Submitted:

25 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Effect of the Storage Time in the Bottle on the Antioxidant Activities and Phenolic Content

2.2. Effect of the Storage Time in the Bottle on the Chromatic Characteristics of Aged WSs

2.3. Effect of the Storage Time in the Bottle on the Physicochemical Characteristics of Aged WSs

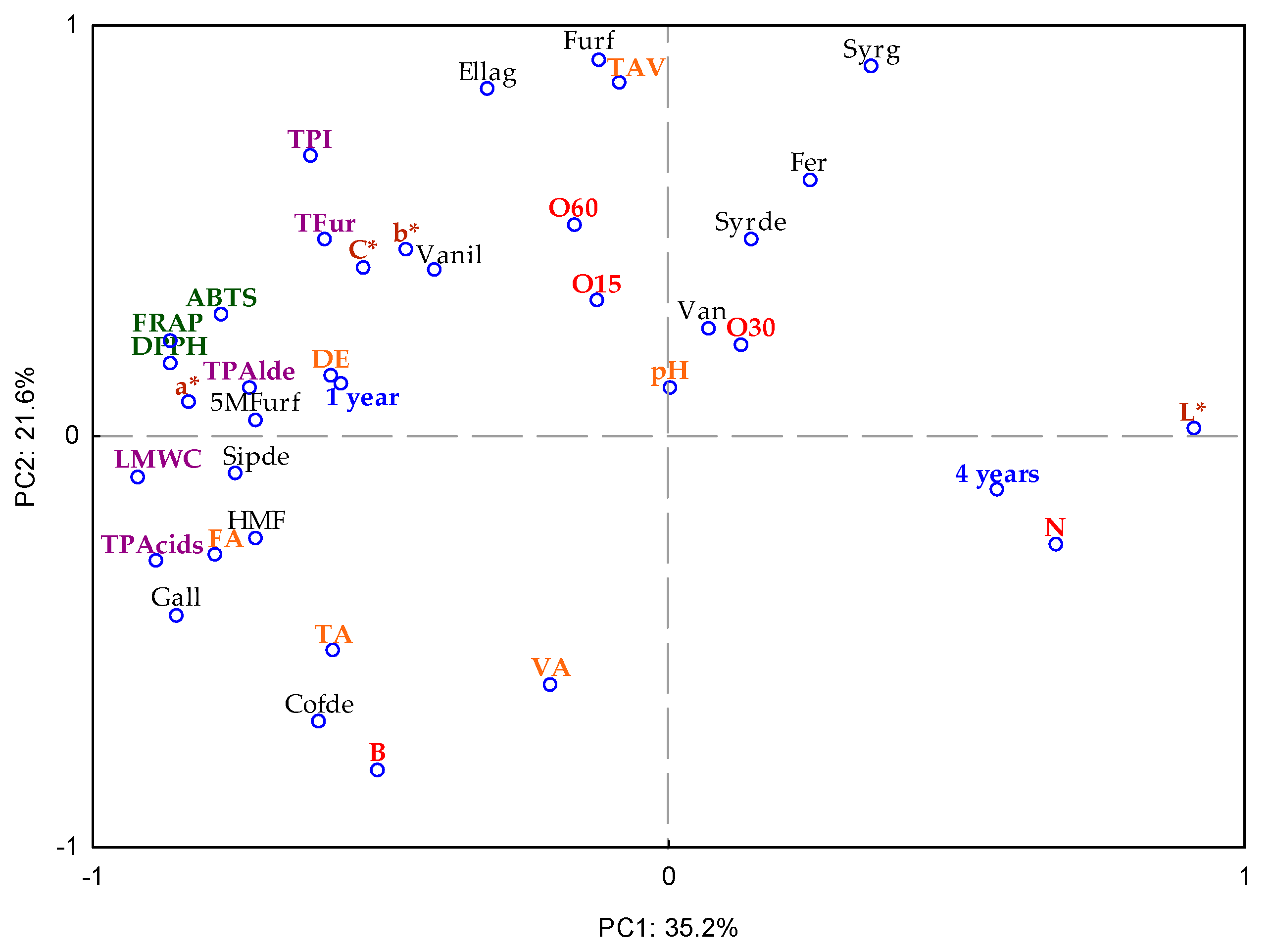

2.4. Multivariate Analysis

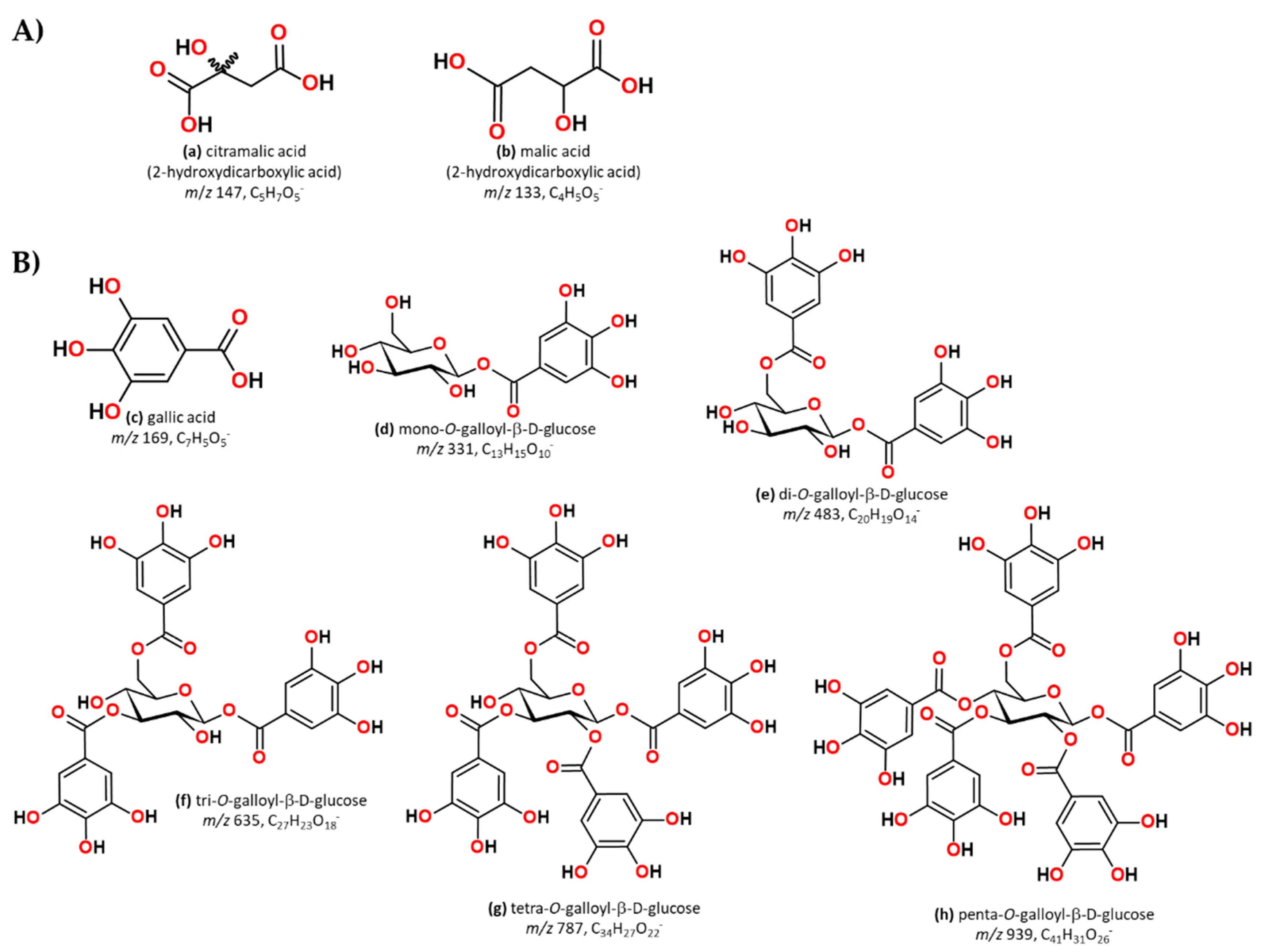

2.5. Phenolic Characterisation of the Four Years’ Bottle Storage

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemical and Reagents

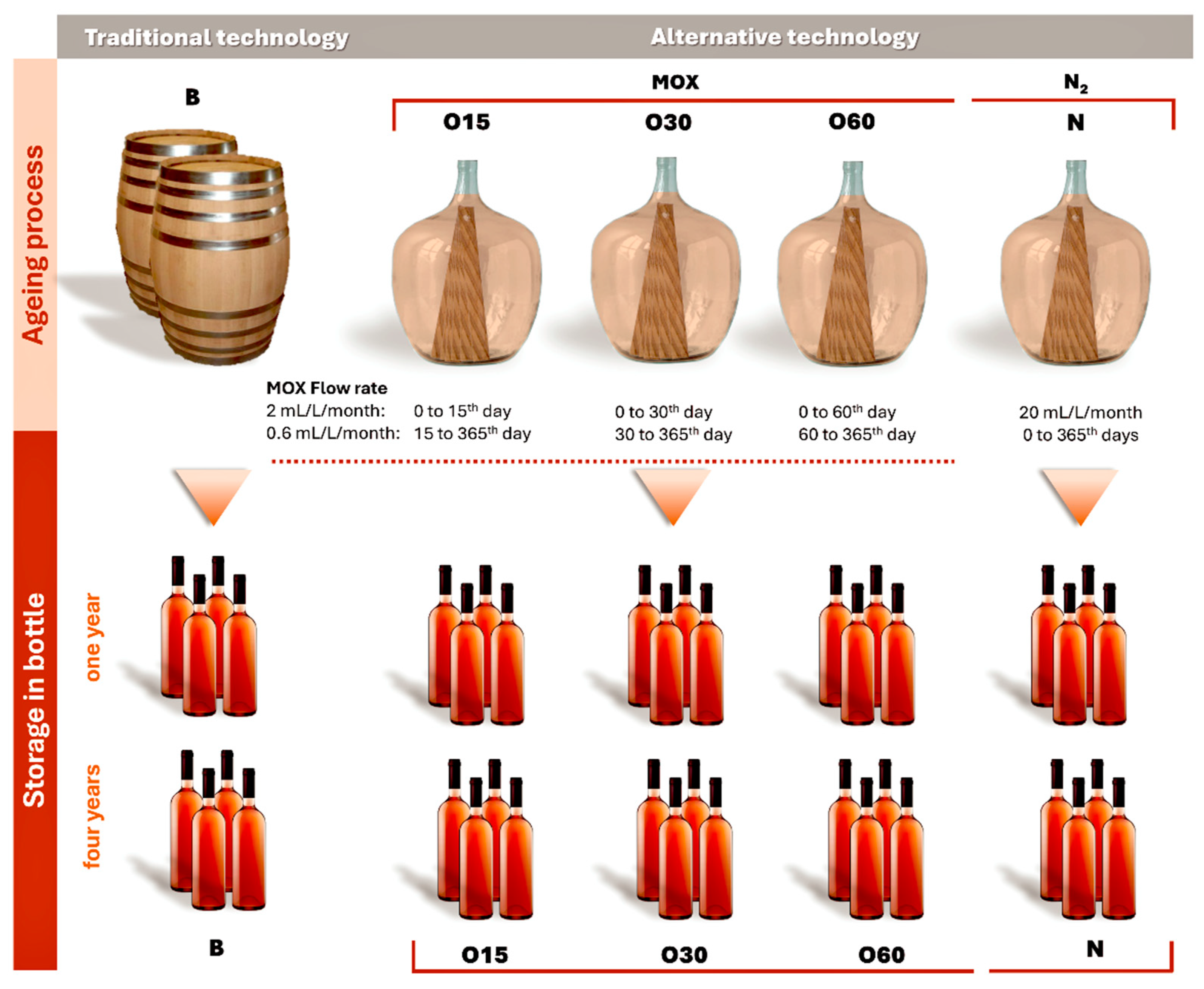

3.2. Experimental Design and Aged WSs Sampling

3.3. Chromatic Characteristics

3.4. Physicochemical Characteristics

3.5. Antioxidant Activity Analyses

3.5.1. ABTS Assay

3.5.2. DPPH Assay

3.5.3. FRAP Assay

3.6. Analyses of Low Molecular Weight Compounds

3.6.1. HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS Identification

3.6.2. Low Molecular Weight Composition Determination

3.7. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Amelio, S.; Mauri, M. Sustainable Strategies and Value Creation in the Food and Beverage Sector: The Case of Large Listed European Companies. Sustainability 2024, 16 (9798), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 09 December 2024).

- Aschemann-Witzel, J. V., P.; Peschel, A.O. Consumers’ categorization of food ingredients: Do consumers perceive them as ‘clean label’ producers expect? An exploration with projective mapping. Food Quality and Preference 2019, 71, 117-128. [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustain Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [CrossRef]

- Canas, S.; Caldeira, I.; Fernandes, T. A.; Anjos, O.; Belchior, A. P.; Catarino, S. Sustainable use of wood in wine spirit production. In Improving Sustainable Viticulture and Winemaking Practices; Costa, J.M., Catarino, S., Escalona, J.M., Piergiorgio, C., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2022; pp. 259–280. [CrossRef]

- 100% sustainable from #Farm2Glass: The European spirits sector & the green deal. Available online: https://spirits.eu/issues/sustainable-from-farm2glass/introduction-8 (accessed on 09 December 2024).

- Canas, S.; Caldeira, I.; Anjos, O.; Belchior, A. P. Phenolic profile and colour acquired by the wine spirit in the beginning of ageing: Alternative technology using micro-oxygenation vs traditional technology. LWT 2019, 111, 260–269. [CrossRef]

- Nocera, A.; Ricardo-Da-Silva, J. M.; Canas, S. Antioxidant activity and phenolic composition of wine spirit resulting from an alternative ageing technology using micro-oxygenation: A preliminary study. Oeno One 2020, 54, 485–496. [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, I.; Anjos, O.; Portal, V.; Belchior, A. P.; Canas, S. Sensory and chemical modifications of wine-brandy aged with chestnut and oak wood fragments in comparison to wooden barrels. Analytica Chimica Acta 2010, 660 (1-2), 43-52. [CrossRef]

- Canas, S. Phenolic Composition and Related Properties of Aged Wine Spirits: Influence of Barrel Characteristics. A Review. Beverages 2017, 3 (55), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Cernîşev, S. Analysis of lignin-derived phenolic compounds and their transformations in aged wine distillates. Food Control 2017, 73 (Part B), 281-290. [CrossRef]

- Granja-Soares, J.; Roque, R.; Cabrita, M.J.; Anjos, O.; Belchior, A.P.; Caldeira, I.; Canas, S. Effect of innovative technology using staves and micro-oxygenation on the sensory and odorant profile of aged wine spirit. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127450. [CrossRef]

- Reg. EU nº 2019/787 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on the Definition, Description, Presentation and Labelling of Spirit Drinks, the Use of the Names of Spirit Drinks in the Presentation and Labelling of other Foodstuffs, the Protection of Geographical Indications for Spirit Drinks, the Use of Ethyl Alcohol and Distillates of Agricultural Origin in Alcoholic Beverages, and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 110/2008; OJEU. L130 European Union. 2019, pp. 1–54. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/787/2022-08-15 (accessed on 03 December 2024).

- Caldeira, I.; Vitória, C.; Anjos, O.; Fernandes, T. A.; Gallardo, E.; Fargeton, L.; Boissier, B.; Catarino, S.; Canas, S. Wine spirit ageing with chestnut staves under different micro-oxygenation strategies: Effects on the volatile compounds and sensory profile. Applied Sciences 2021, 11 (3991), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Canas, S.; Danalache, F.; Anjos, O.; Fernandes, T. A.; Caldeira, I.; Santos, N.; Fargeton, L.; Boissier, B.; Catarino, S. Behaviour of Low Molecular Weight Compounds, Iron and Copper of Wine Spirit Aged with Chestnut Staves under Different Levels of Micro-Oxygenation. Molecules 2020, 25, 5266. [CrossRef]

- Canas, S.; Anjos, O.; Caldeira, I.; Fernandes, T. A.; Santos, N.; Lourenço, S.; Granja-Soares, J.; Fargeton, L.; Boissier, B.; Catarino, S. Micro-oxygenation level as a key to explain the variation in the colour and chemical composition of wine spirits aged with chestnut wood staves. LWT 2022, 154, 112658. [CrossRef]

- Krstić, J. D.; M.M., K.-S.; Veljović, S. P. Traditional and Innovative Aging Technologies of distilled Beverages: The Influence on the Quality and Consumer Preferences of Aged Spirit Drinks. Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2021, 66 (3), 209-230. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Alves, S.; Lourenço, S.; Anjos, O.; Fernandes, T. A.; Caldeira, I.; Catarino, S.; Canas, S. Influence of the Storage in Bottle on the Antioxidant Activities and Related Chemical Characteristics of Wine Spirits Aged with Chestnut Staves and Micro-Oxygenation. Molecules 2022, 27 (106), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Mercanti, N.; Macaluso, M.; Pieracci, Y.; Brazzarola, F.; Palla, F.; Verdini, P. G.; Zinnai, A. Enhancing wine shelf-life: Insights into factors influencing oxidation and preservation. Heliyon 2024, 10 (e35688), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Echave, J.; Barral, M.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Prieto, M. A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Bottle Aging and Storage of Wines: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26 (3), 713. 10.3390/molecules26030713.

- Hart, A.; Kleinig, A. The role of oxygen in the aging of bottled wine. Australian and New Zealand Wine Industry Journal 2005, 20 (2), 46–50. https://www.vawa.net/articles/ACF_Paper.pdf.

- Anli, R.E.; Cavuldak, Özge A. A review of microoxygenation application in wine. J. Inst. Brew. 2012, 118, 368–385. [CrossRef]

- Anjos, O.; Comesaña, M. M.; Caldeira, I.; Pedro, S. I.; Oller, P. E.; Canas, S. Application of Functional Data Analysis and FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy to Discriminate Wine Spirits Ageing Technologies. Mathematics 2020, 8, 896. [CrossRef]

- Vacca, V.; Piga, A.; Del Caro, A.; Fenu, P. A. M.; Agabbio, M. Changes in phenolic compounds, colour and antioxidant activity in industrial red myrtle liqueurs during storage. Nahrung/Food 2003, 47 (6), 442 – 447. [CrossRef]

- Karabegović, I. T.; Vukosavljević, P.; Novaković, M. M.; Gorjanović, S.; Dzamić, A. M.; Lazić, M. L. Influence of the storage on bioactive compounds and sensory attributes of herbal liqueur. Digest Journal of Nanomaterials and Biostructures 2012, 7 (4), 1587-1598. https://www.academia.edu/110113169/Influence_of_the_storage_on_bioactive_compounds_and_sensory_attributes_of_herbal_liqueur?uc-sb-sw=2227721.

- Espejo, F.; Armada, S. Colour Changes in Brandy Spirits Induced by Light-Emitting Diode Irradiation and Different Temperature Levels. Food Bioprocess Technol 2014, 7, 2595–2609. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T. A.; Antunes, A. M. M.; Caldeira, I.; Anjos, O.; Freitas, V.; Fargeton, L.; Boissier, B.; Catarino, S.; Canas, S. Identification of gallotannins and ellagitannins in aged wine spirits: A new perspective using alternative ageing technology and high-resolution mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry 2022, 382 (132322), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Pérez, M.D.; Muñiz, P.; González-Sanjosé, M.L. Antioxidant Profile of Red Wines Evaluated by Total Antioxidant Capacity, Scavenger Activity, and Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress Methodologies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 5476–5483. [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, I. G.; Apetrei, C., Munteanu IG, Apetrei C. Analytical Methods Used in Determining Antioxidant Activity: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021, 22 (7), 3380. [CrossRef]

- Bondet, V.; Brand-Williams, W.; Berset, C. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Antioxidant Activity using the DPPH. Free Radical Method. LWT 1997, 30(6), 609–615. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Prior, R. L. The Chemistry behind Antioxidant Capacity Assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1841–1856. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.; Ojha, H.; Chaudhury, N. K. Estimation of antiradical properties of antioxidants using DPPH assay: A critical review and results. Food Chem. 2012, 130, 1036–1043. [CrossRef]

- Da Porto, C.; Calligaris, S.; Celotti, E.; Nicoli, M.C. Antiradical properties of commercial cognacs assessed by the DPPH(.) test. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 4241–4245. [CrossRef]

- Koga, K.; Taguchi, A.; Koshimizu, S.; Suwa, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Shirasaka, N.; Yoshizumi, H. Reactive Oxygen Scavenging Activity of Matured Whiskey and Its Active Polyphenols. Journal of Fodd Science 2007, 72 (3), 212-217. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, M.; Rodríguez, M. C.; Martínez, C.; Bosquet, V.; Guillén, D.; Barroso, C. G. Antioxidant activity of Brandy de Jerez and other aged distillates, and correlation with their polyphenolic content. Food Chemistry 2009, 116 (1), 29–33. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Duchnik, W.; Muzykiewicz-Szymańska, A.; Kucharski, Ł.; Zielonka-Brzezicka, J.; Nowak, A.; Klimowicz, A. The Changes of Antioxidant Activity of Three Varieties of ‘Nalewka’, a Traditional Polish Fruit Alcoholic Beverage during Long-Term Storage. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1114. [CrossRef]

- De Beer, D.; Joubert, E.; Gelderblom, W. C. A.; Manley, M. Changes in the phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of pinotage, cabernet sauvignon, chardonnay and chenin blanc wines during bottle ageing. South African Journal of Enology & Viticulture 2005, 26 (2), 6-15. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A. M.; Castro, R.; Rodrı́guez, M. C.; D.A., G.; Barroso, C. G. Study of the antioxidant power of brandies and vinegars derived from Sherry wines and correlation with their content in polyphenols. Food Research International 2004, 37, 715–721. [CrossRef]

- Mrvčić, J.; Posavec, S.; Kazazic, S.; Stanzer, D.; Peša, A.; Stehlik-Tomas, V. Spirit drinks: A source of dietary polyphenols. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 4, 102–111. https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/146658.

- Priyadarsini, K. I.; Khopde, S. M.; Kumar, S. S.; Mohan, H. Free Radical Studies of Ellagic Acid, a Natural Phenolic Antioxidant. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2002, 50 (7), 2200–2206. [CrossRef]

- Molski, M. Theoretical study on the radical scavenging activity of gallic acid. Heliyon 2023, 9 (1), e12806. [CrossRef]

- Gangadharan, G.; Gupta, S.; Kudipady, M. L.; Puttaiahgowda, Y. M. Gallic Acid Based Polymers for Food Preservation: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 37530-37547. [CrossRef]

- Roussey, C.; Colin, J.; Teissier du Cros, R.; Casalinho, J.; Perré, P. In-Situ Monitoring of Wine Volume, Barrel Mass, Ullage Pressure and Dissolved Oxygen for a Better Understanding of Wine-Barrel-Cellar Interactions. J. Food Eng. 2021, 291 (110233), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Castellari, M.; Matricardi, L.; Arfelli, G.; Galassi, S.; Amati, A. Level of single bioactive phenolics in red wine as a function of the oxygen supplied during storage. Food Chemistry 2000, 69 (1), 61-67. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C. M.; Ferreira, A. C. S.; Freitas, V.; Silva, A. M. S. Oxidation mechanisms occurring in wines. Food Research International 2011, 44 (5). [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, S.; Anjos, O.; Caldeira, I.; Alves, S. O.; Santos, N.; Canas, S. Natural Blending as a Novel Technology for the Production Process of Aged Wine Spirits: Potential Impact on Their Quality. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12 (10055), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Canas, S.; Casanova, V.; Belchior, A. P. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of Portuguese wine aged brandies. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2008, 21 (8), 626–633. [CrossRef]

- Silvello, G. C.; Bortoletto, A. M.; Castro, M. C.; Alcarde, A. R. New approach for barrel-aged distillates classification based on maturation level and machine learning: A study of cachaça. LWT 2021, 140 (110836). [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, I.; Sousa, R. B.; Belchior, A. P.; Clímaco, M. C. A sensory and chemical approach to the aroma of wooden aged Lourinhã wine brandy. Ciência Téc. Vitiv. 2008, 23 (2), 97-110. https://www.ctv-jve-journal.org/articles/ctv/ref/2017/01/ctv20173201p12/ctv20173201p12.html.

- Le Floch, A.; Jourdes, M.; Teissedre, P.-L. Polysaccharides and lignin from oak wood used in cooperage: Composition, interest, assays: A review. Carbohydrate Research 2015, 417, 94–102. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N. K.; Fukuoka, A.; Nakajima, K. Metal-Free and Selective Oxidation of Furfural to Furoic Acid with an N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalyst. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 3434–3442. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Prieto, L. J.; López-Roca, J. M.; Martínez-Cutillas, A.; Pardo-Mínguez, F.; Gómez-Plaza, E. Extraction and Formation Dynamic of Oak-Related Volatile Compounds from Different Volume Barrels to Wine and Their Behavior during Bottle Storage. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2003, 51 (18), 5444–5449. [CrossRef]

- Sarni, F.; Moutounet, M.; Puech, J.-L.; Rabier, P. Effect of heat treatment of oak wood extractable compounds. Holzforschung 1990, 44, 461–466. [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, I.; Belchior, A. P.; Climaco, M. C.; de Sousa, R. B. Aroma profile of Portuguese brandies aged in chestnut and oak woods. Analytica Chimica Acta 2002, 458 (1), 55–62. [CrossRef]

- Giménez Martínez, R.; De La Serrana, H. L. G.; Villalón Mir, M.; Alarcón, M. N.; Herrera, M. O.; Vique, C. C.; Martínez, M. C. L. Study of Vanillin, Syringaldehyde and Gallic Acid Content in Oak Wood and Wine Spirit Mixtures: Influence of Heat Treatment and Chip Size. Journal of Wine Research 2001, 12 (3), 175–182. [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, M.; Rodrigues, F.; Perestrelo, R.; Marques, J. C.; Camara, J. S. Comparison of two extraction methods for evaluation of volatile constituents patterns in commercial whiskeys elucidation of the main odour-active compounds. Talanta 2007, 74 (1), 78–90. [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, O. Y.; Brink, D. P.; Prothmann, J.; Ravi, K.; Sun, M.; García-Hidalgo, J.; Sandahl, M.; Hulteberg, C. P.; Turner, C.; Lidén, G.; Gorwa-Grauslund, M. F. Biological valorization of low molecular weight lignin. Biotechnology Advances 2016, 34 (8), 1318-1346. [CrossRef]

- Bianco, M.-A.; Handaji, A.; Savolainen, H. Quantitative analysis of ellagic acid in hardwood samples. Science of The Total Environment 1998, 222 (1-2), 123-126. [CrossRef]

- Hernanz, D.; Gallo, V.; A.F., R.; Meléndez-Martínez, A. J.; M.L., G.-M.; Heredia, F. J. Effect of storage on the phenolic content, volatile composition and colour of white wines from the varieties Zalema and Colombard. Food Chemistry 2009, 113 (2), 530–537. [CrossRef]

- Burin, V. M.; Costa, L. L. F.; Rosier, J. P.; Bordignon-Luiz, M. T. Cabernet Sauvignon wines from two different clones, characterization and evolution during bottle ageing. LWT 2011, 44, 1931–1938. [CrossRef]

- García-Falcón, M. S.; Pérez-Lamela, C.; Martínez-Carballo, E.; Simal-Gándara, J. Determination of phenolic compounds in wines: Influence of bottle storage of young red wines on their evolution. Food Chemistry 2007, 105 (1), 248–259. [CrossRef]

- Vico, T. A.; Arce, V. B.; Fangio, M. F.; Gende, L. B.; Bertran, C. A.; Mártire, D. O.; Churio, M. S. Two choices for the functionalization of silica nanoparticles with gallic acid: characterization of the nanomaterials and their antimicrobial activity against Paenibacillus larvae. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2016, 18 (11), 348. [CrossRef]

- Severino, J. F.; Goodman, B. A.; Kay, C. W. M.; Stolze, K.; Tunega, D.; Reichenauer, T. G.; Pirker, K. F. Free radicals generated during oxidation of green tea polyphenols: Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy combined with density functional theory calculations. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 2009, 46, 1076–1088. [CrossRef]

- Badhani, B.; Sharma, N.; Kakkar, R. Gallic acid: a versatile antioxidant with promising therapeutic and industrial applications. RSC Adv. 2015, 5 (35), 27540–27557. [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V. L. Oxygen with phenols and related reactions in musts, wines, and model systems: Observations and practical implications. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1987, 38, 69-77. [CrossRef]

- Tulyathan, V.; Boulton, R. B.; Singleton, V. L. Oxygen uptake by gallic acid as a model for similar reactions in wines. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1989, 37 (4), 844–849. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Vincken, J.-P.; van Zadelhoff, A.; Hilgers, R.; Lin, Z.; de Bruijn, W. J. C. Presence of free gallic acid and gallate moieties reduces auto-oxidative browning of epicatechin (EC) and epicatechin gallate (ECg). Food Chemistry 2023, 425, 136446. [CrossRef]

- Galato, D.; Ckless, K.; Susin, M. F.; Giacomelli, C.; Ribeiro-do-Valle, R. M.; Spinelli, A. Antioxidant capacity of phenolic and related compounds: correlation among electrochemical, visible spectroscopy methods and structure–antioxidant activity. Redox Report 2001, 6 (4), 243-250. [CrossRef]

- Guiberteau-Cabanillas, A.; Godoy-Cancho, B.; Bernalte, E.; Tena-Villares, M.; Guiberteau Cabanillas, C.; Martínez-Cañas, M. A. Electroanalytical Behavior of Gallic and Ellagic Acid Using Graphene Modified Screen-Printed Electrodes. Method for the Determination of Total Low Oxidation Potential Phenolic Compounds Content in Cork Boiling Waters. Electroanalysis 2015, 27 (1), 177–184. [CrossRef]

- Palafox-Carlos, H.; Gil-Chávez, J.; Sotelo-Mundo, R. R.; Namiesnik, J.; Gorinstein, S.; González-Aguilar, G. A. Antioxidant Interactions between Major Phenolic Compounds Found in ‘Ataulfo’ Mango Pulp: Chlorogenic, Gallic, Protocatechuic and Vanillic Acids. Molecules 2012, 17, 12657-12664. [CrossRef]

- Malinda, K.; Sutanto, H.; Darmawan, A. Characterization and antioxidant activity of gallic acid derivative. 3rd International Symposium on Applied Chemistry, Published by AIP Publishing in Jakarta, Indonesia 2017, 1904, 020030-1–020030-7. [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C. A.; Miller, N. J.; Paganga, G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 1996, 20 (7), 933–956. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. X.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, R.; Marcone, M. F.; Li, X.; Tsao, R. 5-Hydroxymethyl-2-furfural and Derivatives Formed during Acid Hydrolysis of Conjugated and Bound Phenolics in Plant Foods and the Effects on Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Capacity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2014, 62 (20), 4754–4761. [CrossRef]

- Potapovich, M. V.; Kurchenko, V. P.; Metelitza, D. I.; Shadyro, O. I. Antioxidant activity of oxygen-containing aromatic compounds. Appl Biochem Microbiol 2011, 47, 346–355. [CrossRef]

- Coldea, T. E.; Socaciu, C.; Mudura, E.; Socaci, S. A.; Ranga, F.; Pop, C. R.; Pasqualone, A. Volatile and phenolic profiles of traditional Romanian apple brandy after rapid ageing with different wood chips. Food Chemistry 2020, 320, 126643. [CrossRef]

- Pathare, P. B.; Opara, U. L.; Al-Said, F. A. J. Colour Measurement and Analysis in Fresh and Processed Foods: A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol 2013, 6, 36–60. [CrossRef]

- Macdougall, D. B. Colour measurement of food: principles and practice. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles, Colour Measurement; Gulrajani, M.L. Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, Cambridge, 2010, pp.312-342. [CrossRef]

- Granato, D.; Masson, M. L. Instrumental color and sensory acceptance of soy-based emulsions: a response surface approach. Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos 2010, 30 (4), 1090- 1096. [CrossRef]

- Fujieda, M.; Tanaka, T.; Suwa, Y.; Koshimizu, S.; Kouno, I. Isolation and Structure of Whiskey Polyphenols Produced by Oxidation of Oak Wood Ellagitannins. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2008, 56 (16), 7305–7310. [CrossRef]

- Karbowiak, T.; Crouvisier-Urion, K.; Lagorce, A.; Ballester, J.; Geoffroy, A.; Roullier-Gall, C.; Chanut, J.; Gougeon, R. D.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Bellat, J.-P. Wine aging: A bottleneck story. NPJ Sci. Food 2019, 3, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Belchior, A.; Caldeira, I.; Costa, S.; Lopes, C.; Tralhão, G.; Ferrao, A.; Mateus, A. M.; Carvalho, E. Evolução das características físico-químicas e organolépticas de aguardentes Lourinhã ao longo de cinco anos de envelhecimento em madeiras de carvalho e de castanheiro. Ciência e Técnica Vitivinícola 2001, 16 (2), 81–95. https://www.ctv-jve-journal.org/articles/ctv/ref/2021/01/ctv20213601p55/ctv20213601p55.html.

- Anjos, O.; Caldeira, I.; Pedro, S. I.; Canas, S. FT-Raman methodology applied to identify different ageing stages of wine spirits. LWT Food Science and Technology 2020, 134 (110179), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-Q.; Pilone, G. J. An overview of formation and roles of acetaldehyde in winemaking with emphasis on microbiological implications. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2000, 35 (1), 49–61. [CrossRef]

- Nose, A.; Hojo, M.; Suzuki, M.; Ueda, T. Solute Effects on the Interaction between Water and Ethanol in Aged Whiskey. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2004, 52 (17), 5359–5365. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z. J.; Zeng, Y. H.; Sun, Q. Y.; Zhang, W. H.; Wang, S. T.; Shen, C. H.; Shi, B. Insights into the mechanism of flavor compound changes in strong flavor baijiu during storage by using the density functional theory and molecular dynamics simulation. Food Chemistry 2022, 373 (131522). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chang, S. K. C.; J. Stringer, S. J.; Zhang, Y. Characterization of Titratable Acids, Phenolic Compounds, and Antioxidant Activities of Wines Made from Eight Mississippi-Grown Muscadine Varieties during Fermentation. LWT 2017, 86 (21), 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Sun, T. Changes of enological variables, metal ions, and aromas in Fenjiu during 3 years of ceramic and glass bottle ageing. CyTA - Journal of Food 2015, 13 (3), 366-372. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Reidah, I. M.; Contreras, M. M.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Reversed-phase ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization-quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry as a powerful tool for metabolic profiling of vegetables: Lactuca sativa as an example of its application. Journal of Chromatography A 2013, 1313, 212–227. [CrossRef]

- Papetti, A.; Maietta, M.; Corana, F.; Marrubini, G.; Gazzani, G. Polyphenolic profile of green/red spotted Italian Cichorium intybus salads by RP-HPLC-PDA-ESI-MSn. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2017, 1-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2017.08.010.

- Oliveira-Alves, S. C.; Andrade, F.; Prazeres, I.; Silva, A.; Capelo, J.; Duarte, B.; Caçador, I.; Coelho, J.; Serra, A.; Bronze, M. Impact of Drying Processes on the Nutritional Composition, Volatile Profile, Phytochemical Content and Bioactivity of Salicornia ramosissima J. Woods. Antioxidants 2021, 10 (8), 1312. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/antiox10081312.

- Meyers, K. J.; Swiecki, T. J.; Mitchell, A. E. Understanding the Native Californian Diet: Identification of Condensed and Hydrolyzable Tannins in Tanoak Acorns (Lithocarpus densiflorus). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2006, 54 (20), 7686–7691. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf061264t.

- Oliveira-Alves, S. C.; Pereira, R. S.; Pereira, A. B.; Ferreira, A.; Mecha, E.; Silva, A. B.; Serra, A. T.; Bronze, M. R. Identification of functional compounds in baru (Dipteryx alata Vog.) nuts: Nutritional value, volatile and phenolic composition, antioxidant activity and antiproliferative effect. Food Research International 2020, 131 (109026). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109026.

- Soong, Y. Y.; Barlow, P. J. Isolation and structure elucidation of phenolic compounds from longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) seed by high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A 2005, 1085 (2), 270–277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2005.06.042.

- Regalado, E. L.; Tolle, S.; Pino, J. A.; Winterhalter, P.; Menendez, R.; A.R., M.; Rodríguez, J. L. Isolation and identification of phenolic compounds from rum aged in oak barrels by high-speed countercurrent chromatography/high-performance liquid chromatography-diode array detection-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry and screening for antioxidant activity. Journal of Chromatography A 2011, 1218 (41), 7358–7364. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2011.08.068.

- Sanz, M.; Cadahía, E.; Esteruelas, E.; A.M., M.; Fernández de Simón, B.; Hernández, T.; Estrella, I. Phenolic compounds in chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) heartwood. Effect of toasting at cooperage. J Agric Food Chem. 2010, 58 (17), 9631-9640. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jf102718t.

- Flamini, R.; Panighel, A.; De Marchi, F. Mass spectrometry in the study of wood compounds released in the barrel-aged wine and spirits. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 2023, 42 (4), 1174-1220. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wei, J.; Huo, Z.; Ji, W. Simultaneous detection of furfural, 5-methylfurfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in tsamba, roasted highland barley flour, by UPLC–MS/MS Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2023, 116 (105095). [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, M.; Weber, F.; Durán-Guerrero, E.; Castro, R.; Rodríguez-Dodero, M. d. C.; García Moreno, M. V.; Winterhalter, P.; Guillén-Sánchez, D. HPLC-DAD-MS and Antioxidant Profile of Fractions from Amontillado Sherry Wine Obtained Using High-Speed Counter Current Chromatography. Foods 2021, 10 (131). [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Alves, S. C.; Vendramini-Costa, D. B.; Cazarin, C. B. B.; Maróstica Júnior, M. R.; Ferreira, J. P. B.; Silva, A. B.; Prado, M. A.; Bronze, M. R. Characterization of phenolic compounds in chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seeds, fiber flour and oil. Food Chemistry 2017, 232, 295-305. [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, A. K.; Gu, L. Antioxidant Capacity, Phenolic Content, and Profiling of Phenolic Compounds in the Seeds, Skin, and Pulp of Vitis rotundifolia (Muscadine Grapes) As Determined by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2010, 58 (8), 4681–4692. [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; de Simón, B. F.; Esteruelas, E.; Muñoz, A. M.; Cadahía, E.; Hernández, M. T.; Estrella, I.; Martinez, J. Polyphenols in red wine aged in acacia (Robinia pseudoacacia) and oak (Quercus petraea) wood barrels. Analytica Chimica Acta 2012, 732, 83-90. [CrossRef]

- Patyra, A.; Dudek, M. K.; Kiss, A. K. LC-DAD–ESI-MS/MS and NMR Analysis of Conifer Wood Specialized Metabolites. Cells 2022, 11, 3332. [CrossRef]

- Khatib, M.; Campo, M.; Bellumori, M.; Cecchi, L.; Vignolini, P.; Innocenti, M.; Mulinacci, N. Tannins from Different Parts of the Chestnut Trunk (Castanea Sativa Mill.): a Green and Effective Extraction Method and Their Profiling by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Diode Array Detector-Mass Spectrometry. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 3 (11), 1903-1912. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Soares, B.; Dias, C. B.; Freitas, A. M. C.; Cabrita, M. J. Phenolic and Furanic Compounds of Portuguese Chestnut and French, American and Portuguese Oak Wood Chips. European Food Research and Technology 235(235):457-467 2012, 235, 457-467. [CrossRef]

- Wyrepkowski, C. C.; Gomes da Costa, D. L. M.; Sinhorin, A. P.; Vilegas, W.; De Grandis, R. A.; Resende, F. A.; Varanda, E. A.; Dos Santos, L. C. Characterization and Quantification of the Compounds of the Ethanolic Extract from Caesalpinia ferrea Stem Bark and Evaluation of Their Mutagenic Activity. Molecules 2014, 19, 16039-16057. [CrossRef]

- De Rosso, M.; Panighel, A.; Dalla Vedova, A.; Stella, L.; Flamini, R. Changes in Chemical Composition of a Red Wine Aged in Acacia, Cherry, Chestnut, Mulberry, and Oak Wood Barrels. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2009, 57 (5), 1915–1920. [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Simón, B.; Sanz, M.; Cadahía, E.; Martínez, J.; Esteruelas, E.; Muñoz, A. M. Polyphenolic compounds as chemical markers of wine ageing in contact with cherry, chestnut, false acacia, ash and oak wood. Food Chemistry 2014, 143, 66-76. [CrossRef]

- Sádecká, J.; Májek, P.; Tóthová, J. CE Profiling of Organic Acids in Distilled Alcohol Beverages Using Pattern Recognition Analysis. Chroma 2008, 67 (1), 69–74. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. J.; Kim, K. R.; Kim, J. H. Gas Chromatographic Organic Acid Profiling Analysis of Brandies and Whiskeys for Pattern Recognition Analysis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1999, 47 (6), 2322–2326. [CrossRef]

- Crozier, A.; Jaganath, I. B.; Clifford, M. N. Dietary phenolics: chemistry, bioavailability and effects on health. Nat. Prod. 2009, 26, 1001– 1043. [CrossRef]

- Namkung, W.; Thiagarajah, J. R.; Phuan, P. W.; Verkman, A. S. Inhibition of Ca2+-activated Cl- channels by gallotannins as a possible molecular basis for health benefits of red wine and green tea. FASEB J. 2010, 24 (11), 4178-4186. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. A.; Klebanoff, L. E.; Morrow, C. T.; Sandel, B. B. 3-Substituted Flavones. 1. Reduction of and Conjugate Addition to (E)-2-Methoxy-3- (carbethoxymethy1ene) flavones. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 1982, 47 (9), 1702–1706. [CrossRef]

- OIV. Compendium of International Methods of Analysis of Spirituous Beverages of Vitivinicultural Origin; International Organisation of Vine and Wine. Paris, France 2019.

- Cetó, X.; Gutiérrez, J. M.; Gutiérrez, M.; Céspedes, F.; Capdevila, J.; Mínguez, S.; Jiménez-Jorquera, C.; del Valle, M. Determination of total polyphenol index in wines employing a voltammetric electronic tongue. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 732, 172–179. [CrossRef]

- Rufino, M. D. S. M.; Alves, R. E.; de Brito, E. S.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Saura-Calixto, F.; Mancini-Filho, J. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacities of 18 non-traditional tropical fruits from Brazil. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 996–1002. [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [CrossRef]

- Pulido, R.; Bravo, L.; Saura-Calixto, F. Antioxidant activity of dietary polyphenols as determined by a modified ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3396–3402. [CrossRef]

- Canas, S.; Belchior, A.P.; Spranger, M.I.; Bruno-De-Sousa, R. High-performance liquid chromatography method for analysis of phenolic acids, phenolic aldehydes, and furanic derivatives in brandies. Development and validation. J. Sep. Sci. 2003, 26(6-7), 496–502. [CrossRef]

| LMW Compounds (mg/L) | 1Y | 4Y | ||||||||

| B1Y | O151Y | O301Y | O601Y | N1Y | B4Y | O154Y | O304Y | O604Y | N4Y | |

| HMF | 40.75 ± 1.46Ba | 33.38 ± 11.36Aa | 30.41 ± 4.68Ba | 26.63 ± 1.63Aa | 29.72 ± 5.80Ba | 31.89 ± 0.73Ab | 20.94 ± 6.72Ab | 18.91 ± 2.71Aa | 20.90 ± 7.48Ab | 17.35 ± 4.21Aa |

| Furf | 51.92 ± 1.72Ba | 72.81 ± 5.83Ac | 67.94 ± 3.73Bc | 72.42 ± 3.55Ac | 62.95 ± 0.97Bb | 46.49 ± 1.80Aa | 64.83 ± 5.80Ac | 59.39 ± 2.88Ac | 67.16 ± 4.19Ac | 56.16 ± 0.99Ab |

| 5Mfurf | 0.87 ± 0.20Bb | 0.82 ± 0.23Bab | 0.71 ± 0.09Bab | 0.60 ± 0.15Bab | 0.48 ± 0.17Ba | 0.27 ± 0.11Aa | 0.21 ± 0.090Aa | 0.21 ± 0.12Aa | 0.34 ± 0.04Aa | 0.19 ± 0.06Aa |

| Gall | 171.70 ± 12.74Bc | 122.50 ± 14.73Bb | 102.30 ± 14.41Bab | 104.60 ± 1.08Bab | 84.14 ± 15.17Ba | 137.70 ± 17.51Ab | 58.06 ± 7.26Aa | 59.36 ± 8.60Aa | 67.34 ± 18.52Aa | 41.66 ± 8.34Aa |

| Ellag | 17.72 ± 1.03Aa | 21.73 ± 2.29Abc | 21.83 ± 0.86Bbc | 23.44 ± 0.45Ac | 19.31 ± 0.90Bab | 16.17 ± 0.71Aa | 18.68 ± 1.73Aa | 19.04 ± 0.89Aa | 22.91 ± 2.84Ab | 16.72 ± 0.55Aa |

| Van | 12.58 ± 0.40Aa | 17.42 ± 5.83Aa | 17.18 ± 2.41Aa | 15.01 ± 0.14Aa | 16.07 ± 2.59Aa | 16.62 ± 2.86Ba | 16.29 ± 6.25Aa | 17.78 ± 3.91Aa | 15.05 ± 0.94Aa | 15.15 ± 3.48Aa |

| Syrg | 6.02 ± 0.50Aa | 13.12 ± 1.49Ab | 12.16 ± 0.92Ab | 12.97 ± 0.85Ab | 11.27 ± 0.72Ab | 6.75 ± 0.26Aa | 13.51 ± 0.99Ac | 13.10 ± 0.76Abc | 14.31 ± 1.12Ac | 11.48 ± 1.03Ab |

| Fer | 0.26 ± 0.03Aa | 0.37 ± 0.11Aab | 0.46 ± 0.08Ab | 0.43 ± 0.04Ab | 0.33 ± 0.02Aab | 0.29 ± 0.04Aa | 0.55 ± 0.15Ab | 0.50 ± 0.13Aab | 0.48 ± 0.12Aab | 0.37 ± 0.03Aab |

| Vanil | 6.17 ± 0.08Ab | 6.53 ± 0.20Abc | 6.29 ± 0.27Abc | 6.88 ± 0.29Ac | 4.94 ± 0.49Aa | 6.50 ± 0.35Aab | 6.51 ± 0.46Aab | 6.32 ± 0.12Aab | 7.93 ± 1.99Ab | 5.15 ± 0.56Aa |

| Syrde | 13.59 ± 0.19Aa | 17.20 ± 0.11Ab | 16.01 ± 0.49Ab | 17.50 ± 0.38Ab | 13.53 ± 1.89Aa | 17.59 ± 0.78Ba | 20.99 ± 0.91Bab | 19.82 ± 0.88Bab | 24.30 ± 5.43Bb | 16.68 ± 2.30Ba |

| Cofde | 9.17 ± 0.35Ab | 5.82 ± 0.23Aa | 5.81 ± 0.31Aa | 6.09 ± 0.89Aa | 5.62 ± 0.27Aa | 8.90 ± 0.23Ab | 5.57 ± 0.54Aa | 5.51 ± 0.37Aa | 5.96 ± 0.88Aa | 5.36 ± 0.05Aa |

| Sipde | 30.36 ± 1.43Bb | 25.45 ± 0.39Bba | 23.98 ± 0.85Ba | 27.06 ± 2.25Ba | 24.96 ± 1.40Ba | 21.47 ± 2.29Aa | 17.04 ± 2.91Aa | 15.95 ± 2.95Aa | 20.51 ± 2.87Aa | 17.43 ± 1.15Aa |

| LMW Compounds (mg/L) | 1Y | 4Y | ||||||||

| B1Y | O151Y | O301Y | O601Y | N1Y | B4Y | O154Y | O304Y | O604Y | N4Y | |

| Total furanic aldehydes | 93.54 ± 3.27Ba | 107.01 ± 16.91Ba | 99.06 ± 1.57Ba | 99.65 ± 5.32Ba | 93.16 ± 6.25Ba | 78.65 ± 2.49Aa | 85.97 ± 12.62Aa | 78.51 ± 1.39Aa | 88.40 ± 11.54Aa | 73.69 ± 4.82Aa |

| Total phenolic acids | 208.30 ± 12.83Bc | 175.20 ± 5.76Bb | 153.90 ± 16.91Bab | 156.40 ± 1.13Bab | 131.10 ± 17.17Ba | 177.50 ± 21.18Ab | 107.10 ± 6.02Aa | 109.80 ± 12.80Aa | 120.10 ± 19.39Aa | 85.37 ± 10.61Aa |

| Total phenolic aldehydes | 59.28 ± 1.91Bb | 54.99 ± 0.57Ab | 52.09 ± 1.71Aab | 57.53 ± 3.75Ab | 49.04 ± 3.92Aa | 54.46 ± 1.68Ab | 50.10 ± 3.83Aab | 47.60 ± 3.55Aab | 58.69 ± 10.81Ab | 44.62 ± 2.36Aa |

| Total LMWC | 361.10 ± 12.85Bc | 337.10 ± 12.24Bbc | 305.10 ± 17.44Bb | 313.60 ± 7.91Ab | 273.30 ± 20.67Ba | 310.60 ± 24.48Ac | 243.20 ± 17.76Aab | 235.90 ± 14.98Aab | 267.20 ± 40.99Abc | 203.70 ± 12.64Aa |

| Analytical parameters | 1Y | 4Y | ||||||||

| B1y | O151y | O301y | O601y | N1y | B4y | O154y | O304y | O604y | N4y | |

| Alcoholic strength by volume (% v/v) |

76.38 ± 0.13Aa | 77.09 ± 0.11Ab | 77.09 ± 0.11Ab | 77.16 ± 0.17Ab | 76.72 ± 0.26Aab | 76.14 ± 0.20Aa | 77.05 ± 0.17Ab | 77.04 ± 0.21Ab | 77.24 ± 0.22Ab | 76.37 ± 0.33Aa |

| Total acidity (g acetic acid/L AE) |

0.89 ± 0.13Bd | 0.69 ± 0.01Ac | 0.66 ± 0.03Ab | 0.67 ± 0.01Abc | 0.58 ± 0.01Aa | 0.82 ± 0.03Ad | 0.74 ± 0.01Bc | 0.70 ± 0.01Bb | 0.71 ± 0.01Bb | 0.64 ± 0.02Ba |

| Fixed acidity (g acetic acid/L AE) |

0.44 ± 0.02Bc | 0.34 ± 0.01Ab | 0.32 ± 0.02Ab | 0.33 ± 0.01Ab | 0.27 ± 0.02Aa | 0.34 ± 0.02Ac | 0.33 ± 0.03Abc | 0.32 ± 0.02Ab | 0.32 ± 0.01Abc | 0.27 ± 0.01Aa |

| Volatile acidity (g acetic acid/L AE) |

0.45 ± 0.02Ac | 0.35 ± 0.01Ab | 0.35 ± 0.02Ab | 0.34 ± 0.01Ab | 0.31 ± 0.01Aa | 0.48 ± 0.03Bc | 0.41 ± 0.03Bb | 0.39 ± 0.01Bba | 0.39 ± 0.01Bba | 0.37 ± 0.03Ba |

| Total dry extract (g/L) |

2.37 ± 0.23Ab | 2.43 ± 0.08Ab | 2.27 ± 0.14Ab | 2.37 ± 0.04Ab | 2.03 ± 0.06Aa | 2.46 ± 0.10Ac | 2.44 ± 0.08Abc | 2.36 ± 0.01Ab | 2.38 ± 0.05Abc | 2.07 ± 0.01Aa |

| pH | 4.11 ± 0.05Ba | 4.16 ± 0.02Bb | 4.14 ± 0.01Bab | 4.18 ± 0.01Bb | 4.24 ± 0.02Bc | 3.97 ± 0.09Aa | 4.04 ± 0.04Ab | 4.07 ± 0.02Ab | 3.95 ± 0.03Aa | 4.12 ± 0.04Ac |

| Peak | RT (min.) | λmax (nm) |

Precursor Ion (m/z) [M−H]+ |

Precursor Ion (m/z) [M−H]− |

Product Ions m/z (% Base Peak) |

Tentative Identification |

References |

| 1 | 6.2 | 147 | 103(100) | Citramalic acid | [88,89] | ||

| 2 | 7.87 | 133 | 115(100), 113(40), 71(20) | Malic acid | [88,90] | ||

| 3 | 8.13 | 273 | 331 | 169(100), 125(35) | Galloyl glucose | [27,91,92] | |

| 4 | 8.42 | 271 | 331 | 169(80), 271(20), 211(35), 125(55) | Monogalloyl-glucose | [27,92,93] | |

| 5 | 15.5 | 271 | 169 | 125(100) | Gallic acid | [94,95,96] | |

| 6 | 20.03 | 284 | 127 | 127(40), 109(100), 81(30) | HMF | [97,98] | |

| 7 | 22.40 | 290, 326 | 153 | 153(50), 109(100) | Protocatechuic acid | [95,96,99] | |

| 8 | 29.85 | 281 | 97 | 97(100), 69(30) | Furfural | [97,98] | |

| 9 | 33.97 | 274 | 483 | 483 (100), 331(20), 313(30), 271(20), 169(60) | Digalloylglucose 1 | [27,91,95] | |

| 10 | 34.48 | 273 | 483 | 483 (100), 331(20), 313(30), 271(20), 169(60) | Digalloylglucose 2 | [27,91,95] | |

| 11 | 35.33 | 279 | 341 | 341(100), 169(10), 125(10) | Gallic acid-glucoside | [27,92] | |

| 12 | 36.27 | 273 | 321 | 169(100), 125(10) | Digallate | [27,92] | |

| 13 | 39.95 | 273 | 635 | 635(50), 483(30), 465(20), 313(15), 211(10), 169(10) | Trigalloyl glucose | [27,95] | |

| 14 | 40.89 | 263, 292 | 167 | 167(100), 152(30), 108(23), 123(10) | Vanillic acid | [94,95] | |

| 15 | 41.86 | 273 | 197 | 197(100), 161(30), 182(25), 153(60) | Syringic acid | [94,95,96] | |

| 16 | 42.92 | 271 | 493 | 493(100), 331(10), 313(10), 271(20), 211(30), 169(10) | Monogalloyl-diglucose | [93,100] | |

| 17 | 44.05 | 278 | 289 | 289(30), 245(100), 203(10), 179(10) | Epicatechin | [101,102] | |

| 18 | 45.17 | 276 | 787 | 787(30), 635(20), 617(20), 465(15), 313(10) | Tetragalloy glucose | [27,95,103] | |

| 19 | 46.35 | 231, 325 | 193 | 193(50), 178(15), 149(20), 134(100), | Ferulic acid | [95,99] | |

| 20 | 46.65 | 276 | 939 | 939(100), 787(50), 769(40), 635(30), 617(10) | Pentagalloy glucose | [27,92] | |

| Peak | RT (min.) | λmax (nm) |

Precursor Ion (m/z) [M−H]+ |

Precursor Ion (m/z) [M−H]− |

Product Ions m/z (% Base Peak) |

Tentative Identification |

References |

| 21 | 46.72 | 254, 365 | 301 | 301(100), 229(10) | Ellagic acid | [92,95,101] | |

| 22 | 47.25 | 280, 328 | 151 | 151(60), 136(100) | Vanillin | [94,95,104] | |

| 23 | 48.17 | 229, 306 | 181 | 181(80), 166(45), 151(20) | Syringaldehyde | [95,96,101] | |

| 24 | 48.69 | 283, 307 | 167 | 167(30), 109(70) | Methyl protocatechuate | [94,98] | |

| 25 | 49.38 | 250, 361 | 585 | 585(100), 301(30) | Ellagic acid dimer dehydrated | [95,103,104] | |

| 26 | 50.48 | 320 | 307 | 307(100), 261(20), 235(15) | 3-Carbethoxymethyl-flavone | [94] | |

| 27 | 50.93 | 290 | 361 | 361(40), 181(50), 137(100) | Homovanillic acid | [94] | |

| 28 | 51.66 | 271 | 663 | 663(20), 331(100), 169(10) | Monogalloyl-glucose dimer | [91,103] | |

| 29 | 52.3 | 250, 362 | 433 | 443(100), 301(50) | Ellagic acid pentoside | [27,91,100] | |

| 30 | 52.85 | 244, 345 | 207 | 207(100), 192(50) | Sinapaldehyde | [95,103,104] | |

| 31 | 53.24 | 238, 340 | 177 | 177(100), 162(90) | Coniferaldehyde | [95,103,104] | |

| 33 | 54.02 | 274 | 197 | 197(100), 169(20), 125(45) | Ethyl gallate | [94,105] | |

| 34 | 55.88 | 265, 362 | 447 | 447(20), 285(100) | Kaempherol-hexoside | [100] | |

| 35 | 57.82 | 265, 360 | 285 | 285(100), 283(40), 193(50), 177(20) | Kaempferol | [96,101] | |

| 36 | 59.28 | 254, 355 | 367 | 367(100), 301(80) | Ellagic acid derivative | [92,95] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).