Submitted:

13 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Design

Study Setting and Sampling

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Data Collection

Data Analysis

Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Relevance for Clinical Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

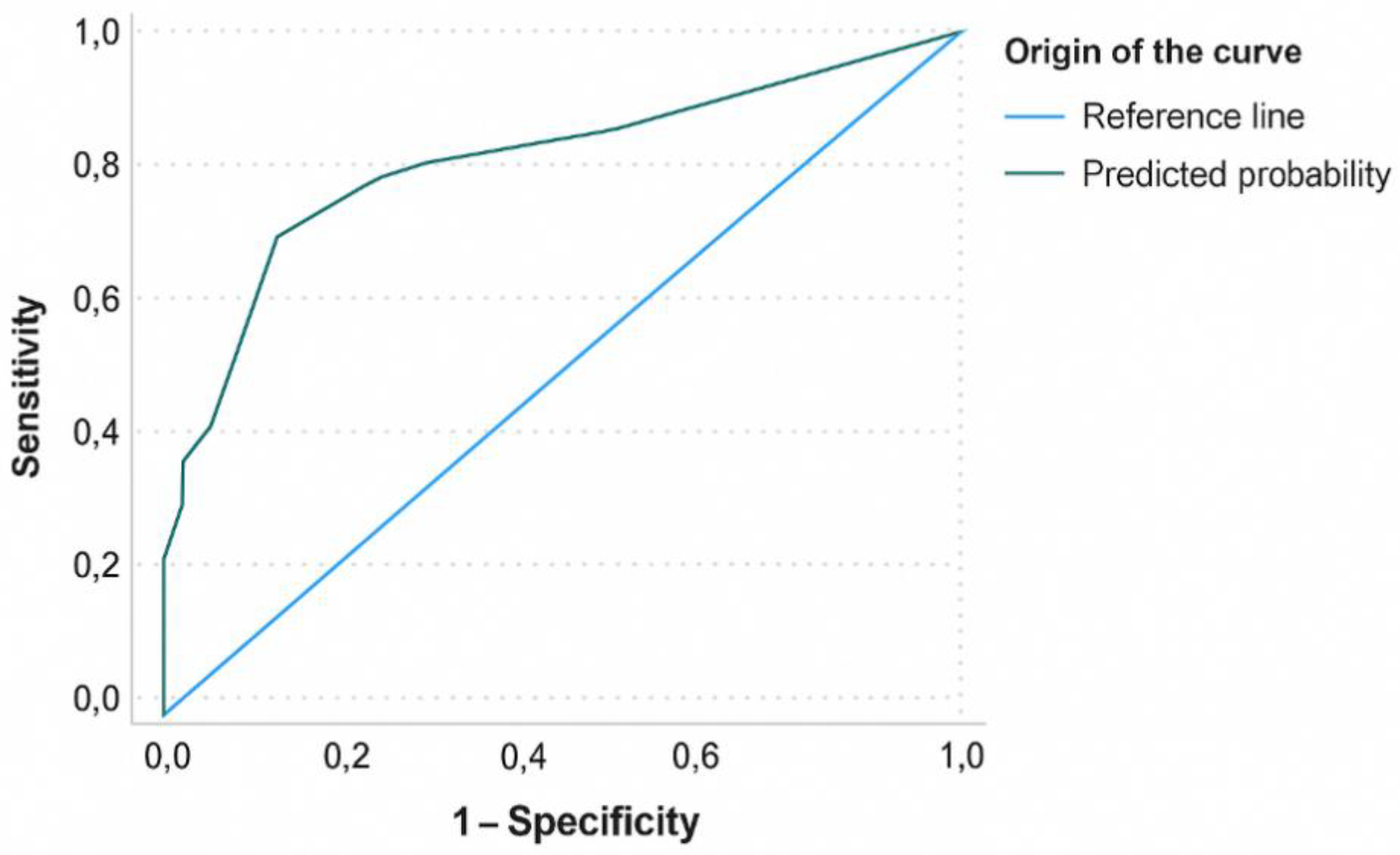

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision |

| MD | Mean Differences |

| MTS | Manchester Triage System |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Morandi, A.; Inzitari, M.; Udina, C.; Gual, N.; Mota, M.; Tassistro, E.; Andreano, A.; Cherubini, A.; Gentile, S.; Mossello, E.; et al. Visual and Hearing Impairment Are Associated With Delirium in Hospitalized Patients: Results of a Multisite Prevalence Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021, 22, 1162–1167.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, J.W.; Elhadad, N.; Mattison, M.L.P.; Nentwich, L.M.; Levine, S.A.; Marcantonio, E.R.; Kennedy, M. Boarding Duration in the Emergency Department and Inpatient Delirium and Severe Agitation. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2416343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaboli, A.; Sibilio, S.; Massar, M.; Brigiari, G.; Magnarelli, G.; Parodi, M.; Mian, M.; Pfeifer, N.; Brigo, F.; Turcato, G. Enhancing Triage Accuracy: The Influence of Nursing Education on Risk Prediction. Int Emerg Nurs 2024, 75, 101486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chary, A.N.; Bhananker, A.R.; Brickhouse, E.; Torres, B.; Santangelo, I.; Godwin, K.M.; Naik, A.D.; Carpenter, C.R.; Liu, S.W.; Kennedy, M. Implementation of Delirium Screening in the Emergency Department: A Qualitative Study with Early Adopters. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2024, 72, 3753–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarour, S.; Weiss, Y.; Kiselevich, Y.; Iacubovici, L.; Karol, D.; Shaylor, R.; Davydov, T.; Matot, I.; Cohen, B. The Association between Midazolam Premedication and Postoperative Delirium - a Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia 2024, 92, 111113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, C.R.; Hammouda, N.; Linton, E.A.; Doering, M.; Ohuabunwa, U.K.; Ko, K.J.; Hung, W.W.; Shah, M.N.; Lindquist, L.A.; Biese, K.; et al. Delirium Prevention, Detection, and Treatment in Emergency Medicine Settings: A Geriatric Emergency Care Applied Research (GEAR) Network Scoping Review and Consensus Statement. Acad Emerg Med 2021, 28, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skains, R.M.; Hayes, J.M.; Selman, K.; Zhang, Y.; Thatphet, P.; Toda, K.; Hayes, B.D.; Tayes, C.; Casey, M.F.; Moreton, E.; et al. Emergency Department Programs to Support Medication Safety in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2025, 8, e250814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaher-Sánchez, S.; Satústegui-Dordá, P.J.; Ramón-Arbués, E.; Santos-Sánchez, J.A.; Aguilón-Leiva, J.J.; Pérez-Calahorra, S.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Sufrate-Sorzano, T.; Angulo-Nalda, B.; Garrote-Cámara, M.E.; et al. The Management and Prevention of Delirium in Elderly Patients Hospitalised in Intensive Care Units: A Systematic Review. Nursing Reports 2024, 14, 3007–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Delirium Association. American Delirium Society The DSM-5 Criteria, Level of Arousal and Delirium Diagnosis: Inclusiveness Is Safer. BMC Med 2014, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Huraizi, A.R.; Al-Maqbali, J.S.; Al Farsi, R.S.; Al Zeedy, K.; Al-Saadi, T.; Al-Hamadani, N.; Al Alawi, A.M. Delirium and Its Association with Short- and Long-Term Health Outcomes in Medically Admitted Patients: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billig, A.E.; Lampert, M.A.; Guerra, R.R.; Steigleder, N.E. Delirium in the elderly admitted to an emergency hospital service. Rev Bras Enferm 2022, 75 Suppl 4, e20210054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler-Sanchis, A.; Martínez-Arnau, F.M.; Sánchez-Frutos, J.; Pérez-Ros, P. Clinical Risk Group as a Predictor of Mortality in Delirious Older Adults in the Emergency Department. Exp Gerontol 2023, 174, 112129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, K.; Deng, Y. The Effectiveness of a Modified Manchester Triage System for Geriatric Patients: A Retrospective Quantitative Study. Nurs Open 2024, 11, e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler-Sanchis, A.; Martínez-Arnau, F.M.; Sánchez-Frutos, J.; Pérez-Ros, P. Identification through the Manchester Triage System of the Older Population at Risk of Delirium: A Case-Control Study. J Clin Nurs 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Howard, M.A.; Han, J.H. Delirium and Delirium Prevention in the Emergency Department. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 2023, 39, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Angel, C.; Han, J.H. Succinct Approach to Delirium in the Emergency Department. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep 2021, 9, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Maclullich, A. Delirium in Older Adults. Medicine 2024, 52, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfichi, A.; Ceresa, I.F.; Piccioni, A.; Zanza, C.; Longhitano, Y.; Boudi, Z.; Esposito, C.; Savioli, G. A Lethal Combination of Delirium and Overcrowding in the Emergency Department. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 6587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, E.B.; Han, J.H.; Healy, H.; Kennedy, M.; Arendts, G.; Lee, J.; Carpenter, C.; Lee, S. Delirium Prevention and Treatment in the Emergency Department (ED): A Systematic Review Protocol. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Hirata, Y.; Kawahara, T.; Kawashima, M.; Sato, M.; Nakajima, J.; Anraku, M. Diagnosis of Respiratory Sarcopenia for Stratifying Postoperative Risk in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Surg 2025, 160, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, M.F.; Elder, N.M.; Fenn, A.; Niznik, J.; Khoujah, D.; Cole, J.B.; Cardon, Z.; Ding, M.; Goukasian, N.; Moreton, E.; et al. Comparative Safety of Medications for Severe Agitation: A Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines 2.0 Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2025, 73, 2893–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carayannopoulos, K.L.; Alshamsi, F.; Chaudhuri, D.; Spatafora, L.; Piticaru, J.; Campbell, K.; Alhazzani, W.; Lewis, K. Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Crit Care Med 2024, 52, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, D.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Paiva, C.E. Pharmacologic Management of End-of-Life Delirium: Translating Evidence into Practice. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, K.; Ping, X. The Efficacy and Safety of Haloperidol for the Treatment of Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1200314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Tseng, P.-T.; Tu, Y.-K.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Liang, C.-S.; Yeh, T.-C.; Chen, T.-Y.; Chu, C.-S.; Matsuoka, Y.J.; Stubbs, B.; et al. Association of Delirium Response and Safety of Pharmacological Interventions for the Management and Prevention of Delirium: A Network Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangani, C.; Giordano, B.; Stein, H.-C.; Bonora, S.; Ostinelli, E.G.; D’Agostino, A. Efficacy of Tiapride in the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review. Hum Psychopharmacol 2022, 37, e2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, N.J.; Wieruszewski, E.D.; Nei, A.M.; Mara, K.C.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Brown, C.S. Impact of Continuous Infusion Ketamine Compared to Continuous Infusion Benzodiazepines on Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit. J Intensive Care Med 2024, 39, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Hoeven, A.E.; Bijlenga, D.; van der Hoeven, E.; Schinkelshoek, M.S.; Hiemstra, F.W.; Kervezee, L.; van Westerloo, D.J.; Fronczek, R.; Lammers, G.J. Sleep in the Intensive and Intermediate Care Units: Exploring Related Factors of Delirium, Benzodiazepine Use and Mortality. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2024, 81, 103603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Ma, X.; Zhao, B.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, S. The Impact of Remimazolam Compared to Propofol on Postoperative Delirium: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Minerva Anestesiol 2025, 91, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, E.L.; Smalley, C.M.; Muir, M.; Mangira, C.M.; Pence, R.; Wahi-Singh, B.; Delgado, F.; Fertel, B.S. Agitation Management in the Emergency Department with Physical Restraints: Where Do These Patients End Up? West J Emerg Med 2023, 24, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.M.; Dewey, B.N.; Jarrell, D.H.; Vadiei, N.; Patanwala, A.E. Comparison of Phenobarbital-Adjunct versus Benzodiazepine-Only Approach for Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2019, 37, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, N.; Bazo-Alvarez, J.C.; Koopmans, M.; West, E.; Sampson, E.L. Understanding the Association between Pain and Delirium in Older Hospital Inpatients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, A.Y.; Edginton, S.; Lee, L.A.; Jaworska, N.; Burry, L.; Fiest, K.M.; Doig, C.J.; Niven, D.J. The Association between Pain, Analgesia, and Delirium among Critically Ill Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Intensive Care Med 2025, 51, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, A.; Guarino, M.; Serra, S.; Spampinato, M.D.; Vanni, S.; Shiffer, D.; Voza, A.; Fabbri, A.; De Iaco, F. Study and Research Center of the Italian Society of Emergency Medicine Narrative Review: Low-Dose Ketamine for Pain Management. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, B.; Zhou, S.; Li, J.; Wan, L.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, Y. Risk of Drug-Induced Delirium in Older Patients- a Pharmacovigilance Study of FDA Adverse Event Reporting System Database. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2025, 24, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Hospitalisation | Total | OR (95% CI) | P value2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 91)1 | No (n = 62)1 | (n=153)1 | |||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 83.82 (7.76) | 84.35 (7.60) | 84.04 (7.68) | — | 0.605 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 50.5 (46) | 50 (31) | 50.3 (77) | 0.97 (0.51-1.86) | 0.947 |

| Female | 49.5 (45) | 50 (31) | 49.7 (76) | ||

| MTS priority | |||||

| Priority IV (standard) | 25.3 (23) | 40.3 (25) | 31.4 (48) | 0.50 (0.25-1.00) | 0.049 |

| Priority III (urgent) | 68.1 (62) | 53.2 (33) | 62.1 (95) | 1.88 (0.96-3.65) | 0.062 |

| Priority II (very urgent) | 6.6 (6) | 6.5 (4) | 6.5 (10) | 1.02 (0.27-3.78) | 0.972 |

| MTS diagram | |||||

| Unwell adult | 51.6 (47) | 59.7 (37) | 54.9 (84) | — | 0.572 |

| Behaving strangely | 14.3 (13) | 16.1 (10) | 15.0 (23) | — | |

| Shortness of breath | 7.7 (7) | 9.7 (6) | 8.5 (13) | — | |

| Urinary problems | 3.3 (3) | 4.8 (3) | 3.9 (6) | — | |

| Mental illness | 2.2 (2) | 1.6 (1) | 2.0 (3) | — | |

| Limb problems | 13.2 (12) | 3.2 (2) | 9.2 (14) | — | |

| Abdominal pain | 4.4 (4) | 1.6 (1) | 3.3 (5) | — | |

| Infections | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | — | |

| Other | 2.2 (2) | 3.2 (2) | 2.6 (4) | — | |

| Clinical diagnosis | |||||

| No underlying disease | 35.2 (32) | 58.1 (36) | 44.4 (68) | — | 0.012 |

| Cardiac disease | 5.5 (5) | 0 (0) | 3.3 (5) | — | |

| Neurological disease | 7.7 (7) | 12.9 (8) | 9.8 (15) | — | |

| Renal disease | 11 (10) | 9.7 (6) | 10.5 (16) | — | |

| Respiratory disease | 5.5 (5) | 6.5 (4) | 5.9 (9) | — | |

| GI disease | 4.4 (4) | 3.2 (2) | 3.9 (6) | — | |

| Infection | 30.8 (28) | 9.7 (6) | 22.2 (34) | — | |

| Treatment | |||||

| ≥2 active ingredients | 73.6 (67) | 25.8 (16) | 54.2 (83) | 8.02 (3.84-16.74) | <0.001 |

| Total drugs, mean (SD) | 2.92 (2.02) | 0.95 (1.16) | 2.12 (1.98) | — | <0.001 |

| Analgesics | 67.0 (61) | 29 (18) | 51.6 (79) | 4.97 (2.46-10.02) | <0.001 |

| Antiemetics | 5.5 (5) | 0 | 3.3 (5) | 1.06 (1.00-1.11) | 0.061 |

| Antipsychotics | 40.7 (37) | 6.5 (4) | 26.8 (41) | 9.93 (3.32-29.73) | <0.001 |

| Benzodiazepines | 14.3 (13) | 3.2 (2) | 9.8 (15) | 5.00 (1.08-23.00) | 0.024 |

| Antibiotics | 47.3 (43) | 17.7 (11) | 35.3 (54) | 4.15 (1.92-8.97) | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroids | 8.8 (8) | 4.8 (3) | 7.2 (11) | 1.89 (0.48-7.44) | 0.353 |

| Antidepressants | 8.8 (8) | 0 | 5.2 (8) | 0.57 (0.49-0.65) | 0.016 |

| Antihypertensives | 2.2 (2) | 0 | 1.3 (2) | 0.58 (0.51-0.67) | 0.240 |

| Diuretics | 11.0 (10) | 3.2 (2) | 7.8 (12) | 3.07 (0.78-17.52) | 0.080 |

| Anti-ulcer drugs | 5.5 (5) | 1.6 (1) | 3.9 (6) | 3.54 (0.40-31.12) | 0.225 |

| Anticonvulsants | 4.4 (4) | 1.6 (1) | 3.3 (5) | 2.80 (0.30-25.71) | 0.342 |

| Antiarrhythmics | 2.2 (2) | 0 | 1.3 (2) | 0.58 (0.51-0.67) | 0.240 |

| Antidiabetics | 2.2 (2) | 1.6 (1) | 2.0 (3) | 1.37 (0.12-15.45) | 0.798 |

| Bronchodilators | 2.2 (2) | 3.2 (2) | 2.6 (4) | 0.67 (0.09-4.91) | 0.696 |

| Antiplatelets | 8.8 (8) | 0 | 5.2 (8) | 0.57 (0.49-0.65) | 0.016 |

| Others | 2.2 (2) | 3.2 (2) | 2.6 (4) | 0.67 (0.09-4.91) | 0.696 |

| Hospitalisation | Total | OR (95% CI) | P value2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 91)1 | No (n = 62)1 | (n=153)1 | |||

| Analgesics | 67.0 (61) | 29.0 (18) | 51.6 (79) | 4.97 (2.46-10.02) | <0.001 |

| Metamizole (≥ 2 g) | 11.0 (10) | 1.6 (1) | 7.2 (11) | 7.53 (0.93-60.42) | 0.028 |

| Paracetamol (≥ 1 g) | 53.8 (49) | 25.8 (16) | 42.5 (65) | 3.35 (1.66-6.77) | <0.001 |

| Dexketoprofen (≥ 50 mg) | 2.2 (2) | 1.6 (1) | 2.0 (3) | 1.37 (0.12-15.54) | 0.798 |

| Tramadol (≥ 100 mg) | 3.3 (3) | 1.6 (1) | 2.6 (4) | 2.08 (0.21-20.46) | 0.522 |

| Ketamine | 14.3 (13) | 4.8 (3) | 10.5 (16) | 3.27 (0.89-12.02) | 0.061 |

| < 50 mg | 14.3 (13) | 3.2 (2) | 9.8 (15) | — | 0.040 |

| ≥ 50 mg | 0 | 1.6 (1) | 0.7 (1) | — | 0.972 |

| Morphine | 6.6 (6) | 0 | 3.9 (6) | 0.57 (0.50-0.66) | 0.039 |

| < 50 mg | 5.5 (5) | 0 | 3.3 (5) | — | 0.167 |

| ≥ 50 mg | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | — | |

| Fentanyl (< 150 mg) | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | 0.59 (0.52-0.67) | 0.408 |

| Antipsychotics | 40.7 (37) | 6.5 (4) | 26.8 (41) | 9.93 (3.32-29.73) | <0.001 |

| Haloperidol | 20.9 (19) | 4.8 (3) | 14.4 (22) | 5.19 (1.46-18.39) | 0.006 |

| < 15 mg | 19.8 (18) | 4.8 (3) | 13.7 (21) | — | 0.020 |

| ≥ 15 mg | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | — | |

| Olanzapine | 2.2 (2) | 0 | 1.3 (2) | 0.59 (0.51-0.67) | 0.240 |

| < 15 mg | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | — | 0.501 |

| ≥ 15 mg | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | — | |

| Risperidone | 2.2 (2) | 0 | 1.3 (2) | 0.58 (0.51-0.67) | 0.240 |

| < 5 mg | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | — | 0.501 |

| ≥ 5 mg | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | — | |

| Tiapride | 19.8 (18) | 6.5 (4) | 14.4 (22) | 3.57 (1.14-11.14) | 0.021 |

| < 100 mg | 3.3 (3) | 0 | 2.0 (3) | — | 0.055 |

| ≥ 100 mg | 16.5 (15) | 6.5 (4) | 12.4 (19) | — | |

| Levomepromazine (≥ 125 mg) | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | 0.59 (0.51-0.67) | 0.408 |

| Benzodiazepines | 14.3 (13) | 3.2 (2) | 9.8 (15) | 5.00 (1.08-23.00) | 0.024 |

| Diazepam (≥ 5 mg) | 3.3 (3) | 1.6 (1) | 2.6 (4) | 2.08 (0.21-20.46) | 0.522 |

| Alprazolam (≥ 1 mg) | 2.2 (2) | 0 | 1.3 (2) | 0.58 (0.51-0.67) | 0.240 |

| Lorazepam (≥ 1 mg) | 2.2 (2) | 1.6 (1) | 2.0 (3) | 1.37 (0.12-15.45) | 0.798 |

| Midazolam | 4.4 (4) | 0 | 2.6 (4) | 0.58 (0.51-0.67) | 0.094 |

| < 3 mg | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | — | 0.247 |

| ≥ 3 mg | 3.3 (3) | 0 | 2.0 (3) | — | 0.024 |

| Clorazepate (≥ 10 mg) | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | 0.59 (0.51-0.67) | 0.408 |

| Bromazepam (≥ 1.5 mg) | 1.1 (1) | 0 | 0.7 (1) | 0.59 (0.51-0.67) | 0.408 |

| No underlying disease (n = 68) |

Heart disease (n = 5) |

Neurological disease (n = 15) |

Kidney disease (n = 16) | Respiratory disease (n = 9) |

GI disease (n = 6) |

Infection (n = 34) |

Total (n = 153) |

P value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesics | 39.7 (27) | 60.0 (3) | 33.3 (5) | 62.5 (10) | 55.6 (5) | 83.3 (5) | 70.6 (24) | 51.6 (79) | 0.028 |

| Antiemetics | 10.3 (7) | 40.0 (2) | 6.7 (1) | 25.0 (4) | 22.2 (2) | 33.3 (2) | 26.5 (9) | 17.6 (27) | 0.170 |

| Antipsychotics | 22.1 (15) | 60.0 (3) | 20.0 (3) | 25.0 (4) | 22.2 (2) | 16.7 (1) | 38.2 (13) | 26.8 (41) | 0.355 |

| Antibiotics | 0 | 80.0 (4) | 13.3 (2) | 68.8 (11) | 66.7 (6) | 33.3 (2) | 58.3 (29) | 35.3 (54) | <0.001 |

| Corticosteroids | 4.4 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.3 (3) | 0 | 14.7 (5) | 7.2 (11) | 0.013 |

| Antidepressants | 2.9 (2) | 20.0 (1) | 0 | 12.5 (2) | 0 | 0 | 8.8 (3) | 5.2 (8) | 0.306 |

| Antihypertensives | 1.5 (1) | 0 | 6.7 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 (2) | 0.639 |

| Diuretics | 1.5 (1) | 60.0 (3) | 0 | 12.5 (2) | 22.2 (2) | 16.7 (1) | 8.8 (3) | 7.8 (12) | <0.001 |

| Anti-ulcer drugs | 1.5 (1) | 0 | 6.7 (1) | 0 | 11.1 (1) | 33.3 (2) | 2.9 (1) | 3.9 (6) | 0.008 |

| Benzodiazepines | 10.3 (7) | 0 | 13.3 (2) | 12.5 (2) | 0 | 0 | 11.8 (4) | 9.8 (15) | 0.847 |

| Anticonvulsants | 2.9 (2) | 0 | 6.7 (1) | 6.3 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2.9 (1) | 3.3 (5) | 0.944 |

| Antiarrhythmics | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.3 (1) | 11.1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1.3 (2) | 0.076 |

| Antidiabetics | 1.5 (1) | 0 | 0 | 6.3 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2.9 (1) | 2.0 (3) | 0.870 |

| Bronchodilators | 1.5 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22.2 (2) | 2.9 (1) | 2.6 (4) | 0.020 |

| Antiplatelets | 1.5 (1) | 0 | 0 | 18.8 (3) | 0 | 16.7 (1) | 8.8 (3) | 5.2 (8) | 0.064 |

| Others | 2.9 (2) | 0 | 6.7 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.9 (1) | 2.6 (4) | 0.922 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).