Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

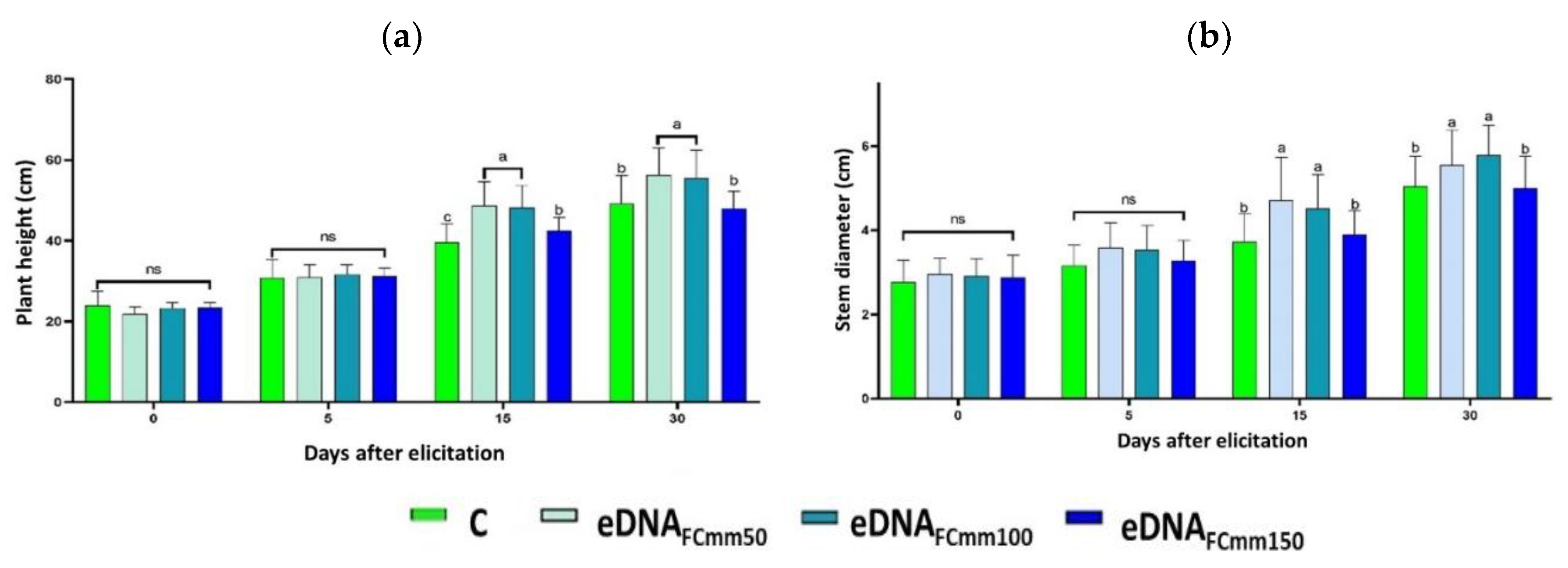

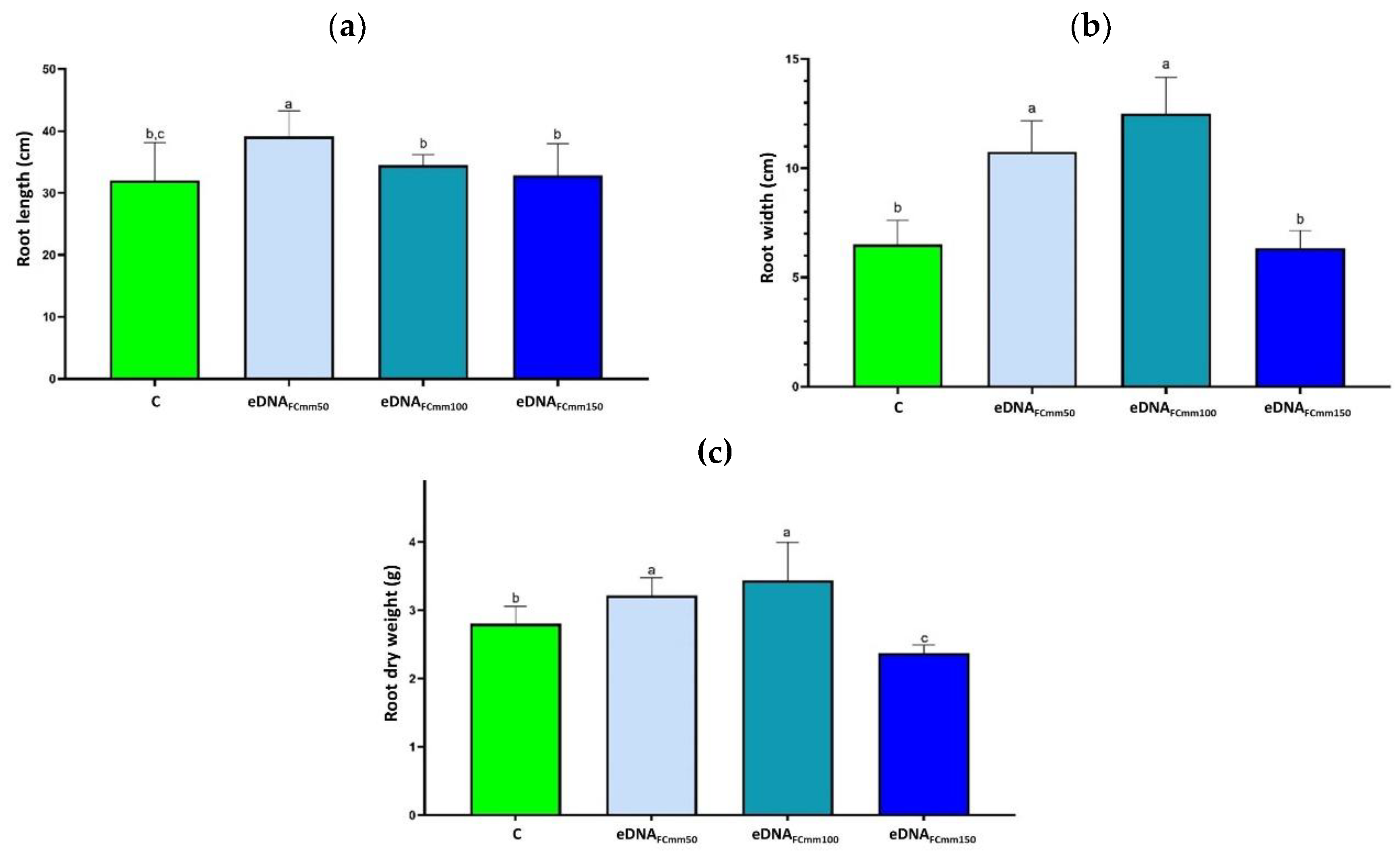

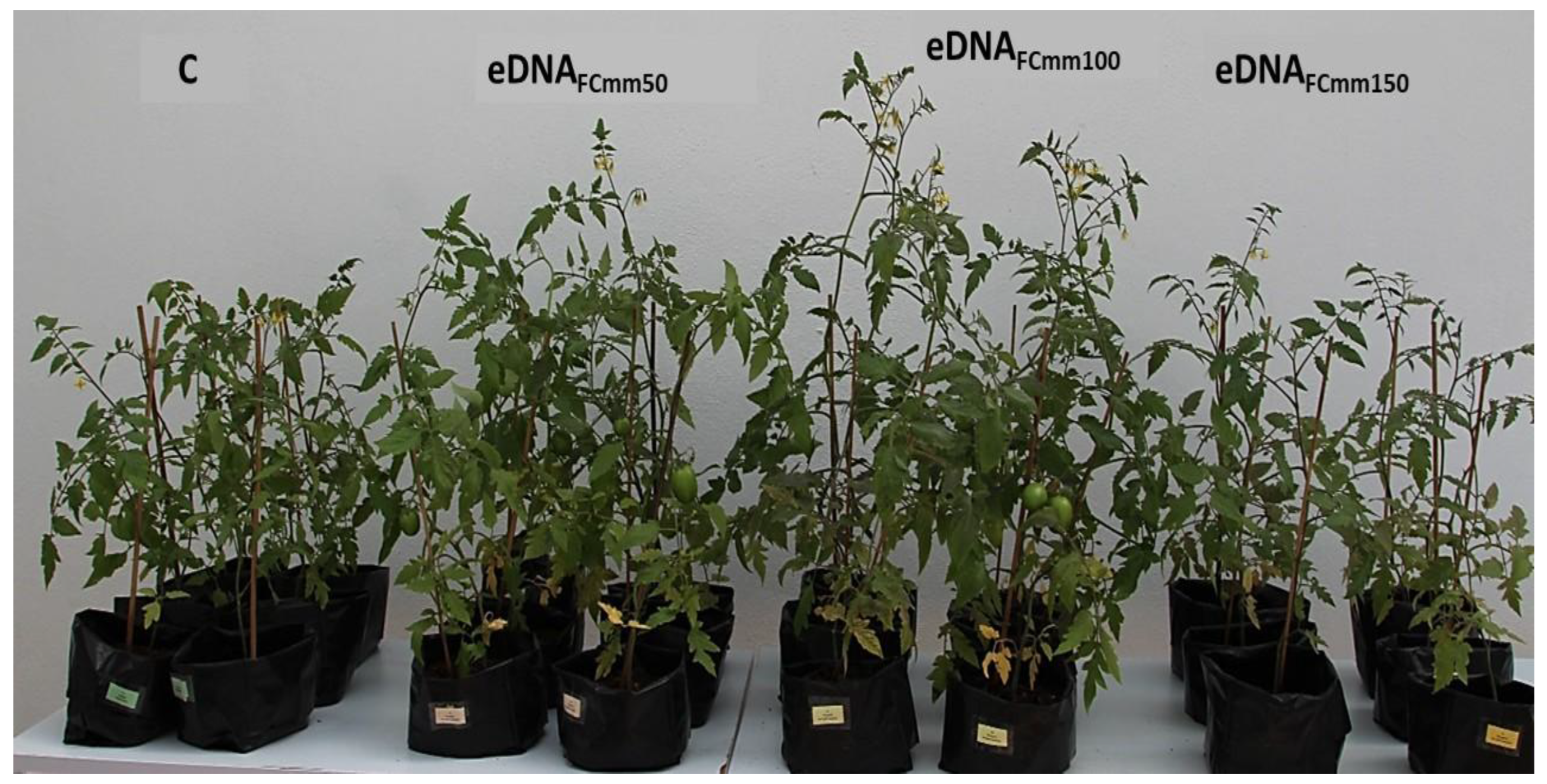

2.1. Effect of Applying eDNA Fragments from Cmm on Tomato Plants Morphological Variables

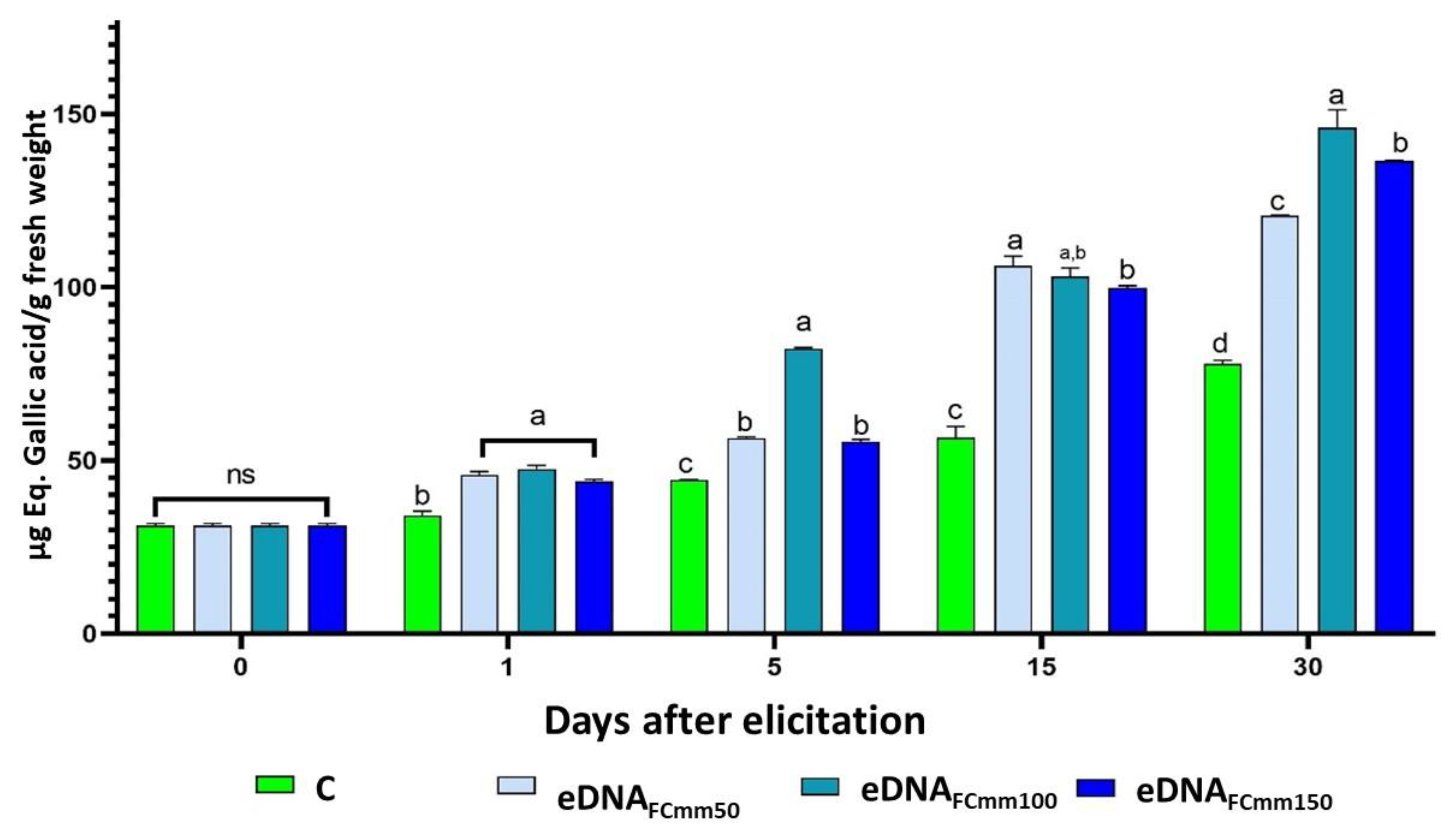

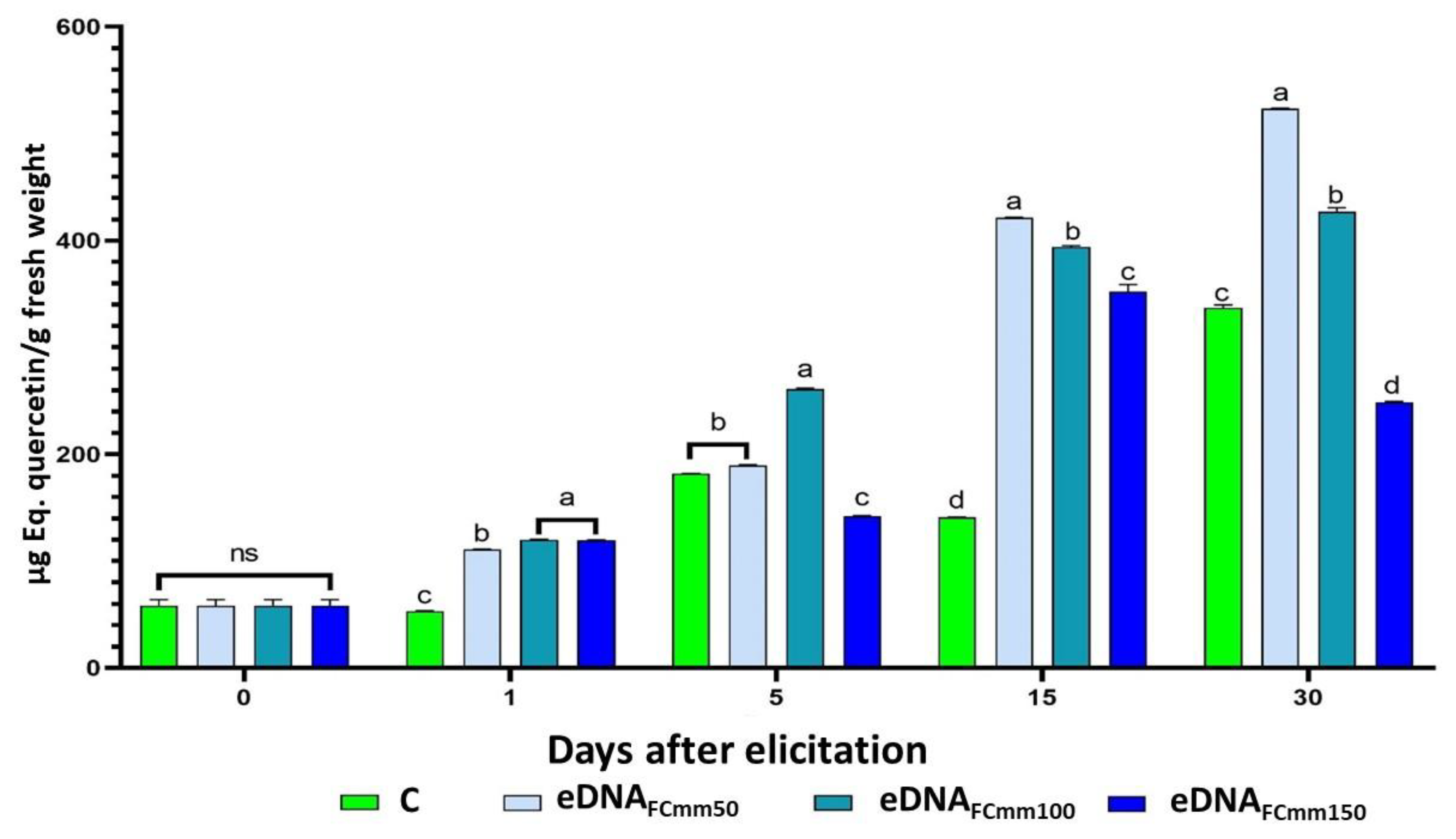

2.2. Total Phenol and Flavonoids Levels in Tomato Plants Treated with the eDNA Fragments from the Pathogen Cmm

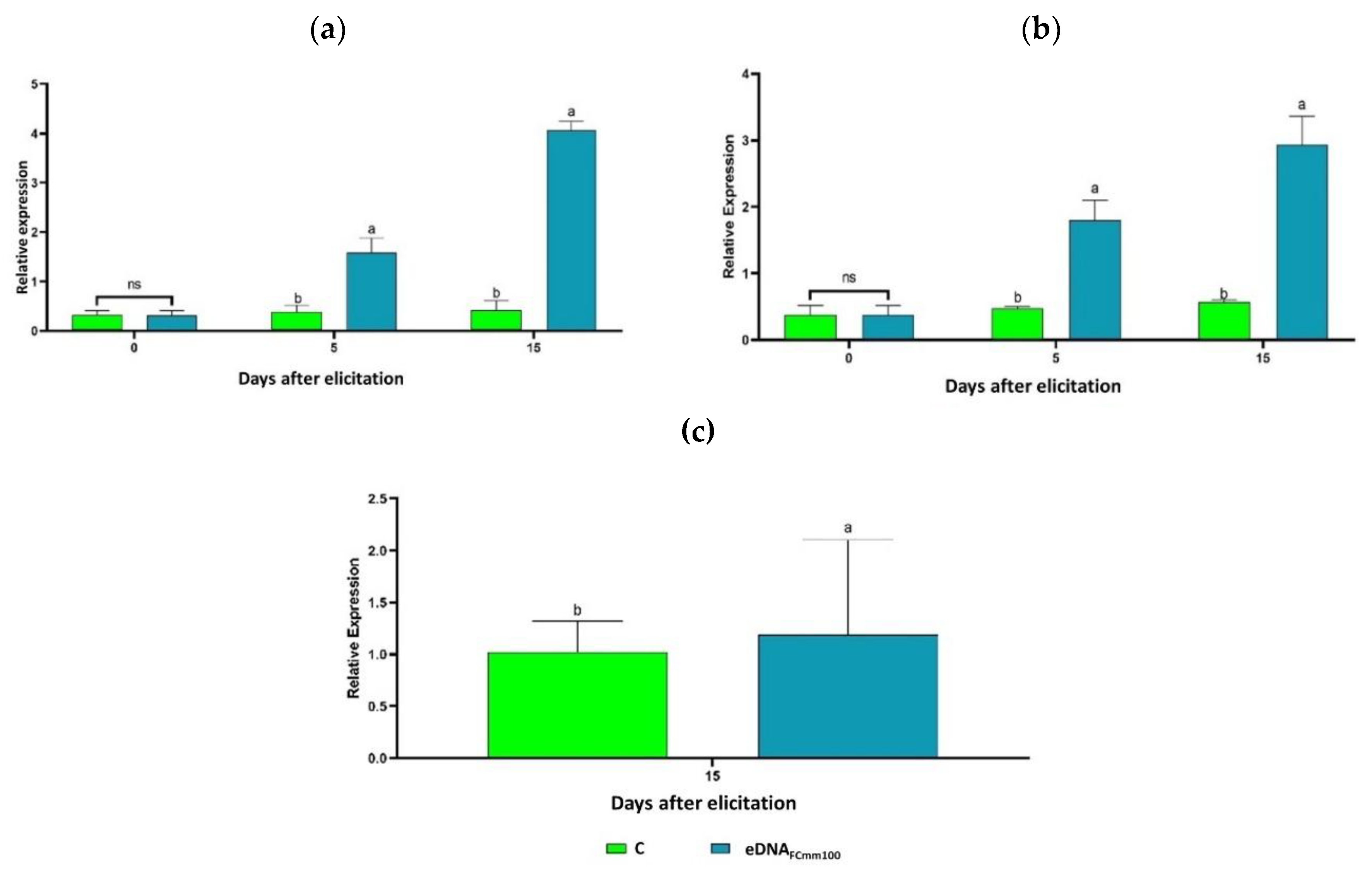

2.3. Analysis of Gene Expression-Associated to Stress Response in Tomato Plants Treated with the eDNA Fragments of Cmm

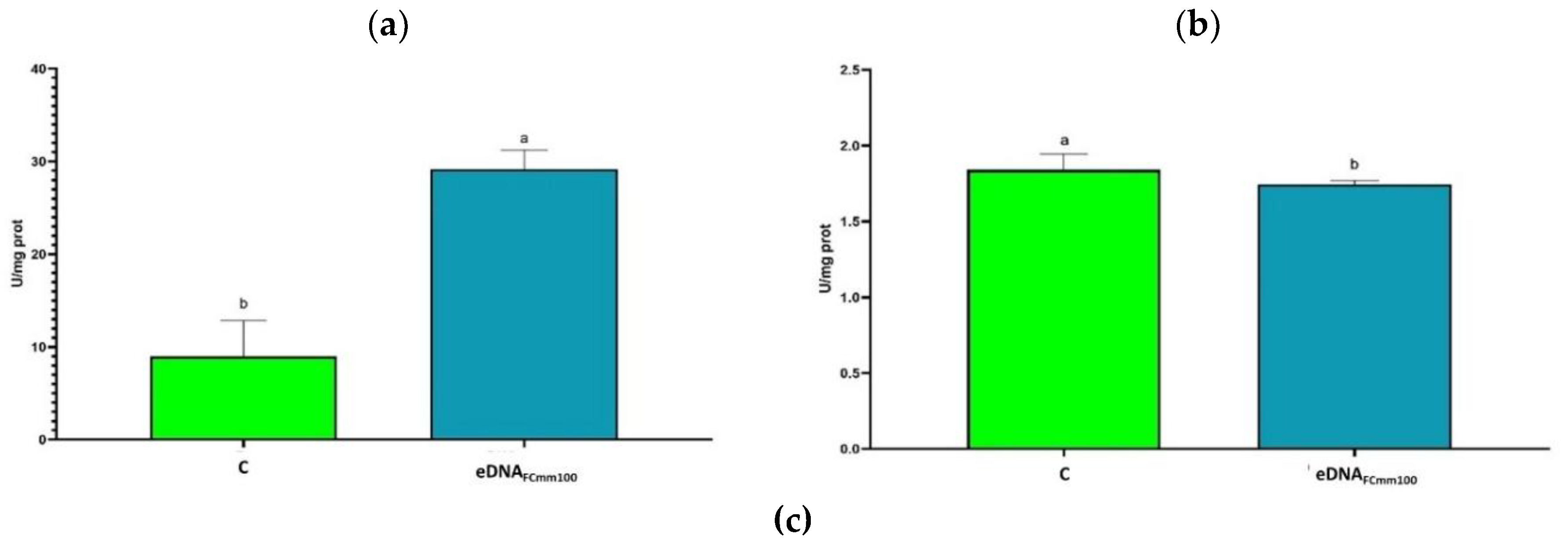

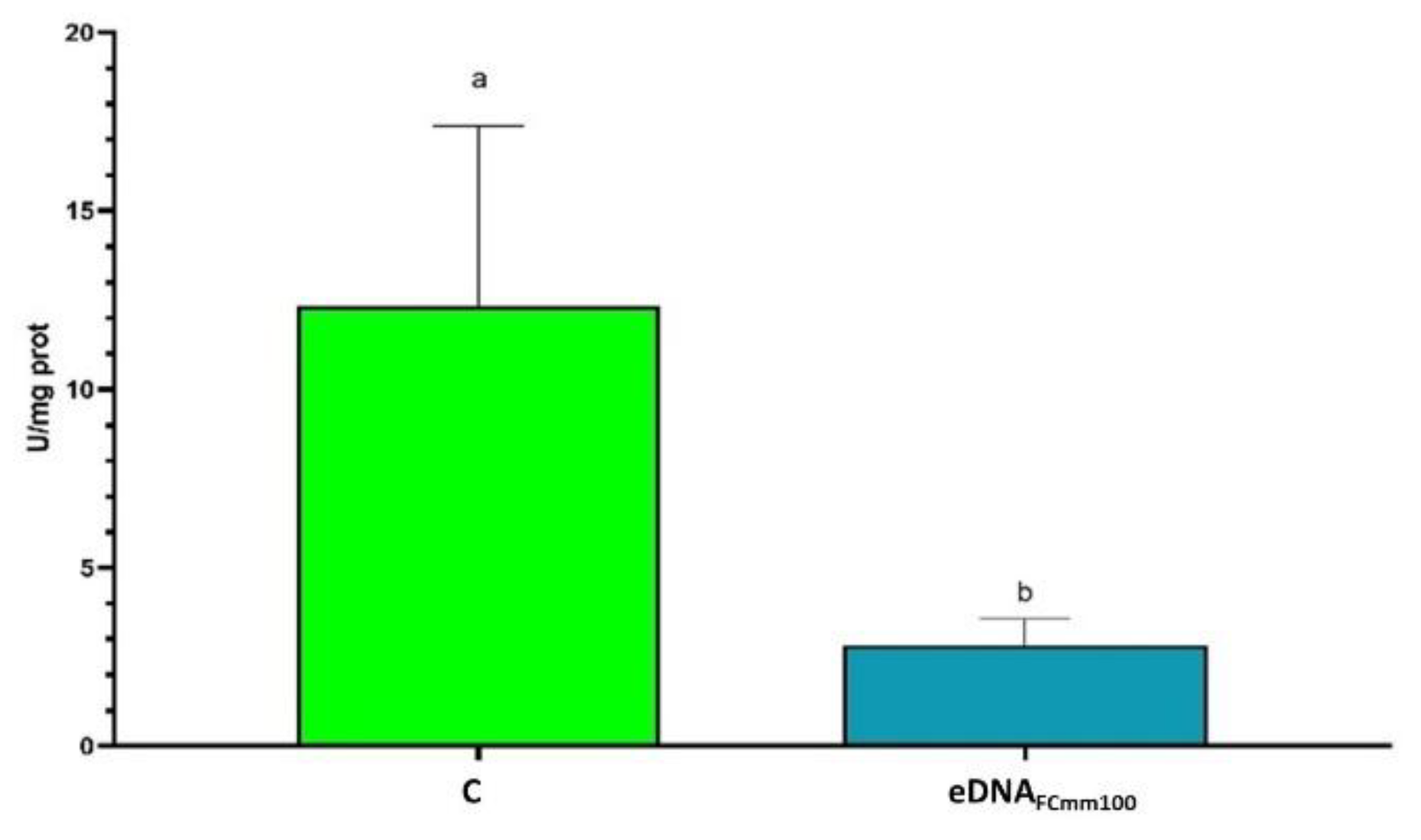

2.4. Analysis of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity in Tomato Plants Treated with eDNA Fragments of the Pathogen Cmm

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Biological Material

4.2. Extraction and Fragmentation of Genomic DNA from Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. Michiganenesis

4.3. Application of eDNA Fragments from the Pathogen Cmm to Tomato Plants (Plant Elicitation)

4.4. Meaasurement of Morphological Variables of Plants

4.5. Determination of Phenols and Total Flavonoids Content

4.6. Analysis of Gene Expression-Associated to Stress Response in Plants

4.7. Determination of Enzymatic Activity

4.7.1. Phenylalanine Ammonium-Lyase (PAL)

4.7.2. Catalase (CAT)

4.7.3. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAMP | Pathogen-associated molecular pattern |

| PTI | PAMP-triggered immunity |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| ROI | Reactive oxygen intermediatesLinear dichroism |

| ETI | Effector-triggered immunity |

| DAMP | Damage-associated molecular pattern |

| eDNA | Extracellular DNA |

References

- Lamers, J.; Der Meer; Van, T.; Testerink, C. How plants sense and respond to stressful environments. Plant Physiology 2020, 182, 1624–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thieffry, A.; López-Márquez, D.; Bornholdt, J.; Malekroudi, M. G.; Bressendorff, S.; Barghetti, A.; Sandelin, A.; Brodersen, P. PAMP-Triggered genetic reprogramming involves widespread alternative transcription initiation and an immediate transcription factor wave. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 2615–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, J. M. Plant immunity triggered by microbial molecular signatures. Molecular Plant 2010, 3, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFalco, T. A.; Zipfel, C. Molecular mechanisms of early plant pattern-triggered immune signaling. Molecular Cell 2021, 81, 3449–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, H.; Choi, S.; Cheng, M.; Koo, B. K.; Kim, E. Y.; Lee, H. S.; Lee, D. H. Flagellin sensing, signaling, and immune responses in plants. Plant Communications 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, T.; Inagaki, H.; Takai, R.; Hirai, H.; Che, F. S. Two distinct EF-Tu epitopes induce immune responses in rice and Arabidopsis. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2014, 27, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoleni, S.; Cartenì, F.; Bonanomi, G.; Senatore, M.; Termolino, P.; Giannino, F.; Incerti, G.; Rietkerk, M.; Lanzotti, V.; Chiusano, M. L. Inhibitory effects of extracellular self-DNA: A general biological process? New Phytologist 2015, 206, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Jamaica, L. M.; Villordo-Pineda, E.; González-Chavira, M. M.; Guevara-González, R. G.; Medina-Ramos, G. Effect of Fragmented DNA From Plant Pathogens on the Protection Against Wilt and Root Rot of Capsicum annuum L. Plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Hernández, A.; Carbajal-Valenzuela, I. A.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Rico-García, E.; Ocampo-Velazquez, R. V.; Feregrino-Pérez, A. A.; Guevara-Gonzalez, R. G. Extracellular DNA as a Strategy to Manage Vascular Wilt Caused by Fusarium oxysporum in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Based on Its Action as a Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern (DAMP) or Pathogen-Associated Molecular Pattern (PAMP). Plants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Scientia Horticulturae 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Génard, M.; Fishman, S.; Vercambre, G.; Huguet, J.-G.; Bussi, C.; Besset, J.; Habib, R. A biophysical analysis of stem and root diameter variations in woody plants. Plant Physiol 2001, 126, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Sun, H.; Bao, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Li, A.; Bai, Z.; Liu, L.; Li, C. Increasing root-lower characteristics improves drought tolerance in cotton cultivars at the seedling stage. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2024, 23, 2242–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, D. K.; John, E. A.; Beurskens, S.; Hutchings, M. J. Root system size and precision in nutrient foraging: responses to spatial pattern of nutrient supply in six herbaceous species. Journal of Ecology 2001, 89, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Ramírez, M.I.; García Trejo, J.F.; Caltzontzin Rabell, V.; Chávez Jaime, R.; Estrada Sánchez, M.L. Efecto de las condiciones de cultivo en la producción de fenoles, flavonoides totales y su capacidad antioxidante en el árnica (Heterotheca inuloides). Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas 2018, 9, 4296–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávalos, A.; Elena, G. Metabolismo secundario de plantas. Reduca Biología 2009, 2, 119–145. [Google Scholar]

- Carbajal-Valenzuela, I. A.; Guzmán-Cruz, R.; González-Chavira, M. M.; Medina-Ramos, G.; Serrano-Jamaica, L. M.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Vázquez, L.; Feregrino-Pérez, A. A.; Rico-García, E.; Guevara-González, R. G. Response of Plant Immunity Markers to Early and Late Application of Extracellular DNA from Different Sources in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Agriculture 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Macías, J. P.; García, Y. C.; Núñez, M.; Díaz, K.; Olea, A. F.; Espinoza, L. Plant growth-defense trade-offs: Molecular processes leading to physiological changes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godínez-Mendoza, P. L.; Rico-Chávez, A. K.; Ferrusquía-Jimenez, N. I.; Carbajal-Valenzuela, I. A.; Villagómez-Aranda, A. L.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Guevara-González, R. G. Plant hormesis: Revising of the concepts of biostimulation, elicitation and their application in a sustainable agricultural production. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 894, 164883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-García, E.; Ortega-Torres, A. E.; Verlinden, S.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Guevara-González, R. G. Respuesta en la fotosíntesis de jitomate (Solanum lycopersicum) elicitado para distinguir eustrés-distrés: primer acercamiento. CIENCIA Ergo-Sum 2024, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Biricolti, S.; Guidi, L.; Ferrini, F.; Fini, A.; Tattini, M. The biosynthesis of flavonoids is enhanced similarly by UV radiation and root zone salinity in L. vulgare leaves. Journal of Plant Physiology 2011, 168, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiusano, M. L.; Incerti, G.; Colantuono, C.; Termolino, P.; Palomba, E.; Monticolo, F.; Benvenuto, G.; Foscari, A.; Esposito, A.; Marti, L.; de Lorenzo, G.; Vega-Muñoz, I.; Heil, M.; Carteni, F.; Bonanomi, G.; Mazzoleni, S. Arabidopsis thaliana response to extracellular dna: Self versus nonself exposure. Plants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejía-Teniente, L.; Duran-Flores, F. de D.; Chapa-Oliver, A. M.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Cruz-Hernández, A.; González-Chavira, M. M.; Ocampo-Velázquez, R. V.; Guevara-González, R. G. Oxidative and molecular responses in capsicum annuum L. after hydrogen peroxide, salicylic acid and chitosan foliar applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2013, 14, 10178–10196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa Santos, M.; Cruz, L.; Norskov, P.; Rasmussen, O. F. A rapid and sensitive detection of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis in tomato seeds by polymerase chain reaction. Seed Sci y Technol. 1997, 25, 581–584. [Google Scholar]

- Porebski, S.; Bailey, L.G.; Baum, B.R. Modification of a CTAB DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant Mol Biol Rep 1997, 15, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, E.; Abu, S. K.; Lim, L. B. L. Phytochemical screening, total phenolics and antioxidant activities of bark and leaf extracts of Goniothalamus velutinus (Airy Shaw) from Brunei Darussalam. J. King Saud Univer. Sci. 2015, 27, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Calzada, T.; Qian, M.; Strid, Å; Neugart, S.; Schreiner, M.; Torres-Pacheco, I. Effect of UV-B radiation on morphology, phenolic compound production, gene expression, and subsequent drought stressresponses in chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Plant Physiol. Biochem 2019, 134, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, S.; Ferrante, A.; Leonardi, C.; Romano, D. PAL activities in asparagus spears during storage after ammonium sulfate treatments. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2018, 140, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afiyanti, M.; Chen, H.J. Catalase activity is modulated by calcium and calmodulin in detached mature leaves of sweet potato. J Plant Physiol 2014, 171, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide Dismutase: Improved Assays and an Assay Applicable to Acrylamide Gels. Analytical Biochemistry 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).