1. Introduction

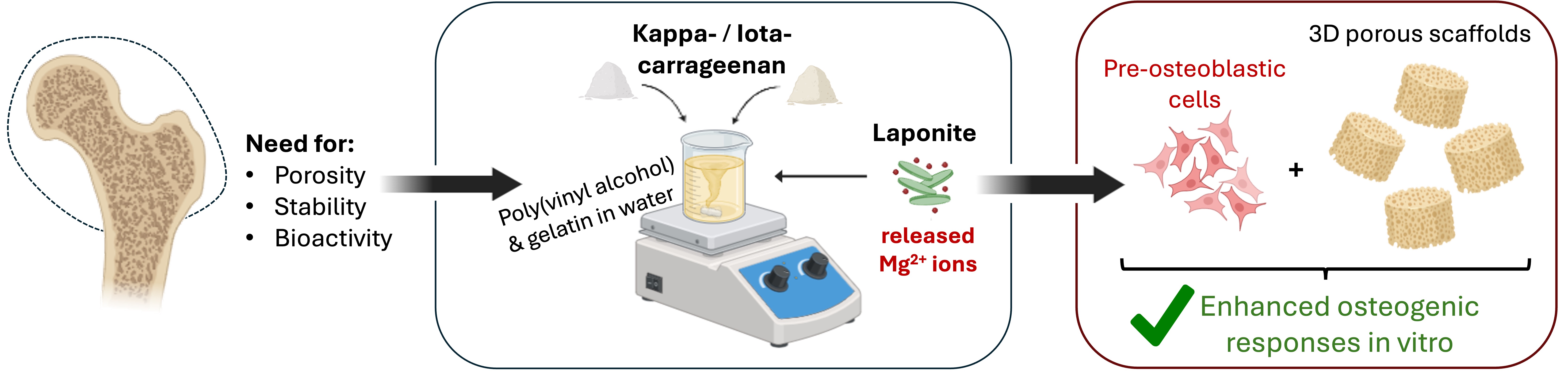

For decades, one of the major challenges in medicine has been the development of substitute biological tissue materials capable of replacing, or regenerating, diseased, or damaged, tissues in patients [

1]. Bone tissue engineering has emerged as a promising alternative to conventional bone grafts, employing functional biomaterials as scaffolds that mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM), providing a three-dimensional (3D) environment that supports cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [

2]. To this end, the properties of scaffolds are of utmost importance. Their chemical composition, biocompatibility, and osteoconductivity are essential to ensuring effective cancellous bone regeneration. Another crucial property is their porosity, as it facilitates cell penetration, vascularization and nutrient supply. Moreover, the degradation rate of the scaffolds should ideally match the rate of new tissue formation, enabling a gradual replacement by native bone. At the same time, mechanical stability is essential, as the scaffolds must withstand physiological stresses, comparable to natural bone [

3,

4].

In scaffold design for bone tissue engineering, biomaterials are broadly categorized into natural and synthetic ones. Natural biomaterials, such as proteins and polysaccharides, resemble the ECM, promoting cell adhesion and are biocompatible due to their low toxicity. Among them, gelatin (GEL), a denatured form of collagen, is widely used as it preserves bioactive sequences that support cell attachment and proliferation [

5,

6]. Additionally, sulfated polysaccharides, such as carrageenan, derived from red seaweed, have gained increasing interest in biomedical applications because of their gelling capacity, hydrophilicity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability [

7,

8]. Kappa-carrageenan (KC) and iota-carrageenan (IC) in particular are notable for their structural similarity to glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), enabling favorable biological interactions that support cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [

9,

10,

11]. Kappa-carrageenan contains one sulfate group per disaccharide unit, while iota-carrageenan has two sulfate groups, and these negatively charged groups promote electrostatic interactions with biomolecules, enhancing their biological functionality [

8,

12].

Nevertheless, natural polymers often lack adequate mechanical strength and long-term stability, making crosslinking or blending with other materials a necessity to improve scaffold robustness [

13]. To address these limitations, synthetic polymers are often incorporated to enhance durability, processability, and enable controlled degradation, despite the fact that they may lack the inherent bioactivity of natural counterparts. Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) is a linear, water-soluble polymer with excellent mechanical strength, flexibility, and elasticity [

14]. Due to its abundance of hydroxyl groups, PVA exhibits a high swelling capacity in aqueous solutions, enabling it to absorb and retain biological fluids, which enhances cytocompatibility and supports scaffold integration with surrounding tissues [

15].

Beyond polymeric systems, the incorporation of inorganic nanomaterials has attracted significant attention in tissue engineering, owing to their close resemblance to the mineral composition of bone tissue [

3,

15]. Materials such as hydroxyapatite [

16], bioactive glasses [

3], and calcium phosphates [

17] have been widely explored as a means of reinforcing scaffold architecture and providing osteoinductive properties. Alongside them, laponite (LAP, Na

+0.7[(Si

8Mg

5.5Li

0.3)O

20(OH)

4]

-0.7) [

18], a synthetic layered silicate nanoclay, has recently emerged as a highly promising additive for bone tissue engineering [

19]. It consists of disc-shaped nanoplatelets of a thickness between 1-2 nm and a diameter between 20-50 nm that illustrate a unique dual charge distribution, with negative surfaces and positively charged edges [

20]. From a biological perspective, laponite displays remarkable bioactivity, largely due to the release of its constituent ions, which are magnesium (Mg²⁺), lithium (Li⁺), sodium (Na

+), and silicate (Si(OH)₄), and have been strongly associated with osteogenic differentiation, chondrogenesis, and extracellular matrix mineralization [

21,

22]. Several studies have demonstrated that laponite alone can stimulate osteogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells, even in the absence of additional osteoinductive factors [

20,

21]. These combined physicochemical and biological properties highlight laponite’s multifunctionality as a nanomaterial that reinforces scaffold architecture, while fostering cell-material interactions to support tissue repair.

The development of composite scaffolds that combine biomimetic biopolymers and bioactive nanomaterials has great potential for reproducing the hierarchical structure and functionality of bone. Although kappa- and iota-carrageenan have been used individually or combined within the same scaffold formulation [

9,

23,

24], there are limited comparative investigations on how their different sulfation degree affects their physicochemical properties, gelation mechanism and network structure [

25,

26]. Particularly, their effect on the scaffold architecture and their osteogenic differentiation capacity has not yet been validated. Moreover, although the physicochemical properties of laponite and clay-containing composites have been reported [

27,

28], the effect of laponite combined with different carrageenan types has not been explored in the context of osteogenic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Hence, this study addresses the gap by correlating scaffold composition, structure, and function to elucidate how carrageenan sulfation and reinforcing laponite content govern mechanical performance and osteogenic cell responses. Recent work using GelMA and kappa-carrageenan bioinks incorporating laponite demonstrated that combining sulfated polysaccharides with nanoclay markedly enhanced mechanical integrity and promoted osteogenic matrix deposition, supporting the rationale for hybrid carrageenan-nanoclay constructs [

29]. To address the above mentioned hypothesis of this study, scaffolds were reinforced with either kappa- or iota-carrageenan and further functionalized with two laponite concentrations, 0.5 and 1% w/v. By directly comparing kappa and iota-carrageenan, the study aimed to elucidate the effect of the sulfate substitution of the two carrageenans on the scaffold’s hydration, stability, and biological performance. In addition, the incorporation of two different concentrations of laponite was examined to assess its reinforcing role and its capacity to provide osteoinductive cues through ion release. To this end, scaffolds were fabricated by freeze-drying and dual crosslinking. Firstly, we investigate the material properties, starting with the chemical integration, which was verified by FTIR and XRD, followed by the morphology and elemental composition, assessed by SEM/EDS. Structural characteristics, including apparent density, porosity, and compressive modulus, were quantified, alongside swelling and degradation, which directly impact cell adhesion, growth, and mineralization. Subsequently, the biological performance of the scaffolds was evaluated with MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblastic cells through assays of cell adhesion, viability/proliferation, ALP activity, calcium secretion, and collagen production. This comparative approach provides insights into the synergistic potential of natural polysaccharides and nanoclay for designing multifunctional scaffolds that recapitulate both the organic and inorganic phases of native bone tissue, thereby offering practical guidelines for scaffold design in bone tissue engineering.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Gelatin from bovine skin, polyvinyl alcohol (Mw 145,000 kg/mol), k-carrageenan, i-carrageenan, glutaraldehyde, potassium chloride, L-ascorbic acid, β-glycerophosphate, and dexamethasone were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Laponite XLG was purchased from BYK Additives Ltd (Widnes, UK). The PrestoBlue™ reagent was purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Trypsin/EDTA (0.25%) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from Gibco ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Paraformaldehyde (PFA), Triton X-100, p-nitro-phenyl-phosphate (pNPP), and Sirius Red 90 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). penicillin/streptomycin was purchased from Gibco ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Minimum essential Eagle’s medium (alpha-MEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from PAN-Biotech (Aidenbach, Germany). O-cresol phthalein complexone reagent kit was purchased from Biolabo (Les Hautes Rives Maizy, France). Bradford reagent was purchased from AppliChem GmbH (Darmstadt, Germany).

2.2. Fabrication of the 3D Scaffolds

For the preparation of the 3D scaffolds, 1% w/v of iota- and kappa-carrageenan were employed, while keeping the PVA/gelatin concentration constant. Prior to mixing, all ingredients were sterilized under ultraviolet light. Initially, 3% w/v poly(vinyl alcohol) was dissolved in deionized water at 90 °C under continuous stirring for 4 h. After cooling the PVA solution to 50 °C, 3% w/v gelatin was added, and the mixture was stirred for an additional 2 h. Subsequently, the appropriate carrageenan powder was directly added to the PVA/gelatin solution, and the resulting blend with final concentrations of 3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin and 1% w/v KC or IC was stirred at a constant temperature of 50 °C for 4 h to ensure complete homogeneity.

For the samples containing Laponite XLG, the same procedure was followed, with the modification that different amounts of laponite were added to the cooled PVA solution prior to the addition of gelatin and carrageenan, to ensure complete dispersion of the clay. An initial attempt using 2% w/v Laponite XLG resulted in the formation of a highly viscous gel, which hindered the proper integration of the remaining components and led to the appearance of visible aggregates. Therefore, reduced concentrations of 0.5% and 1% w/v were used in subsequent preparations. Each mixture was stirred for 4 h before the addition of gelatin and carrageenan.

Subsequently, the final solutions were cast into 96- and 48-well plates and stored at -23 ˚C for 4 h, followed by lyophilization at -40 °C overnight to achieve physical crosslinking [

14]. After the freeze-drying process, chemical crosslinking was carried out in two steps. The first step was performed using 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde for 30 min. All samples were then rinsed twice with deionized water and subjected to a second crosslinking step using 0.2 M potassium chloride (KCl) for the same duration [

9]. To ensure the removal of any unbound crosslinker residues, all scaffolds were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water.

Table 1 summarizes the different scaffold types, including their compositions, concentrations, and crosslinking methods.

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization of the Scaffolds

2.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR analysis was performed on the different blend scaffold compositions, as well as on their basic components (gelatin, PVA, kappa- and iota-carrageenan, and laponite). The infrared spectra were recorded in transmittance mode using a Nicolet 6700 optical spectrometer over the range of 4000-400 cm⁻¹, with 64 scans collected for each spectrum. The spectral data were graphically represented using Python (Jupyter Notebook).

2.3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis (XRD)

The phase composition of pure substrates and scaffolds was investigated using a SmartLab SE X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku Co., Japan) equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). Before measurement, the scaffolds were freeze-dried for 24 h to remove residual water and minimize background noise. All XRD measurements were carried out at room temperature using a five-axis goniometer with an in-plane arm, operating at 40 kV and 50 mA, with a step size of 0.01°/2θ. Data were collected over a 2θ range of 5-65°. The spectral data were graphically represented using Python (Jupyter Notebook).

2.3.3. Surface Morphology and Elemental Composition of the Scaffolds

The surface morphology and microstructure of the scaffolds were examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JEOL JSM-6390 LV, MA, USA) operated at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. In brief, before imaging, freeze-dried scaffolds were sputter-coated with a 10 nm Au layer (Baltec SCD 050, Los Angeles, CA, USA) to enhance conductivity. The elemental analysis of the scaffolds was performed simultaneously using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) integrated within the SEM. The resulting X-ray spectra generated by the interaction of the electron beam with the sample were analyzed to identify and quantify the elemental composition of the scaffolds.

2.3.4. Water Uptake Measurements

To quantify the swelling capacity of the scaffolds, after the crosslinking process, they were freeze-dried for 12 h, and their dry weight was measured (weight

dry). Furthermore, the samples were immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) and placed for 1 and 24 h at 37 °C in a CO

2 incubator (Thermo Scientific™, Forma™ Steri-Cycle™, Waltham, MA, USA). After incubation, the excess PBS was carefully removed by gently dabbing the samples with a paper towel, and their swollen weight was measured (weight

wet). All weight measurements were conducted using a high-precision analytical balance (ABT 220-5DNM) with a readability of ±1 μg. All samples were analyzed in groups of three (n = 3). The swelling ratio was calculated following the formula:

2.3.5. In Vitro Degradation Testing

For the degradation study, the scaffolds were immersed in PBS (pH 7.4) and incubated at 37 °C. At selected time points (7, 14, 21, 28, and 40 days), the scaffolds were removed from the medium, gently dabbed with a paper towel to remove the excess of PBS, and then weighed to assess their degradation. All samples were analyzed in groups of five (n = 5). The degradation ratio was calculated using the following formula:

2.3.6. Ion Release Study

To evaluate the release of inorganic ions from the scaffolds, acellular samples were immersed in 100 μL of alpha-MEM™ medium and incubated at 37 °C for 1, 7, 14, and 21 days. At each time point, the supernatants were collected and analyzed using the O-cresol phthalein complexone (CPC) method. Although the CPC assay is primarily designed to quantify Ca

2+, it can also form colored complexes with other divalent cations, including Ba

2+, Mg

2+, Sr

2+, Pb

2+, and Zn

2+ [

30]. Because laponite releases Mg

2+ upon dissolution, the absorbance measured in CPC assays reflected the presence of Mg

2+ ions rather than calcium. For each sample, 10 μL of supernatant was mixed with 100 μL of calcium buffer and 100 μL of CPC dye [

9], transferred into a 96-well plate, and the absorbance was recorded at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer. All samples were analyzed in quadruplicate (n = 4).

2.3.7. Density and Porosity

The apparent density and porosity of the scaffolds were measured using the liquid displacement technique [

31,

32]. In this method, ethanol was selected as the wetting agent because it can easily penetrate the scaffolds' pores without causing shrinkage, swelling, or dissolution at room temperature. Briefly, a known mass of freeze-dried scaffolds (W) was immersed in a graduated cylinder containing a known volume of ethanol (V

1) and ultrasonically stirred until their pores were completely filled with ethanol, no air bubbles were observed, and the specimens were fully submerged. The total volume was then recorded as V

2. Subsequently, the scaffolds were withdrawn from ethanol, and the remaining ethanol volume was recorded as V

3. The average values of five measurements (n = 5) were taken to validate the porosity and density of the specimens. The density and porosity of the scaffolds were calculated by the following equations:

2.3.8. Mechanical Characterization of the Scaffolds

The effect of carrageenan and laponite incorporation into PVA/gelatin on the mechanical properties of the hydrogels was evaluated by uniaxial compression tests. Testing was conducted using a mechanical test system (UniVert, CellScale, Waterloo, Canada) with a maximum load capacity of 50 N. The Young’s modulus was measured at the linear regime of a strain range of 40-60%, with a deformation speed of 5 mm/s, using six replicates for each scaffold composition (n = 6). The Young’s modulus of the samples was determined as the slope in the linear elastic deformation region of the stress–strain graph according to the formula:

where F stands for the perpendicular force applied to the surface area A of the scaffold, ΔL is the change in scaffold height after force application, and L is the initial height of the samples.

2.4. In Vitro Biological Characterization of the Scaffolds

2.4.1. Cell Culture and Cell Viability Evaluation

To estimate the biological performance of the scaffolds, the MC3T3-E1 mouse calvaria osteoblast precursor cell line was used as the model for in vitro assays. Cells of passage 19 were cultured in alpha-MEM™ medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in an incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Before the cell seeding, all scaffolds were sterilized by UV irradiation for 15 min on each side. A suspension of 5×103 cells in 10 μL of complete medium was carefully pipetted onto each scaffold, followed by incubation for 1 h to allow cell attachment. Subsequently, culture medium was added to reach a final volume of 160 µL per scaffold. The medium was refreshed every three days.

The viability of the MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells was determined using the PrestoBlue™ assay. At each time point (3, 7, and 14 days), 10 μL of PrestoBlue™ reagent diluted 1:10 in fresh α-MEM™ medium was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 1 h. After that, 100 μL of the supernatant of each sample was transferred to a 96-well plate, and the absorbance was measured at 570 and 600 nm using a spectrophotometer. All samples were analyzed in quintuplicate (n = 5).

2.4.2. SEM Imaging

The cell-seeded scaffolds intended for SEM visualization were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. On day 1, they were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% v/v paraformaldehyde for 25 min, and placed at -23 °C. After the stabilization period, the samples were washed again with PBS to remove any remaining fixative, and dehydration occurred through 10 min washes with gradually increasing ethanol concentrations (30, 50, 70, 90, and 100% v/v). Afterwards, the samples were sputter-coated with gold for 90 seconds, following a similar procedure to that applied for the scaffolds without cells.

2.4.3. Measurement of the Alkaline Phosphatase Activity (ALP)

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is a key enzyme expressed in mineralized tissues, particularly during bone formation, where it detaches phosphate groups and facilitates the production of hydroxyapatite crystals. These crystals are a fundamental component of the extracellular matrix, as they accumulate between collagen fibrils and contribute to the mineralization of bone tissue [

33]. The ALP activity is an early-stage indicator of osteogenesis; therefore, 40×10

3 pre-osteoblastic cells were seeded onto the different scaffold compositions and cultured for 3, 7, and 14 days. To induce osteogenic differentiation, the cell-loaded scaffolds were cultured in primary culture medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml l-ascorbic acid, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 10 nM dexamethasone.

Based on a previously established protocol [

34], the cell-loaded scaffolds were washed three times with PBS, covered with 100 μL of cell lysis buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 10.5), and then subjected to two freezing/thawing cycles between -23 °C and room temperature. After that, 100 μL of the suspension from each well was mixed with 100 μL of a 2 mg/mL p-nitro-phenyl-phosphate (pNPP) solution diluted in 50 mM Tris-HCl and 2 mM MgCl

2 buffer, and the total mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, 100 μL of each sample were transferred to a 96-well plate and the color change was measured at 405 nm using a spectrophotometer (Synergy HTX Multi-Mode Micro-plate Reader, BioTek, Bad Friedrichshall, Germany). The enzymatic activity was expressed as nmol pNPP/min, and normalized to the total cellular protein content, which was determined using the Bradford method for protein concentration measurement. All samples were analyzed in five replicates (n = 5).

2.4.4. Assessment of Calcium Concentration Levels

Calcium production is associated with the formation of hydroxyapatite, and its deposition is considered a late marker of osteogenesis, indicating the formation of the ECM. To determine calcium secretion, the O-cresol phthalein complexone method was employed. In an alkaline solution, CPC reacts with calcium to form a dark-red complex, and the absorbance of this is proportional to the calcium concentration. Supernatants from cell-seeded scaffolds containing 40×10

3 MC3T3-E1 cells were collected every three days up to day 21. For analysis, 10 μL of culture medium from each sample was mixed with 100 μL of calcium buffer and 100 μL of calcium dye [

9]. The mixtures were transferred to 96-well plates, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer. Values of cell-free scaffolds have been subtracted as blank. All samples were analyzed in quadruplicate (n = 4).

2.4.5. Determination of Secreted Collagen

To measure collagen production by cultured cells on the scaffolds, the Sirius Red Dye assay was used. The anionic Sirius Red dye contains negatively charged sulfonic acid groups that ionically bind to the positively charged amino groups of the various collagen types produced by the cells [

35]. A total of 40×10

3 pre-osteoblastic cells were seeded onto the different scaffolds. At each time point (7, 14, and 21 days), 25 μL of each supernatant was diluted in 75 μL of dH

2O in a 2 mL Eppendorf tube. Then, 1 mL of 0.1% w/v Sirius Red Dye solution in 0.5 M acetic acid was added, and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 45 min. After the time had passed, the samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 15,000 g. The supernatant was poured off and replaced with 1 mL of fresh acetic acid. This step was repeated several times to remove the residual non-bound dye until the supernatant was transparent. To release the bound dye from the collagen pellet, 1 mL of 0.5 M NaOH was added to each tube, vortexed, and 200 μL of the resulting solution was transferred to a 96-well plate to measure its absorbance at 530 nm. A standard curve was prepared to correlate absorbance values with collagen concentration (μg/mL). All samples were analyzed in groups of six (n = 6).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software to evaluate the significance of the differences between various scaffold compositions and the PVA/GEL control (*), between KC and IC scaffolds (#), and between LAP0.5 and LAP1 (§). A two-way ANOVA Dunnett’s multi-comparison test was performed for degradation, ion release, cell viability, ALP activity, calcium production, and collagen secretion. Compression, porosity, and density were analyzed with one-way ANOVA Dunnett’s multi-comparison test, while swelling capacity was measured through two-way ANOVA Sidak’s multi-comparison test. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD), with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Tissue engineering aims to develop biomaterial-based scaffolds that provide cell-permissive microenvironments while ensuring sufficient structural support for tissue formation. Natural polymers offer excellent bioactivity, while synthetic polymers and inorganic additives contribute structurally to integrity and mechanical reinforcement. However, the limited mechanical resilience of natural biomaterials often necessitates physical/chemical crosslinking strategies, as well as compositional modifications, to optimize their performance for targeted biomedical applications. In this context, the present study focused on the development of PVA/GEL-based scaffolds reinforced with kappa- and iota-carrageenan and further functionalized with laponite, aiming to fabricate composite scaffolds with favorable physicochemical, mechanical, and biological properties suitable for bone tissue engineering. To enhance stability, a dual crosslinking strategy was applied, using a low concentration of glutaraldehyde to covalently link free amino groups of gelatin with hydroxyl groups in PVA and carrageenan, thereby strengthening the polymeric network [

9,

13]. In contrast, potassium chloride was used to ionically crosslink carrageenan, enhancing its gelling capacity and further stabilizing the porous architecture [

23,

48,

49].

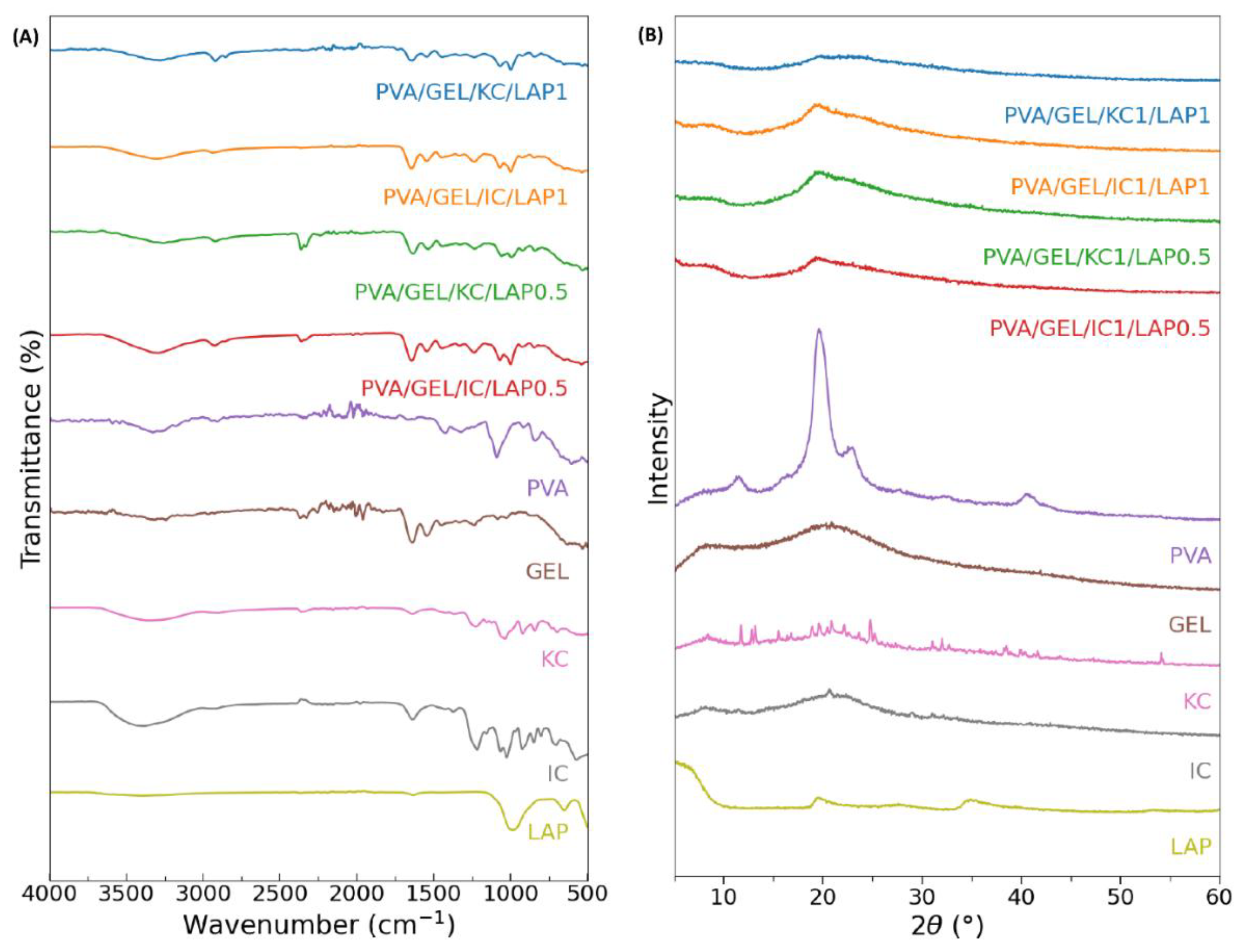

The chemical composition and successful incorporation of each constituent were confirmed by FTIR analysis, which revealed the characteristic absorption bands of PVA, gelatin, carrageenans, and laponite within the composite spectra. Gelatin’s amide I/II peaks (1650/1540 cm-1) and carrageenan’s sulfate signatures (1220-1260 cm-1; 900-850 cm-1) remained visible, indicating preservation of the biopolymer backbones. In LAP-containing scaffolds, broadening and slight shifting of the O-H stretching band indicated an extensive hydrogen-bonding network, while the Si-O vibrations increased proportionally with LAP content, confirming its stable integration into the polymer network. The absence of new diagnostic bands supports reinforcement dominated by physical interactions rather than new covalent chemistry.

Complementary XRD analysis further corroborated these findings, showing broad halos centered at 2θ of 20-22° characteristic of an amorphous polymer matrix. The attenuation of the basal LAP reflection at 6-8° suggested nanoscale dispersion of laponite within the polymeric network. Moreover, the increased intensity of silicate-associated features with higher LAP loading at 20° confirmed the presence of well-dispersed silicate domains without the formation of new crystalline phases. Together, these results validate the effectiveness of polymer-nanoclay interactions and the homogeneous distribution of laponite within the scaffolds [

27].

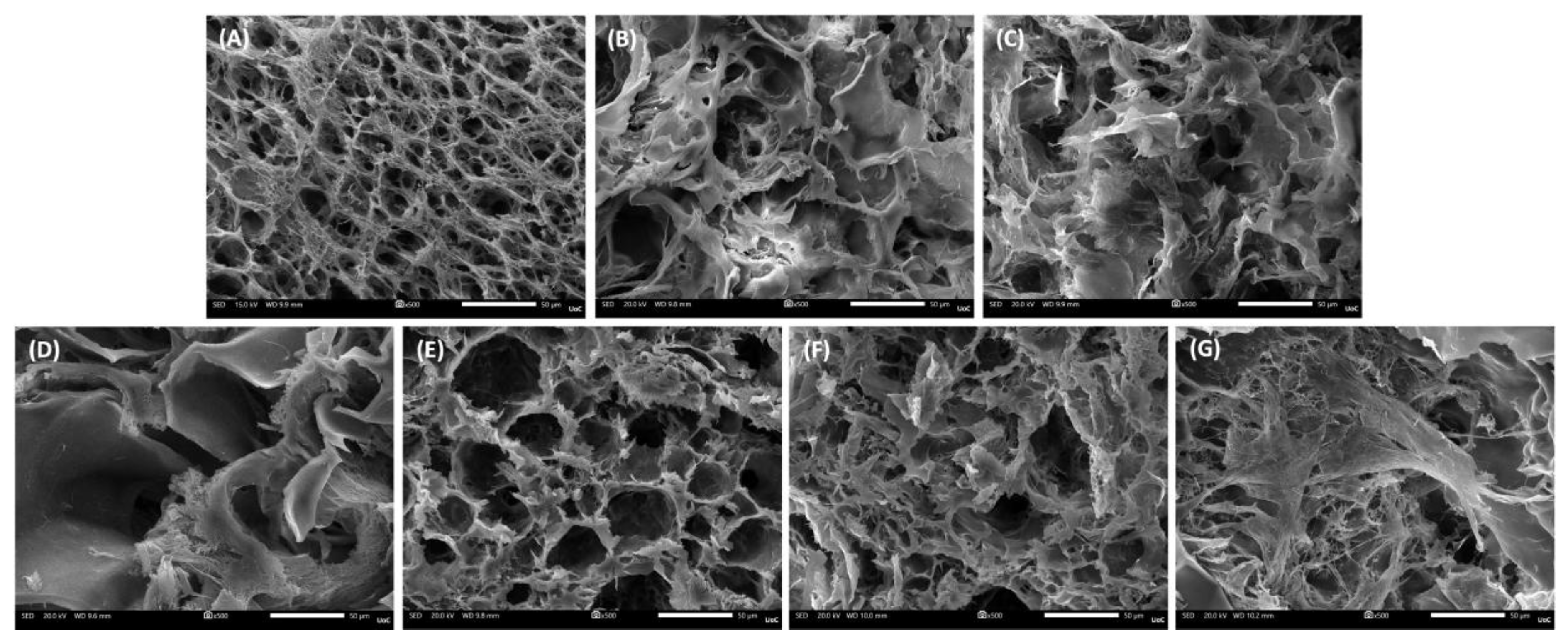

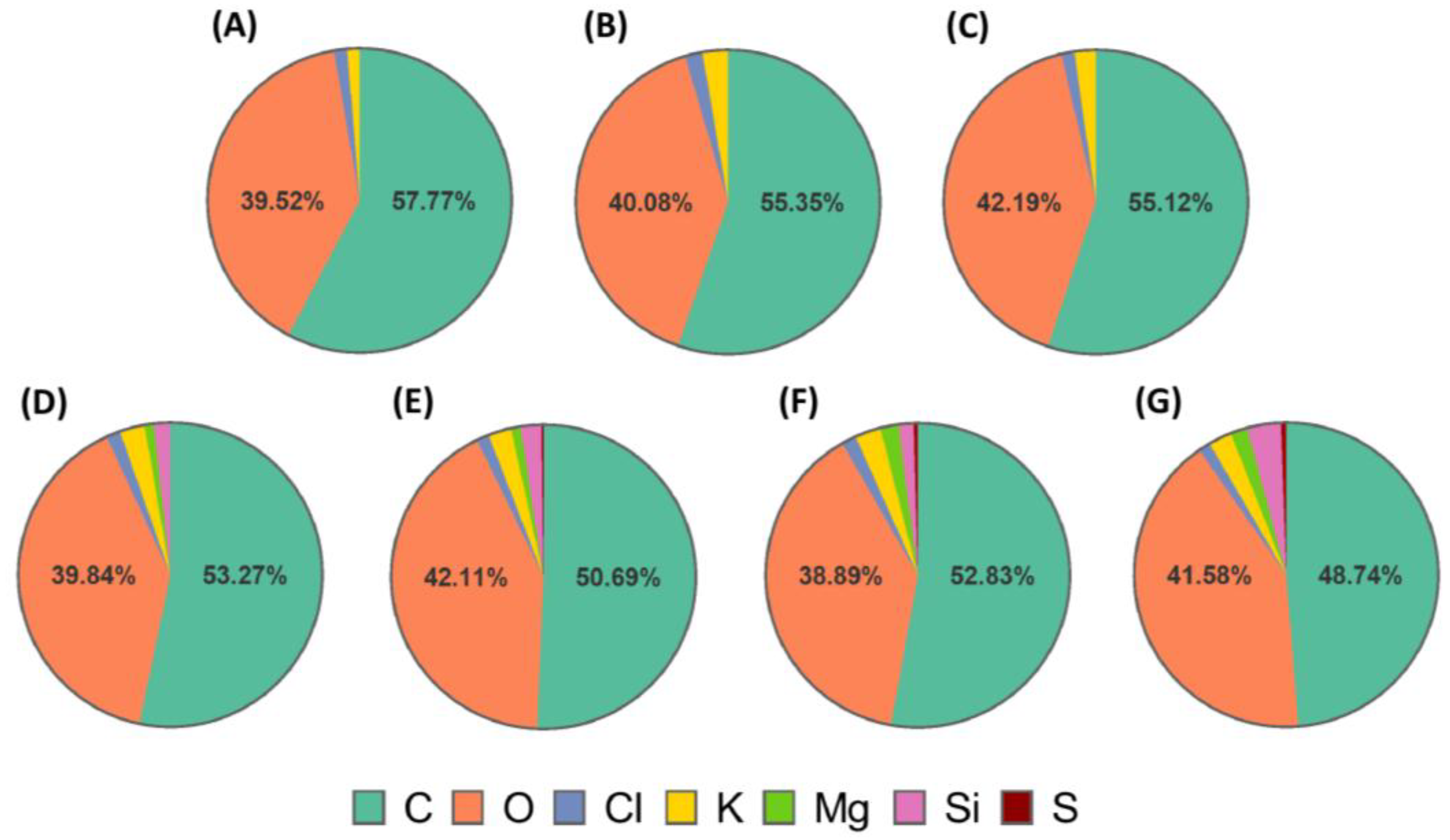

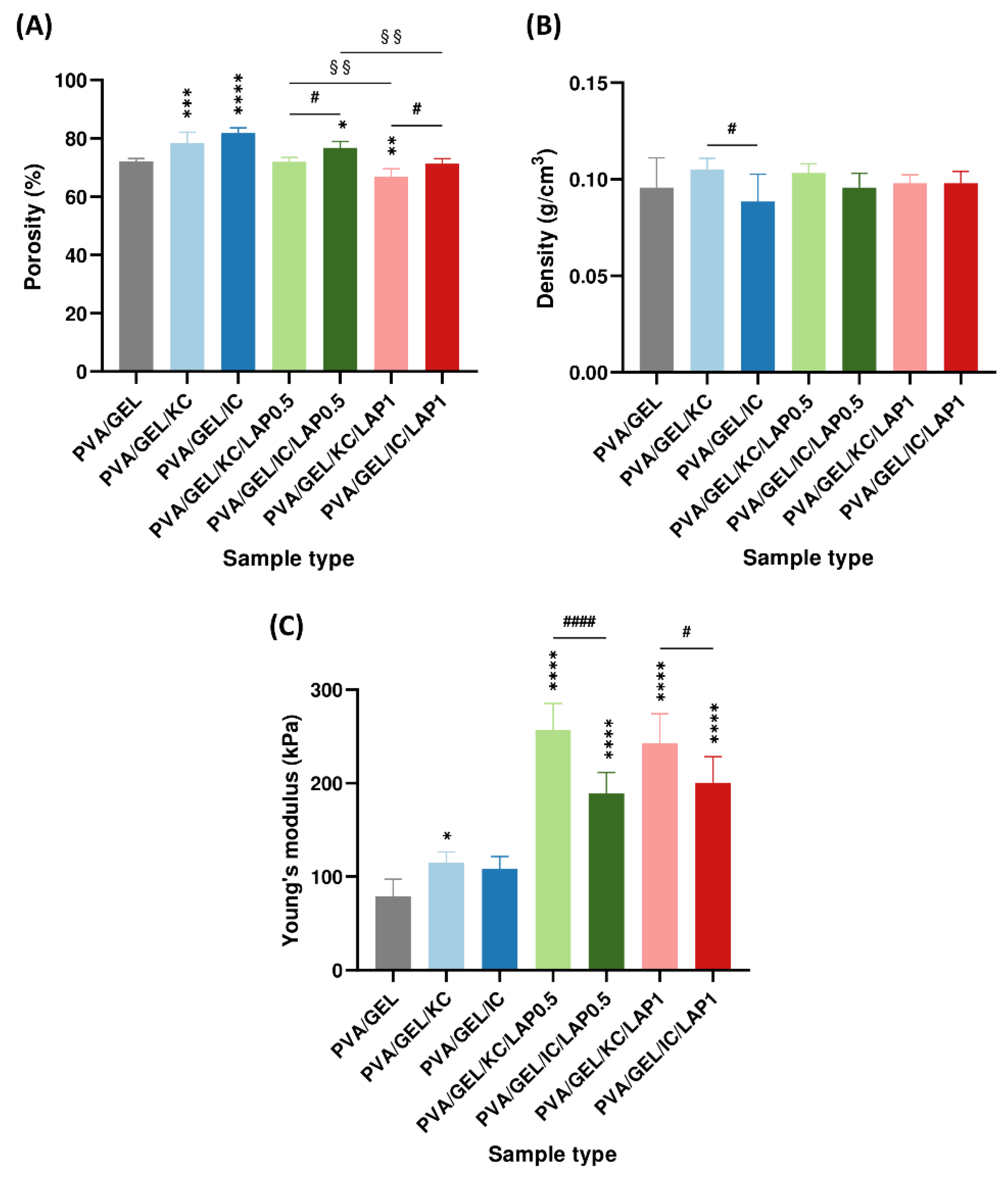

At the structural level, the addition of carrageenan increased pore openness without altering bulk density, whereas LAP preserved interconnectivity but densified the pore walls. As the laponite concentration increased, porosity was progressively reduced, producing a more compact and uniform pore architecture [

50,

51]. Nevertheless, the developed scaffolds exhibited a porosity of approximately 75%, which falls within the reported range for trabecular bone (50-90%) [

52], and an apparent density maintained between 0.09-0.11 g/cm

3, exhibiting their suitability for bone tissue engineering. Statistical comparisons revealed that porosity was significantly higher in IC-based scaffolds than in KC-based scaffolds. This result aligns with the higher sulfation degree of IC, which introduces more negatively charged sulfate groups, enhances electrostatic repulsion along the polysaccharide chains, increases water retention, and leads to a more hydrated and open polymer network [

53]. Moreover, the successful integration of laponite into the scaffold matrix is further confirmed by Mg and Si elemental peaks detected by EDS, consistent with the incorporation of the nanoclay [

54].

Regarding compression tests, the obtained stress-strain curves provided insight into the scaffolds’ load-bearing behavior. Carrageenan-containing scaffolds indicated modest improvements in compressive properties, whereas LAP incorporation led to a marked reinforcement of the matrix. The stress-strain response displayed an initial linear elastic stage, a plateau characterized by reduced stiffness due to progressive collapse of the pore walls, and a densification phase at strains above approximately 60%, where strain hardening occurred as the pores became fully compacted. Similar mechanical behavior has been reported in other gelatin-based soft tissue scaffolds containing carrageenan and chitosan [

55], as well as in collagen-glycosaminoglycan scaffolds for bone tissue engineering, in which the transition from the elastic to the plateau and densification regions reflects the gradual deformation and compaction of the porous network [

56]. The Young’s modulus increased with laponite incorporation, reaching values exceeding 190 kPa, which remain below those of native cancellous bone reported at 50-500 MPa [

57], but clearly indicate the reinforcing effect of laponite [

58]. Notably, the modulus was significantly higher in KC-based scaffolds compared to IC-based ones. This behavior can be explained by the lower sulfation degree of KC, which reduces electrostatic repulsion between polymer chains and favors K⁺-mediated double-helix aggregation, resulting in a denser network with stronger intermolecular junctions and, consequently, a mechanically more resilient network [

53,

59]. This enhancement can be attributed to polymer-nanoclay interactions, which restrict polymer chain mobility and strengthen the composite matrix [

58].

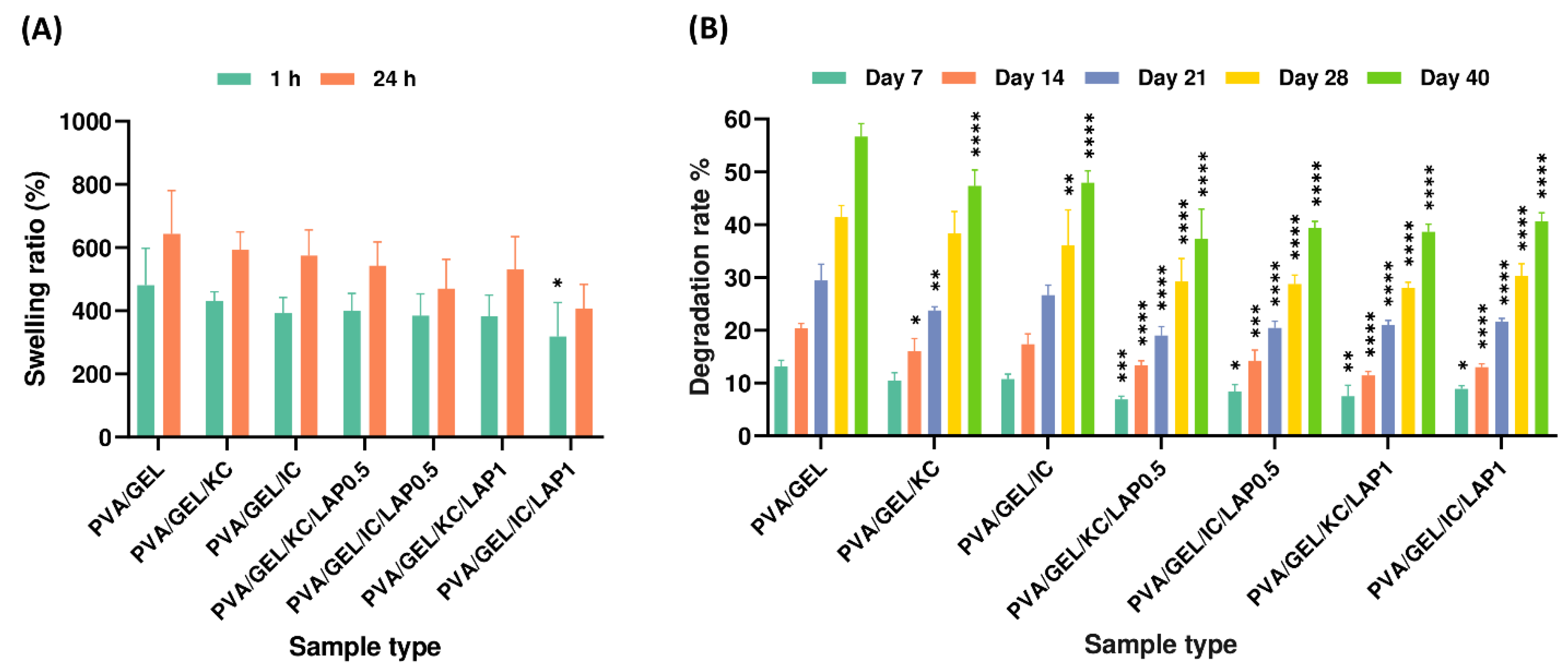

The swelling behavior of scaffolds is a critical parameter in tissue engineering, as it directly affects nutrient diffusion, waste removal, and the maintenance of a hydrated microenvironment, necessary for cell survival and proliferation. Scaffolds with higher fluid uptake can better emulate the native extracellular matrix, supporting matrix remodeling and tissue ingrowth, while excessive swelling may compromise structural integrity. Therefore, the swelling and degradation characteristics of the fabricated scaffolds were evaluated to assess their suitability for bone tissue regeneration. Hydration studies indicated that carrageenan-containing scaffolds exhibited the highest swelling ratios, reaching nearly 600% of their dry weight, in agreement with previous findings [

4,

55], while laponite reduced fluid uptake, which is in line with other reports demonstrating significant reduction of water uptake in the respective composite [

15]. This inverse relationship between swelling and laponite concentration suggests that the nanoclay acts as a physical crosslinker, tightening the polymer network and restricting water diffusion. This reduction can be attributed to the inorganic nature of laponite, which forms strong physical interactions with polymer chains, limiting their mobility and decreasing the free volume available for water penetration [

60]. Additionally, this behavior can be attributed to the hydrophilic and polyanionic nature of carrageenan, whose sulfated chains closely resemble glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) [

61], promoting strong water uptake and matrix hydration [

7,

9]. In parallel, degradation assays revealed that higher swelling correlated with faster mass loss, with KC and IC scaffolds degrading more rapidly due to their highly hydrated and open structures. Conversely, the reduction in swelling upon laponite addition led to long-term stability, with over 60% of the initial mass retained after 40 days [

55]. Collectively, these trends indicate that carrageenan and laponite act complementarily to balance permeability and mechanical stability in PVA/GEL-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. This balance between hydration and stability is crucial, as it determines the scaffold’s microenvironmental properties, affecting nutrient transport, matrix remodeling, and the maintenance of structural integrity that is necessary for subsequent cell adhesion and growth.

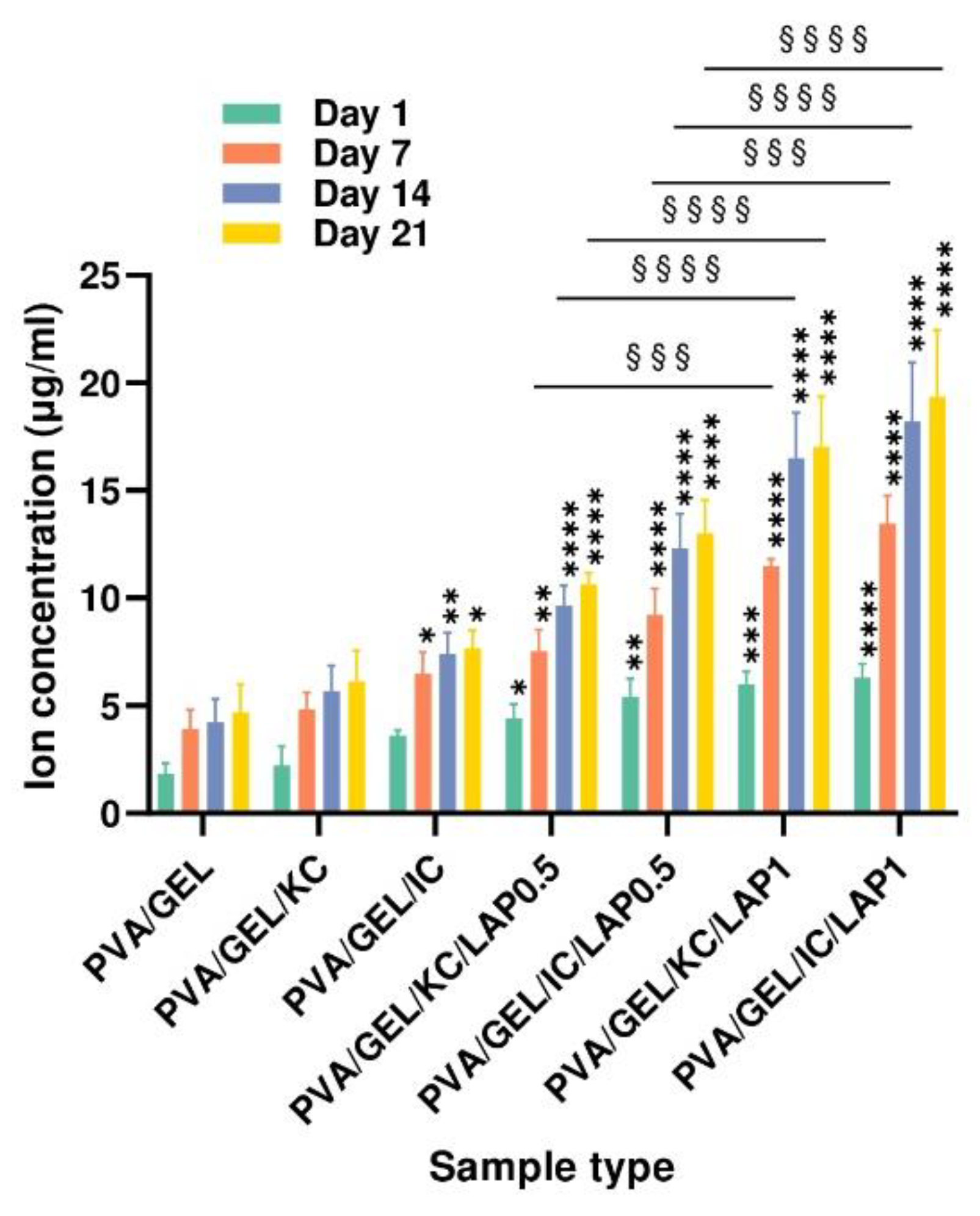

The ion-release profiles demonstrate that laponite-containing scaffolds provide a sustained and composition-dependent source of Mg

2+ over the 21-day incubation period. This behavior is consistent with the dissolution mechanism of laponite and supports its role as an active inorganic component within hybrid biomaterials. The markedly higher ion concentrations observed in the LAP1 formulations indicate that increasing laponite content enhances ionic availability. This controlled Mg

2+ release is particularly relevant for bone tissue engineering, as magnesium ions play an active role in regulating osteogenic signaling pathways. Previous studies have shown that Mg

2+ can activate the mechanosensitive transient receptor potential cation channel TRPM7 ion channel and kinase in osteoblasts, triggering osteogenic proliferation and differentiation through downstream phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent mechanisms [

62]. Although the present work did not isolate specific ion-driven pathways, the clear concentration-dependent release trends suggest that Mg

2+ delivery from laponite could synergize with the polymeric matrix to enhance the osteoinductive potential.

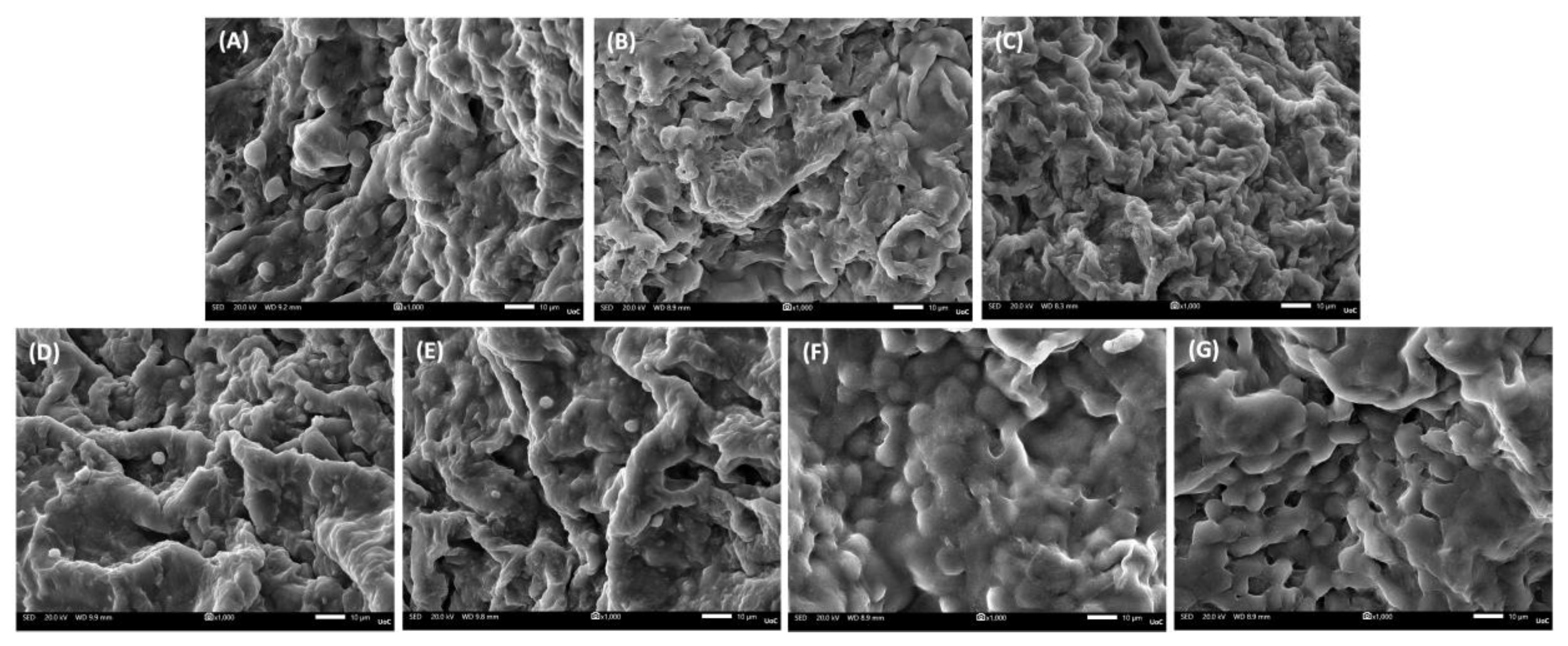

Biologically, all formulations demonstrated intrinsic cytocompatibility, supporting early adhesion and viability of MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts. However, LAP-containing composites outperformed PVA/GEL and carrageenan-containing variants across the functional biological assessment. Specifically in morphological observations, carrageenan incorporation promoted a more uniform distribution of adherent cells, whereas laponite addition led to denser and more elongated cell layers, consistent with stronger focal adhesion and cytoskeletal organization. This observation aligns with previously reported findings [

51], indicating that laponite-based polymer nanocomposites enhance cell attachment and spreading through improved surface charge distribution and nanoscale roughness. Over 7 days, metabolic activity and viability increased across all groups, with scaffolds containing 0.5 wt% LAP significantly outperforming 1 wt% LAP, suggesting that moderate nanoclay content better supports early proliferation. Interestingly, while other studies reported on enhanced proliferation at higher LAP concentrations, using similar doses [

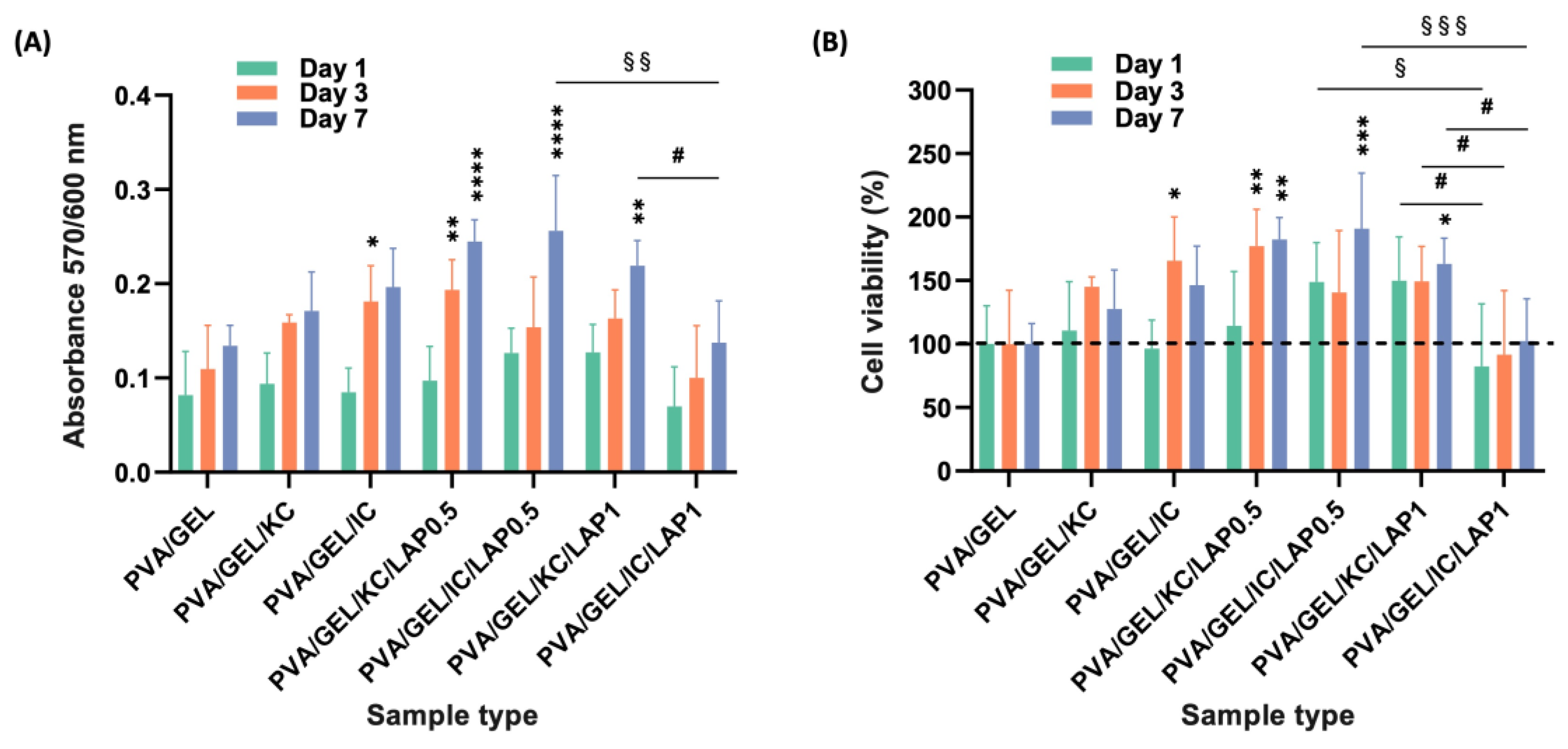

63], this discrepancy may arise from differences in the polymeric matrices, crosslinking strategies, or scaffold microstructure, all of which govern ion release, porosity, and cell-matrix interactions. In our system, the denser and stiffer network formed at 1 wt% LAP may have partially hindered nutrient diffusion and cell spreading during early culture, outweighing the potential benefits of increased bioactive ion release. These observations highlight the importance of matrix-specific optimization when integrating nanofillers such as laponite into scaffold formulations.

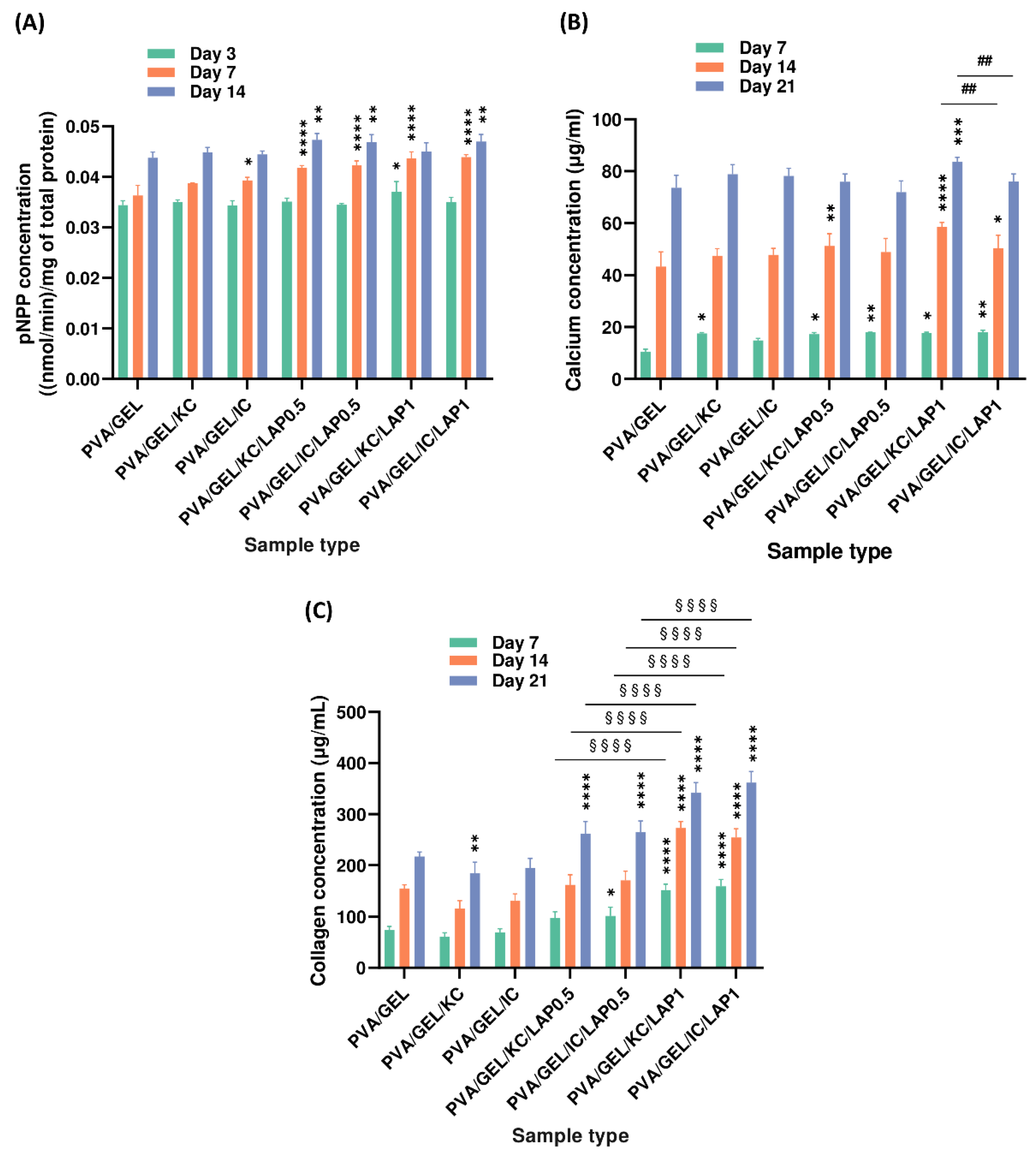

Markers of osteogenic differentiation followed a composition-dependent trend. LAP groups exhibited significantly higher ALP activity than the PVA/GEL control on day 14, reflecting early osteogenic commitment. Also, ALP activity levels were significantly higher in IC-based scaffolds compared to KC-based ones on day 14, suggesting that the higher sulfate content in iota-carrageenan may stimulate differentiation pathways more effectively by modulating the adsorption and conformation of osteogenic proteins from the culture medium such as fibronectin and collagen type I, thereby creating a microenvironment more favorable for early osteogenic signaling and ALP expression [

64]. Additionally, between days 14 and 21, LAP-containing composites demonstrated further matrix maturation, as evidenced by increased calcium and collagen production, particularly observed in those containing 1 wt% LAP, confirming a dose-dependent enhancement in mineralization potential and ECM synthesis. Calcium production was markedly elevated in PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1 and PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1 scaffolds at day 21, emphasizing the role of LAP in promoting mineral secretion, consistent with previous reports showing that the release of bioactive silicate ions from laponite activates the osteogenic pathway, through upregulation of RUNX2, thereby enhancing downstream mineralization processes [

21,

22]. Similarly, collagen synthesis was strongly upregulated in all LAP groups, with LAP1 scaffolds showing significantly higher levels than LAP0.5 across all time points. While no consistent trend was observed between KC and IC, the results underscore the dominant effect of LAP content at this late stage. However, it is worth noting that the maximum collagen concentration in our system was approximately 350 μg/mL, and although it remains lower than those reported in other osteogenic scaffolds (e.g., around 1000 μg/mL in [

65]), it is comparable to values reported in hydroxyapatite-based scaffolds [

66]. Nevertheless, the results clearly illustrate the synergistic interaction between laponite and carrageenan, consistent with previous studies reporting strong physicochemical compatibility and enhanced structural stability in carrageenan-laponite nanocomposite hydrogels, where electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions between the two components improved crosslinking density and structural integrity [

28,

67]. These molecular interactions align with prior evidence showing that silicate ions contribute to collagen fibrillogenesis and integrin-mediated adhesion, thereby promoting mineralization and extracellular matrix formation [

21,

68].

Overall, the findings of this study demonstrate a correlation between molecular composition, structural organization, and resulting scaffold performance. The comparative analysis between kappa- and iota-carrageenan revealed that the lower sulfation degree of KC produced a denser and mechanically stronger network, characterized by significantly lower porosity, higher apparent density, and an increased Young’s modulus relative to IC. This compact structure correlated with higher cell viability and enhanced calcium secretion at later stages, highlighting the contribution of mechanical stability to mineralization. Conversely, IC, with its higher degree of sulfation, formed a more hydrated and open network, which favored protein adsorption and higher ALP activity, suggesting a link between sulfate-mediated bioactivity and early differentiation. The effect of laponite concentration was equally evident. Specifically, LAP0.5 preserved porosity and supported early proliferation, whereas LAP1 led to a notable densification of the pore walls, enhancing matrix mineralization and collagen production, reflecting the reinforcement effect of higher nanoclay loading. Together, these results confirm that scaffold architecture and biological functionality can be systematically tuned through the interplay between carrageenan type and laponite content to establish a potential strategy for structure-property-function correlations. In addition, controlling the crosslinking conditions would lead to a more comprehensive understanding of how molecular design governs the mechanical and osteogenic performance in composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering.

Figure 1.

(A) Fourier transform infrared spectra and (B) X-ray diffraction patterns of the individual components in powder form (PVA, GEL, KC, IC, and LAP), alongside the four compositions PVA/GEL/KC/LAP0.5, PVA/GEL/IC/LAP0.5, PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1, and PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1.

Figure 1.

(A) Fourier transform infrared spectra and (B) X-ray diffraction patterns of the individual components in powder form (PVA, GEL, KC, IC, and LAP), alongside the four compositions PVA/GEL/KC/LAP0.5, PVA/GEL/IC/LAP0.5, PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1, and PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1.

Figure 2.

SEM images of cell-free scaffold cross-sections at a magnification of ×500 (scale bar represents 50 μm). (A) PVA/GEL, (B) PVA/GEL/KC, (C) PVA/GEL/IC, (D) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP0.5, (E) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP0.5, (F) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1, (G) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1.

Figure 2.

SEM images of cell-free scaffold cross-sections at a magnification of ×500 (scale bar represents 50 μm). (A) PVA/GEL, (B) PVA/GEL/KC, (C) PVA/GEL/IC, (D) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP0.5, (E) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP0.5, (F) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1, (G) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1.

Figure 3.

Elemental composition (mass%) monitored by EDS of scaffold cross-sections (A) PVA/GEL, (B) PVA/GEL/KC, (C) PVA/GEL/IC, (D) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP0.5, (E) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP0.5, (F) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1, (G) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1.

Figure 3.

Elemental composition (mass%) monitored by EDS of scaffold cross-sections (A) PVA/GEL, (B) PVA/GEL/KC, (C) PVA/GEL/IC, (D) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP0.5, (E) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP0.5, (F) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1, (G) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1.

Figure 4.

(A) Porosity (%), (B) density (g/cm³), and (C) Young’s modulus (kPa) of the scaffolds. Young’s modulus was measured at the linear regime of 40-60% strain and 5 mm/sec compression speed. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance relative to the PVA/GEL control scaffold is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; differences between KC and IC are shown as #p < 0.05, ####p < 0.0001; and between LAP0.5 and LAP1 are §§p < 0.01.

Figure 4.

(A) Porosity (%), (B) density (g/cm³), and (C) Young’s modulus (kPa) of the scaffolds. Young’s modulus was measured at the linear regime of 40-60% strain and 5 mm/sec compression speed. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance relative to the PVA/GEL control scaffold is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; differences between KC and IC are shown as #p < 0.05, ####p < 0.0001; and between LAP0.5 and LAP1 are §§p < 0.01.

Figure 5.

(A) Swelling ratios of the scaffolds after 1 and 24 h of immersion in PBS, and (B) degradation rates of the scaffold compositions after 7, 14, 21, 28, and 40 days of immersion in PBS. Statistical analysis was considered at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 compared to the PVA/GEL control scaffold. Statistical analysis between KC and IC, as well as between LAP0.5 and LAP1 groups, indicated non-significant differences in swelling and degradation rate.

Figure 5.

(A) Swelling ratios of the scaffolds after 1 and 24 h of immersion in PBS, and (B) degradation rates of the scaffold compositions after 7, 14, 21, 28, and 40 days of immersion in PBS. Statistical analysis was considered at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 compared to the PVA/GEL control scaffold. Statistical analysis between KC and IC, as well as between LAP0.5 and LAP1 groups, indicated non-significant differences in swelling and degradation rate.

Figure 6.

Cumulative ion concentration released from acellular scaffolds at days 7, 14, and 21. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 4) (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 compared to the PVA/gelatin control at the corresponding timepoint; and §§§p < 0.001, §§§§p < 0.0001 are between LAP0.5 and LAP1; statistical analysis between KC and IC groups indicated non-significant differences).

Figure 6.

Cumulative ion concentration released from acellular scaffolds at days 7, 14, and 21. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 4) (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 compared to the PVA/gelatin control at the corresponding timepoint; and §§§p < 0.001, §§§§p < 0.0001 are between LAP0.5 and LAP1; statistical analysis between KC and IC groups indicated non-significant differences).

Figure 7.

Representative SEM images of cell adhesion on the various scaffold compositions at day 1 (magnification ×1000; scale bar 10 µm). (A) PVA/GEL, (B) PVA/GEL/KC, (C) PVA/GEL/IC, (D) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP0.5, (E) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP0.5, (F) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1, (G) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1.

Figure 7.

Representative SEM images of cell adhesion on the various scaffold compositions at day 1 (magnification ×1000; scale bar 10 µm). (A) PVA/GEL, (B) PVA/GEL/KC, (C) PVA/GEL/IC, (D) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP0.5, (E) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP0.5, (F) PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1, (G) PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1.

Figure 8.

(A) Cell viability and proliferation assessment expressed as absorbance and (B) as % viability at days 1, 3, and 7. Data are shown as mean ± SD of n = 5 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 compared to the PVA/gelatin control; #p < 0.05 shows differences between KC and IC; and §p < 0.05, §§p < 0.01, §§§p < 0.001 indicates differences between LAP0.5 and LAP1 at the corresponding timepoint).

Figure 8.

(A) Cell viability and proliferation assessment expressed as absorbance and (B) as % viability at days 1, 3, and 7. Data are shown as mean ± SD of n = 5 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 compared to the PVA/gelatin control; #p < 0.05 shows differences between KC and IC; and §p < 0.05, §§p < 0.01, §§§p < 0.001 indicates differences between LAP0.5 and LAP1 at the corresponding timepoint).

Figure 9.

Markers of osteogenic activity of pre-osteoblastic cells cultured on scaffolds. (A) ALP activity at days 3, 7, and 14; (B) calcium secretion and (C) total collagen secretion at days 7, 14, and 21. Data are presented as mean ± SD (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 compared to the PVA/gelatin control; ##p < 0.01 shows differences between KC and IC; and §§§§p < 0.0001 are between LAP0.5 and LAP1, at the corresponding timepoint).

Figure 9.

Markers of osteogenic activity of pre-osteoblastic cells cultured on scaffolds. (A) ALP activity at days 3, 7, and 14; (B) calcium secretion and (C) total collagen secretion at days 7, 14, and 21. Data are presented as mean ± SD (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 compared to the PVA/gelatin control; ##p < 0.01 shows differences between KC and IC; and §§§§p < 0.0001 are between LAP0.5 and LAP1, at the corresponding timepoint).

Table 1.

Acronyms and compositions of the developed scaffolds.

Table 1.

Acronyms and compositions of the developed scaffolds.

| Scaffold acronyms |

Composition |

| PVA/GEL |

3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde. |

| PVA/GEL/KC |

3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v kappa-carrageenan, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |

| PVA/GEL/IC |

3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v iota-carrageenan, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |

| PVA/GEL/KC/LAP0.5 |

3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v kappa-carrageenan, 0.5% w/v laponite, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |

| PVA/GEL/IC/LAP0.5 |

3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v iota-carrageenan, 0.5% w/v laponite, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |

| PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1 |

3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v kappa-carrageenan, 1% w/v laponite, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |

| PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1 |

3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v iota-carrageenan, 1% w/v laponite, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |