Submitted:

06 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

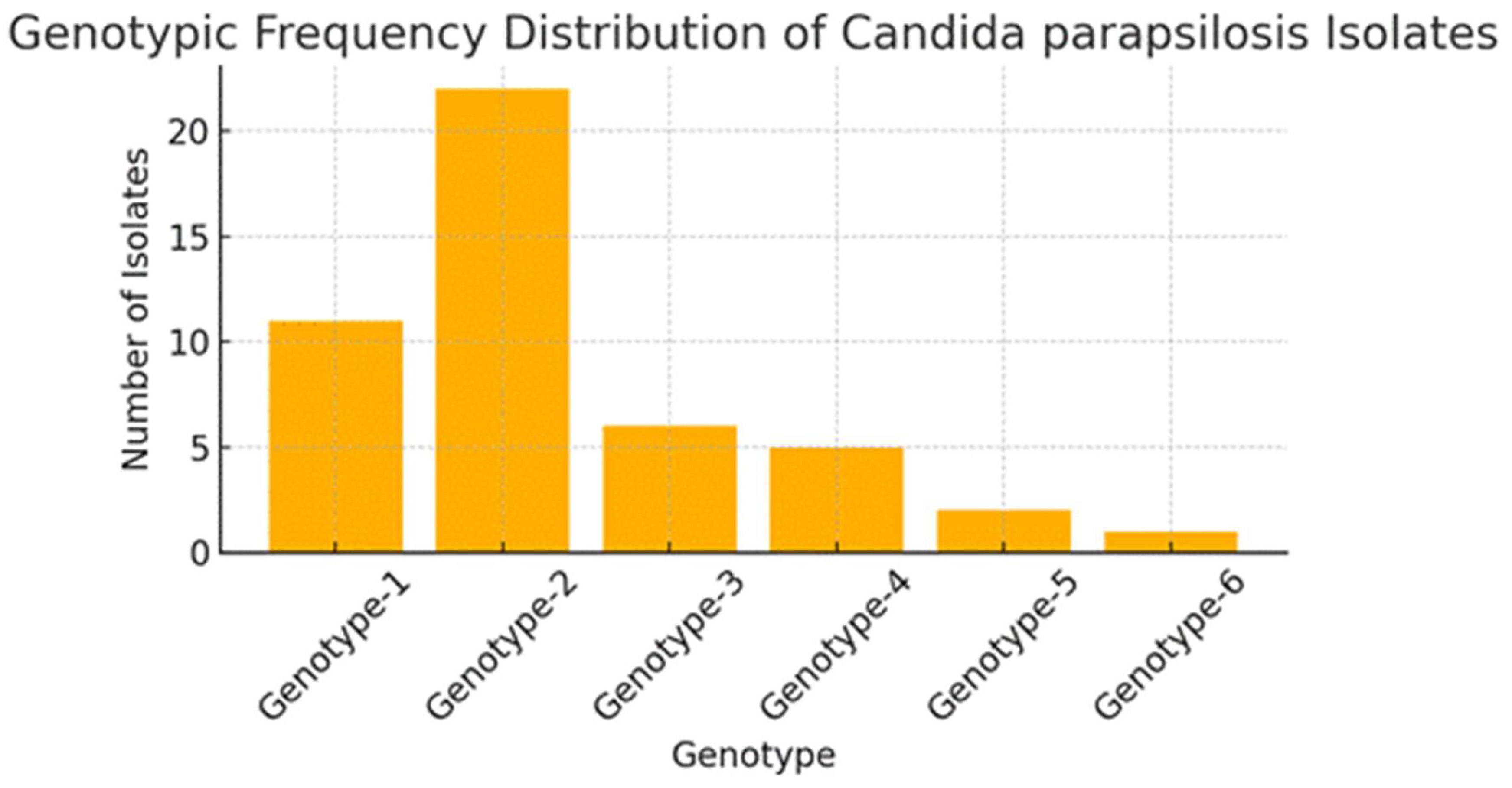

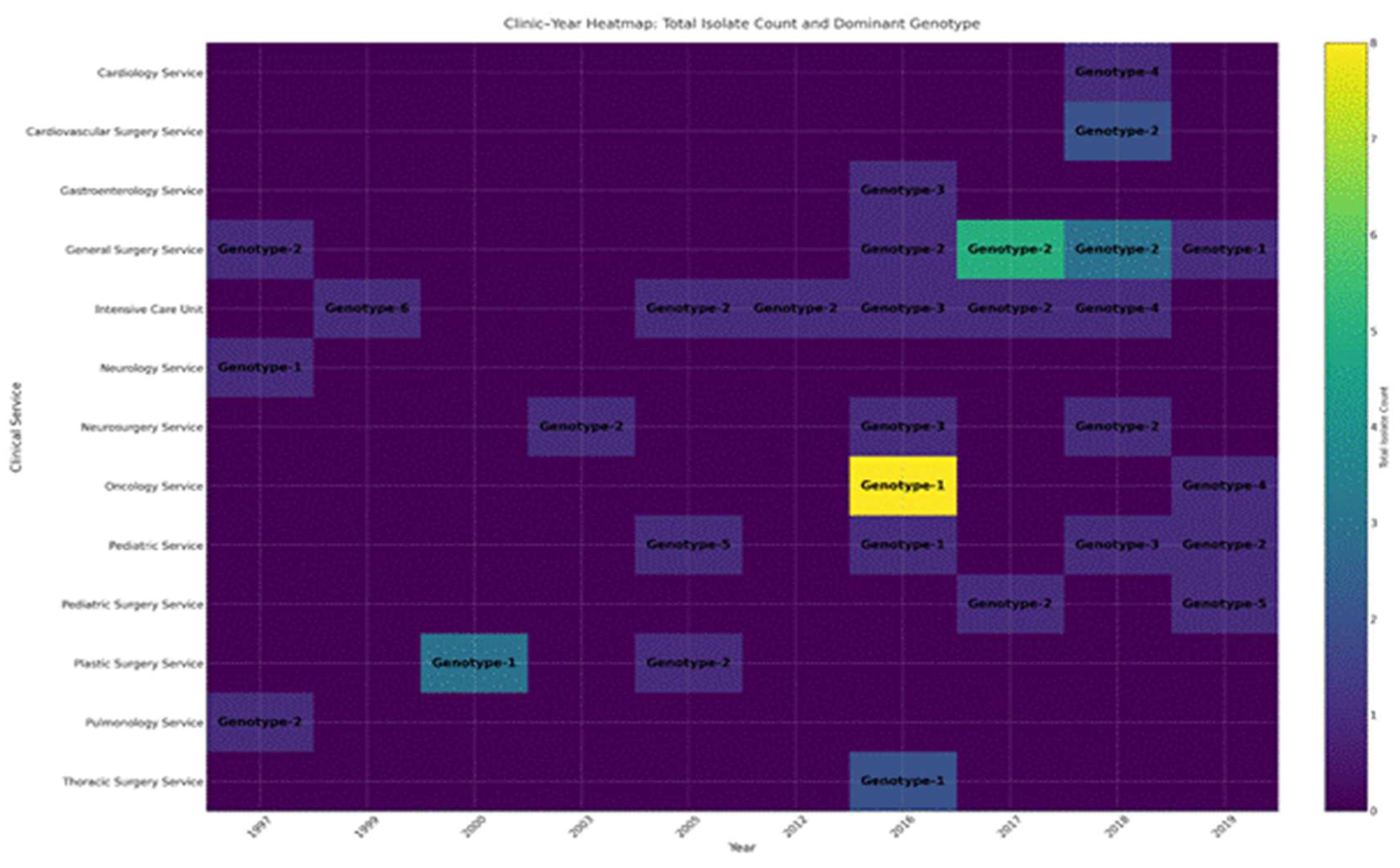

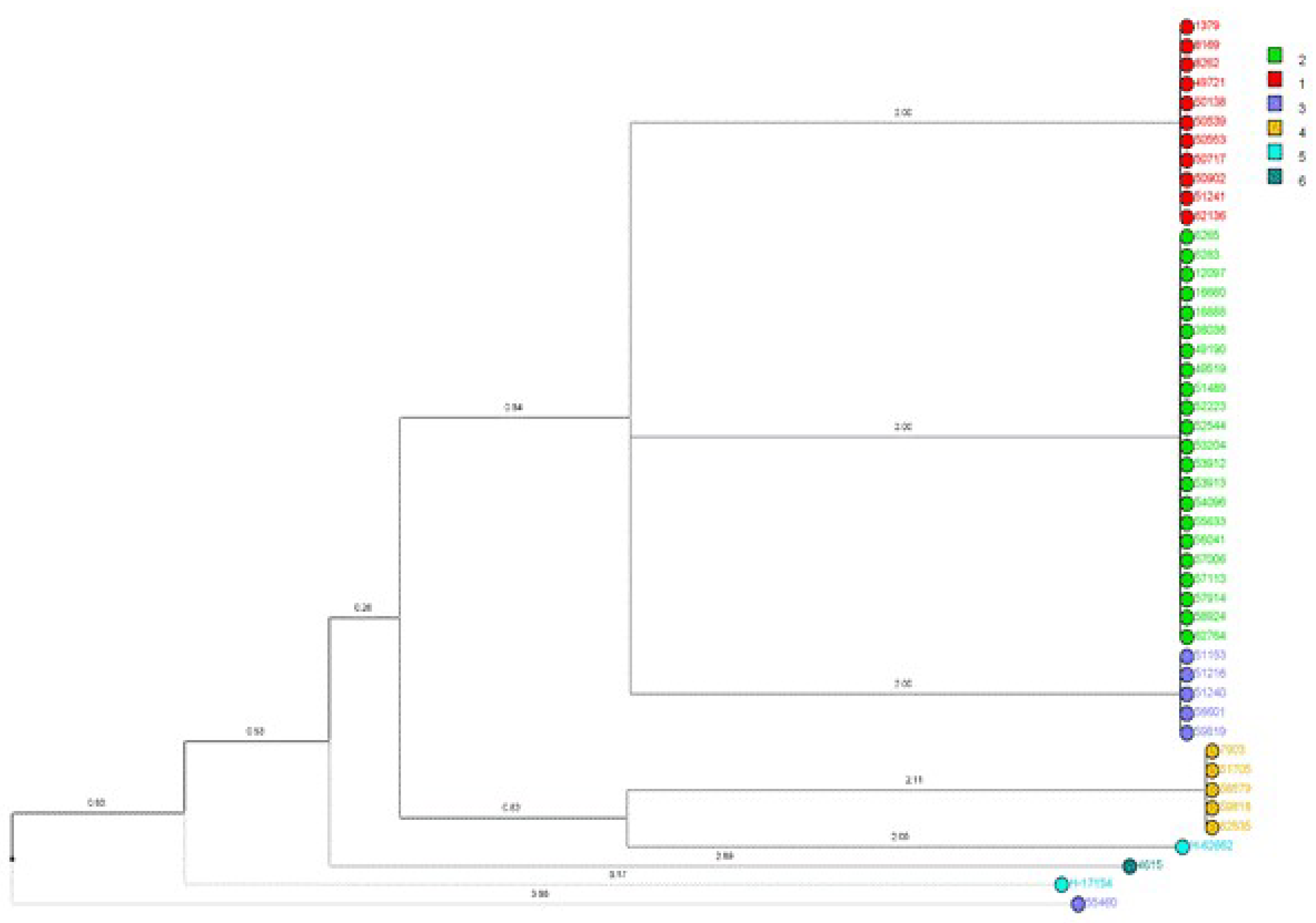

Fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis has emerged as a significant nosocomial pathogen, contributing to extensive outbreaks with severe clinical implications. Despite increasing evidence of clonal transmission, the genetic mechanisms that facilitate the persistence of hospital reservoirs remain inadequately characterized. We aimed to determine the extent of clonal spread and persistence patterns of fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis strains across a 22-year period in a tertiary care hospital, using high-resolution microsatellite genotyping. Forty-seven fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis isolates from candidemia patients (1997-2019) underwent microsatellite analysis using three polymorphic markers (CP1, CP4, B5). Genetic diversity, temporal distribution, and clonal relationships were assessed through phylogenetic analysis and discriminatory power calculations. Microsatellite analysis revealed minimal genetic diversity (combined discriminatory power: 0.7114), with only six distinct genotypes identified. Two dominant clones (Genotype-1: 23.4%, Genotype-2: 46.8%) persisted throughout the study, showing apparent spatiotemporal clustering in surgical and intensive care units. Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated tight genetic clustering, confirming prolonged clonal persistence spanning multiple years and clinical departments. Our findings provide compelling molecular evidence for persistent, multi-year clonal transmission of fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis within hospital environments. These results challenge current infection control paradigms and highlight the urgent need for enhanced surveillance strategies and targeted interventions to interrupt these persistent transmission chains.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. DNA Isolation and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

2.2. Antifungal Susceptibility Test

2.3. Microsatellite Instability Analysis

2.4. Phylogenetic Tree Construction

3. Results

4. Discussion

Funding

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sida H, Shah P, Pethani J, Patel L, Shah H. Study of biofilm formation as a virulence marker in Candida species isolated from various clinical specimens. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health 2015;5:842. [CrossRef]

- Mukul, P. Characterization of Candida Species isolated from samples taken from patients with known Immunocompromised state presenting with Oral Thrush. Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Research 2018;6. [CrossRef]

- Cortegiani A, Misseri G, Fasciana T, Giammanco A, Giarratano A, Chowdhary A. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, resistance, and treatment of infections by Candida auris. Journal of Intensive Care 2018;6. [CrossRef]

- Asogan, M. , Kim, H., Kidd, S., Alastruey-Izquierdo, A., Govender, N., Dao, A., Shin, J., Heim, J., Ford, N., Gigante, V., Sati, H., Morrissey, C., Alffenaar, J., & Beardsley, J. Candida parapsilosis: A systematic review to inform the World Health Organization fungal priority pathogens list. Medical Mycology, 2024;62. [CrossRef]

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García J, Machado M, Alcalá L, Reigadas E, Pérez-Ayala A, De La Pedrosa EG-G, et al. Trends in antifungal resistance in Candida from a multicenter study conducted in Madrid (CANDIMAD study): fluconazole-resistant C. parapsilosis spreading has gained traction in 2022. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2023;67. [CrossRef]

- Sharma V, Paul RA, Kaur H, Das S, Choudhary H, Rudramurthy SM, et al. P019 A 5-year study on prevalence and molecular determinants of fluconazole -resistance in C. parapsilosis spp. complex. Medical Mycology 2022;60. [CrossRef]

- Ünal N, Spruijtenburg B, Arastehfar A, Gümral R, De Groot T, Meijer EFJ, et al. Multicentre Study of Candida parapsilosis Blood Isolates in Türkiye Highlights an Increasing Rate of Fluconazole Resistance and Emergence of Echinocandin and Multidrug Resistance. Mycoses 2024;67. [CrossRef]

- Prigitano A, Blasi E, Calabrò M, Cavanna C, Cornetta M, Farina C, et al. Yeast bloodstream infections in the COVID-19 patient: a multicenter Italian study (FICOV study). Journal of Fungi 2023;9:277. [CrossRef]

- Levin AS, Costa SF, Mussi NS, Basso M, Sinto SI, Machado C, et al. Candida parapsilosis Fungemia Associated with Implantable and Semi-Implantable Central Venous Catheters and the Hands of Healthcare Workers. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 1998;30:243–9. [CrossRef]

- Qi L, Fan W, Xia X, Yao L, Liu L, Zhao H, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of Candida parapsilosis sensu stricto fungaemia in a neonatal intensive care unit in China. Journal of Hospital Infection 2018;100:e246–52. [CrossRef]

- Cacaci M, Squitieri D, Palmieri V, Torelli R, Perini G, Campolo M, et al. Curcumin-Functionalized Graphene Oxide Strongly Prevents Candida parapsilosis Adhesion and Biofilm Formation. Pharmaceuticals 2023;16:275. [CrossRef]

- Fekkar A, Blaize M, Bouglé A, Normand A-C, Raoelina A, Kornblum D, et al. Hospital Outbreak of Fluconazole-Resistant Candida parapsilosis: Arguments for Clonal Transmission and Long-Term Persistence. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2021;65. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez V, Vazquez JA, Barth-Jones D, Dembry L, Sobel JD, Zervos MJ. Nosocomial acquisition of Candida parapsilosis: An epidemiologic study. The American Journal of Medicine 1993;94:577–82. [CrossRef]

- Lupetti A, Tavanti A, Davini P, Ghelardi E, Corsini V, Merusi I, et al. Horizontal Transmission of Candida parapsilosis Candidemia in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2002;40:2363–9. [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh M, Ahmad S, Al-Sweih N, Hagen F, Meis JF, Khan Z. High-resolution fingerprinting of Candida parapsilosis isolates suggests persistence and transmission of infections among neonatal intensive care unit patients in Kuwait. Scientific Reports 2019a;9. [CrossRef]

- Thomaz DY, Del Negro GMB, Ribeiro LB, Da Silva M, Carvalho GOMH, Camargo CH, et al. A Brazilian Inter-Hospital Candidemia Outbreak Caused by Fluconazole-Resistant Candida parapsilosis in the COVID-19 Era. Journal of Fungi 2022;8:100. [CrossRef]

- Sabino R, Sampaio P, Rosado L, Videira Z, Grenouillet F, Pais C. Analysis of clinical and environmental Candida parapsilosis isolates by microsatellite genotyping—a tool for hospital infection surveillance. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2015;21:954.e1-954.e8. [CrossRef]

- Cilo BD, Agca H, Ener B. Identification of Candida parapsilosis Complex Strains Isolated from Blood Samples at Species Level and Determination of Their Antifungal Susceptibilities. Türk Mikrobiyoloji Cemiyeti Dergisi 2019. [CrossRef]

- Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility of yeasts. 4th ed. CLSI Standard M27. C: Wayne, PA, 2017.

- CLSI. Performance standards for antifungal susceptibility of yeasts. 3rd ed. CLSI supplement M27M44S. 2022.

- Neji S, Hadrich I, Ilahi A, Trabelsi H, Chelly H, Mahfoudh N, et al. Molecular Genotyping of Candida parapsilosis Species Complex. Mycopathologia 2018;183:765–75. [CrossRef]

- Arastehfar A, Daneshnia F, Hilmioğlu-Polat S, Fang W, Yaşar M, Polat F, et al. First Report of Candidemia Clonal Outbreak Caused by Emerging Fluconazole-Resistant Candida parapsilosis Isolates Harboring Y132F and/or Y132F+K143R in Turkey. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2020;64. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, PR. Reproducibility and indices of discriminatory power of microbial typing methods. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 1990;28:1903–5. [CrossRef]

- Sabino R, Sampaio P, Rosado L, Stevens DA, Clemons KV, Pais C. New Polymorphic Microsatellite Markers Able To Distinguish among Candida parapsilosis Sensu Stricto Isolates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2010;48:1677–82. [CrossRef]

- Desnos-Ollivier M, Bórmida V, Poirier P, Nourrisson C, Pan D, Bretagne S, et al. Population Structure of Candida parapsilosis: No Genetic Difference Between French and Uruguayan Isolates Using Microsatellite Length Polymorphism. Mycopathologia 2017;183:381–90. [CrossRef]

- Escribano P, Guinea J. Fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis: A new emerging threat in the fungi arena. Frontiers in Fungal Biology 2022;3. [CrossRef]

- McTaggart LR, Eshaghi A, Hota S, Poutanen SM, Johnstone J, De Luca DG, et al. First Canadian report of transmission of fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis within two hospital networks confirmed by genomic analysis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2023;62. [CrossRef]

- Tóth R, Nosek J, Mora-Montes HM, Gabaldon T, Bliss JM, Nosanchuk JD, et al. Candida parapsilosis: from Genes to the Bedside. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2019;32. [CrossRef]

- Reiss E, Lasker BA, Lott TJ, Bendel CM, Kaufman DA, Hazen KC, et al. Genotyping of Candida parapsilosis from three neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) using a panel of five multilocus microsatellite markers: Broad genetic diversity and a cluster of related strains in one NICU. Infection Genetics and Evolution 2012;12:1654–60. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Yu S-Y, Chen SC -a., Xiao M, Kong F, Wang H, et al. Molecular Characterization of Candida parapsilosis by Microsatellite Typing and Emergence of Clonal Antifungal Drug Resistant Strains in a Multicenter Surveillance in China. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020;11. [CrossRef]

- Romeo O, Delfino D, Cascio A, Lo Passo C, Amorini M, Romeo D, et al. Microsatellite-based genotyping of Candida parapsilosis sensu stricto isolates reveals dominance and persistence of a particular epidemiological clone among neonatal intensive care unit patients. Infection Genetics and Evolution 2012;13:105–8. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Castro R, Arroyo-Escalante S, Carrillo-Casas EM, Moncada-Barrón D, Álvarez-Verona E, Hernández-Delgado L, et al. Outbreak of Candida parapsilosis in a neonatal intensive care unit: a health care workers source. European Journal of Pediatrics 2009;169:783–7. [CrossRef]

- Miranda LDN, Rodrigues ECA, Costa SF, Van Der Heijden IM, Dantas KC, Lobo RD, et al. Candida parapsilosiscandidaemia in a neonatal unit over 7 years: a case series study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000992. [CrossRef]

- Dizbay M, Kalkanci A, Sezer BE, Aktas F, Aydogan S, Fidan I, et al. Molecular investigation of a fungemia outbreak due to Candida parapsilosis in an intensive care unit. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases 2008;12:395–9. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y-C, Lin Y-H, Chen K-W, Lii J, Teng H-J, Li S-Y. Molecular epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility of Candida parapsilosis sensu stricto, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis in Taiwan. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 2010;68:284–92. [CrossRef]

- Daneshnia F, De Almeida Júnior JN, Ilkit M, Lombardi L, Perry AM, Gao M, et al. Worldwide emergence of fluconazole-resistant Candida parapsilosis: current framework and future research roadmap. The Lancet Microbe 2023;4:e470–80. [CrossRef]

- Caggiano G, Fioriti S, Morroni G, Apollonio F, Triggiano F, D’Achille G, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of Candida parapsilosis bloodstream isolates: Health Care Associated Infections in a teaching Hospital in Italy. Journal of Infection and Public Health 2024;17:967–74. [CrossRef]

- Almirante B, RodríGuez D, Cuenca-Estrella M, Almela M, Sanchez F, Ayats J, et al. Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prognosis of Candida parapsilosis Bloodstream Infections: Case-Control Population-Based Surveillance Study of Patients in Barcelona, Spain, from 2002 to 2003. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2006;44:1681–5. [CrossRef]

- Miyake A, Gotoh K, Iwahashi J, Togo A, Horita R, Miura M, et al. Characteristics of Biofilms Formed by C. parapsilosis Causing an Outbreak in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Fungi 2022;8:700. [CrossRef]

- Arastehfar A, Hilmioğlu-Polat S, Daneshnia F, Pan W, Hafez A, Fang W, et al. Clonal Candidemia Outbreak by Candida parapsilosis Carrying Y132F in Turkey: Evolution of a Persisting Challenge. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Lortholary O, Renaudat C, Sitbon K, Desnos-Ollivier M, Bretagne S, Dromer F. The risk and clinical outcome of candidemia depending on underlying malignancy. Intensive Care Medicine 2017;43:652–62. [CrossRef]

- Pulcrano G, Roscetto E, Iula VD, Panellis D, Rossano F, Catania MR. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and microsatellite markers to evaluate Candida parapsilosis transmission in neonatal intensive care units. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 2012;31:2919–28. [CrossRef]

- Magobo RE, Naicker SD, Wadula J, Nchabeleng M, Coovadia Y, Hoosen A, et al. Detection of neonatal unit clusters of Candida parapsilosis fungaemia by microsatellite genotyping: Results from laboratory-based sentinel surveillance, South Africa, 2009-2010. Mycoses 2017;60:320–7. [CrossRef]

| Marker | Number of alleles | Allele sizes | Number of repeats | Allele frequencies | Number of genotypes | Genotype frequencies | Heterozygosity rate (%) | DP* |

| CP1 | 3 | 224-302 | 1-40 | 0.0213 - 0.9574 | 3 | 0.0110 - 0.8123 | 0 | 0.0842 |

| CP4 | 4 | 249-286 | 1-19 | 0.0213 - 0.8511 | 3 | 0.0222 - 0.6691 | 0.0425 | 0.2683 |

| B5 | 3 | 140-148 | 1-5 | 0.1277 - 0.6170 | 3 | 0.0676 - 0.3901 | 0 | 0.5495 |

| Total | 0.7114 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).