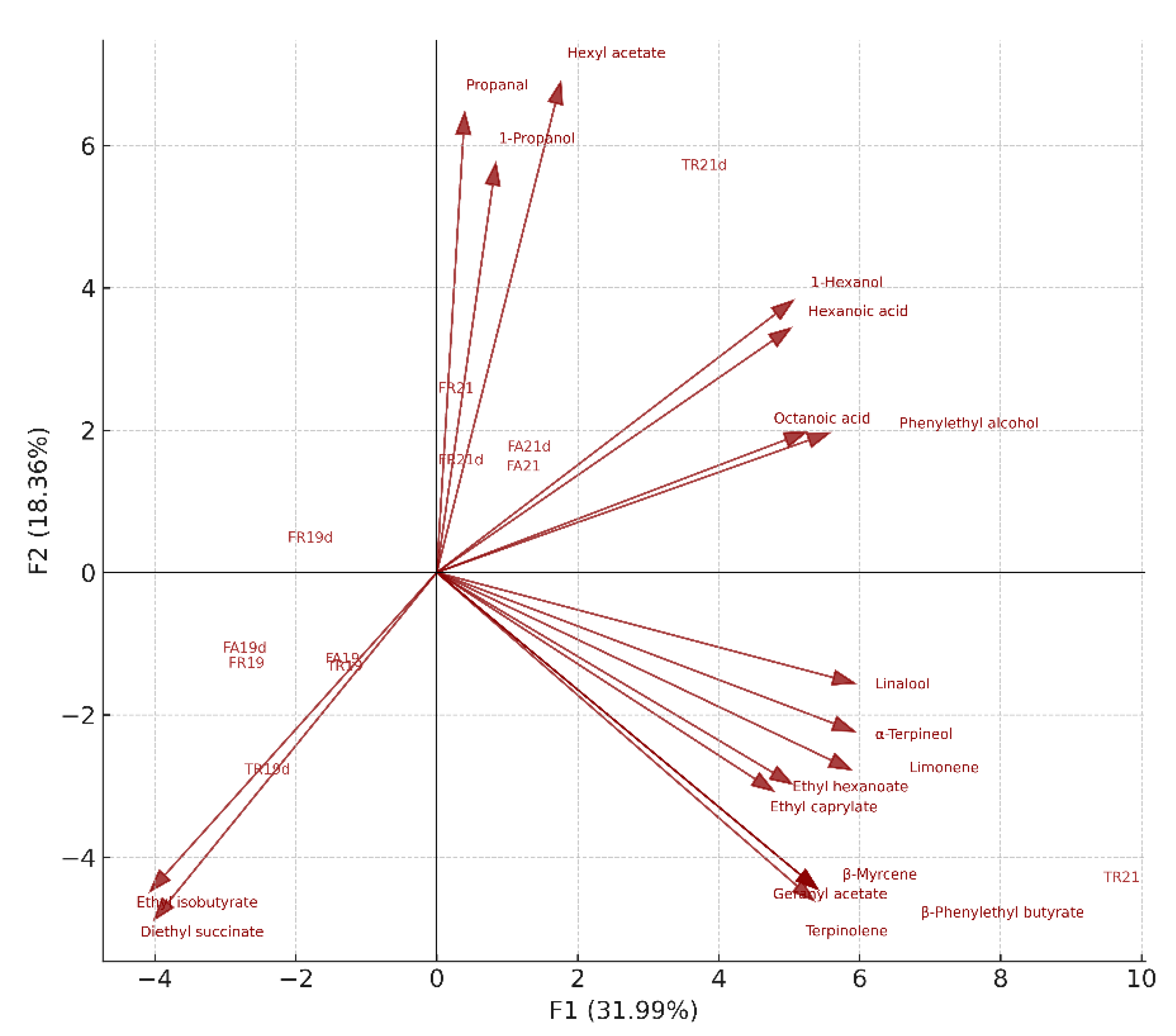

3.3. Volatile Compounds

3.3.1. Esters

3.3.2. Alcohols

3.3.3. Aldehydes

3.3.4. Acids

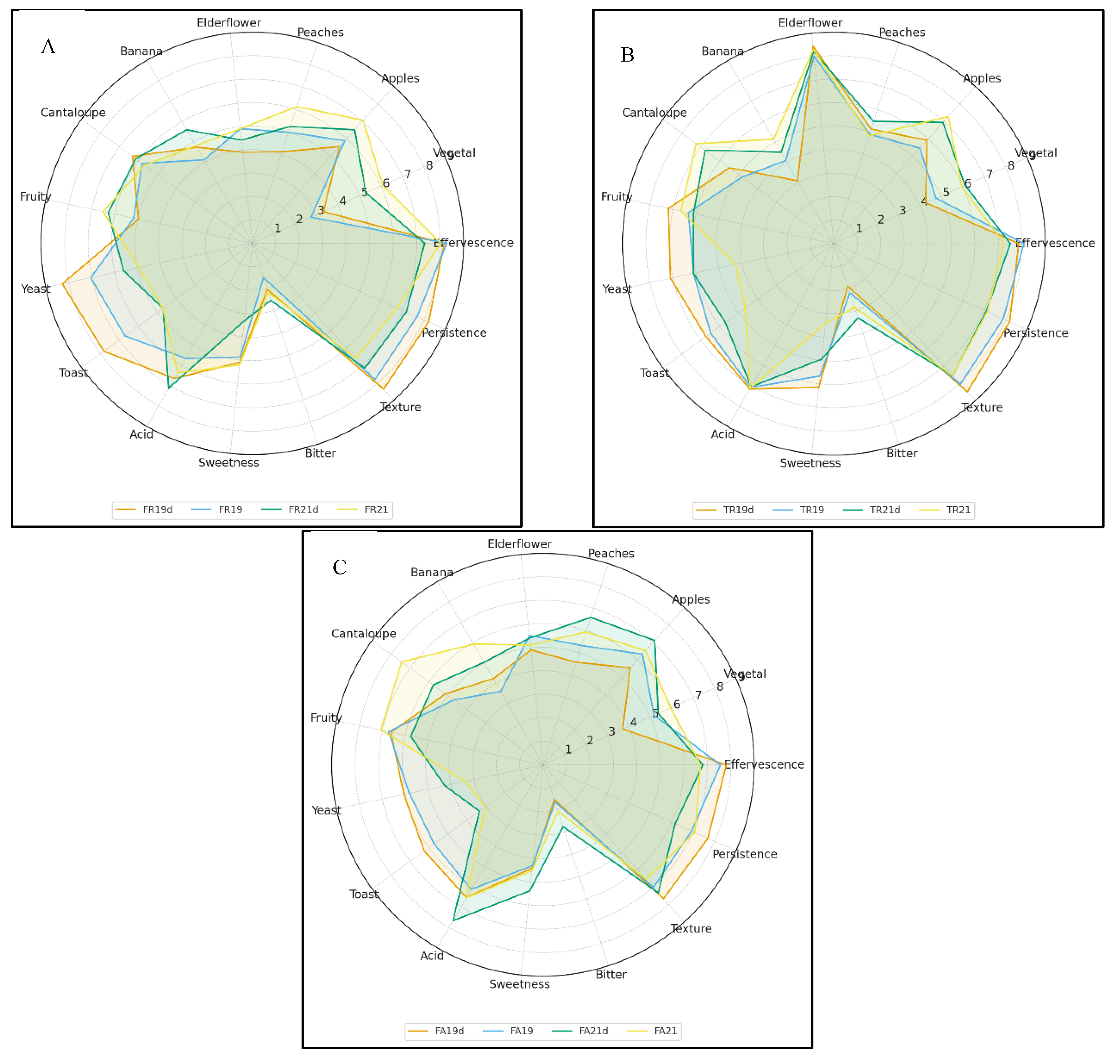

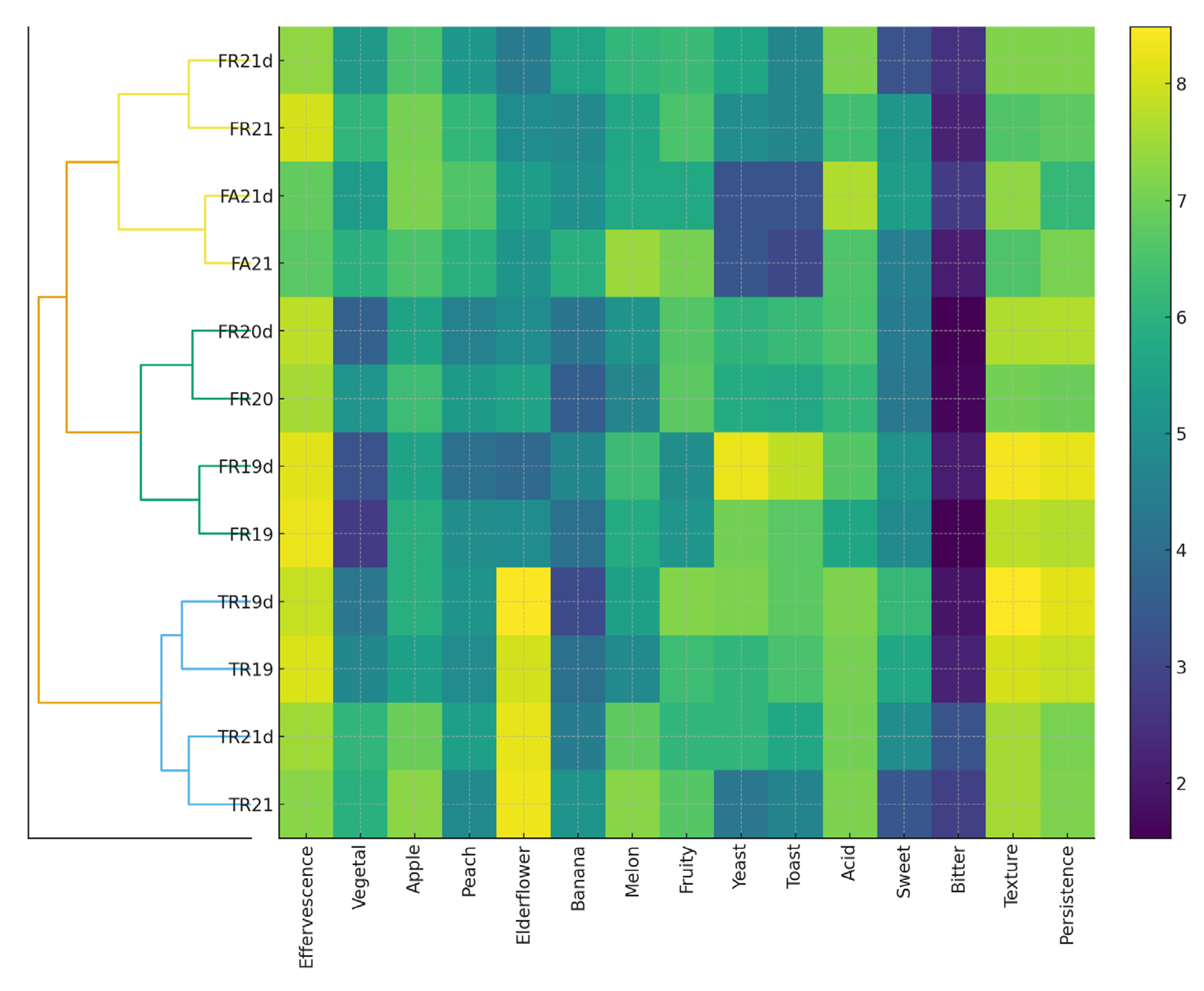

3.4. Sensorial Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FA | Fetească albă |

| FR | Fetească regală |

| TR | Tămâioasă românească |

| AF | Alcoholic fermentation |

| OIV | International Organization of Vine and Wine |

| SO2 | Sulfur dioxide |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| MTHFA | 5-methyl-tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol |

| MCFA | Medium-chain fatty acid |

References

- Luchian, C.E.; Grosaru, D.; Scutarașu, E.C.; Colibaba, L.C.; Scutarașu, A.; Cotea, V.V. Advancing Sparkling Wine in the 21st Century: From Traditional Methods to Modern Innovations and Market Trends. Fermentation 2025, 11. [CrossRef]

- Tudela, R.; Gallardo-Chacon, J.J.; Rius, N.; Lopez-Tamames, E.; Buxaderas, S. Ultrastructural changes of sparkling wine lees during long-term aging in real enological conditions. FEMS Yeast Res 2012, 12, 466-476. [CrossRef]

- Jové, P.; Mateu-Figueras, G.; Bustillos, J.; Martín-Fernández, J.A. Analysis of Aromatic Fraction of Sparkling Wine Manufactured by Second Fermentation and Aging in Bottles Using Different Types of Closures. Processes 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Buxaderas, S.; López-Tamames, E. Chapter 1—Sparkling Wines: Features and Trends from Tradition. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, Henry, J., Ed.; Academic Press: 2012; Volume 66, pp. 1-45.

- Mihaela Dana Pop, A. The Influence of Physical-Chemical Parameters on the Sensory Evaluation of Sparkling Wines. Annals of’Valahia’University of Târgovişte. Agriculture 2024, 16.

- Martínez-Rodríguez, A.J.; Carrascosa, A.V.; Martín-Álvarez, P.J.; Moreno-Arribas, V.; Polo, M.C. Influence of the yeast strain on the changes of the amino acids, peptides and proteins during sparkling wine production by the traditional method. Journal of industrial microbiology and biotechnology 2002, 29, 314-322. [CrossRef]

- Tofalo, R.; Perpetuini, G.; Rossetti, A.P.; Gaggiotti, S.; Piva, A.; Olivastri, L.; Cichelli, A.; Compagnone, D.; Arfelli, G. Impact of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and non-Saccharomyces yeasts to improve traditional sparkling wines production. Food Microbiol 2022, 108, 104097. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, R.; García-Martínez, T.; Puig-Pujol, A.; Mauricio, J.C.; Moreno, J. Changes in sparkling wine aroma during the second fermentation under CO2 pressure in sealed bottle. Food Chemistry 2017, 237, 1030-1040. [CrossRef]

- Nunez, Y.P.; Carrascosa, A.V.; González, R.; Polo, M.C.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A.J. Effect of accelerated autolysis of yeast on the composition and foaming properties of sparkling wines elaborated by a champenoise method. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2005, 53, 7232-7237. [CrossRef]

- Coldea, T.E.; Mudura, E.; Fărcaș, A.; Marc, L. Valorisation of hybrid grape variety into processing of red sparkling wine. J. Agroaliment. Process. Technol 2016, 22, 6-9.

- Focea, M.; Luchian, C.-E.; Zamfir, C.-I.; Niculaua, M.; Moroșanu, A.-M.; Nistor, A.-M.; Andrieș, M.-T.; Lăcureanu, F.-G.; Cotea, V.V. Organoleptic chracteristics of experimental sparkling wines. 2017.

- Cotan, Ș.-D.; Popîrdă, A.; Luchian, C.-E.; Colibaba, L.-C.; Zamfir, C.-I.; Cotea, V.V.; Nistor, A.-M. Study of some sparkling wines obtained from local varieties of white grapes in the Cotnari vineyard. 2020.

- Donici, A.; Oslobanu, A.; Fitiu, A.; Babes, A.C.; Bunea, C.I. Qualitative assessment of the white wine varieties grown in Dealu Bujorului vineyard, Romania. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2016, 44, 593-602. [CrossRef]

- Bedreag, I.C.; Cioroiu, I.-B.; Niculaua, M.; Nechita, C.-B.; Cotea, V.V. Volatile Compounds as Markers of Terroir and Winemaking Practices in Fetească Albă Wines of Romania. Beverages 2025, 11. [CrossRef]

- Irimia, L.M.; Patriche, C.V.; Quénol, H. Analysis of viticultural potential and delineation of homogeneous viticultural zones in a temperate climate region of Romania. OENO One 2014, 48. [CrossRef]

- Chircu, C.; Muste, S.; Birou, A.-M.; Man, S. Comparative data regarding the grapes maturation evolution at Feteasca Regala, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir varieties during 2008-2010, in the Jidvei vineyard. Bulletin UASVM Agriculture 2011, 68, 2. [CrossRef]

- Zaldea, G.; Damian, D.; Pârcălabu, L.; Iliescu, M.; Enache, V.; Tănase, A.; Bosoi, I.; Ghiur, A. The evolution of climatic conditions between 1989 and 2021 in representative vine areas of Romania. 2022.

- Vizitiu, D.E.; Buciumeanu, E.-C.; Dincă, L.; Radomir, A.-M. Contributions to a durable Viticulture in Dealu Mare Vineyard with the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Scientific Studies & Research. Series Biology/Studii si Cercetari Stiintifice. Seria Biologie 2022, 31.

- OIV. Compendium of international methods of wine and must analysis; Dijon, France, 2025; Volume Volume 1, p. 1743.

- Odăgeriu, G.; C.S., Cotea V.V., Bârliga N., Ciubucă A. Caracteristicile cromatice C. I. E. Lab-76 ale vinurilor roşii din podgoria Bujoru. „Lucrări ştiinţifice”; Horticultura: Iasi, 2000; Volume I.

- Sauciuc, J.; Gh, O.; Irina, T.; Negurǎ, C. Caracteristicile cromatice CIE Lab 76, ale vinurilor din podgoria Copou Iaşi. 1997.

- Dumitriu, G.-D.; Teodosiu, C.; Gabur, I.; Cotea, V.V.; Peinado, R.A.; López de Lerma, N. Alternative Winemaking Techniques to Improve the Content of Phenolic and Aromatic Compounds in Wines. Agriculture 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- OIV. Review document on sensory analysis of wine. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/3307/review-on-sensory-analysis-of-wine.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Just-Borràs, A.; Moroz, E.; Giménez, P.; Gombau, J.; Ribé, E.; Collado, A.; Cabanillas, P.; Marangon, M.; Fort, F.; Canals, J.M.; et al. Comparison of ancestral and traditional methods for elaborating sparkling wines. Current Research in Food Science 2024, 8, 100768. [CrossRef]

- Raymond Eder, M.L.; Rosa, A.L. Non-Conventional Grape Varieties and Yeast Starters for First and Second Fermentation in Sparkling Wine Production Using the Traditional Method. Fermentation 2021, 7, 321. [CrossRef]

- Cisilotto, B.; Scariot, F.J.; Schwarz, L.V.; Mattos Rocha, R.K.; Longaray Delamare, A.P.; Echeverrigaray, S. Are the characteristics of sparkling wines obtained by the Traditional or Charmat methods quite different from each other? OENO One 2023, 57, 321-331. [CrossRef]

- Pîrcălabu, L.; Barbu, S.P.; Marian; Ion Tudor, G.; Bucur, A. Evaluation of the technological potential of wine grape varieties in the context of climate change in the dealu mare vineyard. 2025.

- OIV. International Code of Oenological Practices. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/publication/2025-04/CPO%202025%20EN.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Charnock, H.; Pickering, G.; Kemp, B. The impact of dosage sugar-type and aging on Maillard reaction-associated products in traditional method sparkling wines. OENO One 2023, 57, 303-322. [CrossRef]

- Cotea, V.V.; Focea, M.C.; Luchian, C.E.; Colibaba, L.C.; Scutarasu, E.C.; Marius, N.; Zamfir, C.I.; Popirda, A. Influence of Different Commercial Yeasts on Volatile Fraction of Sparkling Wines. Foods 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Aliev, T.; Korolev, I.; Yasnov, M.; Nosonovsky, M.; Skorb, E.V. Rose or white, glass or plastic: computer vision and machine learning study of cavitation bubbles in sparkling wines. RSC Adv 2025, 15, 5151-5158. [CrossRef]

- Liger-Belair, G. The physics and chemistry behind the bubbling properties of champagne and sparkling wines: a state-of-the-art review. J Agric Food Chem 2005, 53, 2788-2802. [CrossRef]

- Miliordos, D.E.; Kontoudakis, N.; Kouki, A.; Kanapitsas, A.; Lola, D.; Goulioti, E.; Kotseridis, Y. Influence of vintage and grape maturity on volatile composition and foaming properties of sparkling wine from Savvatiano (Vitis vinifera L.) variety. OENO One 2025, 59. [CrossRef]

- Just-Borràs, A.; Alday-Hernández, M.; García-Roldán, A.; Bustamante, M.; Gombau, J.; Cabanillas, P.; Rozès, N.; Canals, J.M.; Zamora, F. Assessment of Physicochemical and Sensory Characteristics of Commercial Sparkling Wines Obtained Through Ancestral and Traditional Methods. Beverages 2024a, 10. [CrossRef]

- Scutarasu, E.C.; Luchian, C.E.; Vlase, L.; Colibaba, L.C.; Gheldiu, A.M.; Cotea, V.V. Evolution of phenolic profile of white wines treated with enzymes. Food Chem 2021, 340, 127910. [CrossRef]

- Buican, B.-C.; Colibaba, L.C.; Luchian, C.E.; Kallithraka, S.; Cotea, V.V. “Orange” Wine—The Resurgence of an Ancient Winemaking Technique: A Review. Agriculture 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hensel, M.; Di Nonno, S.; Mayer, Y.; Scheiermann, M.; Fahrer, J.; Durner, D.; Ulber, R. Specification and Simplification of Analytical Methods to Determine Wine Color. Processes 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Muñoz, R.; Gómez-Plaza, E.; Martı́nez, A.; López-Roca, J.M. Evolution of the CIELAB and other spectrophotometric parameters during wine fermentation. Influence of some pre and postfermentative factors. Food Research International 1997, 30, 699-705. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Lv, Y.; Nan, H.; Wen, L.; Wang, Z. Research progress of wine aroma components: A critical review. Food Chem 2023, 402, 134491. [CrossRef]

- Ribéreau-Gayon, P.; Dubourdieu, D.; Donèche, B.; Lonvaud, A. Handbook of enology, Volume 1: The microbiology of wine and vinifications; John Wiley & Sons: 2006; Volume 1.

- Swiegers, J.H.; Bartowsky, E.J.; Henschke, P.A.; Pretorius, I.S. Yeast and bacterial modulation of wine aroma and flavour. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 2005, 11, 139-173. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, S.S.; Campos, F.; Cabrita, M.J.; Silva, M.G.D. Exploring the Aroma Profile of Traditional Sparkling Wines: A Review on Yeast Selection in Second Fermentation, Aging, Closures, and Analytical Strategies. Molecules 2025, 30. [CrossRef]

- Riu-Aumatell, M.; Bosch-Fusté, J.; López-Tamames, E.; Buxaderas, S. Development of volatile compounds of cava (Spanish sparkling wine) during long ageing time in contact with lees. Food Chemistry 2006, 95, 237-242. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Garcia, R.; Mauricio, J.C.; Garcia-Martinez, T.; Peinado, R.A.; Moreno, J. Towards a better understanding of the evolution of odour-active compounds and the aroma perception of sparkling wines during ageing. Food Chem 2021, 357, 129784. [CrossRef]

- Ubeda, C.; Kania-Zelada, I.; Del Barrio-Galan, R.; Medel-Maraboli, M.; Gil, M.; Pena-Neira, A. Study of the changes in volatile compounds, aroma and sensory attributes during the production process of sparkling wine by traditional method. Food Res Int 2019, 119, 554-563. [CrossRef]

- Kemp, B.; Alexandre, H.; Robillard, B.; Marchal, R. Effect of production phase on bottle-fermented sparkling wine quality. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2015, 63, 19-38. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ma, D.; Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Mao, J.; Shi, Y.; Han, X.; Zhou, Z.; Mao, J. Assimilable nitrogen reduces the higher alcohols content of huangjiu. Food Control 2021, 121. [CrossRef]

- Carrau, F.M.; Medina, K.; Farina, L.; Boido, E.; Henschke, P.A.; Dellacassa, E. Production of fermentation aroma compounds by Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine yeasts: effects of yeast assimilable nitrogen on two model strains. FEMS Yeast Res 2008, 8, 1196-1207. [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.; Longo, R.; Solomon, M.; Nicolotti, L.; Westmore, H.; Merry, A.; Gnoinski, G.; Ylia, A.; Dambergs, R.; Kerslake, F. Autolysis and the duration of ageing on lees independently influence the aroma composition of traditional method sparkling wine. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 2021, 28, 146-159. [CrossRef]

- Christofi, S.; Papanikolaou, S.; Dimopoulou, M.; Terpou, A.; Cioroiu, I.B.; Cotea, V.; Kallithraka, S. Effect of Yeast Assimilable Nitrogen Content on Fermentation Kinetics, Wine Chemical Composition and Sensory Character in the Production of Assyrtiko Wines. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yuan, M.; Meng, N.; Li, H.; Sun, J.; Sun, B. Influence of nitrogen status on fermentation performances of non--Saccharomyces yeasts: a review. Food Science and Human Wellness 2024, 13, 556-567. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M.; Marrufo-Curtido, A.; Carrascon, V.; Fernandez-Zurbano, P.; Escudero, A.; Ferreira, V. Formation and Accumulation of Acetaldehyde and Strecker Aldehydes during Red Wine Oxidation. Front Chem 2018, 6, 20. [CrossRef]

- Cejudo-Bastante, M.J.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I.; Pérez-Coello, M.S. Micro-oxygenation and oak chip treatments of red wines: Effects on colour-related phenolics, volatile composition and sensory characteristics. Part I: Petit Verdot wines. Food Chemistry 2011, 124, 727-737. [CrossRef]

- Marrufo-Curtido, A.; de-la-Fuente-Blanco, A.; Saenz-Navajas, M.P.; Ferreira, V.; Bueno, M.; Escudero, A. Sensory Relevance of Strecker Aldehydes in Wines. Preliminary Studies of Its Removal with Different Type of Resins. Foods 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Boschfuste, J.; Riuaumatell, M.; Guadayol, J.; Caixach, J.; Lopeztamames, E.; Buxaderas, S. Volatile profiles of sparkling wines obtained by three extraction methods and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis. Food Chemistry 2007, 105, 428-435. [CrossRef]

- Csutoras, C.; Bakos-Barczi, N.; Burkus, B. Medium chain fatty acids and fatty acid esters as potential markers of alcoholic fermentation of white wines. Acta Alimentaria 2022, 51, 33-42. [CrossRef]

| Code | Grape Variety | Year | Particularity | Maturation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR19d | Fetească regală | 2019 | Undisgorged | 36 months |

| FR19 | Fetească regală | 2019 | Disgorged | 36 months |

| FR21d | Fetească regală | 2021 | Undisgorged | 9 months |

| FR21 | Fetească regală | 2021 | Disgorged | 9 months |

| TR19d | Tămâioasă românească | 2019 | Undisgorged | 36 months |

| TR19 | Tămâioasă românească | 2019 | Disgorged | 36 months |

| TR21d | Tămâioasă românească | 2021 | Undisgorged | 9 months |

| TR21 | Tămâioasă românească | 2021 | Disgorged | 9 months |

| FA19d | Fetească albă | 2021 | Undisgorged | 36 months |

| FA19 | Fetească albă | 2021 | Disgorged | 36 months |

| FA21d | Fetească albă | 2021 | Undisgorged | 9 months |

| FA21 | Fetească albă | 2021 | Disgorged | 9 months |

| Sample | Alcohol (v/v) |

Total Acidity (g L-1 tartaric acid) |

Volatine acidity (g L-1 acetic acid) | Free Sulfur (mg L-1) |

Total sulfur (mg L-1) | Residual sugars (g L-1 ) | Pressure (bar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR19d | 13.33b | 6.37b | 0.37455c | 2.3b | 86a | 3.27d | 7.1c |

| FR19 | 13.39b | 6.34b | 0.39375b | 19a | 103b | 3.01c | 6.2a |

| FR21d | 13.13a | 6.48c | 0.37455c | 2.1b | 78d | 2.15e | 7.4b |

| FR21 | 13.06a | 6.53c | 0.39375b | 22a | 112c | 1.95b | 6.8c |

| TR19d | 13.31b | 6.12a | 0.39455b | 5.5d | 89a | 2.67a | 6.7d |

| TR19 | 13.53c | 6.25a | 0.41375a | 23c | 100b | 2.36f | 6.3a |

| TR21d | 13.42c | 6.24a | 0.36455c | 3.5b | 85a | 3.67g | 7.4b |

| TR21 | 13.38b | 6.29a | 0.38375b | 25c | 117c | 3.43d | 6.8e |

| FA19d | 13.32b | 6.18a | 0.40455a | 6.3b | 81a | 1.85b | 7.4b |

| FA19 | 13.13a | 6.21a | 0.42375a | 21a | 93a | 2.65a | 6.3a |

| FA21d | 13.29b | 6.28a | 0.40455a | 7.3b | 91a | 2.85c | 7.4b |

| FA21 | 13.13a | 6.31b | 0.42375d | 21a | 105a | 2.67a | 6.3d |

| Probă | Clarity (L*) |

Cromaticity | Croma (C) |

Tonality (H) |

Luminosity | Tint | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| green 0<a*>0 red | blue 0<b*>0 yellow | ||||||

| FR19d | 98.0 | -1.04 | 7.11 | 7.18 | -81.71 | 0.14 | 3.87 |

| FR19 | 98.0 | -1.05 | 7.14 | 7.22 | -81.65 | 0.14 | 3.93 |

| FR 21d | 98.7 | -0.98 | 7.27 | 7.33 | -82.30 | 0.12 | 5.21 |

| FR21 | 98.8 | -0.96 | 7.20 | 7.26 | -82.41 | 0.12 | 5.23 |

| TR19d | 99.1 | -0.87 | 5.35 | 5.42 | -80.81 | 0.09 | 5.65 |

| TR19 | 98.3 | -0.82 | 6.96 | 7.01 | -83.24 | 0.13 | 4.10 |

| TR21d | 99.1 | -0.53 | 4.27 | 4.30 | -82.89 | 0.08 | 4.81 |

| TR21 | 98.2 | -1.11 | 8.04 | 8.12 | -82.12 | 0.15 | 4.73 |

| FA19d | 98.3 | -0.97 | 5.9 | 5.98 | -80.69 | 0.12 | 3.93 |

| FA19 | 98.7 | -0.86 | 6.97 | 7.02 | -82.98 | 0.12 | 4.83 |

| FA21d | 98.9 | -0.71 | 5.45 | 5.50 | -82.59 | 0.09 | 4.85 |

| FA21 | 98.6 | -0.85 | 6.88 | 6.93 | -82.91 | 0.12 | 4.69 |

| Sample | Ethyl formate | Ethyl acetate | Ethyl propionate | Ethyl isobutyrate | Ethyl butanoate | Ethyl isovalerate | Isoamylacetate | Ethyl hexanoate | Hexyl acetate | Ethyl caprylate | Ethyl caprate | Butanedioic acid, diethyl ester |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR19d | 13.97±0.7 | 67.97±14.07* | 0.59±0.05 | 0.6±0.36 | 1.67±1.18 | 0.36±0.05* | 3.19±0.71* | 52.82±11.37* | ND | 30.64±7.03* | 5.36±1.25* | 1.5±0.13 |

| FR19 | 19.67±2.85* | 88.42±6.8* | 0.64±0.22 | 0.94±0.32 | 2.91±1.67 | 0.44±0.23 | 4.02±0.52* | 61.75±1.89 | ND | 33.48±0.45* | 4.74±0.49* | 1.42±0.09 |

| FR21d | 14.73±4.11 | 72.01±6.83 | 0.54±0.08 | 0.61±0.14 | 2.33±1.59 | 0.39±0.24* | 12.15±0.29* | 70.53±7.24* | 0.39±0.24* | 69.76±8.92* | 14.08±1.69* | 1.19±0.18 |

| FR21 | 11.07±1.94* | 59.98±3.92* | 0.58±0.16 | 0.71±0.22 | 1.55±0.55 | 0.58±0.17 | 15.46±0.8* | 59.22±5.75* | 0.68±0.28* | 49.1±11.66* | 7.18±3.65* | 0.92±0.19* |

| TR19d | 14.77±1.2 | 86.38±6.78* | 0.44±0.1 | 0.94±0.29 | 3.06±0.46 | 1.01±0.08* | 2.3±0.33* | 55.25±3.93* | ND | 34.39±31.18 | 7.36±2.94* | 1.88±0.17* |

| TR19 | 22.71±4.33* | 67.48±47.58* | 0.65±0.09 | 1.29±0.16* | 2.35±1.22 | 0.97±0.26* | 5.37±9.97* | 49±17.17* | ND | 51.63±21.66 | 5.77±2.02* | 1.44±0.38 |

| TR21d | 14.64±2.49 | 61.11±10.3* | 0.48±0.18 | 0.62±0.34 | 0.99±0.07 | 0.67±0.03 | 10.98±0.46* | 58.04±12.27* | 2.25±0.48* | 41.48±8.38* | 4.34±0.49* | 0.93±0.13* |

| TR21 | 14.01±2.58 | 70.72±1.73 | 0.45±0.04 | 0.5±0.06* | 1.63±0.81 | 0.63±0.13 | 9.98±0.37* | 80.64±2.32* | 2.91* | 93.03±13.23* | 6.41±1.07* | 1.04±0.08* |

| FA19d | 14.64±2.49 | 61.11±10.3* | 0.48±0.18 | 0.62±0.34 | 0.99±0.07 | 0.67±0.03 | 10.98±0.46* | 58.04±12.27* | 2.25±0.48* | 41.48±8.38* | 4.34±0.49* | 0.93±0.13* |

| FA19 | 17.7±0.06 | 87.33±8.01* | 0.62±0.06 | 1.27±0.12* | 3.89±1.59 | 0.61±0.28* | 13.89±1.04* | 57.89±3.36* | 0.34±0.13* | 35.31±4.22*‘ | 7.16±1.63* | 1.44±0.23 |

| FA21d | 16.26±2.32 | 83.55±7.09* | 0.63±0.15 | 1.2±0.33* | 2.38±1.45 | 0.83±0.15* | 13.24±2.37* | 62.27±5.42 | 0.44±0.11* | 58.71±24.67 | 8.29±1.76* | 1.38±0.1 |

| FA21 | 12.44±1.12 | 71.23±4.58 | 0.59±0.2 | 0.66±0.28 | 3.68±0.35 | 0.8±0.07 | 9.53±0.58* | 66.92±4.3* | 0.46±0.11* | 90.35±7.64* | 6.49±0.56* | 1.04±0.15 |

| Sample | FR19d | FR19 | FR21d | FR21 | TR19d | TR19 | TR21d | TR21 | FA19d | FA19 | FA21d | FA21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher alcohols | ||||||||||||

| Propanol | 1.59±0.05* | 2.26±0* | 2.44±0.14* | 2.68±0.73* | ND | ND | 2.29±0.43* | 2.02±0* | 2.66±0* | 2.19±0.84* | 2.29±0.22* | ND |

| Isobutil alcohol | 5.37±5.99* | 1.74±0.64* | 4.06±0.39* | ND | ND | 2.7±0* | 1.79±0* | 1.59±0* | 1.26±0.13 | 1.41±0.08 | 5.49±3.44 | 6.52±1.32 |

| MTHFA** | 4.52±0.87 | 6.9±3.3 | 4.75±0 | 5.71±3.76 | 6.87±2.01 | 6.83±3.67 | 5.74±2.84 | 5.35±0.97 | 6.43±5.32 | 6.3±2.81 | 0.61±0* | ND |

| 3-hexanol | 0.09±0 | 0.09±0.02 | 0.12±0.03 | 0.08±0.01 | 0.11±0.02 | ND | ND | 0.2±0.12 | 0.13±0.01 | 0.11±0.05 | 0.21±0.07 | 0.15±0.08 |

| 1-pentanol | 73±2.09* | 78.87±6.82* | 106.81±14.01* | 91.92±9.64* | 77.9±4.19* | 62.67±26.19* | 95.87±8.37* | 101.25±4.29* | 91.89±1.22* | 91.81±6.81* | 99.28±7.23* | 87.51±3.18* |

| 1-hexanol | 0.63±0.07* | 0.47±0.07* | 0.94±0.27* | 0.87±0.18* | 0.92±0.02* | 0.71±0.24* | 2.21±0.38* | 1.99±0.12* | 0.5±0.21* | 0.48±0.14* | 1.28±0.15* | 1.1±0.08* |

| Phenylethyl alcohol | 0.22±0.02* | 0.16±0.03* | 0.28±0.02* | 0.2±0.01* | 0.23±0.01* | 0.23±0.05* | 0.46±0.09* | 0.45±0.02* | 0.23±0.06* | 0.23±0.01* | 0.44±0.07* | 0.32±0.08* |

| Aldehydes | ||||||||||||

| Acetaldehyde | 82.22±4.06* | 88.05±12.93* | 89.29±2.16* | 83.11±11.67 | 74.09±15.05* | 54.81±9.82* | 79.3±8.2* | 64.99±24.18* | 69.38±10.12* | 73.16±6.11* | 67.94±7.65* | 64.33±4.81* |

| Propanal | 0.15±0.07 | 0.27±0.2 | 0.4±0.26* | 0.42±0.17* | 0.27±0.19 | 0.26±0.11 | 0.26±0.11 | 0.22±0.2 | 0.42±0.06* | 0.23±0.09 | 0.24±0.14 | 0.21±0.07 |

| 3-methylbutanal | 0.85±1.04* | 1.16±1.72 | 2.5±0.14* | 2.23±0.52* | 2.65±0.33* | 2.13±0.48* | 2.36±0.12* | 0.92±0 | 1.07±0.86 | 0.93±0.15 | 2.09±1.18* | 2.41±0.18* |

| Acids | ||||||||||||

| Hexanoic acid | 0.05* | ND | ND | 0.08±0.03* | 0.09±0.01* | 0.11±0* | 0.1±0* | 0.11±0.04* | 0.29±0.04* | 0.27±0* | 0.2±0.03* | 0.13±0.01* |

| Octanoic Acid | 0.19±0.02* | 0.1±0.04* | 0.05±0* | 0.06±0.05* | 0.39±0.08* | 0.45±0.03* | 0.6±0.07* | 0.61±0.18* | 1.16±0.44* | 1.21±0.14* | 0.99±0.18* | 0.8±0.15* |

| Decanoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.18±0.01 | ND | 0.43±0.05 | 0.61±0.18 | 0.53±0.36 | 0.34±0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).