1. Introduction

Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), offers significant potential for automating information-intensive tasks in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) sector. Recent studies show that LLMs can support design reasoning, regulatory querying, document interpretation, construction scheduling, and administrative tasks without requiring programming expertise [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. LLM-enabled workflows therefore lower the digital-skill barrier and facilitate broader adoption of AI tools among practitioners.

Despite these advances, construction cost code verification remains largely untouched by LLM-based assistance. In Vietnam, verification is legally mandatory for all state-funded construction projects and plays a central role in design approval, procurement, payment appraisal, and public investment governance. The process requires verifying hundreds or thousands of bill-of-quantity items, checking the correctness of work-item codes, confirming units of measurement, and validating material - labour - machinery (MTR - LBR - MCR) price components. Prior research highlights the semantic ambiguity, procedural complexity, and high human-error rate inherent in cost checking [

6,

7].

In practice, many inconsistencies arise from simple human mistakes: mis-typed or outdated codes, copy - paste errors, incorrect units of measurement (UoMs), or manual adjustments to price components without updating the corresponding code. Because the cost code determines both the normative UoM and the MTR - LBR - MCR structure, a single incorrect code can propagate errors throughout the verification workflow. Identifying the intended code becomes especially difficult in large spreadsheets where mis-entries may go unnoticed.

These challenges underscore that effective verification requires not only deterministic rule checking but also mechanisms for recognising mis-typed or mis-assigned codes. Crucially, however, any such mechanism must remain strictly deterministic, reproducible, and grounded in normative datasets to satisfy auditability requirements in public-sector workflows. Unlike many LLM applications that rely on semantic interpretation or similarity-based retrieval, cost verification in the Vietnamese regulatory context permits only rule-governed operations and exact numerical comparison.

To address this constraint, we developed a GPT-based assistant that functions strictly as a controlled rule-execution engine rather than an open-ended generative model. Embedded within the GPT environment, the assistant executes the verification sequence (code lookup, UoM checking, price comparison) using strictly Python-based operations. This approach explicitly prohibits semantic inference or approximate matching. In cases where a project item’s code fails to match any UPB entry, the assistant performs an exact-match comparison of the UoM and full MTR - LBR - MCR price vector against all normative items. Only when a perfect numerical match is found does the system identify the corresponding normative code; otherwise, the item is conservatively classified as TT (non-listed), consistent with professional practice.

Against this backdrop, the study applies an Action Research methodology to co-develop, test, and refine a deterministic GPT-based assistant tailored to Vietnam’s cost-verification environment. The study pursues three objectives:

examine the semantic, procedural, and computational challenges that shape current verification workflows, focusing on the dominance of code-related errors and the limitations of existing software tools;

design and iteratively refine a GPT-based assistant that operationalises verification rules through deterministic Python-executed logic, including exact-match diagnostics for identifying mis-typed or mis-assigned code; and

establish a transparent, audit-ready framework for LLM-supported verification, demonstrating how LLMs can be constrained to behave as dependable rule-execution systems rather than probabilistic inference engines.

This study departs from prior LLM applications in the AEC domain by demonstrating that LLMs, when tightly controlled through system prompts, guardrails, and Python-executed computations, can perform compliance-critical verification tasks with full transparency and reproducibility. As elaborated in

Section 4.2, the selected system architecture—the GPT Code Interpreter combined with structured UPB datasets—enables deterministic rule execution without relying on semantic interpretation or similarity-based reasoning. This approach ensures that the assistant remains aligned with regulatory expectations while offering a replicable framework for integrating AI tools into public-sector cost management.

2. Background

2.1. Regulatory Context and the Practice of Cost Verification in Vietnam

Cost estimation and verification in state-funded projects Vietnam are governed by a comprehensive legal framework, including the Law on Construction (No 50/2015/QH13 [

8] and its amended version No 62/2020/QH14 [

9]), Decree 10/2021/ND-CP [

10], Circulars 11/2021/TT-BXD [

11], 12/2021/TT-BXD [

12] and 09/2024/TT-BXD [

13]. For most publicly financed projects, verification is mandatory prior to budget appraisal and design approval, serving as a compliance mechanism to ensure that item descriptions, UoM, and MTR - LBR - MCR unit prices align with provincial Unit Price Books (UPBs).

In practice, the verification process begins with validating the work-item code because it determines the legally valid UoM and normative price components required for direct cost appraisal. Only after a code is confirmed as valid can UoM and unit-price checks be meaningfully performed. However, because UPBs cannot cover every possible work item, some project-specific tasks may be classified as TT (non-listed) items. These cases require evaluators to determine whether the item is genuinely non-listed or the result of an incorrectly selected or mis-entered code. This inherently increases the cognitive burden of verification.

Vietnam’s reliance on detailed normative datasets, combined with manual spreadsheet-based workflows, makes cost verification both labour-intensive and error-prone, particularly when hundreds or thousands of items must be processed. The accuracy of direct costs significantly affects downstream components - indirect costs, pre-taxable income, and value-added tax - reinforcing the importance of reliable code checking early in the appraisal process.

2.2. Nature of Direct Cost Verification Workflows

Construction estimate verification primarily focuses on direct costs, as other major cost components are calculated as percentages of the direct cost, with the exception of a few minor special costs [

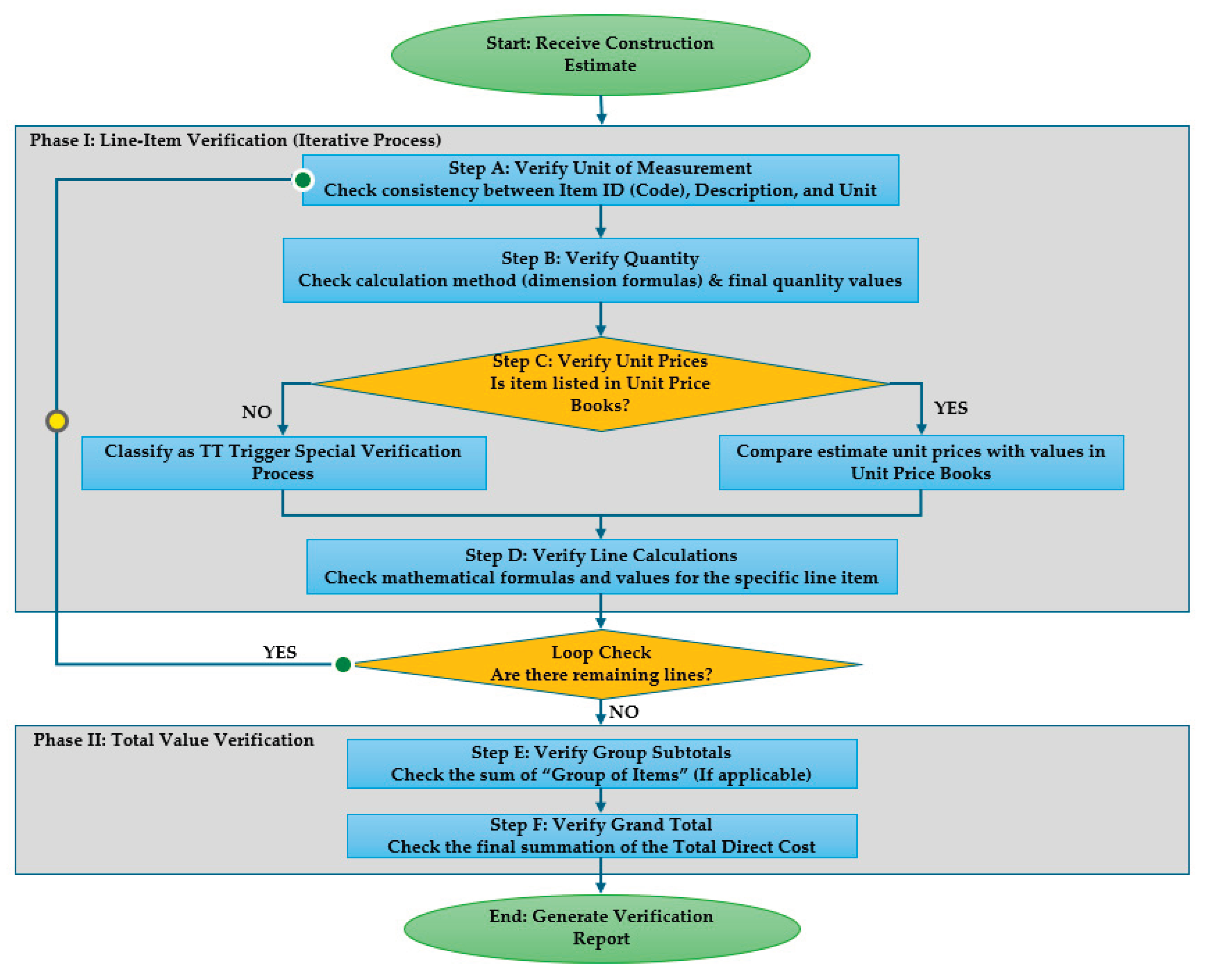

11]. The verification of direct costs is conducted in two main phases: line-item verification and total value verification. In Vietnam, construction estimates - whether generated by specialized software or otherwise - are consistently presented in Microsoft Excel spreadsheet format. Line-item verification begins by validating the unit of measurement against the item code and description, followed by checking calculation methods and construction quantities. Subsequently, the unit price for each item code is cross-referenced with the corresponding value in the official unit price books. Items not listed in these books are classified as TT (non-listed or provisional items) and undergo a separate verification procedure. Mathematical calculations for individual lines and work groups are verified for both formula accuracy and numerical values until all line items are processed. Finally, the verification extends to the total values, including subtotals for item groups (if applicable) and the grand total of the direct cost estimate. The resulting verification report must detail any discrepancies regarding item codes, descriptions, units of measurement, unit prices, line or group calculations, and total values (

Figure 1).

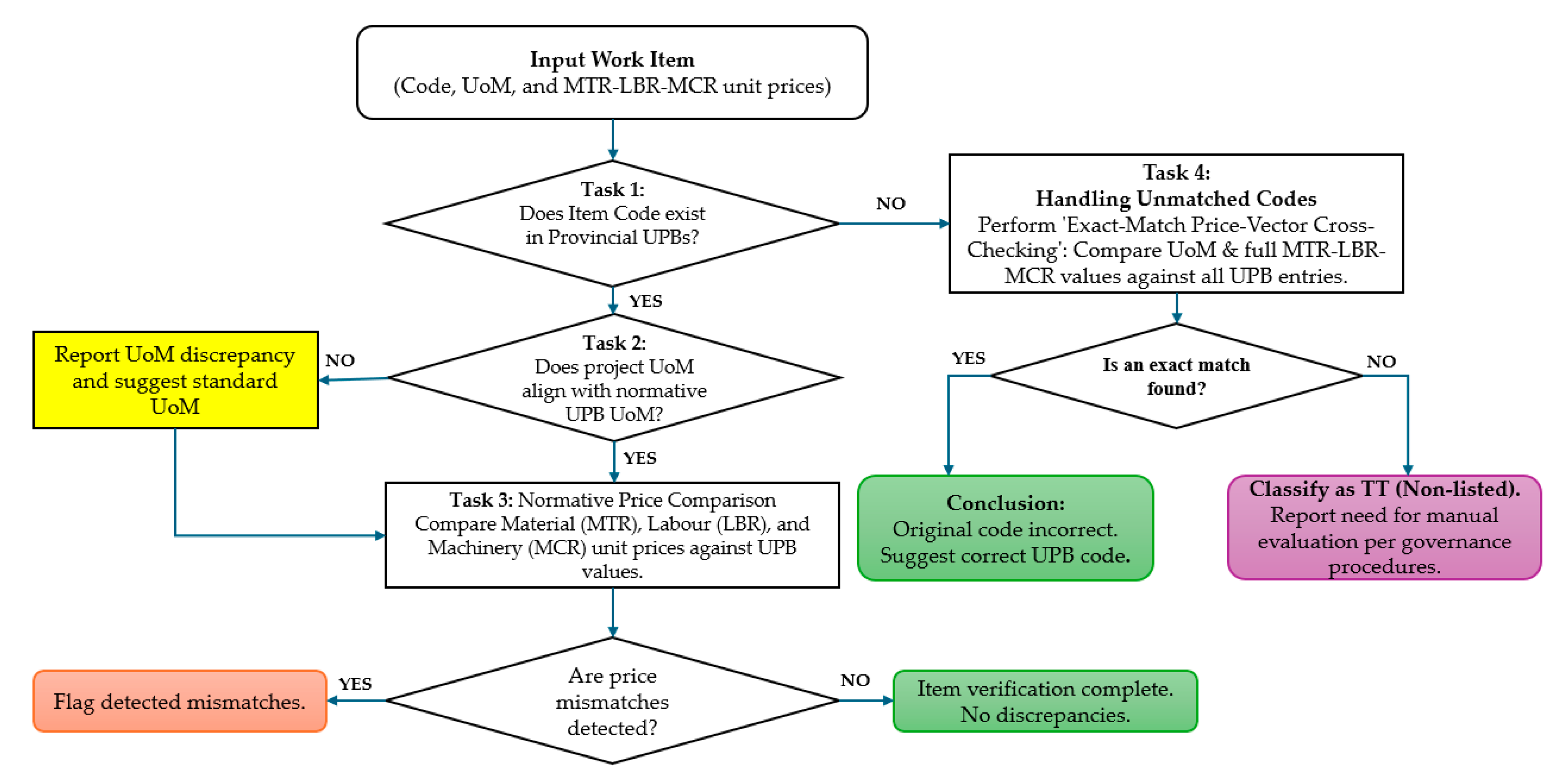

Apparently, in the context of construction estimate verification, the validation of work item codes and the parameters derived from UPBs based on these codes - including work descriptions, UoM, and unit prices - constitutes a critical task. Beyond the standard items explicitly listed in the UPBs, the analysis of codes exhibiting characteristics similar to non-standard items (referred to as "TT" items) proves valuable, as it facilitates the extraction of cost data that serves as a reference benchmark for verifiers. The workflow associated with verifying work item codes within construction estimates essentially encompasses the following components:

(1) Code verification: Confirming whether the work-item code exists in the provincial UPB.

(2) UoM verification: Ensuring that the project-applied UoM aligns with the normative UoM of the corresponding UPB item.

(3) Normative price comparison: Checking whether the material, labour, and machinery unit-price components match the official normative values for the verified code.

(4) Handling of unmatched codes: When a code cannot be found in the UPBs, the assistant must determine whether the item corresponds to an existing normative item that has been mis-typed or incorrectly coded. This requires cross-checking the estimate’s UoM and full price-vector (MTR - LBR - MCR) against the entire UPB to identify any exact matches.

If an exact match is found, the system classifies the item as a typographical or mis-assigned code and suggests the correct code to replace the erroneous one.

If no exact match exists, the item is classified as TT. TT items are routed to the TT verification pathway, where compliance depends on human evaluation of supporting price quotations (which the system reports but does not validate).

As noted in prior studies, the fragmented, spreadsheet-driven nature of construction documentation contributes to inconsistencies and error propagation (Nguyen, Dang et al. 2021; Vu, Pham et al. 2020; Niknam 2015).

Given that the entire verification logic pivots on the accuracy of these item codes, the fragmented nature of spreadsheet data presents unique obstacles, leading to specific operational difficulties that will be analyzed in the subsequent section on code-centred verification.

2.3. Key Challenges in Code-Centred Verification

International literature highlights several challenges inherent in construction cost checking, including semantic ambiguity, manual data handling, and the complexity of aligning project-specific descriptions with standardized cost norms [

6,

7,

14,

15]. In Vietnam, these issues are magnified due to the structure of UPBs and the heavy use of Excel-based workflows. The following challenges are particularly consequential:

- Mis-typed or mis-entered codes: These represent the most frequent and disruptive errors. Even minor deviations - extra spaces, missing digits, outdated codes, or carry-over errors from old spreadsheets - prevent linkage with normative datasets. Given that a single mis-typed code invalidates UoM and price checking, this issue accounts for a large proportion of verification inconsistencies [

14,

16].

- Partial modifications to price components: Designers may update material, labour, or machinery prices to reflect new assumptions but forget to update the work-item code. Since each normative item has a characteristic price structure, such partial edits often produce mismatches undetectable by rule-based software tools.

- Semantic ambiguity in descriptions: Project-specific descriptions often diverge from the standardized nomenclature used in UPBs. This creates semantic drift that forces evaluators to rely on experience rather than deterministic matching, especially when codes are missing or inconsistent [

17,

18].

- Limitations of existing software tools: Popular Vietnamese estimating tools (e.g., G8, GXD, F1, ETA etc.) primarily perform formula checking or code existence lookup [

19,

20,

21]. They do not recover intended codes, interpret price-structure anomalies, or identify nearest matches - leaving evaluators to diagnose errors manually.

- Time pressure and workload: Verification is often conducted under compressed timelines linked to appraisal cycles or procurement deadlines, increasing the likelihood of oversight [

22,

23].

These challenges highlight a gap for intelligent tools capable not only of deterministic rule-checking but also supporting diagnostic reasoning when inconsistencies arise.

2.4. Why Determining the Intended Code Matters

The correctness of the work-item code is foundational to the entire verification process because it determines the normative UoM and MTR - LBR - MCR price components. Errors at this stage invalidate subsequent checks. Four error categories commonly encountered include:

(1) typographical deviations;

(2) outdated or incorrect codes carried over from previous designs;

(3) partial edits to unit-price components without updating the code; and

(4) intentional code manipulation for strategic reasons.

A key practical observation is that designers rarely modify all three price components simultaneously. Instead, adjustments are typically made to one or two components, meaning the underlying price vector retains a characteristic profile tied to the intended normative item. This makes the MTR - LBR - MCR structure a valuable diagnostic signal for code recovery - often more reliable than semantic similarity when descriptions are ambiguous or incomplete.

This insight aligns with recent research on numerical feature - based retrieval and vector similarity in construction information extraction [

14,

15,

24]. However, in the context of formal verification, such numerical profiles can only be operationalised through strict deterministic comparison rather than approximate or similarity-based inference. Accordingly, automated recovery of intended codes must rely on exact equality between the project item’s UoM and full MTR - LBR - MCR price vector and those of normative UPB entries. When this full vector matches a normative item perfectly, the discrepancy can be attributed to a mis-typed or mis-assigned code; when no such match exists, the item must be treated as non-listed (TT) and handled through the appropriate procedural pathway.

Thus, while the underlying price vector may retain a distinctive numerical signature, the system developed in this study employs only exact-match comparison to maintain auditability and avoid unsupported inference. Deterministic equality—not similarity—is the sole basis for automated intended-code recovery.

Given the variability of project conditions, evolving construction methods, and non-standard spreadsheet practices, deterministic rule-based tools remain essential for the foundational stages of verification. Exact-match diagnostics complement these rules by enabling transparent, reproducible identification of typographical or mis-assigned codes without introducing probabilistic behaviour or semantic interpretation.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Cost Verification and Norm Alignment: The Central Role of Code Correctness

Cost verification functions as a critical quality-assurance process in construction projects, especially in public-sector environments where transparency and accountability are required [

25]. Prior research consistently shows that verification workflows are highly vulnerable to inaccuracies arising from human interpretation and fragmented documentation [

26]. A recurring issue concerns misclassification, in which project-specific descriptions fail to align with standardized cost norms [

14], , leading to inconsistent item mapping and distorted budgeting [

15].

However, as demonstrated in

Section 2, the most consequential verification failures in Vietnam arise not from semantic discrepancies but from incorrect work-item codes - particularly mis-typed, mis-entered, or outdated ones. Because the code determines the normative UoM and MTR - LBR - MCR structure, even minor deviations invalidate large portions of the estimate. Such errors - though common in practice - have received limited attention in prior verification research.

A second recurring issue relates to partial edits of unit-price components without updating the code, resulting in price profiles that no longer correspond to the normative item. While existing studies recognize that inconsistent unit prices undermine estimate reliability [

6,

27], they seldom examine the behavioural pattern behind these inconsistencies: practitioners often modify only one or two components, leaving the residual price profile largely intact.

This insight is critical for intended-code recovery. The MTR - LBR - MCR price vector often retains a distinctive “signature” of the intended normative item, even when the code or description is incorrect. Existing digital approaches - including BIM-based rule checking, ontology-driven classification, and automated quantity take-off [

28,

29,

30] - do not address this numerical mechanism. Likewise, existing Vietnamese estimation software focuses primarily on deterministic checks and lacks diagnostic inference capabilities [

19,

20,

21].

These studies indicate a need for methods that can detect code inconsistencies and determine whether a project item exactly corresponds to a normative entry based on strict numerical equality rather than similarity-based inference, forming the conceptual motivation for this research.

3.2. Digital and AI Approaches for Code Matching and Numerical Similarity

Recent digital construction research demonstrates strong progress in NLP, machine learning, and structured data extraction for classification, compliance checking, and information retrieval [

18,

31]. These methods effectively process unstructured documents but do not address the structured numerical reasoning central to cost verification.

Research on similarity-based retrieval provides a complementary direction. Embedding methods, clustering, and vector similarity have been used to compare construction attributes or identify related tasks [

14,

15]. When adapted to cost verification workflows, these approaches enable comparison of unit-price vectors - material, labour, and machinery - to identify the most similar normative items. This direction is especially relevant in Vietnam because, as shown in

Section 2, practitioners frequently adjust only one or two price components, producing a partially intact price signature that can be leveraged for inferential matching.

Machine-learning studies also highlight the potential of structured numerical features for matching construction tasks [

24,

32]. Although these studies do not explicitly target unit-price matching, they demonstrate the feasibility of vector-based retrieval methods in construction informatics. However, in the context of regulated cost verification, such numerical similarity cannot be used for automated decision-making; instead, any computational method must rely on strict deterministic comparison rather than approximate or nearest-neighbour matching.

Recent advances in transformer-based LLMs extend this potential by enabling multi-step reasoning and integration of external datasets [

33,

34]. Nevertheless, deterministic verification workflows—such as those required for code checking under Vietnamese norms—prohibit probabilistic inference or similarity-based suggestions. As such, LLMs can only support tasks when their behaviour is constrained to rule execution and exact numerical comparison rather than semantic or similarity-driven interpretation.

While existing literature confirms the feasibility of vector comparison, our system implements these ideas strictly through exact-match numerical equality. This approach ensures auditability by eliminating reliance on similarity-based inference.

Despite these developments, no existing research integrates LLM-driven reasoning with numerical similarity for cost-code verification. Current systems remain focused on textual interpretation or deterministic rule-checking, leaving a clear gap in workflows involving mis-typed codes, partially edited price components, or TT items.

The framework proposed in this study directly addresses this gap by combining LLM-based procedural orchestration with Python-executed deterministic unit-price vector equality checks, supporting code verification and intended-code recovery without approximate reasoning.

3.3. Large Language Models and Their Potential for Structured Verification Tasks

Advances in AI have transformed how construction information is interpreted and used to support engineering decision-making. Reviews show increasing adoption of machine learning, deep learning, and Natural Language Processing (NLP) across construction management tasks [

33], with text mining frequently applied to extract structured information from heterogeneous documents [

34].

Earlier reviews, including Wang, et al. [

18], highlight that construction documents typically contain mixed-format and inconsistently structured information, creating opportunities for NLP to automate repetitive interpretation tasks. However, existing NLP and text-mining applications mainly target unstructured textual data - drawings, specifications, daily reports, and regulatory documents - and do not address the structured numerical reasoning required in cost verification.

Large Language Models extend the capabilities of NLP by enabling multi-step reasoning, rule interpretation, and procedural task execution. Unlike traditional NLP pipelines, which extract or classify information through predefined features, LLMs can combine instructions, external references, and structured datasets within a single reasoning process. This allows LLMs to perform tasks such as:

checking whether entries align with external rules or normative datasets;

identifying inconsistencies in tabular values;

verifying multi-component numerical structures; and

generating transparent explanations that reflect human-like verification logic.

LLMs are therefore well-suited for verification tasks requiring contextual reasoning, step-by-step checking, and dataset interpretation.

However, it is important to note that existing LLM applications in AECO have focused primarily on document understanding, knowledge extraction, and high-level reasoning. No current studies apply LLMs to structured numerical comparisons, such as checking cost codes, verifying unit-of-measurement validity, or evaluating the consistency of unit-price components (materials, labour, machinery). Similarly, existing AI research does not explore the potential of LLMs to support intended-code recovery - a task requiring both detection of mis-entered data and inference of the most plausible normative item based on numerical similarity.

In compliance-critical workflows such as cost verification, however, these higher-level reasoning capabilities cannot be used for automated decision-making unless they are tightly constrained. LLMs must be restricted to deterministic rule execution, with all numerical comparisons performed through exact, Python-executed equality checks rather than probabilistic or similarity-based reasoning.

This gap positions LLMs as a novel enabler for structured verification workflows. By integrating procedural rules with reference datasets and numerical checking methods, LLMs can assist verifiers in diagnosing errors, validating price consistency, and retrieving the nearest normative items when mismatches occur. In the system developed in this study, such assistance is limited to orchestrating the verification sequence, while all computations that determine verification outcomes are grounded in deterministic Python logic to ensure full auditability and eliminate unsupported inference. This conceptual foundation motivates the design of the GPT-based assistant developed in this study and informs the Action Research methodology described in

Section 4.

3.4. Research Gap

Despite significant advances in AI for construction engineering and management, several critical gaps remain. Existing digital methods focus primarily on text-based interpretation, offering limited support for the numerical reasoning required in cost verification [

18,

34]. Prior research does not examine the detection of mis-typed or mis-assigned codes, even though these constitute one of the most frequent and consequential errors in practice.

Similarly, no AI studies leverage unit-price-vector similarity to infer intended codes or benchmark TT items - despite strong practical relevance, as practitioners typically modify only part of a price structure. However, in compliance-critical settings, such vector-based analysis must be operationalised through strict deterministic equality rather than similarity-based inference. Finally, LLMs have not been applied to structured verification tasks requiring deterministic reasoning, dataset grounding, and transparent justification.

This study addresses these gaps by developing a GPT-based verification assistant capable of deterministic code checking, UoM and unit-price validation, intended-code recovery, and TT benchmarking, operationalized through an Action Research methodology aligned with Vietnam’s regulatory environment.

4. Methodology: Action Research Design

4.1. Rationale for Choosing Action Research

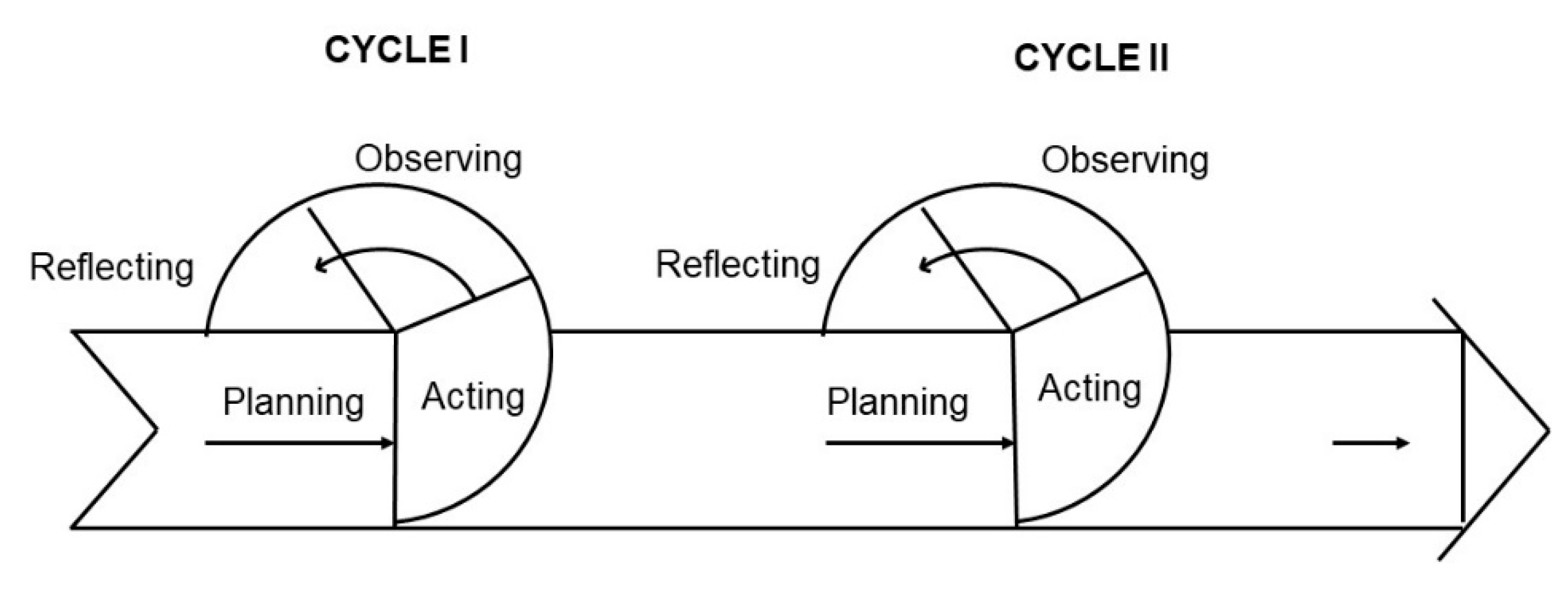

Action Research is a cyclical and collaborative methodology involving planning, acting, observing, and reflecting (

Figure 2), through which researchers and practitioners iteratively refine processes and systems [

35]. Some authors [

36,

37] extend this cycle by introducing diagnosing as an initial step aimed at identifying or defining the problem. AR is ideal for socio-technical contexts requiring domain expertise, evolving rules, and iterative calibration. Because AR prioritizes continuous learning and real-world experimentation, it provides a robust methodological foundation for developing a GPT-based assistant that must be incrementally aligned with professional verification practices.

(adopted and adapted from [

35,

38]

In construction cost verification, project conditions, spreadsheet structures, normative datasets, and practitioner interpretations vary widely across contexts. These factors make it unrealistic to design a fully deterministic AI system from the outset. Instead, the verification logic, prompt structures, and grounding mechanisms must be progressively refined based on inconsistencies observed in real projects and feedback from evaluators. AR supports this evolution by enabling systematic adjustments after each development cycle, ensuring that the assistant remains practical, auditable, and aligned with regulatory workflows.

Accordingly, this study adopts the AR framework to structure the development of the verification assistant. Each cycle contributes to identifying system limitations, refining reasoning patterns, and enhancing dataset-grounded behaviour. The resulting framework adapts to practitioner insights, mirroring the actual logic of cost checking.

Importantly, in this study such refinements occur through adjustments to deterministic rule specifications, system prompts, and Python-based procedures rather than through any form of model learning or probabilistic adaptation.

4.2. Planning Phase

The planning phase focused on translating established verification rules into a structured framework that could be operationalised within a GPT-based assistant. Because cost verification in Vietnam follows a strict rule sequence - beginning with code verification, followed by UoM checking, normative price comparison, and finally the treatment of unmatched codes (see

Section 2 and

Figure 3) - the first step involved formalising these rules as deterministic system instructions. These instructions define the boundaries within which the GPT must operate and articulate the conditions under which each verification step may proceed or terminate.

Within this phase, particular attention was given to the handling of unmatched codes. Since many inconsistencies in practice arise from mis-typed or mis-assigned codes, the assistant must determine whether a given item corresponds to an existing normative entry despite the absence of a matching code. This required specifying an exact-match protocol in which the project item’s UoM and its full MTR - LBR - MCR unit-price vector are compared deterministically against every item in the UPB. A perfect match is interpreted as evidence of a typographical or mis-assigned code, allowing the correct normative code to be reported. If no such match exists, the item is identified as TT and routed accordingly. Importantly, the assistant does not attempt to validate price quotations associated with TT items, reflecting the fact that quotation evaluation is a professional responsibility external to the automated workflow.

The design and planning phase served a dual purpose within the Action Research framework: it not only formalised the full sequence of verification rules but also established the foundational system architecture for the first development cycle, providing a structured basis for iterative refinement in subsequent cycles. Given the stringent auditability and numerical precision required for construction cost-code verification, the study evaluated three feasible GPT-based system architectures: (i) fine-tuned GPT models, (ii) Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), and (iii) GPT combined with the Code Interpreter (Python) and a structured unit-price “database.” The third approach was selected as the only viable option. Unlike semantic-search-driven RAG, which is susceptible to hallucinations and unsuitable for exact numerical comparisons, the Python-enabled architecture supports deterministic rule execution, strict equality matching, and reproducible logic—an essential requirement for cost-estimation verification.

Following the architectural decision, a customised GPT model—referred to as Cost Code Verifier—was constructed using ChatGPT Plus Model 5.1. The UPBs were uploaded into the model’s knowledge environment, forming the retrieval-ready dataset to be accessed through Python-based queries. The next step was to encode the entire verification workflow into a single, comprehensive system prompt so that the assistant would consistently behave as a deterministic rule-execution engine rather than as an open-ended generative model.

At a high level, the system prompt is organised into seven sections: file and data-model rules, header detection, line-item detection, the four-task verification workflow, final classification, reporting, and safety constraints. It specifies that (i) all files stored in the Knowledge environment are treated as UPBs and must be loaded into a unified master table; (ii) all user-uploaded files are treated as single-sheet estimates from which the assistant must detect the header row, identify valid line items, and extract the code, description, UoM, quantity (if available), and the three unit-price components (mtr_unit_price, lbr_unit_price, mcr_unit_price); and (iii) all extraction, normalisation, and numerical comparisons must be executed exclusively through Python, never through LLM “guessing” or internal numerical reasoning.

The prompt further encodes the four-task deterministic workflow: (1) code existence checking, (2) UoM verification, (3) component-wise comparison of the three price fields against UPB values, and (4) an exception flow for items whose codes do not exist in the UPB. For this exception flow, the prompt instructs the assistant to perform exact equality checks on the full UoM and MTR - LBR - MCR price vector against all UPB entries and to suggest a corrected code only when a perfect match is found; otherwise, the item must be classified as TT. Final outcomes are mapped into a finite set of statuses (e.g., exact_match, uom_mismatch, price_mismatch, code_not_found, code_corrected_by_diagnostic, out_of_library/tt, parsing_issue), and the reporting section requires line-by-line explanations detailing the rules applied and the evidence used.

Crucially, the system prompt establishes strict guardrails to prohibit non-auditable behaviours, including the generation of hypothetical codes, inference of normative values, or similarity-based matching. Through this structured design process, the logical model of the verification assistant was fully specified before implementation, ensuring that all subsequent Action Research cycles remained anchored in transparent, deterministic, and regulation-aligned decision rules, while the full technical specification of the prompt remains available for scrutiny in the supplementary material.

Subsequent execution revealed that Python cannot access UPB files stored in the Knowledge environment; this implementation constraint and the resulting workflow adjustments are discussed in Cycle 1 (

Section 4.3).

4.3. Acting Phase

During the acting phase, the planned verification framework was implemented into a functional GPT-based assistant and iteratively refined through cycles of prompt engineering, dataset integration, and behavioural calibration. The assistant was designed to parse heterogeneous spreadsheet structures by using pattern-guided extraction instructions that enable it to recognise work-item codes, UoMs, and MTR - LBR - MCR fields even when presented in varying layouts. These extraction mechanisms normalise dissimilar header formats and irregular cell structures, ensuring that verification proceeds from consistent and reliable inputs.

The deterministic rule sequence formalised in the planning phase was then embedded into the assistant’s operational workflow. Rather than relying on LLM-style procedural reasoning or interpretation, the assistant executes each verification step through Python-controlled logic, ensuring that all operations follow the deterministic sequence exactly as specified. The model executes the verification steps in strict order and is prevented from bypassing or reordering them. All numerical comparisons, rule evaluation, and exception handling are performed by Python, not by the LLM’s internal reasoning processes.

When encountering an unlisted code, the system activates the exact-match protocol, in which the extracted UoM and price vector are compared against all UPB entries. This comparison is carried out entirely through deterministic equality matching in Python, and only a complete match leads to the identification of the correct normative code; otherwise, the item is conservatively classified as TT. In addition, the assistant clearly distinguishes between verified items, UoM inconsistencies, normative price deviations, typographical errors, and TT outcomes, presenting each result in an auditable and practitioner-oriented format. Its role in this phase is limited to orchestrating the workflow and reporting outcomes, without performing any form of probabilistic inference or LLM-driven diagnostic reasoning.

These mechanisms ensured that the GPT's behaviour remained transparent and compliant with the deterministic logic required for public-sector cost verification.

During the first acting cycle, execution revealed a critical platform constraint: Python cannot access files stored in the GPT’s Knowledge environment. Since deterministic verification depends on Python loading and comparing UPB datasets, this limitation prevented the prototype from constructing the normative tables required for rule execution. Instead, the assistant returned runtime errors requesting manual UPB uploads. This observation required a redesign of the data-loading workflow, prompting Cycle 2 to remove dependence on Knowledge-stored UPBs and to incorporate explicit instructions for runtime dataset uploads.

4.4. Observing Phase

The observing phase assessed how the GPT-based assistant performed when executing verification tasks across both real project estimates and the controlled error-injection cases. Across all trials, the assistant consistently applied the deterministic rule sequence, reliably identifying valid codes, UoM mismatches, and deviations between project and normative MTR - LBR - MCR values. Because every decision was grounded in the UPB datasets and executed through Python-based equality checks, the assistant did not hallucinate codes, interpolate missing values, or introduce interpretive judgments beyond the prescribed workflow.

A critical component examined during this phase was the system’s behaviour when encountering invalid or non-existent codes. In these situations, the deterministic pathway triggered the exact-match diagnostic, in which the project item’s UoM and full price vector were compared—using strict Python equality—against every entry in the UPB. When an exact match existed, the assistant correctly identified the intended normative code, reproducing the manual recovery step typically carried out by human verifiers. When no match existed, the item was conclusively classified as TT, and no suggestion, ranking, or approximate resemblance was generated. This behaviour aligned directly with regulatory expectations prohibiting probabilistic or similarity-driven matching.

The observing phase also highlighted several categories of mismatches where exact-match diagnostics are intentionally not permitted, including wrong-but-valid codes and altered price components. When a code exists in the UPB but its MTR - LBR - MCR values differ from normative data, the assistant does not attempt any reverse recovery, because the presence of a valid code indicates that the discrepancy originates from edits to the price components rather than from a typographical error. Such items were therefore flagged deterministically as “normative price mismatches,” not routed to the exact-match layer, maintaining clear separation between the deterministic and diagnostic pathways.

The evaluation further revealed boundary cases arising from spreadsheet formatting inconsistencies, such as rounding differences or text-formatted numbers. In all such cases, the assistant correctly refrained from recovery: because numerical identity was not satisfied, no deterministic recovery could be triggered, and the system classified the item solely according to rule-based conditions—either as inconsistent (if the code was valid) or TT (if the code was invalid). This behaviour confirmed that the system applies no partial, approximate, or threshold-based logic.

Practitioner feedback reinforced these observations. Reviewers emphasised that the deterministic explanations reduced the effort required to identify typographical errors—the only class of errors eligible for exact-match recovery—while also preventing misclassification of items that merely resembled normative entries numerically. They also confirmed that no part of the assistant’s behaviour resembled inference, interpretation, or similarity reasoning; all outcomes stemmed exclusively from dataset-grounded deterministic execution.

Overall, the observing phase confirmed that the assistant’s behaviour strictly adhered to the decision tree encoded during system design. Exact-match recovery applied only to invalid codes. All other cases—including valid codes with altered prices, incorrect UoMs, or TT items—were handled exclusively by deterministic rules.

4.5. Reflecting Phase: Refining Verification Rules and Reasoning Patterns

Reflections across the development cycles informed refinements to both the assistant’s extraction mechanisms and the deterministic rule specifications governing its behaviour. Early cycles highlighted the need for more robust structural parsing, leading to improved handling of multi-row headers and non-standard layouts. Subsequent reflections focused on strengthening the enforcement of deterministic rules, including clearer sequencing constraints and tighter grounding instructions to prevent the model from attempting approximate matches. The exact-match procedure for detecting typographical errors was likewise refined to ensure consistency across datasets.

Through this reflective process, the GPT assistant increasingly mirrored the step-by-step logic used by human verifiers, producing outputs that were more interpretable, auditable, and compliant with regulatory expectations without relying on any form of LLM-style inference or internal reasoning. All refinements applied in this phase concerned adjustments to system prompts and Python-based rule execution rather than changes to the model’s reasoning processes.

4.6. Summary of Action Research Cycles

Across the three AR cycles, the system evolved from a rule specification to a fully implemented GPT-based verification assistant capable of executing deterministic checks and identifying typographical errors through exact-match price-vector comparison. The first cycle established a robust data-extraction layer and ensured that spreadsheet variability did not impede downstream reasoning. The second cycle refined the assistant’s internal logic, embedding deterministic sequencing and exact-match rules directly into its operational instructions. The third cycle focused on improving TT classification and consolidating conservative behaviours that prevent unsupported inference.

The integrated outcome of these cycles is a verification assistant whose operation is transparent, grounded in authoritative datasets, and aligned with the regulatory logic of Vietnam’s cost-verification practice. All improvements resulted from adjustments to system prompts, deterministic rule definitions, and Python-based procedures, rather than from any form of model learning or LLM-style inference.

By the end of the third cycle, all verification outcomes were produced solely through deterministic rule execution, ensuring full auditability and eliminating any reliance on internal LLM reasoning.

5. System Implementation

The system was implemented to operationalise the verification logic defined during the planning stage of the Action Research cycles. Whereas the planning phase established the rule structure and behavioural constraints of the assistant, the implementation phase focused on translating these design specifications into a functioning GPT-based verification tool. The resulting system integrates deterministic rule execution, exact-match diagnostics, and structured reporting, enabling the assistant to replicate the reasoning sequence used by professional verifiers while remaining fully grounded in the provincial UPBs.

The architecture comprises three coordinated components: a data extraction and normalisation layer, a deterministic verification engine, and an exact-match module for handling codes that do not exist in the UPB. These components are embedded within a controlled GPT configuration that restricts the model’s behaviour to auditable, rule-based operations. By combining GPT’s natural language capabilities with strict procedural constraints, the system delivers explainable verification outputs without relying on probabilistic inference, semantic approximation, or any attempt to “guess” intended codes when a valid UPB code is already present.

5.1. Data Extraction and Normalisation

Cost estimates from real projects often exhibit substantial structural variability, including displaced headers, merged cells, heterogeneous naming conventions, and intermittent non-data rows. Before verification can occur, the system must interpret these structures and extract relevant fields reliably. In this implementation, all extraction, parsing, and header-normalisation operations are executed through Python, ensuring deterministic and reproducible handling of input spreadsheets rather than relying on the LLM’s internal interpretation. This is achieved by guiding the GPT-based assistant through a series of pattern-oriented parsing instructions designed to identify the work-item code, description, unit of measurement, and the three unit-price components corresponding to material, labour, and machinery.

During extraction, the assistant converts the input into a standardised internal representation. Header inconsistencies are resolved through normalisation rules, and irrelevant or narrative rows are filtered out. Python-driven routines enforce strict column detection, datatype parsing, and canonicalization, ensuring that no inference or heuristic reasoning from the LLM influences the extracted values. This ensures that subsequent verification steps rely on standardised data, irrespective of the original spreadsheet layout. Where formatting is ambiguous, the system applies conservative Python-based extraction behaviour to preserve auditability and avoid any reliance on LLM-generated assumptions.

5.2. Deterministic Verification Operations

Once the input data have been normalised, the system executes the deterministic verification workflow defined in the planning phase. This workflow replicates established verification procedures used in Vietnam and reflects the regulatory logic underlying the UPB framework. All verification steps—including code lookup, UoM comparison, and evaluation of MTR - LBR - MCR price components—are executed exclusively through Python to ensure deterministic, reproducible outcomes consistent with the system architecture described in

Section 4.2.

The system first determines whether the work-item code exists in the UPB. If the code is valid, the assistant does not attempt any form of reverse lookup, intended-code recovery, or approximate matching. Instead, it retrieves the corresponding normative UoM and compares it with the project-applied UoM. Any discrepancy triggers an immediate classification of inconsistency. When both code and UoM are consistent, the system compares the project’s unit-price components with the normative values. Items exhibiting deviations are classified strictly as “normative price mismatches”; no diagnostic recovery is triggered when a valid UPB code is already present.

Throughout this process, the GPT assistant is constrained by system-level instructions that prohibit reordering steps, inferring missing information, or generating codes not present in the UPB. The assistant does not perform any numerical reasoning internally; all rule evaluations and numerical comparisons are computed by Python rather than by the LLM. All decisions must be traceable to regulatory data, and all reasoning must occur within the deterministic structure defined in the design phase.

5.3. Exact-Match Detection for Mis-Typed or Mis-Assigned Codes

A substantial proportion of verification inconsistencies in practice arise from typographical errors in work-item codes, rather than from semantic mis-assignment. To address these scenarios without resorting to probabilistic similarity methods, the system implements an exact-match module. This module is activated only when the project code does not exist in the UPB. In such cases, the module performs a deterministic equality comparison—implemented in Python—between the project item’s UoM and full price vector and all entries in the UPB.

A perfect match is treated as evidence that the estimator intended to reference the corresponding normative item but entered the code incorrectly. In these cases, the assistant reports the correct normative code and provides an explanation of the mismatch. No inference, no approximate matching, and no semantic interpretation are applied—only exact numerical identity qualifies for recovery.

If no exact match is found, the system concludes that the item is genuinely non-listed (TT) and routes it accordingly. The assistant does not assess or interpret price quotations associated with TT items, as quotation appraisal falls outside the scope of automated verification. This strict reliance on Python-based deterministic equality checks ensures that the module remains consistent with regulatory requirements and avoids any behaviour resembling LLM-driven interpretation or inference.

5.4. Non-Listed Items Classification and Structured Verification Output

Once an item is classified as TT, the assistant provides structured outputs explaining the basis for classification and the required procedural steps for compliance. These outputs specify whether TT status arises from the absence of a corresponding UPB code, the lack of an exact-match price vector, or both. As quotation appraisal falls outside the scope of automated verification, the assistant simply signals the need for supporting evidence rather than attempting to validate it.

Across all verification outcomes—compliant items, UoM mismatches, normative price deviations, typographical corrections, and TT items—the assistant provides line-by-line explanations of the rules applied and the evidence used. Because the system performs no semantic reasoning, no similarity assessment, and no inference beyond UPB data, all outputs remain auditable and fully aligned with regulatory expectations. This structured reporting format supports transparency, facilitates audit review, and allows the system to be incorporated directly into formal verification workflows for state-funded projects.

6. Results

6.1. Dataset and Test Setup

This subsection describes the dataset used to evaluate the GPT-based verification assistant, including the real cost estimates, the preprocessing procedures applied to standardize their heterogeneous structures, and the controlled error cases designed to test the full spectrum of verification logic.

A total of 20 construction cost estimates were collected from state-funded projects in Vietnam. These spreadsheets - prepared by project design consultants - exhibit substantial structural variation that directly affects automated code extraction, UoM verification, and construction of price vectors for deterministic comparison. Across the dataset, 16,100 work-item rows were analyzed, with individual estimates ranging from 27 to 4,677 rows, providing wide coverage across project types and levels of complexity.

Several characteristics of the real dataset were particularly relevant to code-focused verification. A total of 35 header configurations were identified, including multi-row headers, merged cells, displaced header rows, and heterogeneous labels for MTR - LBR - MCR fields. These structural variants influence the assistant’s ability to correctly identify the columns containing work-item codes, units of measurement, and price components. In addition, 39 subtotal or non-data rows were detected and removed to avoid false error detection. The dataset also included 222 TT items, which provided a useful basis for evaluating how the price-vector engine behaves under TT-type conditions. These characteristics are summarized in

Table 1, which outlines the structural and formatting patterns most relevant to automated code verification and deterministic comparison.

Further variability occurred in the representation of codes, UoMs, and price fields. Many codes appeared with extra spaces, hyphens, appended characters, or were embedded in merged cells. UoMs were expressed using multiple variants (e.g., “m2,” “M2,” “m²”), while price components often contained missing values, zeros, or inconsistent numeric formatting. These irregularities required robust preprocessing mechanisms—including canonicalization of codes, normalization of UoMs, deterministic numeric parsing, and consistent extraction of material - labour - machinery price fields—to ensure accurate rule-based verification and stable construction of price vectors for subsequent processing.

To ensure full coverage of verification scenarios that may appear infrequently in practice, an additional controlled set of 12 injected error cases was constructed. These represent six error types—mis-typed codes, valid codes with altered MTR - LBR - MCR values, incorrect UoMs, invalid codes with no exact match, TT-type synthetic items, and mixed-pattern deviations—each with two representative samples. The injected set was designed to test both the deterministic components of the verification workflow (code existence, UoM correctness, normative price matching) and the strict exact-match mechanism, which activates only when the code does not exist in the UPB.

Table 2 summarizes the structure and purpose of this error-injection dataset.

Each work item - both real and injected - was processed through the full verification pipeline:

(1) data ingestion and extraction of the code, UoM, and MTR - LBR - MCR values;

(2) deterministic checks for code existence, UoM alignment, and normative price consistency;

(3) conditional activation of exact-match diagnostics only when codes are invalid; and

(4) structured reporting with similarity-based benchmarking when applicable.

All similarity-based or approximate benchmarking processes present in earlier prototypes were fully removed to preserve deterministic, auditable behaviour.

6.2. Deterministic Verification Performance

The deterministic components of the verification workflow were evaluated across the full combined dataset, including the 20 real construction estimates and the controlled error cases described in

Section 6.1. These components operate strictly on rule-based logic—verifying whether (1) the work-item code exists in the applicable Unit Price Book, (2) the UoM aligns with the normative specification, and (3) the MTR - LBR - MCR price components match the official values. Together, these checks form the foundational requirements of code-focused verification and determine whether the exact-match module must be activated for invalid codes only.

To clarify how these deterministic checks translate into system outputs, the verification outcomes were grouped into five categories that capture the complete range of results produced by the rule-based pathway. The previous category describing “strong price-pattern deviation” was removed, as the system does not perform threshold-based or heuristic deviation analysis and cannot generate diagnostic signalling unless the code itself is invalid.

Table 3 summarises these five outcome categories, the conditions under which each category is triggered, and the corresponding system behaviour. These categories collectively define the decision boundaries for deterministic verification and determine whether corrective or exception handling pathways (e.g., exact-match recovery or TT classification) should be invoked.

The five deterministic verification outcome categories in

Table 3 include:

Valid Code - Full Normative Match,

Valid Code - UoM Mismatch,

Valid Code - Normative Price Mismatch, and

Invalid or Non-existent Code.

The system does not include any outcome category based on inferred or approximate assessments of price deviation; any deviation in price components under a valid code is treated solely as a deterministic mismatch rather than a trigger for diagnostic recovery. Diagnostic behaviour is activated only when the code is invalid.

These outcome categories form the complete range of deterministic behaviours that the system can exhibit during verification, ensuring that all items are classified solely according to rule-based checks and not through any form of approximate or nearest-match diagnostics.

6.3. Exact-Match Recovery Performance

The revised diagnostic mechanism relies exclusively on exact numerical matching between a project item’s unit-price structure and entries in the provincial UPBs. This mechanism reflects the deterministic procedure used by human verifiers when attempting to recover typographical errors in invalid codes, relying strictly on numerical identity rather than semantic resemblance. Unlike earlier conceptual formulations, the evaluation of this module was conducted solely on the twelve controlled error-injection cases rather than on the full set of twenty real estimates, ensuring that its performance was assessed under clearly defined and reproducible test conditions.

Across these twelve injected cases, the assistant encountered scenarios intentionally constructed to trigger exact-match behaviour, including mis-typed codes, invalid codes with no normative correspondence, TT-type items, and mixed-pattern deviations. Only when a code was not found in the UPB did the deterministic engine activate the exact-match comparison, in which the project item’s UoM and complete MTR - LBR - MCR price vector were evaluated for strict equality against all UPB entries. In cases where perfect equality was observed, the assistant recovered the correct normative code and reported the detected typographical error. All recovery outcomes resulted entirely from Python-executed equality checks, with no inferencing or approximate matching by the LLM.

The results demonstrated that exact-match recovery performs reliably for the narrow class of errors it is designed to address—namely, typographical deviations in codes whose price vector remains fully normative. All mis-typed code cases in the injected dataset were successfully recovered, and one mixed-pattern case also produced a valid recovery because its price vector remained intact despite the malformed code. For all other injected scenarios, exact-match recovery was correctly not invoked. Items with valid codes but altered prices, or valid codes with incorrect UoMs, were deterministically classified as inconsistent. Items containing invalid codes whose price vectors did not match any normative entry were routed to the TT pathway, distinct from TT-type synthetic items, which represent genuinely non-listed construction tasks rather than code-entry errors.

Boundary conditions also emerged in which rounding, formatting anomalies, or number-encoding differences produced marginal deviations in price vectors. In accordance with the system’s strict design principles, the assistant refrained from recovery in all such cases, as exact numerical identity is the sole permissible condition for code correction. This strict determinism is essential for auditability in state-funded verification workflows, where probabilistic, semantic, or similarity-based reasoning is not acceptable.

Practitioner feedback affirmed the interpretability of the exact-match module. Reviewers noted that deterministic explanations improved traceability and reduced the time required to identify typographical errors without encouraging overreach into semantic interpretation. The module therefore functions strictly as an exact-match detector rather than a reasoning engine, ensuring that all corrections arise from rule-based evaluation grounded entirely in normative data.

The performance of the exact-match recovery mechanism across the twelve injected cases is summarised in

Table 4, which reports the recovery outcomes and deterministic classifications for each error category.

6.4. Improvements Across Action Research Cycles

Improvements to the GPT-based verification assistant emerged progressively through the three Action Research cycles, each cycle revealing different classes of inconsistencies present in real estimates and prompting refinements to both extraction logic and deterministic rule execution. Across these cycles, the assistant evolved from a preliminary prototype with basic rule-following capabilities into a stable, auditable system aligned with the procedural expectations of Vietnamese cost verifiers. No inference-based or similarity-driven behaviour was retained; all refinements strengthened deterministic, data-grounded processing.

During the first cycle, substantial variation in spreadsheet structures - particularly displaced headers, merged cells, and non-standard column naming - made clear the need for more robust extraction patterns. The assistant's initial difficulties in identifying price fields under inconsistent labels prompted enhancements to header detection and normalisation rules, resulting in a more stable representation of MTR - LBR - MCR components across heterogeneous files. These changes strengthened deterministic parsing stability and ensured that later verification steps operated on fully normalised, unambiguous inputs.

The second cycle focused on the interaction between deterministic checks and the diagnostic layer. In early iterations, the system occasionally surfaced behaviour that resembled interpretive matching, especially when attempting to compare project items with normative data that were numerically similar but not identical. These behaviours were eliminated by reinforcing guardrails that require all diagnostic operations to rely exclusively on Python-based exact equality checks. As a result, exact-match recovery became strictly limited to invalid codes whose price vectors are identical to a normative entry, with no possibility of approximate or interpretive matching.

The third cycle emphasised the treatment of TT items and the clarity of classification boundaries. Earlier behaviour suggesting that the assistant might propose speculative alignments for non-matching items was removed entirely. TT classification was redefined to occur only when (1) the project code does not exist in the UPB and (2) no exact-match equality is found—ensuring clean separation between typographical error recovery and genuinely non-listed items. Additionally, refinements were made to the system’s structured reporting format, ensuring that all TT decisions reflect the deterministic decision tree and do not resemble any form of inference or recommendation.

Together, the improvements achieved across the Action Research cycles enhanced the system’s reliability, transparency, and alignment with real-world verification workflows. By the end of the third cycle, the assistant’s behaviour was fully deterministic at every stage—parsing, verification, diagnostic comparison, and classification—executed through Python-based equality checks and strict rule sequencing with no reliance on LLM reasoning, similarity-based inference, or speculative judgment.

6.5. Practitioner-Facing Insights from Real Estimates

Analysis of the twenty collected estimates also yielded several insights into the practical challenges that arise during verification and the implications these challenges hold for the deployment of the GPT-based assistant. A consistent observation concerned the extent of structural heterogeneity across spreadsheets. Header configurations varied widely not only in layout but also in terminology and ordering, and several files included non-standard header rows, repeated project metadata, or partially merged cells. These inconsistencies confirmed the need for a robust extraction and normalisation layer capable of interpreting variant structures while avoiding erroneous field mappings. The assistant’s ability to parse these heterogeneous formats deterministically—without relying on LLM inference—was essential for ensuring that downstream verification remained stable and auditable.

A second insight relates to the prevalence of malformed or non-standard codes, which appeared more frequently than initially anticipated. Many of these arose from simple copy - paste errors or ad hoc formatting adjustments, leading to missing digits, additional characters, or truncated prefixes. Because such errors often blend into the surrounding spreadsheet context, they can remain unnoticed during manual verification. The assistant’s exact-match recovery mechanism proved effective in resolving these situations only when the corresponding price vector matched a normative UPB entry exactly. Practitioners reported that this capability reduced the time spent tracing numerical inconsistencies and helped prevent false TT classification caused solely by typographical errors. Importantly, users recognised that these corrections resulted from deterministic equality checks executed in Python, not from any interpretive or inferential behaviour by the LLM.

At the same time, the evaluation highlighted several cases where discrepancies stemmed not from obvious data-entry errors but from partial or incremental edits to unit-price components. These included deliberate or inadvertent adjustments to only one or two elements of the MTR - LBR - MCR structure while leaving the remaining values untouched. In these scenarios, because the code was valid, the assistant did not invoke any recovery logic; instead, such items were deterministically classified as normative price mismatches. Practitioners noted that these cases often required closer human scrutiny, as the assistant—by design—applies no approximate matching, similarity reasoning, or semantic interpretation beyond strict rule checks.

Another recurring insight involved the handling of TT items, which occurred frequently across the dataset, particularly in estimates for specialised or project-specific works. Practitioners emphasised that the assistant’s conservative behaviour—classifying TT items only after confirming both the absence of the code in the UPB and the absence of any exact-match correspondence—was essential to maintaining methodological integrity. Reviewers also appreciated that the assistant did not attempt to evaluate the plausibility of supporting quotations or the appropriateness of TT pricing, reflecting the fact that quotation appraisal lies outside the permissible scope of deterministic automated verification. They further noted that the assistant clearly documented the reasoning path leading to a TT classification, thereby simplifying subsequent manual appraisal.

Finally, practitioners highlighted the value of the assistant’s structured reporting. The line-by-line explanations clarified how each decision was reached, which rule triggered the outcome, and whether the item was resolved through deterministic means or exact-match recovery. These outputs were seen as directly usable in verification records, supporting audit requirements and facilitating communication between verifiers, consultants, and project owners. The consistency and non-inferential nature of these explanations contributed to a strong sense of reliability and predictability, both of which were regarded as essential for broader adoption in professional workflows.

These insights demonstrate that the assistant performs verification tasks reliably while aligning with the documentation practices of cost evaluators. This alignment reinforces the practical feasibility of adopting deterministic GPT-based tools in state-funded verification contexts.

A detailed breakdown of structural variants observed across the twenty estimates - including sheet-level, header-level, and row-level patterns affecting code, UoM, and MTR - LBR - MCR extraction - is provided in

Table 5. These variants represent dataset features most relevant to deterministic verification performance, rather than any form of diagnostic or similarity-based reasoning.

7. Discussion

7.1. Theoretical and Technical Contributions

This study contributes to the emerging field of LLM-supported construction informatics by demonstrating that large language models can operate reliably as deterministic rule executors, rather than probabilistic or semantic reasoners. Unlike prior work that explored the generative or interpretive capacities of LLMs, the present research shows how domain rules, regulatory logic, and dataset-grounded behaviours can be encoded into a GPT-based system such that it reproduces professional verification workflows without performing any internal reasoning about codes or prices. In this configuration, the assistant functions as a constrained computational agent whose role is limited to orchestrating predefined verification steps rather than inferring or diagnosing verification outcomes.

A key technical contribution lies in the formalisation of a deterministic verification model for construction cost checking. The study operationalises the sequence of code validation, UoM verification, and normative price comparison in a manner that is both machine-executable and fully traceable. A major contribution is the introduction of an exact-match mechanism that operates exclusively when a work-item code is invalid. Rather than attempting similarity reasoning or assessing whether a code “resembles” a normative item, the system restricts diagnostic behaviour to strict equality checks across UoM and the three-component price vector. Only when perfect equality is observed does the system treat the case as a typographical error, ensuring that corrections arise solely from deterministic evidence. All computational steps—rule sequencing, UoM comparison, price-vector validation, and exact-match detection—are executed entirely through Python, eliminating hallucination risks and strengthening auditability.

The AR methodology further contributes to the theoretical framing by demonstrating how LLM-based tools can be incrementally aligned with practitioner expectations. Through iterative refinement across extraction logic, rule specification, and system guardrails, the study provides a methodological blueprint for embedding regulatory procedures within AI-assisted workflows. This research demonstrates that LLMs effectively support formal compliance tasks not by reasoning, but by invoking deterministic Python operations under strict controls.

7.2. Practical Implications for Cost Verification Practice

The results indicate strong potential for integrating deterministic LLM-based assistants into routine verification processes for state-funded construction projects. First, the assistant effectively mitigates one of the most common sources of inconsistency: invalid codes arising from typographical errors. By using exact-match recovery only when a code does not exist in the UPB, the system can identify the correct normative item whenever the price vector and UoM match perfectly. Practitioners reported that this capability substantially reduces the time required to trace typographical inconsistencies while avoiding incorrect TT classification. Importantly, users emphasised that recoveries arise solely from Python-based equality checks, not from any interpretive or approximate behaviour by the LLM.

Second, deterministic UoM and price verification offer improved consistency across evaluators. Human reviewers often differ in how they interpret formatting variations, missing fields, or blended rows. The assistant enforces a single verification pathway that eliminates discretionary interpretation and produces uniform outputs. Because the system does not judge the severity or meaning of numerical deviations, but only flags them as deterministic mismatches, professional evaluators retain full authority over contextual assessment. This alignment supports clearer audit trails and reduces ambiguity in verification outputs.

Third, the assistant’s conservative behaviour aligns with regulatory expectations. By avoiding approximate inference or code generation, the system respects professional boundaries. Its behaviour is strictly confined to rule-based detection. Reviewers who tested the system emphasised that its constrained behaviour made it easier to trust in compliance-critical settings compared with more open-ended AI tools.

Finally, the study highlights the feasibility of deploying LLM-based assistants even in environments characterised by high variability in spreadsheet formats and inconsistent field naming. The system’s stability stems not from the LLM’s interpretive capacity but from Python-driven extraction and normalisation routines, which ensure that verification proceeds consistently across formats. This demonstrates that LLMs can be integrated into digitalisation workflows even in industries where data structures lack uniformity, provided that model behaviour is strictly controlled and non-inferential.

7.3. Limitations

Certain limitations remain. First, the diagnostic capacity of the system is intentionally narrow: exact-match recovery succeeds only when the project item’s UoM and price vector correspond perfectly to a normative UPB entry. While this constraint is essential for auditability, it prevents the system from identifying cases where estimators apply normative items but introduce small edits—deliberately or inadvertently—to one or more price components. Such borderline deviations remain fully dependent on human interpretation.

Second, the assistant does not evaluate or cross-check price quotations for TT items. As quotation assessment requires market knowledge and contextual reasoning, it falls outside the scope of deterministic automation. The assistant can classify TT items accurately but cannot determine whether their associated pricing is appropriate or compliant, and the present study does not attempt to validate TT quotations against market benchmarks or multi-vendor comparisons.

Third, although the extraction logic proved robust, highly unconventional spreadsheet formats, embedded formulas, merged numerical fields, or corrupted cells may still affect input quality, as the system relies entirely on deterministic Python parsing. The assistant also cannot yet process multi-sheet estimates containing cross-sheet references or hierarchical cost structures, which are common in more complex consultancy submissions.

Fourth, although the current implementation supports verification across multiple provincial UPBs by allowing users to upload multiple datasets, the system does not yet automate province detection, dataset switching, or conflict resolution when codes overlap or when multiple normative regimes apply simultaneously. Multi-province or mixed-regime verification therefore requires explicit user management of the relevant UPB files, and automated rule adaptation across provinces remains an area for future development.

Finally, the study did not evaluate the system in live verification environments, where iterative revisions, document versioning, and multi-actor workflows may introduce additional operational challenges. Future research should examine how deterministic verification behaves under real-time document flows, collaborative checking environments, and integrated digital-approval platforms, where input volatility and procedural dependencies may be substantially higher than in controlled testing.

7.4. Implications for Scaling and Future Deployment

Scaling the GPT-based verification assistant beyond controlled settings introduces several considerations for technical deployment and organisational adoption. At the technical level, extending the system to handle real-world volume and diversity will require enhancements to support multi-sheet estimates, cross-referenced tables, and deterministic switching across multiple UPB datasets. Scaling will also require robust mechanisms for dataset management, including version control, tracking normative updates, and ensuring consistent mapping across provincial datasets. Because the assistant operates deterministically, maintaining identical Python-executed behaviour across environments and deployments will be critical for preventing drift or unintended interpretive variation.

From an operational perspective, integration into organisational workflows introduces challenges related to reproducibility, auditability, and alignment with existing approval processes. Verification agencies frequently revise and reissue estimates, sometimes under significant time pressure. To function effectively in such contexts, the assistant must produce stable outputs even as inputs evolve across project versions. The deterministic nature of the system is advantageous here, as it guarantees consistent results for identical inputs, facilitating document traceability and regulatory compliance.

Scaling also carries implications for workforce practices. Introducing a deterministic, rule-based assistant may reduce manual effort associated with routine checks while shifting human attention toward interpretation of TT items, borderline inconsistencies, and contextual judgement that automation cannot perform. Training programmes will therefore be required to ensure that evaluators understand the system’s capabilities and limitations and avoid overreliance on automated outputs. Future scaling efforts may also explore deterministic support modules for TT quotation assessment, provided such extensions maintain strict auditability.

Finally, large-scale deployment offers opportunities for broader system-level learning. With widespread adoption, aggregated usage patterns could reveal recurring sources of spreadsheet inconsistency or highlight areas where digitalisation (e.g., standardised templates or unified data schemas) would reduce verification effort. Although the assistant is intentionally conservative—eschewing semantic inference in favour of deterministic correctness—future extensions may explore optional, still-deterministic modules for enhanced reporting or data governance, provided they remain auditable and do not introduce inferential behaviour.

8. Conclusions

This study developed and evaluated a deterministic GPT-based assistant for construction cost code verification, addressing a persistent and labour-intensive challenge in Vietnam’s state-funded project workflows. By translating established verification procedures into a machine-executable framework, the research demonstrates that large language models can be configured not as probabilistic or interpretive systems but as strict rule executors whose behaviour is fully grounded in regulatory datasets and controlled through Python-governed operations. Through the Action Research methodology, iterative refinement across multiple development cycles enabled the system to evolve into a stable, auditable verification tool that aligns closely with professional practices.