Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

14 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Photovoltaic and Wind-Driven Pumping Systems

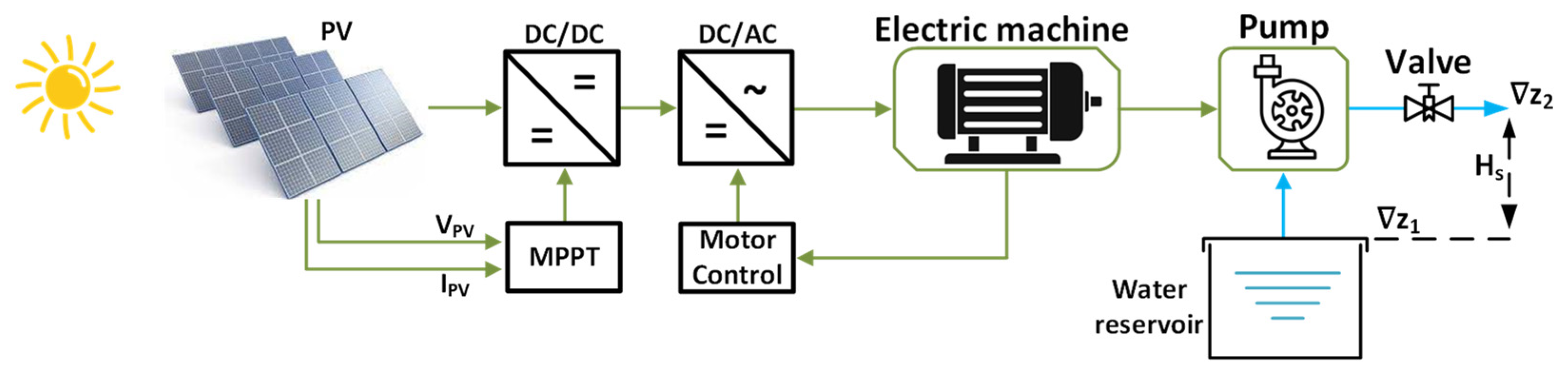

2.1. Photovoltaic Pumping System

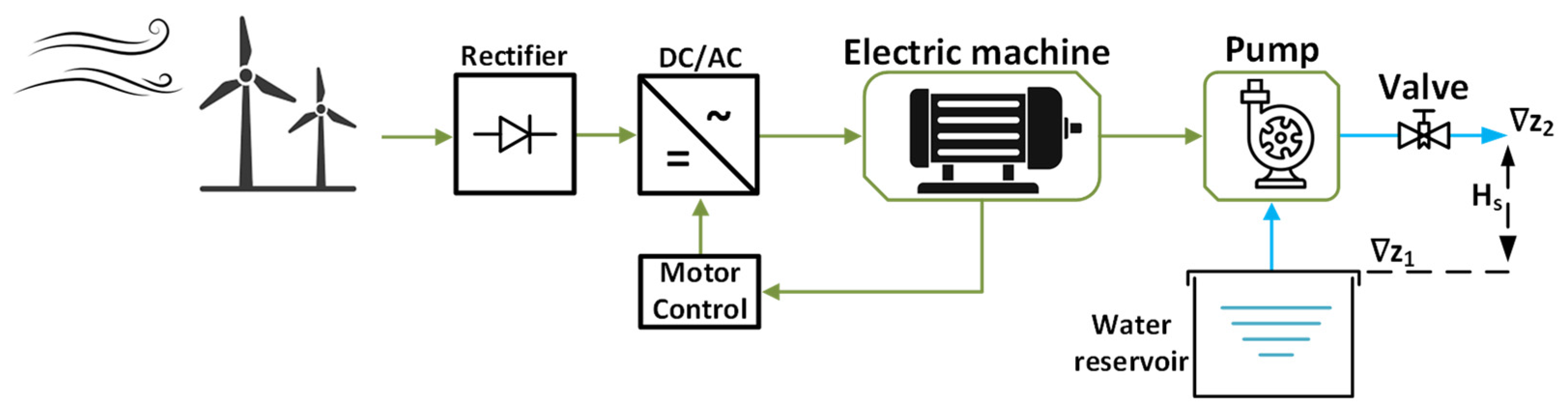

2.2. Wind Turbine (WT) Pumping System

2.3. Hybrid Pumping Systems

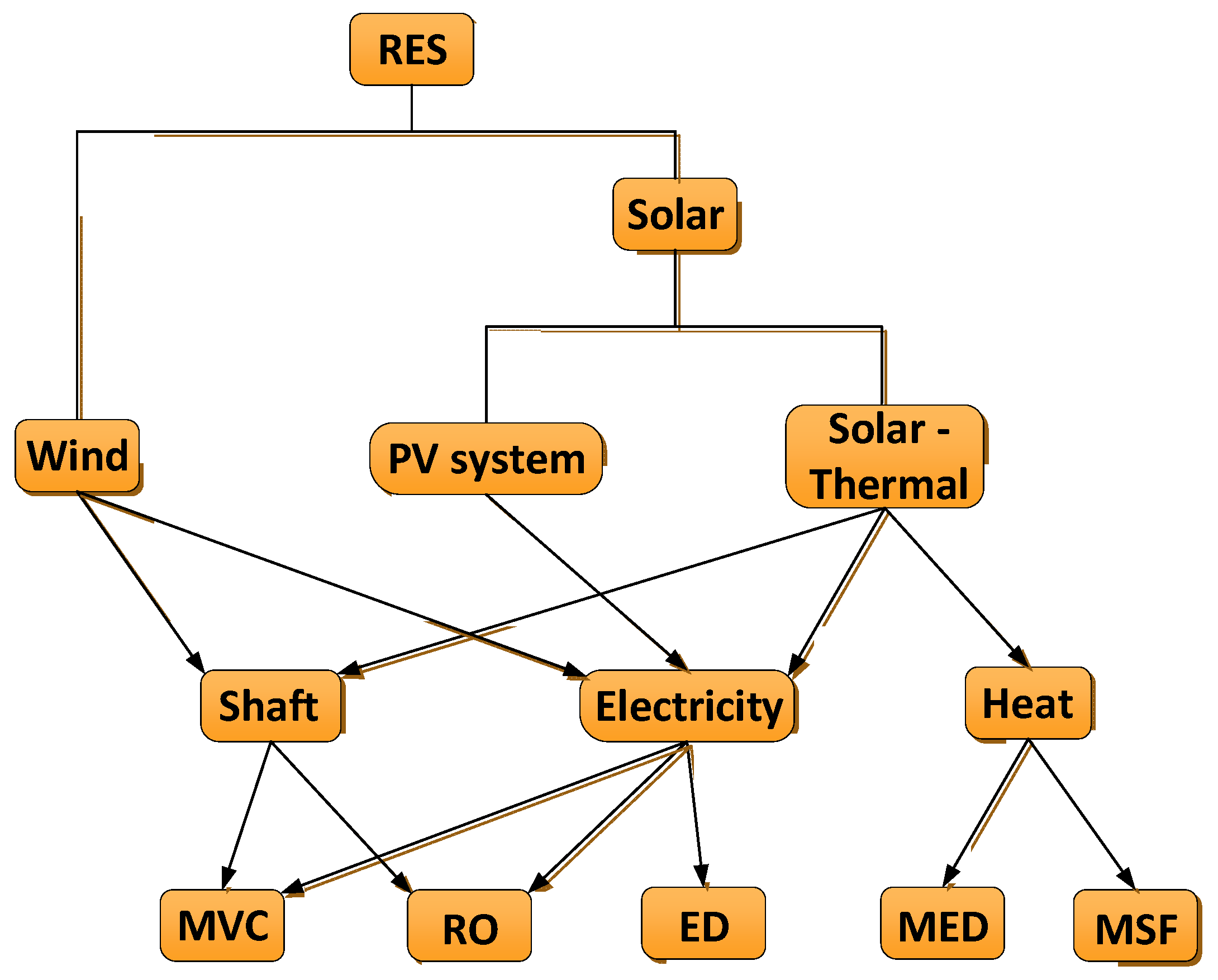

3. PV/Wind-Powered Pumping Systems for Desalination Applications

3.1. Overview of Desalination Technologies

3.1.1. Mechanical Vapour Compression (MVC)

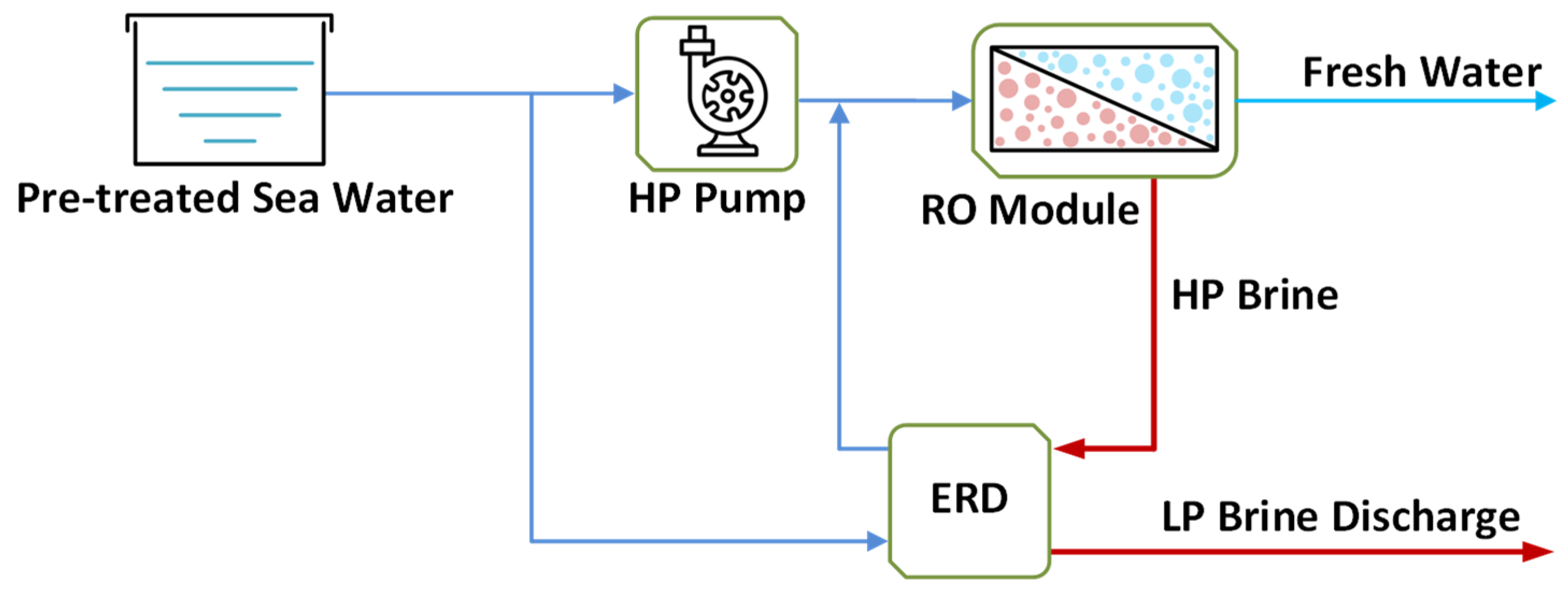

3.1.2. Reverse Osmosis (RO)

3.1.3. Electrodialysis (ED)

3.1.4. Multi-Effect Distillation (MED)

3.1.5. Multi-Stage Flash Distillation (MSF)

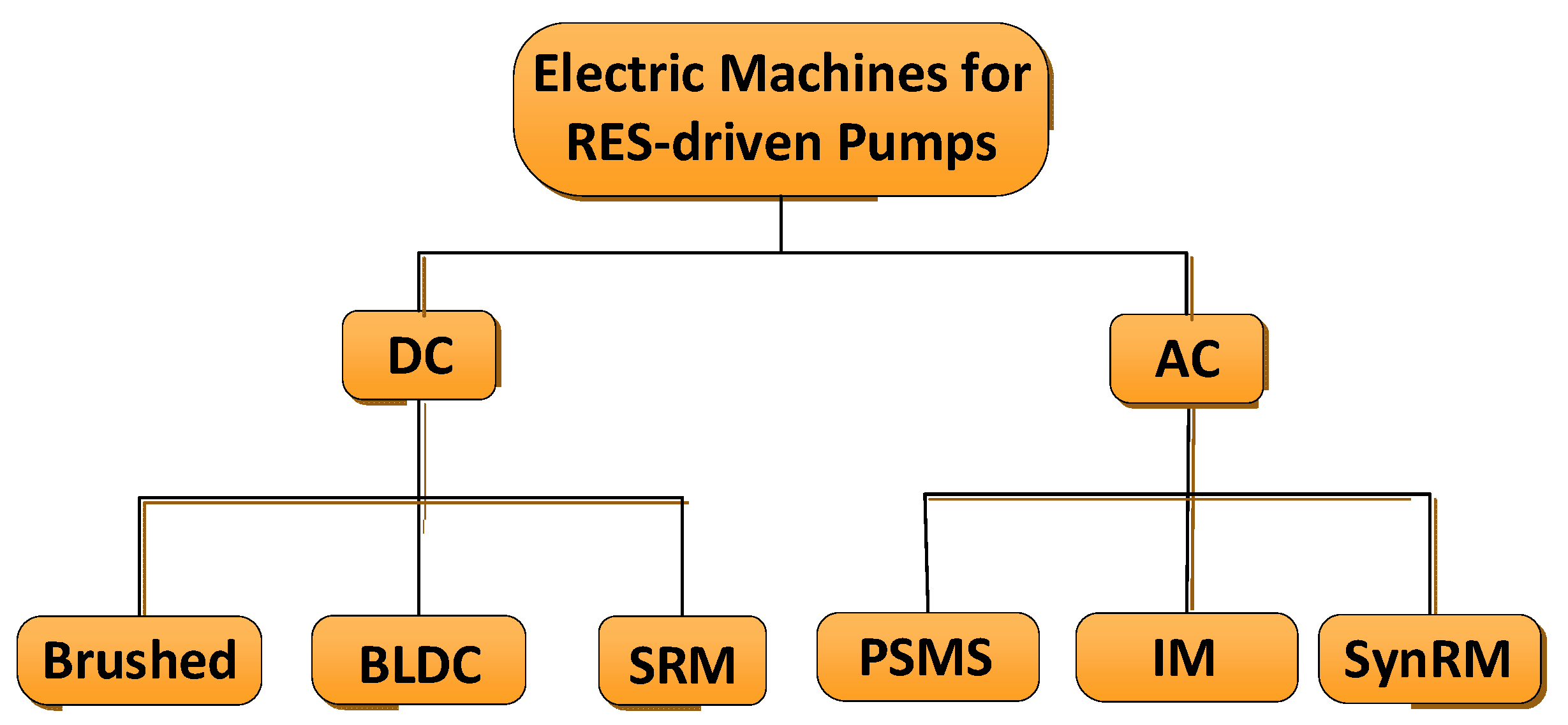

3.2. Electrical Machines for Pump Drives

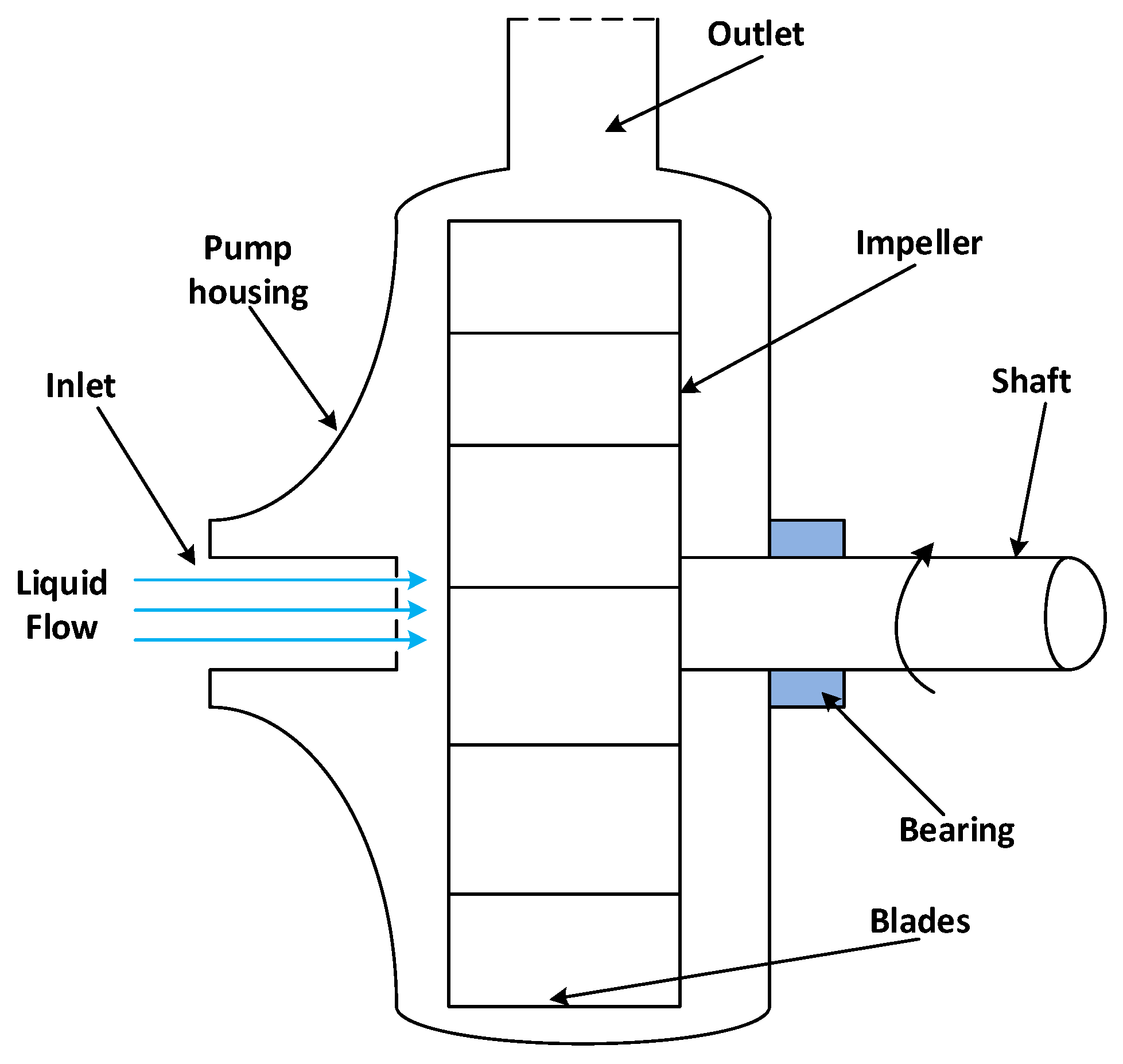

3.3. Centrifugal Pump Technologies

3.4. Energy Recovery Devices for Reverse Osmosis

3.4.1. Operating Principles

- Centrifugal Devices: These devices function as hydraulic turbines. The high-pressure (HP) brine spins a turbine, such as a Francis or Pelton wheel, and the recovered mechanical energy is used to assist in driving the high-pressure pump via a common shaft (in a turbocharger configuration) or a generator [62]. While simple, their efficiency is highly dependent on flow rate and pressure, making them less efficient at part-load operation compared to positive displacement types.

- Positive Displacement (Isobaric) Devices: This class dominates modern large-scale RO due to higher efficiency across a wider operating range [63]. They operate on the principle of direct pressure exchange from the brine to the feed seawater with minimal fluid mixing:

- Rotary Pressure Exchanger (PX): The most prevalent technology, exemplified by the ERI PX. It consists of a ceramic rotor with multiple axial ducts spinning inside a sleeve. Brine and seawater flow into opposite ends of the ducts, and the rotating rotor alternately aligns them with high- and low-pressure ports, enabling near-isobaric transfer. Efficiency typically exceeds 94%.

- Reciprocating Work Exchanger: Such as the DWEER system. It uses hydraulic pistons or cylinders. High-pressure brine acts on one side of a piston, directly pressurizing seawater on the other side. Valves control the alternating intake and discharge cycles.

- Integrated Piston Pumps (Multi-Functional ERDs): A significant advancement for small to medium-scale systems, where the ERD, booster pump, and sometimes even the main high-pressure pump are integrated into a single device. These use multiple radial or axial pistons driven by a common crankshaft or motor. The pistons perform a dual function: some cylinders pressurize feed seawater using motor power, while others recover energy from the brine stream. This integration reduces footprint, capital cost, and complexity, offering robust, particle-tolerant operation ideal for marine or remote applications.

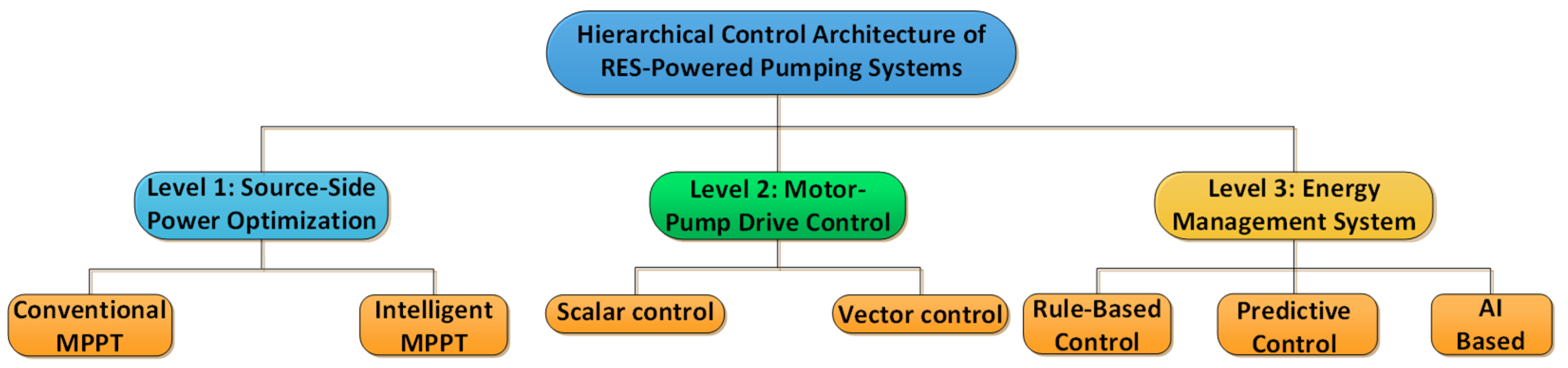

4. Control and Energy Management of Pumping Systems

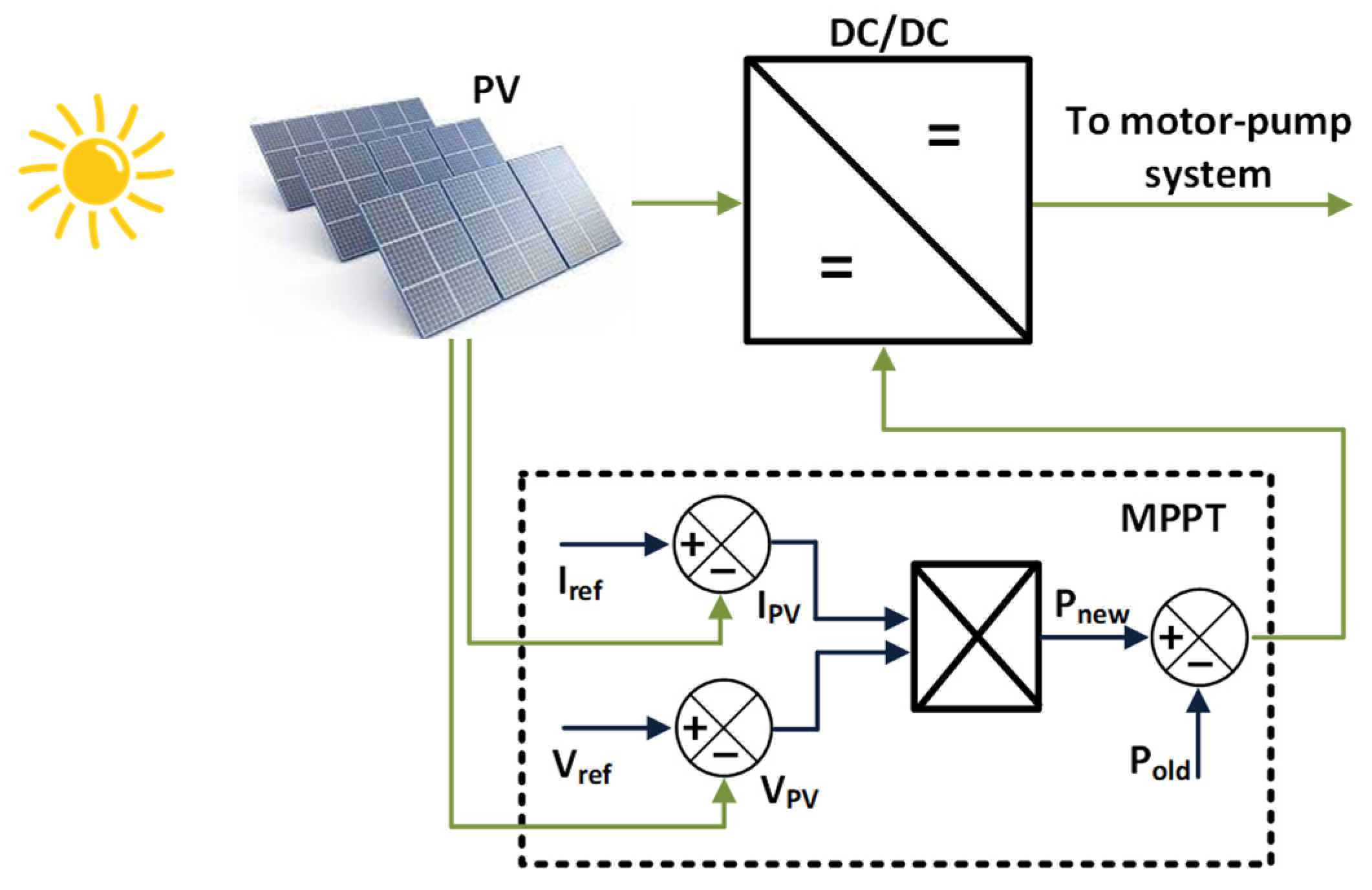

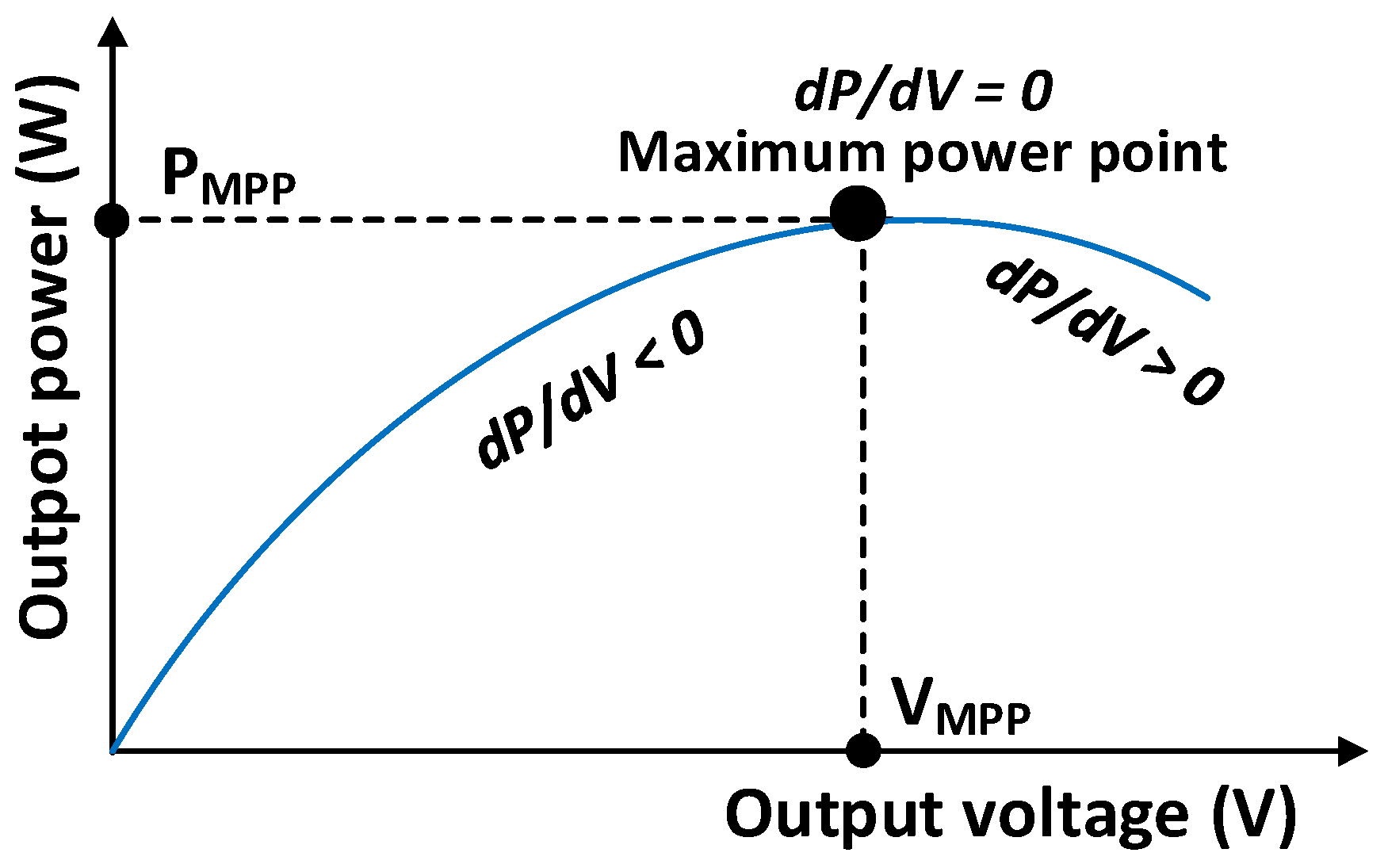

4.1. Conventional and Intelligent MPPT Control

4.1.1. P&O

4.1.2. Incremental Conductance (IC) Method

4.1.3. Constant Voltage (CV)/Constant Current (CC) Methods

4.1.4. Fuzzy Logic Control (FLC) for MPPT

4.2. Motor-Pump Drive Control

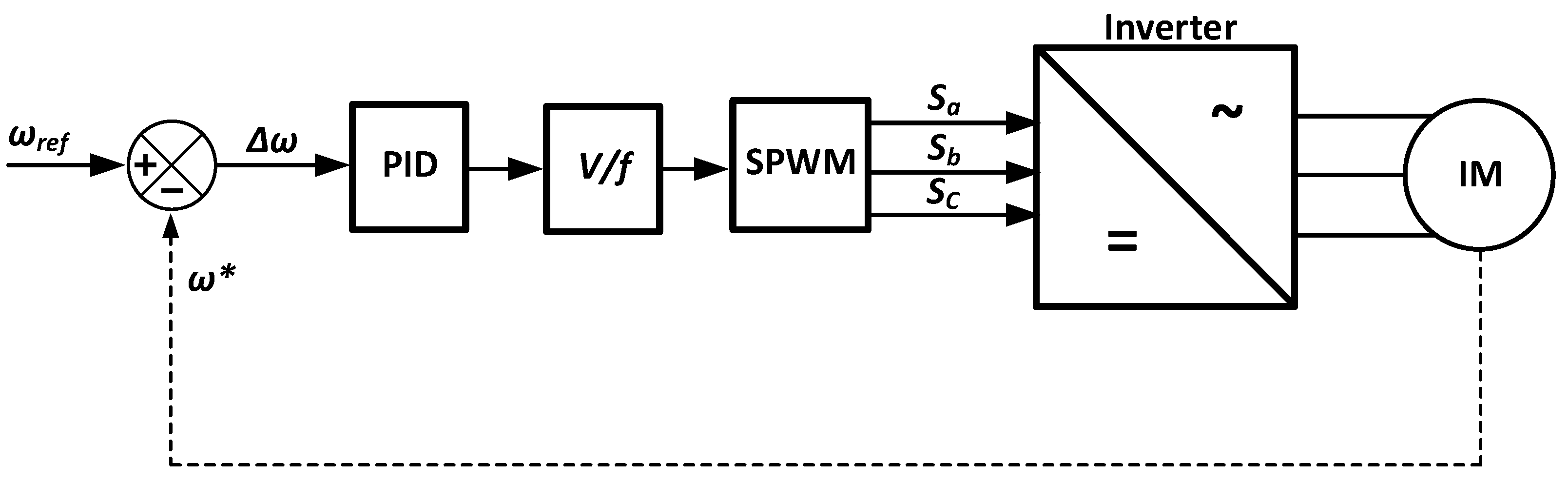

4.2.1. Scalar Control (SC)

4.2.2. Field-Oriented Control (FOC)

4.2.3. Direct Torque Control (DTC)

4.3. Energy Management System (EMS)

4.3.1. Rule-Based (RUL) Control

4.3.2. Predictive Control

4.3.3. Artificial Intelligence-Based Control

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Alternating Current |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANFIS | Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| BLDC | Brushless DC |

| BOS | Balance of System |

| CC | Constant Current |

| CV | Constant Voltage |

| DC | Direct Current |

| DFOC | Direct FOC |

| DP | Dynamic Programming |

| ED | Electrodialysis |

| EMF | Electromotive Force |

| EMI | Electromagnetic Interference |

| EMS | Energy Management System |

| ERD | Energy Recovery Devices |

| FLC | Fuzzy Logic Control |

| FOC | Field-Oriented Control |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| HAWT | Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines |

| HC | Hill Climbing |

| HIL | Hardware-in-the-Loop |

| IFOC | Indirect FOC |

| IC | Incremental Conductance |

| IM | Induction Motor |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Energy |

| LCOW | Levelized Cost of Water |

| MED | Multi Effect Distillation |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MPPT | Maximum Power Point Tracking |

| MSF | Multi-Stage Flash Distillation |

| MVC | Mechanical Vapour Compression |

| OC | Open Circuit |

| PAT | Pump-as-Turbine |

| PEC | Power Electronic Converter |

| PEMFC | Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell |

| PMSM | Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines |

| P&O | Perturb & Observe |

| PRO | Pressure Retarded Osmosis |

| PSC | Perovskite Solar Cell |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PWM | Pulse-Width Modulation |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RUL | Rule-Based |

| RO | Reverse Osmosis |

| SC | Scalar Control |

| SCIM | Squirrel-Cage Induction Motors |

| SEC | Specific Energy Consumption |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| SPWM | Sinewave Pulse Width Modulation |

| SPWP | Solar Photovoltaic Water Pump |

| SRM | Switched Reluctance Motors |

| STC | Standard Test Condition |

| SVM | Space Vector Modulation |

| TDS | Total Dissolved Solids |

| THD | Total Harmonic Distortion |

| TMP | Transmembrane Pressure |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VAWT | Vertical Axis Wind Turbines |

| VFD | Variable Frequency Drives |

| VSC | Voltage Source Converter |

| VSI | Voltage Source Inverter |

| WPWPS | Wind Powered Water Pumping System |

| WT | Wind Turbine |

References

- Available online: https://www.energy.gov/gc/articles/overview-pump-systems-matter (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Flörke, M.; Schneider, C.; McDonald, R.I. Water competition between cities and agriculture driven by climate change and urban growth. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, D.I.; Rojas Espinoza, J.; Flores-Vázquez, C.; Cárdenas, A. A Hybrid System That Integrates Renewable Energy for Groundwater Pumping with Battery Storage, Innovative in Rural Communities. Energies 2025, 18, 5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilali, A.; Mardoude, Y.; Essahlaoui, A.; Rahali, A.; El Ouanjli, N. Migration to solar water pump system: Environmental and economic benefits and their optimization using genetic algorithm Based MPPT. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 10144–10153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Mishra, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Gaur, A.; Mohapatra, S.; Soni, A.; Verma, P. Solar PV powered water pumping system–A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 46, 5601–5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Smidl, V. Simulation Model for Efficiency Estimation of Photovoltaic Water Pumping System. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium INFOTEH-JAHORINA (INFOTEH), East Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 18–20 March 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Huo, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, M. Synergistic Regulation of Water–Land–Energy–Food–Carbon Nexus in Large Agricultural Irrigation Areas. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Romero, L.T. Review on Solar Photovoltaic-Powered Pumping Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/evolution-of-solar-pv-module-cost-by-data-source-1970-2020 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Lidorenko, N.; Nabiullin, F.; Tarnizhevsky, B. Experimental solar power plant [for powering electric pump]. Geliotekhnika 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Tarnizhevsky, B.; Rodichev, B. Test results for solar energy installations with photoelectric converters [for powering electric pump]. Geliotekhnika 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Tarnizhevsky, B.; Rodichev, B. Characteristics of water lifting system powered from solar energy plants. Geliotekhnika 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Boudjerda, T.; Belaid, S.L.; Tamalouzt, S.; Belkhier, Y.; Benbouzid, M. Energy Management for an Explored Water Pumping Topology Powered by Solar and Wind Energy with Battery Storage System. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 28, 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Trilla, L. The Synergy of Renewable Energy and Desalination: An Overview of Current Practices and Future Directions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Kirpichnikova, I. Model of Solar Photovoltaic Water Pumping System for Domestic Application. In Proceedings of the 2021 28th International Workshop on Electric Drives: Improving Reliability of Electric Drives (IWED), Moscow, Russia, 27–29 January 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Roboam, X.; Sareni, B.; Nguyen, D.T.; Belhadj, J. Optimal System Management of a Water Pumping and Desalination Process Supplied with Intermittent Renewable Sources. In Proceedings of the 4th IFAC Conference on Sustainability in the Process Industry (Sustaining), Antwerp, Belgium, 2–4 September 2012; Volume 8, pp. 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Id Ouissaaden, F.; Kamel, H.; Dlimi, S. Simulation and Performance Evaluation of a Photovoltaic Water Pumping System with Hybrid Maximum Power Point Technique (MPPT) for Remote Rural Areas. Processes 2025, 13, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodovozov, V.; Gevorkov, L.; Raud, Z. Modeling and Analysis of Pumping Motor Drives in Hardware-in-the-Loop Environment. J. Power Energy Eng. 2014, 2, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L. Experimental Hardware-in-the-Loop Centrifugal Pump Simulator for Laboratory Purposes. Processes 2023, 11, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Šmídl, V.; Sirový, M. Model of Hybrid Speed and Throttle Control for Centrifugal Pump System Enhancement. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 28th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–14 June 2019; pp. 563–568. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanujam, J.; Bishop, D.M.; Todorov, T.K.; Gunawan, O.; Rath, J.; Nekovei, R.; Artegiani, E.; Romeo, A. Flexible CIGS, CdTe and a-Si:H based thin film solar cells: A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020, 110, 100619. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Peng, R.; Ren, K.; Yu, L.; Jiang, Q.; Shen, Z.; Yue, S.; Wang, Z. Development of High-Efficiency Perovskite Solar Cells and Their Integration with Machine Learning. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Mao, L. A Review on Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Solar Cells: Current Status and Future Challenges. Energies 2025, 18, 4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalva, M.G.; Gazoli, J.R.; Filho, E.R. Comprehensive Approach to Modeling and Simulation of Photovoltaic Arrays. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmagid, T.I.M.; Siddig, M.H. Wind-Driven Pumped Storage System Design. Wind. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsiou, M.M.; Baltas, E. Power to Hydrogen and Power to Water Using Wind Energy. Wind 2022, 2, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazylova, A.; Alipbayev, K.; Aden, A.; Oraz, F.; Iliev, T.; Stoyanov, I. A Comparative Review of Vertical Axis Wind Turbine Designs: Savonius Rotor vs. Darrieus Rotor. Inventions 2025, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testi, A.; de Souza, T.M.; de Barros Trannin, I.C. Technical and Economic Feasibility of a Small Vertical Axis Wind Turbine in Low Wind Conditions Compared to Other Power Sources for Pumping Water. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rotta, J.; Pinilla, A. Performance Evaluation of a Commercial Positive Displacement Pump for Wind-Water Pumping. Renew. Energy 2007, 32, 1790–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Méndez, R.; Rasheed, A.; Peillón, M.; Perdigones, A.; Sánchez, R.; Tarquis, A.M.; García-Fernández, J.L. Wind Pumps for Irrigating Greenhouse Crops: Comparison in Different Socio-Economical Frameworks. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 128, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, R.; Wu, S.; Cai, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Peng, C.; Feng, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhong, X.; Li, Q. A Review on Performance Calculation and Design Methodologies for Horizontal-Axis Wind Turbine Blades. Energies 2025, 18, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serir, C.; Rekioua, D.; Mezzai, N.; Bacha, S. Supervisor Control and Optimization of Multi-Sources Pumping System with Battery Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 20974–20986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, E.; Kilic, O. Comparative Evaluation of Different Power Management Strategies of a Stand-Alone PV/Wind/PEMFC Hybrid Power System. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2012, 34, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, S.O.; Romero, J.A.; Romero, L.T.; Martínez, À.F.; Roger, X.S.; Qamar, M.A.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Gevorkov, L. Powering the Future: A Comprehensive Review of Battery Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Romero, L.T.; Martínez, À.F. Advances on Application of Modern Energy Storage Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME), Tenerife, Spain, 19–21 July 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, A.; Arias, P.; Gevorkov, L.; Trilla, L.; Obrador Rey, S.; Roger, X.S.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Filbà Martínez, À. Optimizing Performance of Hybrid Electrochemical Energy Storage Systems through Effective Control: A Comprehensive Review. Electronics 2024, 13, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, R.P.; Fajardo, A.; Lara-Borrero, J. Decentralized Renewable-Energy Desalination: Emerging Trends and Global Research Frontiers—A Comprehensive Bibliometric Review. Water 2025, 17, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Gonzalez, H.d.P.; Arias, P.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Trilla, L. Enabling Reliable Freshwater Supply: A Review of Fuel Cell and Battery Hybridization for Solar- and Wind-Powered Desalination. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja-Cayon, P.; Molina-Garcia, A.; Vera-Garcia, F. Mechanical vapor compression and renewable energy source integration into desalination process LIFE-Desirows case example. Therm. Sci. 2024, 28, 4395–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, Y.A. A Comprehensive Review of Reverse Osmosis Desalination: Technology, Water Sources, Membrane Processes, Fouling, and Cleaning. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouane, D.B.; Errouhi, A.A.; Redouane, M. Seawater Desalination: A Review of Technologies, Environmental Impacts, and Future Perspectives. Desalin. Water Treat. 2025, 324, 101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Talamantes, F.J.; Velázquez-Limón, N.; Aguilar-Jiménez, J.A.; Casares-De la Torre, C.A.; López-Zavala, R.; Ríos-Arriola, J.; Islas-Pereda, S. A Novel High Vacuum MSF/MED Hybrid Desalination System for Simultaneous Production of Water, Cooling and Electrical Power, Using Two Barometric Ejector Condensers. Processes 2024, 12, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabit, Q.; Nassour, A.; Nelles, M. Water Desalination Using the Once-through Multi-Stage Flash Concept: Design and Modeling. Materials 2022, 15, 6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Rassõlkin, A.; Vaimann, T. Comparative Simulation Study of Pump System Efficiency Driven by Induction and Synchronous Reluctance Motors. Energies 2022, 15, 4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yussif, N.; Sabry, O.H.; Abdel-Khalik, A.S.; Ahmed, S.; Mohamed, A.M. Enhanced Quadratic V/f-Based Induction Motor Control of Solar Water Pumping System. Energies 2021, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, B. Grid Interactive Solar PV-Based Water Pumping Using BLDC Motor Drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 5153–5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonandkar, S.; Selvaraj, R.; Chelliah, T.R. PV Powered Improved Quasi-Z-Source Inverter Fed Five Phase PMSM for Marine Propulsion Systems. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, *11*, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, H.; Singh, B. Multifunctional Grid Supported Solar Water Pumping System Utilizing Synchronous Reluctance Motor. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. B 2023, 104, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Vodovozov, V. Study of the centrifugal pump efficiency at throttling and speed control. In Proceedings of the 2016 15th Biennial Baltic Electronics Conference (BEC), Tallinn, Estonia, 3–5 October 2016; pp. 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gevorkov, L. Simulation and Experimental Study on Energy Management of Circulating Centrifugal Pumping Plants with Variable Speed Drives. Ph.D. Thesis, Tallinn University of Technology, Tallinn, Estonia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vodovozov, V.; Lehtla, T.; Bakman, I.; Raud, Z.; Gevorkov, L. Energy-efficient predictive control of centrifugal multi-pump stations. In Proceedings of the 2016 Electric Power Quality and Supply Reliability (PQ), Tallinn, Estonia, 29–31 August 2016; pp. 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Vodovozov, V.; Raud, Z.; Gevorkov, L. PLC-Based Pressure Control in Multi-Pump Applications. Electr. Control. Commun. Eng. 2015, 9, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Vodovozov, V.; Raud, Z.; Lehtla, T. PLC-Based Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulator of a Centrifugal Pump. In Proceedings of the IEEE 5th International Conference on Power Engineering, Energy and Electrical Drives (POWERENG), Latvia, Riga, 11–13 May 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gevorkov, L.; Bakman, I.; Vodovozov, V. Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation of Motor Drives for Pumping Applications. In Proceedings of the 2014 Electric Power Quality and Supply Reliability Conference (PQ2014), Rakvere, Estonia, 11–13 June 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gevorkov, L.; Rassolkin, A.; Kallaste, A.; Vodovozov, V. Simulink Based Model for Flow Control of a Centrifugal Pumping System. In Proceedings of the 2018 25th International Workshop on Electric Drives: Optimization in Control of Electric Drives (IWED), Moscow, Russia, 31 January–2 February 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bakman, I.; Gevorkov, L.; Vodovozov, V. Efficiency Control for Adjustment of Number of Working Pumps in Multi-pump System. In Proceedings of the 2015 9th International Conference on Compatibility and Power Electronics (CPE), Costa da Caparica, Portugal, 24–26 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gevorkov, L.; Rassõlkin, A.; Vaimann, T.; Kallaste, A. Simulation Study of Mixed Pressure and Flow Control Systems for Optimal Operation of Centrifugal Pumping Plants. Electr. Control Commun. Eng. 2018, 14, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, F.F.; Cornman, R.E.; Hartkopf, R.J. Centrifugal Pumps for Desalination. Desalination 1981, 38, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemdili, A.; Hellmann, D.-H. The Requirements to Successful Centrifugal Pump Application for Desalination and Power Plant Processes. Desalination 1999, 126, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wang, T.; Guo, Q.; Shu, P.; Gou, Q. Energy Loss Analysis of a Multi-Stage Centrifugal Pump Using in Pump Mode and Turbine Mode. Energy 2025, 334, 137784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Davies, P.A. Comparison of Configurations for High-Recovery Inland Desalination Systems. Water 2012, 4, 690–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syamsul Adha, R.; Nguyen, T.-T.; Lee, C.; Kim, I.S. High Recovery and Fouling Resistant Double Stage Seawater Reverse Osmosis: An Inter-Stage ERD Configuration Optimized with Internally-Staged Design (ISD). Desalination 2022, 521, 115401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Li, H. Demonstration of a Piston Type Integrated High Pressure Pump-Energy Recovery Device for Reverse Osmosis Desalination System. Desalination 2021, 507, 115033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhoska, K.; Spaho, E.; Sinani, U. Fabrication of Black Silicon Antireflection Coatings to Enhance Light Harvesting in Photovoltaics. Eng 2024, 5, 3358–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltawil, M.A.; Zhao, Z. MPPT Techniques for Photovoltaic Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 793–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, N.; Moubayed, N.; Outbib, R. General Review and Classification of Different MPPT Techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkaid, A.; Colak, I.; Isik, O. Photovoltaic Maximum Power Point Tracking under Fast Varying of Solar Radiation. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebei, N.; Hmidet, A.; Gammoudi, R.; Hasnaoui, O.; Salem, M. Implementation of Photovoltaic Water Pumping System with MPPT Controls. Front. Energy 2015, 9, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Luo, X.; Kiselychnyk, O.; Wang, J.; Shaheed, M.H. Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) Control of Pressure Retarded Osmosis (PRO) Salinity Power Plant: Development and Comparison of Different Techniques. Desalination 2016, 389, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Vodovozov, V. Mixed pressure control system for a centrifugal pump. In Proceedings of the 2017 11th IEEE International Conference on Compatibility, Power Electronics and Power Engineering (CPE-POWERENG), Cadiz, Spain, 4–6 April 2017; pp. 364–369. [Google Scholar]

- Gevorkov, L.; Vodovozov, V.; Lehtla, T.; Bakman, I. PLC-based flow rate control system for centrifugal pumps. In Proceedings of the 56th International Scientific Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering of Riga Technical University (RTUCON), Riga, Latvia, 14 October 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Muljadi, E. PV Water Pumping with a Peak-Power Tracker Using a Simple Six-Step Square-Wave Inverter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1997, 33, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouaiti, A.; Reddak, M.; Boutahiri, C.; Mesbahi, A.; Marhraoui Hsaini, A.; Bouazi, A. A Single Stage Photovoltaic Solar Pumping System Based on the Three Phase Multilevel Inverter. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2023, 13, 12145–12150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.N.; Mimouni, M.F.; Annabi, M. Vectorial Command of an Asynchronous Motor Supplied by a Photovoltaic Generator. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Yasmine Hammamet, Tunisia, 6–9 October 2002; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2002; Volume 5, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Dahiya, R. Speed Control of Solar Water Pumping with Indirect Vector Control Technique. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Sustainable Systems (ICISS), Palladam, India, 7–8 December 2018; pp. 1401–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Chergui, M.-I.; Bourahla, M. Application of the DTC Control in the Photovoltaic Pumping System. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 65, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammadi, S.; Hidouri, N.; Sbita, L. A DTC-PMSG-PMSM Drive Scheme for an Isolated Wind Turbine Water Pumping System. Int. J. Res. Rev. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2011, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, V.K.A.; Umashankar, S.; Paramasivam, S. Performance Evaluation of Fuzzy DTC Based PMSM for Pumping Applications. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrador Rey, S.; Canals Casals, L.; Gevorkov, L.; Cremades Oliver, L.; Trilla, L. Critical Review on the Sustainability of Electric Vehicles: Addressing Challenges without Interfering in Market Trends. Electronics 2024, 13, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaged, M.; Mahmood, A.; Alnema, Y.H.S. Design of an Integral Fuzzy Logic Controller for a Variable-Speed Wind Turbine Model. J. Robot. Control 2023, 4, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, I.J.; Ifaei, P.; Rshidi, J.; Yoo, C. Control Performance Evaluation of Reverse Osmosis Desalination System Based on Model Predictive Control and PID Controllers. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 26692–26699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.G.; Lee, Y.S.; Jeon, J.J.; Lee, S.; Yang, D.R.; Kim, I.S.; Kim, J.H. Artificial Neural Network Model for Optimizing Operation of a Seawater Reverse Osmosis Desalination Plant. Desalination 2009, 247, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrouf, O.; Betka, A.; Abdeddaim, S.; Ghamri, A. Artificial Neural Network Power Manager for Hybrid PV-Wind Desalination System. Math. Comput. Simul. 2020, 167, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnajdi, S.; Naderi Beni, A.; Roldan-Carvajal, M.; Aboderin, J.; Rao, A.K.; Warsinger, D.M. Salinity Gradient Energy Recovery with Batch Reverse Osmosis. Renew. Energy 2025, 246, 122801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, M.; Tolj, I.; Barbir, F. Review of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell-Powered Systems for Stationary Applications Using Renewable Energy Sources. Energies 2024, 17, 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | DC machines | AC machines |

|---|---|---|

| Control and Connection | Simple, can connect directly to DC sources, such as PV, batteries, without an inverter. | Requires a power electronic inverter for variable speed control and connection to DC sources. |

| Starting Performance | High initial starting torque, fast dynamic response to load changes. | Low starting torque relative to size, high inrush startup current. |

| Speed and Torque Profile | Excellent speed-torque characteristic for pumps, broad, linear speed control range. | Efficient over a wide speed range, but performance degrades significantly below ~30% of rated speed. |

| Construction and Maintenance | Contains brushes/commutator requiring periodic maintenance, vulnerable to failure in humid environments. | Robust, brushless construction (especially squirrel-cage IM) with minimal maintenance requirements. |

| Efficiency and Losses | Power losses and sparking at the commutator, cogging can occur at low speeds. | Generally higher full-load efficiency, copper losses dominate, efficiency drops sharply at light loads. |

| Cost and Complexity | Lower cost for simple controllers, higher cost for high-power units due to commutator complexity. | Lower motor unit cost, higher overall system cost due to the essential VFD. |

| Reliability and Environment | Risk of commutation failure, sparks can cause electromagnetic interference (EMI). | High reliability, operates well in harsh or humid environments. |

| Direct PV Compatibility | High. Naturally compatible with the DC output of PV arrays and batteries. | Low. Requires a DC-AC inverter (VFD) to interface with PV systems. |

| Control Strategy | Primary Objective | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| P&O | Track PV/Wind MPP via hill-climbing. | Simple, low-cost, minimal hardware requirements. |

| IC | Track MPP using derivative dP/dV=0. |

No oscillation at steady-state, more accurate than P&O under changing conditions. |

| CV/CC | Maintain a fixed voltage/current ratio of VOC/ISC | Extremely simple, reliable, no control loop, very low cost. |

| FLC | Adaptively track MPP under complex conditions. | Excellent performance under partial shading and fast transients; robust. |

| SC | Maintain constant flux for speed control. | Simple, reliable, low cost, wide industry adoption. |

| FOC | Decouple and control flux & torque. | Excellent dynamic performance, high efficiency, precise speed/torque control. |

| DTC | Direct control of stator flux and torque. | Very fast torque response, parameter robustness, simple structure. |

| RUL | Ensure basic power balance and protection. | Very simple, reliable, easy to implement and debug. |

| MPC | Optimize power flow using forecasts. | Near-optimal, minimizes operational cost, can plan ahead. |

| AI-Based | Intelligent, adaptive system coordination. | Handles non-linearity and uncertainty, can learn and adapt to patterns. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).