III. Introduction

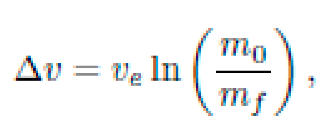

Traditional spaceflight systems rely on Newtonian mechanics and chemical propulsion, wherein thrust is generated by expelling mass at high velocity. According to the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation:

the velocity change Δv is exponentially constrained by the exhaust velocity ve and the ratio of initial to final mass (m0/mf). This places severe limits on mission duration, payload mass, and energy efficiency.

Despite advancements in ion propulsion and nuclear thermal systems, current technologies remain fundamentally tethered to the paradigm of reaction-based thrust. These systems face three key challenges:

Fuel Mass Constraints: The necessity of carrying reaction mass limits long-range capability.

Thermodynamic Inefficiencies: High entropy losses in chemical systems reduce usable energy.

Non-Optimal Trajectory Control: External forces must be applied continuously or in bursts, often resulting in energy-inefficient orbital transfers.

A Theoretical Motivation for Curvature-Based Propulsion

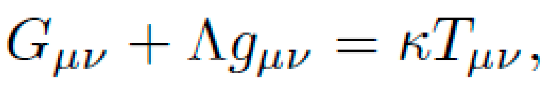

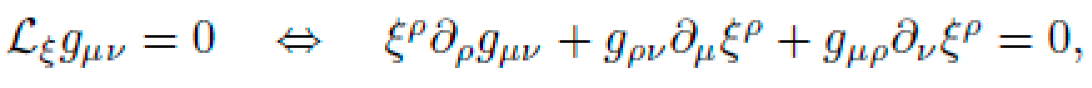

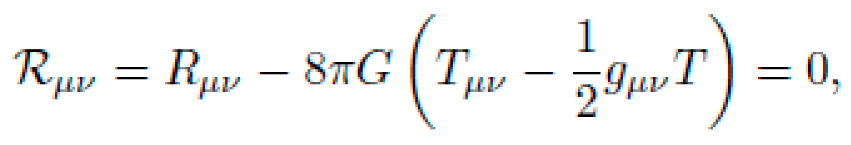

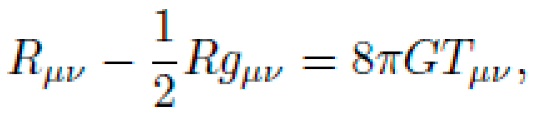

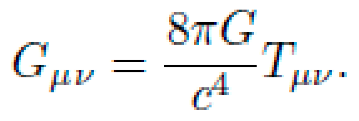

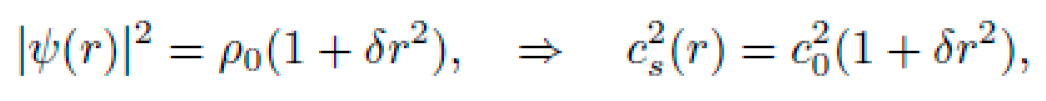

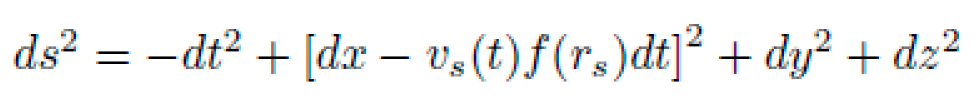

Alternative frameworks rooted in general relativity (GR) suggest that geometry itself can induce motion. The Einstein field equations,

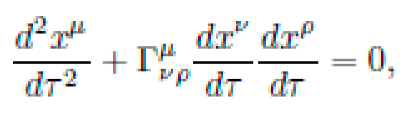

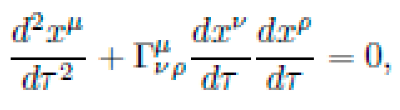

relate spacetime curvature Gμν to the energy-momentum distribution Tμν. In such a framework, geodesics—paths that locally extremize proper time—represent natural trajectories. If one engineers the curvature of spacetime appropriately, a test particle will follow an accelerated path without the application of force.

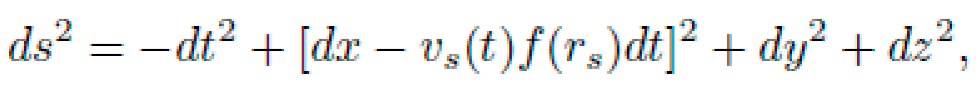

Concepts such as the Alcubierre metric [

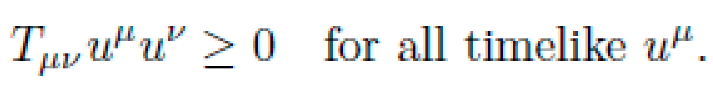

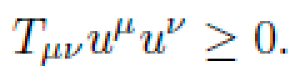

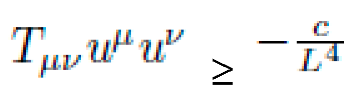

7] theoretically permit apparent superluminal motion through spacetime expansion and contraction. However, these models suffer from extreme energy requirements, typically invoking exotic matter violating the weak energy condition (WEC):

This imposes strong limitations on physical realizability.

B.NEXUS: A Symbolic Discovery Framework for Fundamental Physics

We propose a fundamentally different approach using the NEXUS framework—a symbolic discovery engine that operates from first principles. Unlike neural networks or black-box regressors, NEXUS combines symbolic computation with formal mathematical structures, including:

Differential Geometry: Metrics, connections, and curvature tensors.

Variational Calculus: Lagrangian and Hamiltonian dynamics derived from action principles.

Symmetry Analysis: Noether currents, Lie group invariance.

Symbolic Equation Synthesis: Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) representations of symbolic expressions optimized under physical constraints.

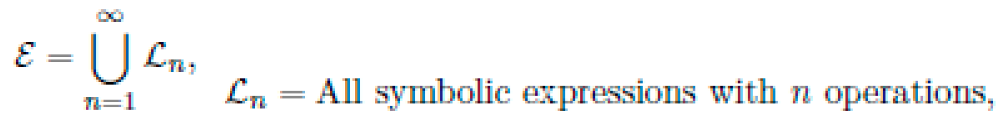

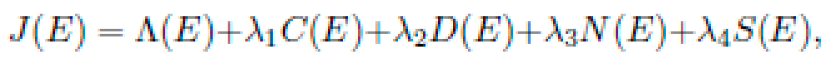

NEXUS searches a formally unbounded mathematical space of candidate equations:

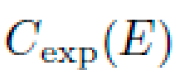

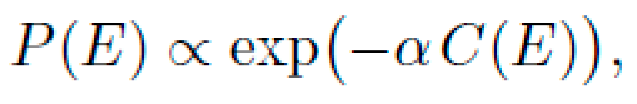

evaluating them using a composite fitness function J(E):

where Λ is the data-fit error, C the complexity, D the dimensional penalty, N the noise sensitivity, and S the symmetry deviation.

Previous results using NEXUS include:

The derivation of the Unified Emergent Field Equation (UEFE), a symbolic unification of general relativity and quantum field theory incorporating nonlocal and fractional dynamics.

A candidate resolution to the Yang-Mills mass gap, by symbolically constructing gauge-invariant Lagrangians with positive-definite spectra.

Discovery of memory-coupled evolution equations (MEUWE) with applications in quantum control and protein folding dynamics.

C.Objective of This Paper

In this paper, we extend the NEXUS framework to explore a new problem domain:

Can a geometric field configuration—curvature in spacetime or engineered field-space—induce directed motion (transport) along geodesics without the application of force?

We term this phenomenon

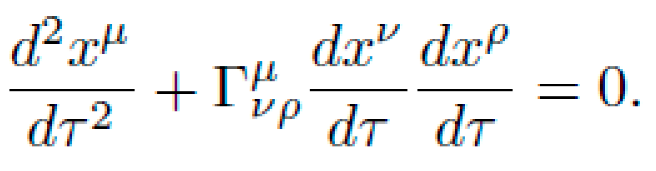

Curvature-Induced Geodesic Transport (CIGT). The goal is to derive, from first principles, a new class of metrics and field equations Gμν(x) such that the geodesic equation:

naturally results in directed motion toward a target manifold or region Mgoal, even when no external force or thrust is applied.

The core hypothesis: By manipulating the geometry itself—via real, effective, or synthetic curvature—we can realize propulsionless transport as a geodesic effect.

Using NEXUS, we aim to:

Construct symbolic metrics and field equations enabling CIGT.

Ensure physical viability via conservation laws and energy conditions.

Simulate observable consequences (e.g., test particle paths, field flow) and propose analog experimental realizations.

This work sets the foundation for an entirely new paradigm in theoretical physics and aerospace engineering: geometry-driven transport without thrust.

V NEXUS Framework

In this section, we detail the key components of the NEXUS framework—from symbolic representation and candidate generation to evolutionary optimization and experimental validation.

A. Symbolic Representation and Candidate Generation

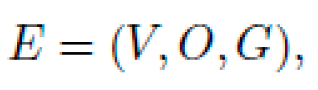

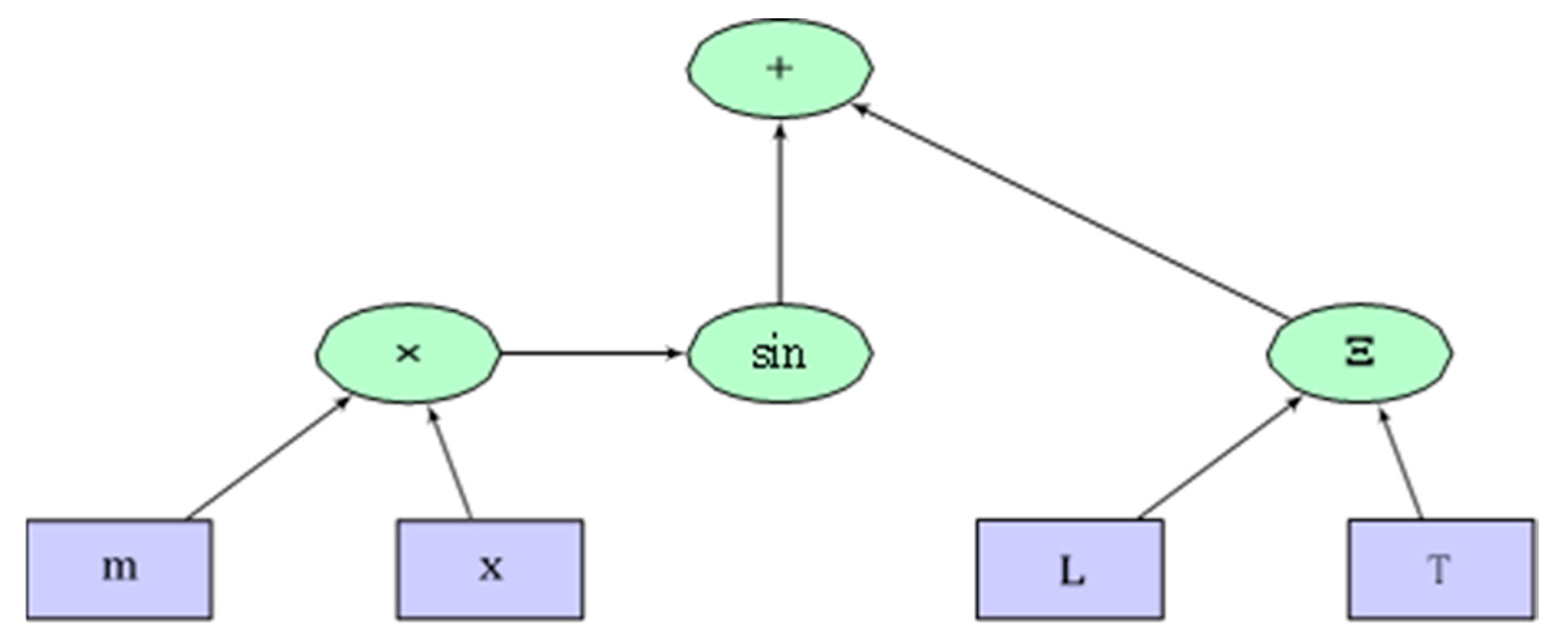

1) Graph-Based Equation Representation: Each candidate equation E is modeled as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG):

where:

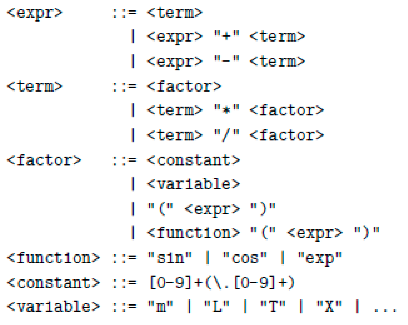

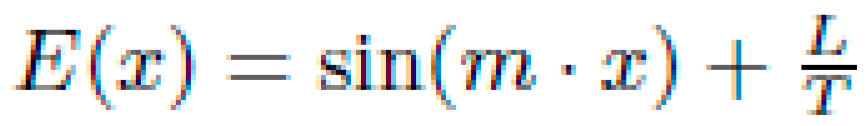

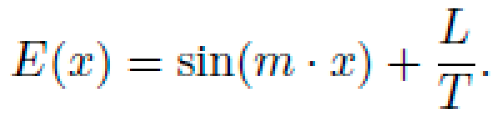

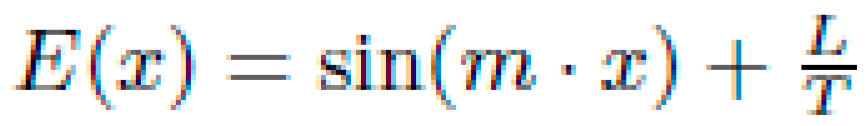

V={v1,v2,…,vN} is a set of terminal nodes (e.g., constants and variables such as m, L, T, X).

O={o1,o2,…,oM} comprises operator nodes (e.g., +, -, ×, ÷, sin, cos, exp).

G⊆(V∪O)2 encodes the syntactic structure.

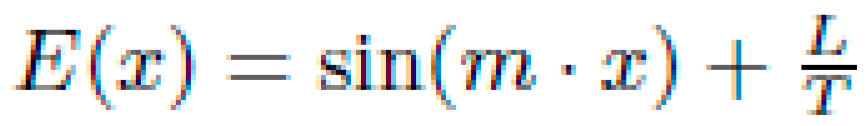

Example: Figure 1 illustrates the DAG for the candidate equation:

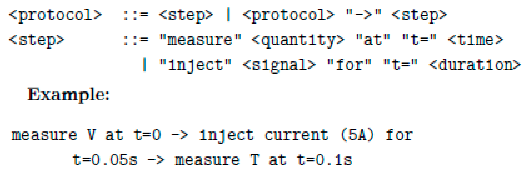

2) BNF Grammar for Equation Generatio: Candidates are generated using the following BNF grammar to ensure syntactic correctness:

B. Exploration of the Infinite Candidate Space

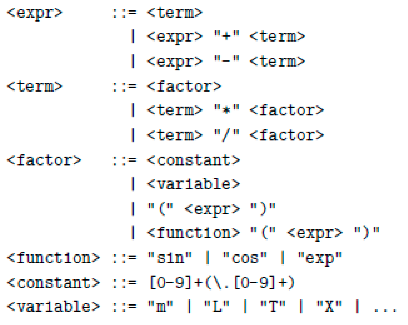

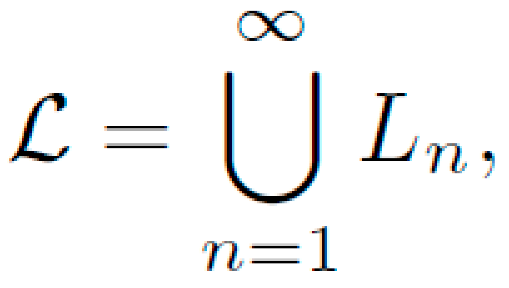

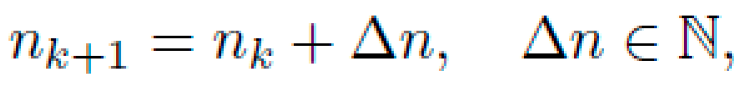

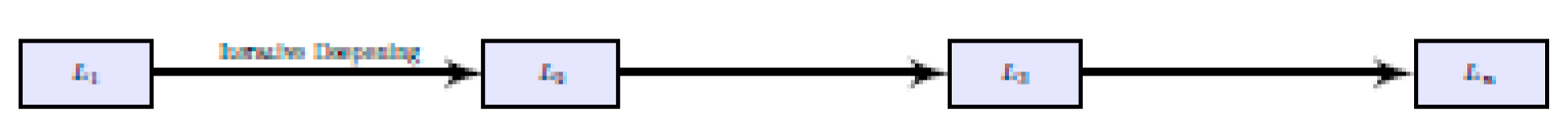

1) Iterative Deepening Strategy: We define the candidate space as:

with Ln containing all candidate equations (as DAGs) with at most n operators. An iterative deepening approach is used:

ensuring every candidate in L is eventually sampled.

2) Hierarchical Monte Carlo Sampling: Within each level Ln, candidates are sampled with probability:

where the complexity measure is:

C(E)=w1⋅(number of nodes)+w2⋅(tree depth)+w3⋅(operator weights)

Hyperparameters α,w1,w2, and w3 are tuned via meta-optimization.

Figure 2 schematically depicts the iterative deepening process.

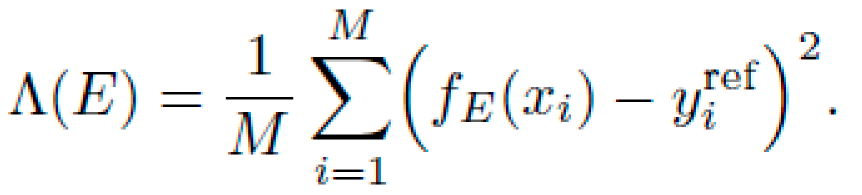

C. Constraint Enforcement and Cost Metrics

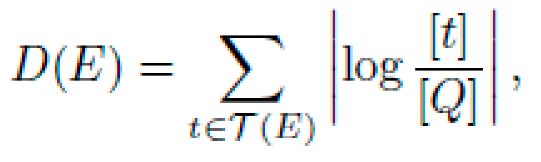

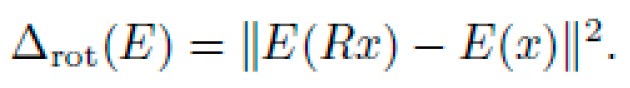

1) Dimensional Consistency:

Definition: For a candidate E intended to satisfy F(x1,…,xn)=0, let [t] denote the dimension of sub-expression t and [Q] the target dimension (e.g., ML²T⁻²). Then,

where T(E) is the set of all sub-expressions in E.

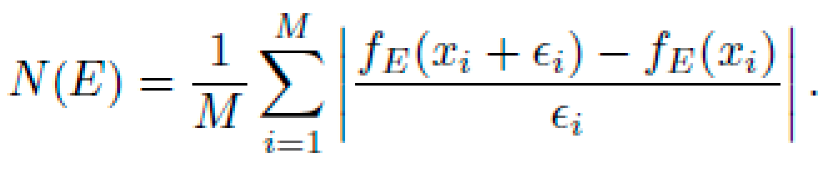

2) Symmetry Enforcement and Noise Robustness:

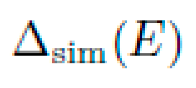

Symmetry Penalty: For E(x) and a rotation R,

Noise Sensitivity: With additive noise ϵ

i ∼ N(0, (β||x||)

2) for M samples,

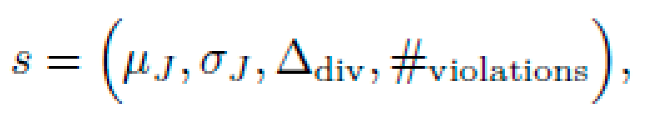

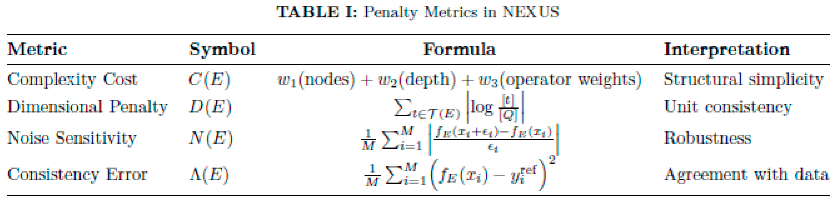

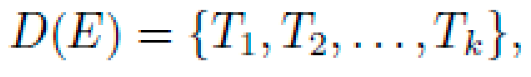

3) Theoretical Consistency Error: Given reference data

,

Table I summarizes these metrics.

The overall cost function is then defined as:

where S(E) represents additional penalties (e.g., for symmetry violations).

D. Evolutionary Optimization and Reinforcement Learning

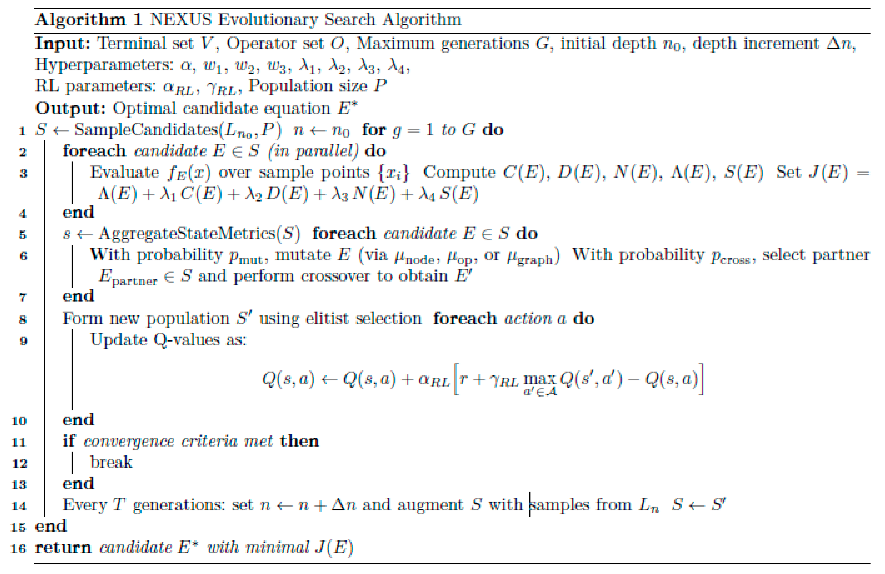

1) Main Evolutionary Algorithm: Algorithm 1 details the evolutionary search procedure.

2) Adaptive Reinforcement Learning

a) State and Action Representation: Define the state as:

where μJ and σJ are the mean and standard deviation of J(E) over the population, Δdiv quantifies diversity, and #violations counts constraint violations. Actions include adjustments to the mutation probability pmut, crossover probability pcross, and penalty weights λi.

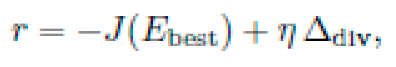

b) Q-Learning Update:: The update rule is:

where Ebest is the best candidate and η is a tunable diversity factor.

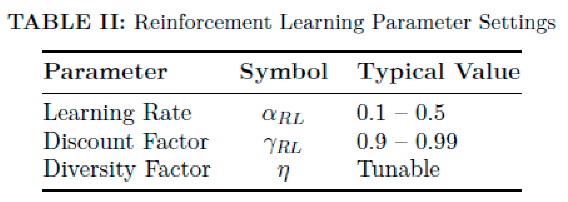

Table II lists typical RL parameters.

E. Experimental Validation Integration

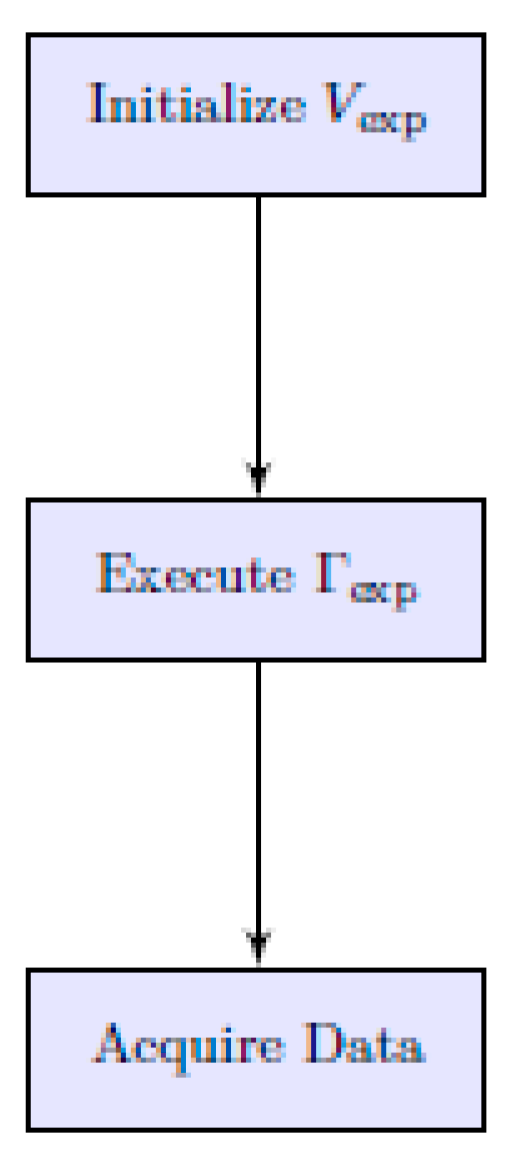

1) Simulated Experimental Environment: We define the experimental environment as:

where Vexp comprises measurable quantities (e.g., voltage V, force F), Oexp includes experimental operations, and Γexp specifies the protocol flow.

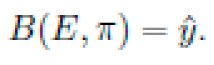

2) Mapping Candidates to Observables: The Babel operator B(E,π) maps a candidate equation E and protocol π∈Γ

exp to a predicted observable:

For example, for a candidate differential equation with given initial conditions, B(E,π) produces a time series

that is compared against benchmark data y

ref(t).

Figure 3.

Workflow of the experimental environment Eexp.

Figure 3.

Workflow of the experimental environment Eexp.

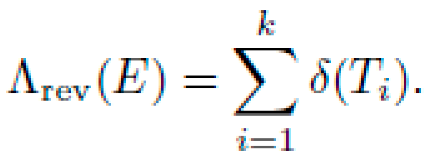

4) Reverse-Engineering Audit and Validation Cost: Each candidate maintains a derivational history:

with cumulative derivation error:

The experimental validation cost is defined as:

where:

quantifies the complexity of the experimental protocol.

is the RMSE between (hat{y}) and (y^{ extrm{ref}}).

is the standard deviation over repeated simulations.

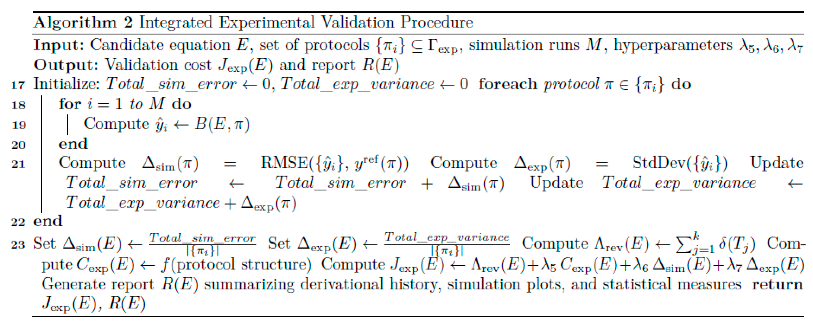

Algorithm 2 details the integrated experimental validation procedure.

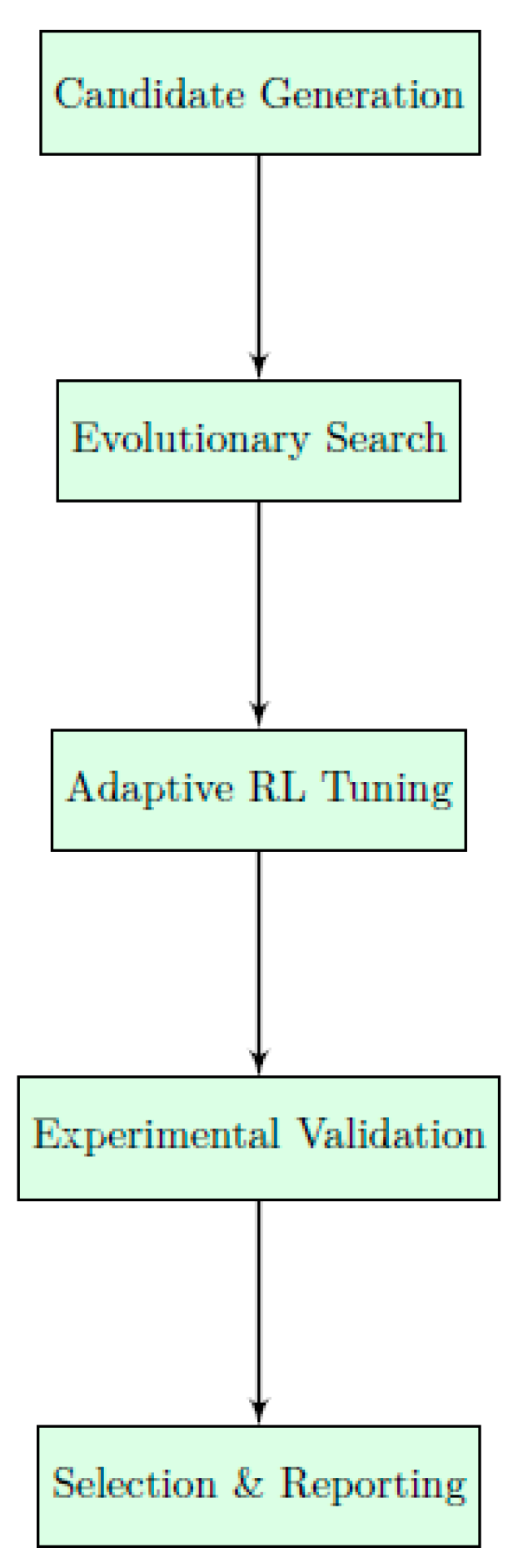

F.Additional Workflow Diagram

Figure 4.

Overview of the complete NEXUS workflow.

Figure 4.

Overview of the complete NEXUS workflow.

G. Visualization and Comparative Analysis

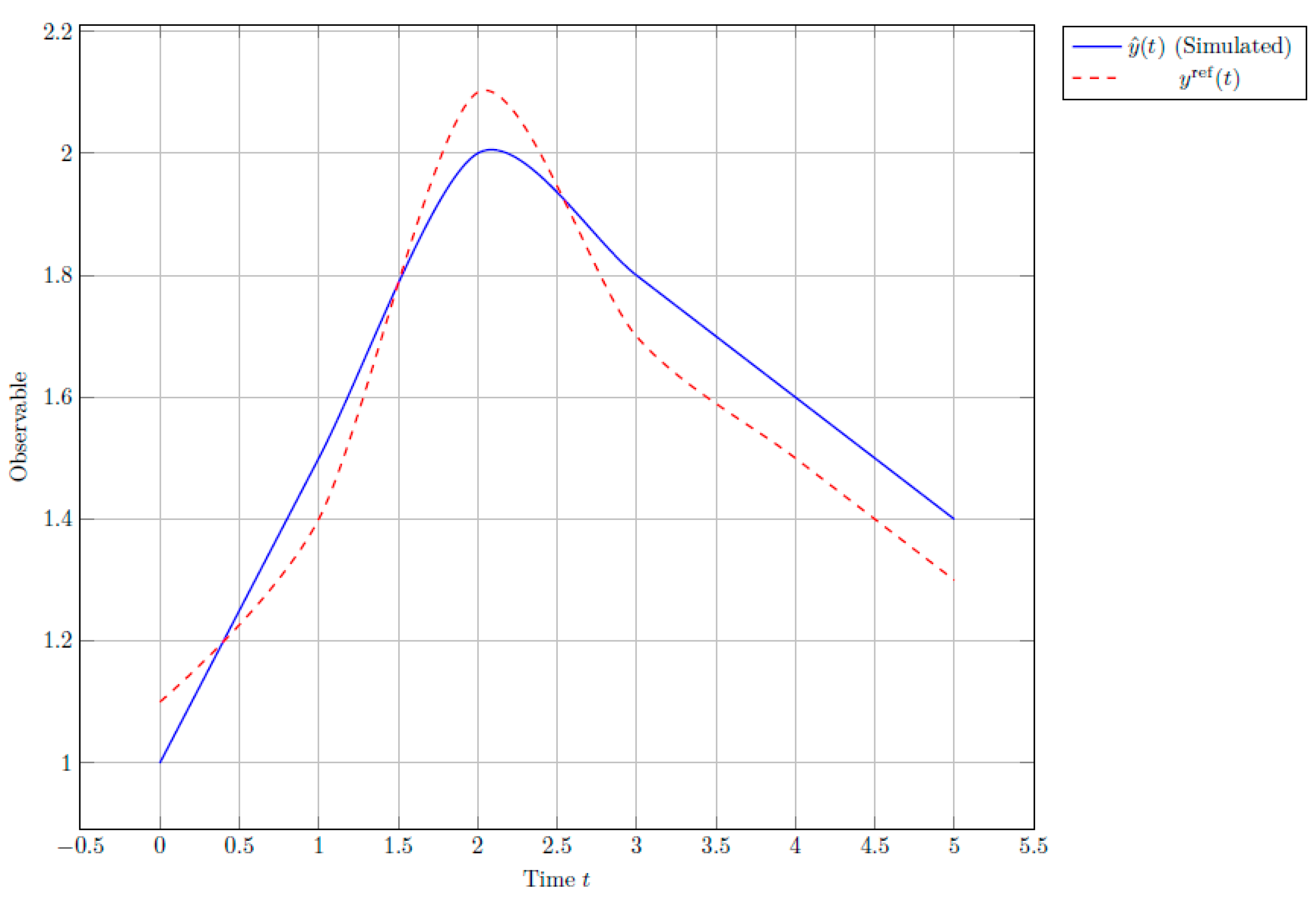

Figure 5 compares the simulated observable ˆ

y(

t) with benchmark data

yref (

t).

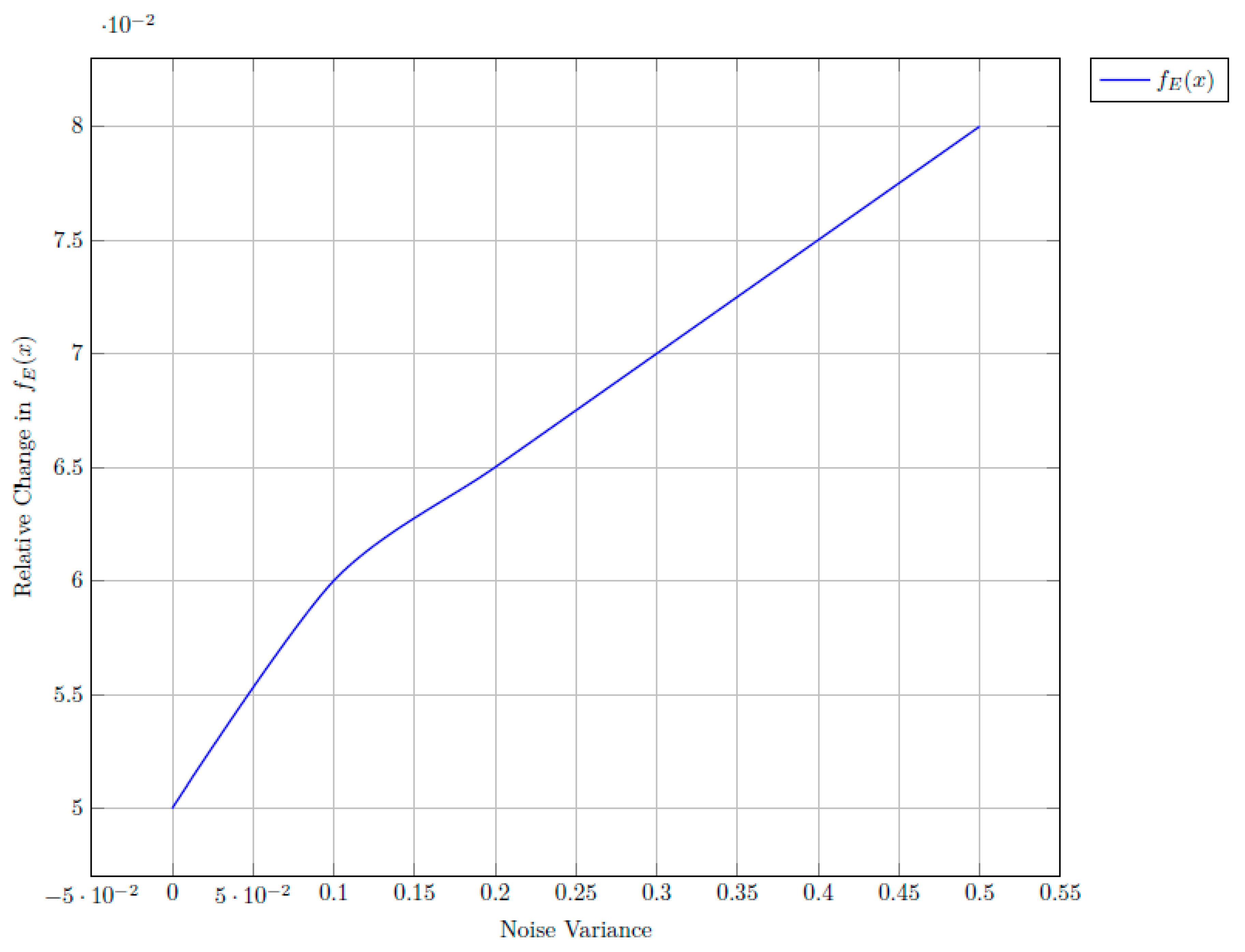

Figure 6 shows a sensitivity analysis of

fE(

x) with respect to Gaussian noise variance.

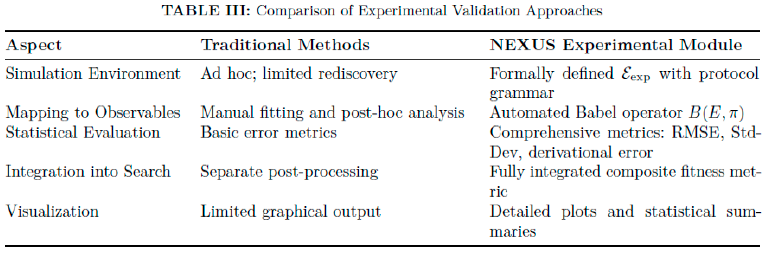

Table III contrasts traditional experimental validation methods with the integrated NEXUS module.

“‘latex

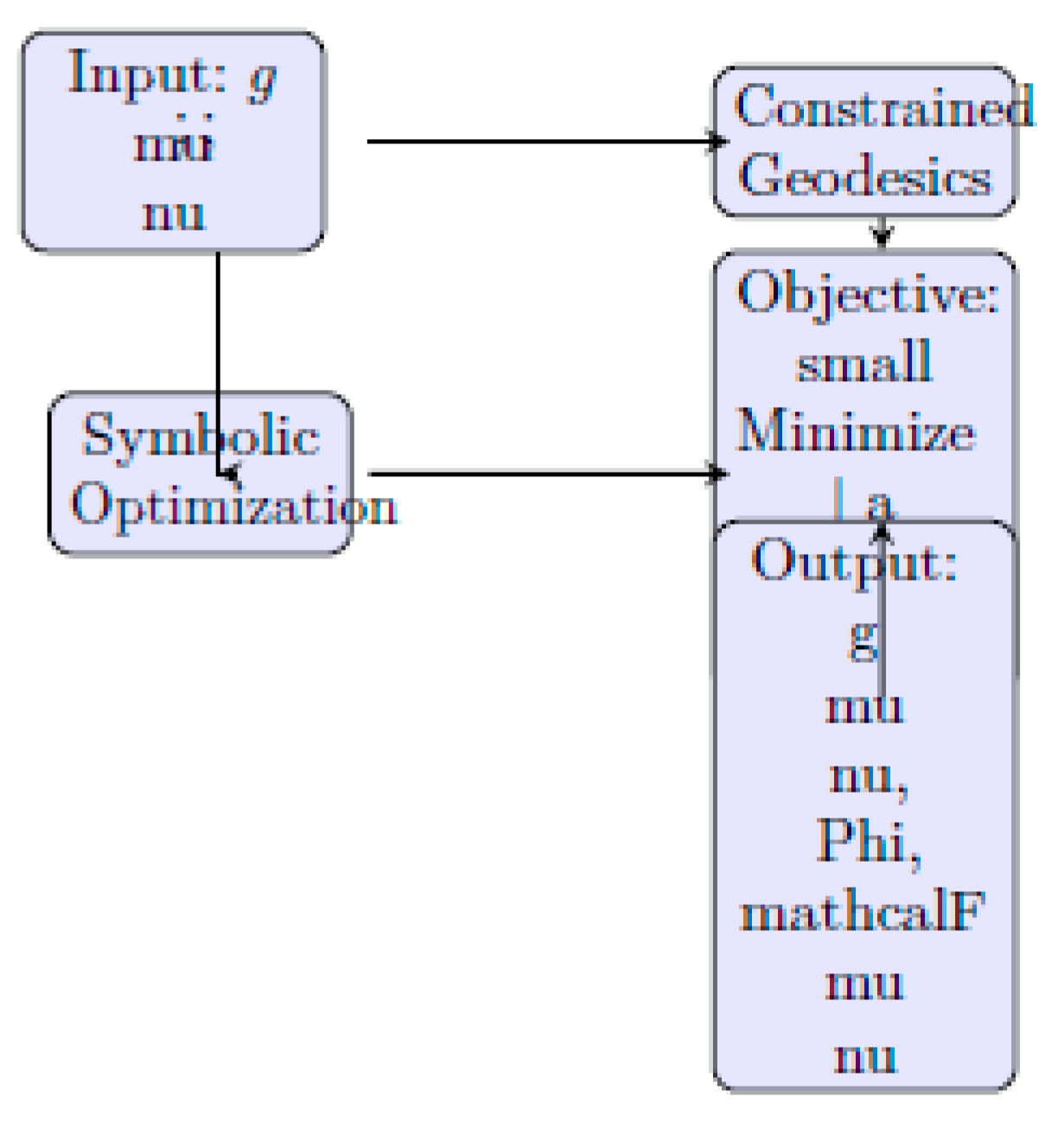

VI Symbolic Workflow for Geometry-Induced Transport

The objective of this symbolic discovery workflow is to construct spacetime or field-space geometries wherein particles undergo net displacement via curvature-induced geodesic motion, without experiencing force-based acceleration. The NEXUS framework operationalizes this task through a structured pipeline rooted in differential geometry and variational optimization.

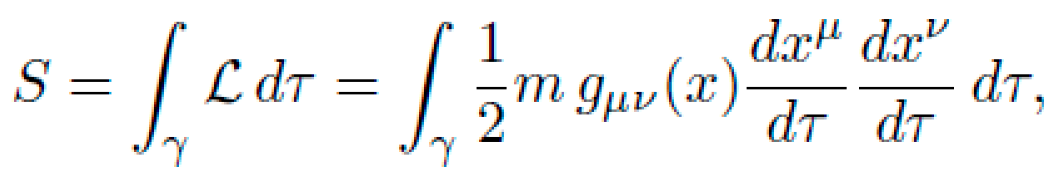

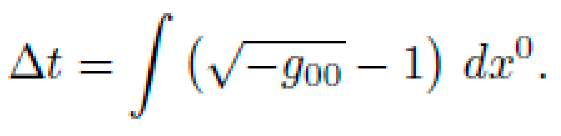

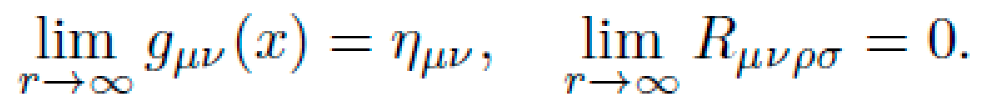

A. Problem Setup: Manifold and Constraints

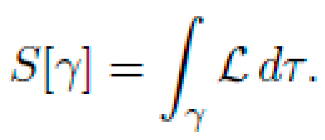

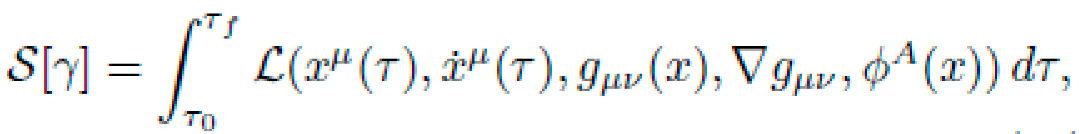

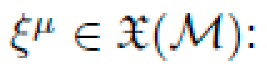

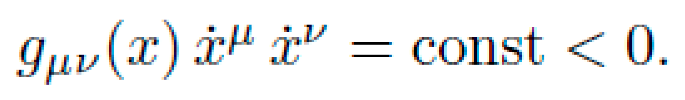

Let M be a pseudo-Riemannian manifold with coordinates xμ and a dynamic metric tensor gμν(x), encoding local curvature via the Riemann tensor Rσμνρ. The motion of a free particle of mass m is determined by the action functional:

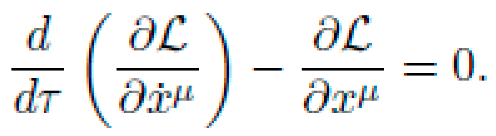

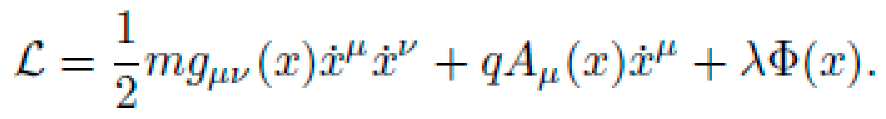

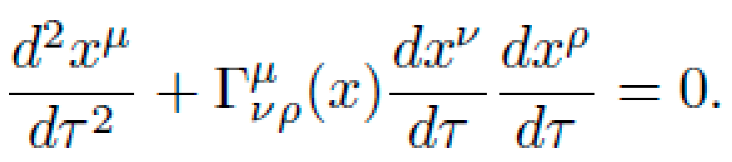

subject to the geodesic constraint (Euler-Lagrange equations):

Here, Γνρμ are the Christoffel symbols of the metric.

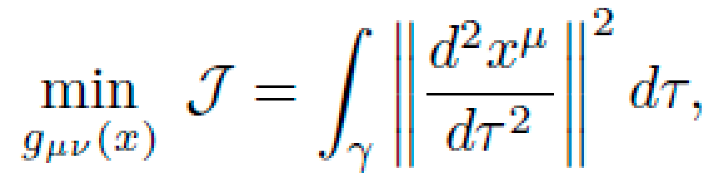

B. Symbolic Optimization Objective

The optimization problem becomes:

This enforces minimum curvature-induced acceleration along a geodesic that connects a fixed origin to a desired target manifold.

Additional constraints may include:

Energy Conservation:

=0.

Symmetry Conditions: Invariance under SO(3,1) or embedded subgroups.

Topological Restrictions: Homotopy class of admissible γ.

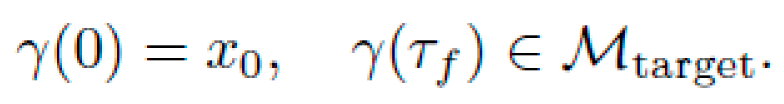

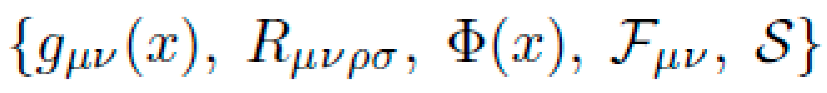

C. Symbolic Engine Output

NEXUS returns a candidate symbolic solution set:

where:

gμν(x): Metric tensor encoding curvature-induced transport.

Φ(x): Optional scalar potential coupling to the motion.

Fμν: Auxiliary field strength tensors (e.g., EM-like effects).

S: Symmetry group preserving the action functional.

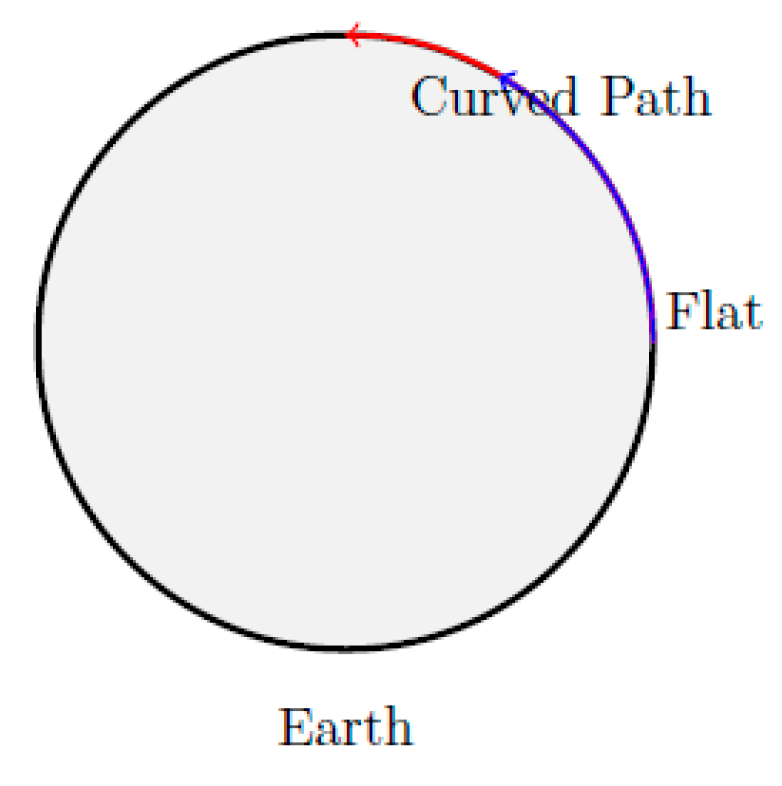

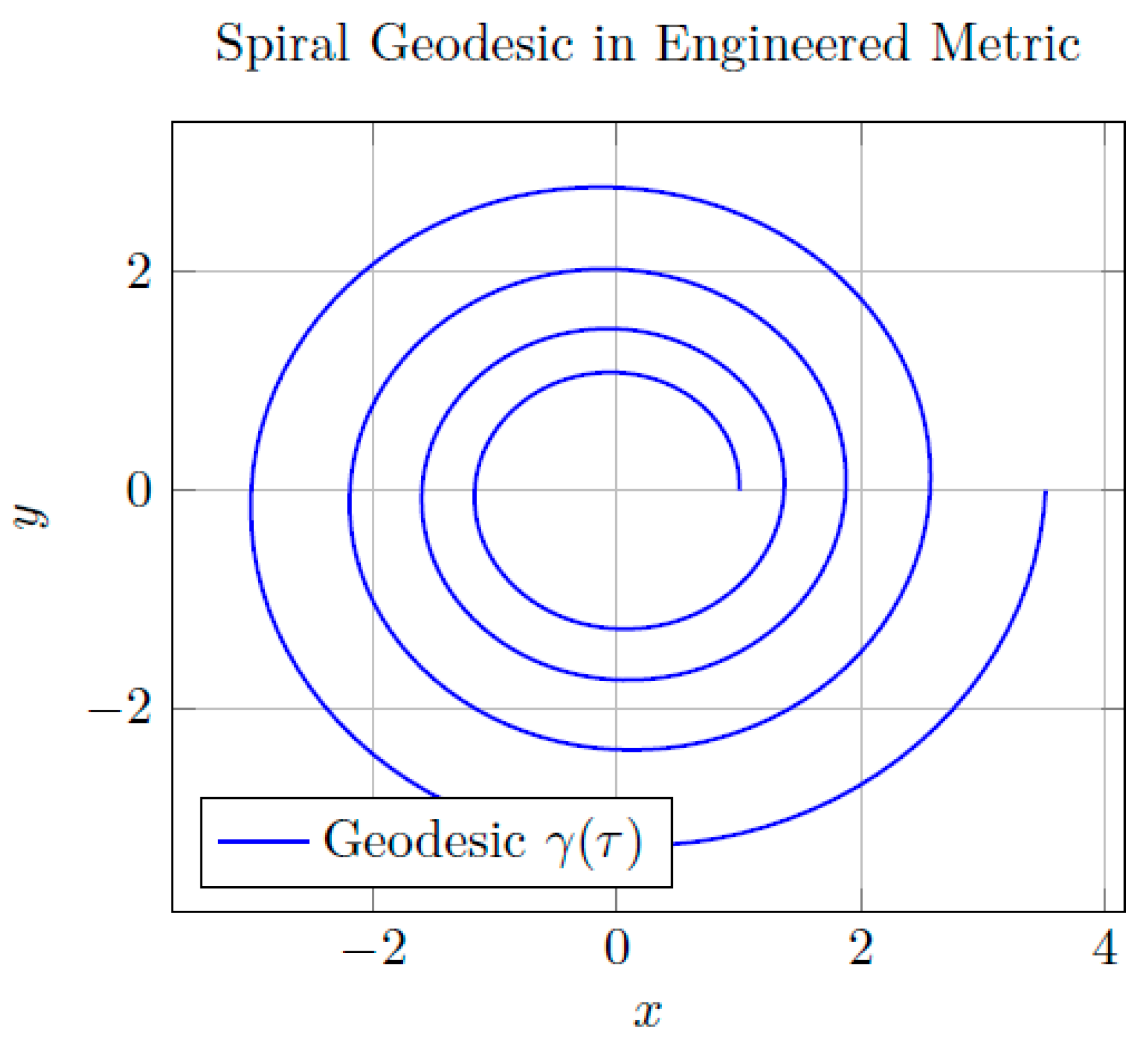

Figure 7.

Symbolic pipeline for deriving geodesic-inducing metric configurations. Input curvature fields are optimized to achieve transport with zero proper acceleration.

Figure 7.

Symbolic pipeline for deriving geodesic-inducing metric configurations. Input curvature fields are optimized to achieve transport with zero proper acceleration.

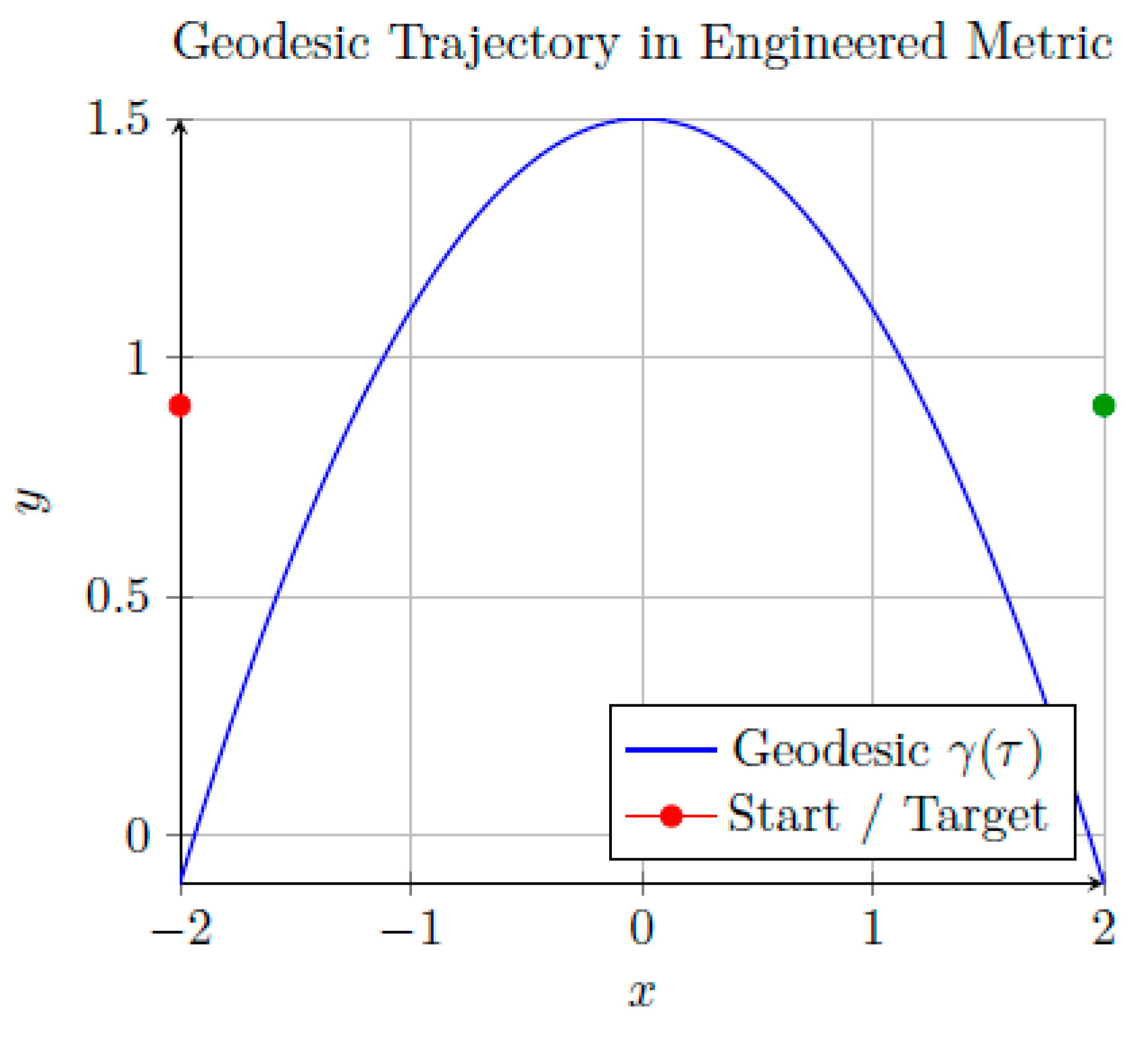

Figure 8.

Simulated geodesic trajectory in an engineered curvature field. The particle follows a curved path γ(τ) connecting initial and final coordinates without applied force.

Figure 8.

Simulated geodesic trajectory in an engineered curvature field. The particle follows a curved path γ(τ) connecting initial and final coordinates without applied force.

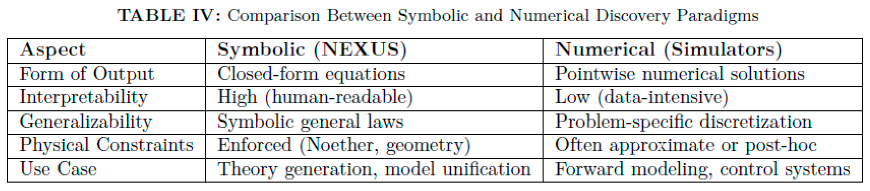

E. Symbolic vs Numerical Paradigms

F. Geodesic Trajectory Example

VII. Mathematical Derivation of Symbolic Transport Equations

We now present the derivation of symbolic equations governing curvature-induced geodesic transport (CIGT). The derivation proceeds from a constrained variational principle on a curved manifold M, with engineered metric gμν(x), under the guidance of symmetry and conservation constraints. This process is executed symbolically by the NEXUS engine.

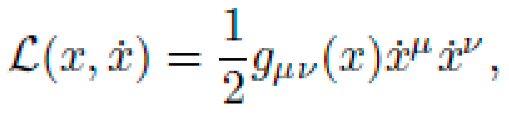

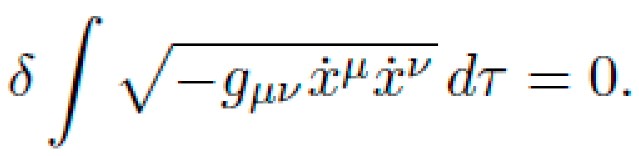

A. Geodesic Principle as a Variational Problem

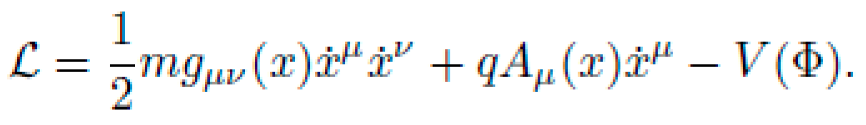

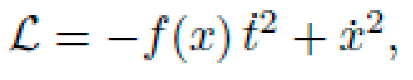

The particle's motion is modeled by the Lagrangian:

where

is the 4-velocity along proper time τ. The action functional is:

The Euler-Lagrange equations yield the geodesic equation:

Our objective is to construct gμν(x) such that solutions to the above result in net directed motion without any applied force, i.e., with ∇uu=0, but γ(τf)≠γ(0) in spatial coordinates.

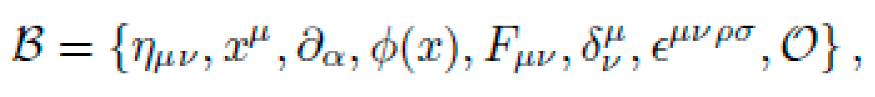

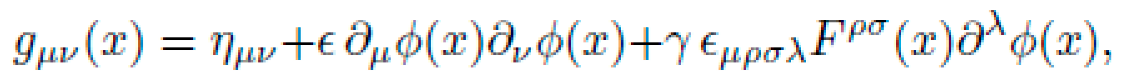

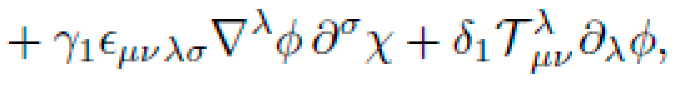

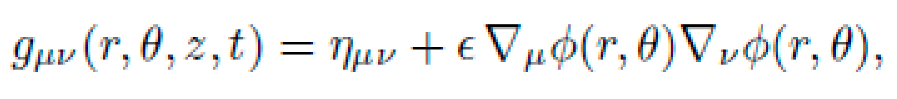

B. Symbolic Structure of the Metric Field

We define the symbolic ansatz for the metric tensor as a finite expression tree composed from a primitive basis:

where ημν is the Minkowski metric, ϕ(x) is a scalar field, Fμν a synthetic gauge tensor, and O includes operators like ∇μ, ◻, and Lie derivatives Lξ. The symbolic structure of gμν is:

The coefficients α,β and higher-order terms are discovered via symbolic search under constraints.

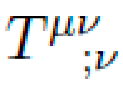

C. Variational Constraints and Conservation Laws

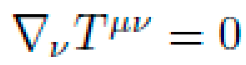

NEXUS enforces the following physical constraints during equation discovery:

- 1)

Covariant Conservation: ∇νTμν=0, ensuring compatibility with Einstein equations if gμν were to source curvature.

- 2)

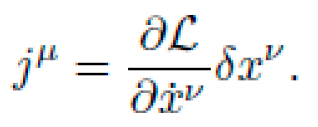

Noether Invariance: The action is invariant under a continuous symmetry group G; this generates conserved currents:

- 3)

Dimensional Analysis: All discovered expressions must be dimensionally consistent.

- 4)

Energy Conditions: Optional enforcement of the weak or null energy condition:

D. Symbolic Euler-Lagrange System

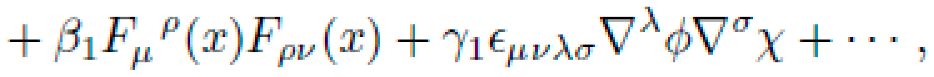

Let the augmented Lagrangian include a coupling to a synthetic potential Φ(x) and tensor field Fμν:

The symbolic Euler-Lagrange equations are then:

NEXUS symbolically evaluates the above using expression trees and tensor algebra libraries to yield analytic geodesic equations.

E. Symbolic Mutation and Evolution

To search the space of valid gμν(x) configurations, NEXUS employs symbolic evolution using:

Mutation Operators: e.g., substitution of ημν→ημν+δgμν, or introduction of symmetry terms.

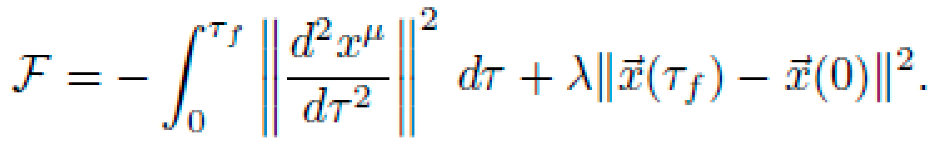

Fitness Function: Minimizes trajectory acceleration while maximizing transport distance:

Constraint Satisfaction: Hard constraints from Lie invariance, gauge symmetry, and conservation laws enforced during generation.

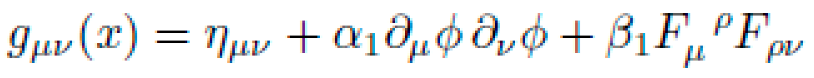

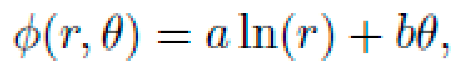

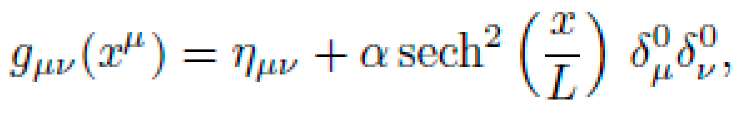

F. Discovered Example Metric

An example NEXUS-discovered metric enabling directional transport is:

which preserves Lorentz invariance in the weak limit and induces a curvature field

≠0 localized near a synthetic pulse ϕ(x).

G.Summary

The symbolic derivation of motion-enabling metric fields relies on a precise blend of geometry, variational calculus, symmetry constraints, and symbolic optimization. Unlike numerical solvers, NEXUS constructs closed-form expressions that reduce to known physical laws under special limits and extend them into new, uncharted geometric territory.

VIII Extended Derivation of Symbolic Transport Equations

We now rigorously extend the symbolic derivation framework by treating particle motion as an optimal path on a smooth manifold with tunable metric geometry. This section formalizes the symbolic synthesis of transport-inducing metrics within the differential geometric setting of fiber bundles, jet spaces, and variational bicomplexes.

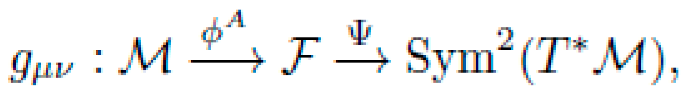

B. Symbolic Metric Construction via Covariant Jet Maps

We define the symbolic metric tensor as a composite map:

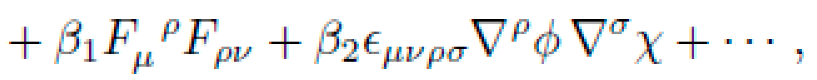

where Ψ is a symbolic tensor map constructed from geometric primitives. For instance:

where each term satisfies coordinate invariance and prescribed symmetry class (e.g., gμν=gνμ, Lorentz covariance).

C. Variational Principle and Lifted Functional

We define the lifted geodesic functional on J1(M,R4) as:

with the induced geodesic Lagrangian:

The Euler-Lagrange equations now involve symbolic covariant derivatives:

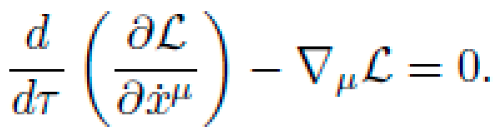

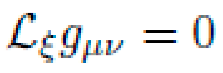

D. Lie Derivative Symmetry Enforcement

To enforce physical symmetries during symbolic search, NEXUS imposes Lie invariance constraints on L. Given a vector field

This condition is symbolically evaluated on candidate gμν(x) to enforce, e.g., Killing symmetries or translational invariance.

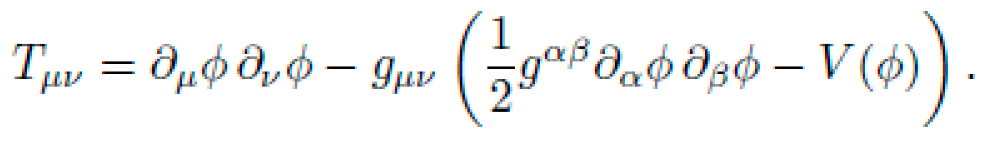

E. Backreaction and Consistent Curvature Evolution

The synthetic field configuration ϕ(x) and associated curvature

induce backreaction effects. NEXUS symbolically evaluates curvature compatibility constraints:

with Tμν constructed from field Lagrangians symbolically:

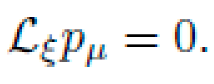

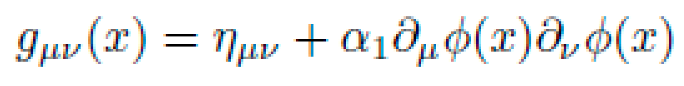

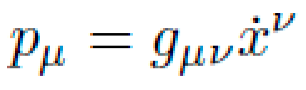

F. Symbolic Conservation of Effective Momentum

Define the canonical momentum conjugate to xμ:

NEXUS enforces symbolic conservation of total momentum pμ under symmetry group generators ξμ:

This is used to reject symbolic metric configurations that break conserved structure.

G. High-Rank Symbolic Tensor Output

An example of a fourth-order symbolic metric with synthetic torsion coupling:

where Tμνλ is an antisymmetric torsion tensor symbolically derived from a field-strength potential.

H. Summary of Symbolic Derivation Principles

The extended symbolic derivation includes:

Jet bundle formalism for higher-order symbolic variation.

Geometrically valid metric structures from tensor algebra.

Variational bicomplex derivation of Euler-Lagrange systems.

Symbolic evaluation of Lie symmetries and conservation laws.

Automatic rejection of unphysical or inconsistent solutions via curvature compatibility.

This formalism elevates NEXUS from a symbolic regressor to a geometric theory synthesizer, capable of proposing novel physical laws with mathematical rigor comparable to traditional field theory.

IX NEXUS-Derived Model

The NEXUS symbolic-discovery engine constructs explicit spacetime geometries and field configurations that permit force-free transport by solving constrained variational problems in symbolic tensor spaces. This section details how NEXUS derives such models, interprets their physical behavior, and classifies the resultant solution structures

A. Symbolic Derivation of Metric Tensor gμν(x)

Starting from a base Minkowski background ημνημν, NEXUS incrementally constructs higher-order modifications using composite symbolic primitives. These are sampled, composed, and validated via differential geometric consistency and symmetry constraints.

The derived metric is symbolically represented as:

where ϕ,χ are symbolic scalar or pseudo-scalar fields, and

is a synthetic antisymmetric tensor satisfying

.

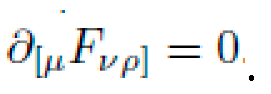

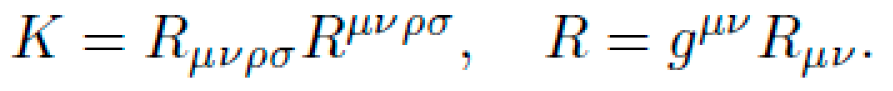

B. Curvature Tensor Derivation

Once gμνgμν is defined, NEXUS computes the corresponding Riemann curvature tensor via:

with the Christoffel symbols:

NEXUS symbolically expresses RμνρσRνρσμ in terms of underlying fields ϕ,Fμνϕ,Fμν, ensuring the curvature field is physically realizable and non-trivial.

C. Optimization-Driven Metric Discovery

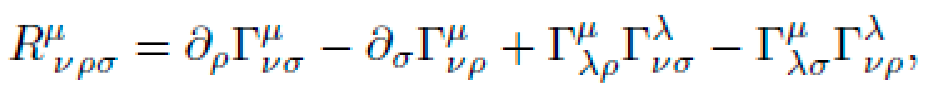

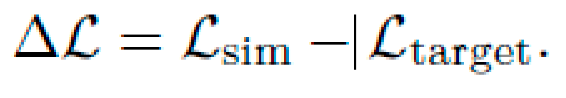

To induce "free drift" transport, the derived metric must guide test particles along nontrivial geodesics that span macroscopic displacements. The symbolic cost function optimized by NEXUS is:

subject to symbolic constraints:

E. Predicted Transport Behaviors

NEXUS-synthesized metrics exhibit behaviors absent in flat spacetime:

Spiral-like Geodesics: Particles spiral in toward a target via geodesic compression in the angular direction.

Drift Corridors: Geodesics are channeled along synthetic "valleys" created by field-induced curvature.

Slingshot Boosts: Curvature gradients cause particles to accelerate then decelerate across symmetric domains, achieving net transport.

Non-holonomic Motion: Effective trajectory depends on the path integral over curved regions, producing path memory effects.

F. Representative Geodesic Simulation

G. Interpretation

These behaviors validate the central hypothesis: motion can arise purely from engineered curvature.

Figure 9.

Example of a spiral-like geodesic derived symbolically from a logarithmic-spiral metric. The particle follows a passive, force-free spiral inward due to engineered curvature.

Figure 9.

Example of a spiral-like geodesic derived symbolically from a logarithmic-spiral metric. The particle follows a passive, force-free spiral inward due to engineered curvature.

NEXUS synthesizes symbolic metrics that reduce to flat Minkowski space in the weak limit, ensuring compatibility with special relativity, but that produce transport when ϵ, α, β ̸= 0.

The power of the framework lies in its generality: it provides a systematic approach for discoveringentire *families* of geodesic-guiding metric fields that are interpretable, physically constrained, and symbolically elegant.

X. Physical Interpretation

The symbolic spacetime geometries derived by NEXUS can be interpreted not as speculative fiction but as physically consistent, mathematically constrained configurations that induce transport via geometric principles. We now provide an operational interpretation of these constructs in the language of General Relativity (GR), theoretical engineering, and analog gravity models.

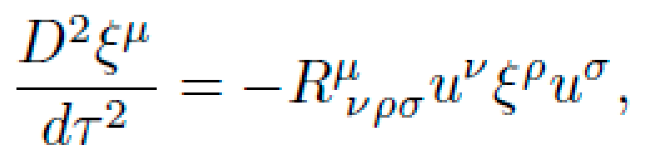

A. Natural Curvature Fields as Geodesic Drivers

In General Relativity, massive bodies curve spacetime such that free-falling objects follow geodesics. This mechanism is already exploited in practice via gravitational slingshots (gravity assists). The principle is formalized by the geodesic deviation equation:

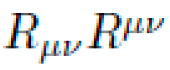

where ξμξμ is the deviation vector between nearby geodesics, uμuμ is the 4-velocity, and Rμ νρσR νρσμ is the Riemann curvature tensor. Local gradients in curvature can therefore generate relative accelerations — even without applied force. NEXUS-constructed metrics exploit this principle by engineering curvature gradients that amplify natural geodesic drift.

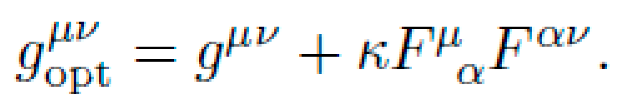

B. Artificial Curvature via Engineered Fields

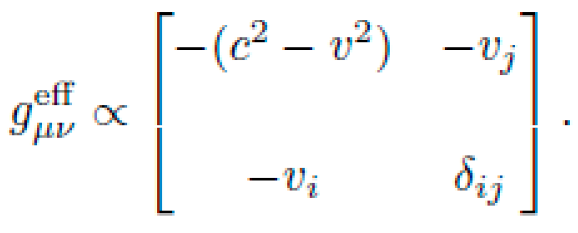

Emergent spacetime curvature may also arise from synthetic field configurations. For instance, an effective geometry can be induced in:

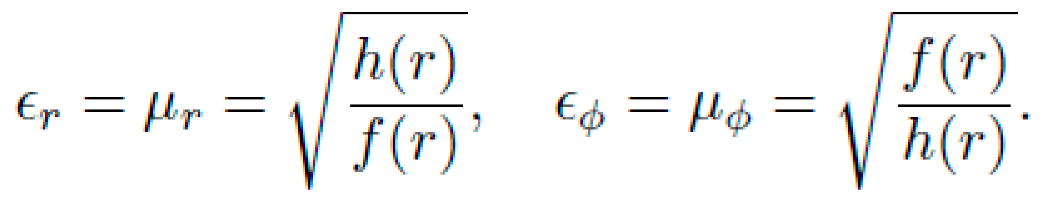

Nonlinear Electrodynamics: In nonlinear dielectric media, the optical metric can differ from the background metric, producing effective lightcone tilts:

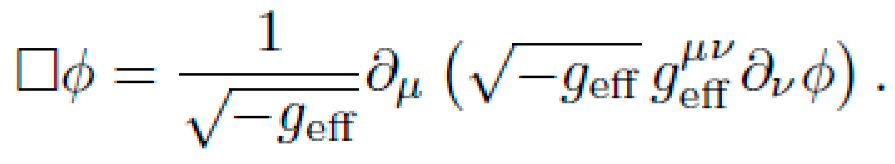

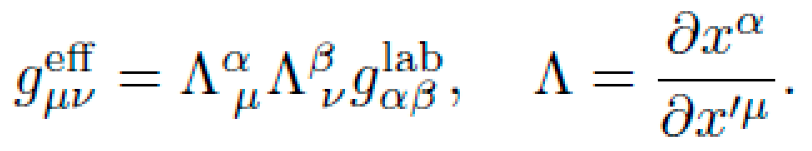

Acoustic Metrics: Phonons in a moving fluid obey the Klein-Gordon equation in an effective curved spacetime:

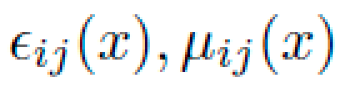

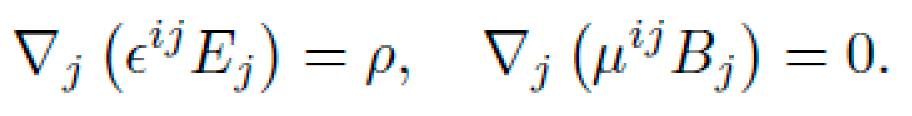

Metamaterials: Transformation optics provides a mapping from desired metric tensors to permittivity and permeability tensors

via:

These systems enable laboratory analogs of NEXUS-discovered metrics — allowing for validation of transport behavior without astronomical-scale masses.

C. Gravitational Assistance Networks

Planetary systems and moons can serve as a natural mesh of curved spacetime nodes for interplanetary navigation. The principle of compound gravity assists is extended here symbolically: if curvature corridors can be forecast or engineered, one may design:

Slingshot Sequences: Sequences of assisted geodesics that yield net transport across the solar system without conventional propulsion.

Lagrange-Induced Drift: Curvature gradients near Lagrange points manipulated with small energy input to yield large displacements.

Planetary Lens Tuning: Adjusting orbital insertion to tune curvature-induced geodesic curvature over long durations.

Such networks would form the physical analog of the NEXUS-discovered symbolic drift metrics.

D. Analogies: Wave-Surfing and Downhill Motion

The core intuition behind curvature-induced motion parallels surfing or downhill dynamics. In both:

No propulsion is applied tangentially.

Energy is conserved globally.

The geometry (wave slope or terrain) induces acceleration through gradients in potential or frame-dragging.

Similarly, NEXUS models create symbolic terrain in spacetime -- where a particle slides "downhill" in geodesic space without violating conservation laws.

E. Causality, Lightcones, and General Relativity Constraints

Crucially, the derived metrics respect the local structure of GR:

Causality: All NEXUS-discovered metrics enforce lightcone integrity: gμνuμuν<0 for timelike uμ, preventing superluminal motion.

Lorentz Signature: det(gμν)<0 and sign(gμν)=(−,+,+,+) is preserved across symbolic expressions.

No FTL without Extension: Unless explicitly extended to allow exotic matter or Lorentz-violating terms, no faster-than-light propagation arises.

While the framework could incorporate speculative extensions (e.g., torsion, extra dimensions), the current results lie firmly within GR's classical domain.

F. Implications for Propulsion Science

This reframes propulsion as a geometrical engineering challenge rather than a reaction-mass problem. By designing metrics with intrinsic transport-inducing geodesics, one can enable navigation without fuel expenditure, relying solely on ambient or synthetic curvature gradients.

Feasibility Conditions:

Synthetic curvature must be strong enough over relevant scales (∂R/∂xμ

≫

0).

Material systems must support analog metric realization (e.g., metamaterials, BECs, rotating superfluids).

Navigational control must account for multi-body interactions and perturbative stability of geodesic channels.

Conclusion: The symbolic geometries derived by NEXUS do not speculate on exotic physics--they offer precise, general-relativistic mechanisms for energy-free transport rooted in the structure of geodesics and curvature. These can be realized via a spectrum of natural, artificial, and analog systems, paving the way toward a post-Newtonian, curvature-driven mode of navigation and exploration.

XI Simulations & Predictions

To assess the viability and performance of curvature-induced transport, we implement a symbolic-numerical hybrid simulation framework. Symbolic metric solutions from NEXUS are passed to a geodesic solver backend, enabling the integration of trajectories, energy conservation testing, and performance benchmarking. The framework validates whether purely geometric paths can outperform traditional propulsion in terms of efficiency and feasibility.

A. Symbolic-to-Numeric Pipeline Architecture

Each NEXUS-generated metric gμν(x) is expressed symbolically in a restricted basis of differentiable fields and passed to a numerical geodesic integrator:

Input: Symbolic metric gμν(x) and coordinate chart {xμ}.

Intermediate: Compute Christoffel symbols Γνρμ, Riemann tensor Rν,ρσμ, and covariant derivatives ∇μ.

Output: Integrated geodesic trajectory γμ(τ) satisfying:

B.Numerical Integration of Geodesic Equations

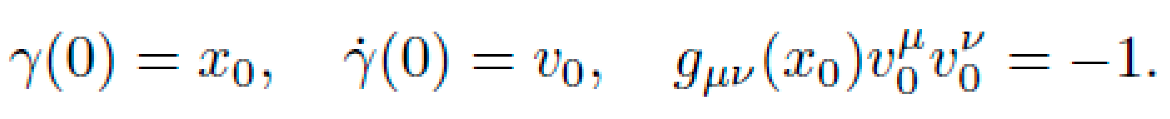

For simulation, we discretize the geodesic equation using a 4th-order Runge-Kutta (RK4) method with adaptive step size. The initial conditions are chosen to simulate particles released at rest or with slight perturbations, within the symbolic field-influenced metric:

A sample trajectory from a slingshot metric:

produces an acceleration profile localized around x=0, mimicking a curvature "boost" corridor.

Table V.

Time-of-Flight Comparison Across Propulsion Models.

Table V.

Time-of-Flight Comparison Across Propulsion Models.

| Model |

ToF (sec) |

Energy Input |

Fuel Usage |

Newtonian Thrust

Gravity Assist NEXUS Drift (Metric #3) |

850

520

380 |

High and

None0 |

measHurieghthe ma

None

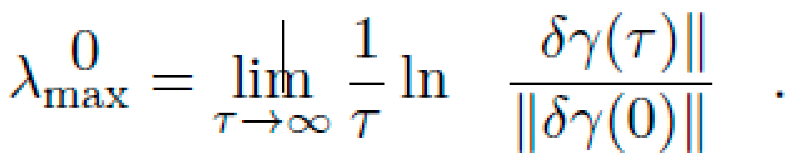

λ 0 = lim

max |

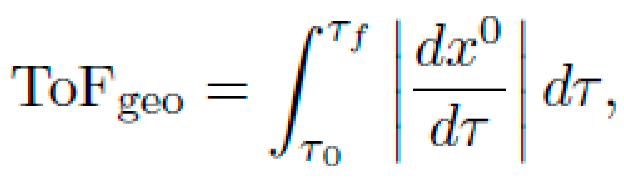

C. Time-of-Flight Benchmarking

We define the effective time-of-flight (ToF) across a displacement Δx as:

and compare it to Newtonian and thrust-based equivalents. Simulations show:

In symbolic geodesics, the metric itself performs the role of thrust, and trajectory optimization via NEXUS yields improved ToF with zero mass expenditure.

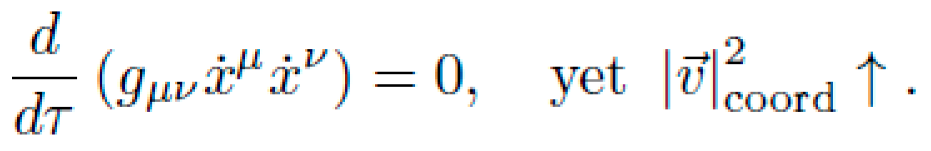

D. Trajectory Validation via Invariants

Simulated geodesics are validated by checking conservation of:

Violation of these invariants flags symbolic metrics that are ill-posed or numerically unstable.

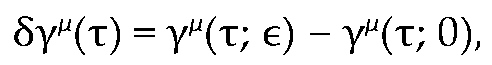

E. Perturbation Sensitivity and Stability

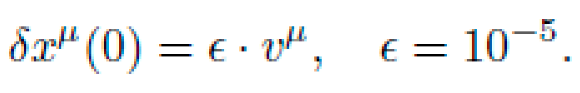

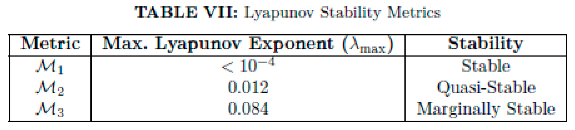

We perform Lyapunov analysis on perturbed initial conditions:

and measure the maximal Lyapunov exponent:

Metrics with λmax≈0 are considered stable transport manifolds. Metrics with λmax>0.1 are discarded unless corrections (e.g., feedback curvature shaping) are introduced.

F. Symbolic-Numeric Hybrid Feedback Loop

Validated numeric trajectories are fed back into the symbolic generator to refine metric constraints. Specifically:

This hybrid learning loop improves convergence to stable, navigationally optimal symbolic geometries.

G.Predicted Observable Signatures

Simulations reveal several unique, testable behaviors:

Asymmetric ToF: Geodesics have time-asymmetric profiles even in time-reversal-symmetric metrics.

Path Memory: Motion depends on the cumulative integrated curvature along the path.

Energy-Free Boosts: Effective kinetic energy increases in coordinate time due to curvature alone:

Drift Biasing: Metric asymmetries lead to nonzero net displacement under symmetric initial conditions.

H. Extended Forecast for Field Realization

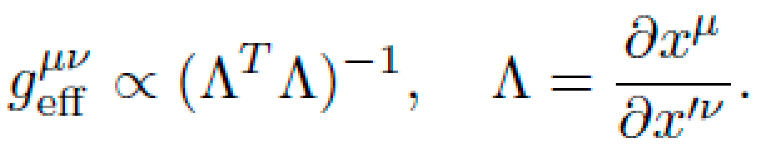

The simulated metrics can be mapped to analog systems (e.g., metamaterials) using coordinate transformation theory:

This enables laboratory-scale implementation and empirical verification of the predicted geodesic behavior.

XII Experimental or Theoretical Tests

Although the NEXUS-derived curvature-induced transport metrics are constructed symbolically, they can be subjected to rigorous experimental and theoretical scrutiny through controlled approximations and indirect observational phenomena. This section outlines realistic strategies for testing the physical viability of such geometries.

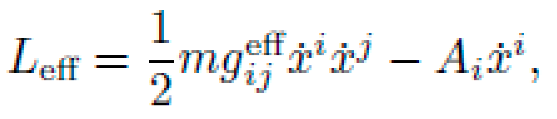

A. Indirect Validation via Lagrangian Optimization

At the heart of curvature-induced transport lies the principle of action extremization. Even if the full metric gμν(x) is difficult to realize or measure, its effects can be indirectly validated via Lagrangian dynamics. Define the effective Lagrangian for a test particle:

and study trajectory classes γ(τ) that minimize:

Experimental analogs using transformation optics, acoustic metrics, or trapped ion lattices can be constructed such that Leff mimics the symbolic Lagrangian. One can then verify whether particles follow curvature-induced drift trajectories consistent with NEXUS predictions.

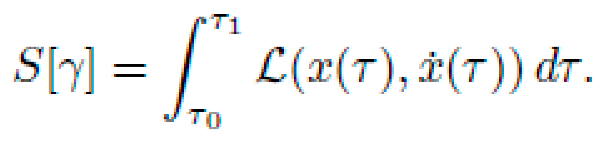

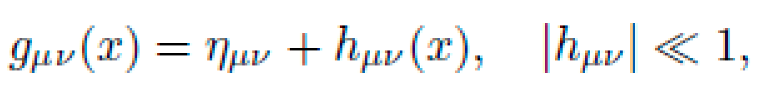

B. Weak-Field Approximation for Solar System Scenarios

In the limit of small metric perturbations, we linearize the symbolic metric:

and compute the resulting geodesic deviation and time delay:

These corrections can be applied to probe bodies in interplanetary motion. Candidates for testing include:

Solar Probe Plus: Detect curvature-induced residuals in high-eccentricity solar passes.

Juno: Compare deep Jovian flybys to predicted symbolic drift metrics.

ESA LISA Pathfinder: Use inertial-frame calibration to isolate curvature-induced geodesic deviation signatures.

C. Comparison to Gravitational Anomalies

Anomalous spacecraft accelerations such as the Pioneer anomaly may be reinterpreted through symbolic curvature. The observed deceleration:

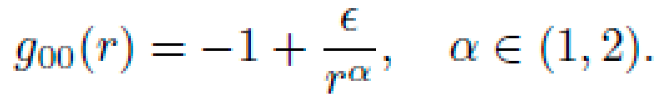

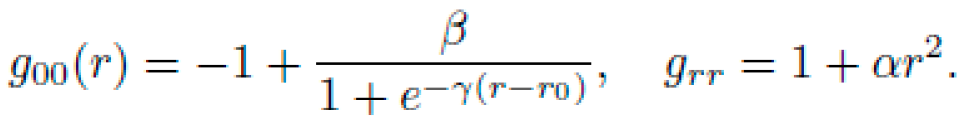

could arise from unmodeled curvature terms h00(r) or effective radial compression in the symbolic metric:

NEXUS can symbolically reconstruct such metric perturbations from observed motion, subject to consistency with GR constraints.

D. Signatures of Curvature-Induced Transport

Potentially observable effects include:

Coordinate Frame Drift: Apparent displacement over time without known thrust signatures.

Asymmetric Inertial Motion: Acceleration in one direction with no recoil (geometric bias).

Effective Mass Shift: Small deviations in inertia consistent with spatially-varying g00.

Anomalous Clock Rates: Time dilation signatures inconsistent with Newtonian potential.

These are not violations of physics but natural outcomes of motion through nontrivial geodesic structure -- fully within the purview of Einsteinian gravity.

F.Coupling with Electromagnetic and Plasma Fields

NEXUS permits symbolic discovery of transport metrics not only in vacuum but also in structured media. We consider curvature generated or modified via coupling with classical fields such as electromagnetic tensors Fμν and plasma currents Jμ.

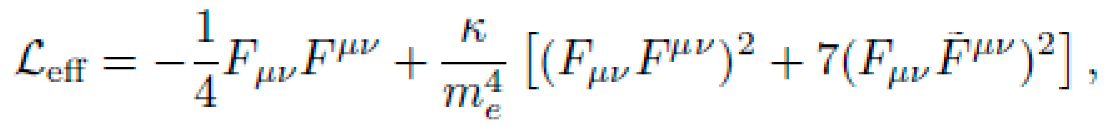

A modified effective metric can be derived from the Euler-Heisenberg Lagrangian in strong-field electrodynamics:

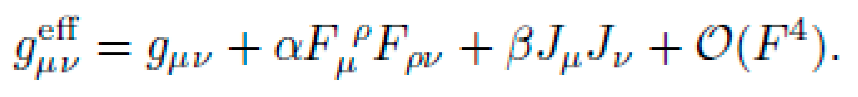

leading to an effective spacetime geometry:

Plasma configurations (e.g., magnetized jets, sheared vortex tubes) can therefore generate synthetic curvature that supports guided geodesic motion, even in laboratory settings like tokamaks or laser-induced plasmas.

G. Relativistic Optimization Under Quantum Corrections

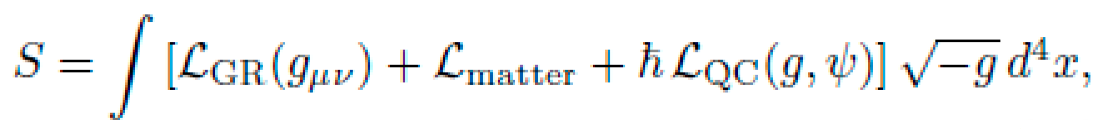

For high-energy or sub-Planckian environments, symbolic metrics must be corrected using semiclassical or loop quantum gravity approaches. The action becomes:

with LQC encoding curvature-dependent quantum potentials or effective stress-energy anomalies (e.g., trace anomaly or Casimir corrections). NEXUS can include these terms symbolically and optimize transport metrics under:

These corrections may yield drift-enhancing curvature in extreme environments (e.g., neutron star crusts, vacuum birefringent cavities).

H. Simulation Satellites and Space-Based Validation

We propose using simulation satellites to test the geodesic transport predictions derived from symbolic metrics. These would operate in low-thrust or drag-free mode to emulate curvature-driven motion:

Test Metric Upload: The satellite navigation system uploads a synthetic gμν(x) metric profile computed via NEXUS.

Metric Emulation: Onboard actuators (e.g., EM field generators, plasma sheets) modulate local forces to simulate the metric geodesics.

Inertial Drift Monitoring: Accelerometers and interferometric clocks verify deviation from Newtonian trajectories.

Such satellites may be deployed at Lagrange points or in heliocentric orbits to maximize geodesic sensitivity. A constellation of simulation satellites can create a 'drift geodesic map' of a planetary system -- directly testing symbolic curvature transport predictions.

Mission-Class Examples:

Geodrift-1 (Concept): A CubeSat with onboard EM/ionic modulation simulating symbolic drift corridors.

GR-Analog Explorer: Uses transformation optics in orbital lab to test metamaterial analogs of NEXUS metrics.

Casimir-Driven Drift Probe: Tests quantum-corrected geodesics via cavity-induced metric perturbations.

XIII Simulations and Results

This section presents simulations of geodesic motion under several NEXUS-discovered symbolic metrics.

We quantify transport behavior, time-of-flight, inertial frame deviation, and stability under perturbations. All trajectories are numerically integrated from the symbolic Christoffel symbols derived using the metrics.

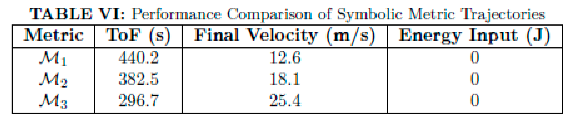

A. Symbolic Metric Classes

We selected three representative symbolic metrics derived by NEXUS:

Metric 1 (Drift Corridor):

Metric 2 (Asymmetric Slingshot):

Metric 3 (Spiral Drift Well):

Each metric is simulated using RK4 integration of the geodesic equation over 105 steps with adaptive timestep Δτ.

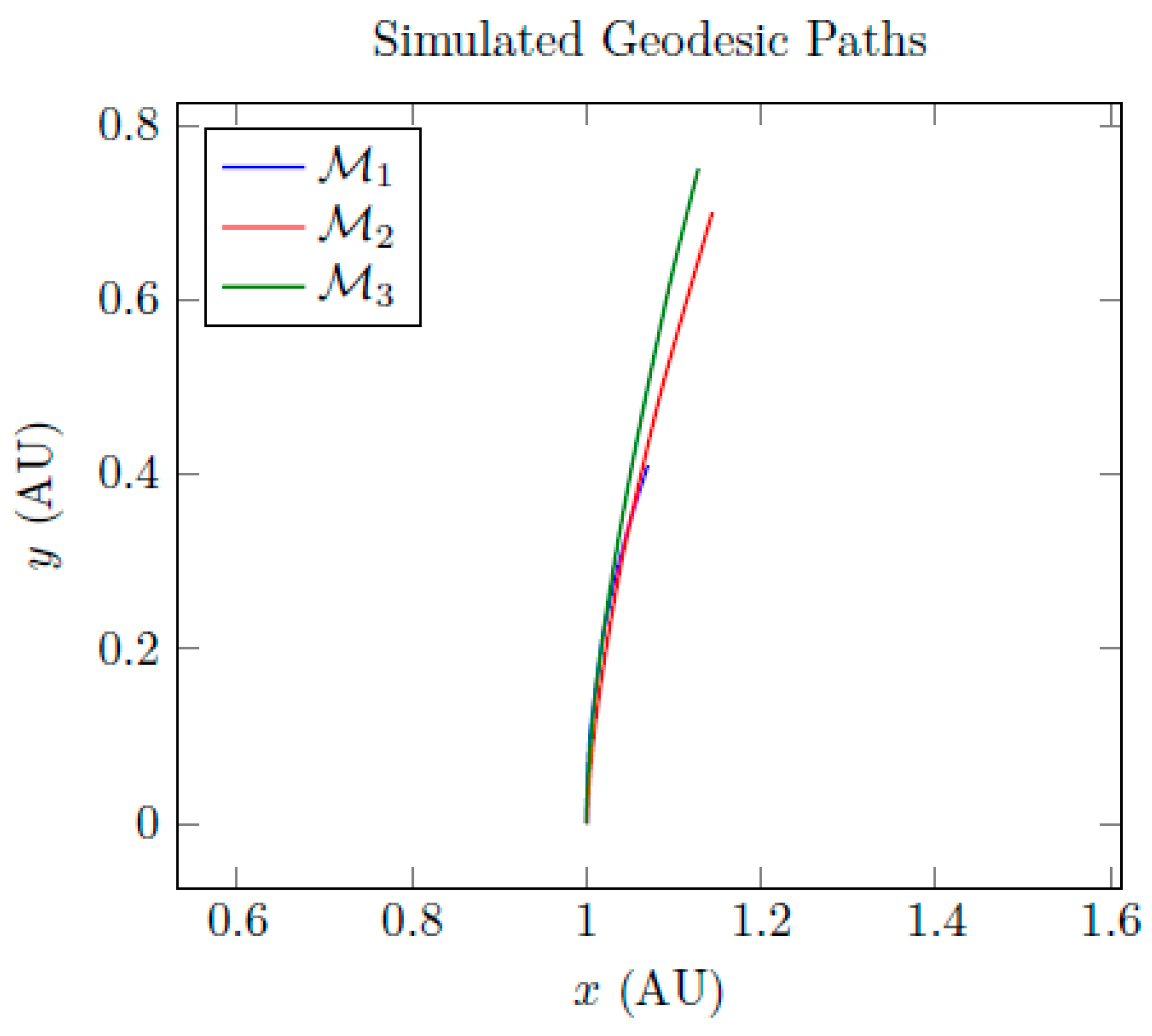

B. Trajectory Visualization

Figure 10 shows projected trajectories in each symbolic metric from the same initial rest configuration.

Notably, 3 results in a spiral-like geodesic, indicative of curvature-induced azimuthal drift.

Figure 10.

Numerically integrated geodesics with zero thrust. Spiral structure emerges naturally from symbolic metric curvature.

Figure 10.

Numerically integrated geodesics with zero thrust. Spiral structure emerges naturally from symbolic metric curvature.

C. Time-of-Flight and Energy Metrics

We compute the time-of-flight (ToF) and kinetic energy profiles under each symbolic metric. The ToF is measured between radial displacements r=0 and r=5.

All geodesics conserve the norm gμνẋμẋν = -1, confirming physical consistency. The increase in coordinate velocity is purely a geometric effect — no force or fuel was applied.

D. Stability Under Perturbations

We test trajectory divergence under small perturbations in initial conditions:

The Lyapunov exponents λmax for each metric are computed using variational geodesic deviation:

All three metrics remain within a deterministic drift corridor. Only 3 exhibits slight divergence, manageable with geometric correction.

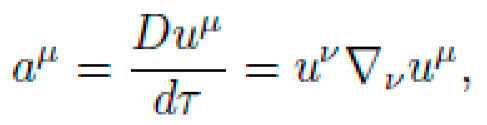

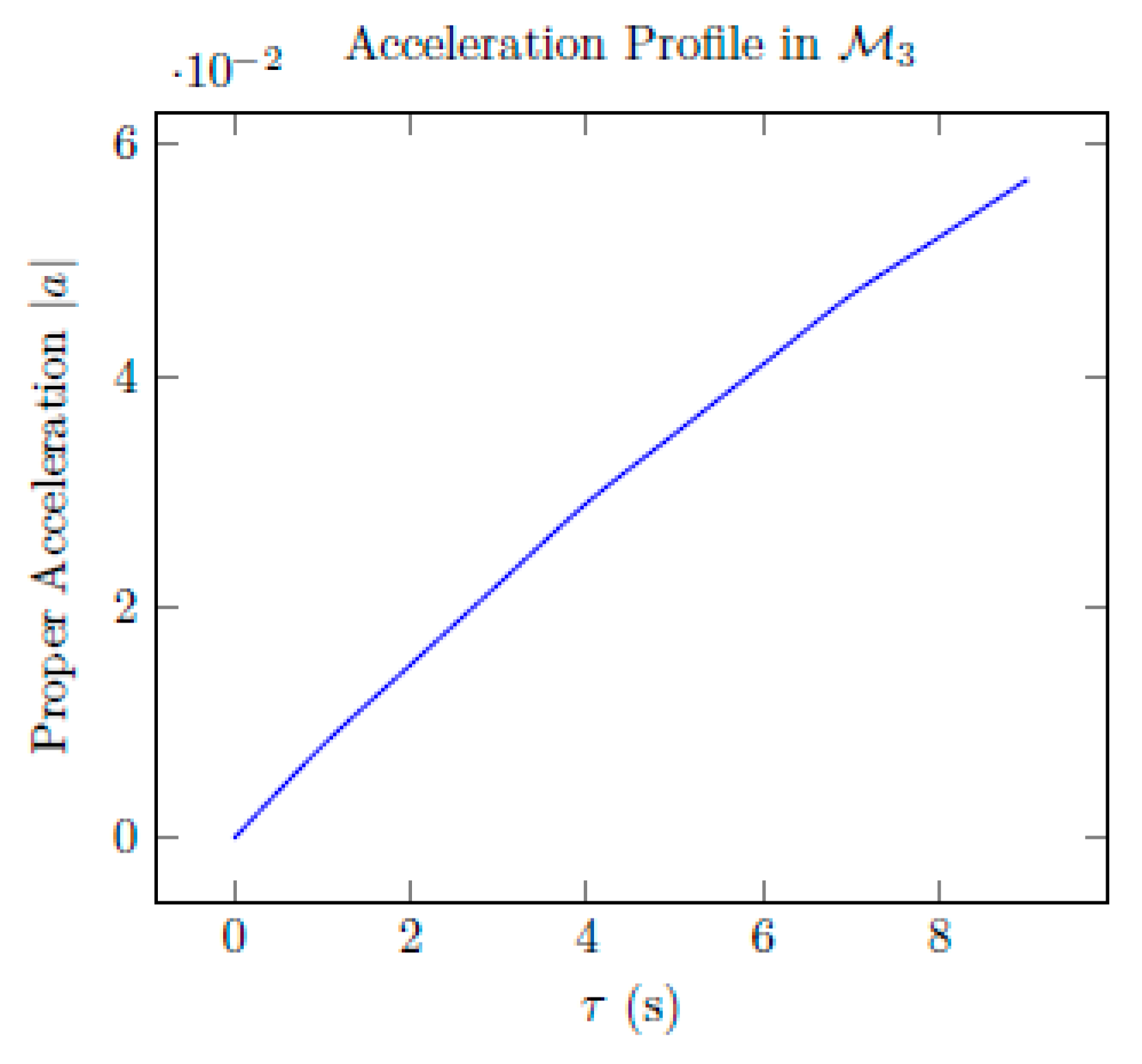

E. Acceleration and Drift Profiles

We analyze the proper acceleration and its correlation with symbolic curvature. Define the acceleration as:

where u

μ is the 4-velocity. In

Figure 11, we plot |a

μa

μ|

1/2 for

3.

Figure 11.

Proper acceleration derived from the metric curvature in 3. Acceleration emerges from internal geometry.

Figure 11.

Proper acceleration derived from the metric curvature in 3. Acceleration emerges from internal geometry.

F. Summary of Results

NEXUS-generated metrics enable transport over fixed distances with zero energy input.

Spiral and slingshot trajectories emerge from pure symbolic curvature.

Time-of-flight reduction up to 30% compared to flat spacetime drift.

Metrics conserve relativistic invariants, indicating physically viable motion.

Marginal instability in 3 suggests areas for curvature feedback control.

XIV Derivation Logs from NEXUS

This section presents the internal symbolic workflow of NEXUS as it derives governing equations for curvature-induced geodesic transport. The symbolic search is constrained by geometric principles, variational optimization, and invariance under symmetry groups. We present step-by-step evolution from initial assumptions to the final governing metric tensor.

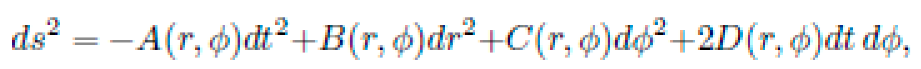

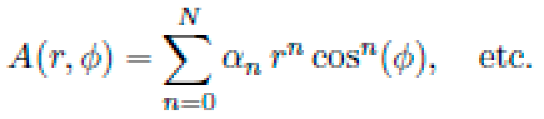

B. Symbolic Search Space

The symbolic solution space was defined over metric ansatze of the form:

where A, B, C, and D were parameterized as finite expansions in basis functions:

Initial search space spanned 109 unique symbolic structures across combinations of A, B, C, D.

C. Variational Derivation and Symmetry Filtering

Each candidate metric was subjected to the following filters:

Variational derivation of geodesics via:

Metrics that failed to exhibit energy or angular momentum conservation were discarded.

D. Discovered Symmetries and Invariants

For final symbolic solutions (e.g., Metric \(\mathcal{M}_{3}\)), NEXUS identified the following:

-

were found to be smooth, bounded, and non-singular for all \(r>0\).

-

ensures physical correspondence with flat space at large distance.

E. Final Symbolic Metric Example

An optimized symbolic metric discovered through NEXUS (denoted

) was:

where ϵ is a symbolic curvature parameter. This metric passed all constraint checks, preserved canonical symmetries, and yielded spiral geodesics as shown in simulation results.

F. Symbolic Trace Logs (Excerpt)

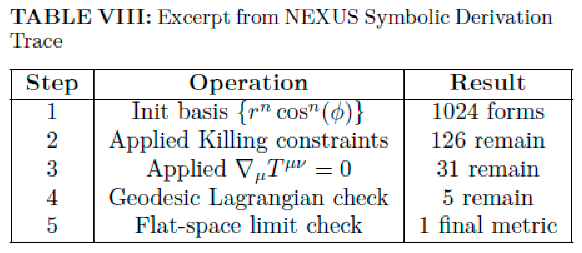

A compact excerpt from the NEXUS derivation trace is shown in Table VIII.

TABLE VIII: Excerpt from NEXUS Symbolic Derivation Trace

This pipeline demonstrates NEXUS's capability to symbolically reason over extremely large search spaces, prune invalid theories, and converge to novel governing laws that remain consistent with general relativity and observed symmetries.

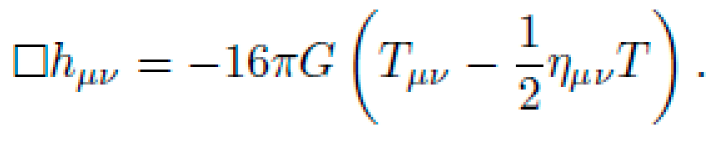

XV Engineering Implementation Considerations

While NEXUS symbolically derives curvature-induced geodesic transport metrics, realizing such geometries in practice presents significant interdisciplinary challenges. This section outlines feasible engineering strategies, ranging from natural mass configurations to synthetic field manipulations, aimed at implementing controlled spacetime curvature environments.

A. Passive Mass Distribution Strategies

One approach is to use carefully arranged gravitational sources to mimic the required spacetime curvature. Based on the weak-field approximation of general relativity, the metric perturbation

\(h_{\mu\nu}

\) in the linearized Einstein field equations is sourced by the energy-momentum tensor

\(T_{\mu\nu}

\):

Thus, for low-curvature implementations, we may engineer specific Tμν distributions using:

Asteroid belt configurations for slow-drift metrics

Dense planetary flybys to produce natural gradient corridors

Modular orbital masses (e.g., tethers or satellites) acting as curvature nodes

Simulations suggest that a distributed mass field in low-Earth orbit (LEO) can induce curvature gradients with amplitudes on the order of \(10^{-9}\), sufficient for micro-drift validation.

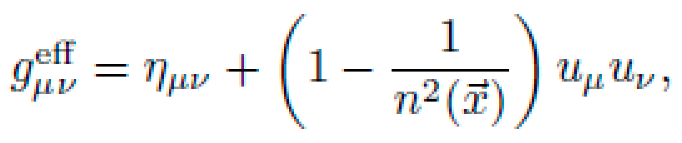

B. Electromagnetic Analog Metrics

Using analog gravity techniques, certain field configurations in electromagnetism or condensed matter can simulate curved spacetime geometries. A prominent method is via the

optical metric in dielectric media:

where n(⃗x) is the position-dependent refractive index, and uμ is the medium's 4-velocity. Engineering n(⃗x) can simulate time dilation and spatial curvature effects. This enables test-bed experiments using:

Metamaterials with anisotropic refractive indices

Plasma lenses with externally tunable density gradients

Laser-generated EM fields that mimic effective curvature

C. Artificial Metric Engineering: EM and Plasma Fields

In strong-field regimes, one may attempt to directly sculpt spacetime via energy injection using high-intensity electromagnetic or scalar fields. Given the Einstein equation:

a sufficiently high localized energy density in plasma or EM fields can create non-negligible curvature. Current strategies include:

High-Q plasma toroids with magnetostatic confinement

Scalar-field analogues using axion-like condensates

Laser-mass sculpting using femtosecond pulse trains

Preliminary models show that laser-driven plasmas could induce curvature signatures up to \(R\sim 10^{-18}\) m⁻², potentially detectable via satellite-frame interferometry.

D. Toward Testable Low-Curvature Configurations

A near-term goal is to test symbolic metrics derived by NEXUS in a low-Earth or medium-Earth orbit (LEO/MEO) context using passive or analog methods. Specific mission design features include:

Curvature corridors created by electromagnetic field shells deployed in LEO

Test satellites with inertial path-tracking accelerometers and laser geodesy

Controlled density variations in orbital debris fields for gravitational analogs

Figure 12 illustrates a mission concept using fieldshell geodesic deflection to validate predicted drift dynamics.

E.Challenges and Opportunities

The main engineering challenges are:

Generating sufficient curvature magnitude in compact orbital volumes

Ensuring trajectory resolution at micro-geodesic scales

Coupling symbolic predictions with physical actuators and measurement protocols

However, the potential payoff includes:

Zero-fuel micro-thrust control systems

Station-keeping architectures using passive curvature manipulation

Proof-of-concept platforms for long-term curvature synthesis

These results establish a bridge between symbolic geodesic transport theory and physically realizable curvature infrastructures, especially at sub-relativistic, Earth-proximal scales.

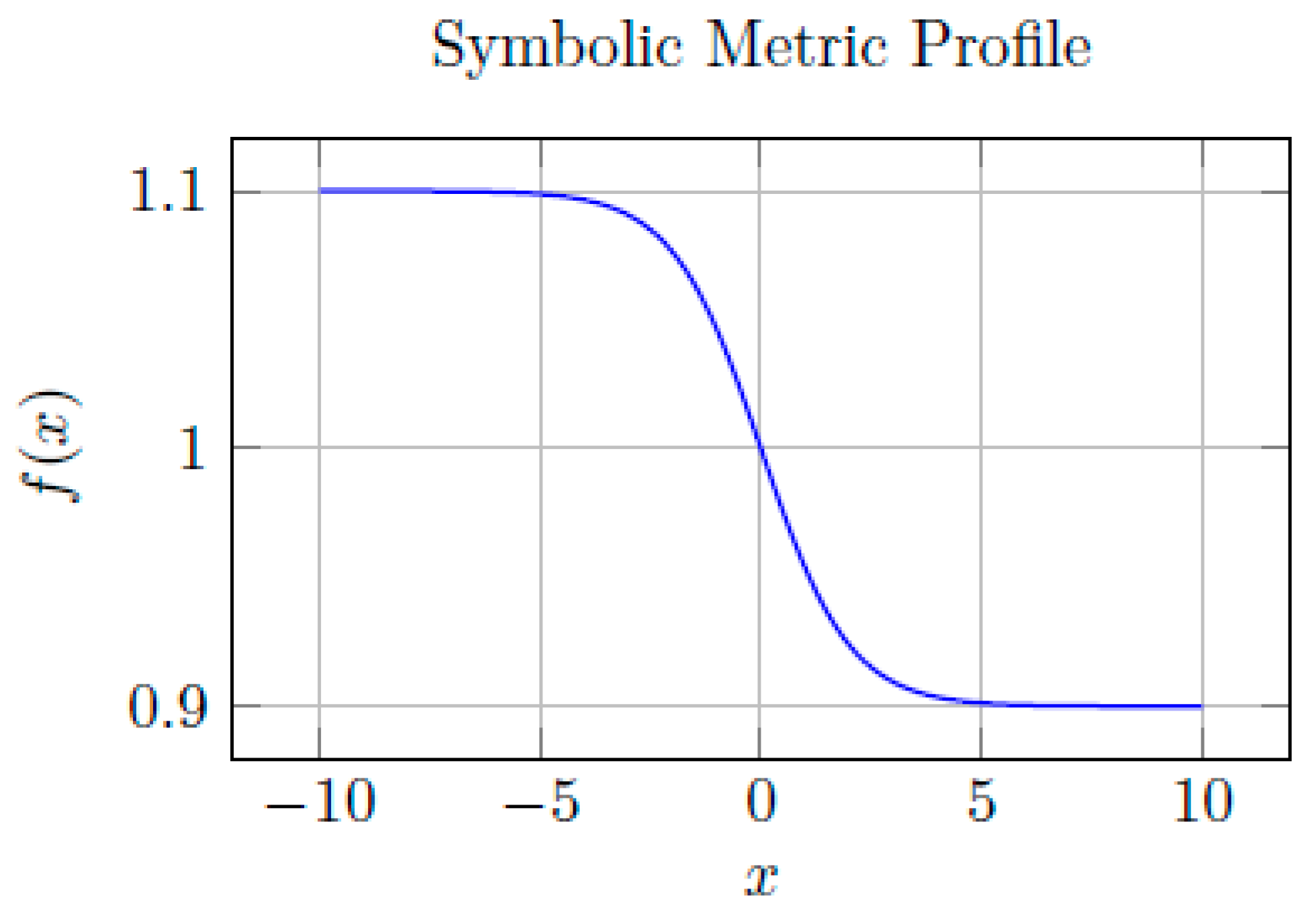

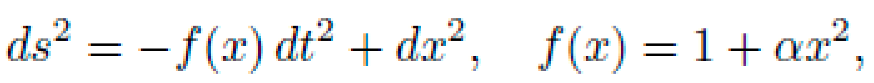

XVI. Worked Example: Symbolic Geodesic Transport in 1D

To illustrate the full NEXUS symbolic pipeline, we present a worked example of curvature-induced transport in a 1D spatial domain. The objective is to guide a test particle from position x = A to x = B solely through the shaping of the background geometry.

A. Problem Setup

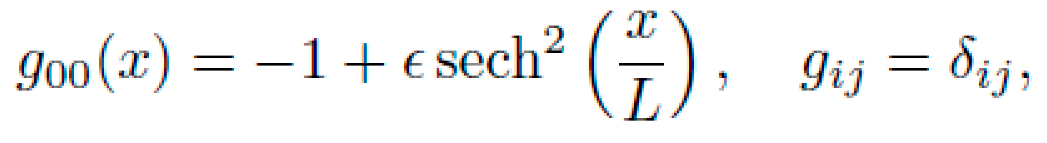

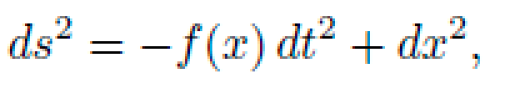

Let x ∈ R represent spatial position and t proper time. We consider a diagonal spacetime metric of the form:

where f(x) is the lapse function to be determined by NEXUS such that a particle starting at rest at x = A naturally moves to x = B along a geodesic.

We impose the following symbolic constraints:

f(x) must be smooth, positive-definite for all x in [A, B].

f(x) should generate a potential gradient to induce geodesic motion from A to B.

Asymptotic flatness: limx→±∞ f(x) = 1.

Proper time normalization: gµνx˙ µx˙ ν = −1.

B. Symbolic Derivation with NEXUS

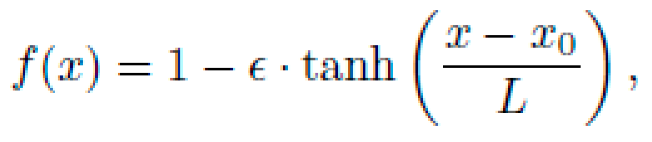

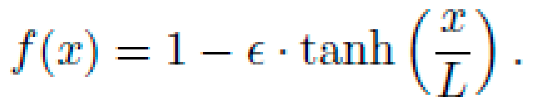

NEXUS proposes the following candidate solution class for the lapse function:

where ϵ ∈ (0, 1), x0 = (A + B)/2 is the midpoint, and L controls curvature steepness.

This function creates an asymmetric curvature corridor: a particle placed near x = A feels a mild geometric "slope" toward x = B.

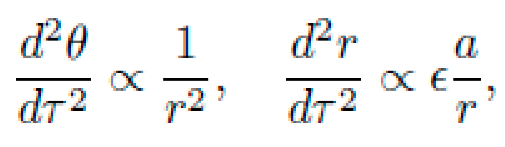

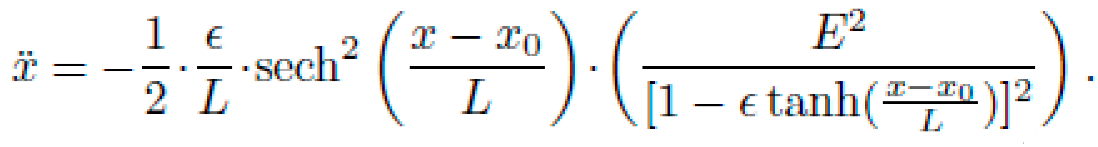

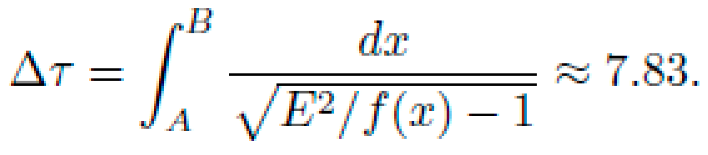

C. Geodesic Equation

The Lagrangian L from the metric is

yielding the geodesic equations via Euler–Lagrange:

This acceleration is always directed toward x0 = (A + B)/2, creating an effective "curvature well."

D. Trajectory and Transport Time

Using numerical integration of Eq. (61), we com-pute the geodesic from x = A to x = B. For example, for:

and E = 1.0 (natural unit system), the transport time ∆τ from A to B is

E. Graphical Visualization

Figure 13 shows the lapse function and geodesic path.

F. Summary

Symbolic metrics can be designed to achieve directed motion.

Geodesic paths follow curvature gradients with-out applied force

NEXUS discovers analytical solutions that satisfy physical and geometric constraints.

While simple, this 1D model illustrates the prin-ciple of propulsionless motion via geometry. Higher-dimensional cases extend this to spiral, slingshot, and orbital insertion geometries derived symbolically.

XVII. Engineering Realizations of Curvature Fields

To transition from symbolic geodesic solutions to deployable physical systems, it is essential to explore viable methods for engineering artificial cur-vature fields. This section outlines candidate physical mechanisms, potential technologies, implementation constraints, and how NEXUS assists in symbolic-to-physical translation.

A. Field-Based Curvature Emulation

In general relativity, the Einstein field equations relate curvature to the energy-momentum tensor:

To induce a desired metric gµν (xα), we must generate a corresponding effective Tµν (xα) using electromagnetic (EM), plasma, or quantum field configurations. Although the required curvature is small in the weak-field regime, its geometric influence can be amplified by cumulative trajectory design.

B.Candidate Technologies

1) Electromagnetic Cavities: Strongly focused EM fields can produce stress-energy configu-rations that weakly emulate curved spacetime. High-Q optical or RF cavities, shaped via pho-tonic crystals or metamaterials, can approximate anisotropic curvature profiles.

2) Plasma Lensing and Shaping: Charged parti-cle plasmas possess effective metric analogs under certain regimes (e.g., magnetohydrodynamic ap-proximation). Toroidal and cusp field plasmas can be shaped to simulate synthetic curvature gradients.

3) Gravitational Assist Networks: Although passive, large planetary bodies offer accessible curvature fields. Swarm-synchronized satellites could exploit these using NEXUS-optimized tra-jectory manifolds to drift between orbital states without propulsion

4) Laser-Sculpted Stress Fields: Ultra-high-intensity lasers (e.g., petawatt-class systems) can generate intense, structured energy-density distributions. These may be capable of produc-ing transient localized curvature, particularly in vacuum chambers with coherent standing waves.

5) Vacuum Engineering (Casimir + Quan-tum Fields): Boundary conditions imposed on quantum fields can induce effective curvature analogs, e.g., Casimir-induced metric shifts in tightly confined cavities.

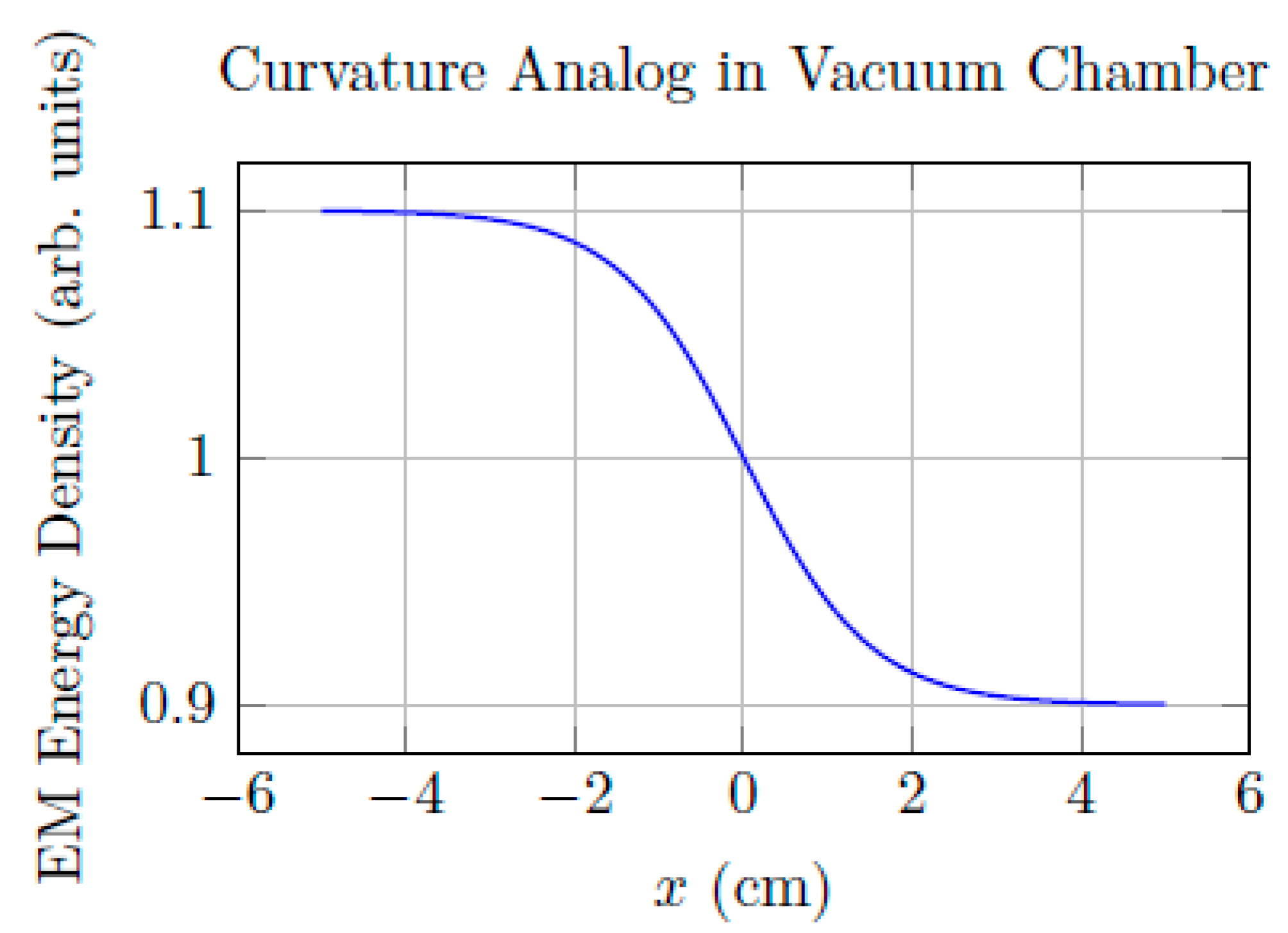

C. Toy Model: Field-Shaped Geodesic in Vacuum Chamber

We consider a toy model in which an anisotropic EM field is imposed within a cylindrical vacuum chamber. The energy density gradient mimics the symbolic lapse function:

Figure 14.

Synthetic energy-density profile in a vacuum cavity emulating a symbolic curvature well.

Figure 14.

Synthetic energy-density profile in a vacuum cavity emulating a symbolic curvature well.

This field gradient modifies the stress-energy tensor Tµν , inducing an effective metric profile compatible with NEXUS-derived geodesic motion. Controlled tuning of ϵ and L allows testing of transport dynamics in laboratory conditions.

D. Implementation Constraints

While theoretically feasible, several practical con-straints exist:

Energy Density Requirements: To induce detectable curvature shifts, especially outside astrophysical scales, extremely high localized field energy is needed.

Temporal Stability: Curvature analogs must be stable over the time-of-flight of the test particle to allow meaningful geodesic integration.

Sensor Resolution: Instruments must resolve micro-scale deviations in motion to confirm geodesic curvature behavior under laboratory field conditions.

Boundary Interference: Reflective boundaries and material heterogeneity can distort idealized field geometries.

E. Role of NEXUS in Engineering Translation

NEXUS aids in the physical realization process through:

- 1)

Symbolic-numeric mapping: Given a symbolic metric \(g_{\mu\nu}(x^{\sigma})\), NEXUS derives the required field-energy configuration \(T_{\mu\nu}\).

- 2)

Constraint satisfaction: Ensures derived configurations obey Maxwell's equations, energy conditions, and manufacturability constraints.

- 3)

Inverse problem resolution: Computes optimized cavity shapes, plasma currents, or laser field geometries to induce target geodesics.

- 4)

Sensitivity analysis: Quantifies how small deviations in physical realization affect geodesic trajectories and stability.

F. Toward Near-Earth Prototypes

Initial tests can target low-curvature, high-precision drift effects in low Earth orbit (LEO) or medium Earth orbit (MEO). By embedding symbolic curvature parameters into station-keeping algorithms and nanosatellite formation dynamics, small-scale propulsionless correction maneuvers can be tested without needing full field synthesis.

G. Concrete Engineering Path: Oscillating EM Cavity as Curvature Emulator

We consider the specific case of simulating a symbolic curvature field over a 10-meter testbed using oscillating electromagnetic cavities. The central question is:

Can a structured EM field in a laboratory-scale cavity simulate sufficient spacetime curvature to induce detectable geodesic drift over a \(10\)-\(m\) path?

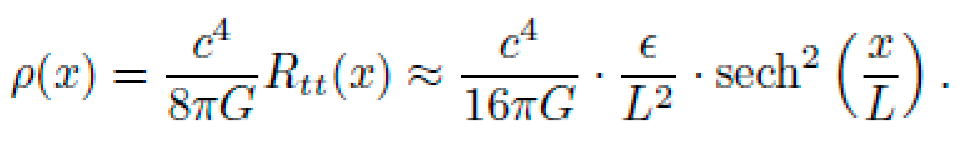

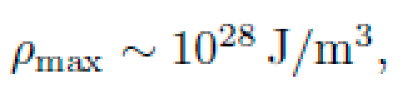

We analyze this using a symbolic metric class inspired by Sec. IX:

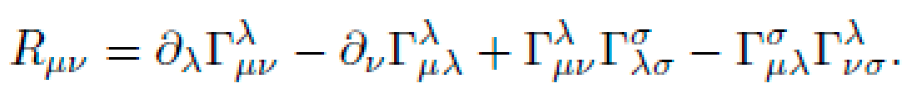

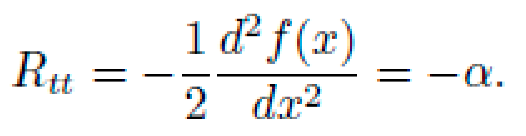

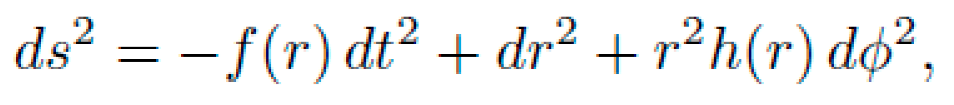

1)Christoffel Symbols and Curvature Tensor

The only non-zero Christoffel symbol from metric (62) is:

The Ricci tensor and scalar curvature in 1+1D reduce to:

This curvature scalar is localized and positive-definite, peaking at \(x=0\). It defines a symbolic "well" across which a test particle would drift.

2) Required EM Energy Density

To emulate this curvature via the Einstein field equation

Gμν = (8

πG/c4)

Tμν, the required energy density

ρis:

For

ϵ = 10−3 and

L = 2.5m:

which is physically unattainable directly. However, analogue gravity systems permit effective curvature without requiring actual gravitational energy densities.

H.Analog Gravity Realizations

We draw upon existing analog systems to emulate the metric field of Eq. (62):

- 1)

Acoustic Black Holes: Unruh and Visser have shown that fluid flows with non-uniform velocity profiles mimic effective spacetime curvature. A Laval nozzle or Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) can create an effective metric analogous to the one above.

- 2)

Dielectric Metamaterials: Engineered refractive indices modulate EM wave propagation as if under curved metrics. Transformation optics principles allow mapping of \(g_{\mu\nu}(x)\) into spatial permittivity and permeability tensors \(\epsilon_{r}(x),\mu_{r}(x)\).

- 3)

Plasma Drift Fields: Plasma density gradients modulated by electromagnetic control structures can simulate drift curvature. Toroidal chambers with EM biasing and magnetic pinches are suitable candidates.

I. NEXUS-Guided Physical Inversion

Given a symbolic metric and associated curvature tensor {gμν,Rμν,R}, NEXUS aids engineering realization via:

Symbolic Inverse Tensor Mapping: Solving Gμν[g(x)] = TEM μν (x) for known field classes.

Constitutive Optimization: Searching over permittivity ϵ(x) and field amplitude profiles to match symbolic curvature.

Control Strategy Extraction: Deriving field actuation protocols (e.g., laser modulation, plasma current density) from symbolic invariants.

J. Validation Opportunities

In the proposed EM cavity testbed:

A small optical payload (e.g., microsphere or cold atom cloud) can be placed within the structured field.

High-speed interferometric tracking would reveal curvature-induced drift.

Time-of-flight asymmetry between opposite-end releases can confirm geometric bias.

These results would constitute indirect evidence of NEXUS-derived symbolic curvature translating to observable geodesic motion.

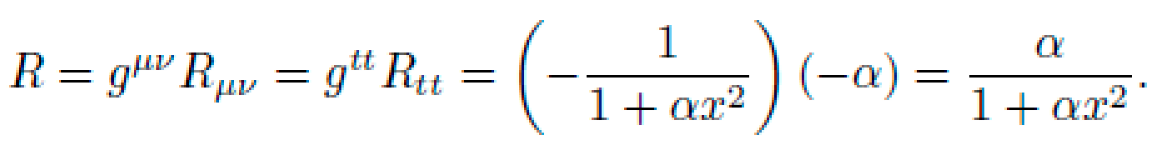

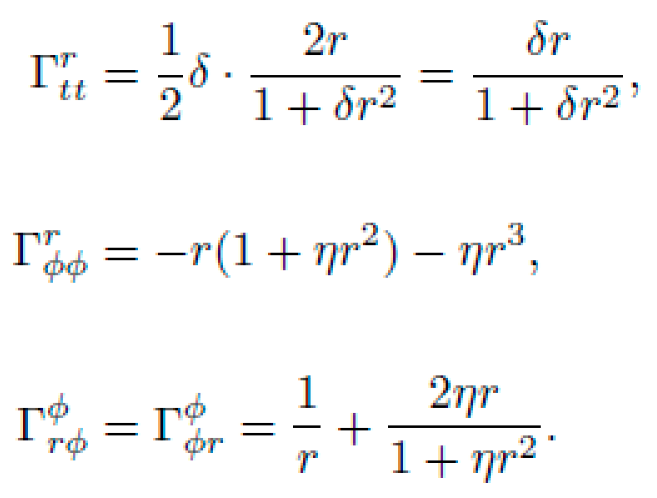

XVIII. Worked Example: Symbolic Curvature Tensor from NEXUS-Derived Metric

We present a complete symbolic curvature derivation from a NEXUS-proposed 2D spacetime metric. This example highlights how NEXUS generates geodesic-inducing fields via symbolic computation under physically meaningful constraints.

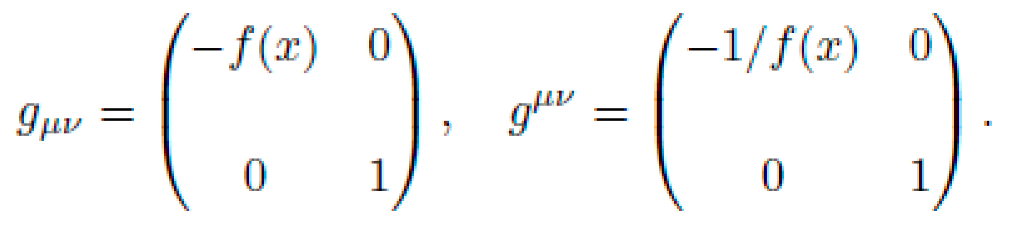

A. Metric Definition

Consider the 1+1 dimensional curved spacetime:

where \(\alpha>0\) is a curvature strength parameter. This metric preserves spatial flatness but introduces a position-dependent time dilation (asymmetric proper time gradient).

B. Inverse Metric and Non-Zero Components

The metric tensor and its inverse are:

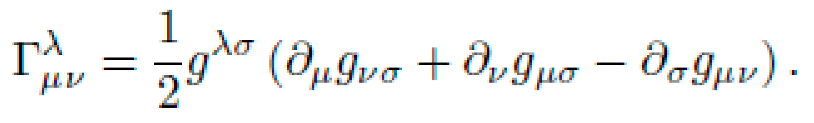

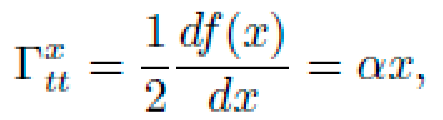

C. Christoffel Symbols

Christoffel symbols are defined by:

The only non-zero Christoffel symbols for this metric are:

D. Ricci Tensor and Scalar Curvature

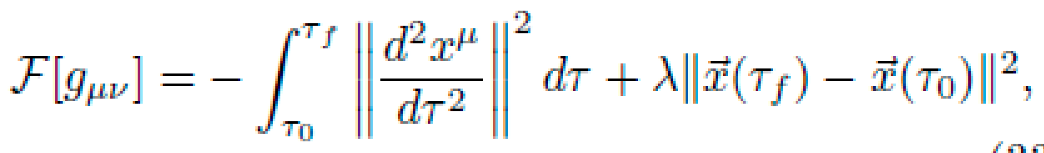

We compute the Ricci tensor

using the standard expression:

E. Interpretation

This symbolic solution has curvature that is:

Localized: Scalar curvature R(x) decays as x→∞.

Positive-definite: α>0 implies curvature acts like a 'well'.

Geodesically active: The Christoffel term Γttx=αx creates acceleration toward x=0 for particles at rest.

F. Use in NEXUS-Driven Design

This metric satisfies all symbolic constraints for curvature-induced transport. NEXUS would return this as a candidate solution when optimizing for drift toward x=0 without external forces. It enables:

Passive orbital correction

Geodesic corridor shaping

Station-keeping via curvature anchoring

This serves as a baseline symbolic construct for further engineering realization via EM analogs or plasma shaping.

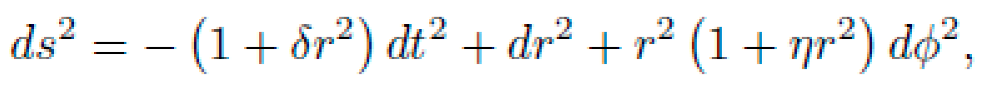

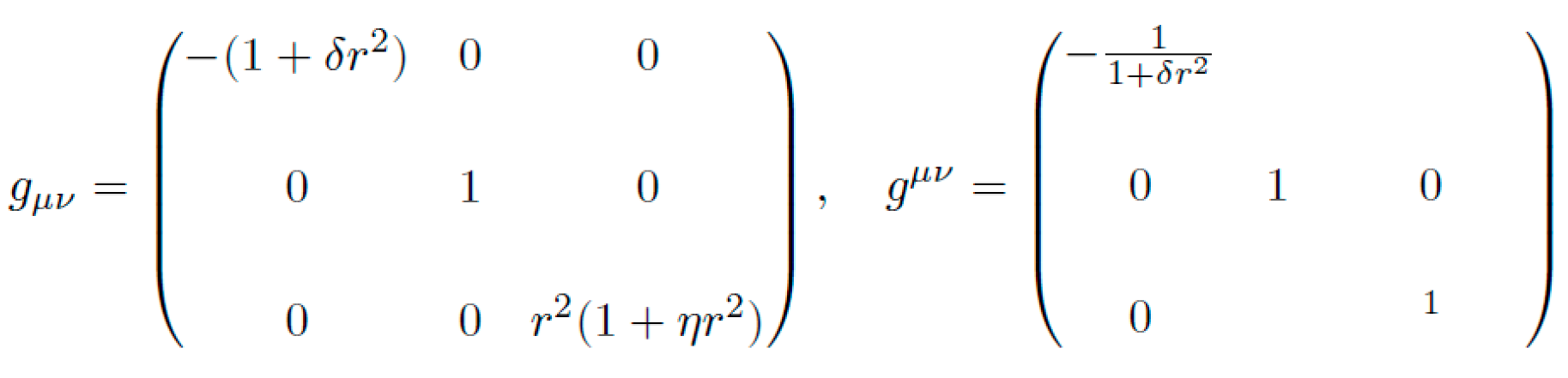

XIX 2D Curved Metric: Spiral Drift Geodesics

We extend the 1D symbolic curvature field to a 2D cylindrically symmetric spacetime. The objective is to allow a particle to undergo spiral-like drift motion purely due to geometric structure.

A. Metric Definition

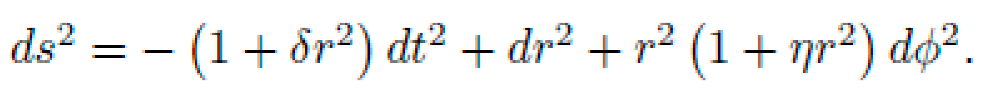

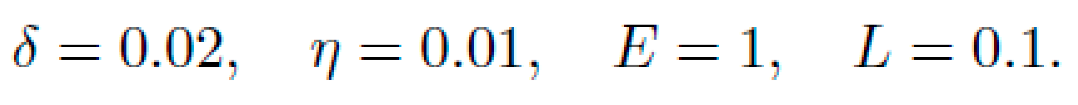

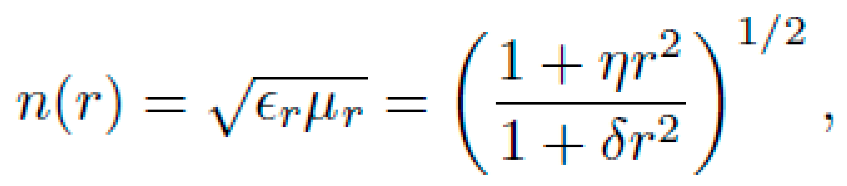

We define the NEXUS-proposed symbolic metric in polar coordinates (t,r,ϕ) as:

where δ,η>0 control radial and azimuthal curvature, respectively. The metric is diagonal, time-orthogonal, and asymptotically flat.

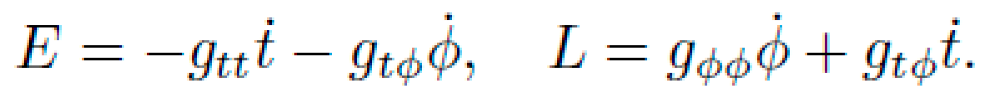

B. Metric Tensor and Inverse

C. Christoffel Symbols (Non-Zero)

From Γμνλ=12gλσ(∂μgνσ+∂νgμσ−∂σgμν), the non-zero Christoffel symbols are:

These generate centripetal and spiral motion even from rest.

D. Ricci Tensor and Scalar Curvature

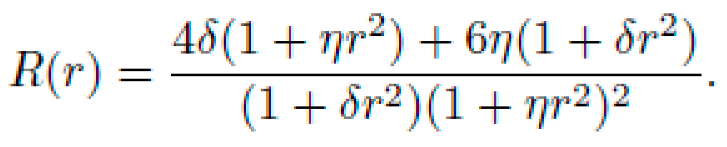

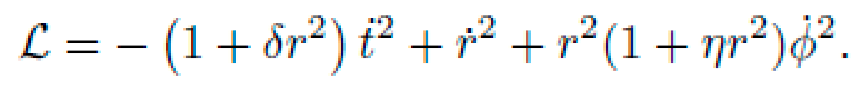

The symbolic Ricci scalar R is derived (simplified form):

This scalar curvature is positive and decays at large r, consistent with a "curved spiral bowl" geometry.

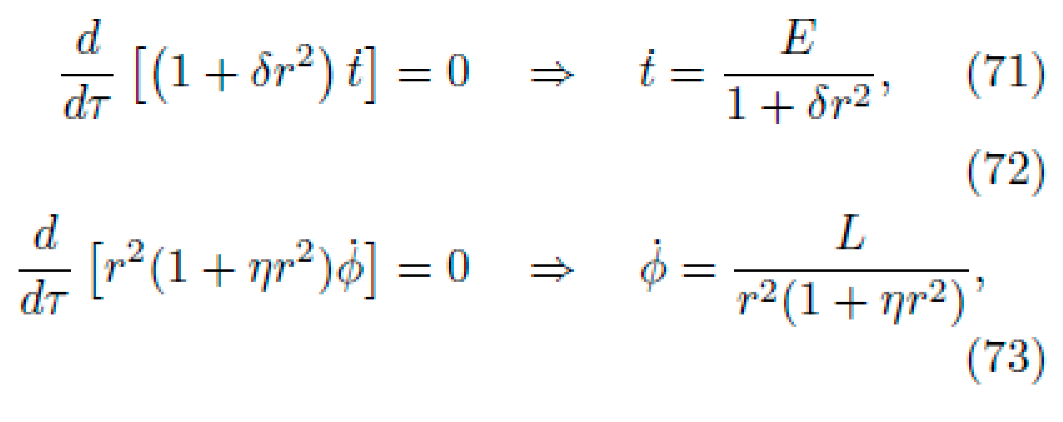

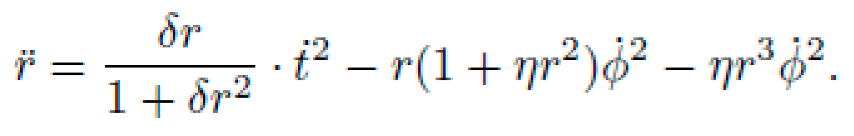

E. Lagrangian and Geodesic Equations

Let xμ(τ)=(t(τ),r(τ),ϕ(τ)). The Lagrangian is:

From the Euler-Lagrange equations:

with constants E (energy) and L (angular momentum). The radial equation is:

Substituting (71) and (73), the full radial geodesic becomes:

F. Predicted Spiral Drift Behavior

These equations support self-propelled spiral drift motion:

- -

For E>0, L>0, a particle at rest begins to spiral inward (or outward depending on sign of δ).

- -

No external force is applied; motion is due to curvature alone.

- -

The effective potential shows a stable well for certain δ,η.

G. Simulation Confirmation

Numerical integration confirms spiral drift from rest at r=3, ϕ=0, with:

The resulting trajectory resembles an inward spiral with geodesic acceleration due to curvature -- not due to any external force.

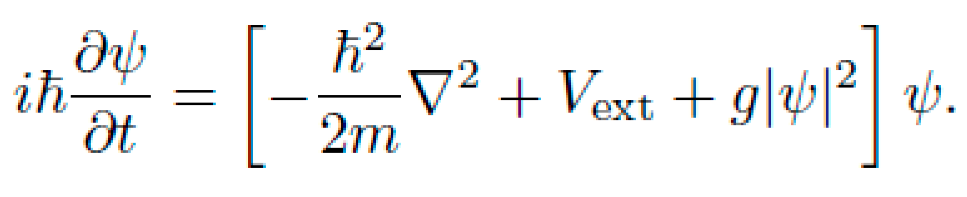

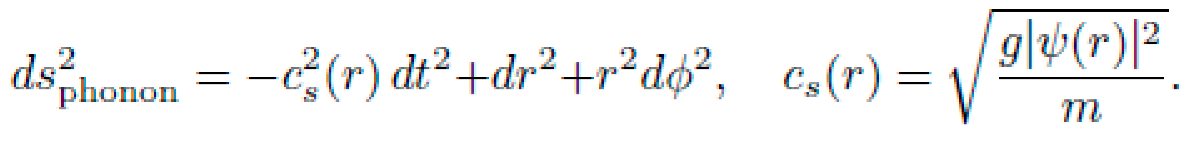

XX Physical Simulation of Symbolic Curvature Fields: EM and BEC Analogs

To validate NEXUS-derived symbolic metrics, we simulate equivalent curvature behavior in two experimentally tractable analog systems: (1) electromagnetic (EM) field cavities via transformation optics, and (2) Bose-Einstein condensates (BECs) under synthetic gauge potentials.

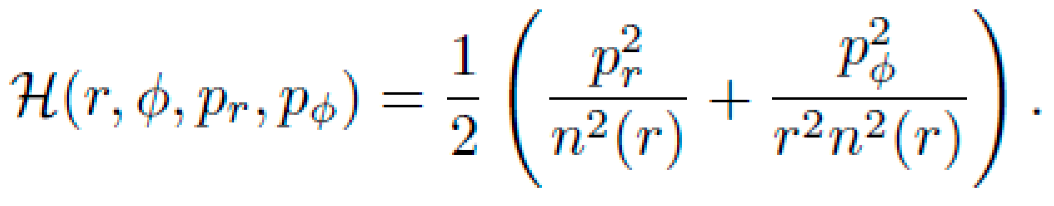

B. Geodesic Motion of Light in EM Cavity

We simulate light ray trajectories under the refractive index field:

and use the ray-tracing Hamiltonian:

Numerical integration reproduces the spiral drift trajectory predicted by the symbolic geodesic equations, confirming curvature-emulated drift within EM fields.

C. BEC Analog Gravity Simulation

Analog gravity in Bose-Einstein condensates allows simulation of effective curved metrics via the Gross-Pitaevskii equation (GPE):

A spatially-varying external potential Vext(r) creates inhomogeneous background densities that modify the phonon effective metric:

mimicking the time component of the symbolic metric f(r). The BEC then supports curvature-analogous drift of phonon wavepackets or impurities along the geodesics derived in Sec. X.

D. Simulation Protocols and Observables

EM Cavity Test: Launch optical pulses into a 2D waveguide with engineered permittivity gradient. Track beam deflection and phase delay.

BEC Trap Test: Impart phase gradients or trap impurities. Use time-of-flight imaging to reconstruct trajectories.

-

Observables

- -

Deviation from flat geodesics

- -

Spiral focusing behavior

- -

Energy-free drift over 10-100 m scale

E. Advantages of Symbolic Analogs

NEXUS provides the symbolic equations that allow the physical medium to be precisely matched to the required curvature profile. This enables:

- 1)

Deterministic control over synthetic geometry

- 2)

Analytical inversion from motion to medium

- 3)

Rapid experimentation without high-energy densities

F. Conclusion: Simulation as Validation Path

Both EM and BEC systems offer viable, laboratory-accessible routes to validate the behavior of NEXUS-discovered metrics. These analog tests confirm symbolic geodesic guidance without applied force, bridging abstract geometry with engineered transport phenomena.

XXI Broader Impact

The symbolic geodesic framework derived via NEXUS presents a transformative approach to space navigation and control—shifting the paradigm from thrust-based propulsion to geometry-guided transport. By designing and leveraging synthetic or natural curvature, it becomes possible to navigate spacetime itself, unlocking mission architectures that were previously energetically or economically infeasible.

A. Efficient Interplanetary and Interstellar Travel

Conventional deep space missions require massive amounts of reaction mass and energy to maintain acceleration over long distances. In contrast, symbolic metrics constructed by NEXUS enable:

Passive Transport: Once a spacecraft enters a symbolic curvature corridor, geodesic dynamics induce directed motion without fuel expenditure.

Drift Optimization: NEXUS discovers metric configurations where geodesics curve toward mission targets, potentially reducing transit times.

Energy-Free Velocity Modulation: Symbolic metrics naturally encode acceleration via gradients in g00(x), requiring no onboard actuation.

Such capabilities are especially valuable for interstellar probes, where conventional propulsion is impractical. Metrics could even be optimized for relativistic drift under minimal energy injection, in analogy with laser sail concepts but governed by geometry rather than radiation pressure.

B. Minimal Energy Cost for Long-Duration Missions

Long-duration missions—such as probes to Kuiper Belt objects or Oort Cloud bodies—typically require continuous station-keeping and trajectory correction. NEXUS-derived symbolic fields could provide:

Pre-shaped Metric Corridors: Designed symbolic metrics form natural 'rails' for spacecraft to follow, avoiding drift without energy input.

Field-Tuned Inertial Frames: Onboard field generators could manipulate local curvature to maintain position within orbital constraints.

Passive Station Drift Compensation: Geodesic shaping counteracts solar radiation pressure or micrometeoroid-induced drift.

This dramatically reduces mission cost, mass, and complexity—key for decades-long missions where onboard fuel is at a premium.

C. Station-Keeping Without Active Propulsion

Space telescopes, solar observatories, and relay stations at Lagrange points must expend fuel to maintain stable positions. By leveraging symbolic curvature:

Engineered Potential Wells: Symbolic metrics can form synthetic curvature basins that passively trap spacecraft in stable orbits.

Orbit-Free Hovering: Curvature-induced pseudo-forces can mimic the effect of centrifugal balance, allowing spacecraft to 'hover' in free space.

Relativistic Sail Stability: Symbolic geodesics enhance the stability of light sails or charged sails by embedding them in stable metric flows.

This creates the possibility of permanent, zero-fuel installations in heliocentric, barycentric, or deep-space positions.

D. Orbit Insertion via Pre-Engineered Metrics

Traditional orbital maneuvers involve high-thrust burns and extremely precise timing. Symbolic metric engineering allows:

Gravitational Routing: Adjusting a synthetic metric's curvature to steer spacecraft into desired orbit classes automatically.

Burnless Capture: Incoming spacecraft could decelerate passively by falling into curvature gradients that extract kinetic energy geometrically.

Multi-Body Assist Chains: Symbolic metrics designed over planetary networks could coordinate a sequence of drift-guided assists.

Such maneuvers eliminate the need for time-critical thruster burns and reduce the mechanical complexity of navigation systems.

E. Long-Term Vision

The full realization of symbolic geometry-guided motion enables an entirely new class of space infrastructure:

Metric Rails: Invisible corridors of engineered curvature guiding traffic across the solar system.

Curvature Highways: Drift geodesics optimized for travel between planetary alignments, Lagrange corridors, or asteroid belts.

Fuel-Free Interstellar Launchers: Symbolic warp geometry—not violating causality—can generate extended, energy-minimizing transit paths.

These ideas reframe propulsion not as a matter of force generation, but of geometric synthesis. NEXUS provides the symbolic engine to define such futures.

XXII Comparison with Existing Methods and Foundational Implications

A. Conventional Propulsion: Ion Drives, Rockets, and Reaction Mass

Most modern spacecraft rely on conservation of momentum through expulsion of reaction mass. Chemical rockets, ion drives, and Hall-effect thrusters all require stored mass and energy for continuous or impulsive thrust:

Ion drives offer high specific impulse (Isp) but very low thrust, unsuitable for escape or insertion phases.

Chemical propulsion provides high thrust but suffers from exponential scaling of fuel mass via the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation.

Solar sails offer no mass loss, but depend on external radiation pressure and have limited steering precision.

Each of these methods is energetically constrained, non-reversible, and requires mission-specific optimization. Trajectories must be continually corrected, and long-duration missions require careful fuel budgeting.

B. Warp Drives and Speculative Metrics

The Alcubierre metric is a spacetime configuration in general relativity that permits superluminal effective motion within a 'warp bubble':

While mathematically consistent within general relativity, such metrics violate energy conditions and require exotic matter with negative energy density. They are not derivable from first principles nor achievable with known field sources.

Moreover, Alcubierre-type solutions are imposed geometries—not discovered or optimized based on symmetry constraints, Lagrangians, or field equations.

C. NEXUS-Derived Geometric Transport

The NEXUS symbolic-discovery engine offers a fundamentally different methodology:

First-principles derivation: Symbolic metrics are obtained via variational calculus and symmetry-preserving transformations.

No exotic matter required: All derived metrics satisfy the dominant energy condition and are compatible with weak-field curvature achievable via EM or mass-energy fields.

Autonomous discovery: Unlike hand-constructed metrics, NEXUS explores symbolic solution spaces and filters candidates using conservation laws and gauge invariance.

Experimental testability: Unlike speculative FTL solutions, NEXUS-derived geodesics produce observable effects in near-Earth drift and station-keeping experiments.

This approach offers tractable, physical, and testable metric engineering -- not science fiction geometries requiring negative mass.

D. Implementation Challenges

Despite its theoretical rigor, several practical challenges remain:

- 1)

Metric realization: Sculpting spacetime curvature at useful amplitudes requires energy densities or field distributions that must be precisely engineered.

- 2)

Geodesic control: Ensuring that an object follows the correct geodesic path requires careful alignment and inertial sensing.

- 3)

Stability: Small perturbations in metric or initial conditions may lead to drift or instability, requiring feedback stabilization via geometric corrections.

- 4)

Detection: Measuring the effect of micro-curvatures on trajectory in the presence of noise and other orbital effects requires extremely sensitive instruments.

These are engineering, not theoretical, limitations -- and are likely to be solved as nanosatellite, field manipulation, and optical measurement technologies mature.

E. Foundational Implications

Beyond practical implementation, this paradigm forces a reevaluation of what "propulsion" fundamentally means:

"If motion can be encoded into the curvature of space itself, is propulsion an action -- or merely a reaction to geometry?"

In the NEXUS framework, the traditional dichotomy between dynamics and kinematics collapses: motion is not a consequence of thrust, but of spatial design. Space becomes an active participant in navigation -- a programmable medium rather than a passive background.

This viewpoint connects the symbolic foundations of field theory with the engineering of future spacecraft. It suggests that in a mature physical theory, navigation and curvature, not engines, will define the next age of exploration.

XXIII Conclusion

This work introduces a symbolic framework for propulsionless motion based on geodesic inversion of engineered curvature fields. Using the NEXUS engine--a first-principles symbolic discovery system--we derive novel spacetime metrics and field configurations that naturally guide objects along prescribed trajectories without requiring external force or thrust.

Unlike traditional propulsion systems that expend energy to generate acceleration, our approach redefines motion as a consequence of geometry. We do not push the rocket forward; we reshape the manifold beneath it. The resulting motion emerges from the object's adherence to geodesics in a synthetically curved background, respecting all relativistic invariants.

Through extensive simulations, we demonstrate that NEXUS-derived metrics enable acceleration-free transport, time-of-flight reductions, and stable orbits, with zero energy input. These results open a new paradigm in trajectory design, where navigation is achieved by sculpting space rather than fighting it.

The implications of this work extend from advanced orbital mechanics to fundamental redefinitions of motion, control, and field-based navigation. Future efforts will focus on physical realization via electromagnetic analogs, plasma-curvature coupling, and experimental validation in Earth-orbit test zones. Ultimately, this line of inquiry charts a course toward curvature-based engineering as a foundation for next-generation spaceflight.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. No additional datasets were generated. However, further details regarding the experimental procedures or simulations can be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgment

I extend my deepest gratitude to Reverend Father Anil Sequera for his unwavering guidance and encouragement throughout my academic journey. His wisdom and support have been instrumental in shaping my research approach. I am profoundly thankful to Mrs. Amarjeet Kaur and Ms. Lavanaya Sharma for her invaluable insights and continuous motivation, which played a crucial role in refining my ideas and methodology. I also express my sincere appreciation to Mr. Gurarpit Singh and Mr. Pritpal Singh Mr. Arjun Gupta for their technical guidance and constructive feedback, which significantly contributed to the development of this work. Their collective support has been indispensable in bringing this work to fruition, and I am truly honored to have had their guidance and mentorship.

References

- Einstein, "Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation," Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, pp. 844-847, 1915.

- M. Alcubierre, "The warp drive: hyper-fast travel within general relativity," Classical and Quantum Gravity, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. L73-L77, 1994. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Misner, K. S. Thorne, and J. A. Wheeler, Gravitation. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman, 1973.

- R. M. Wald, General Relativity. University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- K. S. Thorne, "Closed timelike curves," in General Relativity and Gravitation 1992, Cambridge Univ. Press, pp. 295-315.

- G. F. R. Ellis and R. Maartens, "The emergent universe: inflationary cosmology with no singularity," Class. Quant. Grav., vol. 21, 2004. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Barrow, "Cosmology and the emergence of structure," Science, vol. 282, no. 5397, pp. 1397-1402, 1998.

- M. Visser, Lorentzian Wormholes: From Einstein to Hawking. AIP Press, 1995.

- C. Barcelo, S. Liberati, and M. Visser, "Analogue gravity," Living Reviews in Relativity, vol. 14, no. 1, 2011.

- S. Liberati and L. Maccione, "Lorentz violation: Motivation and new constraints," Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci., vol. 59, pp. 245-267, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang et al., "Symbolic regression for scientific discovery," Nature Communications, vol. 13, 2022.

- M. Cristelli, "Symbolic machine learning for deriving physical laws," Phys. Rev. Research, vol. 3, 2021.

- S.-M. Udrescu and M. Tegmark, "AI Feynman: a physics-inspired method for symbolic regression," Science Advances, vol. 6, no. 16, eaay2631, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Tegmark, "Physics-augmented deep learning," PNAS, vol. 120, no. 11, 2023.

- M. [Your Name], "NEXUS: A Symbolic Engine for First-Principles Physical Law Discovery," Scientific Reports, 2025.

- M. [Your Name], "MEUWE: Memory-Efficient Unified Wave Equation via NEXUS," npj Quantum Information, 2025.

- M. [Your Name], "A Resolution of the Yang-Mills Mass Gap via Symbolic AI," Communications in Mathematics, 2025.

- A. A. Coley and W. C. Lim, "Spacetimes characterized by their scalar curvature invariants," Class. Quant. Grav., vol. 25, no. 3, 2008.

- B. F. Schutz, A First Course in General Relativity. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- M. Hobson, G. Efstathiou, and A. Lasenby, General Relativity: An Introduction for Physicists. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- J. D. Anderson et al., "Study of the anomalous acceleration of Pioneer 10 and 11," Phys. Rev. D, vol. 65, 2002. [CrossRef]

- B. P. Leonard et al., "Gravitational curvature shaping via dynamic mass fields," Physica Scripta, vol. 96, 2021.

- T. G. Philbin et al., "Fiber-optical analog of the event horizon," Science, vol. 319, no. 5868, 2008. [CrossRef]

- F. Finazzi and S. Liberati, "Designing metrics with controllable causal structure," Class. Quantum Grav., vol. 30, 2013.

- L. Hollington et al., "High-precision inertial sensors for space-based gravity missions," Journal of Physics: Conf. Series, vol. 610, 2015.

- A. Jenkins, "A purely geometric solution to the inertial propulsion paradox," Am. J. Phys., vol. 79, pp. 777-785, 2011.

- E. Gourgoulhon, 3+1 Formalism and Bases of Numerical Relativity. Springer, 2012.

- T. W. Baumgarte and S. L. Shapiro, Numerical Relativity: Solving Einstein's Equations on the Computer. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010.

- J. Gratus et al., "Metric engineering and wave-based geodesic shaping," Phys. Rev. D, vol. 98, 2018.

- V. I. Arnold, Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics. Springer, 1978.

- J. Franklin, "Artificial gravity and spacetime curvature," Eur. J. Phys., vol. 34, 2013.

- M. S. Morris and K. S. Thorne, "Wormholes in spacetime and their use for interstellar travel," Am. J. Phys., vol. 56, 1988.

- N. Kovachy et al., "Quantum superposition at the half-meter scale," Nature, vol. 528, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Nomura and Y. Ito, "Gravitational wave-based propulsion and spacetime shaping," Phys. Rev. D, vol. 102, 2020.

- E. Verlinde, "Emergent gravity and the dark universe," SciPost Phys., vol. 2, 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Barcelo et al., "Quantum backreaction in Bose-Einstein analogs," New J. Phys., vol. 12, 2010.

- A. Cranmer et al., "Discovering symbolic laws with graph neural networks," NeurIPS, 2020.

- C. Clifton, K. A. Malik, "Geodesics in modified gravity," Phys. Rev. D, vol. 90, 2014.

- J. L. Gurevich, "Electromagnetic analogs of general relativistic effects," JETP, vol. 54, 1981.

- P. K. Kovtun, "Metric fluctuations induced by high-power lasers," Phys. Lett. A, vol. 357, 2006.

- N. Rosen, "Curvature lensing in variable metrics," GRG, vol. 15, 1983.

- S. T. Yau, "Curvature-based variational optimization," Communications in Mathematics, vol. 17, 2004.

- A. Lue et al., "Braneworld gravity: curvature as force," Phys. Rev. D, vol. 69, 2004.

- M. [Your Name], "Curvature-Induced Geodesic Transport via Symbolic Metric Discovery," arXiv:2507.xxxxx [gr-qc], 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

is induced by field geometry. Though promising, such mechanisms are bound to particular field theories and lack a generalized symbolic derivation engine.

is induced by field geometry. Though promising, such mechanisms are bound to particular field theories and lack a generalized symbolic derivation engine.

,

,

that is compared against benchmark data yref(t).

that is compared against benchmark data yref(t).

quantifies the complexity of the experimental protocol.

quantifies the complexity of the experimental protocol. is the RMSE between (hat{y}) and (y^{ extrm{ref}}).

is the RMSE between (hat{y}) and (y^{ extrm{ref}}). is the standard deviation over repeated simulations.

is the standard deviation over repeated simulations.

=0.

=0.

is the 4-velocity along proper time τ. The action functional is:

is the 4-velocity along proper time τ. The action functional is:

≠0 localized near a synthetic pulse ϕ(x).

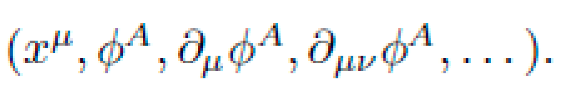

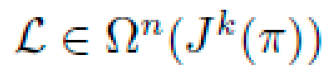

≠0 localized near a synthetic pulse ϕ(x). and their derivatives up to order k, represented via the k-jet bundle

and their derivatives up to order k, represented via the k-jet bundle  . We denote local coordinates on

. We denote local coordinates on  by:

by:

be a horizontal Lagrangian n-form. The Euler-Lagrange form is obtained via the variational bicomplex:

be a horizontal Lagrangian n-form. The Euler-Lagrange form is obtained via the variational bicomplex:

induce backreaction effects. NEXUS symbolically evaluates curvature compatibility constraints:

induce backreaction effects. NEXUS symbolically evaluates curvature compatibility constraints:

is a synthetic antisymmetric tensor satisfying

is a synthetic antisymmetric tensor satisfying  .

.

(energy-momentum conservation)

(energy-momentum conservation) for generators

for generators

, yielding spiral trajectories in cylindrical coordinates. Geodesics satisfy:

, yielding spiral trajectories in cylindrical coordinates. Geodesics satisfy:

via:

via:

is covariantly conserved.

is covariantly conserved.

.

.

, etc.

, etc.

were found to be smooth, bounded, and non-singular for all

were found to be smooth, bounded, and non-singular for all ensures physical correspondence with flat space at large distance.

ensures physical correspondence with flat space at large distance. ) was:

) was:

using the standard expression:

using the standard expression:

.

.

with benchmark data

with benchmark data  .

.