Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Integration of the GC-MS-Based Workflow with Other Metabolomics Platforms

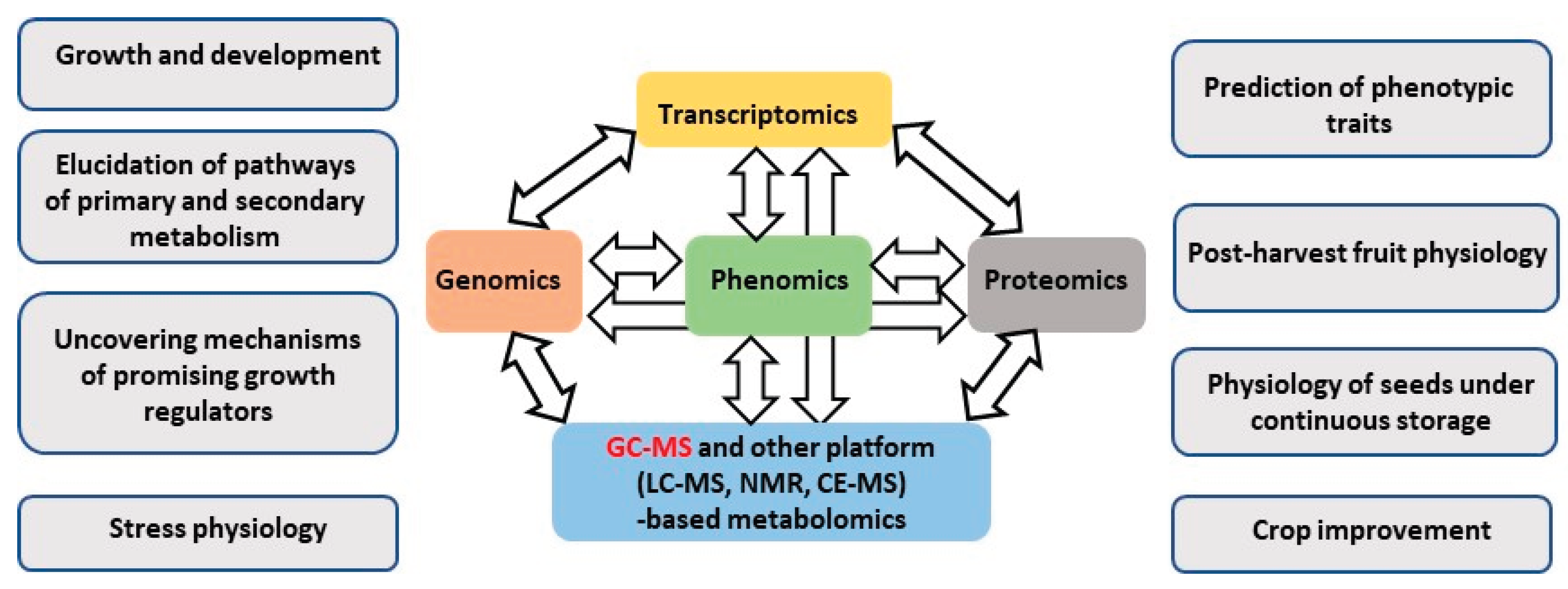

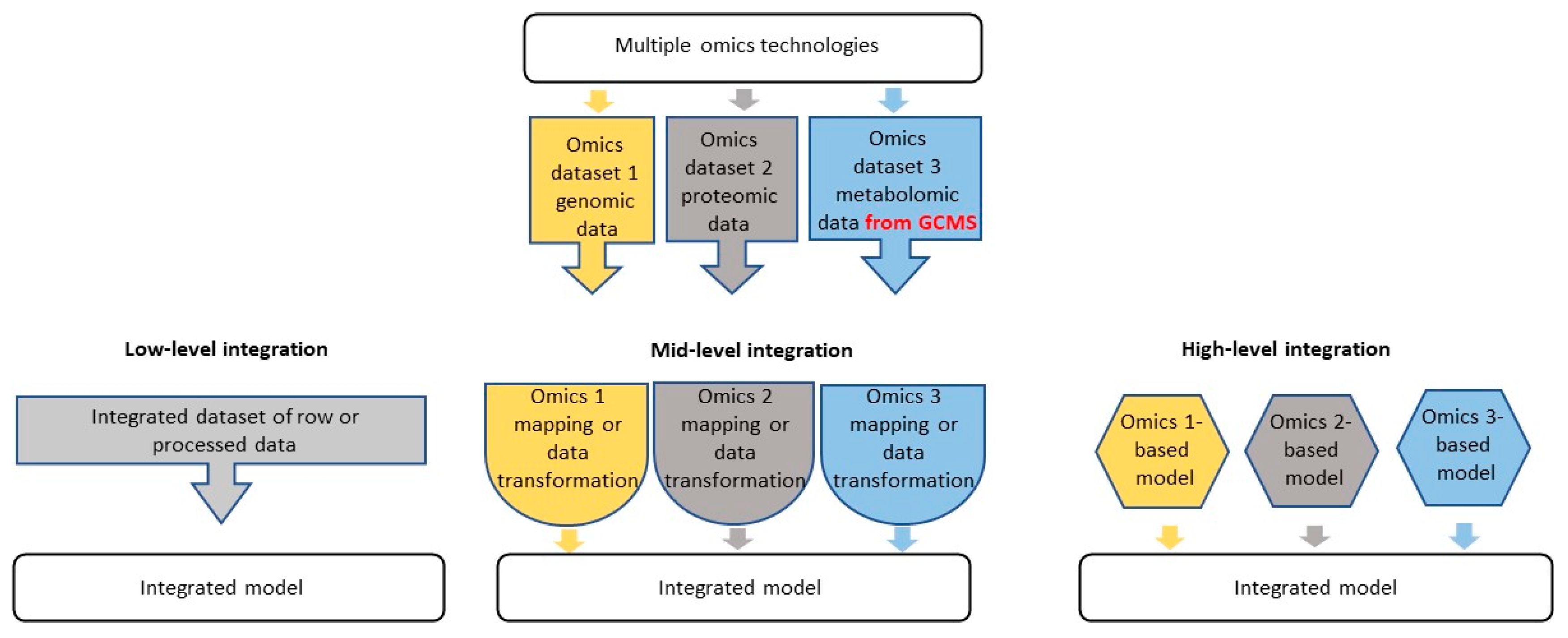

3. Implementation of GC-MS in Multi-Omics Strategies of Post-Genomic Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2PG | 2-phosphoglycerate |

| 3PG | 3-phosphoglycerate |

| CE | Capillary electrophoresis |

| CE-MS | Capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry |

| CE-TOF-MS | Capillary electrophoresis-time-of-flight-mass spectrometer |

| CoA | Coenzyme A |

| DGPP | Diacylglycerol diphosphate |

| DI-SPME-GC-MS | Direct immersion-solid-phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| EC numbers | Enzyme commission number |

| ECP | Extracellular polysaccharide |

| EI | Electron impact |

| ESI | Electrospray |

| GAP | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate |

| GC-EI-Q-MS | GC-quadrupole mass spectrometry with EI ionization |

| GC-FID | Gas chromatography-flame ionization detector |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| GC-TOF-MS | Gas chromatography combined with time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| HILIC | Hydrophilic interaction chromatography |

| HILIC-(U)HPLC | Hydrophilic interaction-high performance liquid chromatography |

| HILIC-ESI-MS | Hydrophilic interaction chromatography-electrospray-mass spectrometry |

| HILIC-MS | Hydrophilic interaction chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| IC | Ion chromatography |

| IC-MS/MS | Ion chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| IP | Ion paired |

| IP-HPLC-QqQ-MS/MS | Ion pared high performance liquid chromatography coupled with triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometry |

| IP-RP-(U)HPLC | Ion pared-reversed phase-(ultra) high performance liquid chromatography |

| iTRAQ | Isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| KIT | Tyrosine kinase |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| LC-Q-MS | Liquid chromatography-quadrupole mass spectrometry |

| LC-QqQ-MS | Liquid chromatography-triple quadrupole-mass spectrometry |

| LC-QqTOF | Liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer |

| LC-QqTOF-MS | Liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| LC-QTRAP | Liquid chromatography-quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer |

| MPP | Mass Profiler Professional |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| NGS | Next generation sequencing |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis |

| RP | Reversed phase |

| RPC | Reversed phase chromatography |

| RP-HPLC-MS | Reversed phase-high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| RP-LC-MS | Reversed phase-liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| RP-UHPLC | Reversed phase-ultra-high performance liquid chromatography |

| TCA cycle | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TMS | Trimethylsilyl |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| UHPLC | Ultra high performance liquid chromatography |

| UV-VIS | Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy |

| XICs | Extracted ion chromatograms |

References

- Hao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, E.; Yang, J.; Wang, S. Plant metabolomics: applications and challenges in the era of multi-omics big data. aBIOTECH 2025, 6, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Bhawal, R.; Yin, Z.; Thannhauser, T.W.; Zhang, S. Recent advances in proteomics and metabolomics in plants. Molecular Horticulture 2022, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klčová, B.; Balarynová, J.; Trněný, O.; Krejčí, P.; Cechová, M.Z.; Leonova, T.; Gorbach, D.; Frolova, N.; Kysil, E.; Orlova, A.; et al. Domestication has altered gene expression and secondary metabolites in pea seed coat. Plant J 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, N.; Gorbach, D.; Ihling, C.; Bilova, T.; Orlova, A.; Lukasheva, E.; Fedoseeva, K.; Dodueva, I.; Lutova, L.A.; Frolov, A. Proteome and Metabolome Alterations in Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) Seedlings Induced by Inoculation with Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jendoubi, T. Approaches to Integrating Metabolomics and Multi-Omics Data: A Primer. Metabolites 2021, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinu, F.R.; Beale, D.J.; Paten, A.M.; Kouremenos, K.; Swarup, S.; Schirra, H.J.; Wishart, D. Systems Biology and Multi-Omics Integration: Viewpoints from the Metabolomics Research Community. Metabolites 2019, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bais, P.; Moon, S.M.; He, K.; Leitao, R.; Dreher, K.; Walk, T.; Sucaet, Y.; Barkan, L.; Wohlgemuth, G.; Roth, M.R.; et al. PlantMetabolomics.org: A Web Portal for Plant Metabolomics Experiments. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, E.R.; Andersen, T.B.; Hamberger, B. Plant terpene specialized metabolism: complex networks or simple linear pathways? Plant J 2023, 114, 1178–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Osbourn, A.; Liu, Z. Understanding metabolic diversification in plants: branchpoints in the evolution of specialized metabolism. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2024, 379, 20230359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wase, N.; Abshire, N.; Obata, T. High-Throughput Profiling of Metabolic Phenotypes Using High-Resolution GC-MS. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2539, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, F.K.; Pandey, P.; Meitei, R.; Cardona, D.; Gujar, A.C.; Shulaev, V. GC-MS/MS Profiling of Plant Metabolites. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2396, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, Z.; Li, T.; Gao, H.; Zhu, H.; Gupta, V.K.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, X. Integrated Transcriptomic, Proteomic, and Metabolomics Analysis Reveals Peel Ripening of Harvested Banana under Natural Condition. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-N.; Pu, J.-C.; Liu, L.-X.; Wang, G.-W.; Zhou, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Xie, P. Integrated Metabolomics and Proteomics Analysis Revealed Second Messenger System Disturbance in Hippocampus of Chronic Social Defeat Stress Rat. Front Neurosci 2019, 13, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmolovskaya, N.; Bilova, T.; Gurina, A.; Orlova, A.; Vu, V.D.; Sukhikh, S.; Zhilkina, T.; Frolova, N.; Tarakhovskaya, E.; Kamionskaya, A.; et al. Metabolic Responses of Amaranthus caudatus Roots and Leaves to Zinc Stress. Plants (Basel) 2025, 14, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteggiano, A.; Occhipinti, A.; Capuzzo, A.; Mecarelli, E.; Aigotti, R.; Medana, C. Quali-Quantitative Characterization of Volatile and Non-Volatile Compounds in Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) Marchand Resin by GC-MS Validated Method, GC-FID and HPLC-HRMS2. Molecules 2021, 26, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitropoulos, M.-E.P.; Vasilopoulou, C.G.; Maga-Nteve, C.; Klapa, M.I. Untargeted GC-MS Metabolomics. Methods Mol Biol 2018, 1738, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisec, J.; Schauer, N.; Kopka, J.; Willmitzer, L.; Fernie, A.R. Gas chromatography mass spectrometry-based metabolite profiling in plants. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erban, A.; Martinez-Seidel, F.; Rajarathinam, Y.; Dethloff, F.; Orf, I.; Fehrle, I.; Alpers, J.; Beine-Golovchuk, O.; Kopka, J. Multiplexed Profiling and Data Processing Methods to Identify Temperature-Regulated Primary Metabolites Using Gas Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol 2020, 2156, 203–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolov, A.; Bilova, T.; Paudel, G.; Berger, R.; Balcke, G.U.; Birkemeyer, C.; Wessjohann, L.A. Early responses of mature Arabidopsis thaliana plants to reduced water potential in the agar-based polyethylene glycol infusion drought model. J Plant Physiol 2017, 208, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kumar, M.; Sircar, D.; Prasad, R. Metabolic profiling and biomarkers identification in cluster bean under drought stress using GC-MS technique. Metabolomics 2024, 20, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szablińska-Piernik, J.; Lahuta, L.B. Polar Metabolites Profiling of Wheat Shoots (Triticum aestivum L.) under Repeated Short-Term Soil Drought and Rewatering. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 8429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, E.V.S.; Pereira Dos Santos, N.G.; Vargas Medina, D.A.; Lanças, F.M. Electron ionization mass spectrometry: Quo vadis? Electrophoresis 2022, 43, 1587–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A.; Brennan, L.; Fiehn, O.; Hankemeier, T.; Kristal, B.S.; van Ommen, B.; Pujos-Guillot, E.; Verheij, E.; Wishart, D.; Wopereis, S. Mass-spectrometry-based metabolomics: limitations and recommendations for future progress with particular focus on nutrition research. Metabolomics 2009, 5, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, T.; Dobson, G.; Verrall, S.R.; Conner, S.; Griffiths, D.Wynne.; McNicol, J.W.; Davies, H.V.; Stewart, D. Potato metabolomics by GC–MS: what are the limiting factors? Metabolomics 2007, 3, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-T.; Yang, Y.; Sun, X.-L.; Ji, J. [Development of a widely-targeted metabolomics method based on gas chromatography-mass spectrometry]. Se Pu 2023, 41, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, D.J.; Pinu, F.R.; Kouremenos, K.A.; Poojary, M.M.; Narayana, V.K.; Boughton, B.A.; Kanojia, K.; Dayalan, S.; Jones, O.A.H.; Dias, D.A. Review of recent developments in GC-MS approaches to metabolomics-based research. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumilina, J.; Kiryushkin, A.S.; Frolova, N.; Mashkina, V.; Ilina, E.L.; Puchkova, V.A.; Danko, K.; Silinskaya, S.; Serebryakov, E.B.; Soboleva, A.; et al. Integrative Proteomics and Metabolomics Analysis Reveals the Role of Small Signaling Peptide Rapid Alkalinization Factor 34 (RALF34) in Cucumber Roots. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, D.; Pandita, A.; Wani, S.H.; Abdelmohsen, S.A.M.; Alyousef, H.A.; Abdelbacki, A.M.M.; Al-Yafrasi, M.A.; Al-Mana, F.A.; Elansary, H.O. Crosstalk of Multi-Omics Platforms with Plants of Therapeutic Importance. Cells 2021, 10, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, E.-M.; Xu, L.-Y. Guide to Metabolomics Analysis: A Bioinformatics Workflow. Metabolites 2022, 12, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Hidalgo, C.; Guerrero-Sánchez, V.M.; Gómez-Gálvez, I.; Sánchez-Lucas, R.; Castillejo-Sánchez, M.A.; Maldonado-Alconada, A.M.; Valledor, L.; Jorrín-Novo, J.V. A Multi-Omics Analysis Pipeline for the Metabolic Pathway Reconstruction in the Orphan Species Quercus ilex. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardans, J.; Gargallo-Garriga, A.; Urban, O.; Klem, K.; Walker, T.W.N.; Holub, P.; Janssens, I.A.; Peñuelas, J. Ecometabolomics for a Better Understanding of Plant Responses and Acclimation to Abiotic Factors Linked to Global Change. Metabolites 2020, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dokwal, D.; Cocuron, J.-C.; Alonso, A.P.; Dickstein, R. Metabolite shift in Medicago truncatula occurs in phosphorus deprivation. Journal of Experimental Botany 2022, 73, 2093–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Molina, A.; Pastor, V. Systemic analysis of metabolome reconfiguration in Arabidopsis after abiotic stressors uncovers metabolites that modulate defense against pathogens. Plant Communications 2023, 100645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeki, Ö.C.; Eylem, C.C.; Reçber, T.; Kır, S.; Nemutlu, E. Integration of GC–MS and LC–MS for untargeted metabolomics profiling. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2020, 190, 113509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Ma, C.; Huang, Y. GC–MS and LC-MS/MS metabolomics revealed dynamic changes of volatile and non-volatile compounds during withering process of black tea. Food Chemistry 2023, 410, 135396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, H.; Kudsk, P.; Ding, L.; Uthe, H.; Fomsgaard, I.S. Integrated LC–MS and GC–MS-Based Metabolomics Reveal the Effects of Plant Competition on the Rye Metabolome. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 3056–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, M.; Lou, J.; Zou, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Guo, D.; Yang, W. Pseudotargeted Metabolomics Approach Enabling the Classification-Induced Ginsenoside Characterization and Differentiation of Ginseng and Its Compound Formulation Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 1735–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixto, A.; Pérez-Parada, A.; Niell, S.; Heinzen, H. GC–MS and LC–MS/MS workflows for the identification and quantitation of pyrrolizidine alkaloids in plant extracts, a case study: Echium plantagineum. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 2019, 29, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Pang, Y.; An, P.; Jiang, G.; Kong, Q.; Ren, X. Determination of metabolites of Geotrichum citri-aurantii treated with peppermint oil using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Food Biochem 2019, 43, e12745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, S.; Hall, R.D.; De Vos, R.C.H.; Mumm, R.; Kadakal, Ç.; Capanoglu, E. Effect of drying treatments on the global metabolome and health-related compounds in tomatoes. Food Chemistry 2023, 403, 134123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeki, Ö.C.; Eylem, C.C.; Reçber, T.; Kır, S.; Nemutlu, E. Integration of GC-MS and LC-MS for untargeted metabolomics profiling. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2020, 190, 113509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- t’Kindt, R.; Morreel, K.; Deforce, D.; Boerjan, W.; Van Bocxlaer, J. Joint GC-MS and LC-MS platforms for comprehensive plant metabolomics: repeatability and sample pre-treatment. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2009, 877, 3572–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, H.; Kudsk, P.; Ding, L.; Uthe, H.; Fomsgaard, I.S. Integrated LC-MS and GC-MS-Based Metabolomics Reveal the Effects of Plant Competition on the Rye Metabolome. J Agric Food Chem 2022, 70, 3056–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koistinen, V.M.; Da Silva, A.B.; Abrankó, L.; Low, D.; Villalba, R.G.; Barberán, F.T.; Landberg, R.; Savolainen, O.; Alvarez-Acero, I.; De Pascual-Teresa, S.; et al. Interlaboratory Coverage Test on Plant Food Bioactive Compounds and their Metabolites by Mass Spectrometry-Based Untargeted Metabolomics. Metabolites 2018, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambhampati, S.; Li, J.; Evans, B.S.; Allen, D.K. Accurate and efficient amino acid analysis for protein quantification using hydrophilic interaction chromatography coupled tandem mass spectrometry. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.J.; Cameron, C.J.; Workman, R.; Broeckling, C.D.; Sumner, L.W.; Smith, J.T. Amino acid profiling in plant cell cultures: an inter-laboratory comparison of CE-MS and GC-MS. Electrophoresis 2007, 28, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halket, J.; Waterman, D.; Przyborowska, A.; Patel, R.; Fraser, P.; Bramley, P. Chemical derivatization and mass spectral libraries in metabolic profiling by GC/MS and LC/MS/MS. Journal of experimental botany 2005, 56, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lu, X.; Guo, X.; Guo, Q.; Li, D. Metabolomics Characterization of Two Apocynaceae Plants, Catharanthus roseus and Vinca minor, Using GC-MS and LC-MS Methods in Combination. Molecules 2017, 22, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénard, C.; Acket, S.; Rossez, Y.; Fernandez, O.; Berton, T.; Gibon, Y.; Cabasson, C. Untargeted Analysis of Semipolar Compounds by LC-MS and Targeted Analysis of Fatty Acids by GC-MS/GC-FID: From Plant Cultivation to Extract Preparation. In Plant Metabolomics; António, C., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2018; Vol. 1778, pp. 101–124. ISBN 978-1-4939-7818-2. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, M.K.; Pandey, S.; Kumar, M.; Haque, M.I.; Pal, S.; Yadav, N.S. Plants Metabolome Study: Emerging Tools and Techniques. Plants (Basel) 2021, 10, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiehn, O. Metabolomics by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry: Combined Targeted and Untargeted Profiling. CP Molecular Biology 2016, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, A.-M.; Reyes-Maldonado, O.K.; Puebla-Pérez, A.M.; Arreola, M.P.G.; Velasco-Ramírez, S.F.; Zúñiga-Mayo, V.; Sánchez-Fernández, R.E.; Delgado-Saucedo, J.-I.; Velázquez-Juárez, G. GC/MS Analysis, Antioxidant Activity, and Antimicrobial Effect of Pelargonium peltatum (Geraniaceae). Molecules 2022, 27, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naz, R.; Roberts, T.H.; Bano, A.; Nosheen, A.; Yasmin, H.; Hassan, M.N.; Keyani, R.; Ullah, S.; Khan, W.; Anwar, Z. GC-MS analysis, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antilipoxygenase and cytotoxic activities of Jacaranda mimosifolia methanol leaf extracts and fractions. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalraj, S.; Murugan, R.; Gangapriya, P.; Krupa, J.; Divya, M.; Gurav, S.S.; Ayyanar, M. Evaluation of phytochemicals, enzyme inhibitory, antibacterial and antioxidant effects of Psydrax dicoccos Gaertn. Natural Product Research 2022, 36, 5772–5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanigan, I.L.; MacLeod, J.K.; Williams, J.F. A re-investigation of the path of carbon in photosynthesis utilizing GC/MS methodology. Unequivocal verification of the participation of octulose phosphates in the pathway. Photosynth Res 2006, 90, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, N.S.; Mendis, H.; Roessner, U.; Dias, D.A. Quantification of Sugars and Organic Acids in Biological Matrices Using GC-QqQ-MS. In Plant Metabolomics; António, C., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2018; Vol. 1778, pp. 207–223. ISBN 978-1-4939-7818-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Matute, A.I.; Hernández-Hernández, O.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, S.; Sanz, M.L.; Martínez-Castro, I. Derivatization of carbohydrates for GC and GC-MS analyses. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2011, 879, 1226–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D.J. Derivatization of carbohydrates for analysis by chromatography; electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography B 2011, 879, 1196–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Liang, J.; Guo, Y.-L.; Li, Y.; Kuang, H.-X.; Xia, Y.-G. Ultrafiltration isolation, structures and anti-tumor potentials of two arabinose- and galactose-rich pectins from leaves of Aralia elata. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 255, 117326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandi, B.; Baldassarre, S.; Babbar, N.; Bancalari, E.; Vandezande, P.; Hermans, D.; Bruggeman, G.; Gatti, M.; Elst, K.; Sforza, S. Pectin oligosaccharides from sugar beet pulp: molecular characterization and potential prebiotic activity. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipke, I.; Bücker, L.; Middelstaedt, J.; Winterhalter, P.; Lubienski, M.; Beuerle, T. HILIC HPLC-ESI-MS/MS identification and quantification of the alkaloids from the genus Equisetum. Phytochemical Analysis 2019, 30, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letzel, T.; Grassmann, J.; Wahman, R.; Schröder, P. Plant Metabolomic Workflows Using Reversed-Phase LC and HILIC with ESI-TOF-MS. 2019, 34, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mathon, C.; Barding, G.A.; Larive, C.K. Separation of ten phosphorylated mono-and disaccharides using HILIC and ion-pairing interactions. Analytica Chimica Acta 2017, 972, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koley, S.; Chu, K.L.; Gill, S.S.; Allen, D.K. An efficient LC-MS method for isomer separation and detection of sugars, phosphorylated sugars, and organic acids. Journal of Experimental Botany 2022, 73, 2938–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellaneta, A.; Losito, I.; Losacco, V.; Leoni, B.; Santamaria, P.; Calvano, C.D.; Cataldi, T.R.I. HILIC-ESI-MS analysis of phosphatidic acid methyl esters artificially generated during lipid extraction from microgreen crops. J Mass Spectrom 2021, 56, e4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hájek, R.; Lísa, M.; Khalikova, M.; Jirásko, R.; Cífková, E.; Študent, V.; Vrána, D.; Opálka, L.; Vávrová, K.; Matzenauer, M.; et al. HILIC/ESI-MS determination of gangliosides and other polar lipid classes in renal cell carcinoma and surrounding normal tissues. Anal Bioanal Chem 2018, 410, 6585–6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Zou, L.; Yin, X.; Ong, C.N. HILIC-MS for metabolomics: An attractive and complementary approach to RPLC-MS. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 2016, 35, 574–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macioszek, S.; Dudzik, D.; Biesemans, M.; Wozniak, A.; Schöffski, P.; Markuszewski, M.J. A multiplatform metabolomics approach for comprehensive analysis of GIST xenografts with various KIT mutations. Analyst 2023, 148, 3883–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, T.; Tolstikov, V.; Fiehn, O.; Weiss, R.H. A comprehensive urinary metabolomic approach for identifying kidney cancerr. Anal Biochem 2007, 363, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddaiah, C.; Kumar Bm, A.; Deepak, S.A.; Lateef, S.S.; Nagpal, S.; Rangappa, K.S.; Mohan, C.D.; Rangappa, S.; Kumar S, M.; Sharma, M.; et al. Metabolite Profiling of Alangium salviifolium Bark Using Advanced LC/MS and GC/Q-TOFTechnology. Cells 2020, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandera, P. Stationary and mobile phases in hydrophilic interaction chromatography: a review. Analytica Chimica Acta 2011, 692, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, Y.; Ikegami, T.; Takubo, H.; Ikegami, Y.; Miyamoto, M.; Tanaka, N. Chromatographic characterization of hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography stationary phases: Hydrophilicity, charge effects, structural selectivity, and separation efficiency. Journal of Chromatography A 2011, 1218, 5903–5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCalley, D.V. Study of the selectivity, retention mechanisms and performance of alternative silica-based stationary phases for separation of ionised solutes in hydrophilic interaction chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A 2010, 1217, 3408–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolci, M. Technical Note: Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography: Some Aspects of Solvent and Column Selectivity.

- Li, H.; Liu, C.; Zhao, L.; Xu, D.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Q.; Cabooter, D.; Jiang, Z. A systematic investigation of the effect of sample solvent on peak shape in nano- and microflow hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography columns. J Chromatogr A 2021, 1655, 462498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumpochova, P.; Bruyneel, B.; Molenaar, D.; Koukou, A.; Wuhrer, M.; Niessen, W.M.A.; Giera, M. Amino acid analysis using chromatography-mass spectrometry: An inter platform comparison study. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2015, 114, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Rochfort, S. Recent progress in polar metabolite quantification in plants using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. JIPB 2014, 56, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Almazán, N.; Zarazúa-Ortega, G.; Ávila-Pérez, P.; Barrera-Díaz, C.E.; Cedillo-Cruz, A. Validation and uncertainty estimation of analytical method for quantification of phytochelatins in aquatic plants by UPLC-MS. Phytochemistry 2021, 183, 112643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, F.; Geng, H.; Yang, B. A hydrolytically stable amide polar stationary phase for hydrophilic interaction chromatography. Talanta 2021, 231, 122340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, P.K.; Ramisetti, N.R.; Cecchi, T.; Swain, S.; Patro, C.S.; Panda, J. An overview of experimental designs in HPLC method development and validation. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2018, 147, 590–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donegan, M.; Nguyen, J.M.; Gilar, M. Effect of ion-pairing reagent hydrophobicity on liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis of oligonucleotides. Journal of Chromatography A 2022, 1666, 462860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajad, S.U.; Lu, W.; Kimball, E.H.; Yuan, J.; Peterson, C.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Separation and quantitation of water soluble cellular metabolites by hydrophilic interaction chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A 2006, 1125, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcke, G.U.; Bennewitz, S.; Bergau, N.; Athmer, B.; Henning, A.; Majovsky, P.; Jiménez-Gómez, J.M.; Hoehenwarter, W.; Tissier, A. Multi-Omics of Tomato Glandular Trichomes Reveals Distinct Features of Central Carbon Metabolism Supporting High Productivity of Specialized Metabolites. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 960–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, L. Comparing ion-pairing reagents and counter anions for ion-pair reversed-phase liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analysis of synthetic oligonucleotides. Rapid Comm Mass Spectrometry 2015, 29, 2402–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietl, K.; Renner, K.; Dettmer, K.; Timischl, B.; Eberhart, K.; Dorn, C.; Hellerbrand, C.; Kastenberger, M.; Kunz-Schughart, L.A.; Oefner, P.J.; et al. Lactic Acid and Acidification Inhibit TNF Secretion and Glycolysis of Human Monocytes. The Journal of Immunology 2010, 184, 1200–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumilina, J.; Kiryushkin, A.S.; Frolova, N.; Mashkina, V.; Ilina, E.L.; Puchkova, V.A.; Danko, K.; Silinskaya, S.; Serebryakov, E.B.; Soboleva, A.; et al. Integrative Proteomics and Metabolomics Analysis Reveals the Role of Small Signaling Peptide Rapid Alkalinization Factor 34 (RALF34) in Cucumber Roots. IJMS 2023, 24, 7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.; Soufan, O.; Li, C.; Caraus, I.; Li, S.; Bourque, G.; Wishart, D.S.; Xia, J. MetaboAnalyst 4.0: towards more transparent and integrative metabolomics analysis. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46, W486–W494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Hu, C.; Li, W.; Peng, X.; et al. A metabolomics study delineating geographical location-associated primary metabolic changes in the leaves of growing tobacco plants by GC-MS and CE-MS. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 16346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Gulersonmez, M.C.; Hankemeier, T.; Ramautar, R. Sheathless Capillary Electrophoresis; Mass Spectrometry for Metabolic Profiling of Biological Samples. JoVE 2016, 54535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, J.N.; John, K.M.M.; Kusano, M.; Oikawa, A.; Saito, K.; Lee, C.H. GC–TOF-MS- and CE–TOF-MS-Based Metabolic Profiling of Cheonggukjang (Fast-Fermented Bean Paste) during Fermentation and Its Correlation with Metabolic Pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9746–9753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniakiewicz, M.; Woźniakiewicz, A.; Nowak, P.M.; Kłodzińska, E.; Namieśnik, J.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. CE-MS and GC-MS as “Green” and Complementary Methods for the Analysis of Biogenic Amines in Wine. Food Anal. Methods 2018, 11, 2614–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, J.C.; Ras, C.; Ten Pierick, A. Analysis of Glycolytic Intermediates with Ion Chromatography- and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. In Metabolic Profiling; Metz, T.O., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2011; Vol. 708, pp. 131–146. ISBN 978-1-61737-984-0. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, D.D.; Powers, R. Beyond the paradigm: Combining mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance for metabolomics. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy 2017, 100, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebrilla, C.B.; Liu, J.; Widmalm, G.; Prestegard, J.H. Oligosaccharides and Polysaccharides. In Essentials of Glycobiology; Varki, A., Cummings, R.D., Esko, J.D., Stanley, P., Hart, G.W., Aebi, M., Mohnen, D., Kinoshita, T., Packer, N.H., Prestegard, J.H., Schnaar, R.L., Seeberger, P.H., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor (NY), 2022; ISBN 978-1-62182-421-3. [Google Scholar]

- Si, H.-Y.; Chen, N.-F.; Chen, N.-D.; Huang, C.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Structural characterisation of a water-soluble polysaccharide from tissue-cultured Dendrobium huoshanense C.Z. Tang et S.J. Cheng. Nat Prod Res 2018, 32, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, Y.; Inaoka, H.; Takei, A.; Sugimura, Y.; Otsuji, K. Extracellular polysaccharides produced by tuberose callus. Phytochemistry 1996, 41, 1517–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emwas, A.-H.; Roy, R.; McKay, R.T.; Tenori, L.; Saccenti, E.; Gowda, G.A.N.; Raftery, D.; Alahmari, F.; Jaremko, L.; Jaremko, M.; et al. NMR Spectroscopy for Metabolomics Research. Metabolites 2019, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhinderwala, F.; Wase, N.; DiRusso, C.; Powers, R. Combining Mass Spectrometry and NMR Improves Metabolite Detection and Annotation. J. Proteome Res. 2018, 17, 4017–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larive, C.K.; Barding, G.A.; Dinges, M.M. NMR Spectroscopy for Metabolomics and Metabolic Profiling. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, C.; Patin, F.; Bocca, C.; Nadal-Desbarats, L.; Bonnier, F.; Reynier, P.; Emond, P.; Vourc’h, P.; Joseph-Delafont, K.; Corcia, P.; et al. The combination of four analytical methods to explore skeletal muscle metabolomics: Better coverage of metabolic pathways or a marketing argument? Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2018, 148, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barding, G.A.; Béni, S.; Fukao, T.; Bailey-Serres, J.; Larive, C.K. Comparison of GC-MS and NMR for Metabolite Profiling of Rice Subjected to Submergence Stress. J. Proteome Res. 2013, 12, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Raftery, D. Comparing and combining NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry in metabolomics. Anal Bioanal Chem 2007, 387, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.; Technologies, A. Method Manager for Streamlined Statistical Analysis and Model Building.

- Alrabie, A.; Alrabie, N.A.; AlSaeedy, M.; Al-Adhreai, A.; Al-Qadsy, I.; Al-Horaibi, S.A.; Alaizeri, Z.M.; Alhadlaq, H.A.; Ahamed, M.; Farooqui, M. An integrative GC–MS and LC–MS metabolomics platform determination of the metabolite profile of Bombax ceiba L. root, and in silico & in vitro evaluation of its antibacterial & antidiabetic activities. Natural Product Research 2023, 37, 2263–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam, A.; Kudapa, H.; Pazhamala, L.T.; Weckwerth, W.; Varshney, R.K. Proteomics and Metabolomics: Two Emerging Areas for Legume Improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-N.; Pu, J.-C.; Liu, L.-X.; Wang, G.-W.; Zhou, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Xie, P. Integrated Metabolomics and Proteomics Analysis Revealed Second Messenger System Disturbance in Hippocampus of Chronic Social Defeat Stress Rat. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Z.; Li, T.; Gao, H.; Zhu, H.; Gupta, V.K.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, X. Integrated Transcriptomic, Proteomic, and Metabolomics Analysis Reveals Peel Ripening of Harvested Banana under Natural Condition. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonova, T.; Popova, V.; Tsarev, A.; Henning, C.; Antonova, K.; Rogovskaya, N.; Vikhnina, M.; Baldensperger, T.; Soboleva, A.; Dinastia, E.; et al. Does Protein Glycation Impact on the Drought-Related Changes in Metabolism and Nutritional Properties of Mature Pea (Pisum sativum L.) Seeds? IJMS 2020, 21, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharjee, A.; Kloosterman, B.; Visser, R.G.F.; Maliepaard, C. Integration of multi-omics data for prediction of phenotypic traits using random forest. BMC Bioinformatics 2016, 17, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhinderwala, F.; Wase, N.; DiRusso, C.; Powers, R. Combining Mass Spectrometry and NMR Improves Metabolite Detection and Annotation. J Proteome Res 2018, 17, 4017–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniakiewicz, M.; Woźniakiewicz, A.; Nowak, P.M.; Kłodzińska, E.; Namieśnik, J.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. CE-MS and GC-MS as “Green” and Complementary Methods for the Analysis of Biogenic Amines in Wine. Food Anal. Methods 2018, 11, 2614–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strenkert, D.; Schmollinger, S.; Gallaher, S.D.; Salomé, P.A.; Purvine, S.O.; Nicora, C.D.; Mettler-Altmann, T.; Soubeyrand, E.; Weber, A.P.M.; Lipton, M.S.; et al. Multiomics resolution of molecular events during a day in the life of Chlamydomonas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116, 2374–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Alseekh, S.; Xiao, T.; Ablazov, A.; Perez De Souza, L.; Fiorilli, V.; Anggarani, M.; Lin, P.-Y.; Votta, C.; Novero, M.; et al. Multi-omics approaches explain the growth-promoting effect of the apocarotenoid growth regulator zaxinone in rice. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larrainzar, E.; Wienkoop, S.; Weckwerth, W.; Ladrera, R.; Arrese-Igor, C.; González, E.M. Medicago truncatula Root Nodule Proteome Analysis Reveals Differential Plant and Bacteroid Responses to Drought Stress. Plant Physiology 2007, 144, 1495–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Hidalgo, C.; Guerrero-Sánchez, V.M.; Gómez-Gálvez, I.; Sánchez-Lucas, R.; Castillejo-Sánchez, M.A.; Maldonado-Alconada, A.M.; Valledor, L.; Jorrín-Novo, J.V. A Multi-Omics Analysis Pipeline for the Metabolic Pathway Reconstruction in the Orphan Species Quercus ilex. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendoubi, T. Approaches to Integrating Metabolomics and Multi-Omics Data: A Primer. Metabolites 2021, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.K.; Zhao, H.; Pang, H. A comparison of graph- and kernel-based –omics data integration algorithms for classifying complex traits. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanckriet, G.R.G.; Deng, M.; Cristianini, N.; Jordan, M.I.; Noble, W.S. Kernel-based data fusion and its application to protein function prediction in yeast. In Proceedings of the Biocomputing 2004; WORLD SCIENTIFIC, Hawaii, USA, 2003; pp. 300–311. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Wang, J.; Lv, H.; Peng, Q.; Schreiner, M.; Baldermann, S.; Lin, Z. Integrated proteomic and metabolomic analyses reveal the importance of aroma precursor accumulation and storage in methyl jasmonate-primed tea leaves. Hortic Res 2021, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Roger, J.M.; Jouan-Rimbaud-Bouveresse, D.; Biancolillo, A.; Marini, F.; Nordon, A.; Rutledge, D.N. Recent trends in multi-block data analysis in chemometrics for multi-source data integration. TrAC - Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2021, 137, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).