Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Winemaking Procedure and General Wine Parameters

2.2. GC-MS Analysis

2.3. Chemicals and Reference Compounds

2.4. Sensory Analysis

2.5. NIR Data

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Basic and Sparkling Wines Chemical Composition

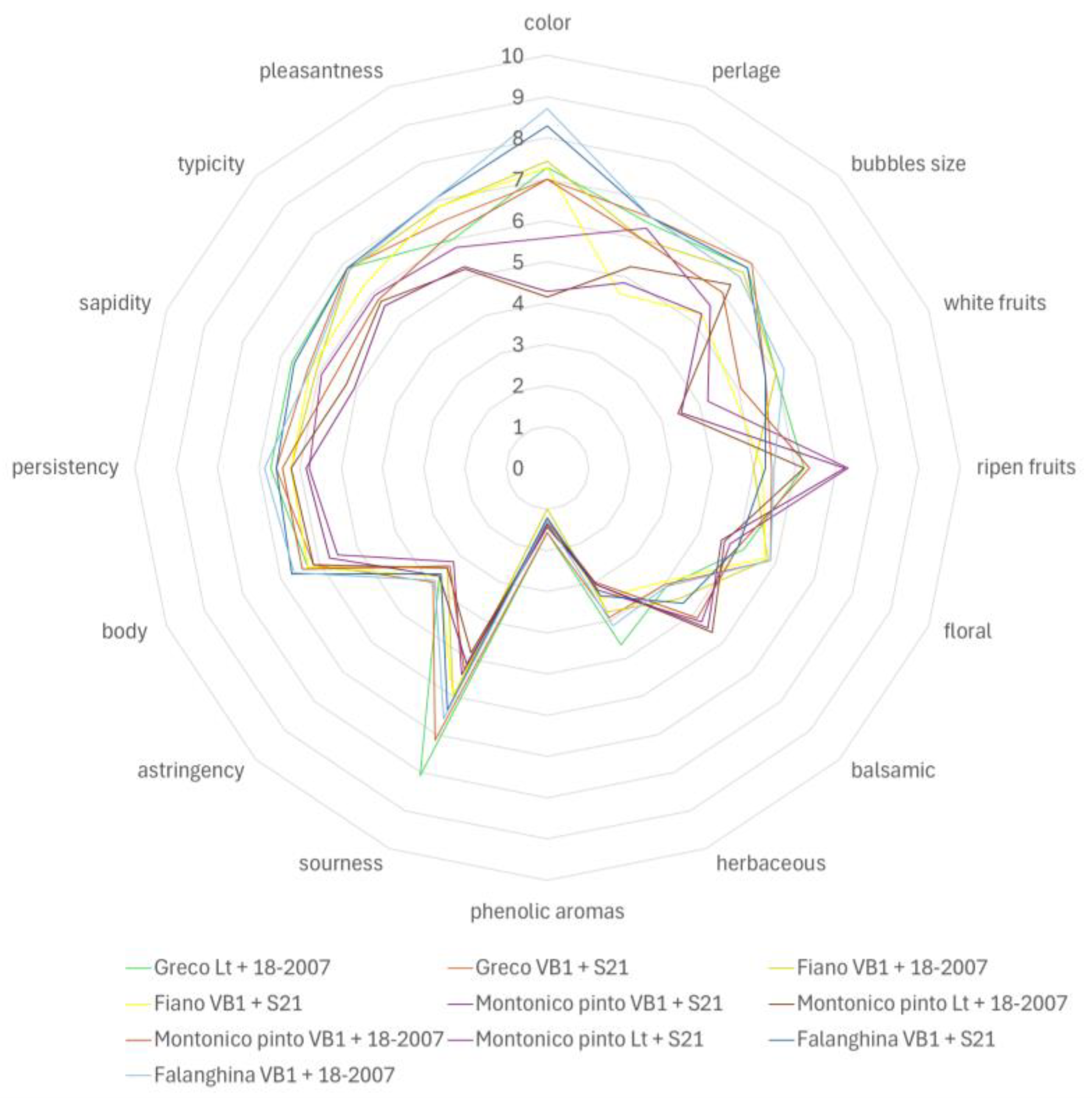

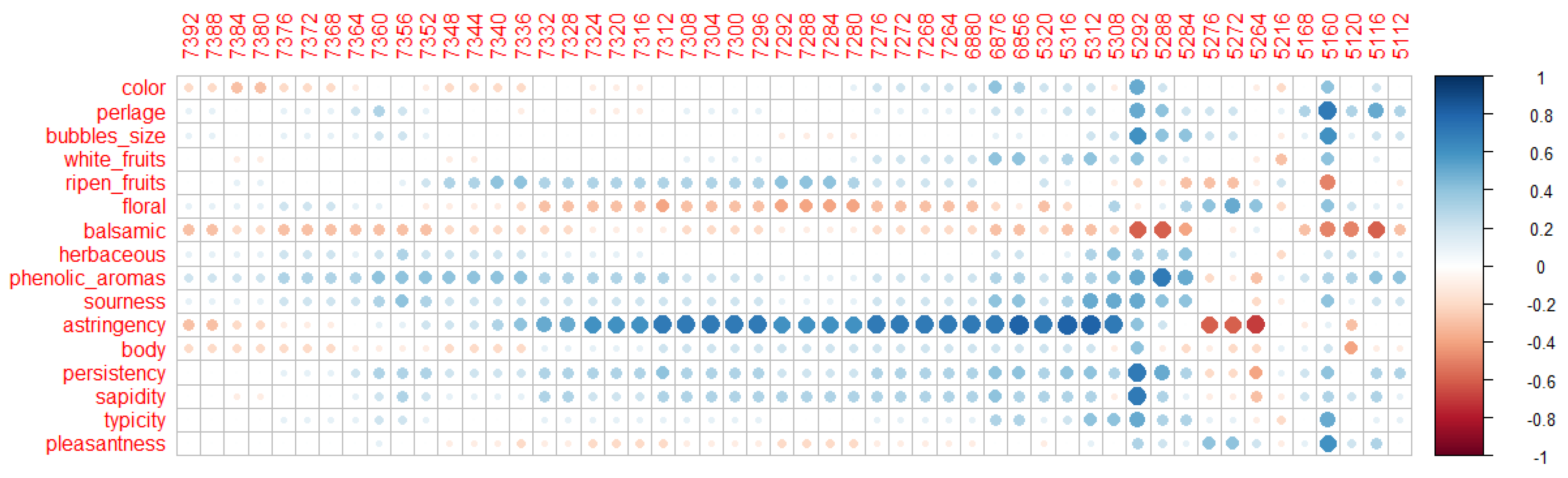

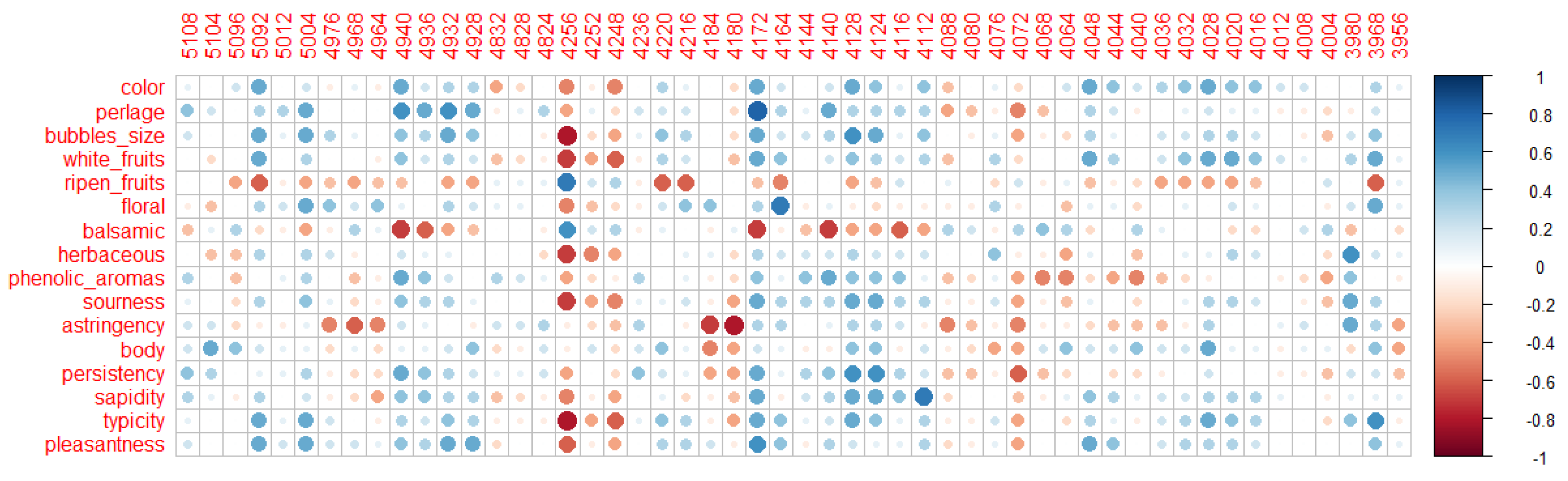

3.2. Sensory Analysis

3.3. Volatilome Analysis

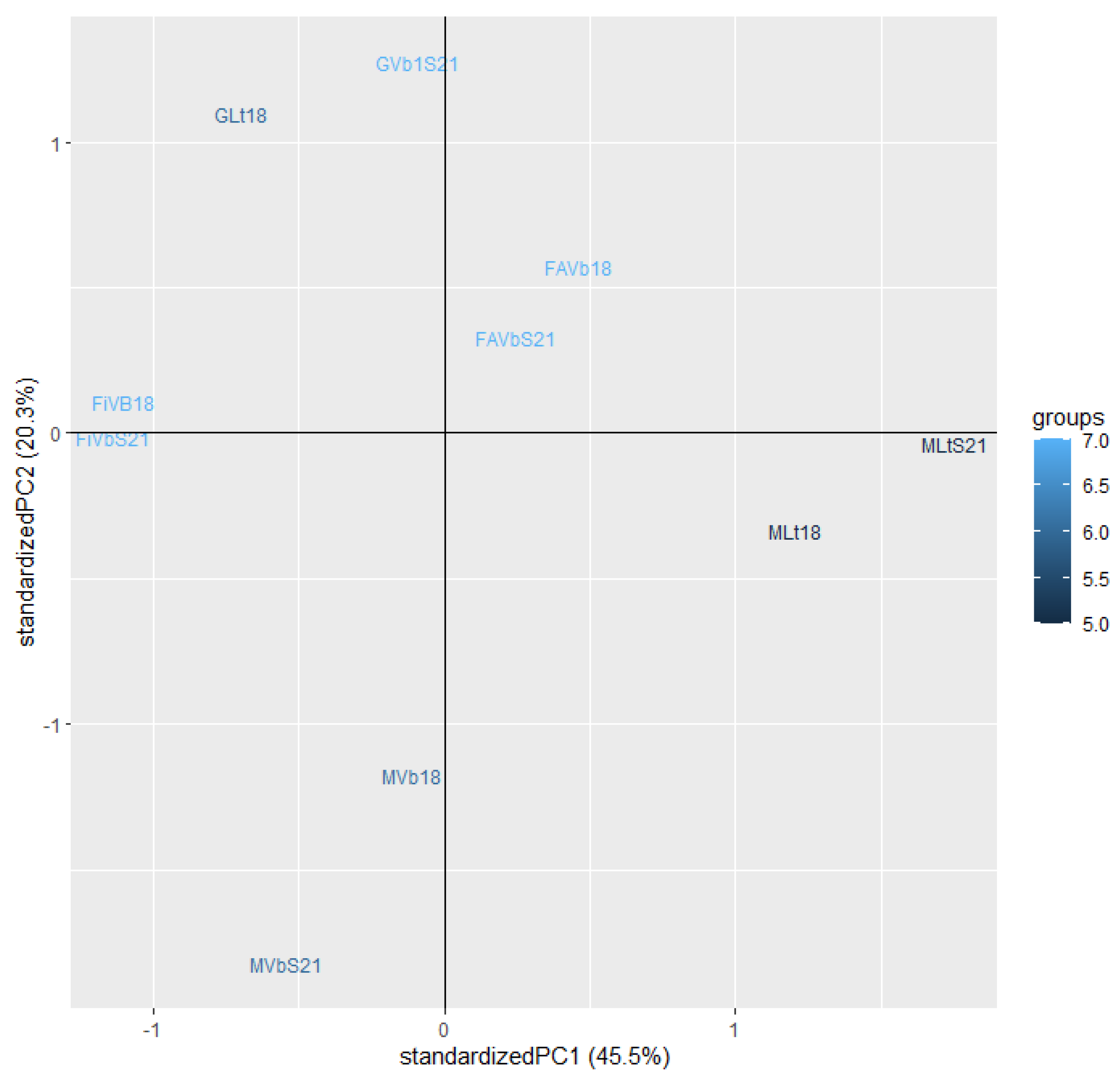

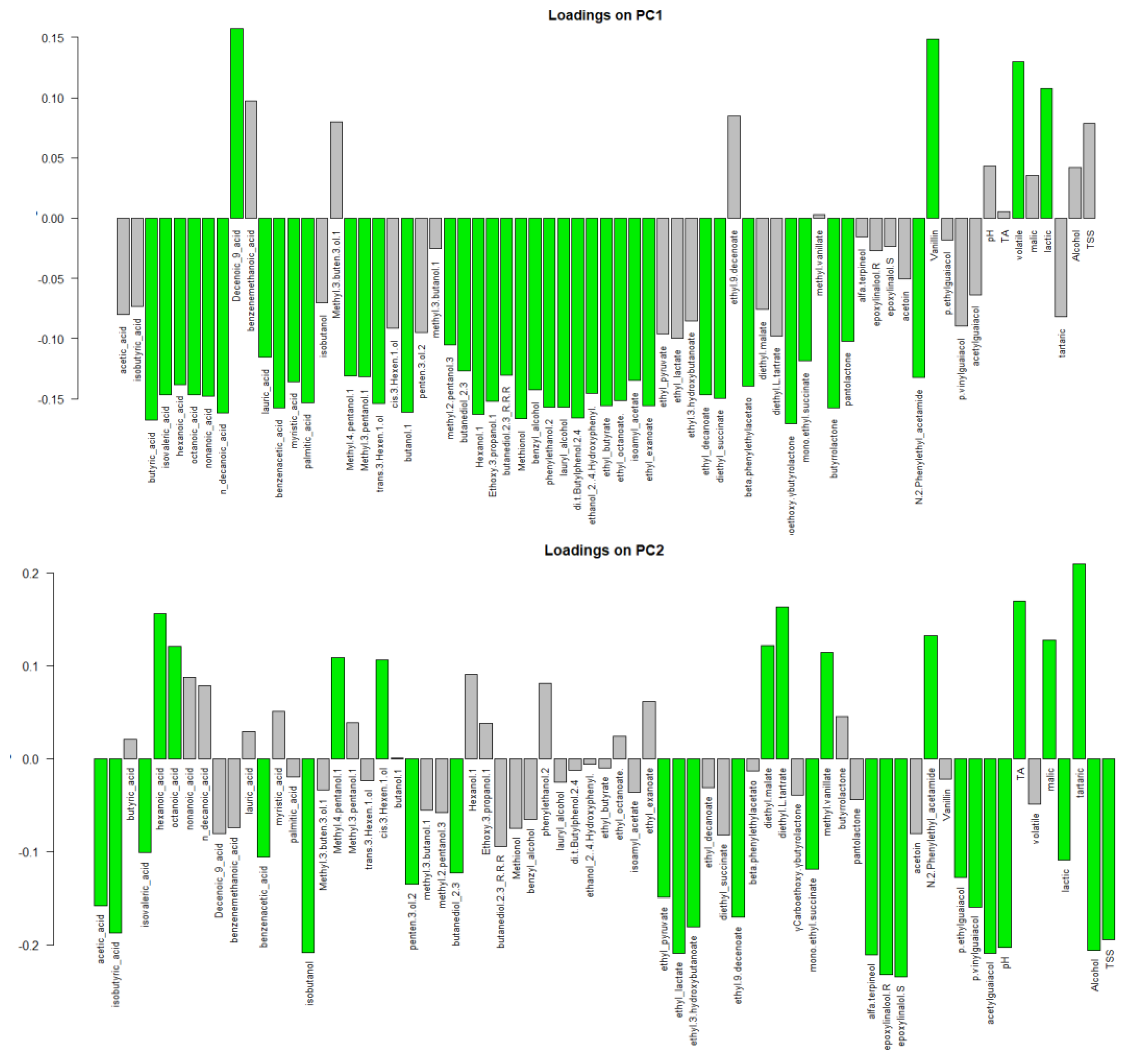

3.4. Odour Activity Value and Principal Component Analysis

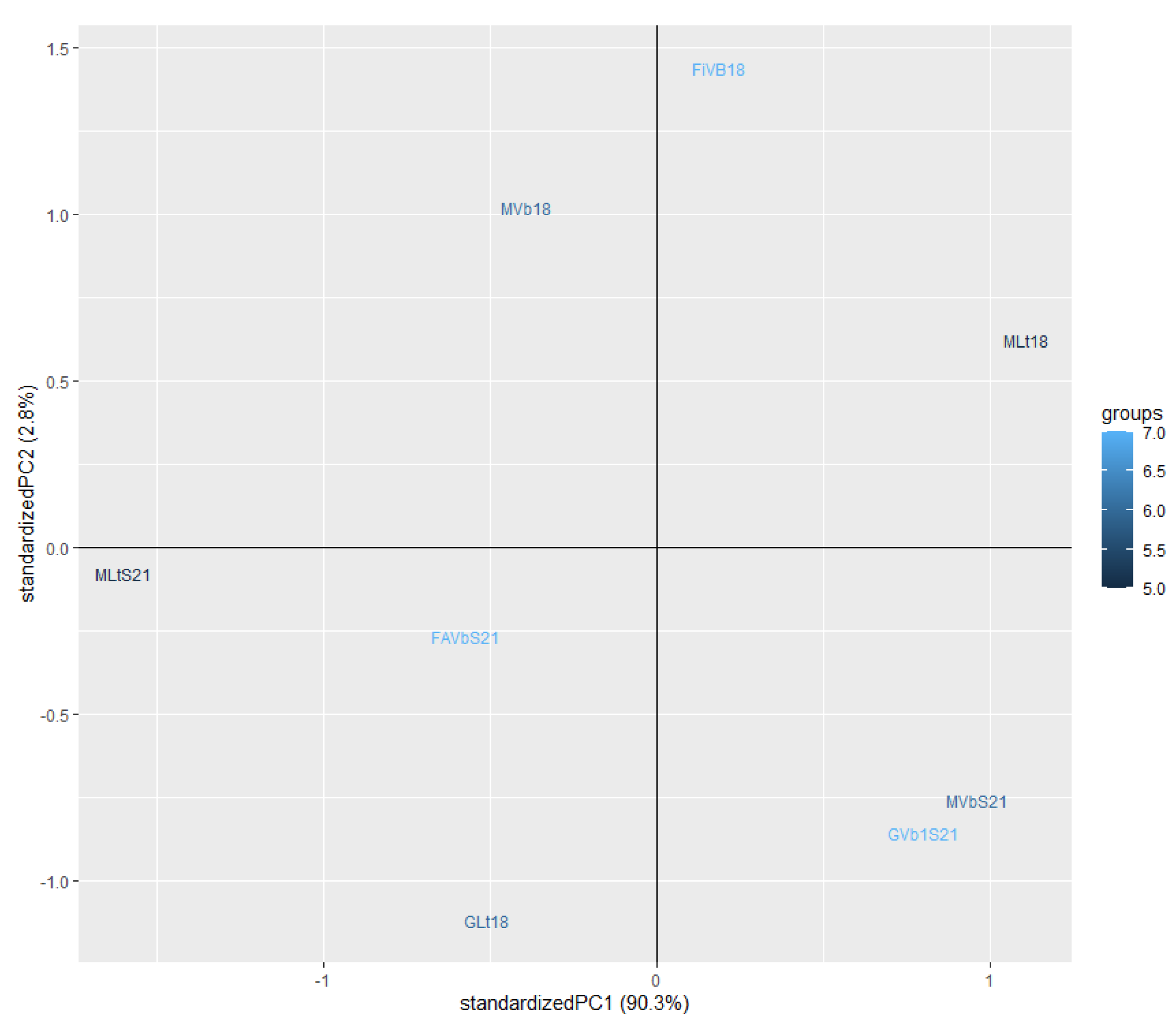

3.5. NIR

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV), State of the world vine and wine sector in 2023. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/2024-04/OIV_STATE_OF_THE_WORLD_VINE_AND_WINE_SECTOR_IN_2023.pdf (accessed on 01 October 2024).

- Italian trade agency, Spirits to outpace beer and wine. Available online: https://www.ice.it/it/news/notizie-dal-mondo/274271 (accessed on 01 October 2024).

- International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV), OIV Focus The Global Sparkling Wine Market. 2023. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/7291/oiv-sparkling-focus-2020.pdf (accessed on 01 October 2024).

- Ritrovato, E. The Wines of Apulia: The Creation of a Regional Brand. In A History of Wine in Europe, 19th to 20th Centuries. Markets, trade and regulation of quality; Conca Messina, S.A., Le Bras, S., Tedeschi, P., Vaquero Piñeiro, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan Cham, Springer Nature: Switzerland, 2019; Volume II, pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.; White, L.; Frost, W. Exploring wine and identity. In Wine and Identity: Branding, Heritage, Terroir; Harvey, M., White, L., Frost, W., Eds.; Routledge: United Kingdom, 2014; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, B.; Zulian, L.; Ferreres, À.; Pastor, R.; Esteve-Zarzoso, B.; Beltran, G.; Mas, A. Sequential Inoculation of Native Non-Saccharomyces and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains for Wine Making. Front Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufariello, M.; Maiorano, G.; Rampino, P.; Spano, G.; Grieco, F.; Perrotta, C.; Capozzi, V.; Grieco, F. Selection of an autochthonous yeast starter culture for industrial production of Primitivo “Gioia del Colle” PDO/DOC in Apulia (Southern Italy). LWT 2019, 99, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, C.; Arena, M.; Laddomada, B.; Cappello, M.; Bleve, G.; Grieco, F.; Beneduce, L.; Berbegal, C.; Spano, G.; Capozzi, V. Starter cultures for sparkling wine. Fermentation 2016, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.; Lisanti, M.T.; Caracciolo, F.; Cembalo, L.; Gambuti, A.; Moio, L.; Siani, T.; Marotta, G.; Nazzarao, C.; Piombino, P. The role of production process and information on quality expectations and perceptions of sparkling wines. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 99, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, C.; Berbegal, C.; Grieco, F.; Tufariello, M.; Spano, G.; Capozzi, V. Selection of indigenous yeast strains for the production of sparkling wines from native Apulian grape varieties. Int J Food Microbiol 2018, 285, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, A.J.; Carrascosa, A.V.; Barcenilla, J.M.; Pozo-Bayón, M.A.; Polo, M.C. Autolytic capacity and foam analysis as additional criteria for the selection of yeast strains for sparkling wines production. Food Microbiol 2001, 18, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsico, A.D.; Velenosi, M.; Perniola, R.; Bergamini, C.; Sinonin, S.; David-Vaizant, V.; Maggiolini, F.A.M.; Hervè, A.; Cardone, M.F.; Ventura, M. Native Vineyard Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts Used for Biological Control of Botrytis cinerea in Stored Table Grape. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hranilovic, A.; Gambetta, J.M.; Schmidtke, L.; Boss, P.K.; Grbin, P.R.; Masneuf-Pomarede, I.; Bely, M.; Albertin, W.; Jiranek, V. Oenological traits of Lachancea thermotolerans show signs of domestication and allopatric differentiation. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 14812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudil, L.; Russo, P.; Berbegal, C.; Albertin, W.; Spano, G.; Capozzi, V. Non-Saccharomyces commercial starter cultures: scientific trends, recent patents and innovation in the wine sector. Recent Pat Food Nutr Agric 2020, 11, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV), Compendium of methods of wine and must analysis. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/standards/compendium-of-international-methods-of-wine-and-must-analysis (accessed on 01 October 2024).

- McMahon, K.M.; Diako, C.; Aplin, J.; Mattinson, D.S.; Culver, C.; Ross, C.F. Trained and consumer panel evaluation of sparkling wines sweetened to brut or demi sec residual sugar levels with three different sugars. Food Res Int 2017, 99, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crumpton, M.; Rice, C.J.; Atkinson, A.; Taylor, G.; Marangon, M. The effect of sucrose addition at dosage stage on the foam attributes of a bottle-fermented English sparkling wine. J Sci Food Agric 2018, 98, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perestrelo, R.; Fernandes, A.; Albuquerque, F.F.; Marques, J.C.; Câmara, J.S. Analytical characterization of the aroma of Tinta Negra Mole red wine: Identification of the main odorants compounds. Analytica chimica acta 2006, 563, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, W.V.; White, K.G.; Heatherbell, D.A. Exploring the nature of wine expertise: What underlies wine experts’ olfactory recognition memory advantage. Food Qual Prefer 2004, 15, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, S.; Pilar Francino, M.; Rufián Henares, J.Á. Why is it important to understand the nature and chemistry of tannins to exploit their potential as nutraceuticals? Food Res Int 2023, 173, 113329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2024. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 01 October 2024).

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. R package 'corrplot': Visualization of a Correlation Matrix. (Version 0.95). 2024. Available online: https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot (accessed on 01 October 2024).

- Vu, V.Q. ggbiplot: A ggplot2 Based Biplot. R Package, Version 0.55. 2011. Available online: http://github.com/vqv/ggbiplot (accessed on 01 October 2024).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer Cham: New York, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Viroli, C.; Gormley, I.C. Infinite Mixtures of Infinite Factor Analysers. Bayesian Anal 2020, 15, 937–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucheryavskiy, S. mdatools—R package for chemometrics. Chemom Intell Lab Syst 2020, 198, 103937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seisonen, S.; Vene, K.; Koppel, K. The current practice in the application of chemometrics for correlation of sensory and gas chromatographic data. Food Chem 2016, 210, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hranilovic, A.; Albertin, W.; Liacopoulos Capone, D.; Gallo, A.; Grbin, P.R.; Danner, L.; Bastian, S.E.P.; Masneuf-Pomarede, I.; Coulon, J.; Bely, M.; Jiranek, V. Impact of Lachancea thermotolerans on chemical composition and sensory profiles of Merlot wines, Food Chem 2021, 349, 129015. [CrossRef]

- Antonacci, D. Grape Vines of Apulia; Publisher: Adda Ed., Bari, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-8880826217.

- Borrull, A.; Poblet, M.; Rozès, N. New insights into the capacity of commercial wine yeasts to grow on sparkling wine media. Factor screening for improving wine yeast selection. Food Microbiol 2015, 48, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravero, M.C. Innovations in Sparkling Wine Production: A Review on the Sensory Aspects and the Consumer’s Point of View. Beverages 2023, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gianvito, P.; Perpetuini, G.; Tittarelli, F.; Schirone, M.; Arfelli, G.; Piva, A.; Patrignani, F.; Lanciotti, R.; Olivastri, L.; Suzzi, G.; Tofalo, R. Impact of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains on traditional sparkling wines production. Food Res Int 2018, 109, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, A.J.; Polo, M.C. Characterization of the nitrogen compounds released during yeast autolysis in a model wine system. J Agric Food Chem 2000, 48, 1081–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufariello, M.; Maiorano, G.; Rampino, P.; Spano, G.; Grieco, F.; Perrotta, C.; Capozzi, V.; Grieco, F. Selection of an autochthonous yeast starter culture for industrial production of Primitivo “Gioia del Colle” PDO/DOC in Apulia (Southern Italy). LWT 2019, 99, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.J.; Jimenez, M.; Huerta, T.; Pastor, A. Contribution of different yeasts isolated from musts of monastrell grapes to the aroma of wine. Int J Food Microbiol 1991, 14, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrens, J.; Urpí, P.; Riu-Aumatell, M.; Vichi, S.; López-Tamames, E.; Buxaderas, S. Different commercial yeast strains affecting the volatile and sensory profile of cava base wine. Int J Food Microbiol 2008, 124, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufariello, M.; Palombi, L.; Rizzuti, A.; Musio, B.; Capozzi, V.; Gallo, V.; Mastrorilli, P.; Grieco, F. Volatile and chemical profiles of Bombino sparkling wines produced with autochthonous yeast strains. Food Control 2023, 145, 109462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatonnet, P.; Dubourdieu, D.; Boidron, J.; Lavigne, V. Synthesis of volatile phenols by Saccharomyces cerevisiae in wines. J Sci Food Agric 1993, 62, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriano, S.; Basile, T.; Tarricone, L.; Di Gennaro, D.; Tamborra, P. Effects of skin maceration time on the phenolic and sensory characteristics of Bombino Nero rosé wines. Ital J Agron 2015, 10, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunhua Zhu, Qi Lu, Xianyan Zhou, Jinxue Li, Jianqiang Yue, Ziran Wang, Siyi Pan, Metabolic variations of organic acids, amino acids, fatty acids and aroma compounds in the pulp of different pummelo varieties, LWT 2020, 130, 109445. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; de la Fuente, A.; Sáenz-Navajas, M. P. 1 - Wine aroma vectors and sensory attributes. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, Managing Wine Qualit, 2nd ed.; Reynolds, A.G., Ed.; Publisher: Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2022; pp. 3-39. [CrossRef]

- Patton, S.; Josephson, D.V. A method for determining significance of volatile flavor compounds in foods. J Food Sci 1957, 22, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottmann, J. Vestner, J. Fischer, U. Sensory relevance of seven aroma compounds involved in unintended but potentially fraudulent aromatization of wine due to aroma carryover. Food Chem 2023, 402, 134160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-García, R.; García-Martínez, T.; Puig-Pujol, A.; Mauricio, J. C.; Moreno, J. Changes in sparkling wine aroma during the second fermentation under CO2 pressure in sealed bottle. Food Chem 2017, 237, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Egidio, V.; Sinelli, N.; Giovanelli, G.; Moles, A.; Casiraghi, E. NIR and MIR spectroscopy as rapid methods to monitor red wine fermentation. Eur Food Res Technol 2010, 230, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsico, A.D.; Perniola, R.; Cardone, M.F.; Velenosi, M.; Antonacci, D.; Alba, V.; Basile, T. Study of the Influence of Different Yeast Strains on Red Wine Fermentation with NIR Spectroscopy and Principal Component Analysis. J 2018, 1, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xia, Y. Pretreating and normalizing metabolomics data for statistical analysis. Genes Diseases 2024, 11, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petronilho, S.; Lopez, R.; Ferreira, V.; Coimbra, M.A.; Rocha, S.M. Revealing the Usefulness of Aroma Networks to Explain Wine Aroma Properties: A Case Study of Portuguese Wines. Molecules 2020, 25, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenglin Zhu, Zhibo Yang, Xuan Lu, Yuwen Yi, Qing Tian, Jing Deng, Dan Jiang, Junni Tang, Luca Laghi, Effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains on the metabolomic profiles of Guangan honey pear cider. LWT 2023, 182, 114816. [CrossRef]

- Basile, T.; Mallardi, D.; Cardone, M.F. Spectroscopy, a Tool for the Non-Destructive Sensory Analysis of Plant-Based Foods and Beverages: A Comprehensive Review. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, S.; Francino, M.P.; Rufián Henares, Á. J. Why is it important to understand the nature and chemistry of tannins to exploit their potential as nutraceuticals? Food Res Int 2023, 173 Pt 2, 113329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guth, H. Quantification and sensory studies of character impact odorants of different white wine varieties. J Agric Food Chem 1997, 45, 3027–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, R.A.; Mauricio, J.C.; Moreno, J. Aromatic series in sherry wines with gluconic acid subjected to different biological aging conditions by Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. capensis. Food Chem 2006, 94, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, R.A.; Moreno, J.; Bueno, J.E.; Moreno, J.A.; Mauricio, J.C. Comparitive study of aromatic compounds in two young white wines subjected to pre-fermentative cryomaceration. Food Chem 2004, 84, 589–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welke, J.E.; Zanus, M.; Lazzarotto, M.; Alcaraz Zini, C. Quantitative analysis of headspace volatile compounds using comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography and their contribution to the aroma of Chardonnay wine. Food Res Int 2014, 59, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibniz-LSB@TUM Odorant Database. Available online: https://www.leibniz-lsb.de/en/datenbanken/leibniz-lsbtum-odorant-database/odorantdb (accessed on 01 October 2024).

- Meilgaard, M.C. Flavor chemistry of beer: part II: flavor and threshold of 239 aroma volatiles. Techn Q Master Brew Assoc Am 1975, 12, 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zheng, F.; Lin, B.; Wu, F.; Verma, K.K.; Chen, G. Assessment of Characteristic Flavor and Taste Quality of Sugarcane Wine Fermented with Different Cultivars of Sugarcane. Fermentation 2024, 10, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M.; Zapata, J.; Culleré, L.; Franco-Luesma, E.; de-la-Fuente-Blanco, A.; Ferreira, V. Optimization and Validation of a Method to Determine Enolones and Vanillin Derivatives in Wines-Occurrence in Spanish Red Wines and Mistelles. Molecules 2023, 28, 4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suyoung Kang, Han Yan, Yin Zhu, Xu Liu, Hai-Peng Lv, Yue Zhang, Wei-Dong Dai, Li Guo, Jun-Feng Tan, Qun-Hua Peng, Zhi Lin, Identification and quantification of key odorants in the world’s four most famous black teas. Food Res Int 2019, 121, 73-83. [CrossRef]

- Lytra, G.; Cameleyre, M.; Tempere, S.; Barbe, J.-C. J Agric Food Chem 2015, 63, 10484-10491. [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Fiano Lt† | Fiano VB1 | Greco Lt | Greco VB1 | Falanghina VB1 |

Montonico Lt |

Montonico Vb1 |

| pH | 3.13±0.10 c | 3.11±0.09 c | 2.74±0.10 a | 2.82±0.09 ab | 2.86±0.07 ab | 3.08±0.08 c | 3.12±0.08 c |

| TA g/L |

6.22±0.28 a | 6.75±0.25 a | 10.12±0.28 d | 9.90±0.23 d | 8.85±0.25 c | 7.50±0.28 b | 7.80±0.25 b |

| Volatile acidity g/L |

0.38±0.03 c | 0.24±0.02 a | 0.45±0.02 d | 0.29±0.03 ab | 0.39±0.02 c | 0.28±0.03 ab | 0.34±0.03bc |

| Malic acid g/L | 1.36±0.11 a | 1.55±0.12 a | 3.42±0.27 c | 3.30±0.26 c | 2.93±0.23 c | 2.34±0.18 b | 2.28±0.15 b |

| Lactic acid g/L | 0.17±0.01 d | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01±0.01 a | 0.04±0.01 b | 0.10±0.01 c |

| Alcohol % vol |

12.8±0.3 bc | 12.9±0.5 bc | 10.0±0.4 ab | 9.8±0.3 a | 12.1±0.4 b | 13.6±0.5c | 13.5±0.4c |

| Total SO2 mg/L | 41.0±0.3 a | 48.0±0.2 b | 59.0±0.2 c | 57.0±0.3 b | 57.0±0.2 b | 57.0±0.2 b | 73.0±0.3 d |

| Residual sugars g/L | 0.89±0.08 c | 0.50±0.02 b | 2.37±0.20 d | 0.00 | 0.24±0.02 a | 3.03±0.03 e | 4.47±0.02 f |

| Total polyphenols mg/L | 150±6 a | 163±4 b | 530±12 g | 238±5c | 285±6d | 365±3 e | 431±11 f |

| Parameters | Fi VB1 +Sc† | Fi VB1 +S21 | G Lt +Sc | G VB1 +S21 | Fa Vb1 +Sc | FaVb1 +S21 |

M Lt +S21 |

M VB1 +Sc |

M Lt +Sc |

M VB1 +S21 |

| pH | 3.09±0.06bc | 3.08±0.08bc | 2.79±0.05a | 2.77±0.06a | 2.93±0.10ab | 3.08±0.05bc | 3.15±0.05c | 3.10±0.05c | 3.11±0.07c | 3.12±0.05c |

| Total acidity g/L | 6.40±0.27a | 6.70±0.25a | 9.50±0.28d | 9.50±0.25d | 8.70±0.26c | 6.70±0.25a | 6.50±0.26a | 7.01±0.25a | 8.10±0.28b | 6.80±0.25a |

| Volatile acidity g/L | 0.28±0.04ab | 0.27±0.03a | 0.28±0.03ab | 0.24±0.03a | 0.44±0.03d | 0.38±0.03cd | 0.39±0.04cd | 0.30±0.03a | 0.41±0.05d | 0.34±0.03bc |

| Malic acid g/L |

1.41±0.11a | 1.32±0.12a | 2.80±0.12d | 2.70±0.10cd | 2.54±0.12c | 2.53±0.15cd | 1.80±0.11b | 2.10±0.11b | 2.04±0.12b | 1.98±0.11b |

| Lactic acid g/L |

0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01±0.01a | 0.18±0.01c | 0.00 | 0.10±0.01b | 0.12±0.01b |

| Tartaric acid g/L |

3.21±0.05c | 3.21±0.05c | 4.06±0.05d | 4.23±0.06d | 2.88±0.05b | 2.97±0.04b | 2.55±0.05a | 2.57±0.05a | 2.55±0.04a | 2.56±0.04a |

| Alcohol %vol |

12.8±0.6bc | 12.7±0.4bc | 10.5±0.5a | 10.6±0.3a | 12.0±0.4b | 12.7±0.5bc | 13.0±0.5c | 13.2±0.5c | 13.0±0.4c | 12.9±0.5bc |

| Residualsugars g/L | 10.07±0.09c | 13.40±0.11e | 1.22±0.04a | 1.15±0.03a | 9.03±0.09c | 7.18±0.05b | 18.08±0.15g | 13.00±0.12d | 19.08±0.12h | 15.42±0.14f |

| CAS | Molecules |

Fi Vb1+Sc† |

Fi Vb1+ S21 |

G Lt+Sc |

G Vb1+ S21 |

Fa Vb1+ Sc |

Fa Vb1+ S21 |

M Lt+Sc |

M Lt +S21 |

M Vb1+Sc |

M Vb1+S21 |

| Acids | |||||||||||

| 64-19-7 | Acetic Acid | 3128.8 ± 472.1 bcd | n.d. | 3317.0±500.5 bc | 1971.0297.4ab | 3417.2±515.6cd | 3390.7±511.6cd | 2853.8±430.6abc | 1503.2±226.8a | 4397.9±663.6d | 4354.6±657.1d |

| 79-31-2 | Isobutyric Acid | 188.1 ±21.7 d | 132.4±15.3 bcd | 165.1±19.1d | 77.6±9.0ab | 134.5±15.5bcd | 91.5±10.6abc | 148.9±17.2cd | 57.6±6.6a | 323.3±37.3f | 252.5±29.1 e |

| 107-92-6 | Butyric Acid | 399.6±37.8 cd | 502.9±47.5 e | 473.8±44.8de | 351.9±33.3cb | 340.9±32.2cb | 346.1±32.7cb | 260.5±24.6b | 151.8±14.4a | 358.6±33.9cb | 402.2±38.0cde |

| 503-74-2 | Isovaleric Acid | 307.8 ± 20.5 cd | 312.8 ±20.8cd | 352.7±23.5 de | 238.3±15.9bc | 245.0±16.3bc | 228.1±15.2bc | 181.8±12.1b | 103.4±6.9a | 374.0±24.9de | 401.4±26.7e |

| 142-62-1 | Hexanoic Acid | 3170.4 ±270.8 ef | 3220.7±275.1 f | 3469.9±296.4f | 2707.9±231.3de | 2454.6±209.7d | 2674.5±228.4d | 1634.1±139.6b | 1239.0±105.8a | 1622.4±138.6b | 1932.5±165.1c |

| 124-07-2 | Octanoic Acid | 3493.2 ±366.5 e | 2946.3±309.2 e | 3393.9±356.1e | 2501.9±262.5d | 1981.0±207.9c | 2498.2±262.1d | 1343.1±140.9a | 1375.4±144.3ab | 1554.5±163.1b | 2104.9±220.9cd |

| 112-05-0 | Nonanoic Acid | 13.4 ±.5 b | 13.9±2.6 bc | 15.8±3.0c | 12.5±2.4bc | 12.4±2.4bc | 13.3±2.5bc | 10.3±2.0b | 6.5±1.2a | 11.2±2.1bc | 12.2±2.3bc |

| 334-48-5 | N-Decanoic Acid | 770.6±95.9 e | 585.0±72.8 d | 573.5±71.4d | 495.9±61.8 c | 368.7±45.9bc | 326.5±40.7bc | 130.5±16.2a | 130.6±16.3a | 294.2±36.6b | 413.2±51.4c |

| 14436-32-9 | 9-Decenoic Acid | 19.6 ±2.0 bc | 14.1±1.4 a | 20.3±2.1 c | 17.9±1.8b | 154.2±15.7ef | 175.8±17.9fg | 213.5±21.8gh | 229.2±23.4h | 89.3±9.1d | 125.5±12.8e |

| 65-85-0 | Benzenemethanoic Acid | 20.0±3.2b | 21.3±3.4 b | 21.9±3.5bc | 14.2±2.3a | 32.0±5.1d | 54.8±8.8e | 54.9±8.8e | 30.3±4.9d | 30.0±4.8cd | 32.1±5.2d |

| 143-07-7 | Lauric Acid | 10.6 ± 1.3 b | 10.9±1.4 b | n.d. | 5.7±0.7a | n.d. | 5.5±0.7a | n.d. | n.d. | 4.7±0.6a | n.d. |

| 103-82-2 | Benzenacetic Acid | 77.5 ±15.0 cd | 82.7±16.0 cd | 67.7±13.1 b c | 49.1±9.5b | 46.8±9.0b | 67.6±13.1bc | 37.0±5.0b | 24.7±4.8a | 77.9±15.1cd | 88.2±15.0d |

| 544-63-8 | Myristic Acid | 13.8±1.9c | 11.9±1.6c | 11.8±1.6c | 12.3±1.7c | 13.7±1.9c | 13.2±1.8c | 7.2±1.0 b | 5.1±0.7a | 10.5±1.4c | 12.4±1.7c |

| 57-10-3 | Palmitic Acid | 166.4±26.6c | 151.0±23.2c | 132.3±29.1bc | 154.3±24.0c | 141.9±21.0c | 146.4±22.2c | 92.8±20.4ab | 68.9±15.2a | 146.3±22.2c | 165.7±30.1c |

| Alcohols | |||||||||||

| 78-83-1 | Isobutanol | 2179.6±197.1e | 1866.1±168.8cd | 1839.0±166.3cd | 1212.9±109.7a | 1333.1±120.6a | 1597.7±144.5bc | 2016.4±182.4de | 1488.8±134.7b | 1946.8±156.1d | 2873.2±159.9f |

| 763-32-6 | 3-Methyl-3-Buten-1-ol | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.7±0.2 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 626-89-1 | 1-Pentanol- 4-Methyl | 49.5±7.0cd | 55.4±7.8d | 43.7±6.1cd | 39.3±5.5c | 25.7±3.6ab | 25.6±3.6ab | 28.5±4.0b | 21.6±3.0ab | 21.2±3.0a | 26.3±3.7ab |

| 589-35-5 | 3-Methyl-1-Pentanol | 181.8±15.8d | 182.9±15.9d | 119.5±10.4c | n.f. | 83.0±7.2b | 78.3±6.8b | 61.4±5.3a | n.f. | 85.2±7.4b | n.f. |

| 928-97-2 | (E)-3-Hexen-1-ol | 57.0±7.5e | 59.3±7.8e | 46.3±6.1de | 38.1±5.0d | 10.7±1.4a | 12.2±1.6ab | 20.0±2.6c | 14.9±2.0ab | 33.1±4.4d | 45.5±6.0de |

| 928-96-1 | (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol | 23.7±1.5b | 27.4±1.7c | 48.9±3.1e | 39.8±2.5e | 31.0±2.0cd | 30.9±2.0cd | 20.9±1.3b | 14.7±0.9a | 33.1±2.1d | 30.5±1.9cd |

| 71-36-3 | 1-Butanol | 131.6±12.1f | 156.0±13.0f | 81.1±7.7e | 68.7±6.5de | 56.7±5.4c | 67.3±6.4cde | 36.3±3.4b | 23.6±2.2a | 64.9±6.1cd | 85.0±8.0e |

| 1569-50-2 | 3-Penten-2-ol | 3.5±0.9b | 3.1±0.8b | 2.3±0.6ab | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 3.1±0.8b | 1.7±0.4a | 2.3±0.6ab | 3.4±0.8b |

| 123-51-3 | 3-Methylbutan-1-ol | 7687.8±397.3a | 10802.7±558.2b | 20426.7±1055.5f | 15401.2±795.9e | 12328.3±637.1c | 14769.6±763.2de | 13682.5±707.0cd | 10606.0±548.1b | 15257.0±788.4e | 21620.4±1117.2f |

| 565-67-3 | 2-Methyl-3-Pentanol | 43.8±2.0d | 100.0±4.6f | 45.1±2.1d | 70.5±3.2e | 29.0±1.3c | 102.1±4.7f | 11.6±0.5a | 15.9±0.7b | 44.2±2.0d | 112.6±5.2f |

| 513-85-9 | 2,3-Butanediol | 6256.1±973.4e | 7063.0±1098.9e | 2265.5±352.5ab | 1783.4±277.5a | 2685.7±417.9b | 3286.0±511.3bc | 2868.0±446.2b | 1679.7±261.3a | 4308.7±670.4cd | 5107.7±794.7de |

| 111-27-3 | 1-Hexanol | 960.2±81.9e | 958.8±81.7e | 980.1±83.6e | 775.3±66.1d | 445.1±37.9b | 449.1±38.3b | 265.8±22.7a | 205.9±17.6a | 496.8±42.4bc | 568.8±48.5c |

| 111-35-3 | 3-Ethoxy-1-Propanol | 136.0±11.7g | 172.5±14.8h | 72.0±6.2f | 65.6±5.6ef | 49.8±4.3cd | 47.4±4.1c | 13.8±1.2b | 3.5±0.3a | 56.3±4.8de | 47.2±4.1c |

| 513-85-9 | 2, 3-Butanediol (R,R,R) | 1404.1±243.1e | 1678.7±250.6e | 446.0±77.2bc | 316.2±54.7ab | 575.2±99.6c | 609.3±105.5c | 501.0±86.7c | 247.8±42.9a | 943.3±163.3d | 931.1±161.2d |

| 505-10-2 | 3-(Methylthio)-1-propanol | 371.8±1.8d | 463.8±39.6e | 355.3±30.3d | 262.8±22.4c | 257.0±22.0c | 278.5±23.8c | 169.6±14.5b | 96.5±8.2a | 387.9±33.1d | 414.5±35.4de |

| 100-51-6 | Benzyl alchol | 19.9±1.0g | 23.4±1.1h | 9.7±0.5d | 9.2±0.4cd | 7.1±0.3b | 7.9±0.4bc | 8.5±0.4c | 5.7±0.3a | 11.7±0.6e | 14.4±0.7f |

| 60-12-8 | 2-Pheny lethanol | 32237.3±1896.1c | 29835.0±1847.3c | 35421.1±1993.2c | 30068.6±1861.8c | 23662.9±1465.2b | 29991.7±1857.0c | 16383.9±1014.5a | 15652.7±969.2a | 23874.4±1478.3b | 28908.4±1790.0c |

| 112-53-8 | Lauric alcohol | 274.2±22.8g | 222.0±18.5ef | 194.5±16.2de | 242.8±20.2fg | 174.3±14.5cd | 158.3±13.2bc | 140.1±11.7b | 97.0±8.1a | 217.7±18.1ef | 241.0±20.1fg |

| 96-76-4 | 2,4-Di-t-Butylphenol | 384.3±54.0d | 370.6±52.0d | 329.4±46.2bcd | 357.5±50.2cd | 309.0±43.4bcd | 286.6±40.2bc | 256.4±36.0b | 172.0±24.1a | 347.0±48.7bcd | 357.6±50.2cd |

| 501-94-0 | 2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl) Ethanol | 4447.5±578.9def | 5731.8±746.1ef | 4620.9±601.5ef | 2877.4±374.5b | 2843.2±370.1b | 3325.5±432.9bc | 3489.9±454.3bcd | 2066.6±269.0a | 3368.8±438.5bc | 3770.3±490.8cde |

| Esters | |||||||||||

| 105-54-4 | Butanoic acid, Ethyl Ester R | 227.6±41.3e | 176.5±32.0de | 197.3±35.8de | 174.4±31.6de | 22.7±4.1a | 61.1±11.1c | 42.1±7.6b | 38.4±7.0b | 144.0±26.1d | 183.8±33.3de |

| 106-32-1 | Octanoic Acid Ethylester | 845.1±157.4e | 569.5±106.1de | 537.8±100.1d | 393.3±73.2cd | 174.5±32.5b | 116.6±21.7a | 108.1±20.1a | 137.9±25.7ab | 281.9±52.5c | 413.9±77.1d |

| 123-92-2 | Isoamyl Acetate | 100.4±18.2e | 62.9±11.4bcd | 108.2±19.7e | 56.9±10.3bc | 25.4±4.6a | 19.2±3.5a | 43.7±7.9b | 20.6±3.7a | 79.6±14.4cde | 82.8±15.0de |

| 123-66-0 | Ethylexanoate | 575.3±66.5f | 441.6±51.1e | 504.1±58.3ef | 350.2±40.5d | 152.7±17.7b | 128.2±14.8b | 92.4±10.7a | 101.0±11.7a | 227.7±26.3c | 296.7±34.3cd |

| 617-35-6 | Ethyl pyruvate | 735.7±7.4d | 823.7±8.2e | 901.3±9.0f | 683.8±6.8c | 741.6±7.4d | 1090.1±10.9g | 284.8±2.8b | 210.3±2.1a | 1135.5±11.4h | 2026.5±20.31i |

| 97-64-3 | Ethyl lactate | 7551.6±109.5f | 7602.0±110.2f | 5191.2±75.3e | 3937.0±57.1b | 4449.8±64.5c | 5143.5±74.6d | 3663.4±53.1b | 2376.8±34.5a | 10776.4±156.2g | 15012.7±217.6h |

| 5405-41-4 | Ethyl-3-hydroxy butanoate | n.d. | 54.7±5.6d | 32.5±3.3b | 26.2±2.7a | 32.1±3.3ab | 34.9±3.6b | n.d. | n.d. | 47.9±4.9c | 54.3±5.6d |

| 110-38-3 | Ethyl decanoate | 194.2 ±36.1g | 131.0±24.3f | 86.1±16.0e | 37.0±6.9c | 23.9±4.4b | 13.1±2.4a | 12.7±2.4a | 16.5±3.1b | 54.4±10.1d | 93.2±17.3ef |

| 123-25-1 | Diethyl succinate | 14348.0±3346.8 | 11410.7±2661.6bc | 12718.3±2966.7c | 9127.0±2129.0b | 9787.8±2283.1b | 11714.0±2732.4c | 4225.3±985.6a | 4208.2±981.6a | 12465.4±2907.7c | 16969.8±1823.4 |

| 67233-91-4 | Ethyl-9-decenoate | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 8.2±2.0a | 7.5±1.8a | 11.8±2.9ab | 14.6±3.6b | 7.5±1.8a | 17.0±4.2b |

| 103-45-7 | Phenylethylacetate | 77.7±12.0e | 63.4±11.1de | 48.6±8.5cd | 36.0±6.3bc | 62.4±11.0de | 52.1±9.2d | 24.4±4.3a | 26.6±4.7ab | 50.0±8.8cd | 54.4±9.6d |

| 626-11-9 | Diethyl-DL-Malate | 8082.0±1205.2cd | 7451.9±1111.3b | 17044.7±2541.8f | 12292.8±1833.2e | 11033.1±1645.3de | 13616.2±2030.5ef | 5549.4±827.6a | 4503.6±671.6a | 7979.0±1189.9bc | 10753.4±1603.6d |

| 87-91-2 | (+)-Diethyl-L-Tartrate | 1555.3±351.6c | 2020.3±456.7cd | 3964.2±896.0e | 3064.2±692.6e | 1842.6±416.5c | 2290.8±517.8d | 840.5±190.0b | 511.4±115.6a | 1472.1±332.8c | 1592.0±359.8c |

| 1070-34-4 | Ethylhydrogensuccinate | 28759.4±5682.0cd | 17437.1±3445.1b | 27043.5±5343.0cd | 17528.8±3463.2b | 17693.8±3495.8b | 21445.7±4237.0c | 16577.6±3275.2b | 11962.3±2363.4a | 27545.3±5442.1cd | 32455.5±5412.2d |

| 3943-74-6 | Methylvanillate | n.d. | 3.0±0.3a | 5.2±0.3b | n.d. | 6.6±0.4c | 7.4±0.4c | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Terpenes | |||||||||||

| 98-55-5 | A-Terpineol | 4.9±0.4b | 5.4±0.5b | n.d. | n.d. | 3.8±0.3a | 3.5±0.3a | 14.5±1.3c | 12.8±1.1c | 37.9±3.4d | 53.2±4.7e |

| 14049-11-7 | Epoxylinalol R | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 3.3±0.1b | 2.5±0.1a | 7.7±0.3c | 10.8±0.4d |

| 14049-11-7 | Epoxylinalol S | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 11.4±0.4b | 8.1±0.3a | 23.4±0.8c | 32.7±1.1d |

| Lactones | |||||||||||

| 96-48-0 | Butyrolactone | 1407.2±18.0g | 1675.9±21.4h | 1359.8±17.4f | 1235.5±15.8d | 1287.1±16.4e | 1443.3±18.4g | 754.1±9.6b | 478.7±6.1a | 1143.5±14.6c | 1260.4±16.1de |

| 599-04-2 | Pantolactone | 68.0±11.9bcd | 92.3±16.1d | 74.2±13.0bcd | 57.8±10.1ab | 58.4±10.2ab | 61.8±10.8bc | 79.8±13.9cd | 45.3±7.9a | 65.6±11.5bcd | 70.2±12.3bcd |

| 1126-51-8 | γ-Carboethoxy-γ-Butyrolactone | 1952.8±127.7e | 2235.6±146.2e | 1708.8±111.7d | 1441.1±94.2c | 1497.7±97.9c | 1605.7±105.0d | 927.8±60.7b | 668.3±43.7a | 1687.2±110.3d | 1951.4±127.6e |

| Metoxyphenols | |||||||||||

| 2785-89-9 | p-Ethylguaiacol | n.d. | 3.7±1.4b | 4.3±1.6b | 3.5±1.3b | 4.1±1.6b | 3.8±1.5b | 2.1±0.8ab | 1.4±0.5a | 491.3±187.5d | 36.1±13.8c |

| 7786-61-0 | p-Vinylguaiacol | 84.1±4.4 b | 147.7±7.7f | 118.7±6.2d | 106.4±5.5c | 126.9±6.6e | 131.8±6.9e | 85.2±4.4b | 45.3±2.4a | 187.4±9.8g | 218.4±11.4h |

| 498-02-2 | Acetylguaiacol | 30.6±1.6c | 34.0±1.8c | 31.9±1.7c | 25.4±1.3b | 13.7±0.7a | 14.3±0.7a | 31.0±1.6c | 23.3±1.2b | 56.8±3.0d | 58.6±3.1d |

| Other | |||||||||||

| 513-86-0 | Acetoin | 386.8±24.3d | 1185.6±74.6e | 248.2±15.6bc | 242.5±15.3bc | 274.3±17.3c | 1587.4±99.9f | 170.6±10.7a | 381.2±24.0d | 237.2±14.9b | 1262.7±79.5e |

| 877-95-2 | N-(2-Phenylethyl)Acetamide | 136.2±6.2g | 150.6±6.8h | 99.0±4.5f | 82.7±3.7e | 51.2±2.3d | 50.8±2.3d | 19.0±0.9c | 13.6±0.6a | 16.9±0.8b | 16.6±0.8b |

| 121-33-5 | Vanillin | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 2.6±0.2a | 3.6±0.3b | n.d. | n.d. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).