1. Introduction

According to the World Migration Report (2024), by the end of 2022, there were 117 million people living in forced displacement because of war, conflict, gender-based violence, and the climate crisis [1]. In its 13th year, the Syrian refugee crisis is the world’s largest cause of forced displacement due to war and violence, with over 5.3 million Syrian refugees in Türkiye, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt, and North Africa [2]. Syrian refugees have the highest resettlement needs globally, and resettlement remains the most viable solution to forced displacement [2].

Approximately 1 in 5 people (20%) in settings affected by conflict have a mental health condition [2]. Among people who have been displaced—that is refugees, asylum seekers, and people who are stateless or undocumented—evidence suggests that their experiences put them at risk of increased trauma and negative mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychosis [2,3]. In addition, the mental health impacts of forced displacement are dependent upon intersecting pre- and post-migration financial, political, and social factors [4,5,6]. Research suggests that trauma and emotional suppression play a mediating role in pre-displacement refugee mental health, while country of residence is a potential moderator for severity of mental health conditions [4]. However, a narrow focus on refugee trauma does not adequately respond to the complexities associated with refugee mental health [5]. In both high-income (HIC) and low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), governments have not adequately planned for refugee mental health service provision that considers the economic, social, and political effects of displacement on refugee mental health [2]. This policy gap may be a result of lack of attention to the social determinants of refugee mental health [7,8]. Importantly, refugee mental health and psychological wellbeing are associated with gender-based distress that intersects with contextual factors such as social supports, immigration policies, and access to healthcare [4,5,6]. Emerging research shows that most refugee men experience significant vulnerabilities related to exploitation in labor markets, loss of employment, ack of legal status, and inability to support their families in both pre- and post-migration contexts [9,10,11,12].

In 2014, almost three million Syrians lost their jobs, and 30% of the Syrian population were reported to experience abject poverty [13]. In the context of war, violence, and displacement, many Syrians, like other refugee groups, reside in host countries—that is, countries that offer temporary protection status until a refugee claim is approved by a country offering resettlement programs. Türkiye hosts the largest number of Syrian refugees (over 3.5 million), followed by Lebanon (over 814,000) and Jordan (over 660,000) [13]. Even though the countries admitted Syrians as refugees for settlement, these refugees face serious public stigma [14,15]. For example, government migration policies in Türkiye have evolved from welcoming and pro-integration (2011–2018) to entirely return-focused (after 2021), which has made Syrians—some of whom have resided in Türkiye for more than a decade—experiencing increased precarity [15].

Studies have found that Syrians residing in countries of settlement with policies hostile to refugees’ experience discrimination, poverty, gendered vulnerabilities, barriers to accessing employment, and exploitation at the workplace, all of which significantly impair their mental health [12]. Social factors impacting Syrians include gender bias and stereotypes that position men as breadwinners outside of the home, whereas women are associated with providing caregiving. Scholars have argued that gendered stereotypes have masked the nuanced vulnerabilities of refugee men, perpetuating the idea that male refugees are a threat to their countries of settlement, and reinforcing the stereotype of refugee women as victims and in need of care [4,9,16,17,18]. The refugee crisis has also created anti-immigration rhetoric, specifically in settlement countries’ mainstream media and politics, as Syrian men are stereotyped as ‘bogus’ refugees and as perpetrators of violence and of Arab patriarchal norms [17,18].

Trends in the literature suggest that Syrian men displaced by war, experience mental health problems related to barriers to employment. In urban Jordan, a rapid community assessment consisting of both a survey of 240 Syrian households with a total of 1,476 members and 89 focus groups representing 534 households, showed that 45% of adult males had some form of employment but 55% self-reported being unemployed, and no women reported working outside the home [9]. Of the total households, only 34% reported an income. Syrian men surveyed expressed feelings of depression and generalized anxiety over the safety of their families and concerns about poor working conditions and exploitation in low-paying jobs [9]. Political and social factors related to long-distance travel to find work, time away from family, and mandatory military services for Syrian men have also affected their prosperity and pursuit of education, resulting in increased feelings of shame and depression [10]. These findings support other studies showing gendered impacts of forced displacement, as the disruption of gender and cultural norms has forced Syrian women to become providers for their families, which may increase gender-based violence [9,10,12]. The root causes of gender-based violence can be related to masculinity and structural processes that reinforce gender inequalities [5,16].

In the Canadian context, the Syrian refugee crisis has led to the resettlement of more than 40,000 Syrians between 2015 and 2018, based on their need for protection (i.e., safety and security) [19]. In Canada, refugee resettlement can be government-sponsored (GARs), privately sponsored (PS), or part of a Blended Visa Office-Referred (BVOR) program. In the GAR program, the Canadian government provides to Syrian refugees resettlement support including one year of financial and housing support. Syrians who are PS also receive settlement support, including financial and social support for up to one year, but this support is provided through groups of volunteers [19]. The BVOR program involves support from both the government and private sponsors, who each supply up to six months of support [19]. Studies have found that, among these three groups, Syrian GARs experience the lowest household income, lowest pay or precarious employment, and most insecure or unstable housing [20,21].

Barriers to employment remain a significant challenge for Syrian men during resettlement. This suggests that mental related stress must be viewed longitudinally to include both pre and post settlement contexts. The Syrian Lived Experience Project, led by the Environics Institute for Survey Research in Canada, conducted a survey with Syrian refugees (n = 305) who arrived in Canada between 2015 and 2016 [21]. Their survey findings showed that almost half of Syrians were employed full- or part-time (including those who were self-employed), which is below the level for the Canadian population at large. Most of those employed were working in sectors that typically provide entry-level opportunities, and only one in five reported being in a job or occupation that matched their education, skills, and experience [21]. Syrian men were more than three times as likely as women to be working full-time (51% versus 15%), with women more likely to be a student or to not be looking for work (45% versus 13% among men) [21]. The same study found that just one in five (21%) said their current work fully matches their qualifications. These findings support other research that shows that lack of credential recognition may also impede employment and fit with previous occupations or experience, leading to a trend in which many newcomers engage in non-standard employment known as ‘platform’ or ‘gig’ work [21,22]. Through these platforms, work is performed offline (e.g. ride-hailing, food delivery services); the work offered through these platforms is often viewed as a low barrier to labor market integration [22]. Although “platformed distinction” work may enhance economic integration in the short term, it also creates positions of disadvantage and economic downgrading that are specific to immigrants and that perpetuate gender disparities and work precarity [22,23,24].

Despite the growing evidence that shows the negative effects of economic, social, and political practices on refugee mental health, a nuanced and balanced gender-based analysis is lacking. A gap in gender-based analysis may be related to traditional notions of masculinity, which obfuscate men’s vulnerabilities and risk factors for mental health. Moreover, masculinity may be an overarching structure that is negatively affecting refugee men’s mental health. A study of Syrian refugees (n = 25) in Istanbul (Türkiye) and Buffalo (USA) explored empowerment and gender roles among Syrian refugee men and women [16]. The findings showed that financial pressures and problems of survival changed cultural, gendered expectations between Syrian men and women. The lack of employment opportunities for Syrian men in Istanbul reduced their control over their economic condition and their ability to provide for their families. The need to afford food and housing created a catalyst for change among Syrian women, who then sought work in Istanbul; in this context, Syrian men felt guilt, anger, and hopelessness. In contrast, in Buffalo, most Syrian women were not working, but were able to receive support through non-economic streams such as educational opportunities and legal systems that supported their empowerment, while Syrian men were all engaged in either full- or part-time employment [16]. The study highlights the importance of context and the policies and supports that differentially impact gender roles and mental health of Syrians in resettlement.

The gendered and economic barriers impacting Syrian refugee men’s mental health are intensified in post-migration resettlement contexts. Discrimination, stigma, and normative masculinity make it particularly challenging to elicit refugee men’s vulnerabilities and stressors associated with mental health [9,10,16,26]. Studies on Syrian men and mental health in host countries suggest that Syrian refugee men struggle with mental health issues, including trauma, and are less likely than women to access mental health services due to stigma [10]. Stigma continues to be the main barrier for help-seeking for men in Arab social and cultural contexts [9,10,27]. Similarly, mental health stigma among Syrian men is also related to cultural norms of masculinity in which men may not acknowledge vulnerability or weakness [28]. Studies with racialized men has been linked to broader processes of normative masculinity, in which strength is often equated with stoicism and passed down from one generation to the next [29,30].

Syrian refugee men ground their identity in their roles as providers and fathers [31]. Stressors of acculturation, changes in gender roles, and adjustments in gender role expectations have significant impacts on refugee men’s mental health, particularly for families in which fathers are not the main contributor to household income [26,32]. Prior research on men’s mental health and employment has shown that both life transitions and parenthood are predictive factors for depression among men [33,34]. A meta-analysis of unemployment and mental health showed that the effect of unemployment on mental health is tied to masculine identity, and that male blue-collar workers are more vulnerable to negative effects of unemployment than women or other social groups [34]. Moreover, chronic and acute stressors related to unemployment can lead to severe negative mental health consequences, as norms of masculinity may contribute to men’s suicidal ideation, particularly for men who strongly identify as ‘self-reliant’ [34,35]. Compared to refugee women, refugee men may have less access to resources and less dedicated support for their mental health, contributing to lower help-seeking patterns. When men do seek out help, it is more likely to be from peers, but there is often a lack of formalized peer support networks for men and boys [11,28,29,36].

Economic integration is tied to gender stereotypes, which can affect the vulnerability of men and women in different ways; however, men’s voices are only starting to be heard in the discourse on forced migration and mental health. The purpose of this research is to understand Syrian men’s perspectives on the factors that shape their mental health and wellbeing in the context of their resettlement in Canada, with a specific focus on the effects of employment on their mental health. The research questions guiding this study are as follows:

What do Syrian men perceive as important factors in shaping their mental health and wellbeing in the context of their participation in employment?

How does unemployment or underemployment impact Syrian refugee men’s mental health and wellbeing?

What are Syrian refugee men’s gendered experiences of economic integration?

2. Materials and Methods

This research was guided by a community-based participatory action research methodology, an inclusive process that leverages the strengths of research participants for the purpose of positive social change [37,38]. Photovoice, a participatory arts-based method, is used to tell stories through photographs and is increasingly being used in research with people who experience forced displacement, and in contexts in which difficult-to-discuss topics, such as mental health, are the subject of the investigation [40,41,42]. In this study, photo elicitation interviews were also conducted to guide the Photovoice process. Photo elicitation is a qualitative interviewing technique; we have used it to prompt and guide our in-depth interviews with Syrian men [43]. This study occurred between May 10, 2022, and May 9, 2024, and included three phases:

Phase I – partnership building and community participation;

Phase II – data collection and analysis; and,

Phase III – knowledge mobilization.

2.1. Phase I – Partnership-Building and Community Participation

In this phase, we developed a community advisory board (CAB), recruited participants, and provided training in Photovoice through a workshop. The CAB promoted researcher and stakeholder engagement and helped community members both to voice concerns about and priorities in the research and to provide guidance on research recruitment and knowledge dissemination [45]. CAB members included peer researchers, research team members, counsellors, employment specialists, and staff members in not-for-profit immigrant service organizations. Over the course of the research, four community advisory meetings were held: two meetings in 2021–22 and two meetings in 2022–24. In these meetings, CAB members discussed methods, approaches in the study, outcomes, and knowledge dissemination.

Two Syrian men with refugee backgrounds were hired as peer researchers to build trust and engagement throughout the research process. Peer researchers are trained to provide support to others who share similar experiences [47,48]. The two peer researchers in our study assisted with translating and interpretating all materials from Arabic to English, co-developing the Photovoice workshops, recruiting participants, obtaining informed consent, and co-authoring published materials. The peer researchers also participated in the study as interviewees and in the Photovoice sessions. This process facilitated mutual sharing of men’s stories.

Following the first CAB meeting, participant recruitment was facilitated by an information session at an immigrant service organization that provides newcomer employment programs connecting refugees to employers. The not-for-profit settlement agency assisted recruitment through a poster and word-of-mouth recommendations. Syrian men who arrived in Canada through all three immigration streams—GAR, PS, and BVOR—and who were between the ages of 19 and 65 were eligible to participate in the study.

A total of 15 refugee men from Syria attended the information session and were provided information about how to contact the peer researchers through WhatsApp Business on their smartphone. From the information-sharing event, nine Syrian men were recruited to participate in the study; with these recruited participants and the two peer researchers as participants, our study had a total of 11 participants. These 11 men were invited to participate in a 2.5-day Photovoice training workshop that provided information about the ethics of using Photovoice and the use a camera or smart phone, and offered some prompts to guide their photography. Prompts for taking photographs included pictures of the men’s work, pictures that challenged or supported their mental health, and pictures that supported resilience and wellbeing. Participants were also provided with Photovoice worksheets so that they could journal and make notes with their photos.

2.1.1. Participants

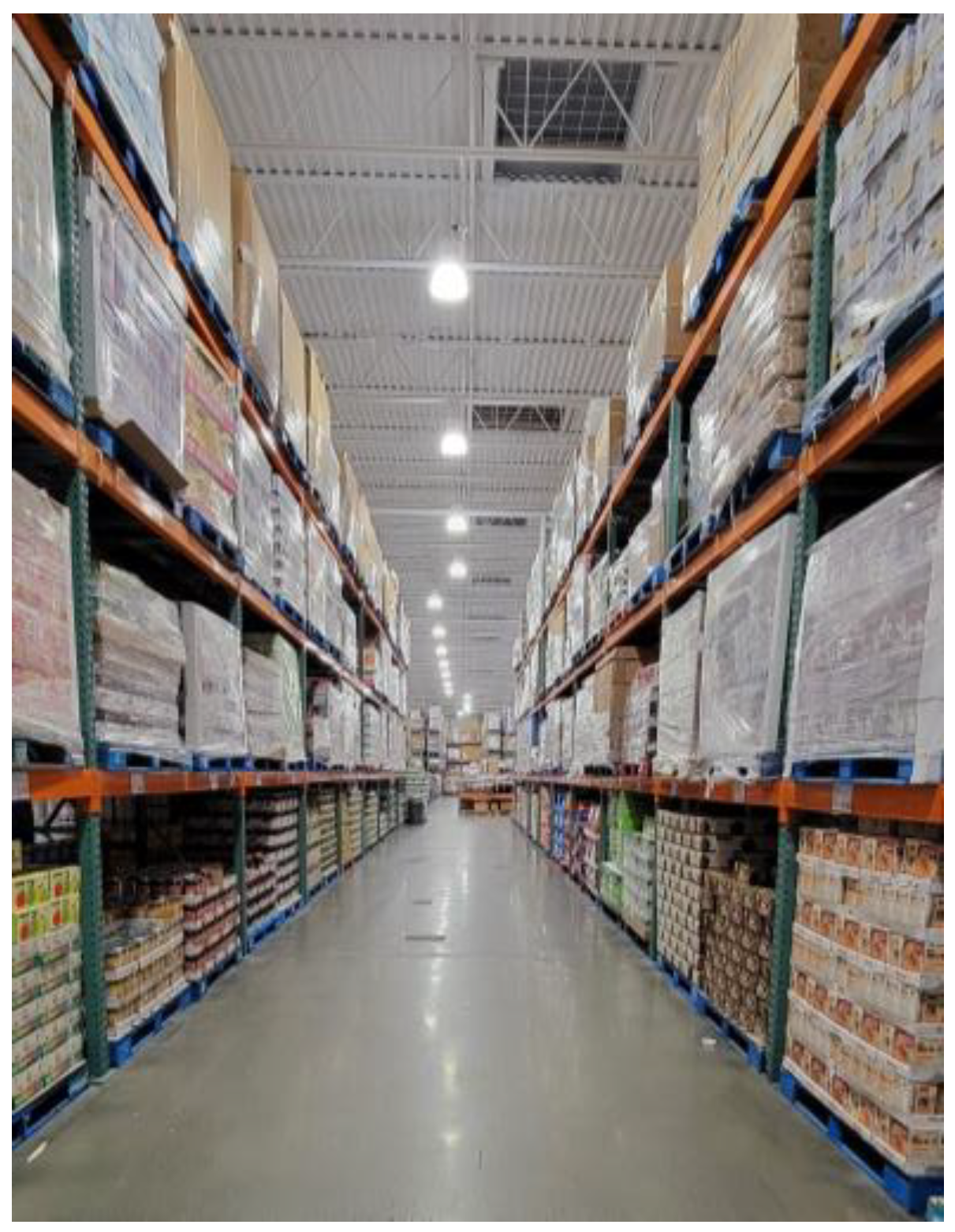

The mean age of the participating men was 39.1 and their ages ranged from 21 to 51 years. All men were in rental housing during the study, with 6 of 11 men residing in subsidized housing. All men self-identified as Syrian, and one identified as a Palestinian refugee living in Syria. Only one participant was born outside of Syria, in Kuwait. Most men had completed a high level of education—a master’s or bachelor’s degree. Nine out of eleven men arrived with nuclear families; two men were single. Their occupations and professions included student, civil engineer, dentist, musician, agriculturalist, architect, factory worker, electrician, chartered accountant, baker, and customer service provider. Although eight out of eleven men were employed, only two were employed in their chosen profession. Many men described working multiple jobs as, for example, a delivery driver, Uber driver, cook, painter, and shelf stocker at a food distribution warehouse. Most identified as Muslim; two were Christian, and two identified as having no religion or as atheist. During the study, six men had already received Canadian citizenship status and five were permanent residents. Six out of 11 men arrived under government-assisted refugee status, three were PS refugees, and two arrived with asylum status. No men arrived under BVOR status. The average approximate household income was

$42,000/year, and the average family household had 3.3 people. The small family size may account for the fact that most participants had extended and other family members who had not received refugee status in Canada. All the men had good conversational English, and their average Canadian Language Benchmark was level 6 [46]. All 11 men arrived in Canada between 2016 and 2022, with four arriving during the COVID-19 pandemic. The men’s sociodemographic data can be found in

Table 1.

2.2. Phase II – Data Collection and Analysis

This phase consisted of a photo-taking period, the photo elicitation interviews, and a second Photovoice workshop. Following the Phase I Photovoice training workshop, the men engaged in photo-taking activities, which consisted of taking photographs on their smartphone or camera over a two-month period (August–September 2022). The men also had the option of sharing photographs that they had previously taken. Eleven photo elicitation interviews occurred between September and November 2022. All but one photo elicitation interview occurred online over Zoom; those same 10 interviews were conducted in Arabic with an interpreter. The in-person interview was conducted in English. Prior to the interviews, the men uploaded their photographs onto a secure shared drive so that they could be shared easily during the online interviews for further discussion. Detailed notes were taken during the interviews to document which photographs the men wanted to discuss and their relevance to the study objectives. Interviews lasted 60–90 minutes, were translated verbatim into English and then these transcripts were uploaded into NVivo Version 12 data management software.

An inductive, qualitative descriptive analysis was used to code the interview data and to develop themes across the data sets—that is, to link the photographs with the developing themes [50]. The theoretical framework of intersectionality was used to capture the multiple dimensions that structure the men’s mental health, including their experience of employment and other axes of inequity [51,52]. The central premise of intersectionality is that people’s lives are multi-dimensional and complex. Lived realities are shaped by different factors and social dynamics operating together; therefore, identity-related categories are not static and can change dependent on context [51,52]. Importantly, intersectionality can provide a nuanced, multi-level analysis that links individual experiences with broader structures and systems, thereby revealing how power relations are shaped and experienced [53]. In this research, we used an intersectional lens—analyzing the interlocking inequalities of migration experience, gender, job precarity, and (non-)belonging, amongst other categories—to examine Syrian men’s social identities in relation to the broader pre- and post-displacement stressors that structure their mental health—that is, financial, political, and social structures.

The study PI developed preliminary codes to find patterns of meaning based on the Syrian men’s stories and their photographs. The PI then clustered the codes together to develop candidate themes to capture multiple facets of the men’s experiences. Candidate themes were sorted and linked to the photographs the men described as relevant to the research study questions. Applying an intersectional lens meant that candidate themes could capture multiple facets of an idea or concept and apply it uniquely to men’s life experiences. For example, photographs could be matched with multiple themes as they may capture more than one meaning. After the interview transcripts and photographs were sorted through a preliminary analytic process, the study PI created eleven individual Photovoice workbooks to capture key photographs and corresponding themes unique to each of the men. The workbooks were used to further validate and co-construct meaning of the photographs in the second Photovoice workshop. Through this process, the men provided their interpretation of the photographs in either Arabic or English and identified which photographs they wanted to use for knowledge dissemination. The participants could also add concepts or ideas that were relevant or missing.

A reflexive thematic analysis further guided the meaning and interpretation of the study findings [54]. By using this type of analysis, the peer researchers and the study PI collectively shared experiences of coming to Canada from diverse Arabic cultural backgrounds—the peer researchers being from different regions in Syria, and the study PI having Palestinian heritage—with the 11 research participants. The reflexivity of the researcher’s position and experiences promoted cultural safety and thereby better enabled the men to share their stories. Through the process of sharing individual subjectivities, the men shared their collective experiences and interpretation of their photos. During this second Photovoice workshop, the study PI and peer researchers also created a PowerPoint presentation to introduce the themes, describe their meaning, and discuss their links to the photographs.

Both methods—photo elicitation and Photovoice—were used to develop an in-depth analysis of these men’s perspectives about the factors that shaped their mental health and experiences of employment integration.

2.3. Phase III – Knowledge Mobilization

This stage of the project consisted of raising awareness of Syrian men’s experiences of employment, migration, and resettlement, and these experiences’ impacts on their mental health. This phase included an online meeting with all the men to discuss how the men wanted to disseminate the knowledge. During this phase, all 11 men participated in co-developing a digital storybook that provided recommendations for employers and settlement counselors on inclusive, gender-responsive employment for men from Syrian refugee backgrounds. In addition, three of the men participated in a co-developed video, and peer researchers co developed an online brochure. The findings of the research were shared with the CAB in the form of a digital storybook and a PowerPoint presentation; these outputs were then shared with staff settlement agencies that provide employment and counseling support services to refugee men. The co-developed video was embedded in the digital storybook, which was then shared across local settlement agencies and networks.

2.3.1. Ethics

This study received ethics clearance from the university’s Human Research Ethics Board (#21-0538). Written and oral consent was obtained from all research participants, and consent was ongoing throughout the project. Each of the 11 men, including the peer researchers, received a $50 dollar honorarium for each hour of work, including the photo elicitation interviews, Photovoice workshops, and meetings. All in-person Photovoice workshops included breaks for prayers for those who identified as Muslim, culturally relevant food, child-minding support, and renumeration of transportation costs. Due to the highly stigmatized nature of mental health, participants’ privacy and anonymity have been respected by removing participants’ names and replacing these with code numbers in the reporting of the results.

3. Results

Shaping Syrian Canadian men’s mental health in the context of their resettlement in Canada are five intersecting themes: 1) language barriers, 2) time and stage of life, 3) isolation and loneliness, 4) belonging and identity, and 5) gendered stress. The findings highlight how these men’s identities are shaped and renegotiated through structural conditions of resettlement in the Canadian context.

3.1. Language and Literacy Barriers: “A Person is Protected if They Have a Strong Language”

Most men considered the English language to be their biggest barrier to accessing meaningful employment in Canada. For some of the men, English language proficiency created a sense of precarity and vulnerability during resettlement. As one man explained:

“It's tough to see the war, but just do not give up. Like, keep trying … because like sometime, when I came here, I opened some website to look for a job, but when I see the job description and they're all in English and I barely understood some English, … and just give up. Oh, it's hard to find a job if I can’t understand the job description. … I give up a lot.” (N5)

Not giving up and overcoming barriers were normalized for some men who had survived war and displacement. The need to establish oneself and not give up speaks to these men’s resilience. However, English competency made some men vulnerable to exploitation and discrimination. This view was shared by another participant:

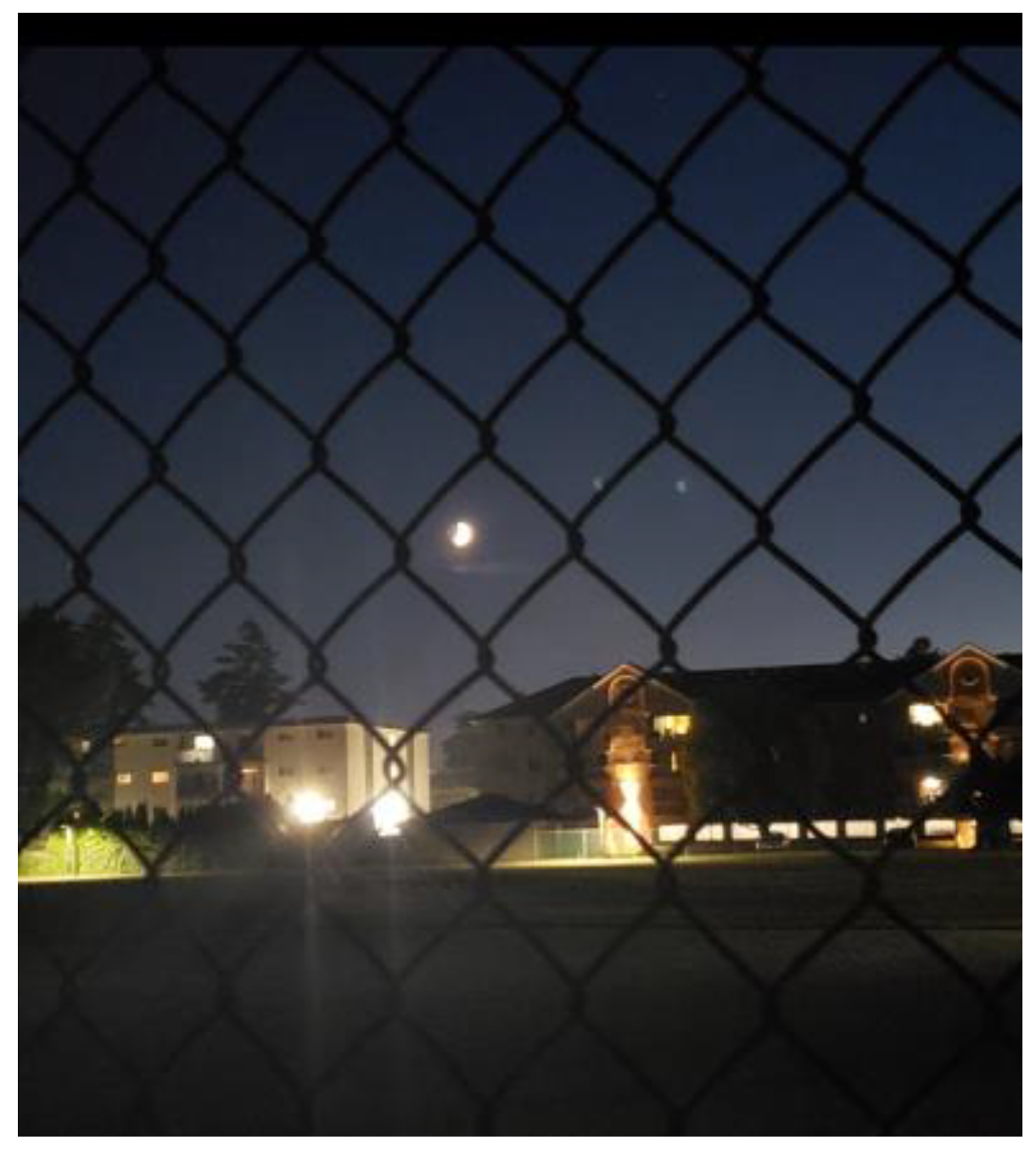

“I looked for work a lot and tried working. Work needs strong language ability. A person is protected if they have a strong language. If one’s language is minimal, ‘half in half’ or less, then you are exposed to everything—exploitation and persecution. This is why I am doing this part-time job, because it does not require too much English ... This goal for me … [Continues in Arabic] meaning this is my hope, I came to Canada with zero English … but I did not give up. I learned and reached level four. I took my citizenship. I tried to work and contribute and interact with society. I faced a lot of challenges… End of the day, I tried focusing on my children, and invest in them… I took this photo from the same area, near the home. The photo includes the moon, and I captured it behind this barrier. I consider this barrier my language barrier, and the moon my hope.” (N1)

The participants were sensitive to feelings of persecution and exploitation because of war and displacement. When describing their resettlement, the men spoke about ‘not giving up’ and focusing on their children’s future. Having hope for their children meant that some men gave up perusing their ambitions or professions to support their children’s future.

Most participants engaged in low-wage jobs that did not require high-level English, because they felt that they would experience greater exploitation in high-level jobs which generally required high levels of English. Other men felt discriminated against when working because of their lack of English: “So that makes you feel a bit annoyed. And why are you discriminating on me because of my accent or lack of English?” (M1)

Working for less money and working part-time were protective mechanisms that made some men felt less vulnerable:

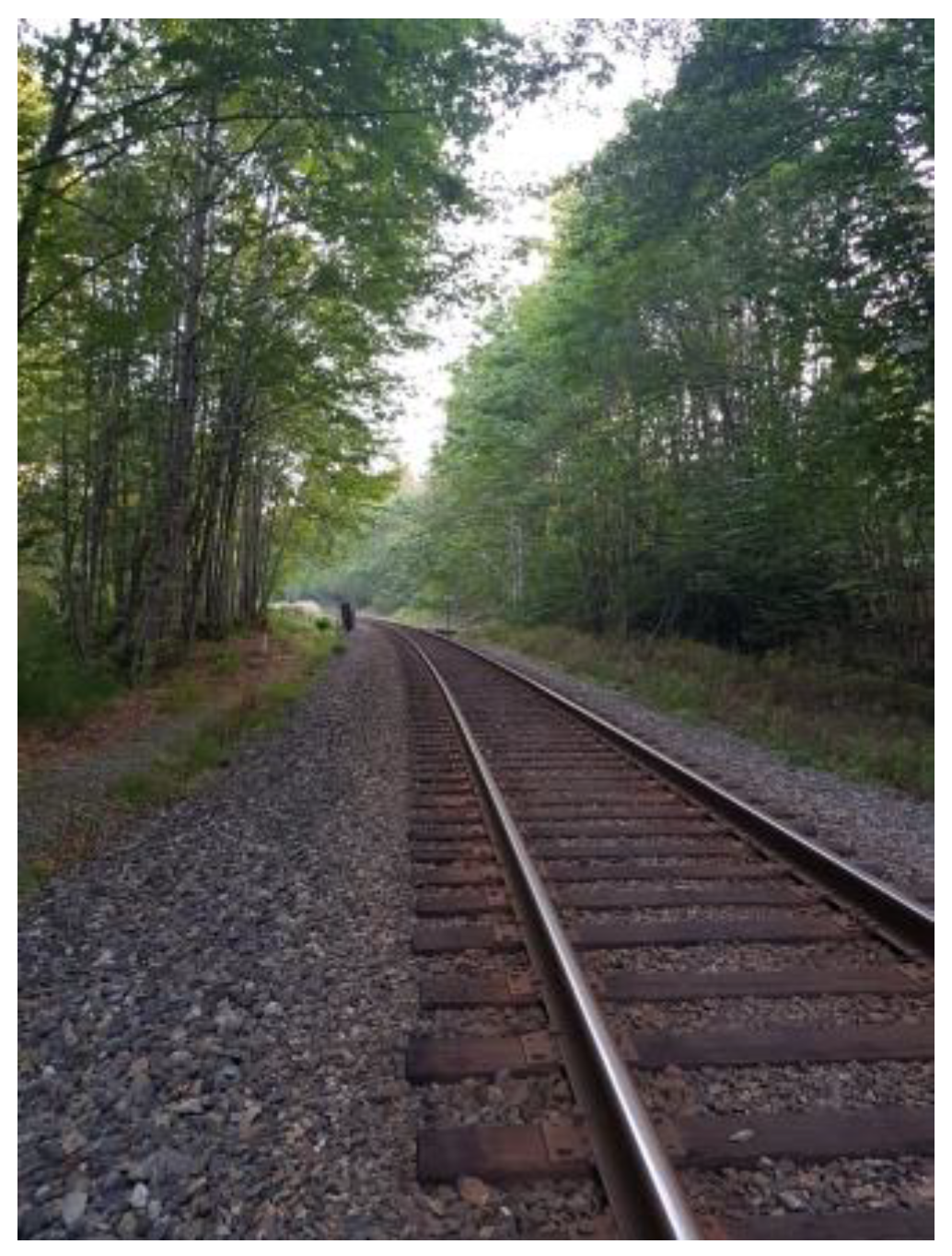

“Unfortunately, now we are forced to work any job, which is causing us problem. Any job you want lets you down due to experience here in Canada. We are not getting an opportunity to work in Canada. So where do we get started if we cannot access any Canadian company? We cannot. The significant barrier is language … I applied to work [name of store]. … and I did not get recruited. … feeling down and upset. Again, with the language barrier obstructing our efforts. Why we are being tortured with the language, unable to learn, and what is the reason? … Those wood pieces in the middle of the track represent our English learning journey. We are standing on the first four or five tracks. … for us to work here like proper human beings … I still have a long steps and long way to understand the language in Canada.” (M1)

Similarly, another Syrian man described barriers he experienced as invisible:

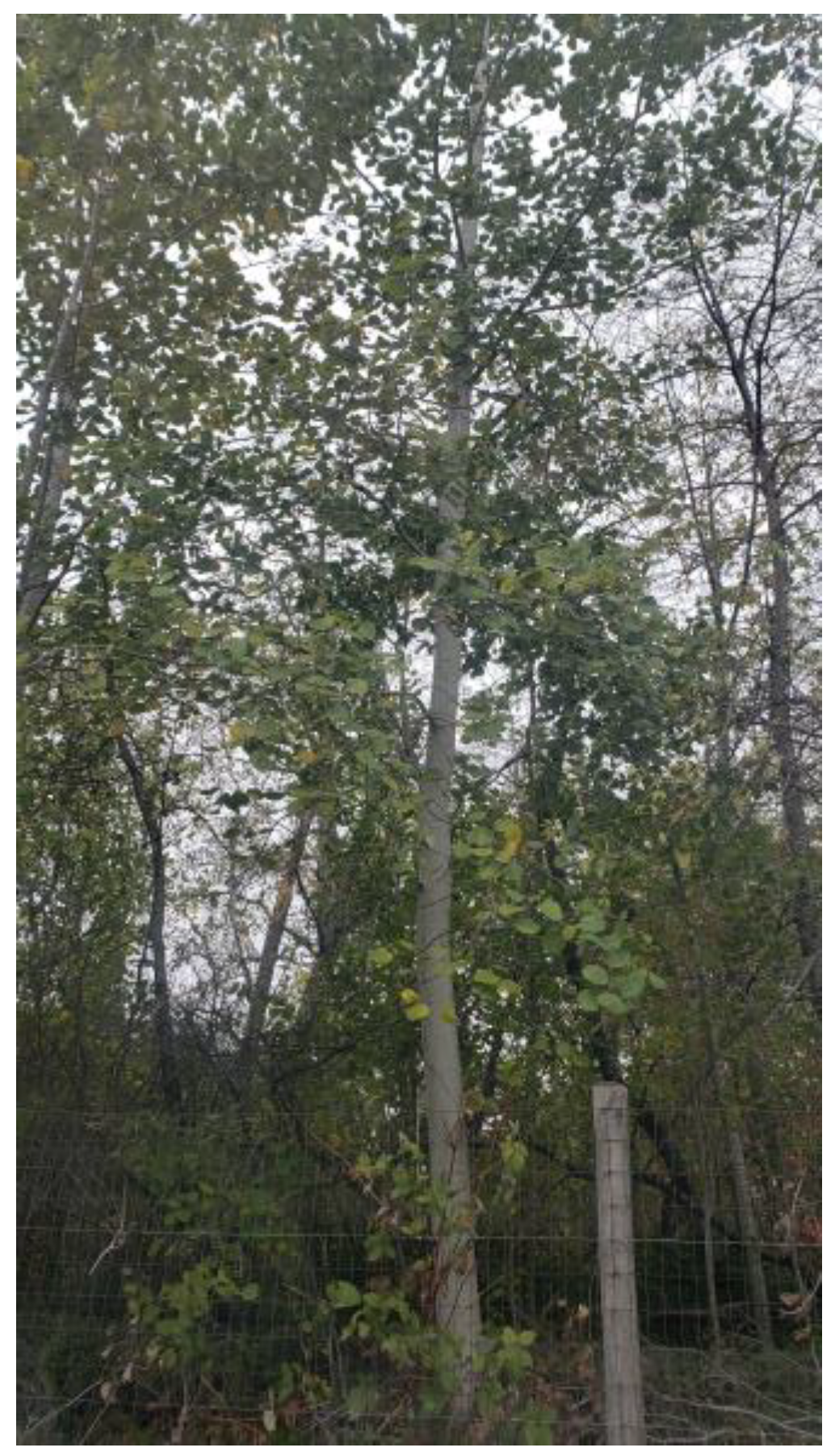

“My wife and me study hard and to gain language and a lot of things we did actually … I'm here in Canada. I'm in the … paradise, promised land. … But there are barriers, barriers, barriers. Let me explain in another way. I said it because this wire is very tiny and like, you will not recognize them until you will be closer and closer to the fence. OK? … You can't touch everything. But when you be there, you can’t go and touch that tree, because this fence in front of you. You can't see it.” (M3)

Overall, most of the men felt isolated and excluded because of their lack of English language proficiency..

3.2. Time and Stage of Life: “I Don't Feel Secure at the End of My Life”

For many of the Syrian interviewees, time and stage of life posed additional challenges to obtaining meaningful employment and thus economic stability. These factors also placed additional pressures on these men and harmed their self-image.

“Yeah, I can’t, I don’t have a lot of time for English, and I need to work, I need to make money for my expenses, my family in Syria expenses—I have a lot of expenses. And … how many years I need to spend for change my level from example six to twelve, and we will access for ISLTS or TOEFL. I need maybe two or three years, right? … Like … don’t have money and [I] don’t have time for certificate. [I] work now with delivery … more ten thousand deliveries in Canada with Skip [the Dishes], Door Dash, and Uber Eats … I lost two cars … because the motor is broken because every day, ten-hour drive. … Now we can’t work … its very expensive … a lot of expenses for maintenance and price for delivery is very low, three or four dollars for one trip, like my hour, eight or ten dollars—I can’t continue work.” (N2)

The same man explained that he felt pressured due to his age and stage of life as hard work pre-migration made him feel older: “I can imagine, yeah, so just, yeah, so this is like people, they become older than they look. Like, so, they are younger, but look like older, so that’s why … if someone looked at this picture, they all assume they just more than fifty or sixty years old, but they are—they are so young” (N2).

By holding multiple jobs and performing platform-based work, some participants were able to overcome the barrier to employment that is a lack of English language proficiency. Study participants also experienced challenges in knowledge-based economies, which require other skills and literacy. For example, one participant explained that the context of displacement affected the education, and skills needed for entering the knowledge-based economy:

“But the age plays a big challenge for us, for all of us and even for studying … like when you go to study with—like, most of the guys are like, for example, English typers long time ago. So you can tell the difference when I'm like typing slowly and the others like typing fast, or like, I like—I was the only guy with like a notebook and the pen. The others were, like, taking notes through the typing. Right?. So, it was challenging.” (M2)

This participant continued to explain that not having computer skills was related to his previous education prior to coming to Canada, and affected his ability to find a job:

“I think the typing skills comes with the younger age … like trained better and, like, high schools, or like, especially with, like, different type of alphabet. And I'm talking about, like, totally different alphabet. … You have to think about, like, what you are typing. Are you writing correct? You know, like. when I write, for example, the paragraph without looking at the screen, I would be like making a lot of red lines under the—under the words. … to be honest, it's holds you back a bit … to find a job.” (M2)

It was difficult for these men to be able to work in their chosen profession because doing so in Canada requires different sets of intellectual skills that they felt they did not have the time to learn. Some men felt that their age and stage of life made it more challenging to gain the skills required in their profession. Another participant explained his perspective on how age and stage of life affected his ability to find work in his chosen profession:

“Because here you cannot work as an architect in designing, unless you know how to deal with the computer programs I don't have. You have to learn it from scratch to learn. I don't have time. I'm not prepared to go through it, because I'm now 50 years old … It will take me a long time, and I am very practical. I don't like working on computers. I like to move and be on site and make a project … planning for the project. This is what I mean most of my life.” (M4)

Most men simply felt they did not have time to learn the new skills required to get the types of jobs they wanted. This lack of time caused some men to look for alternative occupations—that is, jobs that matched their literacy and other skills.

A significant finding that impacted these men’s mental health and psychological wellbeing was having financial security as they age. For example, one participant described feeling behind and unable to save for his retirement:

“I don't see a retirement for me, I. Because starting from this age, you lost, for example, like 20 years of the pension plan or retirement plan. So, I don't believe that … will be enough to survive, and I can tell that from seeing at work people who are 70 years old or something still working hard … when I look at those people, I feel like, ‘OK, that's my end.’ … Those people were, like, working since the age of 20 in this country. So, they are building their retirement plan … But, I don't feel secure at the end of my life. … So, they are using RVs as a house now, because it's impossible to buy a house.” (M2)

Most participants felt pressured to secure funds for their future, which seemed impossible given their wage and the high cost of living. For middle-aged men, their age seemed to represent a lack of opportunities:

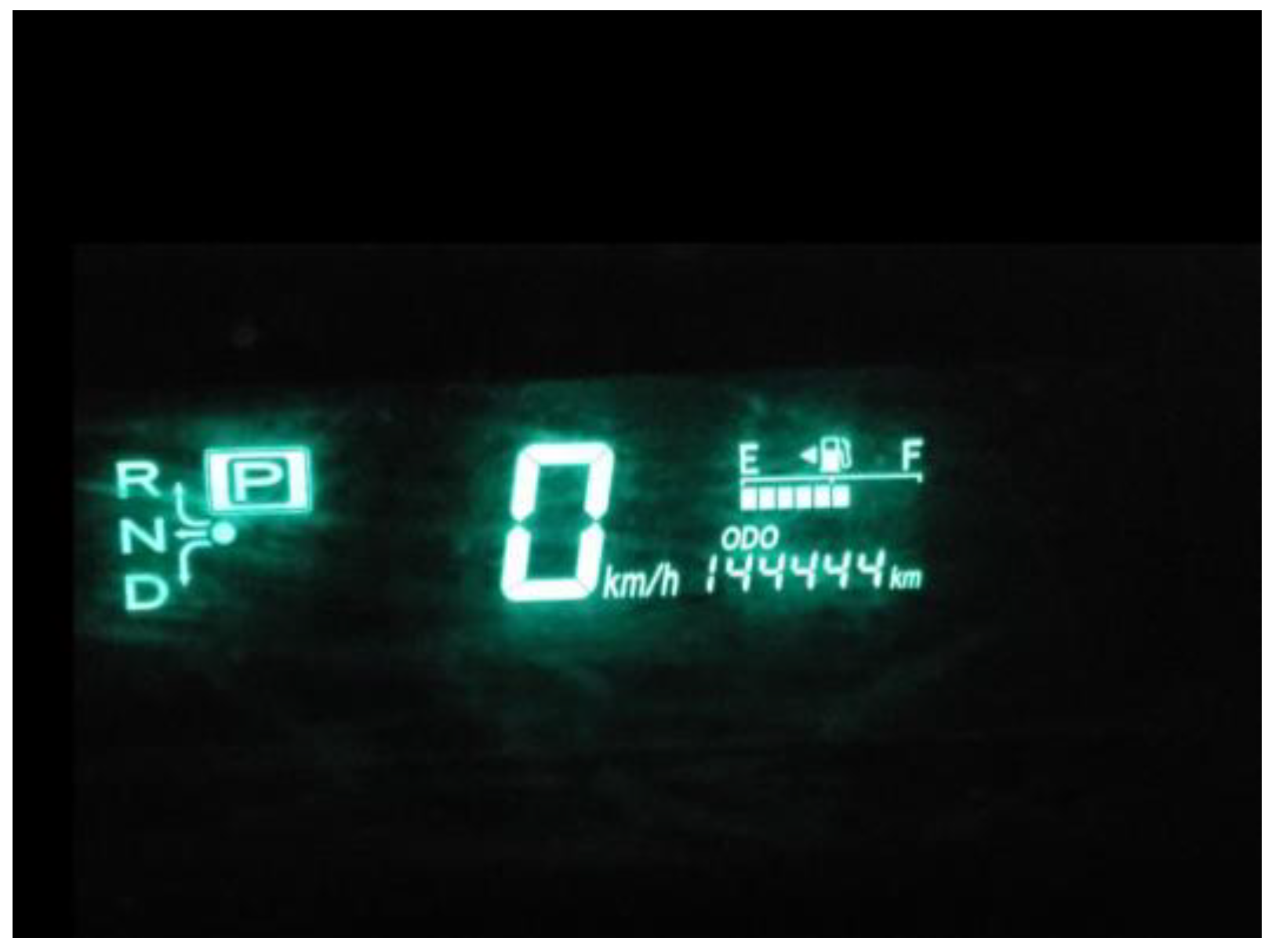

“I recently got an old car that drove hundred and a bit. The meaning and metaphor is that days are passing by. I felt sad when it reached this number, not due to the car: we are aging, and time is passing … when we are youth, opportunities are much more, in comparison to when people are above 45.” (N1)

Similarly, another man explained how working multiple jobs, caring for his personal needs, and finding balance affected his mental health:

“I have to go, like, a minimum of three or four days a week, because I'm in this phase of my life is that I have to focus on my, my physical and mental health. So, the gym is not—is not something extra I'm doing. It's essential because, after 35, your body starts to go down, and I'm almost 30, and it went so fast. I, like my entire life, …my 20 to now—till now, like this. I didn't have the time to go to the gym. I didn't have the time to think. I was just me going and fighting.” (M5)

The factors of time, stage of life and language barriers shaped the participants’ experiences of employment integration.

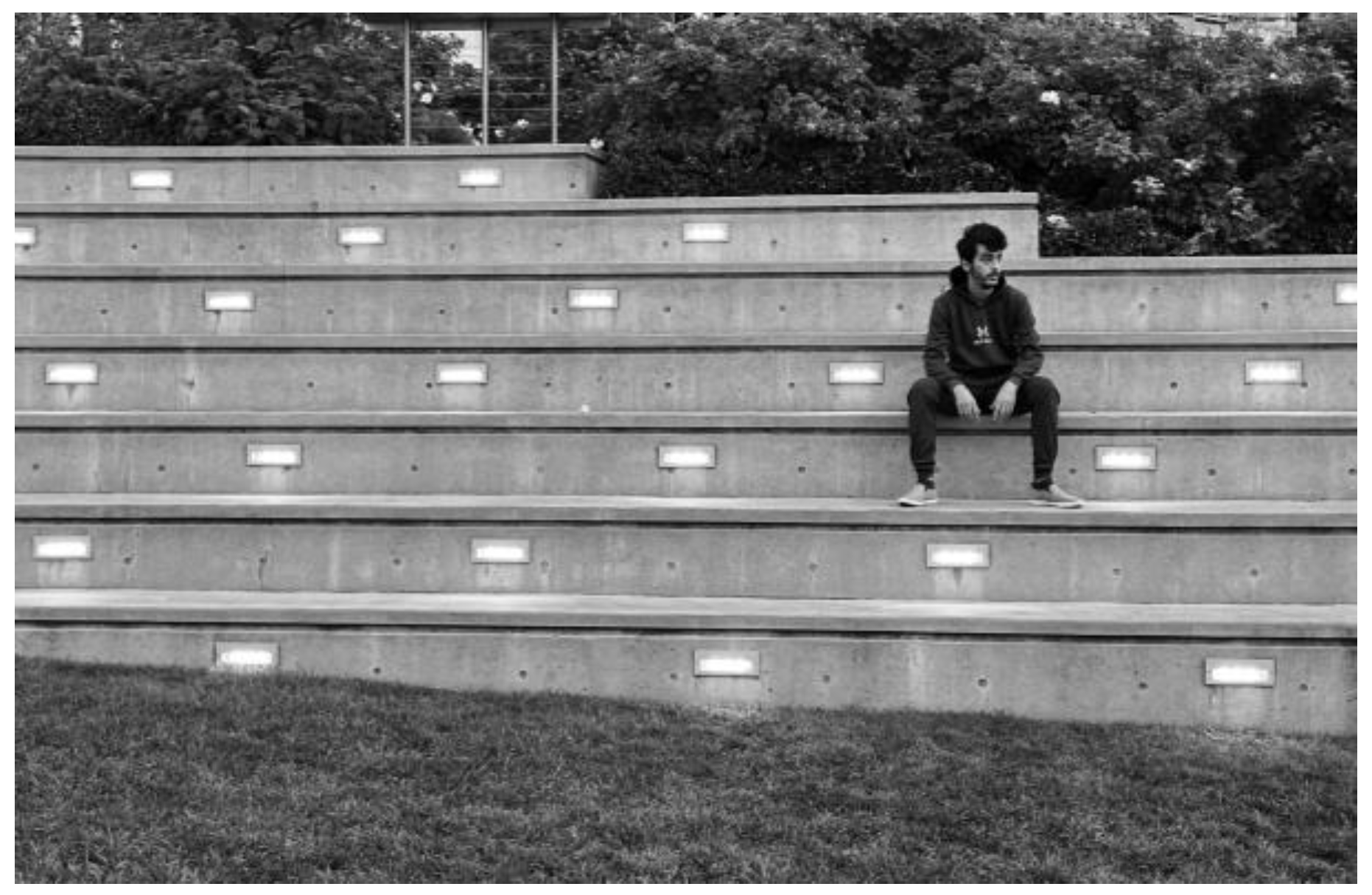

3.3. Isolation and Loneliness: “I Feel Like I’m Alone Here…”

Not all participants arrived with extended family networks or social supports. Single and younger men and those who arrived without extended family felt more alone. A younger man explains:

“Yeah … so, this photo represents what I feel now … my biggest problem here in Canada which is I feel lonely. When I was in Egypt, I had lots of friends, many more than I can count everyone … OK, so coming here and leaving all that behind, it kinda make me feel something I haven't feel before, which is lonely. And it kinda make me afraid to talk to anyone new, because I don't know what the results will be and being alone is … not a nice thing you know. … I used to go to cafés, to go to beaches back in Egypt with my friends. I used to have fun … now I stop all of these things. I don't play video games; I don't go to bar … so the things that used to be fun to me are not fun anymore.” (N4)

It was difficult for the youngest participants to find friends and to connect with peers in Canada. These young men also found it challenging to connect with friends living in host countries due the time differences. For participants—particularly those who arrived without a social support system—socialization and community were important. Culturally, some men wanted to socialize after work, as this was part of their life back in Syria:

“The other day, I was just saddest moment in my life. I guess I was, uh, I finished work, and it was around 11:30[pm] in cold, dark, lonely … There was no one on the street. 11:30 at night. [...] Yeah. Which is a festival in …in Syria. Just, like, everybody around 11:00 … do you have a coffee at 11:00? You have a falafel center or wherever you want. Everybody's there, but here, it's just, like, dark and empty.” (M5)

For other participants, too, isolation and loneliness were common experiences at their places of employment. In this context, men felt increased isolation and loneliness when they lacked opportunities for conversation and socialization with other employees. One participant explained that it was challenging to engage English-speaking colleagues in conversations.:

“I gave them my resume and invited me because my resume indicates experience in electricity, and work in salt, molding. I have trades experience. The problem was not experienced, only language. My language capacity is not improving, because I cannot socialize with others except Arabs. Anywhere I go, I find Arabs in my face [expression] at work, which does not allow me to practice.” (M1)

While at work sites, many participants did not feel they had opportunities to practice their English-speaking skills and wanted more opportunities to socialize. Similarly, one participant explained that he felt he isolated and alone while going to work and while working in a food-related industry:

“Waiting the bus to move to ... the job because I couldn't find anything at that time. … it started 5:00am … I didn't have a car. … So, I had to leave early and get two buses, so that I can arrive [on] time. … Like, even when the bus moves it, it only has three or four people on it. So, you feel like you're there yourself, only. So, it just might reflect my feeling at that time, like, people sleeping and had to wake up early just to get there to work somewhere. Mm hmm. It was the only job I could find at that time …. They didn't ask me for any English or anything. … They don't care about the language; they just want some people to stand behind a machine and do some stuff.” (N5)

Most men who were working long hours in service-industry jobs did not have opportunities to connect with other employees. Some men working in platform-based work were required to spend most of their day driving, which in some cases, also shaped their feelings of isolation and loneliness:

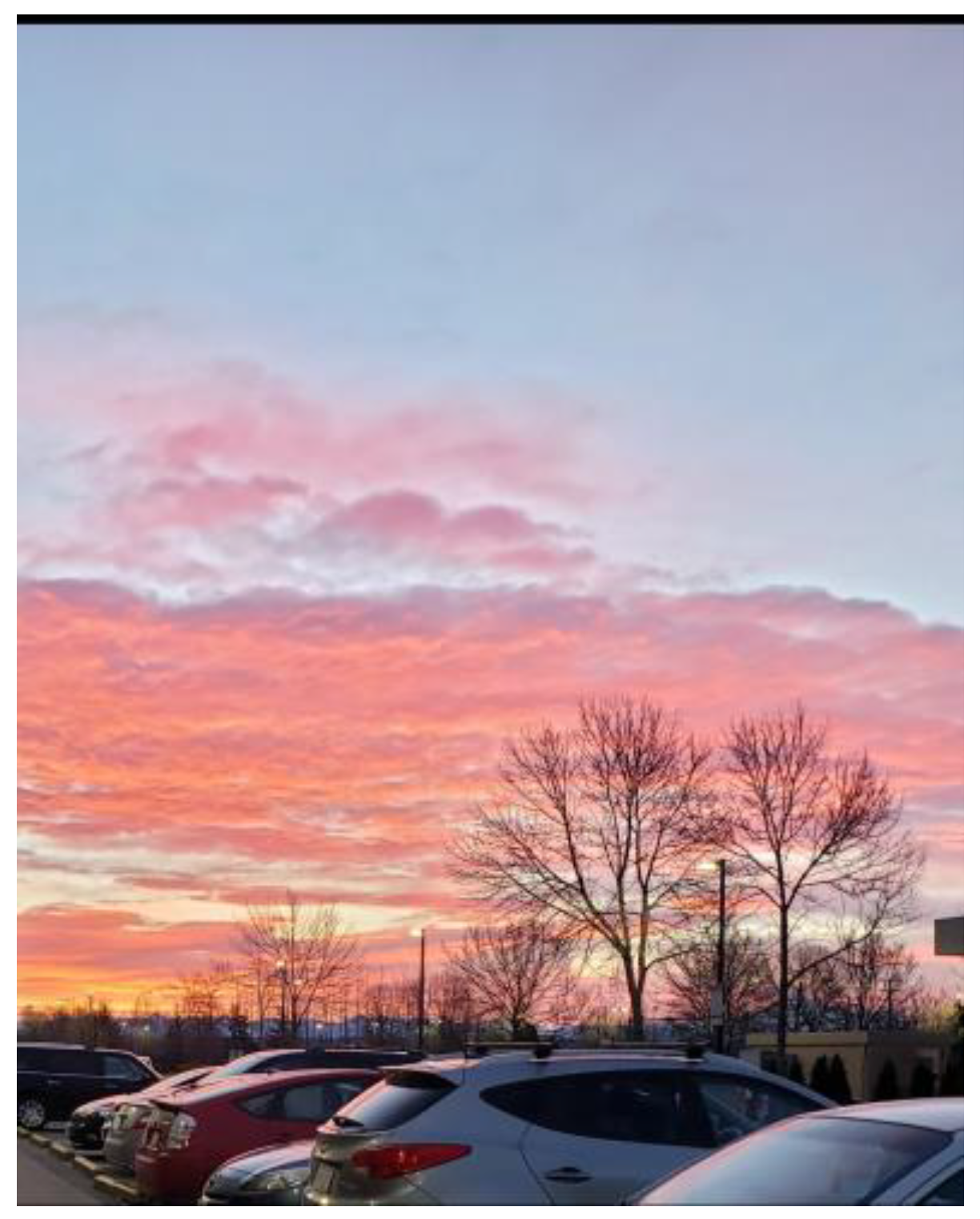

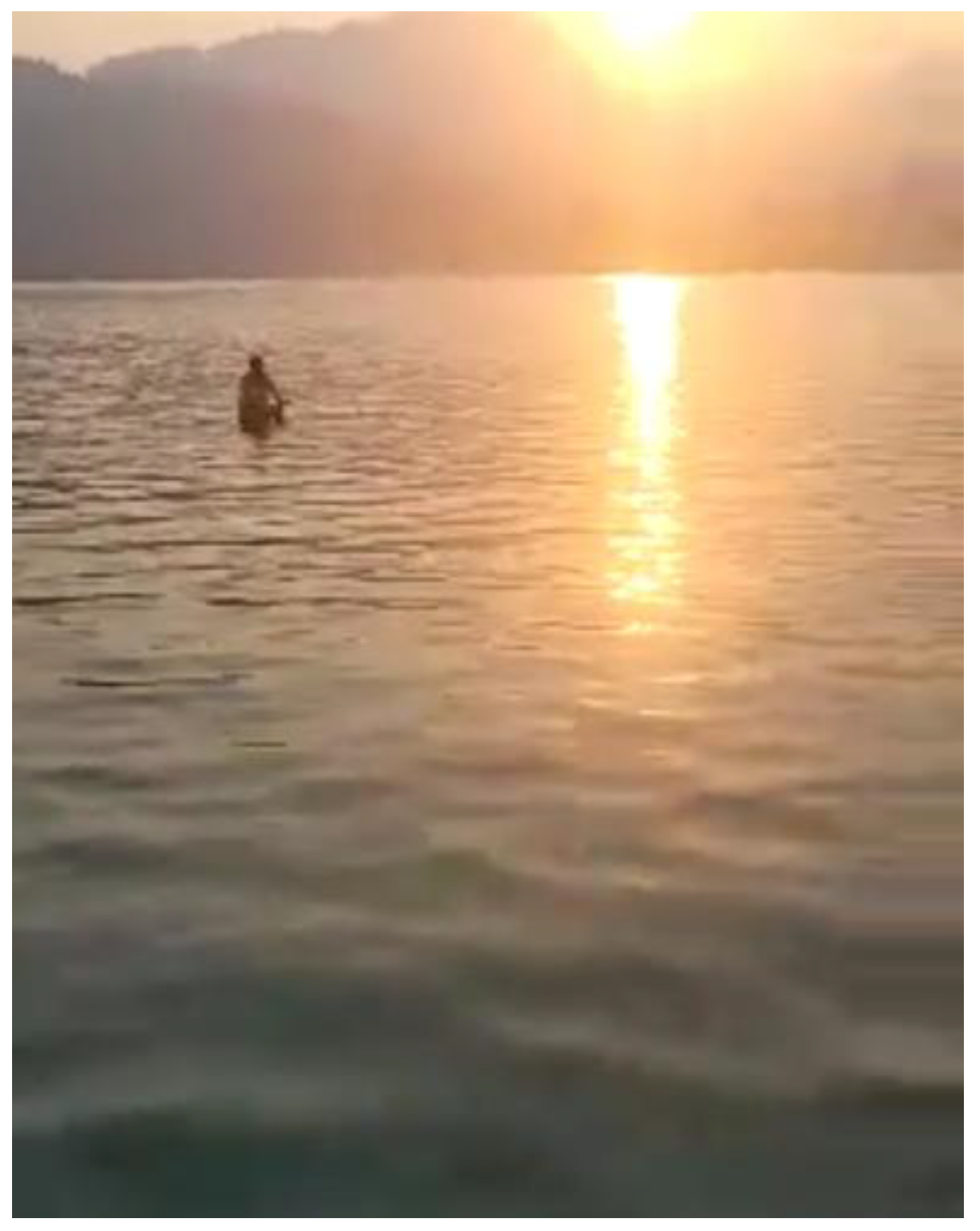

“When I took this picture, I was at work. I took the picture while I am inside the [name] van, as you can see from the car’s window. I was at work delivering packages. When I arrived at one destination, I found a … sunset. I love this kind of view; it’s very beautiful. You see how the sun reflects, and the sunshine has a colorful view. That makes me calm and peaceful. I took this picture and sent it to the research team. Also, … I take this picture, because sometimes, like this work at 9:00 o'clock and in this photo, it looks like it's going to be nighttime soon. Yeah, nighttime … sometimes I work to 9:30 or 9 o'clock [pm] because we start, we start as a 11:00 o'clock [am] we start.” (N3)

For all the men in this study, their work was deeply tied to their sense of responsibility to provide for their families and to contribute meaningfully to Canadian society.

3.4. Belonging and Identity: “We Have Friends Gathering with our Kids as the Kids Play with Others”

For most of the men in this study, their source of employment in Canada was not tied to their professional or occupational identity pre-migration. However, being responsible for their family’s wellbeing—having a sense of hope and family—was interconnected with the participants’ identities. For example, one participant described how his self-image was tied to his professional identity:

“Self-image, money isn’t it. It's who I am. I am an artist. And even if I started doing something else, I can't eradicate that part of my identity. Yes, I am an artist. Yeah, I'm going to always be creative. Yeah. It doesn't matter if I'm doing it for a living or not. It has to be around.” (M5)

Identity was tied to men’s self-image and who they were pre-migration. Most of the men in this study had received a postsecondary degree in a chosen profession, such as accounting, civil engineering, architecture, dentistry, or the arts. However, most men also experienced de-credentialing, as they were told by employers that they did not have Canadian experience or Canadian-recognized certificates for their profession. This de-credentialing negatively affected these men’s identity and belonging—particularly among participants who had been working in professional occupations for many years before coming to Canada.

One participant talked about how the below photograph (

Figure 12) reminded him of being a young man in Syria and needing to work hard to be able to find a job:

“So whenever [I see] this picture [I am] reminded [of myself] … being very tired, weak, lack of sleep and, you know, you don’t have even time to eat … hands [are] very dirty, clothes … dirty. He doesn’t even have time to clean himself; he just wants to eat and have this. [I] can’t find a job, because I need to upgrade. I don’t have time, because I have other expenses … its very expensive … in Canada. I don’t know why you need to start from zero. You have to go to school to get a grade certificate—you need Canadian certificate.” (N2)

Most of the participants expressed that they had already been working for a long time before coming to Canada, and so not having their credentials recognized negatively affected their identity and sense of belonging.

Similarly, another participant explained how his work in Canada was not tied to his professional identity: “This [picture is of] a sunrise. … I am leaving from [work name,] and it give me a moment of hope. … I do not consider it really a profession: it is more about just getting paid.” (N1)

For many of these men, belonging and identity were also tied to social networks, community, kinship, and family. As one participant explained:

“This picture, I took in the month of Ramadan. We break our breakfast with my friends and family. … The meeting was great and spent a nice day. I like the view that encourages me to take this picture. While we have friends gathering with our kids as the kids play with others. We spent a nice time. This kind of gathering helps me with releasing work and life stress, especially during the holy month of Ramadan.” (N3)

Similarly, another participant explained how, for him, being a new father in Canada created a sense of belonging and identity:

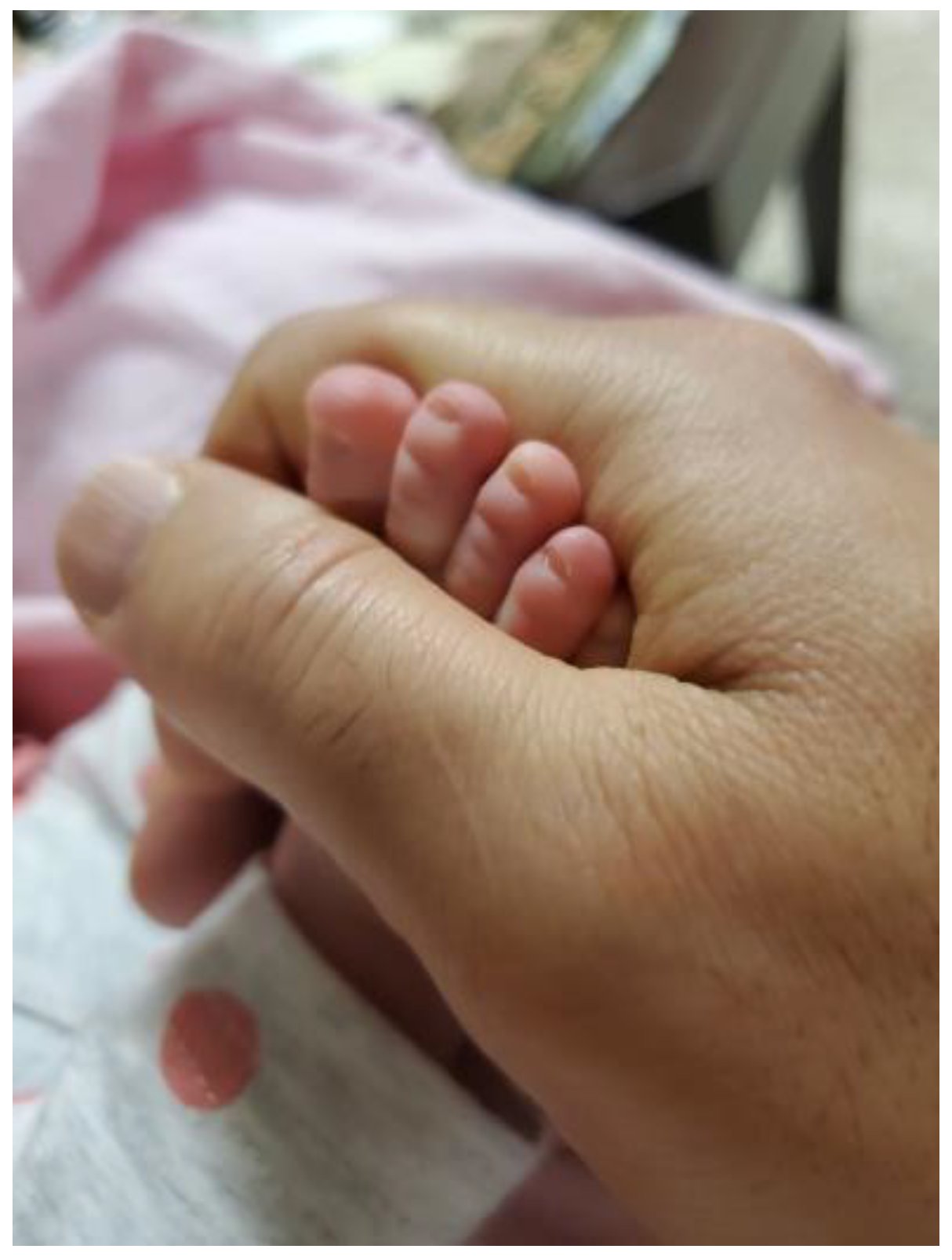

“When I come back from work, when it's hard day … outside and … I put it [son’s picture] … right off the door when I open it … It really gives me give me power … [when] I got married, something became different my life. … I became a father … I always thought, ‘I don't have family here’ … I always remember my family back home, and sometimes we sit together or have dinner or something. I have a family [now].” (N5)

Not all participants arrived in Canada with their families. For single men and men in relationships, having their own family in Canada created a sense of purpose. The new father quoted above explained how he was offered more pay for longer hours, but his need to work did not outweigh his need to be with his family:

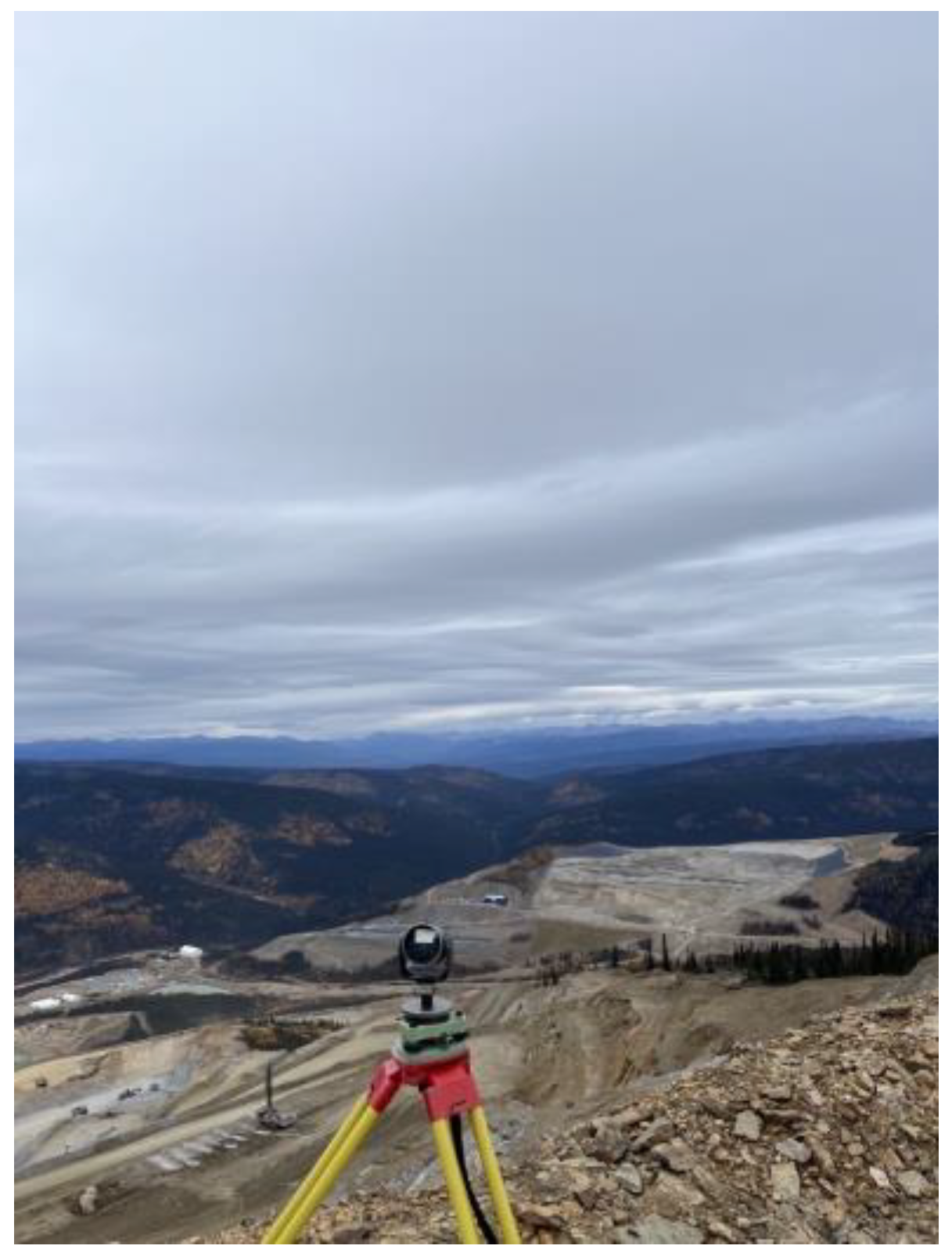

“I had to travel to [place] to do some job this job, … when I went there, they asked me to stay. They have a camp there. So, they asked me if I felt okay to stay there for a month …But I refused. It was cold you know, … I told them, ‘I have a family. I have a boy; I have to pick him up, the kids from daycare every day.’ … I can't just go there and leave them alone here. And they are new in this country … It's not only money, like, they pay more. …So, some people choose to go there, but in my situation, I just say ‘no.’ … Probably some people who need more than me who were forced to accept it …They're even like … put you in a camp. They pay for everything you. They give you a vehicle … But still, like, I don't know—you're alone. You know, you're alone and in that, whether you're spending the time, they're losing your life. It's not only money, …. It's a hard heart. It's tough.” (N5)

Many men talked about their responsibilities for childcare, like picking children up from school. Men who had families of their own were engaged in caring responsibilities within the home, and this was viewed as part of Syrian men’s roles as fathers. Another participant explained how having a family gave him new hope: “This is the picture of my daughter in Canada … For us, this was, God willing—this was a glimpse of hope and light” (M1).

Belonging and identity, for these men, was also connected to culture and place. As one man explained:

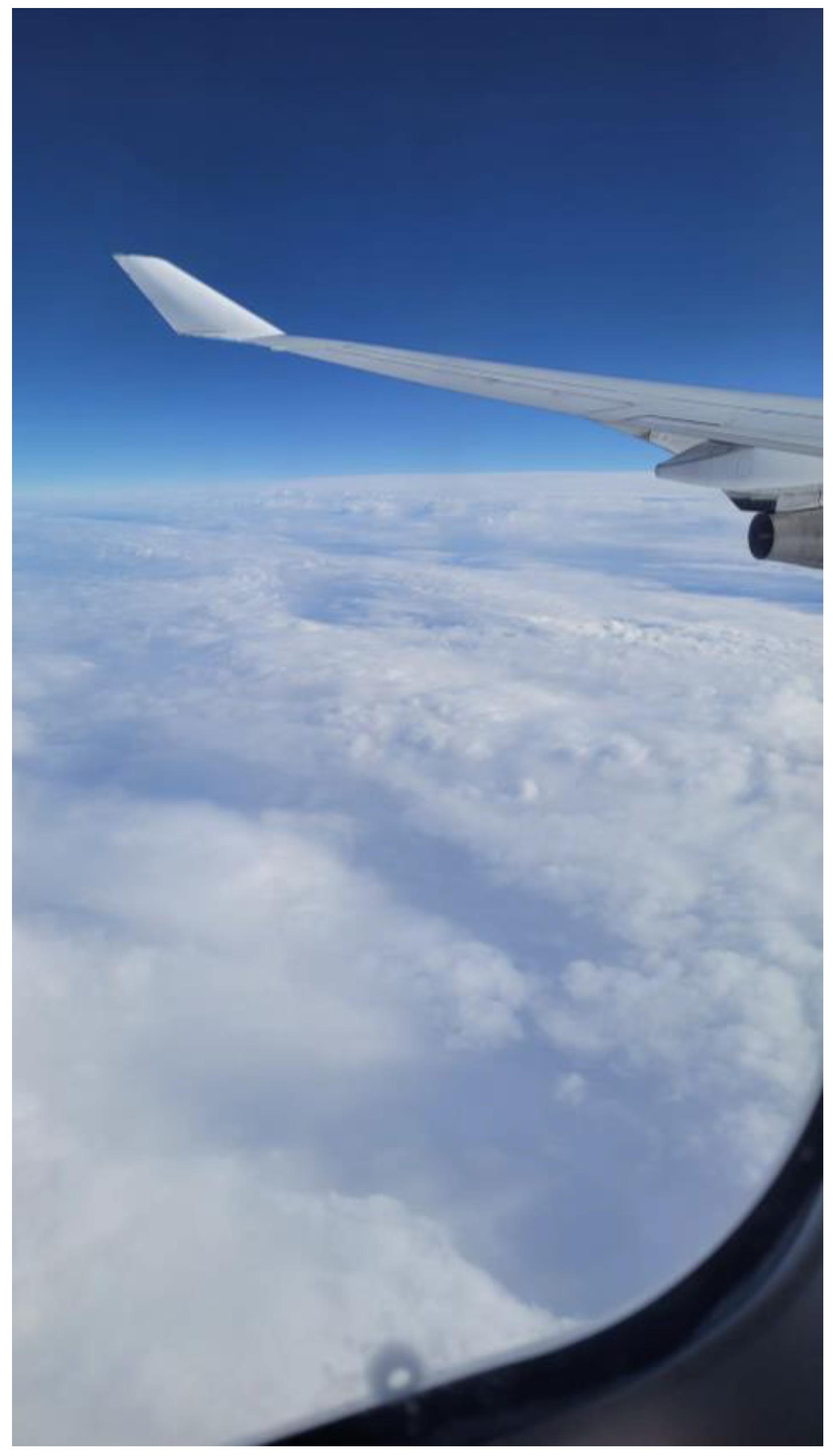

“This picture, I took after I become a Canadian citizen and get my passport and felt I am ready to travel outboard. When I saw an airplane above me in the sky, I asked myself, ‘when I will fly by airplane?’ … So, one day, hopefully, I'm going to take this airplane and go back Syria and meet my family—father, mother, siblings.” (N3)

Obtaining citizenship provided to N3 the ability to travel to work or see families left behind. However, for other participants, memories of home were triggering and signified negative emotions and mental distress:

“So [we] went to the [NAME] Lake and this is the picture … this kind of boat, remind [me of] friends which they drowned on the Mediterranean Sea, …so most of [my] best of friends, they try to leave Turkey, going to seeking for resettlement. But, unfortunately, they pass away. So [I don’t] like to go anymore.” (N2)

Loss of friends and family trying to find refuge was also part of these men’s belonging and identity. Participants found ways to manage their stress and psychological wellbeing by spending time with family and friends through cultural traditions and place—including spending time outside.

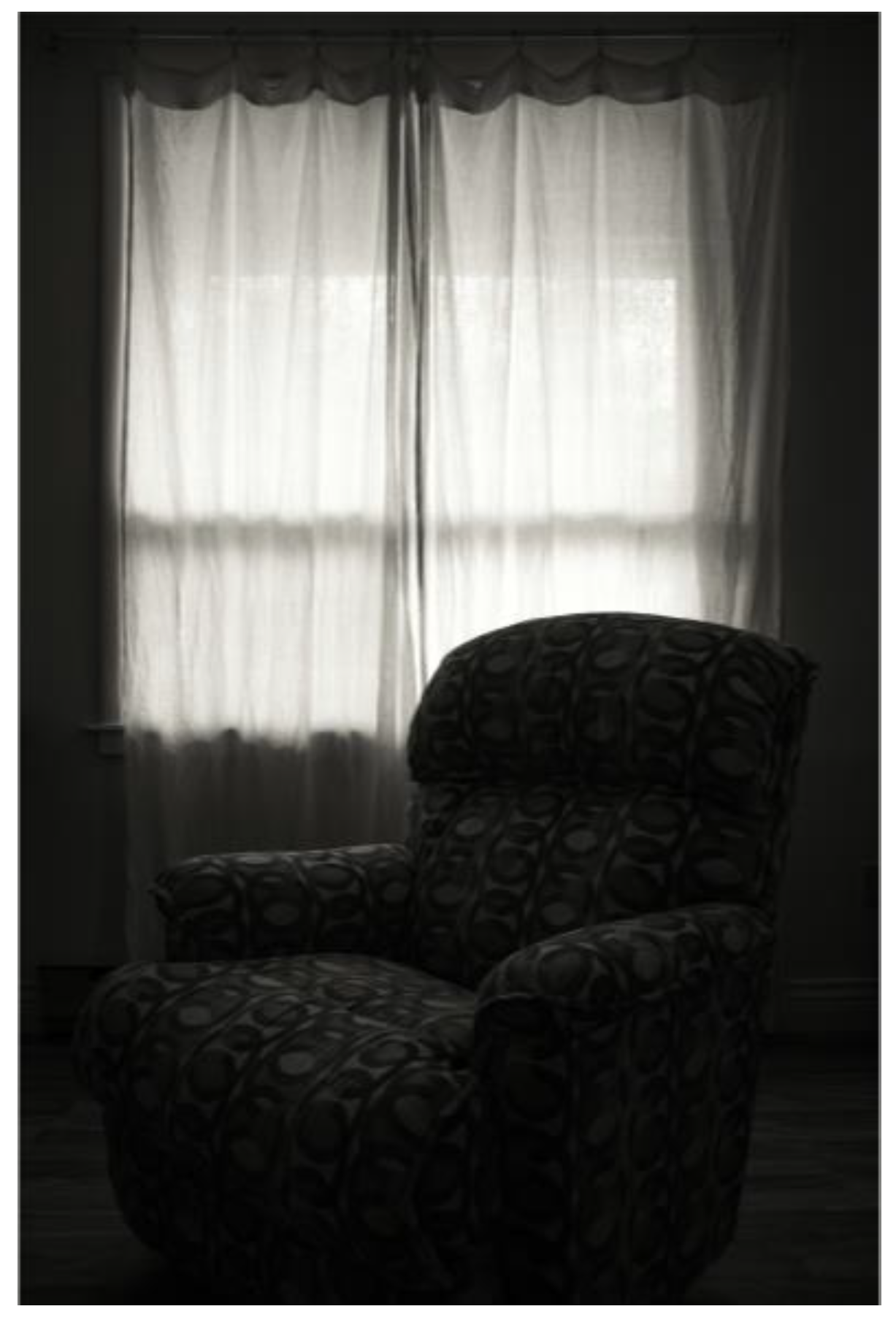

3.5. Gender based Stress: “Always Under Pressure”

Overall, these men experienced gendered stressors related to the pressure of needing to be able to find work to provide for their families, including providing remittances for families in Syria and other countries of displacement. Most of the men were stressed due to their inability to work in their chosen profession and need to earn a sufficiently high income to support their families. In the context of forced migration, some men discussed leaving Syria to neighboring countries to pursue higher education, to avoid mandated military services; others described serving in the military. One of the older participants explained his situation:

“Actually, every year I work for three or four months in winter. There are no jobs for engineers, … especially for Syrian, because the government in Lebanon, …they didn't allow engineers, Syrian engineers, doctors, lawyers, all of them to be in the part of their associations. They didn't allow us … Yet we work with very cheap salaries [like the black market].” (M3)

The lack of recognition of participants’ skills and credentials pre-resettlement extended into Canadian resettlement contexts and added to these men’s stress. Another participant described feeling pressure and increasingly stressed:

“In Canada, you feel stress and always under pressure … this cup of coffee, … It sort of reminds me … in Turkey, even though we lived under pressure, but we had very beautiful time and vacations. … We didn't feel this. It’s kind of, uh, stressful … Yeah … financial stability gives everything a better taste.” (N6)

Another single man described the pressure and stress he felt while working multiple jobs:

“I already had, like, three jobs, so I wasn't sleeping enough. I was overworked and I was stoned all the time, and I was going to the gym and trying to keep pushing myself forward to the point where I almost broke down. Right? That's why I got my new job and then quit on my three other jobs. You know, no more. But that was too much; like, I was physically impacted by the depression. I'm saddened, depressed. I barely walked. I couldn't speak.” (M5)

Working multiple jobs negatively impacted the participants’ mental health. Working long hours also meant that some men were not able to carry out their child-minding responsibilities or care for a spouse living with a disability. One participant explained:

“And, and she can’t drive. She speaks good English, she has good certificate, but she can’t work. This my responsibility—I am responsible for home. … But I—it’s very hard. I tell you, it’s very hard.” (N2)

For this participant, to provide care for his spouse, he needed to have flexible working hours.

Being responsible and caring for family members was important for some of the men. This importance was also expressed by a participant who discussed his family in Canada as well as family left behind:

“The first thing of my priority, I want to keep my position … to support my family. … This photo expresses that displacement of my people with one difference between the situations: … that these birds fly in the blue sky … But what about the rest of my family and friends? One of the most difficult difficulties here in Canada is that one of us [must] take care of himself, and his family here, and their families that are still suffering. … They choose to go; they planned. But when we fly, when we go out our country, no one of us have this plan. Everything is surprised us.” (M3)

Another man explained how he tries to manage his stress:

“I tried to work and contribute and interact with society. I faced a lot of challenges. It is okay. End of the day, I tried focusing on my children, and invest in them. How do I say—when a person reaches their maximum ability to cope with stressors! This is a coping strategy. Canada allows me to go out and change my environment to cope. If I stay at home and with the same social circle, I will fall in depression. It is a must to go on picnic and enjoy the outdoors every now and then. Canada enjoys incredible nature.” (N1)

The men in this study discussed their perspectives and experiences of work in the context of their resettlement in Canada. Their experiences of employment and under-employment intersected with their language ability and their cultural and gender norms, notably the need to provide for their families. Overall, these experiences shaped their identities, feelings of belonging, and psychological wellbeing. The men described gender-based stress that was related to gaining meaningful employment, navigating language barriers, and having a sense of belonging and identity in the context of their resettlement in Canada.

4. Discussion

This study provides an intersectional, gender-based analysis of the mental health impacts of forced migration and the employment experiences of men with Syrian refugee backgrounds in the Canadian context. Mental health stigma and normative masculinity can be barriers to talking with men about their mental health [31,35,38]. Moreover, mental health constructs are not universal; for men with Arabic backgrounds, having poor mental health is highly stigmatized and may be thought of as a mental disability rather than the result of social determinants of health [28].

Photo elicitation provided a way for these men to talk about the factors that shape their mental health and wellbeing in the context of their resettlement in Canada. Photovoice group discussions offered a way to promote these men’s collective voice and to validate our findings. Five intersecting themes encompass these participants’ perspectives and experiences about the factors shaping their mental health in the context of their employment and resettlement in Canada: 1) language and literacy barriers, 2) time and stage of life, 3) isolation and loneliness, 4) belonging and identity, and 5) gendered stress. We used intersectionality as an analytical lens to unpack these men’s stories and their social identity traits, which then revealed the factors that lead to their gender-based stress. The findings are intersecting themes and are not mutually exclusive; rather, the themes inform each other. For example, both employment and under-employment—that is, working in jobs that were not congruent with men’s previous professional or educational experiences—negatively affected their sense of identity and psychological wellbeing.

The participants perceived a lack proficiency in English to be a major barrier to employment, which intersected with their stage of life and perception of time. Many middle-aged participants found it challenging to attend English language classes or other forms of educational programming that could advance their careers. Our finding supports previous research that suggests that refugees are disadvantaged in the labor market due to gaps in their language proficiency [55,56,57,58]. In addition, refugee men are less likely than women to complete Language Instruction for Newcomers (LINC) classes, a finding which may be related to the gendered pressure to be a male provider and earn an income to support their families [58]. The men in this research reported an average of level 6 on the Canadian Language Benchmark (CLB). According to CLB, this means that most of the men in this study had an intermediate language ability measured as an ability to function independently in daily social, educational, and work-related life [46].

However, having language skills means more than being able to read, write, and listen. Nonnative English speakers may have skills at different benchmarks or stages; for example, while they might have a listening benchmark level of 6, they could simultaneously have a speaking benchmark level of 2 or lower. These differing skill levels may reflect the participants’ needs to develop social relationships and connections to support their understanding of English language in everyday life. Most of the men in this research are middle aged (averaging 39 years old), and their experience of displacement significantly disrupted their ability to re-learn new literacy skills required for a knowledge-based, digital economy—for example, typing in English or navigating online job sites and other forms of digital technologies. Canada’s is a knowledge-based economy that centers on skilled labor and education—an economy in which newcomers, including refugees, are underrepresented [22]. Research shows that the strongest predictors of labor market success in Canada are proficiency in English or French and educational attainment [57]. Moreover, privately sponsored refugees tend to have more success finding meaningful employment and work that matches their chosen profession when compared to refugees who come to Canada through BVOR and GAR [60,61]. In our study, six out of eleven men—almost 55%—came to Canada with high levels of education, and two out of three who had arrived through a PS stream were able to work in their chosen professions. All men in this study perceived a lack of credential recognition, meaning that their credentials or skills earned prior to arriving in Canada were not recognized when they sought employment in their chosen professions. As reported in their interviews, the lack of credential recognition put men under tremendous stress, leading them to question their self-worth in the immigration context.

Although most of the men were engaged in resettlement assistance programs that provided government support for up to one year, most men were employed in entry-level jobs or platform-based work and used their social capital—that is, their own social networks—to gain employment. In this study, 73% of the men were employed in food delivery, the service industries, or platform, ‘gig economy’ work, for which they did not require high levels of English language proficiency. These men’s sense of belonging and identity are deeply tied to their chosen professions and career aspirations. The opportunity to earn an income through online platforms provided a solution to language barriers they experienced and potentially increased their autonomy and agency, putting them at an economic advantage. However, it also disadvantaged them, as they needed to work long hours, take time away from their families, and neglect their gendered responsibilities and future career aspirations. As Western economies move from labor-based economies toward knowledge- and service-based economies, these transitions may add to refugee men’s vulnerabilities, emotional isolation, and distress [33,34].

Emergent research on migrant workers and the gig economy has shown that gig platforms across the globe are increasingly dependent upon the labor of migrants. These platforms extract maximum value from their workers, with little-to-no investment in their physical, mental, or economic security [24,62].. Structural conditions such as perceived discrimination, long hours, and isolating work environments—for example, delivery driving—added to the men’s sense of isolation and limited their opportunities to advance in English. Our findings thus align with a recent study that explored the subjective experiences of immigrants in the Canadian platform-based labor market. This recent study showed that 72% of immigrants are middle-aged men who engaged in ‘gig’ or platform-work, because the majority were not recognized as having Canadian experience [22]. Like findings from this research, the dearth of human capital recognition within platform work meant that most immigrant workers gave up on their career aspirations [22]. Researchers argue that platform work exists within hidden power relations that are highly racialized and exploitative and that also function to contain and manage migrants’ sense of belonging [22].

In our study, participants ground their sense of identity and belonging in their work and professional aspirations. Most of the men felt, as M1 expressed, “forced to work any job” to earn a living and meet the demands of providing for their families. Findings from our research also highlight a trend of economic downgrading and marginalization of Syrian refugee men in both pre- and post-resettlement contexts. The men perceived belonging through their social relations within and outside of the labor market. The implication of these factors is that the men may experience increased psychological and emotional costs beyond socioeconomic ones. Importantly, belongingness is connected to social and structural conditions [63]. In other words, social conditions can enable and interact with one’s individual capacity for human interaction and connection.

Belonging is an important social determinant for refugee mental health; however, it is under-theorized for refugee men. A recent study exploring the factors and processes that facilitated or hindered the experiences of belonging in Canada among 15 diverse refugees found that, amongst other factors, social connection, cultural identity, and English language proficiency were important for promoting mental health and wellbeing in the context of resettlement [64]. However, unwelcoming environments caused significant psychological distress and feelings of rejection, particularly when these environments were fostered by people in positions of power. These findings resonate with the experiences of the men in this research, who found opportunities for cultural connection, social relations, inclusion, and sense of belonging in spending time with family and friends through cultural traditions and place.

For the men in this research, their identity and sense of belonging were also strongly connected to being the main provider of their family’s material and financial needs. Researchers have argued that patriarchal norms and customs are pervasive in Syrian society, where men are the main breadwinners [16]. However, social determinants of mental health, such as employment, are related to masculine ideals where men derive self-identity, self-esteem, and self-worth from having status, income, and resources to support themselves and their families [33]. A mixed-methods study investigated the effects of post-migration economic stressors on the mental health of recently resettled diverse refugees in the United States; this earlier research showed more than 41% of 290 respondents identified economic stressors as the primary causes of their emotional distress [65].

In the immigration context, some men in our study took on intensive caring roles for their children that go against Arab masculine ideals and patriarchal norms. Investing in their children’s future and having family connections and support were sources of prosperity and hope for the Syrian refugee men in this study. A recent study of the impact of forced migration and resettlement on Syrian refugee fathers in Canada found that Syrian fathers experienced changes to their gender roles—changes that were not only associated with cultural and religious beliefs, but also intertwined with masculinity and broad structural conditions of being able to fulfill their role as breadwinner [31].

In our research, newcomer Syrian men in Canada with families of their own—and those who became new fathers in Canada—experienced their families as a source of strength and social support. Paradoxically, men with families also experienced gender-based distress in not being able to financially support themselves or their families. Managing multiple life transitions including fatherhood could lead to increased emotional distress for refugee men. However, the participant men in this study come from diverse life paths and different age groups and religions. In this study, the young participants experienced isolation from friends and family left behind, in addition to stress related to needing to balance going to work and perusing their education while in Canada. These differences—related to stage of life and time pressures—are supported by an earlier study that explored occupational transitions with Syrian refugee youth in Canada; this study found that refugee youth often face cultural and linguistic barriers to navigating pathways such as pursuing high education and searching for a job or housing while still financially supporting their families [64].

All the men in this research were new in their resettlement and arrived in Canada between 2016 and 2022. They all had obtained either permanent residence or Canadian citizenship status. The participants’ immigration status shaped their identity and sense of belonging because it allowed them to travel, in some cases back to a previous host country for work and to visit their extended families. Evidence suggests that belonging and social connectedness through formal and informal networks can act as protective mechanisms for refugees’ mental health, particularly for those that have experienced disruption of social connections, including social life and contact with lifelong friends and relatives [66,67].

In this study, participants’ career aspirations and context of employment also created a source of gender-based stress. Participants expressed that they always feel under pressure in resettlement contexts, which suggests that they experience vulnerabilities related to traditional gender roles and masculinity. This finding is supported by earlier research that examined the gender roles among Syrian refugees in resettlement contexts in which participants experienced a lack of opportunities for socialization and loss of both connection and empowerment while working in jobs that did not correspond to their class or status back in Syria [16]. Findings from this earlier research suggests that newcomer Syrian women may have more opportunities than men to create community, access social and legal support, and develop their capacity for building entrepreneurial opportunities in different geographies of resettlement [4,5]. In contrast, newcomer Syrian men continue to experience barriers to prosperity and economic integration related to narrow patriarchal constructions of masculinity [16]. Importantly, such narrow constructions of masculinity reinforce women as vulnerable, and thereby fail to consider the social and structural vulnerability of refugee men and the board social, political, and economic factors that shape their mental health in context of displacement.

Other explorations of post-migration contextual factors and psychosocial stressors on the health and wellbeing of Syrian refugees in Canada have found that women and older Syrian refugees reported to have poorer mental health than refugee men and younger refugees [6]. Syrian refugee women were also found to have less ability to participate in social service programs due to their family’s childcare needs and to other gendered responsibilities [6]. The same study found predictors for mental health also included having postsecondary education, sufficient finances, proficiency in English, and control over one’s circumstances; being employed and married; and reporting satisfaction with one’s housing and low stress levels [6]. Similarly, in this earlier study, men who had postsecondary education felt disrespected and dissatisfied with entry-level jobs. However, findings from our research somewhat contradicts this earlier work. Our findings suggest that, for men, gender-based stress was underscored by the need to financially support their families and by the need to care for family members. Differences in reporting of mental health maybe related to the fact that some men are unlikely to report negative emotional or psychological experiences because of their conception of masculinity. Our findings underscore the importance of an intersectional analysis, which understands gender roles as not fixed and influenced by multiple intersecting factors. Masculinity and broad cultural discourses affect the ways in which vulnerability of men and emotional distress are understood and reported [33].

Some Syrian men in our research also described setting aside their own career aspirations to focus on supporting their children; other men stated that they valued time with their family over working as many hours as possible. Still other participants talked about needing to support their wives by driving them to medical appointments because they had physical disabilities. These findings contradict media and political representations of Syrian men and broad discourses that reinforce traditional notions of masculinity. Other research with refugee men who experienced forced migration from Sudan has shown that gender roles, parenting practices, and social relations are embedded within broad socio-political processes that reinforce essentialist and monolithic notions of masculinity in contrast to Sudanese refugee men’s experiences, in which their identities are fluid and dynamic; in between, men “wal[k] the line” between cultural and institutional gendered expectations [67]. Similarly, research on caring masculinity suggests that working-class men—including men marginalised due to class, race, ethnicity, or nationality status—embrace values of care through their relationships and not through gaining power [68]. Caring masculinity and exploration of gender relations provides an alternative model for re-imagining and understanding how Syrian refugee men perform masculinity within their cultural role as the provider, as they re-negotiate their identities during resettlement. A lack of employment, combined with men’s status as the traditional breadwinner, to put additional stress on newcomer Syrian families during acculturation [32]. Findings from our study suggests that Syrian refugee men in Canada experience gender-based stress across multiple social dimensions. Settlement services and counselling support need to consider broad social determinants of refugee men’s health to provide gender-responsive care [1,33].

4.1. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study provided an in-depth analysis of Syrian Canadian men’s experiences, which addresses a gap in knowledge about how gender, forced migration, and employment shape refugee men’s mental health and psychological wellbeing during their resettlement in Canada. These men’s voices provide understanding about their collective subjectivities within wide power relations and social structures of resettlement and shed light on the social determinants of refugee men’s mental health. This study adds to broad discourses that seek to disrupt essentialist notions of masculinity and to promote an understanding of men’s vulnerabilities. Drawing from the study findings, an ethos of care can work to support refugee men’s mental health, suggesting a need for inclusive, caring, gender-responsive practices across resettlement and healthcare.

Due to the small sample size and qualitative approach, generalizations about the social determinants of Syrian refugee men’s mental health cannot be made. However, the study included iterative points of validation—community advisory board meetings, Photovoice workshops, and extensive photo elicitation interviews—which support informational power, or the degree to which the information was theoretically rich and able to answer the research questions [50,69]. Other limitations included the difficulty in discussing mental health, as most participants in the research culturally understood the construct of mental health through a deficit-based medical model, carrying negative connotations that may have led to low levels understanding about specific forms of emotional distress or idioms of distress [27]. However, anecdotally, the men in this study reported that they valued having space for talking about their perspectives and experiences on the factors that shaped their mental health in the form of peer groups. This anecdotal finding supports previous research that recommends men’s specific programing that is peer-led and that promotes men’s resilience and psychological wellbeing [29,33,36]. Future directions in research could evaluate the efficacy of peer-led support for men and the implementation of guidelines on supporting refugee men in the context of resettlement.

Migration policies and patterns have shifted toward a masculinized labor market gap, meaning that more men are now filling labor shortages globally [1]. Future research and practice must consider gendered vulnerabilities across genders, because migrants, including refugees and their families, experience far-reaching, gendered impacts to their mental health. Migrant men are particularly vulnerable and at risk of poor mental health because they have a high likelihood of being unemployed or under-employed [33,34,69]. Additional migration factors and stage of life transitions may further decrease refugee men’s resiliency and add to their experiences of gender-based stress [70]. Future research should include integrating settlement and health services to evaluate implementation strategies to support psychological interventions that may promote refugee men’s mental health.

5. Conclusions

In this study, Syrian men with displaced refugee backgrounds provided their voices on the intersecting social determinants that shaped their mental health in resettlement context. The factors that affected their mental health included language and literacy barriers, a lack of time, stage of life, feelings of belonging, identity, and gender-based stress. The importance of meaningful employment to men’s mental health is underscored by norms of masculinity. Refugee men are particularly vulnerable to negative mental health outcomes as they try to find meaningful employment in resettlement contexts. Raising awareness of refugee men’s vulnerabilities can support their mental health and wellbeing. These findings suggest that social service providers and society must adopt gender-responsive policies and programs that support men and redefine masculinity toward caring practices that address the root causes of gender inequalities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization N.C.; methodology, N.C.; software, N.C.; validation, N.I, and M.Z.; formal analysis, N.C , E.M and G.Y.; investigation, N.C. and N.I.; resources, N.I. and N.C.; data curation, N.C. and H.E.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C.; writing—review and editing, N.C., G.Y., H.E., C.H., M.Z; visualization, H.E.; supervision, N.C.; project administration, N.C. and H.E; funding acquisition, N.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insights Development Grant (grant number; 430-2021-00487).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the University of Victoria’s Human Research Ethics Board (ethical approval code #21-0538).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due and stored on NVivo 12 software data management program and has been de identified using codes. Participants photographs are available upon request as part of the data set.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded in part by the Social Sciences Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada. The study was also supported by a local non-profit immigrant settlement organization providing social services to supporting integration of refugees in Canada. We wish to acknowledge the contributions of our core research team members Nedal Izzden, Meer Mahmoud, Elias Moses, Eli Verdugo, Carla Hilario. Research partners Jagjit Gill, Rima Moubarak, Diana Delgado. We also wish to acknowledge Dr. Michaela Hynie for reading a previous version of the article. We would like to thank Letitia Henville for editing this article. Finally, this work could not have been possible without the 11 Syrian men willing to dedicate their time and resources to support this project during their resettlement journey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- International Organization for Migration. World Migration Report 2024, 2024.

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All, 2022.

- Fazel, M.; Wheeler, J.; Danesh, J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: A systematic review. Lancet 2005, 365, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, S.A.; Nuwayhid, I.; Habib, R.R. A conceptual framework on pre- and post-displacement stressors: The case of Syrian refugees. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1372334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalim, A.C. The impacts of contextual factors on psychosocial wellbeing of Syrian refugees: Findings from Turkey and the United States. J Soc Serv Res 2021, 47(1), 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, B.C.H.; Granemann, L.; Najibzadeh, A.; Al-Saadi, R.; Dali, M.; Alsmoudi, B. Examining post-migration social determinants as predictors of mental and physical health of recent Syrian refugees in Canada: Implications for counselling, practice, and research. CJCP 2020, 54(4), 778–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, F.H.D.L.; Waikamp, V.; Freitas, L.H.M.; Baeza, F.L.C. Mental health outcomes in Syrian refugees: A systematic review. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2022, 68(5), 933–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynie, M. The social determinants of refugee mental health in the post-migration context: A critical review. Can J Psychiatry 2018, 63(5), 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, L. Are Syrian Men Vulnerable Too? Gendering the Syria Refugee Response. Middle East Institute; 2016. https://www.mei.edu/publications/are-syrian-men-vulnerable-too-gendering-syriarefugee-response (accessed 2024-10-08).

- Kisilu, A.; Darras, L. Highlighting the gender disparities in mental health among Syrian refugees in Jordan. Intervention 2018, 16(2), 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CARE. Men and Boys in Displacement: Assistance and Protection Challenges for Unaccompanied Boys and Men in Refugee Contexts, 2017.

- CARE Jordan. Syrian Refugees in Urban Jordan: Baseline Assessment of Community-Identified Vulnerabilities among Syrian Refugees Living in Irbid, Madaba, Mufraq, and Zarqa, 2023.