Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

13 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

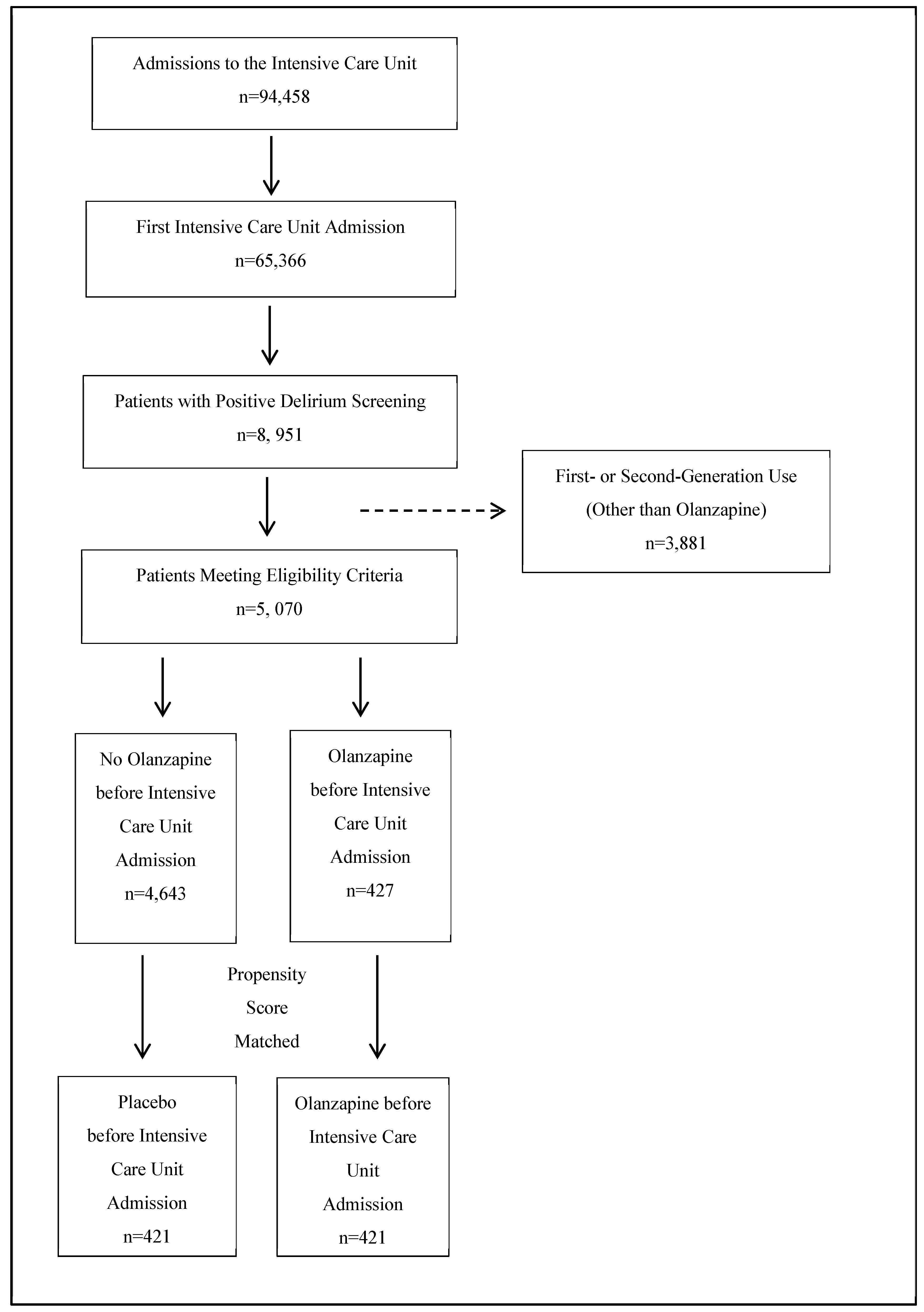

2.1. Participant Flow

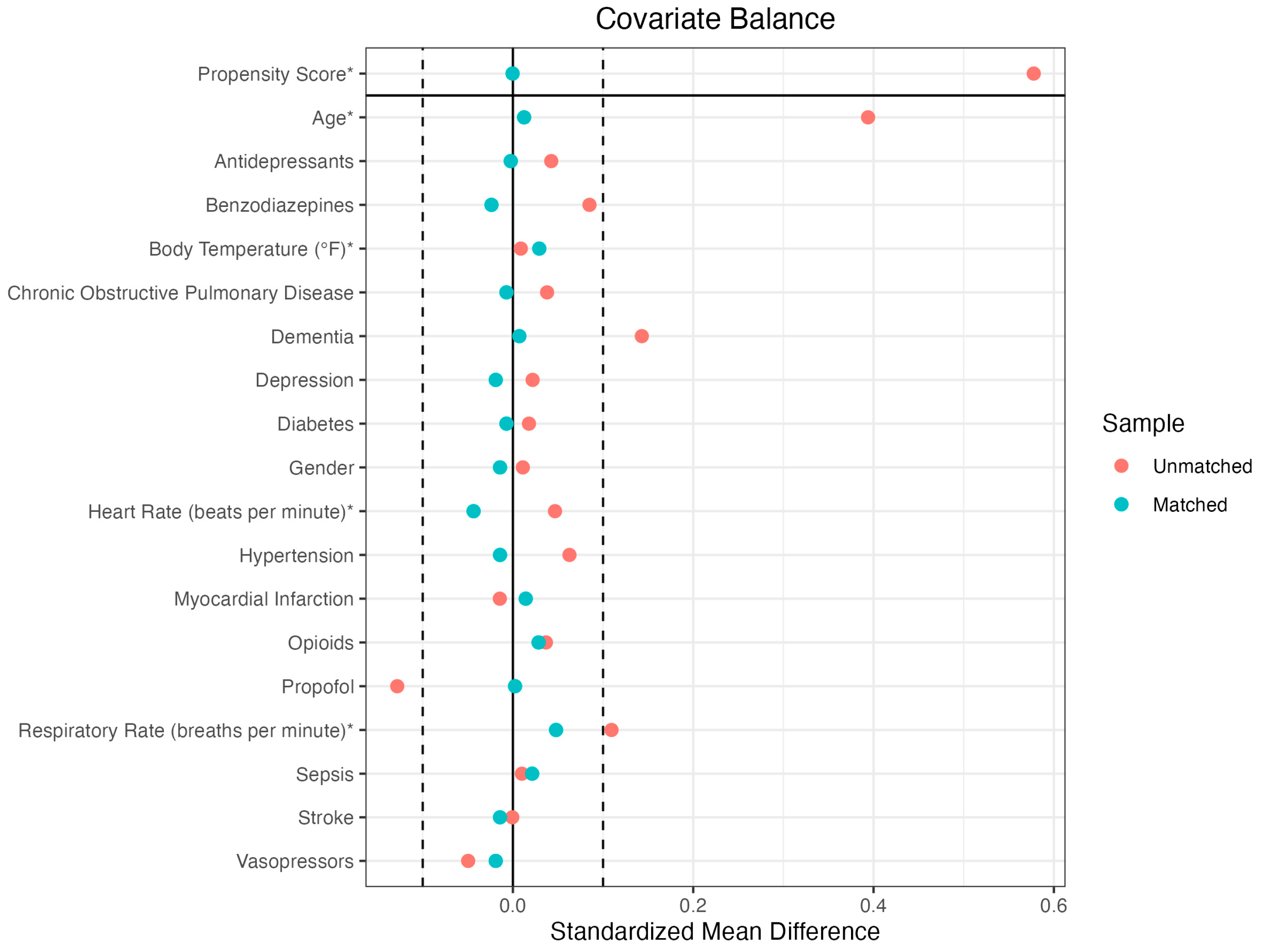

2.2. Propensity Score Matching

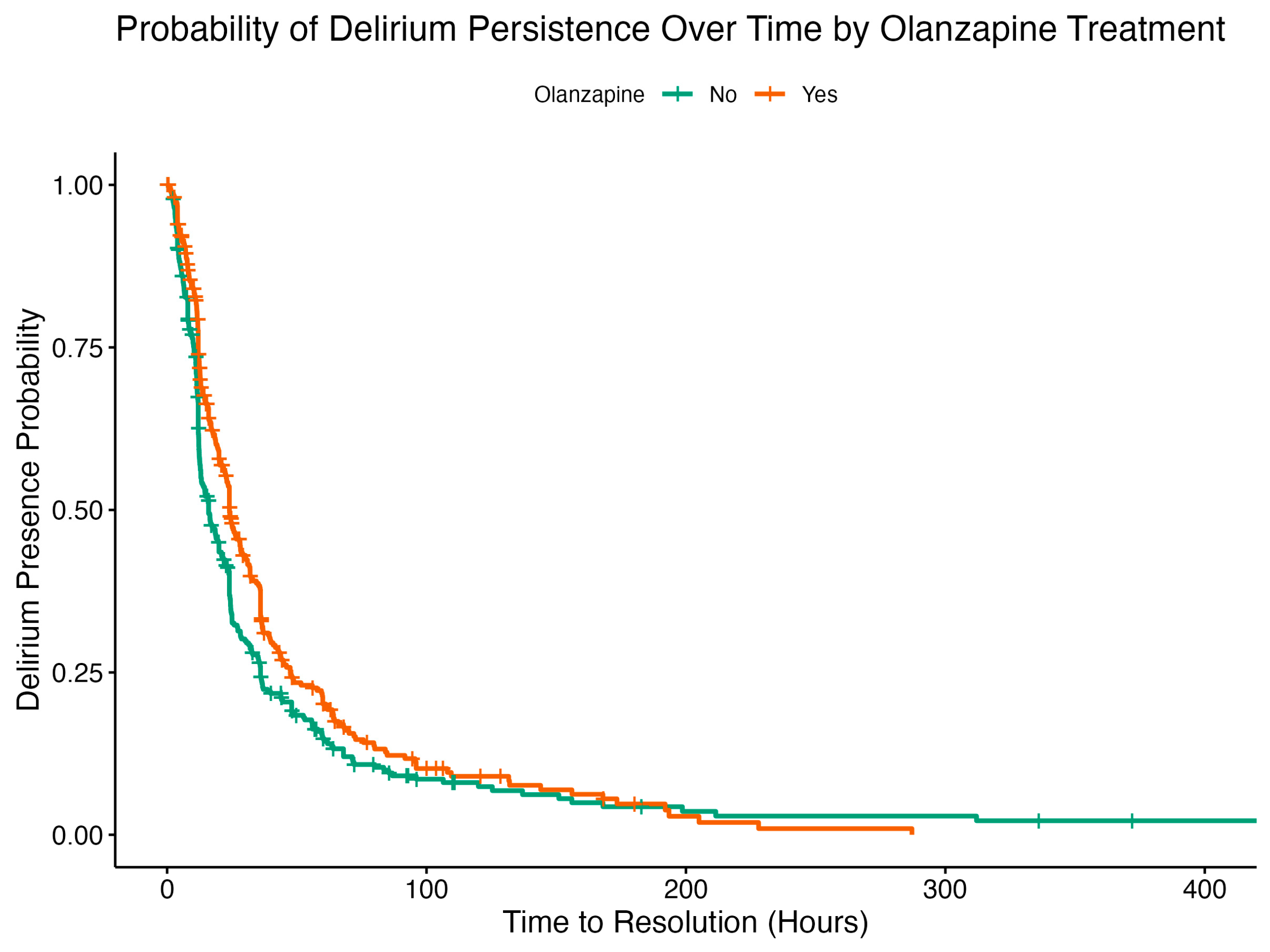

2.3. Cox Proportional Hazard Analysis

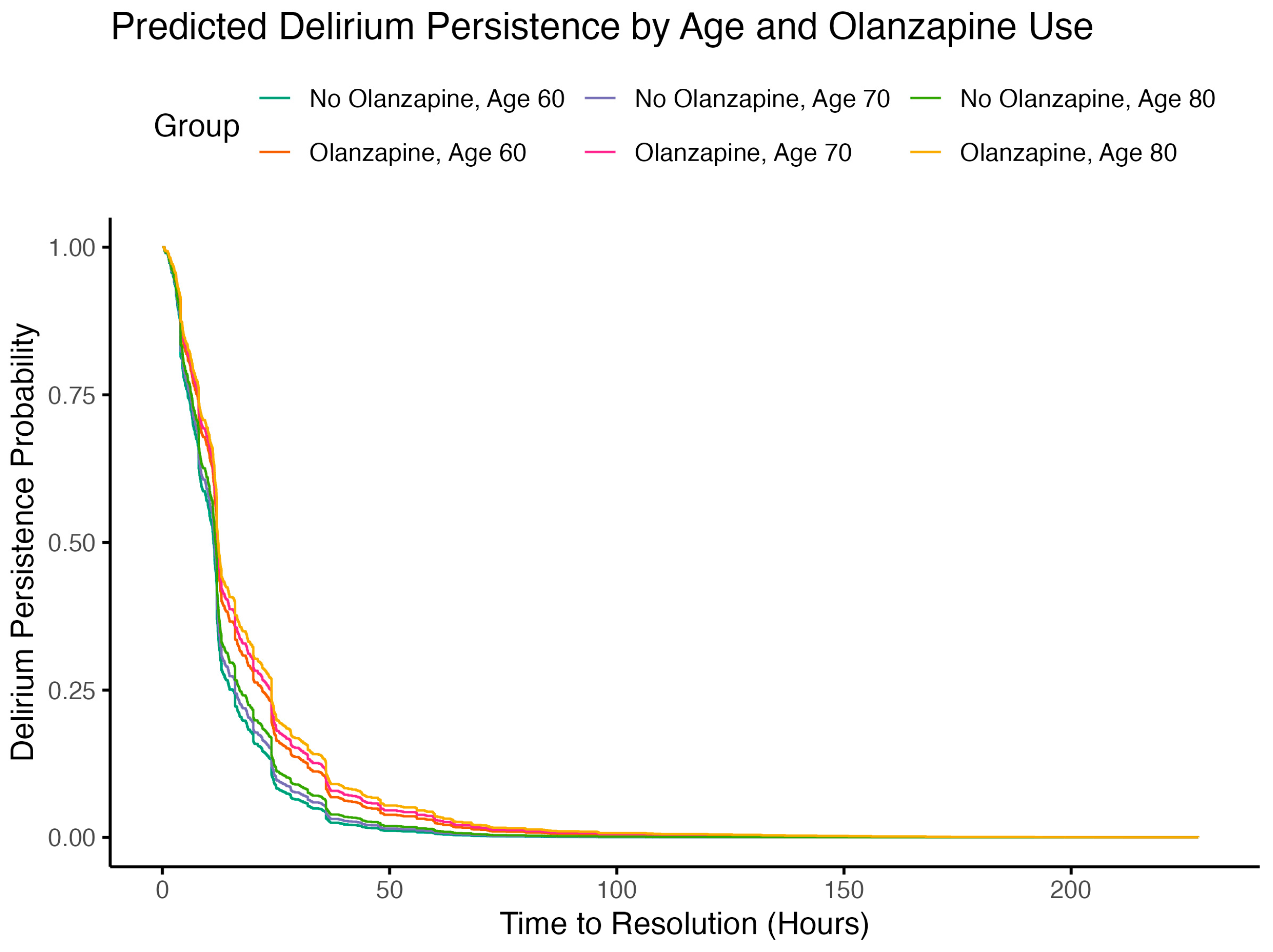

2.4. Subgroup Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Source

4.2. Study Design

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, S.V.; Law, T.J.; Needham, D.M. Long-Term Complications of Critical Care. Crit Care Med 2011, 39, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandharipande, P.P.; Girard, T.D.; Jackson, J.C.; Morandi, A.; Thompson, J.L.; Pun, B.T.; Brummel, N.E.; Hughes, C.G.; Vasilevskis, E.E.; Shintani, A.K.; et al. Long-Term Cognitive Impairment after Critical Illness. N Engl J Med 2013, 369, 1306–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, K.; Balas, M.C.; Stollings, J.L.; McNett, M.; Girard, T.D.; Chanques, G.; Kho, M.E.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Weinhouse, G.L.; Brummel, N.E.; et al. A Focused Update to the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Anxiety, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2025, 53, e711–e727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richelson, E. Receptor Pharmacology of Neuroleptics: Relation to Clinical Effects. J Clin Psychiatry 1999, 60 Suppl 10, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bymaster, F.P.; Calligaro, D.O.; Falcone, J.F.; Marsh, R.D.; Moore, N.A.; Tye, N.C.; Seeman, P.; Wong, D.T. Radioreceptor Binding Profile of the Atypical Antipsychotic Olanzapine. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996, 14, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

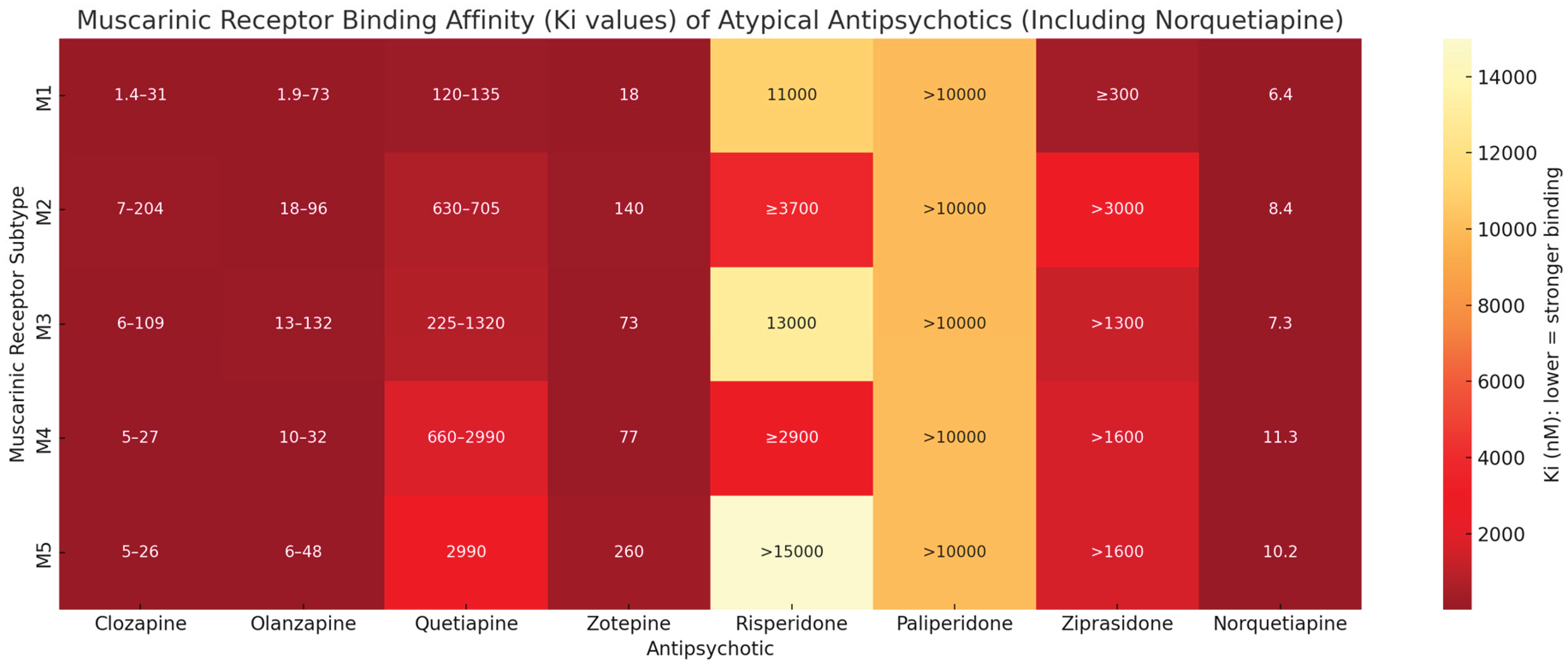

- Jensen, N.H.; Rodriguiz, R.M.; Caron, M.G.; Wetsel, W.C.; Rothman, R.B.; Roth, B.L. N-Desalkylquetiapine, a Potent Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor and Partial 5-HT1A Agonist, as a Putative Mediator of Quetiapine’s Antidepressant Activity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008, 33, 2303–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, Bryan L. PDSP Ki Database.

- Levey, A.I.; Edmunds, S.M.; Koliatsos, V.; Wiley, R.G.; Heilman, C.J. Expression of M1-M4 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor Proteins in Rat Hippocampus and Regulation by Cholinergic Innervation. J Neurosci 1995, 15, 4077–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinoe, T.; Matsui, M.; Taketo, M.M.; Manabe, T. Modulation of Synaptic Plasticity by Physiological Activation of M1 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors in the Mouse Hippocampus. J Neurosci 2005, 25, 11194–11200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wess, J. Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor Knockout Mice: Novel Phenotypes and Clinical Implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2004, 44, 423–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostaras, S.G.; Murphy, G.G.; Hamilton, S.E.; Mitchell, S.L.; Rahnama, N.P.; Nathanson, N.M.; Silva, A.J. Selective Cognitive Dysfunction in Acetylcholine M1 Muscarinic Receptor Mutant Mice. Nat Neurosci 2003, 6, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, C.J.; Watson, J.; Reavill, C. Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors as CNS Drug Targets. Pharmacol Ther 2008, 117, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Lamping, K.G.; Duttaroy, A.; Zhang, W.; Cui, Y.; Bymaster, F.P.; McKinzie, D.L.; Felder, C.C.; Deng, C.X.; Faraci, F.M.; et al. Cholinergic Dilation of Cerebral Blood Vessels Is Abolished in M(5) Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor Knockout Mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 14096–14101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugiani, O. Why Is Delirium More Frequent in the Elderly? Neurol Sci 2021, 42, 3491–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, C.G.; Boncyk, C.S.; Fedeles, B.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Chen, W.; Patel, M.B.; Brummel, N.E.; Jackson, J.C.; Raman, R.; Ely, E.W.; et al. Association between Cholinesterase Activity and Critical Illness Brain Dysfunction. Crit Care 2022, 26, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado, J.R. Delirium Pathophysiology: An Updated Hypothesis of the Etiology of Acute Brain Failure. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018, 33, 1428–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ely, E.W.; Margolin, R.; Francis, J.; May, L.; Truman, B.; Dittus, R.; Speroff, T.; Gautam, S.; Bernard, G.R.; Inouye, S.K. Evaluation of Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: Validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med 2001, 29, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, D.E.; Imai, K.; King, G.; Stuart, E.A. MatchIt: Nonparametric Preprocessing for Parametric Causal Inference. J. Stat. Soft. 2011, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grambsch, P.M.; Therneau, T.M. Proportional Hazards Tests and Diagnostics Based on Weighted Residuals. Biometrika 1994, 81, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BEFORE MATCHING | AFTER MATCHING | |||||

| Means Treated | Means Control | Standardized Mean Difference | Means Treated | Means Control | Standardized Mean Difference | |

| Propensity Score | 0.1145 | 0.0827 | 0.5036 | 0.1145 | 0.1144 | 0.0008 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | 72.9739 | 66.5803 | 0.4264 | 72.9739 | 72.8195 | 0.0103 |

| Gender | 0.2138 | 0.1713 | 0.1037 | 0.2138 | 0.2043 | 0.0232 |

| Medical Conditions | ||||||

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 0.1306 | 0.0927 | 0.1125 | 0.1306 | 0.152 | -0.0634 |

| Dementia | 0.247 | 0.104 | 0.3316 | 0.247 | 0.247 | 0 |

| Depression | 0.2067 | 0.1848 | 0.054 | 0.2067 | 0.1876 | 0.0469 |

| Diabetes | 0.3302 | 0.3123 | 0.0379 | 0.3302 | 0.3325 | -0.0051 |

| Hypertension | 0.5463 | 0.4836 | 0.126 | 0.5463 | 0.5487 | -0.0048 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 0.133 | 0.1475 | -0.0427 | 0.133 | 0.1686 | -0.1049 |

| Sepsis | 0.2518 | 0.2418 | 0.023 | 0.2518 | 0.2755 | -0.0547 |

| Stroke | 0.2043 | 0.205 | -0.0017 | 0.2043 | 0.1781 | 0.0648 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Antidepressants | 0.2138 | 0.1713 | 0.1037 | 0.2138 | 0.2043 | 0.0232 |

| Benzodiazepines | 90.304 | 89.2533 | 0.0499 | 90.304 | 92.3539 | -0.0973 |

| Propofol | 20.3183 | 19.6346 | 0.1105 | 20.3183 | 20.5701 | -0.0407 |

| Vasopressors | 98.2389 | 98.2224 | 0.011 | 98.2389 | 98.1964 | 0.0284 |

| Vitals | ||||||

| Heart Rate | 90.304 | 89.2533 | 0.0499 | 90.304 | 92.3539 | -0.0973 |

| Respiratory Rate | 20.3183 | 19.6346 | 0.1105 | 20.3183 | 20.5701 | -0.0407 |

| Body Temperature | 98.2389 | 98.2224 | 0.011 | 98.2389 | 98.1964 | 0.0284 |

| Term | Estimate | SE | Robust SE | Statistic | p.value | Confidence - Low | Confidence - High |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age | 0.9985 | 0.0011 | 0.0011 | -1.4209 | 0.1553 | 0.9963 | 1.0006 |

| Gender (F) | 0.8086 | 0.0865 | 0.0881 | -2.4111 | 0.0159 | 0.6803 | 0.9610 |

| Medications | |||||||

| Olanzapine | 0.7342 | 0.0832 | 0.0792 | -3.9005 | 0.0001 | 0.6287 | 0.8575 |

| Antidepressants | 0.8813 | 0.1086 | 0.0934 | -1.3525 | 0.1762 | 0.7338 | 1.0584 |

| Benzodiazepines | 0.9023 | 0.0888 | 0.0871 | -1.1802 | 0.2379 | 0.7606 | 1.0703 |

| Propofol | 0.6030 | 0.0962 | 0.0909 | -5.5614 | 0.0000 | 0.5046 | 0.7207 |

| Vasopressors | 0.7571 | 0.1020 | 0.0964 | -2.8872 | 0.0039 | 0.6268 | 0.9145 |

| Vitals | |||||||

| Heart Rate | 0.9971 | 0.0021 | 0.0020 | -1.4751 | 0.1402 | 0.9933 | 1.0010 |

| Respiratory Rate | 0.9882 | 0.0075 | 0.0078 | -1.5135 | 0.1301 | 0.9732 | 1.0035 |

| Body Temperature | 0.9978 | 0.0317 | 0.0312 | -0.0693 | 0.9447 | 0.9387 | 1.0607 |

| Medical Conditions | |||||||

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 0.9984 | 0.1230 | 0.1278 | -0.0122 | 0.9903 | 0.7772 | 1.2827 |

| Dementia | 0.8108 | 0.1122 | 0.1096 | -1.9137 | 0.0557 | 0.6541 | 1.0051 |

| Depression | 1.0512 | 0.1085 | 0.0949 | 0.5257 | 0.5991 | 0.8727 | 1.2662 |

| Diabetes | 0.8728 | 0.0903 | 0.0837 | -1.6259 | 0.1040 | 0.7407 | 1.0284 |

| Hypertension | 0.9752 | 0.0846 | 0.0812 | -0.3089 | 0.7574 | 0.8317 | 1.1435 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 1.0104 | 0.1379 | 0.1351 | 0.0765 | 0.9390 | 0.7754 | 1.3166 |

| Sepsis | 0.7070 | 0.1115 | 0.1112 | -3.1188 | 0.0018 | 0.5686 | 0.8791 |

| Stroke | 0.7668 | 0.1045 | 0.1015 | -2.6148 | 0.0089 | 0.6284 | 0.9357 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).