Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This study investigated on the impact of different aging containers on the volatile composition and quality of Negroamaro wine, a key variety from Apulia, Italy. Seven vessel types were evaluated: traditional Apulian amphorae (ozza), five types of oak barrels (American oak, French oak, European oak, a French + European oak, and a multi-wood mix), galls bottles as control. The impact of the vessels was evaluated after 6 months aging through characterization of phenolic, volatile and sensory profiles. Amphorae allowed a specific evolution of the wine’s primary aromas, including as fruity and floral notes, while enhancing volatile compounds like furaneol, which contributes to caramel and red fruit nuances and also 3-methyl-2,4-nonanedione, a key compound related to anise, plum and premature aging, depending on its concetration. This container also demonstrated effectiveness in stabilizing anthocyanin-tannin complexes, supporting color stabilization. Oak barrels allowed to obtain different outcomes in terms of color stabilization, volatile profile, aroma and astringency. French oak exhibited the highest phenolic and tannin levels, enhancing anthocyanin stabilization and color intensity. European oak followed closely, while American oak excelled in color stabilization with tannins less reactive to polymers. Mixed wood barrels showed lower phenolic extraction and the best astringency evolution.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aging Experiment

2.2. Chemical Analysis

2.3. Analysis of Volatile Compounds

2.4. Sensory Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenols

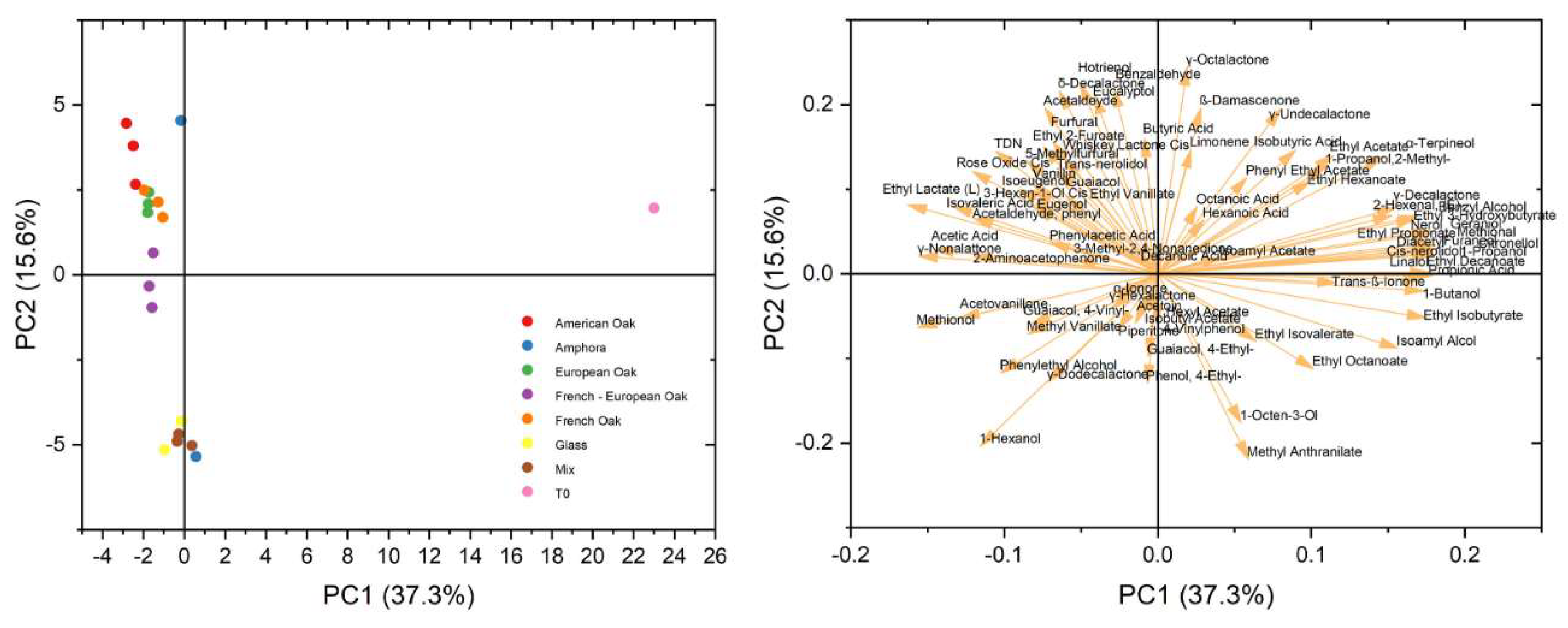

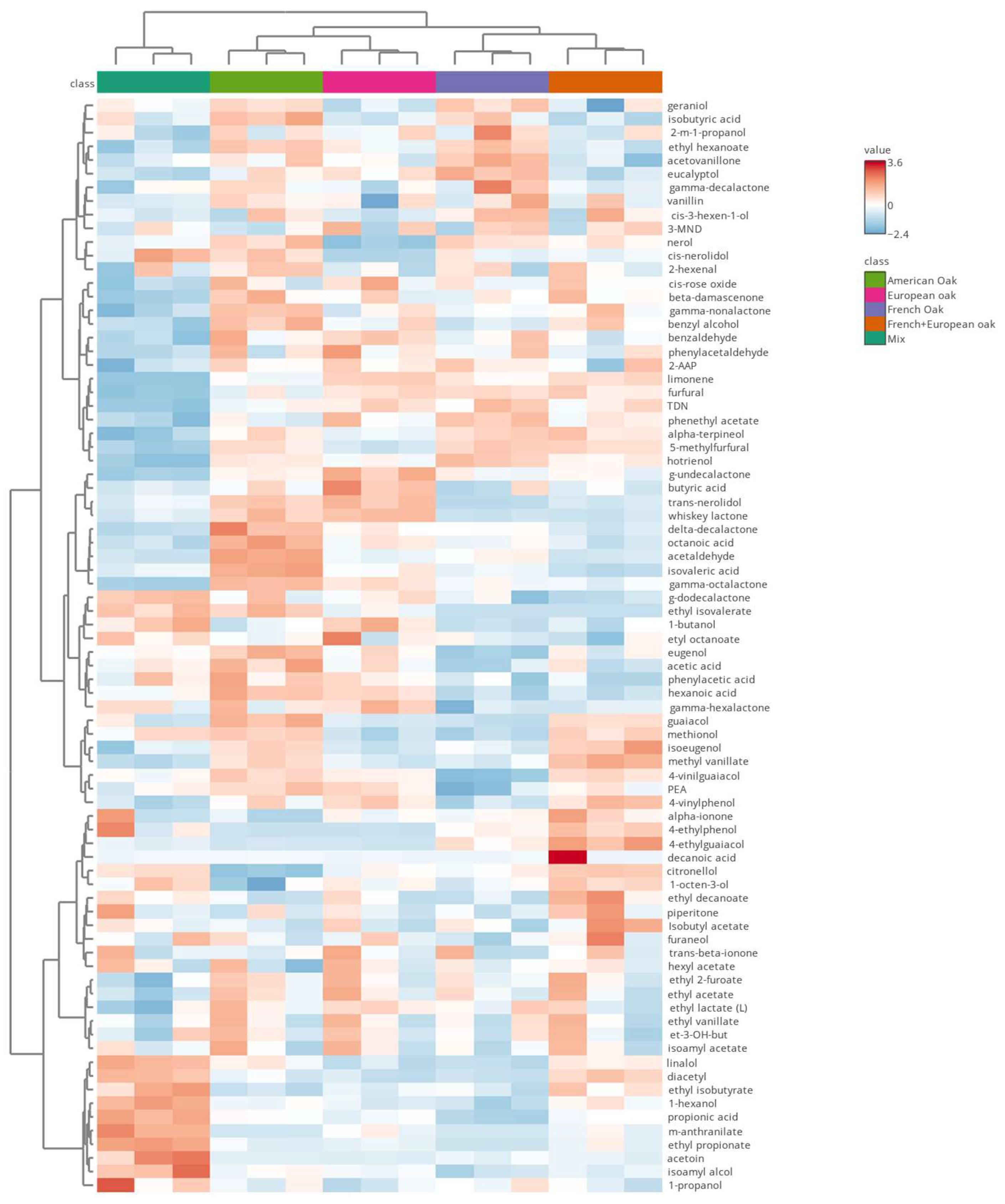

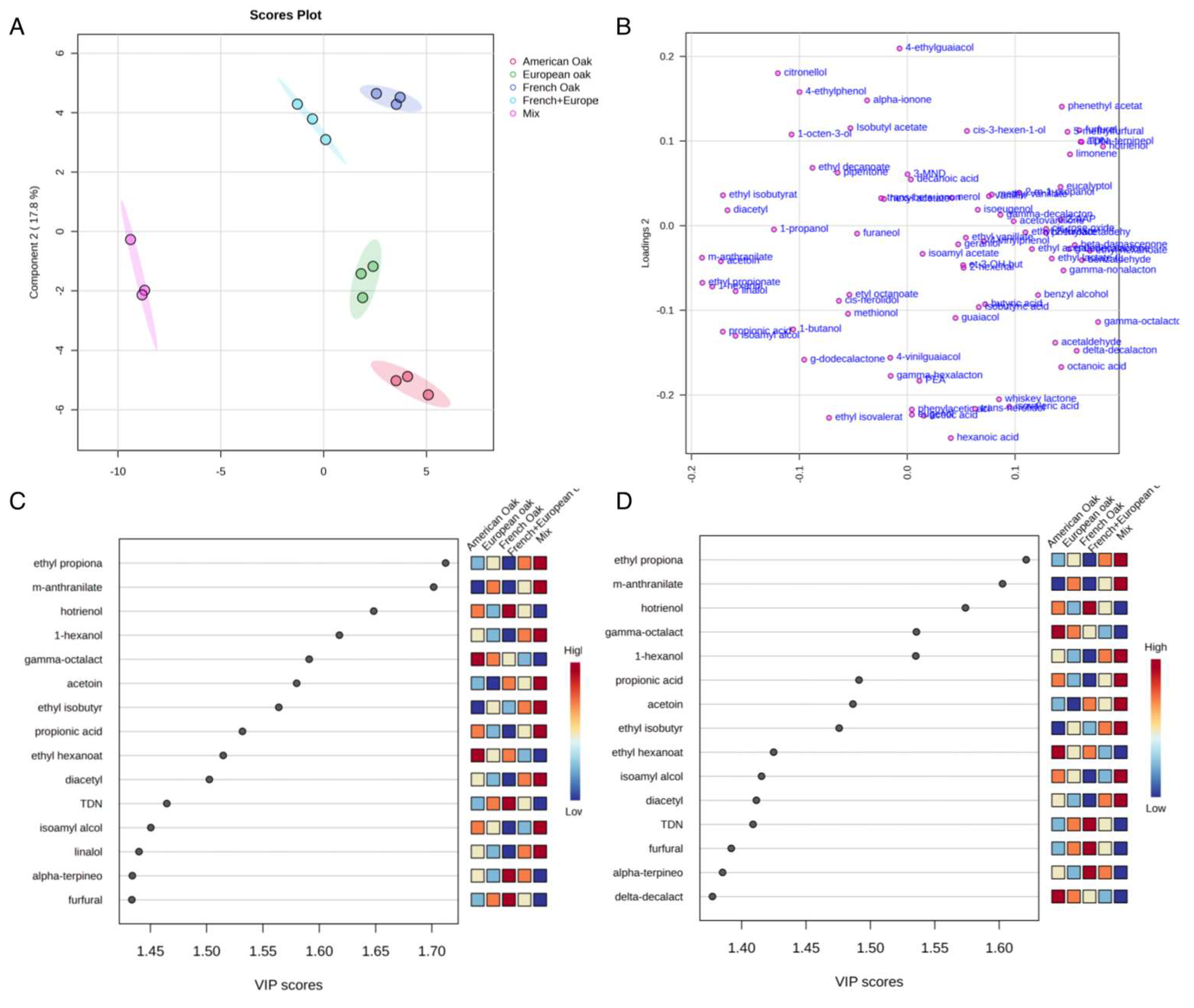

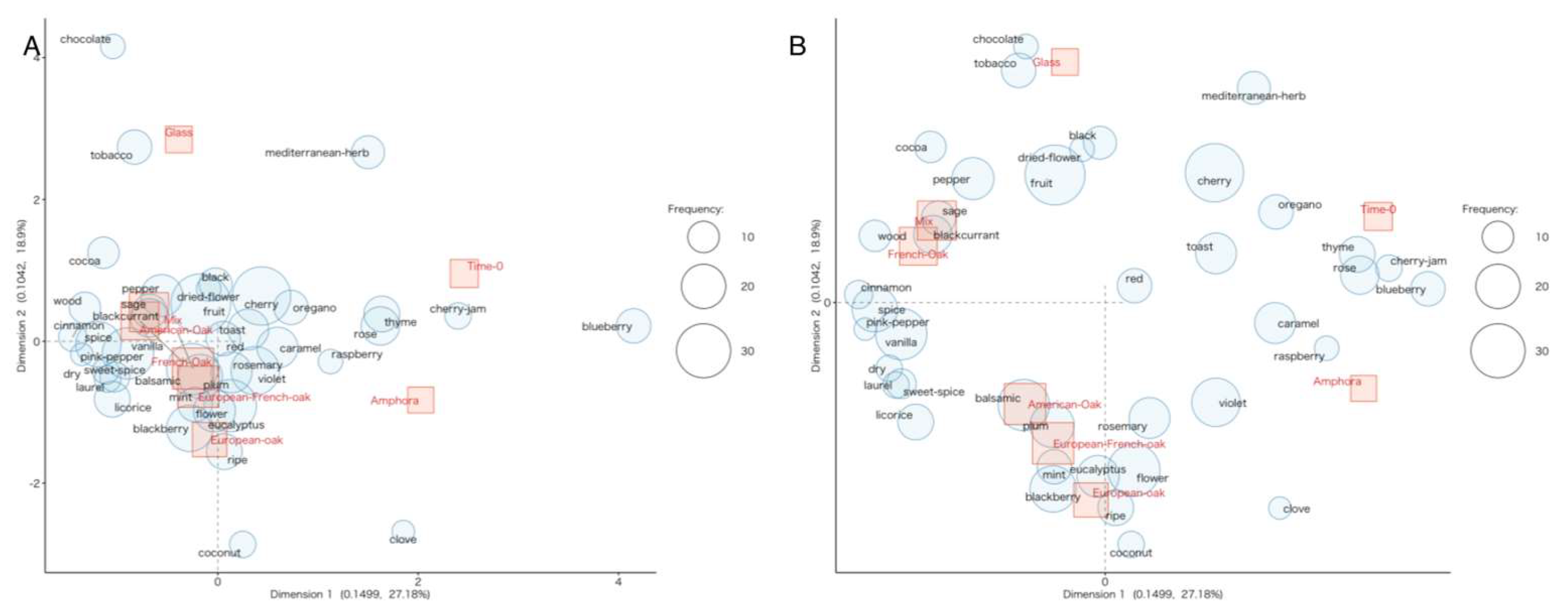

3.2. Volatile Compounds

3.2.1. Discrimination Among Woods

3.2.2. Focus on Some Grape-Derived Compounds

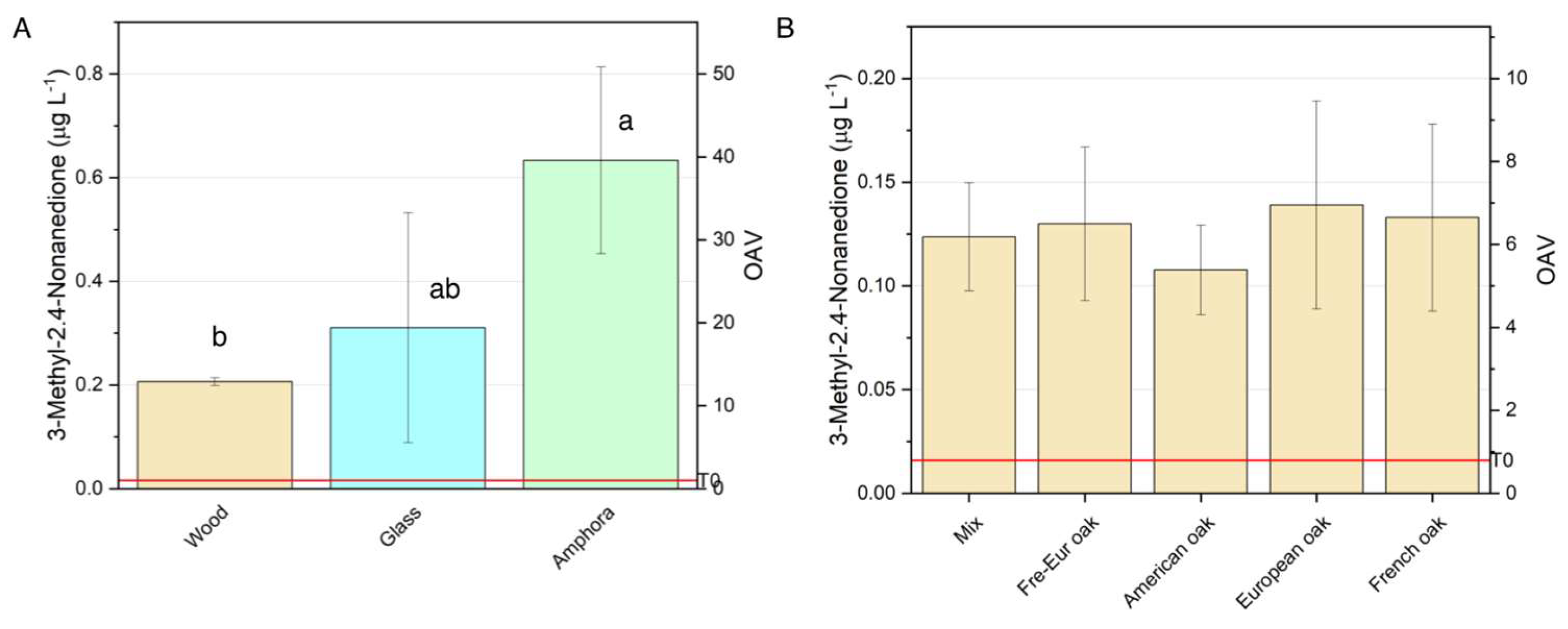

3.2.2.1. 3-methyl-2,4-nonanedione

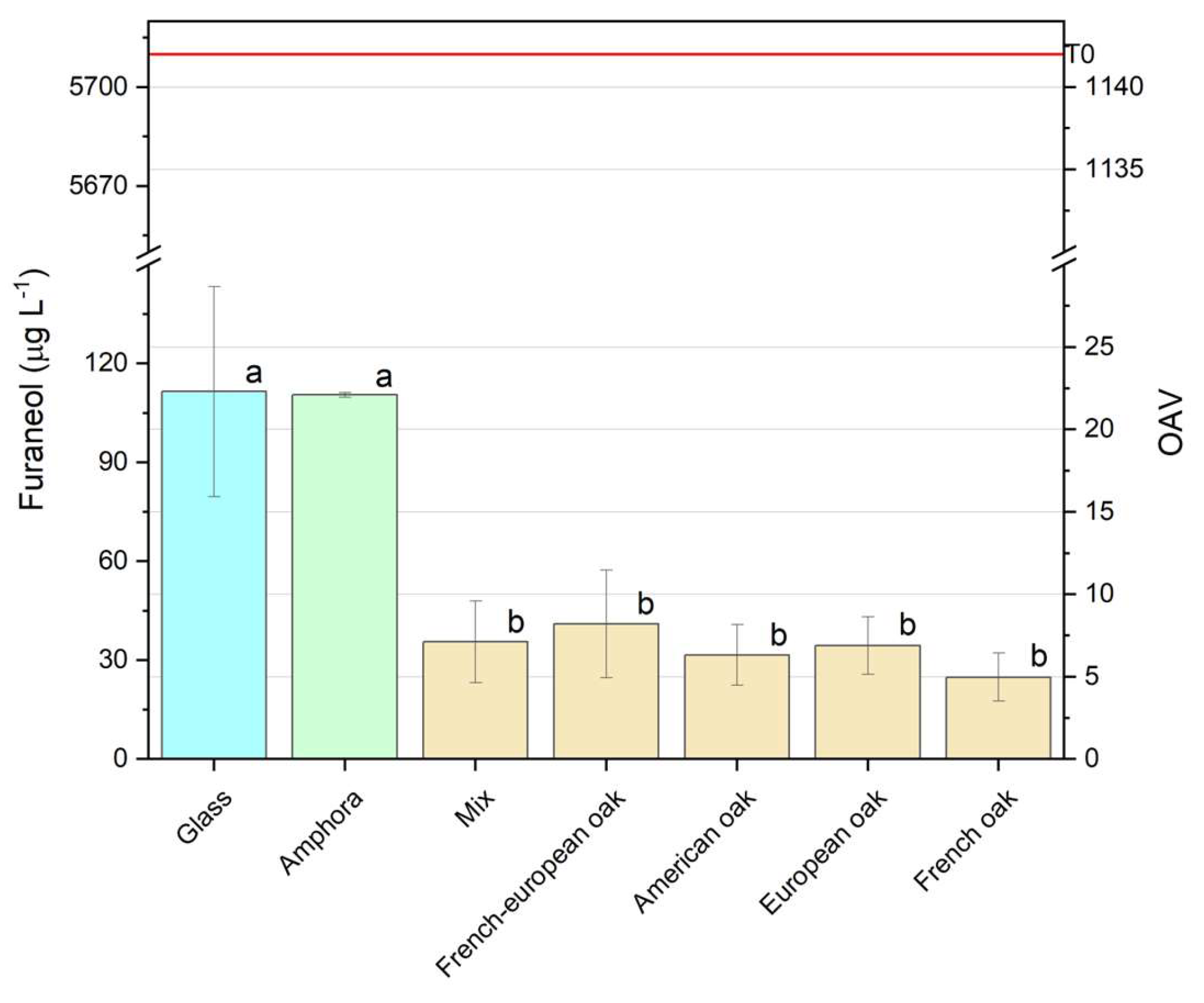

3.2.2.2. Furaneol

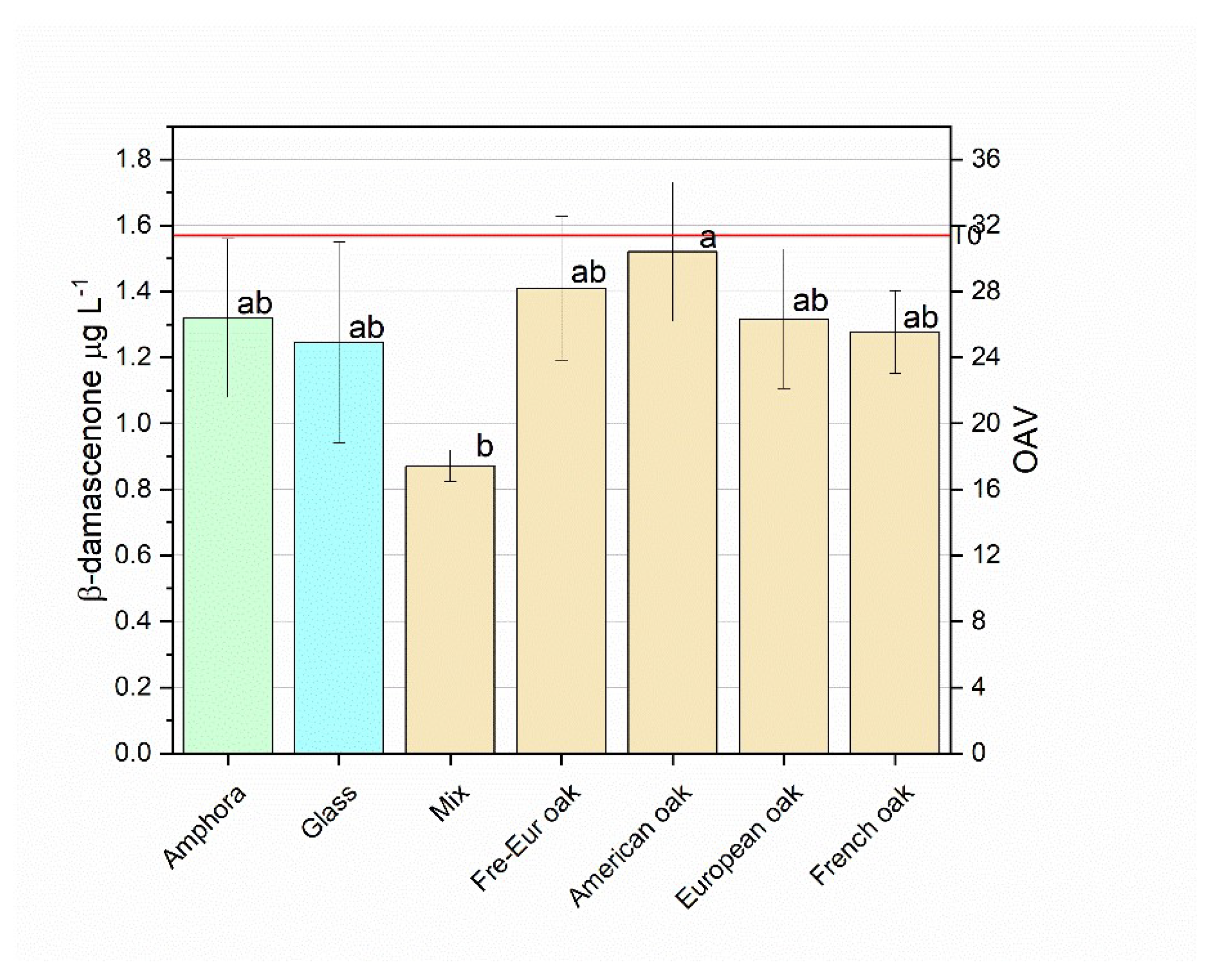

3.2.2.3. β-Damascenone

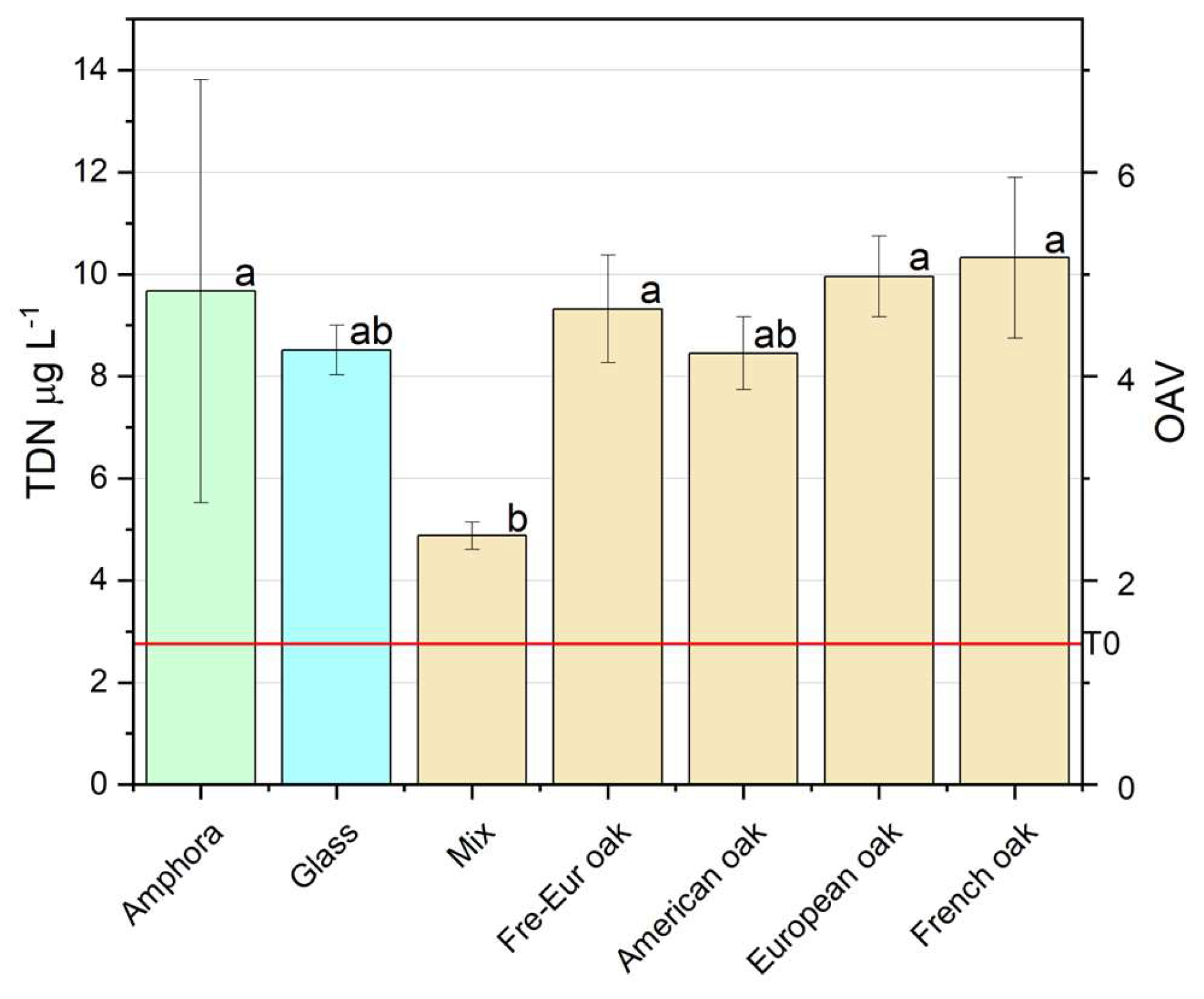

3.2.2.4. TDN

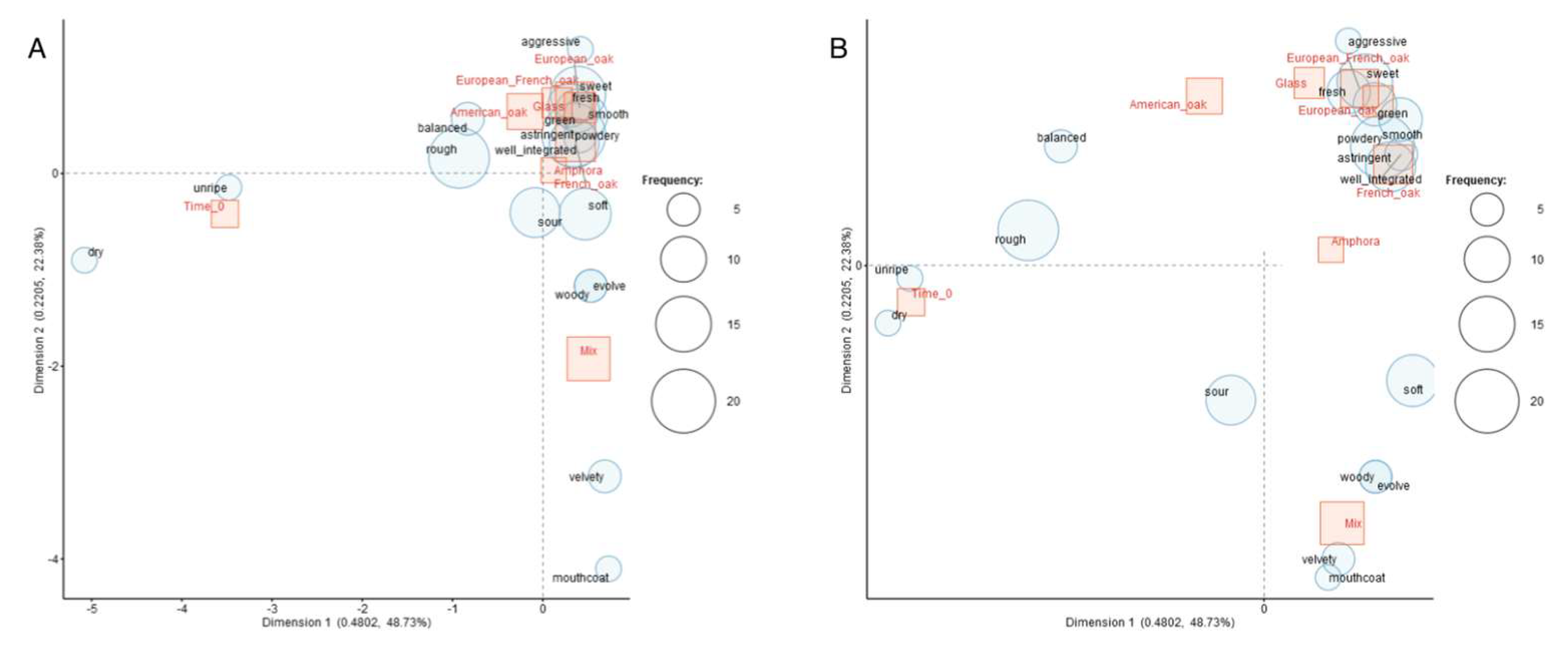

3.3. Sensory Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carpena, M.; Pereira, A.G.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Wine Aging Technology: Fundamental Role of Wood Barrels. Foods 2020, 9, 1160. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Plaza, E.; Bautista-Ortín, A.B. Chapter 10 - Emerging Technologies for Aging Wines: Use of Chips and Micro-Oxygenation. In Red Wine Technology; Morata, A., Ed.; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 149–162 ISBN 978-0-12-814399-5.

- Maioli, F.; Picchi, M.; Guerrini, L.; Parenti, A.; Domizio, P.; Andrenelli, L.; Zanoni, B.; Canuti, V. Monitoring of Sangiovese Red Wine Chemical and Sensory Parameters along One-Year Aging in Different Tank Materials and Glass Bottle. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 221–239. [CrossRef]

- Nevares, I.; Alamo-Sanza, M. New Materials for the Aging of Wines and Beverages: Evaluation and Comparison. In; 2017 ISBN 978-0-12-811516-9.

- Diaz, C.; Laurie, V.F.; Molina, A.M.; Bucking, M.; Fischer, R. Characterization of Selected Organic and Mineral Components of Qvevri Wines. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2013, 64, 532–537. [CrossRef]

- Butzke, C.E. Winemaking Problems Solved; Elsevier, 2010; ISBN 978-0-85709-018-8.

- Morata, A.; González, C.; Tesfaye, W.; Loira, I.; Suárez-Lepe, J.A. Chapter 3 - Maceration and Fermentation: New Technologies to Increase Extraction. In Red Wine Technology; Morata, A., Ed.; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 35–49 ISBN 978-0-12-814399-5.

- Gómez-Plaza, E.; Cano-López, M. A Review on Micro-Oxygenation of Red Wines: Claims, Benefits and the Underlying Chemistry. Food Chemistry 2011, 125, 1131–1140. [CrossRef]

- Egaña-Juricic, M.E.; Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Moreno-Simunovic, Y. Making Wine in Pañul’s Craft Pottery Vessels: A First Approach in the Study of the Dynamic of Alcoholic Fermentation and Wine Volatile Composition. Ciência Téc. Vitiv. 2022, 37, 29–38. [CrossRef]

- Nevares, I.; del Alamo-Sanza, M. Characterization of the Oxygen Transmission Rate of New-Ancient Natural Materials for Wine Maturation Containers. Foods 2021, 10, 140. [CrossRef]

- Arobba, D.; Bulgarelli, F.; Camin, F.; Caramiello, R.; Larcher, R.; Martinelli, L. Palaeobotanical, Chemical and Physical Investigation of the Content of an Ancient Wine Amphora from the Northern Tyrrhenian Sea in Italy. Journal of Archaeological Science 2014, 45, 226–233. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, B. Wine Producers Have Started Making Wine in Amphora. Again. | BKWine Magazine | Available online: https://www.bkwine.com/features/winemaking-viticulture/making-wine-in-amphora/ (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- White, W.; Catarino, S. How Does Maturation Vessel Influence Wine Quality? A Critical Literature Review. Ciência Téc. Vitiv. 2023, 38, 128–151. [CrossRef]

- Harutyunyan, M.; Malfeito-Ferreira, M. Historical and Heritage Sustainability for the Revival of Ancient Wine-Making Techniques and Wine Styles. Beverages 2022, 8, 10. [CrossRef]

- Caillaud, C. Il fenomeno del vino in anfora nell’Italia di oggi. territoiresduvin 2014. [CrossRef]

- Colonna, V. L’acqua nella tradizione popolare salentina 2018.

- Frassante, G.; Masciullo, M.S. Il lessico dei figuli di Cutrofiano. Storia e lingua dei demiurghi dell’argilla. Lingue e linguaggi 2022, 51, 289–303. [CrossRef]

- Manacorda, D. Il vino del Salento e le sue anfore. In Proceedings of the El Vi a l’antiguitat . Economia, producció i comerç al Mediterrani occidental: II Col·loqui Internacional d’Arqueologia Romana, actes (Barcelona 6-9 de maig de 1998), 1999, ISBN 84-88758-02-2, págs. 319-331; Museu de Badalona, 1999; pp. 319–331.

- Toci, A.T.; Crupi, P.; Gambacorta, G.; Dipalmo, T.; Antonacci, D.; Coletta, A. Free and Bound Aroma Compounds Characterization by GC-MS of Negroamaro Wine as Affected by Soil Management: GC-MS Aromatic Characterization of Negroamaro Wine. J. Mass. Spectrom. 2012, 47, 1104–1112. [CrossRef]

- Tufariello, M.; Capone, S.; Siciliano, P. Volatile Components of Negroamaro Red Wines Produced in Apulian Salento Area. Food Chemistry 2012, 132, 2155–2164. [CrossRef]

- Drappier, J.; Thibon, C.; Rabot, A.; Geny-Denis, L. Relationship between Wine Composition and Temperature: Impact on Bordeaux Wine Typicity in the Context of Global Warming—Review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2019, 59, 14–30. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.A.; Matthews, M.A.; Waterhouse, A.L. Changes in Grape Seed Polyphenols during Fruit Ripening. Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 77–85. [CrossRef]

- Rustioni, L.; Cola, G.; VanderWeide, J.; Murad, P.; Failla, O.; Sabbatini, P. Utilization of a Freeze-Thaw Treatment to Enhance Phenolic Ripening and Tannin Oxidation of Grape Seeds in Red (Vitis Vinifera L.) Cultivars. Food Chemistry 2018, 259, 139–146. [CrossRef]

- Kliewer, W.M.; Torres, R.E. Effect of Controlled Day and Night Temperatures on Grape Coloration. Am J Enol Vitic. 1972, 23, 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, M.D.; Dambergs, R.G.; Herderich, M.J.; Smith, P.A. High Throughput Analysis of Red Wine and Grape PhenolicsAdaptation and Validation of Methyl Cellulose Precipitable Tannin Assay and Modified Somers Color Assay to a Rapid 96 Well Plate Format. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4651–4657. [CrossRef]

- Prezioso, I.; Fioschi, G.; Rustioni, L.; Mascellani, M.; Natrella, G.; Venerito, P.; Gambacorta, G.; Paradiso, V.M. Influence of Prolonged Maceration on Phenolic Compounds, Volatile Profile and Sensory Properties of Wines from Minutolo and Verdeca, Two Apulian White Grape Varieties. LWT 2024, 192, 115698. [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, R.; Cravero, M.; Gentilini, N. Metodi per Lo Studio Dei Polifenoli. L’Enotecnico 1989, XXV, 83–89.

- Ribereau-Gayon, P.; Stonestreet, E. Dosage Des Tanins Du Vin Rouge et Determination de Leur Structure. Chimique Analytique 1966, 48, 188–196.

- Glories, Y. La Couleur Des Vins Rouges. 2e Partie : Mesure, Origine et Interprétation. OENO One 1984. [CrossRef]

- Lukić, I.; Horvat, I. Differentiation of Commercial PDO Wines Produced in Istria (Croatia) According to Variety and Harvest Year Based on HS-SPME-GC/MS Volatile Aroma Compounds Profiling. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2017, 55. [CrossRef]

- Berger, R.G. Flavours and Fragrances: Chemistry, Bioprocessing and Sustainability; 2007; p. 648; ISBN 978-3-540-49338-9.

- Black, C. a.; Parker, M.; Siebert, T. e.; Capone, D. l.; Francis, I. l. Terpenoids and Their Role in Wine Flavour: Recent Advances. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 2015, 21, 582–600. [CrossRef]

- Capone, S.; Tufariello, M.; Francioso, L.; Montagna, G.; Casino, F.; Leone, A.; Siciliano, P. Aroma Analysis by GC/MS and Electronic Nose Dedicated to Negroamaro and Primitivo Typical Italian Apulian Wines. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2013, 179, 259–269. [CrossRef]

- Diez-Ozaeta, I.; Lavilla, M.; Amárita, F. Wine Aroma Profile Modification by Oenococcus Oeni Strains from Rioja Alavesa Region: Selection of Potential Malolactic Starters. Int J Food Microbiol 2021, 356, 109324. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; López, R.; Cacho, J.F. Quantitative Determination of the Odorants of Young Red Wines from Different Grape Varieties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 1659–1667. [CrossRef]

- Francis, I.L.; Newton, J.L. Determining Wine Aroma from Compositional Data. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2005, 11, 114–126. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Ortín, N.; Escudero, A.; López, R.; Cacho, J. Chemical Characterization of the Aroma of Grenache Rosé Wines: Aroma Extract Dilution Analysis, Quantitative Determination, and Sensory Reconstitution Studies. J Agric Food Chem 2002, 50, 4048–4054. [CrossRef]

- Guth, H. Quantitation and Sensory Studies of Character Impact Odorants of Different White Wine Varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 3027–3032. [CrossRef]

- Kritzinger-Stadler, E.; Bauer, F.; du Toit, W. Role of Glutathione in Winemaking: A Review. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2012, 61. [CrossRef]

- Langen, J.; Wegmann-Herr, P.; Schmarr, H.-G. Quantitative Determination of α-Ionone, β-Ionone, and β-Damascenone and Enantiodifferentiation of α-Ionone in Wine for Authenticity Control Using Multidimensional Gas Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometric Detection. Anal Bioanal Chem 2016, 408, 6483–6496. [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.-F.; Xu, T.-F.; Song, C.-Z.; Yu, Y.; Hu, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Xi, Z.-M. Melatonin Treatment of Pre-Veraison Grape Berries to Increase Size and Synchronicity of Berries and Modify Wine Aroma Components. Food Chem 2015, 185, 127–134. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.C.; Pilkington, L.I.; Barker, D.; Deed, R.C. Saturated Linear Aliphatic γ- and δ-Lactones in Wine: A Review. J Agric Food Chem 2022, 70, 15325–15346. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.A.; Zea, L.; Moyano, L.; Medina, M. Aroma Compounds as Markers of the Changes in Sherry Wines Subjected to Biological Ageing. Food Control 2004, 16, 333–338. [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Wang, P.; Xiao, Z.; Zhu, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, R. Evaluation of the Perceptual Interaction among Ester Aroma Compounds in Cherry Wines by GC–MS, GC–O, Odor Threshold and Sensory Analysis: An Insight at the Molecular Level. Food Chemistry 2019, 275, 143–153. [CrossRef]

- Noguerol-Pato, R.; González-Barreiro, C.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J. Quantitative Determination and Characterisation of the Main Odourants of Mencía Monovarietal Red Wines. Food Chemistry 2009, 117, 473–484. [CrossRef]

- Peinado, R.A.; Moreno, J.; Bueno, J.E.; Moreno, J.A.; Mauricio, J.C. Comparative Study of Aromatic Compounds in Two Young White Wines Subjected to Pre-Fermentative Cryomaceration. Food Chemistry 2004, 84, 585–590. [CrossRef]

- Perestrelo, R.; Silva, C.; Câmara, J.S. Madeira Wine Volatile Profile. A Platform to Establish Madeira Wine Aroma Descriptors. Molecules 2019, 24, 3028. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.; Oliveira, A.S.; Azevedo, J.; De Freitas, V.; Lopes, P.; Roseira, I.; Cabral, M.; Guedes de Pinho, P. Assessment of Oxidation Compounds in Oaked Chardonnay Wines: A GC–MS and 1H NMR Metabolomics Approach. Food Chemistry 2018, 257, 120–127. [CrossRef]

- Pons, A.; Lavigne, V.; Landais, Y.; Darriet, P.; Dubourdieu, D. Distribution and Organoleptic Impact of Sotolon Enantiomers in Dry White Wines. J Agric Food Chem 2008, 56, 1606–1610. [CrossRef]

- Pons, A.; Lavigne, V.; Darriet, P.; Dubourdieu, D. Identification and Analysis of Piperitone in Red Wines. Food Chemistry 2016, 206, 191–196. [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Lan, Y.; Han, S.; Liang, N.; Zhu, B.; Shi, Y.; Duan, C. Comprehensive Investigation of Lactones and Furanones in Icewines and Dry Wines Using Gas Chromatography-Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry. Food Research International 2020, 137, 109650. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bencomo, J.J.; Ortega-Heras, M.; Pérez-MAGARIÑO, S.; González-Huerta, C.; Rodríguez-Bencomo, J.J.; Ortega-Heras, M.; Pérez-MAGARIÑO, S.; González-Huerta, C. Volatile Compounds of Red Wines Macerated with Spanish, American, and French Oak Chips. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2009, 57, 6383–6391. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, G.L.; Gates, M.J.; Ferry, F.X.; Lavin, E.H.; Kurtz, A.J.; Acree, T.E. Sensory Threshold of 1,1,6-Trimethyl-1,2-Dihydronaphthalene (TDN) and Concentrations in Young Riesling and Non-Riesling Wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 2998–3004. [CrossRef]

- Vilanova de la Torre, M. del M.; Genisheva, Z.; Masa Vázquez, A.; Oliveira, J.M. Correlation between Volatile Composition and Sensory Properties in Spanish Albariño Wines. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Duan, S.; Zhao, L.; Gao, Z.; Luo, M.; Song, S.; Xu, W.; Zhang, C.; Ma, C.; Wang, S. Aroma Characterization Based on Aromatic Series Analysis in Table Grapes. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 31116. [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.-X.; Chi, M.; Song, C.-Z.; Liu, M.-Y.; Meng, J.-F.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Li, M.-H. Aroma Characterization of Cabernet Sauvignon Wine from the Plateau of Yunnan (China) with Different Altitudes Using SPME-GC/MS. International Journal of Food Properties 2015, 18, 1584–1596. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tao, Y.S.; Wen, Y.; Wang, H. Aroma Evaluation of Young Chinese Merlot Wines with Denomination of Origin. SAJEV 2016, 34. [CrossRef]

- Barbe, J.-C.; Garbay, J.; Tempère, S. The Sensory Space of Wines: From Concept to Evaluation and Description. A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 1424. [CrossRef]

- Souza Gonzaga, L.; Capone, D.L.; Bastian, S.E.P.; Jeffery, D.W. Defining Wine Typicity: Sensory Characterisation and Consumer Perspectives. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 2021, 27, 246–256. [CrossRef]

- Souza Gonzaga, L.; Capone, D.L.; Bastian, S.E.P.; Danner, L.; Jeffery, D.W. Using Content Analysis to Characterise the Sensory Typicity and Quality Judgements of Australian Cabernet Sauvignon Wines. Foods 2019, 8, 691. [CrossRef]

- ISO Sensory Analysis - Apparatus - Wine-Tasting Glass; 3591 (2); 1977.

- Jackson, R.S. Wine Tasting: A Professional Handbook; Third edition.; Elsevier/Academic Press is an imprint of Elservier: Amsterdam, 2017; ISBN 978-0-12-801813-2.

- Paradiso, V.M.; Sanarica, L.; Zara, I.; Pisarra, C.; Gambacorta, G.; Natrella, G.; Cardinale, M. Cultivar-Dependent Effects of Non-Saccharomyces Yeast Starter on the Oenological Properties of Wines Produced from Two Autochthonous Grape Cultivars in Southern Italy. Foods 2022, 11, 3373. [CrossRef]

- Zamora, F. Barrel Aging; Types of Wood. In Red Wine Technology; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 125–147 ISBN 978-0-12-814399-5.

- García, M.P.; González-Mendoza, L.A. Changes in Composition and Sensory Quality of Red Wine Aged in American and French Oak Barrels. OENO One 2001, 35, 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.; Kontoudakis, N.; Gómez-Alonso, S.; García-Romero, E.; Canals, J.M.; Hermosín-Gutíerrez, I.; Zamora, F. Influence of the Botanical Origin and Toasting Level on the Ellagitannin Content of Wines Aged in New and Used Oak Barrels. Food Research International 2016, 87, 197–203. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Xu, C. An Overview of the Perception and Mitigation of Astringency Associated with Phenolic Compounds. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2021, 20, 1036–1074. [CrossRef]

- del Álamo Sanza, M.; Nevares Domínguez, I.; García Merino, S. Influence of Different Aging Systems and Oak Woods on Aged Wine Color and Anthocyanin Composition. Eur Food Res Technol 2004, 219, 124–132. [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Liang, N.N.; Mu, L.; Pan, Q.H.; Wang, J.; Reeves, M.J.; Duan, C.Q. Anthocyanins and Their Variation in Red Wines II. Anthocyanin Derived Pigments and Their Color Evolution. Molecules 2012, 17, 1483–1519. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, C.; Tang, K.; Rao, Z.; Chen, J. Effects of Different Aging Methods on the Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Red Wine. Fermentation 2022, 8, 592. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, T.; Estrella, I.; Dueñas, M.; Fernández de Simón, B.; Cadahía, E. Influence of Wood Origin in the Polyphenolic Composition of a Spanish Red Wine Aging in Bottle, after Storage in Barrels of Spanish, French and American Oak Wood. Eur Food Res Technol 2007, 224, 695–705. [CrossRef]

- Maioli, F.; Picchi, M.; Guerrini, L.; Parenti, A.; Domizio, P.; Andrenelli, L.; Zanoni, B.; Canuti, V. Monitoring of Sangiovese Red Wine Chemical and Sensory Parameters along One-Year Aging in Different Tank Materials and Glass Bottle. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 221–239. [CrossRef]

- Picariello, L.; Gambuti, A.; Petracca, F.; Rinaldi, A.; Moio, L. Enological Tannins Affect Acetaldehyde Evolution, Colour Stability and Tannin Reactivity during Forced Oxidation of Red Wine. Int J Food Sci Technol 2018, 53, 228–236. [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; Varva, G.; De Gianni, A.; Viggiani, I.; Terracone, C.; Del Nobile, M.A. Influence of Type of Amphora on Physico-Chemical Properties and Antioxidant Capacity of ‘Falanghina’ White Wines. Food Chemistry 2014, 146, 226–233. [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; Mentana, A.; Quinto, M.; Centonze, D.; Longobardi, F.; Ventrella, A.; Agostiano, A.; Varva, G.; De Gianni, A.; Terracone, C.; et al. The Effect of In-Amphorae Aging on Oenological Parameters, Phenolic Profile and Volatile Composition of Minutolo White Wine. Food Research International 2015, 74, 294–305. [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; Varva, G. Evolution of Physico-Chemical and Sensory Characteristics of Minutolo White Wines during Aging in Amphorae: A Comparison with Stainless Steel Tanks. Lwt 2019, 103, 78–87. [CrossRef]

- Cameleyre, M.; Madrelle, V.; Lytra, G.; Barbe, J.-C. Impact of Whisky Lactone Diastereoisomers on Red Wine Fruity Aromatic Expression in Model Solution. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 10808–10814. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.C.; Capone, D.L.; van Leeuwen, K.A.; Elsey, G.M.; Sefton, M.A. Quantification of Several 4-Alkyl Substituted γ-Lactones in Australian Wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 348–352. [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.L.; Sacks, G.L.; Jeffery, D.W. Understanding Wine Chemistry; 1st ed.; Wiley, 2016; ISBN 978-1-118-62780-8.

- du Toit, W.J.; Marais, J.; Pretorius, I.S.; du Toit, M. Oxygen in Must and Wine: A Review. SAJEV 2017, 27. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Escudero, A.; Fernández, P.; Cacho, J.F. Changes in the Profile of Volatile Compounds in Wines Stored under Oxygen and Their Relationship with the Browning Process. Zeitschrift für Lebensmitteluntersuchung und -Forschung A 1997, 205, 392–396. [CrossRef]

- Wine Chemistry and Biochemistry; Moreno-Arribas, M.V., Polo, M.C., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2009; ISBN 978-0-387-74116-1.

- Noviello, M.; Paradiso, V.M.; Natrella, G.; Gambacorta, G.; Faccia, M.; Caponio, F. Application of Toasted Vine-Shoot Chips and Ultrasound Treatment in the Ageing of Primitivo Wine. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2024, 104, 106826. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Coello, M.S.; Díaz-Maroto, M.C. Volatile Compounds and Wine Aging. In Wine Chemistry and Biochemistry; Moreno-Arribas, M.V., Polo, M.C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2009; pp. 295–311 ISBN 978-0-387-74118-5.

- Cerdán, T.G.; Rodrı́guez Mozaz, S.; Ancı́n Azpilicueta, C. Volatile Composition of Aged Wine in Used Barrels of French Oak and of American Oak. Food Research International 2002, 35, 603–610. [CrossRef]

- Bacterial Fermentation Products. In Understanding Wine Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2016; pp. 230–238 ISBN 978-1-118-73072-0.

- Garde-Cerdán, T.; Ancín-Azpilicueta, C. Review of Quality Factors on Wine Ageing in Oak Barrels. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2006, 17, 438–447. [CrossRef]

- Pittari, E.; Moio, L.; Piombino, P. Interactions between Polyphenols and Volatile Compounds in Wine: A Literature Review on Physicochemical and Sensory Insights. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 1157. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M.; Marrufo-Curtido, A.; Carrascón, V.; Fernández-Zurbano, P.; Escudero, A.; Ferreira, V. Formation and Accumulation of Acetaldehyde and Strecker Aldehydes during Red Wine Oxidation. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 20. [CrossRef]

- Balboa-Lagunero, T.; Arroyo, T.; Cabellos, J.M.; Aznar, M. Sensory and Olfactometric Profiles of Red Wines after Natural and Forced Oxidation Processes. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2011, 62, 527–535. [CrossRef]

- Culleré, Laura; Cacho, J.; Ferreira, V. An Assessment of the Role Played by Some Oxidation-Related Aldehydes in Wine Aroma. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 876–881. [CrossRef]

- Mislata, A.M.; Puxeu, M.; Tomás, E.; Nart, E.; Ferrer-Gallego, R. Influence of the Oxidation in the Aromatic Composition and Sensory Profile of Rioja Red Aged Wines. Eur Food Res Technol 2020, 246, 1167–1181. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Prieto, L.J.; López-Roca, J.M.; Martínez-Cutillas, A.; Pardo-Mínguez, F.; Gómez-Plaza, E. Extraction and Formation Dynamic of Oak-Related Volatile Compounds from Different Volume Barrels to Wine and Their Behavior during Bottle Storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 5444–5449. [CrossRef]

- Dumitriu, G.-D.; Teodosiu, C.; Gabur, I.; Cotea, V.V.; Peinado, R.A.; López de Lerma, N. Evaluation of Aroma Compounds in the Process of Wine Ageing with Oak Chips. Foods 2019, 8, 662. [CrossRef]

- Genovese, A.; Piombino, P.; Lisanti, M.T.; Moio, L. Occurrence of Furaneol (4-Hydroxy-2,5-Dimethyl-3(2H)-Furanone) in Some Wines from Italian Native Grapes. Annali di Chimica 2005, 95, 415–419. [CrossRef]

- Delcros, L.; Collas, S.; Hervé, M.; Blondin, B.; Roland, A. Evolution of Markers Involved in the Fresh Mushroom Off-Flavor in Wine During Alcoholic Fermentation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 14687–14696. [CrossRef]

- Pons, A.; Lavigne, V.; Darriet, P.; Dubourdieu, D. Role of 3-Methyl-2,4-Nonanedione in the Flavor of Aged Red Wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 7373–7380. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.; Cholet, C.; Geny, L.; Darriet, P.; Landais, Y.; Pons, A. Identification and Analysis of New α- and β-Hydroxy Ketones Related to the Formation of 3-Methyl-2,4-Nonanedione in Musts and Red Wines. Food Chemistry 2020, 305, 125486. [CrossRef]

- Pons, A.; Lavigne, V.; Eric, F.; Darriet, P.; Dubourdieu, D. Identification of Volatile Compounds Responsible for Prune Aroma in Prematurely Aged Red Wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 5285–5290. [CrossRef]

- Ugliano, M. Oxygen Contribution to Wine Aroma Evolution during Bottle Aging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 6125–6136. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Aznar, M.; López, R.; Cacho, J. Quantitative Gas Chromatography−Olfactometry Carried out at Different Dilutions of an Extract. Key Differences in the Odor Profiles of Four High-Quality Spanish Aged Red Wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4818–4824. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Takase, H.; Tanzawa, F.; Kobayashi, H.; Saito, H.; Matsuo, H.; Takata, R. Identification of Furaneol Glucopyranoside, the Precursor of Strawberry-like Aroma, Furaneol, in Muscat Bailey A. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2015, 66, 91–94. [CrossRef]

- Kotseridis, Y.; Baumes, R.L.; Skouroumounis, G.K. Quantitative Determination of Free and Hydrolytically Liberated β-Damascenone in Red Grapes and Wines Using a Stable Isotope Dilution Assay. Journal of Chromatography A 1999, 849, 245–254. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, M.A.; Elsey, G.M.; Capone, D.L.; Perkins, M.V.; Sefton, M.A. Fate of Damascenone in Wine: The Role of SO2. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 8127–8131. [CrossRef]

- Sefton, M.A.; Skouroumounis, G.K.; Elsey, G.M.; Taylor, D.K. Occurrence, Sensory Impact, Formation, and Fate of Damascenone in Grapes, Wines, and Other Foods and Beverages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 9717–9746. [CrossRef]

- Loscos, N.; Hernández-Orte, P.; Cacho, J.; Ferreira, V. Evolution of the Aroma Composition of Wines Supplemented with Grape Flavour Precursors from Different Varietals during Accelerated Wine Ageing. Food Chemistry 2010, 120, 205–216. [CrossRef]

- Mendes-Pinto, M.M. Carotenoid Breakdown Products the—Norisoprenoids—in Wine Aroma. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2009, 483, 236–245. [CrossRef]

- Slaghenaufi, D.; Ugliano, M. Norisoprenoids, Sesquiterpenes and Terpenoids Content of Valpolicella Wines During Aging: Investigating Aroma Potential in Relationship to Evolution of Tobacco and Balsamic Aroma in Aged Wine. Frontiers in Chemistry 2018, 6, 66. [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, A.; Giuliani, N.; Dobrydnev, A.; Müller, N.; Volovenko, Y.; Rauhut, D.; Jung, R. Absorption of 1,1,6-Trimethyl-1,2-Dihydronaphthalene (TDN) from Wine by Bottle Closures. Eur Food Res Technol 2019, 245, 2343–2351. [CrossRef]

- Antal, E.; Varga, Z.; Kállay, M.; Steckl, S.; Bodor-Pesti, P.; Fazekas, I.; Sólyom-Leskó, A.; Kovács, B.Z.; Nagy, B.; Szövényi, Á.P.; et al. 1,1,6-Trimethyl-1,2-Dihydronaphthalene Content of Riesling Wines in Hungary. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 36677–36685. [CrossRef]

- Winterhalter, P.; Gök, R. TDN and β-Damascenone: Two Important Carotenoid Metabolites in Wine. In Carotenoid Cleavage Products; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society, 2013; Vol. 1134, pp. 125–137 ISBN 978-0-8412-2778-1.

- Lee, S.-H.; Seo, M.-J.; Riu, M.; Cotta, J.; Block, D.; Dokoozlian, N.; Ebeler, S. Vine Microclimate and Norisoprenoid Concentration in Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes and Wines. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2007, 58. [CrossRef]

- Marais, J.; Wyk, C. Carotenoid Levels in Maturing Grapes as Affected by Climatic Regions, Sunlight and Shade. South African Journal for Enology and Viticulture 1991, 12, 64–69. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, M.; Wegmann-Herr, P.; Schmarr, H.-G.; Gök, R.; Winterhalter, P.; Fischer, U. Impact of Rootstock, Clonal Selection, and Berry Size of Vitis Vinifera Sp. Riesling on the Formation of TDN, Vitispiranes, and Other Volatile Compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 3834–3849. [CrossRef]

- Capone, S.; Tufariello, M.; Siciliano, P. Analytical Characterisation of Negroamaro Red Wines by ”Aroma Wheels”. Food Chemistry 2013, 141, 2906–2915. [CrossRef]

- Coletta, A.; Toci, A.T.; Pati, S.; Ferrara, G.; Grieco, F.; Tufariello, M.; Crupi, P. Effect of Soil Management and Training System on Negroamaro Wine Aroma. Foods 2021, 10, 454. [CrossRef]

- Ferrero-del-Teso, S. New approaches for understanding the formation of mouthfeel properties in wines and grapes. Nuevas estrategias para comprender la formación de las sensaciones táctiles en boca de vinos y uvas 2022. [CrossRef]

| Name of the barrel | Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|

| Mix | Blend of French oak (Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl.), American oak (Q. alba L.), European oak (Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl.), acacia (Robinia pseudoacacia L.), lenga (Nothofagus pumilio (Poepp. & Endl.) Krasser) | Dried up to 48 months. Fine/extra fine grane |

| America oak | Q. alba L. | Air dried up to 48 months; fine grane; mature woods over 90 years old |

| French oak | Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl. | PEFC certification; dried up to 36 months; fine grane; mature woods over 180 years old, cultivated with the Haute Futaie technique (tall trunk) |

| European oak | Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl. | PEFC certification; fine grane; Air dried up to 48 months |

| French-European oak | Blend of French oak (Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl.), European oak (Q. petraea Q. petraea (Matt.) Liebl.). | Dried up to 48 months; fine/extra fine grane. |

| T-0 | p | Glass | Amphora | Mix | Fre-Eur oak | American oak | European oak | French oak | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP (U.A.) | 79.77 | 0.00 | 79.25±0.21e | 81.3±0.28cd | 80.83±0.60d | 84.3±0.46b | 82.13±0.06c | 84.7±0.20b | 86.3±0.00a |

| TA (U.A.) | 20.1 | 0.00 | 16.3±0.00d | 18.35±0.07b | 17.53±0.06c | 18.4±0.17b | 16.03±0.15d | 18.9±0.10a | 17.67±0.15c |

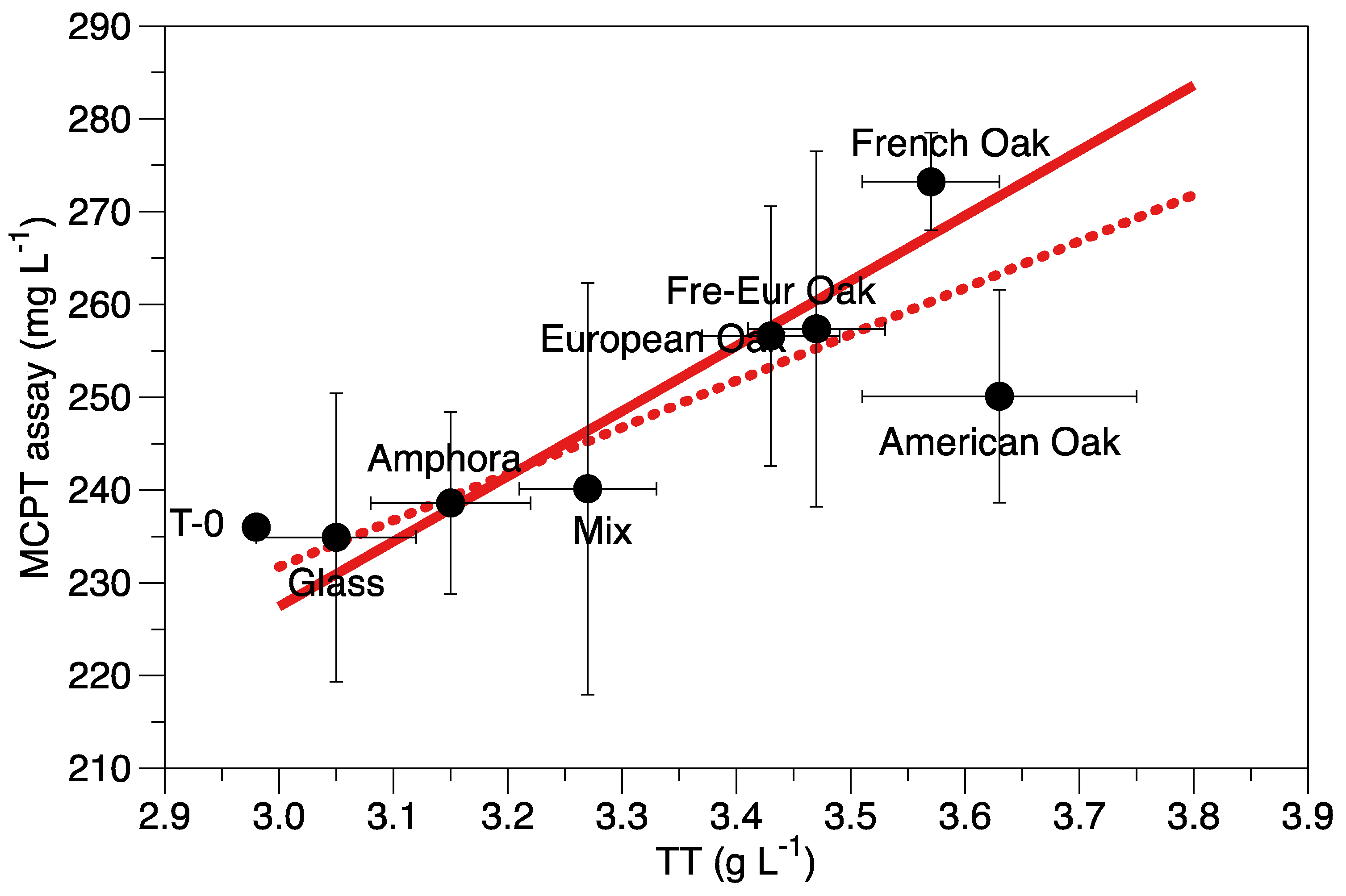

| TT (g*L-1) | 2.98 | 0.00 | 3.05±0.07c | 3.15±0.07c | 3.27±0.06bc | 3.43±0.06ab | 3.63±0.12a | 3.47±0.06ab | 3.57±0.06a |

| FA (U) | 13.5 | 0.00 | 9.2±0.00ab | 9.65±1.20ab | 9.1±0.1b | 10.13±0.06a | 5.43±0.06c | 10.23±0.12a | 8.67±0.06b |

| A-T (U) | 3.8 | 0.03 | 4.1±0.00c | 5.1±0.71b | 4.87±0.06b | 4.87±0.06b | 6.33±0.06a | 4.93±0.06b | 5.33±0.06b |

| free/cond A | 3.6 | 0.00 | 2.24±0.00a | 1.93±0.50ab | 1.87±0.04ab | 2.08±0.04a | 0.86±0.00c | 2.07±0.02a | 1.63±0.02b |

| MCPT (mg L-1) | 236 | 0.04 | 234.91±15.54a | 238.60±9.81a | 240.14±22.18a | 256.59±a | 250.11±11.46a | 257.37±19.14a | 273.24±5.28a |

| CD | 11.12 | 0.01 | 10.91±0.19b | 13.00±1.62a | 12.91±0.22a | 12.86±0.31ab | 13.82±0.42a | 12.67±0.37a | 12.89±0.41a |

| Hue | 0.84 | 0.00 | 0.86±0.01a | 0.80±0.04b | 0.80±0.00b | 0.79±0.01b | 0.76±0.03b | 0.80±0.00b | 0.79±0.01b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).