1. Introduction

Aspergillus fumigatus is a common saprophytic fungus, widely distributed across diverse ecological niches worldwide. It is frequently found in soil, air, water, and the vicinity of plant roots, as well as in organic matter-rich environments like compost and decaying vegetation [

1,

2,

3,

4]. As the most prevalent airborne opportunistic fungal pathogen in humans,

A. fumigatus poses the gravest threat to immunocompromised individuals [

5,

6,

7]. It is estimated that invasive aspergillosis affects nearly 10% of at-risk patients globally each year, with a case-fatality rate that can reach as high as 88% in specific high-risk cohorts [

8,

9]. Triazoles, including itraconazole (ITR), voriconazole (VOR), posaconazole (POS) , and isavuconazole (ISA), are the first-line agents for treating invasive

A. fumigatus infections [

4,

10]. However, since the first case of itraconazole-resistant

A. fumigatus was reported in the United States in 1997 [

11], azole-resistant

A. fumigatus (ARAF) strains have been identified in most countries and are associated with a grave prognosis, as illustrated by a case series that invasive aspergillosis (IA) linked to them had a 100% 90-day mortality rate (n=10) [

12,

13]. The emergence of ARAF constitutes a major challenge to human health and environmental safety [

14,

15,

16].

Evidence increasingly points to a concerning global trend of rising ARAF infections, with resistant strains now being detected even in triazole-naïve patients [

17,

18,

19]. These results indicate that many ARAF strains in triazole-naïve patients may be directly acquired from environmental populations. Consequently, understanding the prevalence and spread of triazole resistance in environmental

A. fumigatus populations is thus essential for preventing ARAF aspergillosis outbreaks.

Guizhou, located in southwest China, is known as the "Karst Province" — with 73.6% of its land area composed of karst landforms and 92.5% covered by mountains and hills [

20,

21,

22]. Due to the extremely fragile ecological environment and the existence of numerous underground karst caves, the difficulty and cost of road construction in karst areas are far higher than in other regions. This kept Guizhou Province in an almost closed state through most of its history [

21]. In recent decades, there has been considerable research interest in the genetic diversity and structural patterns of Guizhou's plants and animals, encompassing key species like wild tea [

23], cultivated rice [

24], indigenous chicken [

25], and

Dendrothrips minowai, commonly known as stick tea thrip, a significant pest in tea plantations across China, Japan, and Korea [

26]. A recent study has shown that ascomycetes in this region are highly diverse [

27]. However, the links between genetic structure, geological factors, and the evolutionary histories of fungi remain relatively poorly understood in Guizhou. We hypothesize that the mountainous environment and inconvenient transportation in Guizhou Province limit the dispersal of

A. fumigatus, thereby affecting its genetic structure. Meanwhile, we also aim to investigate the prevalence of ARAF in agricultural environments of this region.

In this study, we sampled extensively and investigated the population structure of

A. fumigatus from vegetable gardens at nine distinct geographic locations in Guizhou Province. A panel of nine short tandem repeats (STRs) markers, which have been widely used for genotyping strains of

A. fumigatus [

28], were used to determine the genotypes of our strains. In addition, we investigated the susceptibilities of the strains to two common medical triazoles used for treating aspergillosis, itraconazole and voriconazole. For ARAF strains, we analyzed the DNA sequence at the azole target gene

cyp51A. The obtained genotype information was compared with those from other parts of the world. We aimed to: (i) reveal the genetic structure of the

A. fumigatus from the karst areas in Southwest China, (ii) explore the relative roles of geographical barriers and landscape features in shaping the population genetic diversities of this species, and (iii) investigate the prevalence of triazole-resistant strains and their potential mutations associated with azole resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Samples, A. fumigatus Isolation and Identification

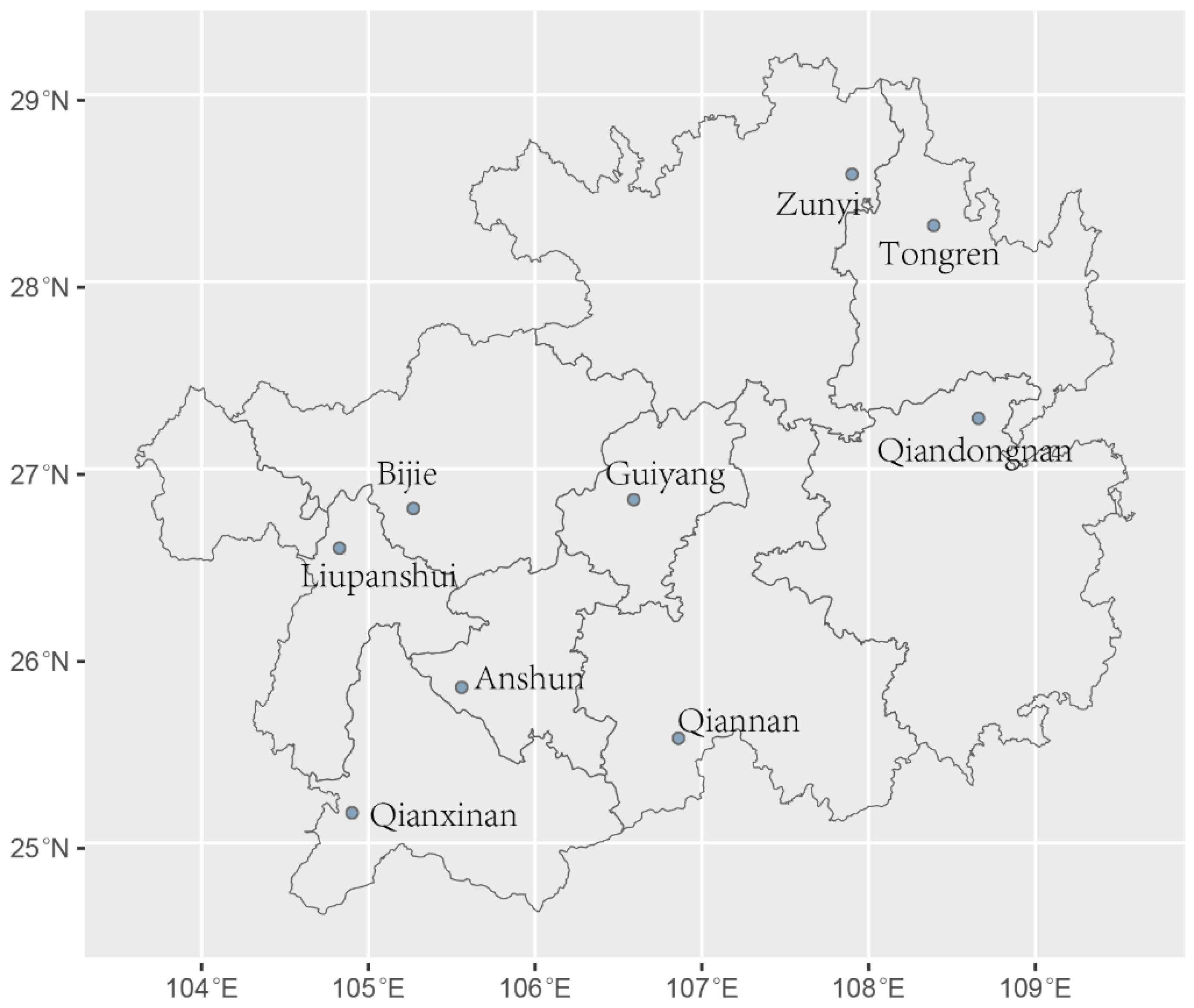

A total of 900 soil samples were collected from vegetable gardens at nine distinct locations in Guizhou Province between August 20 and September 1, 2023. At each sampling site, 100 subsamples (approximately 10 g each) were obtained from the topsoil layer (0–5 cm depth) and immediately placed into sterile zip-lock plastic bags for preservation. At each site, individual soil samples were about 1 m apart from each other. Detailed information regarding the sampling locations is provided in

Table S1 and Fig. 1. Isolation of

A. fumigatus was performed following the protocol described previously [

17]. Initial and final identification of the strains was conducted according to the methods reported in our prior studies [

29,

30].

2.2. STR Genotypes and Population Genetic Analyses

All

A. fumigatus isolates were genotyped using a panel of nine highly polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) markers (STRAf 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C, 4A, 4B, 4C) to elucidate the genetic relationships among strains and populations collected from vegetable gardens at nine locations in Guizhou Province. The number of tandem repeats at each STR locus was determined following the protocol described previously [

28]. Alleles at the nine STR loci were combined to generate a multilocus STR genotype for each

A. fumigatus strain. Additionally, genotypic data of

A. fumigatus isolates from other countries—previously reported and deposited in the STRAf database (

http://afumid.shinyapps.io/afumID)—were extracted and compared with the isolates obtained in Guizhou Province in the present study.

For population genetic analyses,

A. fumigatus isolates collected from each of the nine sampling sites were designated as members of a distinct local geographic population. GenAlEx v6.1 software was employed to calculate the levels of genetic diversity within and genetic differentiation among the nine geographic populations in Guizhou Province. In addition, the Guizhou population was compared with those from other parts of the world [

31]. Mantel test was performed to examine the correlation between genetic differentiation and geographical distances among the studied populations in Guizhou. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was used to estimate the relative contributions of geographic separation and different population subdivisions, as aforementioned, to the overall genetic variation. STRUCTURE v2.3.3 software was employed to infer the optimal number of genetic clusters (K) from two datasets: one consisting of the

A. fumigatus isolates from Guizhou Province, and the other a combined dataset incorporating all 750 global samples from a prior study [

32,

33,

34]. PCoA (Principal Coordinate Analysis) and DAPC (Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components) were used to investigate genetic relationships between

A. fumigatus isolates. MSTs (Minimum Spanning Trees) and an STR marker-based phylogenetic tree (implemented in the R adegenet package) were utilized to cluster genotypes in association with their geographic origins [

35]. MEGA v6 was used for sequence alignment of the

cyp51A gene [

36]. To investigate the reproductive mode of natural

A. fumigatus populations in Guizhou Province, three genetic indices—index of association (IA), rBarD, and proportion of phylogenetically compatible pairwise loci (PrC)—were calculated following the protocol described previously[

37].

2.3. Susceptibility of A. fumigatus isolates and cyp51A gene sequencing

Two clinical azole drugs (ITR and VOR) commonly used for the treatment of aspergillosis were used to test the susceptibility of

A. fumigatus isolated in this study following the methods described in the CLSI M38-A3 [

38] and our previous studies [

29,

30]. Two primer pairs, A7 (5'-TCATATGTTGCTCAGCGG-3') and P450-A2 (5'-CTGTCTCACTTGGATGTG-3') [

39] were used for amplifying and sequencing the full-length

cyp51A gene (encompassing coding and promoter regions) from ARAF strains isolated in this study.

3. Results

3.1. Genotyping of A. fumigatus Samples from Guizhou Province

In this study, 206 strains of

A. fumigatus were isolated from 900 soil samples collected from vegetable gardens at nine locations in Guizhou Province, China (

Figure 1,

Table S1). Based on genotyping at the nine STR loci, a total of 212 alleles and 161 multilocus genotypes were identified. The number of alleles per STR locus ranged from 10 (STRAF4C, uh = 0.68) to 52 (STRAF3A, uh = 0.96), with an average of 24. Among the 212 alleles, 155 were shared by at least two geographical populations, and the remaining 57 were found only in one geographical population each. Private alleles were detected in every geographical population, with the Bijie population (n = 12) having the highest number of private alleles and the Liupanshui population (n = 1) the lowest. Among the 161 multilocus genotypes, 2 were shared by two geographical populations, and the remaining 159 were found only in one geographical population each (

Table 1).

Genetic diversity analysis by population revealed the following results for the nine geographic populations of

A. fumigatus in Guizhou Province: the number of effective alleles (Ne) ranged from 5.132 (Anshun population) to 7.426 (Bijie population), with a mean of 6.087; Shannon’s Information Index (I) varied from 1.679 (Anshun population) to 2.026 (Qiandongnan population), with an average of 1.849; Simpson’s Diversity Index (h) spanned 0.731 (Guiyang population) to 0.835 (Qiandongnan population), with a mean of 0.783; and Unbiased Diversity (uh) ranged from 0.769 (Guiyang population) to 0.881 (Qiandongnan population), with an average of 0.830 (

Table 2).

3.2. Relationships Among Local Populations

Results of analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) based on clone-corrected data showed that 94% of the total genetic variation originated from within individual geographical populations. While the level of genetic differentiation among the nine geographical populations was modest (6%), this difference was statistically significant (PhiPT = 0.061, P = 0.001) (

Table S2). We additionally explored the degree of genetic differentiation between pairs of geographical populations. Our findings revealed that 30 of the 36 pairwise local populations showed statistically significant differentiation (P < 0.05). The greatest genetic differentiation was observed between Guiyang and Bijie populations (PhiPT = 0.128, P = 0.001), followed by that between Guiyang and Qiannan populations (PhiPT = 0.125, P = 0.001). The geographical populations from Qiannan and Bijie showed significant genetic differentiation from all other populations (P < 0.05) (

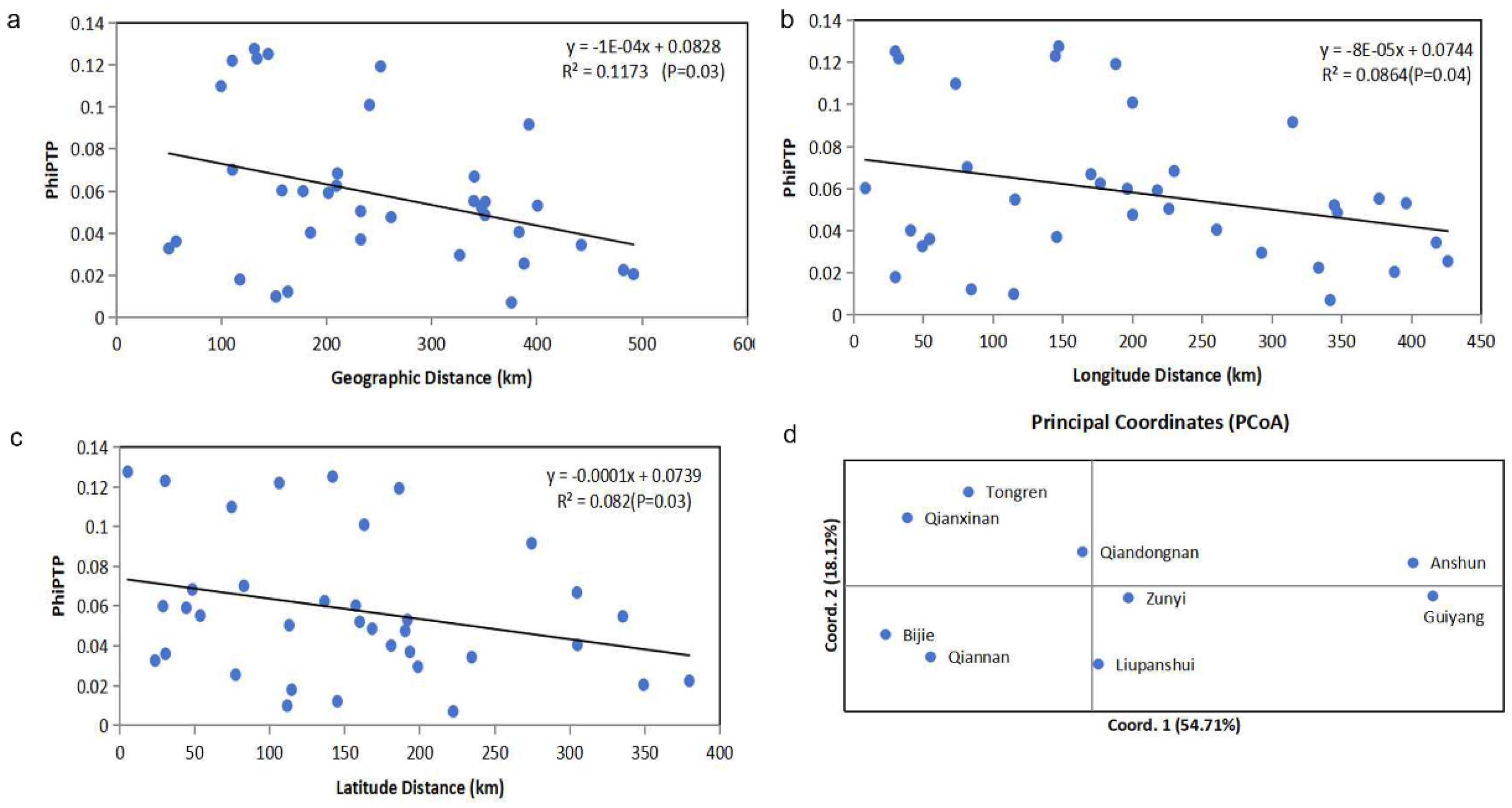

Table 3). Interestingly, Mantel test showed that genetic differentiations among geographic populations were negatively correlated with geographical distance (R² = 0.1173, P = 0.03) (

Figure 2a), longitude distance (R² = 0.0864, P = 0.04) (

Figure 2b), and latitude distance (R² = 0.082, P = 0.03) (

Figure 2c). Multilocus analysis results revealed limited but unambiguous evidence for recombination among the nine STR loci in the total sample, which included all 206

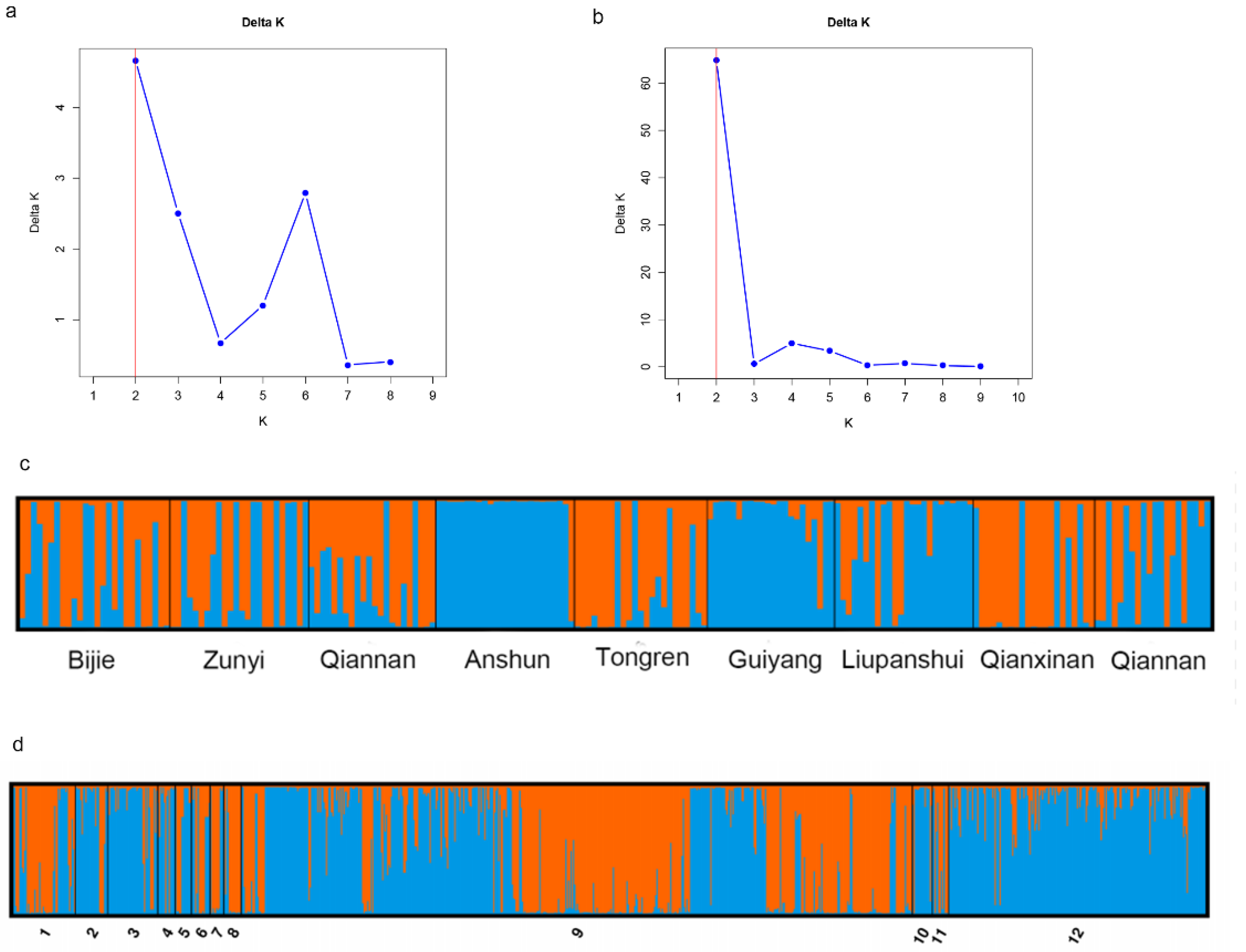

A. fumigatus isolates from Guizhou (PrC = 0, P = 1; rBarD = 0.079, P < 0.001). STRUCTURE analysis showed that there were two genetic clustering (K = 2) of

A. fumigatus from Guizhou (

Figure 3a). However, these two genetic clusters were not widely nor evenly distributed among the nine geographic populations. For example, isolates from Anshun and Guiyang populations mainly belonged to one cluster (blue), while isolates from populations in Qiannan, Tongren, and Qianxinan mainly belonged to the other cluster (orange) (

Figure 3c). Principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed based on the mean population haploid genetic distance. The first principal coordinate (PC1) contributed 54.71% of the total variance, and the second (PC2) accounted for 18.12%. Together, these two coordinates explained 72.83% of the total genetic variation. As shown in (Fig 2d), populations from Anshun and Guiyang were clearly distinct from the other geographic populations.

The PhiPT values are shown at the bottom left half of the table while the corresponding p values are shown at the top right half of the table.

3.3. Relationship between the Guizhou Population of A. fumigatus and Those in other Global Regions

To further investigate the relationship between

A. fumigatus samples from Guizhou and those from other regions around the world, we downloaded the information of 750

A. fumigatus samples from previous studies from the database (

https://afumid.shinyapps.io/afumID/), including their sources and the genotype data at the same nine STR loci. Therefore, a total of 956

A. fumigatus strains were used for analysis in this section, including 206 strains from Guizhou and 750 strains from other regions worldwide. Based on their geographical origins, the 956 strains were divided into 12 geographical populations. Using the nine STR loci, we identified a total of 322 alleles, among which 197 alleles were shared between the Guizhou samples and other geographic populations. Of the remaining 125 alleles, 15 and 110 alleles were unique to the Guizhou population and the global populations, respectively (

Table 4). A total of 838 multilocus genotypes were found from the 956

A. fumigatus strains. However, there was no shared multilocus genotype between Guizhou and other global geographic populations.

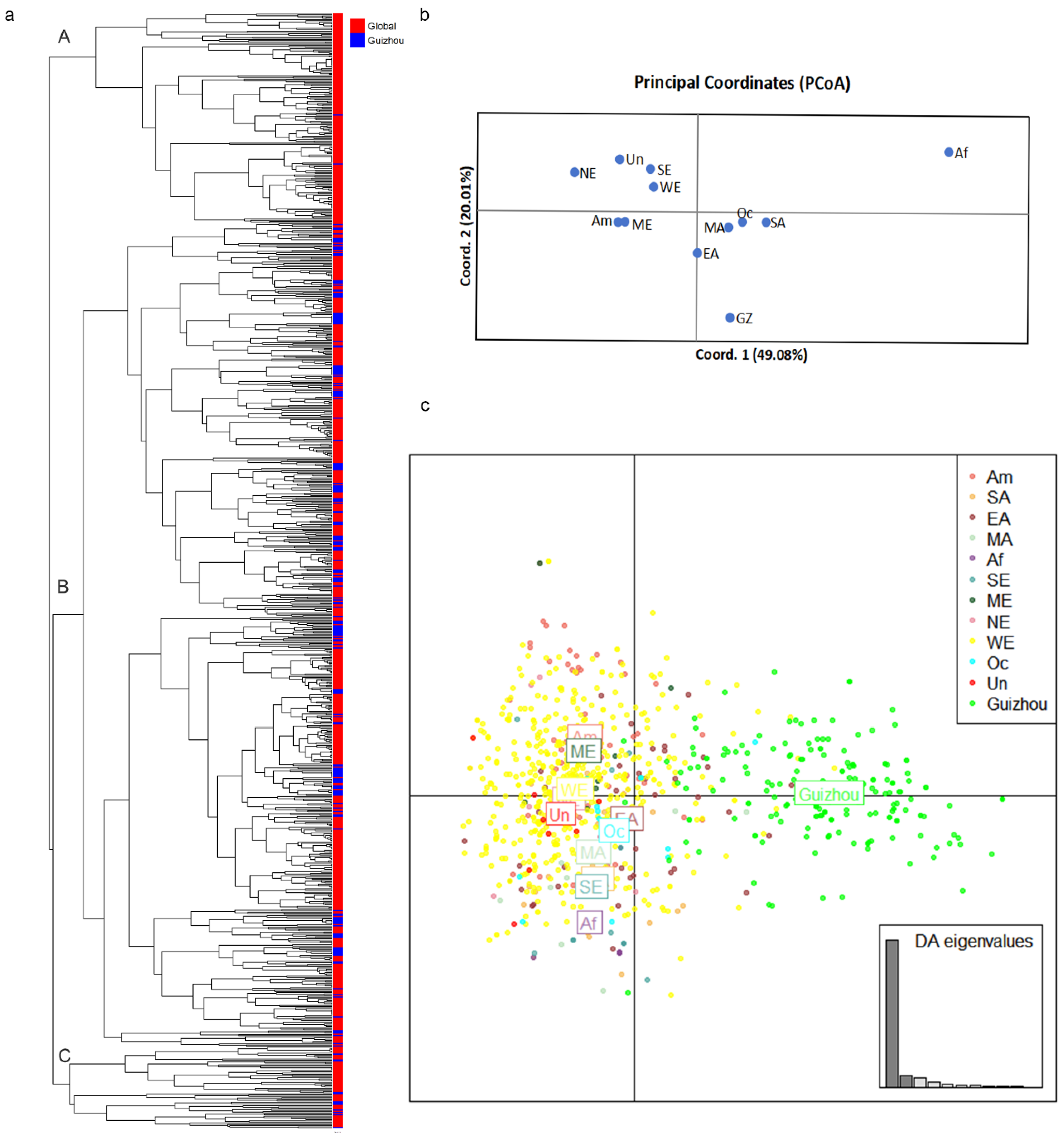

Pairwise population analysis results revealed that among the 66 population pairs, 54 pairs exhibited statistically significant genetic differentiation (p < 0.05). Notably, the Guizhou population showed significant differentiation from all other geographic populations (p = 0.001). This finding was consistent with the results of the population structure analysis (

Figure 3d). Specifically, the Northern Europe population displayed the highest degree of genetic differentiation from the Guizhou population (PhiPT = 0.114, P = 0.001), while the East Asian population that is geographically close to Guizhou showed the lowest degree of differentiation (PhiPT = 0.049, P = 0.001) (

Table S3). Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) results demonstrated that at a large geographical scale,

A. fumigatus populations from Asia, Europe, and Africa each formed distinct genetic clusters. At a smaller geographical scale, the Guizhou

A. fumigatus population was also distinguishable from those in East Asia, Central Asia, and South Asia (

Figure 4b). Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components (DAPC) results demonstrated that

A. fumigatus samples from Guizhou were primarily distributed on the right side of the coordinate plot, whereas the remaining global samples were predominantly localized on the left side (

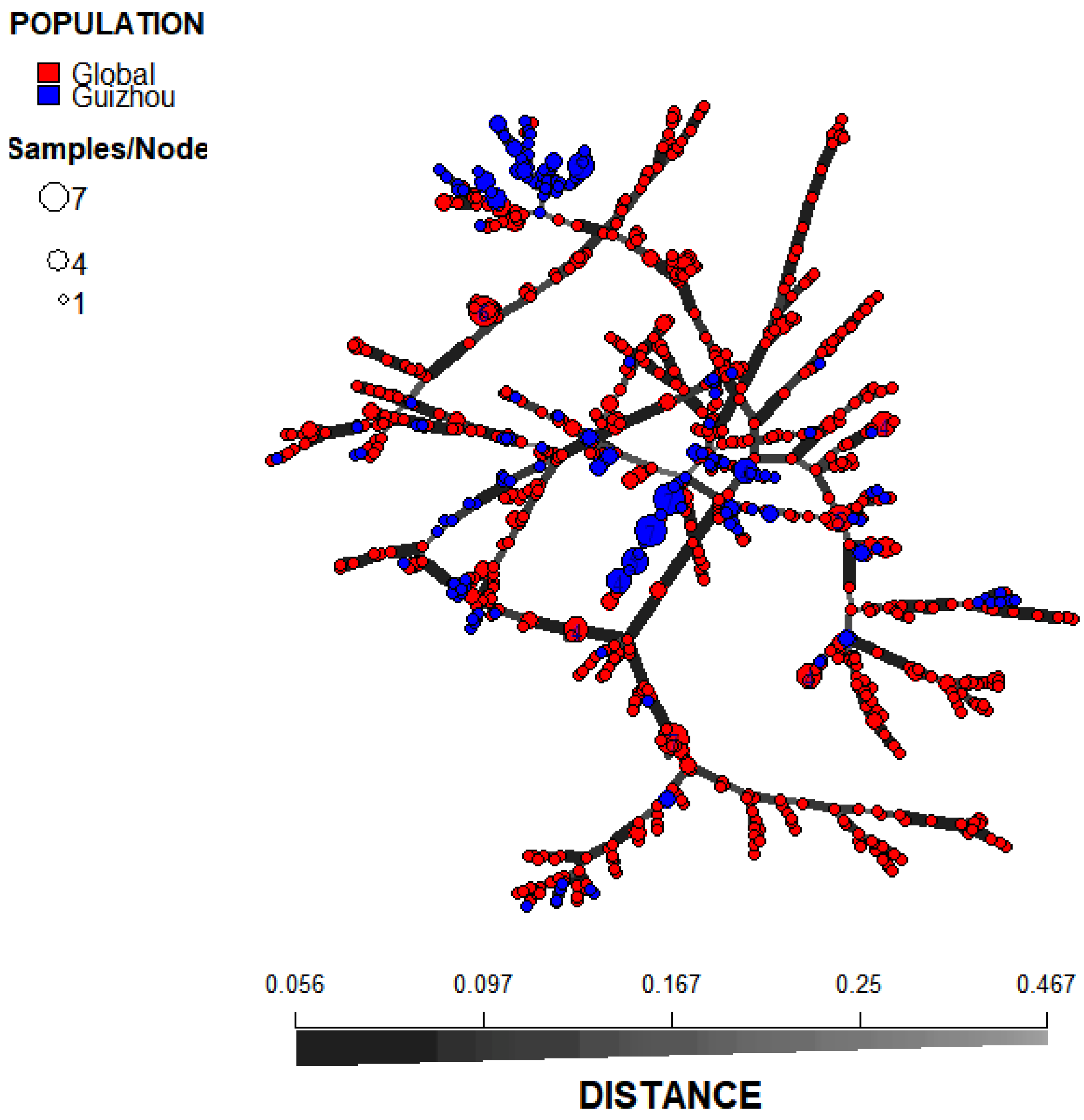

Figure 4c). The MSN results showed that the

A. fumigatus strains from Guizhou belonged to multiple independent lineages (

Figure 5). The results of phylogenetic analysis constructed based on Bruvo's distance indicated that the strains sampled from Guizhou and global reference strains were clustered into three distinct groups (A, B, and C). Specifically, among the Guizhou isolates, 2 strains fell into group A, 192 strains were assigned to group B, and 12 strains were grouped into group C (

Figure 4a). These findings indicated that the

A. fumigatus population from Guizhou contains both unique and shared genetic characteristics with those from other global samples.

3.4. Prevalence of Azole Resistance and cyp51A Mutation

The antifungal susceptibility test results showed that among 206 A. fumigatus strains from Guizhou, only one strain isolated from Zunyi was resistant to both itraconazole and voriconazole, with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ≥ 16.0 µg/ml for both antifungals. The remaining 205 strains were susceptible to both itraconazole and voriconazole. For the other strains, the MIC values of itraconazole ranged from 0.015 to 0.5 µg/ml, with an MIC50 of 0.063 µg/ml. The MIC values of voriconazole ranged from 0.031 to 0.25 µg/ml, with an MIC50 of 0.063 µg/ml. We amplified and obtained the cyp51A gene and promoter sequences of the one azole-resistant A. fumigatus strain using specific primers. The alignment results revealed the one azole-resistant A. fumigatus strain belonged to the TR34/L98H mutation type.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we isolated and identified 206 strains of A. fumigatus from soil samples collected from nine sites in Guizhou Province, China. Nine STR markers were employed to identify the genotypes of these isolates, as well as to analyze both the intra-population genetic diversity and inter-population relationships of the species. Our study found that the samples from the nine sites in Guizhou exhibited high levels of genetic diversity and genetic differentiation, with Unbiased Diversity (uh) and the PhiPT values being 0.830 and 0.061 (P = 0.001), respectively. Interestingly, among the nine sampling sites, only one ARAF strain was identified in Zunyi. The azole resistance frequency of A. fumigatus strains isolated from nine vegetable gardens in Guizhou was 0.49% (1/206), far lower than previous reports from other provinces in China. A comparative analysis was further performed between the A. fumigatus strains isolated in this study and publicly available global strains. The results indicated that Guizhou-derived A. fumigatus exhibits both distinct characteristics and shared traits with isolates from other geographical regions.

4.1. Extensive Novel Genetic Diversity in Guizhou Province

Our previous studies showed extensive genetic uniqueness and high genetic diversity in

A. fumigatus populations isolated from greenhouses, outdoor environments and the Three Parallel Rivers (TPR) region across Yunnan, a neighboring province west of Guizhou [

29,

30,

40]. In the present study, high levels of genetic diversity were also detected within and among nine distinct

A. fumigatus populations in Guizhou Province. For instance, when examining the same nine STR loci, the number of private alleles and unique genotypes from the nine local populations in Guizhou Province was 57 and 159, respectively, accounting for 26.9% (57/212) of the total number of alleles and 98.8% (159/161) of the total number of genotypes, and all nine local populations had private alleles (

Table 1). By comparing the results of these four studies, we found that both the proportions of private alleles and location-specific genotypes within local populations in Guizhou were the highest, followed by those from Yunnan's greenhouses (19.2% and 97%, respectively) [

30] and the Three Parallel Rivers (TPR) region (19.1% and 98.8%, respectively) [

40], while the population from Yunnan's outdoor populations had the lowest (16.2% and 94.1%, respectively) [

29]. The overall genetic diversity of samples from Guizhou (uh = 0.83) was slightly higher than that from Yunnan's outdoor environments (uh = 0.827) [

29] and the Three Parallel Rivers region (uh = 0.751) [

40]. Additionally, comparison with the global AfumID database revealed that the Guizhou populations possessed 15 unique alleles and did not share any genotypes. These findings are consistent with previous studies on the genetic diversity of

A. fumigatus in other regions worldwide, which all identified a large number of novel alleles and substantial genotypic diversity [

17,

41,

42,

43].

The presence of many private alleles and unique genotypes among the nine geographical populations of

A. fumigatus in Guizhou might be attributed to the following reasons. First, evidence of sexual reproduction was found both within and between the nine geographical populations, which was conducive to maintaining the genetic diversity of

A. fumigatus [

41]. Second, evidence showed that gene flow existed among the

A. fumigatus populations in Guizhou. Although this gene flow was limited between certain population pairs, it likely contributed to the genetic diversity of the local

A. fumigatus populations [

40]. Third, the high diversity might be associated with the generally mild climatic conditions in Guizhou, as well as the soil physicochemical properties under the karst landform. The high genetic diversity of

A. fumigatus in Guizhou was consistent with the findings of previous studies on other plants and animals. For example, He S et al. conducted a study on

Rhododendron pudingense in Guizhou Province and found that the species exhibit a high level of genetic diversity with observed heterozygosity (Ho) and expected heterozygosity (He) were 0.45 and 0.77, respectively [

44]. Liu Y et al. conducted a study on seven Chinese indigenous chicken populations in Guizhou Province and found that the genetic diversity of these Guizhou breeds was higher than that of commercial breeds, with observed heterozygosity (Ho) ranging from 0.315 to 0.346 and expected heterozygosity (He) ranging from 0.318 to 0.338 [

45].

In our present study, the genetic diversity of A. fumigatus populations in most local populations were higher than those of other organisms. For example, the two geographic populations with the lowest unbiased allelic diversity in Guizhou were from Guiyang and Anshun, at 0.769 and 0.788 respectively. These two populations exhibit significant genetic differentiation from other geographical groups within Guizhou. These two sampling sites both had sandy soils. We hypothesize that nutrient deficiency in sandy soil may have restricted the growth and reproduction of A. fumigatus, thereby reducing population density, impeding gene flow, and accelerating genetic differentiation.

4.2. High Level of genetic Differentiation Among the Nine Geographical Populations

In this study, 83.3% (30/36) of pairwise comparisons between nine vegetable garden populations revealed significant genetic differentiation (P < 0.05). Overall, about 6% of the total genetic variation was attributed to among the geographic populations. The proportion of genetic variation among populations relative to the total variation was higher than that from Yunnan's outdoor environments (4%) [

29], and the Three Parallel Rivers region (4%) [

40], and Yunnan's greenhouses (2%) [

30] , and equally higher than that reported recently in clinical and environmental samples from Yunnan (5%) [

3]. Interestingly, we also found that the genetic differentiation of samples from nine vegetable gardens in Guizhou (PhiPT = 0.061) was higher than that of those from Yunnan's greenhouses (PhiPT=0.019) [

30], and Yunnan's outdoor environments (PhiPT = 0.044) [

29], and the Three Parallel Rivers (TPR) region (PhiPT = 0.015) [

40] , as well as higher than that of the recently published clinical and environmental isolates from Yunnan (PhiPT = 0.045) [

3]. Both PCoA and DAPC results showed that the strains from Guizhou were clustered differently from most other geographic populations from AfumID. In addition, phylogenetic tree analysis based on Bruvo's distance revealed that

A. fumigatus populations from Guizhou and global samples were clustered into three clades. Only 2 isolates belonged to Clade A, 12 isolates were clustered in Clade C, and the remaining isolates fell into Clade B. This result was inconsistent with previous findings that samples from Yunnan and global isolates formed two clades [

29,

30,

40], indicating the uniqueness of Guizhou isolates.

Interestingly, we found that the observed genetic differentiations among

A. fumigatus populations in Guizhou showed a significant negative correlation with geographic distance (

Figure 2a), longitude distance (

Figure 2b), and latitude distance (

Figure 2c). The above findings are puzzling and the following reasons could have contributed to some of the observations. First, Guizhou features a typical conical karst landscape with dense peak forests, which restricts the air-borne dispersion and diffusion of

A. fumigatus conidia under natural conditions. Second, historically, Guizhou has long been isolated and underdeveloped with extremely inconvenient transportation, resulting in restricted dispersals due to human activities. Consequently, the conidia of

A. fumigatus were likely not dispersed in a geographic distance dependent manner. Third, Guizhou Province is located in a low-latitude mountainous area with significant topographic relief, where the elevation difference between the eastern and western regions exceeds 2,500 meters. As the terrain gradually raised from east to west, various meteorological elements exhibited distinct variations, giving rise to diverse microenvironments. Such heterogeneous habitats may have facilitated the genetic diversification and adaptive evolution of

A. fumigatus populations in this region. Similarly, in the study of

Rhododendron bailiense in this region, a relatively high level of genetic differentiation among populations was observed, with a genetic differentiation coefficient (Fst) of 0.1907 [

46]. However, at present, the exact reason(s) for the negative correlation between genetic differentiation and geographic distance is unknown. For example, there is no known migration corridor such as rivers or highway systems that specifically connect the least differentiated but geographically distant populations such as between Zunyi and Liupanshui or between Qianxinan and Tongren. Furthermore, neither altitude nor types of vegetable crops were correlated with the observed genetic differences. Additional samples from these geographic regions are needed to critically assess the potential underlying causes for the observed negative correlations.

4.3. Low Level of Azole Resistance

In this study, we found that the incidence of azole resistance in

A .fumigatus isolated from nine sites in Guizhou was only 0.49% (1/206), which was significantly lower than that in our previous studies conducted in neighboring Yunnan Province [

29,

30,

40] and other parts of China [

47]. On a global scale, although a similarly low rate of triazole-resistance was reported in the Canadian soil populations of

A. fumigatus [

48], the currently reported azole resistance rates of

A. fumigatus populations in most geographic regions are a lot higher, up to 50% outside of China [

49,

50,

51]. The relatively low incidence of azole resistance in

A.

fumigatus from Guizhou is likely attributed to the following factors: First, the local government has vigorously promoted green agriculture and strictly regulated the use of pesticides. Second, influenced by traditional farming concepts, farmers generally apply little or no pesticides (including triazoles) in agricultural production activities in their own vegetable gardens to safeguard personal health. Third, it may be associated with Guizhou’s temperature conditions: the average summer temperature in Guizhou is around 24°C, and the annual average temperature is approximately 15°C. Low temperatures restrict the growth and reproduction of plant pathogenic fungi, thereby reducing the occurrence of fungal diseases and subsequently lowering the frequency of pesticide application by farmers. Fourth, our research revealed that highly limited gene flow in the Guizhou region had constrained the transmission of azole resistance genes through restricted genetic exchange.

It has been reported in the literature that in the 1970s, demethylation inhibitor (DMI) fungicides began to be extensively used in agricultural production for controlling plant fungal diseases [

52]. Approximately a decade later, the TR34/L98H mutation at the

cyp51A gene was first reported in

A. fumigatus in the Netherlands [

53]. To date, it has been reported in many countries across all five continents worldwide [

42,

54,

55,

56,

57]. In China, the TR34/L98H mutation in clinical

A. fumigatus isolates was first reported in 2011 [

58]. Subsequently, this mutation type has been identified in multiple provinces [

30,

59]. Based on existing literature reports, TR34/L98H is the most prevalent mutation type detected in environmental samples across China [

29,

30,

40,

47,

59]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the TR34/L98H mutation in environmental samples from the karst region of Guizhou, China. Regardless of the mechanisms, the low frequency of triazole resistance of

A. fumigatus in Guizhou compared to other regions in China suggest that the approaches taken by Guizhou represent a potentially excellent example from which to develop broader strategies to limit the origins and spread of triazole resistance in this fungal pathogen [

16].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Table S1: Detailed information of the nine sampling sites in Guizhou; Table S2: Results of AMOVA among nine geographic populations of the A. fumigatus isolates from Guizhou; Table S3: Genetic differentiations between continental and regional geographical populations of

A. fumigatus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and J.X.; methodology, Z.D. and Y.L.; software, Z.D. and Y.L.; validation, Y.Z., and J.X.; formal analysis, Z.D. and Y.L.; investigation, Z.D. and Q. Z.; resources, Z.D. and Y.L.; data curation, Z.D. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.D.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and J.X.; visualization, Y.Z. and J.X.; supervision, Y.Z. and J.X.; project administration, Z.D. and J.X.; funding acquisition, Z.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Guizhou provincial science and technology projects (No. 2022-563), Science and Technology Platform of Qianxinan Prefecture (No. 2024-2), Doctoral Startup Fund Project of Minzu Normal University of Xingyi (No. 24XYRC02), University-Level Key Project of Minzu Normal University of Xingyi (No. 21XYZD06), Innovation Team Project of Institutions of Higher Education in Guizhou Province (No. 2023-095).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| STRs |

Short Tandem Repeats |

| ARAF |

azole-resistant A. fumigatus |

| ITR |

itraconazole |

| VOR |

voriconazole |

| MIC |

minimum inhibitory concentration |

References

- Latgé, J.-P.; Chamilos, G. Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillosis in 2019. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2019, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doughty, K.J.; Sierotzki, H.; Semar, M.; Goertz, A. Selection and Amplification of Fungicide Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus in Relation to DMI Fungicide Use in Agronomic Settings: Hotspots versus Coldspots. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y. Unveiling environmental transmission risks: Comparative analysis of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus clinical and environmental isolates from Yunnan, China. Microbiology Spectrum 2024, 12, e01594-01524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordana, N.; Johnson, A.; Quinn, K.; Obar, J.J.; Cramer, R.A. Recent developments in Aspergillus fumigatus research: Diversity, drugs, and disease. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2025, 89, e00011-00023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedmousavi, S.; Guillot, J.; Arné, P.; de Hoog, G.S.; Mouton, J.W.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Verweij, P.E. Aspergillus and aspergilloses in wild and domestic animals: A global health concern with parallels to human disease. Medical Mycology 2015, 53, 765–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, B.H.; Romani, L.R. Invasive aspergillosis in chronic granulomatous disease. Medical Mycology 2009, 47, S282–S290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K.; Strek, M.E. Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 2010, 7, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashu, E.E.; Hagen, F.; Chowdhary, A.; Meis, J.F.; Xu, J. Global Population Genetic Analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus. mSphere 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, J.W.M.; Snelders, E.; Kampinga, G.A.; Rijnders, B.J.A.; Mattsson, E.; Debets-Ossenkopp, Y.J.; Kuijper, E.J.; Van Tiel, F.H.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Verweij, P.E. Clinical Implications of Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus, the Netherlands, 2007–2009. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2011, 17, 1846–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroczyńska, M.; Kurzyk, E.; Śliwka-Kaszyńska, M.; Nawrot, U.; Adamik, M.; Brillowska-Dąbrowska, A. The Effect of Posaconazole, Itraconazole and Voriconazole in the Culture Medium on Aspergillus fumigatus Triazole Resistance. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W.; Radford, S.A.; Oakley, K.L.; Hall, L.; Johnson, E.M.; Warnock, D.W. Correlation between in-vitro susceptibility testing to itraconazole and in-vivo outcome of Aspergillus fumigatus infection. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 1997, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Paassen, J.; Russcher, A.; Veld - van Wingerden, A.W.M.; Verweij, P.E.; Kuijper, E.J. Emerging aspergillosis by azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus at an intensive care unit in the Netherlands, 2010 to 2013. Eurosurveillance 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrissey, C.O.; Kim, H.Y.; Duong, T.-M.N.; Moran, E.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Denning, D.W.; Perfect, J.R.; Nucci, M.; Chakrabarti, A.; Rickerts, V.; et al. Aspergillus fumigatus—A systematic review to inform the World Health Organization priority list of fungal pathogens. Medical Mycology 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, G.; Lin, H.; Guo, J.; Deng, S.; Wu, W.; Goldman, G.H.; Lu, L.; Zhang, Y. Variability in competitive fitness among environmental and clinical azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. mBio 2024, 15, e00263-00224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Verweij, P.E. Aspergillus fumigatus and pan-azole resistance: Who should be concerned? Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 2020, 33, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, L.; Gong, J.; Liu, L.; Miao, B.; Xu, J. Research advances and public health strategies in China on WHO priority fungal pathogens. Mycology 2025, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korfanty, G.A.; Dixon, M.; Jia, H.; Yoell, H.; Xu, J. Genetic Diversity and Dispersal of Aspergillus fumigatus in Arctic Soils. Genes 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, L.; Aerts, R.; Van de gaer, O.; Vinken, L.; Merckx, R.; Gerils, V.; Vande Velde, G.; Reséndiz-Sharpe, A.; Maertens, J.; Lagrou, K. Doubling of triazole resistance rates in invasive aspergillosis over a 10-year period, Belgium, 1 April 2022 to 31 March 2023. Eurosurveillance 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, P.E.; Arendrup, M.C.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Gold, J.A.W.; Lockhart, S.R.; Chiller, T.; White, P.L. Dual use of antifungals in medicine and agriculture: How do we help prevent resistance developing in human pathogens? Drug Resistance Updates 2022, 65, 100885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Castlebury, L.A.; Miller, A.N.; Huhndorf, S.M.; Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Rossman, A.Y.; Rogers, J.D.; Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. An overview of the systematics of the Sordariomycetes based on a four-gene phylogeny. Mycologia 2006, 98, 1076–1087. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20444795. [CrossRef]

- Baiping, Z.; Fei, X.; Hongzhi, W.; Shenguo, M.; Shouqian, Z.; Lifei, Y.; Kangning, X.; Anjun, L. Combating the Fragile Karst Environment in Guizhou, China. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment. 2006, 35, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xiong, K.; Li, B.; Tian, Z.; Chen, Q.; Yan, L.; Xiao, S. The spatial distribution and factors affecting karst cave development in Guizhou Province. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2017, 27, 1011–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Luo, J.; Niu, S.; Bai, D.; Chen, Y. Population structure analysis to explore genetic diversity and geographical distribution characteristics of wild tea plant in Guizhou Plateau. BMC Plant Biology 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, H.; Wei, X.; Qi, Y.; Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Ding, L.; Tang, S.; Qiu, Z.E.; Cao, Y.; et al. Genetic structure and diversity of Oryza sativa L. in Guizhou, China. Chinese Science Bulletin 2007, 52, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, X.; Lu, J.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Qu, L.; et al. Analysis of genetic diversity and genetic structure of indigenous chicken populations in Guizhou province based on genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism markers. Poultry Science 2024, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.y.; Zhi, J.r.; Zhou, Y.f.; Meng, Z.h.; Wen, J. Population genetic structure and migration patterns of Dendrothrips minowai (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in Guizhou, China. Entomological Science 2017, 20, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-F.; Liu, J.-K.; Hyde, K.D.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Ran, H.-Y.; Liu, Z.-Y. Ascomycetes from karst landscapes of Guizhou Province, China. Fungal Diversity 2023, 122, 1–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Valk, H.A.; Meis, J.F.G.M.; Curfs, I.M.; Muehlethaler, K.; Mouton, J.W.; Klaassen, C.H.W. Use of a Novel Panel of Nine Short Tandem Repeats for Exact and High-Resolution Fingerprinting of Aspergillus fumigatus Isolates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2005, 43, 4112–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Peng, B.; Yang, G.; Zhang, K.-Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J. Genetic Diversity and Azole Resistance Among Natural Aspergillus fumigatus Populations in Yunnan, China. Microbial Ecology 2021, 83, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Korfanty, G.A.; Mo, M.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Wu, J.-Y.; Zhang, K.-Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Extensive Genetic Diversity and Widespread Azole Resistance in Greenhouse Populations of Aspergillus fumigatus in Yunnan, China. mSphere 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—An update. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HUBISZ, M.J.; FALUSH, D.; STEPHENS, M.; PRITCHARD, J.K. Inferring weak population structure with the assistance of sample group information. Molecular Ecology Resources 2009, 9, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Stephens, M.; Pritchard, J.K. fastSTRUCTURE: Variational Inference of Population Structure in Large SNP Data Sets. Genetics 2014, 197, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Liu, J.X. StructureSelector: A web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Molecular Ecology Resources 2017, 18, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombart, T.; Ahmed, I. adegenet 1.3-1: New tools for the analysis of genome-wide SNP data. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 3070–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agapow, P.M.; Burt, A. Indices of multilocus linkage disequilibrium. Molecular Ecology Notes 2001, 1, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi. In CLSI standard M38, 3rd ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, 2017; Available online: https://standards.globalspec.com/std/10266415/clsi-m38.

- Snelders, E.; Camps, S.M.T.; Karawajczyk, A.; Rijs, A.J.M.M.; Zoll, J.; Verweij, P.E.; Melchers, W.J.G. Genotype–phenotype complexity of the TR46/Y121F/T289A cyp51A azole resistance mechanism in Aspergillus fumigatus. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2015, 82, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Gong, J.; Duan, C.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J. Genetic structure and triazole resistance among Aspergillus fumigatus populations from remote and undeveloped regions in Eastern Himalaya. mSphere 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashu, E.E.; Korfanty, G.A.; Xu, J. Evidence of unique genetic diversity in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from Cameroon. Mycoses 2017, 60, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korfanty, G.A.; Teng, L.; Pum, N.; Xu, J. Contemporary Gene Flow is a Major Force Shaping the Aspergillus fumigatus Population in Auckland, New Zealand. Mycopathologia 2019, 184, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashu, E.E.; Kim, G.Y.; Roy-Gayos, P.; Dong, K.; Forsythe, A.; Giglio, V.; Korfanty, G.; Yamamura, D.; Xu, J. Limited evidence of fungicide-driven triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in Hamilton, Canada. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 2018, 64, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, P.; Wang, H.; Luo, D.; Dai, X. Study on the characteristics of genetic diversity of different populations of Guizhou endemic plant Rhododendron pudingense based on microsatellite markers. BMC Plant Biology 2024, 24, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tu, Y.; Zou, J.; Luo, K.; Ji, G.; Shan, Y.; Ju, X.; Shu, J. Population structure and genetic diversity of seven Chinese indigenous chicken populations in Guizhou Province. The Journal of Poultry Science 2021, 58, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Yuan, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; He, S.; Chen, M.; Dai, X.; Luo, D. Study on the Diversity Characteristics of the Endemic Plant Rhododendron bailiense in Guizhou, China Based on SNP Molecular Markers. Ecology and Evolution 2025, 15, e70966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Dong, F.; Zhao, J.; Fan, H.; Qin, C.; Li, R.; Verweij, P.E.; Zheng, Y.; Han, L. High azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from strawberry fields, China, 2018. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2020, 26, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korfanty, G.; Kazerouni, A.; Dixon, M.; Trajkovski, M.; Gomez, P.; Xu, J. What in Earth? Analyses of Canadian soil populations of Aspergillus fumigatus. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 2024, 71, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst, S.F.; Berkow, E.L.; Stevenson, K.L.; Litvintseva, A.P.; Lockhart, S.R. Isolation of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus from the environment in the south-eastern USA. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2017, 72, 2443–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amona, F.M.; Oladele, R.O.; Resendiz-Sharpe, A.; Denning, D.W.; Kosmidis, C.; Lagrou, K.; Zhong, H.; Han, L. Triazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates in Africa: A systematic review. Medical Mycology 2022, 60, myac059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigitano, A.; Esposto, M.C.; Romanò, L.; Auxilia, F.; Tortorano, A.M. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in the Italian environment. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 2019, 16, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisi, U. Assessment of selection and resistance risk for demethylation inhibitor fungicides in Aspergillus fumigatus in agriculture and medicine: A critical review. Pest management science 2014, 70, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzo-Gallo, P.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Chumbita, M.; Aiello, T.F.; Gallardo-Pizarro, A.; Peyrony, O.; Teijon-Lumbreras, C.; Alcazar-Fuoli, L.; Espasa, M.; Soriano, A. Report of three azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus cases with TR34/L98H mutation in hematological patients in Barcelona, Spain. Infection 2024, 52, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snelders, E.; van der Lee, H.A.L.; Kuijpers, J.; Rijs, A.J.M.; Varga, J.; Samson, R.A.; Mellado, E.; Donders, A.R.T.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Verweij, P.E. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS medicine 2008, 5, e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meis, J.F.; Chowdhary, A.; Rhodes, J.L.; Fisher, M.C.; Verweij, P.E. Clinical implications of globally emerging azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2016, 371, 20150460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, P.E.; Chowdhary, A.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Meis, J.F.; Weinstein, R.A. Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: Can We Retain the Clinical Use of Mold-Active Antifungal Azoles? Clinical Infectious Diseases 2016, 62, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Moreno, C.; Lavergne, R.-A.; Hagen, F.; Morio, F.; Meis, J.F.; Le Pape, P. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus harboring TR34/L98H, TR46/Y121F/T289A and TR53 mutations related to flower fields in Colombia. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 45631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockhart, S.R.; Frade, J.P.; Etienne, K.A.; Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J.; Balajee, S.A. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from the ARTEMIS global surveillance study is primarily due to the TR/L98H mutation in the cyp51A gene. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2011, 55, 4465–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zou, Z.; Gong, Y.; Qu, F.; Bao, Z.; Qiu, G.; Song, M.; Zhang, Q. Epidemiology and molecular characterizations of azole resistance in clinical and environmental Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from China. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2016, 60, 5878–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Detailed information of geographical distributions of Aspergillus fumigatus samples analyzed in this study.

Figure 1.

Detailed information of geographical distributions of Aspergillus fumigatus samples analyzed in this study.

Figure 2.

Results of Mantel test and PCoA. (a) Correlation analysis of genetic differentiation (PhiPTP) and geographical distance of A. fumigatus populations from Guizhou (P = 0.03). (b) Correlation analysis of genetic differentiation (PhiPTP) and longitude distance of A. fumigatus populations from Guizhou (P = 0.04). (c) Correlation analysis of genetic differentiation (PhiPTP) and latitude distance of A. fumigatus populations from Guizhou (P = 0.03). (d) Principal-coordinate analysis of the mean population haploid genetic distance among 9 geographical populations in Guizhou.

Figure 2.

Results of Mantel test and PCoA. (a) Correlation analysis of genetic differentiation (PhiPTP) and geographical distance of A. fumigatus populations from Guizhou (P = 0.03). (b) Correlation analysis of genetic differentiation (PhiPTP) and longitude distance of A. fumigatus populations from Guizhou (P = 0.04). (c) Correlation analysis of genetic differentiation (PhiPTP) and latitude distance of A. fumigatus populations from Guizhou (P = 0.03). (d) Principal-coordinate analysis of the mean population haploid genetic distance among 9 geographical populations in Guizhou.

Figure 3.

Genetic clustering results obtained from STRUCTURE analysis. Plot of K against delta K (a) and cluster assignments for isolates (c) for 9 geographic populations from Guizhou. Plot of K against delta K (b) and cluster assignments for isolates (d) based on data from 12 geographical populations from around the world, K=2. 1, America; 2, South Asia; 3, East Asia; 4, Middle Asia; 5, Africa; 6, South Europe; 7, Middle Europe; 8, North Europe; 9, West Europe; 10, Oceanica; 11, unclear regions; 12, Guizhou, China.

Figure 3.

Genetic clustering results obtained from STRUCTURE analysis. Plot of K against delta K (a) and cluster assignments for isolates (c) for 9 geographic populations from Guizhou. Plot of K against delta K (b) and cluster assignments for isolates (d) based on data from 12 geographical populations from around the world, K=2. 1, America; 2, South Asia; 3, East Asia; 4, Middle Asia; 5, Africa; 6, South Europe; 7, Middle Europe; 8, North Europe; 9, West Europe; 10, Oceanica; 11, unclear regions; 12, Guizhou, China.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analysis and results of PCoA and DAPC. (a) Phylogenetic analysis of isolates from 9 geographic populations in Guizhou and 11 geographic populations (Global) from outside of Guizhou. (b) Principal-coordinate analysis of the mean population haploid genetic distance among 9 geographical populations in Guizhou and 11 geographic populations from outside of Guizhou. (c) DAPC analysis of 12 global geographical populations of Aspergillus fumigatus, AM, America; SA, South Asia; EA, East Asia; MA, Middle Asia; Af, Africa; SE, South Europe; ME, Middle Europe; NE, North Europe; WE, West Europe; Oc, Oceania; UN, unclear regions; GZ, Guizhou, China.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analysis and results of PCoA and DAPC. (a) Phylogenetic analysis of isolates from 9 geographic populations in Guizhou and 11 geographic populations (Global) from outside of Guizhou. (b) Principal-coordinate analysis of the mean population haploid genetic distance among 9 geographical populations in Guizhou and 11 geographic populations from outside of Guizhou. (c) DAPC analysis of 12 global geographical populations of Aspergillus fumigatus, AM, America; SA, South Asia; EA, East Asia; MA, Middle Asia; Af, Africa; SE, South Europe; ME, Middle Europe; NE, North Europe; WE, West Europe; Oc, Oceania; UN, unclear regions; GZ, Guizhou, China.

Figure 5.

Minimum spanning tree (MST) showing the genotypic relationship among Global populations, including America, South Asia, East Asia, Middle Asia, Africa, South Europe, Middle Europe, North Europe, West Europe, Oceania, unclear regions and Guizhou, China.

Figure 5.

Minimum spanning tree (MST) showing the genotypic relationship among Global populations, including America, South Asia, East Asia, Middle Asia, Africa, South Europe, Middle Europe, North Europe, West Europe, Oceania, unclear regions and Guizhou, China.

Table 1.

Detailed information of geographical distributions and STR alleles of A. fumigatus isolates from Guizhou Province, China.

Table 1.

Detailed information of geographical distributions and STR alleles of A. fumigatus isolates from Guizhou Province, China.

| Population |

No. of strains |

No. of genotypes |

Microsatellite loci and number of alleles(private alleles) |

| 2A |

2B |

2C |

3A |

3B |

3C |

4A |

4B |

4C |

Total |

| Guiyang |

22 |

20 |

10 |

8(1) |

10 |

17(6) |

6 |

7 |

4 |

7(1) |

4 |

73(8) |

| Zunyi |

24 |

15 |

8 |

12(1) |

12(2) |

10(2) |

11(2) |

10(2) |

7(1) |

5 |

5 |

80(10) |

| Qiannan |

22 |

22 |

9 |

6 |

11 |

13(1) |

9 |

10(2) |

9(2) |

5 |

5(1) |

77(6) |

| Anshun |

24 |

17 |

7 |

6 |

9 |

15(3) |

6 |

7(2) |

5(1) |

8 |

6 |

69(6) |

| Qiandongnan |

20 |

19 |

10 |

9 |

9(1) |

16(3) |

10 |

10 |

6(1) |

9(1) |

6 |

85(6) |

| Qianxinan |

21 |

14 |

7 |

8 |

7 |

10(3) |

8 |

11(1) |

6 |

5(1) |

3 |

65(5) |

| Liupanshui |

24 |

17 |

8 |

7(1) |

10 |

15 |

12 |

11 |

4 |

6 |

5 |

78(1) |

| Bijie |

26 |

23 |

8 |

9(1) |

13(1) |

20(3) |

11(1) |

16(5) |

10(1) |

4 |

4 |

95(12) |

| Tongren |

23 |

16 |

6(1) |

8 |

10(2) |

11 |

9 |

13 |

8 |

6 |

4 |

75(3) |

| Total |

206 |

161 |

16(1) |

18(4) |

26(6) |

52(21) |

23(3) |

36(12) |

18(6) |

13(3) |

10(1) |

212(57) |

Table 2.

Summary genetic diversities of Aspergillus fumigatus populations from Guizhou Province, China.

Table 2.

Summary genetic diversities of Aspergillus fumigatus populations from Guizhou Province, China.

| Sampling site |

Effective alleles

(Ne) |

Shannon's Information Index (I) |

Diversity

(h) |

Unbiased Diversity

(uh) |

| Bijie |

7.426 |

1.982 |

0.789 |

0.825 |

| Zunyi |

6.543 |

1.963 |

0.822 |

0.88 |

| Qiannan |

5.426 |

1.807 |

0.775 |

0.813 |

| Anshun |

5.132 |

1.679 |

0.732 |

0.778 |

| Tongren |

5.984 |

1.88 |

0.806 |

0.86 |

| Guiyang |

5.695 |

1.711 |

0.731 |

0.769 |

| Liupanshui |

6.068 |

1.85 |

0.785 |

0.834 |

| Qianxinan |

5.414 |

1.741 |

0.771 |

0.83 |

| Qiandongnan |

7.099 |

2.026 |

0.835 |

0.881 |

Table 3.

Pairwise differentiations among 9 geographical populations of Aspergillus fumigatus in Guizhou.

Table 3.

Pairwise differentiations among 9 geographical populations of Aspergillus fumigatus in Guizhou.

| Bijie |

Zunyi |

Qiannan |

Anshun |

Tongren |

Guiyang |

Liupanshui |

Qianxinan |

Qiandongnan |

|

| |

0.009 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.002 |

0.001 |

0.013 |

0.003 |

0.001 |

Bijie |

| 0.030 |

|

0.002 |

0.007 |

0.009 |

0.006 |

0.264 |

0.078 |

0.158 |

Zunyi |

| 0.062 |

0.055 |

|

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.005 |

0.002 |

0.001 |

Qiannan |

| 0.122 |

0.041 |

0.123 |

|

0.001 |

0.204 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

Anshun |

| 0.049 |

0.036 |

0.067 |

0.092 |

|

0.001 |

0.003 |

0.110 |

0.101 |

Tongren |

| 0.128 |

0.037 |

0.125 |

0.010 |

0.101 |

|

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

Guiyang |

| 0.033 |

0.007 |

0.050 |

0.070 |

0.053 |

0.060 |

|

0.002 |

0.031 |

Liupanshui |

| 0.040 |

0.022 |

0.059 |

0.110 |

0.021 |

0.119 |

0.060 |

|

0.015 |

Qianxinan |

| 0.055 |

0.012 |

0.048 |

0.052 |

0.018 |

0.068 |

0.026 |

0.034 |

|

Qiandongnan |

Table 4.

Summary allelic richness at the nine STR loci for population of Aspergillus fumigatus from Guizhou and comparison with those in the global population.

Table 4.

Summary allelic richness at the nine STR loci for population of Aspergillus fumigatus from Guizhou and comparison with those in the global population.

| Locus |

No. of alleles in all 12 populations |

No. of alleles

in Guizhou |

Private alleles in Guizhou

(Frequency of Private) |

| STRAF2A |

19 |

16 |

None |

| STRAF2B |

25 |

18 |

6 (0.005), 31 (0.005) |

| STRAF2C |

30 |

26 |

6 (0.015), 7 (0.049), 29 (0.005), 30 (0.005) |

| STRAF3A |

86 |

52 |

64 (0.005), 104 (0.005), 106 (0.015), 107 (0.005) |

| STRAF3B |

33 |

23 |

None |

| STRAF3C |

49 |

36 |

35 (0.005), 38 (0.005) |

| STRAF4A |

26 |

18 |

3(0.02) |

| STRAF4B |

25 |

13 |

18 (0.005), 21 (0.005) |

| STRAF4C |

29 |

10 |

None |

| Total |

322 |

212 |

15 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).