1. Introduction

Since the end of the Second World War, significant changes in immigration policies and global migration patterns have contributed to the transformation of major urban areas in the United States and Canada. In a manner of speaking, the world came to North American cities as the “internationalization” of immigration dramatically altered the socio-demographic profile of their populations and neighbourhoods (Allen & Turner, 1997; Murdie & Teixeira, 2011; Szkudlarek & Wu, 2018; Yasin & Hafeez, 2023). In this new “age of migration,” Los Angeles, New York, and Miami in the U.S., and Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal in Canada, have become major gateway cities— “cities of nations”—and the most multicultural spaces on the continent. A common characteristic of recent immigrants in both countries is that they prefer settling in major urban areas. The majority of immigrants living in Canada and in the U.S. are urban residents (Drolet & Teixeira, 2020; Kobayashi & Teixeira, 2012). While the majority of these newcomers have traditionally been working-class immigrants or refugees seeking better lives, these gateway cities have increasingly become magnets for highly educated and skilled migrants, some possessing substantial financial resources to invest in the North American economy (Banerjee et al., 2021; Ley, 2010; Li & Teixeira, 2007; Sweet & Harper-Anderson, 2023). This recent “diversity explosion” has profoundly enriched both countries, which have long relied on immigration to meet labour market demands, sustain population growth, and stimulate economic development. Both nations have also admitted refugees for humanitarian and/or political reasons. In the latter case, although skilled individuals are also found among refugee populations, their resettlement is often accompanied by distinct challenges associated with forced displacement and trauma (Figueiredo et al., 2023). Parents and their children are impacted by potential trauma and polyvictimization occurring during post-migration settlement (Brooks et al., 2024; Figueiredo et al., 2023; Figueiredo & Petravičiūtė, 2025; Tardif-Grenier et al., 2023).

This trauma encompasses not only the psychological impact of forced displacement but also the loss of familiar neighbourhoods, local social networks, and cultural institutions that once anchored daily life; it includes the erosion of communal identity and intergenerational continuity. Such disruptions can leave individuals and families feeling alienated, disoriented, or culturally unmoored, and are typically mitigated through the maintenance of ethnic community organizations, language retention programs, and culturally sensitive settlement services that provide both social support and a sense of belonging.

Coming from an array of cultures and social backgrounds, these immigrants represent a remarkable supply of human capital, their diverse skill sets contributing to the North American economy through paid work and self-employment (Banerjee et al., 2021). Like many Western countries, the U.S. and Canada are entering a “post-industrial age” in which a highly skilled, multicultural workforce is essential. As global markets expand for North American products and services, Canada’s and the United States’ diverse ethnic communities have helped businesses find new international partners (Li & Kaplan, 2006; Sithas & Surangi, 2021; Yasin & Hafeez, 2023). The rich ethnic diversity created by this new wave of immigration is an undeniable economic benefit for North America in the new global marketplace. (Ley, 2010; Li & Kaplan, 2006); Sithas & Surangi, 2021). However, while immigration continues to be an engine of the North American economy, the number of immigrants that the U.S. and Canada should accept, the balance between immigration categories, and the regional distribution of immigrants across both countries continue to be subjects for debate in public and political discourse (Banyard et al., 2025; Sweet & Harper-Anderson, 2023). In this discourse we find other issues: educational strategies to enable inclusion for young immigrants, especially in schools of Canada (Este & Ngo, 2011; Schleifer & Ngo, 2005; Tardif-Grenier et al., 2023; Weisleder et al., 2024).

Given aging populations, immigration’s demographic importance to the U.S. and Canada is clear

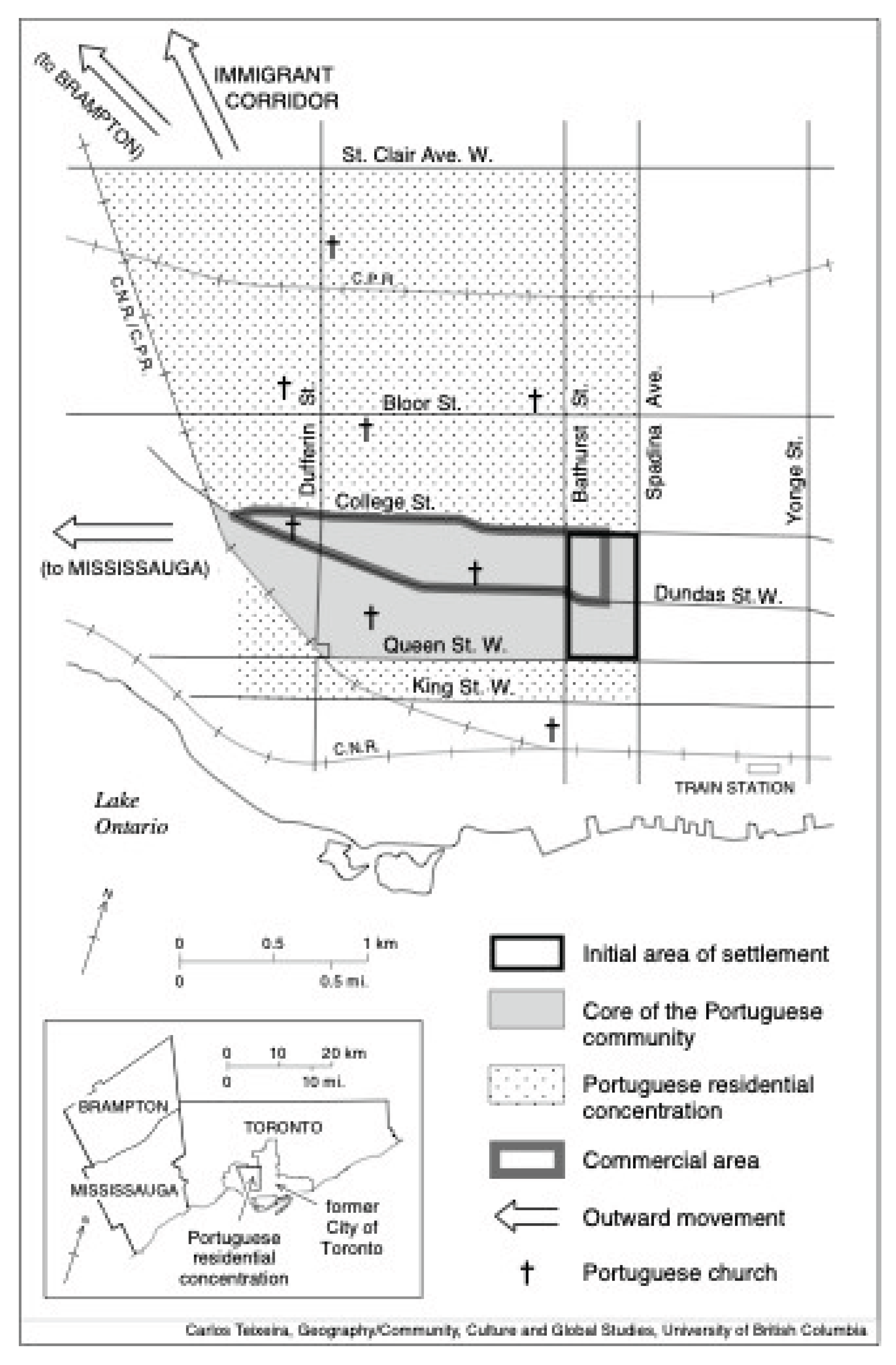

. Today’s North American cities are characterized by a mix of cultural and immigrant groups settled in a diverse array of ethnic neighborhoods and diasporic communities (Banyard et al., 2025). Children migrating both from less developed countries and from Western nations, such as those mentioned above, contribute to reshaping Canadian society, particularly through the introduction of new skills and professions once their education is completed (Banyard et al., 2025; Parameswara et al., 2024). Despite the numerous challenges they face, these immigrants are shaping the physical, social, and economic landscapes of major North American cities, states, and provinces in important ways (Sweet & Harper-Anderson, 2023). Scholars predict that neither the United States nor Canada will have a majority ethnic group by mid-century, raising questions about how ethnic identity shapes urban social geography (Dixon et al., 2022; Kobayashi & Teixeira, 2012; Preston et al., 2022; U.S. Census Bureau, 2024). Evolving immigrant settlement patterns are transforming the socio-economic and cultural fabric of cities and suburbs, raising critical questions about policy, identity, and belonging (Chen et al., 2023; Teixeira & Kobayashi, 2012; Sweet & Harper-Anderson, 2023). Toronto’s well-established Portuguese-Azorean immigrant enclave – “Little Portugal,” or the “Azorean Tenth Island” – offers a key social-cultural laboratory in which to study the role and impact of these immigrants on the urban and social/cultural, political and economic landscapes, and for the study of multiculturalism in one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the world (

Figure 1). Ethnic enclaves have become increasingly important elements of Toronto’s urban landscape. Over time, the Portuguese-Azorean community has incorporated ethnic businesses, social, cultural and religious institutions, gardens and shrines, architectural features, cultural symbols as well as other distinguishing physical-cultural characteristics. Studying ethnic enclaves can help us better understand how immigrant groups transform the built environment and integrate into the social-cultural and economic life of a new society. On the other hand, new developmental challenges and characteristics are being observed among immigrant children—phenomena that were not previously documented. Canada has long been regarded as a model for inclusive policies aimed at supporting traumatized children from immigrant backgrounds, particularly when socioeconomic conditions are taken into account (Walls, 2023). Children from the Azorean Islands, for instance, have often been associated with socioeconomic deprivation affecting their families as a whole. However, this population remains understudied in terms of its academic and socioemotional development within contemporary Canadian society and other societies with high density urban areas with immigration settled (Chen et al., 2023).

This theoretical study explores the emergence of “Little Portugal” within Toronto’s urban social mosaic, with a specific focus on the settlement and housing experiences, residential patterns and integration of Portuguese-Azoreans and their descendants born in Canada. It also explores issues related to gentrification as chronic urban trauma, with a particular focus on Portuguese seniors – the first-generation immigrant population who built the community – and Portuguese youth facing pressures of assimilation and displacement.

The Changing Geography of Ethnicity in North American Cities

Scholars have long modelled North American immigration in the 19th and early 20th centuries as a unidirectional process: migrants left their homelands to recreate familiar cultural settings that eased adjustment. Today’s immigrants—from Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America—are far more heterogeneous than earlier European arrivals, and their settlement patterns demand renewed attention. Especially considering young immigrants and their maladjustments to schools and to the new routines into the main community (Parameswaran et al., 2024; Zhuang & Lok, 2023). Earlier European immigrants typically settled in inner-city reception areas such as Toronto’s Ward or Montreal’s St. Louis neighbourhood, forming “institutionally complete” enclaves of businesses, churches, and social organizations that reproduced old-world traditions. Over time, many moved to the suburbs in pursuit of homeownership and upward mobility (Drolet & Teixeira, 2020; Chen et al., 2023; Murdie & Teixeira, 2006).

Since the 1970s, however, newer immigrants have often settled directly in suburban areas, bypassing the inner city. In places like Richmond, B.C., and Markham, Ontario, Chinese immigrants from Hong Kong exemplify the creation of “ethnoburbs” (Li, 1998; Preston et al., 2022). These complex patterns challenge traditional spatial assimilation models, suggesting that suburban immigrant settlement reflects a more varied set of economic and cultural choices (Hiebert, 2000; Zhuang & Lok, 2023). The diversity of experiences makes it difficult to identify universal factors behind ethnic and racial segregation (Darden & Fong, 2011; Preston et al., 2022; Zhuang & Lok, 2023). Some low-income immigrants remain concentrated in poor neighbourhoods, while more affluent groups have greater residential flexibility. Across the U.S. and Canada, diverse settlement forms including “ethnic enclaves,” “ethnoburbs,” “invisiburbs,” and “heterolocal communities” underscore the need for clearer frameworks explaining immigrant reception and integration (Skop & Li, 2003; Vine, 2024). Key questions remain about who assimilates whom, who defines the mainstream, and how power and identity are negotiated in multicultural societies. In the middle the traumatized children were forgotten considering the ethnoburbs and mainly the factor of displacement (McFarlan & Hinton, 2009; Pilipossian, 2023). The psychological stress response to these multicultural societies, during its construction, was neglected and converted in chronic urban trauma (Eissa & Zeira, 2024; Hall et al., 2023; Stamm & Stamm, 2013; Vine, 2024).

While many immigrants maintain transnational ties, their children often acculturate quickly through education and media, and intermarriage produces increasingly multiethnic populations. These shifts are redefining what it means to be “North American,” yet they are also creating new social and economic tensions that may reinforce class and ethnic divisions (Siemiatycki et al. 2003; Zhuang & Lok, 2023). Immigration continues to shape the social, cultural, and economic structures of North American cities, but comparative research between the U.S. and Canada remains limited. Both countries face similar challenges: discrimination, economic and housing barriers, and diverging policy responses. Understanding how ethnicity and race influence immigrant integration is therefore central to future studies. Ethnic geographers must examine how enclaves and urban ethnic landscapes evolve under these forces. The case of Portuguese-Azorean immigrants in Toronto’s “Little Portugal,” for example, offers a vivid setting for exploring multiculturalism in one of the world’s most diverse cities.

2. Portuguese-Azoreans in Multicultural Toronto: The Building and Maintenance of an Urban Ethnic Enclave. What the Future Holds…?

2.1. Trans-Atlantic Migration and Settlement Patterns

Although large-scale Portuguese and Azorean immigration to Canada officially began in 1953, maritime contact dates back to the 15th century, when Portuguese navigators fished off Newfoundland and later maintained ties through the “White Fleet” (Collins, 1992; Doel, 1992). Centuries of out-migration from Portugal and the Azores—driven by economic hardship—eventually directed many to Canada in search of work and family reunification (Pires et al. 2023). The first postwar wave of about 17,000 male labourers in the 1950s took up agricultural and railway jobs, followed by chain migration through the 1960s and 1970s. Most settled in Ontario, particularly Toronto, which remains the principal “port of entry.” Today, roughly 450,000 Canadians claim Portuguese origin—two-thirds Azorean—with concentrations in Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia (Statistics Canada 2022; 2024).

In the 1950s and 1960s, Portuguese and Azorean immigrants clustered in low-income downtown Toronto neighbourhoods such as Kensington Market, close to industrial work and transit (Teixeira, 1999; 2010; Taplin-Kaguru, 2021; Vaz, 2025). Chain migration and shared housing supported high rates of homeownership and strong community networks, making the group among Toronto’s most residentially concentrated (Teixeira & Murdie, 2009). By the mid-1960s, the community had transformed Kensington into a “Portuguese market,” with ethnic businesses, religious clubs, and homes adorned with azulejos and grapevines that recreated rural aesthetics (Teixeira 2009). Homeownership symbolized stability and mobility; many renovated aging houses with family labour and construction skills, often adding rental suites and cellars (Riviera, 2023; Taplin-Kaguru, 2021.

However, out-migration, limited new arrivals, gentrification, and rising housing costs have weakened Little Portugal’s institutional base and altered its demographic character as occurred already in other main destination of Portuguese as immigrants (Marques, 2019; Murdie & Teixeira, 2015). Although many Portuguese-Azoreans now live in the suburbs, the enclave endures symbolically as the “10th Azorean Island,” thus sustaining cultural identity amid ongoing urban transformation (Gendron, 2024; Meligrana & Skaburskis, 2005).

2.2. Portuguese and Azorean Seniors in Toronto’s Little Portugal: Resisting Gentrification and Displacement?

Gentrification has been defined as “the loss of affordable older inner-city housing through their renovation and upgrade by middle and upper-income households” (Meligrana & Skaburskis, 2005, p. 1571). Within this context, will gentrification mean the displacement of lower-income households, including the aging first-generation Portuguese-Azoreans, or are there viable strategies of resistance? Portuguese generally view Little Portugal as a neighbourhood in transition, with gentrification—rising housing prices and rents—affecting both Portuguese (especially seniors) and non-Portuguese residents. Research shows that there are three main groups leaving the area for reasons both voluntary and forced (Takahashi, 2023). The first are Portuguese and Azoreans in their 40s or 50s who are currently homeowners in the neighbourhood. This is a group with assets and financial stability that aspires to move to the suburbs to improve their housing conditions. The second group are well-off Portuguese and Azorean seniors who, with their mortgages paid, are moving to join children already established in the suburbs (Gendron, 2024; Takahashi, 2023). The third are Portuguese and Azorean seniors who are retired on fixed incomes. Within the first group, we mainly observe children of the second generation in Canada, who experience forms of displacement already encountered by their families, particularly their parents (Vieira & Teixeira, 2023). When reflecting on the Canadian landscape shaped by Portuguese and other immigrant communities, it becomes evident that children remain largely overlooked in scientific research, despite being immigrants who often struggle with social exclusion and learning difficulties. Though Portuguese and Azorean homeowners can profit from Toronto’s rising real estate market, it is clear that, even in the best-case scenario, many Portuguese and Azorean seniors and their children approach and share the prospect of moving with mixed feelings (Murdie & Teixeira, 2015; Takahashi, 2023; Teixeira, 2010).

Despite higher education, occupational skills, and incomes, most Canadian-born Portuguese cannot afford to buy homes in Little Portugal and instead seek affordable housing—either to rent or purchase—in the city’s outskirts and suburbs. To save money, younger generations sometimes rent from or live with their parents in intergenerational households, a practice that has grown since the early 2000s as Toronto’s housing market has become increasingly unaffordable. This daily habit of saving and living under financial constraint has become an internalized behavior and, for many immigrant children, a source of enduring psychological stress throughout their lives.

While the problem of an aging Portuguese and Azorean community, particularly its first-generation seniors, has to date received little attention from Canadian scholars and policymakers, it is clear that this group’s cultural needs and preferences with regard to issues of healthcare and wellbeing, ethnically oriented social services (preferably in Portuguese), as well as affordable housing, including long-term care deserves more detailed attention in future (Gomes, 2023; Sampaio, 2022; Takahashi, 2023). On the other hand, the well-being of second-generation immigrant children has received relatively little attention in research to date, even in other contexts where Portuguese populations are significantly represented as immigrant communities (Albert, 2021; Botelho, 2021).

3. A Community on the Move: From Voluntary Segregation to Integration

Portuguese and Azorean immigrants have largely integrated into Canadian society, contributing socially, culturally, politically, and economically. First-generation manual labourers were known for their work ethic and thrift, often taking multiple jobs to achieve homeownership. Women balanced full-time work with homemaking, though newer generations are seeing shifts in gender roles.

With regard to cultural traditions, many Portuguese purchase homes as an investment strategy, and their homeownership levels are higher than the Toronto average (Murdie and Teixeira 2006). It was common for several members of one family to hold more than one job in order to save money to attain the “dream” of owning a home on Canadian soil. Within this context, socio-economic pressures, such the desire to own a house, forced Portuguese and Azorean women to enter the paid workforce, effectively leaving these women with two jobs: full-time worker and traditional homemaker. This excessive burden has frequently affected women’s health. First-generation women’s emancipation has been gradual, but changes in sex roles may reconfigure the Portuguese and Azorean family (Giles 2002), and important gains have been made with this regard among the second- and third-generation Portuguese-Azorean women in Canada. Also, for economic reasons, such as buying a house or paying debts in Portugal, many parents forced their children to leave school as soon as possible to supplement the family income. This chronic urban trauma affects the family as a group. We cannot address here the traditional norm of trauma for one individual, but for the group composed by the family and generations of immigrants. Today, 68.4% of Portuguese in Toronto are homeowners, and first-generation residents make up 52.8%. With declining immigration from Portugal, the population is aging.

Family remains a key cultural value among Portuguese-Azorean immigrants, although generational changes are reshaping traditional structures. First-generation families have tended to emphasize large households, extended family ties, and religious values, while younger generations tend to forming smaller households and having fewer children. Over time, financial constraints and cultural assimilation may reduce the ability of younger generations to care for aging family members, leading to increased reliance on social services and government support. In 2021, 56% of Portuguese in the city of Toronto were married or living common-law, with very few being divorced (4%) or separated (1.5%) (Statistics Canada 2024).

Gentrification is transforming Little Portugal, prompting families to move to suburbs such as Mississauga and Brampton, seeking detached homes, green spaces, and family-friendly environments (Tardif-Grenier et al., 2023). Such pressures not only displace families geographically but also recalibrate how individuals perceive belonging, continuity, and the stability of their cultural reference points. Many Portuguese and Azoreans feel their culture is in transition. However, little is known about how the newer and young generations of Portuguese and Azoreans in Toronto relate to their parents' heritage. Do they see the Portuguese-Azorean community as a reference point? How significant are its cultural and social institutions to them? Will they integrate into Canadian society, losing ties to their ancestral homeland, or remain caught between cultures?

Language retention is key to maintaining ethnocultural identity, yet Portuguese language use is steadily declining, especially in smaller communities. Language is also highly correlated to ethnic identity and may affect communication within multi-generational households (Oliveira & Teixeira, 2004; Scetti, 2023; Vieira & Teixeira, 2022). This linguistic erosion is not merely a collective phenomenon; it also reshapes individual experience, as many younger Portuguese-Azoreans report a diminished sense of familial connection and cultural continuity when they no longer command their parents’ heritage language. Of the 448,305 Portuguese of ethnic origin living in Canada, only 53.7% declared Portuguese as their mother tongue, while 46.3% of second- and third-generation Portuguese reported having no knowledge of it (Statistics Canada 2022; 2024).

In Canada, the Portuguese language is in a transitional phase, with new generations (second and third) using their parents’ mother tongue at home less frequently and preferring English when in public. The language usage is connected directly to affective patterns such as sense of belonging and motivation to engage with the main communities (Figueiredo et al., 2019; Figueiredo, 2008). Ontario has the largest population of Portuguese mother-tongue speakers (153,750 or 63.9%), most of them in Toronto, where 60,360 of 85,165 residents of Portuguese origin (60,360, or 70.9%) reported Portuguese as their first language (Statistics Canada 2022; 2024). In Toronto’s suburbs and in smaller communities within the Toronto Census Metropolitan Area (excluding the city itself), in contrast, only 43.8% of those of Portuguese ethnic origin reported Portuguese as their mother tongue (Statistics Canada, 2012). This suggests a more complete level of cultural assimilation among “new” generations (second and third). Within this group, the linguistic duality that frequently characterizes the generation gap in immigrant households – where the children speak one language and the parents another – is becoming increasingly prevalent (DeSouza et al., 2023; Oliveira, 2021; Oliveira & Teixeira, 2004). Many Portuguese and Azorean youth engage in “code switching” – where English and Portuguese are mixed within a single conversation (Figueiredo & Silva,2009; Figueiredo, 2019; 2023a; Scetti, 2021; Vieira, 2021),). Otherwise, the language is the main instrument to deal with psychological disturbances these immigrants experience, mainly adults (Figueiredo, 2023b; Gaspar da Silva, 2023). The gradual loss of their home language and culture has left some Portuguese and Azorean youth feeling isolated from their parents and alienated from the Portuguese-Azorean community as a whole. Younger generations are less likely to consume Portuguese media (TV, radio, and newspapers), and few participate in social and cultural events or give preference to Portuguese businesses and services (Figueiredo et al., 2016; Oliveira & Teixeira, 2004). Similar generational differences in language use have been reported by other immigrant groups and their descendants in North American cities and suburbs (Figueiredo & Henriques, 2024; Zhou & Bankston, 2020).

Toronto’s Portuguese-Azorean community nevertheless strives to maintain its language and culture as well as a strong cultural presence in “Little Portugal” and through numerous cultural, religious, and business institutions. In 2007, Ontario had 100 Portuguese-Azorean clubs, 40 language schools, 26 churches with Portuguese services, and around 4,200 businesses. A decade later, Vieira (2021) identified about 100 cultural and social organizations in the Greater Toronto Area, many of which played vital roles in immigrant settlement and integration between the 1950s and the 1970s. Some continue to help community members by helping them find housing and employment. For many community members, these institutions act as anchors of resilience, enabling individuals and groups to sustain a coherent sense of identity amid broader assimilative pressures. While multiculturalism policies have encouraged the preservation of Portuguese culture, the next generation appears less engaged with these community institutions (Figueiredo et al., 2016; Vieira, 2021; Vieira & Teixeira, 2023). Canada’s state-sponsored multiculturalism policy may have served to encourage Portuguese immigrants to create ethnic-oriented organizations and to preserve their culture (Bloemraad, 2006; Qadeer, 2016). The latter organizations not only preserve and promote Portuguese language and culture for younger generations, they promote friendship and solidarity through a range of social, cultural, and recreational activities and function as a bridge between Portuguese-Azorean and mainstream Canadian culture. While their role and effectiveness have been the subject of debate over the last three decades (Da Rosa & Teixeira, 2009; Vieira & Teixeira, 2023) ethno-cultural organizations and multiculturalism have played a positive role in fostering tolerance and mutual respect among immigrant communities and cultures, including the Portuguese-Azoreans. For many immigrant groups, including the Portuguese it is expected that appeal of ethnic organizations will diminish overtime, especially among the more educated immigrants or new generations born in the host country. Portuguese youth in Canada often identify as “tricultural,” balancing Portuguese, Azorean, and Canadian influences. A study of 354 youth in Toronto and Montreal found that navigating multiple identities can be challenging (Oliveira & Teixeira, 2004). The future of Portuguese-Azorean identity in Canada thus remains uncertain.

4. Conclusion and Future Avenues of Research

What does the Future Hold for Portuguese and Azoreans, including the new and young generations in Toronto? In the second half of the twentieth century, Toronto has been transformed by a number of societal forces: economic restructuring, an aging population, new approaches to family organization, and changes in immigration patterns. The Portuguese-Azorean community has demonstrated resilience and has adapted relatively well to its adoptive society. Portuguese-Azorean immigrants have adopted different settlement and residential patterns – from pockets of ethnic concentration marked by a rich and distinctive urban ethnic landscape and cultural identity (particularly among the first generation born outside Canada) to dispersion (mainly among second and third generations born in Canada) in the suburbs and “exurbs” of Toronto, including schooling in this ecological system.

Portuguese-Azoreans have only been in Canada for seven decades. With varying degrees of loyalty to their Portuguese and Azorean cultural heritage, the majority of this community’s members (first generation) came to stay. As the newer generations in Ontario attain maturity, levels of education are rising, and assimilation is expected to increase. While ethnic identity is a source of enrichment for some Portuguese-Azoreans, for younger immigrants it can result in conflict, and the rejection of their cultural heritage. It remains uncertain whether second- and third-generation Portuguese-Azoreans will preserve their parents’ traditions. Current evidence points to “cultural duality” and “cultural conflict” among youth, and whether this tension can be reconciled in the future is unclear. The role of Portuguese and Azorean immigrants and their descendants as agents of change in the social, cultural, political, and economic life of Canada and the city of Toronto, where most settled and raised their families, cannot be overstated.

The rich ethnic landscapes Portuguese-Azoreans built in Toronto and other cities are testimony to their resilience and wish to preserve their heritage and culture on Canadian soil and highlight the evolving nature of Portuguese-Canadian identity. Given economic globalization, intense redevelopment pressures and Canada’s ‘demographic revolution’, the question is for how long will these built ethnic landscapes which offer space for everyday activities as well as staging of cultural heritage and social-cultural events will survive in the future? With that said, Portuguese and Azorean immigration has decreased drastically in the last three decades and Canada’s Portuguese-Azorean communities are currently in transition. The generations of Portuguese and Azoreans born in Canada must navigate the coming decades within diverse demographic, social, cultural, political, and economic contexts. There are still many questions about how the next generations will reinterpret these ethnic spaces, and how they will preserve or redefine their heritage for the future. This explains the ‘chronic urban trauma’.

It is appropriate to call for increased research and scholarly work on the Portuguese and Azorean communities in Canada, their “pioneers,” and descendants born in the country. Comparative scholarly work on the rich history of their migratory trajectories, settlement experiences, community formation, integration experiences – including cultural and mother-tongue retention, the “aging” of their communities as well as their “ethnic imprint” on cities and local communities – remains limited. Given the importance of immigration to Canadian social and economic development, immigrant integration has become an issue of concern for Canadian academics and policymakers. Given evidence of rising stress in our cities – from immigrants at risk of exclusion, marginalization, urban poverty, social alienation, or even homelessness to racial tensions — it is crucial that the roles of ethnicity and race be addressed in future studies of Canadian immigrants.

In the ‘age of migration’ the adaptations processes and outcomes of immigrants have become more complicated. How immigrants shape the structure of cities and how these cities, in turn accommodate these immigrants’ culturally diverse needs and preferences is an increasingly important topic. Understanding the development of urban enclaves and ethnic dynamics on the neighborhood scale is becoming increasingly critical as North American communities attempt to successfully integrate immigrants from very different cultures. Research into these relationships must get to the crux not only of immigrant settlement preferences, housing patterns, and work locations, but also of culture, religion, and leisure activities. It is crucial that scholars and policymakers better understand the complexities of immigrants’ integration “trajectories” into their new society, especially focusing young ages and schooling. In this context, its dynamic and prosperous Portuguese-Azorean community has contributed to Toronto’s current reputation as a multicultural “city of homelands” and bears witness to the power of immigration as an engine of demographic and economic growth and social as well educational transformation.

Author Contributions

The author assured the conceptualization, investigation, writing from the original draft preparation until visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

University of British Columbia, Canada.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Albert, I. (2021). Perceived loneliness and the role of cultural and intergenerational belonging: The case of Portuguese first-generation immigrants in Luxembourg. European Journal of Ageing, 18(3), 299–310. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R., Hou, F., Reitz, J. G., & Zhang, T. (2021). Evaluating foreign skills: Effects of credential assessment on skilled immigrants’ labour market performance in Canada. Canadian Public Policy, 47(3), 358–372. [CrossRef]

- Banyard, V., Rousseau, D., Shockley McCarthy, K., Stavola, J., Xu, Y., & Hamby, S. (2025). Community-level characteristics associated with resilience after adversity: A scoping review of research in urban locales. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 26(2), 356–372. [CrossRef]

- Bloemraad, I. (2006). Becoming a citizen: Incorporating immigrants and refugees in the United States and Canada. University of California Press.

- Botelho, M. J. (2021). Reframing mirrors, windows, and doors: A critical analysis of the metaphors for multicultural children's literature. Journal of Children's Literature, 47(1), 119–126.

- Brooks, M., Taylor, E., & Hamby, S. (2024). Polyvictimization, polystrengths, and their contribution to subjective well-being and posttraumatic growth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 16(3), 496–503. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. H. K., Horsdal, H. T., Samuelsson, K., Closter, A. M., Davies, M., Barthel, S., ... & Sabel, C. E. (2023). Higher depression risks in medium- than in high-density urban form across Denmark. Science Advances, 9(21), eadf3760. [CrossRef]

- Collins, P. (2000). Remembering the Portuguese. In C. Teixeira & V. M. P. Da Rosa (Eds.), The Portuguese in Canada: From the Sea to the City (pp. 68–79). University of Toronto Press.

- Da Rosa, V. M. P., & Teixeira, C. (2009). The Portuguese community in Quebec. In C. Teixeira & V. M. P. Da Rosa (Eds.), The Portuguese in Canada: Diasporic challenges and adjustment (pp. 208–225). University of Toronto Press.

- DeSouza, D. K., Lin, H., & Cox, R. B. (2023). Immigrant parents and children navigating two languages: A scoping review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 15(1), 133–161. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J., Sturgeon, B., Huck, J., Hocking, B., Jarman, N., Bryan, D., ... & Tredoux, C. (2022). Navigating the divided city: Place identity and the time-geography of segregation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 84, 101908. [CrossRef]

- Doel, P. (1992). Port O’Call: Memories of the Portuguese White Fleet in St. John’s Newfoundland. Institute of Social and Economic Research.

- Drolet, J. L., & Teixeira, C. (2020). Fostering immigrant settlement and housing in small cities: Voices of settlement practitioners and service providers in British Columbia, Canada. The Social Science Journal, 59(3), 485–499. [CrossRef]

- Eissa, M., & Zeira, A. (2024). The backyard: Cumulative trauma of children from East Jerusalem who were removed from their homes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 153, 106839. [CrossRef]

- Este, D., & Ngo, H. V. (2011). A resilience framework to examine immigrant and refugee children and youth in Canada. In Immigrant children: Change, adaptation, and cultural transformation (pp. 27–50). Bloomsbury.

- Figueiredo, S. (2008). The psychosocial predisposition effects in second language learning: motivational profile in Portuguese and Catalan samples. Revista Internacional de Didáctica de las Lenguas Extranjeras - Porta Linguarum, 10, 7-20. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S., & Silva, C. (2009). Cognitive differences in second language learners and the critical period effects. L1 – Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 9(4), 157–178. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S., Alves Martins, M., & Silva, C. F. D. (2016). Second language education context and home language effect: Language dissimilarities and variation in immigrant students’ outcomes. International Journal of Multilingualism, 13(2), 184–212. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S., Brandão, T., & Nunes, O. (2019). Learning styles determine different immigrant students’ results in testing settings: relationship between nationality of children and the stimuli of tasks. Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9(12), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S. (2019). Competition Strategies during Writing in a Second Language: Age and Levels of Complexity. Languages, 4(11), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S. (2023a). The Efficiency of Tailored Systems for Language Education: An App Based on Scientific Evidence and for Student-Centered Approach. European J. of Education Research, 12(2), 583-592. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S. (2023b). The effect of mobile-assisted learning in real language attainment: A systematic review. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39(4), 1083-1102. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S., Dierks, A., & Ferreira, R. (2024). Mental health screening in refugee communities: Ukrainian refugees and their post-traumatic stress disorder specificities. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 8(1), Article 100382. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S., & Henriques, A. C. D. C. (2024). Practices of Content-Based Instruction in the Voice of Foreign Language Teachers: Looking Inside an Authentic Classroom of Languages Laboratory. The International Journal of Pedagogy and Curriculum, 31(1), 133. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, S., & Petravičiūtė, A. (2025). Examining the relationship between coping strategies and post-traumatic stress disorder in forcibly displaced populations: A systematic review. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 9(2), 100535. [CrossRef]

- Fong, E., & Wilkes, R. (1999). The spatial assimilation model reexamined: An assessment by Canadian data. International Migration Review, 33(3), 594–620.

- Gaspar da Silva, M. (2023). Storytelling embroidery art therapy group with Portuguese-speaking immigrant women in Canada [Groupe d’art-thérapie de récit par la broderie avec des femmes immigrantes lusophones au Canada]. Canadian Journal of Art Therapy, 36(2), 86–104. [CrossRef]

- Gendron, A. (2024). Identity and sense of belonging in second-generation immigrants of Montréal (Doctoral dissertation, Concordia University).

- Gomes, F. (2023). “I go because I don’t have an alternative”: Older Portuguese immigrant women’s experiences accessing and using health care services in Toronto (Doctoral dissertation, Toronto Metropolitan University).

- Hall, C. E., Wehling, H., Stansfield, J., South, J., Brooks, S. K., Greenberg, N., ... & Weston, D. (2023). Examining the role of community resilience and social capital on mental health in public health emergency and disaster response: A scoping review. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 2482. [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, D. (2000). Immigration and the changing Canadian city. The Canadian Geographer, 44(1), 25–43.

- Kobayashi, A., Li, W., & Teixeira, C. (2012). Introduction – Immigrant geographies: Issues and debates. In C. Teixeira, W. Li, & A. Kobayashi (Eds.), Immigrant geographies of North American cities (pp. xiv–xxxviii). Oxford University Press.

- Ley, D. (2010). Millionaire migrants: Trans-Pacific life lines. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Marques, J. C. (2019). Entrepreneurship among Portuguese nationals in Luxembourg. In C. Pereira & J. Azevedo (Eds.), New and old routes of Portuguese emigration (pp. 97–113). Springer. [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, A., & Hinton, D. (2009). Ethnocultural issues. In Post-traumatic stress disorder (pp. 173–185). CRC Press.

- Meligrana, J., & Skaburskis, A. (2005). Extent, location and profiles of continuing gentrification in Canadian metropolitan areas, 1981–2001. Urban Studies, 42(9), 1569–1592.

- Murdie, R. A., & Skop, E. (2011). Immigration and urban and suburban settlements. In C. Teixeira, W. Li, & A. Kobayashi (Eds.), Immigrant geographies of North American cities (pp. 48–68). Oxford University Press.

- Murdie, R. A., & Teixeira, C. (2006). Urban social space. In T. Bunting & P. Filion (Eds.), Canadian cities in transition: Local through global perspectives (pp. 154–170). Oxford University Press.

- Murdie, R., & Teixeira, C. (2015). A two-sided question: The negative and positive impacts of gentrification on Portuguese residents in West-Central Toronto. In C. Teixeira & W. Li (Eds.), The housing and economic experiences of immigrants in U.S. and Canadian cities (pp. 121–145). University of Toronto Press.

- Oliveira, A., & Teixeira, C. (2004). Portuguese youth and Luso-descendants in Canada: Trajectories of integration in multicultural spaces [Jovens portugueses e luso-descendentes no Canadá: Trajectórias de inserção em espaços multiculturais]. Celta Editora.

- Oliveira, G. (2021). Immigrant children’s stories in elementary school: Caring and making space in the classroom. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 15(4), 224–232. [CrossRef]

- Parameswaran, U. D., Molloy, J., & Kuttner, P. (2024). Healing schools: A framework for joining trauma-informed care, restorative justice, and multicultural education for whole-school reform. Urban Review, 56(1), 186–209. [CrossRef]

- Pilipossian, S. (2023). Development and validation of the Armenian-American intergenerational trauma scale (AAITS) (Doctoral dissertation, Alliant International University).

- Pires, R. P., Vidigal, I., Pereira, C., Azevedo, J., & Moura Veiga, C. (2023). Atlas of Portuguese emigration [Atlas da emigração portuguesa]. Mundos Sociais.

- Preston, V., Shields, J., & Akbar, M. (2022). Migration and resilience in urban Canada: Why social resilience, why now? Journal of International Migration and Integration, 23(4), 1421–1441. [CrossRef]

- Qadeer, M. A. (2016). Multicultural cities: Toronto, New York and Los Angeles. University of Toronto Press.

- Rivera, L. (2023). Return to paradise: Understanding the movement from emigration to immigration in the Azores Islands (Master’s thesis, Harvard University).

- Sampaio, D. (2022). Migration, diversity and inequality in later life. Global Diversities.

- Schleifer, B., & Ngo, H. (2005). Immigrant children and youth in focus. Canadian Issues, Spring 2005, 29–33.

- Sithas, M. T. M., & Surangi, H. A. K. N. S. (2021). Systematic literature review on ethnic minority entrepreneurship. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 8(3), 183–202. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48710140.

- Skop, E., & Li, W. (2003). From the ghetto to the invisiburb: Shifting patterns of immigrant settlement in contemporary America. In J. W. Frazier & F. L. Margai (Eds.), Multi-cultural geographies: Persistence and change in U.S. racial/ethnic geography (pp. 113–124). Global Academic Publishing.

- Stamm, B. H., & Stamm, H. E. (2013). Trauma and loss in Native North America: An ethnocultural perspective. In Honoring differences (pp. 49–75). Routledge.

- Statistics Canada. (2022). 2021 census population (Catalogue No. 98-316-X2021001). Statistics Canada.

- Statistics Canada. (2024). Special interest profile, 2021 census of population (Catalogue No. 98-26-0009-2021001). Statistics Canada.

- Sweet, E. L., & Harper-Anderson, E. L. (2023). Race, space, and trauma: Using community accountability for healing justice. Journal of the American Planning Association, 89(4), 554–565. [CrossRef]

- Szkudlarek, B., & Wu, S. X. (2018). The culturally contingent meaning of entrepreneurship is mixed embeddedness and co-ethnic ties. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 30(5–6), 585–561. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K. (2023). The aging of international migrants and strategic transnational practice in later life: Exploring Portuguese seniors in Toronto, Canada. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 67(2), 272–287. [CrossRef]

- Taplin-Kaguru, N. E. (2021). Grasping for the American dream: Racial segregation, social mobility, and homeownership. Routledge.

- Tardif-Grenier, K., Gervais, C., & Côté, I. (2023). Exploring recent immigrant children’s perceptions of interactions with parents before and after immigration to Canada. Children’s Geographies, 21(5), 977–992. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C. (2009). The Portuguese in British Columbia: The orchardists of the Okanagan Valley. In C. Teixeira & V. M. P. Da Rosa (Eds.), The Portuguese in Canada: Diasporic challenges and adjustment (pp. 226–252). University of Toronto Press.

- Teixeira, C. (2010). Gentrification, displacement, and resistance: A case study of Portuguese seniors in Toronto’s “Little Portugal.” In D. Durst & M. MacLean (Eds.), Diversity and aging among immigrant seniors in Canada: Changing faces and greying temples (pp. 327–340). Det Selig Enterprises Ltd.

- Teixeira, C., & Murdie, R. A. (2009). On the move: The Portuguese in Toronto. In C. Teixeira & V. M. P. Da Rosa (Eds.), The Portuguese in Canada: Diasporic challenges and adjustment (pp. 191–208). University of Toronto Press.

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2024). Selected characteristics of the foreign-born population by period of entry into the United States, 2023 American community survey 1-year estimates. U.S. Census Bureau.

- Vaz, E. (2025). Self-organising maps for exploring the change in Portuguese communities in Toronto. In Handbook on big data, artificial intelligence and cities (pp. 243–256). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Vieira, S. I. (2021). There and back in two languages: Intersections of identity, bilingualism, and place for Luso-Canadian transnationals (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia–Okanagan).

- Vieira, S. I., & Teixeira, C. (2023). Ethno-cultural organizations in changing social landscapes: A case study of Portuguese organizations in Toronto. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 55(1), 47–79.

- Vine, J. (2024). Chronic urban trauma, postsecular spaces and living with difference in a city neighbourhood. Migration Studies, 12(2), mnad036. [CrossRef]

- Walls, M. (2023). The perpetual influence of historical trauma: A broad look at Indigenous families and communities in areas now called the United States and Canada. International Migration Review, 59(2), 651–667. [CrossRef]

- Weisleder, A., Reinoso, A., Standley, M., Alvarez-Hernandez, K., & Villanueva, A. (2024). Supporting multilingualism in immigrant children: An integrative approach. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 11(1), 76–84. [CrossRef]

- Yasin, N., & Hafeez, K. (2023). Three waves of immigrant entrepreneurship: A cross-national comparative study. Small Business Economics, 60(4), 1281–1306. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., & Bankston, C. L. (2020). The model minority stereotype and national identity question: The challenges facing Asian immigrants and their children. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43(1), 233–252.

- Zhuang, Z. C., & Lok, R. T. (2023). Exploring the wellbeing of migrants in third places: An empirical study of smaller Canadian cities. Wellbeing, Space and Society, 4, 100146. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).