Introduction

Most terrestrial plants form symbiotic associations with mycorrhizal fungi, such as arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi, ectomycorrhizal (EM) fungi, orchid and ericoid mycorrhizal fungi, which are critical for successful growth and completion of life cycles in natural ecosystems (Smith & Read, 2008; Tedersoo et al.; 2020). Among these, AM associations are the most widespread, occurring in approximately 80% of land plant species, while EM associations predominantly occur in forest ecosystems, especially among 60% of woody plant species (Smith & Read, 2008; Anthony et al.; 2022).

These symbiotic partnerships profoundly influence physiological and ecological processes, including resource allocation (photosynthetically fixed carbon) between roots and fungal mycelia, root exudation, mineral weathering, enzyme production, plant defense mechanisms, community composition and responses to environmental change (Tedersoo & Bahram, 2019). Mycorrhizal fungi are widely recognized for their role in enhancing plant mineral nutrition, particularly under conditions of low nitrogen and phosphorus availability (Smith et al.; 2011; Tedersoo & Bahram, 2019). Moreover, they support host plants in mitigating both abiotic and biotic stresses, such as drought, salinity, heavy metal contamination, and pathogenic attacks (Castaño et al.; 2023; Dreischhoff et al.; 2020; Janeeshma & Puthur, 2020; Wahab et al.; 2023). These benefits are mediated through a combination of direct mechanisms (e.g.; absorption of toxic compounds by extraradical hyphae) and indirect physiological or morphological adjustments in the host (Dreischhoff et al.; 2020; Janeeshma & Puthur, 2020; Wahab et al.; 2023).

Although it is often assumed that plant species associate with a single mycorrhizal type, mounting evidence suggests that some plants can simultaneously or sequentially form dual mycorrhization with both AM and EM fungi (Chaudhury et al.; 2024; Teste et al.; 2020). This dual-mycorrhizal strategy may occur at different developmental stages or in response to environmental heterogeneity (e.g.; alterations in soil age, soil temperature, salinity or host litter compounds), thereby enhancing plant adaptability (Chaudhury et al.; 2024; Teste et al.; 2020; Teste & Laliberté, 2019). Therefore, dual-mycorrhizal plants demonstrate remarkable flexibility in determining their fungal partners depending on environmental conditions, with the goal of maximizing symbiotic benefits.

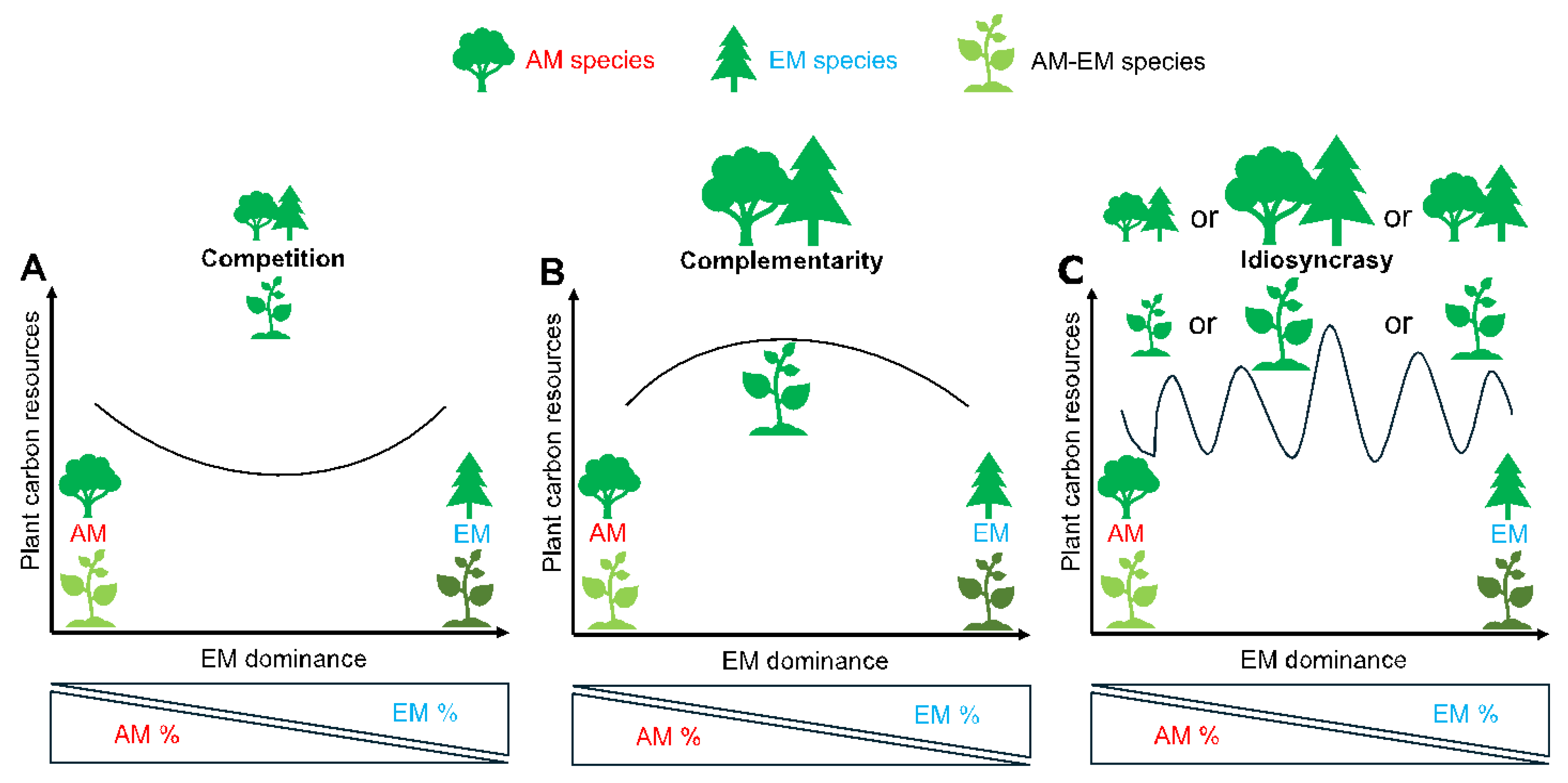

A central question concerns the influence of these mycorrhizal associations on plant carbon (C) accumulation. Two main concepts, i.e.; competition and complementarity, have been proposed to explain the coexistence dynamics of AM and EM fungi (Tedersoo et al.; 2020; Teste et al.; 2020;

Figure 1). The concept of competition posits that differences in nutrient acquisition strategies, root morphology and carbon demand may result in the competitive exclusion of one fungal group under specific environmental conditions (Fernández et al.; 2022; Parasquive et al.; 2025a;

Figure 1A). Conversely, the concept of complementarity suggests that AM and EM fungi can coexist by partitioning ecological niches, either within host plants or at the community level, thereby enhancing overall plant performance and stress tolerance (Luo et al.; 2023; Yang et al.; 2022;

Figure 1B).

However, global change presents increasing uncertainties for mycorrhizal plant productivity. Abiotic stressors such as drought and warming can influence the physiological responses of fungi and their host plants. Furthermore, spatial and temporal heterogeneity, such as differences in location, soil type, or seasonal variation, significantly influences plant aboveground biomass (Albornoz, et al.; 2016a; Luo et al.; 2023; Mao et al.; 2023). Notably, plant C accumulation is not static but fluctuates over time, with evidence pointing to dynamic shifts in the dominance of AM versus EM fungi in response to spatial-temporal factors including plant and fungal species identity, soil age and fertility, climate, and anthropogenic disturbance (Lambers et al.; 2008; Mao et al.; 2024; Rapaport et al.; 2024; Teste et al.; 2020). Dual mycorrhization may provide plants with enhanced flexibility and resilience to these fluctuating conditions by allowing them to simultaneously or sequentially benefit from the complementary functions of both AM and EM fungi, though this phenomenon remains relatively understudied.

To enhance our ability to predict and manage the productivity of mycorrhizal plant communities, particularly under fluctuating environmental conditions, we propose addressing the following key research questions:

1. Which environmental factors predominantly influence the productivity of dual-mycorrhizal plant species or mixed forests with both AM and EM tree species?

2. Can predictive models be developed to simulate the growth and C dynamics of dual-mycorrhizal plants or AM-EM species mixtures in forests under complex environmental scenarios?

3. To what extent can the growth and resilience of dual-mycorrhizal plants or AM-EM species mixture in forests be managed under varying climatic and edaphic conditions?

Building upon current evidence, we then propose a reconciling strategy hypothesis that dual-mycorrhizal plants or a certain proportion of AM-EM species mixtures exhibit flexibility and resilience, enabling dynamic shifts in plant C accumulation in response to environmental pressures across temporal and spatial gradients. This pattern appears to be highly context-dependent or idiosyncratic (

Figure 1C), meaning that the shifts in plant C accumulation may not follow a consistent trend across different species, sites, or environmental conditions. Given the limited empirical evidence from existing studies, we tentatively describe the factors driving these seemingly idiosyncratic patterns, acknowledging that they may vary in timing, magnitude, or direction depending on specific ecological contexts. To evaluate the relative importance of competition, complementary or the context-dependency in plant carbon accumulation, we first examine the ecological consequences of the coexistence of AM and EM fungi within single hosts or as a mixture of AM and EM tree species at the community level under different environmental conditions, and then we introduce a conceptual framework for dynamic plant C accumulation (

Figure 1). In this article, we examine two ecological contexts: (1) AM and EM dual-mycorrhizal colonization within individual plants, and (2) mixture of AM- and EM-associated tree species within forest communities (as indicated in

Figure 1). We include both cases in our analysis with the aim of drawing general conclusions, notably because the studies considered differ in how they assign mycorrhizal types. For example, one study proposes that the basal area of dual-mycorrhizal tree species in stands is assigned as half AM and half EM in the calculation of mycorrhizal proportion (Luo et al.; 2023), whereas another excludes dual-mycorrhizal trees from both AM or EM categories (Mao et al.; 2023). To improve the comparability and synthesis of future studies, there is a need to establish standardized criteria for assigning mycorrhizal types, particularly for species capable of forming dual associations.

In this perspective, this article integrates molecular, physiological, and ecological mechanisms, offering a holistic view of how dual-mycorrhizal systems and mixtures of species associating with different mycorrhizal fungi contribute to plant performance and forest resilience. Ultimately, this work aims to synthesize current knowledge and identify general principles underlying the coexistence of two mycorrhizal types and their ecosystem function. By doing so, we seek to offer insights that may guide practical efforts to optimize forest productivity under the pressure of climate change.

Materials and Methods

1. Literature Search for Figure 2-5 and S1-S2

A literature search in the “Web of Science” database and Google scholar was conducted using the words “ectomycorrhiz*” AND “arbuscular mycorrhiz*” AND “plant biomass” OR “productivity”. The selected articles were required to meet the following criteria that included: (ⅰ) a clear statement of EM and AM fungi in the bioassays, (ⅱ) the individual plants were colonized by EM and AM fungi simultaneously or AM- and EM-associated plants were living in the same community, (ⅲ) quantifiable data of plant biomass or its proxies, (ⅳ) a clear statement confirming/quantifying EM colonization or dominance level. No publication bias was applied in the selection of case studies.

2. Data Analysis

The selected articles were further checked to determine whether extra environmental factors are mentioned. Data from supplementary files of the selected articles were prioritized, followed by data extracted from figures using the online tool PlotDigitizer (

https://plotdigitizer.com/). For model selection, models similar to those used in the original article were prioritized. In

Figure 5C, the mean, standard deviation (SD) and sample size (n) were used to calculate the standardized mean difference (SMD), a robust effect size for comparing continuous variable data between the experimental (with fertilization) and control (without fertilization) groups. Because the article provides standard error (SE) instead of SD, the following equation was used to calculate the SD.

Effect sizes for the impacts of fertilization on plant biomass or related proxies in AM- and EM-dominated rainforests were quantified using the metacont function from the R package meta (Schwarzer, 2007; Balduzzi et al.; 2019). Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were calculated using Hedges’ method, which is well suited for comparing groups with small sample sizes. For each response variable, we estimated the mean effect size and its 95% confidence interval (CI). Positive Hedges’ values indicate that fertilization enhanced host productivity, whereas negative values indicate a reduction. The mean effect size was considered significant when the CI excluded zero (Borenstein, 2009).

All statistical analyses and figure generation (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 and S1-S2) were performed in R version 4.4.1 (R Core Team, 2024) within RStudio version 2024.04.2+764 (Posit Software, 2024).

The Competition in AM and EM Interaction

Ecological Background

AM and EM fungi have different host ranges, nutrient acquisition strategies and ecological roles and have been reported to form competitive relationships between their hosts (Booth, 2004; Tedersoo et al.; 2020; Van Nuland et al.; 2023; Parasquive et al.; 2025ab). Since AM networks can be antagonistic to their EM hosts and influence plant community composition, one perspective suggests that AM and EM symbioses should not be simply viewed as mutually exclusive plant strategies (Janos et al.; 2013; McHugh & Gehring, 2006). For example, the richness of Glomeromycota, most of which form AM associations, is higher in monotypic AM tree combinations than the one in AM-EM species mixtures, suggesting a potential dilution or suppression effect of AM by EM trees and their associated mycorrhizal fungi (Heklau et al.; 2021). Numerous factors and mechanisms contribute to the competition between AM and EM associations, including soil pH and nutrient availability, host plant root competition and C resource allocation by plants. For instance, decreases in AM fungal diversity, colonization and biomass may result from competition with EM hosts for soil resources (Knoblochová et al.; 2017). Similarly, EM hosts have been reported to exert strong negative effects on the survival or growth of the AM-associated trees, probably because alterations in N availability affect competition between tree species with distinct resource acquisition strategies (Booth, 2004; Nave et al.; 2013; Parasquive et al.; 2025ab). These competitive effects can occur in different ecosystems, including low-fertility and drought-prone forests, temperate forests and under controlled conditions (McHugh & Gehring 2006; Parasquive et al.; 2025ab; Van Nuland et al.; 2023). However, in some cases, competition between the two mycorrhizal types appears to be asymmetric: AM hosts suppress the development of EM tree seedlings significantly, while EM hosts do not exert similar effects on AM hosts or their associated fungi (Fernández et al.; 2022).

Overall, these cases highlight that AM-EM mixtures should not be viewed as alternative plant adaptations or simply as mutually exclusive strategies. Although competition between them is evident, it may arise from various ecological factors. Several physiological mechanisms can either enhance or mitigate this competition, jointly shaping plant community outcomes during succession.

Physiological Factors

Physiologically, EM fungi form dense hyphal sheaths (mantles) around roots, which may physically limit access of AM fungi to cortical cells (Smith & Read, 2008). As such, their presence may exclude AM fungi from colonizing the same root regions. For example, when AM fungi pre-colonize plant roots, EM fungi can subsequently access lateral roots through hyphal spread; however, when the sequence of colonization is reversed, the entry of AM fungi into the same root region is not observed (Chilvers et al.; 1987). Additionally, EM fungi can impact AM colonization by causing the host plant to reduce the production of fine roots, thereby limiting the availability of new roots for AM fungi to colonize (Chen et al.; 2000). Therefore, the sequence of colonization and root structure influences competitive success and dominance levels.

Plant C trade-off is another physiological factor, notably because it influences the allocation of C resources between the host plants and the different types of mycorrhizae, ultimately affecting plant growth and competition with neighboring plants. Generally, EM fungi require more C investment than AM fungi, up to 30% of plant-fixed carbon, probably due to their more complex structures and energetically costly nutrient acquisition strategies and also maintenance costs (Ekblad et al.; 1998; Högberg et al.; 2010; Nehls & Hampp, 2000; Phillips et al.; 2013; Hawkins et al.; 2023). Therefore, in C-limited environments, such as shaded understories, AM fungi maintain dominance due to their lower C demands, while in C-rich environments like mature forest canopies, EM fungi can outcompete AM fungi and dominate overstory forests despite their higher C requirements from hosts (Phillips et al.; 2013; Read & Perez-Moreno, 2003).

Additionally, enzyme production and organic matter (OM) breakdown also account for the competitive relationship between the two mycorrhizal types. For example, EM fungi can secrete ligninolytic enzymes, such as laccases and peroxidases, enabling them to degrade complex OM and access nitrogen embedded in soil organic material (Courty et al.; 2005; Lindahl & Tunlid, 2015; Pellitier & Zak, 2018). However, AM fungi lack ligninolytic enzymes and rely on extensive hyphal networks to explore soil volume, accessing inorganic nutrients through physical foraging rather than enzymatic decomposition of OM (Lambers et al.; 2008; Smith & Read, 2008). This gives EM fungi an advantage in decomposing OM. As a result, in conifer forests, EM fungi like Rhizopogon and Piloderma dominate in these OM-rich environments due to their enzymatic capabilities (Kluber et al.; 2011; Miyamoto et al.; 2022). These enzymes involved in N and P cycling have also been shown to enhance nutrient availability in Eucalyptus stands, therefore giving EM fungi a competitive edge over AM fungi (Queralt et al.; 2019). Besides enzymes released by fungi, mycorrhizal plants often impede coexistence with other mycorrhizal plants by creating negative plant-soil feedback at multiple spatial scales (Bennett et al.; 2017; Qin & Yu, 2021). Overall, AM and EM fungi and their hosts are commonly determining the consequences of the competition in forest population dynamics.

The above empirical observations provide evidence of mycorrhiza-mediated negative plant-soil feedback on the coexistence of plant species. Therefore, in the future, it is necessary to optimize species combinations for better ecological benefits in mixed forest plantations.

The Complementarity in AM and EM Interaction

Ecological Background

Recent studies have reported several ecological benefits of dual mycorrhization, either within individuals or in AM-EM tree mixtures (Chaudhury et al.; 2024; Heklau et al.; 2021; Teste et al.; 2014). One of the most important advantages is resource partitioning, referring to the allocation of limited resources to avoid interspecific or intraspecific competition in an ecosystem. AM fungi exhibit strong P uptake efficiency through fine hyphae and high-affinity transporters, making them effective in inorganic nutrient-limited soils while demanding relatively low plant C costs (Smith & Read, 2008; Hawkins et al.; 2023; Johnson et al.; 2010). In contrast, EM fungi are better adapted to decompose complex organic N via extracellular enzymes and to access nutrients from organic soil layers, but they require higher C investment from their hosts (Hawkins et al.; 2023; Nehls & Hampp, 2000; Read & Perez-Moreno, 2003). Likewise, although both AM and EM trees respond actively to inorganic P, EM trees acquire more P from complex organic forms such as phytic acid, whereas AM trees show certain capacity to acquire simple organic P such as monophosphate (Liu et al.; 2018). These functional complementarities reduce competition and promote coexistence of dual mycorrhization.

Soil nutrient cycling and carbon dynamics are influenced by contrasting yet complementary functions of EM and AM fungi. On one hand, EM fungi can break down complex organic compounds, releasing N, P, and other nutrients into plant-available forms, providing long-term soil fertility (Lindahl & Tunlid, 2015; Read & Perez-Moreno, 2003). On the other hand, EM fungi support long-term C storage by forming extensive, melanin-rich hyphal networks that resist decomposition and by producing hydrophobic compounds that stabilize organic matter (Clemmensen, 2013; Fernandez & Kennedy, 2016). In contrast, AM fungal hyphae decompose more readily, enhancing short-term C retention. However, glomalin-related proteins produced by AM fungi bind soil particles into stable aggregates, improving water retention and resistance to erosion (Rillig et al.; 2002; Wright & Upadhyaya, 1998). This multifunctional cross-complementarity in soil C and nutrient dynamics results in EM-dominated systems typically accumulating more persistent soil C and maintaining long-term fertility, while AM-dominated ecosystems tend to enhance soil structure and drought resistance.

Moreover, dual mycorrhization may offer broader protection against pathogens. It is widely acknowledged that AM fungi are effective in pathogen control and disease resistance in a low-cost, environmentally friendly manner (Dey & Ghosh, 2022). EM fungi also contribute to plant defense against insects or pathogens with mechanisms that share similarities with AM-induced systemic resistance (Dreischhoff et al.; 2020). Although our understanding about how the AM and EM fungi cooperatively modulate plant defense responses remains limited, emerging evidence suggests that shared signaling pathways and gene expression patterns may support functional complementarity in mitigating biotic stress (

Table 1).

Physiological Factors

Physiologically, AM and EM fungi employ distinct colonization strategies that complement each other in their soil exploration capabilities. AM fungi penetrate root cortical cells to form intracellular arbuscules and vesicles while extending thin hyphae into the rhizosphere, creating a localized network for nutrient acquisition (Brundrett, 2002; Smith & Read, 2008). In contrast, EM fungi develop a dense hyphal mantle around root tips and a Hartig net between root cells, producing robust extramatrical hyphae and rhizomorphs that explore a greater soil volume (Agerer, 1991). These structural differences support their functional complementarity, with EM fungi optimizing surface organic soil exploration, while AM fungi are more effective in accessing deeper, mineral soil layers (Neville et al.; 2002).

Additionally, as mentioned above, EM and AM trees differentially influence soil nutrient cycling through distinct functional strategies (Lin et al.; 2017; Midgley & Phillips, 2014). EM fungi secrete proteases and chitinases to access N in organic compounds, while AM fungi primarily enhance inorganic N cycling (Lin et al.; 2017). This functional divergence extends to enzyme investments: EM fungi preferentially produce N-acquiring enzymes, whereas AM fungi allocate more resources to phosphatases (Chen et al.; 2023; Yang et al.; 2022). Therefore, their differential utilization of organic and inorganic N and P sources via enzyme release facilitates niche partitioning, complementarity and species coexistence in diverse forests (Liu et al.; 2018; Chen et al.; 2023).

Finally, AM and EM fungi may synergistically enhance the drought tolerance in dual-mycorrhizal associations through complementary mechanisms. AM fungi improve root hydraulic conductivity by regulating aquaporin expression (Cheng et al.; 2020), whereas EM fungi alleviate water stress through hydrophobic mycelia and rhizomorphs (Castaño et al.; 2023). These cooperative traits highlight the ecological advantage of dual mycorrhization in harsh environments.

The Idiosyncratic Pattern of AM and EM Interaction

In the above two sections, we describe that mycorrhizal symbiosis mediates competition and complementarity in plant growth. Here, we will propose an alternative view. A good knowledge of mechanisms underpinning these processes can facilitate the understanding of plant species distribution, as well as prediction of shifts in mycorrhizal types and plant productivity under environmental changes. In fact, there are many abiotic and biotic factors affecting the interactions between AM and EM fungi. Environmental stress such as low soil moisture, more than host genetics, could be a major determinant of mycorrhizal colonization in dually colonized plants (Gehring et al.; 2006; Teste et al.; 2020). Moreover, mycorrhizal type, the initial plant seed size, and the ratio of available nutrients, can affect how AM and EM fungi interact with their host plants, especially during early growth of tree seedlings (Holste et al.; 2017). Apart from those factors, temperature (Kilpeläinen et al.; 2020), soil physicochemical parameters (Bakker et al.; 2000; Becerra et al.; 2005), host-specific soil microbiome conditioning and nutrient availability (Van Nuland et al.; 2023) can interactively affect the interaction between AM and EM fungi. In this section, we investigated how these abiotic factors influence the growth/productivity of plants with dual mycorrhization or communities with a mixture of AM and EM tree species by synthesizing published studies via meta-data analysis.

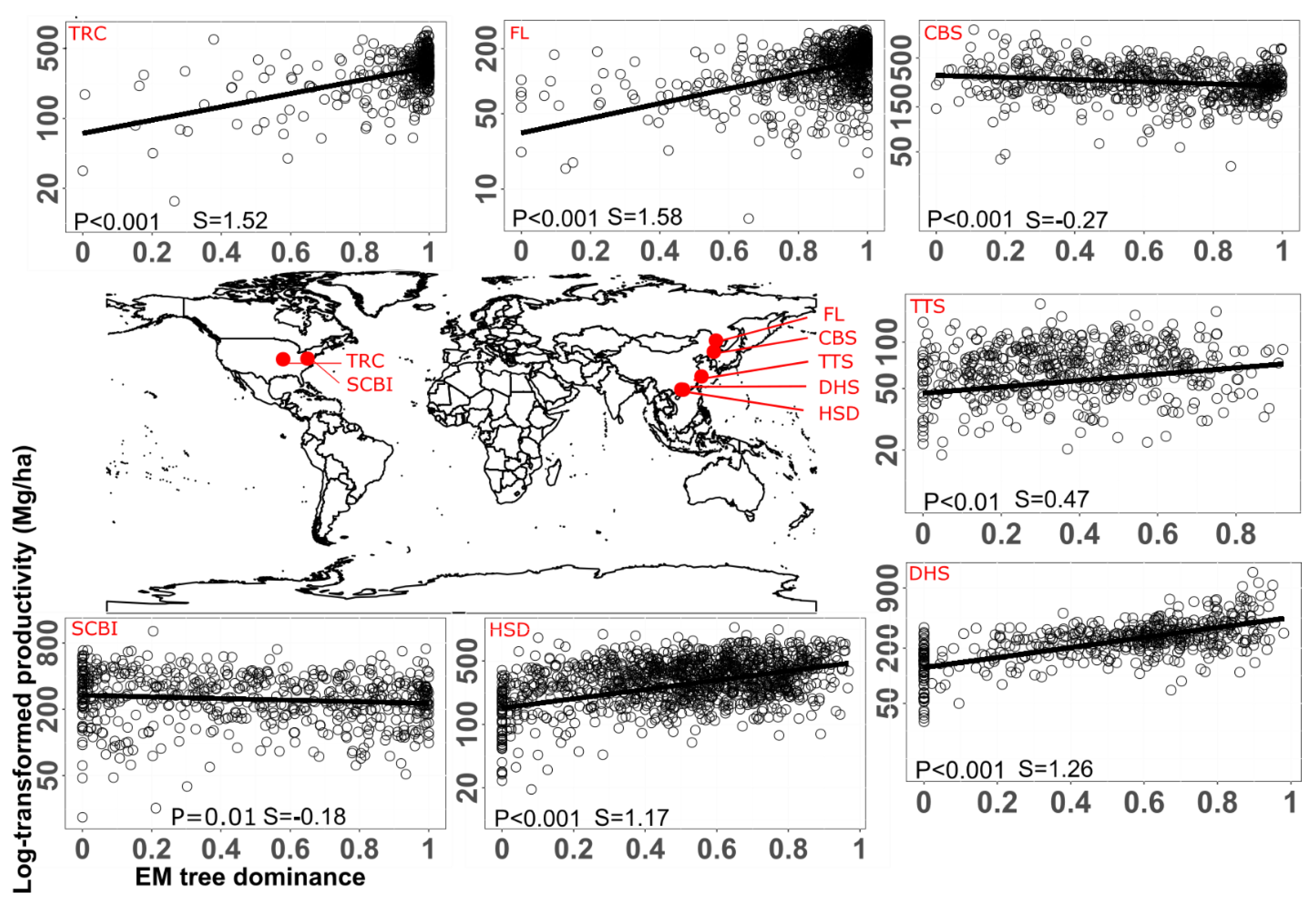

Mostly, AM fungi dominate in warm, P-limited, and disturbed ecosystems, such as croplands, grasslands, and tropics, due to their efficiency in P uptake and drought resistance, thereby supporting high crop yields, while EM fungi thrive in cold, N-limited, and stable environments, such as boreal and temperate forests, by enhancing organic N acquisition and carbon storage, thus sustaining long-term tree growth (Soudzilovskaia et al.; 2019; Steidinger et al.; 2019). Therefore, spatial distribution of AM and EM fungi strongly influences their prevalence at the biome scale. Specifically, the spatial distribution of AM and EM fungi is strongly influenced by environmental conditions, host plant composition, and soil properties (Brundrett, 2009; Steidinger et al.; 2019; Tedersoo et al.; 2014). These factors, in turn, shape plant productivity and nutrient cycling by control of decomposition (Steidinger et al.; 2019). To investigate the effect of spatial distribution on productivity of mycorrhizal plants, we analyzed the relationship between EM dominance and plant productivity in seven forests from the subtropical and temperate biomes (

Figure 2). Plant productivity generally showed a linearly positive relationship with EM tree dominance in five out of seven forests (

Figure 2). However, in two forests (CBS and SCBI), plant productivity exhibited a negative relationship with EM tree dominance. The spatial location of these two forests may have contributed to the differences observed among the other five forests in the EM dominance-productivity relationship, perhaps due to site-specific environmental conditions, soil properties, or microclimatic factors. As for which factor or parameter from these two locations contributes to the difference, it deserves further study in the future.

Figure 2.

The impact of site location on the linear relationship between EM tree dominance level and aboveground biomass (AGB) at different forest stands. EM tree dominance was quantified using the proportion of EM tree AGB in each quadrat. The abbreviations of the seven forest plots (CBS, Changbaishan; DHS, Dinghushan; FL, Fenglin; HSD, Heishiding; SCBI, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute; TRC, Tyson Research Center; TTS, Tiantongshan) are consistent with the original article (Mao et al.; 2023). The lines show the fitted linear models using generalized least-squares methods. The slope (S) and p-value of fitted models are presented. Each black circle represents the information of AGB and EM dominance in each quadrat (20 × 20 m2). Data were extracted from Mao et al. (2023), among which plants were growing in open conditions.

Figure 2.

The impact of site location on the linear relationship between EM tree dominance level and aboveground biomass (AGB) at different forest stands. EM tree dominance was quantified using the proportion of EM tree AGB in each quadrat. The abbreviations of the seven forest plots (CBS, Changbaishan; DHS, Dinghushan; FL, Fenglin; HSD, Heishiding; SCBI, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute; TRC, Tyson Research Center; TTS, Tiantongshan) are consistent with the original article (Mao et al.; 2023). The lines show the fitted linear models using generalized least-squares methods. The slope (S) and p-value of fitted models are presented. Each black circle represents the information of AGB and EM dominance in each quadrat (20 × 20 m2). Data were extracted from Mao et al. (2023), among which plants were growing in open conditions.

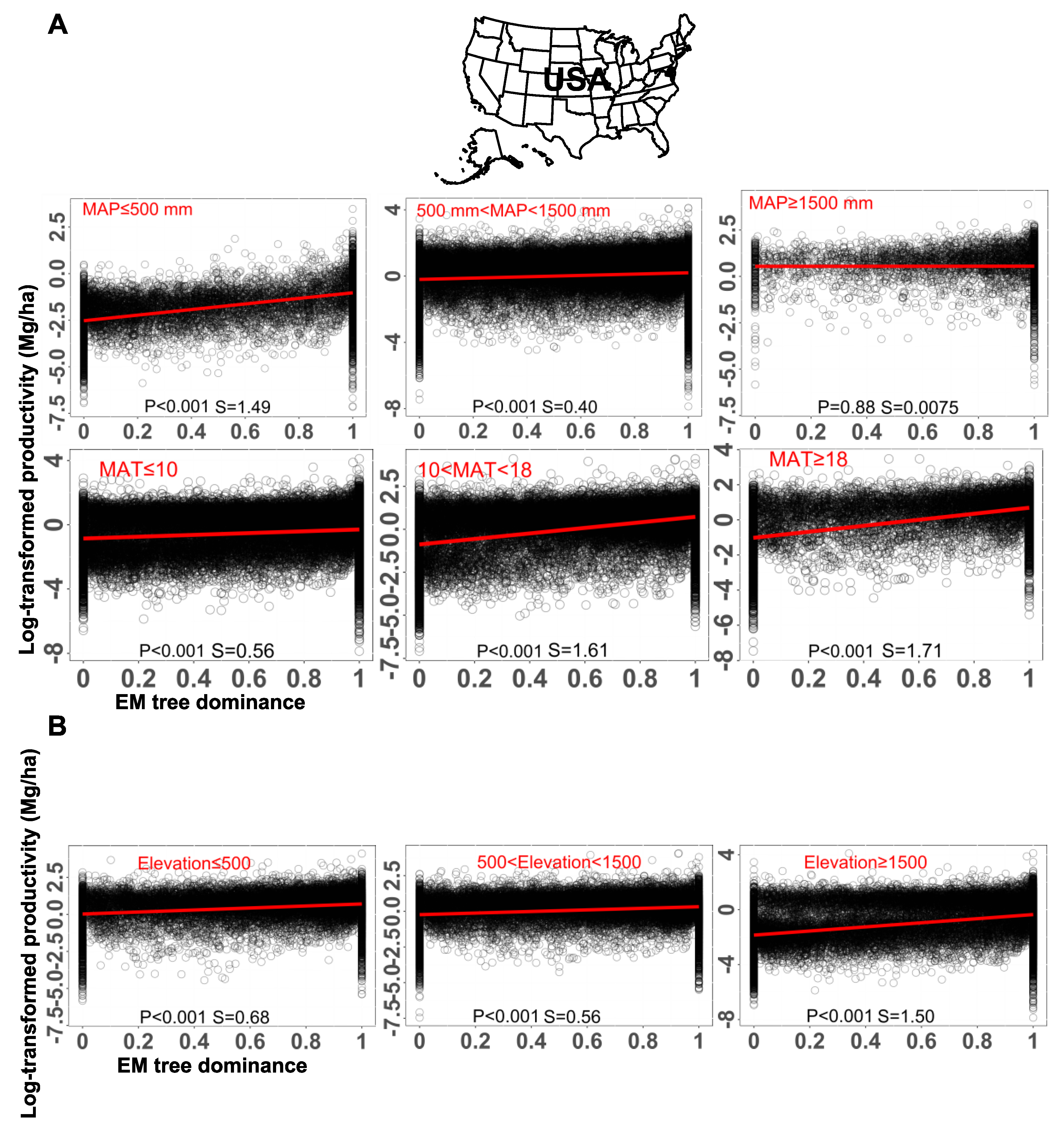

Climate is another factor that affects plant productivity. Moderate temperature and precipitation ensure good growth conditions for plants and mycorrhizal fungi. According to the classification of biomes by NASA, we defined the climate at three MAP levels in this article. Under drought conditions (MAP ≤ 500 mm), plant productivity significantly increased with increasing EM tree dominance, the effect of which was stronger than that in the moderate conditions (500 mm < MAP < 1500 mm); however, in high rainfall area (MAP ≥ 1500 mm), EM dominance did not show significant effects on plant productivity (

Figure 3A). This might be due to the reason that the dual hosts prefer to colonize drier areas which provide the lower MAP for dual hosts, compared to single host species (Rog et al.; 2025). In these mixed forests, plant productivity was positively related to EM tree dominance across MAT gradients, with the relationship being stronger at higher MAT (

Figure 3A). However, under controlled conditions, those relationships are not always the same case. For example, plant biomass, improved with increasing temperature, but not along with colonization rate of EM fungi (

Figure S1A). Additionally, along with the EM dominance level in a mixed forest, it shows a turbulent trend of the tree survival rate to the third year at both ambient and throughfall reduction conditions (

Figure S1B). These findings suggest that there might be potential interacting effects between temperature/precipitation and other unidentified factors. This also implies that the consequence of the coexistence of AM-EM symbiosis is context-dependent.

Additionally, altitudes are characterized by differentiated temperatures, precipitation, solar radiation and atmospheric pollution deposition. Therefore, altitude gradients are essentially expressed by climatic variances. At three elevation levels, the forest productivity maintained a positive relation with the EM dominance level, and even this positive relationship was stronger at the high elevation level (

Figure 3B). However, as shown from a study with an individual plant species, elevation did have an effect on the EM colonization level and tree heights (

Figure S1C). Overall, climate indeed exerts a certain effect on the plant productivity, but not necessarily dependent on EM dominance level.

Figure 3.

The impact of climate on the relationship between EM dominance level and plant biomass. (A) The lines show the fitted general linear models with mean annual precipitation (MAP) and mean annual temperature (MAT) as explanatory variables, respectively. For the variable of MAP, we analyzed the data at three levels, below 500 mm, between 500 and 1500 mm, and above 1500 mm. For the variable of MAT, we analyzed the data at three levels, below 10 °C, between 10 and 18 °C, and above 18 °C. (B) The lines show the fitted general linear models with elevation as the explanatory variable. We analyzed the data at three levels, below 500 m, between 500 and 1500 m, and above 1500 m. In both (A) and (B), EM tree dominance is quantified as EM proportion based on tree basal area. Each black circle represents the data of one forest plot. The slope (S) and p-value of fitted models are presented. Data were extracted from Luo et al. (2023), among which plants were growing in open conditions.

Figure 3.

The impact of climate on the relationship between EM dominance level and plant biomass. (A) The lines show the fitted general linear models with mean annual precipitation (MAP) and mean annual temperature (MAT) as explanatory variables, respectively. For the variable of MAP, we analyzed the data at three levels, below 500 mm, between 500 and 1500 mm, and above 1500 mm. For the variable of MAT, we analyzed the data at three levels, below 10 °C, between 10 and 18 °C, and above 18 °C. (B) The lines show the fitted general linear models with elevation as the explanatory variable. We analyzed the data at three levels, below 500 m, between 500 and 1500 m, and above 1500 m. In both (A) and (B), EM tree dominance is quantified as EM proportion based on tree basal area. Each black circle represents the data of one forest plot. The slope (S) and p-value of fitted models are presented. Data were extracted from Luo et al. (2023), among which plants were growing in open conditions.

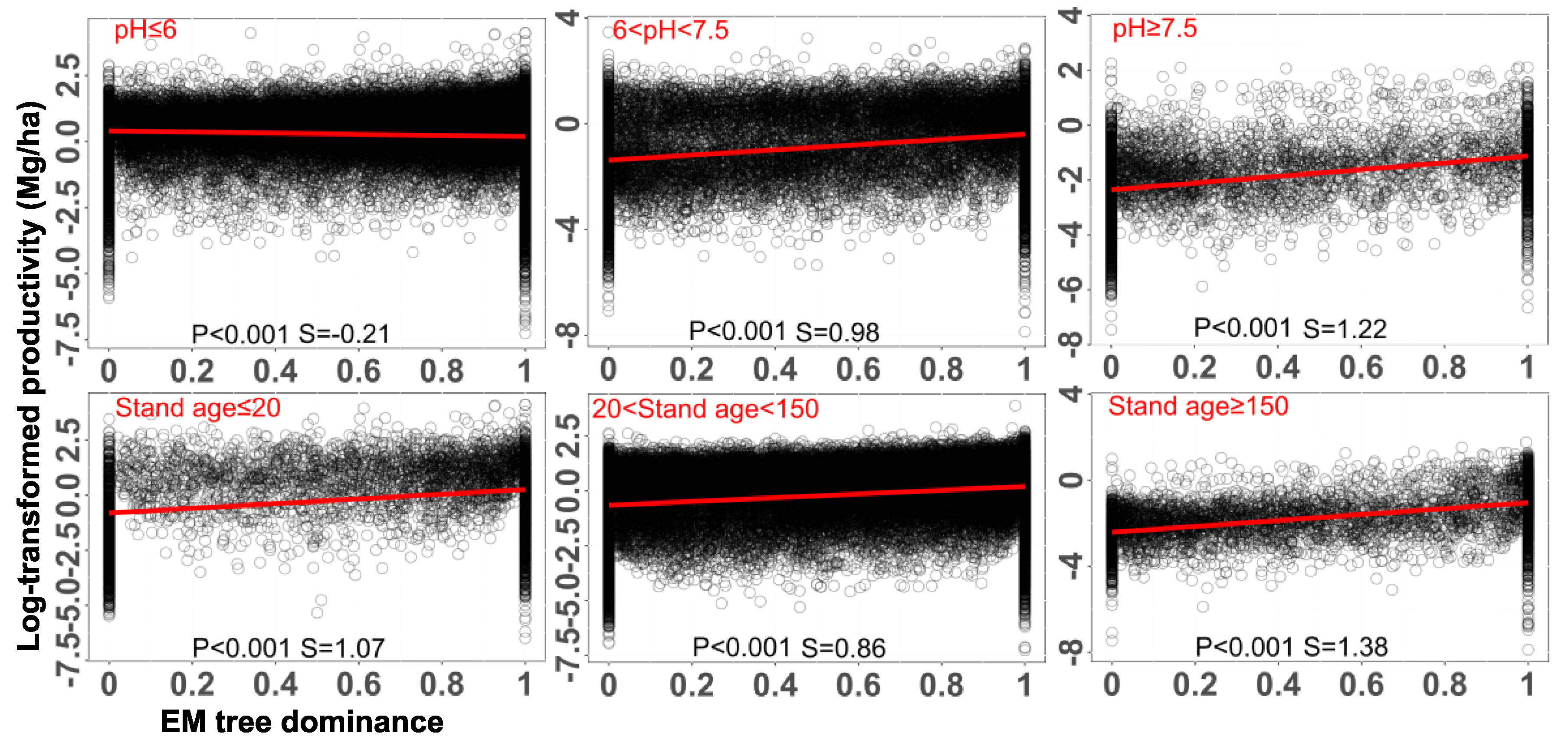

Physicochemical properties of soils, such as pH, soil type, and nutrient availability, play a critical role in shaping the productivity and relative performance of plants associated with EM and AM symbioses (Read, 1991; Steidinger et al.; 2019; Terrer et al.; 2019). We found a negative relationship between EM dominance level and plant productivity in acidic soils, whereas there was an opposite relationship between them in neutral and alkaline conditions (

Figure 4). Additionally, soil age can contribute to the successional dynamics of mycorrhizal associations, with EM trees frequently dominating in older or more mature forest stands where organic nutrient sources are more prevalent (Albornoz, et al.; 2016ab). In view of our analysis, we found that soil age exhibited a positive correlation with plant biomass in mixed forests along with the EM dominance level, but not in controlled conditions (

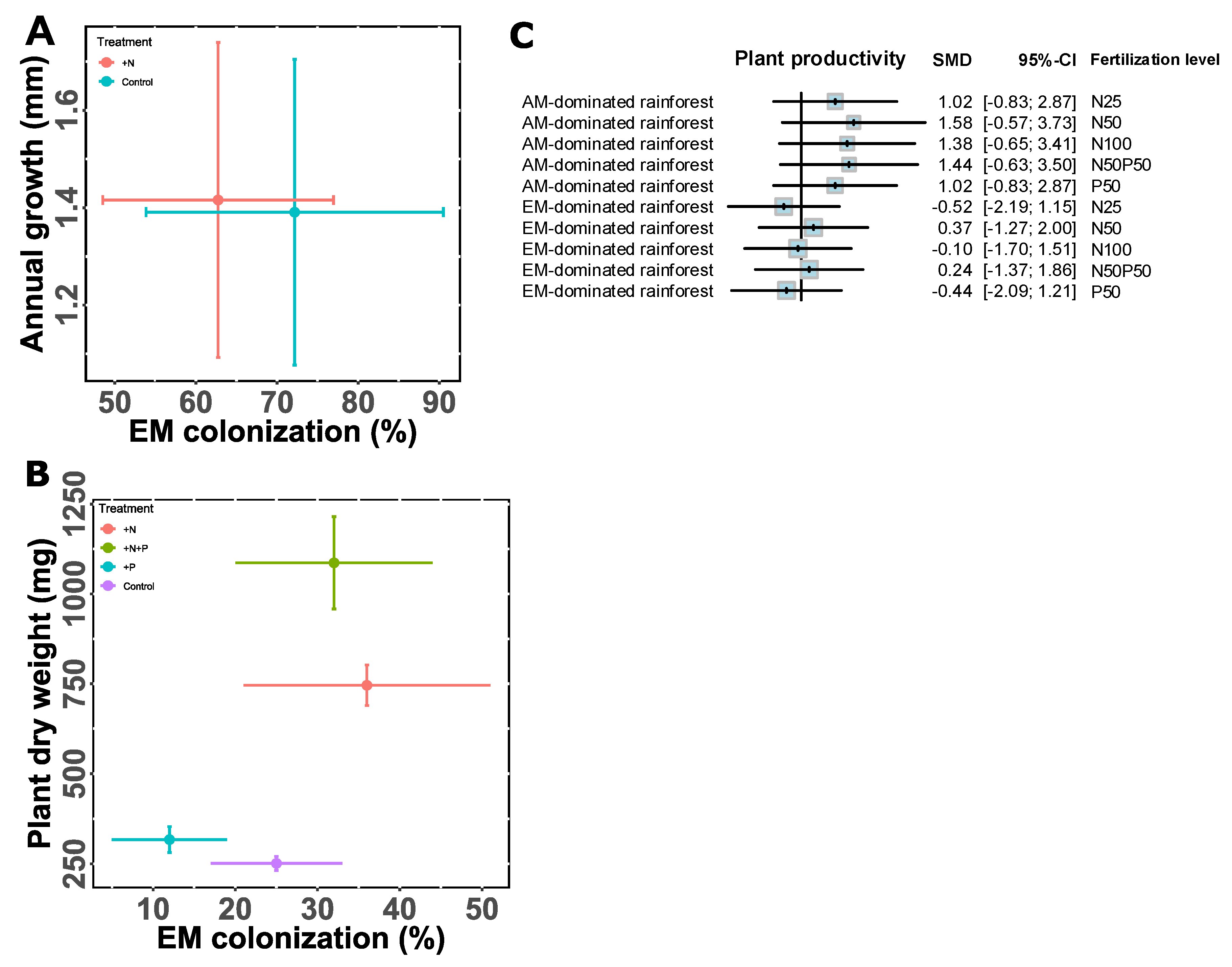

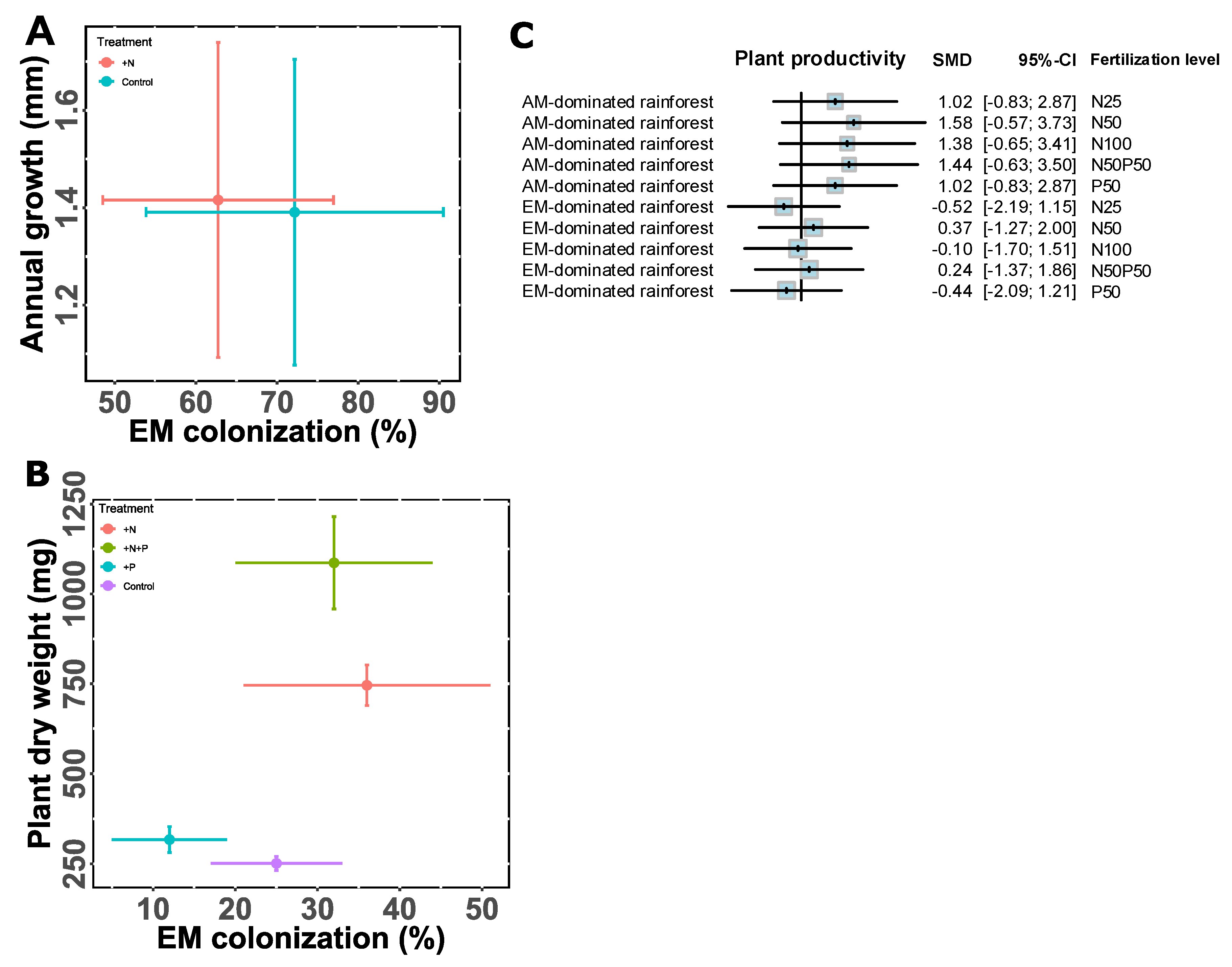

Figure S2). Moreover, fertilization, especially nitrogen or phosphorus addition, can shift the balance between EM and AM trees, sometimes reducing the need for mycorrhizal assistance and altering competitive dynamics among host species (Kuyper & Suz, 2023). For instance, it has been shown that high nitrogen availability can suppress EM colonization more strongly than AM, potentially giving AM-associated species a competitive advantage in nutrient-enriched environments (Teste et al.; 2020). Conversely, phosphorus addition may reduce the dependency of AM plants on their fungal partners, altering their growth response and community dynamics (Miao et al.; 2023). These shifts highlight the roles of soil nutrient availability in determining the ecological roles and relative success of different mycorrhizal strategies. However, we found that fertilization did not show a strong effect on the productivity of mixed forests but increased the biomass of dual-mycorrhizal tree seedlings when grown in pots (

Figure 5). Additionally, fertilization did not show significant effect on the EM colonization rates (

Figure 5AB). Overall, soil physicochemical properties affect the coexistence of two types of mycorrhizal symbiosis and plant performance.

Figure 4.

The impact of soil characteristics on the relationship between EM dominance level and plant biomass along gradients of soil pH or stand age. EM tree dominance is quantified as EM proportion based on tree basal area. Each black circle represents the data of one forest plot. The lines show the fitted general linear models with soil pH or stand age as explanatory variables. We split forest plots into three groups based on soil pH: forests in the acidic soil (pH ≤ 6), forests in the neutral soil (6 < pH < 7.5), and forests in the alkaline soil (pH ≥ 7.5). We also split forest plots into three groups based on stand age: stand age ≤20 years, 20 years < stand age < 150 years, and stand age ≥ 150 years. The p-value and slope (S) of fitted models are presented. Data were extracted from Luo et al. (2023), among which plants were growing in open conditions.

Figure 4.

The impact of soil characteristics on the relationship between EM dominance level and plant biomass along gradients of soil pH or stand age. EM tree dominance is quantified as EM proportion based on tree basal area. Each black circle represents the data of one forest plot. The lines show the fitted general linear models with soil pH or stand age as explanatory variables. We split forest plots into three groups based on soil pH: forests in the acidic soil (pH ≤ 6), forests in the neutral soil (6 < pH < 7.5), and forests in the alkaline soil (pH ≥ 7.5). We also split forest plots into three groups based on stand age: stand age ≤20 years, 20 years < stand age < 150 years, and stand age ≥ 150 years. The p-value and slope (S) of fitted models are presented. Data were extracted from Luo et al. (2023), among which plants were growing in open conditions.

Figure 5.

The impact of fertilization on the relationship between EM dominance level and plant productivity. (A) EM colonization is quantified as the percent of live root tips colonized by EM fungi. We considered mean annual stem radial growth as a proxy of plant C resources (n ≥12, means ± SD). There are two fertilization levels, namely control and N addition. Data were extracted from Karst et al. (2021), among which plants were growing in open conditions. (B) EM colonization is quantified as the percent of root segments with EM fungi divided by the total number of root segments observed (n =8, means ± SE). There are 4 fertilization treatments, including control, with N addition, with P addition, and N plus P addition. Data were extracted from Sasaki et al. (2001), among which plants were growing in pots. (C) The standardized effect size of fertilization level on plant productivity at different EM dominance levels. There are 6 fertilization levels – control (no fertilizer addition), low N addition (N25), medium N addition (N50), high N addition (N100), P addition (P50), with N and P addition (N50P50). Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The size of each blue square indicates biological replicates in relation to the overall mean difference. Vertical solid lines show Hedges = 0. The effect is not significant when the 95% CI includes zero. Data (n =3, means ± SD) were extracted from Yu et al. (2023), among which plants were growing in open conditions.

Figure 5.

The impact of fertilization on the relationship between EM dominance level and plant productivity. (A) EM colonization is quantified as the percent of live root tips colonized by EM fungi. We considered mean annual stem radial growth as a proxy of plant C resources (n ≥12, means ± SD). There are two fertilization levels, namely control and N addition. Data were extracted from Karst et al. (2021), among which plants were growing in open conditions. (B) EM colonization is quantified as the percent of root segments with EM fungi divided by the total number of root segments observed (n =8, means ± SE). There are 4 fertilization treatments, including control, with N addition, with P addition, and N plus P addition. Data were extracted from Sasaki et al. (2001), among which plants were growing in pots. (C) The standardized effect size of fertilization level on plant productivity at different EM dominance levels. There are 6 fertilization levels – control (no fertilizer addition), low N addition (N25), medium N addition (N50), high N addition (N100), P addition (P50), with N and P addition (N50P50). Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The size of each blue square indicates biological replicates in relation to the overall mean difference. Vertical solid lines show Hedges = 0. The effect is not significant when the 95% CI includes zero. Data (n =3, means ± SD) were extracted from Yu et al. (2023), among which plants were growing in open conditions.

Molecular Mechanisms of the Coexistence of AM and EM Symbiosis

There are many molecular factors which might mediate the coexistence of AM and EM symbiosis. First, the enhanced carboxylates, secretion of protons, nutrient-mobilizing enzymes and other unidentified pathways produced by hyphae in the rhizosphere, affect shoot nutrient contents in plants (Gerke, 2015; Kariman et al.; 2014). Moreover, AM- and EM-associated plants share nutrients through common mycorrhizal networks (CMNs; He et al.; 2003). Within CMNs, signalling molecules such as lipochitooligosaccharides (LCOs) and MiSSPs, promote the fungal colonization and symbiosis in AM and EM (

Table 1). As shown, when both fungi interact with host plants, cross-signaling mechanisms regulate their coexistence (Genre et al.; 2020). This implies that many common molecules or signals probably regulate AM and EM symbiosis, providing a molecular basis for the relationship between the two types of mycorrhizae (

Table 1). For instance, auxins (IAAs), cytokinins (CKs) and LCOs, promote EM and AM colonization by stimulating root branching and hyphal growth (Boivin et al.; 2016; Cope et al.; 2019).

AM and EM fungi rely on some symbiosis genes, which often overlap with genes involved in plant immune signalling. First of all, in the case of a single mycorrhizal species, the plant partner choice in EM fungi could be controlled through the upregulation of defense-related genes, restricting fungi that provide fewer nutrients (Hortal et al.; 2017). Moreover, EM fungi suppress plant defense through the symbiotic effectors known as MiSSPs, allowing them to maintain dominance in certain environments (Plett et al.; 2014; 2020). Similarly, AM fungi counteract the plant immune program by an effector SP7 which contributes to the development of the biotrophic status of AM fungi in roots (Kloppholz et al.; 2011). In addition, phytohormones such as jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), gibberellin (GA) , abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene (ET), are widely involved in both AM and EM symbiosis (Basso et al.; 2020; Plett, et al.; 2014), as well as regulating the plant immune system through signaling crosstalk (Checker et al.; 2018). Specifically, jasmonate ZIM-domain (JAZs) proteins act as repressors in JA-related defense response pathways and are also involved in both AM and EM symbiosis in many plant species (Campo & San Segundo, 2020; Daguerre et al.; 2020; Jiang et al.; 2021; Lin et al.; 2021; Plett, Daguerre, et al.; 2014). Similarly, MYC2 acts as a central and positive transcription factor in the JA-mediated defense network and is also regulated in both AM and EM symbiotic pathways (Adolfsson et al.; 2017; Jiang et al.; 2021; Marqués-Gálvez et al.; 2024).

Besides the above mentioned regulators, the coexistence of AM and EM symbiosis might be driven by some conserved nutrient transporters. For example, the ZRT, IRT-like protein (ZIP) family plays a key role in maintaining the homeostasis of zinc (Zn) and iron (Fe) in a variety of plants (Shuting et al.; 2022). In Medicago truncatula, MtZIP14, involved in plant Zn nutrition, is linked to AM colonization, while HcZnT2 in EM fungi was found to act as an extremely remarkable candidate transporter in Zn homeostasis and regulation (Ho-Plágaro et al.; 2024; Watts-Williams et al.; 2023). Therefore, cross-kingdom nutrient transporters might mediate the adjustment of plant C resources between the two types of mycorrhizal plants.

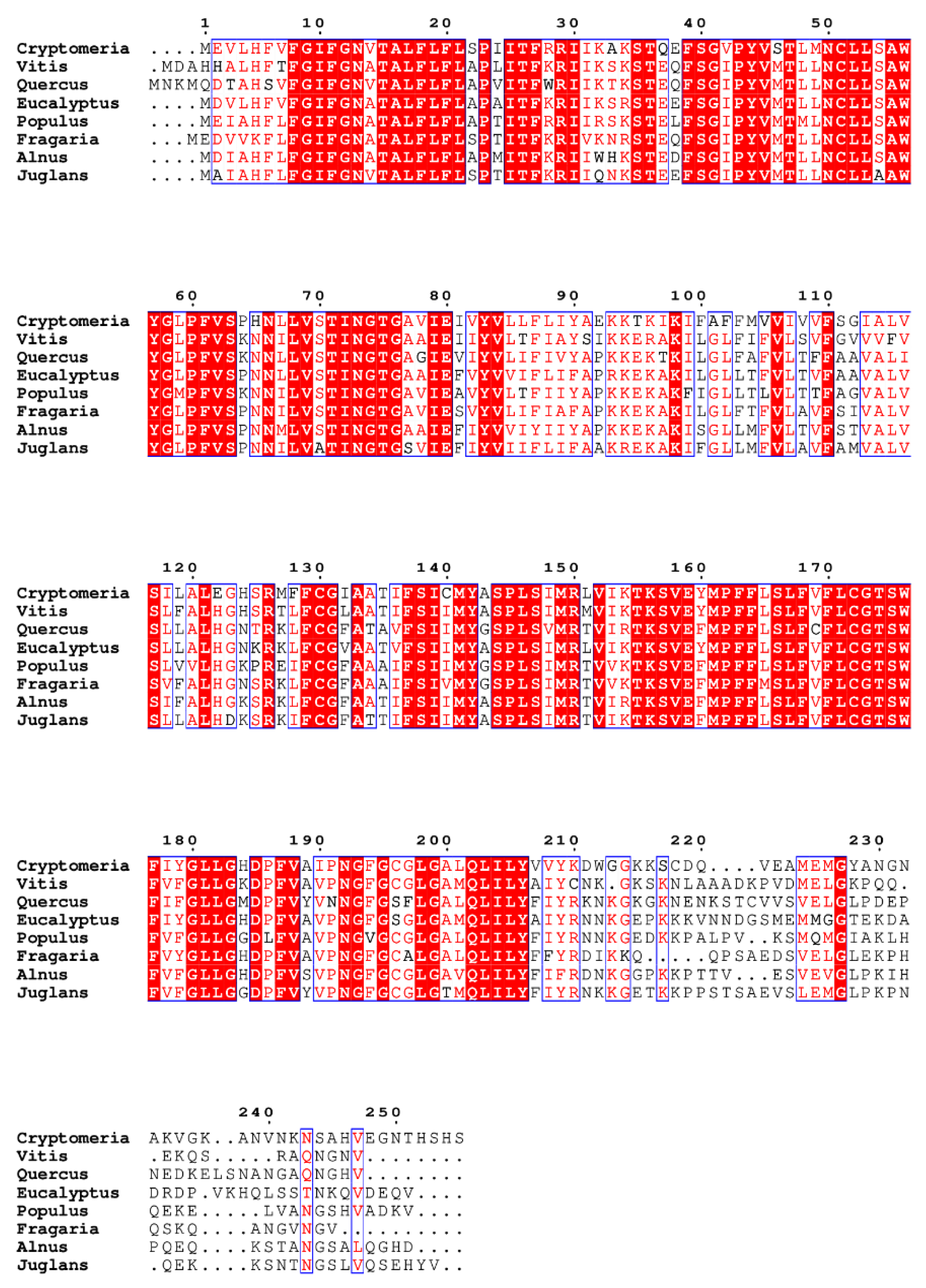

Noteworthy, the poplar SWEET1c glucose transporter plays an important role in ectomycorrhizal symbiosis (Li et al.; 2024); meanwhile, orthologs of SWEET transporters, such as SWEET1b, are also found in AM symbiosis in other plant families (An et al.; 2019;

Figure 6). Furthermore, we found the bidirectional sugar transporters, SWEETs, are conserved in the dual-mycorrhizal plant species from different families by aligning the protein sequences of the SWEETs (

Figure 6). This suggests that the molecular traits functioning in plant C allocation might be key to the survival of dual-mycorrhizal plants in the long-lasting process of evolution.

Table 1.

List of plant common regulators in AM and EM symbiosis.

Table 1.

List of plant common regulators in AM and EM symbiosis.

| Plant common regulators |

Plant taxa |

Fungus taxa |

Mycorrhizal type |

Effect |

Reference |

| TIFY10b (JAZ protein) |

Musa acuminate Cavendish cv. Brail |

Rhizophagus irregularis |

AM |

Regulatory roles in fungal infection |

Lin et al.; 2021 |

| PtJAZ6 |

Populus trichocarpa |

Laccaria bicolor |

EM |

A co-repressor of JA-signaling |

Daguerre et al.; 2020; Plett et al.; 2014 |

| MYC2 |

Medicago truncatula |

Rhizophagus irregularis |

AM |

The master regulator of JA responses |

Adolfsson et al.; 2017 |

| MYC2 |

Populus |

Laccaria bicolor |

EM |

Controlling root fungal colonization |

Marqués-Gálvez et al.; 2024 |

| SP7 |

Medicago truncatula |

Glomus intraradices |

AM |

Promoting symbiotic biotrophy |

Kloppholz et al.; 2011 |

| MiSSP7 |

Populus tremula × alba |

Laccaria bicolor |

EM |

Promoting colonization |

Plett et al.; 2011 |

| IAA, abscisic acid (ABA), JA, SA, CK |

Olea europaea |

Rhizophagus irregularis |

AM |

Water deficit tolerance |

Tekaya et al.; 2022 |

| JA, ET |

Populus |

Laccaria bicolor |

EM |

Negative modulators |

Plett et al.; 2014 |

| ABA, JA |

Camellia sinensis |

Glomus etunicatum |

AM |

Enhancing plant stress resistance and increasing nutrient uptake |

Sun et al.; 2020 |

| JA, SA, GA, ET |

Populus tremula × alba |

Laccaria bicolor |

EM |

Multifaceted roles in EM development |

Basso et al.; 2020 |

| LCOs |

Medicago truncatula |

Glomus intraradices |

AM |

Facilitating symbiosis |

Maillet et al.; 2011 |

| LCOs |

Populus |

Laccaria bicolor |

EM |

Enhancing the colonization |

Cope et al.; 2019 |

| Sesquiterpenes |

Lotus japonicus |

Gigaspora margarita |

AM |

Inducing hyphal branching |

Akiyama et al.; 2005 |

| Sesquiterpenes |

Eucalyptus grandis |

Pisolithus microcarpus |

EM |

Altering root growth; promoting host colonization |

Plett et al.; 2024 |

| SWEET1b |

Medicago truncatula |

Rhizophagus irregularis |

AM |

Maintaining arbuscules for a healthy mutually beneficial symbiosis |

An et al.; 2019 |

| SWEET1c |

Populus tremula × alba |

Laccaria bicolor |

EM |

Facilitating glucose and sucrose

transport |

Li et al.; 2024 |

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Taken together, this study offers a novel perspective on the relationship between mycorrhizal associations and plant productivity at multiple scales. Although quantitative global data on the effects of mycorrhizal associations on ecosystem services are increasing, substantial variability remains. Globally, predictive models often fall short in accurately estimating plant productivity due to the confounding effects of environmental variables, such as location, MAT, MAP, soil pH, soil age, and fertilization. These factors introduce considerable uncertainty, resulting in idiosyncratic patterns of vegetation productivity. Incorporating these environmental variables into vegetation productivity models may provide a robust framework for testing hypotheses concerning the impacts of mycorrhizal associations on ecosystem functioning and the provision of related ecosystem services. Furthermore, establishing reliable fine-scale models linking EM colonization or dominance levels with plant productivity could enable more precise assessments of ecosystem services. At the molecular level, predictive metabolomics can identify metabolic markers associated with plant resilience to global change, thereby enabling forecasts of future adaptive trends. At the physiological level, differences in carbon allocation, root structure, and enzyme production between AM and EM fungi mediate competitive and complementary interactions that directly influence plant growth and nutrient acquisition. At the ecological level, the spatial distribution of mycorrhizal types, soil properties, and climatic factors shape plant community composition, productivity patterns, and nutrient cycling, highlighting the context-dependent nature of mycorrhizal effects across ecosystems. This multi-factorial, multi-scale set of drivers likely explains the high variability observed in plant productivity and the context-dependent outcomes of mycorrhizal associations across ecosystems. Understanding these interactions can inform more accurate predictive models and guide management strategies that optimize environmental conditions and fungal community structure. Finally, strategic management of mycorrhizal associations offers a means to manage plant yield, contributing to more adaptive and sustainable ecosystem based on various environmental conditions. As such, strategic site allocation that considers the compatibility between plant species and their mycorrhizal partners can optimize fungal community structure, enhancing plant productivity and overall ecosystem health.

In the future, we suggest that forest managers and agricultural practitioners consider integrating multiple factors, such as mycorrhizal type, spatial distribution, soil characteristics, climatic conditions, successional stages, and species composition, into their management strategies. Such integrative approaches could optimize mycorrhizal community structure, thereby enhancing vegetation productivity in forestry and agriculture.

Competing Interests

None declared.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

MZ, NF designed the study. PP, SL, LW contributed to the data interpretation. MZ performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first version of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the final version.

Data availability statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

All authors acknowledge funding support from the French government in the framework of the IdEX Bordeaux University “Investments for the Future” program / GPR Bordeaux Plant Science.

References

- Adolfsson, L.; Nziengui, H.; Abreu, I.N.; Šimura, J.; Beebo, A.; Herdean, A.; Aboalizadeh, J.; Široká, J.; Moritz, T.; Novák, O.; et al. Enhanced secondary- and hormone metabolism in leaves of arbuscular mycorrhizal medicago truncatula. Plant Physiology 2017, 175, 392–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agerer, R. 2 Characterization of Ectomycorrhiza. In Techniques for the Study of Mycorrhiza; Norris, J. R., Read, D.J., Varma, A. K., Eds.; Academic Press, 1991; Volume 23, pp. 25–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, K.; Matsuzaki, K.I.; Hayashi, H. Plant sesquiterpenes induce hyphal branching in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Nature 2005, 435, 824–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, F.E.; Lambers, H.; Turner, B.L.; Teste, F.P.; Laliberté, E. Shifts in symbiotic associations in plants capable of forming multiple root symbioses across a long-term soil chronosequence. Ecology and Evolution 2016a, 6, 2368–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, F.E.; Teste, F.P.; Lambers, H.; Bunce, M.; Murray, D.C.; White, N.E.; Laliberté, E. Changes in ectomycorrhizal fungal community composition and declining diversity along a 2-million-year soil chronosequence. Molecular Ecology 2016b, 25, 4919–4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Zeng, T.; Ji, C.; de Graaf, S.; Zheng, Z.; Xiao, T.T.; Deng, X.; Xiao, S.; Bisseling, T.; Limpens, E.; Pan, Z. A Medicago truncatula SWEET transporter implicated in arbuscule maintenance during arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. New Phytologist 2019, 224, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, M.A.; Crowther, T.W.; van der Linde, S.; Suz, L.M.; Bidartondo, M.I.; Cox, F.; Schaub, M.; Rautio, P.; Ferretti, M.; Vesterdal, L.; et al. Forest tree growth is linked to mycorrhizal fungal composition and function across Europe. ISME Journal 2022, 16, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizoglu, U.; Argentel-Martínez, L.; Peñuelas-Rubio, O.; Meriño-Hernández, Y.; Rodríguez-Yon, Y.; Dell Amico-Rodríguez, J.M.; González-Aguilera, J.; Shin, J.H. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus irregularis enhances antioxidant system mechanisms in chickpea plants under saline conditions. Plant Growth Regulation 2025, 105, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduzzi, S.; Rücker, G.; Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. 2019, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, M.R.; Garbaye, J.; Nys, C. Effect of liming on the ectomycorrhizal status of oak. Forest Ecology and Management 2000, 126, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, V.; Kohler, A.; Miyauchi, S.; Singan, V.; Guinet, F.; Šimura, J.; Novák, O.; Barry, K.W.; Amirebrahimi, M.; Block, J.; et al. An ectomycorrhizal fungus alters sensitivity to jasmonate, salicylate, gibberellin, and ethylene in host roots. Plant Cell and Environment 2020, 43, 1047–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, A.; Zak, M.R.; Horton, T.R.; Micolini, J. Ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization of Alnus acuminata from Calilegua National Park (Argentina). Mycorrhiza 2005, 15, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Akhtar, K.; Ahanger, M.A.; Iqbal, M.; Wang, P.; Mustafa, N.S.; Zhang, L. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improve growth, essential oil, secondary metabolism, and yield of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) under drought stress conditions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 45276–45295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdellah, K.; Azcón-Aguilar, C.; Valderas, A.; Speziga, D.; Fitzpatrick, T.B.; Ferrol, N. GintPDX1 encodes a protein involved in vitamin B6 biosynthesis that is up-regulated by oxidative stress in the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus intraradices. New Phytologist 2009, 184, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.A.; Maherali, H.; Reinhart, K.O.; Lekberg, Y.; Hart, M.M.; Klironomos, J. Plant-soil feedbacks and mycorrhizal type influence temperate forest population dynamics. Science 2017, 355, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, L.; Carletti, P.; Badeck, F.W.; Rizza, F.; Morcia, C.; Ghizzoni, R.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Terzi, V.; Lucini, L. Metabolomic responses triggered by arbuscular mycorrhiza enhance tolerance to water stress in wheat cultivars. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2019, 137, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, S.; Fonouni-Farde, C.; Frugier, F. How auxin and cytokinin phytohormones modulate root microbe interactions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, M.G. Mycorrhizal networks mediate overstorey-understorey competition in a temperate forest. Ecology Letters 2004, 7, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M. Effect sizes for studies with continuous data. In The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis, 2nd ed.; Cooper, H., Hedges, L.V., Valentine, J.C., Eds.; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 221–252. [Google Scholar]

- Brundrett, M.C. Coevolution of roots and mycorrhizas of land plants. New Phytologist 2002, 154, 275–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brundrett, M.C. Mycorrhizal associations and other means of nutrition of vascular plants: understanding the global diversity of host plants by resolving conflicting information and developing reliable means of diagnosis. Plant and Soil 2009, 320, 37–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, S.; San Segundo, B. Systemic induction of phosphatidylinositol-based signaling in leaves of arbuscular mycorrhizal rice plants. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, C.; Suarez-vidal, E.; Zas, R.; Bonet, Jose Antonio; Oliva, J.; Sampedro, L. Ectomycorrhizal fungi with hydrophobic mycelia and rhizomorphs dominate in young pine trees surviving experimental drought stress. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2023, 178, 108932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, R.; Chakraborty, A.; Rahaman, F.; Sarkar, T.; Dey, S.; Das, M. Mycorrhization in trees: ecology, physiology, emerging technologies and beyond. Plant Biology 2024, 26, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checker, V.G.; Kushwaha, H.R.; Kumari, P.; Yadav, S. Role of Phytohormones in Plant Defense: Signaling and Cross Talk BT - Molecular Aspects of Plant-Pathogen Interaction; Singh, A., Singh, I. K., Eds.; Springer Singapore, 2018; pp. 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Brundrett, M.C.; Dell, B. Effects of ectomycorrhizas and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizas, alone or in competition, on root colonization and growth of Eucalyptus globulus and E. urophylla. New Phytologist 2000, 146, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, W.; Lang, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Xu, C. Arbuscular mycorrhizal and ectomycorrhizal plants together shape seedling diversity in a subtropical forest. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2023, 6, 1304897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.Q.; Ding, Y.E.; Shu, B.; Zou, Y.N.; Wu, Q.S.; Kuca, K. Plant Aquaporin responses to mycorrhizal symbiosis under abiotic stress. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology 2020, 23, 786–794. [Google Scholar]

- Chilvers, G.A.; Lapeyrie, F.F.; Horan, D.P. Ectomycorrhizal Vs Endomycorrhizal Fungi Within the Same Root System. New Phytologist 1987, 107, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmensen, K.E. Roots and Associated Fungi Drive Long-Term Carbon Sequestration in Boreal Forest. Science 2013, 339, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cope, K.R.; Bascaules, A.; Irving, T.B.; Venkateshwaran, M.; Maeda, J.; Garcia, K.; Rush, T.A.; Ma, C.; Labbé, J.; Jawdy, S.; et al. The ectomycorrhizal fungus laccaria bicolor produces lipochitooligosaccharides and uses the common symbiosis pathway to colonize populus roots. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 2386–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courty, P.E.; Pritsch, K.; Schloter, M.; Hartmann, A.; Garbaye, J. Activity profiling of ectomycorrhiza communities in two forest soils using multiple enzymatic tests. New Phytologist 2005, 167, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daguerre, Y.; Basso, V.; Hartmann-Wittulski, S.; Schellenberger, R.; Meyer, L.; Bailly, J.; Kohler, A.; Plett, J.M.; Martin, F.; Veneault-Fourrey, C. The mutualism effector MiSSP7 of Laccaria bicolor alters the interactions between the poplar JAZ6 protein and its associated proteins. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 20362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.; Ghosh, S. Arbuscular mycorrhizae in plant immunity and crop pathogen control. Rhizosphere 2022, 22, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreischhoff, S.; Das, I.S.; Jakobi, M.; Kasper, K.; Polle, A. Local Responses and Systemic Induced Resistance Mediated by Ectomycorrhizal Fungi. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11, 590063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekblad, A.; Wallander, H.; Näsholm, T. Chitin and ergosterol combined to measure total and living fungal biomass in ectomycorrhizas. New Phytologist 1998, 138, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.W.; Kennedy, P.G. Revisiting the “Gadgil effect”: Do interguild fungal interactions control carbon cycling in forest soils? New Phytologist 2016, 209, 1382–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, N.; Knoblochová, T.; Kohout, P.; Janoušková, M.; Cajthaml, T.; Frouz, J.; Rydlová, J. Asymmetric Interaction Between Two Mycorrhizal Fungal Guilds and Consequences for the Establishment of Their Host Plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 873204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehring, C.A.; Mueller, R.C.; Whitham, T.G. Environmental and genetic effects on the formation of ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal associations in cottonwoods. Oecologia 2006, 149, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genre, A.; Lanfranco, L.; Perotto, S.; Bonfante, P. Unique and common traits in mycorrhizal symbioses. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2020, 18, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, J. The acquisition of phosphate by higher plants: Effect of carboxylate release by the roots. A critical review. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 2015, 178, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Guerrero, M.; Oger, E.; Benabdellah, K.; Azcón-Aguilar, C.; Lanfranco, L.; Ferrol, N. Characterization of a CuZn superoxide dismutase gene in the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus intraradices. Current Genetics 2010, 56, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, H.J.; Cargill, R.I.M.; Van Nuland, M.E.; Hagen, S.C.; Field, K.J.; Sheldrake, M.; Soudzilovskaia, N.A.; Kiers, E.T. Mycorrhizal mycelium as a global carbon pool. Current Biology 2023, 33, 560–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.H.; Critchley, C.; Bledsoe, C. Nitrogen transfer within and between plants through common mycorrhizal networks (CMNs). Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2003, 22, 531–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heklau, H.; Schindler, N.; Buscot, F.; Eisenhauer, N.; Ferlian, O.; Prada Salcedo, L.D.; Bruelheide, H. Mixing tree species associated with arbuscular or ectotrophic mycorrhizae reveals dual mycorrhization and interactive effects on the fungal partners. Ecology and Evolution 2021, 11, 5424–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Plágaro, T.; Usman, M.; Swinnen, J.; Ruytinx, J.; Gosti, F.; Gaillard, I.; Zimmermann, S.D. HcZnT2 is a highly mycorrhiza-induced zinc transporter from Hebeloma cylindrosporum in association with pine. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1466279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, M.N.; Briones, M.J.I.; Keel, S.G.; Metcalfe, D.B.; Campbell, C.; Midwood, A.J.; Thornton, B.; Hurry, V.; Linder, S.; Näsholm, T.; Högberg, P. Quantification of effects of season and nitrogen supply on tree below-ground carbon transfer to ectomycorrhizal fungi and other soil organisms in a boreal pine forest. New Phytologist 2010, 187, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holste, E.K.; Kobe, R.K.; Gehring, C.A. Plant species differ in early seedling growth and tissue nutrient responses to arbuscular and ectomycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza 2017, 27, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortal, S.; Plett, K.L.; Plett, J.M.; Cresswell, T.; Johansen, M.; Pendall, E.; Anderson, I.C. Role of plant-fungal nutrient trading and host control in determining the competitive success of ectomycorrhizal fungi. ISME Journal 2017, 11, 2666–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeeshma, E.; Puthur, J.T. Direct and indirect influence of arbuscular mycorrhizae on enhancing metal tolerance of plants. Archives of Microbiology 2020, 202, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janos, D.P.; Scott, J.; Aristizábal, C.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Arbuscular-Mycorrhizal Networks Inhibit Eucalyptus tetrodonta Seedlings in Rain Forest Soil Microcosms. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Tan, M.; Wu, S.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, G.; Yan, S. Defense responses of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus-colonized poplar seedlings against gypsy moth larvae: a multiomics study. Horticulture Research 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.C.; Wilson, G.W.T.; Bowker, M.A.; Wilson, J.A.; Miller, R.M. Resource limitation is a driver of local adaptation in mycorrhizal symbioses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 2093–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariman, K.; Barker, S.J.; Jost, R.; Finnegan, P.M.; Tibbett, M. A novel plant-fungus symbiosis benefits the host without forming mycorrhizal structures. New Phytologist 2014, 201, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebert, M.; Kostić, S.; Čapelja, E.; Vuksanović, V.; Stojnić, S.; Markić, A.G.; Zlatković, M.; Milović, M.; Galović, V.; Orlović, S. Ectomycorrhizal Fungi Modulate Pedunculate Oak’s Heat Stress Responses through the Alternation of Polyamines, Phenolics, and Osmotica Content. Plants 2022, 11, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpeläinen, J.; Aphalo, P.J.; Lehto, T. Temperature affected the formation of arbuscular mycorrhizas and ectomycorrhizas in Populus angustifolia seedlings more than a mild drought. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2020, 146, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloppholz, S.; Kuhn, H.; Requena, N. A secreted fungal effector of glomus intraradices promotes symbiotic biotrophy. Current Biology 2011, 21, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluber, L.A.; Smith, J.E.; Myrold, D.D. Distinctive fungal and bacterial communities are associated with mats formed by ectomycorrhizal fungi. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2011, 43, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblochová, T.; Kohout, P.; Püschel, D.; Doubková, P.; Frouz, J.; Cajthaml, T.; Kukla, J.; Vosátka, M.; Rydlová, J. Asymmetric response of root-associated fungal communities of an arbuscular mycorrhizal grass and an ectomycorrhizal tree to their coexistence in primary succession. Mycorrhiza 2017, 27, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyper, T.W.; Suz, L.M. Do Ectomycorrhizal Trees Select Ectomycorrhizal Fungi That Enhance Phosphorus Uptake under Nitrogen Enrichment? Forests 2023, 14, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H.; Raven, J.A.; Shaver, G.R.; Smith, S.E. Plant nutrient-acquisition strategies change with soil age. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 2008, 23, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shi, W.; Zhang, P.; Ma, J.; Zou, R.; Zhang, X.; Kohler, A.; Martin, F.M.; Zhang, F. The poplar SWEET1c glucose transporter plays a key role in the ectomycorrhizal symbiosis. New Phytologist 2024, 244, 2518–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Gao, Y.; Han, L.; Chu, H. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi contribute to reactive oxygen species homeostasis of Bombax ceiba L. under drought stress. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 991781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; McCormack, M.L.; Ma, C.; Guo, D. Similar below-ground carbon cycling dynamics but contrasting modes of nitrogen cycling between arbuscular mycorrhizal and ectomycorrhizal forests. New Phytologist 2017, 213, 1440–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Zhang, M.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y. Inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus modulates defense-related genes expression in banana seedlings susceptible to wilt disease. Plant Signaling and Behavior 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, B.D.; Tunlid, A. Ectomycorrhizal fungi - potential organic matter decomposers, yet not saprotrophs. New Phytologist 2015, 205, 1443–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Burslem, D.F.R.P.; Taylor, J.D.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Khoo, E.; Majalap-Lee, N.; Helgason, T.; Johnson, D. Partitioning of soil phosphorus among arbuscular and ectomycorrhizal trees in tropical and subtropical forests. Ecology Letters 2018, 21, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Phillips, R.P.; Jo, I.; Fei, S.; Liang, J.; Schmid, B.; Eisenhauer, N. Higher productivity in forests with mixed mycorrhizal strategies. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Lee, J.; Eusebi, A.; Niewielska, A.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Lopez, R.; Butcher, S. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher sequence analysis tools framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillet, F.; Poinsot, V.; André, O.; Puech-Pagés, V.; Haouy, A.; Gueunier, M.; Cromer, L.; Giraudet, D.; Formey, D.; Niebel, A.; et al. Fungal lipochitooligosaccharide symbiotic signals in arbuscular mycorrhiza. Nature 2011, 469, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; van der Plas, F.; Corrales, A.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.J.; Bourg, N.A.; Chu, C.; Hao, Z.; Jin, G.; Lian, J.; Lin, F.; et al. Scale-dependent diversity–biomass relationships can be driven by tree mycorrhizal association and soil fertility. Ecological Monographs 2023, 93, e1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Wiegand, T.; Corrales, A.; Fang, S.; Hao, Z.; Lin, F.; Ye, J.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, X. Mycorrhizal Types Regulate Tree Spatial Associations in Temperate Forests: Ectomycorrhizal Trees Might Favour Species Coexistence. Ecology Letters 2024, 27, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marqués-Gálvez, J.E.; Pandharikar, G.; Basso, V.; Kohler, A.; Lackus, N.D.; Barry, K.; Keymanesh, K.; Johnson, J.; Singan, V.; Grigoriev, I.V.; et al. Populus MYC2 orchestrates root transcriptional reprogramming of defence pathway to impair Laccaria bicolor ectomycorrhizal development. New Phytologist 2024, 242, 658–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, T.A.; Gehring, C.A. Below-ground interactions with arbuscular mycorrhizal shrubs decrease the performance of pinyon pine and the abundance of its ectomycorrhizas. New Phytologist 2006, 171, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Wang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guo, E.; Li, Y. The Addition of a High Concentration of Phosphorus Reduces the Diversity of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Temperate Agroecosystems. Diversity 2023, 15, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, M.G.; Phillips, R.P. Mycorrhizal associations of dominant trees influence nitrate leaching responses to N deposition. Biogeochemistry 2014, 117, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Maximov, T.C.; Bryanin, S.V.; Kononov, A.; Sugimoto, A. Host phylogeny is the primary determinant of ectomycorrhizal fungal community composition in the permafrost ecosystem of eastern Siberia at a regional scale. Fungal Ecology 2022, 55, 101117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nave, L.E.; Nadelhoffer, K.J.; Le Moine, J.M.; van Diepen, L.T.A.; Cooch, J.K.; Van Dyke, N.J. Nitrogen Uptake by Trees and Mycorrhizal Fungi in a Successional Northern Temperate Forest: Insights from Multiple Isotopic Methods. Ecosystems 2013, 16, 590–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehls, U.; Hampp, R. Carbon allocation in ectomycorrhizas. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2000, 57, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, J.; Tessier, J.L.; Morrison, I.; Scarratt, J.; Canning, B.; Klironomos, J.N. Soil depth distribution of ecto- and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associated with Populus tremuloides within a 3-year-old boreal forest clear-cut. Applied Soil Ecology 2002, 19, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasquive, V.; Brisson, J.; Laliberté, E.; Chagnon, P.L. Arbuscular and ectomycorrhizal tree seedling growth is inhibited by competition from neighboring roots and associated fungal hyphae. Plant and Soil 2025, 507, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasquive, V.; Brisson, J.; Laliberté, E.; Chagnon, P.L. Limited impact of soil inocula from arbuscular and ectomycorrhizal-dominated sites on root morphology and growth of four tree seedling species from a temperate deciduous forest. Plant and Soil 2025b, 511, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellitier, P.T.; Zak, D.R. Ectomycorrhizal fungi and the enzymatic liberation of nitrogen from soil organic matter: why evolutionary history matters. New Phytologist 2018, 217, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.P.; Brzostek, E.; Midgley, M.G. The mycorrhizal-associated nutrient economy: A new framework for predicting carbon-nutrient couplings in temperate forests. New Phytologist 2013, 199, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre-Emmanuel, C.; Karin, P.; Michael, S.; Anton, H.; Jean, G. Activity profiling of ectomycorrhiza communities in two forest soils using multiple enzymatic tests. New Phytologist 2005, 167, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plett, J.M.; Daguerre, Y.; Wittulsky, S.; Vayssier̀es, A.; Deveau, A.; Melton, S.J.; Kohler, A.; Morrell-Falvey, J.L.; Brun, A.; Veneault-Fourrey, C.; Martin, F. Effector MiSSP7 of the mutualistic fungus Laccaria bicolor stabilizes the Populus JAZ6 protein and represses jasmonic acid (JA) responsive genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, 8299–8304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plett, J.M.; Kemppainen, M.; Kale, S.D.; Kohler, A.; Legué, V.; Brun, A.; Tyler, B.M.; Pardo, A.G.; Martin, F. A secreted effector protein of laccaria bicolor is required for symbiosis development. Current Biology 2011, 21, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plett, J.M.; Khachane, A.; Ouassou, M.; Sundberg, B.; Kohler, A.; Martin, F. Ethylene and jasmonic acid act as negative modulators during mutualistic symbiosis between Laccaria bicolor and Populus roots. New Phytologist 2014, 202, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plett, J.M.; Plett, K.L.; Wong-Bajracharya, J.; de Freitas Pereira, M.; Costa, M.D.; Kohler, A.; Martin, F.; Anderson, I.C. Mycorrhizal effector PaMiSSP10b alters polyamine biosynthesis in Eucalyptus root cells and promotes root colonization. New Phytologist 2020, 228, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Software, PBC. RStudio: Integrated development environment for R; Posit Software, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://posit.co/.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Qin, F.; Yu, S. Compatible Mycorrhizal Types Contribute to a Better Design for Mixed Eucalyptus Plantations. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 616726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queralt, M.; Walker, J.K.M.; De Miguel, A.M.; Parladé, J.; Anderson, I.C.; Hortal, S. The ability of a host plant to associate with different symbiotic partners affects ectomycorrhizal functioning. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2019, 95, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, A.; Livne-Luzon, S.; Fox, H.; Oppenheimer-Shaanan, Y.; Klein, T. Rapid and chemically diverse C transfer from trees to mycorrhizal fruit bodies in the forest. Functional Ecology 2024, 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, D.J. Mycorrhizas in ecosystems. Experientia 1991, 47, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, D.J.; Perez-Moreno, J. Mycorrhizas and nutrient cycling in ecosystems - A journey towards relevance? New Phytologist 2003, 157, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rillig, M.C.; Wright, S.F.; Eviner, V.T. The role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and glomalin in soil aggregation. Plant and Soil 2002, 238, 325–333. Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1023/A:1014483303813.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Robert, X.; Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rog, I.; Lerner, D.; Bender, S.F.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. The Increased Environmental Niche of Dual-Mycorrhizal Woody Species. Ecology Letters 2025, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer G meta: An R package for meta-analysis. R news 2007, 7, 40–45.

- Sebastiana, M.; Duarte, B.; Monteiro, F.; Malhó, R.; Caçador, I.; Matos, A.R. The leaf lipid composition of ectomycorrhizal oak plants shows a drought-tolerance signature. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2019, 144, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuting, Z.; Hongwei, D.; Qing, M.; Rui, H.; Huarong, T.; Lianyu, Y. Identification and expression analysis of the ZRT, IRT-like protein (ZIP) gene family in Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2022, 172, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Jakobsen, I.; Grønlund, M.; Smith, F.A. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizas in plant phosphorus nutrition: Interactions between pathways of phosphorus uptake in arbuscular mycorrhizal roots have important implications for understanding and manipulating plant phosphorus acquisition. Plant Physiology 2011, 156, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal symbiosis; Academic Press and Elsevier: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Soudzilovskaia, N.A.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Terrer, C.; Zelfde; van’t, M.; McCallum, I.; Luke McCormack, M.; Fisher, J.B.; Brundrett, M.C.; de Sá, N.C.; Tedersoo, L. Global mycorrhizal plant distribution linked to terrestrial carbon stocks. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steidinger, B.S.; Crowther, T.W.; Liang, J.; Van Nuland, M.E.; Werner, G.D.A.; Reich, P.B.; Nabuurs, G.; de-Miguel, S.; Zhou, M.; Picard, N.; et al. Climatic controls of decomposition drive the global biogeography of forest-tree symbioses. Nature 2019, 569, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Yuan, D.; Hu, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y. Effects of mycorrhizal fungi on plant growth, nutrient absorption and phytohormones levels in tea under shading condition. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2020, 48, 2006–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M. Mycorrhizal types differ in ecophysiology and alter plant nutrition and soil processes. Biological Reviews 2019, 94, 1857–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-palacios, A.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Suija, A.; et al. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 2014, 346, 1052–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Zobel, M. How mycorrhizal associations drive plant population and community biology. Science 2020, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekaya, M.; Dabbaghi, O.; Guesmi, A.; Attia, F.; Chehab, H.; Khezami, L.; Algathami, F.K.; Ben Hamadi, N.; Hammami, M.; Prinsen, E.; Mechri, B. Arbuscular mycorrhizas modulate carbohydrate, phenolic compounds and hormonal metabolism to enhance water deficit tolerance of olive trees (Olea europaea). Agricultural Water Management 2022, 274, 107947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrer, C.; Jackson, R.B.; Prentice, I.C.; Keenan, T.F.; Kaiser, C.; Vicca, S.; Fisher, J.B.; Reich, P.B.; Stocker, B.D.; Hungate, B.A.; et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus constrain the CO 2 fertilization of global plant biomass. Nature Climate Change 2019, 9, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teste, F.P.; Jones, M.D.; Dickie, I.A. Dual-mycorrhizal plants: their ecology and relevance. New Phytologist 2020, 225, 1835–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teste, F.P.; Laliberté, E. Plasticity in root symbioses following shifts in soil nutrient availability during long-term ecosystem development. Journal of Ecology 2019, 107, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teste, F.P.; Veneklaas, E.J.; Dixon, K.W.; Lambers, H. Complementary plant nutrient-acquisition strategies promote growth of neighbour species. Functional Ecology 2014, 28, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nuland, M.E.; Ke, P.J.; Wan, J.; Peay, K.G. Mycorrhizal nutrient acquisition strategies shape tree competition and coexistence dynamics. Journal of Ecology 2023, 111, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Muhammad, M.; Munir, A.; Abdi, G.; Zaman, W.; Ayaz, A.; Khizar, C.; Reddy, S.P.P. Ecosystems under Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts-Williams, S.J.; Wege, S.; Ramesh, S.A.; Berkowitz, O.; Xu, B.; Gilliham, M.; Whelan, J.; Tyerman, S.D. The function of the Medicago truncatula ZIP transporter MtZIP14 is linked to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal colonization. Plant Cell and Environment 2023, 46, 1691–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.F.; Upadhyaya, A. A survey of soils for aggregate stability and glomalin, a glycoprotein produced by hyphae of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant and Soil 1998, 198, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Suseela, V.; McCormack, M.L.; Kennedy, P.G.; Tharayil, N. Common and lifestyle-specific traits of mycorrhizal root metabolome reflect ecological strategies of plant–mycorrhizal interactions. Journal of Ecology 2023, 111, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liang, Y.; Schmid, B.; Baruffol, M.; Li, Y.; He, L.; Salmon, Y.; Tian, Q.; Niklaus, P.A.; Ma, K. Soil Fungi Promote Biodiversity–Productivity Relationships in Experimental Communities of Young Trees. Ecosystems 2022, 25, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hartley, I.P.; Dungait, J.A.J.; Wen, X.; Li, D.; Guo, Z.; Quine, T.A. Contrasting rhizosphere soil nutrient economy of plants associated with arbuscular mycorrhizal and ectomycorrhizal fungi in karst forests. Plant and Soil 2022, 470, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]