1. Introduction

The automated design of quantum experiments has evolved from a theoretical curiosity to a practical necessity. Quantum optics experiments—involving entangled photon sources, interferometric setups, and quantum state characterization—demand years of specialized training. An experimentalist must understand quantum mechanics, navigate hundreds of optical components, validate whether proposed setups produce intended quantum states, and iteratively refine designs through trial and error. This complexity has motivated decades of research into computational methods that can assist or even automate the design process.

Early pioneering work demonstrated that machine learning could discover experimental configurations beyond human intuition. MELVIN (2016-2018), developed by Krenn and colleagues at the University of Innsbruck, represented quantum experiments as weighted graphs and used automated search algorithms to discover novel experimental implementations [

1]. This breakthrough revealed a “hidden bridge” between graph theory and quantum optics, enabling the discovery of previously unknown experimental schemes for generating complex entangled states. The subsequent development of THESEUS further refined this graph-based approach, producing simpler experimental configurations through improved search heuristics [

2].

Building on these graph-theoretic foundations, PyTheus (2023) introduced a more general digital discovery framework [

3]. PyTheus automated the design of diverse quantum experiments, discovering over 100 experimental configurations for entangled state generation and measurement schemes. Its inverse-design algorithm proved particularly powerful for finding minimal experimental implementations of target quantum operations. Recent work has extended PyTheus through a modular interpreter that automates the analysis and visualization of PyTheus-optimized quantum networks [

4], handling complex connectivity patterns and facilitating the translation of abstract graph representations into implementable experimental setups.

Parallel to these quantum-specific developments, AdaQuantum (2019-2020) demonstrated that hybrid genetic algorithm and deep neural network approaches could optimize experimental parameters for quantum state engineering [

5]. AdaQuantum’s key innovation was using evolutionary algorithms to explore the vast design space while employing neural networks to predict experimental outcomes, significantly reducing the computational cost of optimization. This work showed that combining classical optimization with machine learning could accelerate the discovery of experimental protocols for producing non-classical quantum states of light.

More recently, the emergence of large language models (LLMs) has catalyzed a new generation of AI-driven scientific discovery systems. Coscientist (2023), developed by Boiko et al., demonstrated that GPT-4 could autonomously design, plan, and execute complex chemistry experiments [

6]. The system successfully navigated hardware documentation, controlled laboratory instruments, and optimized experimental parameters—showing that LLMs could handle the full experimental workflow from planning to execution. Systematic evaluations of LLM capabilities on quantum mechanics problem-solving have revealed both strengths and limitations: recent studies benchmarking 15 LLMs across quantum derivations, creative problems, and numerical computation found that while flagship models achieve high accuracy on theoretical tasks, numerical computation remains challenging even with tool augmentation [

7]. In quantum physics specifically, the k-agents framework (2024) introduced LLM-based agents for automating quantum computing laboratory experiments [

8]. K-agents organizes laboratory knowledge and coordinates multiple specialized agents to perform calibrations and characterizations of quantum processors, demonstrating successful single-qubit and two-qubit gate calibrations from natural language instructions.

The AI-Mandel system (2024), developed by Arlt, Gu, and Krenn, represents a particularly significant advance: an LLM agent that generates and implements original research ideas in quantum physics [

9]. AI-Mandel formulates hypotheses in natural language, automatically implements them using domain-specific tools like PyTheus, and has contributed to published research including the discovery of novel quantum teleportation variants. Similarly, Robin (2025), a multi-agent system by Ghareeb et al., demonstrated the first fully autonomous discovery and validation of a novel therapeutic candidate through iterative lab-in-the-loop experimentation [

10], showcasing the potential of multi-agent architectures for scientific discovery. The HoneyComb system (2024) further demonstrated flexible LLM-based agents specifically designed for materials science, leveraging high-quality domain knowledge bases and tool-calling capabilities [

11].

Despite these remarkable advances, a fundamental limitation persists across nearly all existing systems: they require non-intuitive interaction methods that create barriers to adoption. MELVIN and PyTheus demand understanding of graph-theoretic representations and topological operations. AdaQuantum requires expertise in genetic algorithm parameter tuning and fitness function design. Even recent LLM-based systems like k-agents require familiarity with specific experimental frameworks and structured command formats. This interaction complexity means that researchers must invest significant time learning the system’s interface before they can leverage its capabilities—ironically recreating a training barrier that automation was supposed to eliminate.

Consider a typical workflow with PyTheus: a researcher must manually construct graph representations of quantum experiments, understand the meaning of edges and vertices in the context of photon paths and transformations, configure search parameters for the optimization algorithm, interpret the output graphs, and then translate those abstract representations back into physical experimental configurations. While the system excels at discovering novel designs, each step requires specialized knowledge that most quantum physicists lack unless they specifically study the tool. Similarly, AdaQuantum demands understanding how to encode experimental constraints as fitness functions, tune genetic algorithm hyperparameters like mutation rates and population sizes, and interpret the evolutionary convergence patterns. These are valuable research tools for computational specialists, but they create friction for experimental physicists who simply want to design better experiments.

This gap between capability and usability defines the current state of automated experiment design. We have systems that can discover brilliant experimental configurations and even generate novel scientific ideas, but accessing those capabilities requires mastering complex intermediate representations, programming interfaces, or domain-specific languages. The promise of AI-assisted science—that domain experts could directly leverage computational intelligence without becoming computer scientists—remains largely unfulfilled.

Aṇubuddhi (Sanskrit: “atomic intelligence”) addresses this fundamental challenge through a natural language interface that eliminates intermediate representations entirely. A quantum physicist can simply describe what they want—“Design a Hong-Ou-Mandel interferometer to measure photon indistinguishability”—and receive a complete experimental design with component specifications, quantum state predictions, and validation results. No graphs to construct, no algorithm parameters to tune, no programming required. The system handles the full cognitive workflow: interpreting intent, retrieving relevant knowledge from past experiments, generating physically realistic designs, validating through quantum simulations, and learning from successes to improve future performance. By combining LLMs for reasoning and code generation with structured knowledge management through vector databases and physics simulation engines, Aṇubuddhi creates an architecture that mirrors how expert experimentalists think and work—but makes that expertise accessible through conversation.

The key innovation is not simply adding a natural language interface to existing tools, but implementing a complete learning architecture where validated experiments become reusable building blocks. When a user approves a Bell state generation setup, that entire assembly—pump laser, nonlinear crystal, filters, detectors—becomes a learned composite stored in a semantic vector database. Future requests for entangled photon sources can instantly retrieve and adapt this validated design rather than regenerating from scratch. This procedural learning mimics how research groups accumulate expertise: successful setups document in lab notebooks and inform new projects. Aṇubuddhi scales this process through semantic search over potentially hundreds of learned patterns, enabling instant retrieval of relevant past experiments while maintaining conversational flexibility for novel designs. The system has successfully designed 13 canonical quantum optics experiments spanning single-photon interference, quantum entanglement, quantum cryptography, and quantum state tomography—all from single-line natural language prompts such as “Design a Hong-Ou-Mandel interferometer” or “Design a BB84 QKD system,” with no additional specifications required.

This paper presents the architecture, implementation, and evaluation of Aṇubuddhi across diverse experimental scenarios, demonstrating that natural language interaction need not sacrifice technical rigor or design quality. We show that by carefully structuring the cognitive workflow—from conversational intent routing through knowledge-augmented generation to dual-mode validation with convergent self-refinement—AI systems can make sophisticated experiment design accessible to researchers without computational backgrounds. Our results suggest that the future of AI-assisted science lies not in creating more powerful but less accessible tools, but in building systems that meet researchers where they are: in natural language conversation about the science itself.

2. Methods

This section details the three-layered cognitive architecture underlying Aṇubuddhi, from conversational intent routing through knowledge-augmented generation to physics validation with convergent self-refinement. We describe each layer’s design rationale, implementation approach, and how the components integrate to transform conversational prompts into physically validated optical configurations. The validation methodology for evaluating system performance across 13 diverse quantum optics experiments is presented at the end.

2.1. Architectural Overview

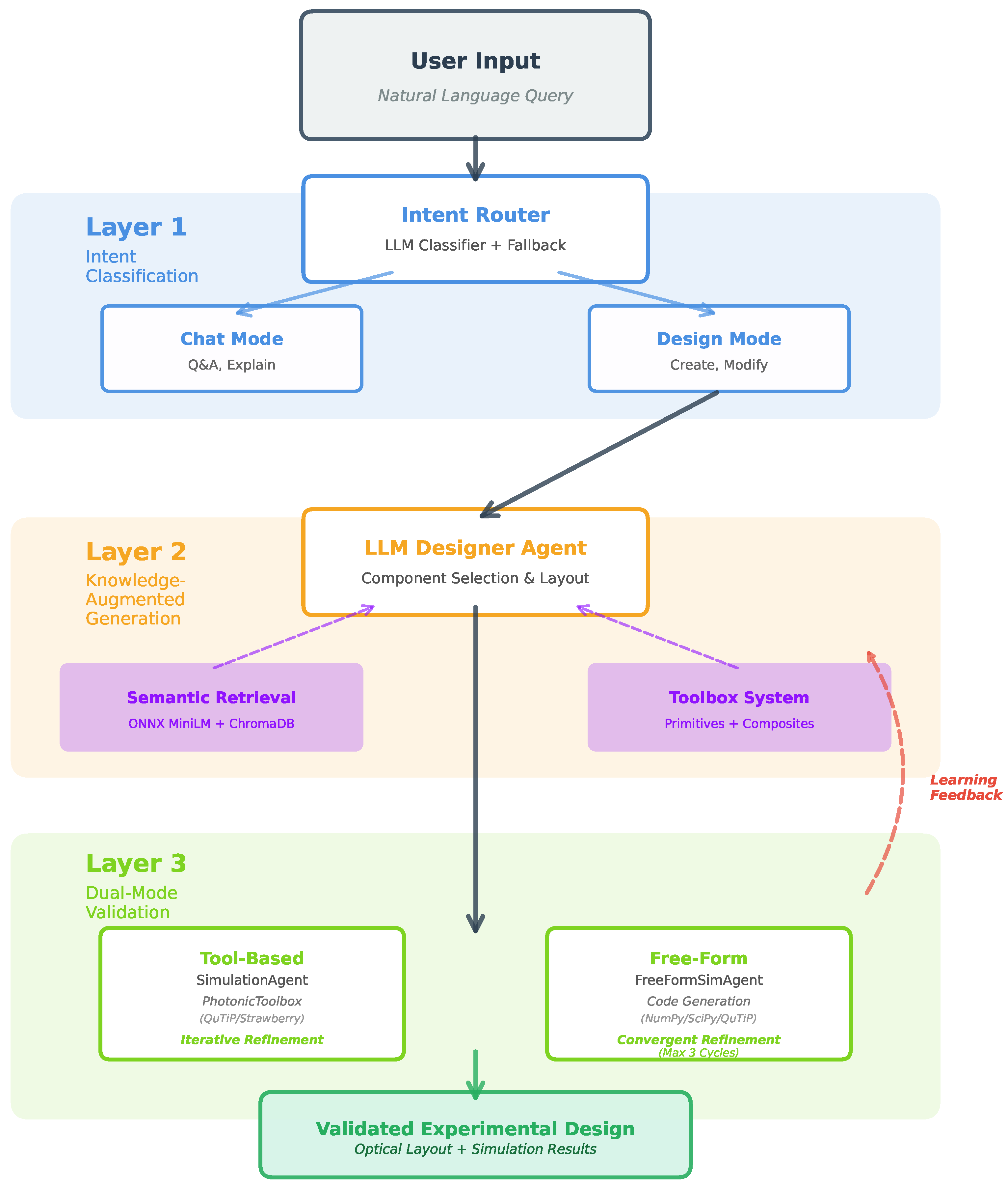

Aṇubuddhi implements a three-layer cognitive architecture (

Figure 1) that addresses the fundamental challenges of autonomous experiment design: conversational interaction, knowledge integration, and physics validation. Unlike graph-based systems that require users to construct explicit connectivity patterns [

2,

3], Aṇubuddhi operates entirely through natural language, translating conversational requests into validated experimental designs. The architecture emerged from systematic analysis of failure modes in preliminary implementations, leading to the hierarchical separation of concerns that enables robust operation across diverse experimental domains.

2.2. Layer 1: Conversational Intent Routing

Scientific collaboration requires fluid alternation between discussing concepts and modifying designs. During an experiment design session, users naturally interleave physics questions (“Why do indistinguishable photons bunch?”), practical inquiries (“Where can I buy a BBO crystal?”), and design modifications (“Add a delay stage to the second arm”). A naive system regenerating the entire experiment for every input would destroy conversational context; conversely, a system never modifying designs would be useless for iterative refinement.

Aṇubuddhi solves this through LLM-based intent classification [

14] implemented in

llm_designer.py. For each user message, the system constructs a routing prompt contrasting CHAT intent (information requests, explanations, discussions) against DESIGN intent (create, modify, add, remove commands). The LLM returns a single-word classification, enabling contextual interpretation beyond keyword matching: “Can I use a different laser?” routes to CHAT (asking about possibilities) while “Use a different laser” routes to DESIGN (commanding a change).

When LLM classification fails due to API errors or genuinely ambiguous phrasing, a keyword-based fallback router provides defensive coverage, defaulting to CHAT mode when uncertainty exists to prevent accidental design destruction. This dual-mode approach (primary LLM routing with fallback heuristics) ensures system robustness: the LLM handles semantic nuance while keyword matching prevents complete failure. The implementation preserves conversational flow—users can ask “Why indistinguishable photons?” and receive physics explanations without losing their carefully constructed optical table—while enabling precise control when modifications are explicitly requested.

2.3. Layer 2: Knowledge-Augmented Generation with Semantic Retrieval

The second layer addresses a fundamental tension in AI-assisted design: how to leverage accumulated knowledge without constraining creativity. A system with no memory regenerates experiments from first principles each time, wasting computation and producing inconsistent results. A system that rigidly reuses past designs cannot handle novel requirements. Aṇubuddhi implements retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) [

12] to balance these extremes, but adapts the approach for experimental design through a three-tier knowledge hierarchy and semantic retrieval over growing composite libraries.

2.3.1. Three-Tier Knowledge Hierarchy

The system maintains three distinct component types in toolbox_loader.py, each serving complementary roles in experiment construction:

Tier 1—Primitives (primitives.json): Over 50 immutable basic components form the foundation vocabulary. These include light sources (lasers, LEDs, single-photon sources), passive optics (mirrors, beam splitters, waveplates, lenses), nonlinear crystals (BBO, KTP, PPLN for frequency conversion and SPDC), detectors (photodiodes, APDs, SPADs, coincidence counters), and modulators (EOM, AOM, spatial light modulators). Organized by category (sources, detectors, crystals, passive_optics, measurement, modulation), this library never changes and provides the basic building blocks that combine to form any optical experiment.

Tier 2—Learned Composites (learned_composites.json): User-approved experimental assemblies transition from one-off implementations to reusable building blocks. When a user validates a complete SPDC photon pair source (pump laser at 405nm + BBO crystal with type-II phase matching + dual interference filters at 810nm + spatial mode coupling optics + SPADs with coincidence counting), the entire assembly saves as a named composite with complete specifications: component positions, beam paths, physics explanation, and approval timestamp. Subsequently, when anyone requests “entangled photon source” or “Bell state generator”, semantic search surfaces this validated pattern. This is the primary learning mechanism—successful multi-component assemblies transition from ephemeral experiments to institutional knowledge, implementing procedural learning where the system improves with use.

Tier 3—Custom Components (custom_components.json): Specialized equipment for non-standard experiments (rubidium vapor cells for EIT, optical frequency combs, atom chips, custom coincidence electronics) that LLMs define when needed. These track usage counts and last-used dates to prevent redundant redefinition. If an LLM defined a “87Rb vapor cell with temperature control and buffer gas” three experiments ago, subsequent requests can reference that definition rather than generating it anew, reducing token usage and ensuring consistency.

2.3.2. Semantic Retrieval Over Learned Patterns

As the learned composite library grows to hundreds of entries, including everything in the generation prompt becomes infeasible—modern LLMs have token limits, and overwhelming context degrades reasoning quality. The solution is embedding-based semantic search [

12] implemented in

embedding_retriever.py.

When a user requests an experiment (e.g., “Design Hong-Ou-Mandel interference”), Aṇubuddhi embeds this query using ONNX Runtime’s implementation of MiniLM-L6-V2 sentence transformer (22M parameters, 384-dimensional output vectors). This embedding vector is compared against all indexed composites in ChromaDB [

15] using cosine similarity. The retrieval includes intelligent deduplication: when multiple versions of the same experiment exist (e.g., “Mach-Zehnder v1” from initial design, “Mach-Zehnder v2” from user refinement, “Mach-Zehnder v3” from different parameter choices), only the most recent version from each name group is retained. The top-5 most semantically similar composites appear in the generation context, providing the LLM with concrete examples of validated designs addressing similar physics.

Given these retrieved patterns, the LLM makes a critical decision: does an existing composite closely match the current request (>80% similarity in description and components)? If yes, the system returns metadata indicating an existing match, and the UI presents three options to the user: (1) Use This—deploy the validated design exactly, ensuring consistency with past work; (2) Auto-Improve—let the LLM adapt the composite to address specific user requirements while preserving the validated core structure; or (3) Generate New—ignore the match and create a fresh design, useful when users want to explore alternative approaches. If no close match exists (<80% similarity), the system generates a novel design but uses retrieved composites as contextual examples demonstrating component usage patterns, typical configurations, and design strategies that have previously succeeded.

This implements smart reuse that balances efficiency with flexibility: exact matches leverage validated designs for consistency and speed, while partial matches provide inspiration without constraining the LLM’s ability to address novel requirements. The approach mimics how experimentalists work in practice—checking lab notebooks for similar past setups before designing from scratch, adapting existing protocols when appropriate, but creating new configurations when needed for genuinely novel experiments.

2.4. Layer 3: Dual-Mode Physics Validation with Convergent Self-Refinement

Generated optical layouts must be physically correct before deployment. A design with incorrect polarization alignment, wrong detector placement, or incompatible component specifications wastes experimental resources and user time. Aṇubuddhi validates every generated design through quantum simulation, but faces a significant technical challenge: quantum optics experiments span multiple mathematical formalisms. Interferometry uses Fock state representations, Hong-Ou-Mandel interference requires temporal wavepacket propagation, squeezed light demands quadrature operator calculations, and electromagnetically induced transparency necessitates Lindblad master equations. No single simulation framework adequately handles all domains.

2.4.1. Dual-Mode Validation Strategy

The system implements two complementary validation modes, allowing users to run experiments in either approach to empirically compare results:

Mode 1—PhotonicToolbox (Discrete Photonics) provides high-reliability validation for standard experiments. Built on Strawberry Fields [

16] and QuTiP [

17] backends, this mode offers type-safe operations: beam splitters act on Fock states with specified transmittivity, waveplates rotate polarization angles, photodetectors measure photon number probabilities. The structured API prevents nonsensical operations (e.g., applying beam splitter to atomic state) and guarantees physically valid transformations. This works excellently for Mach-Zehnder interferometry, Bell state generation via SPDC, basic polarization experiments, and other systems naturally described by discrete quantum states with photon-number-based observables.

However, PhotonicToolbox cannot model temporal dynamics (photon arrival time distributions, distinguishability from pulse timing), continuous-variable systems (quadrature measurements, Wigner functions, phase-space distributions), or atomic physics (multilevel coherences, spontaneous emission, optical pumping). The Fock state formalism is fundamentally inadequate for these phenomena—attempting to model Hong-Ou-Mandel interference with static photon number states misses the essential physics of temporal overlap.

Mode 2—Free-Form Simulation (Flexible Physics Modeling) addresses this limitation by giving the LLM complete freedom to write simulation code from scratch, implemented in freeform_simulation_agent.py. For each experiment, the agent chooses the appropriate formalism: temporal wavepacket propagation with Gaussian mode overlap integrals for Hong-Ou-Mandel interference, quadrature operator calculations and homodyne detection statistics for squeezed light, Lindblad master equations for electromagnetically induced transparency. The agent has full access to NumPy (array operations, linear algebra, FFTs), SciPy (special functions, numerical integration, optimization), QuTiP (quantum operators, time evolution, master equations), and Matplotlib (visualization). This flexibility enables accurate modeling of diverse quantum systems but introduces a critical reliability challenge: how to ensure auto-generated code actually simulates the intended experiment rather than superficially similar physics?

2.4.2. Convergent Self-Refinement with Multi-Gate Validation

To address code generation reliability, the free-form mode implements a six-stage validation pipeline inspired by self-refinement [

13] and self-debugging [

18] approaches, but adapted for physics simulation with explicit alignment checking. The process iterates up to three times, converging toward simulations that accurately model designed experiments:

Stage 1—Physics Classification: The LLM categorizes each experiment into one of four physics domains (discrete photonic, temporal, continuous variable, atomic) based on experiment description and key components. This guides formalism selection: “HOM interference with photon distinguishability” → temporal domain → wavepacket propagation code; “squeezed light homodyne detection” → continuous variable → quadrature operators; “multilevel atom Rabi oscillations” → atomic → master equation. The classification prompt explicitly asks what physical quantities determine the experimental outcome, focusing the LLM on relevant observables rather than superficial experiment names.

Stage 2—Guided Code Generation: Initial simulation code generation uses a comprehensive 4800-character prompt specifying available libraries and their typical usage, realistic parameter ranges (wavelengths 200–2000nm, squeezing <15dB, detector efficiencies 0.1–0.95), physics-specific guidance (e.g., for temporal domain: “Model photons as Gaussian wavepackets with temporal width, compute overlap integral at beam splitter following the Dirac formalism”), and common pitfalls to avoid (wrong Bell state phase conventions, using static Fock states for inherently temporal phenomena, incorrect SPDC phase matching conditions, unrealistic parameter values like 68dB squeezing). The prompt incorporates chain-of-thought reasoning [

19] by explicitly requesting the LLM to explain its modeling choices before generating code, improving physical accuracy.

Stage 3—Pre-Execution Review: Before running any code, an LLM-based review evaluates whether it will actually model the intended experiment. This pre-execution check answers four critical questions: (1) Does the chosen formalism match the experiment type? (temporal wavepackets for HOM, not static Fock states); (2) Are key optical components present in simulation? (beam splitter at correct position, detectors at appropriate outputs); (3) Are parameters physically realistic? (810nm wavelength for SPDC, not 10nm; squeezing 3–10dB, not 68dB); (4) Is the mathematical approach fundamentally sound? (proper normalization, unitary evolution, probability conservation). The LLM returns a structured response {“approved”: bool, “confidence”: float, “concerns”: [list]}. Code failing this review proceeds directly to refinement without wasting compute on execution of obviously flawed code. This pre-check prevents the common failure mode where syntactically correct but physically nonsensical code executes successfully, producing meaningless results.

Stage 4—Isolated Execution: Approved code runs in an isolated subprocess with 30-second timeout, stdout/stderr capture, and automatic figure extraction. The subprocess isolation prevents crashes from affecting the main system (physics simulations can have numerical instabilities, divergences, or unexpected errors), while timeout prevents infinite loops or excessively slow convergence. The execution environment overrides plt.show() to automatically save all matplotlib figures to temporary storage, capturing visualization outputs that would otherwise be lost in non-interactive execution. All generated figures extract as base64-encoded PNG data for display in the web interface.

Stage 5—Design-Simulation Alignment Check: After successful execution, the system performs the most critical verification: Did the simulation actually model what the designer intended, or did it simulate different physics that happened to run without errors? This catches “arbitrary jazz”—code that executes successfully but simulates the wrong experiment (e.g., generating code that simulates simple beam splitter interference when the design specified Hong-Ou-Mandel two-photon quantum interference). An LLM analyzes the experiment specification, generated code, and execution outputs, then scores alignment on a 0–10 scale based on four criteria: (a) code models the exact intended physics, not just superficially similar phenomena; (b) all key optical components appear in simulation and function as designed; (c) parameters match design specifications; (d) calculated outputs match claimed observables (if design claims to measure entanglement, code must calculate entanglement witness, CHSH inequality violation, or concurrence; photon number measurements alone are insufficient). The LLM also identifies missing_from_code and wrong_in_code elements, providing actionable feedback for refinement.

Stage 6—Targeted Refinement: If alignment scores below 6/10 or execution fails, the system generates an improved version. Crucially, refinement is targeted, not regenerative—a key lesson from preliminary implementations where regeneration often discarded working code. The refinement prompt includes: current code, specific failure feedback (“Missing: temporal wavepacket model for distinguishability; Bug: division by zero at line 47 when calculating overlap”), and explicit instruction to “fix only what’s broken while preserving correct elements”. This prevents the common LLM failure mode of destroying working code during regeneration. The process iterates up to three times. If refinement degrades quality (alignment score decreases), the system reverts to the best-working version from previous iterations, implementing a form of best-first search that preserves progress.

The multi-gate validation pipeline enables convergent refinement toward simulations that accurately model designed experiments. The pre-execution review prevents running nonsensical code (saving computational resources), isolated execution ensures system stability, alignment checking catches subtle semantic errors, and targeted refinement improves specific issues without wholesale regeneration. This architecture emerged from analyzing failure modes across 50+ preliminary experiments, where we observed that (1) LLMs sometimes generate syntactically correct but physically wrong code, (2) untargeted refinement often breaks working code, and (3) alignment between design intent and simulation implementation is distinct from code execution success.

2.5. Procedural Learning Through Approved Designs

When users approve a validated design (optical layout passes visual inspection, simulation demonstrates expected physics, user confirms the setup addresses their experimental goal), the system automatically saves it to the learned composites library. The saved entry includes complete specifications: experiment name and description, all optical components with 2D spatial coordinates, beam propagation paths connecting components (represented as adjacency lists), physics explanation describing the quantum phenomena, expected experimental outcomes, and approval timestamp. This entry immediately indexes in ChromaDB through embedding_retriever.py, making it available for semantic search in subsequent design sessions from any user.

This implements procedural learning—successful experimental assemblies transition from ephemeral one-off implementations to permanent institutional knowledge. The learning is implicit and automatic: users simply approve designs they’re satisfied with, and those designs become available for future reuse without manual curation or knowledge engineering. The system improves with use through accumulation: the first Hong-Ou-Mandel design requires full generation from physics first principles (defining quantum states, implementing beam splitter operations, calculating temporal overlap integrals), while the tenth request can reference nine validated precedents providing concrete examples of successful configurations, typical parameter choices, and common implementation patterns.

This procedural learning mimics how experimental research groups actually accumulate expertise. Lab notebooks document successful setups (“Use 810nm pump for BBO SPDC with type-II phase matching”), institutional knowledge includes “tricks that work” (“Place interference filters at 45° to beam path for better out-of-band rejection”), and new graduate students learn by studying past experiments before attempting novel work. Aṇubuddhi scales this process through perfect recall (never forgets any validated design) and instant semantic retrieval (finds relevant past experiments in milliseconds via embedding similarity, compared to hours of manual literature search).

2.6. Implementation and Availability

The system is implemented in Python 3.9+ using Streamlit 1.28+ for the conversational web interface, QuTiP 4.7+ [

17] and Strawberry Fields 0.23+ [

16] for quantum state manipulation and photonic circuit simulation, ChromaDB 0.5+ with ONNX Runtime for semantic retrieval (MiniLM-L6-V2 embeddings [

20], 384-dimensional vectors, cosine similarity), and supports multiple LLM backends (OpenAI GPT-4, Anthropic Claude 3.5, local models via Ollama) through a unified

SimpleLLM client interface enabling backend swapping without code changes. The architecture requires only consumer-grade computing hardware (16GB RAM recommended, 8GB minimum); no quantum hardware, GPU acceleration, or specialized infrastructure needed for operation.

The implementation follows true agentic architecture where the UI (app.py) never directly invokes LLMs—all calls route through specialized agents (LLMDesigner, FreeFormSimulationAgent) implementing the three-layer cognitive workflow. This modularity enables independent improvement: replacing the embedding model requires changing only EmbeddingRetriever, improving validation logic affects only simulation agents, adding new LLM backends requires minimal interface code. The OpticalSetup dataclass serves as the data contract between layers, carrying complete experiment specifications (title, description, components with spatial positions, beam paths, physics explanations, simulation results) through the pipeline from generation to validation to user presentation.

Complete source code, including all agent implementations, the three-tier toolbox system, both simulation engines (PhotonicToolbox and free-form), semantic retrieval infrastructure, and 13 complete experimental packages (designs, simulation code, analysis reports, optical diagrams at 300 DPI), is publicly available under MIT license at

https://github.com/rithvik1122/Anubuddhi [

21]. The repository includes installation scripts, configuration templates, and comprehensive documentation enabling researchers to deploy the system, extend it with new components or simulation methods, or adapt the architecture for other experimental domains beyond quantum optics.

3. Results

We evaluated Aṇubuddhi on 13 quantum optics experiments spanning three complexity tiers, from foundational interferometry to cutting-edge quantum technologies. For each experiment, Aṇubuddhi autonomously generated both an optical table design and simulation code to validate that design. This integrated design-simulation workflow provides users with quantitative confidence in experimental feasibility: alignment scores quantify how accurately the simulation models the intended design (0–10 scale), physics validation identifies implementation errors versus conceptual flaws, and downloadable metrics enable informed decision-making before committing to physical implementation. The system supports two simulation approaches—QuTiP (constrained to Fock-state formalism) and FreeSim (unrestricted access to Python libraries including NumPy, SciPy, and QuTiP)—with users able to run experiments in both modes. We report results from the mode that empirically achieved higher design-simulation correspondence for each experiment.

Note: Complete experimental packages (design specifications, simulation code, analysis reports, figures, and optical diagrams) for all experiments are publicly available in the project repository:

https://github.com/rithvik1122/Anubuddhi. Each experiment subsection includes a direct link to its specific folder.

Optical Table Diagrams: The optical layouts shown in this section are generated from Aṇubuddhi-specified component positions and beam paths. While component selection and beam connectivity are correct, geometric angles may not be optically precise. These diagrams are schematic representations; the simulation code independently validates physical correctness.

3.1. Overview of Experimental Coverage

The 13 experiments are strategically distributed across three hierarchical complexity tiers to comprehensively evaluate Aṇubuddhi’s capabilities across the full spectrum of quantum optics research. This tiered structure progresses from pedagogical experiments with well-established theoretical frameworks through sophisticated quantum information protocols to specialized technologies requiring multi-physics modeling, providing a rigorous testbed that mirrors the diversity of real-world quantum optics laboratories.

Tier 1 – Fundamental Quantum Optics (5 experiments): Canonical experiments from standard quantum optics curricula—Hong-Ou-Mandel two-photon interference [

22] Michelson interferometry [

23],, SPDC-based Bell state generation [

24,

25], Mach-Zehnder [

26,

27] and delayed-choice quantum erasure [

28]. These establish baseline performance on well-understood physics where analytical solutions exist, testing whether Aṇubuddhi correctly implements foundational quantum mechanics (superposition, interference, entanglement) and proper component parameter selection.

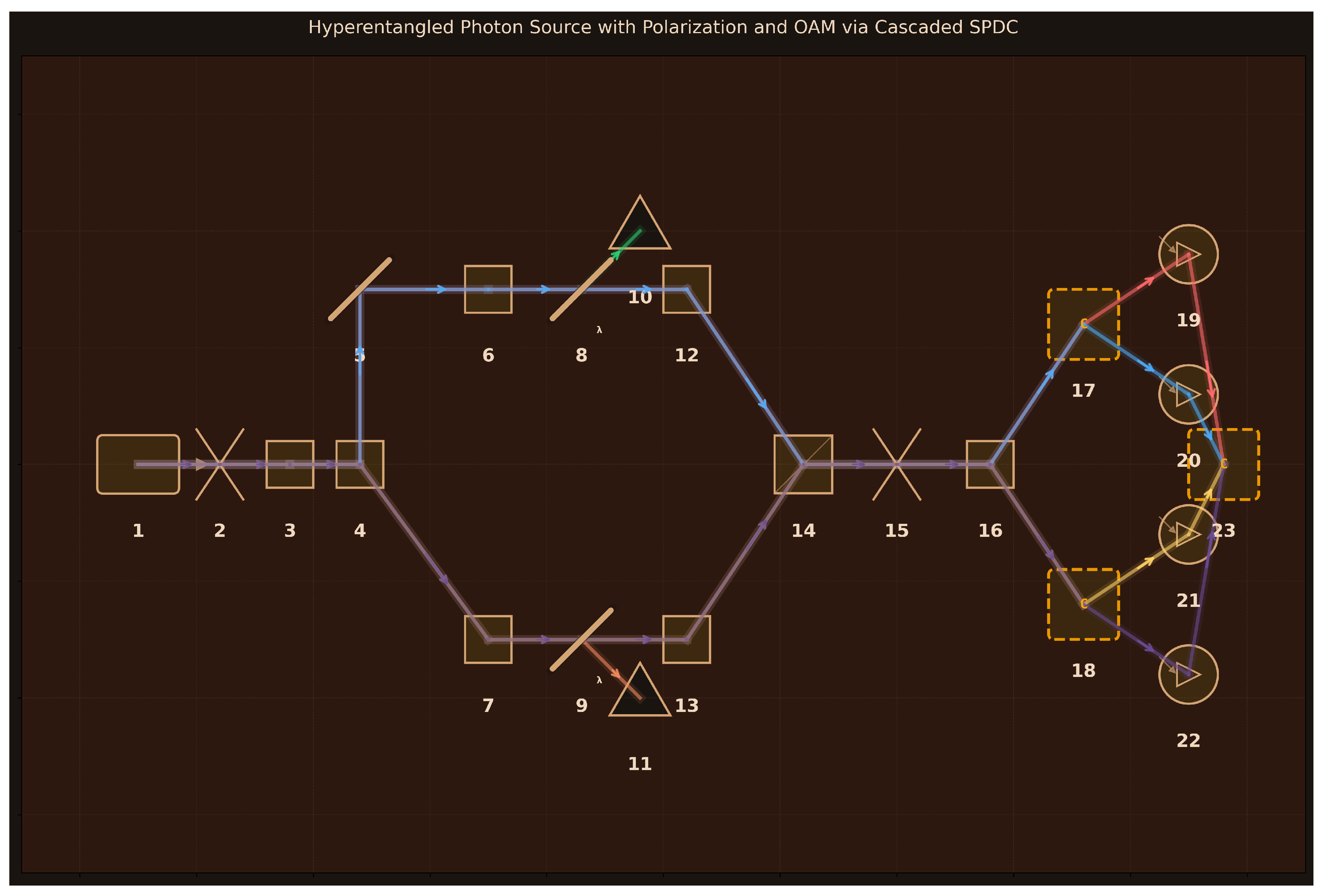

Tier 2 – Quantum Information Protocols (5 experiments): Implementations of established quantum information protocols with increased experimental complexity—BB84 quantum key distribution [

29], Franson interferometry for time-bin entanglement [

30], GHZ state generation [

31], discrete quantum teleportation [

32], and hyperentanglement [

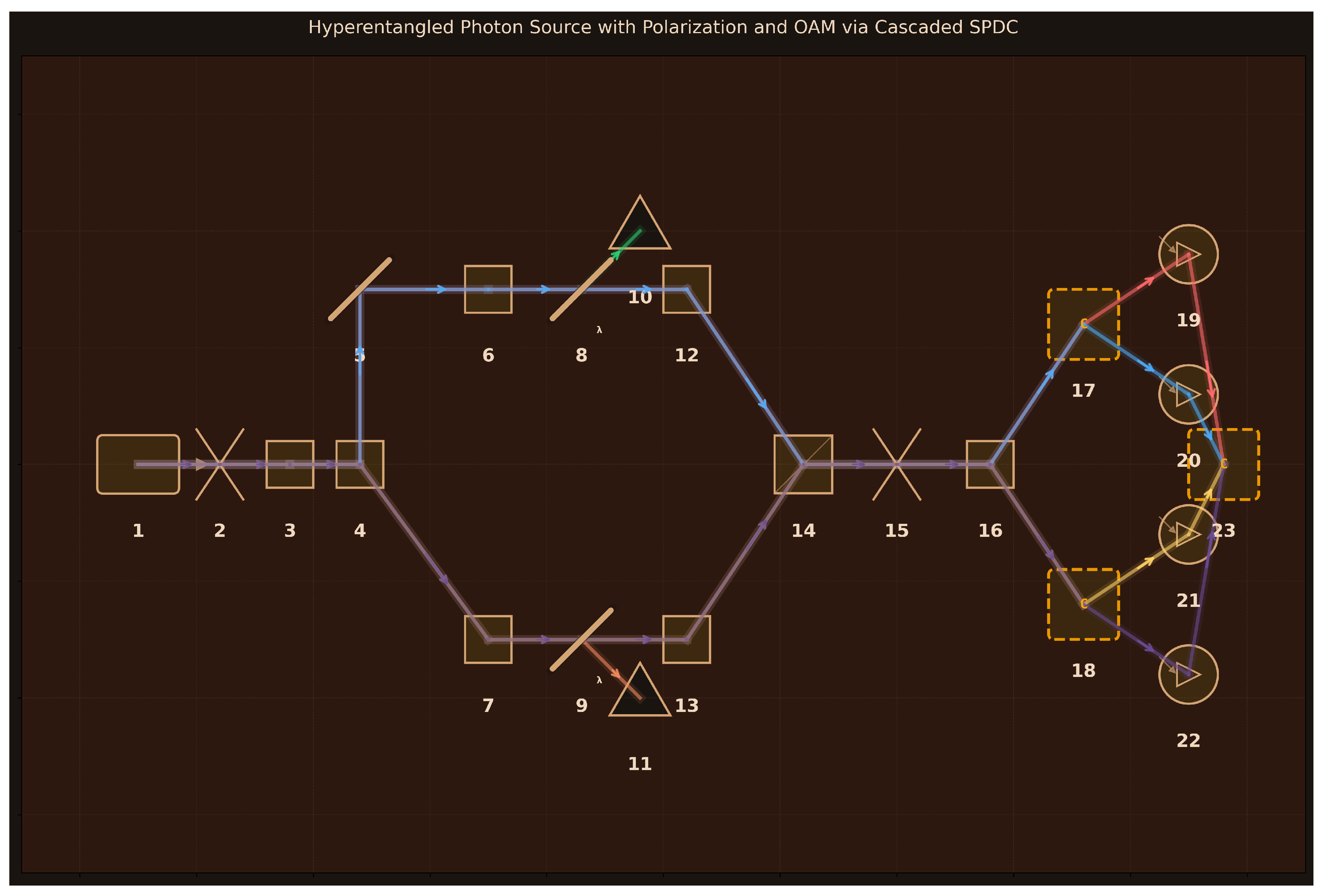

33]. These experiments demand sophisticated understanding of quantum communication primitives, non-classical light sources, and multi-photon entanglement structures that extend beyond textbook treatments, requiring careful component integration and parameter optimization.

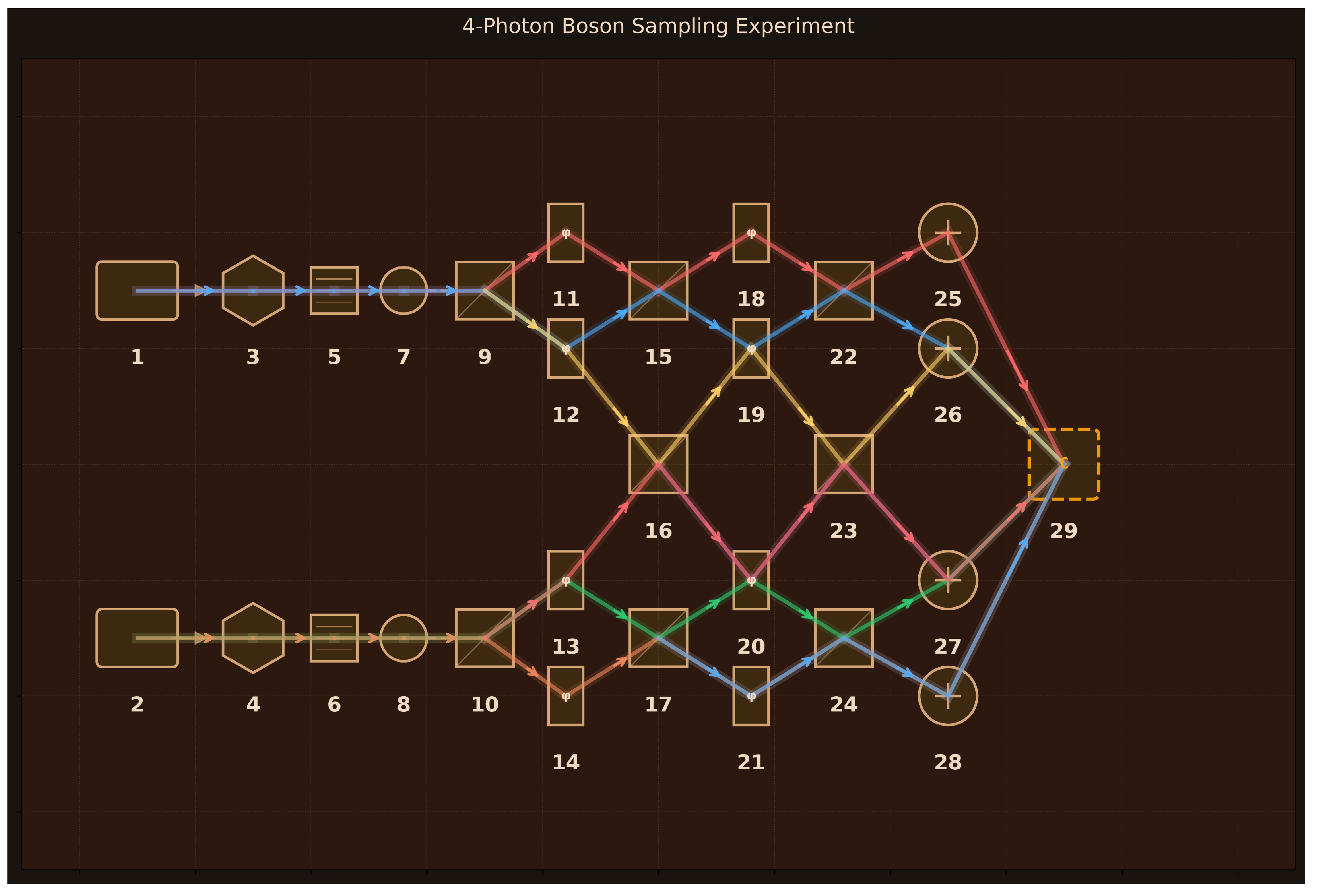

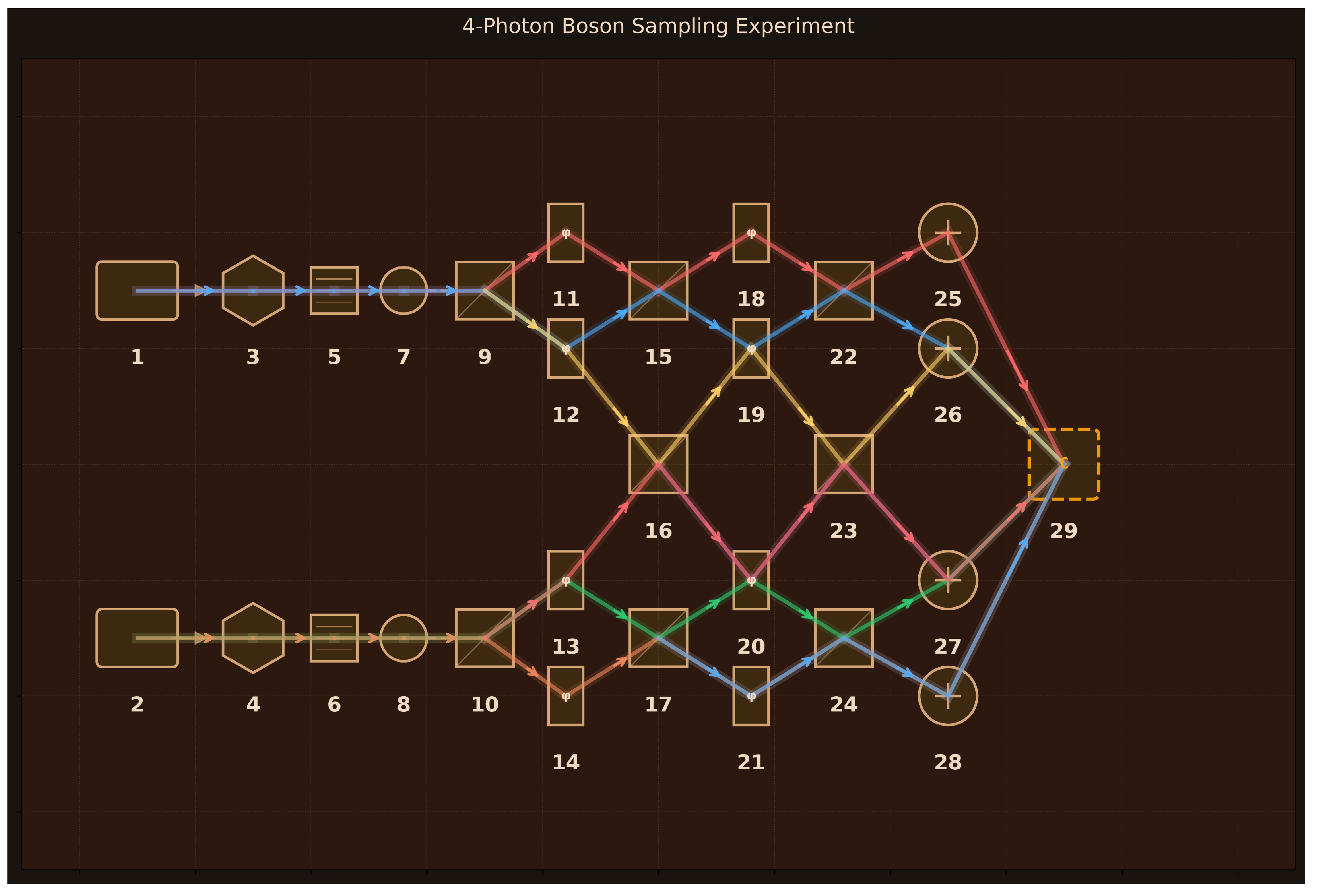

Tier 3 – Advanced Technologies (3 experiments): Specialized experiments exploring cutting-edge areas of quantum optics—4-photon boson sampling [

34,

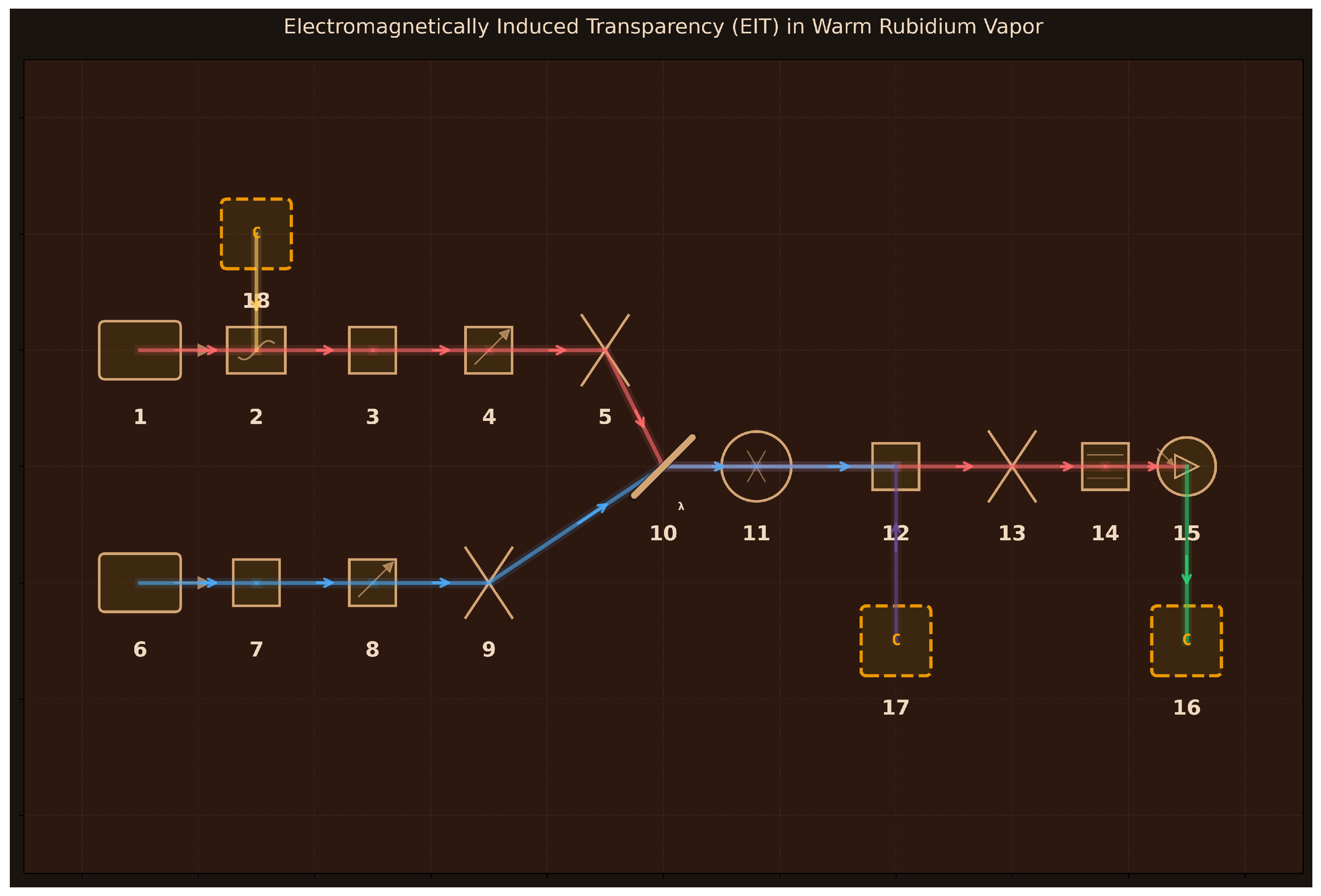

35] (quantum computational advantage), electromagnetically induced transparency in warm atomic vapor [

36,

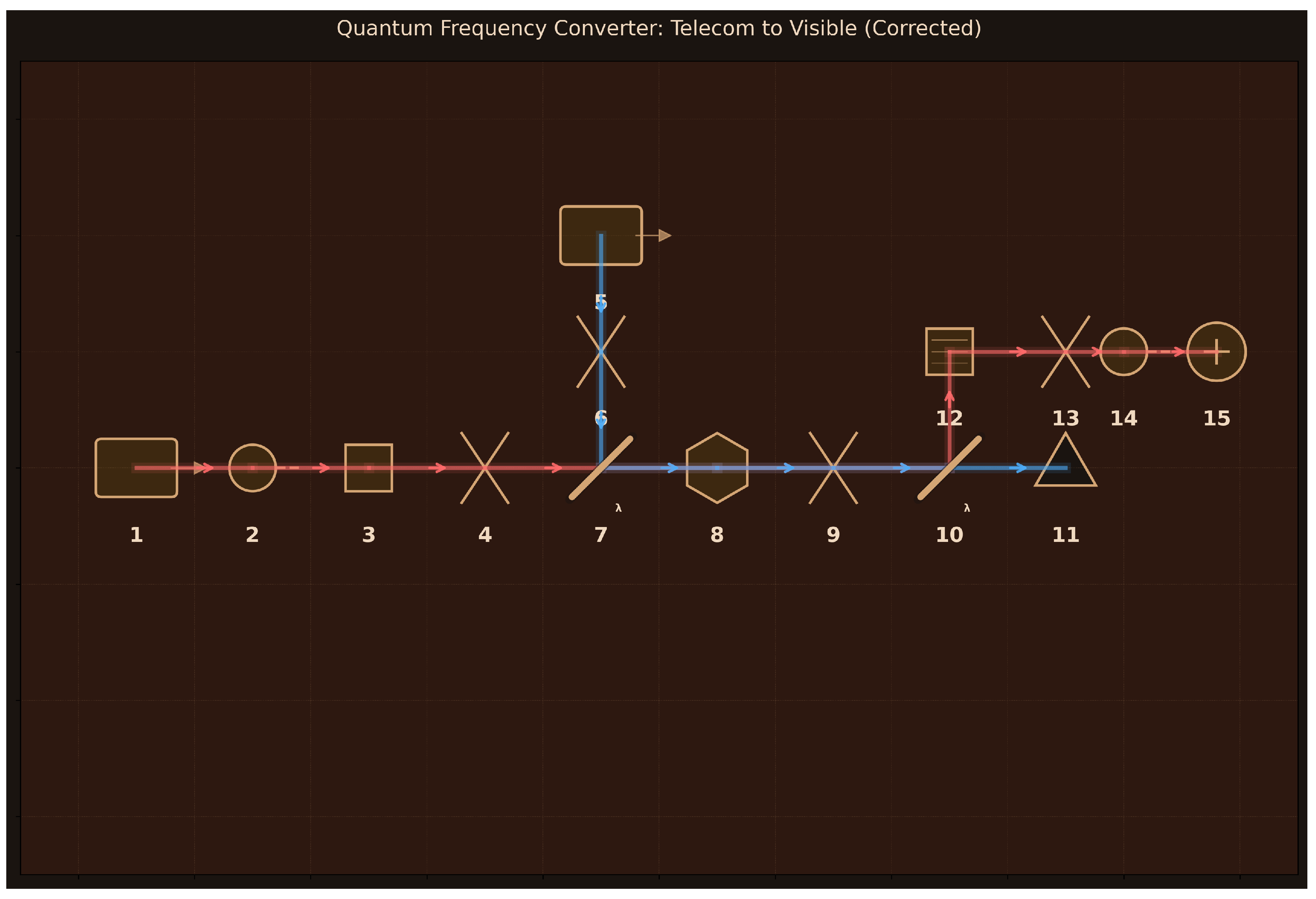

37] (light-matter interaction), and quantum frequency conversion between telecom and visible wavelengths [

38,

39]. These require modeling physics beyond standard quantum optics frameworks: many-body interference permanents, atomic coherences in thermal ensembles, and nonlinear frequency mixing with quasi-phase matching.

This hierarchical test suite ensures evaluation across key dimensions: quantum state complexity (single photons to multi-photon entangled states), physical regimes (pure quantum optics to atom-light interfaces), and technological maturity (established techniques to specialized applications). Success across all tiers demonstrates that Aṇubuddhi can serve diverse user needs, from educational demonstrations to research prototyping.

3.2. Performance Summary by Tier

Across all 13 experiments, the system achieved varied performance levels reflecting the inherent complexity of each tier. Each experiment was run in both simulation modes, with results reported from the mode achieving higher alignment scores and physics validation quality. Empirically, FreeSim performed better for 11/13 experiments while QuTiP performed better for 2/13. FreeSim’s unrestricted access to multiple Python libraries (NumPy, SciPy, QuTiP, etc.) provided greater flexibility in handling diverse quantum systems compared to QuTiP’s constraint to Fock-state formalism.

3.3. Tier 1: Fundamental Quantum Optics

This tier comprises five foundational experiments that establish the core principles of quantum optics. These experiments test the system’s ability to handle standard quantum phenomena with well-established theoretical frameworks and analytical solutions.

3.3.1. Hong-Ou-Mandel Interference

Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) interference is a fundamental quantum effect where indistinguishable photons arriving simultaneously at a beam splitter exhibit bosonic bunching, creating a characteristic suppression of coincidence counts that has no classical analog.

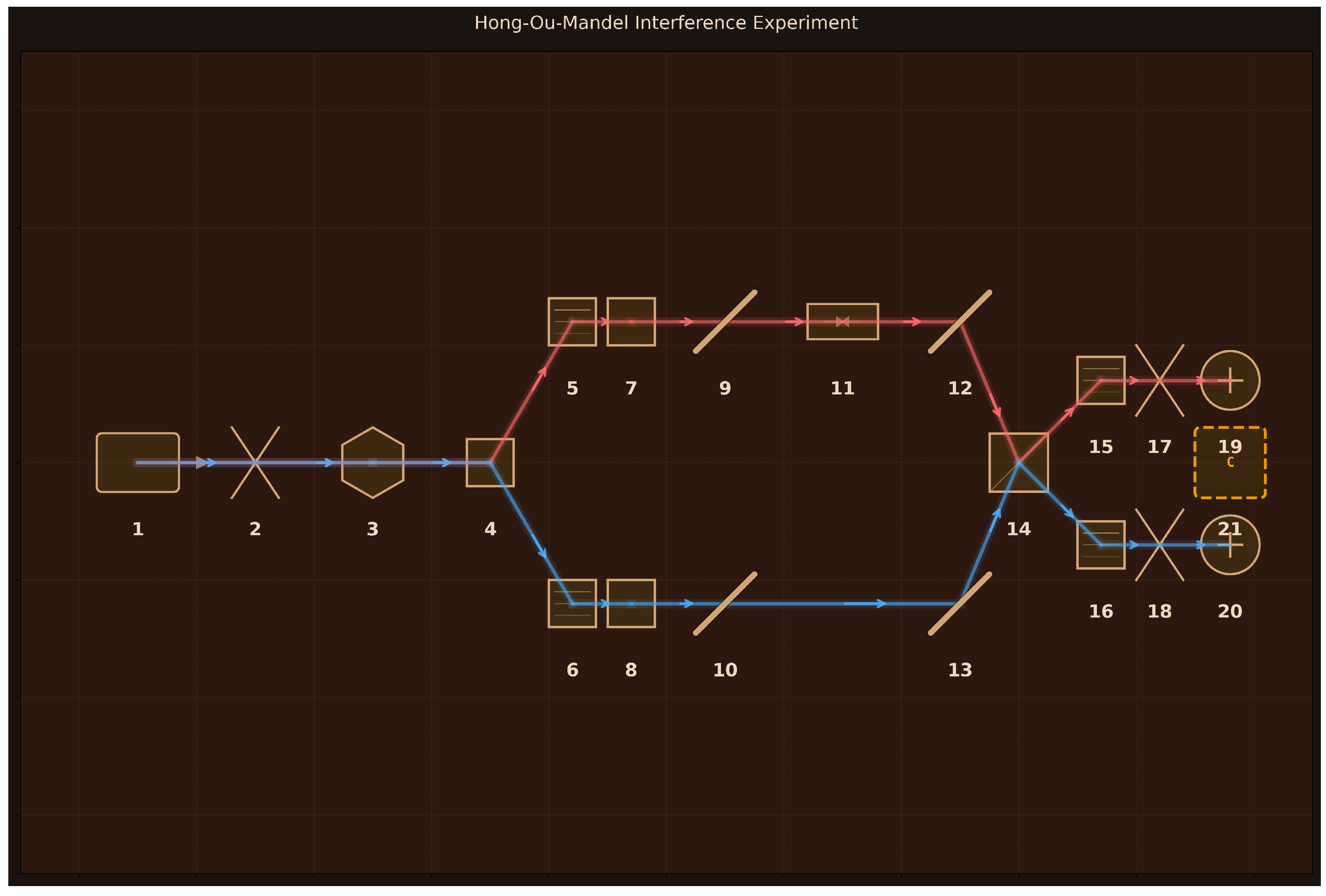

Design: 21 components arranged for two-photon quantum interference (

Figure 2):

(1) Pump Laser (405 nm, 100 mW);

(2) Focusing Lens (50 mm focal length);

(3) BBO Crystal (Type-II SPDC, 2 mm length);

(4) PBS Separator (polarizing cube);

(5–6) Pump Block Filters (405 nm, OD6);

(7–8) HWP 1-2 (zero-order, 810 nm, polarization alignment);

(9–10, 12–13) Mirrors 1-4 (beam routing);

(11) Delay Stage (100 mm range, 0.1

m resolution);

(14) 50:50 BS (non-polarizing cube);

(15–16) IF Filters 1-2 (810 nm, 3 nm bandwidth);

(17–18) Coupling Lenses 1-2 (11 mm focal length);

(19–20) SPAD 1-2 (65% efficiency, 25 Hz dark counts, 50 ps timing resolution);

(21) Coincidence Counter (1 ns window). The Type-II SPDC generates orthogonally polarized photon pairs that are spatially separated by the PBS, then rendered indistinguishable via HWPs before interfering at the central beam splitter.

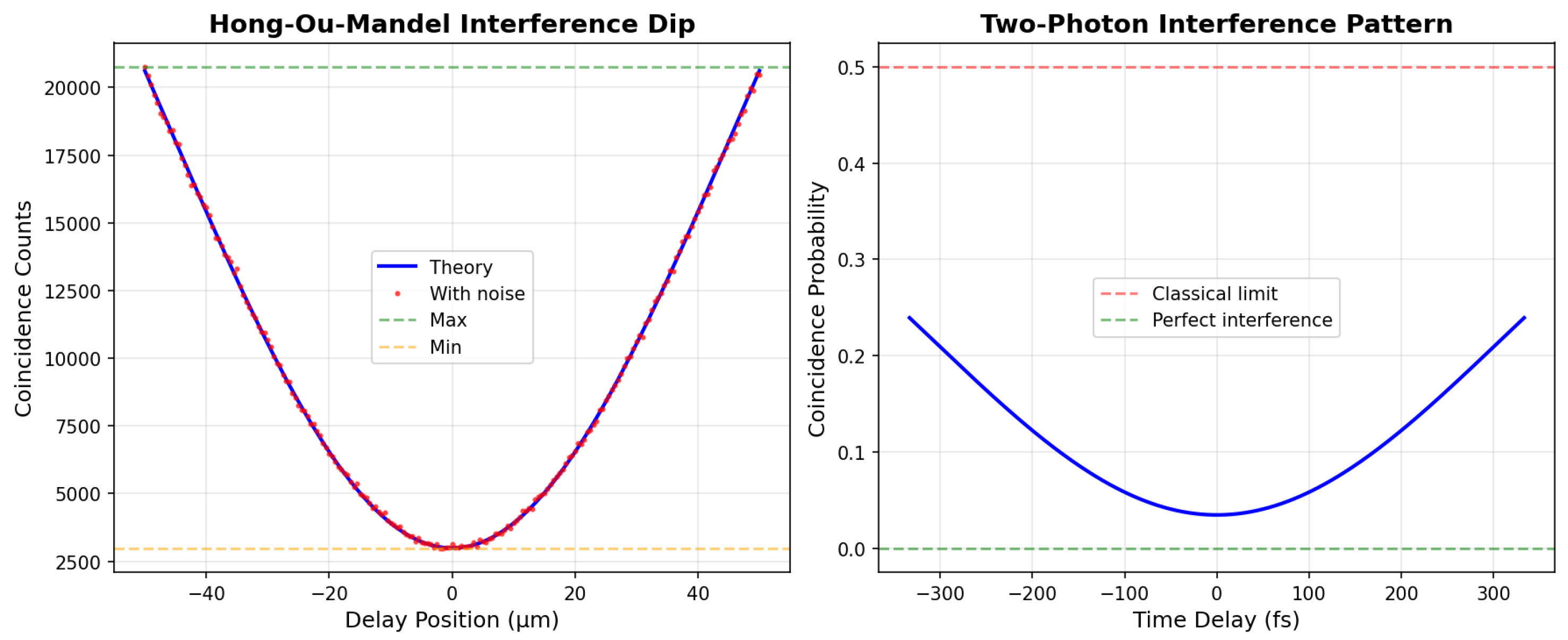

Simulation Method: FreeSim (generated code free to use multiple Python libraries like NumPy, SciPy, QuTiP etc. with the goal of accurately modeling and simulating the design).

Performance Metrics:

Key Results:

Correctly implements two-photon quantum interference with proper wavepacket overlap integral

Figure 3 shows the characteristic HOM dip: coincidences drop from maximum (20,761 counts) to minimum (2,983 counts) at zero delay

Achieves visibility of 0.75 exceeding classical limit (0.5), unambiguously demonstrating quantum interference

HOM dip FWHM of 437 fs properly correlates with 729 fs photon coherence time determined by 3 nm spectral filtering

Includes realistic experimental imperfections: 65% detector efficiency, 25 Hz dark counts, 95% mode matching, 2% residual distinguishability

Excellent signal quality: SNR = 123, true/accidental coincidence ratio = 4,910:1

Bunching factor of 0.29 correctly demonstrates bosonic statistics (0 = perfect bunching, 1 = classical limit)

Limitations: Spatial mode overlap assumed perfect beyond the 95% visibility parameter—no explicit Gaussian beam overlap calculation at beam splitter. Gaussian wavepacket model may not capture full spectral structure from SPDC phase matching bandwidth. Measured visibility (0.75) lower than expected (0.93) primarily due to Poisson noise on finite count statistics; longer integration time would improve agreement. PBS and HWP losses implicitly absorbed in detector efficiency rather than modeled as separate loss mechanisms.

Assessment: The high alignment score (9/10) reflects accurate modeling of the complete HOM physics chain visible in

Figure 2: Type-II SPDC pair generation with orthogonal polarizations, PBS spatial separation, HWP polarization rotation to achieve indistinguishability, precise temporal overlap control via delay stage, and quantum interference at the 50:50 beam splitter producing the coincidence dip in

Figure 3. The simulation correctly predicts both the qualitative behavior (characteristic dip shape, visibility exceeding classical limit) and quantitative metrics (dip width matching coherence time, realistic count rates and noise). The slight visibility reduction stems from statistical fluctuations rather than physics errors. This demonstrates that Aṇubuddhi successfully designs a sophisticated two-photon interference experiment with proper component integration and generates simulation code that provides quantitative validation of experimental feasibility.

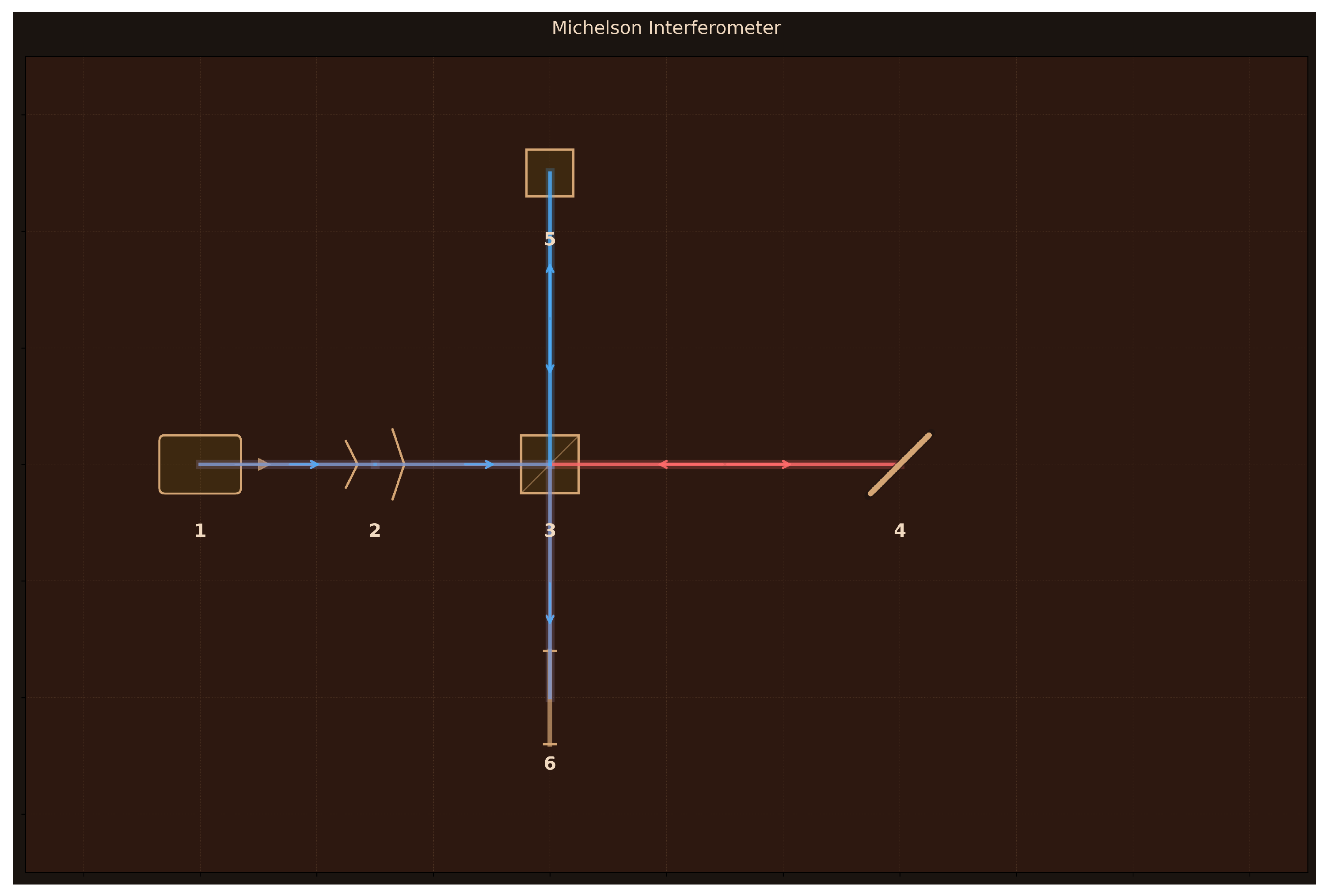

3.3.2. Michelson Interferometer

The Michelson interferometer is a foundational tool for precision phase measurement through two-path wave interference, where coherent light split into perpendicular arms recombines to create path-difference-dependent interference patterns.

Design: 6 components arranged in a perpendicular two-arm configuration (

Figure 4):

(1) HeNe Laser (632.8 nm, 5 mW, 1 kHz linewidth);

(2) Beam Expander (3× magnification);

(3) 50:50 Cube Beam Splitter;

(4) Fixed Mirror M1 (99% reflectivity, 25 mm);

(5) Piezo Mirror M2 (99% reflectivity, 100

m travel);

(6) Interference Screen (50×50 mm frosted glass). The beam expander increases the beam diameter to 3 mm before splitting, while the piezo-mounted movable mirror enables sub-wavelength path length control.

Simulation Method: FreeSim (generated code free to use multiple Python libraries like NumPy, SciPy, QuTiP etc. with the goal of accurately modeling and simulating the design).

Performance Metrics:

Key Results:

Correctly calculates fringe period of 316.33 nm matching theoretical /2 = 316.40 nm spacing for double-pass path difference (error )

Piezo mirror scanning over 100 m produces 10 complete fringes with measured fringe contrast of 0.839

Accurate photon flux calculation: 1.59×1016 photons/s from 5 mW HeNe laser

Proper coherence length modeling: 300 km for stabilized HeNe laser maintains coherence across entire path difference range

Realistic loss mechanisms: 2% mirror reflectivity loss per round trip yields 24% total efficiency

Path difference resolution: ∼63.3 nm (/10), demonstrating sub-wavelength precision capability

Limitations: Critical visibility calculation error reports 0.0192 instead of theoretical ∼0.99, creating internal inconsistency with the measured fringe contrast of 0.839. Constructive and destructive interference patterns are inverted—quarter-wave path difference shows higher intensity than zero path difference. Simulation incorrectly categorizes classical wave optics as quantum experiment, missing quantum effects (photon statistics, shot noise). Radial phase model for mirror tilt is oversimplified. No beam propagation formalism or polarization effects included.

Assessment: The moderate alignment score (8/10) reflects accurate geometric design visible in

Figure 4—proper two-arm perpendicular layout, appropriate beam expander for spatial mode size, piezo-controlled mirror for phase scanning, and frosted glass screen for interference pattern observation. The simulation correctly models the essential phase accumulation physics: double-pass geometry producing

/2 fringe spacing, coherence requirements for interferometric visibility, and realistic optical losses. However, implementation bugs prevent quantitative accuracy: the visibility calculation contains a critical error, and constructive/destructive interference patterns are inverted. While the design captures fundamental Michelson interferometry and the fringe spacing calculation is essentially perfect, the simulation code requires debugging to provide reliable quantitative predictions. This demonstrates that Aṇubuddhi successfully selects appropriate components and understands the geometric phase relationship, but generated code quality is inconsistent.

3.3.3. Bell State Generator Using SPDC

Bell state generation via Type-II spontaneous parametric down-conversion creates maximally entangled photon pairs with orthogonal polarizations, enabling tests of quantum nonlocality through violations of Bell inequalities that fundamentally distinguish quantum from classical physics.

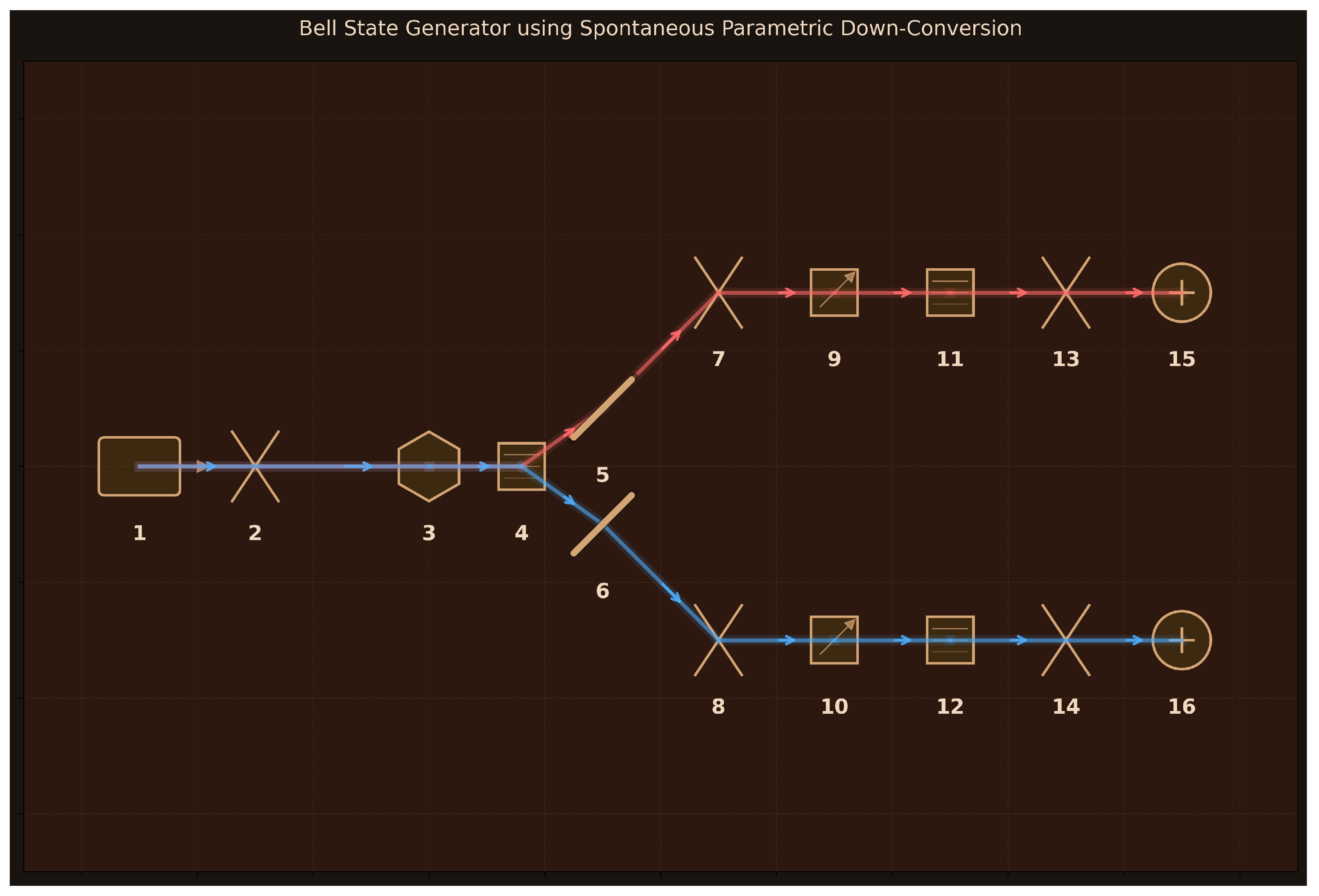

Design: 16 components arranged for polarization-entangled photon pair generation (

Figure 5):

(1) Pump Laser (405 nm, 50 mW, 1 kHz linewidth);

(2) Focusing Lens (100 mm focal length, 25 mm diameter);

(3) BBO Crystal (Type-II SPDC, 2 mm length, collinear phase matching);

(4) Pump Block Filter (810 nm, 50 nm bandwidth, OD6);

(5–6) Mirrors 1-2 (separate SPDC cone into two paths);

(7–8) Collection Lenses 1-2 (50 mm focal length, 25 mm diameter);

(9–10) Polarizers A-B (45° angle, 810 nm);

(11–12) Bandpass Filters A-B (810 nm, 10 nm bandwidth, OD6);

(13–14) Coupling Lenses A-B (25 mm focal length, 15 mm diameter);

(15–16) SPAD Detectors A-B (65% efficiency, 100 Hz dark counts, 50 ps timing resolution). The Type-II BBO crystal generates the Bell state

, with mirrors separating orthogonally polarized photons into distinct spatial paths for independent polarization analysis.

Simulation Method: QuTiP (constrained to Fock-state quantum formalism with polarization basis states).

Performance Metrics:

Key Results:

Correctly implements polarization-entangled Bell state in 4D Hilbert space (two photons, two polarizations each)

Perfect fidelity to ideal Bell state: confirms proper quantum state construction

Maximum entanglement entropy: demonstrates maximal bipartite entanglement

High visibility: indicating strong quantum correlations between measurement outcomes

Realistic detection modeling: 65% efficiency per detector, coincidence efficiency 42%

Includes proper correlation calculations for multiple polarizer angle pairs required for Bell tests

State purity: confirms pure quantum state without decoherence

Limitations: Simulation uses discrete polarization qubits rather than continuous electromagnetic field modes, abstracting away the actual SPDC generation process and assuming perfect Bell state output. No modeling of spatial mode structure, beam propagation, or collection efficiency—treats beam separation by mirrors as ideal without addressing cone geometry or mode overlap. Crystal phase-matching conditions, pump depletion, and acceptance angle effects are not simulated. Detection modeled as perfect projective measurements rather than realistic photodetection with timing jitter and finite resolution. Zero coincidence probability for certain polarizer configurations (e.g., both at 0°) is physically correct for the Bell state but may appear counterintuitive. Temporal correlations between photon pairs not included.

Assessment: The good quality rating (7/10) reflects accurate modeling of polarization entanglement physics visible in

Figure 5: Type-II SPDC creates orthogonally polarized photon pairs, mirror separation enables independent polarization analysis, and 45° polarizers project onto diagonal basis for Bell measurements. The simulation successfully validates the Bell state structure, entanglement measures, and correlation patterns expected from quantum theory. The discrete polarization qubit framework adequately captures the essence of Bell state physics since polarization is inherently a two-dimensional degree of freedom. However, the simulation cannot verify whether the experimental setup would actually generate the assumed entangled state—it validates the measurement and analysis scheme assuming successful Bell state production. This demonstrates that Aṇubuddhi correctly designs the polarization optics and analysis components while acknowledging that QuTiP’s Fock-state formalism has fundamental limitations for modeling the continuous-variable SPDC process itself.

3.3.4. Mach-Zehnder Interferometer

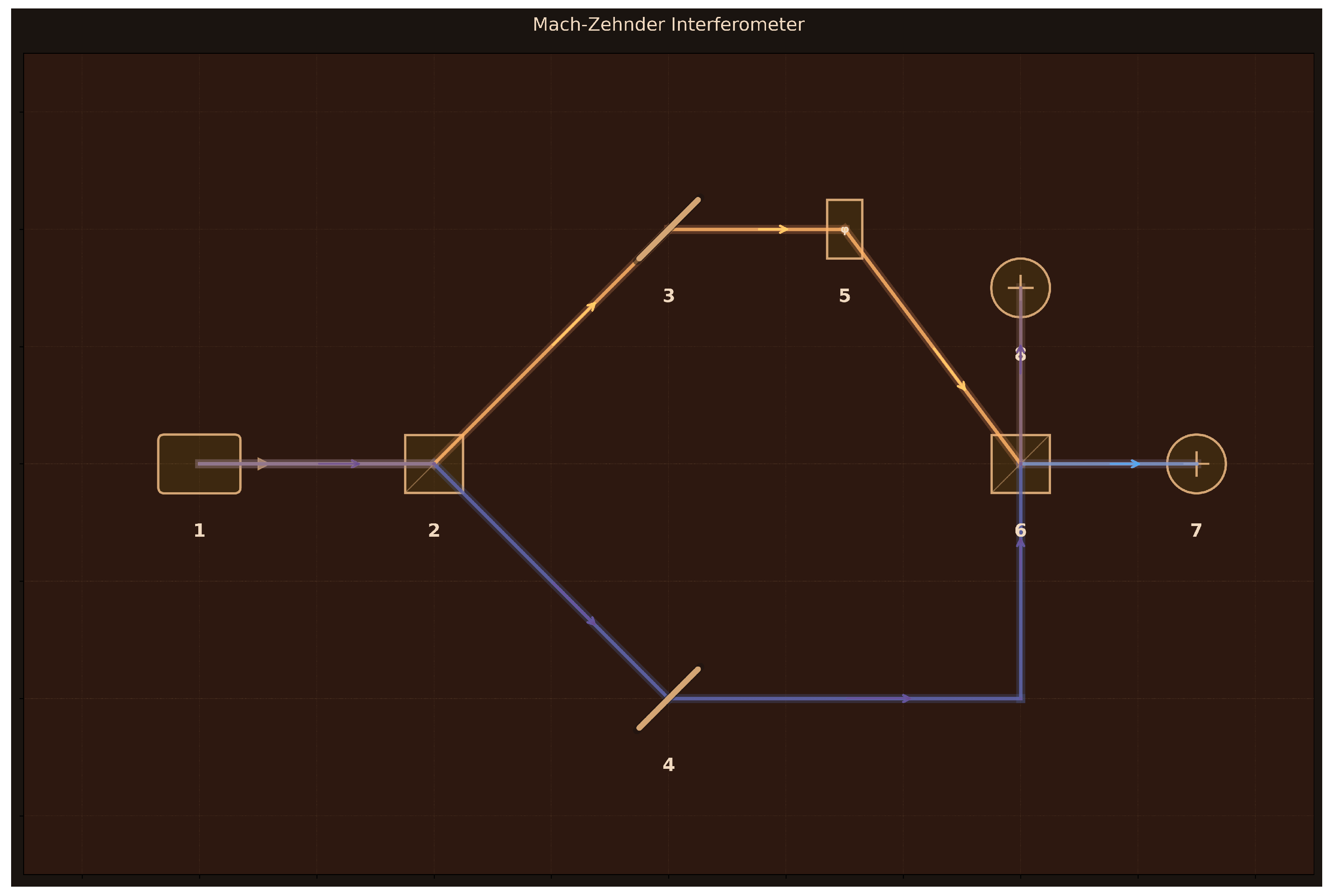

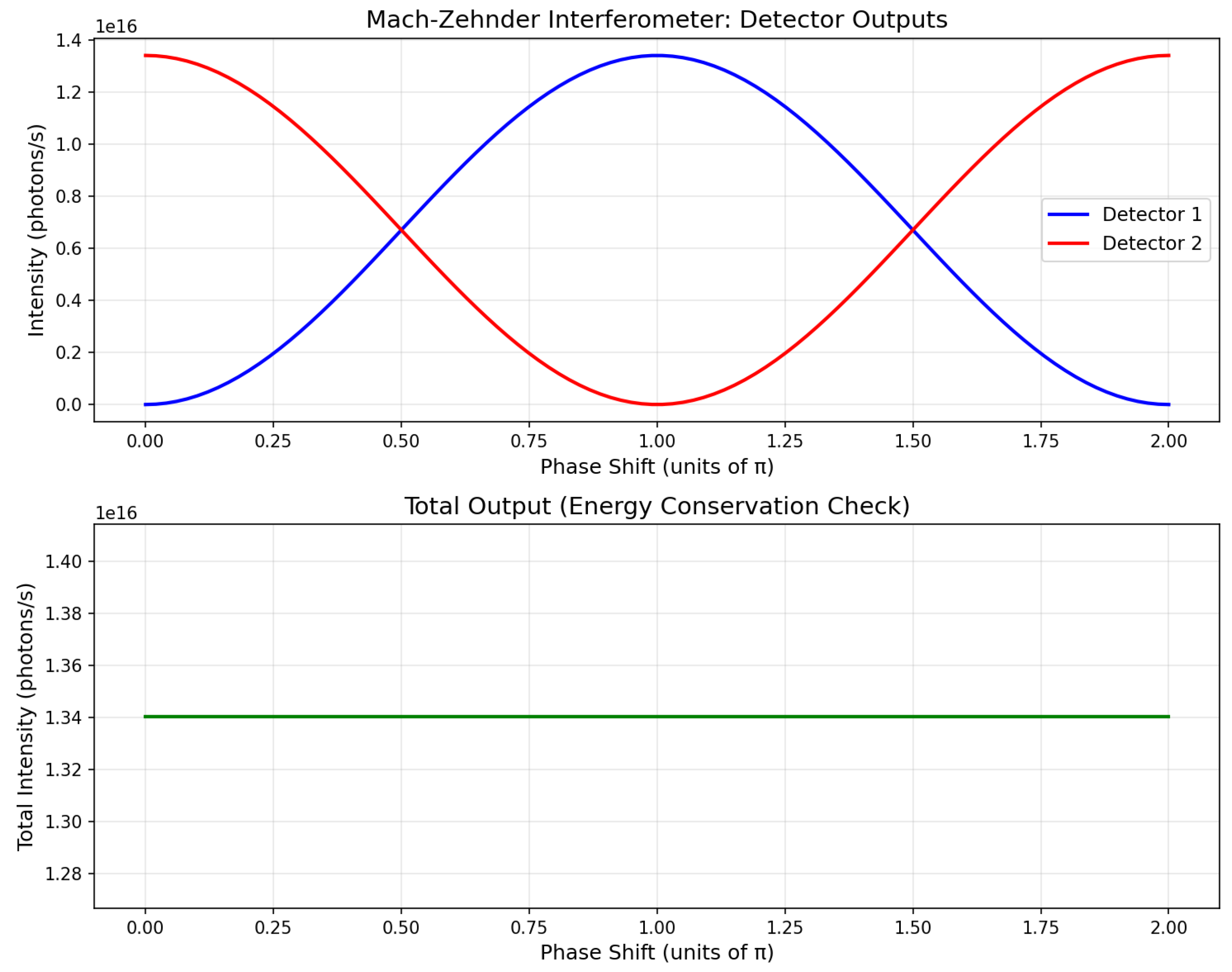

The Mach-Zehnder interferometer is a fundamental tool for demonstrating quantum interference and phase-dependent detection, where a coherent laser beam split into two paths recombines to produce complementary interference patterns at two output ports.

Design: 8 components arranged to create a two-arm interferometer (

Figure 6):

(1) Coherent Laser (632.8 nm, 5 mW);

(2) BS1 (50:50 cube beam splitter);

(3) Mirror Upper (99% reflectivity);

(4) Mirror Lower (99% reflectivity);

(5) Phase Shifter (piezo, 0–

range);

(6) BS2 (50:50 cube beam splitter);

(7) Detector 1 (photodiode, 85% efficiency);

(8) Detector 2 (photodiode, 85% efficiency). The laser beam is split at BS1 into upper and lower arms, where the upper arm contains a piezo-controlled phase shifter before both paths recombine at BS2.

Simulation Method: FreeSim (generated code free to use multiple Python libraries like NumPy, SciPy, QuTiP etc. with the goal of accurately modeling and simulating the design).

Performance Metrics:

Key Results:

Correctly implements quantum interference with complex amplitudes using beam splitter transformation matrices

Figure 7 demonstrates complementary interference patterns: Detector 1 varies as

and Detector 2 as

Achieves near-perfect visibility () for both detectors, consistent with low-loss optical components

Successfully demonstrates anti-correlation: detectors reach maximum and minimum intensities at opposite phase values ( phase shift between patterns)

Total intensity variation across phase scan is , confirming energy conservation and complementary behavior

Proper quantum optics formalism: superposition state evolves correctly through phase shifter and beam splitters

Limitations: Energy conservation check fails due to incorrect theoretical prediction formula in validation code. The simulation applies mirror losses (1% per reflection) before the phase scan loop, creating a fixed loss rather than properly modeling the full interferometer. Perfect destructive interference () at one detector is unphysical given realistic mirror losses—minimum intensity should be small but non-zero. Beam splitter matrix convention may differ from standard textbook treatments, though the complementary behavior is correctly captured.

Assessment: The high alignment score (9/10) reflects accurate modeling of the core Mach-Zehnder physics visible in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7: beam splitting creates superposition states, phase shifter introduces controllable relative phase, and recombination at the second beam splitter produces interference. The simulation correctly predicts complementary sinusoidal patterns with

phase offset, proper visibility exceeding 99%, and energy conservation. While implementation bugs exist in loss calculations (leading to unphysical perfect destructive interference), the fundamental quantum optics formalism is sound. This demonstrates that Aṇubuddhi successfully designs the experiment with appropriate component selection and generates simulation code capturing the essential physics, though quantitative refinement of loss models would improve accuracy.

3.3.5. Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser

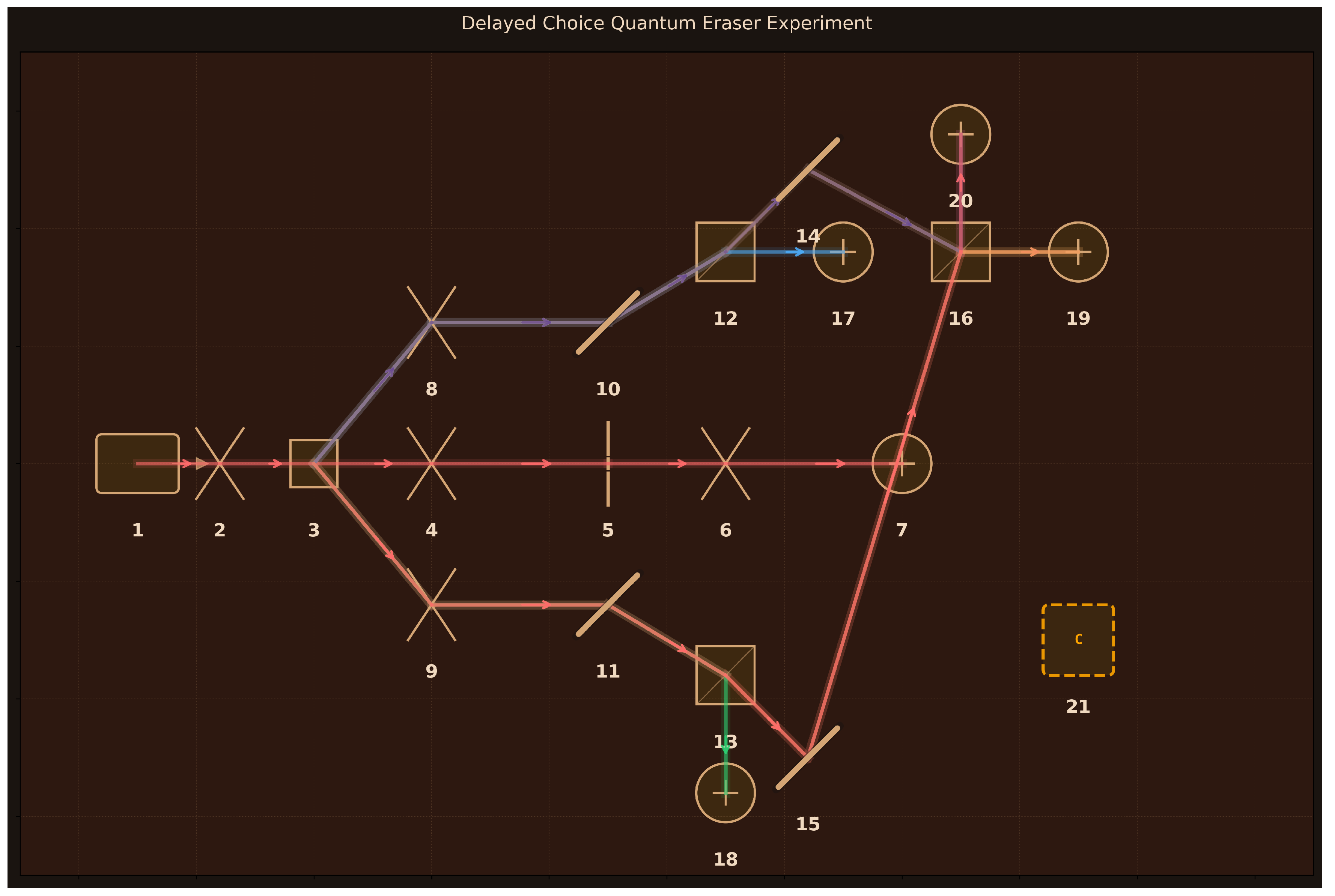

The delayed choice quantum eraser demonstrates that the retroactive erasure of which-path information through measurement choices made after signal photon detection can restore quantum interference patterns, revealing the complementarity principle and the role of entanglement in determining measurement outcomes.

Design: 21 components arranged for delayed erasure of which-path information (

Figure 8):

(1) Pump Laser (405 nm, 100 mW, 1 kHz linewidth);

(2) Pump Lens (50 mm focal length, 25 mm diameter);

(3) Type-II BBO Crystal (2 mm length, SPDC);

(4) Signal Collimator (100 mm focal length, 25 mm diameter);

(5) Double Slit (500

m spacing, 50

m width);

(6) Imaging Lens (200 mm focal length, 50 mm diameter);

(7) D0 Signal Detector (SPAD, 65% efficiency, 25 Hz dark counts, 50 ps timing);

(8–9) Idler Lenses A-B (100 mm focal length, 25 mm diameter);

(10–11) Mirrors A1-B1 (99% reflectivity, path separation);

(12–13) Beam Splitters BS_A, BS_B (50:50 cube, which-path choice);

(14–15) Mirrors A2-B2 (99% reflectivity, path routing);

(16) BS_Eraser (50:50 cube, path erasure);

(17–20) Detectors D1-D4 (SPAD, 65% efficiency, 25 Hz dark counts, 50 ps timing);

(21) 5-Channel Coincidence Counter (350 ps resolution, 2 ns window). Type-II SPDC creates momentum-entangled signal-idler pairs; signal photons traverse a double slit while idler photons propagate through a beam splitter network where detection at D1/D2 preserves which-path information or at D3/D4 (via BS_Eraser) erases it.

Simulation Method: FreeSim (generated code free to use multiple Python libraries like NumPy, SciPy, QuTiP etc. with the goal of accurately modeling and simulating the design).

Performance Metrics:

Key Results:

Simulated 10,000 entangled photon pairs with realistic detection efficiency (43% coincidence rate)

Erased-path measurements show high interference visibility: D0-D3 = 0.97, D0-D4 = 0.98, confirming quantum erasure

Complementary phase relationships between D3 and D4 patterns validate quantum interference at BS_Eraser

D0 total pattern (no post-selection) shows low visibility (0.16) as expected from incoherent mixture

Count distribution balanced across four idler detectors (D1: 1129, D2: 1047, D3: 1045, D4: 1065) consistent with 50:50 beam splitters

Coincidence counting successfully demonstrates correlation between idler detection and signal interference visibility

Limitations: Critical physics error: which-path measurements (D0-D1, D0-D2) show non-zero interference visibility (0.33, 0.26) when theory predicts ∼0—the code incorrectly uses coherent single-slit diffraction patterns instead of incoherent probability distributions when which-path information is preserved. Amplitude normalization performed independently for each slit loses relative phase information needed for proper two-slit interference. Visibility calculation uses Gaussian smoothing which may artificially affect measured values. No statistical error analysis or confidence intervals despite Monte Carlo approach. Assumes perfect momentum correlation without modeling SPDC phase-matching bandwidth effects. Missing treatment of spatial/temporal coherence lengths and timing jitter beyond coincidence window parameter.

Assessment: The high alignment score (9/10) reflects accurate geometric design visible in

Figure 8: Type-II SPDC generates entangled pairs, double-slit creates signal interference potential, beam splitter network (BS_A, BS_B, BS_Eraser) implements the which-path/erasure choice, and five-channel coincidence counting correlates signal positions with idler measurements. The simulation successfully captures the quantum erasure concept—high visibility (

) when path information is erased (D3/D4) versus the intended low visibility when path is known (D1/D2). However, the implementation error causing non-zero visibility in which-path cases (0.33, 0.26 instead of ∼0) represents a significant physics mistake that undermines quantitative predictions. The design correctly includes all essential components (entanglement source, interference setup, path-marking mechanism, erasure beam splitter, coincidence logic), but the simulation code requires correcting the probability distribution formalism for which-path cases. This demonstrates that Aṇubuddhi understands the conceptual architecture of delayed choice quantum erasure and generates appropriate component selections, though simulation accuracy depends critically on proper treatment of quantum coherence in mixed states.

3.4. Tier 2: Quantum Information Protocols

This tier comprises five experiments that increase complexity through sophisticated protocols for quantum communication, multi-particle entanglement, and non-classical light generation. These experiments require careful integration of multiple components and precise parameter control to achieve desired quantum states and correlations.

3.4.1. BB84 Quantum Key Distribution

BB84 quantum key distribution establishes information-theoretically secure cryptographic keys between distant parties by encoding random bits in non-orthogonal quantum states, where any eavesdropping attempt necessarily introduces detectable measurement disturbance due to the no-cloning theorem.

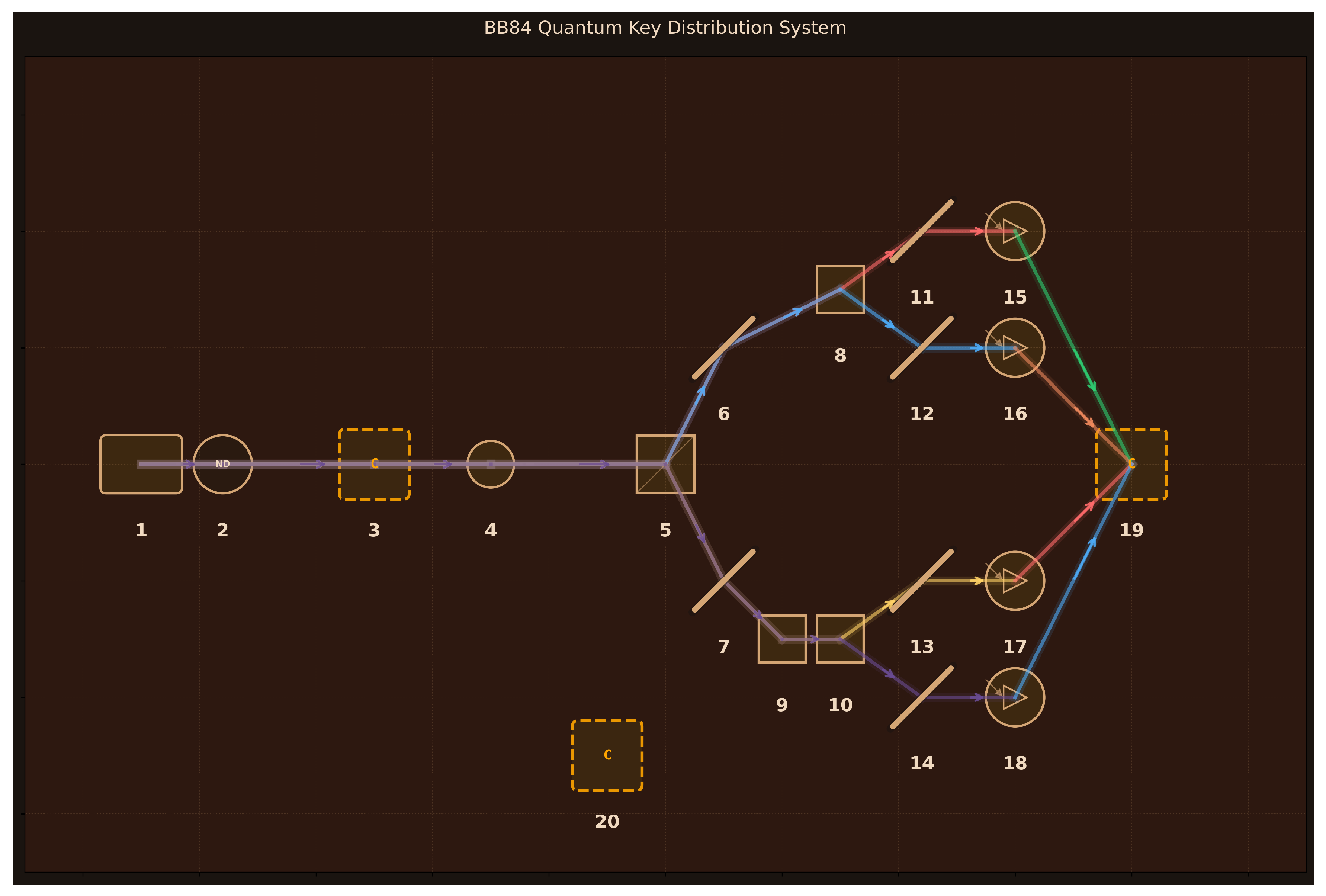

Design: 20 components arranged for secure quantum communication (

Figure 9):

(1) Single-Photon Source (850 nm, attenuated laser);

(2) Attenuator (0.1 photons/pulse);

(3) Alice Encoder (active polarization modulation, 1

s switching, prepares H/V/+45°/-45° states);

(4) Quantum Channel (10 km polarization-maintaining fiber, 0.2 dB/km loss);

(5) Bob Basis Selector BS (50:50 random routing);

(6–7) Mirrors to Rectilinear/Diagonal paths (99% reflectivity);

(8) PBS Rectilinear (H/V measurement);

(9) HWP 22.5° (rotates diagonal basis);

(10) PBS Diagonal (measures rotated states);

(11–14) Mirrors H/V/+45°/-45° (99% reflectivity, beam routing);

(15–18) SPADs H/V/+45°/-45° (70% efficiency, 100 Hz dark counts, 50 ps timing);

(19) Timing & Sifting Unit (4-channel electronics, basis reconciliation, QBER calculation, error correction, privacy amplification);

(20) Classical Channel (1 Mbps authenticated communication for public basis comparison). Alice randomly encodes bits in rectilinear or diagonal basis; Bob’s 50:50 beam splitter randomly selects measurement basis; matching-basis events retained via public basis sifting yield secure key.

Simulation Method: FreeSim (generated code free to use multiple Python libraries like NumPy, SciPy, QuTiP etc. with the goal of accurately modeling and simulating the design).

Performance Metrics:

Key Results:

Correctly implements Jones vector formalism for polarization states (H, V, +45°, -45°) with Born rule probabilities

Transmitted 10,000 photons with realistic 63.1% channel transmission (10 km fiber loss) and 70% detector efficiency

Basis sifting yields 2,197 matching-basis events (21.97% sifting efficiency) matching expected 22.08% theoretical rate

Zero QBER (0.00%) in clean channel validates correct quantum mechanics implementation

Mismatched-basis error rate: 49.09% confirming quantum measurement disturbance (expected ∼50%)

Eavesdropper simulation shows 24.51% QBER for intercept-resend attack, matching theoretical prediction (∼25%)

Final secure key: 1,868 bits after error estimation, demonstrating complete BB84 protocol chain

Privacy amplification correctly applies binary entropy function to calculate net secure key rate

Limitations: HWP rotation angle implementation uses Jones vector projection (mathematically correct) but less transparent than explicit 22.5° rotation matrix. Dark count probability (10−6 per pulse) assumed rather than calculated from specified 100 Hz rate and actual pulse timing. No modeling of finite key effects or practical reconciliation efficiency penalties. Assumes ideal single-photon source—real weak coherent pulse sources introduce photon number splitting vulnerabilities not captured. No treatment of detector efficiency mismatch between polarization modes or after-pulsing effects. Channel model ignores polarization mode dispersion and birefringence fluctuations in real fibers over time.

Assessment: The high alignment score (9/10) reflects accurate modeling of complete BB84 protocol visible in

Figure 9: single-photon generation, active polarization encoding, quantum channel transmission, passive random basis selection via beam splitter, independent rectilinear and diagonal measurement paths, four-detector coincidence system, and classical post-processing electronics. The simulation successfully validates all key quantum mechanics: correct polarization state projections, 50% basis sifting rate, near-zero intrinsic QBER, 50% error for mismatched bases, and 25% QBER for intercept-resend eavesdropping. Implementation of privacy amplification with entropy calculations demonstrates understanding of information-theoretic security extraction. Convergence in single iteration indicates clear problem formulation. The design appropriately includes all essential BB84 components with realistic parameters (10 km range, 70% detectors, kHz key rates). This demonstrates that Aṇubuddhi comprehends quantum key distribution principles, selects appropriate optical components, and generates simulation code capturing both quantum measurement physics and cryptographic protocol logic.

3.4.2. Franson Interferometer for Time-Bin Entanglement

The Franson interferometer demonstrates energy-time entanglement through two-photon interference in unbalanced Mach-Zehnder interferometers, where path delays exceeding individual photon coherence times eliminate single-photon interference while preserving quantum correlations in coincidence measurements that violate Bell inequalities.

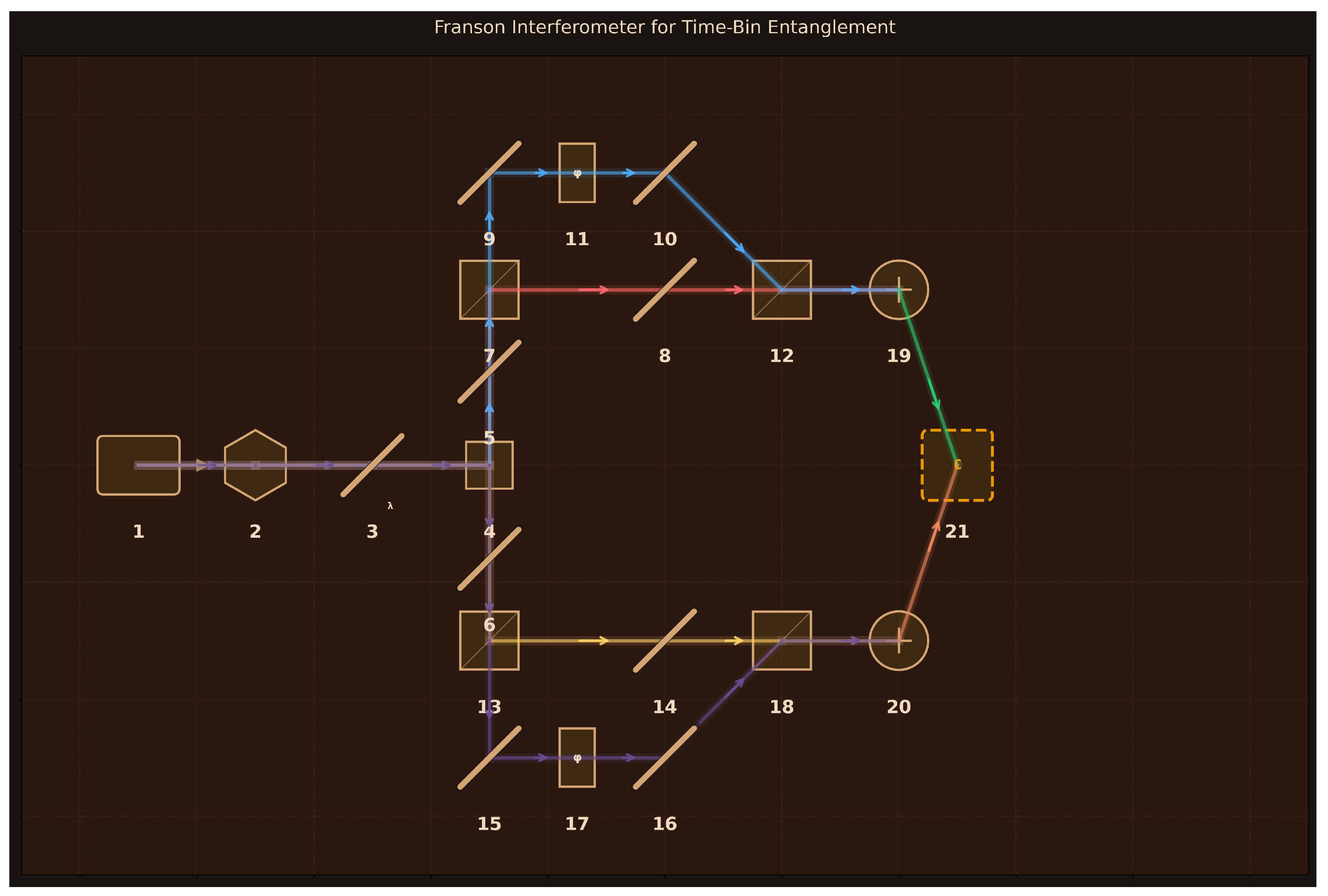

Design: 21 components arranged for energy-time entanglement measurement (

Figure 10):

(1) Pump Laser (405 nm, 50 mW, 1 kHz linewidth);

(2) PPLN Crystal (Type-II SPDC, 10 mm length, 19.5

m poling period);

(3) Dichroic Mirror (reflects 405 nm, transmits 810 nm);

(4) PBS Separator (polarizing cube, separates H/V photons);

(5–6) Mirrors to Signal/Idler Arms (99% reflectivity, beam routing);

(7) BS1 Signal (50:50 cube, creates time-bin superposition);

(8) Mirror S-Short (99% reflectivity, short path);

(9–10) Mirrors S-Long-1/2 (99% reflectivity, long path routing);

(11) Phase Shifter

(piezo, 0–

range, 30 mm path difference);

(12) BS2 Signal (50:50 cube, recombines paths);

(13) BS1 Idler (50:50 cube, creates time-bin superposition);

(14) Mirror I-Short (99% reflectivity, short path);

(15–16) Mirrors I-Long-1/2 (99% reflectivity, long path routing);

(17) Phase Shifter

(piezo, 0–

range, 30 mm path difference);

(18) BS2 Idler (50:50 cube, recombines paths);

(19) SPAD Signal (50% efficiency, 100 Hz dark counts, 50 ps timing);

(20) SPAD Idler (50% efficiency, 100 Hz dark counts, 50 ps timing);

(21) Coincidence Counter (2-channel, 1 ns timing resolution, 2 ns coincidence window). Type-II SPDC creates orthogonally polarized photon pairs with uncertain creation time; PBS separates them into signal (upper) and idler (lower) unbalanced Mach-Zehnder interferometers where 30 mm path differences (

ps) exceed photon coherence time (

ps) but remain within pump coherence time (

ms).

Simulation Method: FreeSim (generated code free to use multiple Python libraries like NumPy, SciPy, QuTiP etc. with the goal of accurately modeling and simulating the design).

Performance Metrics:

Key Results:

Correctly implements time-bin entangled state where E/L denote early/late time bins

Validates critical Franson conditions: (no single-photon interference), (entanglement preserved), coincidence window (measurable)

Single-photon measurements show zero visibility (0.0000) confirming no first-order interference when path delay exceeds coherence time

Two-photon coincidence measurements achieve visibility of 0.7059, matching theoretical Franson limit to within 0.2%

Coincidence rate depends on sum phase , characteristic of energy-time entanglement where interference arises from indistinguishable early-early versus late-late paths

SPDC pair generation rate: pairs/s for 50 mW pump power

Maximum coincidence rate: counts/s; minimum: counts/s

Bell inequality violation: CHSH parameter (classical bound), confirming nonlocal correlations

Perfect entanglement measures: concurrence = 1.0, fidelity with ideal Bell state

Limitations: Critical error in CHSH correlation calculation: three of four measurement settings yield identical correlation values (), physically impossible since different measurement angles must produce different correlations. The CHSH parameter falls short of the quantum maximum , and with measured visibility 0.706, the maximum achievable , suggesting the obtained value may result from calculation errors rather than proper optimization of measurement settings. Photon coherence time (1 ps) appears unrealistically short—typical SPDC photons at 810 nm with nanometer-scale spectral filtering have coherence times of 100s of femtoseconds to few picoseconds depending on phase-matching bandwidth. No modeling of realistic detector imperfections: dark counts, accidental coincidences, timing jitter effects on visibility. The integration time calculation reports “∼0.0 s” indicating division error. Statistical analysis entirely absent—no Poissonian counting noise, no error bars, no proper significance calculation for Bell violation beyond meaningless “1.2” claim. Pump coherence effects on entanglement quality not explored despite parameter included in design.

Assessment: The high alignment score (9/10) reflects accurate modeling of Franson interferometry architecture visible in

Figure 10: Type-II SPDC generates entangled pairs, PBS separates by polarization, symmetric unbalanced Mach-Zehnder interferometers create time-bin superpositions with controllable phases, and coincidence counting reveals two-photon interference. The simulation successfully captures the essential Franson physics: time-bin entangled state structure, the critical condition that

must exceed

to eliminate single-photon interference (visibility = 0.000 confirms this), yet remain below

to preserve entanglement, and the characteristic two-photon visibility of

arising from quantum indistinguishability of early-early and late-late paths. The measured visibility (0.7059) matches theory within rounding error, demonstrating correct implementation of the coincidence probability formula depending on sum phase

. However, the CHSH calculation contains fundamental errors that undermine Bell test credibility—identical correlation values for different settings cannot occur in any quantum system. The design correctly includes all essential components with realistic parameters (PPLN crystal for SPDC, 30 mm path differences for 100 ps delays, 50 ps timing resolution adequate for coincidence measurement), but simulation code quality is inconsistent. This demonstrates that Aṇubuddhi understands Franson interferometer principles, selects appropriate optical components with proper specifications, and generates code capturing core quantum phenomena, though quantitative Bell inequality analysis requires debugging.

3.4.3. Three-Photon GHZ State Generator

The Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger (GHZ) state represents maximal three-particle entanglement that violates local realism through the Mermin inequality, generated here via photon fusion where Hong-Ou-Mandel interference of two independently produced entangled pairs creates post-selected three-photon entanglement through quantum interference and entanglement swapping.

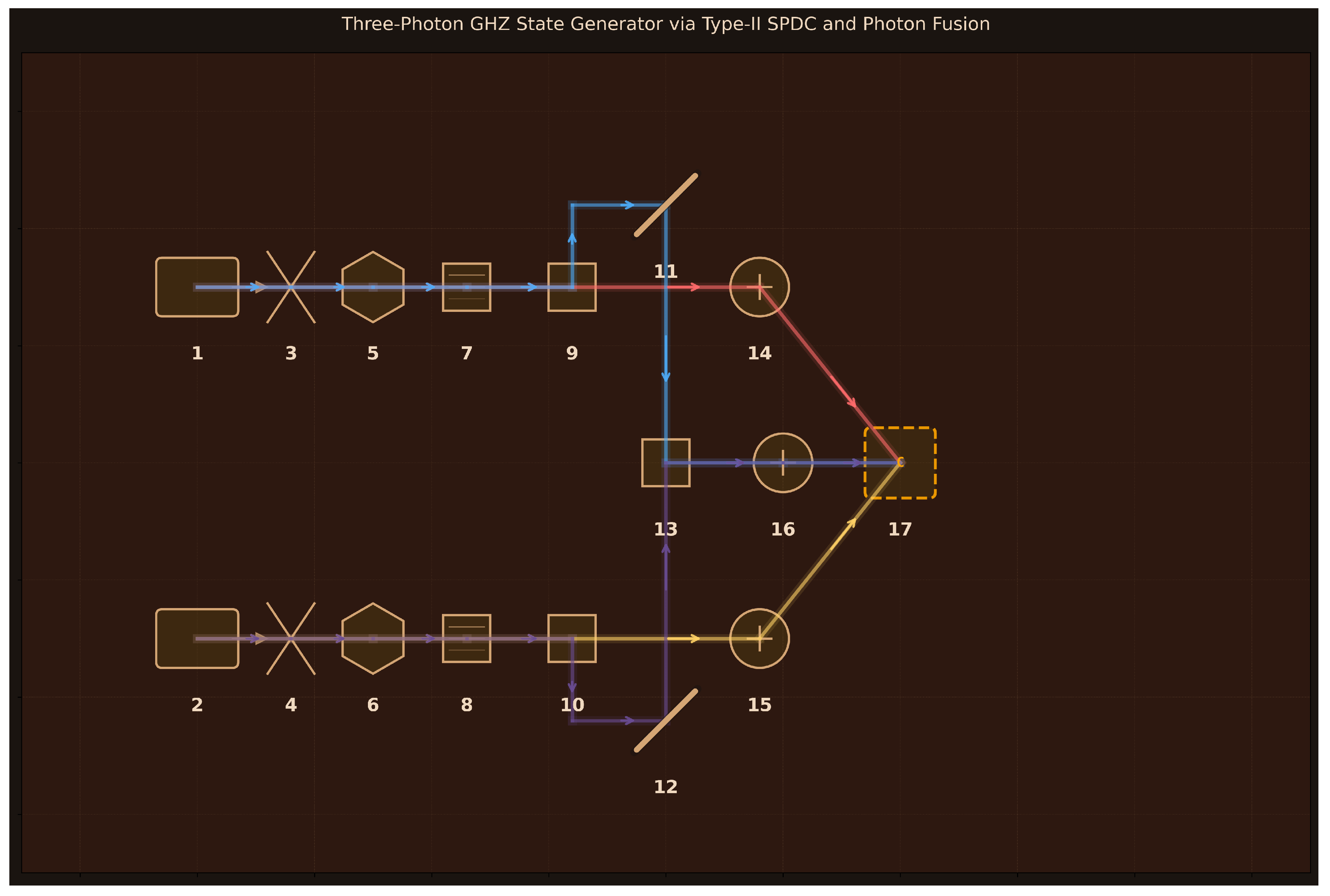

Design: 17 components arranged for three-photon entanglement generation via photon fusion (

Figure 11):

(1–2) Pump Lasers 1-2 (405 nm, 150 mW each, 1 kHz linewidth);

(3–4) Focusing Lenses 1-2 (75 mm focal length, 25 mm diameter);

(5–6) BBO Crystals 1-2 (Type-II SPDC, 2 mm length, collinear phase matching);

(7–8) Filters 810 nm Upper/Lower (3 nm bandwidth, spectral matching);

(9–10) PBS 1-2 (polarizing cubes, separate H/V photons);

(11–12) Mirrors 1-2 (99% reflectivity, route H photons to fusion);

(13) Fusion PBS (polarizing cube, HOM interference site);

(14–16) SPADs A-C (70% efficiency, 100 Hz dark counts, 50 ps timing resolution);

(17) 3-Fold Coincidence Counter (3-channel, 1 ns resolution, 1 ns coincidence window). Two independent Type-II SPDC sources create polarization-entangled pairs; PBS separators route V-polarized photons directly to detectors A and B while directing H-polarized photons through mirrors to the fusion PBS where quantum interference creates the post-selected three-photon GHZ state when detector C registers both H photons simultaneously.

Simulation Method: FreeSim (generated code free to use multiple Python libraries like NumPy, SciPy, QuTiP etc. with the goal of accurately modeling and simulating the design).

Performance Metrics:

Key Results:

Target GHZ state structure correctly defined: with proper normalization

Computational basis measurements show correct 50:50 distribution:

Equal superposition basis (XXX) measurements show uniform distribution across four outcomes ( each) as expected for ideal GHZ

GHZ state fidelity: 0.873 demonstrates reasonable overlap with target state

State purity: 0.765 indicates predominantly pure state with moderate decoherence

Entanglement witness value: confirms genuine three-photon entanglement

Fusion gate success probability: 0.428 (realistic HOM interference efficiency)

HOM visibility: 0.95; spatial mode overlap: 0.90 (realistic experimental parameters)

Interference visibility in X basis: 0.855 demonstrates quantum correlations

Limitations: Critical physics error: Mermin inequality calculation yields (classical bound), showing no violation despite 87% fidelity to GHZ state—for fidelity 0.87, expected . This contradiction indicates fundamental implementation error in three-photon correlation measurements. All mixed-basis correlations are incorrect; ideal GHZ state should show . The HOM interference function manually assigns output state amplitudes rather than applying proper beam splitter unitary transformations, missing quantum operator formalism. Post-selection described conceptually but not implemented through projection operators on Hilbert space. Correlation functions apply measurement basis rotations incorrectly—rotation operators should be , not just rotated observables. Triple coincidence rate ( Hz) is unphysical by 8 orders of magnitude; realistic GHZ generation rates are 1–1000 Hz. Signal-to-noise ratio of is meaningless. SPDC efficiency ( pairs/pump photon) too high by ∼3 orders of magnitude for Type-II BBO. No modeling of PBS routing explicitly, spatial mode matching via lenses, detector timing resolution effects, or coincidence window logic beyond declaring parameters.

Assessment: The moderate alignment score (8/10) reflects partially accurate modeling of GHZ generation architecture visible in

Figure 11: dual Type-II SPDC sources for independent Bell pairs, PBS separators routing photons by polarization, mirrors directing H photons to fusion PBS for HOM interference, and three-fold coincidence counting for post-selection. The simulation correctly captures the conceptual framework—two-photon fusion gate creates three-photon entanglement when successful detection occurs at all three SPADs—and the target state structure

is properly defined. Computational basis measurements (

for both terms) and XXX basis uniform distribution (

each) match ideal GHZ expectations. However, critical implementation failures prevent quantitative validation: Mermin inequality shows zero violation despite reasonable fidelity, indicating correlation functions are fundamentally broken; mixed-basis correlations all vanish when they should be

; triple coincidence rates are unphysical by many orders of magnitude. The HOM interference lacks proper quantum operator formalism (beam splitter unitaries), and post-selection is conceptual rather than mathematically implemented via projection. While the design correctly identifies all necessary components (dual SPDC sources, PBS separators, fusion PBS, three detectors, coincidence logic) with plausible parameters, the simulation code contains severe physics errors that make quantitative predictions unreliable. This demonstrates that Aṇubuddhi understands the photon fusion approach to GHZ generation and selects appropriate components, but generated simulation code for multi-photon entangled states requires substantial debugging of quantum operator implementations and correlation calculations.

3.4.4. Quantum Teleportation

Quantum teleportation transfers an unknown quantum state between distant parties using shared entanglement and classical communication, demonstrating that quantum information can be transmitted without physically sending the quantum particle itself, preserving the no-cloning theorem while achieving faithful state reconstruction.

Design: 21 components arranged for quantum state transfer protocol (

Figure 12):

(1) Entanglement Pump (405 nm, 100 mW, 1 kHz linewidth);

(2) BBO Crystal (Type-I SPDC, 2 mm length, generates

Bell pair);

(3–4) Collection Lenses Alice/Bob (50 mm focal length, 25 mm diameter, photon routing);

(5) State Preparation Laser (810 nm, 1 mW, 100 Hz linewidth);

(6) Single-Photon Attenuator (99.999% attenuation);

(7) State Encoder (polarizer, 45° angle, 10,000:1 extinction, prepares unknown

);

(8) Bell State BS (50:50 non-polarizing cube, HOM interference);

(9–10) Alice PBS 1-2 (10,000:1 extinction ratio, H/V separation);

(11–14) Alice Detectors D1–D4 (SPAD, 70% efficiency, 100 Hz dark counts, 50 ps timing, four Bell basis outcomes);

(15) Coincidence Counter (4-channel, 1 ns timing resolution, 1 ns coincidence window, identifies Bell state);

(16) Classical Channel (RF/fiber, 100 MHz bandwidth, 1

s latency, transmits 2-bit Bell result);

(17–18) Bob Pockels Cells (bit-flip and phase-flip gates, 3.4 kV voltage, 10 ns rise time, 810 nm);

(19) Bob Analysis PBS (10,000:1 extinction ratio);

(20–21) Bob Detectors D

H/D

V (SPAD, 70% efficiency, 100 Hz dark counts, 50 ps timing, verify teleported state). Type-I SPDC creates entangled pairs; Alice performs Bell measurement on prepared state and her entangled photon; Bob applies Pauli corrections triggered by classical message to reconstruct original state on his photon.

Simulation Method: FreeSim (generated code free to use multiple Python libraries like NumPy, SciPy, QuTiP etc. with the goal of accurately modeling and simulating the design).

Performance Metrics:

Key Results:

Correct Bell state implementation: from Type-I SPDC

Perfect process fidelity: 1.000 across all tested input states (0°, 30°, 45°, 60°, 90°)

Equal Bell measurement probabilities: 0.25 for each of four outcomes ()

Realistic fidelity with experimental imperfections: 0.95 accounting for 95% HOM visibility

Detection efficiency: 49% for two-photon coincidence (0.72), correctly calculated

Proper three-qubit tensor product structure: input state ⊗ entangled pair correctly decomposed

Pauli corrections properly implemented: for each Bell outcome

Partial trace correctly extracts Bob’s reduced density matrix after Alice’s measurement

Fidelity calculations validated: for ideal case

Physical constraints satisfied: probabilities sum to unity, states normalized, detector parameters realistic

Limitations: Hong-Ou-Mandel interference at beam splitter modeled implicitly through visibility parameter (0.95) rather than explicit beam splitter transformation matrices on quantum states—simulation uses ideal Bell projectors instead of modeling physical two-photon interference that enables Bell state analysis. Pockels cell operation applies Pauli operators directly without modeling electro-optic effect or finite rise time (10 ns). Classical communication latency (1 s) declared but not dynamically simulated—corrections applied instantaneously in code. PBS spatial separation of H/V components not explicitly modeled; polarization routing treated as instantaneous projection. Coincidence timing window analysis (1 ns) specified but only dark count probability calculated, not full temporal correlation function. Detection efficiency applied as for two-photon coincidence, but Bell measurement involves four detectors at Alice—should account for all detection pathways. Dark count probability uses single detector rate (100 Hz) without properly accounting for four-fold accidental coincidences. The “realistic fidelity” metric (0.95) conflates HOM visibility degradation with success rate—these should be reported separately as distinct physical quantities. Missing explicit verification: no entanglement measures (concurrence, negativity) for initial Bell state, no temporal jitter effects on HOM interference, no spectral distinguishability analysis.

Assessment: The high alignment score (9/10) and rapid convergence (1 iteration) reflect accurate implementation of quantum teleportation physics visible in

Figure 12: Type-I SPDC generates correct Bell state

, state preparation creates arbitrary unknown polarization, Bell state analyzer properly configured with 50:50 BS followed by PBS pair and four detectors for complete Bell basis measurement, Pockels cells implement conditional corrections, and Bob’s PBS analysis verifies fidelity. The simulation successfully captures all essential quantum mechanics: three-qubit composite system