Drug Discovery Is Costly

Drug discovery and development is costly, time-consuming, and subject to failure [

1]. While clinical phases are individually the most costly, the sequential nature of drug discovery and high cumulative failure rates mean that the majority of cost per approved drug—where total costs per approved drug now exceed

$1B [

2,

3]—is due to accumulated failures in the discovery phase and associated issues that likely could have been addressed earlier in discovery. The success of a drug discovery program hinges on multiparameter optimization: the empirical balancing of on-target potency, off-target specificity, and ADMET properties. This balancing act is where predictive models have the greatest potential to reduce costly cycles of design, synthesis, and testing.

Computer-Aided Drug Discovery (CADD) Holds Enormous Potential to Accelerate Progress

Computer-aided drug discovery (CADD) has long sought to guide molecular design decisions with predictive models, aiming to save time and reduce attrition [

4]. Even modest improvements in model accuracy can yield super-linear returns by reducing the number of compounds that need to be synthesized or advanced [

5,

6].

A surge of enthusiasm for new drug discovery methods driven by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has brought significant new talent, techniques, and energy to the field. This has increased expectations for major breakthroughs in performance, similar to what AlphaFold achieved with protein structure prediction (as well as the expansion into related areas, such as nucleic acid and small-molecule prediction, using software inspired by AlphaFold [

7].

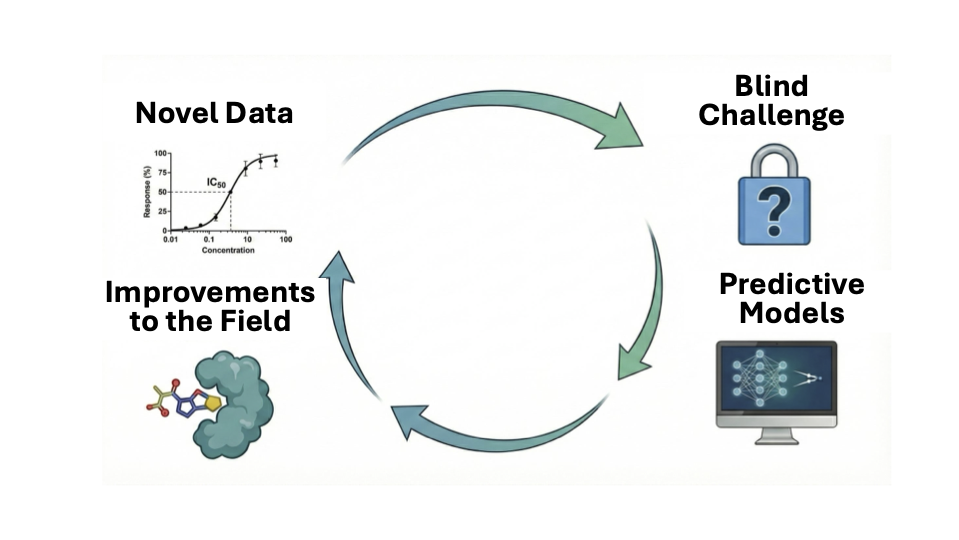

The history of blind challenges in related fields of structural biology and computational chemistry underscores their value. The CASP experiment in protein structure prediction—supported by decades of systematic data curation from the Protein Data Bank (PDB)—galvanized progress and culminated in AlphaFold’s breakthrough. Blind challenges drive method development by providing essential experimental feedback, sharing valuable benchmarks with the community, and maintaining focus on aspirational goals for models that deliver real utility.

As CADD looks for its “AlphaFold” moment, it remains difficult to evaluate how well these models actually perform in practice. Retrospective benchmarks are plagued by data leakage, inconsistent curation, and a lack of standardized datasets [

8,

9]. Moreover, practical AI/ML models often demand large, high-quality datasets that remain scarce in many critical domains of drug discovery. Blind challenges provide an essential solution. By assessing models prospectively on common, well-designed datasets unavailable during training, blind challenges create a level playing field, generate realistic estimates of predictive utility, focus the field on critical problems in need of solutions, and foster rapid community-wide iteration and learning to accelerate progress. Similarly, SAMPL [

10], D3R [

11]/CELPP [

12], and CACHE [

13] have advanced free energy calculations, docking, and hit identification, respectively. Without careful prospective assessment, it is easy to fool ourselves into overestimating practical performance—a risk Richard Feynman famously warned against (“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool. [

14]”). Currently, the CACHE initiative has begun to fill this gap for

on-target hit identification, providing a template for how prospective evaluation can sharpen models and align community efforts.

ADMET Properties and Anti-Target as a Focus for Blind Challenges

While on-target binding is often the first focus of predictive modeling, the ultimate fate of a drug candidate is usually determined by ADMET properties and interactions with anti-targets, proteins where drug binding alters toxicity and pharmacokinetics. Poor solubility, metabolic instability, transporter efflux, or unexpected channel binding (e.g., hERG [

15]) are among the leading causes of drug discovery failure. While factors such as poor solubility are primarily physicochemical, other critical bottlenecks, such as metabolic instability, transporter-mediated efflux, or unexpected ion channel binding, are often mediated by a relatively limited repertoire of proteins. While many of these liabilities are now screened for in the preclinical phase [

16], they remain primary drivers of attrition in the discovery pipeline. We dub this specific set of proteins 'anti-targets.' This set includes targets that mediate toxicity and metabolizing enzymes (such as CYPs [

17]). While interactions with the latter are sometimes optimized for specific profiles, they represent a finite landscape of interactions that, if better predicted, would benefit the entire field. The limited size of this set suggests that understanding these liabilities could be essential to improving success rates. Incorporating ADMET and anti-target data into predictive frameworks ensures that the next generation of AI/ML models does not simply identify binders but also identifies compounds with a realistic chance of becoming safe and effective medicines. Moreover, any gains made in the ability to predict compound interactions with these anti-target proteins are likely to benefit

all drug discovery efforts. In contrast, gains in the predictive ability against a specific target may not generalize.

Blind Challenges Require Evergreen Data Generation Efforts

For blind challenges to succeed in transforming the field, they require an evergreen source of new data. Retrospective repositories such as ChEMBL aggregate valuable information from the literature, but often resemble “dumpster diving” for data: large numbers of small heterogeneous assay datasets, inconsistent conditions, correlated or biased datasets generated for an orthogonal purpose, and mixed measurement types complicate the ability to both build accurate models and assess predictive utility with appropriate statistical power.

Centralized, large-scale initiatives can overcome these limitations by generating large, robust, high-quality, consistent datasets tailored to predictive modeling needs. Economies of scale, advanced technologies, and active learning can reduce costs, increase scale, and ensure the data generated is highly informative and fit-for-purpose for building and assessing predictive models.

In the near term, we anticipate that individual academic groups will continue to generate valuable public datasets on specific targets, providing a critical testing ground for new models. However, the most pressing ADMET datasets remain locked behind closed doors in industry, limiting broad community impact. Initiatives like OpenADMET (currently funded by ARPA-H Avoid-ome, the Gates Foundation, and the Astera Institute), in partnership with ASAP (the AI-driven Structure-enabled Antiviral Platform) and PolarisHub, aim to break this barrier by generating open datasets that capture both structural and functional information on key anti-targets. OpenADMET breaks down these barriers by leveraging high-throughput experimentation and structural biology to provide insights into how diverse small molecules bind to the 'Avoid-ome'. By pairing X-ray and cryoEM structures with comprehensive biochemical and cellular assay data generated under consistent conditions, the initiative provides the community with the 'ground truth' needed to move beyond reliance on heterogeneous literature databases. These collaborations create a continuous pipeline of high-throughput experimental data that can be used in future challenges and benchmarking efforts, ensuring that the challenges featured in this issue have a sustainable source of high-quality data. Sustained blind challenges on individual anti-target datasets will sharpen models for well-defined liabilities, while complementary ADMET challenges from individual target-based campaigns, such as the pan-coronavirus study highlighted here, will test whether models can handle the multiparameter trade-offs that ultimately determine success in drug development. Together, these dual-challenge formats will be essential to ensuring that predictive modeling keeps pace with the complex realities of drug discovery.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) under AVOID-OME: Structurally enabling the “avoid-ome” to accelerate drug discovery, and Award Number 1AY1AX000035-01.

References

- Scannell, J. W.; Blanckley, A.; Boldon, H.; Warrington, B. Diagnosing the Decline in Pharmaceutical R&D Efficiency. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11(3), 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringel, M. S.; Scannell, J. W.; Baedeker, M.; Schulze, U. Breaking Eroom’s Law. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19(12), 833–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erooms_law: Eroom’s Law; Github.

- Brown, F. K.; Sherer, E. C.; Johnson, S. A.; Holloway, M. K.; Sherborne, B. S. The Evolution of Drug Design at Merck Research Laboratories. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2017, 31(3), 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirts, M. R.; Mobley, D. L.; Brown, S. P. Free-Energy Calculations in Structure-Based Drug Design. Drug Design 2010, 1, 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Retchin, M.; Wang, Y.; Takaba, K.; Chodera, J. D. DrugGym: A Testbed for the Economics of Autonomous Drug Discovery. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.05.28.596296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahdritz, G.; Bouatta, N.; Floristean, C.; Kadyan, S.; Xia, Q.; Gerecke, W.; O’Donnell, T. J.; Berenberg, D.; Fisk, I.; Zanichelli, N.; Zhang, B.; Nowaczynski, A.; Wang, B.; Stepniewska-Dziubinska, M. M.; Zhang, S.; Ojewole, A.; Guney, M. E.; Biderman, S.; Watkins, A. M.; Ra, S.; Lorenzo, P. R.; Nivon, L.; Weitzner, B.; Ban, Y.-E. A.; Chen, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Song, S. L.; He, Y.; Sorger, P. K.; Mostaque, E.; Zhang, Z.; Bonneau, R.; AlQuraishi, M. OpenFold: Retraining AlphaFold2 Yields New Insights into Its Learning Mechanisms and Capacity for Generalization. Nat. Methods 2024, 21(8), 1514–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graber, D.; Stockinger, P.; Meyer, F.; Mishra, S.; Horn, C.; Buller, R. Resolving Data Bias Improves Generalization in Binding Affinity Prediction. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2025, 7(10), 1713–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernett, J.; Blumenthal, D. B.; Grimm, D. G.; Haselbeck, F.; Joeres, R.; Kalinina, O. V.; List, M. Guiding Questions to Avoid Data Leakage in Biological Machine Learning Applications. Nat. Methods 2024, 21(8), 1444–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Henriksen, N. M.; Slochower, D. R.; Shirts, M. R.; Chiu, M. W.; Mobley, D. L.; Gilson, M. K. Overview of the SAMPL5 Host-Guest Challenge: Are We Doing Better? J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2017, 31(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaieb, Z.; Liu, S.; Gathiaka, S.; Chiu, M.; Yang, H.; Shao, C.; Feher, V. A.; Walters, W. P.; Kuhn, B.; Rudolph, M. G.; Burley, S. K.; Gilson, M. K.; Amaro, R. E. D3R Grand Challenge 2: Blind Prediction of Protein-Ligand Poses, Affinity Rankings, and Relative Binding Free Energies. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2018, 32(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, J. R.; Churas, C. P.; Liu, S.; Swift, R. V.; Chiu, M.; Shao, C.; Feher, V. A.; Burley, S. K.; Gilson, M. K.; Amaro, R. E. Continuous Evaluation of Ligand Protein Predictions: A Weekly Community Challenge for Drug Docking. Structure 2019, 27(8), 1326–1335.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackloo, S.; Al-Awar, R.; Amaro, R. E.; Arrowsmith, C. H.; Azevedo, H.; Batey, R. A.; Bengio, Y.; Betz, U. A. K.; Bologa, C. G.; Chodera, J. D.; Cornell, W. D.; Dunham, I.; Ecker, G. F.; Edfeldt, K.; Edwards, A. M.; Gilson, M. K.; Gordijo, C. R.; Hessler, G.; Hillisch, A.; Hogner, A.; Irwin, J. J.; Jansen, J. M.; Kuhn, D.; Leach, A. R.; Lee, A. A.; Lessel, U.; Morgan, M. R.; Moult, J.; Muegge, I.; Oprea, T. I.; Perry, B. G.; Riley, P.; Rousseaux, S. A. L.; Saikatendu, K. S.; Santhakumar, V.; Schapira, M.; Scholten, C.; Todd, M. H.; Vedadi, M.; Volkamer, A.; Willson, T. M. CACHE (Critical Assessment of Computational Hit-Finding Experiments): A Public-Private Partnership Benchmarking Initiative to Enable the Development of Computational Methods for Hit-Finding. Nat Rev Chem 2022, 6(4), 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feynman, R. P. Cargo Cult Science. Engineering and Science 1974, 37(7), 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, A.; Lepailleur, A.; Mignani, S. M.; Dallemagne, P.; Rochais, C. HERG Toxicity Assessment: Useful Guidelines for Drug Design. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 195(112290), 112290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowes, J.; Brown, A. J.; Hamon, J.; Jarolimek, W.; Sridhar, A.; Waldron, G.; Whitebread, S. Reducing Safety-Related Drug Attrition: The Use of in Vitro Pharmacological Profiling. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11(12), 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denisov, I. G.; Makris, T. M.; Sligar, S. G.; Schlichting, I. Structure and Chemistry of Cytochrome P450. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105(6), 2253–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).