Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

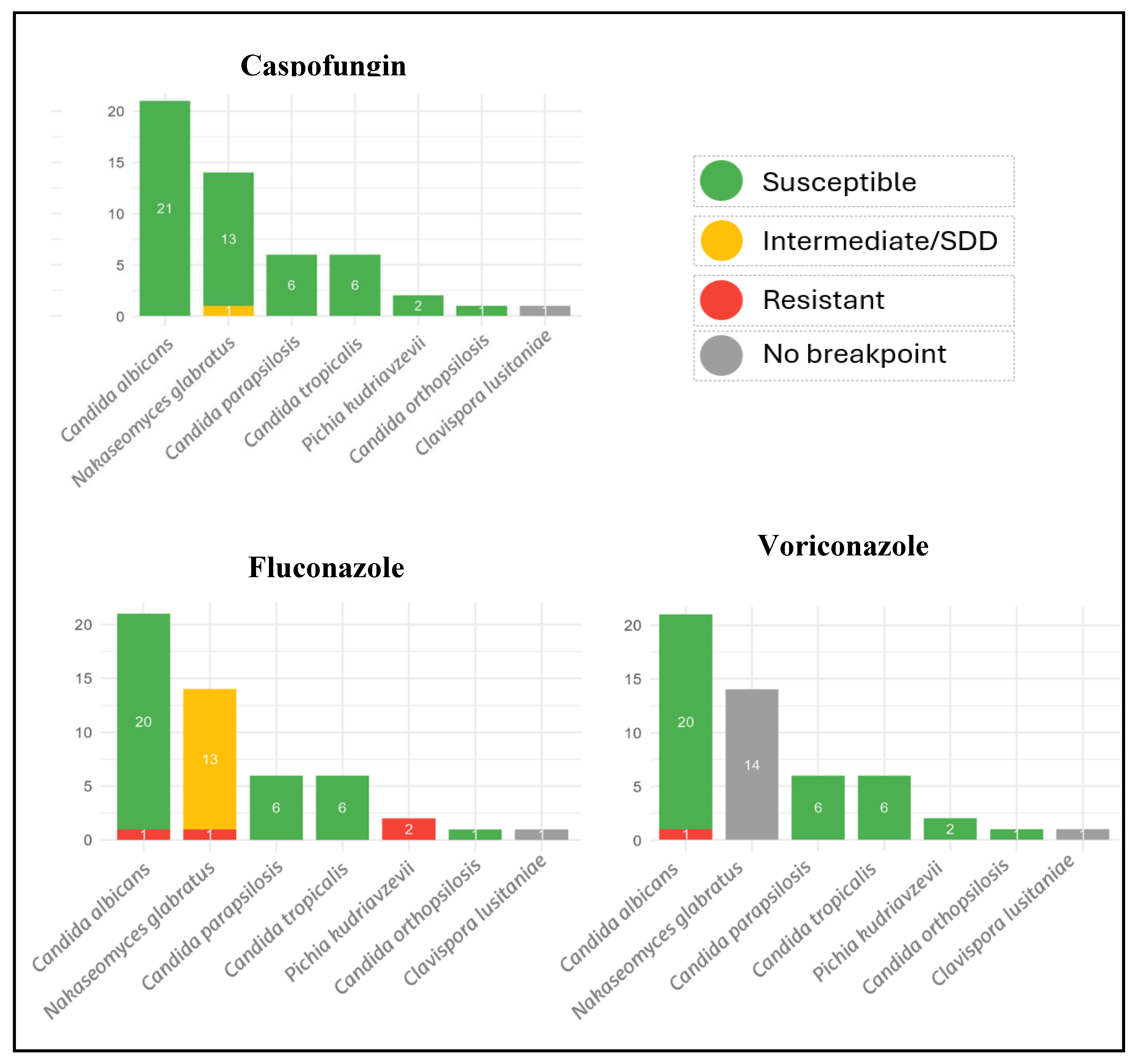

Background: Community-onset fungemia is a clinically significant syndrome frequently linked to recent healthcare exposure and significant morbidity and mortality. Methods: We performed a 21-year, single-center retrospective cohort of consecutive yeast bloodstream infections diagnosed at the Emergency Department (2004–2024). Clinical/epidemiological data, species identification (MALDI-TOF MS), antifungal susceptibility (CLSI M27; Sensititre YO10), and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) were analyzed. Results: Forty-eight episodes (51 isolates) were included; 56.3% were male, median age 74 years (IQR 63–82). Acquisition was healthcare-associated in 38/48 (79.2%). Sources were unknown (36.7%), abdominal (22.4%), urological (22.4%), catheter-related (14.3%) and 2.1% was attributed to a cardiovascular and a joint focus; 18.8% were polymicrobial. Crude mortality was 20.8% at 7 days (10/48) and 29.2% at 30 days (14/48). Species distribution: Candida albicans 41.2%, Nakaseomyces glabratus 27.5%, Candida parapsilosis 11.8%, Candida tropicalis 11.8%, Pichia kudriavzevii 3.9%, Clavispora lusitaniae 1.9%, and Candida orthopsilosis 1.9%. No isolate was resistant to anidulafungin, micafungin, or amphotericin B; one N. glabratus showed reduced susceptibility to caspofungin. Azole resistance occurred in one C. albicans and one N. glabratus isolate. WGS (44 isolates) confirmed MALDI-TOF identifications and characterized resistance markers. All 12 sequenced N. glabratus carried ERG2 I207V, PDR15/PDH1 E839D, and PDR1 V91I/L98S. Notable cases included one N. glabratus caspofungin-intermediate with FKS2 F659C, N. glabratus fluconazole-resistant with multiple PDR1 substitutions including a unique novel G857V, and C. albicans fluconazole-resistant harboring alterations in MRR1/MRR2, CDR1, and ERG11. Conclusions: In this 21-year cohort, community-onset fungemia was predominantly healthcare-associated, with C. albicans as the predominant species, followed by N. glabratus. Echinocandin resistance was not observed; azole resistance was uncommon. WGS provided precise speciation and actionable insight into resistance mechanisms, including a putatively novel PDR1 G857V in N. glabratus.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical and Epidemiological Data

- Diabetes mellitus: Yes/No (documented history of diabetes)

- Chronic kidney disease: Yes/No (established diagnosis of chronic renal disease)

- Recent surgery: Yes/No (surgical procedure within the previous three months; if yes, specify localization: abdominal, neurosurgical, or joint…)

- Haematological cancer: Yes/No (history of haematological malignancy)

- Neutropenia: yes/no (absolute neutrophil count below 500 cells/µL)

- Haematological transplantation: yes/no (prior haematopoietic stem-cell transplant)

- Solid tumour: Yes/No (diagnosis of solid-organ malignancy such as carcinomas, sarcomas, or other non-haematological cancers)

- Corticosteroid therapy: Yes/No (administration of corticosteroids within 30 days prior to diagnosis)

- Chemotherapy: Yes/No (receipt of chemotherapy within 30 days prior to diagnosis)

- Other immunosuppressive therapy: Yes/No (use of non-steroidal, non-chemotherapeutic immunosuppressive agents such as calcineurin inhibitors, antimetabolites, mTOR inhibitors, Janus kinase inhibitors, or monoclonal antibodies such as anti-TNF or anti-CD20 within 30 days prior to diagnosis)

- Recent antibiotic use: Yes/No (administration of antibiotics within 30 days prior to diagnosis)

- Recent antifungal use: Yes/No (administration of antifungal agents within 30 days prior to diagnosis)

- Central venous catheter: Yes/No (presence of a central venous catheter at the time of diagnosis)

- Urinary catheter: Yes/No (presence of an indwelling urinary catheter, such as a Foley or bladder catheter/vesical catheter, at the time of diagnosis)

- Haemodialysis catheter: Yes/No (presence of a vascular catheter specifically for haemodialysis)

- Healthcare-associated fungemia: Yes/No (diagnosis within 48 h of admission in patients with recent healthcare contact: hospitalization within 3 months, surgery, dialysis, or residence in a long-term care facility)

- Community-acquired fungemia: Yes/No (diagnosis within 48 h of admission in patients without recent healthcare exposure)

- Source of fungemia: (first assessed clinically; considered positive if the same microorganism is isolated at the suspected focus. Sources are classified as “unknown” when neither compatible clinical features nor microbiological confirmation at a focus are present. Possible sources include unknown, urological, abdominal, catheter-related, cardiovascular, joint, gynaecological, or cutaneous)

- Mixed Fungemia: Yes/No (presence of more than one microorganism isolated in the same blood culture; if yes, classified as either multiple yeasts or yeast plus bacteria)

- Empirical treatment: Yes/No (whether the patient received antimicrobial therapy before microbiological evidence of fungemia; if yes, specify if only antibiotic, only antifungal, or both in combination)

- Persistent fungemia: Yes/No (positive blood cultures for yeast despite appropriate antifungal therapy)

- Recent antifungal use: Yes/No Administration of antifungal agents within 30 days prior to diagnosis)

- Mortality at 7 days: Yes/No (death occurring within 7 days of the fungemia diagnosis)

- Mortality at 30 days: Yes/No (death occurring within 30 days of the fungemia diagnosis)

2.2. Identification and Antifungal Susceptibility

2.3. Molecular Analysis by Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS)

2.3.1. DNA Extraction

2.3.2. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

2.3.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiology and Clinical

3.2. Identification and Antifungal Susceptibility Test

3.3. WGS

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sofair, A.N.; Lyon, G.M.; Huie-White, S.; Reiss, E.; Harrison, L.H.; Thomson Sanza, L.; Arthington-Skaggs, B.A.; Fridkin, S.K. Epidemiology of Community-Onset Candidemia in Connecticut and Maryland; 2006.

- Pfaller, M.A.; Moet, G.J.; Messer, S.A.; Jones, R.N.; Castanheira, M. Candida Bloodstream Infections: Comparison of Species Distributions and Antifungal Resistance Patterns in Community-Onset and Nosocomial Isolates in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 2008-2009. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 561–566. [CrossRef]

- Chesdachai, S.; Baddour, L.M.; Sohail, M.R.; Palraj, B.R.; Madhavan, M.; Tabaja, H.; Fida, M.; Challener, D.W.; Desimone, D.C. Candidemia in Patients With Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Devices: Uncertainty in Management Based on Current International Guidelines. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023, 10, ofad318. [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Taramasso, L.; Nicco, E.; Molinari, M.P.; Mussap, M.; Viscoli, C. Epidemiology, Species Distribution, Antifungal Susceptibility and Outcome of Nosocomial Candidemia in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Italy. PLoS One 2011, 6, e24198. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xie, Z.; Jian, J. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Candidemia a 8-Year Retrospective Study from a Teaching Hospital in China. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Carpio, A.L.M.; Climaco, A. Candidemia. StatPearls 2024.

- Azie, N.; Neofytos, D.; Pfaller, M.; Meier-Kriesche, H.U.; Quan, S.P.; Horn, D. The PATH (Prospective Antifungal Therapy) Alliance® Registry and Invasive Fungal Infections: Update 2012. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012, 73, 293–300. [CrossRef]

- Neofytos, D.; Horn, D.; Anaissie, E.; Steinbach, W.; Olyaei, A.; Fishman, J.; Pfaller, M.; Chang, C.; Webster, K.; Marr, K. Epidemiology and Outcome of Invasive Fungal Infection in Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: Analysis of Multicenter Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH) Alliance Registry. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2009, 48, 265–273. [CrossRef]

- Montagna, M.T.; Caggiano, G.; Lovero, G.; De Giglio, O.; Coretti, C.; Cuna, T.; Iatta, R.; Giglio, M.; Dalfino, L.; Bruno, F.; et al. Epidemiology of Invasive Fungal Infections in the Intensive Care Unit: Results of a Multicenter Italian Survey (AURORA Project). Infection 2013, 41, 645–653. [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2015, 62, e1–e50. [CrossRef]

- Antinori, S.; Milazzo, L.; Sollima, S.; Galli, M.; Corbellino, M. Candidemia and Invasive Candidiasis in Adults: A Narrative Review. Eur J Intern Med 2016, 34, 21–28. [CrossRef]

- Guinea, J. Global Trends in the Distribution of Candida Species Causing Candidemia. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2014, 20, 5–10. [CrossRef]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J.; Rinaldi, M.G.; Barnes, R.; Hu, B.; Veselov, A.V.; Tiraboschi, N.; Nagy, E.; Gibbs, D.L.; Finquelievich, J.; et al. Results from the ARTEMIS DISK Global Antifungal Surveillance Study: A 6.5-Year Analysis of Susceptibilities of Candida and Other Yeast Species to Fluconazole and Voriconazole by Standardized Disk Diffusion Testing. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43, 5848–5859. [CrossRef]

- Wolfgruber, S.; Sedik, S.; Klingspor, L.; Tortorano, A.; Gow, N.A.R.; Lagrou, K.; Gangneux, J.P.; Maertens, J.; Meis, J.F.; Lass-Flörl, C.; et al. Insights from Three Pan-European Multicentre Studies on Invasive Candida Infections and Outlook to ECMM Candida IV. Mycopathologia 2024, 189, 70. [CrossRef]

- Lamoth, F.; Lockhart, S.R.; Berkow, E.L.; Calandra, T. Changes in the Epidemiological Landscape of Invasive Candidiasis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018, 73, i4. [CrossRef]

- Spettel, K.; Barousch, W.; Makristathis, A.; Zeller, I.; Nehr, M.; Selitsch, B.; Lackner, M.; Rath, P.M.; Steinmann, J.; Willinger, B. Analysis of Antifungal Resistance Genes in Candida Albicans and Candida Glabrata Using next Generation Sequencing. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0210397. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, B.D.. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2017; ISBN 1562388266.

- Chen, S. Fastp 1.0: An Ultra-fast All-round Tool for FASTQ Data Quality Control and Preprocessing. iMeta 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize Analysis Results for Multiple Tools and Samples in a Single Report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [CrossRef]

- Souvorov, A.; Agarwala, R.; Lipman, D.J. SKESA: Strategic k-Mer Extension for Scrupulous Assemblies. Genome Biol 2018, 19, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Lumpe, J.; Gumbleton, L.; Gorzalski, A.; Libuit, K.; Varghese, V.; Lloyd, T.; Tadros, F.; Arsimendi, T.; Wagner, E.; Stephens, C.; et al. GAMBIT (Genomic Approximation Method for Bacterial Identification and Tracking): A Methodology to Rapidly Leverage Whole Genome Sequencing of Bacterial Isolates for Clinical Identification. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0277575. [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and Applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10. [CrossRef]

- Bédard, C.; Pageau, A.; Fijarczyk, A.; Mendoza-Salido, D.; Alcañiz, A.J.; Després, P.C.; Durand, R.; Plante, S.; Alexander, E.M.M.; Rouleau, F.D.; et al. FungAMR: A Comprehensive Database for Investigating Fungal Mutations Associated with Antimicrobial Resistance. Nature Microbiology 2025, 10, 2338–2352. [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.J.; Choi, M.J.; Byun, S.A.; Won, E.J.; Park, J.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Choi, H.J.; Choi, H.W.; Kee, S.J.; Kim, S.H.; et al. Whole-Genome Sequence Analysis of Candida Glabrata Isolates from a Patient with Persistent Fungemia and Determination of the Molecular Mechanisms of Multidrug Resistance. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 515. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Cai, X.; Li, R.; Zheng, B.; Yang, E.; Liang, T.; Yang, X.; Wan, Z.; Liu, W. Two Sequential Clinical Isolates of Candida Glabrata with Multidrug-Resistance to Posaconazole and Echinocandins. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1217. [CrossRef]

- Chew, K.L.; Achik, R.; Osman, N.H.; Octavia, S.; Teo, J.W.P. Genomic Epidemiology of Human Candidaemia Isolates in a Tertiary Hospital. Microb Genom 2023, 9, 001047. [CrossRef]

- Nishimoto, A.T.; Zhang, Q.; Hazlett, B.; Morschhäuser, J.; David Rogers, P. Contribution of Clinically Derived Mutations in the Gene Encoding the Zinc Cluster Transcription Factor Mrr2 to Fluconazole Antifungal Resistance and CDR1 Expression in Candida Albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019, 63, e00078-19. [CrossRef]

- Štefánek, M.; Garaiová, M.; Valček, A.; Jordao, L.; Bujdáková, H. Comparative Analysis of Two Candida Parapsilosis Isolates Originating from the Same Patient Harbouring the Y132F and R398I Mutations in the ERG11 Gene. Cells 2023, 12, 1579. [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, R.A.; Fattouh, N.; Medvecky, M.; Hrabak, J. Whole Genome Sequencing of a Clinical Drug Resistant Candida Albicans Isolate Reveals Known and Novel Mutations in Genes Involved in Resistance Acquisition Mechanisms DATA SUMMARY. J Med Microbiol 2021, 70, 1351. [CrossRef]

- Flowers, S.A.; Colón, B.; Whaley, S.G.; Schuler, M.A.; David Rogers, P. Contribution of Clinically Derived Mutations in ERG11 to Azole Resistance in Candida Albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 450–460. [CrossRef]

- Dunkel, N.; -Blaß, J.; David Rogers, P.; Morschhäuser, J. Mutations in the Multidrug Resistance Regulator MRR1, Followed by Loss of Heterozygosity, Are the Main Cause of MDR1 Overexpression in Fluconazole-Resistant Candida Albicans Strains. [CrossRef]

- Coste, A.; Selmecki, A.; Forche, A.; Diogo, D.; Bougnoux, M.E.; D’Enfert, C.; Berman, J.; Sanglard, D. Genotypic Evolution of Azole Resistance Mechanisms in Sequential Candida Albicans Isolates. Eukaryot Cell 2007, 6, 1889–1904. [CrossRef]

- Jahanshiri, Z.; Manifar, S.; Arastehnazar, F.; Hatami, F.; Lotfali, E.; Jahanshiri, Z.; Manifar, S.; Arastehnazar, F.; Hatami, F.; Lotfali, E.; et al. Azole Resistance in Candida Albicans Isolates from Oropharyngeal Candidiasis Is Associated with ERG11 Mutation and Efflux Overexpression. Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology 2022 15:9 2022, 15, e132722. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Guerrero, J.P.; García-Salazar, E.; Hernandez Silva, G.; Chinney Herrera, A.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Pinto-Almazán, R.; Frías-De-León, M.G.; Castro-Fuentes, C.A. Candidemia: An Update on Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Susceptibility, and Treatment. Pathogens 2025, 14, 806. [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Rüddel, D.O.; Schlattmann, P.; Pletz, M.; Kurzai, O.; Bloos, F. Risk Factors for Invasive Candida Infection in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest 2021, 161, 345. [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, J.; Turner, N.A.; Yarrington, M.E.; Spires, S; Shaefer; Moehring, R.W.; Alexander, B.D.; Park, L.P.; Johnson, M.D. 1570. Cumulative Antibiotic Exposure and Risk for Candidemia. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Jung, P.; Mischo, C.E.; Gunaratnam, G.; Spengler, C.; Becker, S.L.; Hube, B.; Jacobs, K.; Bischoff, M. Candida Albicans Adhesion to Central Venous Catheters: Impact of Blood Plasma-Driven Germ Tube Formation and Pathogen-Derived Adhesins. Virulence 2020, 11, 1453. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, S.; Jiang, R.; Lei, S.; Wu, J.; Huang, L.; Zhu, M. Glucocorticoid Use and Parenteral Nutrition Are Risk Factors for Catheter-Related Candida Bloodstream Infection: A Retrospective Study. Asian Biomed (Res Rev News) 2024, 18, 109. [CrossRef]

- Lortholary, O.; Renaudat, C.; Sitbon, K.; Desnos-Ollivier, M.; Bretagne, S.; Dromer, F. The Risk and Clinical Outcome of Candidemia Depending on Underlying Malignancy. Intensive Care Med 2017, 43, 652–662. [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Venditti, M. Invasive Candidiasis in Surgery. 2025, 107–116. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Guerrero, J.P.; García-Salazar, E.; Hernandez, S.; Chinney Herrera, G.; Martínez-Herrera, A.; Pinto-Almazán, E.; Cabrera-Guerrero, J.P.; García-Salazar, E.; Silva, G.H.; Herrera, A.C.; et al. Candidemia: An Update on Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Susceptibility, and Treatment. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Shuping, L.; Mpembe, R.; Mhlanga, M.; Naicker, S.D.; Maphanga, T.G.; Tsotetsi, E.; Wadula, J.; Velaphi, S.; Nakwa, F.; Chibabhai, V.; et al. Epidemiology of Culture-Confirmed Candidemia among Hospitalized Children in South Africa, 2012-2017. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2021, 40, 730–737. [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.H.; Chakrabarti, A.; Li, R.Y.; Patel, A.K.; Watcharananan, S.P.; Liu, Z.; Chindamporn, A.; Tan, A.L.; Sun, P.-L.; Wu, U.-I.; et al. Incidence and Species Distribution of Candidaemia in Asia: A Laboratory-Based Surveillance Study. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Salmanton-García, J.; Cornely, O.A.; Stemler, J.; Barać, A.; Steinmann, J.; Siváková, A.; Akalin, H.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Loughlin, L.; Toscano, C.; et al. Attributable Mortality of Candidemia-Results from the ECMM Candida III Multinational European Observational Cohort Study. Medicine Medical Sciences and Nutrition, University of Journal of Infection 2024, 89, 106229. [CrossRef]

- Cornely, O.A.; Sprute, R.; Bassetti, M.; Chen, S.C.A.; Groll, A.H.; Kurzai, O.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Revathi, G.; et al. Global Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candidiasis: An Initiative of the ECMM in Cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect Dis 2025, 25, e280–e293. [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, J.; Machado, M.; Alcalá, L.; Reigadas, E.; Pérez-Ayala, A.; de la Pedrosa, E.G.G.; Gónzalez-Romo, F.; Cuétara, M.S.; García-Esteban, C.; Quiles-Melero, I.; et al. Trends in Antifungal Resistance in Candida from a Multicenter Study Conducted in Madrid (CANDIMAD Study): Fluconazole-Resistant C. Parapsilosis Spreading Has Gained Traction in 2022. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2023, 67. [CrossRef]

- Monarez, S.; Director, A.; Berkwits, M.; Gottardy, A.J.; Leahy, M.A.; Velarde, A.; Yang, T.; Doan, Q.M.; King, P.H.; Yang, M.; et al. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Population-Based Active Surveillance for Culture Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MMWR Editorial and Production Staff (Serials) MMWR Editorial Board. 2017, 29.

- Aldejohann, A.M.; Menner, C.; Thielemann, N.; Martin, R.; Walther, G.; Kurzai, O. In Vitro Activity of Ibrexafungerp against Clinically Relevant Echinocandin-Resistant Candida Strains. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Guo, P. Open Access BMC Microbiology. [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, S.K.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Healey, K.R.; Johnson, M.E.; Perlin, D.S.; Edlind, T.D. Fks1 and Fks2 Are Functionally Redundant but Differentially Regulated in Candida Glabrata: Implications for Echinocandin Resistance. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Whaley, S.G.; Berkow, E.L.; Rybak, J.M.; Nishimoto, A.T.; Barker, K.S.; Rogers, P.D. Azole Antifungal Resistance in Candida Albicans and Emerging Non-Albicans Candida Species. Front Microbiol 2017, 7. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Ischer, F.; Calabrese, D.; Posteraro, B.; Sanguinetti, M.; Fadda, G.; Rohde, B.; Bauser, C.; Bader, O.; Sanglard, D. Gain of Function Mutations in CgPDR1 of Candida Glabrata Not Only Mediate Antifungal Resistance but Also Enhance Virulence. PLoS Pathog 2009, 5. [CrossRef]

- Galocha, M.; Viana, R.; Pais, P.; Silva-Dias, A.; Cavalheiro, M.; Miranda, I.M.; Van Ende, M.; Souza, C.S.; Costa, C.; Branco, J.; et al. Genomic Evolution towards Azole Resistance in Candida Glabrata Clinical Isolates Unveils the Importance of CgHxt4/6/7 in Azole Accumulation. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Nishimoto, A.T.; Zhang, Q.; Hazlett, B.; Morschhäuser, J.; David Rogers, P. Contribution of Clinically Derived Mutations in the Gene Encoding the Zinc Cluster Transcription Factor Mrr2 to Fluconazole Antifungal Resistance and CDR1 Expression in Candida Albicans. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.; Addya, S. Structural Basis for Heterogeneous Phenotype of ERG11 Dependent Azole Resistance in C.Albicans Clinical Isolates. Springerplus 2014, 3, 1–16. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n = 48 | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Median age in years ((interquartile range) | 74 (63–82) | |

| Sex (male) | 27 | 56.3% |

| Predisposition factors | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 15 | 31.3% |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 | 16.7% |

| Recent surgery (≤3 months) | 11 | 22.9% |

| Abdominal surgery | 9 | 18.8% |

| Neurosurgery | 1 | 2.1% |

| Joint surgery | 1 | 2.1% |

| Haematologic cancer | 4 | 8.3% |

| Neutropenia | 3 | 6.3% |

| Hematologic cell transplantation | 2 | 4.2% |

| Solid tumour | 15 | 31.3% |

| Corticosteroid therapy | 8 | 16.7% |

| Chemotherapy | 10 | 20.8% |

| Other immunosuppressive therapy | 3 | 6.3% |

| Recent antibiotic use | 21 | 43.8% |

| Recent antifungal use | 2 | 4.2% |

| Catheter presence | 16 | 33.3% |

| Central venous catheter | 11 | 22.9% |

| Urinary catheter | 5 | 10.4% |

| Haemodialysis catheter | 1 | 2.1% |

| Origin | 0.0% | |

| Community-acquired | 10 | 20.8% |

| Healthcare-associated | 38 | 79.2% |

| Source of fungemia | ||

| Unknown | 18 | 37.5% |

| Urological | 11 | 22.9% |

| Abdominal | 10 | 20.8% |

| Catheter-related | 7 | 14.6% |

| Cardiovascular | 1 | 2.1% |

| Joint | 1 | 2.1% |

| Mixed Fungemia | ||

| No | 39 | 81.3% |

| Mixed fungemia with bacteria | 7 | 14.6% |

| Mixed fungemia with different Candida | 2 | 4.2% |

| Empirical treatment | ||

| Only antibiotic | 40 | 83.3% |

| Both antibiotic and antifungal | 1 | 2.1% |

| None | 7 | 14.6% |

| Persistent fungemia | 4 | 8.3% |

| Mortality | ||

| Crude mortality at 7 days | 10 | 20.8% |

| Crude mortality at 30 days | 14 | 29.2% |

| Function | Gene | Mutation | Isolates (n) | Resistant (n) | Previously Reported | Resistance Association | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efflux Pump | CDR1 | H58Y | 4 | F[R] | Yes | No | [24] |

| FLR1(Ben1) | V254I | 1 | 0 | Yes | No | [24] | |

| PDH1(Pdr15) | T1530K | 1 | 0 | Yes | No | [24] | |

| PDH1(Pdr15) | E839D | 12 | F[R], C[I] | Yes | No | [24] | |

| PDR1 | S76P | 7 | F[R], C[I] | Yes | No | [25] | |

| PDR1 | D243N | 5 | 0 | Yes | No | [25] | |

| PDR1 | V91I | 12 | F[R], C[I] | Yes | No | [24] | |

| PDR1 | T143P | 7 | F[R], C[I] | Yes | No | [24] | |

| PDR1 | L98S | 12 | F[R], C[I] | Yes | No | [24] | |

| Ergosterol Pathway | ERG2 | I207V | 12 | F[R], C[I] | Yes | No | [24] |

| ERG4 | T13N | 1 | 0 | Yes | No | [24] | |

| ERG6 | R48K | 1 | 0 | Yes | No | [24] | |

| ERG7 | T732A | 2 | C[I] | Yes | No | [24] | |

| ERG8 | N448S | 10 | F[R], C[I] | Yes | No | [24] | |

| Glucan Synthase | FKS2 | F659C | 1 | C[I] | Yes | Yes | [26] |

| FKS3 | R1472Q | 3 | F[R] | Yes | No | [24] | |

| Other | MSH2 | V239L | 3 | 0 | Yes | No | [24] |

| FEN1 | M155T | 2 | 0 | Yes | No | [24] |

| Function | Gene | Mutation | Isolates (n) | Resistant (n) | Previously Reported | Resistance Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucan Synthase | FKS3 | R1039L | 1 | C[I] | No | Uncertain |

| FKS3 | N1825S | 1 | C[I] | No | Uncertain | |

| FKS3 | A1621T | 1 | 0 | No | NM | |

| Efflux Pump | PDR1 | G857V | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain |

| Function | Gene | Mutation | Isolates (n) | Resistant (n) | Previously Reported | Resistance Association | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ergosterol Pathway | ERG11 CYP51 | E266D | 4 | 0 | Yes | No | [27] |

| ERG11 CYP51 | V488I | 1 | 0 | Yes | No | [27] | |

| ERG11 CYP51 | D116E | 1 | 0 | Yes | No | [27] | |

| Transcription Factor | MRR2 | S466L | 1 | 0 | Yes | No | [28] |

| MRR2 | T145A | 8 | F[R] | Yes | No | [29] | |

| MRR2 | A468G | 1 | 0 | Yes | No | [29] | |

| MRR2 | S480P | 10 | F[R] | Yes | No | [30] | |

| UPC2 | I142S | 9 | 0 | Yes | No | [30] | |

| MRR2 | S165N | 9 | F[R] | Yes | No | [27] | |

| MRR1 | A880E | 2 | 0 | Yes | No | [29] | |

| MRR1 | E1020Q | 4 | F[R] | Yes | No | [31] | |

| MRR2 | V451A | 4 | 0 | Yes | No | [30] | |

| TAC1 | M677del | 6 | 0 | Yes | No | [27] | |

| MRR1 | L248V | 1 | F[R] | Yes | No | [32] | |

| MRR2 | L144V | 8 | F[R] | Yes | No | [32] | |

| MRR1 | NPQS166 | 1 | F[R] | Yes | No | [33] |

| Function | Gene | Mutation | Isolates (n) | Resistant (n) | Previously Reported | Resistance Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efflux Pump | CDR1 | V616F | 3 | 0 | No | NM |

| CDR1 | T673A | 2 | 0 | No | NM | |

| CDR1 | A753K | 1 | 0 | No | NM | |

| CDR1 | S539R | 3 | 0 | No | NM | |

| CDR1 | T365del | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain | |

| CDR1 | Q790del | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain | |

| CDR1 | T947S | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain | |

| CDR1 | E949P | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain | |

| CDR1 | N1499 | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain | |

| CDR1 | K1500del | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain | |

| CDR1 | K1501del | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain | |

| Ergosterol Pathway | ERG11(CYP51) | Q142del | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain |

| Transcription Factor | CAP1 | Q188dup | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain |

| MRR1 | V340E | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain | |

| MRR1 | V27del | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain | |

| MRR1 | E336del | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain | |

| MRR2 | I204del | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain | |

| MRR2 | S580del | 1 | F[R] | No | Uncertain |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).