1. Introduction

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) remains a major global health challenge, with over 39 million people living with the virus and 1.3 million new infections annually [

1,

2,

3]. A defining characteristic of HIV progression is the depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes, leading to immunosuppression and an increased risk of opportunistic infections. Among these, fungal infections, particularly those caused by

Candida species, are some of the most frequent and clinically significant complications in people living with HIV (PLHIV) [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Candida species are commensal fungi that under normal conditions inhabit the gastrointestinal tract without causing harm. However, in immunosuppressed individuals, they can overgrow and cause localized or systemic infections, further compromising patient health. Chronic diarrhea is a common symptom in PLHIV, and the presence of

Candida in the gut has been associated with intestinal dysbiosis, malabsorption, systemic inflammation, and reduced antiretroviral therapy (ART) efficacy [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Despite its clinical relevance, gastrointestinal

Candida colonization remains an underexplored area in HIV research, particularly in Latin America.

While

Candida albicans is the most frequently isolated species in HIV/AIDS patients, recent studies have highlighted an increasing prevalence of non-

albicans Candida species, such as

C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and

C. parapsilosis, many of which exhibit antifungal resistance, particularly to fluconazole [

7,

13,

14]. The rise of drug-resistant

Candida species poses a major challenge in clinical management, as treatment options become limited. Furthermore,

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a yeast widely used in probiotics and food production, has also been identified as an opportunistic pathogen in immunocompromised patients, indicating a potential link between intestinal yeast colonization and systemic fungal infections [

15]. These findings underscore the need for robust epidemiological surveillance and improved diagnostic approaches to detect and characterize

Candida species in PLHIV, particularly in resource-limited settings where treatment options are constrained.

The epidemiology of

Candida infections varies across geographic regions, reflecting differences in environmental factors, healthcare access, and antifungal use. Studies have reported

Candida albicans prevalence rates of 82.2% in China, 74.5% in Brazil, and 36% in Spain, while non-

albicans Candida species predominate in regions such as Peru, where

C. tropicalis accounts for 67.4% of cases [

16,

17,

18]. In Ecuador,

C. albicans represents 52.2% of isolates, followed by

C. tropicalis (10.8%) and

C. glabrata (4.2%), revealing a distinct species distribution compared to other Latin American countries [

19,

20]. Despite these findings, there is limited research on the role of

Candida in HIV-related gastrointestinal infections in Ecuador. Given the high burden of HIV in certain urban and rural areas of the country, and the frequent lack of access to second-line antifungal treatments, understanding the prevalence and resistance patterns of

Candida species in this population is essential for improving patient outcomes.

Most studies on

Candida infections in PLHIV rely on conventional culture-based methods, which may fail to detect species diversity and antifungal resistance patterns. The integration of advanced molecular sequencing techniques, such as Illumina-NGS and ITS metagenomic analysis, provides a more comprehensive approach for identifying

Candida species and detecting emerging resistance mechanisms [

12,

21]. This study aims to determine the frequency and distribution of

Candida species in fecal samples from HIV/AIDS patients with chronic diarrhea, analyze the clinical, sociodemographic, and laboratory characteristics associated with

Candida presence, and evaluate antifungal susceptibility profiles using a combination of culture-based methods, molecular sequencing, and microscopy. This is a single-site study conducted at the José Daniel Rodríguez Infectious Hospital in Guayaquil, Ecuador, which allows for an in-depth analysis of the population within this clinical setting. While the findings will provide important epidemiological insights, they may not be generalizable to all regions of Ecuador or to broader Latin American populations.

By identifying species-specific trends, risk factors, and antifungal resistance patterns, this study will contribute valuable data to guide diagnostic strategies, clinical management, and public health policies for opportunistic fungal infections in PLHIV. Given Ecuador’s unique epidemiological landscape, the limited access to advanced diagnostics, and the growing concerns over antifungal resistance, this research represents a crucial step toward strengthening the country's response to HIV-related fungal infections.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study is a descriptive, cross-sectional analysis conducted at the José Daniel Rodríguez Infectious Hospital in Guayaquil, Ecuador, a specialized referral center for infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS management. Data collection took place between April 2021 and May 2022. The study examines demographic, clinical, laboratory, lifestyle, and antifungal resistance characteristics associated with Candida presence in fecal samples from people living with HIV (PLHIV) who presented with chronic diarrhea.

2.2. Study Population

The study population consisted of HIV-positive adults aged 18 years or older with a confirmed HIV diagnosis and symptoms of diarrhea at the time of recruitment. Patients who had received antibiotics or antifungals within the last 30 days, had other confirmed causes of diarrhea unrelated to Candida, or were unable to provide informed consent were excluded. A total of 92 patients were initially enrolled, with 85 meeting the final inclusion criteria.

2.3. Data Collection and Laboratory Analysis

Clinical, sociodemographic, and lifestyle data were collected through structured interviews and medical record reviews. Additionally, we used a data collection form specifically developed for this study to systematically record general clinical, sociodemographic, and lifestyle characteristics, as well as detailed laboratory results from each participant (see Supplementary File). Fecal samples were obtained in sterile containers and stored at 4°C before being transported to the National Institute for Public Health and Research (INSPI) for processing.

2.4. Microbiological analysis of Candida spores

Several laboratory techniques were employed to detect and characterize Candida species.

Gram staining was performed by heat-fixing fecal smears, staining them with gentian violet, applying Lugol’s iodine, decolorizing with alcohol, and counterstaining with safranin. Microscopic examination at 1000x magnification allowed for the identification of

Candida spores.

Figure 1

Immunofluorescence microscopy with Uvitex 2A and Rylux BA Calcofluor white a 488 nm filter and 1000x magnification was used to identify Candida spores.

Figure 2

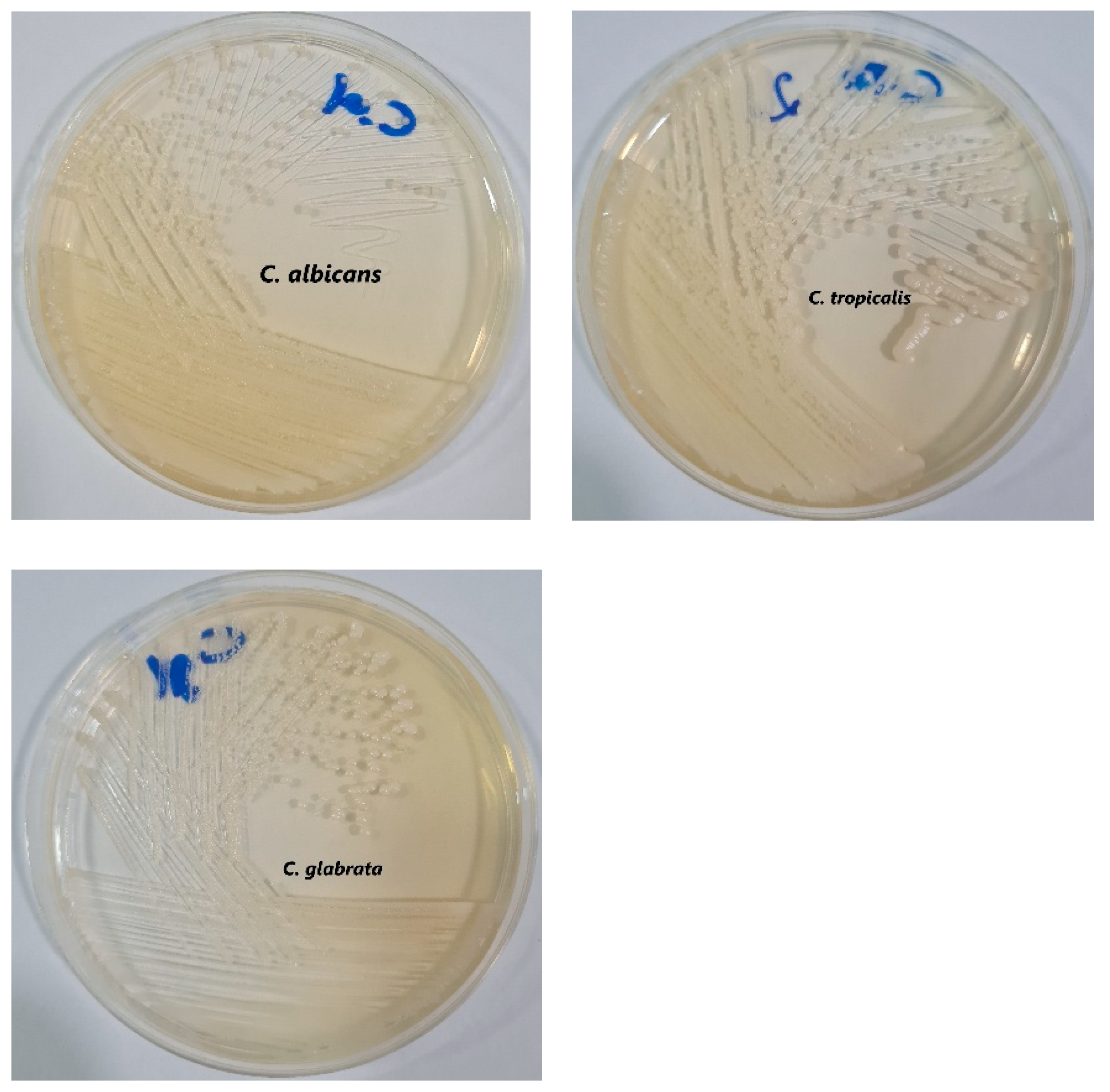

Another selective culture medium used is Sabouraud Dextrose Agar, for the isolation of mycelial fungi and yeasts from clinical samples. In this case, a stool sample was cultured. Its slightly acidic pH and the addition of chloramphenicol inhibit the growth of many bacterial species. Creamy white, soft, and smooth Candida colonies are observed in the culture medium.

Figure 3

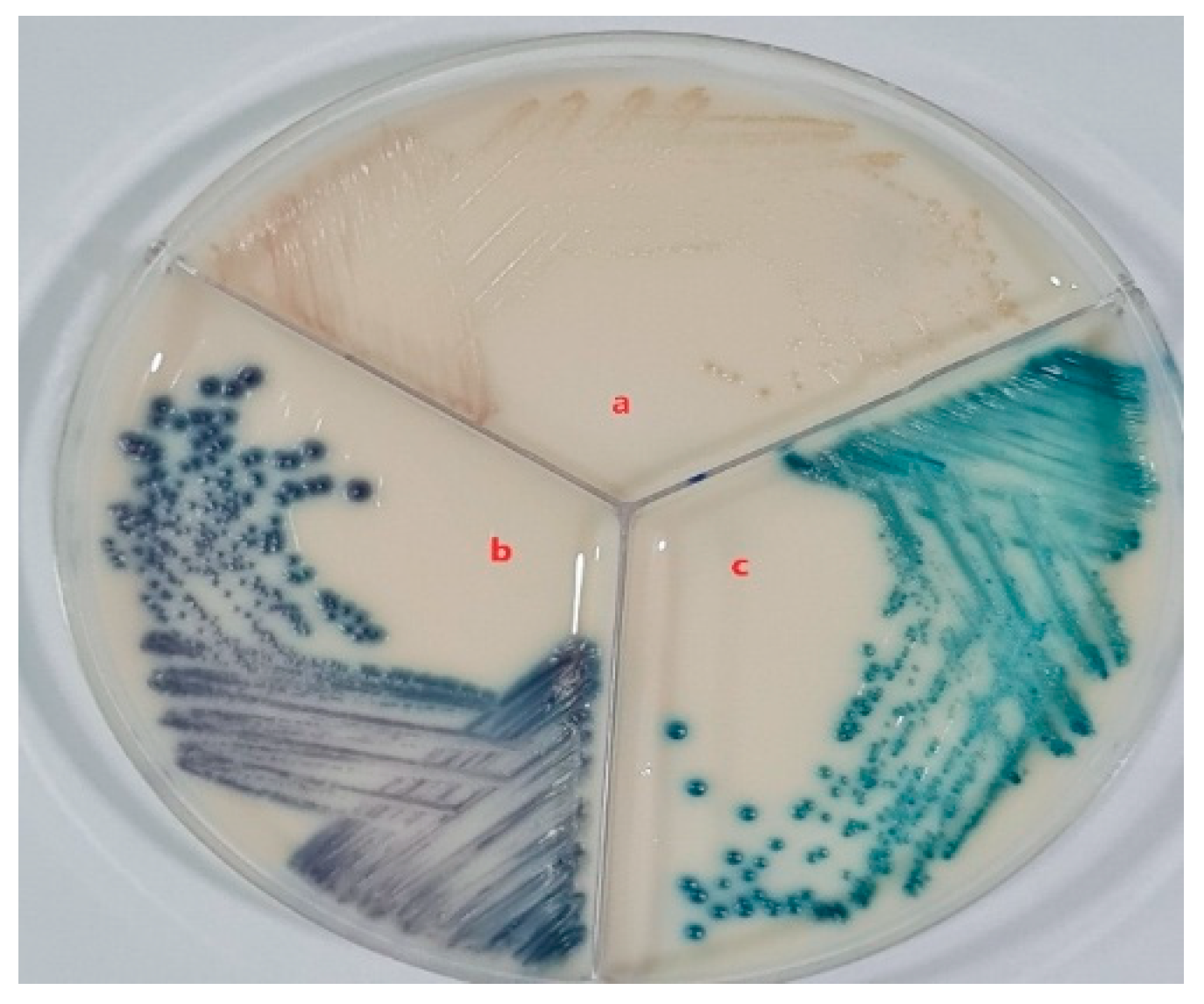

CHROMagar™ Candida Plus was used because it is a selective chromogenic culture medium for the direct qualitative detection, visual differentiation and presumptive identification of Candida species by color change with a high degree of specificity and sensitivity. The color they take indicates the species to which they correspond. Thus, if the colony turns bluish purple, it is Candida tropicalis, if it is apple green it is Candida albicans, and if it is pale pink, it is Candida glabrata.

Figure 4

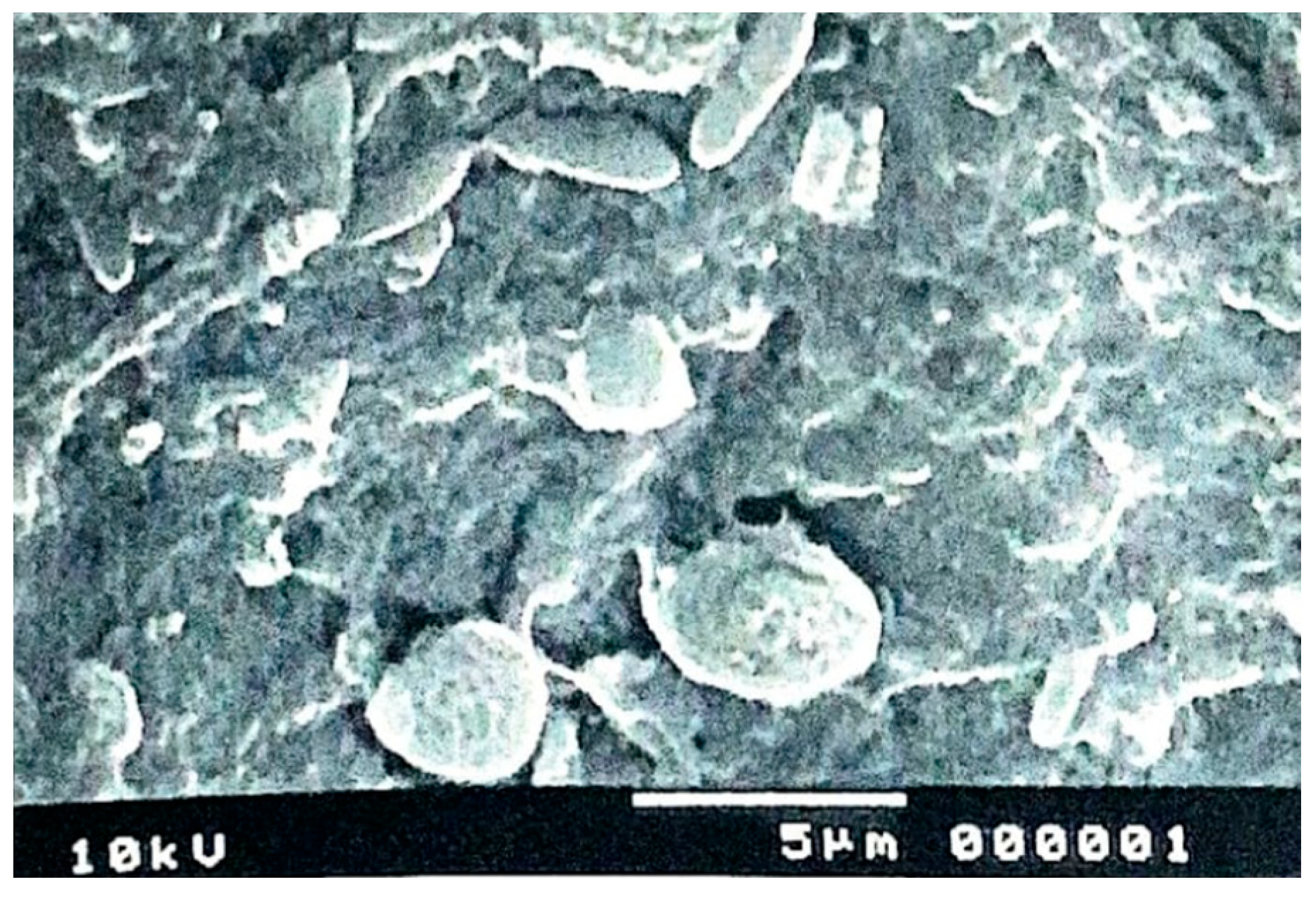

In addition, scanning electron microscopy was used, which allows the study of cell surfaces. The image is obtained by observing the sample with an ultra-fine electron beam. The generated signals are collected, amplified and captured in a cathode ray tube, and real three-dimensional images of the external structures of the Candida species can be observed.

Figure 5

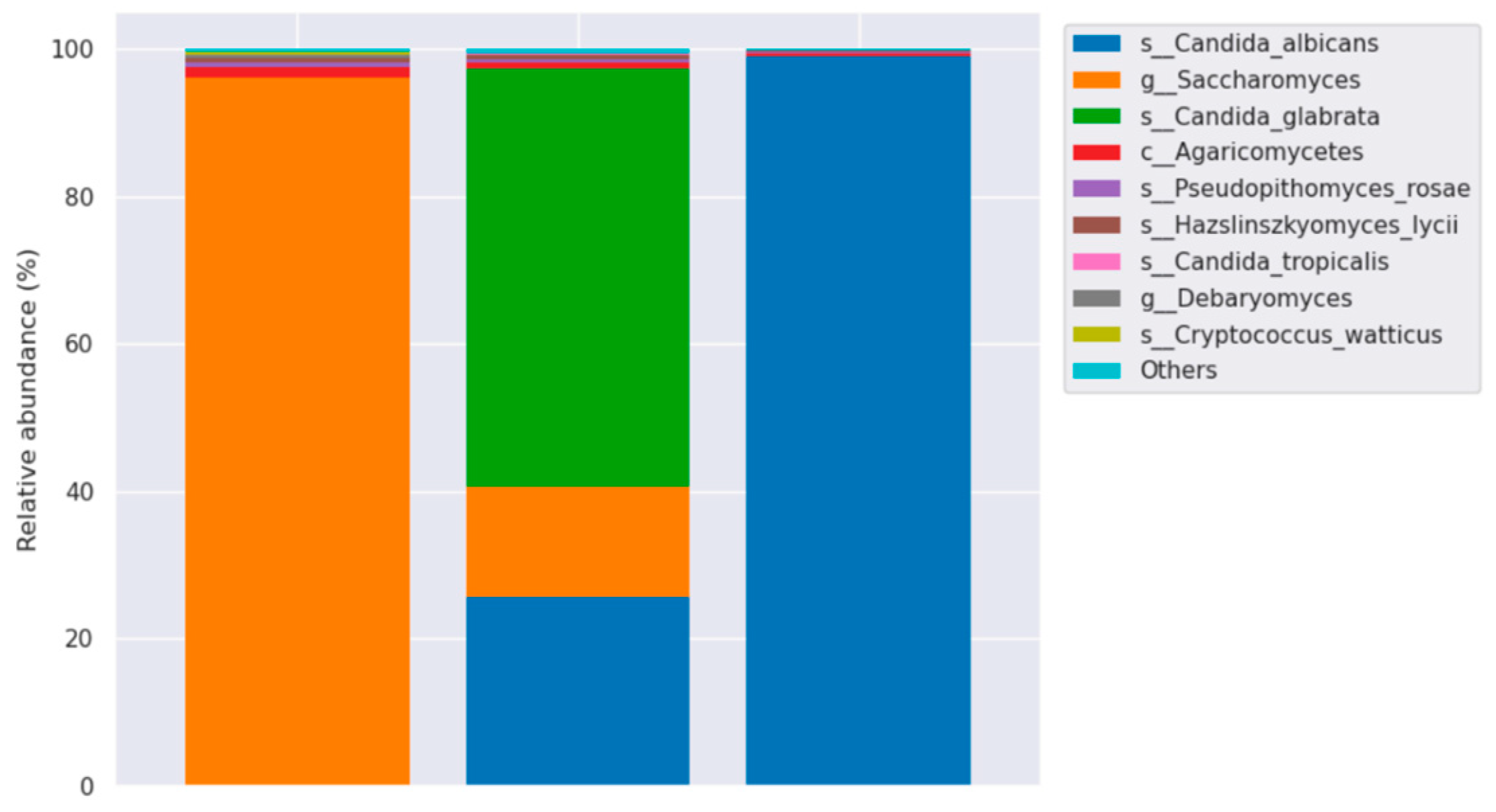

Molecular identification of Candida species was performed using Illumina-NGS sequencing with ITS metagenomic analysis. This technology is used to determine the order of nucleotides in entire genomes or in specific regions of DNA or RNA. NGS has revolutionized the biological sciences, allowing laboratories to perform a wide variety of applications and study biological systems at an unprecedented level. Based on the results of taxonomic annotation, the major taxa of each sample or group are displayed at each taxonomic rank (Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species) using a relative abundance distribution histogram.

Figure 6

2.5. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

To determine antifungal resistance patterns, susceptibility testing was performed using the VITEK® 2 Compact BioMérieux automated system, following the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined for fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, amphotericin B, and caspofungin.

Isolates were classified as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant based on EUCAST breakpoints. Resistance was further assessed based on species-specific thresholds, with particular attention to C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei, which have shown higher fluconazole resistance rates in previous studies. The prevalence of resistant strains was compared between different Candida species and among patients with varying levels of immunosuppression.

2.6. Variables

The primary outcome variable was Candida presence, categorized as "No Presence" or "Active Presence", based on laboratory results. Subgroup analyses were conducted for the detection of Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, and Candida glabrata.

Predictor variables included demographic characteristics (age, sex, city of residence, marital status, and education level), clinical characteristics (diarrhea type, adherence to ART, CD4 count, and viral load), and lifestyle factors (substance use).

Antifungal resistance variables included susceptibility status for fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, amphotericin B, and caspofungin, classified as susceptible, or resistant based on EUCAST breakpoints.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic, clinical, laboratory, and antifungal resistance data. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations.

Comparisons were made between patients with Candida presence ("No Presence" vs. "Active Presence") and between different Candida species. The proportion of resistant isolates was evaluated across different species, and the association between resistance patterns and CD4 count was explored descriptively.

This study did not perform inferential statistical testing, as its primary aim was to describe prevalence, species distribution, antifungal resistance, and clinical associations within the study population.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Hospital Luís Vernaza in Guayaquil, Ecuador (HLV-CEISH-2021-011). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion in the study. Strict confidentiality measures were implemented to ensure participant privacy.

3. Results

A total of 85 patients living with HIV and presenting with diarrhea were included in the study. The presence of

Candida species was detected in 64 patients (75.3%), while 21 patients (24.7%) showed no evidence of

Candida colonization. The demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the study population, stratified by

Candida presence, are summarized in

Table 1.

Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics

The study population was predominantly male (77.6%), with no significant difference between those with and without Candida presence (75.8% vs. 82.6%, respectively). The mean age was 40.8 years (SD: 10.6), with a slightly higher mean in those with Candida (41.2 years) compared to those without (39.6 years).

Most participants were from Guayaquil (61.2%), followed by smaller proportions from cities such as Durán (8.2%), Esmeraldas (5.9%), and Milagro (4.7%). The majority reported low economic status (100%), and 72.9% had never been married. Educational attainment was low, with 63.5% having only primary education, and only 3.5% having higher education.

Clinical Characteristics

Most participants had chronic diarrhea (96.5%), with no significant difference between groups. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence was poor, with 55.3% of patients having abandoned treatment and only 20% maintaining continuous adherence.

In terms of immune status, 68.6% of patients had severely low CD4 counts (<200 cells/µL), with a higher proportion in the Candida-positive group (71.0%) compared to the Candida-negative group (62.5%). A high viral load (≥10,000 copies/mL) was observed in 43.9% of patients, with a slightly higher prevalence in those with Candida (46.6%) compared to those without (37.5%).

Laboratory Findings

Microscopy and culture-based detection methods identified a range of Candida species. The presence of yeasts was detected in 70.6% of samples, with 41.2% showing low yeast presence (+), 23.5% moderate (++), and 5.9% high (+++).

Other fungal organisms, such as Saccharomyces spp., were found in 18.8% of patients, while Cryptococcus spp. was identified in only 1.2% of cases. Parasitic infections were rare, with Coli (5.9%) and Giardia spp. (3.5%) being the most frequently identified parasites.

Antifungal Susceptibility

Antifungal susceptibility testing revealed high levels of resistance to fluconazole, with 93.7% of active isolates classified as resistant (SEN1). Itraconazole (SEN2) showed lower resistance, with only 10.9% of isolates classified as resistant and 89.1% as sensitive. Voriconazole (SEN3) had a resistance rate of 87.5%. In contrast, all isolates were fully sensitive (100.0%) to amphotericin B (SEN4) and caspofungin (SEN5), with no resistant isolates detected for these antifungals.

Lifestyle Factors

Substance use was common, with 48.8% of participants reporting any substance use, though there was no significant difference between Candida-positive and Candida-negative groups.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the prevalence of

Candida species in HIV-positive patients presenting with diarrhea, revealing that

Candida colonization was present in 75.3% of the participants. This finding underscores the high burden of fungal infections in immunocompromised individuals, particularly in resource-limited settings such as Ecuador. The study also identified significant associations between

Candida presence and key clinical parameters, including low CD4 counts, high viral loads, and poor adherence to ART. These results align with previous studies, which have demonstrated that

Candida species frequently colonize the gastrointestinal tract of HIV/AIDS patients and contribute to persistent diarrhea and other gastrointestinal complications [

8,

11].

The high prevalence of Candida in this cohort aligns with prior studies that have documented increased fungal colonization in HIV-infected populations, particularly in individuals with advanced immunosuppression (Maheshwari et al., 2016; Zuza-Alves et al., 2017). Previous research has consistently shown that CD4 counts below 200 cells/µL are a critical risk factor for opportunistic infections, including fungal pathogens. The present study supports this observation, with a significantly higher proportion of patients with Candida falling into the severely low CD4 category (<200 cells/µL, 71.0%).

Moreover, the observed fluconazole resistance in

Candida species is concerning and mirrors trends reported in other studies (Wang et al., 2021; Usher, 2024). 94.5% resistance in SEN1 and 87.3% resistance in SEN3 suggest that fluconazole monotherapy may no longer be a viable option for treating fungal infections in this population. These findings are consistent with previous reports indicating an increasing prevalence of fluconazole-resistant

Candida glabrata and

Candida tropicalis, particularly in Latin America [

16,

18]. The universal sensitivity to caspofungin (SEN4, SEN5, SEN6) suggests that echinocandins remain an effective therapeutic option, supporting existing guidelines for the management of invasive candidiasis [

12].

The association between high viral loads and

Candida colonization (46.6% vs. 37.5%) is also consistent with literature emphasizing that poor HIV viral suppression increases susceptibility to fungal infections (Awoyeni et al., 2017). The link between high viral loads and

Candida colonization suggests that immune restoration through ART adherence is critical in reducing fungal burden. However, 55.3% of participants had abandoned ART, highlighting a significant public health concern. Studies have previously shown that ART nonadherence leads to increased risk of opportunistic infections and higher mortality rates in HIV/AIDS patients [

5,

10].

Study Limitations

Despite its contributions, this study has certain limitations. First, it is a single-site study, conducted at the José Daniel Rodríguez Infectious Hospital in Guayaquil, Ecuador. As such, the findings may not be fully generalizable to the broader HIV-positive population in Ecuador or other Latin American regions. A larger, multicentric study would provide a more comprehensive epidemiological profile. Additionally, the sample size of 85 participants, while informative, limits the statistical power to detect smaller associations.

This study is purely descriptive due to the small sample size, which limits the ability to perform inferential statistical analyses. With only 85 participants, the study does not have sufficient statistical power to establish causal relationships or to conduct multivariate analyses that adjust for potential confounders. As a result, while strong associations between Candida colonization and key clinical parameters were observed, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Future studies with larger sample sizes and advanced statistical modeling are necessary to confirm these associations and explore potential confounding factors.

Another limitation is that fungal species identification was based on culture and microscopy, which, while robust, may have missed certain non-culturable or emerging fungal pathogens that could have been detected using molecular techniques such as ITS metagenomics sequencing [

17]. Given the emergence of cryptic and resistant fungal species, future studies should incorporate next-generation sequencing to improve diagnostic accuracy.

Lastly, while antifungal susceptibility testing was conducted, the mechanisms of resistance were not investigated. Molecular analysis of resistance genes, such as ERG11 mutations associated with fluconazole resistance in

Candida albicans, would provide valuable insights into the evolving epidemiology of antifungal resistance in Ecuador [

11,

13].

Implications and Future Directions

These findings have several important clinical and public health implications. The high prevalence of

Candida and its association with poor ART adherence and advanced immunosuppression highlight the need for enhanced patient education and adherence support programs to reduce the burden of opportunistic infections. Health authorities should implement targeted interventions, such as routine fungal screening in HIV/AIDS patients with diarrhea, to facilitate early detection and treatment [

15]. Additionally, the high fluconazole resistance suggests an urgent need to revise treatment guidelines and incorporate routine antifungal susceptibility testing in clinical practice. In Ecuador and other resource-limited settings, access to alternative antifungals such as echinocandins is limited, necessitating improved antifungal stewardship programs to ensure appropriate prescribing practices [

12]. Given the very small sample size, this study is descriptive in nature and should be interpreted with caution. Future research should focus on expanding this study to multiple clinical sites to increase generalizability. Additionally, molecular analyses of antifungal resistance genes could provide deeper insights into resistance mechanisms, informing more targeted therapeutic strategies [

16]. Given the emerging role of non-

Candida species in immunocompromised populations, future studies should also consider next-generation sequencing approaches to identify a broader spectrum of fungal pathogens.

5. Conclusion

This study provides critical insights into the epidemiology of Candida colonization in HIV-positive patients with diarrhea, demonstrating a high prevalence, strong associations with immune suppression, and concerning antifungal resistance patterns. While the findings reinforce known risk factors, they also highlight urgent gaps in clinical management, particularly regarding fluconazole resistance and ART adherence. Addressing these gaps through better diagnostic practices, antifungal stewardship, and patient-centered interventions is essential to improving outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Hospital Luís Vernaza in Guayaquil, Ecuador (HLV-CEISH-2021-011). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion in the study.

Clinical Trial

Not applicable. This is not a clinical trial.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Availability of data and material

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study, which includes de-identified clinical and microbiological information from individuals living with HIV, has been deposited in both the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and the Open Science Framework (OSF). To ensure participant confidentiality, all data have been fully anonymized. The dataset is accessible through the NCBI SRA under BioProject accession number PRJNA1251125

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1251125) and is mirrored on OSF at

https://osf.io/dq2a4/.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions: Conceptualization

B.P.-G., J.R.-P. and K.R.-P.; Methodology: B.P.-G., M.F.-H. and L.C.-M.; Validation: B.P.-G., E.R.-N. and M.F.-H.; Formal analysis: B.P.-G., K.R.-P., R.C.-P. R.P.-P.,and J.R.-P.; Investigation: B.P.-G., M.F.-H., J.R.-P., K.R.-P., E.R.-N., L.C.-M., R.C.-P. and M.M.-A.; Resources: B.P.-G., E.R.-N. and B.Z.-R.; Data curation: B.P.-G., M.F.-H., E.R.-N., and G.G.-Q.; Writing—original draft preparation: B.P.-G. and J.R.-P.; Writing—review and editing: B.P.-G., M.F.-H., E.R.-N., G.G.-Q. and B.Z.-R.; Visualization: B.P.-G., L.C.-M., K.R.-P., G.G.-Q. R.P.-P., and M.F.-H.; Supervision: B.P.-G. and M.F.-H.; Project administration: B.P.-G.; Funding acquisition: B.P.-G. and E.R.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants in this study for their valuable contribution. Special thanks to the staff of the José Daniel Rodríguez Infectious Hospital for their collaboration in the data collection process. Additionally, we acknowledge the contribution of the Laboratorio Clínico y Microbiológico Pazmiño for their support with laboratory analysis.

References

- Barton-Knott, S. and Karp-Sawey, J. ONUSIDA pide a los líderes que se comprometan en Davos a acelerar el acceso mundial a nuevos y revolucionarios medicamentos de acción prolongada contra el VIH. 2024.

- Cabrera Dutan, K., Wilson Cabrera Dutan, Pinchao Obando, D., and Ordóñez Ortiz, A. Infección por virus de inmunodeficiencia humana | RECIAMUC. 2021.

- Cajape, A., Cano, A., and Saltos, K. Virus de la Inmunodeficiencia Humana (VIH) efectos y complicaciones adquiridas durante la infección. | Revista Científica Higía de la Salud. 2022.

- Ambe, N.F., Longdoh, N.A., Tebid, P., Bobga, T.P., Nkfusai, C.N., Ngwa, S.B., et al. The prevalence, risk factors and antifungal sensitivity pattern of oral candidiasis in HIV/AIDS patients in Kumba District Hospital, South West Region, Cameroon. The Pan African Medical Journal. 36. 23. 2020.

- Blamey, R., Sciaraffia, A., Piñera, C., Silva, M., Araya, X., Ceballos, M.E., et al. Situación epidemiológica de VIH a nivel global y nacional: Puesta al día. Revista chilena de infectología. 41 (2). 248–58. 2024.

- Ding, Z.-D., Zheng, J.-F., Song, C.-B., Fu, Y.-J., Xu, J.-J., Jiang, Y.-J., et al. Decreased CD4+CD8low T cells in early HIV infection are associated with rapid disease progression. Cytokine. 125. 154801. 2020.

- Maheshwari, M., Kaur, R., and Chadha, S. Candida Species Prevalence Profile in HIV Seropositive Patients from a Major Tertiary Care Hospital in New Delhi, India. Journal of Pathogens. 2016 (1). 6204804. 2016.

- Nkenfou, C.N., Tchameni, S.M., Nkenfou, C.N., Djataou, P., Simo, U.F., Nkoum, A.B., et al. Intestinal Parasitic Infections in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected and Noninfected Persons in a High Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevalence Region of Cameroon. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 97 (3). 777. 2017.

- Awoyeni, A., Olaniran, O., Odetoyin, B., Hassan-Olajokun, R., Olopade, B., Afolayan, D., et al. Isolation and evaluation of Candida species and their association with CD4+ T cells counts in HIV patients with diarrhoea. African Health Sciences. 17 (2). 322–9. 2017.

- Filler, E.E., Liu, Y., Solis, N.V., Wang, L., Diaz, L.F., John E Edwards, J., et al. Identification of Candida glabrata Transcriptional Regulators That Govern Stress Resistance and Virulence. Infection and Immunity. 89 (3). e00146. 2021.

- Gabaldón, T. and Fairhead, C. Genomes shed light on the secret life of Candida glabrata: not so asexual, not so commensal. Current Genetics. 65 (1). 93. 2018.

- Heestermans, R., Herroelen, P., Emmerechts, K., Vandoorslaer, K., Geyter, D.D., Demuyser, T., et al. Validation of the Colibrí Instrument for Automated Preparation of MALDI-TOF MS Targets for Yeast Identification. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 60 (7). e00237. 2022.

- Wang, D., An, N., Yang, Y., Yang, X., Fan, Y., and Feng, J. Candida tropicalis distribution and drug resistance is correlated with ERG11 and UPC2 expression. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 10. 54. 2021.

- Zuza-Alves, D.L., Silva-Rocha, W.P., and Chaves, G.M. An Update on Candida tropicalis Based on Basic and Clinical Approaches. Frontiers in Microbiology. 8. 1927. 2017.

- Nash, A.K., Auchtung, T.A., Wong, M.C., Smith, D.P., Gesell, J.R., Ross, M.C., et al. The gut mycobiome of the Human Microbiome Project healthy cohort. Microbiome. 5 (1). 153. 2017.

- Freitas, V.A.Q., Santos, A.S., Zara, A.L.S.A., Costa, C.R., Godoy, C.S. de M., Soares, R. de B.A., et al. Distribution and antifungal susceptibility profiles of Candida species isolated from people living with HIV/AIDS in a public hospital in Goiânia, GO, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 54 (1). 125. 2022.

- Li, Y.-Y., Chen, W.-Y., Li, X., Li, H.-B., Li, H.-Q., Wang, L., et al. Asymptomatic oral yeast carriage and antifungal susceptibility profile of HIV-infected patients in Kunming, Yunnan Province of China. BMC Infectious Diseases. 13. 46. 2013.

- Salinas, C. CARACTERÍSTICAS CLÍNICAS, MICROBIOLÓGICAS Y DESENLACES DE LA CANDIDIASIS INVASORA EN ADULTOS EN UN HOSPITAL DE ALTA COMPLEJIDAD. 2022.

- Soto, M. REVISIÓN DE LAS CANDIDEMIAS EN LATINOAMERICA. 2019.

- Vásquez-Zamora, K.G., Villalobos-Barboza, K., Vergara Espinoza, M.A., Ventura-Flores, R., Silva-Díaz, H., Vásquez-Zamora, K.G., et al. Frecuencia y susceptibilidad antifúngica de Candida spp. (no C. albicans ) aislada de pacientes de unidades de cuidados críticos de un hospital de tercer nivel del norte del Perú. Horizonte Médico (Lima). 20 (4). 2020.

- Usher, J. Genetic Manipulation of Candida glabrata. Current Protocols. 4 (9). e70014. 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).