Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Variable- Rocket Model

3. Exact Solution for the Free-Space Case

3.1. The Variational Method and the Hamiltonian

- L is the Lagrangian, or the instantaneous cost. For a minimum-time problem, the total cost is , so the instantaneous cost is simply .

- is the state vector, containing the variables that describe the system (e.g., position, velocity, mass).

- is the control vector, containing the variables we can change to steer the system (e.g., acceleration).

- is the vector of state dynamics, describing how the system evolves.

- is the costate vector, a set of auxiliary variables introduced by the PMP. Intuitively, each costate represents the sensitivity of the final cost to a small change in the state at time t. It is the "price" of that state variable.

3.2. Hamiltonian Construction for the Free-Space Case

- State vector:.

- Control variable:.

- State dynamics:

- Costate vector:.

3.3. Optimal Control and First Integrals

3.4. Deriving the Trajectory

3.5. Mass Evolution and Minimum Time

4. Transfers with a Finite Exhaust-Speed Ceiling

4.1. Setup and Scaled Trajectory

4.2. Derivation via Constraint Matching

- 1.

- Distance Closure

- 2.

- Propellant Closure

- 3.

- Exhaust Speed Ceiling

4.3. Final Solution and Limiting Cases

Detecting whether the ceiling is active

Limiting Cases

- Vanishing ceiling. When approaches the minimum useful value, forces . The two powered legs degenerate into instantaneous impulses separated by a long ballistic cruise, as intuition demands.

5. Full Planar Sun-Field Model

5.1. Pontryagin Maximum Principle (PMP)

- State vector:.

- Control vector:.

- Costate vector:.

- 1.

- The state and costates evolve according to Hamilton’s canonical equations: and .

- 2.

- The optimal control maximizes point-wise.

- 3.

- The Hamiltonian remains constant and equal to zero: .

5.2. Optimal Control Law

5.3. Costate Equations and First Integrals

- Rotational Symmetry

- Mass–Costate Relationship

- Constant Thrust Gain

6. Numerical Procedure

6.1. Objective Function

6.1.1. Global Search Objective

- : A fuel penalty that applies a large constant value if the final mass drops below the dry mass , effectively creating a hard constraint against using more fuel than available.

- : A radial position penalty, , which discourages solutions that fail to travel a minimum distance (e.g., 1.5 AU) from the Sun.

- : The velocity mismatch error at the final state. It measures the Euclidean distance between the final velocity vector and the required velocity for a circular orbit at the final radius , given by . The squared error is .

- : Positive weighting constants that balance the contribution of each term.

6.1.2. Local Refinement Objective

6.2. Two-Stage Optimization Strategy

6.2.1. Stage 1: Global Search

6.2.2. Stage 2: Continuation and Local Refinement

- 1.

- Set an intermediate target partway between the current known solution’s endpoint and the final desired endpoint.

- 2.

- 3.

- If the optimizer converges to a high-precision solution, the new solution is accepted. The intermediate target is then advanced closer to the final destination, and the process repeats.

- 4.

- If the optimizer fails to converge, it indicates the step to the new target was too large. The intermediate target is then moved back, typically halving the distance between the last successful endpoint and the current target, and the optimization is re-attempted.

- This adaptive stepping ensures that the local optimizer is always given a problem that is a small perturbation from a known good solution, guaranteeing robust convergence across the entire solution space until the final target is reached.

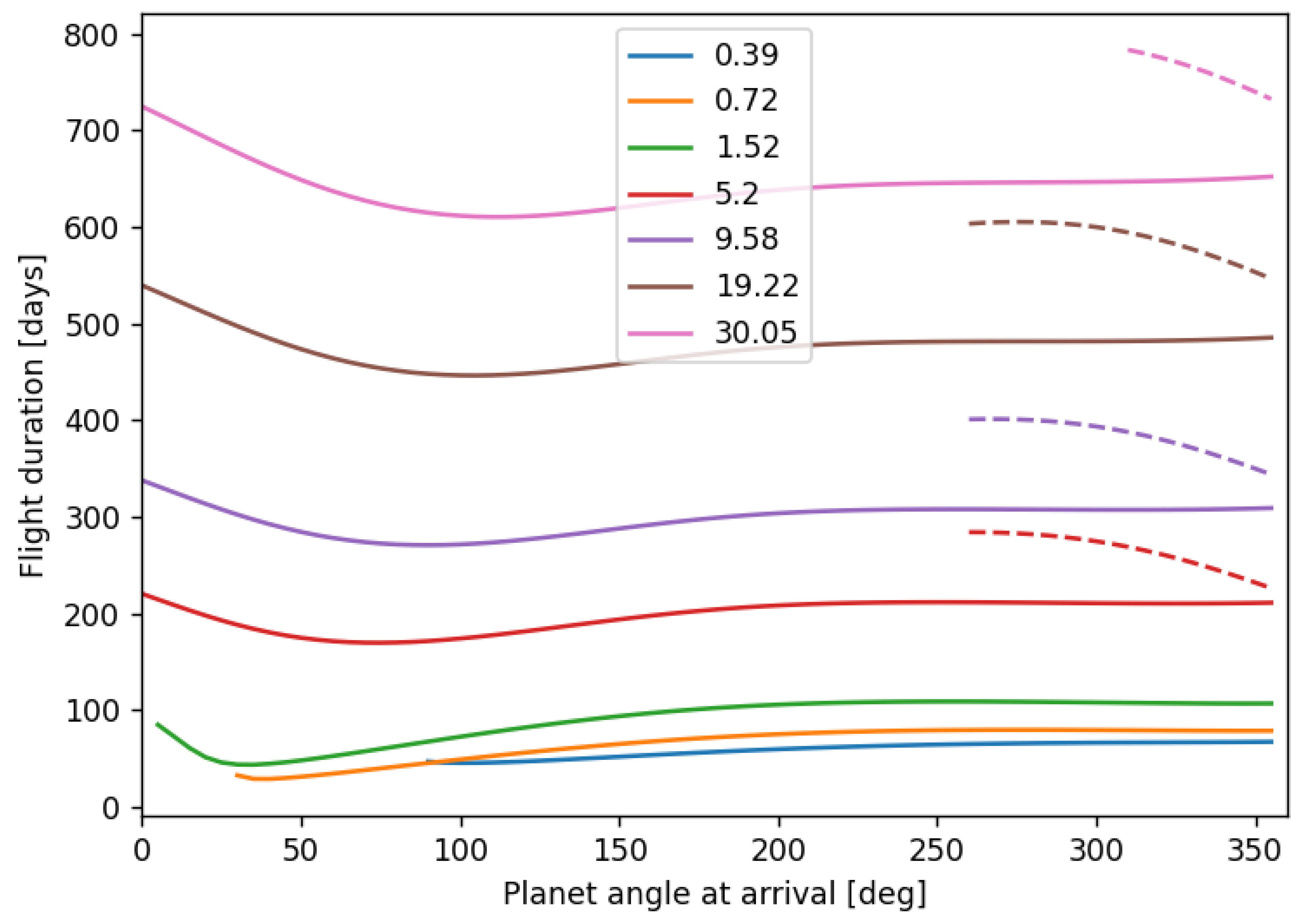

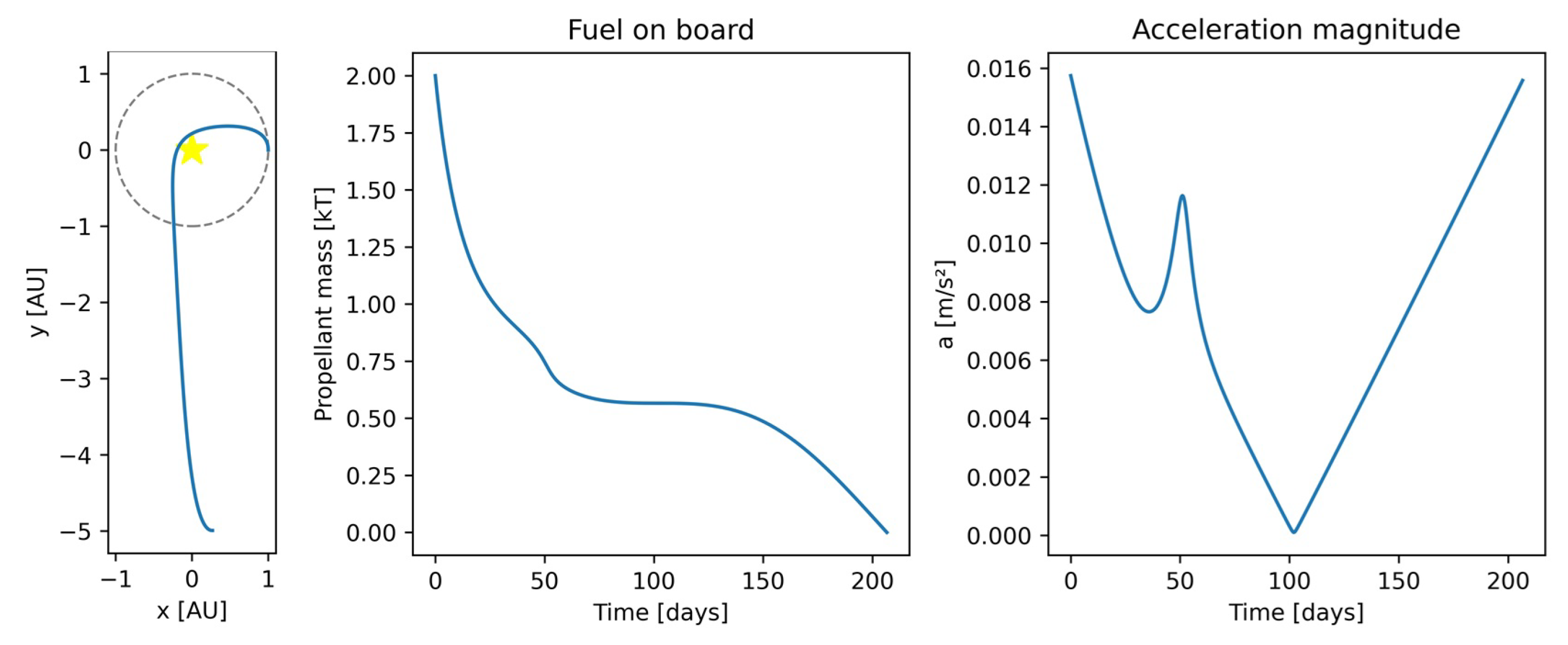

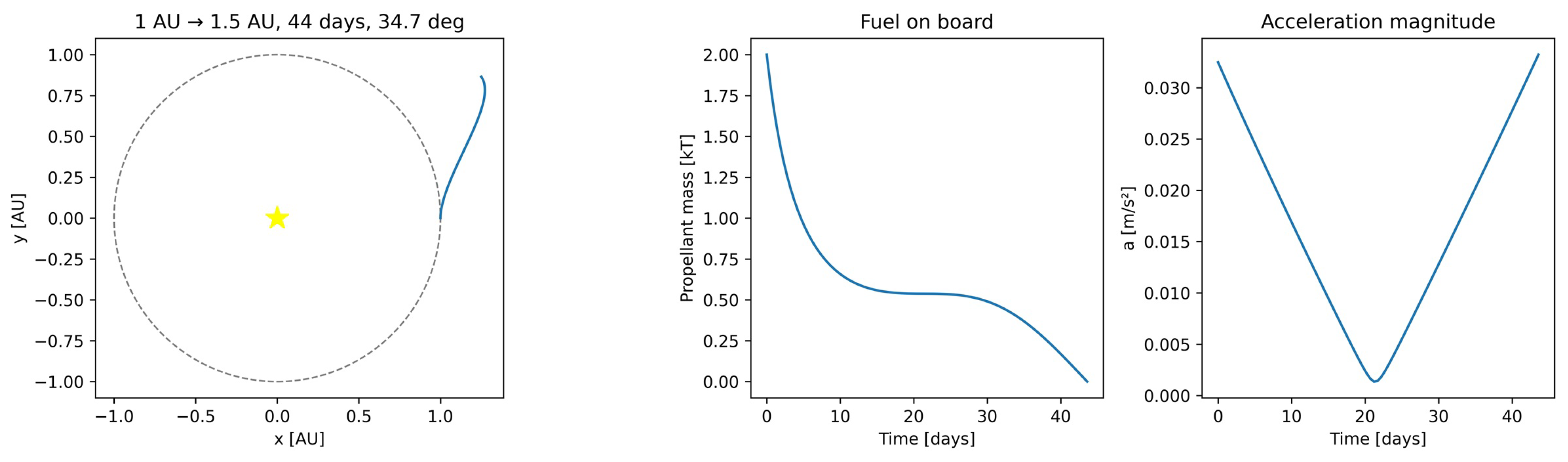

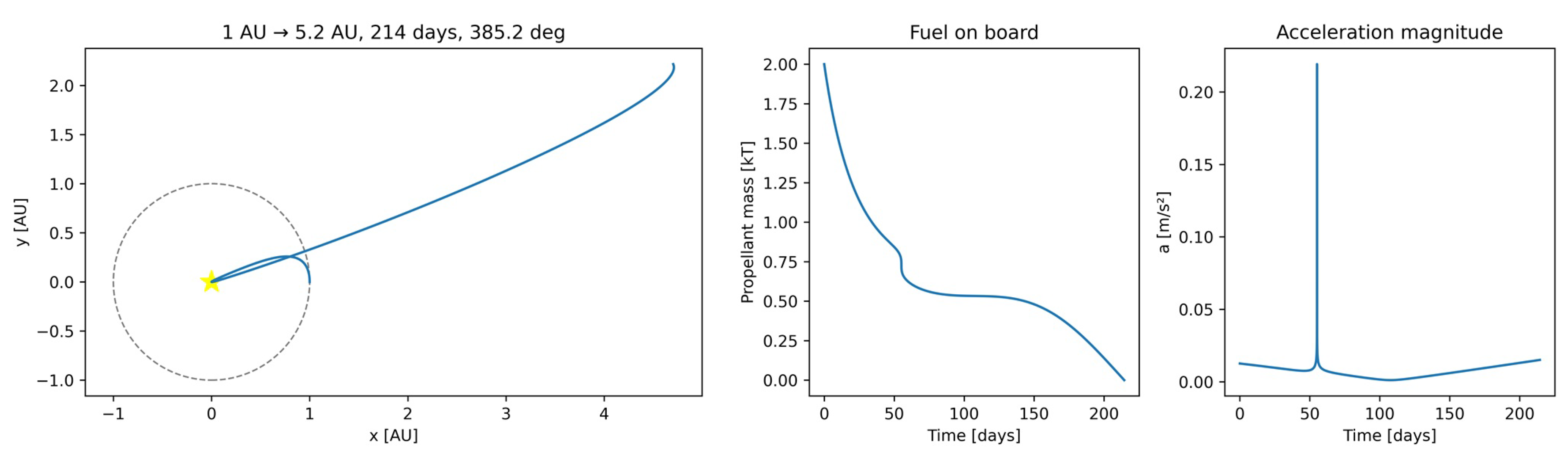

7. Results

| True Anomaly | Origin Radius (AU) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (∘) | 0.390 | 0.720 | 1.520 | 5.200 | 9.580 | 19.220 | 30.050 |

| 0 | N/A | N/A | 95.77 | 220.50 | 337.82 | 539.56 | 724.64 |

| 5 | N/A | N/A | 84.93 | 214.67 | 331.66 | 532.46 | 716.76 |

| 10 | N/A | N/A | 73.02 | 208.91 | 325.51 | 525.31 | 708.76 |

| 15 | N/A | N/A | 60.90 | 203.30 | 319.44 | 518.16 | 700.69 |

| 20 | N/A | N/A | 51.21 | 197.97 | 313.53 | 511.08 | 692.65 |

| 25 | N/A | N/A | 45.92 | 192.97 | 307.82 | 504.14 | 684.70 |

| 30 | N/A | 32.29 | 43.85 | 188.36 | 302.39 | 497.40 | 676.91 |

| 35 | N/A | 28.90 | 43.65 | 184.19 | 297.29 | 490.93 | 669.34 |

| 40 | N/A | 28.92 | 44.59 | 180.58 | 292.60 | 484.76 | 662.08 |

| 45 | N/A | 29.84 | 46.15 | 177.50 | 288.32 | 478.95 | 655.19 |

| 50 | N/A | 31.18 | 48.07 | 174.95 | 284.47 | 473.58 | 648.68 |

| 55 | N/A | 32.73 | 50.23 | 172.91 | 281.10 | 468.66 | 642.61 |

| 60 | N/A | 34.42 | 52.55 | 171.44 | 278.26 | 464.19 | 637.03 |

| 65 | N/A | 36.19 | 54.97 | 170.45 | 275.88 | 460.24 | 631.95 |

| 70 | N/A | 37.99 | 57.46 | 169.91 | 273.97 | 456.77 | 627.37 |

| 75 | N/A | 39.83 | 59.98 | 169.77 | 272.50 | 453.80 | 623.40 |

| 80 | N/A | 41.69 | 62.51 | 170.05 | 271.54 | 451.38 | 619.96 |

| 85 | 49.67 | 43.54 | 65.05 | 170.67 | 270.98 | 449.42 | 617.07 |

| 90 | 46.93 | 45.39 | 67.57 | 171.58 | 270.81 | 447.98 | 614.71 |

| 95 | 45.83 | 47.22 | 70.08 | 172.74 | 270.99 | 447.01 | 612.86 |

| 100 | 45.46 | 49.03 | 72.54 | 174.16 | 271.54 | 446.45 | 611.58 |

| 105 | 45.51 | 50.82 | 74.97 | 175.77 | 272.38 | 446.33 | 610.73 |

| 110 | 45.85 | 52.58 | 77.36 | 177.54 | 273.50 | 446.58 | 610.38 |

| 115 | 46.37 | 54.31 | 79.67 | 179.42 | 274.83 | 447.17 | 610.46 |

| 120 | 47.00 | 55.99 | 81.93 | 181.41 | 276.38 | 448.10 | 610.91 |

| 125 | 47.72 | 57.63 | 84.12 | 183.47 | 278.09 | 449.30 | 611.70 |

| 130 | 48.49 | 59.22 | 86.23 | 185.58 | 279.93 | 450.74 | 612.82 |

| 135 | 49.31 | 60.76 | 88.27 | 187.70 | 281.87 | 452.36 | 614.21 |

| 140 | 50.15 | 62.24 | 90.22 | 189.81 | 283.87 | 454.17 | 615.83 |

| 145 | 51.02 | 63.68 | 92.07 | 191.90 | 285.92 | 456.10 | 617.64 |

| 150 | 51.89 | 65.04 | 93.84 | 193.93 | 287.97 | 458.09 | 619.58 |

| 155 | 52.75 | 66.35 | 95.49 | 195.89 | 289.99 | 460.14 | 621.61 |

| 160 | 53.61 | 67.60 | 97.05 | 197.76 | 291.96 | 462.19 | 623.69 |

| 165 | 54.45 | 68.79 | 98.49 | 199.53 | 293.86 | 464.22 | 625.79 |

| 170 | 55.28 | 69.89 | 99.84 | 201.18 | 295.66 | 466.18 | 627.86 |

| 175 | 56.08 | 70.94 | 101.08 | 202.72 | 297.35 | 468.07 | 629.88 |

| 180 | 56.86 | 71.91 | 102.23 | 204.13 | 298.92 | 469.85 | 631.81 |

| 185 | 57.61 | 72.83 | 103.26 | 205.39 | 300.35 | 471.50 | 633.62 |

| 190 | 58.33 | 73.68 | 104.18 | 206.52 | 301.64 | 473.03 | 635.31 |

| 195 | 59.02 | 74.46 | 105.02 | 207.52 | 302.79 | 474.40 | 636.87 |

| 200 | 59.68 | 75.17 | 105.76 | 208.39 | 303.80 | 475.63 | 638.27 |

| 205 | 60.31 | 75.83 | 106.41 | 209.14 | 304.67 | 476.72 | 639.52 |

| 210 | 60.90 | 76.42 | 106.97 | 209.77 | 305.42 | 477.67 | 640.64 |

| 215 | 61.46 | 76.96 | 107.45 | 210.30 | 306.06 | 478.48 | 641.61 |

| 220 | 61.98 | 77.44 | 107.87 | 210.73 | 306.58 | 479.17 | 642.44 |

| 225 | 62.47 | 77.86 | 108.21 | 211.07 | 306.99 | 479.75 | 643.17 |

| 230 | 62.93 | 78.23 | 108.48 | 211.34 | 307.32 | 480.22 | 643.76 |

| 235 | 63.35 | 78.57 | 108.69 | 211.52 | 307.58 | 480.60 | 644.27 |

| 240 | 63.75 | 78.84 | 108.84 | 211.65 | 307.75 | 480.90 | 644.68 |

| 245 | 64.10 | 79.07 | 108.95 | 211.72 | 307.87 | 481.14 | 645.02 |

| 250 | 64.44 | 79.27 | 109.01 | 211.75 | 307.94 | 481.31 | 645.30 |

| 255 | 64.74 | 79.41 | 109.03 | 211.73 | 307.97 | 481.43 | 645.51 |

| 260 | 65.01 | 79.53 | 109.01 | 211.68 | 307.96 | 481.51 | 645.68 |

| 265 | 65.26 | 79.62 | 108.97 | 211.61 | 307.92 | 481.57 | 645.82 |

| 270 | 65.49 | 79.66 | 108.88 | 211.51 | 307.87 | 481.60 | 645.93 |

| 275 | 65.69 | 79.68 | 108.78 | 211.39 | N/A | 481.61 | 646.03 |

| 280 | 65.86 | 79.68 | 108.66 | 211.26 | N/A | 481.62 | 646.12 |

| 285 | 66.02 | 79.65 | 108.52 | 211.14 | N/A | 481.62 | 646.21 |

| 290 | 66.16 | 79.61 | 108.36 | 211.00 | N/A | 481.63 | 646.31 |

| 295 | 66.27 | 79.54 | 108.21 | 210.88 | N/A | 481.66 | 646.43 |

| (∘) | 0.390 | 0.720 | 1.520 | 5.200 | 9.580 | 19.220 | 30.050 |

| 300 | 66.38 | 79.47 | 108.04 | 210.75 | N/A | 481.71 | 646.57 |

| 305 | 66.47 | 79.37 | 107.87 | 210.65 | N/A | 481.78 | 646.75 |

| 310 | 66.56 | 79.27 | 107.70 | 210.56 | N/A | 481.89 | 646.96 |

| 315 | 66.63 | 79.17 | 107.54 | 210.49 | N/A | 482.04 | 647.22 |

| 320 | 66.70 | 79.07 | 107.39 | 210.44 | N/A | 482.24 | 647.54 |

| 325 | 66.76 | 78.97 | 107.25 | 210.43 | N/A | 482.48 | 647.93 |

| 330 | 66.83 | 78.89 | 107.13 | 210.45 | N/A | 482.79 | 648.38 |

| 335 | 66.90 | 78.80 | 107.03 | 210.51 | N/A | 483.16 | 648.91 |

| 340 | 66.99 | 78.74 | 106.97 | 210.60 | N/A | 483.61 | 649.55 |

| 345 | 67.08 | 78.70 | 106.94 | 210.75 | N/A | 484.14 | 650.27 |

| 350 | 67.19 | 78.70 | 106.94 | 210.96 | N/A | 484.76 | 651.11 |

| 355 | 67.32 | 78.73 | 107.00 | 211.22 | N/A | 485.47 | 652.06 |

| 360 | 67.48 | 78.82 | 107.10 | 211.54 | N/A | 486.28 | 653.13 |

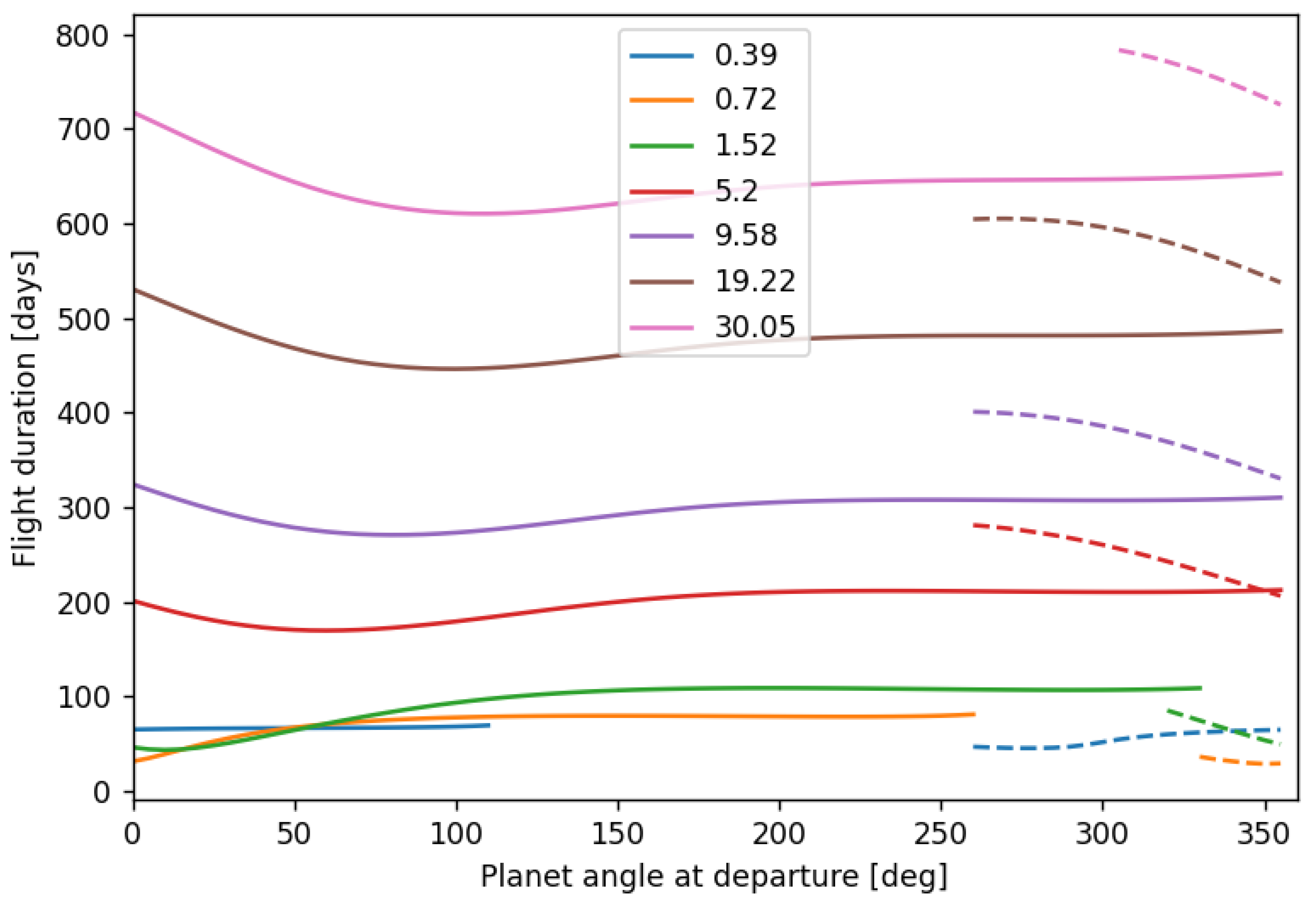

| True Anomaly | Origin Radius (AU) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (∘) | 0.390 | 0.720 | 1.520 | 5.200 | 9.580 | 19.220 | 30.050 |

| -100 | 46.94 | N/A | 137.22 | 281.20 | 401.02 | 604.64 | 789.45 |

| -95 | 46.28 | N/A | 133.71 | 279.71 | 400.45 | 605.10 | 790.72 |

| -90 | 45.79 | N/A | 130.04 | 277.91 | 399.53 | 605.19 | 791.59 |

| -85 | 45.47 | N/A | 126.23 | 275.81 | 398.24 | 604.86 | 792.02 |

| -80 | 45.48 | N/A | 122.29 | 273.35 | 396.55 | 604.09 | 791.99 |

| -75 | 45.94 | N/A | 118.16 | 270.58 | 394.50 | 602.83 | 791.40 |

| -70 | 47.06 | N/A | 113.88 | 267.49 | 392.03 | 601.11 | 790.28 |

| -65 | 49.09 | N/A | 109.49 | 264.09 | 389.19 | 598.93 | 788.57 |

| -60 | 51.87 | N/A | 104.93 | 260.40 | 385.96 | 596.20 | 786.30 |

| -55 | 54.64 | N/A | 100.21 | 256.39 | 382.37 | 593.01 | 783.38 |

| -50 | 56.91 | N/A | 95.40 | 252.12 | 378.37 | 589.32 | 779.89 |

| -45 | 58.67 | N/A | 90.40 | 247.61 | 374.03 | 585.12 | 775.84 |

| -40 | 60.08 | 42.22 | 85.27 | 242.85 | 369.36 | 580.46 | 771.21 |

| -35 | 61.20 | 39.24 | 80.06 | 237.91 | 364.41 | 575.38 | 766.07 |

| -30 | 62.11 | 36.39 | 74.72 | 232.81 | 359.17 | 569.87 | 760.34 |

| -25 | 62.88 | 33.74 | 69.36 | 227.59 | 353.71 | 564.01 | 754.16 |

| -20 | 63.51 | 31.37 | 64.05 | 222.28 | 348.05 | 557.81 | 747.56 |

| -15 | 64.05 | 29.82 | 58.75 | 216.95 | 342.25 | 551.33 | 740.58 |

| -10 | 64.50 | 28.85 | 53.84 | 211.66 | 336.37 | 544.62 | 733.26 |

| -5 | 64.88 | 29.29 | 49.74 | 206.47 | 330.45 | 537.73 | 725.67 |

| 0 | 65.21 | 31.36 | 46.31 | 201.42 | 324.55 | 530.74 | 717.89 |

| 5 | 65.49 | 34.83 | 44.22 | 196.60 | 318.73 | 523.70 | 709.96 |

| 10 | 65.72 | 39.16 | 43.58 | 192.04 | 313.06 | 516.67 | 701.98 |

| 15 | 65.92 | 43.77 | 44.15 | 187.81 | 307.57 | 509.73 | 694.00 |

| 20 | 66.09 | 48.26 | 45.83 | 183.96 | 302.33 | 502.94 | 686.10 |

| 25 | 66.23 | 52.45 | 48.22 | 180.57 | 297.40 | 496.34 | 678.35 |

| 30 | 66.35 | 56.21 | 51.07 | 177.63 | 292.84 | 490.00 | 670.82 |

| 35 | 66.46 | 59.57 | 54.25 | 175.16 | 288.65 | 483.95 | 663.55 |

| 40 | 66.54 | 62.47 | 57.61 | 173.14 | 284.87 | 478.29 | 656.62 |

| 45 | 66.63 | 65.02 | 61.04 | 171.60 | 281.51 | 473.04 | 650.08 |

| 50 | 66.70 | 67.22 | 64.50 | 170.57 | 278.64 | 468.22 | 643.97 |

| 55 | 66.77 | 69.13 | 67.94 | 169.97 | 276.22 | 463.84 | 638.28 |

| 60 | 66.84 | 70.77 | 71.32 | 169.78 | 274.27 | 459.96 | 633.13 |

| 65 | 66.92 | 72.19 | 74.61 | 169.97 | 272.76 | 456.55 | 628.48 |

| 70 | 67.01 | 73.42 | 77.78 | 170.54 | 271.68 | 453.63 | 624.35 |

| 75 | 67.12 | 74.48 | 80.81 | 171.43 | 271.05 | 451.26 | 620.77 |

| 80 | 67.24 | 75.39 | 83.70 | 172.59 | 270.82 | 449.33 | 617.75 |

| 85 | 67.41 | 76.18 | 86.42 | 173.99 | 270.94 | 447.93 | 615.28 |

| 90 | 67.62 | 76.85 | 88.98 | 175.64 | 271.40 | 446.97 | 613.33 |

| 95 | N/A | 77.43 | 91.36 | 177.44 | 272.19 | 446.44 | 611.88 |

| 100 | N/A | 77.92 | 93.56 | 179.39 | 273.28 | 446.33 | 610.94 |

| 105 | N/A | 78.33 | 95.57 | 181.45 | 274.59 | 446.60 | 610.43 |

| 110 | N/A | 78.67 | 97.42 | 183.58 | 276.10 | 447.20 | 610.38 |

| 115 | N/A | 78.95 | 99.07 | 185.77 | 277.82 | 448.15 | 610.75 |

| 120 | N/A | 79.18 | 100.57 | 187.97 | 279.67 | 449.37 | 611.47 |

| 125 | N/A | 79.36 | 101.92 | 190.15 | 281.62 | 450.82 | 612.50 |

| 130 | N/A | 79.49 | 103.11 | 192.30 | 283.64 | 452.46 | 613.81 |

| 135 | N/A | 79.59 | 104.14 | 194.39 | 285.71 | 454.29 | 615.39 |

| 140 | N/A | 79.65 | 105.06 | 196.39 | 287.79 | 456.23 | 617.15 |

| 145 | N/A | 79.68 | 105.85 | 198.29 | 289.84 | 458.24 | 619.06 |

| 150 | N/A | 79.69 | 106.54 | 200.09 | 291.84 | 460.29 | 621.08 |

| 155 | N/A | 79.66 | 107.11 | 201.74 | 293.77 | 462.35 | 623.15 |

| 160 | N/A | 79.63 | 107.60 | 203.26 | 295.60 | 464.39 | 625.26 |

| 165 | N/A | 79.57 | 108.00 | 204.64 | 297.31 | 466.36 | 627.35 |

| 170 | N/A | 79.49 | 108.32 | 205.88 | 298.90 | 468.25 | 629.38 |

| 175 | N/A | 79.41 | 108.58 | 206.99 | 300.34 | 470.02 | 631.35 |

| 180 | N/A | 79.32 | 108.76 | 207.93 | 301.65 | 471.67 | 633.20 |

| 185 | N/A | 79.22 | 108.90 | 208.75 | 302.80 | 473.19 | 634.91 |

| (∘) | 0.390 | 0.720 | 1.520 | 5.200 | 9.580 | 19.220 | 30.050 |

| 190 | N/A | 79.12 | 108.98 | 209.46 | 303.82 | 474.54 | 636.50 |

| 195 | N/A | 79.02 | 109.02 | 210.05 | 304.69 | 475.76 | 637.95 |

| 200 | N/A | 78.93 | 109.03 | 210.52 | 305.45 | 476.84 | 639.25 |

| 205 | N/A | 78.85 | 108.99 | 210.92 | 306.08 | 477.77 | 640.40 |

| 210 | N/A | 78.77 | 108.93 | 211.22 | 306.59 | 478.57 | 641.40 |

| 215 | N/A | 78.72 | 108.84 | 211.44 | 307.01 | 479.25 | 642.26 |

| 220 | N/A | 78.70 | 108.73 | 211.59 | 307.34 | 479.81 | 643.01 |

| 225 | N/A | 78.71 | 108.60 | 211.70 | 307.59 | 480.28 | 643.64 |

| 230 | N/A | 78.76 | 108.46 | 211.74 | 307.76 | 480.64 | 644.17 |

| 235 | N/A | 78.87 | 108.30 | 211.74 | 307.88 | 480.93 | 644.60 |

| 240 | N/A | 79.06 | 108.15 | 211.71 | 307.94 | 481.17 | 644.95 |

| 245 | N/A | N/A | 107.97 | 211.64 | 307.97 | 481.33 | 645.24 |

| 250 | N/A | N/A | 107.81 | 211.56 | 307.96 | 481.44 | 645.47 |

| 255 | N/A | N/A | 107.65 | 211.45 | 307.92 | 481.52 | 645.64 |

| 260 | N/A | N/A | 107.49 | 211.33 | 307.87 | 481.57 | 645.79 |

8. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Direct Method Using Spline Parameterization

- 1.

- A fixed number of N control points, for , were defined along the time axis of the transfer. The endpoints, and , were fixed to match the start and end positions of the transfer arc. The initial and final velocities were enforced by connecting the transfer arc to the initial and final circular orbits.

- 2.

- The positions of the intermediate control points were the free variables for the optimization.

- 3.

- For any given set of control points, two cubic splines, and , were fitted to create a continuous and smooth trajectory . A cubic spline is defined piecewise by third-order polynomials, ensuring that the first and second derivatives (velocity and acceleration) are continuous across the entire path.

- 4.

- The required velocity and acceleration vectors were obtained by numerically differentiating the spline functions.

- 5.

- With the total acceleration known, the required thrust acceleration was calculated by subtracting the gravitational component:

- 6.

- The instantaneous mass flow rate was then determined from the thrust acceleration magnitude using (2). Integrating this rate backwards in time yielded the total propellant consumed for the maneuver.

- 7.

- A nonlinear optimizer (specifically, the Nelder–Mead method) was used to adjust the positions of the intermediate control points to minimize a cost function based on the final fuel expenditure and flight time.

Limitations and Stagnation in Local Minima

References

- Conway, B.A. (Ed.) Spacecraft Trajectory Optimization, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010.

- Pino, B.P.; Howell, K.C. An energy-informed adaptive algorithm for low-thrust spacecraft cislunar trajectory design. In Proceedings of the AAS/AIAA Space Flight Mechanics Meeting, 2020; pp. AAS 20–579. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel, J.A.; Widner, M.; Williams, J.; Batcha, A. Multi-Impulse to Time Optimal Finite Burn Trajectory Conversion. Technical report, 2020; NASA Johnson Space Center. [Google Scholar]

- Mazouffre, S. Electric propulsion for satellites and spacecraft: established technologies and novel approaches. Plasma Sources Science and Technology 2016, 25, 033002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakman, A.; Lindley, B. A review of nuclear electric fission space reactor technologies for achieving high-power output and operating with HALEU fuel. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2023, 163, 104815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.H. The Value Proposition of Multi-Megawatt Electric Power/Propulsion for the Human Exploration of Mars. In Proceedings of the International Astronautical Conference (IAC), 2019; p. number JSC-E-DAA-TN73357. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Díaz, F.R.; Carr, J.A.; Johnson, L.; Johnson, W.; Genta, G.; Maffione, P.F. Solar electric propulsion for human Mars missions. Acta Astronautica 2019, 160, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheerin, T.F.; Petro, E.; Winters, K.; Lozano, P.; Lubin, P. Fast Solar System transportation with electric propulsion powered by directed energy. Acta Astronautica 2021, 179, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiolkovsky, K.E. Exploration of cosmic space by means of reaction devices, 1903. English translation; NASA TT F-243, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Bering, E.A.; Longmier, B.W.; Ballenger, M.G.; Olsen, C.S.; Squire, J.P.; Chang Díaz, F.R. Performance studies of the VASIMR® VX-200. In Proceedings of the 49th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Orlando, FL, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, G.; Sanjurjo-Rivo, M.; Pérez Grande, D. A multi-objective variable-specific impulse maneuvers optimization methodology. Advances in Space Research 2024, 73, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, G.P.; Biblarz, O. Rocket Propulsion Elements, 9th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pontryagin, L.S.; Boltyanskii, V.G.; Gamkrelidze, R.V.; Mishchenko, E.F. The Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Pontani, M. Optimal Space Trajectories with Multiple Coast Arcs Using Modified Equinoctial Elements. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications 2021, 191, 545–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution – a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. Journal of Global Optimization 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgower, E.L.; Georg, K. Numerical Continuation Methods: An Introduction; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, M.J.D. An efficient method for finding the minimum of a function of several variables without calculating derivatives. The Computer Journal 1964, 7, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olšina, J. Time-Optimal Heliocentric Transfers With a Constant-Power, Variable-Isp Engine 2025. DOI:10.5281/zenodo.17521033. Code and data:. Available online: https://github.com/irigi/VariableISPRocketTrajectories. [CrossRef]

- Oberth, H. Die Rakete zu den Planetenr"aumen; R. Oldenbourg: Munich, Germany, 1923. English translation: The Rocket into Planetary Space. 1923. [Google Scholar]

| True Anomaly | Target Radius (AU) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (∘) | 0.390 | 0.720 | 1.520 | 5.200 | 9.580 | 19.220 | 30.050 |

| 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 220.50 | 337.82 | 539.55 | 724.65 |

| 5 | N/A | N/A | 84.99 | 214.66 | 331.66 | 532.47 | 716.76 |

| 10 | N/A | N/A | 73.01 | 208.91 | 325.52 | 525.31 | 708.75 |

| 15 | N/A | N/A | 60.88 | 203.32 | 319.44 | 518.17 | 700.69 |

| 20 | N/A | N/A | 51.35 | 197.98 | 313.53 | 511.09 | 692.64 |

| 25 | N/A | N/A | 45.94 | 192.95 | 307.83 | 504.13 | 684.71 |

| 30 | N/A | 32.66 | 43.80 | 188.35 | 302.40 | 497.40 | 676.93 |

| 35 | N/A | 29.03 | 43.63 | 184.23 | 297.29 | 490.93 | 669.37 |

| 40 | N/A | 28.92 | 44.61 | 180.59 | 292.59 | 484.76 | 662.08 |

| 45 | N/A | 29.86 | 46.15 | 177.47 | 288.32 | 478.95 | 655.19 |

| 50 | N/A | 31.19 | 48.07 | 174.94 | 284.48 | 473.58 | 648.68 |

| 55 | N/A | 32.74 | 50.23 | 172.94 | 281.10 | 468.66 | 642.60 |

| 60 | N/A | 34.42 | 52.55 | 171.44 | 278.25 | 464.20 | 637.00 |

| 65 | N/A | 36.18 | 54.96 | 170.42 | 275.88 | 460.21 | 631.92 |

| 70 | N/A | 38.00 | 57.46 | 169.90 | 273.97 | 456.76 | 627.37 |

| 75 | N/A | 39.84 | 59.98 | 169.80 | 272.50 | 453.79 | 623.38 |

| 80 | N/A | 41.69 | 62.51 | 170.05 | 271.54 | 451.39 | 619.93 |

| 85 | N/A | 43.55 | 65.05 | 170.65 | 270.98 | 449.42 | 617.06 |

| 90 | 46.97 | 45.39 | 67.58 | 171.57 | 270.81 | 447.98 | 614.72 |

| 95 | 45.78 | 47.22 | 70.07 | 172.77 | 270.99 | 447.01 | 612.89 |

| 100 | 45.47 | 49.04 | 72.55 | 174.17 | 271.54 | 446.46 | 611.58 |

| 105 | 45.54 | 50.82 | 74.97 | 175.77 | 272.38 | 446.33 | 610.73 |

| 110 | 45.86 | 52.58 | 77.35 | 177.53 | 273.50 | 446.57 | 610.37 |

| 115 | 46.37 | 54.30 | 79.68 | 179.42 | 274.83 | 447.19 | 610.43 |

| 120 | 47.00 | 55.99 | 81.93 | 181.41 | 276.38 | 448.11 | 610.89 |

| 125 | 47.72 | 57.63 | 84.12 | 183.48 | 278.09 | 449.29 | 611.70 |

| 130 | 48.49 | 59.22 | 86.24 | 185.58 | 279.93 | 450.73 | 612.82 |

| 135 | 49.31 | 60.76 | 88.27 | 187.70 | 281.87 | 452.36 | 614.21 |

| 140 | 50.16 | 62.24 | 90.22 | 189.81 | 283.87 | 454.17 | 615.83 |

| 145 | 51.02 | 63.68 | 92.07 | 191.90 | 285.92 | 456.10 | 617.64 |

| 150 | 51.89 | 65.05 | 93.83 | 193.93 | 287.97 | 458.09 | 619.57 |

| 155 | 52.75 | 66.36 | 95.50 | 195.89 | 289.99 | 460.14 | 621.61 |

| 160 | 53.61 | 67.61 | 97.05 | 197.76 | 291.96 | 462.19 | 623.69 |

| 165 | 54.46 | 68.79 | 98.50 | 199.53 | 293.86 | 464.22 | 625.79 |

| 170 | 55.28 | 69.89 | 99.84 | 201.18 | 295.66 | 466.18 | 627.86 |

| 175 | 56.08 | 70.94 | 101.08 | 202.72 | 297.35 | 468.07 | 629.88 |

| 180 | 56.86 | 71.91 | 102.22 | 204.12 | 298.92 | 469.85 | 631.81 |

| 185 | 57.61 | 72.83 | 103.25 | 205.38 | 300.34 | 471.50 | 633.63 |

| 190 | 58.34 | 73.67 | 104.18 | 206.51 | 301.63 | 473.03 | 635.31 |

| 195 | 59.03 | 74.46 | 105.02 | 207.53 | 302.79 | 474.41 | 636.87 |

| 200 | 59.68 | 75.17 | 105.75 | 208.39 | 303.79 | 475.63 | 638.27 |

| 205 | 60.31 | 75.83 | 106.40 | 209.13 | 304.67 | 476.72 | 639.53 |

| 210 | 60.90 | 76.42 | 106.97 | 209.77 | 305.42 | 477.67 | 640.64 |

| 215 | 61.45 | 76.96 | 107.46 | 210.31 | 306.05 | 478.48 | 641.61 |

| 220 | 61.97 | 77.44 | 107.86 | 210.74 | 306.57 | 479.17 | 642.45 |

| 225 | 62.47 | 77.86 | 108.20 | 211.07 | 306.99 | 479.74 | 643.16 |

| 230 | 62.93 | 78.23 | 108.48 | 211.33 | 307.32 | 480.22 | 643.76 |

| 235 | 63.35 | 78.56 | 108.69 | 211.52 | 307.57 | 480.60 | 644.27 |

| 240 | 63.74 | 78.84 | 108.85 | 211.65 | 307.75 | 480.91 | 644.68 |

| 245 | 64.10 | 79.07 | 108.95 | 211.72 | 307.87 | 481.14 | 645.02 |

| 250 | 64.44 | 79.26 | 109.01 | 211.75 | 307.94 | 481.31 | 645.29 |

| 255 | 64.74 | 79.42 | 109.03 | 211.73 | 307.97 | 481.43 | 645.51 |

| 260 | 65.02 | 79.54 | 109.01 | 211.68 | 307.96 | 481.51 | 645.68 |

| 265 | 65.26 | 79.62 | 108.96 | 211.60 | 307.92 | 481.57 | 645.82 |

| 270 | 65.48 | 79.66 | 108.88 | 211.50 | 307.87 | 481.59 | 645.94 |

| 275 | 65.69 | 79.69 | 108.78 | 211.40 | 307.79 | 481.61 | 646.04 |

| 280 | 65.86 | 79.69 | 108.66 | 211.27 | 307.72 | 481.62 | 646.12 |

| 285 | 66.02 | 79.65 | 108.52 | 211.14 | 307.63 | 481.62 | 646.22 |

| 290 | 66.16 | 79.61 | 108.37 | 211.00 | 307.55 | 481.64 | 646.31 |

| 295 | 66.27 | 79.54 | 108.21 | 210.88 | 307.48 | 481.67 | 646.43 |

| 300 | 66.38 | 79.47 | 108.03 | 210.75 | 307.42 | 481.71 | 646.57 |

| 305 | 66.47 | 79.37 | 107.87 | 210.65 | 307.38 | 481.79 | 646.74 |

| 310 | 66.56 | 79.27 | 107.70 | 210.56 | 307.37 | 481.89 | 646.96 |

| 315 | 66.63 | 79.18 | 107.54 | 210.49 | 307.38 | 482.04 | 647.22 |

| 320 | 66.70 | 79.07 | 107.39 | 210.45 | 307.43 | 482.23 | 647.54 |

| 325 | 66.77 | 78.98 | 107.26 | 210.43 | 307.52 | 482.48 | 647.92 |

| 330 | 66.84 | 78.88 | 107.14 | 210.45 | 307.64 | 482.79 | 648.38 |

| 335 | 66.90 | 78.81 | 107.03 | 210.51 | 307.82 | 483.16 | 648.91 |

| 340 | 66.99 | 78.74 | 106.97 | 210.61 | 308.06 | 483.61 | 649.54 |

| 345 | 67.08 | 78.70 | 106.94 | 210.75 | 308.36 | 484.14 | 650.27 |

| 350 | 67.19 | 78.70 | 106.94 | 210.96 | 308.71 | 484.76 | 651.11 |

| 355 | 67.32 | 78.73 | 107.00 | 211.22 | 309.15 | 485.47 | 652.06 |

| 360 | 67.49 | 78.81 | 107.10 | 211.54 | 309.66 | 486.29 | 653.13 |

| True Anomaly | Target Radius (AU) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (∘) | 0.390 | 0.720 | 1.520 | 5.200 | 9.580 | 19.220 | 30.050 |

| -100 | 46.96 | N/A | N/A | 281.19 | 401.02 | 604.63 | N/A |

| -95 | 46.26 | N/A | N/A | 279.72 | 400.45 | 605.12 | N/A |

| -90 | 45.76 | N/A | N/A | 277.93 | 399.55 | 605.20 | N/A |

| -85 | 45.48 | N/A | N/A | 275.79 | 398.22 | 604.85 | N/A |

| (∘) | 0.390 | 0.720 | 1.520 | 5.200 | 9.580 | 19.220 | 30.050 |

| -80 | 45.50 | N/A | N/A | 273.34 | 396.54 | 604.07 | N/A |

| -75 | 45.92 | N/A | N/A | 270.57 | 394.49 | 602.85 | N/A |

| -70 | 47.06 | N/A | N/A | 267.50 | 392.06 | 601.12 | N/A |

| -65 | 49.08 | N/A | N/A | 264.11 | 389.20 | 598.91 | N/A |

| -60 | 51.87 | N/A | N/A | 260.40 | 385.96 | 596.20 | N/A |

| -55 | 54.65 | N/A | N/A | 256.39 | 382.34 | 592.99 | 783.40 |

| -50 | 56.90 | N/A | N/A | 252.12 | 378.37 | 589.31 | 779.93 |

| -45 | 58.68 | N/A | N/A | 247.60 | 374.05 | 585.12 | 775.84 |

| -40 | 60.08 | N/A | 85.30 | 242.86 | 369.37 | 580.49 | 771.21 |

| -35 | 61.19 | N/A | 80.06 | 237.92 | 364.40 | 575.39 | 766.05 |

| -30 | 62.11 | 36.38 | 74.72 | 232.82 | 359.17 | 569.87 | 760.36 |

| -25 | 62.88 | 33.69 | 69.37 | 227.58 | 353.71 | 564.00 | 754.17 |

| -20 | 63.51 | 31.65 | 64.02 | 222.28 | 348.06 | 557.81 | 747.56 |

| -15 | 64.05 | 29.77 | 58.87 | 216.96 | 342.25 | 551.34 | 740.58 |

| -10 | 64.50 | 28.86 | 53.88 | 211.67 | 336.37 | 544.62 | 733.26 |

| -5 | 64.89 | 29.30 | 49.74 | 206.46 | 330.45 | 537.74 | 725.67 |

| 0 | 65.21 | 31.38 | 46.38 | 201.41 | 324.55 | 530.74 | 717.88 |

| 5 | 65.48 | 34.85 | 44.28 | 196.58 | 318.72 | 523.70 | 709.96 |

| 10 | 65.72 | 39.16 | 43.59 | 192.04 | 313.06 | 516.69 | 701.98 |

| 15 | 65.92 | 43.78 | 44.17 | 187.83 | 307.58 | 509.73 | 694.01 |

| 20 | 66.09 | 48.26 | 45.84 | 184.00 | 302.34 | 502.93 | 686.11 |

| 25 | 66.23 | 52.44 | 48.21 | 180.58 | 297.40 | 496.34 | 678.37 |

| 30 | 66.35 | 56.21 | 51.07 | 177.61 | 292.82 | 490.00 | 670.84 |

| 35 | 66.45 | 59.57 | 54.25 | 175.13 | 288.65 | 483.96 | 663.57 |

| 40 | 66.55 | 62.47 | 57.60 | 173.15 | 284.87 | 478.29 | 656.62 |

| 45 | 66.63 | 65.02 | 61.04 | 171.63 | 281.52 | 473.04 | 650.08 |

| 50 | 66.70 | 67.23 | 64.51 | 170.57 | 278.62 | 468.22 | 643.97 |

| 55 | 66.77 | 69.13 | 67.95 | 169.94 | 276.22 | 463.83 | 638.30 |

| 60 | 66.84 | 70.78 | 71.31 | 169.78 | 274.27 | 459.92 | 633.10 |

| 65 | 66.91 | 72.19 | 74.60 | 169.99 | 272.76 | 456.56 | 628.48 |

| 70 | 67.01 | 73.43 | 77.78 | 170.54 | 271.68 | 453.63 | 624.33 |

| 75 | 67.11 | 74.48 | 80.81 | 171.40 | 271.05 | 451.26 | 620.80 |

| 80 | 67.24 | 75.39 | 83.70 | 172.59 | 270.82 | 449.33 | 617.74 |

| 85 | 67.41 | 76.18 | 86.43 | 174.01 | 270.94 | 447.93 | 615.27 |

| 90 | 67.62 | 76.85 | 88.98 | 175.63 | 271.40 | 446.97 | 613.30 |

| 95 | 67.90 | 77.44 | 91.37 | 177.43 | 272.19 | 446.44 | 611.88 |

| 100 | 68.28 | 77.91 | 93.55 | 179.39 | 273.28 | 446.33 | 610.94 |

| 105 | 68.79 | 78.33 | 95.58 | 181.45 | 274.59 | 446.59 | 610.43 |

| 110 | 69.52 | 78.67 | 97.41 | 183.58 | 276.10 | 447.23 | 610.40 |

| 115 | N/A | 78.96 | 99.09 | 185.77 | 277.82 | 448.16 | 610.75 |

| 120 | N/A | 79.18 | 100.57 | 187.96 | 279.67 | 449.36 | 611.45 |

| 125 | N/A | 79.36 | 101.92 | 190.15 | 281.62 | 450.81 | 612.49 |

| 130 | N/A | 79.50 | 103.10 | 192.30 | 283.64 | 452.46 | 613.81 |

| 135 | N/A | 79.59 | 104.14 | 194.39 | 285.71 | 454.29 | 615.39 |

| 140 | N/A | 79.65 | 105.06 | 196.39 | 287.79 | 456.23 | 617.15 |

| 145 | N/A | 79.68 | 105.84 | 198.29 | 289.84 | 458.24 | 619.06 |

| 150 | N/A | 79.69 | 106.53 | 200.09 | 291.84 | 460.29 | 621.07 |

| 155 | N/A | 79.66 | 107.11 | 201.74 | 293.77 | 462.35 | 623.15 |

| 160 | N/A | 79.63 | 107.59 | 203.26 | 295.60 | 464.39 | 625.26 |

| 165 | N/A | 79.57 | 107.99 | 204.64 | 297.31 | 466.36 | 627.35 |

| 170 | N/A | 79.49 | 108.32 | 205.88 | 298.90 | 468.25 | 629.38 |

| 175 | N/A | 79.41 | 108.58 | 206.97 | 300.33 | 470.02 | 631.35 |

| 180 | N/A | 79.32 | 108.76 | 207.93 | 301.64 | 471.67 | 633.19 |

| 185 | N/A | 79.22 | 108.90 | 208.75 | 302.80 | 473.19 | 634.91 |

| 190 | N/A | 79.12 | 108.99 | 209.46 | 303.81 | 474.55 | 636.50 |

| 195 | N/A | 79.02 | 109.02 | 210.05 | 304.69 | 475.76 | 637.95 |

| 200 | N/A | 78.93 | 109.02 | 210.53 | 305.44 | 476.84 | 639.25 |

| 205 | N/A | 78.85 | 109.00 | 210.92 | 306.07 | 477.78 | 640.39 |

| 210 | N/A | 78.78 | 108.93 | 211.22 | 306.59 | 478.57 | 641.39 |

| 215 | N/A | 78.72 | 108.84 | 211.44 | 307.00 | 479.25 | 642.26 |

| 220 | N/A | 78.70 | 108.73 | 211.59 | 307.33 | 479.80 | 643.01 |

| 225 | N/A | 78.71 | 108.60 | 211.69 | 307.58 | 480.28 | 643.63 |

| 230 | N/A | 78.76 | 108.46 | 211.74 | 307.76 | 480.64 | 644.16 |

| 235 | N/A | 78.87 | 108.31 | 211.74 | 307.88 | 480.94 | 644.60 |

| 240 | N/A | 79.06 | 108.14 | 211.71 | 307.95 | 481.16 | 644.95 |

| 245 | N/A | 79.33 | 107.98 | 211.64 | 307.97 | 481.33 | 645.23 |

| 250 | N/A | 79.74 | 107.81 | 211.55 | 307.96 | 481.44 | 645.46 |

| 255 | N/A | 80.32 | 107.65 | 211.45 | 307.92 | 481.52 | 645.64 |

| 260 | N/A | 81.16 | 107.49 | 211.33 | 307.86 | 481.57 | 645.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).