Submitted:

06 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Overview of the MAPK Pathway in Cancer

Canonical MAPK/ERK Cascade

Oncogenic Mutations in MAPK/ERK Cascade

| Cancer type | MAPK mutation |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma[19,21] | KRAS , BRAF |

| Colorectal carcinoma [22,23] | KRAS (G12D,G12C,G12S, G13D, Q61R, Q61H, Q61L) NRAS (G13A and Q61H), BRAF (V600) |

| Breast carcinoma [24,25] | KRAS , NRAS, MKP1,MKP2 |

| Lung carcinoma[26,27] | BRAF |

| Biliary carcinoma | MKP1, MKP2, JNK activity, MKK4 |

Dysregulation Beyond Mutations

JNK (c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase) Pathway — A Double-Edged Sword and Therapeutic Opportunities

Dual Roles: Apoptosis Promoter vs Tumor Facilitator

p38 MAPK Pathway in Oncogenesis

Dual Role of p38 Signaling Cascade in Oncogenesis

Oncological Targeting of MAPK Pathway

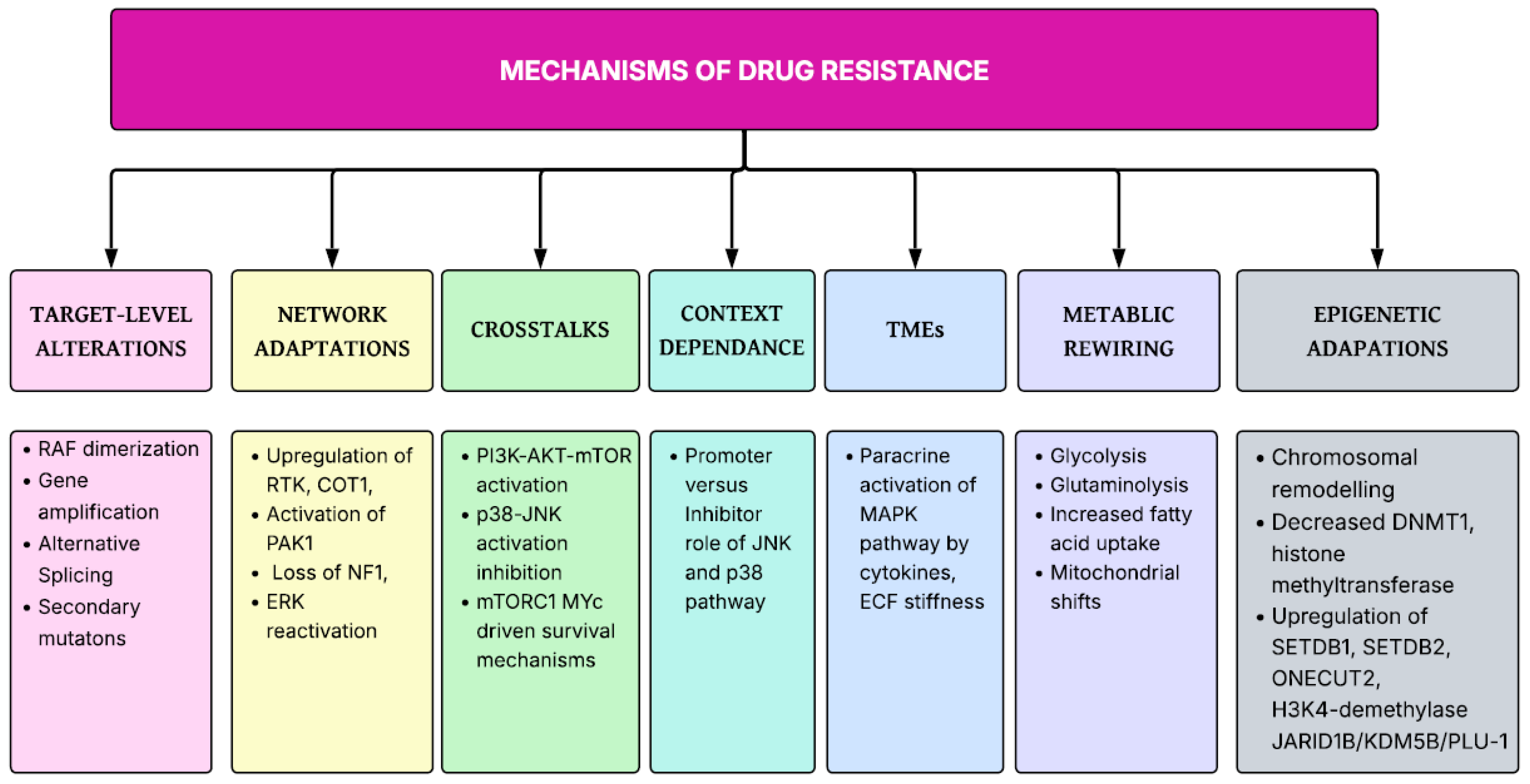

MAPK Targeting and Drug-Resistances

Targeting Drug Resistance in MAPK Tumor Therapy

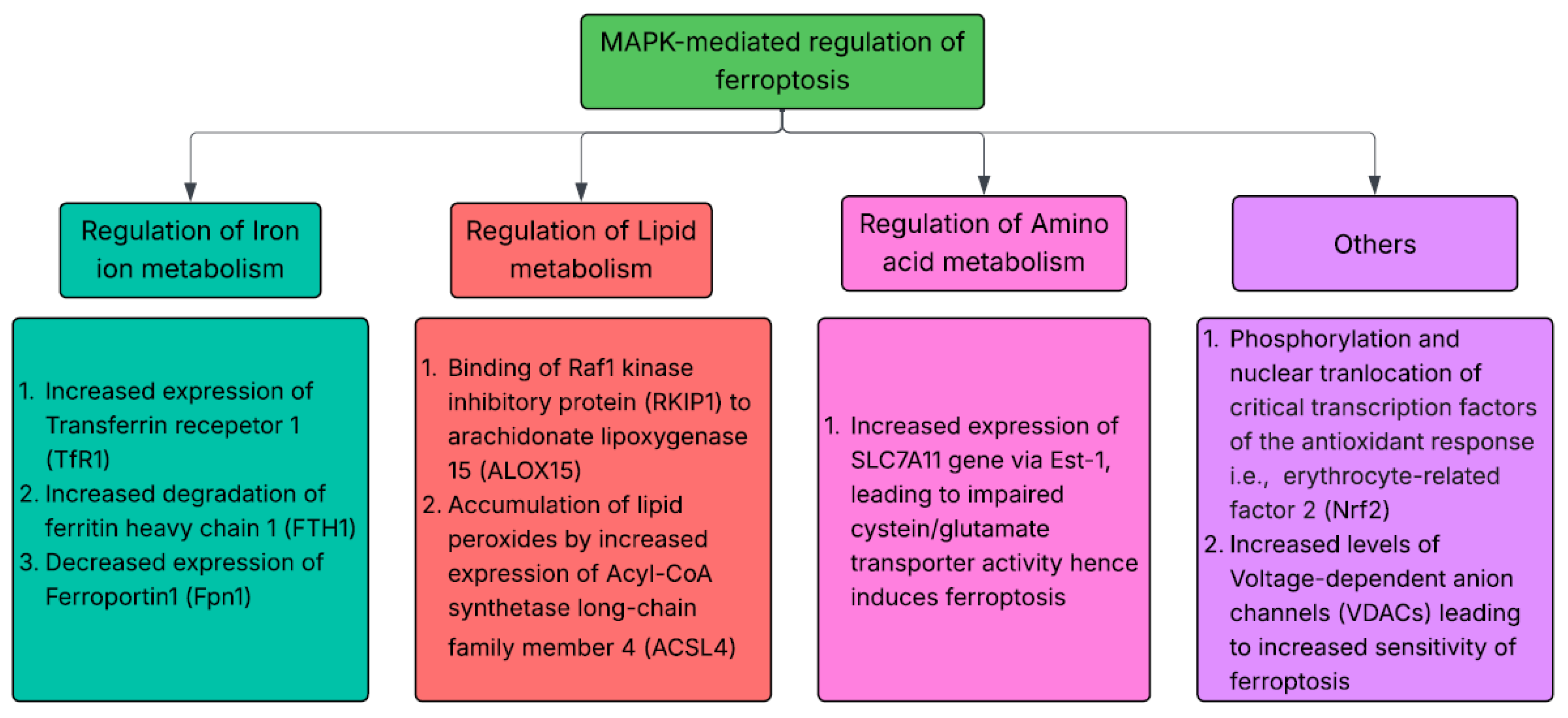

Role of MAPK Targeting with Ferroptosis Regulation in Oncology

MAPK Modulation of Ferroptosis- Therapeutic Role in Oncology

Conclusion

References

- Wu, Z.; Xia, F.; Lin, R. Global burden of cancer and associated risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1980–2021: a systematic analysis for the GBD 2021. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Gong, L.; Ye, J. The Role of Aberrant Metabolism in Cancer: Insights Into the Interplay Between Cell Metabolic Reprogramming, Metabolic Syndrome, and Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; López, J.M. Understanding MAPK Signaling Pathways in Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corre, I.; Paris, F.; Huot, J. The p38 pathway, a major pleiotropic cascade that transduces stress and metastatic signals in endothelial cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 55684–55714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.J.; Pan, W.W.; Liu, S.B.; Shen, Z.F.; Xu, Y.; Hu, L.L. ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, J.; Guo, Y. MAPK/ERK Signaling in Tumorigenesis: mechanisms of growth, invasion, and angiogenesis. EXCLI J. 2025, 24, 854–79. [Google Scholar]

- Burotto, M.; Chiou, V.L.; Lee, J.; Kohn, E.C. The MAPK pathway across different malignancies: A new perspective. Cancer 2014, 120, 3446–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maik-Rachline, G.; Hacohen-Lev-Ran, A.; Seger, R. Nuclear ERK: Mechanism of Translocation, Substrates, and Role in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkala, M.; Nkhoma, P.; Mulder, N.; Martin, D.P. Integrated molecular characterisation of the MAPK pathways in human cancers reveals pharmacologically vulnerable mutations and gene dependencies. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.R. Targeting the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway for cancer therapy: from mechanism to clinical studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, Q.; Cui, Y. Synergistic inhibition of MEK and reciprocal feedback networks for targeted intervention in malignancy. Cancer Biol. Med. 2019, 16, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshet, Y.; Seger, R. The MAP Kinase Signaling Cascades: A System of Hundreds of Components Regulates a Diverse Array of Physiological Functions. MAP Kinase Signal. Protoc. 2010, 661, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, G.Y.Q.; Loh, Z.W.-L.; Fann, D.Y.; Mallilankaraman, K.; Arumugam, T.V.; Hande, M.P. Role of Mitogen-Activated Protein (MAP) Kinase Pathways in Metabolic Diseases. Genome Integr. 2024, 15, 20230003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennig, A.; Markwart, R.; Esparza-Franco, M.A.; Ladds, G.; Rubio, I. Ras activation revisited: role of GEF and GAP systems. Biol. Chem. 2015, 396, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, A.; Nicke, B.; Warne, P.H.; Tomlinson, S.; Downward, J. The Transcriptional Response to Raf Activation Is Almost Completely Dependent on Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Kinase Activity and Shows a Major Autocrine Component. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 3450–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zi, X.; Koontz, Z.; Kim, A.; Xie, J.; Gorlick, R.; Holcombe, R.F.; Hoang, B.H. Blocking Wnt/LRP5 signaling by a soluble receptor modulates the epithelial to mesenchymal transition and suppresses met and metalloproteinases in osteosarcoma Saos-2 cells. J. Orthop. Res. 2007, 25, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Nicolet, J. Specificity models in MAPK cascade signaling. FEBS Open Bio 2023, 13, 1177–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Medarde, A.; Santos, E. Ras in Cancer and Developmental Diseases. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.D.; Fesik, S.W.; Kimmelman, A.C.; Luo, J.; Der, C.J. Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission Possible? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 828–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Guo, Z.; Wang, F.; Fu, L. KRAS mutation: from undruggable to druggable in cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiki, Y.; Jiang, C.; Ohmuraya, M.; Furukawa, T. Genetic Mutations of Pancreatic Cancer and Genetically Engineered Mouse Models. Cancers 2021, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Khatoon, A.; Bukhari, U.; Mirza, T. ANALYSIS OF COMMON SOMATIC MUTATIONS IN COLORECTAL CARCINOMA AND ASSOCIATED DYSREGULATED PATHWAYS. J. Ayub Med Coll. Abbottabad 2023, 35, 137–143–137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmokhtar, S.; Laraqui, A.; El Boukhrissi, F.; Hilali, F.; Bajjou, T.; Jafari, M.; El Zaitouni, S.; Baba, W.; El Mchichi, B.; Elannaz, H.; et al. Clinical Significance of Somatic Mutations in RAS/RAF/MAPK Signaling Pathway in Moroccan and North African Colorectal Cancer Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 3725–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Gonzalez, C.; Ferrell, M.; Giza, R.; Syed, M.P.; Magge, T.; Bao, R.; Singhi, A.D.; Saeed, A.; Sahin, I.H. Identification of MAPK and mTOR pathway alterations in HER2-amplified colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 185–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Cheng, Z.; Malbon, C.C. Overexpression of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases MKP1, MKP2 in human breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2003, 191, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Huang, Z.; Guo, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, S.; Bai, N.; Chen, H.; Xue, J.; Wang, D.; et al. Super multiple primary lung cancers harbor high-frequency BRAF and low-frequency EGFR mutations in the MAPK pathway. npj Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- bo, Shen H; Li, J; shan, Yao Y; hua, Yang Z; jie, Zhou Y; Chen, W; et al. Impact of Somatic Mutations in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Study of a Chinese Cohort. Cancer Manag Res. 2020, 12, 7427–37. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, R.K.; Bogoyevitch, M.A. The c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase family of mitogen-activated protein kinases (JNK MAPKs). Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2001, 33, 1047–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; He, L.; Lv, D.; Yang, J.; Yuan, Z. The Role of the Dysregulated JNK Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Human Diseases and Its Potential Therapeutic Strategies: A Comprehensive Review. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in... - Google Scholar [Internet]. 11 Oct 2025. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Signal+integration+by+JNK+and+p38+MAPK+pathways+in+cancer+development+-+PubMed+%5BInternet%5D.+%5Bcited+2025+Sept+21%5D.+Available+from%3A+https%3A%2F%2Fpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov%2F19629069%2F&btnG=.

- Tian, X.; Traub, B.; Shi, J.; Huber, N.; Schreiner, S.; Chen, G.; Zhou, S.; Henne-Bruns, D.; Knippschild, U.; Kornmann, M. c-Jun N-terminal kinase 2 suppresses pancreatic cancer growth and invasion and is opposed by c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021, 29, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C; Zhang, H; Yang, C; Yin, M; Teng, X; Yang, M; et al. Inhibition of JNK Signaling Overcomes Cancer-Associated Fibroblast-Mediated Immunosuppression and Enhances the Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Bladder Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024, 84(24), 4199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Jin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Wan, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, L.; et al. LINC02257 regulates colorectal cancer liver metastases through JNK pathway. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, B.; Cheng, S.; Fan, H.; Liu, S.; Zhou, B.; Liu, W.; Liang, R.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y. KDELR2 knockdown synergizes with temozolomide to induce glioma cell apoptosis through the CHOP and JNK/p38 pathways. Transl. Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 3491–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zuo, K.; Li, K.; Gao, Y.; Chen, M.; Hu, R.; Liu, Y.; Chi, H.; Wang, H.; Qin, Y.; et al. p38/JNK Is Required for the Proliferation and Phenotype Changes of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Induced by L3MBTL4 in Essential Hypertension. Int. J. Hypertens. 2020, 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.Y.; Clark, J.J.; Fernando, A.; Domann, F.; Hansen, M.R. Contribution of persistent C-Jun N-terminal kinase activity to the survival of human vestibular schwannoma cells by suppression of accumulation of mitochondrial superoxides. Neuro-Oncology 2011, 13, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granato, M.; Santarelli, R.; Lotti, L.V.; Di Renzo, L.; Gonnella, R.; Garufi, A.; Trivedi, P.; Frati, L.; D'Orazi, G.; Faggioni, A.; et al. JNK and Macroautophagy Activation by Bortezomib Has a Pro-Survival Effect in Primary Effusion Lymphoma Cells. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e75965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Limón, A.; Joaquin, M.; Caballero, M.; Posas, F.; de Nadal, E. The p38 Pathway: From Biology to Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- p38 MAP-kinases pathway regulation, function and role in human diseases - PubMed [Internet]. 9 Oct 2025. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17481747/.

- A, C; Jj, SE. p38γ and p38δ: From Spectators to Key Physiological Players. Trends Biochem Sci [Internet]. 2017 June [cited 2025 Oct 9], 42. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28473179/.

- Yn D, A C, Gm T, P C, Ar N. Activation of the MAP kinase homologue RK requires the phosphorylation of Thr-180 and Tyr-182 and both residues are phosphorylated in chemically stressed KB cells. FEBS Lett [Internet]. 8 May 1995, 364. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7750576/.

- Dérijard, B.; Raingeaud, J.; Barrett, T.; Wu, I.-H.; Han, J.; Ulevitch, R.J.; Davis, R.J. Independent Human MAP-Kinase Signal Transduction Pathways Defined by MEK and MKK Isoforms. Science 1995, 267, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enslen, H.; Raingeaud, J.; Davis, R.J. Selective Activation of p38 Mitogen-activated Protein (MAP) Kinase Isoforms by the MAP Kinase Kinases MKK3 and MKK6. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 1741–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, G.; Ambrosino, C.; Jones, M.; Nebreda, A.R. Differential Activation of p38 Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Isoforms Depending on Signal Strength. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 40641–40648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remy, G.; Risco, A.M.; Iñesta-Vaquera, F.A.; González-Terán, B.; Sabio, G.; Davis, R.J.; Cuenda, A. Differential activation of p38MAPK isoforms by MKK6 and MKK3. Cell. Signal. 2010, 22, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonney, E.A. Mapping out p38MAPK. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2017, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K; Sudo, T; Senftleben, U; Dadak, AM; Johnson, R; Karin, M. Requirement for p38alpha in erythropoietin expression: a role for stress kinases in erythropoiesis. Cell 2000, 102(2), 221–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, J.J.; Tenbaum, S.; Perdiguero, E.; Huth, M.; Guerra, C.; Barbacid, M.; Pasparakis, M.; Nebreda, A.R. p38α MAP kinase is essential in lung stem and progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurai, T.; He, G.; Matsuzawa, A.; Yu, G.-Y.; Maeda, S.; Hardiman, G.; Karin, M. Hepatocyte Necrosis Induced by Oxidative Stress and IL-1α Release Mediate Carcinogen-Induced Compensatory Proliferation and Liver Tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2008, 14, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubern, A.; Joaquin, M.; Marquès, M.; Maseres, P.; Garcia-Garcia, J.; Amat, R.; González-Nuñez, D.; Oliva, B.; Real, F.X.; de Nadal, E.; et al. The N-Terminal Phosphorylation of RB by p38 Bypasses Its Inactivation by CDKs and Prevents Proliferation in Cancer Cells. Mol. Cell 2016, 64, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, M.; Canals, D.; Adada, M.; Coant, N.; Salama, M.F.; Helke, K.L.; Arthur, J.S.; Shroyer, K.R.; Kitatani, K.; Obeid, L.M.; et al. P38 delta MAPK promotes breast cancer progression and lung metastasis by enhancing cell proliferation and cell detachment. Oncogene 2017, 36, 6649–6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targeting p38α Increases DNA Damage, Chromosome Instability, and the Anti-tumoral Response to Taxanes in Breast Cancer Cells - PubMed [Internet]. 9 Oct 2025. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29805078/.

- Greenberg, A.K.; Basu, S.; Hu, J.; Yie, T.-A.; Tchou-Wong, K.M.; Rom, W.N.; Lee, T.C. Selective p38 Activation in Human Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2002, 26, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A role for p38 MAPK in head and neck cancer cell growth and tumor-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis - PubMed [Internet]. 9 Oct 2025. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24216180/.

- P38 kinase in gastrointestinal cancers - PMC [Internet]. 9 Oct 2025. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10501902/.

- Gupta, J.; Del Barco Barrantes, I.; Igea, A.; Sakellariou, S.; Pateras, I.S.; Gorgoulis, V.G.; Nebreda, A.R. Dual Function of p38α MAPK in Colon Cancer: Suppression of Colitis-Associated Tumor Initiation but Requirement for Cancer Cell Survival. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Loba, A.; Manieri, E.; González-Terán, B.; Mora, A.; Leiva-Vega, L.; Santamans, A.M.; Romero-Becerra, R.; Rodríguez, E.; Pintor-Chocano, A.; Feixas, F.; et al. p38γ is essential for cell cycle progression and liver tumorigenesis. Nature 2019, 568, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B; Koul, S; Petersen, J; Khandrika, L; Hwa, JS; Meacham, RB; et al. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-driven MAPKAPK2 regulates invasion of bladder cancer by modulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity. Cancer Res. 2010, 70(2), 832–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, T.; Ninomiya, T.; Kohno, T.; Kikuchi, S.; Sawada, N.; Kojima, T. c-Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitor SP600125 enhances barrier function and elongation of human pancreatic cancer cell line HPAC in a Ca-switch model. Histochem. 2014, 143, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemaà, M.; Boubaker, N.S.; Kerkeni, N.; Huber, S.M. JNK Inhibition Overcomes Resistance of Metastatic Tetraploid Cancer Cells to Irradiation-Induced Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Kuramoto, K.; Takeda, H.; Watarai, H.; Sakaki, H.; Seino, S.; Seino, M.; Suzuki, S.; Kitanaka, C. The novel JNK inhibitor AS602801 inhibits cancer stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 27021–27032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, K.-I.; Sato, A.; Okada, M.; Shibuya, K.; Seino, S.; Suzuki, K.; Watanabe, E.; Narita, Y.; Shibui, S.; Kayama, T.; et al. Targeting JNK for therapeutic depletion of stem-like glioblastoma cells. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seino, M; Okada, M; Shibuya, K; Seino, S; Suzuki, S; Ohta, T; et al. Requirement of JNK signaling for self-renewal and tumor-initiating capacity of ovarian cancer stem cells. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34(9), 4723–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bentamapimod (JNK Inhibitor AS602801) Induces Regression of Endometriotic Lesions in Animal Models | Request PDF. ResearchGate [Internet]. 9 Aug 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281515285_Bentamapimod_JNK_Inhibitor_AS602801_Induces_Regression_of_Endometriotic_Lesions_in_Animal_Models.

- Yao, K; Chen, H; Lee, MH; Li, H; Ma, W; Peng, C; et al. Licochalcone A, a natural inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1. Cancer Prev Res Phila Pa 2014, 7(1), 139–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yang, X.; Kang, Q.; Lu, J.; Denzinger, M.; Kornmann, M.; Traub, B. JNK inhibitor IX restrains pancreatic cancer through p53 and p21. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1006131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JNK pathway inhibition selectively primes pancreatic cancer stem cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis without affecting the physiology of normal tissue resident stem cells - PubMed [Internet]. 9 Oct 2025. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26840266/.

- Luke, JJ; Hodi, FS. Ipilimumab, Vemurafenib, Dabrafenib, and Trametinib: Synergistic Competitors in the Clinical Management of BRAF Mutant Malignant Melanoma. The Oncologist 2013, 18(6), 717–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Shuo, L.; Yingru, X.; Min, M.; Runpeng, Z.; Jun, X.; Dong, H. Artesunate promotes sensitivity to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 519, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, RJ; Infante, JR; Janku, F; Wong, DJL; Sosman, JA; Keedy, V; et al. First-in-Class ERK1/2 Inhibitor Ulixertinib (BVD-523) in Patients with MAPK Mutant Advanced Solid Tumors: Results of a Phase I Dose-Escalation and Expansion Study. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8(2), 184–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigaud, R.; Rösch, L.; Gatzweiler, C.; Benzel, J.; von Soosten, L.; Peterziel, H.; Selt, F.; Najafi, S.; Ayhan, S.; Gerloff, X.F.; et al. The first-in-class ERK inhibitor ulixertinib shows promising activity in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-driven pediatric low-grade glioma models. Neuro-Oncology 2022, 25, 566–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhanji, V.; Duncan, J.; Gardner, T.; Hughes, G.K.; McIntire, R.; Peña, A.M.; Ladd, C.; Gardner, B.; Moore, T.; Garrett, E.; et al. Assessing Patient Risk, Benefit, and Outcomes in Drug Development: A Decade of Dabrafenib and Trametinib Clinical Trials. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2025, 24, 1701–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Langen, A.J.; Johnson, M.L.; Mazieres, J.; Dingemans, A.-M.C.; Mountzios, G.; Pless, M.; Wolf, J.; Schuler, M.; Lena, H.; Skoulidis, F.; et al. Sotorasib versus docetaxel for previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer with KRASG12C mutation: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jänne, PA; Riely, GJ; Gadgeel, SM; Heist, RS; Ou, SHI; Pacheco, JM; et al. Adagrasib in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring a KRASG12C Mutation. N Engl J Med 2022, 387(2), 120–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, V.E.; Passos, J.; Nzwalo, H.; Carvalho, I.; Santos, F.; Martins, C.; Salgado, L.; e Silva, C.; Vinhais, S.; Vilares, M.; et al. Selumetinib for plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis type 1: a single-institution experience. J. Neuro-Oncology 2020, 147, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zou, Z.; Zhang, W.; Fang, M.; Zhang, X.; Luo, Z.; Chen, J.; Huang, G.; Zhang, P.; Cheng, Y.; et al. A phase II study of efficacy and safety of the MEK inhibitor tunlametinib in patients with advanced NRAS-mutant melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 202, 114008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, Z.; Algazi, A.P.; Lomeli, S.H.; Wang, Y.; Othus, M.; Hong, A.; Wang, X.; Randolph, C.E.; et al. Anti-PD-1/L1 lead-in before MAPK inhibitor combination maximizes antitumor immunity and efficacy. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 1375–1387.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, O.E.; Orton, R.; Grindlay, J.; Birtwistle, M.; Vyshemirsky, V.; Gilbert, D.; Calder, M.; Pitt, A.; Kholodenko, B.; Kolch, W. The Mammalian MAPK/ERK Pathway Exhibits Properties of a Negative Feedback Amplifier. Sci. Signal. 2010, 3, ra90–ra90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghfuri, E.; Nikfar, S.; Niaz, K.; Faramarzi, M.A.; Abdollahi, M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitors to treat melanoma alone or in combination with other kinase inhibitors. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, M.; Jawed, A.; Mandal, R.K.; Dar, S.A.; Akhter, N.; Somvanshi, P.; Khan, F.; Lohani, M.; Areeshi, M.Y.; Haque, S. Recent developments and obstacles in the treatment of melanoma with BRAF and MEK inhibitors. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2018, 125, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Rauch, J.; Kolch, W. Targeting MAPK Signaling in Cancer: Mechanisms of Drug Resistance and Sensitivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H; Liu, S; Zhang, G; Wu, Bin; Zhu, Y; Frederick, DT; et al. PAK signalling drives acquired drug resistance to MAPK inhibitors in BRAF-mutant melanomas. Nature 2017, 550(7674), 133–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y; Naito, Y; Cope, L; Naranjo-Suarez, S; Saunders, T; Hong, SM; et al. Functional p38 MAPK identified by biomarker profiling of pancreatic cancer restrains growth through JNK inhibition and correlates with improved survival. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 2014, 20(23), 6200–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Yang, D.; Xie, C.; Qin, S.; Jiang, H. Bidirectional effects of morphine on pancreatic cancer progression via the p38/JNK pathway. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarweh, S; Osborne, CK; Creighton, CJ; Qin, L; Tsimelzon, A; Huang, S; et al. Tamoxifen resistance in breast tumors is driven by growth factor receptor signaling with repression of classic estrogen receptor genomic function. Cancer Res. 2008, 68(3), 826–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Bugide, S.; Wang, B.; Green, M.R.; Johnson, D.B.; Wajapeyee, N. Loss of BOP1 confers resistance to BRAF kinase inhibitors in melanoma by activating MAP kinase pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 4583–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H; Li, C; Dang, Q; Chang, LS; Li, L. Infiltrating mast cells increase prostate cancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy resistances via modulation of p38/p53/p21 and ATM signals. Oncotarget 2016, 7(2), 1341–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, M.; Huang, M.; Lin, Q.; Fang, Q.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Zhan, X.; Shan, H.; et al. The multi-molecular mechanisms of tumor-targeted drug resistance in precision medicine. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 113064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, J.L.; Layos, L.; Bugés, C.; de Los Llanos Gil, M.; Vila, L.; Martínez-Balibrea, E.; Martinez-Cardus, A. Resistant mechanisms to BRAF inhibitors in melanoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rini: Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib... - Google Scholar [Internet]. Available from. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Pembrolizumab%20plus%20axitinib%20versus%20sunitinib%20for%20advanced%20renal-cell%20carcinoma&publication_year=2019&author=B.I.%20Rini&author=E.R.%20Plimack&author=V.%20Stus&author=R.%20Gafanov&author=R.%20Hawkins&author=D.%20Nosov&author=F.%20Pouliot&author=B.%20Alekseev&author=D.%20Soulieres&author=B.%20Melichar&author=I.%20Vynnychenko&author=A.%20Kryzhanivska&author=I.%20Bondarenko&author=S.J.%20Azevedo&author=D.%20Borchiellini&author=C.%20Szczylik&author=M.%20Markus&author=R.S.%20McDermott&author=J.%20Bedke&author=S.%20Tartas&author=Y.H.%20Chang&author=S.%20Tamada&author=Q.%20Shou&author=R.F.%20Perini&author=M.%20Chen&author=M.B.%20Atkins&author=T.%20Powles&author=K.-.%20Investigators, 24 Nov 2025.

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulières, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramucirumab plus erlotinib in patients with untreated, EGFR-mutated, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (RELAY): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial - The Lancet Oncology [Internet]. 24 Nov 2025. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(19)30634-5/abstract.

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella: Patient-reported outcomes with first-line... - Google Scholar [Internet]. 24 Nov 2025. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Patient-reported%20outcomes%20with%20first-line%20nivolumab%20plus%20cabozantinib%20versus%20sunitinib%20in%20patients%20with%20advanced%20renal%20cell%20carcinoma%20treated%20in%20CheckMate%209ER%3A%20an%20open-label%2C%20randomised%2C%20phase%203%20trial&publication_year=2022&author=D.%20Cella&author=R.J.%20Motzer&author=C.%20Suarez&author=S.I.%20Blum&author=F.%20Ejzykowicz&author=M.%20Hamilton&author=J.F.%20Wallace&author=B.%20Simsek&author=J.%20Zhang&author=C.%20Ivanescu&author=A.B.%20Apolo&author=T.K.%20Choueiri.

- Kelley. VP10-2021: cabozantinib (C) plus atezolizumab... - Google Scholar [Internet]. Available from. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=VP10-2021%3A%20Cabozantinib%20%20plus%20atezolizumab%20%20versus%20sorafenib%20%20as%20first-line%20systemic%20treatment%20for%20advanced%20hepatocellular%20carcinoma%20%3A%20Results%20from%20the%20randomized%20phase%20III%20COSMIC-312%20trial&publication_year=2022&author=R.K.%20Kelley&author=T.%20Yau&author=A.L.%20Cheng&author=A.%20Kaseb&author=S.%20Qin&author=A.X.%20Zhu&author=S.%20Chan&author=W.%20Sukeepaisarnjaroen&author=V.%20Breder&author=G.%20Verset&author=E.%20Gane&author=I.%20Borbath&author=J.D.%20Gomez%20Rangel&author=P.%20Merle&author=F.M.%20Benzaghou&author=K.%20Banerjee&author=S.%20Hazra&author=J.%20Fawcett&author=L.%20Rimassa, 24 Nov 2025.

- Smith, MP; Brunton, H; Rowling, EJ; Ferguson, J; Arozarena, I; Miskolczi, Z; et al. Inhibiting Drivers of Non-mutational Drug Tolerance Is a Salvage Strategy for Targeted Melanoma Therapy. Cancer Cell 2016, 29(3), 270–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bim, Puma. Noxa upregulation by Naftopidil sensitizes ovarian cancer to the BH3-mimetic ABT-737 and the MEK inhibitor Trametinib - PubMed [Internet]. 24 Nov 2025. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32424251/.

- Stratford, A.L.; Fry, C.J.; Desilets, C.; Davies, A.H.; Cho, Y.Y.; Li, Y.; Dong, Z.; Berquin, I.M.; Roux, P.P.; E Dunn, S. Y-box binding protein-1 serine 102 is a downstream target of p90 ribosomal S6 kinase in basal-like breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2008, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosnopfel, C.; Sinnberg, T.; Sauer, B.; Niessner, H.; Schmitt, A.; Makino, E.; Forschner, A.; Hailfinger, S.; Garbe, C.; Schittek, B. Human melanoma cells resistant to MAPK inhibitors can be effectively targeted by inhibition of the p90 ribosomal S6 kinase. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 35761–35775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthan, A.; Yue, L.; Huynh, M.-M.; Los, G.; Dunn, S.E. Abstract 5378: PMD-026, a first in class oral RSK inhibitor, demonstrates activity against hormone receptor positive breast cancer with acquired CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance. Cancer Res. 2022, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeram, M.; Chalasani, P.; Wang, J.S.; Mina, L.A.; Shatsky, R.A.; Trivedi, M.S.; Wesolowski, R.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Han, H.S.; Patnaik, A.; et al. First-in-human phase 1/1b expansion of PMD-026, an oral RSK inhibitor, in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, e13043–e13043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushijima, M; Shiota, M; Matsumoto, T; Kashiwagi, E; Inokuchi, J; Eto, M. An oral first-in-class small molecule RSK inhibitor suppresses AR variants and tumor growth in prostate cancer. Cancer Sci 2022, 113(5), 1731–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosnopfel, C.; Wendlinger, S.; Niessner, H.; Siewert, J.; Sinnberg, T.; Hofmann, A.; Wohlfarth, J.; Schrama, D.; Berthold, M.; Siedel, C.; et al. Inhibition of p90 ribosomal S6 kinases disrupts melanoma cell growth and immune evasion. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiblecker, L.; Kollmann, K.; Sexl, V. CDK4/6 and MAPK—Crosstalk as Opportunity for Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-H.; Gong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Van Horn, R.D.; Yin, T.; Huber, L.; Burke, T.F.; Manro, J.; Iversen, P.W.; Wu, W.; et al. RAF inhibitor LY3009120 sensitizes RAS or BRAF mutant cancer to CDK4/6 inhibition by abemaciclib via superior inhibition of phospho-RB and suppression of cyclin D1. Oncogene 2017, 37, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, V; Burke, TF; Huber, L; Van Horn, RD; Zhang, Y; Buchanan, SG; et al. The CDK4/6 inhibitor LY2835219 overcomes vemurafenib resistance resulting from MAPK reactivation and cyclin D1 upregulation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014, 13(10), 2253–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, LN; Costello, JC; Liu, H; Jiang, S; Helms, TL; Langsdorf, AE; et al. Oncogenic NRAS signaling differentially regulates survival and proliferation in melanoma. Nat Med. 2012, 18(10), 1503–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, LS; Rader, J; Raman, P; Batra, V; Russell, MR; Tsang, M; et al. Preclinical therapeutic synergy of MEK1/2 and CDK4/6 inhibition in neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017, 23(7), 1785–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.-R.; Chen, L.; Wei, Y.; Yu, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Jiao, B.; Shi, T.; Sun, L.; Zhang, C.; et al. Discovery of Selective Small Molecule Degraders of BRAF-V600E. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 4069–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, S.; Jaime-Figueroa, S.; Yao, Z.; Gao, Y.; Hines, J.; Samarasinghe, K.T.G.; Vogt, L.; Rosen, N.; Crews, C.M. Mutant-selective degradation by BRAF-targeting PROTACs. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posternak, G.; Tang, X.; Maisonneuve, P.; Jin, T.; Lavoie, H.; Daou, S.; Orlicky, S.; de Rugy, T.G.; Caldwell, L.; Chan, K.; et al. Functional characterization of a PROTAC directed against BRAF mutant V600E. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, H.; Tian, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Ma, S.; Wang, X.; Qin, C. ZJK-807: A Selective PROTAC Degrader of KRASG12D Overcoming Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 20103–20129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Kim, S.; Chung, H.-T.; Pae.

- Ye, F; Chai, W; Xie, M; Yang, M; Yu, Y; Cao, L; et al. HMGB1 regulates erastin-induced ferroptosis via RAS-JNK/p38 signaling in HL-60/NRASQ61L cells. Am J Cancer Res. 2019, 9(4), 730–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Tan, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Shi, H. The emerging roles of MAPK-AMPK in ferroptosis regulatory network. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.-C.; Shieh, J.-M.; Wu, W.-B. P38 MAPK and Nrf2 Activation Mediated Naked Gold Nanoparticle Induced Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression in Rat Aortic Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arch. Med Res. 2020, 51, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagoda, N.; Von Rechenberg, M.; Zaganjor, E.; Bauer, A.J.; Yang, W.S.; Fridman, D.J.; Wolpaw, A.J.; Smukste, I.; Peltier, J.M.; Boniface, J.J.; et al. RAS–RAF–MEK-dependent oxidative cell death involving voltage-dependent anion channels. Nature 2007, 447, 865–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, T.; Saleem, M.A.; Khan, M.U.M.; Rashid, M.A.R.; Zubair, M. Ferroptosis as a Therapeutic Avenue in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Mechanistic Insights and Prognostic Potential. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolma, S.; Lessnick, S.L.; Hahn, W.C.; Stockwell, B.R. Identification of genotype-selective antitumor agents using synthetic lethal chemical screening in engineered human tumor cells. Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.S.; Stockwell, B.R. Synthetic Lethal Screening Identifies Compounds Activating Iron-Dependent, Nonapoptotic Cell Death in Oncogenic-RAS-Harboring Cancer Cells. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poursaitidis, I.; Wang, X.; Crighton, T.; Labuschagne, C.; Mason, D.; Cramer, S.L.; Triplett, K.; Roy, R.; Pardo, O.E.; Seckl, M.J.; et al. Oncogene-Selective Sensitivity to Synchronous Cell Death following Modulation of the Amino Acid Nutrient Cystine. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 2547–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolacci, C.; Andreani, C.; Vale, G.; Berto, S.; Melegari, M.; Crouch, A.C.; Baluya, D.L.; Kemble, G.; Hodges, K.; Starrett, J.; et al. Targeting de novo lipogenesis and the Lands cycle induces ferroptosis in KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Sun, B.; Zhong, C.; Xu, K.; Wang, Z.; Hofman, P.; Nagano, T.; Legras, A.; Breadner, D.; Ricciuti, B.; et al. Targeting histone deacetylase enhances the therapeutic effect of Erastin-induced ferroptosis in EGFR-activating mutant lung adenocarcinoma. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louandre, C.; Ezzoukhry, Z.; Godin, C.; Barbare, J.; Mazière, J.; Chauffert, B.; Galmiche, A. Iron-dependent cell death of hepatocellular carcinoma cells exposed to sorafenib. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 133, 1732–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, ER; Truesdale, AT; McDonald, OB; Yuan, D; Hassell, A; Dickerson, SH; et al. A unique structure for epidermal growth factor receptor bound to GW572016 (Lapatinib): relationships among protein conformation, inhibitor off-rate, and receptor activity in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2004, 64(18), 6652–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Henson, E.S.; Chen, Y.; Gibson, S.B. Ferroptosis is induced following siramesine and lapatinib treatment of breast cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2307–e2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrends: Network organization of the human autophagy system - Google Scholar [Internet]. 1 Dec 2025. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Network%20organization%20of%20the%20human%20autophagy%20system&publication_year=2010&author=B.%20Christian.

- Chano, T.; Ikebuchi, K.; Ochi, Y.; Tameno, H.; Tomita, Y.; Jin, Y.; Inaji, H.; Ishitobi, M.; Teramoto, K.; Nishimura, I.; et al. RB1CC1 Activates RB1 Pathway and Inhibits Proliferation and Cologenic Survival in Human Cancer. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e11404–e11404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue: Tumour cells are sensitised to ferroptosis via... - Google Scholar [Internet]. 1 Dec 2025. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Tumour%20cells%20are%20sensitised%20to%20ferroptosis%20via%20RB1CC1-mediated%20transcriptional%20reprogramming&publication_year=2022&author=X.%20Xiangfei.

- Dai, Z.; Liu, J.; Zeng, L.; Shi, K.; Peng, X.; Jin, Z.; Zheng, R.; Zeng, C. Targeting ferroptosis in cancer therapy: Mechanisms, strategies, and clinical applications. Cell Investig. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, T.; Zhu, J.; Wang, H.; Li, T.; Jin, A.; Ding, L.; Xian, J.; et al. Modulation of the p38 MAPK Pathway by Anisomycin Promotes Ferroptosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma through Phosphorylation of H3S10. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 6986445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, X.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Duan, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yang, H.; Yuan, W.; et al. Reactivation of MAPK-SOX2 pathway confers ferroptosis sensitivity in KRASG12C inhibitor resistant tumors. Redox Biol. 2024, 78, 103419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cancer type | Mechanism and Therapeutic implications | Dual role | Ref |

| Pancreatic cancer | ● JNK2 inhibition increases invasion ● JNK1 inhibition leads to tumor growth suppression Need for Isoform selective therapeutic targeting strategies |

Pro-apoptotic and Pro-tumorigenic | [31] |

| Bladder cancer | ● JNK inhibition decreases cancer-associated fibroblasts mediated expression of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) required for creating immunosuppressive microenvironment JNK inhibition with Anti- PD-1 treatment is effective against bladder cancer |

Pro-tumorigenic | [32] |

| Colorectal carcinoma | ● LINC02257/JNK axis leads to colorectal liver metastasis | Pro-tumorigenic | [33] |

| Glioma | ● Pro-apoptotic in glioma cells, pro-proliferative in vascular smooth muscle cells | Pro-apoptotic and Pro-tumorigenic | [34,35] |

| Vestibular Schwannoma | ● Inhibits apoptosis of cancer cells by limiting ROS accumulation | Pro-tumorigenic | [36] |

| Lymphoma | ● Inhibits apoptosis of cancer cells by limiting ROS accumulation Combination therapy of bortezomib with JNK inhibitors required |

Pro-tumorigenic | [37] |

| Type of cancer | p38 isoform | Evidence | Reference |

| Breast cancer | p38α | Deletion leads to altered DNA damage response after | [52] |

| p38δ | Deletion leads to decreased tumor volume | [51] | |

| Lung cancers | - | Increased p38 kinase activation | [53] |

| Head and Neck cancers | - | Hyperactivated p38 in tissue samples | [54] |

| Colon cancers | p38γ | Increased expression leading to increased proliferation | [55] |

| p38α | Increased expression leading to increased proliferation | [56] | |

| Liver cancers | p38γ | deletion or inhibition reduces formation of liver tumors induced by chemicals | [57] |

| Bladder carcinoma | p38α | Inhibition leads to reduced invasion of cancer cells by diminishing MMP-2/9 activities | [58] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).